Abstract

In research as well as in clinical applications, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) has gained increasing popularity as a highly sensitive technique to study cytogenetic changes. Today, hundreds of commercially available DNA probes serve the basic needs of the biomedical research community. Widespread applications, however, are often limited by the lack of appropriately labeled, specific nucleic acid probes. We describe two approaches for an expeditious preparation of chromosome-specific DNAs and the subsequent probe labeling with reporter molecules of choice. The described techniques allow the preparation of highly specific DNA repeat probes suitable for enumeration of chromosomes in interphase cell nuclei or tissue sections. In addition, there is no need for chromosome enrichment by flow cytometry and sorting or molecular cloning. Our PCR-based method uses either bacterial artificial chromosomes or human genomic DNA as templates with α-satellite-specific primers. Here we demonstrate the production of fluorochrome-labeled DNA repeat probes specific for human chromosomes 17 and 18 in just a few days without the need for highly specialized equipment and without the limitation to only a few fluorochrome labels.

Keywords: chromosome enumeration, DNA repeats, DNA probes, fluorescence in situ hybridization, chromosomes 17 and 18

Molecular cytogenetic analyses using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) have gained an increasing role in the detection of numerical and structural chromosome aberrations in diverse fields such as perinatal cytogenetic analyses and preimplantation (Gray et al. 1991; Weier et al. 1991). Paralleling an increasing demand for DNA probes, the availability, cost, specificity, and efficiency of these probes have become important parameters. Consequently, resources generated in the course of the International Human Genome Project, yeast artificial chromosome and bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) libraries (Weissenbach et al. 1992; Ioannou et al. 1994), have been used extensively for the generation of chromosome- or locus-specific, single copy DNA probes (Weier et al. 1991,1994; Fung et al. 1998,2001). The present report describes the targeted amplification of chromosome-specific repeat DNA sequences by taking advantage of BAc clones that map close to a centromere. These serve as DNA templates for the PCR-based generation of specific DNA repeat probes yielding bright centromere-specific FISH signals on the target chromosomes.

Generally, the basic repeat units of α-satellite DNA are divergent AT-rich monomers of ~171 bp organized in chromosome-specific higher-order repeat units (Manuelidis 1978a,b; Mitchell et al. 1985; Willard 1991). α-Satellite DNA clusters most often contain monomer variants that differ from the consensus sequence by up to 40% (Rosandic et al. 2003). On human chromosomes, clusters of tandemly repeated alphoid DNA consist of distinct subfamilies whose total number exceeds the number of chromosomes (Jorgensen 1997). At least 33 different alphoid subfamilies have been identified to date based on their repeat organization. Whereas some subfamilies are specific for a single chromosome and others are shared among a small group of chromosomes (Rosandic et al. 2003), all are descendants from two ancestral prototype sequences (Alexandrov et al. 1988,2001). Every non-acrocentric human chromosome possesses at least one chromosome-specific family of α-satellite defined by a unique higher-order repeat unit, one to five monomers long. Moreover, this unique set of monomeric types of each suprachromosomal family is often characterized by alternating genomic sequences (Romanova et al. 1996). The primate × centromere, for instance, appears to have evolved through repeated proximal expansion events by unequal recombination occurring within the central, active region of the centromeric DNA (Schueler et al. 2005).

Almost all of the human BAC clones on hand have been mapped to the euchromatic portion of the genome and are mostly devoid of centromeric repeat sequences. However, BAC clones that map in the proximity of centromeres frequently contain single copies of DNA repeats such as satellite DNA derived from evolutionary expansion of centromeric regions (She et al. 2004). The human pericentromeric regions, i.e., regions on the proximal chromosome arms near the centromere, are known hot spots for duplication events as well as being prone to genetic instability (Eichler 1998). On certain chromosomes, considerable variability of segmental duplications exists within ~5 Mbp from the centromere, occasionally leaving clusters of alphoid sequences near the centromere (She et al. 2004). With an increasing number of fully sequenced BAC clones and, even more important, their DNA sequences publicly available, simple database searches allow rapid identification of promising clones for the generation of chromosome-specific DNA repeat probes. Hence, using BAC clones from pericentromeric regions such as PCR templates with α-satellite-specific primers effectively reduces the complexity of the α-satellite subfamilies and may result in chromosome-specific DNA probes. Without this reduction of complexity, cross-hybridization of the FISH probes to non-homologous chromosomes will render them unsuitable for detecting a single chromosome pair in metaphase or interphase cells. For cytogenetic diagnosis, however, the production of bright and specific DNA FISH probes with the desired fluorescent labels for multicolor, multitarget analyses is of paramount importance to reliably detect numerical and structural chromosomal abnormalities.

