Abstract

The European Cancer Concord is a unique patient-centered partnership that will act as a catalyst to achieve improved access to an optimal standard of cancer care and research for European citizens. In order to provide tangible benefits for European cancer patients, the partnership proposes the creation of a “European Cancer Patient’s Bill of Rights,” a patient charter that will underpin equitable access to an optimal standard of care for Europe’s citizens.

Introduction

Cancer and the provision of cancer care places a significant and growing burden on patients, citizens, and economies. Europe provides some of the best cancer care in the world and conducts high-quality, globally recognized cancer research. There are still significant disparities, however, in public information about cancer, accessing cancer care, delivering optimal treatment, supporting cancer survivorship, and integrating cancer research and innovation across European countries. In addition, costs of current treatments and long-term follow-up are placing significant economic burdens on European health care systems. Improvements in quality of care, translation of research discoveries, and promotion of innovation will have to be achieved within affordable economic models.

Acknowledging these challenges, a group of European oncology leaders have formed a partnership with cancer patients and their representatives. The European Cancer Concord (ECC) is a unique patient-centered partnership that will act as a catalyst to achieve improved access to an optimal standard of cancer care and research for European citizens. The strength of this partnership among health care professionals, patient advocacy organizations, and patients is essential to bring about the changes required to improve cancer-related outcomes across Europe. Cost-effective cancer care and cancer research excellence can contribute significantly to the wealth and health of the European citizen.

Strengthening and upholding the rights of individual cancer patients and their families are the guiding principles of this initiative. In order to provide tangible benefits for European cancer patients, the ECC proposes the creation of a “European Cancer Patient’s Bill of Rights,” a patient charter that will underpin equitable access to an optimal standard of care for Europe’s citizens. Three patient-centered principles (termed “Articles”) underpin the European Cancer Patient’s Bill of Rights:

Article 1: The right of every European citizen to receive the most accurate information and to be proactively involved in his/her care.

Article 2: The right of every European citizen to optimal and timely access to appropriate specialized care, underpinned by research and innovation.

Article 3: The right of every European citizen to receive care in health systems that ensure improved outcomes, patient rehabilitation, best quality of life and affordable health care.

The Global Burden of Cancer

At a global level, the burden of cancer is rising, with incidence projected to increase from 12.7 million in 2008 to 21.4 million in 2030 [1]. Cancer represents a significant cause of mortality worldwide, with 7.6 million deaths in 2008 [2]. In the developing world, cancer causes more deaths than HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria combined [3]. Morbidity and quality-of-life issues impose an additional burden, reflected in the loss of ∼170 million healthy life-years worldwide due to cancer and its sequelae in 2008 [4]. That figure translates to a global economic impact from premature death and disability of €895 billion, equivalent to 1.5% of the world’s gross domestic product [5].

The Burden of Cancer in Europe

In Europe in 2012, there were an estimated 3.45 million new cases of cancer and 1.75 million cancer deaths [6]. The aging population will result in significant increases in absolute numbers of cancer cases over the next 30 years [7, 8]. The recently released World Health Organization report, European Health Report 2012: Charting the Way to Well-Being, highlights the significant burden that cancer places on the European citizen [9]. In 28 of the 53 countries covered by the report, cancer has replaced cardiovascular disease as the leading cause of premature death [9, 10]. This increasing cancer burden will not only affect patients and their families but will also be a significant issue for health care systems and for the future economic competitiveness of Europe.

Cancer in Europe: The Positives

Impressive progress in cancer control has been achieved in the last 30 years, with European scientists and clinicians contributing significantly to gold standard advances that have improved cancer outcomes globally. Measurable improvements have been achieved for certain cancers, including testicular, breast, malignant lymphoma, gastric, colorectal, and leukemia. Many of these advances emphasize how pan-European collaborative approaches can yield significant benefits for cancer patients [11].

In addition, public health policies on tobacco have reduced the incidence of lung and other tobacco-related cancers in men, although lung cancer mortality in women will soon surpass breast cancer in the European Union [12]. Ireland became the first country in the world to introduce a national ban on smoking in the workplace, catalyzing a pan-European approach to reducing tobacco use. European scientists have been at the forefront of innovative screening and vaccination approaches for cervical cancer [13, 14]. Moreover, Europe has promoted the development of meritocratic pan-national research networks (e.g., L’Institut National du Cancer in France [15] and the National Cancer Research Institute in the United Kingdom [16]) and effective pan-European collaborative groups (e.g., European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer, TransBIG, Pan-European Trials in Adjuvant Colon Cancer, and the CONCORD study [11, 17–19]) that have supported Europe’s leadership in large practice-changing randomized clinical trials. Increased participation in these trials and associated translational research studies have allowed European patients to benefit from the latest diagnostic and therapeutic advances; however, there are significant disparities between Europe and the U.S. and particularly within Europe itself in accessing optimal care and innovative cancer treatment in a timely fashion.

