Abstract

Cigarette companies increasingly promote novel smokeless tobacco products to smokers, encouraging them to use smokeless tobacco in smoke-free environments. New messages may counteract this promotion. We developed 12 initial anti-smokeless message ideas and tested them in eight online focus groups with 75 US smokers. Those smokers who never tried smokeless tobacco were unaware of health risks of novel smokeless tobacco products, perceived scary messages as effective and acknowledged the addictive nature of nicotine. Smokers who had tried smokeless tobacco shared their personal (mainly negative) experiences with smokeless tobacco, were aware of health risks of novel smokeless tobacco products, but denied personal addiction, and misinterpreted or disregarded more threatening messages. Portraying women as smokeless tobacco users was perceived as unbelievable, and emphasizing the lack of appeal of novel smokeless tobacco products was perceived as encouraging continued smoking. Future ads should educate smokers about risks of novel smokeless tobacco products, but past users and never users may require different message strategies.

Introduction

While most US tobacco users smoke cigarettes, popularity of smokeless tobacco products is rising, due in part to the promotion of various novel smokeless tobacco products [1, 2]. In 2006, R.J. Reynolds and Philip Morris cigarette companies acquired smokeless tobacco companies and introduced cigarette-branded smokeless tobacco products labeled ‘snus’ into the US market [3]. Snus is a finely ground tobacco packaged in small porous pouches. Snus marketing suggested use in situations when smoking was restricted and highlighted advantages over cigarettes or traditional chewing tobacco (e.g. snus not requiring spitting) [4]. Since 2009, additional novel smokeless tobacco products have been tested, such as R.J. Reynolds’s Camel branded ‘strips’, ‘orbs’ and ‘sticks’ that some claim look like candy and may appeal to youth [5, 6]. In 2012, Altria Group Inc. (parent company of Philip Morris) introduced chewable, spit-free, Verve ‘discs’, which are made from a polymer and non-tobacco cellulose fibers with mint flavoring and nicotine, and contain no tobacco [7]. In 2012, R.J. Reynolds introduced tobacco-derived smokeless pouches and pellets branded as Viceroy [8] and lozenges branded as Velo Rounds [9, 10]. Since 1998, tobacco industry expenditures for smokeless tobacco marketing have increased by 277% [1].

Some argue that smokeless tobacco should be promoted to encourage smokers to switch to a safer product [11]. However, many marketing messages encourage temporary use in smoke-free environments, a behavior that may promote dual use of multiple tobacco products rather than complete substitution of smokeless tobacco for cigarettes, and may prolong addiction or compromise attempts to quit tobacco [2, 12, 13]. Dual use of smokeless tobacco and cigarettes is not consistently associated with cessation [13–15], is linked to chronic inflammatory disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease and ulcerative colitis [16, 17], and carries greater cardiovascular risk than use of a single tobacco product [18]. In addition, smokeless tobacco use is associated with numerous health problems, including cardiovascular disease [19, 20], heart attack [18, 21, 22], stroke [21], leukoplakia [23], mouth cancer [24], throat cancer [25], stomach cancer [26], pancreatic cancer [27] and stillbirth [28, 29]. Prolonged use of snus is associated with head and neck cancers and type 2 diabetes [30, 31]. Although Swedish snus has lower levels of tobacco-specific nitrosamines than most smokeless tobacco sold in the United States, the product called ‘snus’ in the United States is manufactured and sold differently than Swedish snus [32–34], and there are virtually no studies on the health effects of US snus. New candy-like smokeless products may normalize nicotine use and may serve as a gateway to smoking and nicotine addiction [35], particularly because they allow rapid nicotine absorption [36] and they can be used discreetly by youth at home or in school without adults’ knowledge [37].

To counter the new aggressive tobacco industry marketing, new counter-advertising messages are needed to discourage uptake of smokeless products by smokers, particularly use of the product in addition to cigarettes. However, studies on development of such messages and evaluation of their impact have been sparse, and in-depth qualitative research on public perceptions of novel smokeless tobacco is limited [37–40]. Some studies found smokers are aware of products such as snus and dissolvables, perceive them positively, believe they are less harmful than cigarettes, and are willing to experiment with them [38, 40, 41]. Other studies also suggest high awareness and a substantial initial interest in the novel products among young adults in the Midwest [38, 39].

