Abstract

Gastric varices (GVs) are notorious to bleed massively and often difficult to manage with conventional techniques. This mini-review addresses endoscopic management principles for gastric variceal bleeding, including limitations of ligation and sclerotherapy and merits of endoscopic variceal obliteration. The article also discusses how emerging use of endoscopic ultrasound provides optimism of better diagnosis, improved classification, innovative management strategies and confirmatory tool for eradication of GVs.

Keywords: Gastric, Varices, Endoscopy, Ligation, Sclerotherapy, Management, Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt, Endoscopic ultrasound, Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration, Endoscopic variceal obliteration

Core tip: This mini-review addresses endoscopic management principles for gastric variceal bleeding. Endoscopic variceal obliteration (EVO) with tissue adhesives is the currently accepted strategy for controlling bleeding and eradicating gastric varices (GVs). EVO is deemed better than both variceal ligation and sclerotherapy in randomized controlled trials. One unsettled issue with EVO is if routine reinjection is better than reinjection in case of rebleeding. The experience with combination treatments is still premature. For secondary prophylaxis, EVO, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt or beta-blocker use is recommended. Emerging use of EUS provides optimism of better diagnosis, improved classification, innovative management strategies and confirmatory tool for eradication of GVs.

INTRODUCTION

The natural history of gastric varices (GVs) is less understood than that of esophageal varices (EVs). GVs may be seen in 18%-70% of the patients with portal hypertension (PHT) and are probable source of bleeding in 10%-36% of patients with acute variceal bleeding (AVB)[1-3]. Isolated GVs (IGVs), without EVs, are seen in 5%-12% of patients with PHT[1-3]. They are also commonly seen in patients with non-cirrhotic portal hypertension (NCPHT), especially with splenic vein thrombosis (SVT). They are more commonly associated with shunts than EVs, most commonly spleno-renal shunt, and their management is quite different from that of EVs.

CLASSIFICATIONS

GVs are commonly classified according to Sarin’s classification[4,5] based on location and direction of blood flow: GOV1 (Gastro-Oesophageal Varices) are the most common (74% of all GV) and consist of the esophageal varices extending along the lesser curvature of stomach; GOV2 are the extension of the esophageal varices along the greater curvature near the fundus; IGV1 are isolated gastric varices localized to fundus, without any associated esophageal varices. These arise from spleno-renal or gastro-renal shunts where the feeding vessel arises from the splenic hilum and drains in to left renal vein through gastric cardia/fundus veins. GOV2 and IGV1 are sometimes together called “fundic varices”. IGV2 are the isolated gastric varices present elsewhere other than the fundus, which drain in a similar fashion into left renal vein but with multiple tributaries. It is reported that fundal varices (GOV2 and IGV1), though less common than GOV1 varices, are noted to account for 80% of patients with bleeding GV.

Hashizume et al[6] proposed an alternate classification of GVs based on endoscopic findings, taking into account their shape (tortuous = F1, nodular = F2, and tumorous = F3), location (anterior = La, posterior = Lp, lesser curvature = Ll, greater curvature = Lg of the cardia, and fundic area = Lf) and color (white = Cw or red = Cr) and further emphasized on presence of glossy, thin-walled focal redness on the varix called as red color spot (RC spot) as a marker of impending bleeding risk[6].

BLEEDING RISK OF GVS

Although GVs are known to bleed less frequently than the EVs, however when they do, they bleed massively and are difficult to achieve primary hemostasis, with a mortality rate of 10%-30%[4,5]. Their chance of re-bleeding is high (35% to 90%) after spontaneous remission and 22%-37% with the glue technique[4,5]. The chance of variceal bleeding is driven by the pressure changes rather than hemostatic forces. The pressures in the GVs are lower than the in the EVs because of their larger size and more frequent presence of the shunts like spleno-renal[7,8]. Despite this, their rupture is more devastating because of the fact that the wall stress increases dramatically even with small rise in the portal pressures due to their larger radius. When there is increase in transmural pressure, the variceal size increases and wall thickness decreases, which leads to rupture[7,8]. The factors which predict hemorrhage in EVs also govern GVs: most importantly the size of the varices (15% in patients with large varices, which are defined as > 10 mm), decompensated cirrhosis and endoscopic presence of the red wale sign. Another factor implicated in increase in incidence and/or size of fundic varices and possible bleeding is the treatment of EVs by either endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) or endoscopic sclerotherapy (EST)[9]. The plausible explanation is that after treatment the existing collaterals are not sufficient enough to decompress the portal pressure causing an increased incidence of fundic varices.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT OF BLEEDING GVS

