Abstract

Postmenopausal vaginal atrophy, resulting from decreased estrogen production, frequently requires treatment. Estrogen preparations provide the most effective treatment; local application is preferred to systemic drugs when treating only vaginal symptoms. As local estrogen therapies have comparable efficacy, this study aimed to understand treatment practices, assess experiences with different forms of local estrogen-delivering applicators, and evaluate satisfaction. Women who were US residents aged ≥18 years, menopausal (no spontaneous menstrual period for ≥1 year or with a double oophorectomy), and receiving local estrogen therapy for 1–6 months (vaginal cream [supplied with a reusable applicator] or vaginal tablets [supplied with a single-use/disposable applicator]), completed an online questionnaire. Data from 200 women (100 cream users and 100 tablet users; mean therapy duration 3.48 months) showed that most stored medication in the room in which it was applied (88%) and applied it at bedtime (71%), a procedure for which cream users required, on average, more than twice the time of tablet users (5.08 minutes versus 2.48 minutes). Many cream users applied larger-than-prescribed amounts of cream, attempting to achieve greater efficacy (42%), or lower-than-recommended doses (45%), most frequently to avoid messiness (33%) or leakage (30%). More tablet users (69%) than cream users (14%) were “extremely satisfied” with their applicator. Postmenopausal women using local estrogen therapy were generally more satisfied with the application of vaginal tablets than cream. Patient satisfaction may help to facilitate accurate dosing. Positive perceptions of medication will help to optimize treatment, which, although not assessed in this study, is likely, in turn, to improve vaginal health.

Keywords: local estrogen therapy, menopause, patient satisfaction, survey, vaginal atrophy

Introduction

Decreased estrogen production after menopause is frequently associated with vaginal atrophy.1,2 Anatomic and physiologic changes in the genitourinary tract arising from a hypoestrogenic state include decreased vaginal vascularization, reduced vaginal lubrication, and thinning of the vaginal epithelium, together with proliferation of connective tissue, fragmentation of elastin and hyalinization of collagen.3,4 With fewer vaginal epithelial cells being exfoliated, and those that are having a lower glycogen content, less glycogen is available for hydrolysis to glucose and subsequent conversion into lactic acid by lactobacilli. Consequently, vaginal pH increases, and loss of lactobacilli allows opportunistic colonization by pathogenic bacteria; this can produce infection.3,4 Other symptoms of vaginal atrophy include vaginal dryness, which is often the first reported symptom,5 as well as vaginal discomfort, itching, burning, pain, and dyspareunia.6,7 The health of the vaginal and urinary tracts are strongly interrelated;2 urinary symptoms, such as urinary urgency, nocturia, and dysuria, can also occur, and are more often reported in postmenopausal women when they have vaginal atrophy.8

As many as half of postmenopausal women may experience symptoms related to vaginal atrophy,2,9 negatively affecting both sexual function10,11 and overall quality of life.12,13 Vaginal atrophy is progressive and frequently requires treatment.2 Estrogen therapy is the most effective treatment,14 and the 2013 position statement of the North American Menopause Society considers that estrogen delivered locally is preferred to systemic drugs when vaginal symptoms are the only complaint.15 Response to estrogen therapy is rapid, but it is recommended that this be started early, before atrophic changes become difficult to treat, and that it be maintained to provide continued benefit.2

Local estrogen therapy can take a variety of forms. Vaginal creams are commonly used, although some users may consider these messy.15 Tablets placed deep into the vagina using a disposable applicator16 are an alternative option. Clinical trial data suggest that, overall, available products have comparable efficacy.15 Choice of therapy depends on symptom severity, the effectiveness and safety of therapy for individual patients, and patients’ preferences.15 Therefore, the objectives of the current study were to understand postmenopausal women’s practices regarding local estrogen therapy, assess their experiences with different forms of applicator device, and evaluate satisfaction.

Methods

Study design

A quantitative online survey was conducted in March 2013 by an independent market research organization (Boyd Associates, Inc., NJ, USA). The survey, which required approximately 15 minutes for completion, comprised 39 questions and included the following topics: vaginal symptoms; therapy selection; storage of vaginal medication; application time of day; time taken to carry out the application; choice of position during application; device disposal; incidence and reasons for overdosing/underdosing; and perceptions relating to treatment application.

As the study involved a survey of attitudes and behaviors, with no therapeutic intervention, formal medical ethics approval was not sought.

