Abstract

Introduction

Angiogenesis is essential to human biology and of great clinical significance. Excessive or reduced angiogenesis can result in, or exacerbate, several disease states, including tumor formation, exudative age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and ischemia. Innovative drug delivery systems can increase the effectiveness of therapies used to treat angiogenesis-related diseases.

Areas covered

This paper reviews the basic biology of angiogenesis, including current knowledge about its disruption in diseases, with the focus on cancer and AMD. Anti- and proangiogenic drugs available for clinical use or in development are also discussed, as well as experimental drug delivery systems that can potentially improve these therapies to enhance or reduce angiogenesis in a more controlled manner.

Expert opinion

Laboratory and clinical results have shown pro- or antiangiogenic drug delivery strategies to be effective in drastically slowing disease progression. Further research in this area will increase the efficacy, specificity and duration of these therapies. Future directions with composite drug delivery systems may make possible targeting of multiple factors for synergistic effects.

Keywords: age-related macular degeneration, angiogenesis, antiangiogenesis, biomaterials, cancer, drug delivery, ischemia, nanoparticle

1. Introduction

Vascular perfusion is essential for adequate nutrient, waste and gas exchange for all tissues in the human body. Many diseases stem from insufficient blood perfusion, resulting in a shortage of oxygen, termed hypoxia. Angiogenesis is an important mechanism of physiological vascularization in adults, whereby new blood vessels sprout from existing ones by a coordinated interaction of endothelial cells with angiogenesis-inducing signals, such as growth factors (GFs), hypoxic conditions and extracellular matrix (ECM) components, specifically adhesion molecules [1]. Vasculogenesis is a neovascularization process that involves recruitment of circulating vascular progenitor cells, originating from the multipotent hemangioblast precursor cells residing in bone marrow or peripheral blood, instead of local endothelial cells as in the case of angiogenesis [2]. Traditionally, vasculogenesis was considered to occur only during embryonic development of the circulatory system [3], and neovascularization in adults was believed to occur by means of angiogenesis or arteriogenesis, a process of flow-induced remodeling of pre-existing blood vessels. However, recent studies have suggested that circulating endothelial progenitor cells can be recruited by cytokines to induce limited vasculogenesis in ischemic areas in adults [4].

Angiogenesis is also critical in pathologic states such as psoriasis [5], atherosclerosis [6,7], rheumatoid arthritis [8,9], diabetes [10], cancer [11] and ocular neovascularization [12] in age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and diabetic retinopathy. Normal angiogenesis is usually focal and self-limited, whereas in pathologic processes, aberrant angiogenesis is often persistent and widespread [13].

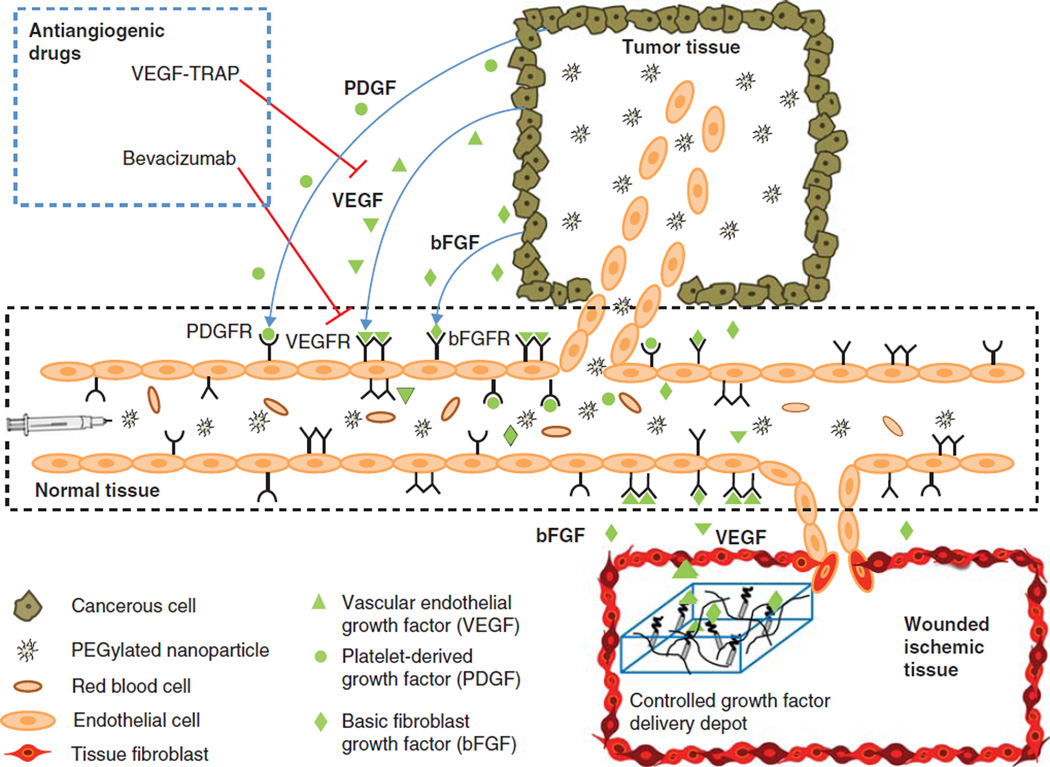

A wide range of pro- and antiangiogenic processes act in concert to orchestrate angiogenesis (Figure 1). Among the many GFs implicated in angiogenesis, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF) and fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) [14], VEGF has been identified as the most crucial. VEGF is relatively specific to endothelial cells, and has a non-redundant role during the ‘angiogenic switch’ (the critical point where tumors begin to induce angiogenesis) [14,15]. VEGF regulates several endothelial cell functions, including mitogenesis, vascular tone (inducing hypotension) and vessel permeability [16], as well as inducing the production of plasminogen activators and proteases that help to degrade the basement membrane and allow for formation of new blood vessels [17]. Hypoxia, the hypoxia-inducible factor HIF-1, and other GFs and cytokines, regulate the transcription of erythropoietin and VEGF [16]. The vasoactive and angiogenic functions of VEGF are mediated primarily through VEGFR-2 [16]. VEGFR subsequently activates multiple signaling pathways (Ras/MAPK, FAK, PI3K/Akt, PLCγ) [18], which leads to angiogensis. Further GFs such as basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), PDGF and TGF-β help to stabilize newly formed blood vessels by recruiting pericytes and smooth muscle cells [1,19].

Figure 1. This schematic diagram depicts the angiogenic and antiangiogenic responses at a capillary level.

The cancer cells in tumor tissue secrete angiogenic growth factors that bind to their respective receptors on the endothelial cells lining the capillaries, leading to recruitment of disorganized blood vessels infiltrating the tumor. This leaky vasculature allows entry of the systemically injected vector (e.g., a PEGylated nanoparticle) into tumor tissue, whereas the vector cannot pass across the mature walls of normal tissue vessels. This results in passive targeting of the tumor by the enhanced permeability and retention effect. Antiangiogenic drugs, such as VEGF-TRAP and bevacizumab, block the angiogenic effect of the growth factors. Therapeutic angiogenesis for the treatment of ischemic diseases or vascularization of a tissue-engineered construct is achieved by controlled local delivery of proangiogenic factors using a synthetic delivery scaffold (e.g., fibrin hydrogel loaded with non-covalently or covalently bound growth factors).

1.1 Tumor angiogenesis and therapy

Overexpression of oncogenes or downregulation of tumor-suppressive genes resulting in aberrant, proliferative cells is essential, but not sufficient, for the development of a lethal tumor. Tumor angiogenesis is crucial for the growth and persistence of tumors and metastases. This was first described in 1971 by Judah Folkman, who observed that tumors could only grow to 2 mm in diameter without the growth of new blood vessels [11]. Two millimeters is the distance that oxygen can diffuse through tissue [20]; tumors need blood vessels to supply the oxygen and nutrients necessary for survival and proliferation [11]. Folkman further postulated in 1971 that a ‘tumor-angiogenesis factor’ (TAF) induces blood vessel growth and that inhibition of TAF may halt tumor progression, which he termed ‘antiangiogenic therapy’ [11].

Compared with cancer cells, endothelial cells in malignant tumors are genetically stable, non-malignant and rarely drug-resistant, making them a relatively stable target [21]. Destroying the tumor vasculature can also amplify a drug’s antitumor effect on a per-cell basis [22]. Antiangiogenesis can initially help to ‘normalize’ tumor vasculature, increase tumor perfusion and alleviate tumor hypoxia, thereby increasing the efficacy of conventional anticancer therapies if both antiangiogenic and anticancer therapies are carefully scheduled [23]. At later time points, VEGF inhibition induces tumor hypoxia as more of the tumor vasculature is starved [24].

Many angiogenic inhibitors have been developed, and several, such as bevacizumab [25], ranibizumab [26], pegaptanib [27], aflibercept [28], cetuximab [29,30], panitumumab [31], trastuzumab [32,33], gefitinib [34], erlotinib [35], sorafenib [36,37], sunitinib [38,39], temsirolimus [40] and everolimus (Table 1) [41], have passed or are close to passing FDA approval and are being utilized in therapy for various cancers and AMD. In addition, a large number of chemotherapeutics developed for cancer were later shown to have antiangiogenic properties, especially when given often at lower doses in ‘metronomic chemotherapy’ [42]. However, the current therapies on the market mostly target VEGF, its receptor, or the tyrosine kinases that phosphorylate its receptor. As angiogenesis is a result of the interplay between several pro- and antiangiogenic factors, simultaneous targeting of several proangiogenic signaling cascades (rather than just VEGF) should be one of the most promising antiangiogenic approaches [15].