Using the evolutionary dispersion of alphoid repeats from their centromeric origin to more distal loci and the publicly available information on pericentromeric BACs to our advantage, we present a versatile and rapid procedure to generate chromosome-specific DNA repeat probes by PCR amplification and subsequent fluorochrome labeling. Althought the procedures outlined below can be applied to prepare DNA probes for other chromosomes or species, this report presents the preparation of DNA repeat probes specific for human chromosomes 17 and 18.

Material and Methods

BAC Clones Selection and DNA Preparation

BAC clones 285M22 (GenBank accession number AC131274) and 18L18 (GenBank accession number AC136363) from the RP11 library (Invitrogen; Gaithersburg, MD) were chosen based on information available from the UC Santa Cruz (UCSC) genome sequence database (http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgGateway) and the U.S. National Institutes of Health, National Center for Biotechnology Information (NIH/NCBI) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mapview/map_search.cgi?taxid=9606). Both BAC clones contain dispersed alphoid sequences. Detailed DNA sequence information as well as structural organization of the repeats within these BACs can be found in the above-mentioned databases. In addition, Rudd et al. (2006) present an excellent description of the evolutionary dynamics of alphoid sequences within the pericentromeric region of human chromosome 17.

BAC clones were cultured overnight in 10 ml Luria-Bertani medium containing 12.5 μg/ml chloramphenicol (Sigma; St Louis, MO) (Weier et al. 1995b), and DNA was isolated using an alkaline lysis DNA extraction protocol (Birnboim and Doly 1979; Weier et al. 1994,1995a).

PCR and DNA Labeling

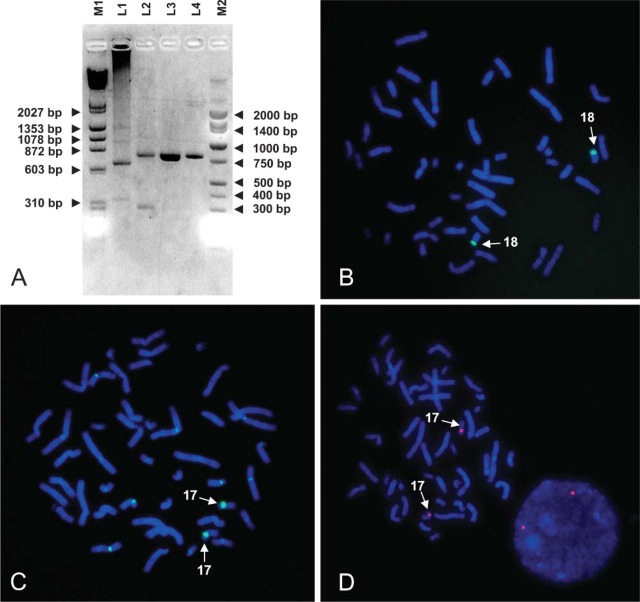

For PCR, 100 ng genomic DNA (Sigma) or BAC DNA was used as amplification templates. PCR reactions (50 μl) were performed using 0.02 U/μl Taq Polymerase (Invitrogen) or JumpStart Taq polymerase (Sigma) in 1X PCR buffer (Invitrogen), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, and 0.6 μM of the forward and reverse primers (Qiagen; Alameda, CA). Primers for chromosome 17 were P17H8-F1 and P17H8-R1-r (P17H8-F1: TGAACATTCCTATTGATAGAGCAG, P1H8-R1-r: CTCCAGTTTTTATGTGACCATAA, product size: 799 bp) (Waye and Willard 1986). Primers pYAM9-60F1 and pYAM9-60R2-r for chromosome 18 (pYAM9-60F1: CTGCAGCGTTCTGAGAAA-CATC, pYAM9-60R2-r: GCGGGAATTCATACAAATTGCAG, predicted product size: 1311 bp) were selected within the cloned pYAM 9–60 sequence (Alexandrov et al. 1991, gene bank accession number M65181). After an initial denaturation step of 1 min at 95C, 35 PCR cycles followed: denaturation at 95C for 30 sec, primer annealing at 54C for 1 min, and primer extension at 72C for 3 min. Ramp time was set to 1 min for all three steps. A final step at 72C for 10 min concluded the PCR. PCR products were confirmed on a 2% agarose gel (Figure 1A) by applying 5 μl of the PCR reaction mixed with 1 μl of 0.4 g/ml sucrose solution.