Participants

Women were recruited from an established online market research panel: uSamp (United Sample Inc., Encino, CA, USA). This is a global panel of 12 million individuals willing to participate in online surveys, which can provide samples of respondents with appropriate health or medical profiles.

To be eligible for study participation, women were required to be US residents ≥18 years of age, menopausal (ie, not presenting with a spontaneous menstrual period for ≥1 year, or having had a double oophorectomy) and in receipt of local estrogen therapy (either vaginal cream or tablets) for atrophic vaginitis, having been treated for 1–6 months prior to the survey. Individuals who were themselves, or had a household member employed as, a health care provider were excluded from study participation.

Women who were likely to meet the selection criteria were identified from the uSamp online panel, and email invitations were sent to these potential respondents. Each email invitation provided a link to the online questionnaire and included an individual password to access the study website.

A sample of 200 respondents was chosen to allow for statistical significance testing. When the first 100 cream users and the first 100 tablet users who met the selection criteria were identified, recruitment was stopped.

Analyses

Data from the 200 study participants were analyzed. Descriptive statistics were generated, including percentage frequencies and means (including means from Likert scales for questions involving rating opinions). Where appropriate, statistical significance was assessed using Student’s t-tests and 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Survey participants

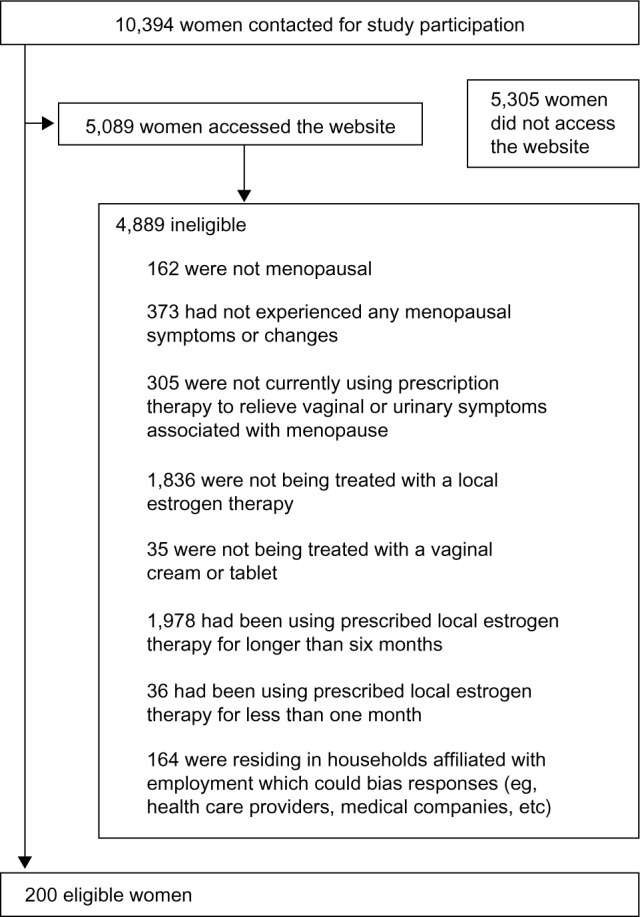

A total of 10,394 women were identified from the uSamp online panel as being likely to meet the selection criteria; of these, 5,089 had accessed the study website before recruitment was stopped at 200 participants (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics of the 200 women selected for the analysis are shown in Table 1. There were no clinically significant differences between cream users and tablet users with regard to age, ethnicity, level of education, marital status, or status of sexual activity. The mean duration of vaginal therapy was 3.41 months for cream users and 3.55 months for tablet users (3.48 months overall).

Figure 1.

Recruitment of the survey participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the survey participants

| Variable | Cream users n=100 |

Tablet users n=100 |

Total n=200 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, n (%) | |||

| 38–44 | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.0) | 3 (1.5) |

| 45–50 | 6 (6.0) | 9 (9.0) | 15 (7.5) |

| 51–55 | 34 (34.0) | 27 (27.0) | 61 (30.5) |

| 56–60 | 32 (32.0) | 33 (33.0) | 65 (32.5) |

| 61–65 | 22 (22.0) | 24 (24.0) | 46 (23.0) |

| 66–70 | 3 (3.0) | 3 (3.0) | 6 (3.0) |

| 71–76 | 3 (3.0) | 1 (1.0) | 4 (2.0) |

| Mean ± standard deviation age, years | 57.63 ± 5.57 | 57.07 ± 5.90 | 57.35 ± 5.74 |

