Endogenous danger signals link uveitogenic T cells with ocular inflammation, in an experimental autoimmune uveitis.

Keywords: autoimmune disease, experimental autoimmune uveitis, immunoregulation, autoreactive T cells, damage-associated molecular patterns, pathogen recognition receptors

Abstract

It is largely unknown how invading autoreactive T cells initiate the pathogenic process inside the diseased organ in organ-specific autoimmune disease. In this study, we used a chronic uveitis disease model in mice—EAU—induced by adoptive transfer of uveitogenic IRBP-specific T cells and showed that HMGB1, an important endogenous molecule that serves as a danger signal, was released rapidly from retinal cells into the ECM and intraocular fluid in response to IRBP-specific T cell transfer. HMGB1 release required direct cell–cell contact between retinal cells and IRBP-specific T cells and was an active secretion from intact retinal cells. Administration of HMGB1 antagonists inhibited severity of EAU significantly via mechanisms that include inhibition of IRBP-specific T cell proliferation and their IFN-γ and IL-17 production. The inflammatory effects of HMGB1 may signal the TLR/MyD88 pathway, as MyD88−/− mice had a high level of HMGB1 in the eye but did not develop EAU after IRBP-specific T cell transfer. Our study demonstrates that HMGB1 is an early and critical mediator of ocular inflammation initiated by autoreactive T cell invasion.

Introduction

Uveitis is a common cause of human visual disability and blindness. Although the etiology remains unclear, it is generally believed that a T cell-mediated immune response underlies the pathogenesis of the disease. and this is supported by the observation that injection of autoreactive T cells into susceptible, syngeneic rodents induces EAU [1–4]. Studies in the murine model of EAU, induced by a well-characterized uveitogenic autoantigen—IRBP—have shown that activation of autoreactive T cells is a key pathogenic event linked to disease induction, progression, and recurrence [2, 4–7]. It is assumed that there are two main phases in the immunopathology of uveitis: an initial peripheral priming/activation phase, in which autoaggressive lymphocytes are activated in the peripheral lymphoid organs, and a subsequent recruitment and effector phase, in which the invading T cells are reactivated inside the organ, leading to tissue destruction [8, 9]. Whereas a great deal of information is available about the development and activation of autoimmune T cells in the periphery in EAU, it remains unclear how autoreactive T cells exert their pathogenic effect inside of the eye, which is considered an “immune-privileged” site.

HMGB1, a major member of DAMPs, is an abundant nonhistone nuclear protein that is highly conserved across species (99% aa identity among mammals) [10, 11]. In the nucleus, it binds to DNA and regulates gene expression [10, 11]. HMGB1 can be released passively by necrotic cells, retained by apoptotic cells, or actively secreted by inflammatory cells [12]. Extracellular HMGB1 may signal via its putative receptors, TLR2 or TLR4 [13–15], TLR9 [16], and the Ig superfamily member RAGE [17, 18], and acts as a key inflammatory mediator in response to infection, injury, and inflammation [19–21].

The signaling of most TLRs requires a common intracellular adapter protein, MyD88. TLRs are one of the three groups of PRR family members that recognizes not only PAMPs, such as LPS, flagellin, bacterial lipoproteins, or viral RNA or DNA, but also DAMPs, including HMGB1, heat shock proteins, fibrinogen, fibronectin, hyaluronic acid, and S100A8-A9, which are released during stress responses [10, 12, 16, 22–25]. TLRs are mainly expressed on immune cells but are also expressed on tissue cells. In the mammalian nervous system, TLR family members have been detected on glia, neurons, and neural progenitor cells, in which they determine the fate of the cell [26]. TLRs, at the ocular surface, such as the corneal and conjunctival epithelia, might contribute to innate-immune responses that protect the eye from microbial infection [27]. Although intraocular cells, such as uveal epithelial cells [28], retinal pigmental epithelium cells [29, 30], retinal photoreceptor cells [31], and astrocytes [32–34] express TLRs, their responses to endogenous substances, such as DAMPs, in the eye and their roles in the pathogenesis of noninfectious ocular diseases remain largely unknown.

In this study, we investigated the pathogenic events associated with the entry of uveitogenic T cells into the eye using a chronic uveitis model (tEAU) induced by adoptive transfer of IRBP-specific T cells in B6 mice. We focused on determining whether activated, autoreactive T cells induce HMGB1 release by tissue cells and the role of HMGB1 in ocular inflammation, initiated by only a few invading uveitogenic T cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and reagents

Pathogen-free female B6 mice and B6 MyD88−/− mice (8–10 weeks old), purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA), were housed and maintained in the animal facilities of the University of Louisville. Institutional approval was obtained and institutional guidelines regarding animal experimentation followed.

All T cells were cultured in complete medium [RPMI 1640 medium (Mediatech, Manassas, VA, USA), supplemented with 10% FCS (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT, USA), 5 × 10−5 M 2-ME, and 100 μg/ml penicillin/streptomycin]. The human IRBP peptide IRBP1–20 (GPTHLFQPSLVLDMAKVLLD) was synthesized by Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Antibodies, specific for GFAP (Sigma-Aldrich) and Iba-1 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), were used for detection of RACs and microglial cells on the frozen sections of retina.

Induction of tEAU

The method used to induce tEAU has been reported previously [4, 35], Briefly, T cells from mice immunized with peptide IRBP1–20, 12 days previously, were purified from draining LNs and spleen cells by passage through a nylon wool column, and then 1 × 107 cells in 2 ml RPMI-1640 medium were added to each well of a six-well plate (Costar, Corning, NY, USA) and stimulated with 20 μg/ml IRBP1–20 in the presence of 1 × 107 irradiated syngeneic spleen cells as APCs. After 2 days, the activated lymph blasts were isolated by gradient centrifugation on Lymphoprep (Sigma-Aldrich) and injected i.p. in 0.2 ml PBS into B6 naive recipients (5×106 cells/mouse).

