ABSTRACT

To investigate the potential benefits which may arise from pseudotyping the HIV-1 lentiviral vector with its homologous gp41 envelope glycoprotein (GP) cytoplasmic tail (CT), we created chimeric RVG/HIV-1gp41 GPs composed of the extracellular and transmembrane sequences of RVG and either the full-length gp41 CT or C terminus gp41 truncations sequentially removing existing conserved motifs. Lentiviruses (LVs) pseudotyped with the chimeric GPs were evaluated in terms of particle release (physical titer), biological titers, infectivity, and in vivo central nervous system (CNS) transduction. We report here that LVs carrying shorter CTs expressed higher levels of envelope GP and showed a higher average infectivity than those bearing full-length GPs. Interestingly, complete removal of GP CT led to vectors with the highest transduction efficiency. Removal of all C-terminal gp41 CT conserved motifs, leaving just 17 amino acids (aa), appeared to preserve infectivity and resulted in a significantly increased physical titer. Furthermore, incorporation of these 17 aa in the RVG CT notably enhanced the physical titer. In vivo stereotaxic delivery of LV vectors exhibiting the best in vitro titers into rodent striatum facilitated efficient transduction of the CNS at the site of injection. A particular observation was the improved retrograde transduction of neurons in connected distal sites that resulted from the chimeric envelope R5 which included the “Kennedy” sequence (Ken) and lentivirus lytic peptide 2 (LLP2) conserved motifs in the CT, and although it did not exhibit a comparable high titer upon pseudotyping, it led to a significant increase in distal retrograde transduction of neurons.

IMPORTANCE In this study, we have produced novel chimeric envelopes bearing the extracellular domain of rabies fused to the cytoplasmic tail (CT) of gp41 and pseudotyped lentiviral vectors with them. Here we report novel effects on the transduction efficiency and physical titer of these vectors, depending on CT length and context. We also managed to achieve increased neuronal transduction in vivo in the rodent CNS, thus demonstrating that the efficiency of these vectors can be enhanced following merely CT manipulation. We believe that this paper is a novel contribution to the field and opens the way for further attempts to surface engineer lentiviral vectors and make them more amenable for applications in human disease.

INTRODUCTION

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) particles produced by cells superinfected with other viruses, such as herpes simplex virus (HSV), rabies virus (RV), Moloney murine leukemia Virus (MMLV), and vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), acquire an altered cell tropism due to the presence of heterologous envelope-incorporated surface glycoproteins (GPs) (1–5). This process, known as pseudotyping and reviewed by Cronin et al. (6), has been extensively employed to modify, improve, and refine the cell and tissue tropism, together with the transduction efficiency, of retrovirus-based replication-defective gene therapy vectors and both primate and nonprimate lentiviruses (LVs). The high transduction efficiency and wide cell tropism of VSV GP (VSVG)-pseudotyped LV vectors have made this the standard for pseudotype comparison. VSVG-pseudotyped LV vectors are stable and can sustain purification and concentration protocols needed for clinical use (7). However, their broad cell tropism raises considerations for their safe use to target gene delivery to specific areas; moreover, they lack the ability to reach inaccessible sites such as the central nervous system (CNS) without invasive means of delivery.

Pseudotyping of LV vectors with the envelope GP of rabies virus (RVG) confers both neurotropism and the ability to mediate retrograde trafficking of vector particles along neuronal axons (8–14). GP of Lyssavirus (RV and rabies-related virus) origin is the most promising for the targeting of neuronal cells in vitro and in vivo (13) and thus presents a considerable possibility of targeting gene therapy for neurodegenerative diseases specifically to neuronal cells. Additionally, it opens up the amenable route of noninvasive administration of the vector by targeting peripheral sites of neuromuscular synapses to access CNS neurons affected by such diseases as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and spinal muscular atrophy. Despite the additional advantages of the LV vectors in terms of safety, ease of handling, and low toxicity to the transduced cells, their practical use has been limited due to low efficiency of retrograde transduction. HIV vectors pseudotyped with either the RV racSADB19 strain or the related Mokola virus GPs showed almost 5-fold-lower transduction efficiency than an equivalent number of VSVG-pseudotyped vector particles on the same cell types (14). Different strains of RV and related GPs appear to pseudotype lentivirus vectors at different efficiencies. The RV ERA (Evelyn-Rokitnicki-Abelseth) and CVS (challenge virus standard; B2c) strains have been shown to efficiently pseudotype LV vectors derived from equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV), although at a lower efficiency than VSVG (8, 10). To date, efficient pseudotyping of HIV-1-based vectors with RVG has best been achieved with the B2c substrain (11). Recently the introduction of fusion envelope GPs composed of parts of RVG and VSVG was reported to improve the pseudotyping and infectivity of these vectors at least in vitro (15–17). One caveat for this vector system is that both pseudotyping and transduction efficiency are still not as high as those achieved by VSVG-pseudotyped vectors.

One way to overcome such limitations is to increase the efficiency of incorporation of the heterologous GPs onto the vector particles. Within this framework, studies with wild-type (WT) measles virus (MV) were able to achieve pseudotyping of LVs with improved titers and selectivity (18). Most notably, variation in cytoplasmic tail (CT) length was proved to play a major role in enhancing pseudotyping efficiency and virological titers. An elevated transduction efficiency was shown with the subsequent deletion of CT residues. In addition, these authors determined an optimal truncation point which allowed them to maximize viral production titers. After this peak, further truncations reduced the viral titer dramatically (19).

HIV-1 Env GPs are synthesized as a polyprotein precursor (gp160) that is cleaved by cellular proteases to the mature surface glycoprotein gp120 and the transmembrane glycoprotein gp41 (20). The long HIV-1gp41 CT in HIV-1, consisting of several distinct motifs such as the “Kennedy” (Ken) sequence and lentivirus lytic polypeptide 1 (LLP1), LLP2, and LLP3, appears to play a critical role in efficient envelope GP incorporation into virion particles (21, 22). Truncations in CT result in reduced incorporation efficiency (23–26). It is evident from biochemical studies that long gp41 CT assists in sorting of envelope GPs into raft-like microdomains which mediate specific interaction with matrix and thereby promote envelope GP incorporation into virions (22, 25, 27, 28). In recent studies, it has been reported that the LLP1 and LLP2 motifs constitute a critical element in regulating the fusogenicity of viral envelope through the interaction between the transiently exposed LLP2 region and the gp41 viral core. Additionally, mutation in the LLP2 motif results in a 90% reduction in fusogenicity in comparison to that of the WT viral envelope (29).

In the present study, we sought to improve the transduction efficiency of LV vectors pseudotyped with the following envelope glycoproteins: (i) an RVG/Tailless maintaining only the first two CT Arg amino acids for stability purposes and (ii) five chimeric RVG/HIV-1gp41 proteins incorporating various CT truncations (R4 to R8) sequentially removing conserved motifs. These were compared to LVs pseudotyped with the existing RVG B2c strain (WT), the RVG/VSVG(C) hybrid (17), and VSVG. We also evaluated in vivo the gene transfer efficiencies of the pseudotyped LV vectors that best transduced neuronal cell lines in vitro by comparing them with the previously tested RVG/VSVG(C) envelope (17).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

HEK293T cells (HEK 293T/17, ATCC CRL-11268) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (D6546; Sigma, Gillingham, United Kingdom) supplemented with penicillin-streptomycin (P4333; Sigma), 4 mM l-glutamine (G7513; Sigma), and 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum. SH-SY5Y cells (94030304; ECACC, Salisbury, United Kingdom) were maintained in 1:1 Ham's F-12 medium (N4888; Sigma)–Eagle's minimal essential medium (M2279; Sigma) supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 1% nonessential amino acids, and 15% fetal bovine serum. Neuro2a cells (Vasso Episkopou, Imperial College London) were propagated in Glasgow's minimum essential medium (21710025; Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 1% nonessential amino acids, 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Sigma), 1% sodium pyruvate (S8636; Sigma), and 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum.

Cloning of RVG/Tailless expression plasmids.

The RVG/Tailless construct was generated by splicing by overhang extension PCR (SOE PCR). pMD-RV-CVS24 (B2c) served as the template and was restriction digested with BglII and BsiWI, producing two fragments, the vector (5,754 bp) and a fragment (242 bp) which includes part of the receptor binding domain (RBD), the transmembrane (TM) domain, and the whole CT. DNA fragments (428 bp) encoding RVG portions (including RBD, TM, and 2 amino acids [aa]of CT) were amplified by PCR using reverse primer 5′-CAGGCGTACGTCATCTTCTGCACCATGTCATTAGGG-3′ and forward primer 5′-GATGGAGGCTGATGCTCACTAC-3′. The PCR product (428 bp) was digested again with BglII and BsiWI to produce an insert (112 bp) without the CT portion. The insert was ligated with the vector to form the RVG/Tailless expression plasmid. Correct insertion of the construct was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Cloning of RVG/HIV-1gp41 constructs.

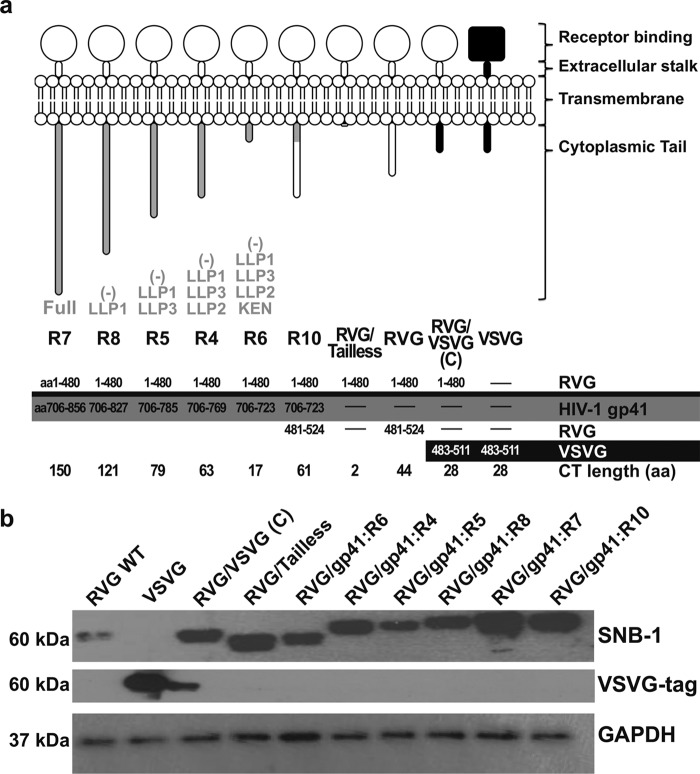

RVG/HIV-1gp41 and further truncations of gp41 CT chimeric constructs were generated by SOE PCR and Pfx proofreading Taq polymerase (Invitrogen). Five envelope expression plasmids (Fig. 1) were generated, encoding RVG/HIVgp41 chimeric proteins as follows: (i) construct RVG/HIV-1gp41 (CT, 150 aa), or R7, in which the cytoplasmic domain of RVG is replaced by the full cytoplasmic domain of HIV-1gp41; (ii) construct RVG/HIV-1gp41 (CT, 121 aa), or R8, in which the LLP1 motif is deleted from the HIV-1gp41 CT; (iii) construct RVG/HIV-1gp41 (CT, 79 aa), or R5, in which the LLP1 and -3 motifs are deleted; (iv) construct RVG/HIV-1gp41 (CT, 63 aa), or R4, in which all three LLP motifs are deleted; and (v) construct RVG/HIV-1gp41 (CT, 17 aa), or R6, in which the LLP1, -2, and -3 motifs as well as the Ken sequence are deleted.