Figure 1.

(A) Agarose gel showing an inverted image of PCR products and sizemarker DNAs after ethidium bromide staining. Lane L1: chromosome 18 PCR, genomic DNA as template; L2: chromosome 17 PCR, genomic DNA as template; L3: chromosome 17 PCR, BAC RP11-285M22 as template; and L4: chromosome 17 PCR, BAC RP11-18L18 as template. Lanes M1 and M2 show two markers, a combined λ Hindlll/π4>×174 Haelll marker and a Lo marker (Bionexus; Oakland, CA), respectively. (B) After labeling and FISH, bright specific signals on chromosome 18 centromere were observed using the probe PCR, generated with genomic DNA (Lane L1 in A) as template. (C) The use of genomic DNA to generate a specific probe for chromosome 17 shown in Lane L2 in A resulted in more than two signals cross-hybridizing to other chromosome centromeres, which renders this probe useless for FISH. (D) Increased specificity of the chromosome 17-specific probe when using BAC RP11-285M22 as a PCR template (Lane L3 in A). Bright and very specific signals on both homologs can be seen.

At this point, random priming was used to label the PCR-derived probe DNAs with biotin-14-dCTP or digoxigenin-11-dUTP (Roche Diagnostics; Indianapolis, IN) using a commercial kit (BioPrime Kit; Invitrogen). When incorporating digoxigenin, the dTTP to digoxigenin-dUTP ratio in the reaction was adjusted to 2:1 (Weier et al. 1995b; Fung et al. 1998,2001).

FISH

For FISH, 1 μl of either DNA probe, 1 μl of human Cot-1 DNA (1 mg/ml; Invitrogen), 1 μl of salmon sperm DNA (10 mg/ml; Invitrogen), and 7 μl of the hybridization master mix (78.6% formamide, 14.3% dextran sulfate in 1.43X SSC, pH 7.0; 20X SSC is 3 M sodium chloride, 300 mM tri-sodium citrate) were thoroughly mixed and denatured at 76C for 10 min. For preannealing, hybridization mixture was then incubated at 37C for 30 min, allowing the Cot-1 DNA to preanneal to the probes. In parallel, metaphase slides prepared from phytohemagglutinin-stimulated peripheral blood lymphocytes from a karyotypically normal male (Fung et al. 2001) were denatured for 3 min at 76C in 70% formamide/2X SSC, pH 7.0, dehydrated in 70%, 85%, and 100% ethanol for 2 min each step, and allowed to air dry. Hybridization mixture was then carefully applied to the slides, covered with a 22 × 22 mm2 coverslip, and sealed with rubber cement. Slides were incubated overnight in a moist chamber at 37C. After removing rubber cement and the coverslips, slides were washed in 0.1X SSC at 43C for 2 min, then incubated in PNM [5% non-fat dry milk (NESTLÉ Carnation; Wilkes-Barre, PA), 1% sodium azide (Sigma) in PN buffer that is 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 8.0, 1% Nonidet-P40 (Sigma)] for 10 min at room temperature. Bound probes were detected with fluorescein-conjugated avidin (avidin DCS; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and rhodamine-labeled anti-digoxigenin antibodies (Roche Diagnostics). Finally, the slides were mounted in 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 0.5 μg/ml; Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) in antifade solution (Weier et al. 1995a,b).

Image Acquisition and Analysis

Fluorescence microscopy was performed on a Zeiss Axioskop microscope equipped with a filter set for simultaneous observation of Texas Red/rhodamine and FITC and a separate filter for DAPI detection (Chroma Technology; Brattleboro, VT). Images were collected using a cooled CCD camera (CCD-1300DS; VDS Vosskuehler, Osnabrück, FRG). Further processing and printing of images were done using the image processing software Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems; San Jose, CA).