Additional research on effective anti-smokeless messages is required, and as a first step toward this goal, we developed some counter-marketing message ideas and tested them in online focus groups of smokers recruited from across the United States. Our experience over the past 3 years conducting studies of smokeless tobacco marketing strategies using previously secret tobacco industry documents [3] and our previous research on smokers’ perceptions of novel smokeless tobacco products [40] contributed to the development of these counter-marketing ideas. This article builds on past research by examining how smokers react to various counter-marketing message concepts, and how these reactions are shaped by their previous experience with smokeless tobacco.

Methods

Message development

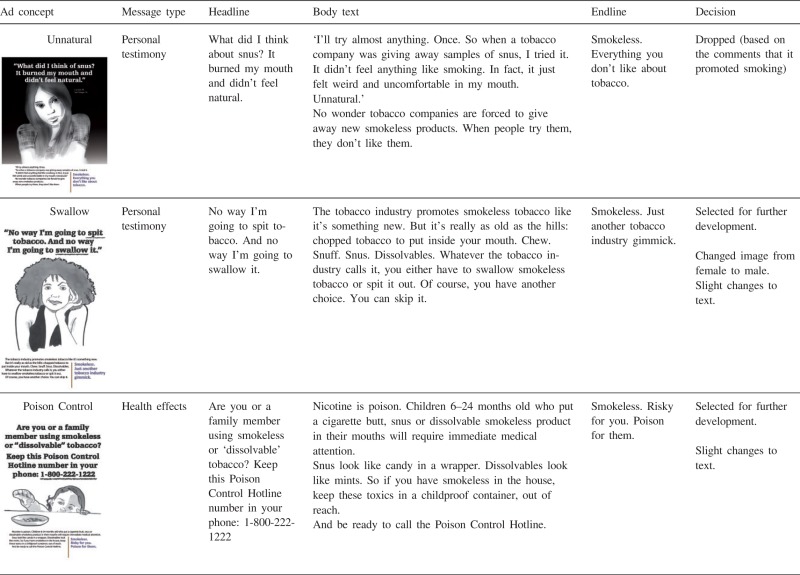

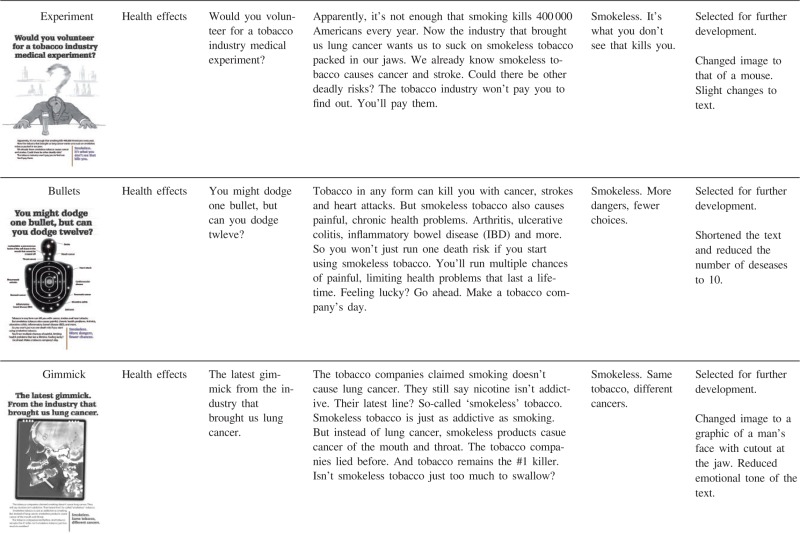

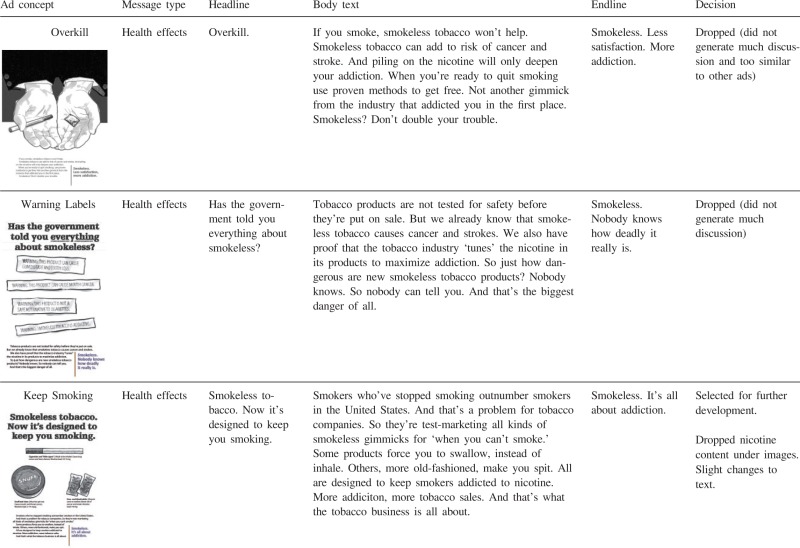

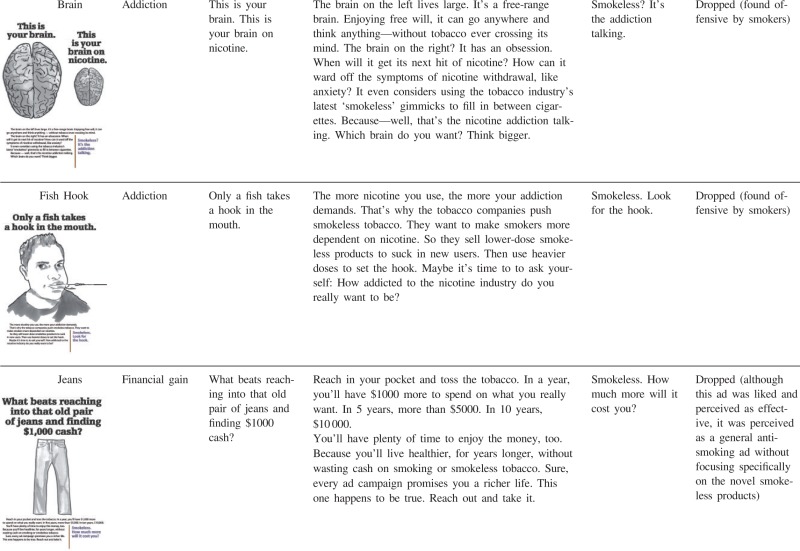

The ideas for potential counter-marketing messages were developed as team members from a variety of disciplines (medicine, social marketing, public health, anthropology) iteratively reviewed and discussed past and current smokeless tobacco marketing messages along with insights from focus group data collected from smokers in California in 2010 [40], working in collaboration with social marketing agency that developed the initial concepts. As a result, 12 rough message concepts were created (see Table AI). The messages differed in their informational content (e.g. negative health effects of using snus versus financial benefits of quitting smokeless tobacco) and execution style (e.g. personal testimony versus graphic image versus scientific evidence). In some cases, the messages were deliberately designed to be controversial or provocative to allow us to assess the types of discussion that followed exposure to different messages. Four of the 12 ads specifically focused on novel smokeless tobacco products (snus and dissolvables), while 7 referred to smokeless tobacco in general. One ad (‘Keep smoking’) compared and contrasted different tobacco products. The 12 messages can be classified post hoc into four categories: personal testimony, health effects, addiction and financial gain (Table AI). Personal testimony ads featured specific people who shared personal experiences with smokeless tobacco. Health effects ads depicted negative health consequences of smokeless tobacco. Addiction ads demonstrated that smokeless tobacco exacerbates nicotine addiction. Although addiction is a type of a negative health effect, and it was mentioned in many of the messages classified as ‘health effects’, it was the central theme on only two ads. Finally, one ad emphasized cost savings as a benefit of not using smokeless tobacco.

