Abstract

The aim of the present review was to examine objective and subjective burdens in primary caregivers (usually family members) of patients with bipolar disorder (BD) and to list which symptoms of the patients are considered more burdensome by the caregivers. In order to provide a critical review about caregiver’s burden in patients with bipolar disorder, we performed a detailed PubMed, BioMedCentral, ISI Web of Science, PsycINFO, Elsevier Science Direct and Cochrane Library search to identify all papers and book chapters in English published during the period between 1963 and November 2011. The highest levels of distress were caused by the patient’s behavior and the patient’s role dysfunction (work, education and social relationships). Furthermore, the caregiving role compromises other social roles occupied by the caregiver, becoming part of the heavy social cost of bipolar affective disorder. There is a need to better understand caregivers’ views and personal perceptions of the stresses and demands arising from caring for someone with BD in order to develop practical appropriate interventions and to improve the training of caregivers.

Keywords: Bipolar disorder, Caregivers, Burden, Prevention

Core tip: This broad overview suggests that there is vast literature about the consequences the caregivers of patients with a bipolar disorder (BD) are confronted with, the distress they experience and the coping styles they use to deal with the consequences. Available data suggest that caregiver burden is high and largely neglected in BD. Informal caregivers are central to the wellbeing of patients, but at the same time researchers, policy makers and formal service providers often take for granted their co-operation and welfare.

INTRODUCTION

In its 1999 annual report, the World Health Organization[1] reported that mood disorders are the most frequent causes of morbidity and mortality in developed countries.

Bipolar and unipolar mood disorders compromise quality of life, efficiency at work, and cause chronic impairment more than cardiovascular diseases, according to findings of Ogilvie et al[2]. Besides making persons/patients suffer, bipolar disorders also have a deep impact on life quality of families and caregivers[3]. Bipolar disorder (BD) is a recurrent severe mental disease with a prevalence ranging from 1.3%-1.6%[4,5] to 3.8%[6]. Extremely different moods such as mania, hypomania and depression cause sudden changes in behavior, feelings and thoughts. They also cause alterations in the level of energy. BD has been included, together with four other psychiatric conditions, among the ten leading causes of disability worldwide in 1990, measured in years lived with a disability[7] and compromises both family and personal relationships, lifestyle, work, education, healthcare and cognitive capabilities[8-11].

Many persons/patients seem to have residual symptoms during remission[12-14], confirming that functional recovery is much more difficult to achieve than syndromal recovery during hospitalization[15]. Perception of the quality of life, in and outside the family, is altered for the patient[16]. Family members are affected by every episode of this illness as well as scared of a possible relapse when the disorder is stabilized[17]. However, in the psychiatric approach prevalent in the treatment of persons/patients with BD, the medical attention is focused on the patient, while family members do not receive sufficient consideration.

Family members may carry a genetic predisposition for psychiatric morbidity which may be manifested as a result of the stress induced by the relative with BD.

The stress-coping model may be considered as a fundamental paradigm for examining care givers burden in all disorders, including BD. Using the stress-vulnerability model as a conceptual framework, it is possible to understand the role of stress when the effects of the illness appear and a specific vulnerability exists. The stress-coping paradigm explains the effects of stress on health according to a contextual approach about how the coping processes allow reducing the negative implications of stress and improving adaptation in conflicting situations[18]. Szmukler et al[19], aiming to develop a valid self-report measure of the experience of caring for a relative with a serious mental illness, initially conceptualized caregiving within the “stress-appraisal-coping” framework. Analyses of responses to the 66-item version of the Experience of Caregiving Inventory (ECI) were obtained from 626 caregivers and then tested on 63 relatives of patients with schizophrenia in acute care. The authors investigated the degree to which the ECI complied with the stress-coping model in association with coping and predicted psychological morbidity in carers. Results showed that the ECI, together with coping style, predicted a large proportion of the variance in the General Health Questionnaire, suggesting that the ECI identified important dimensions of caregiving distinct from coping and psychological morbidity.

This would, however, be of great importance since the support given by relatives is an essential contributor to the wellbeing of the person/patient and a positive prognostic factor. Independently of that, it would be of great importance to prevent the development of psychiatric disorders in family members as a response to the stress induced by the person/patient with BD.

A belief that family members’ behavior causes the disease has been replaced by the idea that it is the illness that causes discomfort in the relatives[20]. This is the reason why many studies are focusing on the impact of this illness on family members and caregivers. It is also known that caregivers of persons/patients with long-term illness show stress, depression and health problems[21,22].

Murray et al[7] emphasized the impact of the main psychiatric illnesses on individuals and immediate social groups in the world. The burden of caring for a psychiatrically ill family member has been classified into two categories, the “objective” and the “subjective” burden[23]. The first category is what happens to family life that can be observed and verified, including separation and divorce in marriages, reduced social and leisure activities due to fears of stigma and financial difficulties[23]. The second category involves personal feelings related to such a burden for a caregiver, who often feels distressed, upset and unhappy[3,23-27].

Sometimes the caregiver also feels guilty for contributing to the illness or rejects the person/patient and gets angry because the illness is spoiling his or her life. In general, subjective burdens could be related to the development of affective symptoms[20]. A recent prospective study highlighted that caregivers suffer more when the person/patient develop depressive symptoms than when they develop manic symptoms[28]. In the context of caregiving, it is important to differentiate this concept from the concept of “family burden”. The term caregiving tends to focus on providing actual assistance in response to the illness and this experience may have both positive and negative elements within the experience. Family burden on the other hand, tends to be considered as the emotional experience (typically negative) associated with a relative’s illness, but this individual may or may not be involved in the provision of practical assistance[29,30].

The aim of this review was to examine objective and subjective burdens in primary caregivers (usually family members) of persons/patients with BD and to list which symptoms are considered more burdensome by the caregivers. Another aim of our study was to value the impact of BD on functioning in the relationship of parents, children and partners of persons/patients affected by this disease.

SEARCH REFERENCES

Search strategy

In order to provide a critical review about caregiver’s burden in persons/patients with BD, we performed a detailed PubMed, BioMedCentral, ISI Web of Science, PsycINFO, Elsevier Science Direct and Cochrane Library search to identify all papers and book chapters in English during the period between 1963 and November 2011.