Results

Using genomic DNA as template and α-satellite-specific primers for chromosome 18 (Alexandrov et al. 1991) for PCR, four bands were observed (Figure 1A, L1): a 700-bp strong band, a 350-bp band, and extra-high molecular mass bands ~900 bp and 1300 bp. The very high molecular smear at the top of Lane L1 was likely to be an artifact related to the use of human genomic DNA as amplification template DNA. After labeling of PCR products with biotin, hybridization, and subsequent detection with FITC-conjugated avidin, PCR products worked exquisitely well as a centromere-specific DNA probe for chromosome 18. Bright, unambiguous signals were visible on both homologs of chromosome 18 (Figure 1B). However, using the same approach, we could not obtain chromosome 17-specific DNA repeat probes. Two bands were observed (Figure 1A, L2) when using genomic DNA as template and chromosome 17 α-satellite-specific primers (Waye and Willard 1986) for PCR. These DNA probes did yield bright FISH signals at the centromere of chromosome 17. However, multiple cross-hybridization signals on non-homologous chromosomes were observed (Figure 1C).

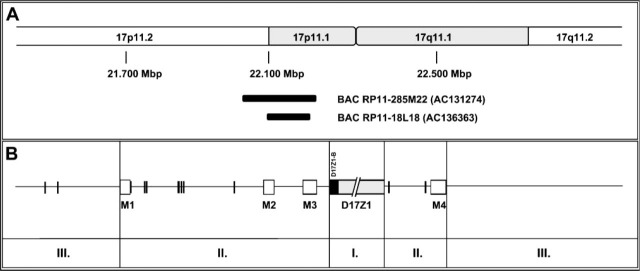

Because the first approach was not applicable for the preparation of chromosome 17 repeat probes with the desired high specificity, we used a second approach with two DNA templates isolated from chromosome 17-specific pericentromeric BAC clones containing alphoid repeat sequences (clones RP11-285M22 or RP11-18L18) in a modified PCR protocol (Figure 1A, L3 and L4, PCR product of ~799 bp). Both BAC clones were selected because of their pericentromeric map position and the fact that they contain alphoid DNA. First, BAC clone RP11-285M22 (Genbank accession number AC131274) and the shorter BAC clone RP11-18L18 (Genbank accession number AC136363) have been mapped in the pericentromeric region of chromosome 17, band p11.1-11.2 (Figure 2A, data from the Genbank database). Second, the chromosome 17 pericentromeric region contains two monomeric α-satellite clusters, M2 and M3 (Figure 2B) (Rudd et al. 2006), which provided annealing sites for our chromosome 17 α-satellite-specific PCR primers. Furthermore, we detected no extra-low molecular mass band when the BAC DNA as template was used instead of genomic DNA (Figure 1A, L3 and L4 vs L2). After labeling with either biotin or digoxigenin and detection with avidin-FITC or anti-digoxigenin-rhodamine, respectively, all probes prepared using the BAC DNAs yielded bright unambiguous signals at the centromeres of chromosome 17. Chromosome-specific probes prepared using BAC RP11-285M22 DNA (Figure 1D) were also slightly brighter than that using BAC RP11-18L18 (result not shown). Finally, chromosome 17- and 18-specific repeat DNA has also been successfully labeled by random priming with fluorochrome-conjugated nucleotides such as Alexa-Fluor 532-dUTP (yellow fluorescence emission; Invitrogen) and Cy5.5-dCTP (infrared emission; Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of alphoid repeats (vertical bars) and monomeric alphoid repeat clusters (boxes) as well as two selected BACs in the pericentromeric region of human chromosome 17. Two large cluster regions of α-satellite DNAs are found fully contained in the insert of BAC RP11-285M22. (A) Partial ideogram of chromosome 17. The Mbp numbers indicate the position on the chromosome according to the UCSC database. Two BACs, RP11-285M22 (Genbank accession number AC131274) and RP11-18L18 (Genbank accession number AC136363), and their relative position at chromosome 17 band p11.1-17p11.2 are represented according to the UCSC genome database's Golden Path. (B) Distribution of α-satellite DNA repeats on chromosome 17 depends on their location. I: centromere (D17Z1 and D17Z1-B) consists of tandemly repeated α-satellite monomers organized in higher-order repeats. Please note that the centromeric heterochromatin is not drawn to scale; II: pericentromeric region contains clusters of monomeric (M1-M4) and single α-satellite repeats; III: the distal regions contain interspersed repeats, single copy DNA, and genes, as well as a few isolated α-satellite repeats.

Discussion

FISH is a widely accepted molecular cytogenetic technique relying on chromosome- or gene-specific nucleic acid probes that produce unambiguous signals when bound to their respective targets. Despite a variety of commercially available FISH probes, DNA probes for many disease loci or centromeric probes labeled with a particular fluorochrome are often unavailable. Furthermore, multicolor FISH assays in basic and clinical research create an increasing demand for specifically designed probes. Large quantities of centromere-specific or ‘chromosome enumerator’ probe DNAs for labeling with any suitable fluorochrome or fluorochrome-conjugate can be generated rapidly following the inexpensive procedures described above.