Table 1.

Angiogenic inhibitors.

| Drug (trade name) | Target | Type of molecule | FDA-approved target(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bevacizumab (Avastin®) [25] | Anti-VEGF receptor | Humanized mAb | mCRC, NSCLC, advanced breast cancer |

| Ranibizumab (Lucentis®) [26] | Anti-VEGF receptor | mAb fragment | Wet AMD |

| Pegaptanib (Macugen®) [27] | Anti-VEGF receptor | PEGylated anti-VEGF aptamer | Wet AMD |

| Aflibercept (VEGF Trap) [28] | Binds/sequesters VEGF-A and PLGF | Fusion protein | Wet AMD |

| Cetuximab (Erbitux®) [29,30] | Anti-EGFR | Chimeric IgG1 mAb | mCRC, head and neck cancer in KRAS-wt patients |

| Panitumumab (Vectibix®) [31] | Anti-EGFR | Fully humanized IgG2 mAb | mCRC |

| Trastuzumab (Herceptin®) [32,33] | Anti-HER-2 | Humanized IgG1 mAb | Breast cancer |

| Gefitinib (Iress™) [34] and erlotinib (Tarveca®) [35] | RTKI of EGFR | Oral small molecule | NSCLC, pancreatic cancer in EGFR + patients |

| Sorafenib (Nexavar®) [36,37] | RTKI of VEGFR-1,2,3, PDGFR-β, and Raf-1 | Oral small molecule | aRCC, advanced hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Sunitinib (Sutent®) [38,39] | RTKI of VEGFR-1,2,3, PDGFR-β, and RET | Oral small molecule | aRCC, GIST |

| Temsirolimus (Torisel®) [40] | mTOR* | Oral small molecule | aRCC |

| Everolimus (Afinitor®) [41] | mTOR* | Oral small molecule | aRCC |

Inhibits cell division, halts growth signaling, and reduces hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1 and HIF-2α) and VEGF expression.

AMD: Age-related macular degeneration; aRCC: Advanced renal cell carcinoma; EGFR: Epidermal growth factor receptor; mAb: Monoclonal antibody; mCRC: Metastatic colorectal cancer; NSCLC: Non-small-cell lung cancer; RTKI: Receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor; VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor.

1.2 Age-related macular degeneration biology and therapy

AMD is the leading cause of blindness in the elderly and is marked by loss of central vision. It is the most common of a large number of inherited and acquired diseases, collectively called macular degeneration (MD) [43]. AMD can be split further into two main forms, exudative/wet (or choroidal neovascular) and non-exudative/dry. Wet AMD is less common but is a leading cause of blindness [44]. Dry AMD results from atrophy of retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), which leads to photoreceptor atrophy [45]. The wet form is an advanced form of AMD and is treatable with antiangiogenic drugs. Choroidal neovascularization (CNV), the formation of new blood vessels from the choroids of the eye, leads to leakage of blood and serum, which damages the retina by stimulating inflammation and scar formation. This damage to the retina causes central vision loss and, eventually, blindness if left untreated.

Neovascular AMD results from an interplay of genetic, metabolic and environmental factors [46]. However, although the exact causes remain an active research area, it is known that angiogenesis and vascular imbalance play a central role in this disease, importantly involving VEGF. Many cells of the eye produce VEGF, including RPE cells, pericytes, endothelial cells, glial cells, Muller cells and ganglion cells [47]. In addition to stimulating blood vessel growth, VEGF can also stimulate endothelial cells to produce matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which can degrade extracellular matrix and allow new vessels to grow into tissue [47]. It has been demonstrated that VEGF overexpression in mouse models and in human studies leads to CNV [46]. Other molecular factors are also important in AMD, including pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF), bFGF and angiopoietins [47]. Stimuli resulting from hypoxia, ischemia, inflammation and oxidative stress (all of which can accumulate with age) can influence the production and balance of these factors.

Recent successful treatments of AMD have been developed that target these relevant effectors, specifically treating blood vessel growth by targeting VEGF. As with cancer treatments, improved clinical results might be achieved through combination therapy that targets multiple GFs.

1.3 Proangiogenic therapy

Acute oxygen shortage in tissues leads to ischemia, resulting in impaired organ functionality, wound healing ability and tissue regenerative capacity. Ischemic tissues are deficient in crucial angiogenic GFs and ECM adhesion sites for recruitment, migration and differentiation of vessel-forming cells. Ischemia-related pathologies exist most commonly in patients suffering from cardiovascular and diabetic conditions, including myocardial ischemia, coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease and critical limb ischemia [19]. Tissue implantation is another procedure in which successful outcomes depend on establishing a robust angiogenic response [48]. Engineered tissue constructs or grafts are limited at present to avascular tissues or thin tissue owing to limitations in perfusion to cells in the graft. Wound healing in ageing patients can also greatly benefit from proangiogenic approaches [49–51].

The rapidly evolving field of regenerative medicine offers promising approaches to repair, reconstruct and heal damaged tissues, and restore their normal function in situ. One approach is to use tissue engineered biomaterials as ECM scaffolds that organize cells into three-dimensional constructs and present stimuli to communicate with the native cells to stimulate growth and healing of the diseased tissue. The size and viability of the constructs is limited by the perfusion of blood for exchange of gas and nutrients with the cells. In vivo, these implanted scaffolds require rapid vascularization for cell survival. Therapeutic angiogenesis aims to increase blood perfusion through ischemic areas within constructs or tissue by stimulating the patients’ endogenous cells at the molecular level [52]. Traditionally, therapeutic angiogenesis has been achieved by delivering angiogenic molecules either as recombinant proteins or as genes (in naked form or using carrier vectors) to help reconstitute the endogenous angiogenic potential of ischemic tissues.

In this review, current approaches to controlled delivery of antiangiogenic treatments for cancer and ocular neovascularization and proangiogenic treatments for tissue engineering and cardiac therapy are focused on.

2. Drug delivery systems

Synthetic and biological materials have been studied in the development of safe and effective drug delivery systems. The chemical and physical properties of synthetic materials, including polymers, are often easier to control, but their biocompatibility must be carefully assessed. Biological materials already possess many desired properties but may be more difficult to modify or manufacture as well as being potentially immunogenic. Strategies under current investigation in the field of drug delivery are discussed below and summarized in Table 2, with particular focus on those that promote or suppress angiogenesis.

Table 2.

Drug delivery systems and representative examples and applications thereof.

| Delivery system |

Examples | Clinical uses/potential applications |

|---|---|---|

| Free drug | Small molecule drug against receptor tyrosine kinase [138] | Sunitinib: advanced renal cell carcinoma |

| Whole antibody against VEGF [25] | Bevacizumab: mCRC, NSCLC, advanced breast cancer | |

| Antibody Fab’ fragment against VEGF [26] | Ranibizumab: exudative AMD | |

| Whole protein rhPDGF [194] | Becaplermin: proangiogenesis in diabetic ulcers | |

| Protein with VEGFR-binding domains and Fc antibody region [168] | VEGF-TRAP: antiangiogenesis in tumors and exudative AMD | |

| Protein regulating ocular blood vessel growth [198] | adPEDF: AMD | |

| Drug-delivery agent conjugates | RGD sequences bound to drug [199] | EMD 121974 (Cilengitide): drug targeted to vasculature for melanoma, glioblastoma, prostate cancer |

| Interferon-α bound to PEG [200–202] | Pegasys: antiviral PegIntron: antineoplastic |

|

| Fab’ fragment against VEGFR-2 conjugated to PEG [158] | CDP791: inhibits VEGF signaling in non-squamous NSCLC | |

| PEGylated RNA aptamer targeting VEGF [27] | Pegaptanib: exudative AMD | |

| Implanted depots | VEGF, bFGF, or TGF-β encapsulated in collagen or gelatin hydrogels [60,61,63,64] | Proangiogenic tissue engineering scaffolds |

| Cannula depot injection of anecortave acetate [47] | Controlled release formulation of angiostatic steroid for AMD | |

| Liposomes | Cationic liposomes containing paclitaxel or oxaliplatin [149,150] | Targeting to tumor vasculature for cancer chemotherapy |

| RGD-conjugated liposomes containing doxorubicin [55] | ||

| Biodegradable micro- and nanoparticles | PLGA, PLA, PCL, polyanhydride, alginate, or gelatin particles [69–72] | Injectable or embedded vehicles for long-term delivery of proteins, mucleotides, or small-molecule drugs |

| DNA, RNA, or oligonucleotides complexed with polycations [106] | Self-assembled nanoparticles for gene delivery | |

| Non-degradable nanoparticles | Gold or iron-oxide nanoparticles [128–130,132,134] Mesoporous silicon microparticles [125,127] |

Magnetic imaging, drug delivery, thermal therapy Intravenous delivery of the rapeutics |

| Cell-based systems | VEGF-transfected CHO cells embedded in biodegradable polymer [121] | Proangiogenic factors secreted by cells within tissue engineering scaffolds |

AMD: Age-related macular degeneration; bFGF: Basic fibroblast growth factor; CHO: Chinese hamster ovary; mCRC: Metastatic colorectal cancer; NSCLC: Non-small-cell lung cancer; rhPDGF: Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor; VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor.