Pathological examination

Inflammation of the eye was evaluated by histopathology [4]. Whole eyes were collected, immersed for 1 h in 4% phosphate-buffered glutaraldehyde, and then transferred to 10% phosphate-buffered formaldehyde until processed. The fixed and dehydrated tissue was embedded in methacrylate, and 5-μm sections cut through the pupillary-optic nerve plane and stained with H&E. The presence or absence of disease was evaluated blind by examining six sections, cut at different levels for each eye. The severity of EAU was scored on a scale of zero (no disease) to four (maximum disease) in half-point increments, based on the presence of inflammatory cell infiltration of the iris, ciliary body, anterior chamber, and retina, with 0=normal anterior segment and retinal architecture, with no inflammatory cells in these structures; 1=mild inflammatory cell infiltration of the anterior segment and retina; 2=moderate inflammatory cell infiltration of the anterior segment and retina; 3=massive inflammatory cell infiltration of the anterior segment and retina and disorganized anterior segment and retina; and 4=as in 3 but with photoreceptor cell damage.

Treatment of tEAU with HMGB1 antagonists

Mice that received IRBP-specific T cells on Day 1 were injected i.p. with 40 μg anti-HMGB1 antibody or its control Ig (IBL International GmbH, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) every day from Days 1 to 4 and every other day from Days 6 to 12. Alternatively, anti-HMGB1 antibody (1 μg/eye) or its control Ig was given once into the anterior chamber to avoid retinal injury if injected into intravitreous, at the same day of T cell transfer. HMGB1 antagonists EP (Sigma-Aldrich) and glycyrrhizin (Calbiochem, EMD Chemicals, Gibbstown, NJ, USA) were i.p.-injected at 40 mg/kg on Days 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9. All experimental mice were killed on Day 15.

Assays for IRBP-specific T cell proliferation and cytokine production

Nylon wool-enriched T cells, prepared from IRBP1–20-specific T cell-injected B6 mice on Day 15 after cell injection, were seeded at 4 × 105 cells/well in 96-well plates and cultured at 37°C for 60 h in a total volume of 200 μl complete medium (described above), with or without IRBP1–20 in the presence of irradiated syngeneic spleen APCs (1×105) and [3H]thymidine incorporation during the last 8 h, assessed using a microplate scintillation counter (Packard Instrument, Meriden, CT, USA). The proliferative response was expressed as the mean cpm ± sd of three separate tests, each in triplicate. To measure cytokine production by responder T cells, supernatants were collected 48 h after T cell stimulation and assayed for IFN-γ, IL-17, and IL-10 using ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Isolation of RACs and retinal explants and coculture with T cells

Eyes were collected from naive B6 mice, and RACs or the neural retina (as a retinal explant) were isolated, as described previously [32, 33, 36, 37]. RACs, grown to confluence or retinal explants with the inner membrane facing up in a 24-well plate, were cultured in 500 μl DMEM/F12 medium (Mediatech) containing 1% FCS. Naive or activated T cells [5×106; prepared from IRBP1–20-immunized mice at Day 11 post-immunization with incubation with irradiated splenic APCs and IRBP1–20 (10 μg/ml) or Con A (2 μg/ml) for 2 days] were added, with or without an insert (3 μm pore; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The cells incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 18 h, and then HMGB1 in the supernatants was measured by ELISA.

Intraocular fluid collection

The removed eyeball was immersed in 200 μl PBS and cut in two; then, the cornea, sclera, and lens were discarded and the rest of the tissue cut into fine pieces. The suspension containing the aqueous humor, vitreous fluid, and fine pieces of tissue was centrifuged at 500 g for 5 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was stored immediately in a −80°C freezer until use. One-half volume (about 100 μl) of each collection from one eyeball was used for HMGB1 detection by ELISA.

ELISA for released HMGB1

Supernatants from retina explants or the intraocular fluid from each eyeball were collected, 100 μl each added to wells precoated with HMGB1 capture antibody, and levels of HMGB1 measured following the manufacturer's instruction (USCN Life Science, Houston, TX, USA).

Cell necrosis and apoptosis assays

To ensure that our secreted HMGB1 measurements were not confounded by nonspecific protein release as a result of cell damage, cytotoxicity was quantified using a standard measurement of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH kit; Sigma-Aldrich). TUNEL assay (in situ apoptosis detection kit; Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) was performed to assess the apoptotic cells.

Immunohistochemistry for the expression of HMGB1, MyD88, and RAGE

To detect the expression of HMGB1, MyD88, and RAGE on the retina, paraffin-embedded tissue slides were deparaffinized and rehydrated with xylene and 100%, 95%, and 80% ethanol. After antigen retrieval in a citrate-buffered solution in a boiling water bath, the tissue was blocked by incubation with 3% BSA for 1 h at RT, and then the slides were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary rabbit anti-mouse HMGB1 antibody (Abcam), rat anti-mouse MyD88 antibody (R&D Systems), or rat anti-mouse RAGE antibody (R&D Systems) followed by FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibodies or Cy3-conjugated anti-rat antibodies (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 1 h at RT. Then, nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich) and the slides examined by fluorescence microscopy.

Western blot analysis of the expression of MyD88 and RAGE

Retinal explants from mice at Days 0, 7, and 14 after transfer of IRBP-specific T cells were collected and lysates prepared by incubation for 5 min on ice in RIPA buffer [50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1.0% IGEPAL CA-630, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS (Sigma-Aldrich)] and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich) and run on SDS polyacrylamide gels. Western blotting was performed on nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), as described previously [33], using anti-MyD88 antibody or anti-RAGE antibody.

Statistical analysis

Experiments were repeated at least three times. An unpaired Student's t-test for two means and one-way or two-way ANOVA for three or more means were used for statistical analysis. P < 0.05 was considered significant. Values determined as significantly different from the control values are marked with an asterisk in the figures.

