ABSTRACT

Despite the strong evidence base for the efficacy of physical activity in the management of type 2 diabetes, a limited number of physical activity interventions have been translated and evaluated in everyday practice. This systematic review aimed to report the findings of studies in which an intervention, containing physical activity promotion as a component, has been delivered within routine diabetes care. A comprehensive search was conducted for articles reporting process data relating to components of the RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and/or Maintenance) framework. Twelve studies met the selection criteria. Of the nine studies which measured physical activity as an outcome, eight reported an increase in physical activity levels, five of which were significant. Tailoring recruitment, resources and intervention delivery to the target population played a positive role, in addition to the use of external organisations and staff training. Many interventions were of short duration and lacked long-term follow-up data. Findings revealed limited and inconsistent reporting of useful process data.

KEYWORDS: Type 2 diabetes, Physical activity, Translation, Implementation, RE-AIM

BACKGROUND

Type 2 diabetes is a global health problem, with 387 million individuals (7.0 %) estimated to have the condition by the year 2030 [1]. It is therefore essential that effective management strategies are developed to reduce the growing burden of diabetes care.

Physical activity plays a crucial role in the management of type 2 diabetes, with extensive research reporting significant improvements in glycaemic control and diabetes-related complications [2–4]. Moderate increases in physical activity have been shown to reduce HbA1c, and improve insulin sensitivity, fat oxidation and lipid storage in muscle [2].

It is known that physical activity interventions based on a theoretical framework of behaviour change and tailored to the needs of individuals with type 2 diabetes are more effective than general physical activity promotion [5, 6]. A 2012 review and meta-analysis by Avery et al. [12] found behavioural interventions aimed at increasing physical activity in adults with type 2 diabetes produced significant increases in physical activity in addition to significant improvements in BMI and HbA1c. Guidelines now exist on the development of physical activity interventions for adults with type 2 diabetes [7, 8]. These guidelines recommend the use of a valid theoretical framework to structure interventions (i.e., Transtheoretical Model of Behaviour Change [9], Social Cognitive Theory [10] and Self-Efficacy Theory [11]) and use of behaviour change techniques such as goal setting, problem solving, self-monitoring and decisional balance.

Efficacy studies of physical activity interventions for adults with diabetes differ in their delivery methods (e.g., group education vs. individual counselling), setting (e.g., clinic vs. community), and duration/frequency of contact. Several reviews of the literature have explored the effectiveness of these factors with various findings. Significant improvements in glycaemic control are associated with interventions of greater than 6 months' duration [12] or where physical activity advice is combined with dietary advice [13]. Significant improvements in levels of physical activity have been demonstrated via the use of one-to-one physical activity consultations [7]. No further associations could be identified from the literature in terms of delivery method or frequency of contact. There is currently no consensus on the optimal method of delivery for physical activity interventions within routine diabetes care.

The majority of this research has been undertaken in a controlled research environment where publications mainly focus on the efficacy outcomes of the intervention [12]. Little is known about how these interventions work once implemented into everyday practice. The methodologies and findings of controlled research studies do not necessarily translate into the context of routine diabetes care. Information regarding the delivery of the intervention is essential to understand the processes of implementation and inform the development of future interventions.

The gap between 'what we know' and 'what we do' in health care has been documented by Estabrooks and Glasgow, who noted the lack of translational work being undertaken for clinical populations in relation to physical activity [14]. Various facilitators and barriers contribute to the complexity of intervention delivery within health care. Limited knowledge of departmental processes, staff turnover, staff commitment and funding has been reported as some of the factors associated with implementation within health care settings [15–17]. Progress is limited further by publications reporting minimal information on the development, delivery and evaluation of their interventions [16, 18, 19].

The Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework is a useful tool to facilitate the development, delivery and evaluation of health interventions [20]. RE-AIM has been frequently used to translate research into practice [21, 22] by promoting the development and evaluation of interventions based on the following elements:

Reach of the intervention for the intended target population.

Effectiveness of the intervention in achieving the desired positive outcomes.

Adoption of the intervention by target staff, venues and/or organisations.

Implementation, consistency and adaptation of the intervention protocol in practice.

Maintenance of intervention effects on individuals or settings over time.

The framework also encourages researchers to report the broader issues related to intervention delivery. The RE-AIM framework can therefore play an important role in further strengthening the evidence base for the effectiveness of physical activity interventions for adults with type 2 diabetes.

Physical activity interventions, when delivered for adults with type 2 diabetes in a clinical or community practice context, can be provided in various settings, by various professionals, using various modes of delivery [23, 24]. It is possible that all of these approaches result in positive, cost-effective outcomes, but without further evaluation obtaining funding and health service support for physical activity interventions will remain a challenge.

Objective

The aim of this systematic review was not to review efficacy trials of physical activity interventions for adults with diabetes but rather review studies reporting on delivery and implementation of interventions within everyday practice. This review provides important information to improve the translation and implementation of physical activity services within routine diabetes care.

This review adheres to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) guidelines for the reporting of systematic reviews [25].

METHODS

Data sources and searches

There is a low prevalence of articles reporting on issues related to delivery of health interventions; therefore, broad search criteria were applied to this review to capture as many relevant articles as possible. To ensure all relevant information was collected, multiple electronic databases were searched (Ovid [MEDLINE; EMBASE], EBSCO [SPORTDiscus; PsycINFO; PsycARTICLES], ProQuest [Australian Education Index; British Education Index; ERIC], ISI Web of Knowledge [Science Citation Index; Conference Proceedings Citation Index], IngentaConnect, Dissertations and Theses, Zetoc, GEOBASE, ScienceDirect, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Nexis, Informaworld, Google Scholar, NHS e-library, Centre for Review Dissemination, and Cambridge Scientific Abstracts), in addition to sources of grey literature (including health care and government resources, for example, National Institute for Clinical Excellence, National Institutes for Health) [final search conducted May 2012]. The reference lists of key articles and journals were also searched, and correspondence with key researchers in the field was undertaken to highlight any unpublished work in this area. Search terms were developed mainly for use in the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases (see Appendix 1, Table 4), and were modified as required for other sources. Key search terms included; physical activity, exercise, diabetes mellitus, health plan implementation, translation, and process evaluation.

Table 4.

Systematic review search strategy

| Search number | Search terms |

|---|---|

| 1 Base | ((diabetes OR diabetes mellitus type 2 OR type 2 diabetes) AND (physical activity OR motor activity OR exercise)) |

| 2 Base and Context | ((diabetes OR diabetes mellitus type 2 OR type 2 diabetes) AND (physical activity OR motor activity OR exercise) AND national health programs) |

| 3 Base and Context | ((diabetes OR diabetes mellitus type 2 OR type 2 diabetes) AND (physical activity OR motor activity OR exercise) AND national health service) |

| 4 Base and Context | ((diabetes OR diabetes mellitus type 2 OR type 2 diabetes) AND (physical activity OR motor activity OR exercise) AND real world) |

| 5 Base and Context | ((diabetes OR diabetes mellitus type 2 OR type 2 diabetes) AND (physical activity OR motor activity OR exercise) AND diabetes centre) |

| 6 Base and Context | ((diabetes OR diabetes mellitus type 2 OR type 2 diabetes) AND (physical activity OR motor activity OR exercise) AND diabetes clinic) |

| 7 Base and Implementation (mesh only) | ((diabetes OR diabetes mellitus type 2 OR type 2 diabetes) AND (physical activity OR motor activity OR exercise) AND health plan implementation) |

| 8 Base and Implementation (mesh only) | ((diabetes OR diabetes mellitus type 2 OR type 2 diabetes) AND (physical activity OR motor activity OR exercise) AND regional health planning) |