Data collection

The institutional review board at the University of California, San Francisco approved this study. We conducted eight online focus groups in July 2011. Participants were 75 current and recent former smokers recruited from a nationally representative research panel maintained by Knowledge Networks, a research company that recruits participants through probability-based sampling using address-based methods. The company rewards participants with incentive points redeemable for cash or with hardware and free access to the Internet. All participants were over 18 years, smoked over 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and either currently smoked or quit no more than 2 years ago. Former smokers who had quit more than 2 years prior to the study were excluded because many novel smokeless tobacco products were introduced only recently, and because relapse rates for former smokers abstaining longer than 2 years are low [42]. We aimed for variation in age, gender, education, geography and income. Knowledge Networks fielded participation requests to 201 qualified participants, of which 75 took part in the study.

Our sample participated in focus groups from their home computers using web conferencing software. Participants read a live transcript and typed their comments into a chat box. Online focus groups discussions differ from traditional face-to-face focus groups in several ways. Online chat is characterized by less structured turn taking with comments sometimes appearing out of sequence due to participants’ different typing speed. However, online focus groups offer some advantages over traditional face-to-face focus groups because each contribution is prefixed with the participant’s name, allowing us to trace every comment to each individual, and online focus groups may facilitate participation by being more convenient and by lowering inhibitions because participants are not visible to each other [43]. Online focus groups are an inexpensive way to bring together a demographically and geographically diverse sample of participants that is rarely possible in a traditional face-to-face setting [44], and since all ‘voices’ are rendered in the same format, there may be less interference by differences in accent, age, education, gender, class, race or rhetorical skill. A member of our research team with expertise in qualitative research moderated all focus groups. After the introduction and warm up, the moderator presented different message concepts (Table AI) and elicited responses from the group. Participants viewed advertisement concepts on their computer screens and typed responses in the chat window. Messages were rotated, and each group viewed at least four different message concepts that were randomly selected; additional concepts were shown based on themes in the group discussion. Probes were used to deepen the discussion, to illuminate specific messages in the ads and to encourage participants to elaborate on various topics, including their perceptions of dual use of smokeless products and cigarettes, addiction, tobacco industry, health effects of nicotine and whether the ad concepts altered participants’ ideas about tobacco products.

Participants’ demographic information (gender, age, education, marital status, household characteristics, income, location) was provided, and the only significant difference between participants and non-participants was education: 9.3% of participants had less than high school education, while 23.8% of non-participants had this level of education (χ2 = 14.849, P = 0.002). There were no significant differences for participants in gender, age, race, marital status, employment status or geographic region. All participants completed an individual questionnaire about their tobacco use (both cigarettes and smokeless tobacco) prior to participating in the focus group. In addition, during the online chat participants were asked to indicate whether they had ever tried smokeless (chewing) tobacco, snus or dissolvable tobacco products. Participants who responded affirmatively to having used any smokeless tobacco product in the past either in the questionnaire or during focus groups were categorized as past smokeless users.

Data analysis

All comments were automatically recorded and available for analysis, and in addition to the transcripts, screen capture videos recorded the focus groups in real time allowing review of the message concepts and flow of the discussion. Research team members directly observed all focus groups and engaged in analytical debriefing discussions immediately following each group. Two researchers developed codes by independently reading focus group transcripts, and devising codes that emerged from the data. The research team then met as a group to discuss codes and create a master list of codes and definitions. After that, two members of the team coded the transcripts. Coding schemas were revised iteratively in consultation with all team members to reconcile the codes and achieve consensus. To further generate organizational schemes, conceptualize, and sort the data, researchers wrote memos, which focused the emerging themes and concepts, into a discussion that emphasizes the outcomes of the analysis. During analysis, team members met regularly to discuss the emerging data and the memos generated by this process.

