Abstract

Pet assisted therapy (PAT) is a form of complementary psychosocial intervention used in the field of mental health and disability. The form of therapy has the potential to augment the other forms of psychotherapies and pharmacotherapy. This article is an overview of history and clinical origins of PAT, classification and therapy models, scientific basis, the current use in specific disorders, preventive and diagnostic role as well as the potential risks among children and adolescents with mental health needs with a special focus on the Indian needs. A systematic electronic search strategy was undertaken to identify the intervention effectiveness of PAT in MedLine (PubMed), cochrane database of systematic reviews, high-wire press and Google Scholar. We augmented our electronic search with a search of additional articles in reference lists of retrieved articles, as well as a hand search available journals that were not indexed in any electronic database in consultation with colleagues and experts. To qualify for inclusion, studies were required to meet predetermined criteria regarding study design, study population, interventions evaluated and outcome measured to reduce the publication bias.

Keywords: Adolescent, child, India, pet, therapy

INTRODUCTION

In the field of psychosocial interventions, pet assisted therapy (PAT) is being recognized as a legitimate means of assisting children with psychiatric disorders in the Western countries. Pets have been identified as a component of the milieu, as a friend and as a therapist in therapeutic contexts for children[1] that can naturally stimulate an attraction and involvement response in humans.[2] This review will summarize the history and origins of PAT, the physiological and psychological basis for adapting animal-human relationship as a useful therapy model, the therapeutic processes, as well as an indication in specific child and adolescent psychiatric disorders.

METHODS USED FOR LOCATING, SELECTING, EXTRACTING AND SYNTHESIZING DATA

A systematic electronic search strategy was undertaken to identify the intervention effectiveness of PAT in MedLine (PubMed), cochrane database of systematic reviews, high-wire press and Google Scholar. The MeSH word “animal assisted therapy” was combined with “child” and “adolescence.” We augmented our electronic search with a search of additional articles in reference lists of retrieved articles, as well as a hand search available journals that were not indexed in any electronic database in consultation with colleagues and experts. Potentially relevant articles were then screened by at least two independent reviewers; disagreements were resolved by discussion or upon consensus from the third reviewer. To qualify for inclusion, studies were required to meet predetermined criteria regarding study design, study population, interventions evaluated and outcome measured to reduce the publication bias. Furthermore, in cases of multiple publications of the same or overlapping study, only the studies with the largest sample size were included.

HISTORY AND ORIGINS OF PAT

Indian mythology abounds in stories depicting the closeness between animals and humans, not to mention that often gods resemble animals and bear their characteristics or even transformation of humans into animals and vice versa or speaking to humans thus underscoring the strong need to have a loyal animal-human relationship. For example, Yudhisthira's dog-companion conquered the obstacles of Himalayas to reach the heaven's gate with his master in Mahabaratha and Lord Dattatreya, the God of education, being accompanied by four dogs representing the four Vedas are in stark contrast to the contemporary reality in India, alluring us to look back at these relationship and build a therapy based on it.

ORIGINS OF PAT

The earliest use of pet animals for therapeutic use was in Belgium in the middle ages, where pets and people were rehabilitated together, with pets providing a part of the natural therapy for the humans. Following this The York Retreat in Germany and Bethel for the mentally ill and the homeless included animals, as a part of the therapeutic milieu reaping the benefits. Later, the Human Animal Bond was conceptualized by a Psychologist, Boris Levinson and Konrad Lorenz, an Austrian Nobel laureate in Physiology. This bond is explained as an intrinsic need in humans to bond with nature, especially in the background of their chaotic lives. The modern movement of using companion animals as a means of therapy had a multidisciplinary origin, involving the fields of veterinary medicine, psychology, sociology, psychiatry funded by pet food industry.

CLASSIFICATION AND MODELS

PAT is classified based on the function it serves or environment the pet is introduced into. Interventions using animals has evolved into pet visitation, animal-assisted therapy, hippo therapy and therapeutic horseback riding. The simplest form of PAT has been pet visitation, focused on fostering rapport and initiating communication. In this type of intervention, the animal initiated contact and the individual determine the direction of the visit. Pet visitation led to animal-assisted therapy, a goal directed intervention in which an animal meeting specific criteria becomes an integral part of the treatment process or treatment team.

