Abstract

Purpose:

Listeria monocytogenes is an aerobic, motile, gram positive bacillus recognized as an intercellular pathogen in human where it most frequently affects neonates, pregnant women, elderly patients, and immunosuppressed individuals as well as healthy persons. Ocular listeriosis is rare, most frequently in the form of conjunctivitis, but has been also shown to cause rarely endophthalmitis with pigmented hypopyon and elevated intraocular pressure such as in our case.

Materials and Methods:

We are reporting one immunocompetent patient presenting with dark hypopyon following laser refractive procedure. His clinical findings, investigations, and further management are all described with relevant literature review of similar cases.

Results:

Diagnosis of ocular listeriosis was confirmed by positive culture of anterior chamber (AC) aspirate with identification of the above organism. His visual outcome was satisfactory with good preserved vision.

Conclusion:

We believe that his ocular infection was exogenous and that ophthalmologists should be aware of the causative organisms of colored hypopyon to avoid delayed diagnosis.

Keywords: Endophthalmitis, Laser-assisted in situ Keratomileusis, Listeria, Pigmented Hypopyon

INTRODUCTION

Listeria monocytogenes is an aerobic, motile, gram positive bacillus recognized as an intercellular pathogen in human. Food-borne transmission has been identified in epidemic and sporadic human listeriosis.1 Infections most frequently affect neonates, pregnant women, elderly patients, and immunosuppressed individuals. However, it can also occur in healthy persons.1

Ocular listeriosis is generally rare, most frequently in the form of conjunctivitis. Other ophthalmic presentations include keratitis.1,2,3 In such cases, misdiagnosis as diphtheroids species is possible.4 It has been also shown that listeriosis can rarely cause endopthalmitis.5,6

CASE REPORT

A 28-year-old male presented to the emergency room (ER) with pain and redness in the right eye over the last 5 days. He was otherwise healthy and gave a past history of appendicectomy. His ocular history revealed laser refractive surgery procedure in both eyes 6 months prior to his presentation in another institution in Jordan. His history also revealed prior recent admission to a local hospital where he was found to have a high intraocular pressure of 50 mmHg which was managed by antiglaucoma medications: Latanoprost (Xalatan by Allergan) drops. He also received fortified antibiotics and topical steroids. No exact details of his treatment were available at the time of his presentation to our ER facility. He presented with vision of hand motion in the affected eye and intraocular pressure of 18 mmHg. His slit lamp examination of the right eye revealed severe conjunctival congestion with ciliary injection, opaque hazy cornea, and deep anterior chamber (AC) with 3 mm of dark pigmented hypopyon. There was no localized corneal infiltrate, but ring deep corneal dense haze was noticed possibly representing the edges of a previous laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) flap [Figure 1a and b]. There was no further view of the posterior cavity. The left eye examination was within normal limits.

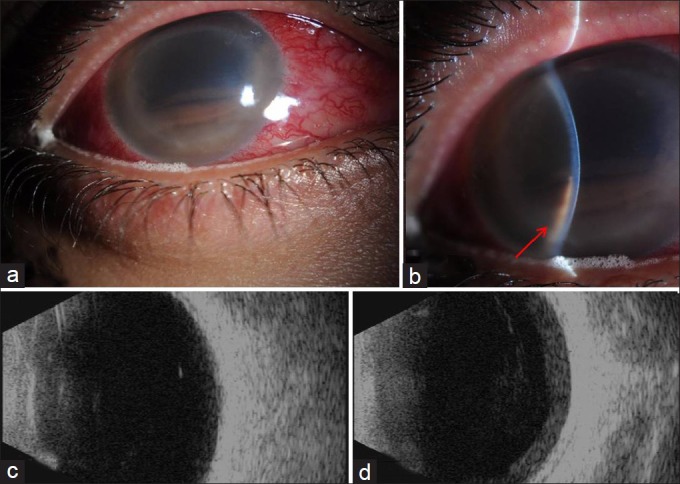

Figure 1.

(a and b) The clinical appearance of the patient's right eye at presentation with ciliary injection, dark hypopyon and stromal haze (red arrow in 1b). (c and d) His B-scans showing no evidence of endophthalmitis on initial scan (c) then increasing vitreous opacities and RC layer thickening with suspected endophthalmitis on repeated examination (d)

The patient was admitted as a case of uveitis. His initial B-scan showed very mild vitreous opacity and no RC layer thickening, therefore was not considered to be typical of endophthalmitis [Figure 1c]. However, he was continued on fortified antibiotic drops (vancomycin 25 mg/ml and ceftazidime 50 mg/ml every 3 h around the clock, OD) and topical steroids: Prednisolone (Predforte by Allergan) drops four times/day, OD.