2.1 Drug-agent conjugates

Perhaps the simplest drug delivery system in concept is the direct conjugation of a drug to a delivery agent. As poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) has been shown to increase circulation time after systemic delivery, several therapeutics have been PEGylated with the goal of avoiding biological clearance mechanisms, some of which have been translated to the clinic or are in clinical trials. Also in use are antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) for specific targeting, such as blocking angiogenesis by using cytotoxic drugs bound to antibodies against markers of tumor vasculature [53]. Adhesive peptide moieties such as arginineglycineaspartate (RGD) sequences can be used to localize a drug carrier to desired tissues [54,55]; because RGD sequences bind to integrins, this method has been used to target vasculature and suppress angiogenesis [56]. Other delivery conjugates bind to a therapeutic in order to increase solubility or improve biodistribution, as in the case of Abraxane®, in which the cancer drug paclitaxel is bound to albumin in order to increase its solubility and thereby reduce solvent-mediated toxicity [57].

2.2 Implanted drug-loaded materials

Another strategy for drug delivery is the use of implanted depots, usually made of biological or synthetic polymers that are loaded with a therapeutic. An advantage of this type of system is its suitability for localized delivery. Generally, as in the case of the GLIADEL® wafer made of poly(carboxyphenoxy propane:sebacic acid) discs loaded with bis-chloronitrosourea (BCNU) and used to treat glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) [58,59], the depot is implanted directly at the site of the tissue to be treated. This eliminates the need for targeting mediated by specific interactions between chemical or biological moieties. Furthermore, drug-loaded depots can themselves be substrates for cell growth, as in the case of GF-loaded hydrogels [60–62]. These can be used as tissue engineering scaffolds that provide specific cues for cell survival and proliferation, wound healing, or angiogenesis [63,64]. One concern with implantable reservoirs is the potential for local inflammation or foreign body response [65,66]. They are also limited for use in systemic drug delivery [67,68] unless the loaded drug can permeate freely through the matrix.

2.3 Microparticles and nanoparticles for drug delivery

An alternative to large, implanted drug reservoirs is a micro- or nanoparticulate system. In many cases, these are small enough to be injected, reducing injury resulting from surgical implantation. Among the frequently investigated synthetic polymers are polyesters, including poly(glycolic acid) (PGA), poly(lactic acid) (PLA), poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL), and derivatives or copolymers of the above, such as poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA). These degrade hydrolytically under physiological conditions [69,70] and are biocompatible in vitro and in vivo [71]. They are used in nanoparticulate delivery of proteins, small molecules and genes [72,73], as well as microparticulate delivery of proteins and small molecules [71,74,75]. In one case, VEGF and dexamethasone were released slowly from PLGA particles to encourage angiogenesis while minimizing local inflammation [76]. The drug release kinetics, degradation, biodistribution and clearance of synthetic particles are dependent on several factors, including size, geometry, charge, surface chemistry, encapsulation procedure and the encapsulated drug itself [77–80]. Other than direct injection, particles can also be embedded within a larger mesh, thereby providing localized delivery similar to implantable systems while also allowing for a wider biodistribution as particles are released by diffusion or degradation of the mesh [81–83]. One difficulty with particulate-based systems, however, is their tendency to be cleared relatively quickly through the liver, spleen and kidneys in a size-dependent manner [84,85]. Though circulation time can be lengthened (by PEGylation to form ‘stealth’ particles [86]) and their targeting can be tailored (by changing the size or geometry of the particles and changing the surface chemistry [79,87,88]), for many systems, an ideal in vivo distribution has yet to be achieved.

Amphiphilic lipids, surfactants, or block copolymers constitute another form of drug delivery. Self-assembly of amphiphiles into colloids causes micelle formation, in which a lipophilic core is isolated from the surrounding aqueous phase by an external hydrophilic shell or corona [89]. A bilayer of these molecules can form vesicles classified as liposomes with hydrophilic moieties both at the core and in the surrounding corona, while the lipophilic moieties associate within the bilayer. The biphasic character of these molecules allows them to serve as vehicles for either hydrophilic or lipophilic drugs [90–">90–92] and techniques can tailor the particles’ size, lamellarity, fluidity and hydrophobicity [93–96]. Liposomes were found to be effective in targeting the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS) because they were easily captured by MPS cells and removed from circulation [97,98]; this short lifetime in the bloodstream is a disadvantage, however, for targets beyond the MPS. Altering surface charge or size, conjugation of surface molecules such as PEG, and coadministration of suppressive drugs have been shown to alleviate this problem to some degree [94,99,100]. Similar to the surfactant- and lipid-based micelles and liposomes are nanocapsules and polymersomes. Nanocapsules have a lipophilic interior consisting of the lipophilic block of a copolymer, which serves as a drug reservoir and is surrounded by a hydrophilic core, whereas polymersomes are composed of bilayers, similar to liposomes [101]. Nanocapsules and polymersomes are made of semi or totally synthetic copolymer amphiphiles, which can be of greater molecular mass than naturally occurring lipids [102]. These differences impart a more fluid, dynamic character to liposomes and micelles that are suitable for many biological processes [103], whereas nanocapsules and polymersomes often display more stability than fluidity [104], in addition to the flexibility granted by the ability to control chemical properties of the polymers [102,103].

Cationic biomaterials, including both synthetic and biological polymers, have been used to form complexes with nucleic acids for the purpose of nanoparticulate gene delivery. Cationic moieties in polymers, including polyethyleneimine [105,106], chitosan [107], polyamidoamines [108] and poly (β-amino esters) [109,110], can interact with anionic DNA, RNA, or oligonucleotides. The polycations mediate transport into the cell, through degradative cellular compartments, and into the cytoplasm, nucleus, or other compartments where the cargo is active [106]. These materials have recently been studied for their potential to treat or cure many diseases, including those whose genetic basis is known but whose downstream molecular effectors are hard to target. Polymeric gene delivery has gained attention as an alternative to viral gene delivery, which suffers from limited cargo capacity, immune response, and the possibility of insertional mutagenesis [111]. Recent work on polymeric gene delivery to human endothelial cells, for example, has demonstrated virus-like efficacy along with minimal cytotoxicity [112–114]. In addition to these particles’ potential to regulate therapeutically any gene of known sequence, gene delivery can also be used as a first step in cell-based drug delivery systems.

2.4 Cell-based delivery systems

ex vivo gene delivery can be used as a precursor to cell-based, proangiogenic drug delivery. In one study, human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) were transfected with polymeric particles to express VEGF at high levels and subsequently seeded onto polyester scaffolds in order to promote angiogenesis in vivo [115]. Success in a similar system was seen with VEGF-expressing endothelial cells and adipose-derived stromal cells [116]. Cell-based systems are attractive because drug dose and release kinetics can be controlled over long periods of time of up to nearly a year [117], provided that the cell stably expresses the desired therapeutic. Other studies have used cells as a method of delivering nanoparticles, allowing for a two-stage release of drugs or proteins [118], particles that serve as MRI contrast agents [59], or particles that enhance radiation therapy [119].

Delivery of cells can also be combined with other biomaterials such as hydrogels or other polymer capsules [115–117,120] that encapsulate cells. In one study, Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells transfected with VEGF cDNA and subsequently encapsulated in alginate and poly(l-lysine) microspheres were shown to increase angiogenesis after implantation in mice [121]. Cell-based therapies, however, pose extra safety concerns, including the potential for inflammation, immune response or rejection of the graft, and unanticipated host–donor cell interactions. There are also questions of which cells to use and how to harvest enough for therapeutic purposes and dose regulation, especially for cases in which the secreted protein might have an off-target effect on the secreting cell itself [122–124].

2.5 Non-degradable particles

Although a great deal of research has focused on biodegradable particles, non-degradable particles are also studied for delivery of therapeutics. Mesoporous silicon microparticles can be loaded with proteins and other therapeutics, including insoluble drugs [125], and their microstructure allows surface interactions to be minimized, reducing damage to a drug during the loading process [126]. Drug delivery systems like these can be nested, such as with mesoporous microparticles that encapsulate nanoliposomes that are themselves loaded with small interfering RNA to create multistage delivery systems [127]. Another class of non-degradable particles is metal nanoparticles, notable for their monodispersity, small sizes, and magnetic and thermal properties. Iron oxide nanoparticles have been used as magnetic resonance contrast agents as they accumulate passively in tumor vasculature [128,129] and can be encapsulated in lipids or polymeric particles [130]. They can also be conjugated to ligands such as RGD that can actively target the particles to areas of high angiogenesis, such as tumors [131]. Gold nanoparticles, in part owing to their relative biocompatibility, have been used as vehicles for gene or drug delivery [132,133] and for thermal therapy [134]. Although many of these particulate systems allow greater control over fabrication and processing variables, many of them are also limited by their toxicity [135,136].