Pets have been used in for therapies on a residential and visitation basis for structured or unstructured interactions. In the residential model pets permanently stay with children with chronic psychiatric disorders requiring long-term care[3] and in the more often adopted visitation models pets visits their clients periodically.[4] The efficacy of both these models have compared and have been documented to have equal therapeutic benefit.[5]

PHYSIOLOGICAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL RESPONSES TO PETS

Positive interactions with animals have been proven to induce release of endorphins, decrease in blood pressure and improve lipid profile as well as survival of patients following cardiac surgery is longer if they owned a pet.[6] Among the myriad of psychological functions that the pet serve, providing companionship, stress relief, emotional comfort and substitute for human company across age groups are notable. Lower levels of depression, better self-image, improved socialization, mental functioning and improve quality-of-life associated with positive human-pet interaction have also been noted in the literature.[7] These beneficial effects of pet interactions to reduce the response to stressful situations have been documented in those who may not own animals.[8]

PETS FOR CLINICAL INTERVENTION

Considering these health enhancing physiological and psychological responses, it is only natural that PAT has been used for: Fostering socialization, increasing a withdrawn Person's responsiveness and animation, giving pleasure, promotes humor, enhancing morale, fulfilling needs to nurture and be nurtured, enhancing the treatment setting, reducing dependence on psychotropic medications and help keep individuals in touch with reality by providing forms of sensory stimulation, as well as increased social interactions.[9,10] Furthermore, bonding with animals has been associated with increased feelings of security and with increased likelihood of regular exercise.[11]

PSYCHOTHERAPEUTIC PROCESS

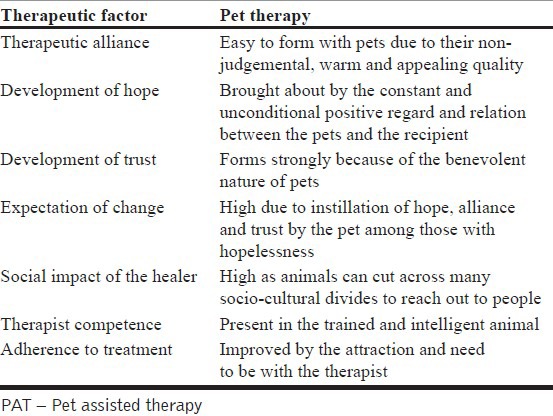

Although there are no hard and fast guidelines for the structure and the process involved in the PAT,[9] recently guidelines are being developed primarily by hospitals for this modality of therapeutic approach. Firstly, by definition PAT, delivered or directed by a human service professional in groups or individual therapeutic settings, should be designed to promote physical, social, emotional and cognitive well-being of the human client. Secondly while considering the role of animals in PAT, these animals should be differentiated from animals for entertainment (for example circus animal) or generalized benefits (for example sniffer dogs), or animals-assisted activities (for example guide dogs). Finally, another gain of PAT in clinical contexts has not only been the clients but also service providers by demonstrating a reduction in their stress and burnout, when they are involved in long-term therapies for chronic conditions.[12] The psychotherapeutic processes that bring about therapeutic changes in PAT are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Psychotherapeutic processes in PAT

SPECIFIC PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS

Autism

In children with autism spectrum disorders, contact with animals, especially dogs, has led to greater attention and ability to focus on tasks at hand or people. Increase in other pro-social behavior has been reported in recent controlled trials using pet animals among children with autism.[13] Increased happiness and better communication related to the therapy was noticed in the presence of a dog when compared with a stuffed dog or other inanimate toys although some increase in hand flapping, probably as a sign of excitement was present in the presence of a dog.[14] Equine assisted therapy has shown a reduction in autistic symptom rating scale in recent prospective studies.[15,16] The use of dolphins in the treatment of autistic spectrum disorders is an emerging approach and needs further exploration in autism.[16]

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

Pilot studies in this area report promising changes in social role behavior, quality-of-life and control of motor performance among children with ADHD.[17]

Child abuse

In children who had undergone abuse, pets were found to reduce trauma symptoms significantly[18] and may help in blocking intergenerational transmission of abuse.[19]

Grief

Animals as a part of grief and disaster related therapy were effective in several significant ways including, providing comfort and nurturance, relieving anxiety and tension and facilitating the sharing of emotional responses and trauma stories.[20]

Dementia

Among nursing home residents, pet visitations were found to improve health self-concept, social competence and interest, psychosocial functioning, life satisfaction, personal neatness and mental function[7] among healthy elderly nursing home residents and among those with dementia.[5] Residents with Alzheimer's disorder in a veterans’ home were observed to have enhanced social behaviors such as: Smiles, laughs, looks, leans, touches, verbalizations, name-calling and others in the presence of pets.