| 9 Base and Implementation (mesh only) | ((diabetes OR diabetes mellitus type 2 OR type 2 diabetes) AND (physical activity OR motor activity OR exercise) AND health promotion) |

| 10 Base and Implementation (mesh only) | ((diabetes OR diabetes mellitus type 2 OR type 2 diabetes) AND (physical activity OR motor activity OR exercise) AND health services needs and demands) |

| 11 Base and Implementation (mesh only) | ((diabetes OR diabetes mellitus type 2 OR type 2 diabetes) AND (physical activity OR motor activity OR exercise) AND health services research) |

| 12 Base and Implementation | ((diabetes OR diabetes mellitus type 2 OR type 2 diabetes) AND (physical activity OR motor activity OR exercise) AND (implement* OR translat* OR into practice OR polic* OR service implem* OR translational medicine OR diffusion of innovation OR information dissemination OR program development OR evidence based medicine OR delivery of health care)) |

| 13 Base and Study design (mesh only) | ((diabetes OR diabetes mellitus type 2 OR type 2 diabetes) AND (physical activity OR motor activity OR exercise) AND process assessment health care) |

| 14 Base and Study design | ((diabetes OR diabetes mellitus type 2 OR type 2 diabetes) AND (physical activity OR motor activity OR exercise) AND process evaluation) |

| 15 Base and Study design | ((diabetes OR diabetes mellitus type 2 OR type 2 diabetes) AND (physical activity OR motor activity OR exercise) AND (qualitative OR evaluation OR focus groups OR interviews OR surveys OR quasi-experiment* OR policy experiment OR longitudinal study OR cohort study OR impact OR review literature)) |

| 16 Additional search terms | Search 1… AND (view OR views OR opinion OR opinions) in the title |

The search protocol was discussed within the research team (LM, FMcM, AK and NM) and also reviewed by an experienced subject librarian. The full search was undertaken by one reviewer (LM). Two reviewers (LM, NM) then independently examined titles and abstracts to identify suitable publications matching the selection criteria. Relevant articles were obtained in full and further examined for relevance in the final review collection. The final collection of articles were reviewed and agreed upon within the research team. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion.

Study selection

All publications discussing the delivery of physical activity promotion for adults with type 2 diabetes were included in the review regardless of type of publication, year, language, study design, population, setting, length of follow up or geographical location. The search protocol was developed as follows using the PICOS framework for systematic reviews [26]:

Population: adults with type 2 diabetes (18+ years); regardless of time since diagnosis, culture and ethnicity, or current treatment regime (pharmacological vs. lifestyle management).

Intervention: interventions promoting physical activity behaviour change for the management of type 2 diabetes; delivered in individual or group settings. The intervention may focus on physical activity alone, or be included with multiple lifestyle change factors such as diet and diabetes self-management.

Context: interventions delivered in clinical or community practice settings; including primary care, diabetes clinics, community facilities or others.

Outcomes: based on the RE-AIM framework for health interventions, outcomes will include discussion of the reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation or maintenance of the intervention [20].

Study Design: publications which reported any element of the intervention delivery, including; process evaluations, qualitative studies, randomised controlled trials (RCTs), longitudinal studies and health service evaluation reports.

The systematic review focused on the management of adults with type 2 diabetes via physical activity behaviour change, therefore, the following exclusion criteria were applied:

Interventions for children or adolescents with diabetes

Physical activity and/or diabetes outcomes only, with no process evaluation reported

Implementation of interventions for the prevention of diabetes

Behaviour change programmes not addressing physical activity

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data relating to study characteristics, study quality and intervention delivery was extracted from each article and tabulated. Data extraction was performed by one reviewer (LM) and subsequently reviewed for agreement with one of three additional reviewers (AK, NM, FMcM). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion. All articles were analysed for quality of process data using the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre) guidelines for the appraisal of process evaluations [27]. Each article was given two final scores in relation to both the 'reliability' and 'usefulness' of the information provided. In the event of relevant information being missing, authors were contacted for further information and/or clarification of issues as required.

Data synthesis and analysis

The RE-AIM framework formed the main body of analysis, with information being extracted, collated and analysed in relation to the framework headings of Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance.

RESULTS

Articles

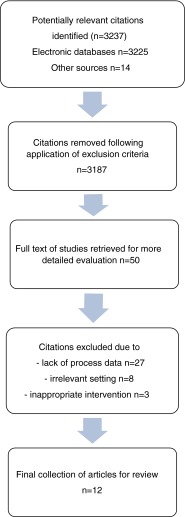

Figure 1 illustrates the stages of the systematic literature review. A total of 3,223 potentially relevant publications were found by electronic database searching, with a further 14 citations found by searching grey literature, the reference lists of key articles, and contacting key authors.

Fig 1.

Results of literature search

Following application of the exclusion criteria to titles and abstracts, and removal of duplicate publications, a total of 50 articles remained, for which the full text was obtained. The remaining collection was further analysed in-depth and a total of 12 articles, which reported detail relating to the process of intervention delivery, were included in the final analysis [28–39].

Interventions analysed for this review took place worldwide including Europe (17 %), Australia (17 %) and USA/Canada (67 %); for a variety of target populations including low socioeconomic areas (17 %), specific ethnic groups (25 %) and the general diabetes population (58 %).

Table 1 provides a collated summary of the 12 studies included in the review and highlights the wide variety of articles in relation to study design, setting, method of delivery and physical activity outcomes. Table 2 displays individual study characteristics for each of the 12 articles included in the review along with linking reference number. Individual characteristics related to the RE-AIM framework are presented in Table 3 for each of the included studies.

Table 1.

Collated summary of the 12 studies included in the review

| Descriptive Data (range) | Sample size Intervention duration Follow-up Contact time Contact frequency |

8–1,500 participants 1–12 months 1.5–18 months 1.5–24 hours 1–18 sessions |

|

| Study design | RCT Process Evaluation Longitudinal Descriptive report |

5 (41.7 %) 3 (25.0 %) 3 (25.0 %) 1 (8.3 %) |

|

| Main setting | Community Primary care Diabetes clinic Internet |

5 (41.7 %) 4 (33.3 %) 2 (16.7 %) 1 (8.3 %) |

|

| Behaviour change goal | PA* only PA and diet PA, diet and self management |

2 (16.7 %) 3 (25.0 %) 7 (58.3 %) |

|

| Delivery method | Individual Group Both |

7 (58.3 %) 4 (33.3 %) 1 (8.3 %) |

|

| Intervention staff | Mixed group of HP* Peer counsellors Research staff Other |

4 (33.3 %) 4 (33.3 %) 2 (16.7 %) 2 (16.7 %) |

|

| PA outcome measures | Self-reported Objective None |

9 (75.0 %) 1 (8.3 %) 2 (16.7 %) |

|

| PA results | Significant increase (p < 0.05) Increase with trend (p > 0.05) No change Not reported |

5 (41.7 %) 3 (25.0 %) 1 (8.3 %) 3 (25.0 %) |

|

| Study quality | High Medium Low |

Reliable 6 5 1 |

Useful 8 4 0 |

*HP health professionals, PA physical activity

Table 2.