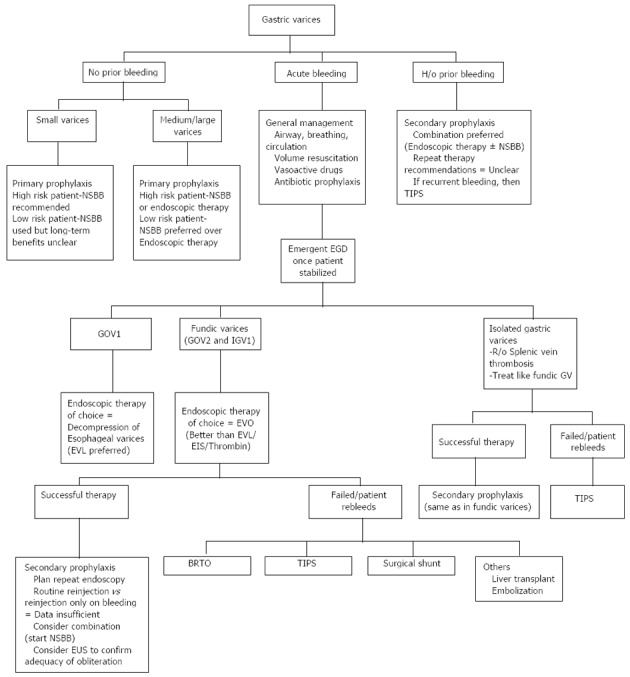

The preliminary management of bleeding GVs is the same as any other variceal bleeding[1-3]. Fluid resuscitation, airway protection, antibiotic administration for the bacterial peritonitis prophylaxis and use of vasoactive agents like octreotide and acid suppressant agents like proton pump inhibitors form cornerstone of initial management. Cautious administration of the blood products (to achieve a target of hemoglobin level between 7-8 g/dL) is advocated as there is potential risk of increased rebleeding if the portal pressures increase due to repeated transfusions. A schematic of management algorithm of GVs is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Proposed management algorithm for gastric varices. High risk patient: Child Pugh class B or C or endoscopic presence of red wale sign; Low Risk Patient: Child Pugh class A and no endoscopic high-risk features. GV: Gastric varices; EVO: Endoscopic variceal obliteration; EVL: Endoscopic variceal ligation; EIS: Endoscopic injection sclerotherapy; NSBB: Non specific beta blocker; BRTO: Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration; TIPS: Trans-jugular intra-hepatic porto-systemic shunt; GOV: Gastro-oesophageal varices; IGV: Isolated gastric varices.

Treatment options for acute GV bleeding are varied and include medical, surgical, endoscopic, and endovascular approaches[1-3]. Two general methods exist to deal with bleeding GVs: directly exclude the varices from the porto-systemic system or indirectly decrease the pressure in the varices by decompressing the portal system.

Direct approach

Variceal management by direct endoscopy or endoscopic ultrasound.

Role of endoscopy: Once the patient is deemed stable from airway and circulation standpoint, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) should be performed, which might show active bleeding or reveal stigmata of recent bleeding, in addition to qualify type of GVs and concomitant presence of EVs or PHG[1-3].

Several endoscopic techniques have been tested to control acute gastric variceal bleeding with varying successes. However, the universal phenomena is that majority of the methods used in controlling the bleeding EVs are difficult to practice in GVs and are inconsistently successful. These include endoscopic injection sclerotherapy (EIS) and esophageal variceal ligation (EVL). The varying success of these methods may be owing to different physiology and size of GVs which pose technical problems.

GV ligation: The main indications for ligation in management of acute GV bleeding is banding of GOV1 varices, which are extensions of EVs into the stomach along the lesser curvature or as salvage strategy if other modalities are not available[10]. Studies suggest good hemostasis efficacy and comparable re-bleeding rates of GOV1 ligation to EVL of EVs. There is limited role for ligation in management of bleeding fundic varices[1-3]. In head-to-head studies, EVL was less effective than endoscopic obturation by injection of cyanoacrylate for hemostasis of large GVs[11], and had higher re-bleeding rates too[12]. Smaller studies have attempted improvisation of ligation methods to increase its success in GV, like using detachable snares and elastic bands or in combination with sclerotherapy, however these experimental techniques are yet to be implemented universally[13,14].