FIG 1.

Construction of chimeric envelope GPs. (a) Schematic representation and comparison of the chimeric envelopes used in this study, showing how they relate to RVG, VSVG, and HIV-1gp41 sequences. The region of the respective protein used in each chimeric construct is shown in the table, and the amino acids flanking the fusion site are shown in detail for each envelope. (b) Expression of envelope plasmids in 293T cells. Envelope constructs were transfected in 293T cells, and equal amounts of protein extracts were blotted and probed with the SNB-1 antibody specific for RVG protein (∼60 kDa). The blot was subsequently stripped and reprobed with a VSVG tag antibody specific to VSVG protein (∼60 kDa) and also with a GAPDH antibody as loading control.

Construction of the chimeric constructs involved three separate PCRs, where the DNA fragments produced in the first two reactions were mixed for the third reaction.

A DNA fragment encoding the gp41 full-length CT was amplified with SOE_gp41_cyt (5′-ATGACATGGTGCAGAGTGAGACAGGGCTACAG-3′) and gp41_R7 (5′-GGCCGTACGCTATCACAGCAGGATTCTCTCCAGGC-3′) primers and the pHIVenvgp41-8 plasmid (6,568 bp; kindly provided by Z. Matsuda, University of Tokyo, Japan) as a template. The RbG_F1 (5′-CATGGGTCGCGATGCAAACA-3′) primer in conjunction with the SOE_RbG_TM/Cyt (5′-TCTCACTCTGTCGCACCATGTCATTAGGGAAAATATCAAC-3′) primer was used to amplify the RVG portion of the chimeric constructs, using the pMD-RVG-CVS24 (B2c) plasmid (Gene Bank accession no. AAB97691.1) as the template. PCR products of the initial reactions were mixed in a new reaction mixture to serve as the template and amplified with the gp41_R7 and RbG_F1 set of primers to generate the RVG/HIV-1gp41 (CT, 150 aa) or R7 construct.

Chimeric constructs ii to v were amplified with the RbG_F1 and gp41_R4 (5′-GAATTCCGTACGCTATCAGTGGTAGCTGAACAGG-3′), gp41_R5 (5′-GAATTCCGTACGCTATCACAGTAGCTCCACGATTC-3′), gp41_R6 (5′-GAATTCCGTACGCTATCAGGTGGGCAGGTGGGTC-3′), gp41_R7 (5′-GGCCGTACGCTATCACAGCAGGATTCTCTCCAGGC-3′), gp41_R8 (5′-GGCCGTACGCTATCATCTGTCGGTGCCCTCGGCCACG-3′) primers, respectively, in different reaction mixtures, with the R7 construct as the template.

To further explore the functional role of the 17-aa sequence of HIV-1 gp41 R6 cytoplasmic tail on LV production, a new construct (R10) was introduced to the study. To generate R10, we used the SOE PCR protocol, where the full-length RVG B2c CT (44 aa) was added 5′ from the HIV-1gp41 (17aa) truncated CT (construct R6). DNA fragments including R6 and RVG CT portions were amplified initially with RbG_F1 and SOE_R(R6+B2c):(5′-ATTGGCTCTTCTGGTGGGCAGGTGGGTC-3′) and R6 as the template. A parallel reaction took place with SOE_F (R6+B2c): (5′-CACCTGCCCACCAGAAGAGCCAATCGACC-3′) and B2C-WT_R10: (5′-GGCCGTACGCTATCACAGTCTGATCTCACCTCC-3′) set of primers and pMD-RVG-CVS24-B2c plasmid (Addgene plasmid 19713) as the template. The following final reaction included both PCR products resulted from the initial PCRs as the template and RbG_F1 together with B2C-WT_R10 as primers to generate the R10 chimeric construct.

All chimeric products were digested with restriction enzymes, and the BspEI-BsiWI restriction fragment replaced the corresponding fragment of the pMD-RVG-CVS24 (B2c) plasmid to generate each chimeric GP. Correct insertion and orientation in all produced constructs were confirmed by restriction enzyme digests and DNA sequencing.

Production and purification of LV vectors.

Replication-deficient HIV-1 LV vectors were produced using a modified calcium phosphate transient-transfection protocol (obtained from the John Olson lab, University of North Carolina) based on the standard four-plasmid transfection of HEK293T cells. Briefly, 1.4 × 107 to 1.6 × 107 HEK293T cells were seeded onto 15-cm2 tissue culture dishes. The next day, the cells were transfected with 15 μg vector plasmid (pRRLsincppt-CMV-eGFP), 15 μg plasmid expressing the HIV-1 gag/pol genes (pMD2-LgpRRE), 3 μg plasmid expressing HIV-1 Rev (pRSV-Rev), and 5.1 μg plasmid expressing the appropriate envelope GP. After 16 h, the medium was replaced with 10 mM sodium butyrate. At 36 h after sodium butyrate induction, vector-containing medium was harvested and filtered through a 0.45-μm filter. For the small-scale analytical preparation used for GP incorporation studies, vectors were purified and concentrated by ultracentrifugation (SW-32 Ti rotor [Beckman, High Wycombe, United Kingdom]; 82,000 × g, 2 h) of medium-containing vector from a single transfected 15-cm2 dish through a sucrose cushion (20% [wt/vol] sucrose, 10 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4). Vector pellets (120-fold concentration) were resuspended in TSSM buffer (20 mM tromethamine, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mg ml−1 sucrose, and 10 mg ml−1 mannitol) overnight. For large-scale preparation, vector-containing media from 12 transfected 15-cm2 plates were pooled and centrifuged overnight (Beckman F500 rotor; 6,000 × g). The pellet was resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and repelleted by ultracentrifugation (Beckman SW-32 Ti rotor; 68,500 × g, 1.5 h) and resuspended for several hours in TSSM buffer. Vector preparations (2,000-fold concentration) were subsequently stored at −80°C.

Titration of LV vectors.

The biological titers of LV vectors carrying the enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) reporter gene were determined by flow cytometry. Briefly, HEK293T, SH-SY5Y, and Neuro2a cells were seeded in 12-well plates at 1.5 × 105 cells per well. At 16 to 24 h after seeding, the cells in a single well were quantified using a hemocytometer. Cells were transduced for 6 h with a serial dilution of the vector to be quantified in the presence of 8 μg ml−1 Polybrene. At 72 h postransduction, the percentage of eGFP-positive (eGFP+) cells was determined by flow cytometry. The number of physical LV particles present in a preparation was estimated using an HIV-1 p24 antigen enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (RETROtek; ZeptoMetrix, Franklin, MA, USA).

Analysis of GP expression and vector incorporation by Western blotting and densitometry.

Equal amounts of vector particles (determined by p24 ELISA) were mixed with SDS staining dye, lysed by heating at 100°C for 10 min, and run on 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Upon collection of the culture medium, pelleted producer cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (catalog no. 89900; Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) with a protease inhibitors cocktail (catalog no. 78440; Pierce) and DNase. Samples were centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were collected. The protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay kit (Pierce). Equal amounts (15 μg) of protein were separated, transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, United Kingdom), blocked using PBS–Tween 20 (0.1%, vol/vol) with 5% (wt/vol) milk powder, and probed with specific RVG antibodies (mouse monoclonal SNB1, provided by Tony Fooks, AHVLA, United Kingdom) (dilution, 1:500). Antibody-recognized proteins were detected using a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (A-8924; Sigma, United Kingdom) (dilution, 1:10,000) and ECL reagent (Pierce). To ensure that equal amounts of viral vector p24 protein were loaded, membranes were stripped with Restore Western stripping buffer (Pierce) and reprobed with an anti-HIV-1 Gag p55+p24+p17 antibody (Ab63917; Abcam, United Kingdom) (dilution, 1:2,000) detected with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (A-0545; Sigma, United Kingdom) (dilution, 1:10,000). To ensure that equal amounts of protein from packaging cell lysates were loaded, membranes were further stripped and reprobed with a mouse monoclonal horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (anti-GAPDH) antibody (Ab9482; Abcam, United Kingdom) (dilution, 1:5,000). Bands were quantified using ImageJ software (W. S. Rasband, National Institutes of Health, USA; http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/) on scanned images of exposed films as described at http://lukemiller.org/index.php/2010/11/analyzing-gels-and-western-blots-with-image-j//.

Analysis of transduction pattern in the rat CNS.

