Abstract

Vanishing bile duct syndrome (VBDS) is a condition resulting from severe bile duct injury, progressive destruction, and disappearance of intrahepatic bile ducts (ductopenia) leading to cholestasis, biliary cirrhosis, and liver failure. VBDS can be associated with a variety of disorders, including Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL). We describe a 33-year-old male patient who presented with lymphadenopathy and jaundice, and was diagnosed to have HL. Serum bilirubin worsened progressively despite chemotherapy, with a cholestatic pattern of liver enzymes. Diagnosis of VBDS was established on liver biopsy. Although remission from HL was achieved, the patient died of liver failure. Presence of jaundice in HL patients should raise the possibility of VBDS. This report discusses the difficulties of delivering chemotherapy in patients with liver dysfunction. HL-associated VBDS carries a high mortality but lymphoma remission can be achieved in some patients. Therefore, liver transplantation should be considered early in these patients.

Keywords: Chemotherapy, Hodgkin's lymphoma, vanishing bile duct syndrome

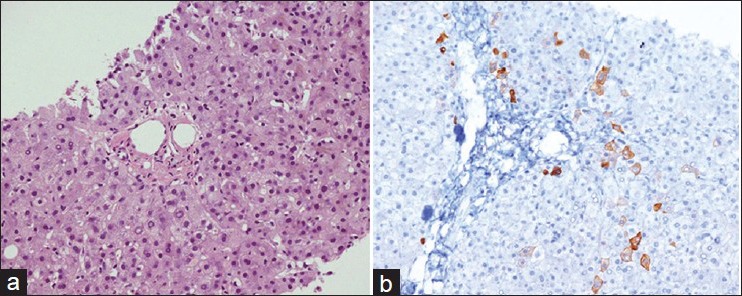

Vanishing bile duct syndrome (VBDS) refers to a cluster of disorders leading to progressive destruction and disappearance of intrahepatic bile ducts (ductopenia) and ultimately, cholestasis.[1] Consequently, ductopenia is defined as a loss of interlobular bile ducts in more than 50% of small portal tracts in pathological specimens with at least 10 portal tracts.[1,2] In patients with bile duct loss secondary to drug-induced injury, the bile ducts can regenerate and be redistributed in the liver (reversible). In other types of bile duct injury, however, the loss is progressive and is followed by VBDS, leading to biliary cirrhosis and liver failure.[1] VBDS can be associated with a variety of disorders, including Hodgkin's lymphoma [Table 1].

Table 1.

Some of the conditions associated with VBDS

Cholestasis with bile duct loss is a well recognized but rare presentation of Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL).[2,3] The appropriate management of VBDS associated with HL remains controversial, as both conventional chemotherapy and alternative regimens have been reported to be successful in achieving remission in this condition.[4,5,6,7] Despite adequate treatment, a high mortality rate is reported and many of these patients die of liver failure rather than lymphoma progression. This explains the difficulties encountered in the administration of potential hepatotoxic chemotherapy in severely cholestatic patients.[3,6]

CASE REPORT

A previously healthy 33-year-old Saudi man was admitted with a progressive left-sided neck swelling for 1 year. He developed yellowish discoloration of the skin and sclera, pale stools, and dark urine associated with abdominal distension 1 week prior to admission. He also complained of unexplained weight loss of 8 kg, low-grade fever, and fatigability. There was no history of liver disease or use of any herbs or other medication. Physical examination revealed pallor, jaundice, and a nontender, firm lymph node in the neck measuring 5 × 5 cm with unremarkable examination of other systems.

Complete blood count showed mild leukopenia with a total WBC count of 3.1 × 109/L (normal 4-11), neutrophils 2 × 109/L, lymphocytes 0.7 × 109/L, mild normocytic normochromic anemia (Hb 12.6 g/dL), and a normal platelet count. Liver function tests (LFT) revealed a predominant cholestatic pattern with a total bilirubin (TBil) of 88 μmol/L (normal up to 18 μmol/L), direct bilirubin 74 umol/L, alkaline phosphatase 524 U/L, gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) 518 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 194 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase 106 U/L, and serum albumin 42 g/L. His renal function tests were normal and autoimmune work up was negative. Virology screening revealed negative results for hepatitis A, B, C, HIV, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and cytomegalovirus (CMV).

Abdominal ultrasound showed a normal-sized liver (13 cm) with multiple hyper-echoic lesions seen in both lobes; the largest one in the left lobe (3.8 × 2.7 cm), and mild splenomegaly (14.9 cm). Common bile duct (CBD), portal vein, and hepatic veins were normal. Baseline computed tomography (CT) scan of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed multiple lymph nodes in the left side of the neck (largest 4.8 × 4.1 cm), left supraclavicular, mediastinal, both hilar areas, and intra-abdominal regions, suggestive of lymphoma. In addition, at least three hypodense focal hepatic lesions were present (largest 4 × 3.6 cm) with features suggestive of hemangiomas. Other findings were noncontributory.

