Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) exert negative effects on gene expression and influence cell lineage choice during hematopoiesis. C/EBPa-induced pre-B cell-to-macrophage transdifferentiation provides an excellent model to investigate the contribution of miRNAs to hematopoietic cell identity, especially because the two cell types involved fall into separate lymphoid and myeloid branches. In this process, efficient repression of the B cell-specific program is essential to ensure transdifferentation and macrophage function. miRNA profiling revealed that upregulation of miRNAs is highly predominant compared with downregulation and that C/EBPa directly regulates several upregulated miRNAs. We also determined that miRNA 34a (miR-34a) and miR-223 sharply accelerate C/EBPa-mediated transdifferentiation, whereas their depletion delays this process. These two miRNAs affect the transdifferentiation efficiency and activity of macrophages, including their lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-dependent inflammatory response. miR-34a and miR-223 directly target and downregulate the lymphoid transcription factor Lef1, whose ectopic expression delays transdifferentiation to an extent similar to that seen with miR-34a and miR-223 depletion. In addition, ectopic introduction of Lef1 in macrophages causes upregulation of B cell markers, including CD19, Pax5, and Ikzf3. Our report demonstrates the importance of these miRNAs in ensuring the erasure of key B cell transcription factors, such as Lef1, and reinforces the notion of their essential role in fine-tuning the control required for establishing cell identity.

INTRODUCTION

The successful generation of differentiated cell types from their progenitors depends on the highly coordinated regulation of gene expression by transcription factors (TFs), epigenetic modifications, and small noncoding RNAs. Among small noncoding RNAs, microRNAs (miRNAs) are the best studied. These regulate gene expression through sequence complementarity with their target mRNAs by mediating their decay or interfering with their translation (1). TFs regulate miRNA expression and are themselves regulated by miRNAs, thereby establishing complex loops of regulation. However, the interplay between TFs and miRNAs is not completely understood and their net contribution is likely to be specific to each different terminal differentiation process and is yet to be determined.

TF-mediated cell transdifferentiation strategies are excellent models for investigating the individual contributions of TFs, as well as the interplay of diferent regulators. In transdifferentiation models, forced expression of a transcription factor induces conversion of one specific cell type into another (2, 3).

We have recently used a model for transcription factor-induced lineage reprogramming based on the ectopic expression of C/EBPα in pre-B cells that results in their conversion into functional macrophages (4). B cells and macrophages represent archetypical cell types of the adaptive and innate immunity, respectively. The progenitors of these two cell types diverge very early during hematopoietic differentiation, resulting in highly differentiated cell types with specific expression and epigenomic profiles (5). This transdifferentiation model provides not only a system with relevance in the regenerative medicine field but also a smart and elegant strategy to dissect the mechanisms underneath what makes a macrophage a macrophage. Transdifferentiation can be achieved by inducing expression of C/EBPα by retroviral infection of primary pre-B cells (4) or by using a leukemic pre-B cell line, HAFTL, which is stably infected with an inducible form of C/EBPα (6). As a TF important for the formation of granulocytes and macrophages (7, 8), C/EBPα may be confidently expected to induce the expression of myeloid cell-specific genes. However, it is less obvious that C/EBPα also silences the B cell-specific gene program and how it does so remains unclear. The dynamics of changes over time shows a rapid reduction of B cell-specific marker levels, without expression of stem cell or common lymphoid precursor markers, thus ruling out the occurrence of overt retrodifferentiation (9). Downregulation includes not only factors such as Pax5, Ikzf1, and Ebf1 but also Lef1, whose roles in B cell differentiation and function are more controversial (10–13). Changes in mRNA levels of B cell-specific genes reflect the participation of different mechanisms: direct effects of C/EBPα-mediated control of their transcription, indirect effects through the direct action of TFs that are C/EBPα-direct targets, and direct or indirect effects through epigenetic changes. Dissection of the epigenetic mechanisms in this process has discarded the participation of significant DNA methylation changes in genes that become downregulated (and upregulated) in C/EBPα-mediated transdifferentiation (14); however, the upregulation of a subset of myeloid cell-specific genes depends on the hydroxymethylation of cytosine residues in their promoters (15). Changes in histone modification also accompany both gene upregulation and downregulation during transdifferentiation (6, 14). Silencing of the B cell-specific gene program during transdifferentiation can also involve the participation of miRNAs. As indicated, miRNAs mainly exert a negative effect on gene expression, raising the possibility that they play a role in inhibiting B cell-specific genes such as TFs during transdifferentiation.

In the present report, we focus on the role of miRNA control in C/EBPα-mediated pre-B cell-to-macrophage transdifferentiation. We have determined that miRNA upregulation predominates over miRNA downregulation and that the most highly activated miRNAs are directly controlled by C/EBPα. Upregulated miRNAs such as miRNA 223 (miR-223), miR-34a, miR-21, and miR-22 directly target Lef1, Ikzf1, and Ebf1, among other key B cell-specific transcription factors. miR-223 and miR-34a, both targeting Lef1, had the strongest positive effect on the efficiency of transdifferentiation. Loss-of-function experiments confirmed the essential role of miR-34a and miR-223 for efficient transdifferentiation. Ectopic introduction of Lef1 delays transdifferentiation, similarly to blocking miR-223 and miR-34a function, and results in activation of B cell-specific markers in differentiated macrophages. Our results demonstrate a direct link between C/EBPα-mediated upregulation of miRNAs and the extinction of the expression of key elements of the B cell transcription program during transdifferentiation and, above all, a key role in ensuring proper macrophage function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

Normal primary macrophages and pre-B cells were derived from bone marrow, as described elsewhere (4). Primary B cells are CD19+ cells isolated from bone marrow, corresponding to approximately 15% pro-B cells, 60% pre-B cells, 20% immature B cells, and 5% mature B cells. The majority of bone marrow CD19+ cells are therefore pre-B cells. HAFTL cells are a fetal liver-derived, Ha-ras oncogene-transformed mouse pre-B cell line (16) and were provided by B. Birnstein. RAW 264.7 cells are a mouse leukemic monocyte macrophage cell line (17) and were provided by D. Cox. C10 cells (transduced with a murine stem cell virus [MSCV]-green fluorescent protein [GFP]-C/EBPα retroviral vector) and C11 cells (transduced with a MSCV-human CD4 [hCD4]-C/EBPα retroviral vector) had been previously developed (6) and consist of two clones derived from HAFTL pre-B cells infected with a β-estradiol-inducible viral system containing a fusion between C/EBPα and the estrogen hormone-binding domain (C/EBPαER).

Cell transdifferentiation and fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis.

C10 and C11 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 without phenol red (Lonza), supplemented with 10% charcoal-dextran-treated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone) and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Gibco), and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. They were induced by the addition of 100 nM β-estradiol (Calbiochem) and cultured with 10 ng/ml interleukin-3 (IL-3) and colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1) (Peprotech). Control cells were treated with 0.1% ethanol (solvent). Sorted primary B cells were infected for 2 days with C/EBPαER-GFP (30% to 70% infection efficiency), sorted again, induced with 100 nM β-estradiol, and grown on S17 cells in special induction medium containing 10 ng/ml IL-7, IL-3, CSF-1, stem cell factor (SCF), and Flt3 ligand (Peprotech). Standard experiments were performed under conditions of continuous stimulation with β-estradiol. For pulse-induction experiments, C10 or C11 cells were induced for 12 h with β-estradiol and then washed thoroughly and incubated with 10 μM of the β-estradiol antagonist ICI (Tocris Bioscience).

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, quantitative PCR, and profiling of miRNAs.