All animal procedures were approved by the local ethical committee and performed in accordance with the United Kingdom Animals Scientific Procedures Act (1986) and associated guidelines. All efforts were made to minimize the suffering and the number of animals used. The animals were housed under a 12-h light/dark cycle (light phase, 1900 to 0700 h) with food and water available ad libitum. Animals were supplied by Harlan (Blackthorn, United Kingdom). A total of 12 male Wistar rats, weighing 150 to 200 g at the start of the experiment, were used. Before surgery, all animals were deeply anesthetized by inhalation of a mixture of 3 liters oxygen and ∼3.5% isoflurane (Merial, Parramata, NSW, Australia) and then received systemic analgesia. They were placed in a stereotaxic frame (Taxic-6000; World Precision Instruments, Hitchin, United Kingdom) with the nose bar set at +3.3 mm. The anesthetic mixture was changed to 1 liter oxygen and ∼2.0% isoflurane for the remainder of the operation. The scalp was cut and retracted to expose the skull. Craniotomy was performed by drilling directly above the target region to expose the pial surface. A single injection was directed into the right striatum using the stereotaxic coordinates relative to the bregma: anteroposterior, 0.5 mm; mediolateral, 3.0 mm; dorsoventral, 5.0 mm. Animals received 4.0 μl of pseudotyped LV vectors with a biological titer of 6.2 ×108 transduction units (TU)/ml−1 [RVG/VSVG(C)], 7.4 ×108 TU/ml−1 (RVG/Tailless), 9.9 ×108 TU/ml−1 (RVG/gp41:R6), or 1.9 ×108 TU/ml−1 (RVG/gp41:R5) via a 32-gauge blunt needle using an infusion pump (Ultramicropump II and Micro4 controller; World Precision Instruments) at a flow rate of 0.2 μl/min over 20 min. The needle was then allowed to remain on site for an additional 5 min before slow retraction. At the completion of surgery, the skin was sutured. Brains were analyzed at 3 weeks postinjection. Rats were euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of 200 mg/kg of sodium pentobarbitone and transcardially perfused with ∼50 ml saline (0.9% [wt/vol] NaCl) plus heparin, immediately followed by ∼250 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) (Sigma) in PBS. Brains were removed and postfixed for 4 h in 4% PFA (4°C), followed by cryoprotection in 10% glycerol and 20% sucrose in PBS for at least 72 h. Brains were subsequently embedded and frozen in OCT (Surgipath FSC22; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Thirty-micrometer coronal sections from the olfactory bulb (OB) through the entire striatum, globus pallidus, and substantia nigra (SN) were cut using a cryostat (Leica Microsystems), mounted on poly-l-lysine-coated slides, and stored at −20°C.

Immunohistochemistry of brain sections.

Immunohistochemistry was performed on slide-mounted brain sections. Tissue was permeabilized and blocked for 1 h with PBS containing 10% donkey serum and 0.1% Triton X-100. Antibodies to eGFP (1:500) (ab290; Abcam), neuronal nuclei (NeuN) (1:100) (MAB377; Millipore, Watford, United Kingdom), glial fibrillary acidic protein GFAP) (1:400) (MAB360; Millipore), and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) (1:2,000) (MAB318; Millipore) were diluted in the same buffer and placed on sections for 48 h at 4°C. Sections were then blocked for 30 min prior to incubating for 3 h at room temperature with donkey anti-mouse, anti-goat, or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexafluor 488, 594, and/or 647 (1:500). Sections were coverslipped with ProLong antifade aqueous mounting medium (Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom) in the presence of DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (0.05 μg/ml; Sigma) to label nuclear DNA.

Imaging analysis.

Images from single fluorescence-labeled brain sections (olfactory bulb and thalamus) were taken under an epifluorescence microscope (Eclipse 80i; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a motorized stage for automated tiling of adjacent fields (Prior Scientific, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Olfactory bulb images were taken using 10× objective (numerical aperture [NA], 0.45), while thalamic images were taken using a 4× objective (NA, 0.2). Doubly and triply fluorescence-labeled sections (striatum and SN) were acquired under a confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica TCS SP5 II). Cell counts for calculations of transduction efficiencies and tropism in vivo were performed using the ImageJ computer-assisted image analysis program to analyze micrographs of four to six sections for each individual animal captured using a 40× objective (NA, 0.85) (striatum and substantia nigra) or a 10× objective (NA, 0.45) (olfactory bulb and thalamus) after immunostaining. Counts were confirmed by a second observer blind to the experimental conditions. Volumetric parameters were estimated by measuring the distance (in millimeters) from the bregma of the first and the last striatum sections showing immunoreactivity to eGFP antibody along the rostro-caudal axis and multiplying it by the largest measured width (medio-lateral axis) and height (dorso-ventral axis) of transduction in the given animal. The linear values obtained represented the vertices of an octahedron encasing the vector diffusion into the striatum.

Statistical analysis.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for statistical comparisons. All calculations were performed on data averaged per animal. Significance was set at a P value of <0.05. Whenever a significant difference was found, post hoc analysis was performed (Tukey's honestly significant difference), and the F test statistic value is given (F = variance of the group means/mean of the within group variances). Analyses were carried out using R (R Development Core Team, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; http://www.R-project.org). Data are expressed as mean + standard error of the mean (SEM) (n = 3 or n = 2).

RESULTS

Design and construction of chimeric RVG/HIV-1gp41 and RVG/Tailless GP expression plasmids.

The HIV-1 envelope GP (Env) transmembrane (TM) subunit gp41 operates in conjunction with the surface gp120 subunit of the HIV-1 Env protein complex and plays an essential role during viral infection by mediating membrane fusion. HIV-1gp41 CT is relatively long (∼150 aa) compared to other retroviral CTs and contains several predicted structural features, including the hydrophilic region known as the Ken sequence (aa 731 to 752) and the LLP1 to -3 sequences (aa 773 to 862). The latter consist of three highly conserved alpha-helical domains: LLP1 (aa 833 to 862), LLP2 (aa 773 to 793), and LLP3 (aa 785 to 807) (30). To identify regions of the gp41 CT that possibly confer enhanced transduction efficiency of HIV-1 LV vectors, we engineered pseudotyped LV vectors with chimeric RVG/HIV-1 envelope GPs. The chimeric GPs consisted of the external and TM domains of RVG and the cytoplasmic domain of HIV-1gp41 (Fig. 1a). Several truncations of the full-length clone of HIV-1gp41 were also produced and tested. The truncations were designed to progressively remove the reported conserved domains or motifs including the three amphipathic helical segments (LLPs) and Ken sequence.

All chimeric envelopes contain the tyrosine-based sorting signal YXXL (aa 712 to 715), which is thought to determine the exact site of viral release at the surface of the infected cells and promotes endocytosis (31). To further clarify whether CT is a necessary factor for pseudotyping and transduction efficiency, we also generated by SOE PCR an RVG/Tailless construct where we truncated almost the entire RVG CT region and preserved only the first 2 CT amino acids (R-R) for membrane stability purposes. All GP plasmids had the correct sequence as determined by sequencing, and appropriate expression was further confirmed by Western blot analysis following transfection in 293T cells (Fig. 1b).

Lentiviral vectors pseudotyped with chimeric RVG/HIV-1gp41 GPs possessing shorter gp41 CTs have high titers on HEK293T, SH-SY5Y, and Neuro2a cells.

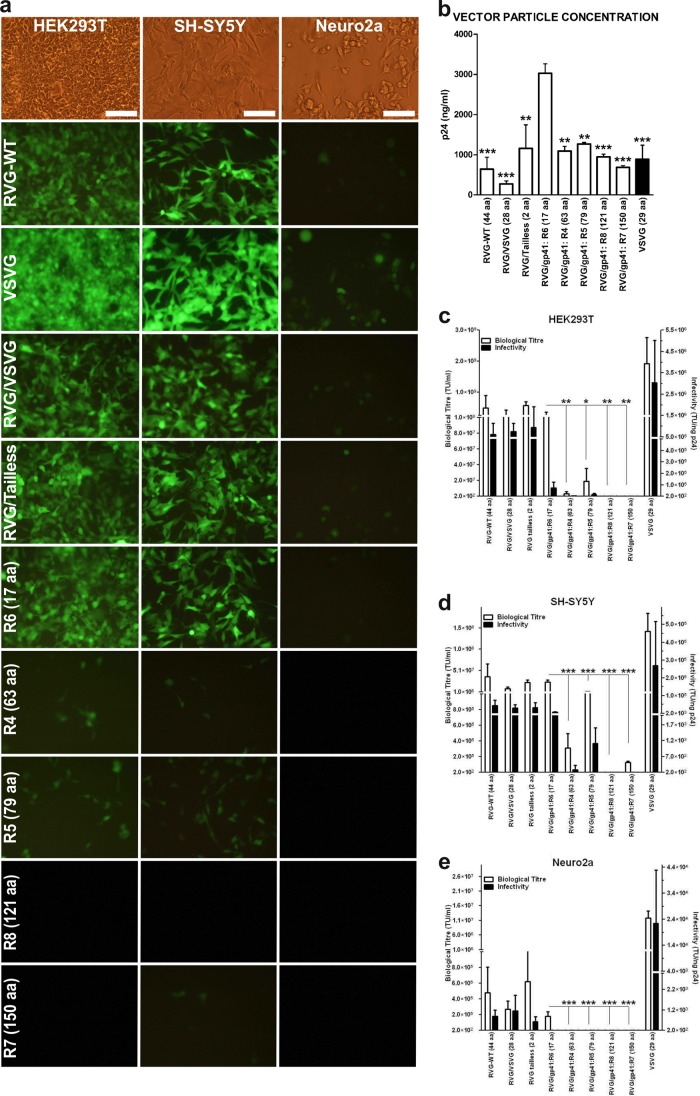

HIV-1 vectors carrying a green fluorescent protein (eGFP) transgene, pseudotyped with VSVG, RVG B2c (WT), RVG/VSVG(C), RVG/Tailless, and RVG/HIV-1gp41 glycoproteins (R4 to R8), were produced (triplicate small-scale preparations) by four-plasmid cotransfection in HEK293T cells using the calcium phosphate precipitation protocol. Supernatants were harvested, and vector particles were concentrated and purified by ultracentrifugation through a 20% sucrose cushion. The biological titer was determined by flow cytometry of eGFP-expressing transduced HEK293T, SH-SY5Y (thrice-cloned human neuroblastoma), and Neuro2a (mouse-derived neuroblastoma) cells. The results shown in Fig. 2 and Table 1 indicate that there is an inverse relationship between CT length and biological titer. Vectors bearing the TM glycoprotein with shorter CT truncations have increased transduction on HEK293T, SH-SY5Y, and Neuro2a cells, while those bearing full- or longer-length CT have low titers or no titer (Fig. 2a, c, d, and e). Titers obtained with the RVG/gp41 R6 construct were similar to RVG B2c, RVG/VSVG(C) and RVG/Tailless titers but were significantly higher than those achieved with all the remaining chimeric constructs, namely, RVG/gp41:R4, -R5, -R7, and -R8. This trend was repeatedly observed among all the cell lines examined [HEK293T, F(4,10) = 7.713 and P < 0.01; SH-SY5Y, F(4,10) = 64.379 and P < 0.001; Neuro2a, F(4,10) = 29.988 and P < 0.001 ANOVA summary)].