His differential diagnosis included post-refractive herpetic keratouveitis and masquerade syndrome. He was started on valtrex 500 mg twice daily, orally, in addition to the moxifloxacin 400 mg orally once daily. He was also kept on antiglaucoma medication: Combination of dorzolamide and timolol (Xolomol by Jamjoom Pharma) drops twice daily, OD.

His repeated B scans over 4 days following admission revealed increasingly dense organized vitreous opacities and significant retina and choroid (RC) layer thickening suggestive of early endophthalmitis [Figure 1d] for which AC washout, vitreous tap and intravitreal antibiotics were given in the form of vancomycin 1 mg/0.1 ml, ceftazidime 2.25 mg/0.1 ml, and cefuroxime 1 mg/0.1 ml. Meanwhile his systemic investigations were within normal limits. His human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing, urine, and blood cultures were negative. His chest X-ray was clear.

The smears prepared from his AC washout showed necrotic debris insterspersed with both extra- and intracellular melanin granules. Moderate number of polymorphonuclear leukocytes were also present [Figure 2a]. The Grocott's methenamine silver (GMS), gram, and acid-fast stains were all negative. No malignant cells were seen to suggest a masquerade syndrome. The AC aqueous was sent for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to rule out infectious etiology including herpetic infection, cytomegalovirus, varicella zoster, tuberculosis, and Chlamydia which were all negative. The aqueous fluid culture proved bacterial growth identified as Listeria monocytogenes in the blood agar plate [Figure 2b] and brain heart infusion (BHI) broth. The organism was sensitive to gentamicin and penicillin G. The culture of the vitreous fluid showed few gram positive bacilli which were not further identified. Valtrex and moxifloxacin were stopped and the patient was given intravenous penicillin G 15 million units every 6 h (following a negative skin test) for 2 weeks and then shifted to oral augmentin 1 g twice daily for another 2 weeks.

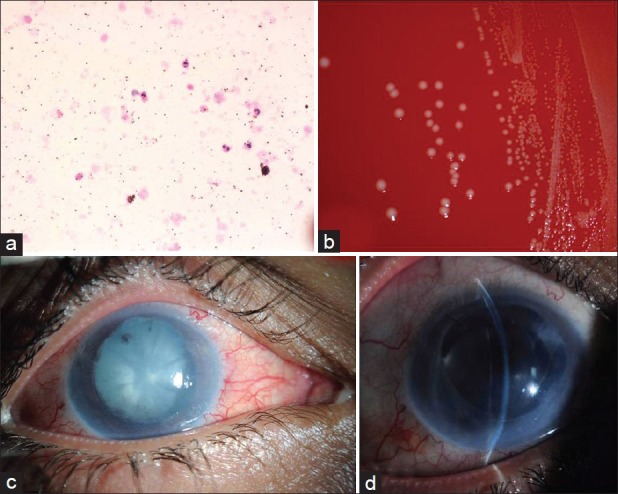

Figure 2.

(a) Histologic smear of the aqueous showing the predominant polymorphonuclear leukocytes (hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification ×400). (b) Blood agar plate showing the bacterial colonies with surrounding beta hemolysis. (c) The clinical appearance of the right eye cataract and posterior synechiae. (d) Postoperative slit-lamp photo of his right eye with intraocular lens (IOL) in the capsular bag

The patient subsequently developed cataract for which he underwent phacoemulsification with posterior chamber intraocular lens (PC-IOL) implantation 4 weeks after his admission [Figure 2c]. Another AC fluid was sent for culture at the time of his cataract procedure which was negative. His last examination 1 month following surgery showed vision of 2/200 in the right eye which improves with pinhole to 20/160 and intraocular pressure (IOP) 12 mmHg controlled on a single antiglaucoma medication (Xolamol drops). The slit lamp examination showed corneal + 2 edema and haze, total peripheral anterior synechia with shallow AC, stable IOL, and hazy fundus view [Figure 2d].

DISCUSSION

Listeria monocytogenes is an aerobic, ubiquitous, motile, non-spore forming gram positive bacillus recognized as an intracellular pathogen in human. It produces beta hemolysis on blood agar and is occasionally mistaken for diphtheroids. The name Listeria monocytogenes is acquired because of its ability to elicit a monocytic blood reaction in animal hosts. The organism have been recognized as an animal pathogen.6 Although most infections are sporadic, outbreaks have been also described.5,6 Eliott et al., proposed that iris necrosis with pigment dispersion is perhaps a feature unique to Listeria monocytogenes; however, he added that the precise factor(s) responsible for this remains undetermined.6