3. Antiangiogenic drug delivery systems

3.1 Anticancer drug delivery concepts and systems

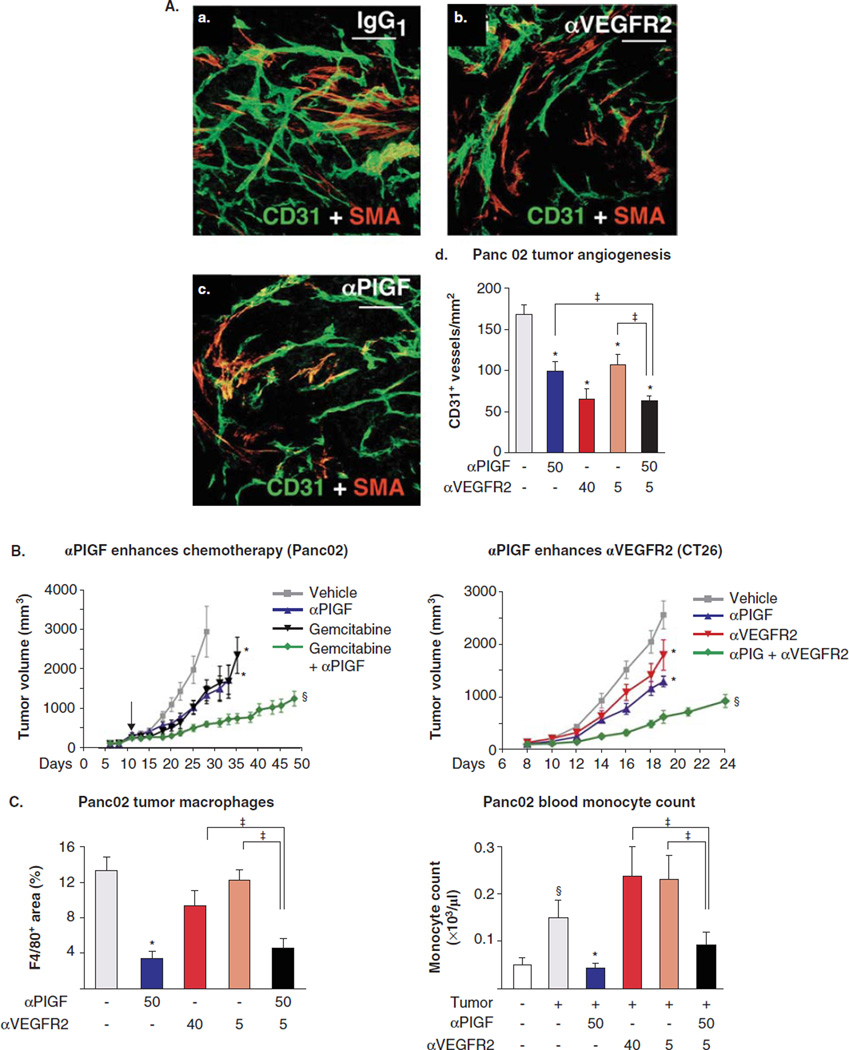

A key concept when considering the development of controlled release formulations for antiangiogenic therapy is that many angiogenesis inhibitors have a biphasic dose–response curve [137]. As a result, maximum tolerated dose is not the paradigm to use for antiangiogenic therapy [15]. As an example, a high-dose regimen (120 mg/(kg day)) of sunitinib leads to a compensatory increase in proangiogenic proteins and reduced survival and increased metastases in a mouse model, whereas a lower dose regimen (40 – 60 mg/(kg day)) has the opposite, beneficial effect [138,139]. Combinations of therapies, such as blocking the signaling of more than one GF, have also been shown to be more effective in some cases (Figure 2A, B). For example, researchers have used simultaneous administration of antibodies against both VEGFR-2 and PlGF to suppress tumor growth as well as an antiangiogenic antibody to enhance the efficacy of a conventional chemotherapy drug. This can be especially useful when a certain type of tumor is known to be resistant to one treatment but not another, or when treatment with a low dose of two therapies is less toxic to healthy cells than a high dose of either one of the individual therapies [140]. In other cases, combination therapy is no more effective than the single therapy (Figure 2C), highlighting the importance of a systems-level understanding of the effect of one pathway on another [141].

Figure 2.

A, a – c. Antibodies against PlGF and VEGFR2 inhibit tumor angiogenesis compared with nonspecific antibody IgG1, particularly in combination (A, d). PlGF antibody also enhances the effect of gemcitabine, measured by tumor volume (B), and inhibits excessive recruitment of macrophages; the latter is not enhanced by coadministration of anti-VEGFR-2 (C).

Adapted with permission from [140].

Nanoparticles can be effective at targeting tumor vasculature owing to specific and nonspecific biochemical and biophysical mechanisms. One of the advantages of nanoparticle-mediated delivery is due to the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect (Figure 1). Nanoparticles that are ~ 50 – 200 nm have been shown to accumulate in tumors, provided they have a long circulation time, as a result of the leaky vasculature and absence of a draining lymphatic system present in the tumor bed [142–144]. Active targeting of endothelial molecules that are upregulated in response to high levels of angiogenesis can also be used for extra specificity. The size exclusion caused by leaky vasculature, as well as the increased angiogenesis at tumor sites, has been exploited to image tumor angiogenesis by means of metallic nanoparticles [145]. In this case, the passive targeting of nanoparticles by means of the EPR effect was enhanced by active targeting via αVβ3 integrin on the nanoparticles. Another example of an approach combining EPR with remote activation is that of metallic nanoshells, which accumulate in tumor vasculature before being activated externally by near-infrared light for thermal ablative therapy [134]. Other for-mulations include the conjugation of integrin and VEGF receptor antagonists, which target sites of angiogenesis and also suppress signaling through receptors to inhibit vessel growth [146].

The charge of a drug or delivery vehicle affects its ability to penetrate tissue, accumulate in desired sites, and escape rapid clearance from the bloodstream [147,148]. Experimental antiangiogenic therapies have included cationic liposomes, which can target neovasculature, to deliver the cancer drugs oxaliplatin [149] or paclitaxel [150], with or without PEGylation to increase circulation time. Both of these showed not only the expected antitumor activity from the platinum analogue drugs, but also a marked antiangiogenic effect.

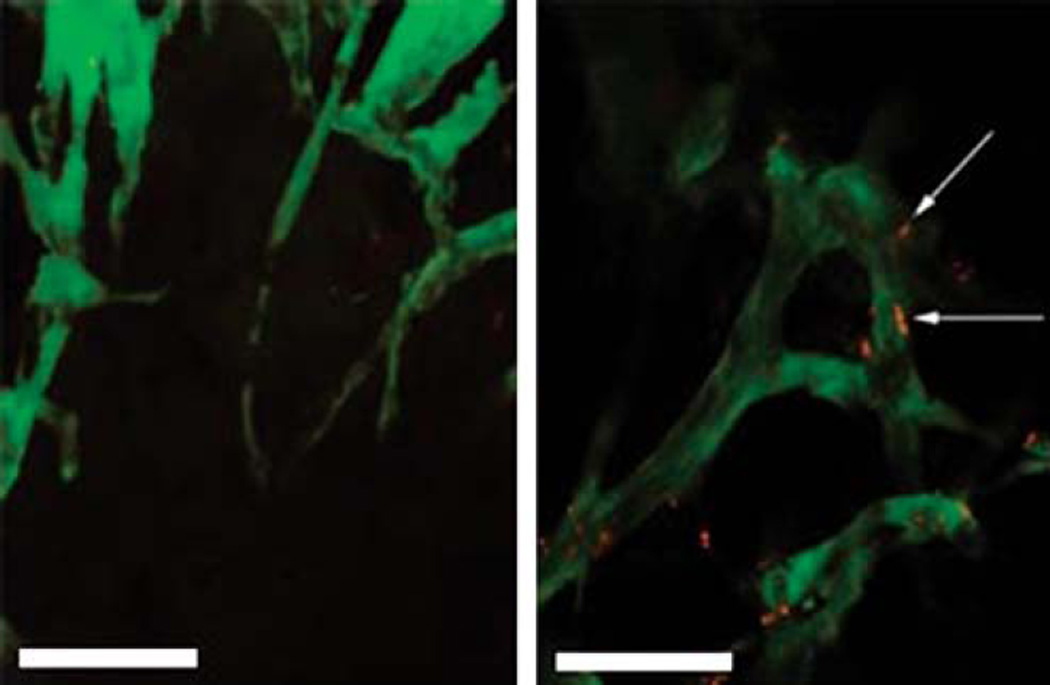

The abnormal vasculature of tumors, although potentially useful for drug delivery applications, can also be a hindrance. For example, one study found that tumor vessels composed of cells with heterogenous mutations caused preferential extravasation of 90-nm liposomes (Figure 3) [151]. This could potentially contribute to tumor recurrence from the cells in the parts of the tumor mass that were not exposed to extravasating drug-loaded vehicles. Another challenge to cancer drug delivery is the increased interstitial pressure in the tumor space [152] and decreased perfusion near the center of the tumor mass [153]; as a result, most unmodified particles or other delivery agents can penetrate only a small distance. Peptide sequences that cause tumor penetration have been identified [154], and efforts are being made to use this principle to enhance the effect of peptides to tumor endothelium [155]. Also contributing to the problem of low tumor penetration is the high expression of certain collagens by tumor endothelial cells [156]. The difficulties in targeting the core of tumors further motivate the approach of targeting tumor vasculature, as it is more easily reached.

Figure 3. Tumor vasculature is highlighted by green fluorescence, overlaid with red-fluorescent liposomes.

The two sections shown are 50 µm apart in the tumor tissue, with a large difference in liposome migration from one part of the tumor to the other. Scale bar: 50 µm.

Adapted with permission from [151].