FIG 2.

Comparison of vector titers in the HEK293T, SH-SY5Y, and Neuro2a cell lines. (a) Representative fluorescence micrographs of HEK293T, SH-SY5Y, and Neuro2a cells transduced with different pseudotyped LV vectors carrying the eGFP reporter gene. Scale bars represent 100 μm. (b) The vector particle concentration (physical titer) was determined by p24 ELISA. Average nanograms of p24 protein per ml are plotted, and the values are expressed as mean + SEM (n = 3). R6 was found to have a significantly increased physical titer. Differences from R6 preparations (by ANOVA): **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (c, d, and e) Biological titers were determined by serial dilution using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) on all cell lines in triplicate with small-scale LV preparations purified on a sucrose cushion. The average TU per ml (biological titer) and average TU/ng of p24 protein (infectivity) are plotted, and the values are expressed as mean + SEM (n = 3). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Among the RVG/HIV-1gp41 GPs, R6 has significantly higher biological titers in all cell lines (by ANOVA).

TABLE 1.

Characterization of pseudotyped vector preparationsa

| Construct (aa) | Biological titer (concentrated particles) (TU ml−1) | Physical titer (p24 ng ml−1) | Vector infectivity (TU/ng p24) |

|---|---|---|---|

| VSVG (28) | 1.9 × 109 ± 5.9 × 108 | 8.8 × 102 ± 4.3 × 102 | 3.0 × 106 ± 1.4 × 106 |

| RVG WT (44) | 4.8 × 108 ± 2.9 × 108 | 6.3 × 102 ± 3.7 × 102 | 6.1 × 105 ± 3.7 × 105 |

| RVG/VSVG(C) (28) | 5.6 × 108 ± 1.3 × 108 | 2.7 × 102 ± 9.1 × 101 | 7.5 × 105 ± 2.8 × 105 |

| RVG/Tailless (2) | 2.3 × 108 ± 8.9 × 107 | 1.1 × 103 ± 7.2 × 102 | 9.4 × 105 ± 6.9 × 105 |

| RVG/gp41:R6 (17) | 2.1 × 108 ± 9.3 × 107 | 3.0 × 103 ± 2.9 × 102 | 7.6 × 104 ± 3.4 × 104 |

| RVG/gp41:R4 (63) | 1.2 × 106 ± 1.7 × 106 | 1.1 × 103 ± 1.3 × 102 | 2.8 × 103 ± 1.3 × 103 |

| RVG/gp41:R5 (79) | 1.9 × 107 ± 1.1 × 107 | 1.2 × 103 ± 4.6 × 101 | 1.4 × 104 ± 8.7 × 103 |

| RVG/gp41:R8 (121) | 0 | 9.5 × 102 ± 7.8 × 101 | 0 |

| RVG/gp41:R7 (150) | 0 | 6.8 × 102 ± 6.2 × 101 | 0 |

| RVG WTb | 5.5 × 108 ± 1.4 × 108 | 1.7 × 103 ± 0.3 × 103 | 3.04 × 105 ± 2.2 × 105 |

| RVG/gp41:R6b | 2.3 × 108 ± 3.7 × 108 | 3.4 × 103 ± 0.8 × 103 | 7.5 × 104 ± 1.8 × 104 |

| RVG/gp41:R10b | 5.9 × 108 ± 0.5 × 108 | 6.3 × 103 ± 1.4 × 103 | 9.8 × 104 ± 2.8 × 104 |

All values represent Mean ± SEM (n = 3).

Values are from a second experiment.

Additionally, when vectors pseudotyped with RVG glycoprotein that lacks a CT were applied to HEK293T, SH-SY5Y, and Neuro2a cells, the transduction levels achieved were the highest reported so far (Fig. 2a, c, d, and e). This is an indication that the CT region may not be required for lentiviral pseudotyping and that a long CT is possibly hindering this process.

Finally, the vector particle concentration of each preparation was determined by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) specific for the HIV-1 p24 capsid protein. The values obtained were used to calculate average vector infectivity (transduction units [TU] per ng p24). R6-pseudotyped vectors, lacking all the functional gp41 motifs, yielded a significantly increased vector particle concentration, about ∼ 3-fold higher than the rest of the envelopes (Fig. 2b), which increased further upon scaling up production for in vivo use (Table 2). As a result, the average infectivity of this vector was reduced (Fig. 2b, c, d, and e).

TABLE 2.

Characterization of vectors scaled up for in vivo experiments

| Vector | p24 (ng ml−1) | Biological titer on 293T cells (TU ml−1) | Vector infectivity (TU/ng p24) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RVG/VSVG(C) | 5.00 × 103 | 6.2 × 108 | 1.2 × 105 |

| RVG/Tailless | 7.0 × 103 | 7.4 × 108 | 1.0 × 105 |

| RVG/gp41:R6 | 8.1 × 104 | 9.9 × 108 | 1.2 × 104 |

| RVG/gp41:R5 | 6.9 × 104 | 1.9 × 108 | 2.8 × 103 |

Pseudotyping efficiency increases with CT truncation.

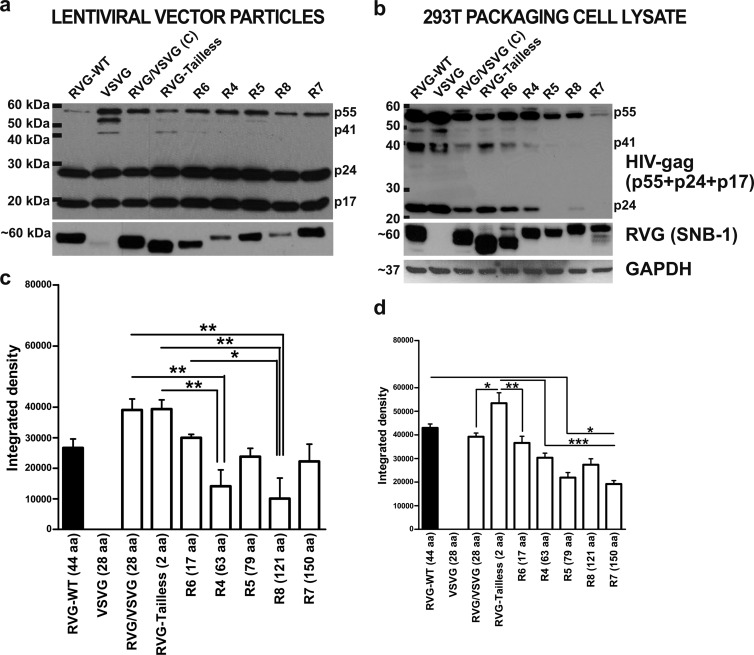

Western blot analysis of small-scale lentiviral preparations was performed to examine whether the increased transduction efficiency observed for RVG/Tailless was a result of increased incorporation of envelope protein (pseudotyping efficiency) on the lentiviral surface. Interestingly, RVG/Tailless and RVG/VSVG(C) chimeric pseudotyped vectors had higher RVG incorporation levels comparable to that of wild-type RVG B2c vectors, while chimeric envelopes with truncated gp41 CT showed reduced RVG incorporation levels. However, RVG incorporation levels reported for the R7 chimeric enveloped vector with full-length gp41 CT were almost equivalent to those for wild-type RVG B2c vectors. Moreover, incomplete processing of Gag precursor (p55) protein was observed mainly for VSVG-pseudotyped vector in viral lysates (Fig. 3a).

FIG 3.

Comparison of efficiency of RVG incorporation and expression in vector particles. (a and b) Western blots of purified pseudotyped lentiviral vector particles from small-scale preparations (a) and of 293T packaging cell lysates (b). Equal amounts of vector particle preparations and cell lysates were loaded into all wells, normalized to p24 ELISA or BCA protein assay values. Western blots were probed with the SNB-1 antibody specific for RVG protein (∼60 kDa). Membranes were subsequently stripped and reprobed with HIV-1 Gag antibody, which detects HIV-1 Gag proteins. p55 precursor and p41 intermediates were detected together with completely processed p24 capsid and p17 matrix proteins. The Western blot of cell lysates was finally stripped and reprobed with the GAPDH antibody (expected protein mass, ∼37 kDa) to assess protein loading. The size differences observed among the wild-type and chimeric proteins are due to the lengths of their cytoplasmic tails. (c and d) RVG incorporation and expression levels were quantified by densitometry from the Western blots. Integrated density values are plotted as mean + SEM (n = 3). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 (by ANOVA).

The same assay was performed with packaging cell lysates upon harvesting of the vector (Fig. 3b), confirming a pattern of envelope expression similar to that in Fig. 3a. A notable difference was the low levels of processed Gag and its derivatives detectable in chimeric envelopes with longer CTs. Densitometric analysis of the vector particle protein levels (Fig. 3c) and cell-associated RVG protein expression (Fig. 3d) from the Western blots supported that there was a statistically significant increase in the protein levels of the RVG/Tailless envelope compared to all the others.

A gp41 CT sequence that enhances lentiviral physical titer.