Thematic codes included beliefs about risks and benefits of smokeless tobacco, knowledge of and experience with novel smokeless tobacco products, negative and positive reactions to the ads, emotional responses to the ads, cognitive responses to ads (e.g. misinterpretation) and perceptions of the ads (believability, novelty, etc.).

Results

The demographic characteristics and tobacco use history of participants are presented in Table I. Forty-one percent of participants had used smokeless tobacco in the past, and six people (8%) had used smokeless tobacco in the past 30 days. Responses to counter-marketing ads varied between past users and non-users of smokeless tobacco and across different types of ads (personal testimony, health effects, addiction and financial gain ads).

Table I.

Participant demographic characteristics and tobacco use (N = 75)

| Characteristic | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| 18–29 | 16 (21) |

| 30–44 | 21 (28) |

| 45–59 | 23 (31) |

| 60+ | 15 (20) |

| Female | 31 (41) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 55 (73) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 9 (12) |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 1 (1.3) |

| Hispanic | 9 (12) |

| Non-Hispanic multiple race | 1 (1.3) |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 7 (9) |

| High school | 24 (32) |

| Some college | 26 (35) |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 18 (24) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 33 (44) |

| Widowed | 3 (4) |

| Divorced | 10 (13) |

| Never married | 18 (24) |

| Living with partner | 11 (15) |

| Rural | 7 (9) |

| Region | |

| Northeast | 15 (20) |

| Midwest | 18 (24) |

| South | 24 (32) |

| West | 18 (24) |

| Annual income (thousand USD) | |

| <15 | 11 (15) |

| 15–24.9 | 5 (7) |

| 25–39.9 | 19 (25) |

| 40–59.9 | 8 (11) |

| >60 | 32 (42) |

| Cigarette use | |

| Current daily smoker | 54 (72) |

| Current non-daily smoker | 15 (20) |

| Former smoker | 6 (8) |

| Past smokeless tobacco user | 31 (41) |

| Other tobacco product use (past 30 days) | |

| Chewing tobacco | 3 (4) |

| Snus | 4 (5) |

Participants used different terms to refer to smokeless tobacco, such as ‘tobacco’, ‘chew’, ‘wad of chew’, ‘snuff’, ‘smokeless’ and brand names like ‘Skoal’. When discussing the ads that specifically referred to novel products, i.e. snus and dissolvables, participants used these terms or the words ‘new product’ to describe smokeless tobacco, but also talked about ‘smokeless tobacco’ in general. When talking about ads that did not differentiate between different types of products, participants rarely explicitly distinguished between novel and other smokeless tobacco products.

Differences between non-users and experienced users of smokeless tobacco across all ads

Across responses to various anti-smokeless ads, we compared past users and non-users of smokeless tobacco products on attitudes and knowledge of the novel smokeless products. Smokers who had not tried smokeless tobacco products had little knowledge of the novel tobacco products and often failed to understand what is depicted in the messages. They said, for example, ‘it does nothing for me I can not understand the graphics’ (male, 61, GA) and ‘you lost me’ (female, 69, OH). In contrast, past users of smokeless tobacco had little difficulty recognizing the products, e.g. ‘Snus: A packet that tucks between your lip and gum to release nicotine’ (male, 25, SD).

Expressing a positive or a negative attitude toward new smokeless tobacco products did not differ by whether the person had tried smokeless tobacco in the past. Many past users had negative personal experiences with smokeless tobacco, and almost all of those participants had nothing positive to say about smokeless tobacco. Only one person expressed a positive attitude toward smokeless tobacco, ‘Why would a smoker even consider trying smokeless? – cheaper and no smell’, (female, 22, TX) after having a negative personal experience with smokeless tobacco, ‘It was different. I hated the taste it left in my mouth though’. Yet some smokers (both past users and non-users) expressed positive attitudes toward smokeless tobacco, such as saying that snus was convenient and clean, while simultaneously stating that smokeless tobacco is hazardous to health.