Endoscopic injection sclerotherapy: Fundic varices (IGV1 and IGV2) are wider and have larger volume, needing large quantity of sclerosant which is susceptible to being washed away, potentially leading to systemic (esp. pulmonary) embolization, and may also lead to increased chances of ulceration at injection site. Before the advent of newer techniques, sclerotherapy of GVs using alcohol or tetradecyl sulfate was common and was associated with decent initial hemostasis rates (up to 67%-100%), however the higher frequency of re-bleeding mainly due to post-procedure ulceration severely limited its long-term success[10]. Furthermore, the risk of complications including fever, retrosternal chest pain, temporary dysphagia and pleural effusions was unacceptably higher with EIS[15]. Overall, the success of EIS is questionable in management of acute GV bleeding[16] and hence is not the preferred method in any of the guidelines.

Endoscopic variceal obturation: Endoscopic variceal obturation (EVO) using tissue adhesives like glue, cyanoacrylate or histoacryl has provided a positive direction to management of fundic varices, which was always a challenge. Cyanoacrylate is a polymer which upon coming in contact with blood polymerises instantly leading to obliteration of varices. It is called “obliteration” and not “eradication” since the varices may be still visible post-treatment.

EVO with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate has been the advocated first-line method in managing the gastric varices especially fundic varices[1-3]. Kang et al[17] performed EVO with cyanoacrylate in 127 patients with GVs (100 active bleeding and 27 prophylactically) and reported a primary hemostasis rate of 98.4% (1 session-98 patients, 2 sessions-25 patients, ≥ 3 sessions-4 patients), with a recurrent bleeding rate of 18.1 % at 1 year[17]. Several studies have compared EVO head-to-head with EIS or EVL to conclude the favorable outcomes of EVO in terms of initial hemostasis, and lesser re-bleeding and complications[11,12,18-20]. Furthermore, re-bleeding rates after EVO were found to be comparable to transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt (TIPS) in patients with acute GV bleeding, suggesting this technique may be equally efficacious in secondary prevention and creating opportunity of therapy in patients in who TIPS is contraindicated for encephalopathy reasons[21]. Few studies have advocated using dynamic CT scan prior to EVO to increase the detection of feeding vessels, assessment of direction of blood flow, presence of shunts, in an attempt to increase efficacy and minimize complications of EVO technique[22], although this is not universally practiced.

Although EVO is clearly a superior technique than EIS or EVL for bleeding GVs, it is not free of technical difficulties (para-variceal injection, needle sticking in the varix, intra-peritoneal injection leading to peritonitis and adherence of the glue to the endoscope) or complications (fever, para-variceal injection with mucosal necrosis and bleeding, embolization into the renal vein, IVC, pulmonary or systemic vessels and retro-gastric abscesses)[12,18-20]. However, emerging literature supports preference of distilled water over saline to dilute cyanoacrylate to decrease coagulation and use of standardized techniques of tissue adhesive preparation and delivery to decrease rates of these complications[23]. In case of large gastric varix, it is advised to begin tissue adhesive injection from bottom to dome to minimize risk of bleeding if injected directly at high pressure-high flow dome area. Liu et al[24] reported an interesting scenario which developed when EVO of GVs led to hemorrhage from EVs due to embolism of the glue into the EV thus increasing the pressure. This was not amenable to EV ligation due to presence of foreign body (glue) and was managed with cyanoacrylate injection into EVs to achieve hemostasis and authors rightly cautioned endoscopists to treat EVs in the same setting as EVO of GVs to prevent such a complication[24].

Another major difference between EVO and other endoscopic techniques is that variceal obliteration of the GVs is not quite obvious after cyanoacrylate injection, and hence adequacy of EVO is controversial. Most often GVs are probed with an endoscope and the induration is accepted as a sign of inadequate obliteration with the need to inject more tissue adhesive till it is “hard” to palpate. Improved radiology (use of CT portography)[22] and newer endoscopic techniques have made this EVO adequacy assessment easier, as discussed later in this article. Notably, EVO has recently been shown to be superior to beta blocker therapy for primary prophylaxis of GVs and hence is being advocated[25]. Evidence regarding efficacy of the glue in pregnant females and in children is still emerging and premature, and so is data on newer combination EVO-sclerotherapy modalities[26].