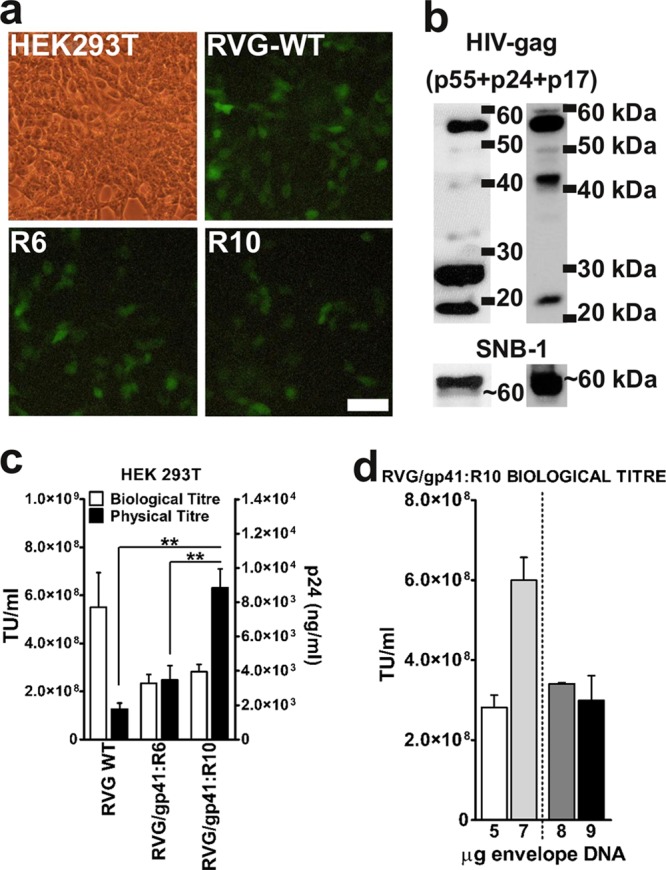

In order to further explore the functional role of the 17-aa sequence from the HIV-1 gp41:R6 cytoplasmic tail in LV production and to test whether this sequence could increase the physical titers of other pseudotypes, an additional chimeric GP, R10, was generated and studied: the HIV-1 gp41 (17-aa fragment in R6) was added 5′ of the full-length RVG B2c CT (44 aa). This modification did not affect the Gag processing or RVG pseudotyping efficiency of HIV vectors (Fig. 4b). R10-pseudotyped vectors had an approximately 5-fold-increased physical titer compared to wild-type RVG B2c-pseudotyped ones [F(2,6) = 19.979 and P < 0.01 by ANOVA) (Fig. 4c, black bars). The RVG/gp41:R10 vector physical titer was also higher than that of the R6-pseudotyped vectors (P < 0.01 by ANOVA) (Fig. 4c, black bars). The biological titer of R10-pseudotyped vectors was similar to that of the RVG/gp41:R6-pseudotyped ones and approximately 2-fold lower than that of vectors pseudotyped with RVG B2c (Fig. 4c, white bars). In order to test whether the envelope GP expression was the limiting factor affecting the packaging into functional particles, we generated a series of R10-pseudotyped vector preparations by sequentially increasing the envelope concentration until an optimal biological titer was reached. Opposite to what was observed for the RVG WT-pseudotyped vectors, which exhibited the highest biological titer when 5 μg of envelope plasmid was used (additional addition of envelope resulted in a drop in titer [data not shown]), the R10-pseudotyped vectors displayed a further increase in biological titer, with 7 μg of envelope plasmid being optimal (Fig. 4d). Any addition of envelope plasmid DNA beyond this concentration repressed the biological titer.

FIG 4.

Viral titers of RVG/gp41:R10 pseudotyped vectors. (a) Representative fluorescence micrographs of HEK293T transduced with different pseudotyped LV vectors carrying the eGFP reporter gene. The scale bar represents 50 μm. (b) Western blots of purified pseudotyped vector particles (left) and of producer cell lysates (right). HIV-1 Gag p55 precursor and p41 intermediates were detected by the HIV-1 Gag antibody along with completely processed p24 capsid and p17 matrix protein. Membranes were subsequently stripped and reprobed with the SNB-1 antibody specific for RVG protein (∼60 kDa). (c) The vector particle concentration (physical titer; ng p24 ml) (black bars) was determined by p24 ELISA, and biological activity (TU ml) (white bars) was determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) on HEK 293T cells for triplicate small-scale preparations purified by sucrose cushion protocol. Values are plotted as mean + SEM (n = 3). **, P < 0.01 (by ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test). (d) Biological titers of RVG/gp41:R10 pseudotyped lentiviral vector produced with various concentrations of envelope plasmid DNA. The 5-μg and 7-μg values represent the average for three independent small-scale preparations + SEM. The 8-μg and 9-μg values represent the average for two independent small-scale preparations + SEM.

Enhanced CNS retrograde transduction with RVG/gp41:R5 chimeric envelope.

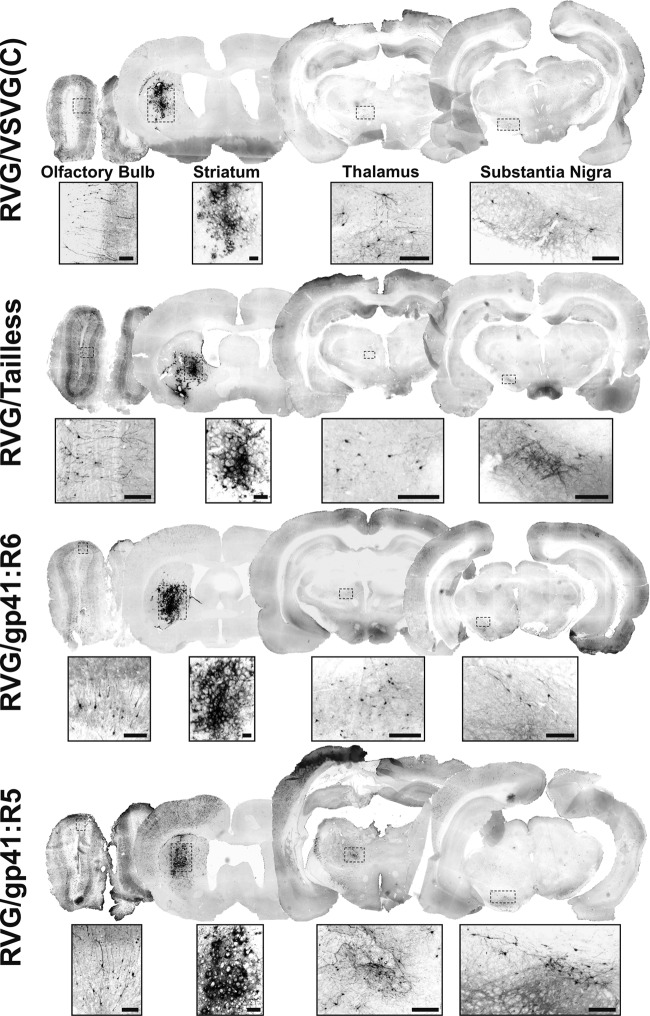

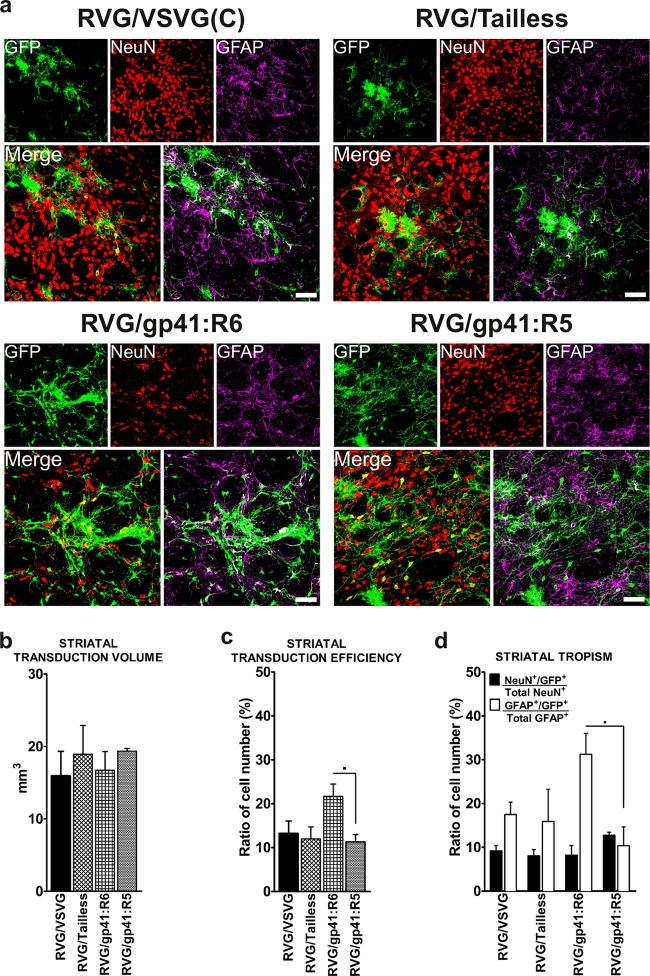

The transduction efficiency of eGFP-expressing HIV vectors pseudotyped with RVG/VSVG(C), RVG/Tailless, RVG/gp41:R6, or RVG/gp41:R5 was further assessed in the brains of rats (n = 12) following stereotaxic intrastriatal injections with 4 μl of each vector (no titer normalization was possible). While all of the tested pseudotypes exhibited transgene expression spreading beyond the striatum anteroposteriorly to regions distal to the injection site, immunohistochemical staining of sections to enhance the eGFP signal revealed differences in their patterns of transduction (Fig. 5). High-magnification images of striatal sections showed the presence of intense eGFP signal in cell somas and processes (Fig. 5, insets). The volume of transduction at the site of injection (Fig. 6b) did not significantly differ across all the pseudotypes. Triple staining of striatal sections with antibodies against eGFP, neuronal nuclei (NeuN), and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) revealed the distinctive brain tropism of the pseudotypes injected, with RVG/gp41:R6 showing the highest tropism for cells of glial morphology/profile (astrocytes, GFAP+) (Fig. 6a) and RVG/gp41:R5 displaying the best neuronal tropism (NeuN+) (Fig. 6a). Counts of total eGFP+ cells over summed NeuN+ and GFAP+ cells in the striatum revealed a slightly higher ratio of transduced cells for R6 than for the RVG/gp41:R5 pseudotype (21.6% ± 3.4% versus 11.3% ± 2.0%) [F(3,8) = 3.504 and P < 0.1 (ANOVA summary)] and other pseudotypes (Fig. 6c). The separate analysis of neuronal (eGFP/NeuN double positive/total NeuN+) and astro-glial (eGFP/GFAP double positive/total GFAP+) transduction efficiencies highlighted a slightly enhanced astro-glial tropism of RVG/gp41:R6 compared to RVG/gp41:R5 (31.2 ± 5.8% versus 10.3 ± 5.2%) [F(3,8) = 3.031 and P < 0.1 (ANOVA summary)] and other pseudotypes (Fig. 6d, white bars). Neuronal transduction was approximately the same among all pseudotypes analyzed, with RVG/gp41:R5 showing a better although not statistically significantly different neurotropism (Fig. 6d, black bars).

FIG 5.

Comparison of transduction efficiencies following intrastriatal vector delivery. Representative images of eGFP expression at the site of injection and distal sites (olfactory bulb, thalamus, and substantia nigra) after a single injection of 4 μl of each HIV-1 LV pseudotyped with RVG/VSVG(C) (2.49 × 106 TU), RVG/Tailless (3.09 × 106 TU), RVG/gp41:R6 (3.96 × 106 TU), or RVG/gp41:R5 (7.88 × 105 TU) in the striata of Wistar rats are shown. Brains were harvested at 3 weeks postinjection. Brain sections, 30 μm thick, were obtained and stained with anti-eGFP antibody to enhance the eGFP signal (Alexafluor 488 secondary antibody; images were converted to black and white and then inverted to show eGFP in black). High-magnification insets corresponding to marked regions (dashed boxes) of the panoramic section images indicate the transduction of cell bodies and fibers. Panoramic section images were captured by epifluorescence microscopy with a 4× objective. Olfactory bulb images and inserts were captured with a 10× objective. Scale bars represent 50 μm.