Personal testimony ads

Two ads (‘Unnatural’ and ‘Swallow’, Table AI) used personal testimony. In both ads, a woman shared her personal opinion or experience with snus, stating that she did not find this product appealing. Non-users agreed that lack of appeal is the main reason not to buy snus (see Table II for illustrative quotes). Past smokeless users shared their own negative personal experiences, but they discounted the personal testimony ads as ineffective; they recommended using fear appeals instead.

Table II.

Differences between non-users and past users of smokeless tobacco across the different types of ads and additional critiques of the ads

| Type of ad | Non-users | Past users | Caution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personal testimony |

|

|

|

| Health threat |

|

|

|

| Addiction |

|

|

|

Both past users and non-users pointed out that accentuating the negative qualities of novel smokeless tobacco products could unintentionally encourage continued smoking and result in message ‘backfiring’. Finally, participants mentioned that female testimonials were less believable because smokeless tobacco use was viewed as a male behavior.

Health effects ads

Most of the messages in one way or another addressed negative health consequences of smokeless tobacco (Table AI). The idea that smokeless tobacco is harmful was new for some non-users, while past smokeless tobacco users were generally aware of thehazards of smokeless tobacco products. A very small but vocal number of experienced users wereadamant about harm reduction potential of smokeless tobacco, ‘That one's a damned lie. Smokeless may well not be good for anyone, but does it cause COPD? Check the death rates, people, before you start that kind of bull butter’ (male, 58, AR).

There were some differences between past users and non-users of smokeless tobacco in fear responses to health effects ads. Non-users readily acknowledged fear or anxiety responses. For example, the ‘Poison Control’ ad portrayed a small child reaching for pellets of dissolvable tobacco with the reminder to keep the Poison Control phone number handy if using the product. Several non-users said that this idea scared them. The ‘Bullets’ ad that showed a shooting target with marks for different diseases linked to smokeless tobacco made non-users ‘even more afraid’ (male, 53, OH). Furthermore, non-users endorsed health threats as an effective strategy and some suggested making the ads even scarier. Fear appeal messages seemed to backfire for many past smokeless tobacco users. Past users of smokeless tobacco criticized health effects messages as not effective or minimized the threats presented in the health effects messages. Some said that ads such as ‘Poison Control’ were ‘overboard’. In response to the ‘Bullets’ ad, one past user said, ‘sounds like side affects for just about anything you do … known people who never smoked or chewed and had some of this happen to them’ (male, 36, AZ). Commenting on the ‘Overkill’ ad, which highlighted dangers of dual use, another past smokeless user stated, ‘If you ask me it all seems like just to put fear into everyone. we all take chances everyday with all tabacco products’ (female, 31, TX). Finally, past users, compared to non-users, misinterpreted the ‘Poison Control’ ad to a greater extent; past users tended to distance themselves from the situation and misinterpreted the message by perceiving the message to be cautioning parents against general childhood risks.

Nicotine content and addiction

The ‘Keep Smoking’ ad depicted a cigarette, a can of moist snuff, and snus pouches delineating their nicotine content and health effects. Comparing nicotine amounts in novel smokeless products and cigarettes seemed to potentially trigger interest in low-nicotine smokeless products.

Addiction was the main focus of two ads, and in both cases the addiction was portrayed metaphorically. The ‘Brain’ ad used a metaphor contrasting a brain on nicotine (very small) with a normal-size addiction-free brain. Some non-users perceived this ad as credible and understood the metaphor: ‘its your frame of thinking that impairs you’ (male, 31, FL). However, many non-users and past users alike seemed to take this ad literally (and personally): ‘smokers aren't as smart as non-smokers. Also pretty lame ad since I wouldn't believe the actual brain size is smaller in a smoker’ (male, 36, IL).

The second ad that focused on addiction portrayed a young male with a hook in his mouth, conveying the idea that tobacco industry hooks people on nicotine. The overwhelming response to this ad was negative from both non-users and experienced users of smokeless tobacco, for example, ‘Dumb, dumb, dumb’ (male, 49, AZ, past user) and ‘Useless’ (female, 64, MO, non-user). However, while non-users generally agreed that ‘nicotine is easy to get hooked on’ (female, 64, DC), many past users denied that they were addicted to tobacco.