Novel EVO materials: Endoscopists are trying several materials to achieve hemostasis in technically challenging situations, like successful use of hemostatic powder in situation with failed EVO with cyanoacrylate glue and contraindication to TIPS due to dilated cardiomyopathy[27]. Thrombin was used by Yang et al[28] and Ramesh et al[29] in separate studies to successfully achieve initial hemostasis 100% and 92% patients, with re-bleeding rates of 27% and 0% respectively. Thrombin helps in clotting by converting fibrinogen to fibrin and promotes platelet aggregation as well. Although these studies were limited by their patient size (12 and 13 patients respectively)[28,29], and did not report any untoward thrombo-embolic events, the concern for thrombin leakage into systemic circulation and potentially causing disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) or systemic embolization still remains. It is currently not being advocated due to lack of adequate data.

Role of endoscopic ultrasound: It is common knowledge that endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) enables the visualization of esophago-gastric varices and other venous collaterals viz. peri- and para-esophageal collateral veins and perforating veins, in patients with PHT, and can be useful to assess the patency of the portal venous system[30]. There has been an attempt in 1993 to classify gastric varices endosonographically by Boustière et al[31], which considered size of GVs and gastric wall abnormalities (Table 1), and inferred that while endoscopy graded EVs better, EUS was a better tool to classify GVs and early signs of portal gastropathy. The other EUS features of portal hypertension, in addition to EVs and GVs, may include dilatation of the azygos vein, splenic vein and portal vein, increased diameter of the thoracic duct, thickening of gastric mucosa and submucosa, presence of portal hypertensive gastropathy, and the presence of rectal varices[30,32]. In addition, EUS combined with color Doppler imaging enabled visualization of shunts viz. gastro-renal shunt in one report[33]. Furthermore, EUS doppler helps characterize gastric submucosal lesions better than EGDs before proceeding to the biopsy of potential GV.

Table 1.

Endoscopic ultrasound classification of gastric varices: Proposed by Boustiere et al in 1993

| Endoscopic ultrasound classification of gastric varices | |

| 1: Size of gastric varices | Grade 0 (none) |

| Grade 1 (small or non-confluent varies < 5 mm) | |

| Grade 2 (large or confluent varices ≥ 5 mm) | |

| 2: Abnormalities of gastric wall | Grade 0 (none) |

| Grade 1 (thickening and brilliance of the third | |

| hyperechogenic layer with or without fine | |

| internal anechogenic structures) | |

| Grade 2 (visible vessels in the third layer which deform the entire wall, with penetrating varices) | |

Role of EUS in risk estimation for GV bleeding is a field of growing interest. EUS probes can be used to measure size of varices (diameter), and furthermore to estimate variceal wall thickness which is deemed as a better predictor of bleeding than varices diameter alone[34]. Intra-variceal pressure measurement may be a better surrogate for risk of bleeding, which can be accomplished by direct variceal puncture which is not practiced because of invasiveness. Although data is slim, there has been an attempt looking at EUS guided EV pressure recording, to better predict risk of bleeding, and it has been shown to have reasonable correlation with hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG)[35]. Finally, high risk stigmata like red hematocytic spot can be visualized with EUS[36].

EUS-assisted injection sclerotherapy for both gastric[37] and esophageal varices[38] is effective, achieving high eradication and low recurrence rates in long-term follow-up. In fact the risk of re-bleeding after EUS directed sclerotherapy is reportedly lower than endoscopic technique. Recently additional attention has been diverted towards EUS delivered therapies to control bleeding in acute variceal bleeding patients, using unique agents like adhesive tissue (histoacryl)[39], thrombin[40] and EUS-guided coil injection for gastric[41] and ectopic duodenal varices[42]. Last but not the least, EUS finds its utility in confirmation of adequacy of EVO of gastric varices, eliminating the need for inept endoscope probing assessment and thus increasing overall efficacy of EVO technique[43]. A recent study from Taiwan used miniature ultrasound probe (MUP) sonography in 34 patients who underwent cyanoacrylate EVO therapy for acute GV bleeding, during follow-up endoscopy session to assess adequacy of obturation and reinjection if necessary. The authors demonstrated a significantly greater free-of-rebleeding rate and trend towards better survival for patients in MUP group compared with conventional endoscopy group[43]. Although these advances bring a sound of promise, EUS probe which has a larger diameter compared to conventional scope, in addition to GV intervention is certainly a high-risk procedure. Using a mini-probe may counter some of this added disadvantage but non-availability of pediatric sizes is still a limitation. Furthermore, future studies need to compare radial and linear EUS scopes in diagnosis and management of varices.