Cancer in Europe: The Negatives

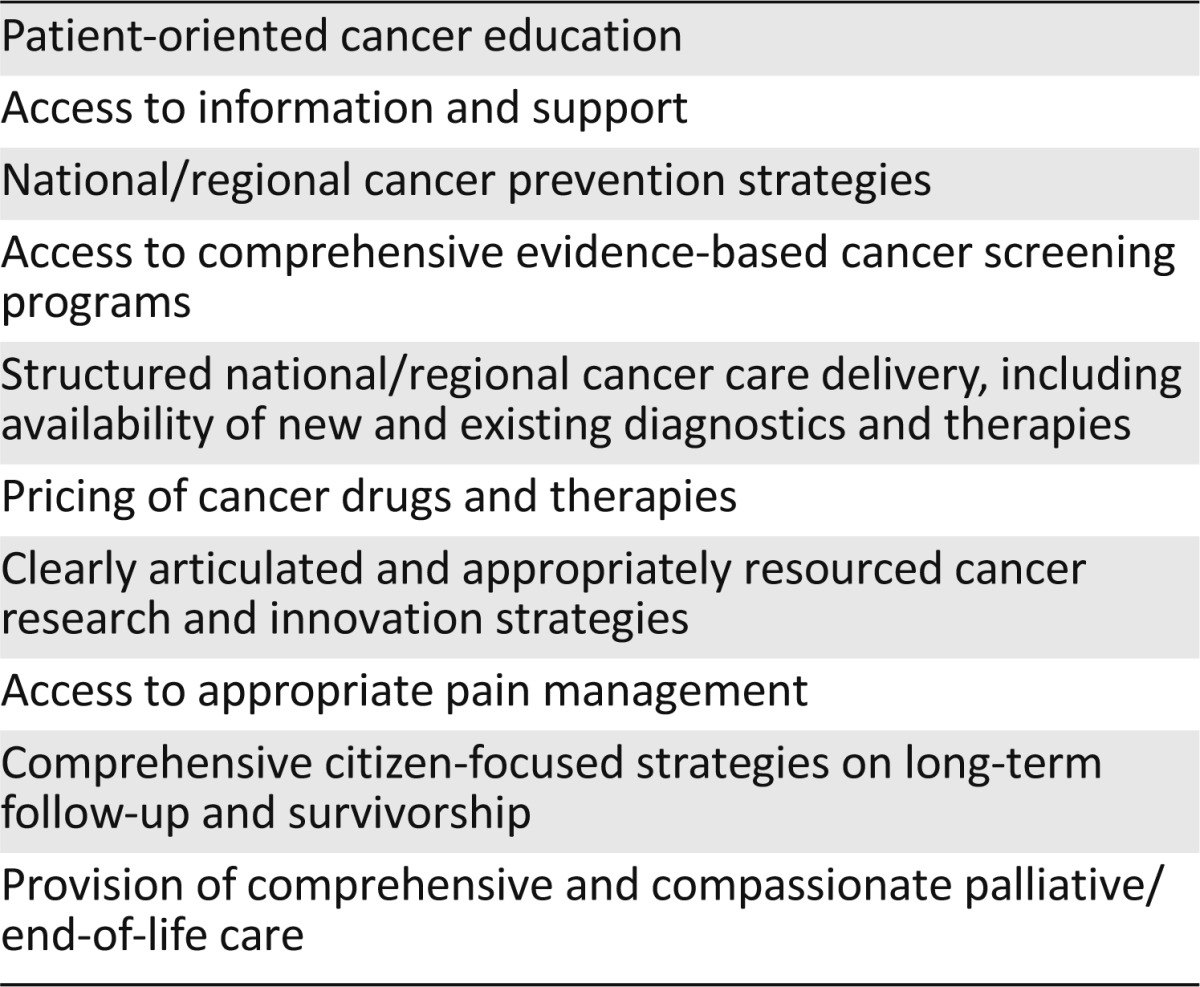

The recent series in The Lancet on “Health in Europe” highlighted increasing disparities both between and within countries in Europe [20], with cancer a prime example of this inequality. Significant differences in cancer survival rates persist between individual European countries and regions [21, 22] and are linked to socioeconomic status [23, 24], patient age [25], access to quality care [22, 23], and lack of a comprehensive National Cancer Control Plan (NCCP). The just-published EUROCARE-5 study, although indicating a trend of improving survival throughout Europe, highlights significant disparities in outcome between different European nations [26]. The lack of cancer registration data in many European countries, combined with a significant dearth of population-based clinical efficacy data (outside the context of clinical trials), needs to be addressed. The current pricing of certain cancer drugs is becoming unsustainable, as was recently highlighted by a large group of international experts involved in the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia [27]. Although genetic testing is crucial in identifying risk in a number of inherited cancers, countries such as Romania have no public access to BRCA1/2 testing (A. Eniu, Cancer Institute “I. Chiricuta” Department of Breast Tumors, Cluj-Napoca, personal communication). Worrying disparities identified at all stages of the cancer continuum (Table 1) reflect the challenges to delivery of effective cancer health care in Europe.

Table 1.

Disparities in cancer health care in Europe

A further obstacle to providing optimal treatment has been the European Clinical Trials Directive. Its introduction in 2001 corresponded with a 25% overall reduction in the number of clinical trials in Europe, and in certain countries, the reduction has been more than 50% [28]. Given these figures, it is imperative that the current revision of the directive [29] ensures more effective clinical trial activity for the European cancer patient. The two-step process for registration of new drugs—involving both European Medicines Agency approval and, in many countries, a health technology assessment—along with a variety of local issues (e.g., pricing negotiations, costs) can also lead to significant differences in time to access for new therapeutic interventions between European nations when compared with the U.S. Recognizing that incremental innovation must be pursued to foster research, a Europe-wide harmonization of health technology assessment methods, mediated through collaborative networks such as the European Network for Health Technology Assessment [30], is necessary to close the gap in access to new diagnostics and treatments (radiotherapy, surgery, medicines, devices).