RESULTS

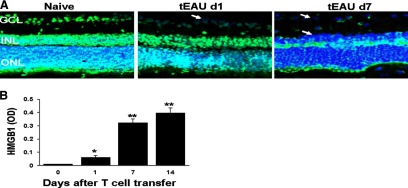

Prompt HMGB1 release in the eye in response to IRBP-specific T cell transfer

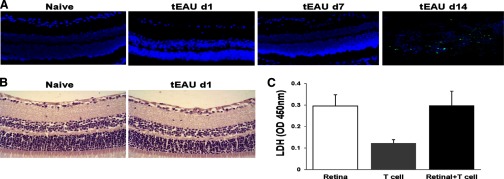

To determine whether uveitogenic T cells could initiate the release of DAMPs, which then promote ocular inflammatory cascade, we examined HMGB1 expression kinetically in retinal cells and intraocular fluid after IRBP-specific T cell transfer. Intracellular HMGB1 levels in the inner ganglion cell layer were reduced dramatically at 1 day after transfer and were almost undetectable in the entire retina at Day 7 after injection (Fig. 1A), whereas HMGB1 levels in the intraocular fluid increased significantly (Fig. 1B). Of note, HMGB1 release followed IRBP-specific T cell transfer immediately but preceded clinical disease, which usually could be observed at Days 8–12 post-T cell injection in recipient mice by indirect funduscopy and peaked ∼Day 14 [4].

Figure 1. HMGB1 in retinal cells and intraocular fluid of mice after IRBP-specific T cell transfer.

(A) HMGB1 (green) was detected by immunohistochemistry in the nuclei of retinal cells from naive mice (Day 0) but was released following IRBP-specific T cell transfer; the results shown are for Days 1 and 7 (d1 and d7) post-transfer. Blue, DAPI staining of the cell nucleus; GCL, ganglion cell layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer. The arrows show loss of HMGB1 in cells in the ganglion cell layer and inner nuclear layer. (B) HMGB1 levels were determined by ELISA in the intraocular fluid of eyes from mice before receiving IRBP-specific T cells (Day 0) and on Days 1, 7, and 14 after cell transfer (six eyes/group). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 compared with naive mice in one-way ANOVA.

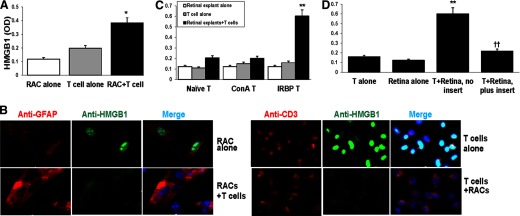

HMGB1 is secreted as a result of the interaction between retinal cells and IRBP-specific T cells

To determine the mechanism of HMGB1 release after IRBP-specific T cell transfer, we performed in vitro studies by coculturing IRBP-specific T cells with RACs (Fig. 2A and B) or retinal explants (Fig. 2C and D). Our results showed that after 18 h of coculture of RACs with activated IRBP-specific T cells, significant amounts of HMGB1 were detected in the supernatant (Fig. 2A). Moreover, the amount of HMGB1 was increased significantly when retinal explants were cocultured for 18 h with IRBP-specific T cells but not with naive T cells or Con A-stimulated, antigen-nonspecific T cells (Fig. 2C). As shown in Fig. 2B, HMGB1 was detected inside RACs (GFAP+) and activated IRBP-specific T cells (CD3+) when cultured separately but not detected in either cell type when cultured together, showing that HMGB1 was released from both cell types.

Figure 2. HMGB1 is released by cocultures of retinal cells and activated IRBP-specific T cells.

(A and B) RACs and/or activated IRBP-specific T cells (prestimulated with immunizing antigen and APCs for 2 days) were cultured for 18 h, and then culture supernatants were assayed for HMGB1 by ELISA (A) and the cells stained with the indicated fluorescent-conjugated antibody and visualized by fluorescence microscopy (B). (B) Staining is red for CD3 and GFAP, green for HMGB1, and blue for DAPI (cell nucleus). (C) Retinal explants and T cells from naive mice, Con A-stimulated T cells, or activated IRBP-specific T cells were cultured for 18 h, and then HMGB1 levels in the supernatants were measured. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 compared with cells cultured alone in two-way ANOVA with Fisher's least significant difference test. (D) Retinal explants and activated IRBP-specific T cells were cultured alone or together in the presence or absence of a cell insert for 18 h. **P < 0.01 compared with cells cultured alone and ††P < 0.01 compared with cells cocultured without cell insert in one-way ANOVA. (A, C, and D) The results are representative of the similar results for three separate experiments.

To determine whether a direct cell–cell interaction between retinal cells and IRBP-specific T cells is required for HMGB1 secretion, we performed studies in which retinal explants and IRBP-specific T cells were cultured together or separated by culture inserts. As shown in Fig. 2D, when retinal explants were cocultured with activated, IRBP-specific T cells without an insert, high levels of HMGB1 were found in the culture supernatant, whereas very low amounts were detected in cultures of retinal explants or IRBP-specific T cells alone or in cocultures of retinal explants and IRBP-specific T cells separated by the insert.

HMGB1 secretion from living retinal tissue cells

To distinguish between the possibilities that HMGB1 leaked passively from damaged cells or also actively secreted by stimulated, intact cells, we performed a TUNEL assay after injection of IRBP-specific T cells. As shown in Fig. 3A, on Day 1 post-T cell transfer, when appreciable amounts of HMGB1 had been released from the ganglion cell layer (Fig. 1), no TUNEL-positive cells (green) were seen in the retinal layer, as in naive mice. At Day 7 post-transfer, when HMGB1 had been largely released from the retina (Fig. 1), apoptotic cells were still not detected, indicating that over this period, HMGB1 was not released from dying retinal tissue cells but was clearly seen at Day 14 (peak of disease). HMGB1 was also not passively released from necrotic cell death at Day 1 post-T cell transfer, as retinal structure was intact compared with the naive retina (Fig. 3B). Moreover, a cytotoxicity (LDH) assay showed that the coculture of retinal explants and activated IRBP-specific T cells at 18 h did not cause more LDH release than retinal explants alone (Fig. 3C). Thus, the activated IRBP-specific T cell-induced release of HMGB1 from retinal cells was not a result of nonspecific cell lysis or injury.

Figure 3. HMGB1 is actively secreted by live retinal tissue cells.