Total RNA was isolated using TriPure isolation reagent (Roche), according to the manufacturer's recommendations, and cDNA was produced from total RNA treated with DNase using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen Co.) for mRNA and primary-microRNA (pri-miRNA) analyses. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed on a LightCycler 480 II system using LightCycler 480 SYBR green mix (Roche). Reactions were carried out in triplicate, and data were analyzed using the standard curve method (18). For mouse miRNA profiling, realiquoted locked nucleic acid (LNA) miRNA-specific PCR primers sets in 384-well PCR plates were used (Exiqon). Total RNA (20 ng) was reverse transcribed in 10-μl reaction mixtures using a miRCURY LNA universal RT miRNA PCR, polyadenylation, and cDNA synthesis kit (Exiqon), and the cDNA was diluted 80-fold. Each PCR was carried out in a total volume of 10 μl using 4 μl of the diluted cDNA according to the miRCURY LNA universal RT miRNA PCR protocol. The amplification patterns were used to evaluate melting curves, and crossing-point (Cp) values for each miRNA were determined with LightCycler 480 software. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and bar graphs correspond to independent biological samples. Primers for primary-miR quantification included the following: pri-miR-21 (forward, GACATCGCATGGCTGTACC; reverse, CAAAATGTCAGACAGCCCATC), pri-miR-22 (forward, CTCCCACACCCTCACCTG; reverse, GCAGAGGGCAACAGTTCTTC), pri-miR-106-363 (forward, GGACACTTTGGGGGTTAGGT; reverse, TCTCCTAGCTGGTGGAGGAG), pri-miR-34a (forward, CAGCCTCTCCATCTTCCTGT; reverse, CAACAACCAGCTAAGACACTGC), and pri-miR-223 (forward, AGGTTCCTGATCTGGCCATC; reverse, TGAGCCACACTTGGGGTATT).

ChIP-seq analysis.

We employed the Integrated Genome Browser tool (19) to visualize chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (Chip-seq) data and peak representation for C/EBPα, PU.1, and RNA polymerase II (Pol II) binding and histone modifications, using data from C. van Oevelen and T. Graf (unpublished data).

Transfection with miRNA mimics and inhibitors.

miRNA mimics (Ambion) (5 nM) or miRCURY LNA microRNA power inhibitors (Exiqon) (50 nM) were transfected into C10 or C11 or into RAW cells using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's protocol. Experiments were also performed using 5 nM control mimic or 50 nM control LNA inhibitor.

Lef1 constructs, retroviral supernatant generation, and cellular transduction.

The coding DNA sequence (CDS) of Lef1 and the Lef1-3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) (containing the CDS plus the 3′UTR) sequences were amplified by PCR using Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Thermo Scientific) following the manufacturer's instructions. Primers used were Lef1 CDS (forward, ATGCCCCAACTTTCCGGAGGAGGCGGC; reverse, TCAGATGTAGGCAGCTGTCATTCTGGG) and Lef1 CDS + 3′UTR1 (forward, ATGCCCCAACTTTCCGGAGGAGGCGGC; reverse, TTCCGAAACAACCGTTTTCGGCTTTC). Sequences were subcloned in pMSCV-GFP vector and verified by sequencing. For retrovirus generation, the pMSCV-GFP (Mock), pMSCV-GFP-Lef1-CDS, and pMSCV-GFP-Lef1-3′UTR plasmids were transfected into the Platinum A-packaged cell line and supernatants were collected 48 to 72 h posttransfection. C11 cells were spin infected and treated 48 h later with β-estradiol continuously or in a 12-h pulse, as described above.

Flow cytometry.

C10 cells were transfected with miRNA mimics or miRNA inhibitors, and C11 cells were infected with retroviral supernatants, as described above, and induced to transdifferentiate. Cells were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against Mac-1 and CD19 (BD Pharmingen) 0, 24, and 48 h later. Mac-1 expression and CD19 expression were monitored on a Gallios flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter) and analyzed by FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc.). All experiments were performed in triplicate, and bar graphs correspond to independent biological samples.

Luciferase assays.

The putative miRNA binding sites in the 3′UTRs of Lef1, Ikzf1, Sfpi1, Cebpa, and Ebf1 were amplified by PCR from genomic DNA derived from HAFTL cells. The PCR products were cloned into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega), and 4 to 7 point mutations were introduced into each target site by site-directed mutagenesis. Each of the fragments containing the 3′UTR of putative miRNA binding sites was cloned into psiCHECK-2 vector (Promega). 293T cells were cultured for 24 h and then cotransfected using Lipofectamine RNAimax with 10 ng of psiCHECK-2 vector containing wild-type or mutant 3′UTR plus 50 nM miRNA mimics per well. The luciferase analysis was performed 48 h later using a dual-luciferase reporter assay (Promega). Primers for luciferase assays include the following: miR34 matching site of the Lef1 3′UTR (forward, AATCTAGAAACCTTACCCTGAGGTCACTG; reverse, AAGCGGCCGCCGTTTTCGGCTTTCTTT), miR-18b matching site of the Sfp1 3′UTR (forward, AATCTAGAAACCGAGGGTCAGCCTGGCTTA; reverse, ATGCGGCCGCGAGGGGGTGGGGAGGAA), miR-363 matching site of the Cebpa 3′UTR (forward, TATCTAGATCCCAAATATTTTGCTTTATCATCCG; reverse, AAGCGGCCGCATAAAATGGTGGTTTAGC), miR-21 matching site of the Ebf1 3′UTR (forward, ATCTAGACTTTCTTTTCTTAAGCTTAACTCTG; reverse, AGCGGCCGCTAAAAACATAAATTAAAACATGGAG), miR-22 matching site of the Ikzf1 3′UTR (forward, ATCTAGAATTTACACTGAAGAGAGAAAAATT; reverse, AGCGGCCGCCTTGGACCACACTTAATGGCTC), miR-223 matching site of the Lef1 3′UTR (forward, AGCGGCCGCGATGGAAGCTTGTTGAAACC; reverse, ACTCGAGGAGGTGGCAGTGACTGTGTC), and miR-34a matching site of the Ikzf1 3′UTR (forward, CTCGAGGAATTGTAAATAGTGGCTTCAG; reverse, GCGGCCGCAAAGGTGTGCAAATTGACATTT).

LPS-induced inflammatory cytokines.

C10 cells were transfected with miRNA inhibitors as described above and were induced to transdifferentiate. They were incubated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Sigma) (1 μg/ml) for 6 h, 48 h after induction. RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and qRT-PCR were performed as described above. Primer sequences include the following: Tnf-α (forward, CGCTCTTCTGTCTACTGAACTT; reverse, GATGAGAGGGAGGCCATT), Il1b (forward, CCAAAATACCTGTGGCCTTGG; reverse, GCTTGTGCTCTGCTTGTGAG), Il6 (forward, GAGGATACCACTCCCAACAGACC; reverse, AAGTGCATCATCGTTGTTCATACA), and Ccl3 (forward, ACAGCCGGAAGATTCCACGCC; reverse, TCAGGAAAATGACACCTGGCTGGG).

RESULTS

C/EBPα-mediated transdifferentiation of pre-B cells into macrophages is associated with predominant upregulation of miRNAs.