Recent studies exploring overexpressed genes [157] on tumor endothelium have shown that the collagens that may prevent tumor penetration can also be used as targets for drug delivery. For example, a di-Fab’ fragment-PEG conjugate called CDP791 that targets VEGFR-2 was recently shown to prevent VEGF signaling and reduce angiogenesis in a Phase II clinical trial for the treatment of non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer [158]. A review of these delivery challenges makes it clear that simultaneous targeting of multiple barriers may improve the likelihood of success of antiangiogenic treatments delivered to tumors.

3.2 AMD drug delivery concepts and systems

There are at present two anti-VEGF treatments approved in the US for AMD: pegaptanib and ranibizumab. Bevacizumab, which is approved for some cancers, is also routinely used off-label for AMD. Bevacizumab is a murine recombinant, humanized, monoclonal antibody that has been shown to bind to and inhibit all known isoforms of VEGF [46]. Ranibizumab is an antibody fragment developed from the same murine antibody as bevacizumab, also binding to all known isoforms of VEGF [46]. The constant region was eliminated to improve retinal penetration and reduce inflammation response. Specific amino acids were substituted to increase its binding affinity to VEGF [46]. It is administered by means of intravitreal injections once a month and has a half-life of 3 days [159]. Both have been found to work similarly well, although off-label bevacizumab use is considerably less expensive (~ $50 per dose as compared with ~ $2000 per dose) [160,161].

Long-term anti-VEGF therapy can cause detrimental effects, however, and frequent intravitreal injections could damage the eye [43]. These treatments do not help all patients, as ~ 20% still lose vision over time. Newer treatments include VEGF-TRAP, a recombinant protein that targets VEGF rather than the VEGF receptor [162], and a recently completed Phase III trial has found it to be comparably effective to ranibizumab.

Improving the route of drug delivery to the back of the eye is a central challenge that needs to be addressed. There are various routes of entry into the eye, including topical application, transscleral delivery, intravitreal injection and systemic delivery. Topical application is the least invasive of these methods. However, drugs delivered topically must cross corneal epithelial layers, avoid aqueous humor clearance mechanisms and diffuse all the way to the posterior eye [163]. Transscleral delivery is relatively less invasive and provides a more direct route to the posterior segment as compared with topical application. It still must pass several barriers, including tissue penetration, avoiding clearance due to circulation, and avoiding metabolic activity of these cellular barriers [164].

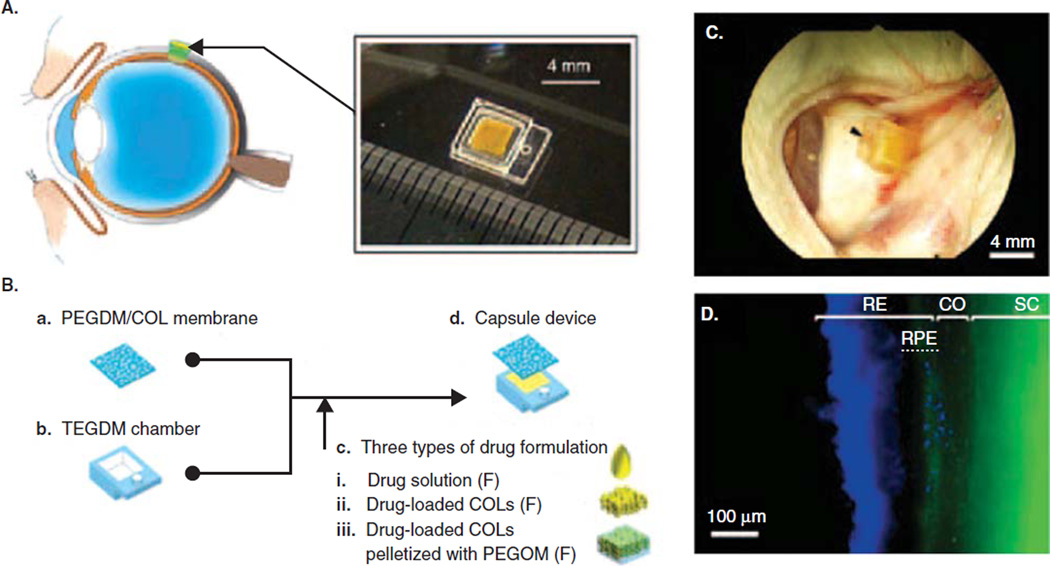

Intravitreal injections allow drugs or implants to be delivered directly into the vitreous humor. This method is also the most invasive, can cause trauma to the eye, and as a result leads to reduced patient compliance [163]. Systemic delivery has the advantage of being easier for patients than intravitreal or transscleral delivery, as well as the potential ability to deliver higher doses. The limitations include increased risks for side effects in other tissues, as well as the difficulty of crossing the blood–retinal barrier [165]. The drugs that have already been approved are usually delivered by means of intravitreal injections, as this is the most direct route. However, depending on the delivery platform, other routes might be used. For example, a drug delivery reservoir implanted in the sclera [166] contains a controlled-release membrane fabricated from cross-linked polyethylene glycol with interconnected collagen microparticles embedded within the membrane (Figure 4). A constant and controllable release rate was obtained by tuning the membrane’s chemical and physical properties.

Figure 4.

A. Transscleral drug delivery device. B. Device made with TEGDM reservoir and PEGDM/COL membrane that can be loaded with various drug solutions. C. Capsule sutured onto rabbit eye sclera 3 days after implantation. Arrowhead indicates suture site. D. Distribution of model drug FD40 (green) around implantation site at day 3. Cell nuclei dyed stained blue. FD40 reaches RPE.

Adapted with permission from [166].

CO: Choroids; RE: Retina; RPE: Retinal pigment epithelium; SC: Sclera.

Extending the half-life of the therapeutic is also key, as it can reduce the dosage, frequency of injections, costs, and negative patient outcomes. As mentioned previously, PEGylation can increase half-life, as in the case of pegatanib, an approved AMD therapy. This PEGylated aptamer, made of short RNA strands with three-dimensional conformation, binds to one specific isoform of VEGF [27].

In another strategy, an antiangiogenic integrin antagonist, C16Y, peptide was encapsulated within PLA/PLA-PEO nanoparticles [167]. Intravitreal injections led to improved antiangiogenic outcomes attributed to the increased half-life of the peptide in the eye. Also, nanoparticles were observed to penetrate the retina and localize to the retinal pigment epithelial layer. The identification of several other antiangiogenic peptides has also been achieved through computational and experimental methods [168]. These peptides inhibit proliferation and migration of human umbilical vein endothelial cells, as well as reduce tumor size in in vivo cancer models [169]. Encapsulation of these new agents in particles may make possible combinatorial delivery, long-term activity and enhanced efficacy.

There has been extensive work on drug depots in the context of ocular drug delivery for antiangiogenesis. Molokhia et al. developed a capsule drug ring (CDR) that can be implanted in the peripheral lens capsule during cataract surgery [170]. This semipermeable poly(methyl methacrylate) depot can release bevacizumab and other drugs in a continuous and controlled fashion and may allow for the replacement of intravitreal injections. This system is still being tested in animal models and there are clinical trials underway for other implantable drug delivery systems. An intravitreal polymeric non-biodegradable matrix insert system has been utilized for the delivery of fluocinolone acetonide to treat diabetic macular edema [171]. The inserts released the drug consistently for over a year in patients. Other implants degrade over time, reducing any possible future complications in the eye [172]. Systemic delivery may also be possible by temporarily easing the blood–retinal barrier [173], as shown in the delivery of RNAi to mice.

4. Proangiogenic therapy

Members of the VEGF superfamily have been evaluated extensively in preclinical studies for their proangiogenic potential in animal models of myocardial and limb ischemia, as they play a key role in angiogenesis. The use of recombinant protein therapy presents critical challenges with respect to difficulty in maintaining adequate levels of protein in the ischemic site and high production costs. An alternative focus in therapeutic angiogenic strategies is gene therapy using viral or non-viral vectors [174,175]. In the context of ischemic diseases, gene therapy is utilized to deliver genes encoding angiogenic GFs to ischemic tissues to stimulate revascularization and enhance organ function and graft survival (Figure 1). Adenoviruses are the most common viral carrier used for angiogenic therapies [176], although the immunogenic and mutagenic risks involved with the use of viruses have motivated the development of non-viral vectors. Recently, combination therapy that simultaneously uses multiple GFs, cell therapy, bioresponsive scaffolds and upstream activators for controlled drug delivery has shown promising results in animal models, suggesting that such combination approaches may constitute a major part of future proangiogenic clinical studies.

4.1 Proangiogenic strategies in cardiovascular and peripheral vascular disease

Proangiogenic gene therapy has shown promise for the treatment of myocardial ischemia in animal models as well as in human trials [176]. The first gene therapy study for cardiac disease was conducted in angina patients by delivering VEGF165 plasmid by epicardial injection following thoractomy. Subsequent studies have explored less invasive routes to administer plasmids, such as by means of intracoronary infusion. However, the delivery of naked VEGF plasmid has failed to have significant efficacy in clinical trials. Biodegradable polymers have been investigated for non-viral gene delivery as a safer alternative to viral vectors. To reduce carrier-associated toxicity, degradable designs have been proposed, including hydrolysable ester bond-containing polymers and reducible disulfide bond-containing polymers [110]. A reducible disulfide poly(amido ethylenediamine) (SS-PAED) was used as a carrier for VEGF plasmid delivery for myocardial ischemia therapy in vitro and in an in vivo rabbit model [177]. Advantages of this system include stability in aqueous environment, low cytotoxicity and increased efficacy compared with non-degradable polyethyleneimine, ability to compact DNA, endosomal buffering capacity, and, importantly, the ability to degrade and release the genetic material in the reducing intracellular compartment. In rat cardiomyoblasts, SS-PAED achieved 16-fold higher luciferase gene expression compared with branched PEI and a transfection efficiency of 57 ± 2%. The efficacy was dependent on the level of GSH, a reducing agent, inside the cell. In the in vivo infarct model, the study reported fourfold increased expression of VEGF at the infarct site compared with negative control injections of SS-PAED/luciferase plasmid.