Shaping a Patient-Oriented Strategy for Cancer Care in Europe: The ECC and the European Cancer Patient’s Bill of Rights

Recognizing the need to address the pressing issues noted and to place the cancer patient at the heart of the solution [31], the ECC has been established, comprising European oncology leaders in a unique partnership with cancer patients, caregivers, and their advocates (supplemental online Appendix 1). The strength of this cooperative approach is essential to accelerate the changes required to improve cancer-related outcomes for all European citizens. The ECC is a patient-centered partnership that aims to enable improved access to public education about cancer, cancer care, cancer research, and innovation. The ECC is dedicated to improving the outcomes for all cancer patients in Europe by promoting a shared understanding of the key issues in cancer awareness, research, prevention, rapid access to appropriate specialized treatment, care delivery, rehabilitation, and patient survivorship and by mobilizing all stakeholders to implement improved innovation in cancer care in a cost-effective manner across Europe.

The ECC is dedicated to improving the outcomes for all cancer patients in Europe by promoting a shared understanding of the key issues in cancer awareness, research, prevention, rapid access to appropriate specialized treatment, care delivery, rehabilitation, and patient survivorship and by mobilizing all stakeholders to implement improved innovation in cancer care in a cost-effective manner across Europe.

As part of a “Wealth is Health” strategy that empowers European citizens, the ECC has created a European Cancer Patient’s Bill of Rights, a charter to challenge the current inequalities that cancer patients in Europe experience on a daily basis. This bill of rights defines fundamental pan-European quality standards for provision of information, access and delivery of cancer care and research to European citizens. Through this patient-focused approach, the ECC enshrines the principles of equitable access to an appropriate and earliest possible diagnosis and a defined optimal quality of specialized care and clinical management for every cancer patient across Europe. Optimal cancer care not only contributes to the health of European citizens but also provides demonstrable economic benefit, with earlier access to high-quality diagnosis leading to more successful therapeutic intervention and facilitating a return to more active daily living, including a return to the workplace when relevant.