Individual study characteristics of the 12 studies included in the review

| Author | Reference number | Design | Duration, n | Intervention | PA measures | Effectiveness | Study quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process measures | |||||||

| Bastiaens et al. 2009 Belgium |

21 | Longitudinal pilot Goal: PA, diet and self-management Setting: Primary care |

3 months Follow-up: 18 months n = 44 |

Five 2-h fortnightly group sessions. Additional 3-month follow-up meeting to reinforce maintenance issues. Intervention delivered by various HPs. Contact time = 12 h |

IPAQ | Not reported due to low follow-up numbers | Reliability - Low Usefulness - Medium |

| Attendance Data collection Staff support Patient insight | |||||||

| Clark et al. 2004 UK |

22 | RCT Goal: PA and diet Setting: Clinic |

3 months Follow-up: 12 months n = 100 |

Four 30-min individual consultations and three 10-min follow-up phonecalls over 12 months. The control group received usual care. Intervention delivered by research staff. Contact time = 2.5 h |

PASE DSCAQ |

Significantly greater PA levels in intervention group measured by DSCAQ at both 3 and 12 months (p < 0.001). No significant change in PA levels measured by PASE (p = 0.087) | Reliability - Medium Usefulness - Medium |

| Patient insight | |||||||

| Eakin et al. 2008 Australia |

23 | RCT Goal: PA and diet Setting: Primary care via telephone |

12 months Follow-up: 18 months n = 434 |

Eighteen 20-min telephone calls delivered over 12 months, with decreasing frequency. Patients also provided with home resources including pedometer and resistance band. Control group received usual care. Intervention delivered by staff with health related degree. Contact time = 6 h |

CHAMPS Active Australia Survey |

Final results not available until 2013 | Reliability - High Usefulness - High |

| Call tracking Content fidelity Cost-effectiveness | |||||||

| Keyserling et al. 2002 USA |

24 | Three-armed RCT Goal: PA, diet and self-management Setting: Primary care/Clinic/Community |

6 months Follow-up: 12 months n = 200 Females only |

Group A received four individual counselling sessions by the nutritionist, two group education and multiple personal phone call consultations by the peer counsellors. Group B received four individual counselling sessions, and Group C received usual care. Intervention delivered by peers and nutritionist. Contact time = (A) 9 h, (B) 3 h | Caltrac activity monitor | Significantly greater increase in Group B than C at 6 months (p = 0.036), however, significantly greater increase in Group A than C at 12 months (p = 0.019). Significant overall group effect (p = 0.014) | Reliability - High Usefulness - Medium |

| Attendance Session duration Number of calls Follow-up participation | |||||||

| King et al. 2006 USA |

25 | RCT Goal: PA, diet and self-management Setting: Primary care |

2 months Follow-up: 2 months n = 400 |

Two tailored 3-h individual consultations with educator; using computer-assisted behaviour change programme. This group also received tailored phone calls in between the two visits. Control group received usual care. Intervention delivered by various HPs. Contact time = 4 h |

CHAMPS | Significantly greater increase in MVPA (p = 0.001) and resistance training (p < 0.001) compared to the control group | Reliability - High Usefulness - High |

| Computer-software usage Patient insight Protocol fidelity | |||||||

| Klug, Toobert and Fogerty 2008 USA |

26 | Longitudinal Goal: PA and diet Setting: Community |

4 months Follow-up: 8 and 12 months n = 243 |

Sixteen weekly 1.5-h group sessions including education and peer-focussed feedback on goals, barriers and resources. Protocol amended following initial pilot. Intervention delivered by peers and 'expert lecturer'. Contact time = 24 h |

SDSCA EBS |

Significant increase of PA levels (p = 0.0248) at 4 months. Follow-up data not reported due to minimal follow-up participants. | Reliability - High Usefulness - High |

| Attendance Patient insight Peer insight | |||||||

| McKay et al. 2001 USA |

27 | RCT pilot Goal: PA only Setting: Internet |

2 months Follow-up: 2 months n = 78 |

Web-based individual tailored PA programme, including access to behaviour change software, a personal coach and peer-to-peer support area. The control group only had access to diabetes information websites. Intervention delivered by occupational therapist. Contact time = approx. 2 h |

BRFSS | Significant increase in MVPA and walking in both groups (p < 0.001) | Reliability - Medium Usefulness - High |

| Participation Webpage usage Patient insight | |||||||

| Osborn 2011 USA |

28 | Process Evaluation Goal: PA, diet and self-management Setting: Clinic |

1 month Follow-up: 3 months n = 118 |

One 90-min individual culturally tailored education session. Based on formative focus groups and interviews with potential providers and service users. Intervention delivered by medical assistant/technician. Contact time = 1.5 h |

SDSCA | Insignificant trend for increasing PA levels (p = 0.23) | Reliability - High Usefulness - High |

| Feasibility Cost analysis Staff insight Patient insight | |||||||

| Plotnikoff et al. 2010 Canada |

29 | Longitudinal cohort case studies Goal: PA only Setting: Community via telephone |

3 months Follow-up: 3 months n = 8 |

Twelve weekly telephone calls of 10–15 min duration, aimed at increasing both aerobic physical activity and resistance activity. Intervention delivered by peers. Contact time = 2–3 h |

GLTEQ | No significant change in aerobic PA (p = 0.48) or resistance PA (p = 0.12) | Reliability -Medium Usefulness High |

| Feasibility Patient insight Peer insight | |||||||

| Richert et al. 2007 USA |

30 | Descriptive report of community programme. Goal: PA and self-management Setting: Community |

Flexible and ongoing since 2004 n = 1,500 patient contacts n = 35 peer educators |

A flexible relationship between peers and enrolees. Large-scale social marketing undertaken beforehand to develop the most appropriate service for the community. Recruitment via multiple community resources and established networks. Intervention delivered by peers. Contact time = not reported |

Population wide PA levels using BRFSS | Population PA levels showed increasing trend over the initial 2 years of the programme; this has continued to the present day | Reliability - Medium Usefulness - High |

| Attendance Method of peer support Staff insight Peer insight Recruitment | |||||||

| Two-Feathers et al. 2007 USA |

31 | Process Evaluation Goal: PA, diet and self-management Setting: Community |

5 months Follow-up: none n = 150 |

Five 2-h group sessions every 4 weeks, delivered in the community using culturally tailored information. Developed after focus group research with potential service users. Intervention delivered by peers. Contact time = 10 h |

None | Not reported | Reliability -High Usefulness -High |

| Attendance Retention Patient insight Peer insight Staff insight | |||||||

| Unsworth and Slee 2002 Australia |

32 | Process Evaluation Goal: PA, diet and self-management Setting: Community |

1.5 months Follow-up: 1.5 months n = 45 |

Six weekly 180-min group education sessions which the participant could attend alone or with their partner. Intervention delivered by various HPs. Contact time = 18 h |

Evaluation questionnaire | Insignificant trend of increasing PA levels | Reliability -Medium Usefulness -Medium |

| Attendance Patient insight |

IPAQ International Physical Activity Questionnaire, PASE Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly, DSCAQ Diabetes Self-Care Activities Questionnaire, CHAMPS Community Healthy Activities Model Program for Seniors, SDSCA Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities questionnaire, EBS Stanford Education Research Center Exercise Behaviour Scale, BRFSS Behavioural Risk Factor Surveillance System, GLTEQ Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire

Table 3.