The search used a combination of the following terms: “Bipolar disorder” or “manic-depressive illness” or “manic-depressive disorder” and “caregivers” or “family members” or “parent” or “partner” and “quality of life” and “psychosocial impairment” and “burden of disease”. Then, in a second step we searched the same terms specifying (title and abstract) as electronic search strategy in Medline to adequately focus on the specific field of interest. The reference lists of the articles included in the review were also manually checked for relevant studies. All English full-text articles reporting original data about the main topic were included.

Quality assessment

The principal reviewer (Pompili M) inspected all reports. Then, three reviewers (Pompili M, Innamorati M, Harnic D) independently inspected all citations of studies identified by the search and grouped them according to topic of the papers. Reviewers acquired the full article for all papers located. Where disagreement occurred, this was resolved by discussion with Serafini G who also with double-blind features inspected all articles located and grouped them following the major areas of interest identified by all authors. If doubt remained, the study was put on the list of those awaiting assessment, pending acquisition of more information. Included were all studies with data on caregivers of persons/patients with BD.

We excluded from our analysis any studies vaguely reporting on the taking care of the above mentioned disorders or using inadequate or unclear diagnostic criteria for such disorders or those inappropriately assessing bipolar disorders. Results of this search are presented in the paragraphs regarding the impact of living with persons/patients with BD.

Study design and eligibility criteria

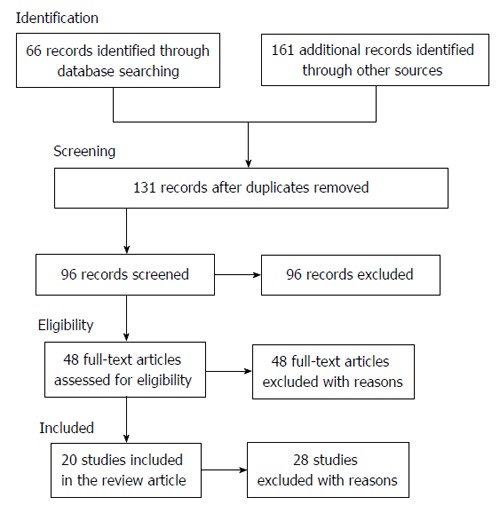

To achieve a high standard of reporting, we adopted ‘‘Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses’’ (PRISMA) guidelines[31]. The PRISMA Statement consists of a 27-item checklist and a four-phase flow diagram for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

OBJECTIVE AND SUBJECTIVE BURDENS IN PRIMARY CAREGIVERS OF PATIENTS WITH BD

Number of studies selected

The combined search strategies yielded a total of 227 articles of which, after a complete analysis, 96 full-text articles were screened and 131 were excluded. We excluded articles not published in peer-reviewed journals and not in the English language, articles without abstracts, abstracts that did not explicitly mention caregivers’ burden in patients/persons with BD and articles with a publication date before 1963. Forty-eight full-text articles were assessed for eligibility but twenty-eight full-text articles were excluded due to low-relevance to the main theme, including unclear data regarding materials and methods and number of patients analyzed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Search strategy used for selecting studies (identification, screening, eligibility, inclusion in the systematic review).

Psychiatric symptoms and other health consequences in caregivers of persons/patients with BD

Chakrabarti et al[32] found that BD brought more objective burden on caregivers of hospitalized patients and outpatients than unipolar depression. High levels of critical, hostile or emotionally overinvolved attitudes (high expressed emotion) in parents or partners of persons/patients with BD were described world-wide[10,33-35].

Subjective burden for the caregiver was the source of moderate distress highly related to the patient’s behavior, followed by the adverse effects on others; nearly 70% of caregivers were distressed by the way the illness had affected their own emotional health and their life in general. The patient’s role performance was a source of lower distress level[17]. Caregivers of persons/patients with BD, similar to caregivers of persons/patients with other major affective or chronic psychiatric disorders, report high levels of stress and poorer general health, increased visits to their primary care physicians, and higher numbers of symptoms of physiological and psychological conditions, including depressed mood, when compared to caregivers who report less stress[36-39].

Caregivers are those who attend to or provide services to an individual in need, typically one suffering from chronic illness or disability. According to a few researchers, they experience increased symptoms of depression or anxiety[40]. Psychiatric distress in samples of caregivers of persons/patients with BD was measured in few studies[41-44]. Few studies[37,38,44,45] measured mood symptoms in caregivers of persons/patients with BD, especially depressive symptoms. Two further studies published in the literature measured anxiety symptoms in caregivers of persons/patients with BD[36,46]. Only one paper measured caregiver psychotic symptoms[46].

The illness rarely changed the nature of work of the caregivers. However, 76% of the caregivers working outside home had to reduce their hours of work or take time off work during episodes of illness, according to one study in Australia[8]. At the same time, 27% of caregivers had experienced a reduction in their income since the onset of the patient’s illness. Patients also had difficulty managing their finances during an episode of illness so that almost half of the caregivers care for the patient’s finances at those times. Parents and partners of persons/patients with BD had the burden of these costs more frequently than other caregivers[8].

The economic impact of caregiving was expressed by time off from paid work because of caring obligations, the impossibility of accepting a full-time job and offering flexibility that employers might normally require or, in other words, to use their potential in economic/career terms, etc. A study in the United States showed that direct economic consequences were represented by the significant financial contributions that family members, especially parents and siblings, often make in order to support their relatives with BD[47].

It was quite usual to have police involvement with patients during at least one episode of illness (66%) and, although legal repercussions were rare, it caused significant stress for many caregivers[8]. Most commonly, caregivers were disturbed by aggressive and violent behaviors (17%), suicidal ideas and acts, odd behaviors (10%), overactivity, overtalkativeness, impulsive spends (each 4%) and suicidal ideation and attempts. During depressive episodes, the depressed mood itself (with its accompanying misery and hopelessness) disturbed the caregivers the most[8]. There is no universally accepted definition of burden of care but the concept of burden is associated with the patient’s poor social performance that is usually reflected in the caregiver’s burden. The original distinction between objective and subjective burden has been described by Hoenig and Hamilton[26]. They identified objective burden that included anything occurring as a disrupting factor within family life owing to patient’s illness and subjective burden that referred to the feeling that a burden is being carried in a subjective sense.