Realizing the Vision: The European Cancer Patient’s Bill of Rights

Three patient-centered principles underpin the European Cancer Patient’s Bill of Rights:

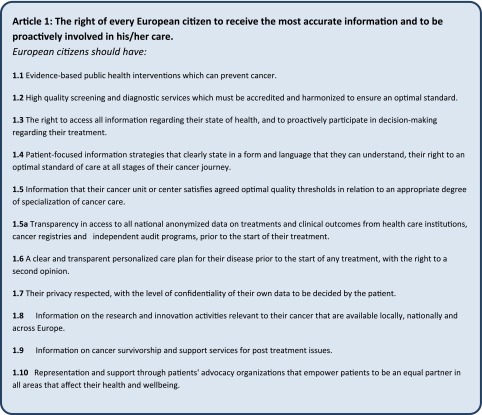

Article 1: The right of every European citizen to be informed and involved in his/her care

Cancer services must be patient centered, reflecting the views and needs of patients and their families. Individuals may have different perceptions of their needs than health care professionals. Good communication between health care professionals and patients will greatly improve care and enhance patient satisfaction. Shared decision making, involving a two-way transparent process between the health care providers and the European citizen, must be the overarching theme of this first principle. The full text of Article 1 is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Article 1, European Cancer Patient’s Bill of Rights.

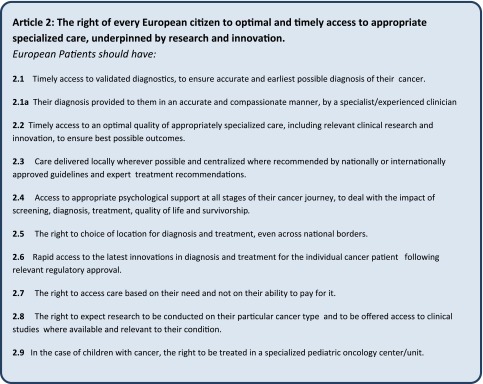

Article 2: The right of every European citizen to optimal and timely access to appropriate specialized care, underpinned by research and innovation

Access to essential cancer services must be the right of every European citizen, regardless of socioeconomic status, gender, age, or nationality. Clear pathways of access to clinical innovation and associated research activities must inform all stages of the patient’s cancer journey. This second principle depends on equitable and transparent access to optimal cancer care. The full text of Article 2 is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Article 2, European Cancer Patient’s Bill of Rights.

Article 3: The right of every European citizen to receive care in health systems that ensure improved outcomes, patient rehabilitation, best quality of life, and affordable health care

Cancer care at a national level must be organized in health care systems according to an integrated, efficiently budgeted NCCP that conforms to European guidelines and best international practice. The NCCP should develop a cancer center/cancer network/multidisciplinary team model that captures all aspects of cancer care, research, and innovation, from diagnosis through treatment and rehabilitation, including patient survivorship and end-of-life care. A comprehensive and holistic approach, encompassing the entire cancer care continuum, must inform this third principle. The full text of Article 3 is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Article 3, European Cancer Patient’s Bill of Rights.

Advancing the Cancer Agenda in an Era of Economic Austerity

Strengthening health care systems is key to delivering strategies that will gain traction in optimizing cancer outcomes. In addition to the increasing health burden, the need to consider affordability and methods to “bend the cancer cost curve” [32] must be addressed. Policy leaders, health care professionals, pharmaceutical and medical technologies industries, patients, and patient advocacy organizations must engage constructively to deliver tangible solutions. The American Society of Clinical Oncology has “identified the rising cost of cancer care as an opportunity to sharpen the focus on the need to ensure high-quality care while reducing unnecessary expense for our patients, their families, and society at large” [33]. Recently, the Institute of Medicine’s National Cancer Policy Forum convened a public workshop, “Delivering Affordable Cancer Care in the 21st Century,” to investigate ways to ensure that patients have access to high-quality, affordable cancer care in these times of economic austerity [34]. The subsequent report, “Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis” [35], underscores the burgeoning challenges that cancer presents to the U.S. health care system, particularly when we consider that the population aged 65 years or older in the U.S. will increase from ∼40 million in 2009 to nearly 90 million by 2050 [36].

In Europe, increasing cancer incidence has not been matched by proportionate rises in cancer-related spending within European health budgets, as is particularly evident with the differences in the percentages of gross domestic product spent on health care. There are significant differences in cancer budgets across Europe [20, 37–39], particularly in cancer health care spending in Central and Eastern Europe [37, 38], and these differences, combined with the inability to provide standard-of-care technologies in different European countries at prices based on national purchasing power, contribute to a lack of equity that must be addressed. A recently published study of the economic burden of cancer in the EU-27 countries (EU members from January 2007 through June 2013) found major differences in spending per cancer capita between countries [40].