Individual RE-AIM characteristics of the 12 studies included in the review

| Author | Reference | Reach | Effectiveness | Adoption | Implementation | Maintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bastiaens et al. 2009 | 21 | Sample characteristics for ethnicity and income not reported. Barriers were addressed and users involved in the evaluation process. No details of potential local sample | Not reported | Potential for adoption throughout Belgium discussed, due to lack of current service provision | Attendance: 44 % attended all six sessions. Attrition not reported. Programme developed by team of HPs. Amendments made following pilot study. Staff delivering the programme followed scripts and protocols | Designed with long-term maintenance of behaviour change in mind; moderate duration with follow-up support |

| Clark et al. 2004 | 22 | Not reported | Significantly greater PA levels in intervention group measured by DSCAQ at both 3 and 12 months (p < 0.001). No significant change in PA levels measured by PASE (p = 0.087) | Not reported | Attendance not reported. Attrition: 6 % (6/100). Patient insight reported and discussed | Long term follow-up and ongoing support for the intervention group |

| Eakin et al. 2008 | 23 | 72.6 % participation of eligible patients (434/598). Challenges reported recruiting minority groups (9 %) in addition to low income participants, despite targeting low income areas | Results not available until 2013 | Ten primary care sights involved in the study | Results available in 2013. Pilot work on recruitment undertaken prior to the study which informed the main recruitment process | Intervention developed with maintenance in mind, focussing on community supports and sustainability following the end of the intervention |

| Keyserling et al. 2002 | 24 | 91.3 % participation of eligible patients (200/219). The sample reflected the target population which were African American females, of which 29 % had an annual income of <US$10,000 | Significantly greater increase in Group B than C at 6 months (p = 0.036), however, significantly greater increase in Group A than C at 12 months (p = 0.019). Significant overall group effect (p = 0.014) | Programme delivered over several health care sites | Attendance ranged by site (27–84 %). Attrition of 15 % (29/200). High level of adherence to protocol and collection of follow-up data. Authors discuss the lack of subjective PA data | Intervention developed with maintenance in mind. Community supports were identified for ongoing long term sustainability |

| King et al. 2006 | 25 | 38–41 % participation rate by eligible patients. 17.8 % were non-Caucasian, and 5.1 % had an annual income of <US$10,000. Multiple methods of recruitment used | Significantly greater increase in MVPA (p = 0.001) and resistance training (p < 0.001) compared to the control group | 18–76 % adoption rate by eligible health care providers (depending on their status) within the USA health care system | Attendance not reported. Attrition of 7.7 % (26/335). Variety of trained staff delivered the intervention, reflecting a real-world setting, with high fidelity to the protocol | Short duration with no follow-up |

| Klug, Toobert and Fogerty 2008 | 26 | 73.0 % of sample reported an annual income of <US$25,000. 19 % were non-Caucasian. Multiple methods of recruitment, with service users consulted beforehand | Significant increase of PA levels at 4 months (p = 0.0248). Eight- and 12-month follow-up data not reported | Eight individual community sites chose to participate in the programme and assist with recruitment | 87.7 % (213/243) attended at least two sessions. Attrition of 60.1 % (146/243) at 4 months follow-up, and 82.3 % (200/243) at 12 months, attributed to difficulty with data collection rather than dropout. Conducted an initial pilot study carried out providing insight into recruitment and implementation issues (n = 144). Protocols used for both peer delivery and site recruitment. Peers maintained fidelity on delivery | Ongoing bi-monthly meetings were held with the peer counsellors to ensure ongoing fidelity to the programme and provide long-term support |

| McKay et al. 2001 | 27 | Potential for nationwide reach (participants represented 60.8 % of the states of USA). Ethnicity and income not reported. Multiple methods of recruitment used, however low uptake due to strict inclusion criteria | Significant increase in MVPA and walking (p < 0.001) | Not reported | Steep decline in webpage usage over time, which was reported as more prominent in the control group. Attrition of 12.8 % (10/78) | Short duration with no follow-up |

| Osborn 2011 | 28 | 64.8 % participation rate of eligible participants (118/182). The sample reflected the target population, reaching participants of Latino ethnicity. Income not provided, with 39 % reported as unemployed | Insignificant trend for increasing PA levels (p = 0.23) | One site initially targeted | Attendance of 100 %. Staff and service users involved in intervention development. Staff were observed to ensure fidelity to protocol. Cost of USD$58 per patient | The authors report that providers could not adopt the programme long term due to minimal grant funding. No further patient follow-up |

| Plotnikoff et al. 2011 | 29 | Study undertaken as feasibility study with small sample (n = 8). Ethnicity and income not reported | No significant change in aerobic PA (p = 0.48) or resistance PA (p = 0.12) | Not reported | Attendance of 100 %. Feedback from peer counsellors indicated successful delivery of information, but duration too short to observe changes in measureable outcomes | Short duration with no follow-up |

| Richert et al. 2007 | 30 | 1,500 contacts made with enrolees within 2-year period. Multiple methods of recruitment undertaken within low income area. Local survey reported 11 % of the population had heard of the project at 2 years. Details of ethnicity not provided | Population PA levels increased over the initial 2-year period (2005–2007). Population level sedentary activity has decreased to the present day (2011) | High level of adoption by local organisations, with strong sustained partnerships with external organisations to the present day | Attendance and attrition not applicable. Based on intensive social marketing for development and delivery of the intervention. High level of preparation and networking done by project staff prior to recruitment. All peers trained on a regular basis and provided with ongoing support | Ongoing peer recruitment is key to the sustainability of the programme, therefore, free incentives are offered to peers to maintain the programme. The peer volunteer base has increased from 35 (in 2007) to 100 (2011) |

| Two-Feathers et al. 2007 | 31 | 300 eligible participants identified, with 151 taking part (50.3 %). Multiple methods of recruitment undertaken to reach participants of African-American and Latino ethnicity in a low-income community | Not reported | Several organisations involved in both recruitment and promotion | 63 % attended four of five sessions. Attrition of 26.5 % prior to intervention start. Peers were observed using a checklist to record fidelity to the programme, and also record questions asked by participants | Moderate duration (5 months); however, no long term follow-up was reported |

| Unsworth and Slee 2002 | 32 | Not reported, however, the programme continues to run (>10 years), indicating success in relation to reach of the programme. Information related to ethnicity and income not provided | Insignificant trend for increasing PA levels | Programme still operating to the present day across urban Western Australia, by several provider organisations | 80 % attended all six sessions. Attrition not reported. Community supports identified for maintenance. High attendance and high level of patient satisfaction with the programme | Programme still operating to the present day across urban Western Australia |

Reach

All articles reported sufficient data on the target population to allow basic comparison: 100 % reached adults with type 2 diabetes; with a mean age of 61.7 years; of which 65.4 % were female. Comparison of other factors including BMI, duration of diabetes and co-morbidities, was not possible due to lack of data. Variation in relation to inclusion criteria was minimal and all interventions successfully recruited suitable participants with type 2 diabetes, with some studies providing data showing successful recruitment of participants from high risk groups (Table 3).

Five articles (45.5 %) reported on the overall reach of the intervention from which a mean uptake of 63.7 % (SD 20.0) was observed. A potential overestimation of the reach of two interventions exists, where the number of 'eligible participants' did not reflect the large number of identified eligible participants who were then either unreachable or not interested in the intervention [30, 32].

Three studies tailored the intervention to a specific ethnic group, who were identified in each locality as a high-risk population (Latino and African American) [31, 35, 36]. The recruitment methods employed by these interventions specifically targeted the high-risk groups with tailored promotional material. All three studies provided reach data, showing uptake rates of 50.3 %, 64.8 % and 91.3 % (Table 3). The highest rate of uptake (n = 200/219) was observed in the Keyserling et al. [31] study, where a combined method of identifying eligible patients from both computerised records and routine physician visits was employed [31]. Other recruitment methods were reported, ranging from community marketing to online advertisements, with several interventions employing a mixture of these approaches. With only five papers reporting uptake data, comparison of these factors was difficult.