| Ethnicity, n (%)* | |||

| Caucasian | 89 (89.0) | 94 (94.0) | 183 (91.5) |

| African American | 4 (4.0) | 2 (2.0) | 6 (3.0) |

| Hispanic | 5 (5.0) | 2 (2.0) | 7 (3.5) |

| Asian | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) |

| Other | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (1.0) |

| Level of education, n (%)* | |||

| Less than high school diploma or GED | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) |

| High school diploma or GED | 19 (19.0) | 13 (13.0) | 32 (16.0) |

| Some college education | 31 (31.0) | 30 (30.0) | 61 (30.5) |

| 2-year college graduate | 14 (14.0) | 15 (15.0) | 29 (14.5) |

| 4-year college graduate | 20 (20.0) | 24 (24.0) | 44 (22.0) |

| Postgraduate degree | 14 (14.0) | 18 (18.0) | 32 (16.0) |

| Marital status, n (%)* | |||

| Married | 76 (76.0) | 75 (75.0) | 151 (75.5) |

| Divorced | 16 (16.0) | 17 (17.0) | 33 (16.5) |

| Widowed | 2 (2.0) | 2 (2.0) | 4 (2.0) |

| Never married | 5 (5.0) | 5 (5.0) | 10 (5.0) |

| Status of sexual activity, n (%)*,# | |||

| Sexually active | 64 (64.0) | 70 (70.0) | 134 (67.0) |

| Sexually inactive | 31 (31.0) | 21 (21.0) | 52 (26.0) |

Notes:

Data not available for every survey participant.

Self-defined in response to the question “Do you currently consider yourself to be sexually active or inactive?”

Abbreviation: GED, General Educational Development test.

Symptoms of vaginal atrophy and therapy selection

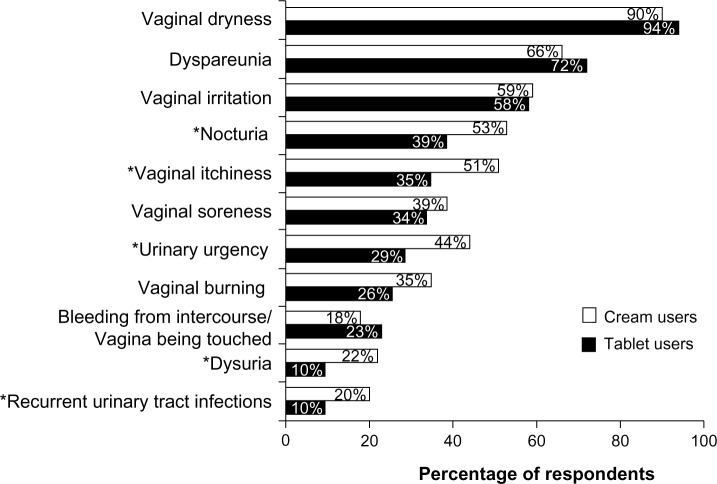

Nearly all respondents had experienced vaginal dryness since menopause (cream users, 90%; tablet users, 94%), with a large majority also indicating that they had experienced dyspareunia and vaginal irritation (Figure 2). Compared with tablet users, statistically significantly higher rates of nocturia, vaginal itchiness, urinary urgency, dysuria, and recurrent urinary tract infections were reported by cream users.

Figure 2.

Symptoms of vaginal atrophy after menopause reported by the survey participants.

Note: *P<0.05 for cream users versus tablet users.

In most instances, the type of medication used to treat vaginal atrophy had been selected by the health care provider rather than the respondent (cream users, 64%; tablet users, 83%).

Therapy administration practice

Most of the respondents (88%) reported storing their vaginal medication in the same room as that in which it was applied. This was most often a personal bathroom (ie, a bathroom used only by the woman and her partner, and not by other family members or guests; 55%) or a bedroom (30%). Most women (71%) applied their vaginal medication at bedtime, with early morning application reported less often (16%).