(A) TUNEL staining for apoptotic (green) cells was performed on the retina of mice before (Day 0) and on Days 1, 7, and 14 after IRBP-specific T cell transfer. The blue staining shows DAPI-stained nuclei. (B) The retinal structure of naive and Day 1 post-transfer was examined by H&E staining (original magnification, ×400). (C) Retinal explants and activated IRBP-specific T cells were cultured alone or together for 18 h as in Fig. 2D, and then LDH levels in the supernatants were measured. Values are means ± sem of two independent experiments.

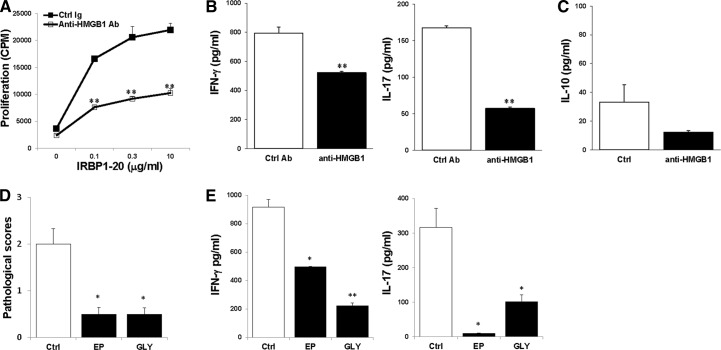

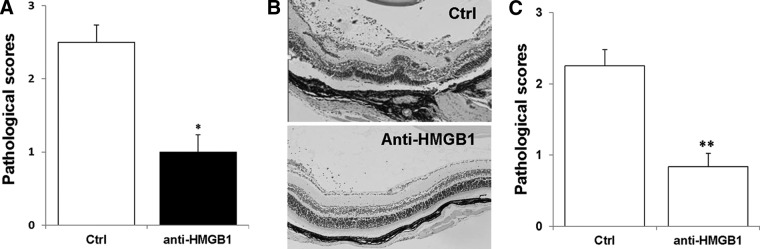

Inhibition of tEAU by HMGB1 antagonists

To determine whether HMGB1 promoted intraocular inflammation during the effector phase of EAU, we treated mice subjected to adoptively induced EAU with specific neutralizing anti-HMGB1 antibodies [38], either systemically (Fig. 4A and B) or locally (Fig. 4C), using the protocol described in Materials and Methods. Figure 4 shows the results at Day 15 after T cell transfer. Compared with the mice treated with control Ig, the anti-HMGB1 antibody-treated mice developed much milder ocular inflammation, as determined by histology, with a well-preserved retinal structure, and minimal vitreous infiltrates. To determine further the mechanisms by which the anti-HMGB1 antibody decreased the severity of IRBP-specific T cell-induced uveitis, we examined IRBP-specific T cell responses after systemic treatment with anti-HMGB1 antibodies. Significant depression of the proliferative response (Fig. 5A) and IFN-γ and IL-17 (Fig. 5B) production were seen in T cells from the mice treated with anti-HMGB1 antibodies. However, the level of IL-10 released by IRBP-specific T cells was not changed much between anti-HMGB1 antibody treated and control mice (Fig. 5C).

Figure 4. HMGB1 antagonists significantly inhibit the development of tEAU.

B6 mice injected with IRBP-specific T cells were systemically (A and B) or locally (C) treated with neutralizing anti-HMGB1 antibody or control (Ctrl) Ig, as described in Materials and Methods and examined on Day 15. (A and C) Pathological score of each group (n=12 mice) presented as the mean ± se. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 compared with the group treated with control Ig using Mann-Whitney U-test. (B) Representative ocular histopathology was shown in tEAU treated with control Ig and anti-HMGB1 antibodies; H&E staining; original magnification, ×100.

Figure 5. HMGB1 antagonists inhibit IRBP-specific T cells.

T cells from mice, systemically treated with anti-HMGB1 antibodies or control Ig, on Day 15 after T cell transfer, were cultured with irradiated APCs and IRBP1–20 and then, proliferation of responding T cells (A), and levels of IFN-γ and IL-17 (B) and IL-10 (C) released in the culture supernatants were measured. Pathological scores (D) and IRBP-specific T cell cytokine production (E) in the mice treated with EP, glycyrrhizin (GLY), or PBS (Ctrl; n=15 mice/group) on Day 15 after T cell transfer were shown. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 compared with the control group treated with PBS.

The role of HMGB1 in ocular inflammation was also examined using two other HMGB1 antagonists: EP, which inhibits HMGB1 release [39], and glycyrrhizin, which inhibits HMGB1 binding [40]. Consistent with the results of neutralizing HMGB1 antibodies, severity of tEAU (Fig. 5D) and IRBP-specific T cell production of IFN-γ and IL-17 were reduced markedly in mice treated with EP or glycyrrhizin (Fig. 5E).

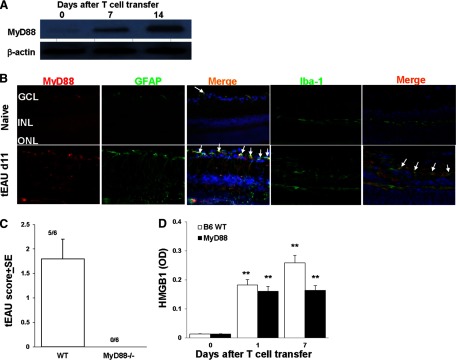

HMGB1 may use MyD88 signaling to play its role

To determine whether HMGB1 can act in an autocrine and paracrine manner, through the cell-surface expression of TLRs that activate MyD88, we examined the expression of MyD88 in the retina of B6 mice during the course of tEAU. With the use of a Western blot assay, MyD88 was barely detectable in the naive mouse retina, but its levels increased gradually with disease development, showing an increase at Day 7 post-T cell transfer and a marked increase at Day 14 post-T cell transfer (Fig. 6A). Immunohistological studies showed that MyD88 was expressed on GFAP+ (astroglial) and Iba-1+ (microglial) cells and cells negative for GFAP or Iba-1 on Day 11 post-T cell transfer (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6. Requirement of MyD88 molecule in the development of tEAU.