Under-resourcing of cancer health care, particularly in the context of an increasing cancer burden, will lead to increased morbidity and mortality, spiraling associated health costs, and significant loss of productive life-years and will negatively affect the health of European citizens and economies. However, the resourcing of cancer health care in European countries must be considered in the context of a viable NCCP [15], with a clearly defined economic strategy, to ensure that additional spending translates into quality care and improved outcomes for cancer patients.

Innovation as a Key Driver of Improved Cost-Effective Cancer Care

The economic burden of cancer worldwide is now approaching €1 trillion, and the associated lost years of life and productivity mean that cancer now places the largest economic drain on the global economy of any disease in the world [5]. Cancer diagnostics (imaging, biomarkers) and therapies (surgery, radiation, new medicines and devices) have led to statistically significant increases in 1-year and 5-year survival rates and improvements in cancer outcomes, with significant quality-adjusted benefit achieved at a fraction of the economic cost of increased morbidity, mortality, and loss of productive life-years [41–46]. A clear example of this progress is breast cancer, for which more effective management by innovative diagnostic and therapeutic approaches has been accompanied by approximately a fivefold increase in return on investment [42, 45]. In France, it is estimated that diagnostic and therapeutic innovation has contributed to a significant decline in cancer mortality rates in the period 2002–2006 [42, 44, 46].

It is important to stress, as voiced by many participants at the recent Institute of Medicine workshop [34], that diagnostic and therapeutic innovation can increase the value of improved health and outweigh the additional costs only if implemented with a structured, cost-effective approach that emphasizes measurable improvements in outcome for the cancer patient [33, 37]. In this regard, innovative models such as L’Institut National du Cancer’s national genomics platform support a personalized medicine approach that delivers quality cancer care for the patient and value for money for the health care payer [42, 47]. Resourcing and pricing issues must be addressed in a meaningful and transparent fashion to achieve a just price, as highlighted in the recent article [48] and accompanying editorial [49] in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, ensuring optimal value in the delivery of quality care for patients. The use of comparative effectiveness research to help pursue a strategy that balances value and cost, leading to a quality, cost-effective solution for cancer patients, is pertinent to this debate. Maximizing clinical trial and research activity at the pan-European level also provides an unrivaled framework for delivering “added value” for European patients and should be vigorously pursued.

Our vision for improved cancer care for European citizens, empowered by research and innovation, aims to encourage the delivery of cost-effective, evidence-based care that will improve outcomes for cancer patients, consistent with the aims of the World Cancer Declaration, which calls for significant improvement in global cancer survival rates by 2020.

Our vision for improved cancer care for European citizens, empowered by research and innovation, aims to encourage the delivery of cost-effective, evidence-based care that will improve outcomes for cancer patients, consistent with the aims of the World Cancer Declaration, which calls for significant improvement in global cancer survival rates by 2020 [50, 51]. In the European context, innovation as a key driver of improved cancer care complements the vision of the European Partnership for Action Against Cancer, which is committed to reducing the cancer burden by 15% by 2020, and is consistent with the Innovation Union and the Europe 2020 growth strategy of the European Union. It also provides an impetus to the Council of the European Union’s conclusions on “Reducing the Burden of Cancer” [52].

The European Cancer Patient’s Bill of Rights builds on other cancer-focused initiatives, particularly the Charter of Paris [51] but also the World Cancer Declaration of the Union for International Cancer Control [50], the European Code Against Cancer [53], and the “Stop Cancer Now!” campaign, launched by the European School of Oncology following the World Oncology Forum in Lugano, Switzerland [54]. The ECC’s commitment to establishing a charter for cancer patients, achieved through a vibrant and equal partnership among health care professionals, cancer patients, and their representatives and bolstered by robust health economic principles, aims to deliver a unique “Wealth is Health” initiative that promotes optimal cancer care and research, reduces loss of productive life-years, enables active survivorship and rehabilitation, and increases health care innovation, thus leveraging wider benefits for European citizens and societies. The principles of equity and transparency will underpin all aspects of the ECC and the European Cancer Patient’s Bill of Rights, culminating in the translation of health and societal benefit directly to the European citizen.