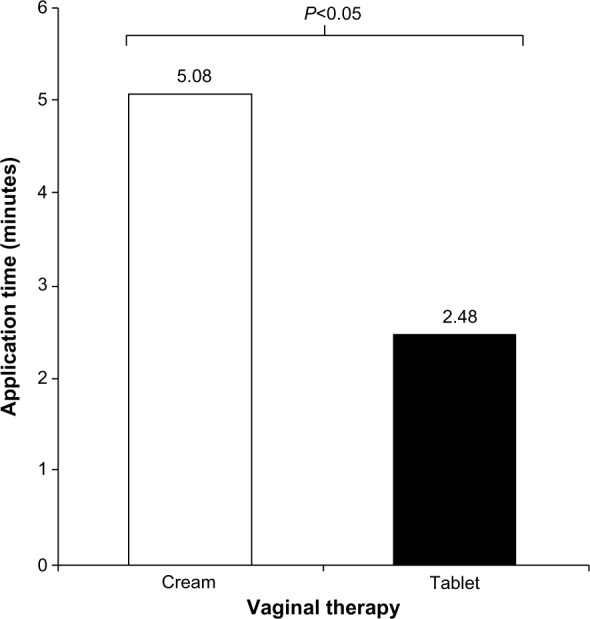

Cream users needed, on average, more than twice the time reported by tablet users to apply their vaginal medication (including getting the applicator, applying the cream, and then finishing/cleaning up and returning the applicator to storage) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Mean application time for vaginal therapy.

The positions most commonly adopted for applying the product were standing with a foot raised on the edge of the tub or toilet (cream users, 24%; tablet users, 33%), or sitting on the edge of the toilet (31% and 19%, respectively).

Of 134 sexually active women, 39% applied their medication 1 day before intercourse (cream users 33%; tablet users 44%), whereas 37% indicated that application of the medication had no effect on sexual intercourse (cream users, 34%; tablet users, 39%).

Applicator devices are provided with the local estrogen therapies evaluated in this study – reusable applicators with cream (Premarin® vaginal cream, Pfizer, Inc., New York, NY, USA; Estrace® vaginal cream, Warner Chilcott, Rockaway, NJ, USA) and single-use/disposable applicators with tablets (Vagifem® 10 mcg, Novo Nordisk Inc., Plainsboro, NJ, USA). Of the women applying vaginal cream, 96% reported cleaning the reusable device after insertion, mostly with regular/mild soap or cleanser (58%). When washing the applicator, 61% used some form of tool at least occasionally, while 23% always did so. Women were questioned about the benefit to cream users of being able to purchase (online or in store) single-use applicators, and thus eliminate the need for washing and storage; 79% of the respondents not employing single-use applicators indicated that these might be beneficial, with 44% having considered trying to obtain single-use applicators, rather than applying their medication with washable, reusable devices.