(A) MyD88 expression in retinas collected at Days 0, 7, or 14 after IRBP-specific T cell transfer was examined by Western blot. The loading control is β-actin. (B) MyD88 expression examined on frozen sections of retina from naive and Day 11 tEAU mice by staining with PE-conjugated anti-MyD88 antibodies (red) and FITC-conjugated anti-GFAP or anti-Iba-1 antibodies (green). Cell nuclei are stained blue with DAPI. Some double-positive cells are indicated by arrows. (C) Pathological score of WT or MyD88−/− mice (n=6/group) after adoptive transfer of IRBP-specific T cells. The incidence of tEAU was detected by pathological examination on Day 21 post-T cell transfer. (D) HMGB1 levels were determined by ELISA in the intraocular fluid of eyes from MyD88−/− mice before receiving IRBP-specific T cells (Day 0) and on Days 1 and 7 after cell transfer (six eyes/group). **P < 0.01 compared with naive mice in one-way ANOVA.

To determine further whether HMGB1 uses MyD88 molecules for its effect, we transferred the IRBP-specific T cells into WT or MyD88−/− mice. Histopathology showed that on Day 21 postinjection, all MyD88−/− recipient mice were symptom-free, whereas five out of six WT B6 mice developed disease signs (Fig. 6C). However, in MyD88−/− recipient mice, HMGB1 was detected after 1 day of T cell transfer (Fig. 6D), indicating that extracellular HMGB1 triggered by IRBP-specific T cells could not execute their proinflammatory role in the absence of MyD88.

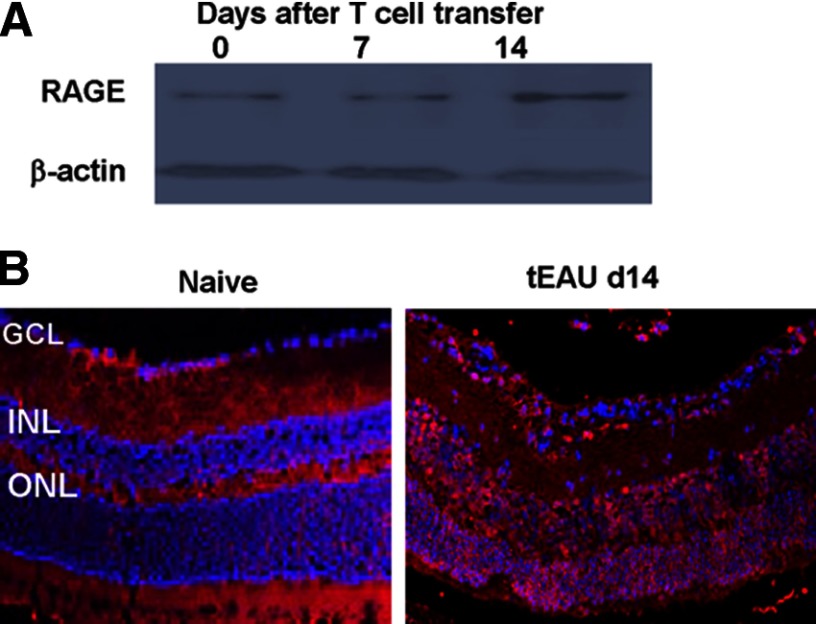

RAGE, the receptor for HMGB1 as well, is constitutively expressed in the retina. The level of RAGE expression was increased at Day 14 post-IRBP-specific T cell transfer, in particular, in infiltrating cells (Fig. 7), suggesting the involvement of RAGE in HMGB1-mediated ocular inflammation triggered by uveitogenic T cells.

Figure 7. RAGE expression in retinas.

RAGE expression in retinas was examined by Western blot (A) as in Fig. 6A and by immunohistochemistry (B) as in Fig. 6B but using anti-RAGE antibodies.

DISCUSSION

Up-regulated HMGB1 levels have been systemically detected in inflammatory autoimmune-mediated diseases in animal models and patients, indicating that HMGB1 has important roles in these diseases. Extracellular HMGB1 was also detected in the target organs in T cell-mediated, organ-specific autoimmune diseases, for example, in the aqueous humor of EAU induced by immunization of IRBP and CFA in Lewis rats [41] and in CSF of patients with NMO and MS [42–44]. In the former, increased HMGB1 seems to be associated with infiltrating inflammatory cells, as HMGB1 in the AqH was increased significantly at the peak of intraocular inflammation (Day 14 postimmunization) [41]; in the latter, CSF HMGB1 levels were high during the relapse phase of NMO and MS, especially NMO [42]. The increase of extracellular HMGB1 in the target organ suggests that HMGB1 is involved in and may trigger local inflammation and tissue cell damage. However, the mode of HMGB1 release and the association with autoreactive T cells in the target organs remain unknown. With the use of adoptive transfer of an IRBP-specific T cell-induced EAU model, we found that uveitogenic T cells could initiate the release of HMGB1 from viable retinal cells, as HMGB1 was detected immediately in the extracellular retina and ocular fluid after IRBP-specific T cell transfer (Fig. 1), and neither apoptotic nor necrotic cells were detected in the retina at Days 1 and 7 post-T cell transfer (Fig. 3). Further studies on the mechanism of HMGB1 release demonstrated that the interaction of activated IRBP-specific T cells with retinal cells could induce HMGB1 secretion by retinal cells and T cells (Fig. 2). It is interesting though that coculture of RACs or retinal explants with activated nonantigen-specific T cells did not trigger HMGB1 release (Fig. 2), which was also observed in our in vivo experiment; that is, injection of Con A-activated T cells failed to induce HMGB1 release in the retina (data not shown). These results might suggest that only fully activated and sufficient T cells that recognize ocular antigens presented by residential tissue-nonprofessional and/or -professional APCs can stimulate HMGB1 release. Cell-surface molecules for HMGB1 release might be necessary for contact-dependent release of HMGB1 between IRBP-specific T cells and retinal cells (Fig. 2). The involved cell-surface molecules are currently under investigation in our lab. These molecules are not excluded, such as Fas and FasL. It has been reported that the interaction between Fas and FasL promotes HMGB1 production by viable macrophages that is independent of caspase-mediated apoptotic signaling [45], similar to our observation that HMGB1 was released by live retinal cells after interaction with activated uveitogenic T cells.