Objective burden - which would include problem behavior, financial burden and the effect on the family of the patient

The caregiver’s role is hard, frequently distressing and frequently affects health and quality of life[48]. A high burden level on relatives of persons/patients with BD has been reported[8,32,49] and recent studies have shown that caregiver’s burden may influence the clinical outcome of BD[50,51]. Caregivers who experience higher levels of burden in caring for persons/patients with bipolar illness have a negative influence on the course of the illness, especially on the patient’s medication adherence and on the risk of future mood episodes[51]. Perlick et al[51] have argued that caregivers with a higher level of distress can behave differently towards the patient and this could affect the clinical outcome. Reducing burdensome aspects might help to abolish burden negative effects both on the caregivers and patient outcome. According to the literature, a prolonged illness and high levels of impairment among patients[32], caregiver illness beliefs[49] and coping style[52] influence the family burden perceived by relatives of persons/patients with BD The illness often impacts on the partner’s life. Most partners said that the illness made their relationship difficult and, as a result, separations because of illness-related difficulties were common[8].

All the parents with bipolar disorders interviewed said that a major problem for them was monitoring and managing their own emotions in relation to parenting[53]. For parents with bipolar disorders, it was highlighted that there was a need for teaching moderation to their children and monitoring it in their children’s development. The consequence of this for these parents was a heightened sense of the need for self-surveillance[53]. These authors concluded that the challenge for people working with parents who have been diagnosed with a BD is to support them to feel confident in the management of their BD and their ability to parent effectively[53].

A need to understand caregivers’ views and perceptions of the stresses and demands arising from caring for someone with BD is emerging because developing practical, appropriate and acceptable interventions and improving the training of professionals working with persons/patients with BD and their caregivers can make patient outcomes better and reduce caregiver distress[2].

Some disruptions include changes to household, social and leisure activities, employment and finances[8,23]. Caregivers of persons/patients with BD who had experienced a relapse during the previous 2 years experienced a higher level of burden, especially subjective burden, according to the number of previous episodes. So, the level of burden may be sensitive to “recent” crises, as reported by Perlick et al[49]. Finally, subjective burden is also influenced by the sense of responsibility for drug intake[54]. As a result, avoiding relapses or increasing the time to relapse, improving inter-episode functioning, promoting the autonomy of the patient and reducing the caregiver’s responsibility level for the patient’s treatment should be crucial goals of psychosocial treatment of BD[17].

According to the tripartition of caregivers defined by Platt[3], the effective caregivers have reported no diseases, a low level of stress and adaptive coping; the burdened caregivers have shown a high level of stress linked to the subject’s behavior and less adaptive coping; the stigmatized caregivers were stressed due to perceived stigma, effective coping and were healthy. The level of stress and health among caregivers are strictly linked, whereas those with a higher degree of caregiving strain have a poor health and mental health[55].

Regarding burdensome aspects, Perlick et al[49] identified that the most frequently distressing behaviors for caregivers were hyperactivity, irritability and withdrawal. Other authors have mentioned aggressive or violent behavior, impulsive spending, depressive mood and suicidal ideas and acts among the symptoms creating the biggest burden[8,56]. Lam et al[41] found that most of the symptoms that were seen by partners as non-illness related and due to temperament or choice were either behavioral deficits or impulse control problems.

Although a high percentage of caregivers experienced disruptions to household management, this issue generates far lower distress levels than those mentioned above. Most caregivers were significantly distressed by the way the patient related to them when unwell. Partners and parents particularly found this stress major (the marriages of persons/patients with BD often result in separation and divorce according to some authors[57]). In addition, most caregivers experienced significant disruption in social activities and leisure pursuits common when the patient was unwell, especially partner caregivers[8]. It seems clear the caregivers cope better with illness related symptoms than actions related to the patient personality. This finding highlights the need for good psychiatric education, not only of the patient, but also of his/her immediate social group[8].

The effect of the requirement for emotional regulation in persons/patients with BD was that the parents interviewed identified a need for constant surveillance of their behavior and interactions with their children and hypervigilance for any signs of abnormality. The stigma of mental disorder for the parents with BD had a significant impact on their sense of self and their identity[58-60].

Subjective burden - emotional and other consequences of caring for a relative with BD

Dore et al[8] showed the impact of illness on the caregivers relationship with the patient when he is unwell. Most caregivers (90%) found the patient distant and difficult to get close to during acute episodes of illness. The patient felt irritable when unwell (80%) and this frequently led to arguments that had never occurred before. Impulsivity and aggression may be common during episodes of mania or hypomania. Most caregivers (81%) were distressed by the relationship with the patient when the patient was acutely ill; 64% described the level of personal distress as ‘‘severe’’[8]. When patients became well again, their relationship with caregivers usually improved significantly, with 80% of the group feeling that the relationship remained close during times of remission. Almost half of the group (49%) felt the illness had brought them closer. A closer relationship was more common if the patient was male and the caregiver female.

Families, who often end up supporting and caring for them, suffered the consequences of the illness in terms of a high rate of marital and long-term partnership breakdown[61]. Even if bipolar symptoms spontaneously subside, such as during untreated inter-episode periods, impaired functioning persists for many patients[62]. This loss of social functioning is a hard experience for caregivers and families that, in turn, can adversely affect the clinical outcome for the patient[50,63].

Most people who view themselves as informal caregivers have experienced an important transition in which existing spousal, family or friendship relationships were superimposed on the relationship of “carer-cared for”. These changes are related to specific symptoms, key illness related events and the stage of the disorder, but very little is known about the factors mediating these changes[2].

Lack of attention to the views of caregivers, the nature of the relationship between caregiver and patient, social circumstances and culturally situated health beliefs could be a risk in terms of impact upon both treatment interventions and the burden of care experienced by informal caregivers[2].

Dore et al[8] showed that the majority of caregivers were family members: parents (37%), a partner (32%) or another relative (24%). The caregivers’ average age was 46 years (range: 14-76). In the acute phase of his/her illness, the patient may become more irritable, distant and difficult to manage.

There is little information in the literature regarding spouses of persons/patients with BD. Only 56% of partners were aware BD could be inherited prior to the birth of their children and many (44%) decided not to have children because of that[8]. Separation/divorce is another consequence of illness[63-65]. Some authors define marriages as “intermittently incompatible” because they become unstable whenever the patient becomes unwell[66].