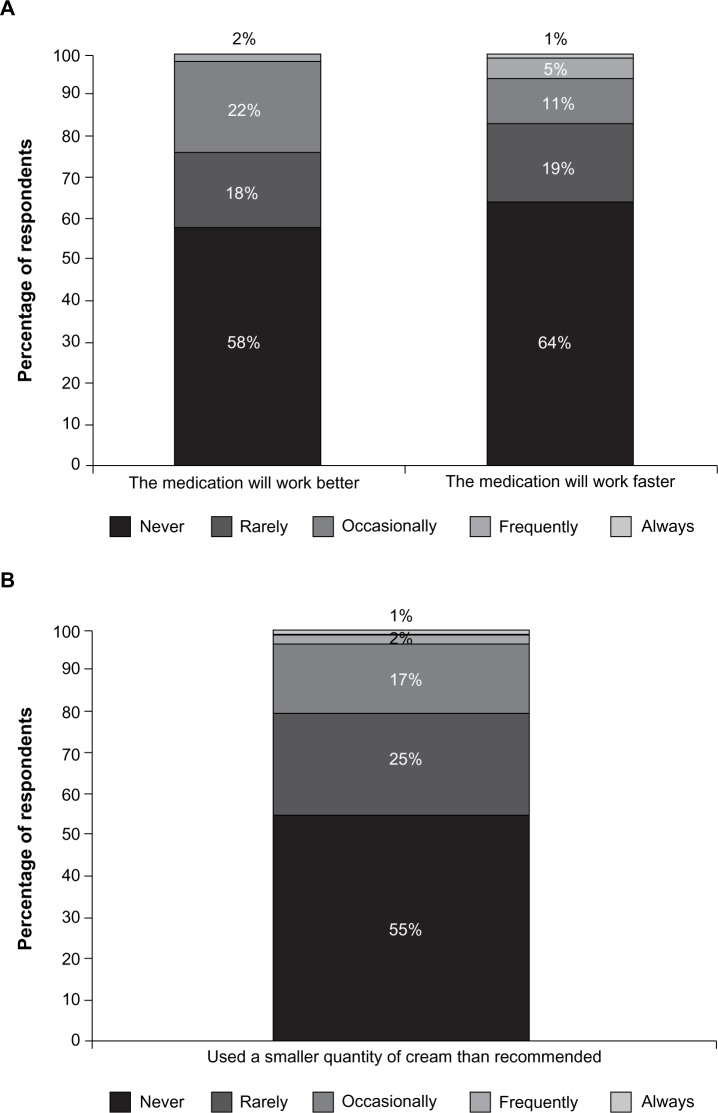

Fifty-eight percent of users agreed that it was difficult to place the correct amount of cream into a reusable device, and 77% found filling them to be confusing. Furthermore, many cream users were deliberately not adhering to their dosing instructions, intentionally overdosing or underdosing. They reported using larger amounts of cream than prescribed, in attempts to achieve greater efficacy (42%) or a faster therapeutic response (36%) (Figure 4a). Lower-than-recommended doses were used by 45% of users, albeit rarely in some cases (Figure 4b), most frequently to avoid messiness (33%) or leakage (30%).

Figure 4.

Percentages of women who overdose (A) or underdose (B) when applying their cream medication.

Perceptions

Substantial proportions of cream users reported delaying or failing to use vaginal medication because of not having the time needed for the application (49%, versus 19% for tablet users), issues of hygiene and cleanliness (47%, versus 12% for tablet users), messiness (67%, versus 17% for tablet users), or “the application process being generally unpleasant” (51%, versus 15% for tablet users), with all of these paired comparisons being statistically significantly different (P<0.05). Concerns relating to overdosing (applying a greater amount of vaginal medication than directed) were held by 64% of cream users compared with 10% of tablet users. When rating this concern on a 7-point Likert scale in which 1 represented “not concerned at all” and 7 represented “extremely concerned”, mean scores of 2.54 and 1.18, respectively, were apparent (P<0.05 for the difference between these scores). Concerns relating to underdosing (the applicator not providing enough medication) were held by 76% of cream users compared with 17% of tablet users (mean scores of 3.30 and 1.38, respectively, based on a 7-point Likert scale; P<0.05 for the difference between these scores).

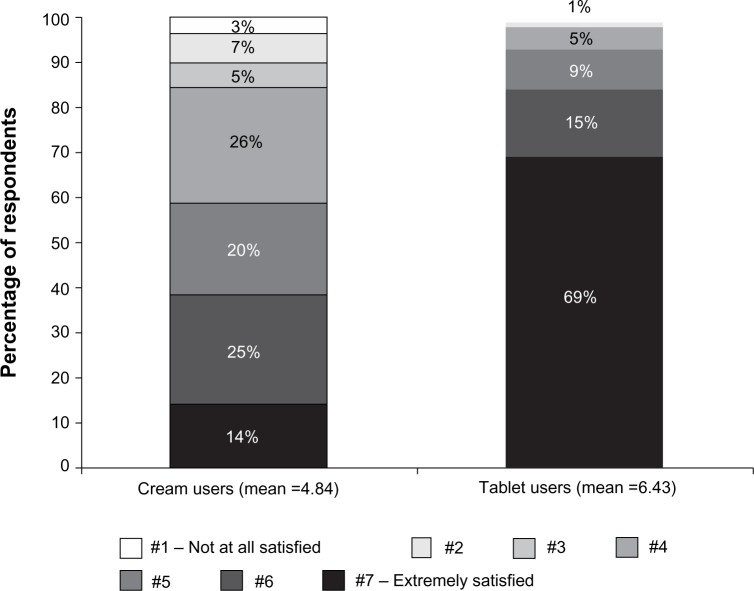

Other questions also showed tablet users to have a more positive attitude toward treatment application. For instance, privacy and discreetness was rated as excellent by 35% of tablet users compared with 9% of cream users (mean scores of 5.29 and 4.42 on a 7-point Likert scale, respectively; P<0.05 for the difference between these scores). Considering the descriptor “easy to use”, 80% of tablet users rated this at the highest value (ie, “extremely”) on a 7-point Likert scale, compared with 17% of cream users (mean scores of 6.63 and 5.17, respectively; P<0.05 for the difference between these scores). The overall perception of the applicator was rated as “excellent” by 68% of tablet users and 11% of cream users (mean 5-point Likert scale scores of scores of 4.64 and 3.59, respectively; P<0.05 for the difference between these scores). More tablet users than cream users reported being “extremely satisfied” (69% versus 14%, respectively; mean overall satisfaction with applicator, 6.43 versus 4.84 on a 7-point Likert scale; P<0.05 for the difference between these scores) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Overall satisfaction with treatment applicator.