The involvement of released HMGB1 in the pathogenesis of uveitis has been supported by the studies in which all three HMGB1 antagonists inhibited the severity of uveitis. Although HMGB1 has been reported to play multiple roles in various pathological conditions, relatively few studies have been done characterizing the mechanisms of HMGB1 on T cells in autoimmune diseases. Neutralizing released HMGB1 in the eye with anti-HMGB1 antibodies inhibited intraocular inflammation (Fig. 4C), which indicates that released HMGB1 in the eye by activated autoreactive T cells could trigger local PRR-dependent inflammation. Moreover, HMGB1 blockade reduced pathogenic T cell expansion and Th1 and Th17 cell cytokine production, whereas IL-10, produced mainly by Tregs, was not affected, demonstrating that released HMGB1 could up-regulate uveitogenic Th1/Th17 responses (Fig. 5) by the mechanisms that are currently under investigation in the lab. Suppression of Th17 cell expansion and attenuation of the disease by HMGB1 blockade were also observed in experimental autoimmune myocarditis [46]. HMGB1 promotes the differentiation of Th17 via up-regulating TLR2 and IL-23 of CD14+ monocytes from patients with rheumatoid arthritis [47]. In the human, however, HMGB1 directly enhances immune-inhibitory functions of Tregs via RAGE-mediated mechanisms and limits the number and activity of conventional T cells [48]. These studies suggest that the effects of HMGB1 on T cells may depend on the species and the pathophysiological settings, for example, acute versus chronic inflammatory states. In addition to being HMGB1 antagonists, EP, an aliphatic ester derived from pyruvic acid, has been reported to exert effects, such as scavenging of ROS, inhibiting apoptosis, and increasing cellular ATP synthesis [49]. In the eye, EP prevents ocular inflammation in endotoxin (LPS)-induced uveitis in rats [50] and prevents intracellular oxidative damage to the lens [51]. It is unknown, however, whether the anti-inflammatory effect of EP on LPS-induced uveitis is a result of a blockade of HMGB1 release. Similarly, glycyrrhizin, a major sweet component of a Chinese medicinal herb, liquorice, not only inhibits HMGB1 binding but also reduces ischemia-elicited leukocyte adherence and neutrophil infiltration into ischemic liver tissue [40].

HMGB1 may signal MyD88-involved pathways to play its inflammatory role in tEAU, as we demonstrated that MyD88 levels were increased significantly in the retina of WT mice during development of ocular inflammation, and mice lacking MyD88 were completely resistant to tEAU, induced by activated uveitogenic T cells in the absence of exogenous microbial products (Fig. 6). Thus, our results indicate that MyD88 is important in the effector phase of autoimmune uveitis. The ligands, such as DAMPs, that bind to TLRs could activate MyD88. In addition, activation of IL-1 and IL-18 can lead to MyD88 activation as well. Continuous study will be performed to identify TLRs engaged by HMGB1 and/or IL-1 and IL-18 in the effector phase of tEAU. In EAU, induced by immunization with an uveitogenic IRBP peptide in CFA, which contains microbial products, MyD88−/− mice are completely resistant to induction of EAU [52, 53]. In this model, MyD88 is required for IL-1 signaling, not TLRs and IL-18, as mice deficient in TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, and TLR9; mice double-deficient in TLR2 + −4, TLR2 + −9, and TLR4 + −9; or mice deficient in IL-18R were fully susceptible to EAU, whereas IL-1R-deficient mice are resistant to EAU. An increase in RAGE expression, particularly in infiltrating cells at the disease peak (Fig. 7), suggests the involvement of RAGE with HMGB1. The relationship of RAGE with TLR signaling pathways and the role of RAGE in protection or enhancement of ocular inflammation need to be studied.

In summary, we, for the first time, have demonstrated that activated autoreactive T cells could initiate target tissue cells to secrete DAMPs, such as HMGB1. These findings—that activated autoreactive T cells trigger local PRR-dependent inflammation—complement the current, popular concept of PRR-dependent T cell activation in autoimmunity. These findings also further our understanding of the pathogenesis of T cell-mediated autoimmune diseases, including uveitis, in particular, early events after specific T cell interaction with tissue cells and possible mechanisms of initiative or recurrent inflammatory attack by effector T cells in the eye. Additional investigations might reveal a therapeutic effect of controlling HMGB1 in relevant autoimmune diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported, in part, by National Eye Institute, U.S. National Institutes of Health, grant EY12974 (to H.S.), a Research to Prevent Blindness Lew R. Wasserman Merit Award (to H.S.), the Commonwealth of Kentucky Research Challenge Trust Fund (to H.K.), and Intramural Research Incentive Grants of the University of Louisville (to G.J.).

The editorial assistance of Dr. Tom Barkas is greatly appreciated.

Footnotes

- B6

- C57BL/6J

- CSF

- cerebrospinal fluid

- DAMP

- damage-associated molecule pattern

- EAU

- experimental autoimmune uveitis

- EP

- ethyl pyruvate

- FasL

- Fas ligand

- GFAP

- glial fibrillary acidic protein

- HMGB1

- high-mobility group box 1

- Iba-1

- ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1

- IRBP

- interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein

- MS

- multiple sclerosis

- MyD88−/−

- MyD88-deficient

- NMO

- neuromyelitis optica

- PRR

- pathogen recognition receptor

- RAC

- retinal astrocyte

- RAGE

- receptor for advanced glycation end products

- RT

- room temperature

- tEAU

- activated interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein-specific T cell-induced experimental autoimmune uveitis