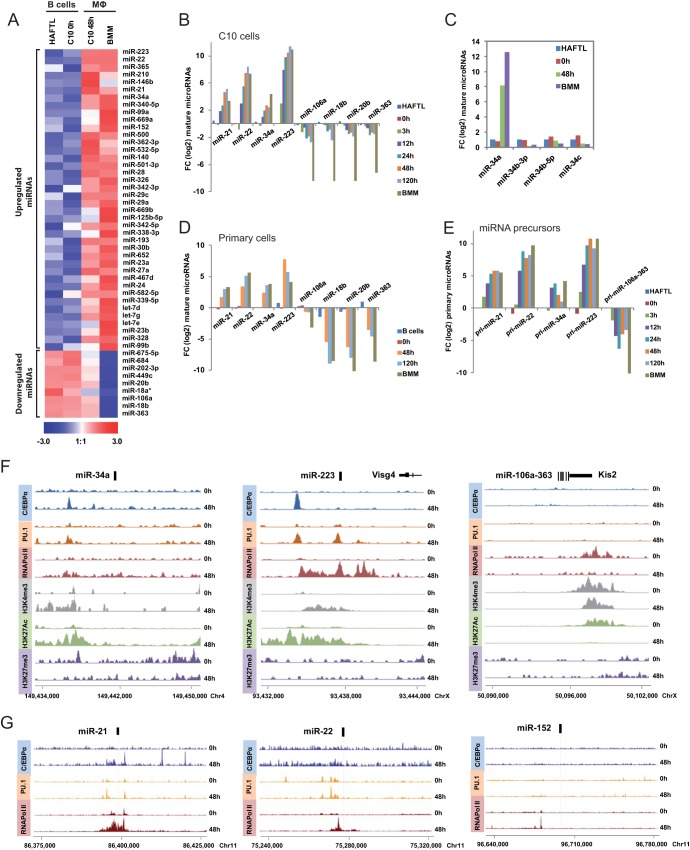

To understand the contribution of miRNAs in C/EBPα-induced B cell-to-macrophage transdifferentiation, we first performed miRNA profiling by using a quantitative PCR-based panel containing more than 375 miRNAs. The analysis was first done comparing untreated C10 cells, which correspond to pre-B cells, with C10 cells 48 h after estradiol-mediated induction of C/EBPα, when C10 cells exhibit the phenotype of fully reprogrammed macrophages. Analyses also included the parental pre-B cell line used to generate the inducible C/EBPα system, i.e., HAFTL cells, and bone marrow macrophages (BMM). Analysis of the data showed that miRNA upregulation predominates over miRNA downregulation. Specifically, we observed that 40 miRNAs became upregulated between 2- and ∼8,000-fold and reached levels comparable to those observed in bone marrow macrophages. In contrast, only 5 miRNAs were downregulated >0.5-fold during transdifferentiation (Fig. 1A). In addition, we also observed a modest but coordinated downregulation during transdifferentiation of four of the miRNAs (miR-106a, miR-18b, miR-20b, and miR-363) within cluster miR-106a-363 located in the X chromosome (Fig. 1A). The coordinated downregulation of the miR-106a-363 cluster is reminiscent of what has been reported for its paralogous miR-17-92 cluster, which is epigenetically silenced during macrophage differentiation (20). However, miRNAs in the miR-17-92 cluster do not undergo any change in expression in C/EBPα-mediated pre-B cell-to-macrophage transdifferentiation (not shown).

FIG 1.

MicroRNA expression profiling during pre-B cell-to-macrophage transdifferentiation. (A) Heat map comparing pre-B cells (HAFTL B cells and C10 B cells at 0 h) and bone marrow macrophages (BMM) and C10-reprogrammed macrophages (both indicated as MΦ). In the scale at the bottom, expression values relative to the individual mean value are displayed in a linear scale from blue (low expression) to red (high expression). (B) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of selected miRNAs at different times (0, 3, 12, 24, 48, and 120 h postinduction) in C10 pre-B cells together with HAFTL pre-B cells and BMM. The levels of U6 RNA were used for normalization. FC, fold change. (C) Comparison of expression changes of miR-34a with those of other miR-34 family members (miR-34b-3p, miR-34-5p, and miR-34c), as extracted from the LNA miRNA-specific 384-well PCR plate data sets. Again, U6 RNA expression levels were used for normalization. (D) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of selected miRNAs over time (0, 48, and 120 h postinduction) following infection of primary bone marrow CD19+ B cells with the C/EBPαER-GFP construct. U6 RNA levels were used for normalization. (E) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of primary miRNA precursors (pri-miRNAs) at different times (0, 3, 12, 24, 48, and 120 h) following induction of transdifferentiation of C10 pre-B cells, together with HAFTL pre-B cells and bone marrow macrophages. The levels of Hprt1 were used for normalization. (F) ChIP-seq data profiles for C/EBPα, PU.1 and Pol II binding, and enrichment of H3K4me3, H3K27me3, and H3K27Ac in selected upregulated miRNAs (miR-34a and miR-223) and downregulated miRNAs in the miR106a-363 cluster. The localization of the mature forms of miRNAs is indicated with a black bar. Genomic coordinates are also indicated. (G) ChIP-seq data profiles for C/EBPα and PU.1 and Pol II binding for three additional upregulated miRNAs, miR-21, miR-22, and miR-152.

Several of the upregulated miRNAs have been implicated in myeloid differentiation before. Thus, miR-223, which is overexpressed >8,000-fold, is regulated by C/EBPα and has been proposed to behave as a myeloid regulator (21, 22). Another of the most strongly upregulated miRNAs, miR-34a, is also a direct target of C/EBPα that plays a role in granulocyte differentiation (23). In fact, constitutive expression of miR-34a in the bone marrow led to a decrease of B lymphocyte levels (24) through downregulation of Foxp1. miR-21 and miR-22 are two other interesting miRNAs that are strongly upregulated during transdifferentiation. miR-21 is a promonocytic effector (25), and miR-22 has been described as a signature miRNA associated with common myeloid/erythroid progenitor commitment (26) and targets TET2 to promote hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and transformation (27). Both undergo a >10-fold increase in their expression levels during transdifferentiation.

As indicated, miR-223, miR-34a, miR-21, and miR-22 were among the miRNAs displaying the highest levels of overexpression, comparing C10 reprogrammed macrophages with C10 pre-B cells (before β-estradiol treatment). A time course analysis of these miRNAs showed that the largest increase occurred about 3 to 12 h after C/EBPα induction (Fig. 1B). The changes observed were highly specific, as illustrated by the fact that miR-34a, but not other members of the miR-34 family, became upregulated (Fig. 1C). To validate the relevance of our findings further, we also tested changes of these miRNAs in transdifferentiation experiments with primary cells. Comparison of primary CD19+ B cells and reprogrammed macrophages following ectopic expression of C/EBPα showed similar expression changes for the 8 miRNAs tested (Fig. 1D), reinforcing the notion of the robustness of these changes in C/EBPα-mediated transdifferentiation.

Finally, qPCR analysis of the levels of long miRNA precursors, termed primary miRNAs (pri-miRNAs), during C/EBPα-induced C10 cell transdifferentiation showed dynamics of changes similar to those observed for mature miRNAs, suggesting that they are subject to transcriptional control (Fig. 1E) and not to changes in their stability.

Altogether, our observation indicating the prevalence of miRNA upregulation during C/EBPα-mediated transdifferentiation of pre-B cells suggests a potential role for these molecules in repressing and extinguishing the B cell-specific genetic program, thereby facilitating reprogramming into macrophages.

C/EBPα directly targets the upregulation of miR-34a, miR-223, miR-21, and miR-22.

During pre-B cell-to-macrophage conversion, C/EBPα helps establish the myeloid cell-characteristic gene program. However, the mechanism by which C/EBPα dramatically shuts down the B cell-specific gene program is less well understood. Our findings prompted us to consider whether the upregulated miRNAs were targets of C/EBPα and, therefore, part of the mechanism responsible for B lymphocyte gene silencing.

To test this possibility, we investigated the direct binding of the 40 upregulated and 9 downregulated miRNAs by C/EBPα and PU.1 by inspecting ChIP-seq data from a parallel study of C/EBPα-induced transdifferentiation (van Oevelen and Graf, unpublished). As indicated above, two of the upregulated miRNAs, miR-34a and miR-223, were already known to be direct targets of C/EBPα (21, 23). Analysis of the ChIP-seq data confirmed the direct binding of C/EBPα to the miR-34a- and miR-223-encoding genes (Fig. 1F). In addition, two additional miRNAs (miR-21 and miR-22) also recruited C/EBPα within a 2,000-bp window of their genomic location (where their transcription start site [TSS] is likely to be located) (Fig. 1G). In contrast, C/EBPα was not bound at any of the remaining upregulated miRNAs (example in Fig. 1G) or at any of the downregulated miRNAs (example in Fig. 1F, right panel). Binding of C/EBPα at the loci encoding miR-34a, miR-223, miR-21, and miR-22 occurred concomitantly with the binding of PU.1 and Pol II (Fig. 1F and G), which was already present as early as 3 h after induction (not shown). Changes in the occupancy by Pol II at both upregulated and downregulated miRNAs reinforced the notion that their changes in expression are controlled at the transcriptional level. However, as mentioned above, many of these miRNA genes do not seem to be directly bound by C/EBPα.