Food-borne transmission has been identified in epidemic and sporadic human listeriosis. Variety of food have been associated with listeriosis such as soft cheeses, raw vegetable, milk, fish, and meat.5,6 Infection most frequently affect neonates, elderly patients, pregnant women, and immunocompromised individuals.5 However, it can also occur in healthy persons such as in our case who was young and otherwise immunocompetent. In pregnant women, the organism causes perinatal listeric septicemia. The most common infection associated with Listeria monocytogenes is meningitis.6

In the ophthalmic practice, ocular listeriosis is rare, most frequently in the form of conjunctivitis. It has been also shown that listeriosis can rarely cause endopthalmitis.5,6 Listeria monocytogenes as a rare cause of endophthalmitis was first reported by Goodner and Okumoto in 1967.7 Since then several other cases have been reported. That particular case however did not present with dark hypopyon. Eliott and his coauthors in 1992 reviewed all previously 14 reported cases, identified the cases presenting with a pigmented hypopyon and added their own experience with an additional case.6 In their report they highlighted that all cases reviewed were presumed to be endogenous. There was no sex predilection. The mean age was 62 years (with a range of 47-76 years) and only five patients were immunocompromised. The main presenting symptoms were markedly reduced visual acuity ranging from 20/80 to light perception, high intraocular pressure with a mean of 45 mmHg, and fibrinous AC reaction. In all cases the diagnosis was established by culture.

Our patient is much younger in age, he presented with similar symptoms and he was believed to be immunocompetent. The diagnosis in our case was a dilemma because of his unclear refractive surgery history, young age, normal immune status, the absence of localized corneal stromal infiltrate, and dark hypopyon. Therefore, the diagnosis in his case was delayed until the positive culture result with the identification of the organism came back. In view of the facts that Listeria has the ability to penetrate the corneal epithelium, and that this patient had a laser refractive procedure 6 months prior to his presentation, we believe that his ocular infection is surgically related rather than being endogenous. In addition, it seems that the ring-like deep stromal haze observed on admission represents the edge of a LASIK flap and he was on prolonged topical steroids which can be considered a risk factor for infection. On the other hand, the AC was extensively involved compared to the vitreous which did not show initially any findings to support the diagnosis of endogenous endophthalmitis.

In regard to the pigmented hypopyon, the dark color is attributed to iris necrosis and pigment dispersion which are unique to Listeria monocytogenes. The precise factors for this are still unclear.6,8 In the previous review by Eliott et al., five cases had dark hypopyon (including their case) which was similar to ours. Listeria monocytogenes can multiply within macrophages, and successful therapy should employ antibiotics that penetrate cells and have the ability to kill the organism.6

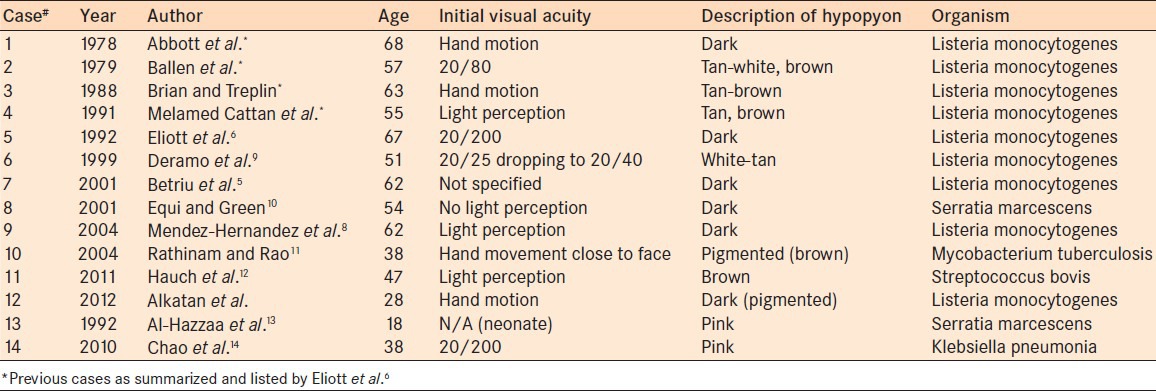

We have carefully reviewed the published cases of endophthalmitis with colored hypopyon. These are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Infectious agents reported to result in intraocular infection with a colored hypopyon

The pigmented hypopyon (ranging from tan to brown-dark) is mostly caused by Listeria monocytogenes; however, other infectious agents have been described namingly Serratia marcescens,10 Streptococcus bovis,12 and Mycobacterium tuberculosis.11 Some of these cases also have shown pigment dispersion. Noninfectious etiologies for a dark pigmented hypopyon include melanoma where the hypopyon is composed of pigment-laden macrophages and neoplastic melanoma cells15 and juvenile xanthogranuloma.16 On the other hand, pink hypopyon has been described in association with two causative organisms. The first is Serratia marcescens, also known as Bacterium prodigiosum because it produces a red pigment which has been a useful marker in bacteremia after dental extractions as well as bacteriuria after urinary tract procedures.13 The second is Klebsiella pneumonia where the authors speculated that the pink hypopyon was caused by severe necrosis similar to the characteristic brick-red or “currant jelly” sputum seen in Klebsiella pneumomia.14