Indirect approach

Decreasing portal pressure - either surgically or percutaneously by establishing a TIPS.

Role of TIPS: Porto-systemic shunts such as TIPS are typically advocated as second-line acute therapy (after endoscopic management) to prevent re-bleeding of varices[1-3]. Although decreasing portal pressure is considered effective in reducing the bleeding rate of EVs, it is inconsistently effective for GVs, which tend to occur and bleed at lower portal pressures[21,44]. Also there is discordance between decreased hepato-portal gradient with TIPS and actual decrease in GV re-bleeding. In addition, TIPS has its own limitations including worsening of encephalopathy or shunt occlusion, which can lead to recurrence of hemorrhage, and surveillance for patency.

Role of advanced radiological procedures: If all endoscopic techniques and TIPS fail or if TIPS is contraindicated, then the next step would be balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO)[1-3], which is a popular technique in Japan, and allowing modulation of flow within the varices. BRTO was popularized and named by Kanagawa et al[45] in 1996, this technique optimize the action of the sclerosing agent by inducing stagnation in the gastric varices, thereby allowing maximal sclerosant dwell time to cause endothelial sclerosis and vascular thrombosis. The discussion of technique, advantages and complications of BRTO is beyond the scope of current mini-review, but one of the emerging fronts in management of acute GV bleeding.

CONCLUSION

GVs are notorious to bleed massively and often difficult to manage with conventional techniques. EVO with cyanoacrylate glue injection is currently the most favored for being superior to variceal ligation or sclerotherapy in achieving hemostasis in acute gastric variceal bleeding. Endoscopists must remain cognizant about the possible complications of tissue adhesive injections and strive for standardization of EVO techniques to minimize them. Novel techniques like use of thrombin, coil embolization are under investigation as alternatives to cyanoacrylate aiming for improved outcomes. TIPS and BRTO are advanced radiological procedures available as salvage techniques in uncontrollable bleeding situations or when patients are not candidates or have failed endoscopic management. The role of EUS in the therapeutic algorithm for GVs is still evolving. EUS is being used to confirm presence, size and location of GVs, to stratify the risk of re-bleeding, as a therapeutic tool to perform sclerotherapy or EVO, and to confirm eradication of GVs after EVO. Emerging use of EUS provides optimism of better diagnosis, improved classification, innovative management strategies and confirmatory tool for eradication of GVs.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers: Bayraktar Y, Harmanci O, Mesquita RA, Picchio M, Stephenne X S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A