We observed changes in histone modifications near the C/EBPα binding sites and around the miRNA loci. For instance, miRNAs that became upregulated, such as miR-223 and miR-34a, underwent enrichment in activating histone marks such as H3K4me3 and H3K27Ac, whereas miRNAs that became downregulated during transdifferentiation displayed a decrease in these marks, and a loss of Pol II binding, despite the absence of changes of C/EBPα or PU.1 (Fig. 1F).

In summary, the analysis of the binding of C/EBPα, PU.1, and Pol II and of changes in histone modifications revealed the direct involvement of different epigenetic regulatory elements near the putative TSS of miRNAs undergoing expression changes. Strikingly, only a selected group of upregulated miRNAs (miR-34a, miR-223, miR-21, and miR-22) displayed direct C/EBPα binding, supporting the notion that these play a key role in cellular transdifferentiation.

miR-34a and miR-223 expression is required for proper transdifferentiation of pre-B cells into macrophages.

To investigate the role of individual miRNAs in cellular transdifferentiation, we first tested the effects of transfecting miRNA mimics in C10 pre-B cells. The transfection efficiency of mature miRNAs was assessed by FACS analysis using control fluorophore-labeled miRNAs, revealing that over 75% of HAFTL/C10 pre-B cells became positive (Fig. 2A). To select the optimal time for miRNA mimic expression following transfection, we performed quantitative RT-PCR analysis of each miRNA. These analyses showed a peak signal at 24 h (not shown), which we chose for the following experiments. We then introduced individual miRNAs into C10 cells, and after 24 h we induced transdifferentiation with β-estradiol. Under normal conditions, sustained treatment of C10 cells with β-estradiol results in highly efficient C/EBPα-mediated transdifferentiation that can be monitored by FACS, where it is possible to measure a substantial increase in Mac-1 expression and downregulation of CD19 within 1 day. After 3 days, essentially 100% of the cells showed reciprocal regulation of these markers. Initially, we investigated the effects of individual transfections with miRNA mimics corresponding to the four upregulated miRNAs that are direct C/EBPα targets (miR-223, miR-34a, miR-21, and miR-22) and one of the members of the downregulated cluster (miR-18b), since miR-18b was previously known to be downregulated in another myeloid/erythroid model of differentiation (28). Only three of these five miRNAs (miR-34a, miR-223, and miR-18b) had strong effects on transdifferentiation (Fig. 2B). Specifically, we observed that overexpression of both miR-34a and miR-223 has a positive effect resulting in the acceleration of the transdifferentiation process (36.9% ± 3.02% of miR-34a-transfected cells and 27.4% ± 1.05% of miR-223-transfected cells versus 15.5% ± 0.65% of mock-transfected C10 cells are reprogrammed at 24 h), whereas miR-18b overexpression (which is downregulated during transdifferentiation) has a negative effect (only 7.8% ± 0.9% are reprogrammed at 24 h) (Fig. 2B). The effects of transfecting with miR-34a and miR-223 mimics were more apparent as a faster increase for the surface macrophage marker Mac-1 (Fig. 2C), whereas the effect of transfecting with miR-18b was manifested as a delay in the downregulation of the CD19 marker (Fig. 2C).

FIG 2.

Influence of miRNAs in modulating pre-B cell-to-macrophage differentiation. (A) Efficiency of miRNA analogues (mimics) in transfection in HAFTL pre-B cells using a Cy3-labeled negative-control small RNA. Representative FACS plots corresponding to untreated cells and cells 24 h after transfection are shown. FS INT LIN, forward scatter integration linear; FL2 INT LOG, fluorescence channel 2 (Cy3) integration logarithmic. (B) Effect of microRNA mimics in transfection in C10 pre-B cells for miR-21, miR-22, miR-34a, miR-223, and miR-18b on reprogramming at 24 h postinduction measured by FACS (estimating the absolute cell counts of reprogrammed macrophages from the Mac-1-positive and CD19-negative cell fraction). (C) Detailed representation of the effect of individual transfections with miR-34a, miR-223, and miR-18b mimics on the CD19 and Mac-1 levels during transdifferentiation at 24 h postinduction measured by FACS analysis. Data are presented as the means of absolute cells counts ± standard errors (SE) of three biological replicates. (D) Representative FACS plots of CD19 and Mac-1 marker levels in control, miR34-a-, miR-223-, miR34a plus miR-223-, and miR-18b-transfected C10 B cells at 0, 24, and 48 h postinduction. The percentage of reprogrammed macrophages (the Mac-1-positive and CD19-negative cell fraction) is highlighted in red for each condition. (E) Effects of specific inhibitors of miRNAs or antagomirs for miR-34a (a.34a), miR-223 (a.223), and miR-18b (a.18b) on transdifferentiation measured by FACS at 24 h postinduction. Data are presented as the means of absolute cells counts ± SE of three biological replicates. (F) Effects of specific inhibitors of miR-34a (a.34a) and miR-223 (a.223) on mRNA levels of Tlr4 and Cd14 measured by qRT-PCR 48 h postinduction, when cells were fully reprogrammed. The levels of Hprt1 were used for normalization. (G) Effects of specific inhibitors of miR-34a (a.34a) and miR-223 (a.223) on the ability of reprogrammed macrophages to respond to LPS, measured by qRT-PCR to check the expression of proinflammatory cytokine genes (Il1b, Il6, the tumor necrosis factor alpha gene [Tnf-α], and Ccl3). The levels of Hprt1 were used for normalization. In all cases, error bars represent standard errors, and a single asterisk and double asterisks indicate P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively, in comparisons with control cells (t test).

Combined transfection with miR-34a and miR-223 had an effect on the levels of reprogrammed macrophages similar to that observed with individual transfections (Fig. 2D), suggesting that both miRNAs act through the same pathway.

To establish definitively the functionality of miR-34a and miR-223 in the reprogramming of pre-B cells into macrophages, we performed loss-of-function experiments. To this end, we transfected C10 pre-B cells with specific inhibitors or antagomirs for either miR-34a (a.34a) or miR-223 (a.223). The ability of these two miRNAs to upregulate Mac-1 was reduced 4 times and 3 times, respectively, relative to that of control C10 cells at 24 h after β-estradiol addition (Fig. 2E), further demonstrating the functional effect on the participation of these miRNAs by the ability of the cells to become reprogrammed macrophages. As expected, no effects on transdifferentiation were observed using a specific inhibitor for miR-18b, which becomes downregulated during transdifferentiation.

Next, we wondered whether the effects of these two miRNAs also affect the functionality of the reprogrammed macrophages, beyond their effects on transdifferentiation. In these experiments, we treated C10 B cells with miR-34a or miR-223 inhibitors for 24 h and then induced transdifferentiation with b-estradiol and analyzed the expression of inflammatory cytokines 48 h after induction. Treatment with inhibitors for miR-34a and miR-223 showed a reduced ability of transdifferentiated cells to respond to Gram-negative bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation, estimated from measurements of the levels of IL1b, Il6 and Tnf-α, and Ccl3 (Fig. 2F). These cytokine genes are expressed through Tlr4, which binds LPS and results in macrophage activation, and Cd14, which acts as a coreceptor in conjunction with Tlr4. We observed that cells treated with inhibitors for miR-34a and miR-223 had lower levels of Tlr4 and Cd14, which explains the deficient inflammatory response of reprogrammed macrophages that arises when the two miRNAs are inhibited (Fig. 2E). Taken together, our results demonstrate that miR-34a and miR-223 are both involved in reprogramming pre-B cells into macrophages and that their absence also compromises key functions of reprogrammed macrophages.