An early clinical trial for the delivery of VEGF plasmid used a hydrogel-coated angioplastic balloon to treat ischemic limb [178]. The authors reported increased collateral vessel formation and improved flow without any significant side effects. Most subsequent clinical trials have used an intramuscular route to deliver either VEGF or FGF as a recombinant protein or gene to treat peripheral vascular conditions. Recombinant bFGF delivered intramuscularly in peripheral artery disease (PAD) patients was well received without any adverse events, and VEGF165 plasmid injected into the limb muscle of critical limb ischemia patients healed nonhealing ulcers and improved resting pain [179]. However, a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of intramuscular adenoviral gene transfer for treating PAD conducted with 105 patients found no significant difference between high dose, low dose and placebo-controlled groups [180]. Studies have described the use of injectable PLGA nanoparticles for controlled non-viral delivery of VEGF. Mice treated with VEGF-PLGA nanoparticles showed significantly better vessel growth recovery than those treated with saline or VEGF in naked form in a hindlimb ischemia model [181]. The size of the PLGA nanoparticles ranged from 200 to 600 nm and demonstrated sustained release of VEGF for 2 weeks. The release kinetics could be tuned by changing the copolymer ratio used to synthesize the nanoparticles.

4.2 Proangiogenesis using a cellular therapy approach

Cellular therapy has emerged in the last decade as another promising strategy to treat vascular diseases, owing to increased knowledge about the mobilization, differentiation and homing of progenitor cells. Vascular progenitor cells are derived from bone marrow and peripheral blood for their use in the treatment of myocardial infarction and ischemic cardiomyopathy [174]. As only a small number of injected progenitor cells home to an ischemic site, beneficial vascular effects may be due to certain paracrine factors released by these cells. Human cell therapy trials have evaluated the efficacy of bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells, epithelial cells and skeletal myoblasts for treatment of myocardial ischemia and peripheral vascular disease [1,52]. In these trials, cells were delivered by intracoronary or intramyocardial injection for cardiac diseases, and intramuscular and/or intra-arterial injection for peripheral diseases.

In addition to proangiogenic approaches using downstream single GF delivery, another approach being pursued is delivery of factors upstream in the angiogenesis cascade to mediate a stronger response. The transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) is a master regulator responsible for initiating a large number of adaptive responses during hypoxia, including expression of genes encoding angiogenesis-inducing cytokines and their receptors. HIF-1 consists of an oxygen-regulated HIF-1α and a constitutively expressed HIF-1β subunit. The HIF-1α subunit is degraded under normoxic conditions owing to its oxygen-sensitive domain, but its stabilization under hypoxic conditions has been exploited for proangiogenic therapies. The delivery of HIF-1α/VP16 fusion protein has been shown to help recovery of peripheral limb ischemia in animal models, as well as to improve ulcer healing and reduce pain in a Phase I clinical trial with patients suffering from limb ischemia [176]. Recent studies have also combined cellular therapy approaches with angiogenic factor delivery to induce angiogenesis and vasculogenesis simultaneously. Bone marrow-derived angiogenic cells, primed to express integrins to enhance targeting to ischemic tissue were combined with delivery of adenoviruses expressing HIF-1α in a mouse limb ischemia model [182].

4.3 Proangiogenesis and tissue engineering

Rationally designed biodegradable three-dimensional matrices that communicate with endogenous angiogenic cells are being pursued. An interesting case that demonstrates the importance of vascular networks in engineered tissues is that of cartilage, an avascular tissue that has been commonly studied for in vitro tissue engineering [183]. Without the requirement of vascular network formation, it was an early example of tissue that was successfully expanded in vitro from cells seeded on scaffolds and subsequently implanted or injected into human patients to heal cartilage defects [184–">184–186], though these methods still incompletely recapitulate the complex native tissue [187]. In this case, hypoxia caused by the lack of vascular supply may in fact be required, as oxygen tension, HIF-1α, and other factors regulate ECM formation and organization, which is crucial to cartilage mechanics and function [188,189]. Hypoxia also arrests tissue growth; cartilage thickness must necessarily be limited for survival without blood vessels [190]. This observation, and the slow and limited repair capacity of cartilage that has also been attributed in large part to lack of blood supply [191,192], emphasize further the importance of vascularization in growth and healing. Hypoxia is needed for correct formation of cartilage structure; however, the disadvantages of an insufficient blood supply are crippling in other organs for which greater thickness, regenerative ability and mitotic activity are necessary for survival and function.

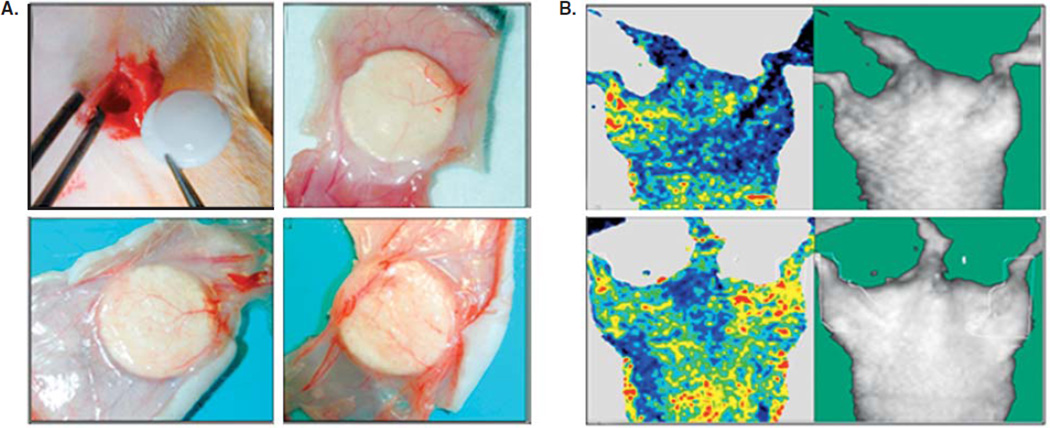

Strategies to vascularize engineered tissue include incorporation of specific adhesion sequences to promote the migration or homing of endogenous angiogenic cells, pre-seeding of endothelial progenitors, and adding a controlled release reservoir of angiogenic GFs (Figure 1). Hydrogel matrices are ideal for this purpose because of their biocompatibility, mechanical properties and resemblance to native ECM [19]. These matrices can act as depots for GFs or pharmacological agents that are released on physiological stimuli, such as hydrolytic or enzymatic degradation. Three-dimensional fibrin scaffolds have been investigated extensively as matrices for delivery of angiogenic drugs owing to their clinical availability and wound healing capacity [19]. Fibrin matrices by themselves lack the mechanical strength needed in certain in vivo applications such as cardiac tissue regeneration where the implant should be capable of handling continuous repetitive stresses. To address this issue, fibrin scaffolds have been combined with synthetic elastomers such as polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) and polyurethanes, which are biocompatible, to impart elasticity and strength. A study evaluated the angiogenic potential of a poly(ether urethane)-PDMS semi-interpenetrating network and GF-loaded fibrin composite scaffold implanted in an ischemic hindlimb of Wistar rats [193]. Immunohistochemical analysis showed higher capillary density after 14 days for the composite scaffold plus GF group than the composite scaffold only group, and laser Doppler perfusion imaging also showed improved blood perfusion in ischemic hindlimb of the composite scaffold plus GF implant group (Figure 5). This study highlights the importance of using biocompatible delivery systems for localized and controlled release of multiple GFs for therapeutic angiogenesis.

Figure 5.

A. Images of scaffolds implanted subcutaneously in the ischemic hindlimb model of a rat taken on day 14 after implantation. The images show that the capillary number is higher in the PEtU-PDMS/Fibrin + GF scaffold implant group (lower right) than in the PEtU-PDMS/Fibrin only group (lower left) and least in the bare PEtU-PDMS scaffold group. B. In vivo images of hindlimb blood perfusion monitored by laser Doppler perfusion imaging in rats. The left limb is the nonischemic control limb and the right limb is the ischemic limb treated with the PEtU-PDMS/Fibrin + GF implant. Images in the upper row were taken immediately after ischemia induction and the lower row images were taken 14 days after scaffold implantation. In colored images, normal blood flow is represented by red and reduced blood flow by blue. Blood perfusion markedly increased 14 days after implantation, as seen in the colored images of the right hindlimb.

Adapted with permission from [193].