The two approaches for rapid PCR synthesis of probes differ in the choice of DNA template and PCR primers: for a known chromosome-specific DNA repeat sequence, one can generate the probe DNA from genomic template DNA employing target-specific oligonucleotides. A BAC DNA template in the alternative approach reduces the template complexity when less specific PCR primers are used.

Table 1 shows a list of BAC clones that could potentially serve as templates for PCR. Whereas we kept the present study limited to BAC clones for chromosome 17, unique α-satellite DNA has been detected on 18/24 different human chromosome types using FISH probes. The remaining autosomes, i.e., chromosomes 5 and 19 (Baldini et al. 1989), 13 and 21 (Jorgensen et al. 1987), as well as 14 and 22 (Choo et al. 1989) possess highly homologous alphoid sequences, and DNA probes typically yield ambiguous FISH signals. Acrocentric human chromosomes also tend to exhibit a reduction in chromosome-specific α-satellite clusters, especially chromosome 21 with occasional low levels of this DNA (Weier and Gray 1992; Lo et al. 1999).

Table 1.

Pericentromeric bacterial artificial chromosomes (BAC) probe clones containing alphoid sequencesa that potentially may serve as templates for PCR-based production of centromere-specific probes

| Chromosomeb | Clonesc | BAC size (kb) | Location | Position (Mbp) | Repeatsd | Remark |

| 1 | 429E19 | 135 | 1q11.1 | 121.11 | +++ | Potential cross-hybridization with chromosomes 5, 19 |

| 134H2 | 337 | 1q12 | 141.70 | + | Potential cross-hybridization with chromosomes 5, 19 | |

| 2 | 469P16 | 46 | 2p11.1 | 91.66 | +++ | |

| 176F22 | 187 | 2q11.1 | 94.92 | + | ||

| 3 | 347K14 | 174 | 3p11.1 | 90.47 | +++ | |

| 125A11 | 203 | 3p11.1 | 90.42 | +++ | ||

| 4 | 107I5 | 143 | 4p11 | 48.82 | ++ | |

| 241F15 | 171 | 4p11 | 49.27 | + | ||

| 5 | 476O17 | 179 | 5p11 | 46.30 | +++ | Potential cross-hybridization with chromosomes 1, 19 |

| 185I4 | 148 | 5q11.1 | 49.54 | +++ | ||

| 6 | 136K2 | 168 | 6p11.1 | 58.81 | ++ | |

| 26M18 | 78 | 6q11.1 | 62.01 | + | ||

| 7 | 357N20 | 175 | 7p11.1 | 57.90 | ++ | |

| 320O14 | 211 | 7q11.21 | 61.95 | ++ | ||

| 8 | 449A14 | 158 | 8p11.1 | 43.82 | +++ | |

| 289H18 | 189 | 8q11.1 | 47.10 | +++ | ||

| 9 | 115C15 | 236 | 9p11.1 | 46.60 | + | |

| 69O9 | 156 | 9q12 | 66.62 | ++ | ||

| 10 | 96F8 | 163 | 10p11.1 | 39.11 | ++ | |

| 345K7 | 212 | 10q11.1 | 71.81 | +++ | ||

| 11 | 673H15 | 214 | 11p11.12 | 51.14 | +++ | |

| 45K11 | 197 | 11q11 | 54.60 | +++ | ||

| 12 | 282J17 | 170 | 12p11.1 | 34.66 | +++ | |

| 170L1 | 151 | 12q11.1 | 36.40 | +++ | ||

| 16 | 143I7 | 159 | 16p11.1 | 36.06 | +++ | |

| 416F8 | 26 | 16p11.2 | 44.96 | +++ | ||

| 17 | 285M22 | 185 | 17p11.1 | 22.13 | +++ | Reported here |

| 18L18 | 88 | 17p11.1 | 22.08 | ++ | Reported here | |

| 18 | 1133K23 | 137 | 18p11.21 | 15.33 | ++ | |

| 19 | 21H14 | 177 | 19p12 | 24.34 | +++ | Potential cross-hybridization with chromosomes 1, 5 |

| 775H18 | 203 | 19q12 | 32.53 | +++ | Potential cross-hybridization with chromosomes 1, 5 | |

| 20 | 155J16 | 138 | 20p11.1 | 26.20 | +++ | |

| 348I14 | 198 | 20q11.1 | 28.17 | ++ | ||

| X | 348G24 | 209 | Xp11.1 | 58.48 | +++ | |

| 168P24 | 187 | Xq11.1 | 61.86 | +++ | ||

| Y | 108I14 | 155 | Yp11.2 | 105.61 | ++ | |

| 910C6 | 174 | Yq11.1 | 119.15 | ++ |

UC Santa Cruz Genome Browser, http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgGateway.