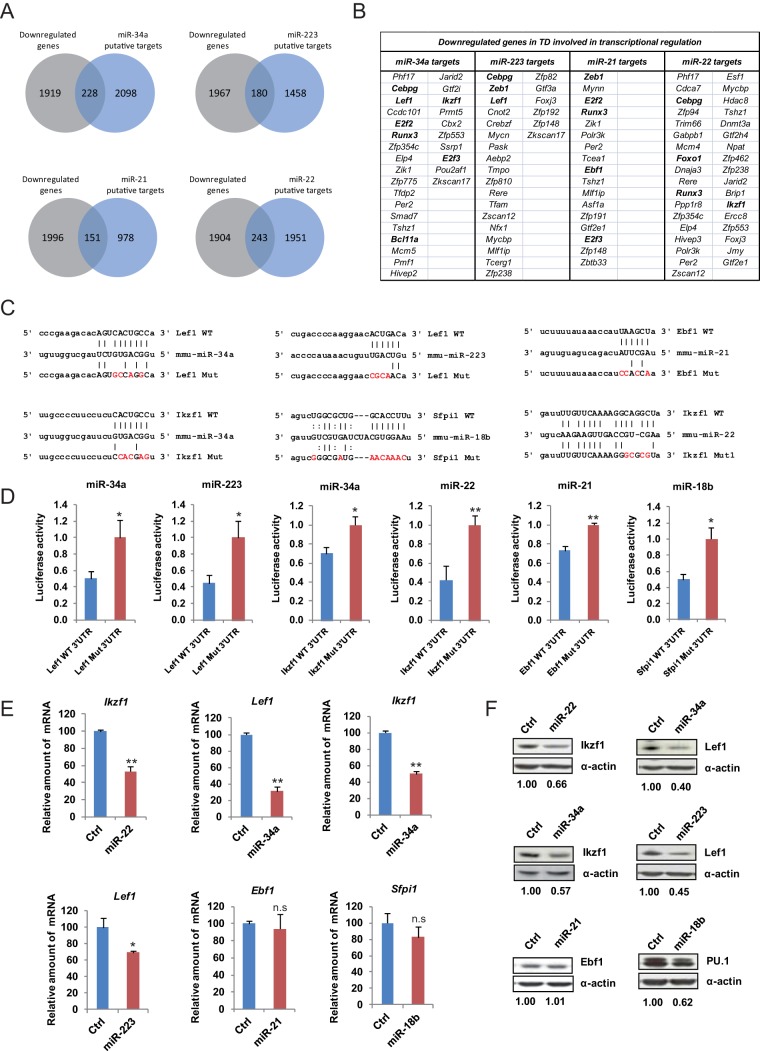

miR-34a and miR223 target and downregulate the key lymphoid transcription factors Lef1 and Ikzf1.

Our results demonstrated that two of the most strongly activated miRNAs, miR-34a and miR-223, have a functional effect on transdifferentiation when ectopically expressed and when inhibited in C10 pre-B cells. To identify targets of miR34-a and miR-223 (and other upregulated miRNAs), we first retrieved a list of putative targets using miRWalk (29), which contains prediction databases such as TargetScan (30), miRDB (31), and others, as well as information on validated targets. We then linked the list of potential targets with our previously reported high-throughput data on expression changes during transdifferentiation (6), assuming an inverse relationship between the levels of a given miRNA and the expression levels of its putative targets. For this analysis, we imposed the criteria that the putative targets should be predicted by at least four databases and that downregulation was defined as a minimum 0.5-fold change. Applying these conditions, we identified a number of putative downregulated targets for each overexpressed miRNA (Fig. 3A). We then used the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) to identify functional categories. This tool revealed a highly significant enrichment of transcription factor-encoding genes among those on the list of putative targets (Fig. 3B). For instance, miR-223 was found to potentially target the 3′UTRs of Lef1, Zeb1, and Cebpg and miR-34a to target Lef1, Runx3, Bcl11a, and Ikzf1. Likewise, we found that miR-21 could be targeting Ebf1 and Runx3 and that miR-22 targets Foxo1, Runx3, and Ikzf1. Finally, when analyzing the miRNAs included in the downregulated miR-106a-363 cluster, we found that miR-18b displays base complementarity with the 3′UTR of PU.1 and that miR-363 potentially targets C/EBPα.

FIG 3.

Analysis of miRNA targets. (A) Venn diagrams showing the overlap between miRNA putative targets (determined from at least 4 miRNA target prediction databases using the miRWalk tool) of the most highly upregulated miRNAs and genes that are downregulated (by at least 0.5-fold at a false-discovery rate [FDR] of <0.05) during transdifferentiation. (B) A selection of genes that are putative targets for miR-34a, miR-223, miR-21, and miR-22 and are downregulated during transdifferentiation (TD). Only targets within the transcriptional regulation category are presented (gene ontology: 000635). Relevant lymphoid cell-specific transcription factors from the list of targets are highlighted in bold. (C) Schematic representations of the pairing between different miRNAs (miR-34a, miR-223, miR-21, miR-22, and miR-18b) and the 3′UTR (wild-type and mutant forms) of putative target genes. (D) Luciferase assays on 293T cells transfected with reporter constructs containing the 3′UTR of putatively targeted transcription factors (wild-type or mutant forms) and miR-34a, miR-223, miR-21, miR-22, and miR-18b mimics. (E) Quantitative RT-PCR in C10 pre-B cells transfected with each of the miRNA mimics, showing the effect on potentially targeted transcription factors. The levels of Hprt1 were used for normalization. (F) Western blot analysis of C10 pre-B cells transfected with each of the miRNA mimics, showing the effect in protein levels of potentially targeted transcription factors. In all cases, representative images are shown. Error bars represent the standard errors, and single asterisks and double asterisks indicate P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively, in comparisons with control cells (t test).

To validate these putative targets, we performed luciferase reporter assays using a vector containing the renilla luciferase coding region plus the wild-type (WT) or a mutant form (Mut) of the putative 3′UTR target sites of each potentially targeted transcription factor (Fig. 3C). We carried out these assays in 293T cells in the presence of transfected mature forms of each miRNA (mimics) and the luciferase reporter for each of their putative targets. These assays confirmed that miR-34a and miR-223 both target Lef1 (Fig. 3D) and also confirmed that miR-223 targets Mef2c (not shown). In addition, we demonstrated that miR-34 and miR-22 both target Ikzf1, that miR-21 targets Ebf1, that miR-18b targets PU.1 (Fig. 3D), and that miR-363 targets C/EPBa (not shown).

To obtain further evidence of the in vivo effect of the miRNAs on their putative targets, we performed qRT-PCR and Western blot analysis in C10 cells transfected with mimics for each of the miRNAs named above. miR-34 overexpression results in a decrease of Lef1 and Ikzf1 levels (Fig. 3E and F). Introduction of miR-223 also reduces Lef1 levels. Ikzf1 levels were also reduced following transfection of miR-22. Introduction of miR-21 did not have any effects on Ebf1 levels in C10 cells transfected with miR-21 (Fig. 3E). C/EBPα levels did not display any changes following transfection with the miR-363 mimic (not shown). Finally, miR-18b transfection resulted in downregulation of PU.1. Taken together, our data demonstrate that several of the miRNAs upregulated during B cell-to-macrophage conversion target and reduce the expression levels of key factors in B cell biology, including Lef1 (miR-34 and miR-223) and Ikzf1 (miR-34a and miR-22).

Increases in miR-34a and miR-223 levels correlate with a sharp decrease in Lef1 and Ikzf1 levels.