Notes: Means are statistically significant. P-value for difference in means between tablet user group and cream user group is <0.05. A 7-point Likert Scale was used to evaluate patient satisfaction.

Discussion

The results of this survey suggest that postmenopausal women whose atrophic vaginitis is being treated with vaginal tablets rather than vaginal cream are more satisfied with the administration process and device. Single-use applicators were rated more favorably than reusable devices. Indeed, many women who did not use disposable applicators speculated that that these could be beneficial, and almost half had sought them out.

These findings are consistent with other previously published results. For instance, a recent online survey of 423 women from Sweden showed that respondents preferred local estrogen therapy delivered via disposable applicators with small tablets over dosing syringes with vaginal cream.17 Quantification of responses, using discrete choice methodology, suggested that women were willing to pay €66.58 (approximately $90) more per month to receive treatment involving a disposable applicator with a small tablet rather than a dosing syringe with cream, and to avoid leakage.17 In relation to this – and because the current study was performed in the United States – it is appropriate to note that previous US data have shown willingness to pay to be affected by income.18

In another recently performed online survey, which considered data from 73 postmenopausal women from the United States who had switched to vaginal tablets from other local estrogen preparations, respondents also exhibited a preference for vaginal tablets over vaginal creams; this was mainly a consequence of formulation and application, with tablets being perceived as efficacious, convenient, and neat to apply.19 Such results are consistent with an earlier randomized study involving 159 postmenopausal women from Canada, in which significantly more users of vaginal tablets than vaginal cream rated application as “easy” and “comfortable”, and the medication as “very acceptable”.20

Patients’ perceptions of the drugs they are receiving are likely to have implications with regard to dosing and compliance. In the current study, around half of cream users reported using larger amounts than recommended to improve effectiveness, or smaller amounts to reduce messiness and leakage. Substantial proportions of cream users described delaying or failing to use their medication as a consequence of the length of time needed for the application, issues of hygiene and cleanliness, or considering application to be unpleasant. These results are in line with other published data. In the US study by Minkin et al,19 women’s favorable attitudes towards vaginal tablets rather than vaginal cream were borne out by tablet users reporting greater compliance and a longer duration of therapy. In the randomized study involving women from Canada, women’s positive views of vaginal tablets over vaginal cream appeared to translate into lower study withdrawal rates (10% versus 32%).20

Results from “real-world” clinical practice provide further evidence that women treated with vaginal tablets may receive more reliable therapy than those who use vaginal cream. An analysis of 13,074 US women identified from commercial health plans showed that newly treated individuals initiating vaginal tablets were more likely to continue therapy for longer periods, and exhibited greater medication adherence, than did women starting treatment with vaginal cream.21

With postmenopausal vaginal atrophy often requiring long-term therapy, use of a delivery system that facilitates this may improve clinical outcomes.21 All local estrogen therapies have similar efficacy,22 although overall user satisfaction may determine whether accurate dosing is received and medication is adhered to. Consequently treatment may be optimized by taking into account patients’ preferences and perceptions.

The limitations of any online study apply to the results obtained from the current survey, in that respondents were limited to women who had Internet access. However, it could be argued that this limitation is unlikely to have substantially confounded the results, particularly given that findings from this study, including the pattern of symptoms reported and the therapeutic preferences for medication used to treat them, are in line with published data from other cohorts of postmenopausal women in the United States.19,21,23

In conclusion, postmenopausal women who use local estrogen therapy to treat atrophic vaginitis are generally more satisfied with the application of vaginal tablets than vaginal cream. These findings should inform health care professionals about women’s experiences with different therapeutic formulations and methods of application. With all local estrogen therapies having similar efficacy, overall patient satisfaction may help to facilitate accurate dosing. Positive perceptions of medication will help to optimize treatment, which, in turn, is likely to improve vaginal health.