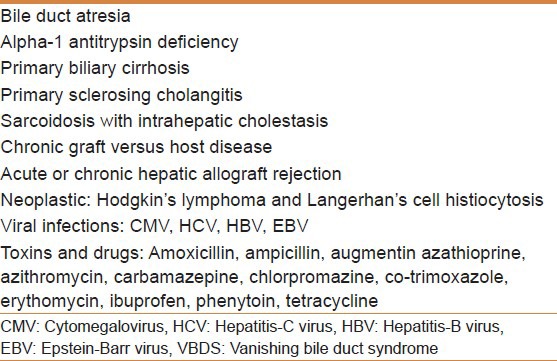

The patient underwent left cervical lymph node excisional biopsy, which showed classical HL of nodular sclerosis type [Figure 1] with a positive immunohistochemical staining for CD 30 and CD 15 but negative for CD 45 and CD 20. Bone marrow biopsy showed no evidence of lymphoma infiltration, so he was staged as III-B.

Figure 1.

Photomicrograph of the lymph node biopsy (a) showing nodular sclerosis type of Hodgkin's lymphoma (H and E, ×20) and (b) high power view showing Reid–Sternberg cells (H and E, ×40)

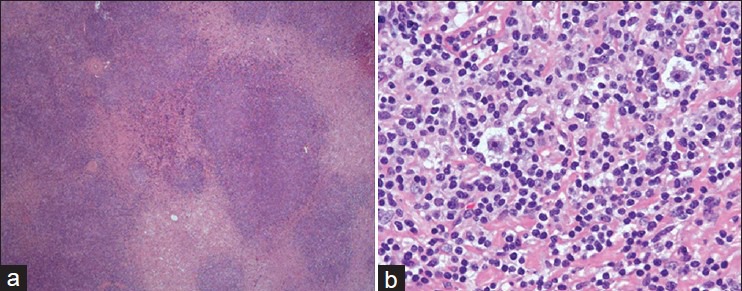

The patient received first cycle of chemotherapy, ABVD regimen (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine) with 30% dose reduction due to liver dysfunction. His jaundice improved initially but after 1 week he presented again with generalized weakness, anorexia, nausea, and worsening of jaundice. Repeat liver function tests revealed deterioration with elevated bilirubin (159 μmol/L) and liver enzymes consistent with a cholestatic pattern. There was no evidence of intrahepatic biliary dilatation on ultrasound. He underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), which showed normal CBD and a sphincterotomy and insertion of a biliary stent were performed. No improvements in liver function were noted so an ultrasound-guided liver biopsy was performed, which revealed cholestasis and nonspecific portal inflammation with no evidence of lymphoma. CK7 staining showed significantly reduced number of bile ducts consistent with a diagnosis of VDBS [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Liver biopsy specimen (a) with a portal tract almost devoid of bile ducts (H and E, ×20) and (b) absence of CK7 staining consistent with bile duct loss (×20)

In view of the persistent liver dysfunction, the patient received a modified ESHAP chemotherapy regimen (methylprednisolone 250 mg IV daily for 4 days, cisplatin 25 mg/m2 IV continuous infusion for 4 days and cytarabine 2 g/m2 IV on day 5 but without etoposide) because of the liver friendly nature of this regimen to prevent any further liver damage. The patient remained jaundiced with TBil fluctuating between 400 and 600 μmol/L, although a drop in TBil was noted (232 μmol/L) for a brief period. A repeat CT scan performed after the second chemotherapy cycle revealed significant regression of the lymph nodes in the neck, supraclavicular, mediastinal and retroperitoneal areas.

At this stage he received the second cycle of modified ESHAP chemotherapy (3rd cycle in total) but with a higher dose of methylprednisolone (500 mg daily for 4 days). After 2 weeks, he developed febrile neutropenia with positive blood cultures for Klebsiella species. He was treated with broad spectrum antibiotics. He also sustained drug-induced acute kidney injury, which improved initially but serum creatinine remained elevated, which hindered administration of further chemotherapy. His liver function showed no improvement. A positron emission tomography-CT of the whole body did not show significant fluorodeoxyglucose activity suggesting remission of HL. He was referred for a liver transplant but his condition rapidly deteriorated. He developed severe coagulopathy and hepatic encephalopathy, and died 4 months after the initial diagnosis of HL.