- Treg

- regulatory T cells

AUTHORSHIP

G.J. performed all experiments and generated and analyzed the data. H.Y. provided some anti-HMGB1 antibodies and guidance for experiments. Q.L. helped with some experiments. D.S. and H.J.K. helped with designing experiments and writing the manuscript. H.S. directed the study, planned experiments, and wrote the manuscript.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Mochizuki M., Kuwabara T., McAllister C., Nussenblatt R. B., Gery I. (1985) Adoptive transfer of experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis in rats. Immunopathogenic mechanisms and histologic features. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 26, 1–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Caspi R. (2008) Autoimmunity in the immune privileged eye: pathogenic and regulatory T cells. Immunol. Res. 42, 41–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chan C. C., Caspi R. R., Roberge F. G., Nussenblatt R. B. (1988) Dynamics of experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis induced by adoptive transfer of S-antigen-specific T cell line. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 29, 411–418 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shao H., Liao T., Ke Y., Shi H., Kaplan H. J., Sun D. (2006) Severe chronic experimental autoimmune uveitis (EAU) of the C57BL/6 mouse induced by adoptive transfer of IRBP1–20-specific T cells. Exp. Eye Res. 82, 323–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Caspi R. R., Roberge F. G., McAllister C. G., el-Saied M., Kuwabara T., Gery I., Hanna E., Nussenblatt R. B. (1986) T cell lines mediating experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis (EAU) in the rat. J. Immunol. 136, 928–933 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Egwuagu C. E., Bahmanyar S., Mahdi R. M., Nussenblatt R. B., Gery I., Caspi R. R. (1992) Predominant usage of V β 8.3 T cell receptor in a T cell line that induces experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis (EAU). Clin.Immunol. Immunopathol. 65, 152–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shao H., Shi H., Kaplan H. J., Sun D. (2005) Chronic recurrent autoimmune uveitis with progressive photoreceptor damage induced in rats by transfer of IRBP-specific T cells. J. Neuroimmunol. 163, 102–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Caspi R. R. (2010) A look at autoimmunity and inflammation in the eye. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 3073–3083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Caspi R. R. (1999) Immune mechanisms in uveitis. Springer Semin.Immunopathol. 21, 113–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bianchi M. E., Manfredi A. A. (2007) High-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) protein at the crossroads between innate and adaptive immunity. Immunol. Rev. 220, 35–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Klune J. R., Dhupar R., Cardinal J., Billiar T. R., Tsung A. (2008) HMGB1: endogenous danger signaling. Mol. Med. 14, 476–484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bianchi M. E. (2009) HMGB1 loves company. J. Leukoc. Biol. 86, 573–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yu M., Wang H., Ding A., Golenbock D. T., Latz E., Czura C. J., Fenton M. J., Tracey K. J., Yang H. (2006) HMGB1 signals through Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 and TLR2. Shock 26, 174–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang H., Hreggvidsdottir H. S., Palmblad K., Wang H., Ochani M., Li J., Lu B., Chavan S., Rosas-Ballina M., Al-Abed Y., Akira S., Bierhaus A., Erlandsson-Harris H., Andersson U., Tracey K. J. (2010) A critical cysteine is required for HMGB1 binding to Toll-like receptor 4 and activation of macrophage cytokine release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 11942–11947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pisetsky D. S., Jiang W. (2007) Role of Toll-like receptors in HMGB1 release from macrophages. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1109, 58–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tang D., Kang R., Zeh H. J., III, Lotze M. T. (2011) High-mobility group box 1, oxidative stress, and disease. Antioxid. Redox. Signal 14, 1315–1335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tian J., Avalos A. M., Mao S. Y., Chen B., Senthil K., Wu H., Parroche P., Drabic S., Golenbock D., Sirois C., Hua J., An L. L., Audoly L., La R. G., Bierhaus A., Naworth P., Marshak-Rothstein A., Crow M. K., Fitzgerald K. A., Latz E., Kiener P. A., Coyle A. J. (2007) Toll-like receptor 9-dependent activation by DNA-containing immune complexes is mediated by HMGB1 and RAGE. Nat. Immunol. 8, 487–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Riuzzi F., Sorci G., Donato R. (2006) The amphoterin (HMGB1)/receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) pair modulates myoblast proliferation, apoptosis, adhesiveness, migration, and invasiveness. Functional inactivation of RAGE in L6 myoblasts results in tumor formation in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 8242–8253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yang H., Wang H., Czura C. J., Tracey K. J. (2005) The cytokine activity of HMGB1. J. Leukoc. Biol. 78, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Voll R. E., Urbonaviciute V., Furnrohr B., Herrmann M., Kalden J. R. (2008) The role of high-mobility group box 1 protein in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 10, 341–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Han J., Zhong J., Wei W., Wang Y., Huang Y., Yang P., Purohit S., Dong Z., Wang M. H., She J. X., Gong F., Stern D. M., Wang C. Y. (2008) Extracellular high-mobility group box 1 acts as an innate immune mediator to enhance autoimmune progression and diabetes onset in NOD mice. Diabetes 57, 2118–2127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Abdelsadik A., Trad A. (2011) Toll-like receptors on the fork roads between innate and adaptive immunity. Hum. Immunol. 72, 1188–1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Direskeneli H., Saruhan-Direskeneli G. (2003) The role of heat shock proteins in Behcet's disease. Clin. Exp.Rheumatol. 21, S44–S48 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liu-Bryan R., Terkeltaub R. (2010) Chondrocyte innate immune myeloid differentiation factor 88-dependent signaling drives procatabolic effects of the endogenous Toll-like receptor 2/Toll-like receptor 4 ligands low molecular weight hyaluronan and high mobility group box chromosomal protein 1 in mice. Arthritis Rheum. 62, 2004–2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wakefield D., Gray P., Chang J., Di G. N., McCluskey P. (2010) The role of PAMPs and DAMPs in the pathogenesis of acute and recurrent anterior uveitis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 94, 271–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen K., Huang J., Gong W., Iribarren P., Dunlop N. M., Wang J. M. (2007) Toll-like receptors in inflammation, infection and cancer. Int. Immunopharmacol. 