Financial gain ad

Instead of portraying negative consequences of smokeless tobacco use, the ‘Jeans’ ad focused on the benefit of saving money by quitting smokeless tobacco. Non-users and past users of smokeless tobacco both agreed that it showed a ‘Good reason for quitting, but the smokeless part gets lost’ (male, 57, HI). Both smokeless tobacco users and non-users said that for them personally ‘cost is VERY important’ (male, 38, CA) and ‘number 1! Thats why I quit’ (female, 48, MN). At the same time, many discounted the importance of cost for other people: ‘people who use tobacco will continue no matter the cost …’ (female, 49, TX) and ‘any addiction a person has will make them find the money’ (male, 52, FL).

Discussion

These focus group discussions revealed that smokers who used or tried smokeless tobacco in the past reacted differently to anti-smokeless tobacco ads than those who have not tried smokeless tobacco before. We found that never users were often unaware of novel smokeless tobacco products or their health effects, and expressed some positive views of the new products. Past users’ own experience with smokeless tobacco was predominantly negative. This differs from an analysis of posts on smokeless tobacco message boards [45], but similar to other focus groups of smokers [40]. Similar to other studies [38, 46], smokers in our focus groups held a range of beliefs about harmfulness of novel smokeless tobacco products when compared to cigarettes. A quantitative study [47] found that a substantial number of smokers have tried smokeless tobacco in the past, and these smokers are at higher risk for future smokeless tobacco use. These results suggest that when developing messages discouraging dual tobacco use for smokers, one might consider different approaches for past users and never users of smokeless tobacco.

Furthermore, never users and past users of smokeless tobacco had different reactions to ads with different themes. Some participants’ comments indicated that messages emphasizing snus’s lack of appeal may reinforce smoking when viewed by smokers. Past negative experiences with novel smokeless tobacco products referenced in counter-marketing advertisements might be perceived as a pro-smoking message.

Although novel smokeless tobacco products are being promoted more aggressively to women, counter-marketing messages should use caution when depicting women in ads using smokeless tobacco. Our participants generally regarded use of both novel and typical smokeless tobacco as a male activity and found anti-smokeless messages featuring women less believable. This finding differs from the analysis of Camel snus online discussion boards [45]. Because only two of the 12 ad concepts featured women in this study, it may be premature to discourage the appearance of women in any anti-smokeless messages, particularly because in this case both women were portrayed as potential smokeless tobacco users, and future research might explore as an alternative portraying women’s disapproval of smokeless tobacco use among men.

Past users frequently recommended using scary images of negative health consequences of smokeless tobacco use, but scary images were not uniformly perceived as effective. Graphic images of severe health consequences of tobacco are commonly used in anti-tobacco advertising and were found to be effective in health campaigns [48]. Many existing anti-smokeless tobacco messages include graphic portrayals of jaw cancer. The message concepts in this study were designed to portray the health risks of smokeless tobacco without a frightening graphic image. Nonetheless, the health effect ads tended to evoke fear from some participants, and generated extensive discussions among those who had not used smokeless tobacco, because many of non-users did not realize that smokeless tobacco is harmful. However, even these less graphic messages tended to arouse distrust in the counter-marketing message, misinterpretation of the ad or minimization of the message ideas among past smokeless tobacco users.

The finding that past users were more defensive in response to the graphic health risk messages compared to non-users fits well with the literature on fear appeals. The extended parallel process model [49] posits that when a threat is great, but an effective response is non-existent or hard to carry out, people resort to maladaptive strategies to deal with fear. Instead of carrying out protective actions (such as quitting smoking or starting to use sunscreen) they ascribe manipulative intentions to the message creators, minimize the threat or derogate the issue. This is consistent with our findings among some of the past smokeless tobacco users in our study: they minimized the health dangers of smokeless tobacco, claimed that they were not scared by the message, criticized the message or misinterpreted the message as a parental warning about common household dangers. Therefore, when developing messages targeting past users of smokeless tobacco one might use caution with fear appeals, deemphasizing the threat of novel tobacco products or making this threat less personal.