No chromosomes 13, 14, 15, 21, or 22 specific pericentromeric clones.

All clones are from the RP11 library.

Repeat content: +, <20 copies; ++, 20–50 copies; +++, >50 copies.

In a targeted approach, we searched publicly accessible databases to define primers specific for the chromosome 18-derived alphoid cluster within the cloned pYAM 9–60 sequence (Alexandrov et al. 1991). Although we used genomic DNA as a PCR template to generate the specific chromosome 18 probe DNA, it is very likely that other DNA templates such as cells from cultures, biopsies, or hair follicles lead to similar results. PCR products generated with the primer set pYAM9-60F1/-60R2-r appeared on agarose gels as multiple products with a single band in the target size region plus some amount of high molecular mass DNA fragments (Figure 1A, Lane L1). The resulting biotinylated DNA probe detected with avidin-FITC showed a unique, chromosome-specific hybridization signal at the centromere of chromosome 18 (Figure 1B). The higher-order alphoid centromeric repeats of chromosome 18 seem unique to this chromosome because they do not produce cross-hybridization signals when used in FISH.

High concentrations of clusters of tandemly repeated DNA are major obstacles in the generation of high-resolution physical maps of the human as well as other genomes (Cheng and Weier 1997). Consequently, the first draft of the human genome map does not cover the centromeric regions of the chromosomes or the heterochromatic regions near the centromeres of chromosomes 1, 9, 16, and 19 (International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium 2004). However, DNA repeats cluster originating from the centromere region can be found dispersed on proximal chromosome arms outside the centromere (Rocchi et al. 1991; She et al. 2004).

Pericentromeric regions are defined as sequences extending from the centromere to the first cytogenetic band on a chromosome arm (Eichler et al. 1998). In contrast to the highly conserved repetitive sequences within the human centromeres, pericentromeric sequences are enriched for inter- and/or intrachromosomally duplicated DNA (37.3%), single copies (49.7%), and satellite sequences (13%) (Grady et al. 1992). Chromosome 18, for instance, consists of large tracts of duplications within its pericentromeric region (Mudge and Jackson 2005). These duplications of repeated DNA sequences are likely due to unequal crossing-over (Smith 1976; Willard 1991; Schueler et al. 2005). Hence, with the number of fully sequenced BAC clones progressively increasing, the BAC clones mapped to either side of the centromere may contain interspersed alphoid repeats within small clusters (see Table 1) and can serve as PCR templates to amplify amounts of chromosome-specific probe DNA.

For chromosome 17, the use of genomic DNA was not sufficient to generate a chromosome-specific DNA probe (Figure 1C). The primers employed (P17H8-F1 and P17H8-R1-r) (Waye and Willard 1986, Genbank accession number M13882) seemed to be specific for a family of alphoid repeats not exclusively located on chromosome 17. Five suprachromosomal families of α-satellite DNA can be found on human chromosomes originating from different evolutionary events. Whereas chromosome 18 shows two distinct families, 2 as well as 4 and 5, chromosome 17 expresses the suprafamilies 3 and 4 (Alexandrov et al. 2001) with two distinct classes of monomeric α-satellite in the centromeric region, at which the M3 monomeric α-satellite on band 17p11 is more closely related to higher order α-satellite (Rudd et al. 2006) (Figure 2). Thus, BACs from the proximal arms of chromosome 17 contain single copies of a subfamily of alphoid DNA repeats (Rudd et al. 2006). Two pericentromeric BACs have been mapped to 17p11.1-17p11.2, RP11-285M22 at the position 22.032-22.197 Mbp and the slightly shorter clone RP11-18L18 at position 22.098-22.170 Mbp. In a PCR with the P17H8-F1 and P17H8-R1-r primers and the selected BACs as templates, DNA probes were generated specifically for the centromere of chromosome 17 (Figure 1D).