Effectiveness

Nine articles (75.0 %) reported on effectiveness of the intervention. Overall physical activity outcome measures and results are presented in Table 1, with individual study outcomes further presented in Tables 2 and 3. It is encouraging to note that of the nine articles reporting on effectiveness, eight interventions (88.9 %) showed an increase in physical activity levels from baseline, of which five reported a statistically significant increase (p < 0.05). The study by Bastiaens et al. [28] could not provide physical activity results due to low follow-up numbers. The reason for poor follow-up was not discussed, which is unfortunate because this was one of the few studies with a long follow-up period (18 months). The majority of interventions used self-report measures for physical activity, and included a variety of questionnaires previously used in behaviour change research (Table 2).

A range of intervention settings were used throughout the 12 studies (Table 1). No trend was apparent in the five interventions that showed a significant increase in levels of physical activity. Keyserling et al. [31] used a combined approach to setting, where interventions were delivered in both the diabetes clinic and community sites. At 6-month follow-up, when compared with the control group, the diabetes clinic setting showed a significant increase in levels of physical activity (p = 0.036), whereas the community group (p = 0.095) were not significantly different from the control group. However, during the following 6 months, only the community group received ongoing support which resulted in a significant change in levels of physical activity at 12 months in the community group (p = 0.019) compared with the clinic group (p = 0.31) (Table 2).

Adoption

Minimal information relating to the adoption of interventions by relevant staff and health care organisations was reported. Two exceptions include King et al. [32] and Osborne [35], where the authors based both the development and evaluation of their intervention on the RE-AIM framework. Their approach is reflected in the quality and usefulness of the information provided (Table 2). Osborne, in particular, reported high adoption by the staff and administrators within the local health care provider. However, the service was not adopted long-term due to a lack of funding.

Implementation

Implementation refers to whether an intervention was delivered as intended in relation to protocol fidelity, attendance, attrition, time and cost [20]. Fidelity to intervention protocols was high but reported in only six (50 %) articles. Protocol fidelity was measured by a variety of methods including; an observation or data checklist [32, 38]; observation of intervention delivery followed by ongoing feedback [35]; bi-monthly meetings to discuss intervention issues [33]; and self-evaluation by the individual delivering the intervention [36]. Six studies (50 %) in this review reported on attendance, ranging from 44 % to 100 % at all sessions. Six studies (50 %) reported a wide range of attrition, ranging from 6 % to 82.3 % at follow-up. Minimal information was provided regarding time and cost of intervention implementation.

Despite only 50 % of the studies reporting on the main aspects of implementation, it is also important to note that a wide range of process measures were utilised and reported across all 12 studies. These included session records, focus groups or interviews with staff and patients, and end of session questionnaires (Table 2). The information provided by these measures linked well with recommendations made by the authors of the RE-AIM Framework for ways to improve implementation (e.g., staff training, development of resources for implementation, and insight from staff and participants regarding the strengths and limitations of an intervention protocol) [20]. This additional but relevant information is therefore presented below.

Intervention protocols

Many studies identified the need for tailoring the intervention to the specific target population by undertaking extensive preparatory groundwork and/or social marketing. Tailoring involved the use of appropriate language, resources, mode and venue of delivery, and the use of positive role models in relation to either ethnicity [31, 35, 38] or socio-economic status of the local population [30, 37]. The Move More Diabetes programme, in particular, used extensive social marketing in the development of the intervention [37]. As a result, the intervention was based on the views of the service users. This approach may be reflected in the high rate of adoption by local organisations and the sustained and ongoing success of the programme to the present day (Table 3).

Current guidelines for physical activity behaviour change recommend the use of a theoretical framework, which incorporates behaviour change techniques such as goal setting, identification of barriers and problem solving [7, 8]. It is therefore encouraging to observe that 100 % of the intervention protocols based their approach on recommended behaviour change methods, with eight of the interventions (66.7 %) specifically mentioning use of either the Transtheoretical Model of Behaviour Change, Self-Efficacy Theory or Social Cognitive Theory [9–11].

A variety of resources were used throughout all studies. These included the development of resources for delivery of the specific intervention (e.g., participants resource packs, pedometer diaries), in addition to resources required for delivery of the overall study (e.g., recruitment protocols for external organisations, staff training manuals). Only one study described the development of resources in detail [38].

A range of staff were responsible for delivery of the interventions (Tables 1 and 2), with behaviour change training being undertaken in 91.7 % (n = 11) of the studies. Many of the interventions also involved ongoing training, support, evaluation and feedback for those staff delivering the programme. Of the nine studies reporting effectiveness eight interventions (88.9 %) resulted in increased levels of physical activity, all of which were delivered by a wide range of individuals (research staff, peer counsellors, occupational therapists, and others) who had received behaviour change training (Table 2).

There was an interesting mixture of methods used for intervention delivery including group sessions, individual face-to-face, individual telephone, individual online sessions and several interventions which used a combined approach (Table 1).

Contact time with participants during the intervention delivery ranged widely from 1.5 to 24 h (mean 8.9 h, SD 7.4) and a frequency of contact ranging from 1 to 18 sessions per participant (mean 8.4 sessions SD 5.2). The majority of interventions were of short duration (1–3 months) and although some showed an increase in levels of physical activity at the end of the intervention, long-term follow-up data was often lacking to show whether the changes were sustained long term. The 1-month intervention by Osborne showed an insignificant trend for increasing levels of physical activity at 3-month follow-up (p = 0.23) [35]. Staff involved in this intervention reported successful delivery and uptake of information but suggested that participants may have achieved measureable outcomes if the intervention was of longer duration (Table 2).

Staff and participant insight

Participant insight, across all 12 interventions, was consistently reported as satisfactory, especially among those attending group sessions [28, 33, 38]. End of study feedback found that group sessions allowed social interaction, discussion of ideas, help from other adults with diabetes and feelings of not being alone. Group interventions also reported themes of support, motivation and the positive use of peer role models. Participants valued the same person delivering all sessions when possible as this developed greater support and communication.

Participant insight in relation to individual sessions also showed a high level of satisfaction, but was not covered as in-depth as the group sessions, making comparison between the methods of delivery difficult.

Constructive feedback was also reported by staff delivering the interventions, including; the need for established routes of communication when using external organisations to prevent loss of participant follow-up [33]; a need for clearly defined roles and responsibilities within the team [35]; and greater maintenance strategies and follow-up in those interventions of short duration [36].

Maintenance

Five interventions (41.7 %) catered for long-term maintenance in their development and delivery of the intervention, with a follow-up period ranging from 12 to 18 months (Tables 2 and 3). Methods included a decrease in both frequency and duration of contact with participants over time, a change in method of delivery (e.g., ongoing support via telephone, instead of face-to-face meetings), and a long-term follow-up period.

A recurring theme was the requirement for a network of organisations to be involved in the recruitment, promotion and administration of the intervention. Those studies which involved a network of organisations appeared to achieve greater sustainability when compared to those interventions lacking a network. The ongoing Canadian intervention, Move More Diabetes by Richert et al. [37], described in detail the positive effect their network of external organisations had on the success of the intervention, and in particular commented on the time commitment of network staff and the need for recruiting motivated organisations (Table 3) [37]. This was further supported by Klug et al. [33], where the development phase of the study invested a significant amount of time ensuring networks were established prior to the delivery of the intervention (Table 2). The level of adoption by external organisations (e.g., community centres, religious centres, elderly day care centres) may therefore play a major role in the long term sustainability of interventions and is a key factor that should be taken on board by other researchers and policy makers who attempt to implement future interventions.