The diagnosis is often delayed which can adversely affect the prognosis specially that intraocular malignancy is usually suspected in these cases. In such conditions ultrasound biomicroscopy might be helpful8 using PCR for identification of such a pathogen (Listeria) in intraocular infections has been recommended.17 This might ensure prompt appropriate antimicrobial therapy specially in patients with comorbidities.9,18

CONCLUSION

We believe that the Listeria infection in our case was exogenous and was related to his previous refractive laser procedure. Ophthalmologists should be aware of the potential for this serious type of infection after LASIK especially with prolonged steroid therapy. They also should be aware of the differential diagnosis in cases of colored hypopyon and elevated intraocular pressure since early diagnosis is essential for a better outcome.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Holbach LM, Bialasiewicz AA, Boltze HJ. Necrotizing ring ulcer of the cornea caused by exogenous Listeria monocytogenes serotype IV b infection. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;106:105–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76404-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eiferman RA, Flaherty KT, Rivard AK. Persistent corneal defect caused by listeria monocytogenes. Am J Ophthalmol. 1990;109:97–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)75592-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaidman GW, Coudron P, Piros J. Listeria monocytogenes keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1990;109:334–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)74561-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holland S, Alfonso E, Gelender H, Heidmann D, Mendelsohn A, Ullman S, Miller D. Corneal ulcer due to listeria monocytogenes. Cornea. 1987;6:144–6. doi: 10.1097/00003226-198706020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Betriu C, Fuentemilla S, Mendez R, Picazo JJ, Gracia-Sanchez J. Endophthalmitis caused by Listeria monocytogenes. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:2742–4. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.7.2742-2744.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eliott D, O’Brien TP, Green WR, Jampel HD, Goldberg MF. Elevated intraocular pressure, pigment dispersion and dark hypopyon in endophthalmitis from Listeria monocytogenes. Surv Ophthalmol. 1992;37:117–24. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(92)90074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodner EK, Okumoto M. Intraocular listeriosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1967;64:682–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(67)92848-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendez-Hernandez C, Gracia-Feijoo J, Garcia-Sanchez J. Listeria monocytogenes-induced endogenous endophthalmitis: Bio-ultrasonic findings. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:579–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deramo VA, Shah GK, Garden M, Maguire JI. Good visual outcome after Listeria monocytogenes endogenous endophthalmitis. Retina. 1999;19:566–8. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199919060-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Equi RA, Green WR. Endogenous Serratia marcescens endophthalmitis with dark hypopyon: Case report and review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2001;46:259–68. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(01)00263-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rathinam SR, Rao NA. Tuberculous intraocular infection presenting with pigmented hypopyon: A clinicopathologic case report. Br J Opthalmol. 2004;88:721–2. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2003.029124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hauch A, Eliott D, Rao NA, Vasconcelos-Santos DV, O’Hearn T, Fawzi AA. Dark hypopyon in Streptococcus bovis endogenous endophthalmitis: Clinicopathologic correlations. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2010;1:39–41. doi: 10.1007/s12348-010-0008-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.al Hazzaa SA, Tabbara KF, Gammon JA. Pink hypopyon: A sign of Serratia marcescens endophthal mitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76:764–5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.76.12.764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chao AN, Chao A, Wang NC, Kuo YH, Chen TL. Pink hypopyon caused by Klebsiella pneumonia. Eye (Lond) 2010;24:929–31. doi: 10.1038/eye.2009.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albert DM, Lahav M, Troczynski E, Bahr R. Black hypopyon: Report of two cases. Albrecht Von Graefes Arch Klin Exp Ophthalmol. 1975;193:81–94. doi: 10.1007/BF00410528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fontanilla FA, Edward DP, Wong M, Tessler HH, Eagle RC, Goldstein DA. Juvenile Xanthogranuloma masquerading as melanoma. J AAPOS. 2009;13:515–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lohmann CP, Gabel VP, Heep M, Linde HJ, Reischl U. Listeria monocytogenes-induced endogenous endophthalmitis in an otherwise healthy individual: Rapid PCR-diagnosis as the basis for effective treatment. Eur J Ophthalmol. 1999;9:53–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hueber A, Welsandt G, Grajewski RS, Roters S. Fulminant endogenous anterior uveitis due to listeria monocytogenes. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2010;1:63–5. doi: 10.1159/000321127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]