The only FDA-approved drug for therapeutic angiogenesis is REGRANEX® gel 0.01% (becaplermin), which is a recombinant human PDGF (rhPDGF) drug used for topical applications to treat lower extremity diabetic ulcers [194]. The rhPDGF helps in recruitment and proliferation of cells that improve wound repair and vessel formation near the affected area. As compared with a placebo gel, becaplermin resulted in greater incidences of complete ulcer healing and closure at ~ 10 weeks and continued to improve with time. The delivery of GFs can also be achieved by administering autologous platelet concentrates. Harvest Technologies’ Smart-PReP platelet concentrate system is the first and only FDA-approved system to isolate patient-specific transfusable platelets that release GFs, including PDGF and VEGF, for about a week to promote wound healing [195]. Unlike these protein-based therapies, there is as yet no FDA-approved gene therapy owing to safety concerns. However, clinical trials indicate encouraging results, particularly for peripheral vascular disease.

A critical aspect of therapeutic angiogenesis is to optimize the dose, duration of expression and timing of factor administration. Non-virally delivered angiogenic factors are expressed for about a week following administration, whereas adenoviral gene expression may last for a few weeks [110,196]. Thus, multiple doses may be needed to sustain the therapeutic level of angiogenic factors until the newly formed vessels mature. The delivery method also dictates how adequately the vector reaches the target site. Intramuscular injection is preferred over intracoronary delivery to avoid complications resulting from improper targeting to healthy tissue and to achieve better targeting in peripheral vascular disease [176]. In the case of cardiac disease, percutaneous endomyocardial delivery has been combined with delivery technologies such as ultrasound in preclinical trials [197].

5. Conclusion

Angiogenesis is crucial not only to normal biology but also to many diseased states, including cancer, AMD and ischemia. Drug delivery paradigms are being developed that combine well-studied principles of material transport and pharmacokinetics with new biomaterials and fabrication methods. Some of these therapeutic systems have been translated to the clinic with success. However, more research is needed to optimize further the delivery of available drugs and to identify new treatment modalities.

6. Expert opinion

Advanced drug delivery systems can benefit therapeutic angiogenesis and antiangiogenesis by increasing specificity, prolonging duration and combining multiple components. As more information is gleaned on a systems-level view of angiogenesis, precision delivery in both time and space of multimodal agents to control angiogenesis will become increasingly important. Drug delivery systems are the enabling technologies to translate this information into new therapies.

Numerous targets have been identified for antiangiogenic therapies, including growth factors and their receptors and ligands localized on tumor vasculature. In the case of cancer, despite the ever-increasing understanding of cancer biology and drug delivery, current therapies are still plagued by inefficiency, systemic toxicity and tumor recurrence. As there are so many factors that contribute to excessive tumor angiogenesis and growth, and because great flexibility is granted through drug delivery approaches, it will be advantageous to consider engineered systems and more than a single pathway to decrease angiogenesis in tumors for maximal therapeutic effect. For example: i) the conjugation of targeting ligands to drugs can increase specificity; ii) encapsulation of multiple drug-agent conjugates in liposomes or polymer nanoparticles can protect the drugs and facilitate extravasation from the bloodstream and into tumor tissue; iii) control of physicochemical properties can further narrow the tissues targeted by the particle and also increase efficiency; and iv) the particle itself can be protected from clearance by conjugation of ‘stealth’ molecules or secondary encapsulation in microparticles or scaffolds. Furthermore, potentially hundreds of lead drug molecules can be formulated together in different combinations into systems that control release dosages and the order of drug release. Similarly, in AMD drug delivery strategies could enable co-delivery of agents for increased potency and reduce the need for repeated intravitreal injections. Such antiangiogenic approaches for both cancer and AMD are now being explored clinically to increase both efficacy and specificity.

The goal of proangiogenic therapies is to deliver successfully key angiogenic factors that stimulate revascularization of an ischemic site. In the context of ischemic diseases, reperfusion improves the function of the diseased organ, whereas in the case of tissue-engineered constructs and tissue implantation, revascularization enhances graft survival. A critical aspect of developing any therapeutic angiogenesis strategy is to optimize the dose, duration of expression and timing of factor administration. According to preclinical data, in non-ischemic tissues induction angiogenesis may be required for a period of weeks or months to allow maturation of newly formed capillaries; in an ischemic environment, this period of dependence on proangiogenic stimulation may be longer [176]. A leading failure of many potential therapies is the limited duration of angiogenic agent expression in the targeted diseased area. Furthermore, improper targeting of angiogenic factors can have deleterious side effects, including retinopathy and build-up of atherosclerotic plaque. To address these issues, it is critical to develop controlled and targeted delivery strategies that can prolong the duration of factor exposure. The clinical success of a proangiogenic therapy may require a patient-specific tailored delivery strategy that accounts for factors such as age, level of tissue damage, route of administration and the native in vivo environment. Rationally designed biodegradable three-dimensional matrices that can act as depots for growth factors and present stimuli to communicate with endogenous angiogenic cells are promising technologies. Combinatorial strategies that use such smart delivery platforms in conjunction with angiogenesis-stimulating cells and growth factors need to be explored further to expedite the successful translation of proangiogenic therapies. For both proangiogenic and antiangiogenic approaches, the use of biomaterials to encapsulate biological molecules and cells greatly enhances efficacy and will lead to many future clinical therapies.

Highlights.

Aberrant angiogenesis is critical for tumor growth, for the development of age-related macular degeneration, and in a variety of ischemic diseases.

Targeting major angiogenic factors, such as VEGF, has resulted in clinically approved therapeutics.

Drug delivery systems can be used to address various limitations of current pro- and antiangiogenic drugs.

Microparticles, nanoparticles and reservoirs are drug delivery systems used in cancer and AMD treatment in order to extend drug half-life, improve targeting and control dosage, among other benefits.

Drug delivery by means of cellular carriers, and in combination with tissue engineering systems, has been utilized for proangiogenic applications.

Future directions with composite drug delivery systems will make possible targeting of multiple factors for synergistic effects.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Edward N and Della L Thome Memorial Foundation, Bank of America NA, Trustee, Awards Program in Age-related Macular Degeneration Research for partial support of this work.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Phelps EA, Garcia AJ. Update on therapeutic vascularization strategies. Regen Med. 2009;4(1):65–80. doi: 10.2217/17460751.4.1.65. • This article is a good review on current advances in vascularization strategies used in the fields of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

- 2.Eichmann A, Pardanaud L, Yuan L, et al. Vasculogenesis and the search for the hemangioblast. J Hematotherapy Stem Cell Res. 2002;11(2):207–214. doi: 10.1089/152581602753658411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Risau W. Mechanisms of angiogenesis. Nature. 1997;386(6626):671–674. doi: 10.1038/386671a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glotzbach JP, Levi B, Wong VW, et al. The basic science of vascular biology: implications for the practicing surgeon. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(5):1528–1538. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ef8ccf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Folkman J. Angiogenesis in psoriasis: therapeutic implications. J Invest Dermatol. 1972;59:40–43. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12625746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moulton KS. Angiogenesis in atherosclerosis: gathering evidence beyond speculation. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2006;17:548–555. doi: 10.1097/01.mol.0000245261.71129.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moulton KS. Inhibition of plaque neovascularization reduces macrophage accumulation and progression of advanced atherosclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4736–4741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730843100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paleolog EM. Angiogenesis in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. 2002;4(Suppl 3):S81–S90. doi: 10.1186/ar575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown RA, Weiss JB, Tomlinson IW, et al. Angiogenic factor from synovial fluid resembling that from tumours. Lancet. 1980;1(8170):682–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin A, Komada MR, Sane DC. Abnormal angiogenesis in diabetes mellitus. Med Res Rev. 2003;23(2):117–145. doi: 10.1002/med.10024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis: therapeutic implications. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:1182–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197111182852108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller JW. Vascular endothelial growth factor/vascular permeability factor is temporally and spatially correlated with ocular angiogenesis in a primate model. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:574–584. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Folkman J. Angiogenesis: an organizing principle for drug discovery? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6(4):273–286. doi: 10.1038/nrd2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bergers G, Benjamin LE. Tumorigenesis and the angiogenic switch. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(6):401–410. doi: 10.1038/nrc1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdollahi A, Folkman J. Evading tumor evasion: current concepts and perspectives of anti-angiogenic cancer therapy. Drug Resist Updat. 2010;13(1–2):16–28. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor: basic science and clinical progress. Endocr Rev. 2004;25(4):581–611. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cross MJ, Claesson-Welsh L. FGF and VEGF function in angiogenesis: signalling pathways, biological responses and therapeutic inhibition. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22(4):201–207. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01676-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giles FJ. The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling pathway: a therapeutic target in patients with hematologic malignancies. Oncologist. 2001;6(Suppl 5):32–39. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.6-suppl_5-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hall H. Modified fibrin hydrogel matrices: both, 3D-scaffolds and local and controlled release systems to stimulate angiogenesis. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13(35):3597–3607. doi: 10.2174/138161207782794158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The Biology of Cancer. 270 Madison Avenue, Garland Science. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis Group LLC; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Browder T, Butterfield CE, Kraling BM, et al. Antiangiogenic scheduling of chemotherapy improves efficacy against experimental drug-resistant cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60(7):1878–1886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu HC, Chang DK. Peptide-mediated liposomal drug delivery system targeting tumor blood vessels in anticancer therapy. J Oncol. 2010;2010:723–798. doi: 10.1155/2010/723798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jain RK. Normalization of tumor vasculature: an emerging concept in antiangiogenic therapy. Science. 2005;307(5706):58–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1104819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ng QS, Goh V, Milner J, et al. Acute tumor vascular effects following fractionated radiotherapy in human lung cancer: in vivo whole tumor assessment using volumetric perfusion computed tomography. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67(2):417–424. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(23):2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenfeld PJ, Brown DM, Heier JS, et al. Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(14):1419–1431. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gragoudas ES, Adamis AP, Cunningham ET, Jr, et al. Pegaptanib for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(27):2805–2816. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dixon JA, Oliver SC, Olson JL, et al. VEGF Trap-Eye for the treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18(10):1573–1580. doi: 10.1517/13543780903201684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(6):567–578. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Cutsem E, Kohne CH, Hitre E, et al. Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1408–1417. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Cutsem E, Peeters M, Siena S, et al. Open-label phase III trial of panitumumab plus best supportive care compared with best supportive care alone in patients with chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(13):1658–1664. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bang YJ, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9742):687–697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61121-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(11):783–792. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103153441101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(10):947–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cappuzzo F, Ciuleanu T, Stelmakh L, et al. Erlotinib as maintenance treatment in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(6):521–529. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(4):378–390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, et al. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(2):125–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(2):115–124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Demetri GD, van Oosterom AT, Garrett CR, et al. Efficacy and safety of sunitinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after failure of imatinib: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368(9544):1329–1338. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69446-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hudes G, Carducci M, Tomczak P, et al. Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(22):2271–2281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, et al. Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9637):449–456. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kerbel RS, Kamen BA. The anti-angiogenic basis of metronomic chemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(6):423–436. doi: 10.1038/nrc1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chakravarthy U, Evans J, Rosenfeld PJ. Age related macular degeneration. BMJ. 2010;340:c981. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nguyen QD, Shah SM, Browning DJ, et al. A phase I study of intravitreal vascular endothelial growth factor trap-eye in patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(11):2141–2148. e2141. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ambati J, Ambati BK, Yoo SH, et al. Age-related macular degeneration: etiology, pathogenesis, and therapeutic strategies. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48(3):257–293. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(03)00030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bressler SB. Introduction: understanding the role of angiogenesis and antiangiogenic agents in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(10 Suppl):S1–S7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lu M, Adamis AP. Molecular biology of choroidal neovascularization. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 2006;19(3):323–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ohc.2006.05.001. • A detailed review on the molecular biology of choroidal neovascularization and the treatments that target this process.