In addition, Targum et al[56] found that, compared with their spouses, patients do not feel any impact of BD on their family and the potential for offspring to develop the illness. In contrast, spouses would often reconsider marrying and having children if they have had a previous acknowledgement. Anyway, almost all patients and spouses want to know about genetic test information for their potential children; however, few of them would have reconsidered marriage or childbearing[67]. Janowsky et al[68] underlined that manic behaviors have greatest impact on the marital relationship. These behaviors included manipulation of others, projection of responsibility and progressive limit testing.

Suicide: Mood disorders are recognized as a major health care problem in many completed suicides and substantial illness burden worldwide[69]. Caregiver distress can be increased by the high risk of suicidality in BD persons/patients as up to 59% of patients may exhibit suicidal ideation or behavior during their lifetime[70].

Many attempted or completed suicides are characteristic for the longitudinal course of BD[61,71,72] This causes a significant distress for caregivers because of depression and/or suicidal thoughts or behaviors[8,23,49,56].

Cross-sectional data from Chessick et al[73] indicated that caregivers of patients with current suicidal ideation or a history of suicide attempts reported worse general health scores and higher levels of depressed mood than caregivers of patients without them. In 2009, Chessick et al[74] had two other major findings. Firstly, suicidal ideation increase in BD persons/patients from baseline to 6 and 12 mo reported worse general health to caregivers than a stable or decreased from baseline suicidal ideation, probably because caregivers could overextend themselves in the hope of ‘‘saving the patient’’ by taking on more responsibility for the patient than is sustainable for long periods of time[38]. Secondly, more suicidal ideation and more depressed mood at baseline and follow-up points have been correlated with more depressed mood at each time interval. Even so, previous data showed that patients with subsyndromal and post episode residual symptoms have significant psychosocial impairment, so further stress for the caregiver[28,75,76]. Frustration and distress in caregivers could also derive from any extension of the period before patients come back to work, education and other everyday functions after treatment resolved the major depressive episode[77]. These data may help to prospectively identify caregivers at risk for adverse health outcomes who may benefit from prevention focused intervention.

Family focused therapy (FFT) has also been adapted to treat suicidal symptoms in the persons/patient with BD[78]. Caregivers and patients are educated how to have open discussions of the patient’s suicidal ideation or previous attempts, identifying prodromal symptoms (i.e., depression and hopelessness) or psychosocial stressors (i.e., job or relationship loss) associated with the prior attempts, in order to address the patient’s future suicidal feelings or behaviors. That could relieve caregivers strain as well as reduce the probability of suicide attempts for the patient[79]. So family psychoeducation interventions for BD, such as FFT with its instructional material on caregiver self-care, could be beneficial[80], especially for caregivers living with patients with significant psychosocial dysfunction[74].

Violence towards the caregiver: Violence together with other symptoms in BD such as aggression, hyperactivity and disinhibition are a major source of distress for caregivers. Agitation and violence represent for clinicians some of the most fear-provoking aspect of psychiatry[81]. Patients with BD may show several forms of violence and aggression. Although violence risk prediction represents a priority issue for clinicians working with mentally disordered offenders[82], few studies in the medical literature have selectively addressed violence and aggression for caregivers of patients with BD. It is fundamental to understand the specific cause of distress experienced by caregivers as they can contribute to the overall management of this illness[8]. The ability of family members to identify behavioral patterns of bipolar patients prior to the episode of violence could help decrease the severity and consequence of violence[83].

Violence was more common towards partners than other caregivers and was not determined by the gender of the patient[8]. Nearly half the caregivers (44%) had experienced violence or were frightened that violence was going to occur when the patient was unwell, in fact experiencing serious forms of violence when the patient was unwell (nearly 25% of caregivers). Most partners (92%) found it difficult sustaining the relationship because of the illness of the other partner[8].

Amore et al[82] suggested that violent behavior in the month before admission was found to be associated with male sex, substance abuse and positive symptoms in 374 patients consecutively admitted inpatients in a 1-year period study. The most significant risk factor for physical violence was a past history of physically aggressive behavior.

Violence was confirmed as a particular worry for partner/parent caregivers of 41 BD patients when the patient was in a manic phase. The authors also suggested that the caregiver’s own mental health appeared unaffected[8].

Raveendranathan et al[83] investigated a total of 100 consecutive incidents of inpatient violence and found that bipolar spectrum disorder was the most common diagnosis. The authors suggested that family members were the targets of violence in 70% of these incidents, whereas 81% were provoked episodes. In addition, family members identified 76% of the patients as irritable only prior to the episode.

Aggressive and violent behavior were reported as most disturbing during mania by most caregivers and were really interpreted as symptomatic of the illness as well as not under the patient’s control[8].

In summary, violence towards the caregivers in patients with BD remains, no doubt, one of the most important, unaddressed and poorly epidemiologically investigated problem in clinical practice.

DISCUSSION

Results from our review suggest that the highest levels of distress were caused by patient’s behavior (nearly 70% of caregivers was distressed by the way the illness had affected their emotional health and their life in general) and by the patient’s role dysfunction (work, education and social relationships). Steele et al[84] in a recent review examined general psychiatric distress, anxiety symptoms and mood symptoms in caregivers and showed that caregivers of patients with BD had increased psychiatric symptoms, especially depression, that they wanted to be treated.

Goldstein et al[46] found that non-biological relatives caregiving 66 patients with BD type I (e.g., partners or spouses) had more DSM-III-R Axis I diagnoses than biological relatives, who had more diagnoses of mood and temperamental disturbances (i.e., BD). Indeed, it has been shown that parents were more distressed about suicidal ideation when their child had a history of suicide, whereas partners were more distressed about suicidal ideation when their partners had no history of it[46], suggesting that caregivers feel their responsibilities and roles depend on how they cope with patient symptoms. One explanation for these findings could be that parents caring for a patient with a history of suicidal behavior blame themselves and feel responsible for their child’s mental health history, while partners feel somehow responsible for “pushing” the patient towards suicide although they had never attempted it before.

Nehra et al[85], for example, found that caregivers of persons/patients with BD who had higher scores on neuroticism, a trait associated with depression and anxiety[86], used a more coercive coping (i.e., getting angry, shouting and using force) compared to caregivers of schizophrenic patients. In addition, Perlick et al[87] found that perceived stigma was positively associated with depressive symptoms, reduced social support and avoidance coping in 63% of that relationship.