FIG 6.

Comparison of transduction characteristics following intrastriatal vector delivery. (a) Confocal analysis of eGFP expression in the striatum at the site of injection as shown in Fig. 5. Brain sections were stained using anti-eGFP antibody (Alexafluor 488 secondary antibody, shown in green) to enhance the GFP signal, antibody to NeuN (Alexafluor 594 secondary antibody, shown in red) to stain neuronal cells, and antibody to glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (Alexafluor 647 secondary antibody, shown in magenta) to stain astrocytes. Images were acquired using a 40× objective. Scale bars represent 50 μm. (b) Estimated volume of striatum transduced by each pseudotyped LVs. Data are plotted as mean mm3 + SEM (n = 2). (c) Efficiency of gene transfer of pseudotyped LVs. The ratio of eGFP+ to total NeuN+ and GFAP+ cell number is plotted (mean + SEM; n = 3). *, P < 0.1 (statistical trend to difference between the pseudotypes used) (by ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test). (d) Tropism of pseudotyped LVs in the striatum. The ratio of eGFP+/NeuN+ to total NeuN+ cell number and the ratio of eGFP+/GFAP+ to total GFAP+ cell number are plotted (mean + SEM; n = 3). *, P < 0.1 (statistical trend to difference between the pseudotypes) (by ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test).

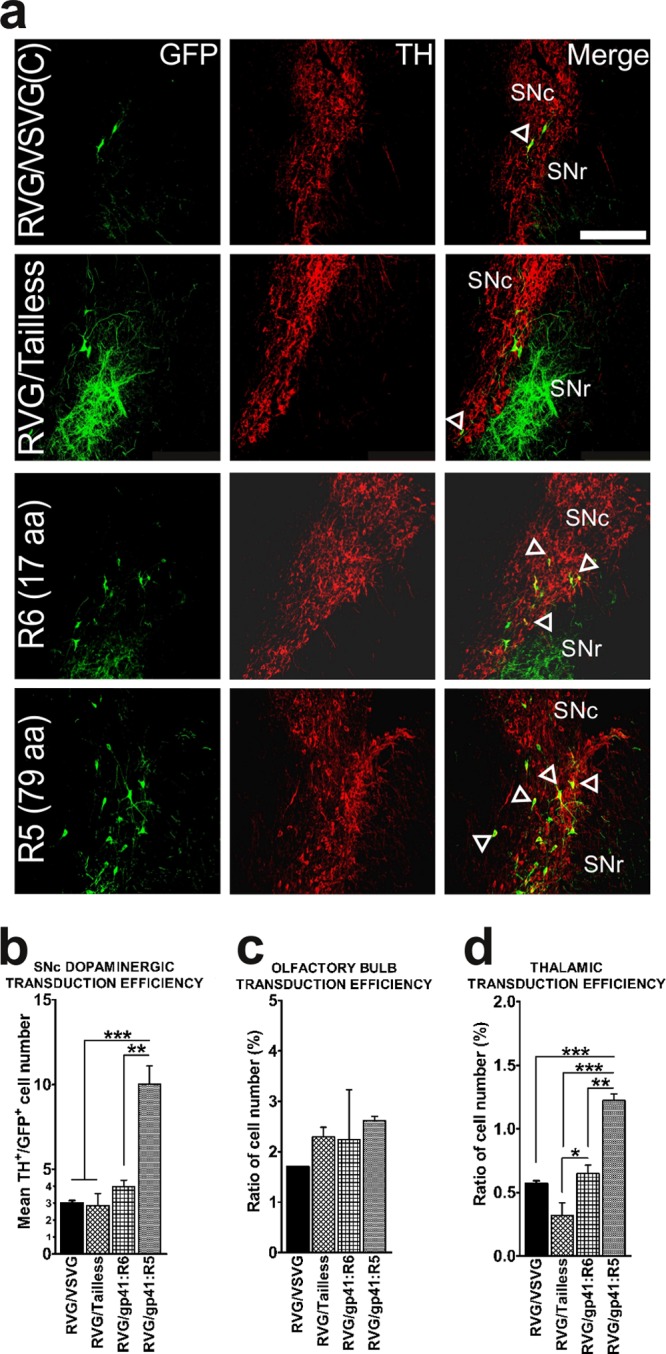

The RVG/VSVG(C)-pseudotyped vector showed its previously reported (16, 17) retrograde transport capability, but the other chimeric envelope-pseudotyped vectors also similarly transduced neuronal cells in distal areas (Fig. 5 and 7a). eGFP-positive neurons were observed in sites known to project to the striatum, including the olfactory bulb (OB), thalamus, and substantia nigra (SN), in brains injected with all pseudotypes. In some animals, staining of neuronal fibers was also observed in the globus pallidus (not shown) and SN pars reticulata (SNr) (Fig. 5 and 7a), most likely resulting from anterograde migration of eGFP into cell projections from its site of expression in the striatal cell body.

FIG 7.

Comparison of distal retrograde transduction following intrastriatal vector delivery. (a) Confocal analysis of eGFP expression of pseudotyped LVs in nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons. Substantia nigra-containing sections 30 μm thick were stained using anti-eGFP antibody to enhance the eGFP signal (Alexafluor 488 secondary antibody, shown in green) and antibody to tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) (Alexafluor 594 secondary antibody, shown in red) to stain dopaminergic neurons. Pictures were taken at a magnification of ×20. SNc, pars compacta; SNr, pars reticulata. The scale bar represents 250 μm. (b) Efficiency of retrograde transport of pseudotyped LVs in SNc. The mean number of double-positive eGFP+/TH+ cells per section is plotted (mean + SEM; n = 3). ***, P < 0.001 (statistically significant difference between the pseudotypes used) (by ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test). (c) Efficiency of gene transfer of pseudotyped LVs in the olfactory bulb. The ratio of eGFP+ to DAPI+ total cell number is plotted (mean + SEM; n = 3). (d) Efficiency of gene transfer of pseudotyped vectors in the thalamus. The ratio of eGFP+ to DAPI+ total cell number is plotted (mean + SEM; n = 3).

The retrograde transduction efficiency of these pseudotyped LVs was determined by immunohistochemistry on sections obtained from the olfactory bulb and thalamus, using antibody against eGFP (Fig. 5, insets), and by dual immunohistochemistry, using antibodies to eGFP and to tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), for the sections containing SN. Given that the striatum is receiving topographically defined dopaminergic inputs from the pars compacta of SN (SNc) while sending projections to the pars reticulata, we quantified the average number of eGFP/TH double-positive cells per section. In agreement with previously published results (17), we found the RVG/VSVG(C) pseudotype to be capable of transducing an average of 19 ± 1.87 dopaminergic (TH+) cells (3 ± 0.18 per SN section). The RVG/Tailless-pseudotyped vectors transduced an average of 19.3 ± 6.87 cells (2.8 ± 0.8 per section), the RVG/gp41:R6-pseudotyped vectors 26 ± 3.54 cells (4.7 ± 1.3 per section), and the RVG/gp41:R5-pseudotyped vectors 62.7 ± 7.76 cells (10.0 ± 1.3 per section). The difference between RVG/gp41:R5 and the other pseudotyped vectors was found to be statistically significant [F(3,8) = 21.172 and P < 0.001 (ANOVA summary)] (Fig. 7a and b). In other regions assessed, we confirmed again results obtained previously (17). In the OB, the RVG/VSVG(C) vectors transduced 1.7% ± 0.01% of DAPI+ cells, and the RVG/Tailless, RVG/gp41:R6, and RVG/gp41:R5 vectors transduced 2.30% ± 0.19%, 2.7% ± 0.49%, and 2.6% ± 0.08% of DAPI+ cells, respectively (Fig. 7c). In the thalamus we observed the same pattern as for the SNc: the RVG/gp41:R5 pseudotype was the most efficient of remaining pseudotypes [1.2% ± 0.06% of DAPI+ cells transduced, versus 0.60% ± 0.04% for RVG/VSVG(C) vectors, 0.3% ± 0.12% for RVG/Tailless vectors, and 0.6% ± 0.08% for RVG/gp41:R6 vectors]; the differences were all statistically significant, as was the difference between the RVG/gp41:R6 and RVG/Tailless vectors [F(3,8) = 33.855 and P < 0.001 (ANOVA summary)] (Fig. 7d).

DISCUSSION

HIV-1 and other LV vectors have been widely used for gene delivery, establishing them as valid tools for both basic research and clinical applications. These vectors are particularly attractive due to their ease of production, their cloning versatility, their low host immunoactivation, and their ability to efficiently alter their tropism through pseudotyping. Moreover, the capability to transduce low-proliferating or nonproliferating cell populations, such as neurons, makes them ideal for central nervous system (CNS) applications (11–14, 16). VSV and RV glycoproteins are the most commonly used for pseudotyping lentiviral vectors intended to transduce specifically the CNS, as they both confer intense neurotropism. The first type of envelope yields stable, high-titer pseudotyped LVs that possess a wide cell tropism but lack of specificity. The latter, despite the lower transduction efficiency compared to that of VSVG-pseudotyped LVs, confers upon them both neurotropism and, more importantly, the ability to retrograde traffic along neuronal axons, resulting in distal neuronal transduction (8).

To partially overcome the low efficiency of RVG-pseudotyped LVs, chimeric GPs bearing extracellular parts of RVG and the CT of VSVG were previously designed by us and others and tested both in vitro and in vivo (16, 17). These were shown to increase viral production yields as well as in vitro transduction; however, we did not observe any increase upon in vivo application (17). The work presented here is a further attempt to increase the efficiency of RVG-pseudotyped LVs by manipulating the envelope CT. We aimed at enhancing the infectivity of the pseudotyped LVs by replacing the CT of the RVG with heterologous topological motifs from the HIV-1 gp41 CT. Wild-type RVG B2c and HIV-1gp41 viral proteins embedded on the lipid bilayer of the viral envelopes exist as homotrimers that facilitate receptor binding and membrane fusion reactions (32, 33). In the current study, we have generated a series of chimeric homotrimer envelope GPs in which the extracellular and TM parts of wild-type RVG B2c were combined with the full or truncated domains of the HIV-1 gp41 CT. Transduction efficiency was assessed in vitro on a panel of different cell lines. Since we aimed at improving neuronal transduction, some of the cell lines used in vitro had a neuronal phenotype, and transduction of the highest-titer vectors was further investigated in the rodent brain.