We next compared the dynamics of the expression changes of the candidate target lymphoid factors Lef1 and Ikzf1 with their corresponding validated regulators miR-34a and miR-223 during transdifferentiation. The comparative analysis of dynamic changes for each miRNA in parallel with their targeted transcription factors showed that a decrease in the mRNA levels of Lef1 and Ikzf1 preceded an increase in miRNA levels (Fig. 4A). However, the analysis at the protein level showed kinetics similar to those of miRNA expression (Fig. 4B). The findings suggested that transcriptional control might mark initial changes in the expression of transcription factors such as Lef1, Ikzf1, and others, as mRNA expression changes precede miRNA expression changes. However, miRNAs could play a crucial role in ensuring that low levels of these factors are maintained after differentiation, thereby strengthening macrophage function.

FIG 4.

(A) Comparison of the dynamics of each of the miRNAs and their targets at the mRNA and protein levels during transdifferentiation of C10 pre-B cells. The levels of Hprt1 were used for normalization of qRT-PCR data. (B) Western blot illustrating the levels of Left and Ikzf1 during transdifferentiation. Lef1 disappears almost completely during this process.

Inhibition of Lef1 through miRNAs is required for proper macrophage differentiation and function.

Our analysis of miRNA targets showed that both miR-34 and miR-223, the two upregulated miRNAs with the strongest effect on transdifferentiation, target transcription factor Lef1. In addition, Lef1 is one of the B cell genes showing the sharpest decline in expression during transdifferentiation and is completely absent from reprogrammed macrophages (Fig. 4B) (see also reference 6). Previous studies on Lef1 have largely been restricted to its role in lymphoid lineages, where it has been shown to have a function in T cell development and to affect proliferation and apoptosis in pro-B cells (11). However, it also plays a pivotal role in granulopoiesis, and recent data suggest a more complex role in hematopoiesis (12, 32, 33).

To investigate how Lef1 affects transdifferentiation, we infected C11 pre-B cells with a retroviral vector containing the Lef1 DNA coding sequence (CDS) and tested its effect on cellular transdifferentiation. The ectopic expression of Lef1-CDS had a negative effect on Mac-1 expression and a positive effect on CD19 expression, reducing the proportion of reprogrammed macrophages by around 30% at 48 h (Fig. 5A). In addition, the ability of C11 pre-B cells constitutively expressing Lef1-CDS to transdifferentiate was virtually abolished in performing a 12-h β-estradiol pulse to transiently activate C/EBPα. Strikingly, the infection of C11 pre-B cells with a form of Lef1 containing the 3′UTR, and therefore the target sites for miR34a and miR223, had no effect on transdifferentiation efficiency (Fig. 5A), indicating that miRNA overexpression mediates degradation of Lef1 by binding to its 3′UTR, thereby neutralizing its negative effect on transdifferentiation. A decrease in transdifferentiation of cells transfected with Lef1-CDS occurred in parallel with increased expression of the B cell markers Cd19, Ikzf3, E2a, and Pax5 (Fig. 5B). These markers had only a very moderate increase in level with respect to control cells in those transfected with Lef1-3′UTR. The notion of the participation of miRNAs in wiping out Lef1 expression was further supported by monitoring the protein levels in cells transfected with Lef1-CDS and those transfected with the Lef1-3′UTR construct (Fig. 5C). Lef1 protein levels decreased faster after induction in the latter group of cells, since Lef1 mRNA containing 3′UTR is susceptible to being regulated by both miR-34a and miR-223 (and perhaps additional miRNAs), unlike the Lef1 mRNA containing only the CDS (lacking miRNA binding sites) (Fig. 5C).

FIG 5.

Influence of Lef1 on transdifferentiation. (A) Effects on transdifferentiation of infection of C11 pre-B cells with a retroviral vector expressing Lef1. Empty vector pMSCV-GFP (Mock), the vector containing the coding DNA sequence (CDS) of Lef1 pMSCV-GFP-Lef1-CDS (Lef1 CDS), and the vector containing the coding DNA sequence of Lef1 plus its 3′UTR pMSCV-GFP-Lef1-3′UTR (Lef 3′UTR) were used. The absolute cell counts of reprogrammed macrophages correspond to Mac-1-positive/CD19-negative cells. Both “continuous” and “pulse” experiment results are shown (see Materials and Methods). (B) Effects on expression levels of additional B cell transcription factors of infection of C11 pre-B cells with retroviral vector expressing mock-infected (Mock), Lef1 CDS, or Lef1 3′UTR constructs. The levels of Hprt1 were used for normalization. (C) Effects of transdifferentiation on levels of Lef1 protein levels when C11 pre-B cells were infected with Mock, lef1 CDS, or Lef1 3′UTR constructs. (D) Effects on the CD19 levels of transfecting RAW macrophages with Mock, Lef1-CDS, or Lef1-3′UTR constructs. (E) Effects on the mRNA Lef1 levels of transfecting RAW macrophages with miRNA inhibitors for miR-34a (a.34a) and miR-223 (a.223). (F) ChIP-seq data corresponding to the C/EBPα, H3K27Ac, and Pol II occupancy at the Lef1 promoter. (G) Schematic representation of the control at the transcriptional and miRNA level of Lef1 during pre-B cell-to-macrophage transdifferentiation. Error bars represent the standard errors, and single asterisks and double asterisks indicate P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively, in comparisons with control cells (t test).

We next tested the effect of expressing Lef1 in the RAW macrophage cell line. Transfection of macrophages with a vector expressing the Lef1-CDS caused an increase in CD19 protein levels at the cell surface, as measured by flow cytometry (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, when we used a vector expressing a construct containing the Lef1 coding region plus its 3′UTR, the expression of CD19 was partially abolished (Fig. 5D), providing further evidence of the role of these miRNAs in eliminating the presence of Lef1, and perhaps other B cell-specific transcription factors, during the conversion to myeloid cells. Importantly, transfection of RAW cells with specific miR-34a and miR-223 inhibitors resulted in an increase of Lef1 transcript (Fig. 5E), demonstrating the requirement for both miRNAs to ensure the complete erasure of Lef1 in a macrophage cell context.

Finally, we inspected the potential binding of C/EBPα to Lef1 during pre-B cell-to-macrophage transdifferentiation. We observed that 1 h after induction, C/EBPα was already bound to the Lef1 promoter. Binding was accompanied by changes in histone modifications at the promoter region of Lef1 in the direction of repression, reinforcing the notion that Lef1 repression is needed to accompany transdifferentiation (Fig. 5F), and indicating that multiple mechanisms are used to silence Lef1.

Taken together, our findings indicate that miR-34 and miR-223 both play a direct role in B cell-to-macrophage transdifferentiation targeting Lef1, whose expression is erased through direct transcriptional control mechanisms and through miRNA-mediated control (Fig. 5G).

DISCUSSION

C/EBPα-induced transdifferentiation of pre-B cells into macrophages involves establishing the myeloid cell-specific genetic program and extinguishing the B lymphocyte-characteristic gene program. In this regard, it was a safe prediction that a myeloid transcription factor such as C/EBPα would directly or indirectly mediate the upregulation of macrophage-specific genes. However, the outstanding matter concerns which mechanisms are employed by C/EBPα to bring about the shutting down of key lymphocyte genes. In this report, we have demonstrated the implication of three major players in this process: two miRNAs, miR34a and miR-223, and one lymphoid transcription factor, Lef1, targeted by the two miRNAs.

Previous studies have described the relevance of miR-34a and miR-223 in hematopoietic differentiation and function. First, miR-223 appears to be a key factor in the myeloid compartment. For instance, it regulates human granulopoiesis (34) and its deficiency results in greater eosinophil progenitor proliferation (35). However, it also has specific roles in macrophage differentiation and function. For instance, miR-223 is a regulator of macrophage polarization (36). On the other hand, miR-34a is activated by C/EBPα in granulopoiesis, targeting E2F3 and blocking myeloid cell proliferation (23). However, a link to Lef1 has not been established in these studies.