E- Editor: Zhang DN

References

- 1.Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46:922–938. doi: 10.1002/hep.21907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qureshi W, Adler DG, Davila R, Egan J, Hirota W, Leighton J, Rajan E, Zuckerman MJ, Fanelli R, Wheeler-Harbaugh J, et al. ASGE Guideline: the role of endoscopy in the management of variceal hemorrhage, updated July 2005. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:651–655. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Franchis R. Revising consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno V consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2010;53:762–768. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarin SK, Kumar A. Gastric varices: profile, classification, and management. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:1244–1249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarin SK, Lahoti D, Saxena SP, Murthy NS, Makwana UK. Prevalence, classification and natural history of gastric varices: a long-term follow-up study in 568 portal hypertension patients. Hepatology. 1992;16:1343–1349. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840160607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hashizume M, Kitano S, Yamaga H, Koyanagi N, Sugimachi K. Endoscopic classification of gastric varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:276–280. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(90)71023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polio J, Groszmann RJ. Hemodynamic factors involved in the development and rupture of esophageal varices: a pathophysiologic approach to treatment. Semin Liver Dis. 1986;6:318–331. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1040614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watanabe K, Kimura K, Matsutani S, Ohto M, Okuda K. Portal hemodynamics in patients with gastric varices. A study in 230 patients with esophageal and/or gastric varices using portal vein catheterization. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:434–440. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(88)90501-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yüksel O, Köklü S, Arhan M, Yolcu OF, Ertuğrul I, Odemiş B, Altiparmak E, Sahin B. Effects of esophageal varice eradication on portal hypertensive gastropathy and fundal varices: a retrospective and comparative study. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:27–30. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-3078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryan BM, Stockbrugger RW, Ryan JM. A pathophysiologic, gastroenterologic, and radiologic approach to the management of gastric varices. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1175–1189. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lo GH, Lai KH, Cheng JS, Chen MH, Chiang HT. A prospective, randomized trial of butyl cyanoacrylate injection versus band ligation in the management of bleeding gastric varices. Hepatology. 2001;33:1060–1064. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.24116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan PC, Hou MC, Lin HC, Liu TT, Lee FY, Chang FY, Lee SD. A randomized trial of endoscopic treatment of acute gastric variceal hemorrhage: N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate injection versus band ligation. Hepatology. 2006;43:690–697. doi: 10.1002/hep.21145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee MS, Cho JY, Cheon YK, Ryu CB, Moon JH, Cho YD, Kim JO, Kim YS, Lee JS, Shim CS. Use of detachable snares and elastic bands for endoscopic control of bleeding from large gastric varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:83–88. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.125104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshida T, Harada T, Shigemitsu T, Takeo Y, Miyazaki S, Okita K. Endoscopic management of gastric varices using a detachable snare and simultaneous endoscopic sclerotherapy and O-ring ligation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;14:730–735. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.1999.01941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schuman BM, Beckman JW, Tedesco FJ, Griffin JW, Assad RT. Complications of endoscopic injection sclerotherapy: a review. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:823–830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trudeau W, Prindiville T. Endoscopic injection sclerosis in bleeding gastric varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 1986;32:264–268. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(86)71843-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang EJ, Jeong SW, Jang JY, Cho JY, Lee SH, Kim HG, Kim SG, Kim YS, Cheon YK, Cho YD, et al. Long-term result of endoscopic Histoacryl (N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate) injection for treatment of gastric varices. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1494–1500. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i11.1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarin SK, Jain AK, Jain M, Gupta R. A randomized controlled trial of cyanoacrylate versus alcohol injection in patients with isolated fundic varices. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1010–1015. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mishra SR, Chander Sharma B, Kumar A, Sarin SK. Endoscopic cyanoacrylate injection versus beta-blocker for secondary prophylaxis of gastric variceal bleed: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2010;59:729–735. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.192039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belletrutti PJ, Romagnuolo J, Hilsden RJ, Chen F, Kaplan B, Love J, Beck PL. Endoscopic management of gastric varices: efficacy and outcomes of gluing with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate in a North American patient population. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22:931–936. doi: 10.1155/2008/389517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lo GH, Liang HL, Chen WC, Chen MH, Lai KH, Hsu PI, Lin CK, Chan HH, Pan HB. A prospective, randomized controlled trial of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt versus cyanoacrylate injection in the prevention of gastric variceal rebleeding. Endoscopy. 2007;39:679–685. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rice JP, Lubner M, Taylor A, Spier BJ, Said A, Lucey MR, Musat A, Reichelderfer M, Pfau PR, Gopal DV. CT portography with gastric variceal volume measurements in the evaluation of endoscopic therapeutic efficacy of tissue adhesive injection into gastric varices: a pilot study. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:2466–2472. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1616-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seewald S, Ang TL, Imazu H, Naga M, Omar S, Groth S, Seitz U, Zhong Y, Thonke F, Soehendra N. A standardized injection technique and regimen ensures success and safety of N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate injection for the treatment of gastric fundal varices (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:447–454. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu TT, Hou MC, Lin HC, Chang FY, Lee SD. Esophageal impaction: a rare complication of tissue glue injection for gastric variceal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2001;33:905. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-17334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mishra SR, Sharma BC, Kumar A, Sarin SK. Primary prophylaxis of gastric variceal bleeding comparing cyanoacrylate injection and beta-blockers: a randomized controlled trial. J Hepatol. 2011;54:1161–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi B, Wu W, Zhu H, Wu YL. Successful endoscopic sclerotherapy for bleeding gastric varices with combined cyanoacrylate and aethoxysklerol. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3598–3601. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holster IL, Poley JW, Kuipers EJ, Tjwa ET. Controlling gastric variceal bleeding with endoscopically applied hemostatic powder (Hemospray™) J Hepatol. 2012;57:1397–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang WL, Tripathi D, Therapondos G, Todd A, Hayes PC. Endoscopic use of human thrombin in bleeding gastric varices. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1381–1385. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramesh J, Limdi JK, Sharma V, Makin AJ. The use of thrombin injections in the management of bleeding gastric varices: a single-center experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:877–882. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.02.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caletti G, Brocchi E, Baraldini M, Ferrari A, Gibilaro M, Barbara L. Assessment of portal hypertension by endoscopic ultrasonography. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:S21–S27. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(90)71011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boustière C, Dumas O, Jouffre C, Letard JC, Patouillard B, Etaix JP, Barthélémy C, Audigier JC. Endoscopic ultrasonography classification of gastric varices in patients with cirrhosis. Comparison with endoscopic findings. J Hepatol. 1993;19:268–272. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(05)80581-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faigel DO, Rosen HR, Sasaki A, Flora K, Benner K. EUS in cirrhotic patients with and without prior variceal hemorrhage in comparison with noncirrhotic control subjects. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:455–462. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.107297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kakutani H, Hino S, Ikeda K, Mashiko T, Sumiyama K, Uchiyama Y, Kuramochi A, Kitamura Y, Matsuda K, Kawamura M, et al. Use of the curved linear-array echo endoscope to identify gastrorenal shunts in patients with gastric fundal varices. Endoscopy. 2004;36:710–714. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-825658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jackson FW, Adrain AL, Black M, Miller LS. Calculation of esophageal variceal wall tension by direct sonographic and manometric measurements. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:247–251. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70233-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pontes JM, Leitão MC, Portela F, Nunes A, Freitas D. Endosonographic Doppler-guided manometry of esophageal varices: experimental validation and clinical feasibility. Endoscopy. 2002;34:966–972. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-35840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schiano TD, Adrain AL, Vega KJ, Liu JB, Black M, Miller LS. High-resolution endoluminal sonography assessment of the hematocystic spots of esophageal varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:424–427. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee YT, Chan FK, Ng EK, Leung VK, Law KB, Yung MY, Chung SC, Sung JJ. EUS-guided injection of cyanoacrylate for bleeding gastric varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:168–174. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.107911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Paulo GA, Ardengh JC, Nakao FS, Ferrari AP. Treatment of esophageal varices: a randomized controlled trial comparing endoscopic sclerotherapy and EUS-guided sclerotherapy of esophageal collateral veins. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:396–402; quiz 463. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Romero-Castro R, Pellicer-Bautista FJ, Jimenez-Saenz M, Marcos-Sanchez F, Caunedo-Alvarez A, Ortiz-Moyano C, Gomez-Parra M, Herrerias-Gutierrez JM. EUS-guided injection of cyanoacrylate in perforating feeding veins in gastric varices: results in 5 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:402–407. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krystallis C, McAvoy NC, Wilson J, Hayes PC, Plevris JN. EUS-assisted thrombin injection for ectopic bleeding varices--a case report and review of the literature. QJM. 2012;105:355–358. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcr030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Binmoeller KF, Weilert F, Shah JN, Kim J. EUS-guided transesophageal treatment of gastric fundal varices with combined coiling and cyanoacrylate glue injection (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1019–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levy MJ, Wong Kee Song LM, Kendrick ML, Misra S, Gostout CJ. EUS-guided coil embolization for refractory ectopic variceal bleeding (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:572–574. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liao SC, Yang SS, Ko CW, Lien HC, Tung CF, Peng YC, Yeh HZ, Chang CS. A miniature ultrasound probe is useful in reducing rebleeding after endoscopic cyanoacrylate injection for hemorrhagic gastric varices. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:1347–1353. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2013.838995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tripathi D, Therapondos G, Jackson E, Redhead DN, Hayes PC. The role of the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunt (TIPSS) in the management of bleeding gastric varices: clinical and haemodynamic correlations. Gut. 2002;51:270–274. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.2.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kanagawa H, Mima S, Kouyama H, Gotoh K, Uchida T, Okuda K. Treatment of gastric fundal varices by balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;11:51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1996.tb00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]