Physiological functions of the HIV-1 gp41 CT are modulated by several already-recognized and extensively studied motifs and domains. These consist of the three amphipathic alpha-helical segments, LLP1, LLP2, and LLP3, located in the central and C-terminal regions of gp41 CT, the “Kennedy” sequence upstream of LLP2, the consensus YXXL sequence present in the proximal N-terminal region, the C-terminal dileucine motif, and two palmitylated Cys (29, 31, 34). These motifs are implicated in many and sometimes diverse aspects of the virus life cycle; however, successful fusion of the viral envelope with the host's plasma membrane appears to be their most profound role (20). Many studies have proposed a direct or indirect interaction between the gp41 CT and the unprocessed Gag (35, 36) or the matrix domain (p17) of Gag protein (37–39). During viral maturation, the cross-communication of the unprocessed Gag with distinct domains on the gp41 CT could possibly serve as a blocking effect of the HIV Env protein in a nonfusogenic state (40, 41). Such an internal mechanism of suppressing the Env-mediated fusion activity is necessary until the proteolytic processing of Gag has been completed in order to favor the subsequent maturation of the virions into infectious viral particles. In addition, the LLP2 motif has been strongly implicated in restricting the Env fusogenicity (26). Indeed, in the present study we observed that when the LLP2 motif was eliminated or partially truncated (i.e., in Tailless-, R6-, and R5-pseudotyped vectors), these hybrid vectors showed the highest biological titers and efficient in vitro transduction. Incomplete processing of Gag precursor (p55) proteins (Fig. 3a) and subsequent lower biological titers were observed for chimeric lentiviral preparations which bore the full-length LLP2 motif. Another possible interaction between the matrix domain of Gag and gp41 CT could be via the Tyr-based YXXL motif. This motif recycles the excessive HIV-1 Env GP from the host plasma membrane back into the cell via clathrin-coated pits (39, 42, 43). Several studies document that gp41 CT is found in a dynamic status where major conformation changes which favor membrane fusion occur upon viral attachment (4, 44, 45). Indeed, the N terminus (or first tyrosine signal) (719YSPL722) of gp41 CT, together with the “Ken” epitope and upon interaction with adaptor protein 2 (AP-2), functions in endocytosis (46). The fusion process is then further facilitated via interaction with AP-1 and AP-3-directed degradation which allows release of the LV genome into the host cell (46).

In the present study, this YXXL motif is present in both R6 and R5 but not in the Tailless-pseudotyped vectors, while the palmitylated Cys 762, which is implicated in HIV-1 Env attraction and association with lipid rafts in the host plasma membrane favoring the virus targeted localization and budding process (47), is included in the R5 construct. The results obtained from our in vitro transduction experiments showed that transduction efficiency is decreased when LVs are pseudotyped with long gp41CT, while this was not observed when Tailless, R5, and R6 envelope glycoproteins were utilized. Despite the fact that RVG/Tailless- and the R6-pseudotyped vectors had the best biological and physical titers, their infectivity values were lower than those of the R5-pseudotyped vectors. It is clear that vectors pseudotyped with glycoproteins bearing longer CTs than R5, although they exhibit physical titers comparable to that of the wild-type RVG and good efficiency of pseudotyping, fail to achieve high biological titers. This is comparable to the findings of previous studies on other retroviral CTs (15). The fact that RVG/gp41:R6-pseudotyped LV had the highest physical titers indicates that the presence of the 17-aa sequence in the CT (or the complete absence of LLPs and Ken sequence domains) can boost the viral production, making it a “key sequence” for this process. The above was further confirmed by the high physical titers obtained for the RVG/gp41:R10-pseudotyped vector (Fig. 4c), where the 17-aa sequence was inserted at the 5′ end of the wild-type RVG-B2c CT. Finally, superior biological titers were obtained when the envelope plasmid concentration was increased during production. This indicates that the R10 particle production requires more envelope in order to pseudotype efficiently.

Four vectors pseudotyped with chimeric envelopes, which had the best titers, were tested in vivo (titers are listed in Table 2). The RVG/VSVG(C)-pseudotyped vector was the term of comparison against all other pseudotypes tested and indeed showed transduction efficiency and retrograde transport comparable to previously published data (17). In contrast to findings by Kato et al. (12, 16), here we show better pseudotyping efficiency for this RVG/VSVG(C) hybrid vector than for wild-type RVG B2c-pseudotyped LV. This was reflected by better transduction in vitro; however, a drop of transduction efficiency and neuronal specificity in vivo (17) was reported. Even though the in vitro biological titers of RVG/Tailless-, wild-type RVG-, and RVG/VSVG(C)-pseudotyped LV were comparable, the RVG/Tailless vector had a better infectivity. However, when this was applied in vivo, despite producing similar striatal transduction efficiency, it exhibited poor retrograde transduction. This supports the hypothesis that the complete absence of CT–HIV-1 matrix interaction can produce infective vectors and that this altered incorporation process could be favored by the low steric hindrance of the long envelope GP CTs. However, the low retrograde transduction efficiency of this type of pseudotyping can be a consequence of the absence of a CT.

The generated pseudotyped LVs are expected to enter the host neurons in a manner similar to that for wild-type rabies virus, which binds to specific cellular receptors and induces receptor-mediated endocytosis and engagement of the endosomal retrograde trafficking pathway in neurons (reviewed in reference 48). Upon internalization, the virus is brought within the nonacidic endosome compartment which is retrogradely transported to the soma, where the lowering of the pH induces conformational changes of the GP trimer that favor the fusion between the viral particle and endosome membrane, thus releasing the capsid (44, 45, 49). The RVG/gp41:R6-pseudotyped LV showed the best efficiency among all the HIV-1 gp41 truncations following in vivo delivery. The transduction upon striatal application was double that for the other pseudotypes; however, its tropism was mainly glial, and its retrograde transduction was relatively superior to those of the RVG/VSVG(C) and RVG/Tailless pseudotypes. In this regard the performance, despite being far inferior to that of RVG/gp41:R5, was still comparable to that previously reported for B2c RVG (17). It is striking that RVG/gp41:R5, bearing only the Ken sequence and the LLP2 truncation, showed a slight but appreciable shift in tropism toward neurons. This could be related to previous reports of surface exposure of these loops (29, 50). We speculate that these motifs could result in an improved fusogenicity with the endosomal membrane upon acidification, leading to more efficient capsid release in the cytosol following viral trafficking in the axon, but further trafficking studies are necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

In conclusion, the present study shows the functional significance of the gp41 CT in lentiviral vector production and transduction. By manipulating this CT, we have managed to generate pseudotyped lentiviral vectors with transduction profiles superior to that of the wild-type RVG, ultimately enhancing their utility for gene transfer applications in the nervous system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tony Fooks (Animal Health and Veterinary Laboratories Agency, United Kingdom) for the kind gift of the SNB1 anti-rabies virus GP antibody, Hannah Taylor for help with volumetric measurements of striatal transduction, and Scarlett Gillespie for the help with Western blotting equipment. We also express our greatest gratitude to the Free Software Foundation (www.fsf.org) for their support of the development and use of the GNU/Linux operating system, software, and documentation (www.gnu.org). Among the many free software products used to realize this work and not already cited we wish to mention Scribus (open source desktop publishing; www.scribus.net) and GIMP (The GNU Image Manipulation Program; www.gimp.org).

This work was in part supported by Imperial College London starting funds to N.D.M. and a Seventh Framework Programme European Research Council Advanced Grant (no. 23314) to N.D.M. supporting A.T. and I.E.