Our results here show that miR-34a and miR-223 strongly influence the ability of pre-B cells to transdifferentiate into macrophages. The kinetics of expression changes of these miRNAs, where upregulation of miR-223 is faster than that of miR-34a, suggests that the former might play more of a role in establishing the new lineage and that miR-34a might help maintain it. Similar delayed kinetics has previously been reported for miR-34a regulation of MYB in regulating the differentiation of bipotent erythroid-megakaryocyte precursor cells to megakarocytes (37). In the context of our model, the analysis of targets of these two and other highly upregulated miRNAs indicates that a number of lymphoid cell-specific TFs are targeted by them. Given the repressive role of miRNAs, we propose that the predominance of miRNA upregulation relative to downregulation during transdifferentiation indicates that the major effect of miRNA control during C/EBPα-induced transdifferentiation is the extinction of the lymphoid program and the reinforcement of the macrophage program by buffering leaky inappropriate transcripts. This is also compatible with the observation that transdifferentiation occurs without overt retrodifferentiation (9), that is, without the transient expression of stem and lymphoid progenitor cell markers.

We have demonstrated that Lef1 is targeted by miR-34a and miR-233. In the C/EBPα-mediated pre-B cell-to-macrophage transdifferentiation, Lef1 is one of the factors that becomes most rapidly downregulated and both its mRNA and protein levels are almost entirely abrogated during this process. Moreover, constitutive expression of Lef1 in C10 pre-B cells has an effect on transdifferentiation similar to the specific inhibition of miR-34a and miR-223 and leads to overexpression of B cell markers. Interestingly, Lef1 also induced upregulation of the CD19 gene in macrophages.

Lef1 was initially described as a T cell lymphoid cell-specific factor (13) but also plays a crucial role in B lineage development, where it is mainly expressed in B cell precursors and becomes downregulated during the progression into mature B and plasma cells (38). The finding that it is also downregulated, at least in part, by the action of miR-34a and miR-223 during transdifferentiation of B cell to macrophages raises the possibility that they also play a role in normal B cell differentiation. Recent reports have shown that overexpression of Lef1 is associated with different types of lymphoid malignancies, including chronic lymphocytic leukemia (39), in which it is a prosurvival factor, as well as in T cell malignancies (40). Intriguingly, some reports have shown that Lef1 is a decisive transcription factor in neutrophil granulopoiesis (32).

It is also intriguing that all three factors in our study (miR-34a and miR-223 and their target Lef1) have been implicated in granulopoiesis (32). In this context, it has been suggested that subtle differences in transcription factor levels, including the ratio between PU.1 and C/EBPα in myelomonocytic progenitors, may regulate monocyte versus granulocyte cell-fate choice (41). It will be interesting to determine whether miRNAs participate in erasing Lef1 expression in the commitment toward macrophages to avoid inappropriate differentiation.

In any case, analysis of Lef1 regulation in transdifferentiation of B cells shows redundancy of elements in directing activity toward its repression. We have observed that C/EBPα associates with the Lef1 promoter, and the occurrence of changes in the histone modifications indicates transcription factor-mediated and epigenetic control of repression. On the other hand, miR34a and miR-223 appear to ensure the complete erasure of Lef1. Therefore, C/EBPα may mediate gene repression of lymphoid genes by at least these two mechanisms (Fig. 5G).

We can also speculate whether alterations in C/EBPα could lead to aberrant changes in miRNA control that ultimately would cause the aberrant expression of lymphoid markers. This possibility is supported by the observation of a direct association of C/EBPα with the transcription start sites of several of the most highly upregulated miRNAs. C/EBPα mutations in acute myeloid leukemia are associated with downregulation of miR-34a, resulting in E2F3 upregulation and cell proliferation (23). It is likely that loss of miR-34a or miR-223 in acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) patients with mutations in C/EBPα would also disrupt cell identity.

In summary, our study uncovered a mechanism by which C/EBPα-induces and maintains the silencing of the B cell program during transdifferentiation of pre-B cells into macrophages. We demonstrate that miR-34a and miR-223 are targets of C/EBPα and play a key role in the successful transdifferentiation of B cells into macrophages. This consists in the activation of a regulatory loop involving two miRNAs that are required to rapidly and effectively silence a B cell regulator, thus providing an explanation for the tight link between gene activation and gene silencing during transdifferentiation. Future studies should reveal whether this represents a general principle common to other types of cell fate transitions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

E.B. is supported by grant SAF2011-29635 from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (MINECO) and grant 2009SGR184 from AGAUR (Catalan government).