Chronic physical disability

In children with cerebral palsy, with hippo therapy (physical therapy utilizing the movement of a horse), significant improvement in symmetry of muscle activity was noted in those muscle groups displaying the highest asymmetry prior to hippo therapy. In the control group, no significant change was noted after sitting astride a barrel.[21,22]

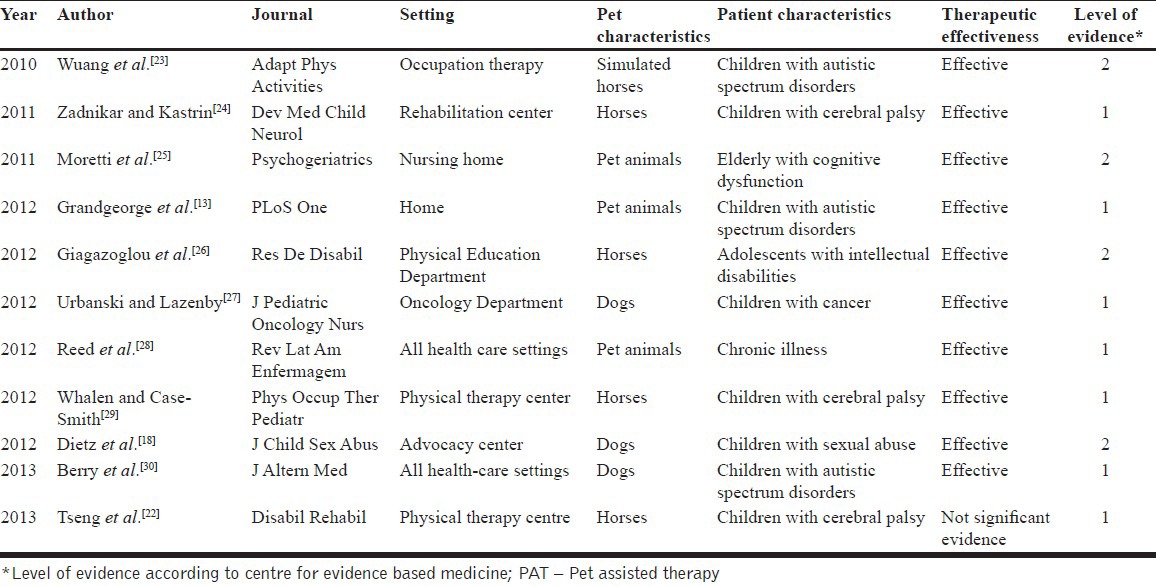

In addition, PAT based interactions can predict certain aberrant behaviors among children and adolescents namely, pet abuse may indicate children exposed to abuse and chaotic home situations or even future aggression toward human beings suggesting a need for early mental health interventions. Details of the evidence base for therapeutic effectiveness of PAT over the past 5 years are mentioned in Table 2.

Table 2.

Review of reviews and randomized control trials on PAT for the past 5 years published in English

PITFALLS

The clinical use of the PAT may not be fully harnessed because of the fear associated with injury caused by animals or spiritual stigma and fear of transmission of zoonotic diseases among the clients. From a research perspective, obtaining permission from the staff and management of the health-care facility, ensuring animal board permission about using the animal for therapy, logistical problems with transporting the animals, need for professional animal handlers, availability of docile, well-socialized and healthy therapy animals have been reported as barriers to PAT.

