Increasing numbers of women are entering medicine. In 1959, women accounted for 6% of medical school graduates, compared with 44% in 1989.1 The most recent data from the Canadian Resident Matching Service (CaRMS)2 demonstrate that women have gained equity in numbers in Canadian medical schools. In 2003, 49.6% of CaRMS applicants were women. This year, the percentage was 50.1%. The most recent Canadian medical school classes have a range of 43%–74% women (mean 58%), compared with a range of 26%–57% men (mean 42%). The gender gap in medical schools no longer exists.

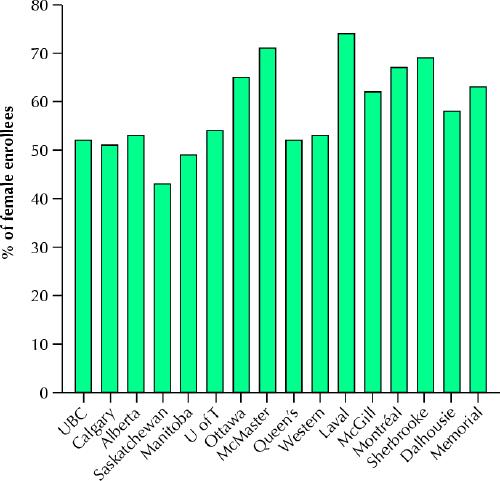

Interestingly, it appears that geography may play a role. Enrolment of women in Western and Prairie medical schools falls below the national average, while in Ontario and Atlantic Canada it is above average. Quebec has the highest enrolment of women, at 68%. Université de Laval has the greatest proportion of women in the entering class (74%) of any Canadian medical school, although McMaster University is close behind (71%). The University of Saskatchewan has the smallest proportion (43%) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Percentage of women who enrolled in Canadian medical schools in 2003.

Although present cohorts of female medical students may possess characteristics different from those of their predecessors, previous studies suggest that women and men hold somewhat different professional and personal values. These values play a role in decisions about where they will practise and the type of practice they want. Compared with men, women work fewer hours per week, see fewer patients (and provide fewer services), are likely to leave the medical profession sooner, and are less inclined to join professional organizations. They are more likely to enter primary care specialties than men and less likely to pursue surgical careers. Also, between 20% and 50% of female primary care physicians practise part time.3 Female students and physicians in training are also taking time off to have children, lengthening the educational period and increasing demand for longer maternity leaves and greater flexibility in training.

Why are fewer men and more women entering medical school in both Canada and the United States? It seems that altered behaviours of both sexes are contributing to this trend. Studies in the US suggest that over the past 25 years there has been a progressive decline in the proportion of men seeking postsecondary education at all levels and a decline in the percentage of men who seek education in either the medical profession or at the doctoral level.4 Conversely, early education promoting the achievements of girls has led to an increase in the number of women in university programs and interest among these female university students in pursuing medical education.4 Assuming that the US evidence is generalizable to the Canadian educational environment, the trend of increasing numbers of female medical school matriculants is unlikely to change in the near future.

The mature physician workforce

The average age of physicians in Canada in 2002 was 48 years of age.5 As of 2003, 57% of physicians under the age of 45, 74% of physicians between the ages of 45 and 65 and 90% over age 65 were men. This implies that, within the next 10 to 20 years, a great number of male physicians will be leaving their practices and, in their wake, a cohort of female physicians will begin to predominate.

A gale force?

The trend toward more female physicians has a number of implications, including:

· a greater decline in full-time equivalents of physician services than expected, especially in medical careers where greater numbers of women are entering (e.g., family practice and obstetrics and gynecology), leading to decreased aggregate productivity,6and

· a possible sustained decline in applicants for surgical training positions.6

We can expect that the need for doctors will grow as a result of the aging of the population and the development of new technologies that will increase the number and intensity of medical services that are sought. This need will likely be amplified as the sex distribution of practising physicians shifts toward women. To minimize the future effects on the Canadian physician workforce of this demographic shift, it is imperative that workforce planners and policy-makers recognize these trends.

Planners and policy-makers wield the power to introduce proactive measures to address properly the decline in applications to certain specialties and to maximize the contribution of female physicians to the workforce. Additional initiatives could include improved access to surgical and specialty fields by means of training and practice settings that provide a more manageable balance between work and family life. It is time for health care workforce planners, policy-makers and administrators at all levels to take heed of these impending macro forces and prevent them from becoming health care gales.

Kirsteen R. Burton Department of Public Health Sciences University of Toronto Toronto, Ont. Ian K. Wong Faculty of Medicine University of British Columbia Vancouver, BC

References

- 1.Williams A, Pierre K, Vayda E. Women in medicine: toward a conceptual understanding of the potential for change. J Am Med Womens Assoc 1993; 48(4):115-21. [PubMed]

- 2.Canadian Resident Matching Service. CaRMS Statistics. Available: www.carms.ca/stats/stats_index.htm (accessed 2004 Mar 25).

- 3.Williams A, Domnick-Pierre K, Vayda E, Stevenson H, Burke M. Women in medicine: practice patterns and attitudes. CMAJ 1990;143 (3): 194-201. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Cooper R. Impact of trends in primary, secondary, and postsecondary education on applications to medical school. I: gender considerations. Acad Med 2003;78(9):855-63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.McMurray J, Cohen M, Angus G, Harding J, Gavel P, Horvath J, et al. Women in medicine: a four-nation comparison. J Am Med Womens Assoc 2002; 57(4):185-90. [PubMed]

- 6.Average age of physicians by physician type and province/territory, Canada, 1998 and 2002. Available: http://secure.cihi.ca/cihiweb/en/AR14_2002_tab2_e (accessed 2004 Mar 25).