Acknowledgments

The survey was commissioned and funded by Novo Nordisk Inc. Medical writing support (funded by Novo Nordisk Inc.) was provided by Dan Booth and Andy Lockley of Bioscript Medical Ltd.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Mary Jane Minkin consults for Novo Nordisk Inc., Noven Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Shionogi and Enzymatic Therapy. Ricardo Maamari is Medical Director, Hormone Therapy at Novo Nordisk Inc. Suzanne Reiter has been a speaker for Novo Nordisk Inc. and Red Hot Mamas. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Santoro N, Komi J. Prevalence and impact of vaginal symptoms among postmenopausal women. J Sex Med. 2009;6(8):2133–2142. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sturdee DW, Panay N, International Menopause Society Writing Group Recommendations for the management of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy. Climacteric. 2010;13(6):509–522. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2010.522875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stika CS. Atrophic vaginitis. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23(5):514–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2010.01354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mac Bride MB, Rhodes DJ, Shuster LT. Vulvovaginal atrophy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(1):87–94. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith RN, Studd JW. Recent advances in hormone replacement therapy. Br J Hosp Med. 1993;49(11):799–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Archer DF. Efficacy and tolerability of local estrogen therapy for urogenital atrophy. Menopause. 2010;17(1):194–203. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181a95581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bachmann GA, Nevadunsky NS. Diagnosis and treatment of atrophic vaginitis. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(10):3090–3096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pastore LM, Carter RA, Hulka BS, Wells E. Self-reported urogenital symptoms in postmenopausal women: Women’s Health Initiative. Maturitas. 2004;49(4):292–303. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parish SJ, Nappi RE, Krychman ML, et al. Impact of vulvovaginal health on postmenopausal women: a review of surveys on symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy. Int J Womens Health. 2013;5:437–447. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S44579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levine KB, Williams RE, Hartmann KE. Vulvovaginal atrophy is strongly associated with female sexual dysfunction among sexually active postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2008;15(4 Pt 1):661–666. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31815a5168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nappi RE, Kingsberg S, Maamari R, Simon J. The CLOSER (CLarifying Vaginal Atrophy’s Impact On SEx and Relationships) survey: implications of vaginal discomfort in postmenopausal women and in male partners. J Sex Med. 2013;10(9):2232–2241. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nappi RE, Kokot-Kierepa M. Women’s voices in the menopause: results from an international survey on vaginal atrophy. Maturitas. 2010;67(3):233–238. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nappi RE, Kokot-Kierepa M. Vaginal Health: Insights, Views and Attitudes (VIVA) – results from an international survey. Climacteric. 2012;15(1):36–44. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2011.647840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.North American Menopause Society The 2012 hormone therapy position statement of: The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2012;19(3):257–271. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31824b970a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Management of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy: 2013 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2013;20(9):888–902. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e3182a122c2. quiz 903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Baghdadi O, Ewies AA. Topical estrogen therapy in the management of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy: an up-to-date overview. Climacteric. 2009;12(2):91–105. doi: 10.1080/13697130802585576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mattsson LA, Ericsson A, Bøgelund M, Maamari R. Women’s preferences toward attributes of local estrogen therapy for the treatment of vaginal atrophy. Maturitas. 2013;74:259–263. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barner JC, Branvold A. Patients’ willingness to pay for pharmacist-provided menopause and hormone replacement therapy consultations. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2005;1(1):77–100. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minkin MJ, Maamari R, Reiter S. Improved compliance and patient satisfaction with estradiol vaginal tablets in postmenopausal women previously treated with another local estrogen therapy. Int J Womens Health. 2013;5:133–139. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S41897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rioux JE, Devlin C, Gelfand MM, Steinberg WM, Hepburn DS. 17beta-estradiol vaginal tablet versus conjugated equine estrogen vaginal cream to relieve menopausal atrophic vaginitis. Menopause. 2000;7(3):156–161. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200007030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shulman LP, Portman DJ, Lee WC, et al. A retrospective managed care claims data analysis of medication adherence to vaginal estrogen therapy: implications for clinical practice. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17(4):569–578. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suckling J, Lethaby A, Kennedy R. Local oestrogen for vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD001500. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001500.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simon JA, Kokot-Kierepa M, Goldstein J, Nappi RE. Vaginal health in the United States: results from the Vaginal Health: Insights, Views and Attitudes survey. Menopause. 2013;20(10):1043–1048. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e318287342d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]