DISCUSSION

Previous systematic reviews have explored the various aspects of physical activity in the management of type 2 diabetes, including: the use of behaviour change techniques [12], web-based interventions [24], and structured physical activity training [13]. However, we know of no systematic review that has explored the delivery of physical activity interventions for the routine management of type 2 diabetes. This paper fills that gap in the literature. Following an extensive search, 12 articles were identified that met the inclusion criteria. Analysis of the articles, using the RE-AIM framework, revealed inconsistent reporting of process data, making analysis and interpretation of overall findings challenging.

Reach

The majority of interventions in this review targeted the general diabetes population, with several interventions targeting low socioeconomic areas or specific ethnic groups. With the exception of three interventions targeting individuals of Latino or African American ethnicity, the remaining studies predominantly recruited participants of Caucasian origin. Individuals from low income and certain ethnic origins are known to have a higher risk of type 2 diabetes and the need to develop effective strategies to address this inequality has been documented [40, 41].

Prevalence of diabetes in 2030 is estimated to have increased by 69 % in developing countries, compared with 20 % for developed countries [1]. Despite this global inequality, all 12 articles included in this review were undertaken in developed countries. Further evaluations are required of the complex challenges of intervention delivery in developing countries.

The identification of eligible participants using practical methods (i.e., computerised records and routine physician visits) was identified by several interventions, including Keyserling et al. [31] which reported the highest uptake (n = 200/219). Minimising the use of resource intensive methods for the identification of eligible participants may promote the overall reach of an intervention. This approach is supported by previous research, where the use of electronic records was beneficial in environments where health professionals were under pressure from time constraints and higher priorities [42].

Effectiveness

Positive findings were reported on the effectiveness of interventions included in this review. Nine of the 12 studies reported their outcomes on physical activity levels. Of those studies, eight interventions (88.9 %) showed an increase in levels of physical activity from baseline, of which five reported a statistically significant increase (p < 0.05). This is in line with the study of Avery et al., where 14 RCTs using self-report physical activity measures reported an overall significant increase in levels of physical activity [12]. Of the five studies in this review that reported significant increases in physical activity the mean intervention duration was 3.4 ± 1.7 months with a mean contact frequency of 8.3 ± 5.3 sessions. In comparison, two of the studies reporting an insignificant trend for increasing physical activity levels were of short duration (4–6 weeks) and involved fewer sessions (range 1–6). A review by Greaves et al. [5] identified that the most effective physical activity interventions within the diabetes population were those associated with a greater frequency of participant/counsellor contact. If these interventions had been of longer duration and greater frequency of contact they may have also resulted in significant physical activity outcomes. The three-arm intervention by Keyserling et al. positively showed that significant improvements in physical activity can be achieved in both the clinic and community setting; however, the group who received the greatest frequency of contact over a combined clinic and community setting were the only group to maintain a significant increase at 12-month follow-up. No other associations were found in this review between intervention delivery and effectiveness [31].

Physical activity interventions based on theoretical models of behaviour change have been shown to be more effective than non-theory based interventions [5, 43, 44]. Guidelines on physical activity for type 2 diabetes recommend the development of physical activity interventions based on a valid theoretical framework [7, 8]; therefore, it is positive to note that all 12 interventions adhered to these recommendations.

Eleven of the 12 articles used self-report measures for physical activity. Although not as accurate as objective measures (due to reporting bias), they have been shown to be reliable, inexpensive and practical tools for data collection in practice settings [44]. The exception was the high-quality study by Keyserling et al. [31]. The results showed a significant increase in levels of physical activity between three comparison groups (p = 0.014), with a long-term follow-up period, using an objective measure, in the form of accelerometry, and with a large sample size. A comparison with self-report measures would have been useful here to provide insight into the accuracy of participant perceptions of their physical activity behaviour. Care should be taken when choosing outcome measures for interventions in everyday practice. It is important to balance the need for robust measures with the practicalities of collecting data that does not disrupt the participant/counsellor relationship or the time constraints of the intervention. As identified by Bastiaens et al. [28], the burden on staff and resources can be reduced by obtaining data from 'usual-care' routes where possible.

Adoption

Information regarding adoption of interventions by staff and health services was minimal. The majority of interventions were of short duration with short-term follow-up; it is therefore possible that a time-dependent factor played a role in adoption. This is supported by an evaluation of the '10,000 Steps' programme which attempted to implement a widespread walking intervention in Belgium [45]. The authors reported 70 % of non-adopting organisations as “not having thought about adoption yet”, and suggest that more organisations would have adopted the programme over time. Pagoto [15] also states that adoption of interventions by health care services does not guarantee sustainability. Ongoing translation, adaptation and evaluation is required to sustain the continued adoption of effective interventions.

Implementation

Implementation of interventions was inconsistently reported by all 12 articles. Mixed findings for attendance and attrition were provided, with fidelity to the intervention protocol reported in only 50 % (n = 6) of articles. In a recent review of 80 health interventions for the British Medical Journal, Glasziou et al. [46] found that 50 % did not report sufficient information to enable the intervention to be effectively replicated. In addition, only 31 % reported on fidelity to the intervention protocol [46].

Behaviour change training for staff and peers delivering the intervention was outlined in 11 of 12 articles. Previous research on physical activity interventions has collectively found that health professionals often lack confidence, experience and ongoing feedback to promote the use of physical activity [47–49]. The authors of the RE-AIM framework suggest that the provision of training and support for individuals delivering interventions may improve protocol fidelity via an atmosphere of collaboration and peer problem solving [20]. In this review, positive outcome measures and high participant satisfaction suggest that a variety of individuals, given appropriate training, can effectively deliver physical activity interventions for adults with type 2 diabetes. Current guidelines for physical activity and diabetes [8] also address this issue, advising that professionals delivering patient centred interventions should receive ongoing training. There were inconsistent findings reported by the studies in this review to conclude whether ongoing staff training was associated with effectiveness of interventions.

The importance of tailoring recruitment, resources and procedures to the target diabetes population was discussed by several interventions, some of which undertook preparatory social marketing to understand the needs of potential participants. The need for tailoring interventions, in particular for different cultural and ethnic groups, has been highlighted by both the IMAGE Toolkit for diabetes prevention [50] and the Diabetes Prevention Program [51].

Participant feedback was satisfactory across all 12 interventions, with specific positive feedback by those attending group sessions. Other studies have previously reported the benefits of group education, including peer motivation and support, and a reduced burden on resources by targeting a greater number of participants in a single session [52]. Although specific positive feedback was minimal in this review, individual education sessions have also been identified as an effective method of delivering behaviour change information, in particular for individuals who require additional support [7].

Previous research has highlighted several barriers and facilitators for intervention delivery in practice. These included limited knowledge of departmental processes, staff turnover, staff commitment and funding [15–17]. Several of the studies included in this review identified similar factors. Two studies discussed the importance staff commitment in relation to the recruitment of external organisations that appeared motivated and willing to cooperate in programme fidelity [33, 37]. Funding was identified as a barrier to long-term adoption by staff in the study by Osborne [35].

Maintenance

Despite sustainability of health outcomes being a key objective, maintenance of behaviour change was addressed by only five (41.7 %) interventions. Methodology included decreasing the frequency and duration of contact with participants over time, reducing face-to-face contact, and employing long-term follow-up (ranging from 12 to 18 months). These methods are in line with the current evidence base, which recommends the incorporation of long-term maintenance strategies to promote sustainable behaviour change [53]. In this review, many interventions were of short duration and lacked long-term follow-up. This issue has also been identified in pedometer-based interventions for adults with type 2 diabetes, where a lack of follow-up data limits our understanding of the short term improvements in walking activity [54–56].