In summary, the rapid approaches described here provide large amounts of DNA specific for the alphoid DNA repeats of chromosomes 17 and 18, which can be labeled with reporter molecules or fluorochromes of choice by either one of the readily available techniques, i.e., random priming, nick translation, tailing, or amination. The resulting chromosome-specific DNA probes have been successfully used for FISH resulting in bright, unambiguous signals in interphase and metaphase cells. Whereas commercial probes remain limited with respect to the kind and number of available fluorescent haptens, our approach will allow selection of any one of many commercially available fluorochromes for the DNA probes. This is expected to greatly facilitate a multitude of applications, among them Spectral Imaging analyses where it is necessary to use five to eight differently labeled FISH probes simultaneously (Fung et al. 2000,2001).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH Grants CA-80792 and CA-88258 and a grant from the Director, Office of Energy Research, Office of Health and Environmental Research, U.S. Department of Energy (under contract DE-AC-03-76SF00098). Additional support was provided by grants from the United States Army Medical Research and Material Command, United States Department of the Army (DAMD17-99-1-9250, DAMD17-00-1-0085). A.B. was supported in part by a grant from the University of California Discovery Program (BIO03-10414 to JF). J.F. was supported in part by NIH Grants HD-045736 and HD-041425. This publication was made possible by funds received from the Cancer Research Fund, under Interagency Agreement #97-12013 (University of California, Davis, contract #98-00924V) with the Department of Health Services, Cancer Research Section.

Literature Cited

- Alexandrov I, Kazakov A, Tumeneva I, Shepelev V, Yurov Y. (2001) Alpha-satellite DNA of primates: old and new families. Chromosoma 110:253–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrov IA, Mashkova TD, Akopian TA, Medvedev LI, Kisselev LL, Mitkevich SP, Yurov YB. (1991) Chromosome-specific alpha satellites: two distinct families on human chromosome 18. Genomics 11:15–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrov IA, Mitkevich SP, Yurov YB. (1988) The phylogeny of human chromosome specific alpha satellites. Chromosoma 96:443–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldini A, Smith DI, Rocchi M, Miller OJ, Miller DA. (1989) A human alphoid DNA clone from the EcoRI dimeric family: genomic and internal organization and chromosomal assignment. Genomics 5:822–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnboim HC, Doly J. (1979) A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 7:1513–1523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J-F, Weier H-UG. (1997) Approaches to high resolution physical mapping of the human genome. In Fox CF, Connor TH, eds. Biotechnology International. San Francisco, Universal Medical Press, 149–157 [Google Scholar]

- Choo KH, Vissel B, Earle E. (1989) Evolution of ά-satellite DNA on human acrocentric chromosomes. Genomics 5:332–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler EE. (1998) Masquerading repeats: paralogous pitfalls of the human genome. Genome Res 8:758–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler EE, Hoffman SM, Adamson AA, Gordon LA, McCready P, Lamerdin JE, Mohrenweiser HW. (1998) Complex beta-satellite repeat structures and the expansion of the zinc finger gene cluster in 19p12. Genome Res 8:791–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung J, Hyun W, Dandekar P, Pedersen RA, Weier H-UG. (1998) Spectral imaging in preconception/preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) of aneuploidy: multi-colour, multi-chromosome screening of single cells. J Assist Reprod Genet 15:322–329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung J, Weier H-UG, Goldberg JD, Pedersen RA. (2000) Multilocus genetic analysis of single interphase cells by Spectral Imaging. Hum Genet 107:615–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung J, Weier H-UG, Pedersen RA, Zitzelsberger HF. (2001) Spectral imaging analysis of metaphase and interphase cells. In Rauten-strauss B, Liehr T, eds. FISH Technology-Springer Lab Manual. Berlin, Springer Verlag, 363–387 [Google Scholar]