None of the authors of this paper has declared any conflict of interest which may arise from being named as an author.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 26 December 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Canivet M, Hoffman AD, Hardy D, Sernatinger J, Levy JA. 1990. Replication of HIV-1 in a wide variety of animal cells following phenotypic mixing with murine retroviruses. Virology 178:543–551. 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90352-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chesebro B, Wehrly K, Maury W. 1990. Differential expression in human and mouse cells of human immunodeficiency virus pseudotyped by murine retroviruses. J. Virol. 64:4553–4557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lusso P, di Marzo Veronese F, Ensoli B, Franchini G, Jemma C, DeRocco SE, Kalyanaraman VS, Gallo RC. 1990. Expanded HIV-1 cellular tropism by phenotypic mixing with murine endogenous retroviruses. Science 247:848–852. 10.1126/science.2305256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spector DH, Wade E, Wright DA, Koval V, Clark C, Jaquish D, Spector SA. 1990. Human immunodeficiency virus pseudotypes with expanded cellular and species tropism. J. Virol. 64:2298–2308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu ZH, Chen SS, Huang AS. 1990. Phenotypic mixing between human immunodeficiency virus and vesicular stomatitis virus or herpes simplex virus. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 3:215–219 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cronin J, Zhang XY, Reiser J. 2005. Altering the tropism of lentiviral vectors through pseudotyping. Curr. Gene Ther. 5:387–398. 10.2174/1566523054546224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartz SR, Rogel ME, Emerman M. 1996. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 cell cycle control: Vpr is cytostatic and mediates G2 accumulation by a mechanism which differs from DNA damage checkpoint control. J. Virol. 70:2324–2331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazarakis ND, Azzouz M, Rohll JB, Ellard FM, Wilkes FJ, Olsen AL, Carter EE, Barber RD, Baban DF, Kingsman SM, Kingsman AJ, O'Malley K, Mitrophanous KA. 2001. Rabies virus glycoprotein pseudotyping of lentiviral vectors enables retrograde axonal transport and access to the nervous system after peripheral delivery. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10:2109–2121. 10.1093/hmg/10.19.2109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitrophanous K, Yoon S, Rohll J, Patil D, Wilkes F, Kim V, Kingsman S, Kingsman A, Mazarakis N. 1999. Stable gene transfer to the nervous system using a non-primate lentiviral vector. Gene Ther. 6:1808–1818. 10.1038/sj.gt.3301023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong LF, Azzouz M, Walmsley LE, Askham Z, Wilkes FJ, Mitrophanous KA, Kingsman SM, Mazarakis ND. 2004. Transduction patterns of pseudotyped lentiviral vectors in the nervous system. Mol. Ther. 9:101–111. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2003.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mentis GZ, Gravell M, Hamilton R, Shneider NA, O'Donovan MJ, Schubert M. 2006. Transduction of motor neurons and muscle fibers by intramuscular injection of HIV-1-based vectors pseudotyped with select rabies virus glycoproteins. J. Neurosci. Methods 157:208–217. 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kato S, Inoue K, Kobayashi K, Yasoshima Y, Miyachi S, Inoue S, Hanawa H, Shimada T, Takada M, Kobayashi K. 2007. Efficient gene transfer via retrograde transport in rodent and primate brains using a human immunodeficiency virus type 1-based vector pseudotyped with rabies virus glycoprotein. Hum. Gene Ther. 18:1141–1151. 10.1089/hum.2007.082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Federici T, Kutner R, Zhang XY, Kuroda H, Tordo N, Boulis NM, Reiser J. 2009. Comparative analysis of HIV-1-based lentiviral vectors bearing lyssavirus glycoproteins for neuronal gene transfer. Genet. Vaccines Ther. 7:1. 10.1186/1479-0556-7-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mochizuki H, Schwartz JP, Tanaka K, Brady RO, Reiser J. 1998. High-titer human immunodeficiency virus type 1-based vector systems for gene delivery into nondividing cells. J. Virol. 72:8873–8883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zingler K, Littman DR. 1993. Truncation of the cytoplasmic domain of the simian immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein increases Env incorporation into particles and fusogenicity and infectivity. J. Virol. 67:2824–2831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kato S, Kobayashi K, Inoue K, Kuramochi M, Okada T, Yaginuma H, Morimoto K, Shimada T, Takada M, Kobayashi K. 2011. A lentiviral strategy for highly efficient retrograde gene transfer by pseudotyping with fusion envelope glycoprotein. Hum. Gene Ther. 22:197–206. 10.1089/hum.2009.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carpentier DC, Vevis K, Trabalza A, Georgiadis C, Ellison SM, Asfahani RI, Mazarakis ND. 2012. Enhanced pseudotyping efficiency of HIV-1 lentiviral vectors by a rabies/vesicular stomatitis virus chimeric envelope glycoprotein. Gene Ther. 19:761–774. 10.1038/gt.2011.124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Funke S, Schneider IC, Glaser S, Muhlebach MD, Moritz T, Cattaneo R, Cichutek K, Buchholz CJ. 2009. Pseudotyping lentiviral vectors with the wild-type measles virus glycoproteins improves titer and selectivity. Gene Ther. 16:700–705. 10.1038/gt.2009.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Funke S, Maisner A, Muhlebach MD, Koehl U, Grez M, Cattaneo R, Cichutek K, Buchholz CJ. 2008. Targeted cell entry of lentiviral vectors. Mol. Ther. 16:1427–1436. 10.1038/mt.2008.128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Checkley MA, Luttge BG, Freed EO. 2011. HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein biosynthesis, trafficking, and incorporation. J. Mol. Biol. 410:582–608. 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.04.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murakami T, Freed EO. 2000. Genetic evidence for an interaction between human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix and alpha-helix 2 of the gp41 cytoplasmic tail. J. Virol. 74:3548–3554. 10.1128/JVI.74.8.3548-3554.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murakami T, Freed EO. 2000. The long cytoplasmic tail of gp41 is required in a cell type-dependent manner for HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein incorporation into virions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:343–348. 10.1073/pnas.97.1.343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dubay JW, Roberts SJ, Hahn BH, Hunter E. 1992. Truncation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane glycoprotein cytoplasmic domain blocks virus infectivity. J. Virol. 66:6616–6625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gabuzda DH, Lever A, Terwilliger E, Sodroski J. 1992. Effects of deletions in the cytoplasmic domain on biological functions of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoproteins. J. Virol. 66:3306–3315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu X, Yuan X, McLane MF, Lee TH, Essex M. 1993. Mutations in the cytoplasmic domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane protein impair the incorporation of Env proteins into mature virions. J. Virol. 67:213–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freed EO, Martin MA. 1996. Domains of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix and gp41 cytoplasmic tail required for envelope incorporation into virions. J. Virol. 70:341–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cosson P. 1996. Direct interaction between the envelope and matrix proteins of HIV-1. EMBO J. 15:5783–5788 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wyma DJ, Kotov A, Aiken C. 2000. Evidence for a stable interaction of gp41 with Pr55(Gag) in immature human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particles. J. Virol. 74:9381–9387. 10.1128/JVI.74.20.9381-9387.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu L, Zhu Y, Huang J, Chen X, Yang H, Jiang S, Chen YH. 2008. Surface exposure of the HIV-1 env cytoplasmic tail LLP2 domain during the membrane fusion process: interaction with gp41 fusion core. J. Biol. Chem. 283:16723–16731. 10.1074/jbc.M801083200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller MA, Garry RF, Jaynes JM, Montelaro RC. 1991. A structural correlation between lentivirus transmembrane proteins and natural cytolytic peptides. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 7:511–519. 10.1089/aid.1991.7.511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deschambeault J, Lalonde JP, Cervantes-Acosta G, Lodge R, Cohen EA, Lemay G. 1999. Polarized human immunodeficiency virus budding in lymphocytes involves a tyrosine-based signal and favors cell-to-cell viral transmission. J. Virol. 73:5010–5017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu P, Chertova E, Bess J, Jr, Lifson JD, Arthur LO, Liu J, Taylor KA, Roux KH. 2003. Electron tomography analysis of envelope glycoprotein trimers on HIV and simian immunodeficiency virus virions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:15812–15817. 10.1073/pnas.2634931100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gaudin Y, Tuffereau C, Durrer P, Brunner J, Flamand A, Ruigrok R. 1999. Rabies virus-induced membrane fusion. Mol. Membr. Biol. 16:21–31. 10.1080/096876899294724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chernomordik L, Chanturiya AN, Suss-Toby E, Nora E, Zimmerberg J. 1994. An amphipathic peptide from the C-terminal region of the human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein causes pore formation in membranes. J. Virol. 68:7115–7123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Egan MA, Carruth LM, Rowell JF, Yu X, Siliciano RF. 1996. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope protein endocytosis mediated by a highly conserved intrinsic internalization signal in the cytoplasmic domain of gp41 is suppressed in the presence of the Pr55gag precursor protein. J. Virol. 70:6547–6556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hourioux C, Brand D, Sizaret PY, Lemiale F, Lebigot S, Barin F, Roingeard P. 2000. Identification of the glycoprotein 41(TM) cytoplasmic tail domains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 that interact with Pr55Gag particles. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 16:1141–1147. 10.1089/088922200414983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freed EO, Martin MA. 1995. Virion incorporation of envelope glycoproteins with long but not short cytoplasmic tails is blocked by specific, single amino acid substitutions in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix. J. Virol. 69:1984–1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wyss S, Dimitrov AS, Baribaud F, Edwards TG, Blumenthal R, Hoxie JA. 2005. Regulation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein fusion by a membrane-interactive domain in the gp41 cytoplasmic tail. J. Virol. 79:12231–12241. 10.1128/JVI.79.19.12231-12241.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davis MR, Jiang J, Zhou J, Freed EO, Aiken C. 2006. A mutation in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein destabilizes the interaction of the envelope protein subunits gp120 and gp41. J. Virol. 80:2405–2417. 10.1128/JVI.80.5.2405-2417.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wyma DJ, Jiang J, Shi J, Zhou J, Lineberger JE, Miller MD, Aiken C. 2004. Coupling of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 fusion to virion maturation: a novel role of the gp41 cytoplasmic tail. J. Virol. 78:3429–3435. 10.1128/JVI.78.7.3429-3435.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murakami T, Ablan S, Freed EO, Tanaka Y. 2004. Regulation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Env-mediated membrane fusion by viral protease activity. J. Virol. 78:1026–1031. 10.1128/JVI.78.2.1026-1031.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Byland R, Vance PJ, Hoxie JA, Marsh M. 2007. A conserved dileucine motif mediates clathrin and AP-2-dependent endocytosis of the HIV-1 envelope protein. Mol. Biol. Cell 18:414–425. 10.1091/mbc.E06-06-0535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wyss S, Berlioz-Torrent C, Boge M, Blot G, Honing S, Benarous R, Thali M. 2001. The highly conserved C-terminal dileucine motif in the cytosolic domain of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein is critical for its association with the AP-1 clathrin adaptor. J. Virol. 75:2982–2992. 10.1128/JVI.75.6.2982-2992.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steckbeck JD, Sun C, Sturgeon TJ, Montelaro RC. 2010. Topology of the C-terminal tail of HIV-1 gp41: differential exposure of the Kennedy epitope on cell and viral membranes. PLoS One 5:e15261. 10.1371/journal.pone.0015261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Teixeira C, Gomes JR, Gomes P, Maurel F, Barbault F. 2011. Viral surface glycoproteins, gp120 and gp41, as potential drug targets against HIV-1: brief overview one quarter of a century past the approval of zidovudine, the first anti-retroviral drug. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 46:979–992. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.01.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hollier MJ, Dimmock NJ. 2005. The C-terminal tail of the gp41 transmembrane envelope glycoprotein of HIV-1 clades A, B, C, and D may exist in two conformations: an analysis of sequence, structure, and function. Virology 337:284–296. 10.1016/j.virol.2005.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang P, Ai LS, Huang SC, Li HF, Chan WE, Chang CW, Ko CY, Chen SS. 2010. The cytoplasmic domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane protein gp41 harbors lipid raft association determinants. J. Virol. 84:59–75. 10.1128/JVI.00899-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schnell MJ, McGettigan JP, Wirblich C, Papaneri A. 2010. The cell biology of rabies virus: using stealth to reach the brain. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8:51–61. 10.1038/nrmicro2260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Edwards TG, Wyss S, Reeves JD, Zolla-Pazner S, Hoxie JA, Doms RW, Baribaud F. 2002. Truncation of the cytoplasmic domain induces exposure of conserved regions in the ectodomain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope protein. J. Virol. 76:2683–2691. 10.1128/JVI.76.6.2683-2691.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cleveland SM, McLain L, Cheung L, Jones TD, Hollier M, Dimmock NJ. 2003. A region of the C-terminal tail of the gp41 envelope glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 contains a neutralizing epitope: evidence for its exposure on the surface of the virion. J. Gen. Virol. 84:591–602. 10.1099/vir.0.18630-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]