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 13 January 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambros V. 2001. microRNAs: tiny regulators with great potential. Cell 107:823–826. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00616-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kulessa H, Frampton J, Graf T. 1995. GATA-1 reprograms avian myelomonocytic cell lines into eosinophils, thromboblasts, and erythroblasts. Genes Dev. 9:1250–1262. 10.1101/gad.9.10.1250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nerlov C, Graf T. 1998. PU. 1 induces myeloid lineage commitment in multipotent hematopoietic progenitors. Genes Dev. 12:2403–2412. 10.1101/gad.12.15.2403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xie H, Ye M, Feng R, Graf T. 2004. Stepwise reprogramming of B cells into macrophages. Cell 117:663–676. 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00419-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ji H, Ehrlich LI, Seita J, Murakami P, Doi A, Lindau P, Lee H, Aryee MJ, Irizarry RA, Kim K, Rossi DJ, Inlay MA, Serwold T, Karsunky H, Ho L, Daley GQ, Weissman IL, Feinberg AP. 2010. Comprehensive methylome map of lineage commitment from haematopoietic progenitors. Nature 467:338-342. 10.1038/nature09367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bussmann LH, Schubert A, Vu Manh TP, De Andres L, Desbordes SC, Parra M, Zimmermann T, Rapino F, Rodriguez-Ubreva J, Ballestar E, Graf T. 2009. A robust and highly efficient immune cell reprogramming system. Cell Stem Cell 5:554–566. 10.1016/j.stem.2009.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heath V, Suh HC, Holman M, Renn K, Gooya JM, Parkin S, Klarmann KD, Ortiz M, Johnson P, Keller J. 2004. C/EBPalpha deficiency results in hyperproliferation of hematopoietic progenitor cells and disrupts macrophage development in vitro and in vivo. Blood 104:1639–1647. 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang DE, Zhang P, Wang ND, Hetherington CJ, Darlington GJ, Tenen DG. 1997. Absence of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor signaling and neutrophil development in CCAAT enhancer binding protein alpha-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:569–574. 10.1073/pnas.94.2.569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Tullio A, Vu Manh TP, Schubert A, Mansson R, Graf T. 2011. CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha (C/EBP(alpha))-induced transdifferentiation of pre-B cells into macrophages involves no overt retrodifferentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:17016–17021. 10.1073/pnas.1112169108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nutt SL, Morrison AM, Dorfler P, Rolink A, Busslinger M. 1998. Identification of BSAP (Pax-5) target genes in early B-cell development by loss- and gain-of-function experiments. EMBO J. 17:2319–2333. 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reya T, O'Riordan M, Okamura R, Devaney E, Willert K, Nusse R, Grosschedl R. 2000. Wnt signaling regulates B lymphocyte proliferation through a LEF-1 dependent mechanism. Immunity 13:15–24. 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)00004-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skokowa J, Welte K. 2009. Dysregulation of myeloid-specific transcription factors in congenital neutropenia. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1176:94–100. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04963.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Travis A, Amsterdam A, Belanger C, Grosschedl R. 1991. LEF-1, a gene encoding a lymphoid-specific protein with an HMG domain, regulates T-cell receptor alpha enhancer function [corrected]. Genes Dev. 5:880–894. 10.1101/gad.5.5.880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodríguez-Ubreva J, Ciudad L, Gómez-Cabrero D, Parra M, Bussmann LH, di Tullio A, Kallin EM, Tegnér J, Graf T, Ballestar E. 2012. Pre-B cell to macrophage transdifferentiation without significant promoter DNA methylation changes. Nucleic Acids Res. 40:1954–1968. 10.1093/nar/gkr1015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kallin EM, Rodriguez-Ubreva J, Christensen J, Cimmino L, Aifantis I, Helin K, Ballestar E, Graf T. 2012. Tet2 facilitates the derepression of myeloid target genes during CEBPalpha-induced transdifferentiation of pre-B cells. Mol. Cell 48:266–276. 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alessandrini A, Pierce JH, Baltimore D, Desiderio SV. 1987. Continuing rearrangement of immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor genes in a Ha-ras-transformed lymphoid progenitor cell line. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 84:1799–1803. 10.1073/pnas.84.7.1799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raschke WC, Baird S, Ralph P, Nakoinz I. 1978. Functional macrophage cell lines transformed by Abelson leukemia virus. Cell 15:261–267. 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90101-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larionov A, Krause A, Miller W. 2005. A standard curve based method for relative real time PCR data processing. BMC Bioinformatics 6:62. 10.1186/1471-2105-6-62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicol JW, Helt GA, Blanchard SG, Jr, Raja A, Loraine AE. 2009. The Integrated Genome Browser: free software for distribution and exploration of genome-scale datasets. Bioinformatics 25:2730–2731. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pospisil V, Vargova K, Kokavec J, Rybarova J, Savvulidi F, Jonasova A, Necas E, Zavadil J, Laslo P, Stopka T. 2011. Epigenetic silencing of the oncogenic miR-17-92 cluster during PU. 1-directed macrophage differentiation. EMBO J. 30:4450–4464. 10.1038/emboj.2011.317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fazi F, Rosa A, Fatica A, Gelmetti V, De Marchis ML, Nervi C, Bozzoni I. 2005. A minicircuitry comprised of microRNA-223 and transcription factors NFI-A and C/EBPalpha regulates human granulopoiesis. Cell 123:819–831. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fukao T, Fukuda Y, Kiga K, Sharif J, Hino K, Enomoto Y, Kawamura A, Nakamura K, Takeuchi T, Tanabe M. 2007. An evolutionarily conserved mechanism for microRNA-223 expression revealed by microRNA gene profiling. Cell 129:617–631. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pulikkan JA, Peramangalam PS, Dengler V, Ho PA, Preudhomme C, Meshinchi S, Christopeit M, Nibourel O, Muller-Tidow C, Bohlander SK, Tenen DG, Behre G. 2010. C/EBPalpha regulated microRNA-34a targets E2F3 during granulopoiesis and is down-regulated in AML with CEBPA mutations. Blood 116:5638–5649. 10.1182/blood-2010-04-281600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rao DS, O'Connell RM, Chaudhuri AA, Garcia-Flores Y, Geiger TL, Baltimore D. 2010. MicroRNA-34a perturbs B lymphocyte development by repressing the forkhead box transcription factor Foxp1. Immunity 33:48–59. 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.06.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Velu CS, Baktula AM, Grimes HL. 2009. Gfi1 regulates miR-21 and miR-196b to control myelopoiesis. Blood 113:4720–4728. 10.1182/blood-2008-11-190215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choong ML, Yang HH, McNiece I. 2007. MicroRNA expression profiling during human cord blood-derived CD34 cell erythropoiesis. Exp. Hematol. 35:551–564. 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song SJ, Ito K, Ala U, Kats L, Webster K, Sun SM, Jongen-Lavrencic M, Manova-Todorova K, Teruya-Feldstein J, Avigan DE, Delwel R, Pandolfi PP. 2013. The oncogenic microRNA miR-22 targets the TET2 tumor suppressor to promote hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and transformation. Cell Stem Cell 13:87–101. 10.1016/j.stem.2013.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang GH, Wang F, Yu J, Wang XS, Yuan JY, Zhang JW. 2009. MicroRNAs are involved in erythroid differentiation control. J. Cell. Biochem. 107:548–556. 10.1002/jcb.22156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dweep H, Sticht C, Pandey P, Gretz N. 2011. miRWalk–database: prediction of possible miRNA binding sites by “walking” the genes of three genomes. J. Biomed. Inform. 44:839–847. 10.1016/j.jbi.2011.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. 2005. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell 120:15–20. 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X. 2008. miRDB: a microRNA target prediction and functional annotation database with a wiki interface. RNA 14:1012–1017. 10.1261/rna.965408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skokowa J, Cario G, Uenalan M, Schambach A, Germeshausen M, Battmer K, Zeidler C, Lehmann U, Eder M, Baum C, Grosschedl R, Stanulla M, Scherr M, Welte K. 2006. LEF-1 is crucial for neutrophil granulocytopoiesis and its expression is severely reduced in congenital neutropenia. Nat. Med. 12:1191–1197. 10.1038/nm1474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skokowa J, Klimiankou M, Klimenkova O, Lan D, Gupta K, Hussein K, Carrizosa E, Kusnetsova I, Li Z, Sustmann C, Ganser A, Zeidler C, Kreipe HH, Burkhardt J, Grosschedl R, Welte K. 2012. Interactions among HCLS1, HAX1 and LEF-1 proteins are essential for G-CSF-triggered granulopoiesis. Nat. Med. 18:1550–1559. 10.1038/nm.2958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zardo G, Ciolfi A, Vian L, Starnes LM, Billi M, Racanicchi S, Maresca C, Fazi F, Travaglini L, Noguera N, Mancini M, Nanni M, Cimino G, Lo-Coco F, Grignani F, Nervi C. 2012. Polycombs and microRNA-223 regulate human granulopoiesis by transcriptional control of target gene expression. Blood 119:4034–4046. 10.1182/blood-2011-08-371344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu TX, Lim EJ, Besse JA, Itskovich S, Plassard AJ, Fulkerson PC, Aronow BJ, Rothenberg ME. 2013. MiR-223 deficiency increases eosinophil progenitor proliferation. J. Immunol. 190:1576–1582. 10.4049/jimmunol.1202897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhuang G, Meng C, Guo X, Cheruku PS, Shi L, Xu H, Li H, Wang G, Evans AR, Safe S, Wu C, Zhou B. 2012. A novel regulator of macrophage activation: miR-223 in obesity-associated adipose tissue inflammation. Circulation 125:2892–2903. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.087817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Navarro F, Gutman D, Meire E, Caceres M, Rigoutsos I, Bentwich Z, Lieberman J. 2009. miR-34a contributes to megakaryocytic differentiation of K562 cells independently of p53. Blood 114:2181–2192. 10.1182/blood-2009-02-205062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kee BL, Murre C. 2001. Transcription factor regulation of B lineage commitment. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 13:180–185. 10.1016/S0952-7915(00)00202-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gutierrez A, Jr, Tschumper RC, Wu X, Shanafelt TD, Eckel-Passow J, Huddleston PM, III, Slager SL, Kay NE, Jelinek DF. 2010. LEF-1 is a prosurvival factor in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and is expressed in the preleukemic state of monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis. Blood 116:2975–2983. 10.1182/blood-2010-02-269878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu S, Zhou X, Steinke FC, Liu C, Chen SC, Zagorodna O, Jing X, Yokota Y, Meyerholz DK, Mullighan CG, Knudson CM, Zhao DM, Xue HH. 2012. The TCF-1 and LEF-1 transcription factors have cooperative and opposing roles in T cell development and malignancy. Immunity 37:813–826. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dahl R, Walsh JC, Lancki D, Laslo P, Iyer SR, Singh H, Simon MC. 2003. Regulation of macrophage and neutrophil cell fates by the PU. 1:C/EBPalpha ratio and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Nat. Immunol. 4:1029–1036. 10.1038/ni973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]