- 48.Hegen A, Blois A, Tiron CE, et al. Efficient in vivo vascularization of tissue-engineering scaffolds. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2010 doi: 10.1002/term.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Puolakkainen PA, Reed MJ, Gombotz WR, et al. Acceleration of wound healing in aged rats by topical application of transforming growth factor-beta(1) Wound Repair Regen. 1995;3(3):330–339. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475X.1995.t01-1-30314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rivard A, Fabre JE, Silver M, et al. Age-dependent impairment of angiogenesis. Circulation. 1999;99(1):111–120. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sadoun E, Reed MJ. Impaired angiogenesis in aging is associated with alterations in vessel density, matrix composition, inflammatory response, and growth factor expression. J Histochem Cytochem. 2003;51(9):1119–1130. doi: 10.1177/002215540305100902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pacilli A, Faggioli G, Stella A, et al. An update on therapeutic angiogenesis for peripheral vascular disease. Ann Vasc Surg. 2010;24(2):258–268. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gerber HP, Senter PD, Grewal IS. Antibody drug-conjugates targeting the tumor vasculature: current and future developments. MAbs. 2009;1(3):247–253. doi: 10.4161/mabs.1.3.8515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Temming K, Schiffelers RM, Molema G, et al. RGD-based strategies for selective delivery of therapeutics and imaging agents to the tumour vasculature. Drug Resist Updat. 2005;8(6):381–402. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Murphy EA, Majeti BK, Barnes LA, et al. Nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery to tumor vasculature suppresses metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(27):9343–9348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803728105. • This article describes a method of formulating doxorubicin-loaded nanoparticles targeted to tumor vasculature via an integrin-targeting peptide, which yielded increased targeting to the site, a strong antiangiogenic effect, and, importantly, 15 times less toxicity.

- 56.Mitra A, Mulholland J, Nan A, et al. Targeting tumor angiogenic vasculature using polymer-RGD conjugates. J Control Release. 2005;102(1):191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Green MR, Manikhas GM, Orlov S, et al. Abraxane®, a novel Cremophor®-free, albumin-bound particle form of paclitaxel for the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(8):1263–1268. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brem H, Mahaley MS, Vick NA, et al. Interstitial chemotherapy with drug polymer implants for the treatment of recurrent gliomas. J Neurosurg. 1991;74(3):441–446. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.74.3.0441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Perry J, Chambers A, Spithoff K, et al. Gliadel wafers in the treatment of malignant glioma: a systematic review. Curr Oncol. 2007;14(5):189–194. doi: 10.3747/co.2007.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Benoit DSW, Nuttelman CR, Collins SD, et al. Synthesis and characterization of a fluvastatin-releasing hydrogel delivery system to modulate hMSC differentiation and function for bone regeneration. Biomaterials. 2006;27(36):6102–6110. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tabata Y, Miyao M, Ozeki M, et al. Controlled release of vascular endothelial growth factor by use of collagen hydrogels. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2000;11:915–930. doi: 10.1163/156856200744101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lutolf MP, Lauer-Fields JL, Schmoekel HG, et al. Synthetic matrix metalloproteinase-sensitive hydrogels for the conduction of tissue regeneration: engineering cell-invasion characteristics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(9):5413–5418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0737381100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yasuhiko T. Current status of regenerative medical therapy based on drug delivery technology. Reprod Biomed Online. 2008;16(1):70–80. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60558-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hoare TR, Kohane DS. Hydrogels in drug delivery: progress and challenges. Polymer. 2008;49(8):1993–2007. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Williams DF. Tissue-biomaterial interactions. J Mater Sci. 1987;22(10):3421–3445. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Anderson JM, Rodriguez A, Chang DT. Foreign body reaction to biomaterials. Semin Immunol. 2008;20(2):86–100. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Willerth SM, Sakiyama-Elbert SE. Approaches to neural tissue engineering using scaffolds for drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2007;59(4–5):325–338. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Saltzman WM, Olbricht WL. Building drug delivery into tissue engineering. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1(3):177–186. doi: 10.1038/nrd744. • Although we do not delve into the technical challenges faced by tissue engineers because of ischemia, this review discusses these problems in more detail and provides examples of how drug delivery can be incorporated into several systems for improved neovasculature or tissue growth.

- 69.Schakenraad JM, Hardonk MJ, Feijen J, et al. Enzymatic activity toward poly(L-lactic acid) implants. J Biomed Mater Res. 1990;24(5):529–545. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820240502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Spenlehauer G, Vert M, Benoit JP, et al. In vitro and in vivo degradation of poly(D,L lactide/glycolide) type microspheres made by solvent evaporation method. Biomaterials. 1989;10(8):557–563. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(89)90063-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Anderson JM, Shive MS. Biodegradation and biocompatibility of PLA and PLGA microspheres. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1997;28(1):5–24. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(97)00048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Panyam J, Labhasetwar V. Biodegradable nanoparticles for drug and gene delivery to cells and tissue. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2003;55(3):329–347. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00228-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Faraji AH, Wipf P. Nanoparticles in cellular drug delivery. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17(8):2950–2962. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Freiberg S, Zhu XX. Polymer microspheres for controlled drug release. Int J Pharm. 2004;282(1–2):1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Varde NK, Pack DW. Microspheres for controlled release drug delivery. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2004;4(1):35–51. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Patil SD, Papadmitrakopoulos F, Burgess DJ. Concurrent delivery of dexamethasone and VEGF for localized inflammation control and angiogenesis. J Control Release. 2007;117(1):68–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Visscher GE, Pearson JE, Fong JW, et al. Effect of particle size on the in vitro and in vivo degradation rates of poly(DL-lactide-co-glycolide) microcapsules. J Biomed Mater Res. 1988;22(8):733–746. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820220806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Grizzi I, Garreau H, Li S, et al. Hydrolytic degradation of devices based on poly(-lactic acid) size-dependence. Biomaterials. 1995;16(4):305–311. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(95)93258-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bertram JP, Jay SM, Hynes SR, et al. Functionalized poly(lactic-coglycolic acid) enhances drug delivery and provides chemical moieties for surface engineering while preserving biocompatibility. Acta Biomater. 2009;5(8):2860–2871. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Blanco MD, Alonso MJ. Development and characterization of protein-loaded poly(lactide-co-glycolide) nanospheres. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 1997;43(3):287–294. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Qi H, Hu P, Xu J, et al. Encapsulation of drug reservoirs in fibers by emulsion electrospinning: morphology characterization and preliminary release assessment. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7(8):2327–2330. doi: 10.1021/bm060264z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Holland TA, Tabata Y, Mikos AG. In vitro release of transforming growth factor-[beta]1 from gelatin microparticles encapsulated in biodegradable, injectable oligo(poly(ethylene glycol) fumarate) hydrogels. J Control Release. 2003;91(3):299–313. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00258-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tzeng SY, Lavik EB. Photopolymerizable nanoarray hydrogels deliver CNTF and promote differentiation of neural stem cells. Soft Matter. 2010;6(10):2208–2215. [Google Scholar]