Chronicity and disability present a significant challenge to caregivers and family members of affected persons so that nearly all caregivers of persons/patients with BD report at least moderate burden[37,49,52,88]. The degree of burden experienced by the caregivers because of depression in the patients should alert clinicians to the importance of initiating maximally effective treatment for bipolar depression, including structured psychotherapies (including family-focused therapy) and validated mediation treatments, to minimize the impact of those symptoms on caregivers. An interactive relationship between depressive symptoms and caregiver burden should be directly addressed[51]. The direction of the association between illness severity and burden cannot be easily assessed. It has previously been suggested that caregiver burden predicts whether a patient will have a symptomatic relapse of their affective illness[50]. Future studies should focus on caregiver coping styles[89] and on interventions (such as family therapies).

It is very clear that relationships with friends, family and acquaintances were often negatively affected for caregivers, resulting in the loss of friendships, tensions with neighbors and the experience of being stigmatised, especially with respect to police involvement with the patient’s illness. The majority of caregivers needed time off work and a third of caregivers had experienced a salary reduction since the onset of the illness. As a result, the caregiving role compromises other social roles occupied by the caregiver, becoming part of the heavy social cost of bipolar affective disorder. Severity of illness (defined as percentage of time unwell) was associated with greater caregiver burden[8].

The burden experienced by caregivers of persons/patients with BD has been associated with increased caregiver psychiatric conditions and mental health service utilization. Investigating the impact of caregivers burden in other chronic psychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia could be, in our opinion, helpful to understand the caregiver burden in BD. Caregivers of patients with schizophrenia experience a huge burden and are considered as a potential high risk group for developing psychiatric disorders[90]. Tan et al[91] found in a convenient sample of 150 caregivers of outpatients with schizophrenia high levels of burden due to several factors like other commitments, lack of resources, low financial support, education level and ageing. Kate et al[92] suggested that caregiving burden, in particular tension, is associated with dysfunctional coping strategies, poor quality of life and psychological morbidity in caregivers.

Burden of care for caregivers of patients with schizophrenia may be considered as a complex construct generally defined by its emotional, psychological, physical and economic impact on the quality of life of caregivers[93]. Many studies measured the burden of care in schizophrenia, whereas only some studies measured the burden experienced by the caregivers of patients with BD. To date, few studies have compared the degree of burden on the caregivers of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorders. Grover et al[94] reported that caregivers of schizophrenia patients experience caregiving more negatively compared with those of BD patients. The authors suggested that caregivers of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder experience a relevant burden while caring for their patients.

There are also studies suggesting that caregivers of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorders experience similar levels of burden using similar coping strategies to deal with it[89]. Similarly, Nehra et al[85] found high levels of patient dysfunction and caregiver burden in both bipolar disorders and schizophrenia, with no significant differences between the two groups. Although the caregiving experience has been extensively investigated in some chronic severe mental disorders, more methodologically and culturally relevant studies are needed in order to understand the differential aspects of emotional and psychological burden on caregivers of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorders.

Several studies confirmed that caregivers of persons/patients with bipolar disorders often seek mental health care[36,41,43]. Nadkarni et al[95] investigated support services available for parents of youth with BD.

Existing studies on family caregivers of persons/patients with psychiatric disorders have been traditionally conducted on negative aspects of caregiving focusing on caregiver’s burden. However, it is also important to describe the potential rewards and positive aspects of caregiving. Veltman et al[96] investigated caregivers’ perspectives on both the negative and positive aspects of caregiving. Interestingly, even beneficial effects such as feelings of gratification, love and pride have been reported by caregivers. Specifically, caregivers described the importance of life lessons learned, love and caring for persons/patients with psychiatric conditions. Helping to identify the rewards of caregiving may improve caregiving abilities to face distress and challenging situations, reducing the global caregiver burden.

Also, Bauer et al[97] examined the potential rewards of caregiving and coping strategies of 60 caregivers of people with psychiatric disorders using semi-structured interviews. They identified 413 individual statements of rewards; the items with the highest factor loading are the increase in self-confidence, inner strength, maturity and life experience. The authors highlighted the importance of providing an adequate knowledge about caregivers’ burdens.

It was found that parents of persons/patients with BD may benefit from a variety of interventions. Generally, the interventions to reduce caregivers burden could be grouped under simple interventions at clinician’s level (e.g., enquiring about burden, psychoeducational and support interventions) and the more complex interventions such as family interventions. It has been suggested that identifying and modifying burdensome aspects may help to reduce the level of burden and their negative effects on the caregivers also improving patients outcome[17].

Studies evaluating interventions on caregivers were shown to improve caregiver quality of life[98,99]. However, although interventions may be associated with reduced burden[100] and a stronger family competence[101], generally few caregivers seek out support for themselves.

Caregivers of persons/patients with BD can benefit from psychoeducational interventions designed to provide information, support and stress management skill building[95]. It has been demonstrated in randomized controlled trials that a psychoeducational approach can improve outcomes for both patients and families[102,103]. The ways of intervention have to be investigated with further studies but what is sure at this time is that professionals and non-professional caregivers should work together to support people with affective disorder more efficiently. Perlick et al[104] suggested that caregivers treated with a psychoeducational and cognitive-behavioral approach in the family focused treatment health promoting intervention condition reported a significant reduction in depressive symptoms and improvement in health behaviors when compared to caregivers who received education alone. They also experienced significant reductions in subjective burden associated with the patient’s symptoms and role dysfunction during the course of treatment.

There are also potential short-term interventions that can be provided at the time of hospitalization for families of patients with mood disorders and are associated with an improvement of caregiver’s burden[105].

Considering that male caregivers dropped out at higher rates than female caregivers, specific engagement strategies could be required to engage younger male caregivers experiencing high level of burden and distress[50].

Introducing suitable psychosocial interventions for caregivers means knowing more about their experiences. However, before this is possible, in-depth understanding of the nature of caregiver burden in relation to bipolar disorders is needed. Future studies should address the issue of caregivers’ burden related to bipolar disorders; specifically, there is the need to understand the various components of difficulties experienced by caregivers of with BD.