Conclusion

Cancer is placing an increasing health, economic, and societal burden on Europe’s citizens. The current disparities between European nations at all stages of the cancer patient’s journey are no longer acceptable. In the context of the World Cancer Declaration and the Europe 2020 strategy, we must respond urgently to this pressing challenge or face a major epidemic that will have a significant impact on both the wealth and the health of the European citizen. The ECC is actively engaging with all relevant stakeholders to deliver its vision and partnering with patients and advocacy groups, learned societies, cancer registries, industry, governmental agencies and health care payers, the European Commission, the European Medicines Agency, health technology assessment agencies, cancer charities, and other key stakeholders. The principle of inclusivity will be actively pursued, ensuring that the European citizen receives the maximum support and benefit from this initiative. The vibrant engagement of health care professionals and patients can help achieve progress in innovation, research, and care to deliver improved outcomes for cancer patients in Europe. The European Cancer Patient’s Bill of Rights is a key early output, representing an important first step in a strategy to deliver measurable benefits for European society as a whole. Launching this bill of rights in the European Parliament on World Cancer Day, in partnership with European cancer patient organizations and Members of the European Parliament Against Cancer (MEPs Against Cancer), represents a clear commitment to promulgating and implementing this catalyst for change for European citizens. If successful, it may also provide a model for developing collaborative patient-centered approaches to deliver equitable cancer care in other regions throughout the world.

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Society for Translational Oncology (STO) for its stewardship of the European Cancer Concord initiative. STO gratefully acknowledges unrestricted educational support from Sanofi Oncology, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation, Irish Cancer Society, Saatchi and Saatchi Science, and Publicis Healthcare Communications Group. The creation, composition, and submission of this manuscript were exclusively performed by the authors, who are solely responsible for its content. The authors dedicate this manuscript and the European Cancer Patient’s Bill of Rights initiative to Prof. Donal Hollywood, who passed away in 2013 due to cancer.

Footnotes

See the related commentary by Christopher R. Friese and John Z. Ayanian on page 225 of this issue.

Author Contributions

Author contributions available online.

Conception and design: Patrick G. Johnston, Peter W. Johnson, Michéle Barzach, Gerlind Bode, Sarper Diler, Denis Horgan, Peter Kapitein, Joan Kelly, Roger Wilson, Mark Lawler, Thierry Le Chevalier, Martin J. Murphy, Jr., Ian Banks, Pierfranco Conte, Francesco de Lorenzo, François Meunier, H.M. Pinedo, Peter Selby, Jean-Pierre Armand, Mariano Barbacid, Jonas Bergh, David A. Cameron, Filippo de Braud, Aimery de Gramont, Volker Diehl, Sema Erdem, John M. Fitzpatrick, Jan Geissler, Donal Hollywood, Liselotte Højgaard, Jacek Jassem, Sandra Kloezen, Carlo La Vecchia, Bob Löwenberg, Kathy Oliver, Richard Sullivan, Josep Tabernero, Cornelis J. van de Velde, Nils Wilking, Christoph Zielinski, Harald Zur Hausen

Manuscript writing: Patrick G. Johnston, Gerlind Bode, Denis Horgan, Mark Lawler, Thierry Le Chevalier, Martin J. Murphy, Jr., Ian Banks, Pierfranco Conte, Francesco de Lorenzo, François Meunier, H.M. Pinedo, Peter Selby, Volker Diehl, Sema Erdem, John M. Fitzpatrick, Jan Geissler, Liselotte Højgaard, Jacek Jassem, Carlo La Vecchia, Bob Löwenberg, Kathy Oliver, Richard Sullivan, Josep Tabernero, Cornelis J. van de Velde, Nils Wilking, Christoph Zielinski

Final approval of manuscript: Patrick G. Johnston, Peter W. Johnson, Michéle Barzach, Gerlind Bode, Sarper Diler, Denis Horgan, Peter Kapitein, Joan Kelly, Roger Wilson, Mark Lawler, Thierry Le Chevalier, Martin J. Murphy, Jr., Ian Banks, Pierfranco Conte, Francesco de Lorenzo, François Meunier, H.M. Pinedo, Peter Selby, Jean-Pierre Armand, Mariano Barbacid, Jonas Bergh, David A. Cameron, Filippo de Braud, Aimery de Gramont, Volker Diehl, Sema Erdem, John M. Fitzpatrick, Jan Geissler, Donal Hollywood, Liselotte Højgaard, Jacek Jassem