DISCUSSION

Cholestasis in HD can be explained by several possible mechanisms, including direct hepatic infiltration, which can be gross or microscopic, biliary obstruction (usually by enlarged hilar lymph nodes), and less commonly nonspecific causes such as viral hepatitis and drug toxicity.[1,8] Liver infiltration by lymphoma cells in HL is seen in up to 50% of patients on autopsy studies but it is uncommon to recognize hepatic involvement by liver biopsy during life.[4] Ever since Hubscher et al. reported VBDS in three cases with HL, VBDS has become a well-recognized but rarely seen entity in HL.[2,3] VBDS can be diagnosed when intrahepatic cholestasis is associated with a loss of interlobular bile ducts (ductopenia) on histopathology after exclusion of other causes.[1,2] The pathogenesis of VBDS in HL is not clear. One theory implicates cell-mediated immunologic attack by cytotoxic T-lymphocytes causing ductal destruction, whereas an alternate theory suggests that toxic cytokines from the lymphoma cells are responsible for the ductopenia.[1,9]

Our patient presented with cholestatic jaundice and lymphadenopathy, and the liver biopsy findings were consistent with VBDS. We considered a wide variety of conditions in the differential diagnosis including veno-occlusive disease, but the clinical, radiological, and liver biopsy findings were not consistent with any of these diagnoses. Although most of the causes of cholestasis were excluded, liver infiltration with HL cannot be ruled out, and may have disappeared after chemotherapy. While the patient showed a modest but favorable initial response to treatment, he may have suffered further liver damage by chemotherapy and succumbed to liver failure. Treating patients with HL-related VBDS is challenging because of the difficulties in administering chemotherapy to a patient with severe liver dysfunction and few published data to guide the management of this rare condition. In a review of all published cases of HL-associated VBDS and idiopathic cholestasis, 65% of the patients died, most of them (87%) with liver failure.[3] This shows that lymphoma remission can be achieved, at least in some patients, with alternative and modified chemotherapy protocols.[3,5,6,7]

HL is quite radiosensitive and the possibility of upfront treatment with radiation therapy is of potential interest in the setting of severe cholestasis, although this may be applicable only to limited stage HL. In a recent review of HL and VBDS, Ballonoff and colleagues reported that patients who received radiotherapy had an improved liver-failure-free survival as compared with those who did not receive it.[3] As the liver damage is related to lymphoma presence and VBDS may be potentially reversible in some patients, it is extremely important to achieve early lymphoma remission to stop further liver damage.[3]

VBDS represents a severe form of liver injury with high mortality and previous authors have recommended to consider liver transplant (LT), although there are hardly any reports of LT in this setting.[2,3] Patients should be referred early for LT after the establishment of VBDS diagnosis, although it is difficult to consider LT unless the remission from HL is confirmed. It appears that early measures should be taken to prepare for LT and aggressive measures taken to put the patient in HL remission, so as soon as the remission is achieved, patient can undergo LT. Our patient did achieve remission from HL but there was no time for LT.

CONCLUSION

The presence of jaundice in HL patients should raise the possibility of VBDS. HL-associated VBDS carries a high mortality but remission can be achieved in some patients. Therefore, liver transplantation should be considered early in these patients.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nakanuma Y, Tsuneyama K, Harada K. Pathology and pathogenesis of intrahepatic bile duct loss. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2001;8:303–15. doi: 10.1007/s005340170002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hubscher SG, Lumley MA, Elias E. Vanishing bile duct syndrome: A possible mechanism for intrahepatic cholestasis in Hodgkin's lymphoma. Hepatology. 1993;17:70–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballonoff A, Kavanagh B, Nash R, Drabkin H, Trotter J, Costa L, et al. Hodgkin lymphoma-related vanishing bile duct syndrome and idiopathic cholestasis: Statistical analysis of all published cases and literature review. Acta Oncol. 2008;47:962–70. doi: 10.1080/02841860701644078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghobrial IM, Wolf RC, Pereira DL, Fonseca R, White WL, Colgan JP, et al. Therapeutic options in patients with lymphoma and severe liver dysfunction. Ther Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:169–75. doi: 10.4065/79.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leeuwenburgh I, Lugtenburg EP, van Buuren HR, Zondervan PE, de Man RA. Severe jaundice, due to vanishing bile duct syndrome, as presenting symptom of Hodgkin's lymphoma, fully reversible after chemotherapy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:145–7. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282b9e6c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pass AK, McLin VA, Rushton JR, Kearney DL, Hastings CA, Margolin JF. Vanishing bile duct syndrome and Hodgkin's disease: A case series and review of the literature. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2008;30:976–80. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31818b37c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCarthy J, Gopal AK. Successful use of full-dose dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin as part of initial therapy in non-hodgkin and hodgkin lymphoma with severe hepatic dysfunction. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2009;9:167–70. doi: 10.3816/CLM.2009.n.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birrer MJ, Young RC. Differential diagnosis of jaundice in lymphoma patients. Semin Liver Dis. 1987;3:269–77. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1040582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barta SK, Yahalom J, Shia J, Hamlin PA. Idiopathic cholestasis as a paraneoplastic phenomenon in Hodgkin's lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2006;7:77–82. doi: 10.3816/CLM.2006.n.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]