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations. It does not provide meta analytic results or comparisons between the studies. This is, of course, a major issue for further research in this field. Also, more literature might be available other than that located with our search strategy. It presents findings in a tutorial fashion, lacking extrapolations of figures that may be useful for a better estimation of the problem. Moreover, major differences might be found between studies reporting on caregivers’ burden. Furthermore, another criticism must be reported. There are many methodological difficulties in conceptualizing and measuring caregiver burden[106]. Relevantly, the concept of caregivers burden has been viewed as multidimensional although caregivers burden has been generally divided in to objective and subjective burden by Hoenig and Hamilton[26]. We stress the need of further research in this field.

CONCLUSION

In summary, this broad overview suggests that there is considerable literature about the consequences the caregivers of persons/patients with BD are confronted with, the distress they experience and the coping styles they use to deal with the consequences. Available data suggest that caregiver burden is high in BD. Informal caregivers are the central to the wellbeing of patients. This overview highlighted the need to better understand caregivers’ views and personal perceptions of the stresses and demands arising from caring for someone with BD in order to develop practical appropriate interventions and to improve the training of caregivers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Xenia Gonda is recipient of the Janos Bolyai Fellowship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers: Chakrabarti S, Gazdag G, Grof P S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: Roemmele A E- Editor: Liu SQ