The use of external organisations in the ongoing recruitment, promotion and administration of an intervention appeared to play a positive role in the sustainability of several studies. These findings are supported by Goode et al. [57], who discussed the critical role of community organisations in the delivery and sustainability of a telephone delivered lifestyle change intervention. Organisations were involved in the ongoing adaptation of the intervention to ensure continued suitability for the target population, in addition to ongoing support of health professionals involved in the intervention delivery. The use of external organisations to support adoption and sustainability has also been recommended by other studies exploring the implementation of physical activity programmes [58, 59].

Despite the varied and inconsistent information provided by the 12 articles, this review has identified a number of important points for consideration when developing physical activity interventions for delivery in everyday practice.

Reach: The use of computerised records, external organisations and tailored recruitment may help to maximise intervention reach and uptake. Future publications should report accurate information on the reach of the intervention to illustrate full effectiveness.

Effectiveness: Positive findings indicate that in a practice setting, adults with type 2 diabetes can increase their levels of physical activity. A variety of methods can be used to gain positive physical activity behaviour change, including; diabetes clinic, telephone or community settings; individual or group counselling sessions; and intervention delivery by peers, health professionals or research staff. Adults with type 2 diabetes may respond to interventions differently, therefore, the flexibility of using various approaches tailored to the individual may be beneficial in achieving positive physical activity outcomes. Interventions undertaken in everyday settings face the challenge of gaining accurate data on physical activity levels by quick and easy methods. Future interventions should also consider collecting outcome data from routine-care routes to minimise disruption in intervention delivery.

Adoption: The importance of involving a network of external organisations was highlighted and future interventions should identify and network with motivated and culturally appropriate external organisations to improve levels of intervention adoption.

Implementation: Tailoring resources and intervention delivery to the target population appeared to play a positive role in achieving high rates of uptake, participant satisfaction and physical activity outcomes. These findings suggest that future interventions should undertake preparatory social marketing of the local diabetes population to enable interventions to be tailored and implemented effectively.

Maintenance: The majority of studies were of short duration (1–3 months) and long-term follow-up data (>12 months) was lacking from many interventions to evaluate whether maintenance strategies were successful in sustaining physical activity behaviour change. Future research should deliver interventions using methods of behaviour change maintenance, and report findings after a long-term follow-up period.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this systematic review is the focus on interventions delivered in an everyday practice setting. Previous reviews have reported findings from efficacy studies undertaken in a controlled research environment. This is the first review to focus on the broader aspects of intervention delivery in the context of everyday practice. This is a critical step in the progress of translational research for physical activity interventions in adults with type 2 diabetes. A team of reviewers were involved in the robust selection and data extraction of the articles included in this review, reducing the potential for selection bias.

This review has several potential limitations. Firstly, all included articles were undertaken in developed countries, limiting the generalisability of the overall findings. This is a reflection on the lack of publications reporting process information from interventions undertaken in developing countries. There is a high prevalence of type 2 diabetes in developing countries and publication of evaluation findings is encouraged. Secondly, inconsistent information was reported across all 12 articles, making comparison of some factors difficult. In particular, consistent reporting of reach would have provided greater insight into the characteristics of individuals participating in physical activity interventions within routine diabetes care.

CONCLUSIONS

This systematic review demonstrated that physical activity interventions for adults with type 2 diabetes can be effectively translated into an everyday setting. Positive findings showed that effective interventions can be delivered by a variety of trained staff/peers, in a variety of settings. The use of external organisations, behaviour change training, and tailoring of the intervention to the target population played a positive role. Future interventions, of longer duration, are now required to evaluate the maintenance of behaviour change in the long term. Importantly, this systematic review highlights the limited number of publications reporting on the translation of physical activity promotion from research to everyday practice for adults with type 2 diabetes. A varied level of information was reported throughout all 12 articles making comparison of data difficult. We therefore recommend that future publications relating to the translation of evidence into everyday practice use a tool, such as the RE-AIM framework, to report consistent and useful information.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a faculty PhD scholarship from the University of Strathclyde. The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Appendix 1

Footnotes

Implications

Policy: Research funding for physical activity in adults with type 2 diabetes should support the translation of interventions focused on long-term behavior change and follow-up.

Research: Given the importance of physical activity promotion in the management of type 2 diabetes, further interventions need to be effectively translated, implemented, evaluated, and consistently reported to inform future sustainable practice.

Practice: Future physical activity interventions should include partnership with relevant external organisations and staff training, in addition to tailoring recruitment, resources and intervention delivery to the target population.

References

- 1.Shaw J, Sicree R, Zimmet P. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87:4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chudyk A, Petrella R. Effects of exercise on cardiovascular risk factors in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(5):1228–1237. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Fernhall B, Regensteiner JG, Blissmer BJ, Rubin RR, et al. Exercise and type 2 diabetes: the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Diabetes Association: joint position statement executive summary. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(12):2692–2696. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas DR, Elliott EJ, Naughton GA. Exercise for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002968.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greaves CJ, Sheppard KE, Abraham C, Hardeman W, Roden M, Evans PH, et al. Systematic review of reviews of intervention components associated with increased effectiveness in dietary and physical activity interventions. BMC Publ Health. 2011;11:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kavookjian J, Elswick B, Whetsel T. Interventions for being active amoung individuals with diabetes: a systematic review of the literature. Diabetes Educ. 2010;33:962–988. doi: 10.1177/0145721707308411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirk AF, Barnett J, Mutrie N. Physical activity consultation for people with type 2 diabetes. Evidence and guidelines. Diabet Med. 2007;24(8):809–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Management of Diabetes. Edinburgh, UK: SIGN; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prochaska JO, Vilicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Heal Promot. 1997;12(1):38–48. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory. Ann Child Dev. 1989;6:1–60. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Avery L, Flynn D, van Wersch A, Sniehotta FF, Trenell MI. Changing physical activity behavior in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of behavioral interventions. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(12):2681–2689. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Umpierre D, Ribeiro P, Kramer CK, Leitao CB, Zucatti AT, Azevedo MJ, et al. Physical activity advice only or structured exercise training and association with HbA1c levels in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;305(17):1790–1799. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Estabrooks P, Glasgow R. Translating effective clinic-based physical activity interventions into practice. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(4S):S45–S56. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pagoto S. The current state of lifestyle intervention implementation research: where do we go next? Transl Behav Med. 2011;1:401–405. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0071-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glasgow R, Bull SS, Gillette C, Klesges LM, Dzewaltowski DA. Behaviour change intervention research in healthcare settings: a review of recent reports with emphasis on external validity. Am J Behav Med. 2002;23(1):62–69. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00437-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green L. From research to "best practices" in other settings and populations. Am J Health Behav. 2001;25(3):165–178. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.25.3.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dombrowski S, Sniehotta F, Avenell S. Towards a cumulative science of behaviour change: do current conduct and reporting of behavioural interventions fall short of good practice? Psychol Heal. 2007;22:869–874. doi: 10.1080/08870440701520973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Des Jarlais D, Lyles C, Crepaz N, the TREND Group Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: the TREND statement. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:361–366. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.3.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glasgow R, Boles S, Vogt T. Reach Effectiveness Adoption Implementation Maintenance (RE-AIM). [19-Feb-2012]; Available from: www.re-aim.org.