7, 1271–1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Song P. I., Abraham T. A., Park Y., Zivony A. S., Harten B., Edelhauser H. F., Ward S. L., Armstrong C. A., Ansel J. C. (2001) The expression of functional LPS receptor proteins CD14 and Toll-like receptor 4 in human corneal cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 42, 2867–2877 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chang J. H., McCluskey P., Wakefield D. (2004) Expression of Toll-like receptor 4 and its associated lipopolysaccharide receptor complex by resident antigen-presenting cells in the human uvea. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 45, 1871–1878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chui J. J., Li M. W., Di G. N., Chang J. H., McCluskey P. J., Wakefield D. (2010) Iris pigment epithelial cells express a functional lipopolysaccharide receptor complex. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 51, 2558–2567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fujimoto T., Sonoda K. H., Hijioka K., Sato K., Takeda A., Hasegawa E., Oshima Y., Ishibashi T. (2010) Choroidal neovascularization enhanced by Chlamydia pneumoniae via Toll-like receptor 2 in the retinal pigment epithelium. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 51, 4694–4702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ko M. K., Saraswathy S., Parikh J. G., Rao N. A. (2011) The role of TLR4 activation in photoreceptor mitochondrial oxidative stress. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52, 5824–5835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jiang G., Ke Y., Sun D., Wang Y., Kaplan H. J., Shao H. (2009) Regulatory role of TLR ligands on the activation of autoreactive T cells by retinal astrocytes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50, 4769–4776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jiang G., Sun D., Kaplan H. J., Shao H. (2012) Retinal astrocytes pretreated with NOD2 and TLR2 ligands activate uveitogenic T cells. PLoS One 7, e40510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Luo C., Yang X., Kain A. D., Powell D. W., Kuehn M. H., Tezel G. (2010) Glaucomatous tissue stress and the regulation of immune response through glial Toll-like receptor signaling. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 51, 5697–5707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shao H., Lei S., Sun S. L., Kaplan H. J., Sun D. (2003) Conversion of monophasic to recurrent autoimmune disease by autoreactive T cell subsets. J. Immunol. 171, 5624–5630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jiang G., Ke Y., Sun D., Han G., Kaplan H. J., Shao H. (2008) Reactivation of uveitogenic T cells by retinal astrocytes derived from experimental autoimmune uveitis-prone B10RIII mice. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 49, 282–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ke Y., Jiang G., Sun D., Kaplan H. J., Shao H. (2009) Retinal astrocytes respond to IL-17 differently than retinal pigment epithelial cells. J. Leukoc.Biol. 86, 1377–1384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yang H., Ochani M., Li J., Qiang X., Tanovic M., Harris H. E., Susarla S. M., Ulloa L., Wang H., DiRaimo R., Czura C. J., Wang H., Roth J., Warren H. S., Fink M. P., Fenton M. J., Andersson U., Tracey K. J. (2004) Reversing established sepsis with antagonists of endogenous high-mobility group box 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 296–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chung K. Y., Park J. J., Kim Y. S. (2008) The role of high-mobility group box-1 in renal ischemia and reperfusion injury and the effect of ethyl pyruvate. Transplant. Proc. 40, 2136–2138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mollica L., De Marchis F., Spitaleri A., Dallacosta C., Pennacchini D., Zamai M., Agresti A., Trisciuoglio L., Musco G., Bianchi M. E. (2007) Glycyrrhizin binds to high-mobility group box 1 protein and inhibits its cytokine activities. Chem. Biol. 14, 431–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Watanabe T., Keino H., Sato Y., Kudo A., Kawakami H., Okada A. A. (2009) High mobility group box protein-1 in experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50, 2283–2290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Uzawa A., Mori M., Masuda S., Muto M., Kuwabara S. (2013) CSF high-mobility group box 1 is associated with intrathecal inflammation and astrocytic damage in neuromyelitis optica. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 84, 517–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wang H., Wang K., Wang C., Xu F., Zhong X., Qiu W., Hu X. (2013) Cerebrospinal fluid high-mobility group box protein 1 in neuromyelitis optica and multiple sclerosis. Neuroimmunomodulation 20, 113–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang K. C., Tsai C. P., Lee C. L., Chen S. Y., Chin L. T., Chen S. J. (2012) Elevated plasma high-mobility group box 1 protein is a potential marker for neuromyelitis optica. Neuroscience 226, 510–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang F., Lu Z., Hawkes M., Yang H., Kain K. C., Liles W. C. (2010) Fas (CD95) induces rapid, TLR4/IRAK4-dependent release of pro-inflammatory HMGB1 from macrophages. J. Inflamm. (Lond). 7, 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Su Z., Sun C., Zhou C., Liu Y., Zhu H., Sandoghchian S., Zheng D., Peng T., Zhang Y., Jiao Z., Wang S., Xu H. (2011) HMGB1 blockade attenuates experimental autoimmune myocarditis and suppresses Th17-cell expansion. Eur. J. Immunol. 41, 3586–3595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. He Z., Shotorbani S. S., Jiao Z., Su Z., Tong J., Liu Y., Shen P., Ma J., Gao J., Wang T., Xia S., Shao Q., Wang S., Xu H. (2012) HMGB1 promotes the differentiation of Th17 via up-regulating TLR2 and IL-23 of CD14+ monocytes from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Scand. J. Immunol. 76, 483–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wild C. A., Bergmann C., Fritz G., Schuler P., Hoffmann T. K., Lotfi R., Westendorf A., Brandau S., Lang S. (2012) HMGB1 conveys immunosuppressive characteristics on regulatory and conventional T cells. Int. Immunol. 24, 485–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kao K. K., Fink M. P. (2010) The biochemical basis for the anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective actions of ethyl pyruvate and related compounds. Biochem. Pharmacol. 80, 151–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kalariya N. M., Reddy A. B., Ansari N. H., Vankuijk F. J., Ramana K. V. (2011) Preventive effects of ethyl pyruvate on endotoxin-induced uveitis in rats. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52, 5144–5152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Devamanoharan P. S., Henein M., Ali A. H., Varma S. D. (1999) Attenuation of sugar cataract by ethyl pyruvate. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 200, 103–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fang J., Fang D., Silver P. B., Wen F., Li B., Ren X., Lin Q., Caspi R. R., Su S. B. (2010) The role of TLR2, TRL3, TRL4, and TRL9 signaling in the pathogenesis of autoimmune disease in a retinal autoimmunity model. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 51, 3092–3099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Su S. B., Silver P. B., Grajewski R. S., Agarwal R. K., Tang J., Chan C. C., Caspi R. R. (2005) Essential role of the MyD88 pathway, but nonessential roles of TLRs 2, 4, and 9, in the adjuvant effect promoting Th1-mediated autoimmunity. J. Immunol. 175, 6303–6310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]