CONCLUSION

PAT is a new form complimentary intervention in child and adolescent mental health field with a lot of promise to help those with neuro-developmental as well as emotional and behavioral disorders. Family and community pets may have a role to play in countries like India where there is a paucity of human resources for health. Well-designed research data are warranted in this discipline of therapy.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bardill N, Hutchinson S. Animal-assisted therapy with hospitalized adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 1997;10:17–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.1997.tb00208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brodie SJ, Biley FC. An exploration of the potential benefits of pet-facilitated therapy. J Clin Nurs. 1999;8:329–37. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.1999.00255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall PL, Malpus Z. Pets as therapy: Effects on social interaction in long-stay psychiatry. Br J Nurs. 2000;9:2220–5. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2000.9.21.5425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaiser L, Spence LJ, McGavin L, Struble L, Keilman L. A dog and a “happy person” visit nursing home residents. West J Nurs Res. 2002;24:671–83. doi: 10.1177/019394502320555412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kongable LG, Buckwalter KC, Stolley JM. The effects of pet therapy on the social behavior of institutionalized Alzheimer's clients. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1989;3:191–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson WP, Reid CM, Jennings GL. Pet ownership and risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Med J Aust. 1992;157:298–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Francis G, Turner JT, Johnson SB. Domestic animal visitation as therapy with adult home residents. Int J Nurs Stud. 1985;22:201–6. doi: 10.1016/0020-7489(85)90003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neer CA, Dorn CR, Grayson I. Dog interaction with persons receiving institutional geriatric care. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1987;191:300–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barba BE. The positive influence of animals: Animal-assisted therapy in acute care. Clin Nurse Spec. 1995;9:199–202. doi: 10.1097/00002800-199507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Savishinsky JS. Intimacy, domesticity and pet therapy with the elderly: Expectation and experience among nursing home volunteers. Soc Sci Med. 1992;34:1325–34. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90141-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Willis DA. Animal therapy. Rehabil Nurs. 1997;22:78–81. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.1997.tb01738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carmack BJ, Fila D. Animal-assisted therapy: A nursing intervention. Nurs Manage. 1989;20:96. 98, 100-1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grandgeorge M, Tordjman S, Lazartigues A, Lemonnier E, Deleau M, Hausberger M. Does pet arrival trigger prosocial behaviors in individuals with autism? PLoS One. 2012;7:e41739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin F, Farnum J. Animal-assisted therapy for children with pervasive developmental disorders. West J Nurs Res. 2002;24:657–70. doi: 10.1177/019394502320555403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kern JK, Fletcher CL, Garver CR, Mehta JA, Grannemann BD, Knox KR, et al. Prospective trial of equine-assisted activities in autism spectrum disorder. Altern Ther Health Med. 2011;17:14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salgueiro E, Nunes L, Barros A, Maroco J, Salgueiro AI, Dos Santos ME. Effects of a dolphin interaction program on children with autism spectrum disorders: An exploratory research. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:199. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cuypers K, De Ridder K, Strandheim A. The effect of therapeutic horseback riding on 5 children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A pilot study. J Altern Complement Med. 2011;17:901–8. doi: 10.1089/acm.2010.0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dietz TJ, Davis D, Pennings J. Evaluating animal-assisted therapy in group treatment for child sexual abuse. J Child Sex Abus. 2012;21:665–83. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2012.726700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parish-Plass N. Animal-assisted therapy with children suffering from insecure attachment due to abuse and neglect: A method to lower the risk of intergenerational transmission of abuse? Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;13:7–30. doi: 10.1177/1359104507086338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shubert J. Therapy dogs and stress management assistance during disasters. US Army Med Dep J. 2012;2:74–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benda W, McGibbon NH, Grant KL. Improvements in muscle symmetry in children with cerebral palsy after equine-assisted therapy (hippotherapy) J Altern Complement Med. 2003;9:817–25. doi: 10.1089/107555303771952163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tseng SH, Chen HC, Tam KW. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of equine assisted activities and therapies on gross motor outcome in children with cerebral palsy. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35:89–99. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2012.687033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wuang YP, Wang CC, Huang MH, Su CY. The effectiveness of simulated developmental horse-riding program in children with autism. Adapt Phys Activ Q. 2010;27:113–26. doi: 10.1123/apaq.27.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zadnikar M, Kastrin A. Effects of hippotherapy and therapeutic horseback riding on postural control or balance in children with cerebral palsy: A meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53:684–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.03951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moretti F, De Ronchi D, Bernabei V, Marchetti L, Ferrari B, Forlani C, et al. Pet therapy in elderly patients with mental illness. Psychogeriatrics. 2011;11:125–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-8301.2010.00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giagazoglou P, Arabatzi F, Dipla K, Liga M, Kellis E. Effect of a hippotherapy intervention program on static balance and strength in adolescents with intellectual disabilities. Res Dev Disabil. 2012;33:2265–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Urbanski BL, Lazenby M. Distress among hospitalized pediatric cancer patients modified by pet-therapy intervention to improve quality of life. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2012;29:272–82. doi: 10.1177/1043454212455697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reed R, Ferrer L, Villegas N. Natural healers: A review of animal assisted therapy and activities as complementary treatment for chronic conditions. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2012;20:612–8. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692012000300025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whalen CN, Case-Smith J. Therapeutic effects of horseback riding therapy on gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2012;32:229–42. doi: 10.3109/01942638.2011.619251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berry A, Borgi M, Francia N, Alleva E, Cirulli F. Use of assistance and therapy dogs for children with autism spectrum disorders: A critical review of the current evidence. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;19:73–80. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]