Disclosures

Peter Johnson: Millenium Takeda, Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, Boehringer Ingelheim (H); Johnson & Johnson (RF); Roger Wilson: Sarcoma UK, British Sarcoma Group (C/A); Novartis, Amgen, GSK (H); H.M. Pinedo: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Spectrum Pharmaceuticals (C/A); Jonas Bergh: Karolinska Institutet and University Hospital, Amgen, Bayer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis (RF); Filippo de Braud: Novartis, Roche, Boehringer Ingelheim, Nerviano Medical Sciences (C/A), Novartis, Roche, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Servier, Celgene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Philogen (RF); Aimery de Gramont: Sanofi, Roche (C/A); Jan Geissler: European Patients' Academy on Therapeutic Innovation (E); Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Ariad, Amgen (RF); Kathy Oliver: Novartis, Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline (C/A, RF, H), Roche, Novocure, Celldex, Antisense, Merck, Accuray (RF); Richard Sullivan: Esai, Pfizer (all funds allocated to the Institute for Cancer Policy) (H); Harald Zur Hausen: Oryx, Munid (RF). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, et al. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coleman MP, Quaresma M, Berrino F, et al. Cancer survival in five continents: A worldwide population-based study (CONCORD) Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:730–756. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70179-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giovino GA, Mirza SA, Samet JM, et al. Tobacco use in 3 billion individuals from 16 countries: An analysis of nationally representative cross-sectional household surveys. Lancet. 2012;380:668–679. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61085-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soerjomataram I, Lortet-Tieulent J, Parkin DM, et al. Global burden of cancer in 2008: A systematic analysis of disability-adjusted life-years in 12 world regions. Lancet. 2012;380:1840–1850. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60919-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Cancer Society The global economic cost of cancer. Available at http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@internationalaffairs/documents/document/acspc-026203.pdf.

- 6.Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: Estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1374–1403. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karim-Kos HE, de Vries E, Soerjomataram I, et al. Recent trends of cancer in Europe: A combined approach of incidence, survival and mortality for 17 cancer sites since the 1990s. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:1345–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rechel B, Grundy E, Robine JM, et al. Ageing in the European Union. Lancet. 2013;381:1312–1322. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62087-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe European health report 2012: Charting the way to well-being. Available at http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/184161/The-European-Health-Report-2012,-FULL-REPORT-w-cover.pdf.

- 10.de Lorenzo F, Haylock P. Preface. Cancer. 2013;119(suppl 11):2089–2093. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnston PG, Pinedo HM. The high tide of cancer research in Europe. The Oncologist. 2011;16:539–542. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malvezzi M, Bertuccio P, Levi F, et al. European cancer mortality predictions for the year 2013. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:792–800. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.zur Hausen H. Papillomaviruses and cancer: From basic studies to clinical application. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:342–350. doi: 10.1038/nrc798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michels KB, zur Hausen H. HPV vaccine for all. Lancet. 2009;374:268–270. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61247-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khayat D. Alexandria, VA: American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2013. National Cancer Plans; pp. 242–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Cancer Research Institute Welcome to the NCRI. Available at http://www.ncri.org.uk/

- 17.Meunier F, Lawler M, Pinedo HM. Commentary: Fifty years of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment Of Cancer (EORTC)—making the difference for the European oncology community. The Oncologist. 2012;17:e6–e7. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cardoso F, Piccart-Gebhart M, Van’t Veer L, et al. The MINDACT trial: The first prospective clinical validation of a genomic tool. Mol Oncol. 2007;1:246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wils J. The establishment of a large collaborative trial programme in the adjuvant treatment of colon cancer. Br J Cancer. 1998;77(suppl 2):23–28. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mackenbach JP, Karanikolos M, McKee M. The unequal health of Europeans: Successes and failures of policies. Lancet. 2013;381:1125–1134. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Autier P, Boniol M, La Vecchia C, et al. Disparities in breast cancer mortality trends between 30 European countries: Retrospective trend analysis of WHO mortality database. BMJ. 2010;341:c3620. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sant M, Minicozzi P, Allemani C, et al. Regional inequalities in cancer care persist in Italy and can influence survival. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;36:541–547. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van der Heyden JH, Schaap MM, Kunst AE, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in lung cancer mortality in 16 European populations. Lung Cancer. 2009;63:322–330. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woods LM, Rachet B, Coleman MP. Origins of socio-economic inequalities in cancer survival: A review. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:5–19. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quaglia A, Tavilla A, Shack L, et al. The cancer survival gap between elderly and middle-aged patients in Europe is widening. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:1006–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Angelis R, Sant M, Coleman MP, et al. Cancer survival in Europe 1999—2007 by country and age: Results of EUROCARE-5—a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:23–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70546-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Experts in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia The price of drugs for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a reflection of the unsustainable prices of cancer drugs: From the perspective of a large group of CML experts. Blood. 2013;121:4439–4442. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-490003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.European Commission Impact assessment report on the revision of the “Clinical Trials Directive” 2001/20/EC. Available at http://ec.europa.eu/health/files/clinicaltrials/2012_07/impact_assessment_part1_en.pdf.