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Annual Report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogilvie AD, Morant N, Goodwin GM. The burden on informal caregivers of people with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7 Suppl 1:25–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Platt S. Measuring the burden of psychiatric illness on the family: an evaluation of some rating scales. Psychol Med. 1985;15:383–393. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700023680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Müller-Oerlinghausen B, Berghöfer A, Bauer M. Bipolar disorder. Lancet. 2002;359:241–247. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07450-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists Clinical Practice Guidelines Team for Bipolar Disorder. Australian and New Zealand clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of bipolar disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2004;38:280–305. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2004.01356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oakley Browne MA, Wells JE, Scott KM. Te Rau Hinengaro: the New Zealand mental health survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray CJL, Lopez AD. The global burden of disease. A comprehensive assessment of the mortality and disability from diseases, injuries and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Boston, MA: Harvard School of Public Health on behalf of the World Health Organisation, and the World Bank; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dore G, Romans SE. Impact of bipolar affective disorder on family and partners. J Affect Disord. 2001;67:147–158. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00450-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simon GE. Social and economic burden of mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:208–215. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00420-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huxley N, Baldessarini RJ. Disability and its treatment in bipolar disorder patients. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:183–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pope M, Dudley R, Scott J. Determinants of social functioning in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:38–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fava GA. Subclinical symptoms in mood disorders: pathophysiological and therapeutic implications. Psychol Med. 1999;29:47–61. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Endicott J, Maser J, Solomon DA, Leon AC, Rice JA, Keller MB. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:530–537. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.6.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Coryell W, Endicott J, Maser JD, Solomon DA, Leon AC, Keller MB. A prospective investigation of the natural history of the long-term weekly symptomatic status of bipolar II disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:261–269. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.3.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tohen M, Hennen J, Zarate CM, Baldessarini RJ, Strakowski SM, Stoll AL, Faedda GL, Suppes T, Gebre-Medhin P, Cohen BM. Two-year syndromal and functional recovery in 219 cases of first-episode major affective disorder with psychotic features. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:220–228. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morselli PL, Elgie R, Cesana BM. GAMIAN-Europe/BEAM survey II: cross-national analysis of unemployment, family history, treatment satisfaction and impact of the bipolar disorder on life style. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6:487–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reinares M, Vieta E, Colom F, Martínez-Arán A, Torrent C, Comes M, Goikolea JM, Benabarre A, Daban C, Sánchez-Moreno J. What really matters to bipolar patients’ caregivers: sources of family burden. J Affect Disord. 2006;94:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leclerc C, Lesage A, Ricard N. [Relevance of the stress-coping paradigm in the elaboration of a stress management model for schizophrenics] Sante Ment Que. 1997;22:233–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szmukler GI, Burgess P, Herrman H, Benson A, Colusa S, Bloch S. Caring for relatives with serious mental illness: the development of the Experience of Caregiving Inventory. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1996;31:137–148. doi: 10.1007/BF00785760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tantum D. Familial factors in psychiatric disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 1989;2:296–301. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brodaty H, Green A. Who cares for the carer? The often forgotten patient. Aust Fam Physician. 2002;31:833–836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowery K, Mynt P, Aisbett J, Dixon T, O’Brien J, Ballard C. Depression in the carers of dementia sufferers: a comparison of the carers of patients suffering from dementia with Lewy bodies and the carers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Affect Disord. 2000;59:61–65. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fadden G, Bebbington P, Kuipers L. The burden of care: the impact of functional psychiatric illness on the patient’s family. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:285–292. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grad J, Sainbury M. Evaluating a community care service. In: Freeman H, Farndale J, editors. Trends in mental health services. Oxford: Pergamon Press; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 25.GRAD J, SAINSBURY P. Mental illness and the family. Lancet. 1963;1:544–547. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(63)91339-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoenig J, Hamilton MW. The schizophrenic patient in the community and his effect on the household. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1966;12:165–176. doi: 10.1177/002076406601200301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoenig J, Hamilton M. The desegregation of the mentally ill. London: Routledge and Keegan-Paul; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ostacher MJ, Nierenberg AA, Iosifescu DV, Eidelman P, Lund HG, Ametrano RM, Kaczynski R, Calabrese J, Miklowitz DJ, Sachs GS, et al. Correlates of subjective and objective burden among caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118:49–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sales E. Family burden and quality of life. Qual Life Res. 2003;12 Suppl 1:33–41. doi: 10.1023/a:1023513218433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poulin MJ, Brown SL, Ubel PA, Smith DM, Jankovic A, Langa KM. Does a helping hand mean a heavy heart? Helping behavior and well-being among spouse caregivers. Psychol Aging. 2010;25:108–117. doi: 10.1037/a0018064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chakrabarti S, Kulhara P, Verma SK. Extent and determinants of burden among families of patients with affective disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1992;86:247–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1992.tb03261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Honig A, Hofman A, Rozendaal N, Dingemans P. Psycho-education in bipolar disorder: effect on expressed emotion. Psychiatry Res. 1997;72:17–22. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(97)00072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Connell RA, Mayo JA, Flatow L, Cuthbertson B, O’Brien BE. Outcome of bipolar disorder on long-term treatment with lithium. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;159:123–129. doi: 10.1192/bjp.159.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Priebe S, Wildgrube C, Müller-Oerlinghausen B. Lithium prophylaxis and expressed emotion. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:396–399. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.3.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perlick DA, Hohenstein JM, Clarkin JF, Kaczynski R, Rosenheck RA. Use of mental health and primary care services by caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder: a preliminary study. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:126–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perlick DA, Rosenheck RA, Miklowitz DJ, Chessick C, Wolff N, Kaczynski R, Ostacher M, Patel J, Desai R. Prevalence and correlates of burden among caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder enrolled in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:262–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perlick DA, Rosenheck RA, Miklowitz DJ, Kaczynski R, Link B, Ketter T, Wisniewski S, Wolff N, Sachs G. Caregiver burden and health in bipolar disorder: a cluster analytic approach. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2008;196:484–491. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181773927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gallagher SK, Mechanic D. Living with the mentally ill: effects on the health and functioning of other household members. Soc Sci Med. 1996;42:1691–1701. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00296-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eisdorfer C. Caregiving: an emerging risk factor for emotional and physical pathology. Bull Menninger Clin. 1991;55:238–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lam D, Donaldson C, Brown Y, Malliaris Y. Burden and marital and sexual satisfaction in the partners of bipolar patients. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:431–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goossens PJ, Van Wijngaarden B, Knoppert-van Der Klein EA, Van Achterberg T. Family caregiving in bipolar disorder: caregiver consequences, caregiver coping styles, and caregiver distress. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2008;54:303–316. doi: 10.1177/0020764008090284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hill RG, Shepherd G, Hardy P. In sickness and in health: the experiences of friends and relatives caring for people with manic depression. J Ment Health. 1998;7:611–20. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tranvåg O, Kristoffersen K. Experience of being the spouse/cohabitant of a person with bipolar affective disorder: a cumulative process over time. Scand J Caring Sci. 2008;22:5–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2007.00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bernhard B, Schaub A, Kümmler P, Dittmann S, Severus E, Seemüller F, Born C, Forsthoff A, Licht RW, Grunze H. Impact of cognitive-psychoeducational interventions in bipolar patients and their relatives. Eur Psychiatry. 2006;21:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goldstein TR, Miklowitz DJ, Richards JA. Expressed emotion attitudes and individual psychopathology among the relatives of bipolar patients. Fam Process. 2002;41:645–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2002.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simon GE. Why we care about the economic and social burden of bipolar disorder. In: Maj M, Akiskal H, Lopez- Ibor JJ, Sartorius N, editors. Bipolar Disorder-WPA Series on Evidence and Experience in Psychiatry. London: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. pp. 474–476. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Struening EL, Perlick DA, Link BG, Hellman F, Herman D, Sirey JA. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: The extent to which caregivers believe most people devalue consumers and their families. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:1633–1638. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Perlick D, Clarkin JF, Sirey J, Raue P, Greenfield S, Struening E, Rosenheck R. Burden experienced by care-givers of persons with bipolar affective disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175:56–62. doi: 10.1192/bjp.175.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perlick DA, Rosenheck RR, Clarkin JF, Raue P, Sirey J. Impact of family burden and patient symptom status on clinical outcome in bipolar affective disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189:31–37. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200101000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perlick DA, Rosenheck RA, Clarkin JF, Maciejewski PK, Sirey J, Struening E, Link BG. Impact of family burden and affective response on clinical outcome among patients with bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:1029–1035. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.9.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chakrabarti S, Gill S. Coping and its correlates among caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder: a preliminary study. Bipolar Disord. 2002;4:50–60. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2002.01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wilson L, Crowe M. Parenting with a diagnosis bipolar disorder. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65:877–884. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vieta E. Improving treatment adherence in bipolar disorder through psychoeducation. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66 Suppl 1:24–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Katon W. Depression: relationship to somatization and chronic medical illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 1984;45:4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Targum SD, Dibble ED, Davenport YB, Gershon ES. The Family Attitudes Questionnaire. Patients‘ and spouses‘ views of bipolar illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38:562–568. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780300074009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brodie HK, Leff MJ. Bipolar depression--a comparative study of patient characteristics. Am J Psychiatry. 1971;127:1086–1090. doi: 10.1176/ajp.127.8.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Link BG, Struening EL, Rahav M, Phelan JC, Nuttbrock L. On stigma and its consequences: evidence from a longitudinal study of men with dual diagnoses of mental illness and substance abuse. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38:177–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Link BG, Struening EL, Neese-Todd S, Asmussen S, Phelan JC. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: The consequences of stigma for the self-esteem of people with mental illnesses. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:1621–1626. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Corrigan PW, Wassel A. Understanding and influencing the stigma of mental illness. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2008;46:42–48. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20080101-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goodwin FK, Jamison KR, Goodwin F. Suicide. In: Goodwin FK, Jamison KR, editors. Manic-depressive illness. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990. pp. 227–244. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dion GL, Tohen M, Anthony WA, Waternaux CS. Symptoms and functioning of patients with bipolar disorder six months after hospitalization. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1988;39:652–657. doi: 10.1176/ps.39.6.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McPherson HM, Dore GM, Loan PA, Romans SE. Socioeconomic characteristics of a Dunedin sample of bipolar patients. N Z Med J. 1992;105:161–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.DiNicola VF. The child’s predicament in families with a mood disorder. Research findings and family interventions. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1989;12:933–949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kessler RC, Walters EE, Forthofer MS. The social consequences of psychiatric disorders, III: probability of marital stability. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1092–1096. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.8.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Greene BL, Lustig N, Lee RR. Marital therapy when one spouse has a primary affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1976;133:827–830. doi: 10.1176/ajp.133.7.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Trippitelli CL, Jamison KR, Folstein MF, Bartko JJ, DePaulo JR. Pilot study on patients’ and spouses’ attitudes toward potential genetic testing for bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:899–904. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.7.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Janowsky DS, Leff M, Epstein RS. Playing the manic game. Interpersonal maneuvers of the acutely manic patient. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1970;22:252–261. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1970.01740270060008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pompili M, Rihmer Z, Innamorati M, Lester D, Girardi P, Tatarelli R. Assessment and treatment of suicide risk in bipolar disorders. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:109–136. doi: 10.1586/14737175.9.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Allen MH, Chessick CA, Miklowitz DJ, Goldberg JF, Wisniewski SR, Miyahara S, Calabrese JR, Marangell L, Bauer MS, Thomas MR, et al. Contributors to suicidal ideation among bipolar patients with and without a history of suicide attempts. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2005;35:671–680. doi: 10.1521/suli.2005.35.6.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Angst J, Angst F, Gerber-Werder R, Gamma A. Suicide in 406 mood-disorder patients with and without long-term medication: a 40 to 44 years’ follow-up. Arch Suicide Res. 2005;9:279–300. doi: 10.1080/13811110590929488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guze SB, Robins E. Suicide and primary affective disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 1970;117:437–438. doi: 10.1192/bjp.117.539.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chessick CA, Perlick DA, Miklowitz DJ, Kaczynski R, Allen MH, Morris CD, Marangell LB. Current suicide ideation and prior suicide attempts of bipolar patients as influences on caregiver burden. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2007;37:482–491. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.4.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chessick CA, Perlick DA, Miklowitz DJ, Dickinson LM, Allen MH, Morris CD, Gonzalez JM, Marangell LB, Cosgrove V, Ostacher M. Suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms among bipolar patients as predictors of the health and well-being of caregivers. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11:876–884. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00765.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kennedy N, Foy K, Sherazi R, McDonough M, McKeon P. Long-term social functioning after depression treated by psychiatrists: a review. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:25–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Altshuler LL, Gitlin MJ, Mintz J, Leight KL, Frye MA. Subsyndromal depression is associated with functional impairment in patients with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:807–811. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese JR, Marangell LB, Wisniewski SR, Gyulai L, Friedman ES, Bowden CL, Fossey MD, Ostacher MJ, et al. Effectiveness of adjunctive antidepressant treatment for bipolar depression. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1711–1722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Miklowitz DJ, Taylor DO. Family-focused treatment of the suicidal bipolar patient. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:640–651. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Miklowitz DJ, George EL, Richards JA, Simoneau TL, Suddath RL. A randomized study of family-focused psychoeducation and pharmacotherapy in the outpatient management of bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:904–912. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Currier GW, Allen MH. Emergency psychiatry: physical and chemical restraint in the psychiatric emergency service. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51:717–719. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.6.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Amore M, Menchetti M, Tonti C, Scarlatti F, Lundgren E, Esposito W, Berardi D. Predictors of violent behavior among acute psychiatric patients: clinical study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;62:247–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2008.01790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Raveendranathan D, Chandra PS, Chaturvedi SK. Violence among psychiatric inpatients: a victim’s perspective. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2012;22:141–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Steele A, Maruyama N, Galynker I. Psychiatric symptoms in caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder: a review. J Affect Disord. 2010;121:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nehra R, Chakrabarti S, Kulhara P, Sharma R. Caregiver-coping in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia--a re-examination. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40:329–336. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0884-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Costa PT, McCrae RR. NEO Five-Factor Inventory. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Perlick DA, Miklowitz DJ, Link BG, Struening E, Kaczynski R, Gonzalez J, Manning LN, Wolff N, Rosenheck RA. Perceived stigma and depression among caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:535–536. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.020826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cook JA, Lefley HP, Pickett SA, Cohler BJ. Age and family burden among parents of offspring with severe mental illness. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1994;64:435–447. doi: 10.1037/h0079535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chadda RK, Singh TB, Ganguly KK. Caregiver burden and coping: a prospective study of relationship between burden and coping in caregivers of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42:923–930. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lasebikan VO, Ayinde OO. Family Burden in Caregivers of Schizophrenia Patients: Prevalence and Socio-demographic Correlates. Indian J Psychol Med. 2013;35:60–66. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.112205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tan SC, Yeoh AL, Choo IB, Huang AP, Ong SH, Ismail H, Ang PP, Chan YH. Burden and coping strategies experienced by caregivers of persons with schizophrenia in the community. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21:2410–2418. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kate N, Grover S, Kulhara P, Nehra R. Relationship of caregiver burden with coping strategies, social support, psychological morbidity, and quality of life in the caregivers of schizophrenia. Asian J Psychiatr. 2013;6:380–388. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Awad AG, Voruganti LN. The burden of schizophrenia on caregivers: a review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26:149–162. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200826020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Grover S, Chakrabarti S, Aggarwal M, Avasthi A, Kulhara P, Sharma S, Khehra N. Comparative study of the experience of caregiving in bipolar affective disorder and schizophrenia. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2012;58:614–622. doi: 10.1177/0020764011419054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nadkarni RB, Fristad MA. Stress and support for parents of youth with bipolar disorder. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2012;49:104–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Veltman A, Cameron J, Stewart DE. The experience of providing care to relatives with chronic mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2002;190:108–114. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200202000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bauer R, Koepke F, Sterzinger L, Spiessl H. Burden, rewards, and coping--the ups and downs of caregivers of people with mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2012;200:928–934. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31827189b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Corring DJ. Quality of life: perspectives of people with mental illnesses and family members. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2002;25:350–358. doi: 10.1037/h0095002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cuijpers P. The effects of family intervention on relatives’ burden: a meta-analysis. J Ment Health. 1999;8:275–85. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dixon L, Stewart B, Burland J, Delahanty J, Lucksted A, Hoffman M. Pilot study of the effectiveness of the family-to-family education program. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:965–967. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.7.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Johnson ED. Differences among families coping with serious mental illness: a qualitative analysis. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70:126–134. doi: 10.1037/h0087664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Fristad MA, Goldberg-Arnold JS, Gavazzi SM. Multi-family psychoeducation groups in the treatment of children with mood disorders. J Marital Fam Ther. 2003;29:491–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2003.tb01691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fristad MA. Psychoeducational treatment for school-aged children with bipolar disorder. Dev Psychopathol. 2006;18:1289–1306. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Perlick DA, Miklowitz DJ, Lopez N, Chou J, Kalvin C, Adzhiashvili V, Aronson A. Family-focused treatment for caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12:627–637. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00852.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Heru AM, Ryan CE. Burden, reward and family functioning of caregivers for relatives with mood disorders: 1-year follow-up. J Affect Disord. 2004;83:221–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Schene AH, Tessler RC, Gamache GM. Caregiving in severe mental illness: conceptualization and measurement. In: Knudsen HC, Thornicroft G, editors. Mental health service evaluation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 296–316. [Google Scholar]