- Grady DL, Ratliff RL, Robinson DL, McCanlies EC, Meyne J, Moyzis RK. (1992) Highly conserved repetitive DNA sequences are present at human centromeres. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:1695–1699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JW, Lucas J, Kallioniemi O, Kallioniemi A, Kuo WL, Straume T, Tkachuk D, et al. (1991) Applications of fluorescence in situ hybridization in biological dosimetry and detection of disease-specific chromosome aberrations. Prog Clin Biol Res 372:399–411 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium (2004) Finishing the euchromatic sequence of the human genome. Nature 431:931–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannou P, Amemiya C, Garnes J, Kroisel P, Shizuya H, Chen C, Batzer M, et al. (1994) A new bacteriophage P1-derived vector for the propagation of large human DNA fragments. Nat Genet 6:84–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen AL. (1997) Alphoid repetitive DNA in human chromosomes. Dan Med Bull 44:522–534 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen AL, Bostock CJ, Bak AL. (1987) Homologous subfamilies of human alphoid repetitive DNA on different nucleolus organizing chromosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 84:1075–1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo AWI, Liao GCC, Rocchi M, Choo KHA. (1999) Extreme reduction of chromosome-specific ά-satellite array is unusually common in human chromosome 21. Genome Res 9:895–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manuelidis L. (1978a) Chromosomal localization of complex and simple repeated human DNAs. Chromosoma 66:23–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manuelidis L. (1978b) Complex and simple sequences in human repeated DNAs. Chromosoma 66:1–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AR, Gosden JR, Miller DA. (1985) A cloned sequence, p82H, of the alphoid repeated DNA family found at the centromeres of all human chromosomes. Chromosoma 92:369–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudge JM, Jackson MS. (2005) Evolutionary implications of pericentromeric gene expression in humans. Cytogenet Genome Res 108:47–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocchi M, Archidiacono N, Ward DC, Baldini A. (1991) A human chromosome 9-specific alphoid DNA repeat spatially resolvable from satellite 3 DNA by fluorescent in situ hybridization. Genomics 9:517–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanova LY, Deriagin GV, Mashkova TD, Tumeneva IG, Mushegian AR, Kisselev LL, Alexandrov IA. (1996) Evidence for selection in evolution of alpha satellite DNA: the central role of CENP-B/pJ alpha binding region. J Mol Biol 261:334–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosandic M, Paar V, Gluncic M, Basar I, Pavin N. (2003) Key-string algorithm-novel approach to computational analysis of repetitive sequences in human centromeric DNA. Croat Med J 44:386–406 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd MK, Wray GA, Willard HF. (2006) The evolutionary dynamics of ά-satellite. Genome Res 16:88–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schueler MG, Dunn JM, Bird CP, Ross MT, Viggiano L, Rocchi M, Willard HF, et al. (2005) Progressive proximal expansion of the primate X chromosome centromere. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:10563–10568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- She X, Horvath JE, Jiang Z, Liu G, Furey TS, Christ L, Clark R, et al. (2004) The structure and evolution of centromeric transition regions within the human genome. Nature 430:857–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GP. (1976) Evolution of repeated DNA sequences by unequal crossover. Science 191:528–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waye JS, Willard HF. (1986) Structure, organization, and sequence of alpha satellite DNA from human chromosome 17: evidence for evolution by unequal crossing-over and an ancestral pentamer repeat shared with the human X chromosome. Mol Cell Biol 6:3156–3165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weier HU, Gray JW. (1992) A degenerate alpha satellite probe, detecting a centromeric deletion on chromosome 21 in an apparently normal human male, shows limitations of the use of repeat probes for interphase ploidy analysis. Anal Cell Pathol 4:81–86 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weier HU, Kleine H-D, Gray JW. (1991) Labeling of the centromeric region on human chromosome 8 by in situ hybridization. Hum Genet 87:489–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weier HU, Rosette CD, Matsuta M, Zitzelsberger H, Matsuta M, Gray J. (1994) Generation of highly specific DNA hybridization probes for chromosome enumeration in human interphase cell nuclei: isolation and enzymatic synthesis of alpha satellite DNA probes for chromosome 10 by primer directed DNA amplification. Methods Mol Cell Biol 4:231–248 [Google Scholar]

- Weier HUG, Rhein AP, Shadravan F, Collins C, Polikoff D. (1995a) Rapid physical mapping of the human trk proto-oncogene (NTRK1) gene to human chromosome 1q21-22 by P1 clone selection, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and computer-assisted microscopy. Genomics 26:390–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weier H-UG, Wang M, Mullikin JC, Zhu Y, Cheng JF, Greulich KM, Bensimon A, et al. (1995b) Quantitative DNA fiber mapping. Hum Mol Genet 4:1903–1910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissenbach J, Gyapay G, Dib C, Vignal A, Morissette J, Millasseau P, Vaysseix G, et al. (1992) A second-generation linkage map of the human genome. Nature 359:794–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willard HF. (1991) Evolution of alpha satellite. Curr Opin Genet Dev 1:509–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]