- 21.Austin G, Bell T, Caperchione C, Mummery WK. Translating research to practice: using the RE-AIM framework to examine an evidence-based physical activity intervention in primary school settings. Heal Promot Pract. 2011;12(6):932–941. doi: 10.1177/1524839910366101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Meij J, Chinapaw MJM, Kremers SPJ, Van der wal MF, Jurg ME, Van Mechelen W. Promoting physical activity in chidlren: the stepwise development of the primary school-based JUMP-in intervetnion applying the RE-AIM evaluation framework. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44:879–887. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.053827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Greef KB, Deforche B, Tudor-Locke C, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Increasing physical activity in Belgian type 2 diabetes patients: a three-armed randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Med. 2011;18(2):188–198. doi: 10.1007/s12529-010-9124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramadas A, Quek KF, Chan CK, Oldenburg B. Web-based interventions for the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review of recent evidence. Int J Med Inform. 2011;80(6):389–405. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, et al. PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petticrew M, Roberts H. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing; 2006. Starting the review: eefining the question and defining the boundaries (Chapter 2) pp. 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shepherd J, Kavanagh J, Picot J, Cooper K, Harden A, Barnett-Page E, et al. The effectiveness and costeffectiveness of behavioural interventions for the prevention of sexually transmitted infections in young people aged 13–19: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14(7):139–156. doi: 10.3310/hta14070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bastiaens H, Sunaert P, Wens J, Sabbe B, Jenkins L, Nobels F, et al. Supporting diabetes self-management in primary care: pilot-study of a group-based programme focusing on diet and exercise. Prim Care Diabetes. 2009;3(2):103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clark M, Hampson S, Avery L, Simpson R. Effects of tailored lifestyle self-management intervention in patients with type 2 diabetes. Br J Health Psychol. 2004;9:365–379. doi: 10.1348/1359107041557066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eakin EG, Reeves MM, Lawler SP, Oldenburg B, Del Mar C, Wilkie K, et al. The Logan Healthy Living Program: a cluster randomized trial of a telephone-delivered physical activity and dietary behavior intervention for primary care patients with type 2 diabetes or hypertension from a socially disadvantaged community — rationale, design and recruitment. Contemp Clin Trials. 2008;29(3):439–454. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keyserling TC, Samuel-Hodge CD, Ammerman AS, Ainsworth BE, Henriquez-Roldan CF, Elasy TA, et al. A randomized trial of an intervention to improve self-care behaviors of African-American women with type 2 diabetes — impact on physical activity. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(9):1576–1583. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.9.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.King DK, Estabrooks PA, Strycker LA, Toobert DJ, Bull SS, Glasgow RE. Outcomes of a multifaceted physical activity regimen as part of a diabetes self-management intervention. Ann Behav Med. 2006;31(2):128–137. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3102_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klug C, Toobert DJ, Fogerty M. Healthy Changes for living with diabetes: an evidence-based community diabetes self-management program. Diabetes Educ. 2008;34(6):1053–1061. doi: 10.1177/0145721708325886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKay HG, King D, Eakin EG, Seeley JR, Glasgow RE. The diabetes network Internet-based physical activity intervention — a randomized pilot study. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(8):1328–1334. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.8.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Osborne C. Development and implementation of a culturally tailored diabetes intervention in primary care. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1:468–479. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0064-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Plotnikoff RC, Johnson ST, Luchak M, Pollock C, Holt NL, Leahy A, et al. Peer telephone counseling for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a case-study approach to inform the design, development, and evaluation of programs targeting physical activity. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36(5):717–729. doi: 10.1177/0145721710376327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richert ML, Webb AJ, Morse NA, O'Toole ML, Brownson CA. Move more diabetes: using lay health educators to support physical activity in a community-based chronic disease self-management program. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33(Suppl6):179S–184S. doi: 10.1177/0145721707304172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Two-Feathers J, Kieffer EC, Palmisano G, Anderson M, Janz N, Spencer MS, et al. The development, implementation, and process evaluation of the REACH Detroit Partnership's Diabetes Lifestyle Intervention. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33(3):509–520. doi: 10.1177/0145721707301371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Unsworth M, Slee R. Evaluation of the Living with Diabetes Program for people with Type 2 diabetes: East Metropolitan Population Health Unit 2001–2002. Perth, Western Australia: East Metropolitan Population Health Unit; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quick Reference Guide. Preventing Type 2 Diabetes: Population and Community Interventions. London: National Health Service; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whittemore R, Melkus G, Wagner J, Dziura J, Northrup V, Grey M. Translating the diabetes prevention program to primary care: a pilot study. Nurs Res. 2009;58(1):2–12. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e31818fcef3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glasgow RE, Bull SS, Gillette C, Klesges LM, Dzewaltowski DA. Behaviour change intervention research in healthcare settings: a review of recent reports with empahsis on external validity. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23(1):62–69. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00437-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kahn E, Ramsey L, Brownson R, Heath G, Howze E, Powell K, et al. The effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2002;4(Suppl 1):73–107. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00434-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prince S, Adamo KB, Hamel ME, Hardt J, Gorber SC, Tremblay M. A comparison of direct versus self-report measures for assessing physical activity in adults: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5(56):1–24. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Acker R, De Bourdeaudhuij I, De Cocker M, Klesges LM, Cardon G. The impact of disseminating the whole community project '10,000 steps': a RE-AIM analysis. BMC Public Health. 2011; 11(3). doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Glasziou P, Chalmers I, Altman DG, Bastian H, Boutron I, Brice A, et al. Taking healthcare interventions from trial to practice. Br Med J. 2010;341:c3852. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jansink R, Braspenning J, van der Weijden T, Elwyn G, Grol R. Primary care nurses struggle with lifestyle counseling in diabetes care: a qualitative analysis. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11(41):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Korkiakangas EE, Alahuhta MA, Laitinen JH. Barriers to regular exercise among adults at high risk or diagnosed with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Health Promot Interational. 2009;24(4):416–427. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dap031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morrato EH, Hill JO, Wyatt HR, Ghushchyan V, Sullivan PW. Are health care professionals advising patients with diabetes or at risk for developing diabetes to exercise more? Diabetes Care. 2006;29(3):543–548. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.03.06.dc05-2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lindstrom J, Neumann A, Sheppard KE, Gilis-Januszewska A, Greaves CJ, Handke U, et al. Take action to prevent diabetes — the IMAGE Toolkit for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in Europe. Horm Metab Res. 2010;42:S37–S55. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1240975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes Prevention Program: Lifestyle Manual of Operations. 1996. Retrieved 12th December, 2012, from http://www.bsc.gwu.edu/dpp/manuals.htmlvdoc.

- 52.van Dam H, van der Horst F, Knoops L, Ryckman R, Crebolder H, van den Borne B. Social support in diabetes: a systematic review of controlled intervention studies. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;59:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fjeldsoe B, Neuhaus M, Winkler E, Eakin E. Systematic review of maintenance of behavior change following physical activity and dietary interventions. Heal Psychol. 2011;30(1):99–109. doi: 10.1037/a0021974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.De Greef K, Deforche B, Tudor-Locke C, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Increasing physical activity in Belgian type 2 diabetes patients: a three-arm randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Med. 2011;18(3):188–198. doi: 10.1007/s12529-010-9124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Negri C, Bacchi E, Morgante S, Soave D, Marques A, Menghini E, et al. Supervised walking groups to increase physical activity in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(11):2333–2335. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Furber S, Monger C, Franco L, Mayne D, Jones L, Laws R, et al. The effectiveness of a brief intervention using a pedometer and step-recording diary in promoting physical activity in people diagnosed with type 2 diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance. Health Promot J Aust. 2008;19:189–195. doi: 10.1071/he08189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goode AD, Owen N, Reeves MM, Eakin EG. Translation from research to practice: community dissemination of a telephone-delivered physical activity and dietary behavior change intervention. Am J Heal Promot. 2012;26(4):253–259. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.100401-QUAL-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]