- 29.European Commission Medicinal products for human use. Clinical trials: Revision of the clinical trials directive. Available at http://ec.europa.eu/health/human-use/clinical-trials/index_en.htm#rlctd.

- 30.EUnetHTA. Available at http://www.eunethta.eu/

- 31.Purushotham A, Cornwell J, Burton C, et al. What really matters in cancer?: Putting people back into the heart of cancer policy. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1669–1672. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith TJ, Hillner BE. Bending the cost curve in cancer care. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2060–2065. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1013826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schnipper LE, Smith TJ, Raghavan D, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology identifies five key opportunities to improve care and reduce costs: The top five list for oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1715–1724. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.8375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Institute of Medicine Delivering affordable cancer care in the 21st century – workshop summary. Available at http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2013/Delivering-Affordable-Cancer-Care-in-the-21st-Century.aspx. [PubMed]

- 35.U.S. Census Bureau Population Division Interim projections consistent with census 2000 (released March 2004) Available at http://www.census.gov/population/www/projections/usinterimproj/. Accessed August 21, 2013.

- 36.National Research Council . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013. Delivering high-quality cancer care: Charting a new course for a system in crisis. Available at http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=18359. Accessed September 11, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sullivan R, Peppercorn J, Sikora K, et al. Delivering affordable cancer care in high-income countries. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:933–980. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70141-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilking N, Jönsson B, Högberg D, et al. Comparator report on patient access to cancer drugs in Europe. Available at http://www.comparatorreports.se/Comparator%20report%20on%20patient%20access%20to%20cancer%20drugs%20in%20Europe%2015%20feb%2009.pdf.

- 39.Karanikolos M, Mladovsky P, Cylus J, et al. Financial crisis, austerity, and health in Europe. Lancet. 2013;381:1323–1331. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luengo-Fernandez R, Leal J, Gray A, et al. Economic burden of cancer across the European Union: A population-based cost analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1165–1174. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70442-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilking N, Jonsson B. Cancer and economics: With a special focus on cancer drugs. Oncol News. 2011;6:17–19. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khayat D. Innovative cancer therapies: Putting costs into context. Cancer. 2012;118:2367–2371. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilking N, Kasteng F. A review of breast cancer care and outcomes in 18 countries in Europe, Asia and South America. Available at http://www.comparatorreports.se/A_review_of_breast_cancer_care_and_outcomes_26Oct2009.pdf.

- 44.Lichtenberg FR. Despite steep costs, payments for new cancer drugs make economic sense. Nat Med. 2011;17:244. doi: 10.1038/nm0311-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luce BR, Mauskopf J, Sloan FA, et al. The return on investment in health care: From 1980 to 2000. Value Health. 2006;9:146–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2006.00095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soria JC, Blay JY, Spano JP, et al. Added value of molecular targeted agents in oncology. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1703–1716. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nowak F, Soria JC, Calvo F. Tumour molecular profiling for deciding therapy-the French initiative. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9:479–486. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kantarjian HM, Fojo T, Mathisen M, et al. Cancer drugs in the United States: Justum Pretium—the just price. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3600–3604. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pfister DG. The just price of cancer drugs and the growing cost of cancer care: Oncologists need to be part of the solution. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3487–3489. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.3466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kerr D. World summit against cancer for the new millennium: The Charter of Paris. Ann Oncol. 2000;11:253–254. doi: 10.1023/a:1008392731320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Union for International Cancer Control World Cancer Declaration. Available at http://www.uicc.org/world-cancer-declaration.

- 52.Slovensko predsedstvo EU 2008. Available at http://www.eu2008.si/en/News_and_Documents/Council_Conclusions/June/0609_EPSCO-cancer.pdf.

- 53.Association of European Cancer Leagues What is the European code against cancer? Available at http://www.cancercode.eu/

- 54.Stop cancer now! Lancet. 2013;381:426–427. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.