Addiction ads elicited the most negative response from participants. Although some non-users understood the metaphor and explicitly discussed nicotine addiction, others seemed to interpret the metaphorical portrayals of addiction more literally and some respondents denied personal addiction to nicotine. Although prior research on smoking has indicated that smokers do not recognize the addiction and this is an area in need of intervention [50–52], the images in this study appeared to elicit responses that turned participants away from the intended message. Different messages might be needed to convey the idea of addiction.

Based on these responses, we modified the preliminary anti-smokeless message concepts. First, we dropped messages portraying novel smokeless tobacco products as unappealing, as they might encourage continued smoking. Second, we changed the testimonial image from female to male. Third, we removed comparisons of nicotine content between various smokeless products, but retained the similar negative health effects (‘causes cancer and heart disease’) for each product. Fourth, because more graphic frightening images tended to elicit reactance from past users of smokeless tobacco, we toned down the health messages from explicit portrayal of disease to more metaphorical, and dropped the addiction ads. Finally, although the positive orientation of the ‘Jeans’ ad was generally liked, the ad was perceived as a general anti-smoking ad not connected to novel smokeless products, so this ad was dropped from further development.

Despite our demographically and geographically diverse sample of smokers, findings from our study cannot be generalized to all current and recent former smokers. The focus groups were conducted in an online chat format, which might have presented difficulty for some participants, as their input might have been limited by the internet connection speed and by their typing speed. In addition, lack of non-verbal cues (body language, tone of voice, etc.) reduced richness of the data. On the other hand, the online format afforded convenience, and because participants did not see each other and remained anonymous they might have been more frank and less inhibited in their answers. It is unclear whether these elements increase or decrease the clarity of the discussion; the effects of this novel format of focus groups remain to be further explored in future studies.

Another potential limitation of our study is that participants’ perceptions of message effectiveness may not necessarily relate to actual effectiveness in discouraging uptake of smokeless products. However, determining perceived effectiveness is an important step in designing effective messages, and predicts changes in attitudes and other indicators related to targeted health outcomes [53]. This study was not designed from the outset to compare past users to never-users of smokeless tobacco products; our focus groups contained both types of respondents. However, because chat participants can be reliably identified and matched to their tobacco use status on an individual level, we were able to compare and contrast past users to never users in this study, and this comparison emerged from patterns we saw in the data.

Future studies might consider stratifying participants into groups based on their past experience with smokeless tobacco. It is possible that the conversations among more homogeneous groups with respect to current and former cigarette and smokeless tobacco use might have yielded different data in some respects than groups with mixed experience.

Nonetheless, we were able to identify insights into novel smokeless tobacco products that are relevant for messages discouraging dual tobacco use. Divergent reactions between past smokeless users and non-users to these counter-marketing messages suggest that tailoring anti-smokeless intervention messages based on prior use of smokeless products may prove useful. Larger studies using a mixed-methods approach are needed to show whether the qualitative, contextual findings from this study are applicable to other smokers.

To our knowledge, this was the first qualitative study in which responses to messages discouraging use of novel smokeless tobacco products were compared between past smokeless tobacco users and smokeless tobacco novices. Messages aimed at discouraging the uptake of smokeless tobacco products among smokers who have not tried smokeless tobacco might emphasize education about health hazards of those products. In contrast, those developing messages targeting smokers who are prior users of smokeless tobacco might consider carefully the responses to fear appeals, and these messages should be evaluated for negative reactance or the unintended consequence of reinforcing smoking rather than encouraging cessation of all tobacco products.

Acknowledgements

Counter advertisements were developed by Jono Polansky, OnBeyond LLC.

Funding

National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (grant number R01-CA141661). The article contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Appendix

Table AI.

Description of the concept ideas for counter-marketing messages used in the focus groups

|

|

|

|

References

- 1.United States Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mejia AB, Ling PM, Glantz SA. Quantifying the effects of promoting smokeless tobacco as a harm reduction strategy in the USA. Tob Control. 2010;19:297–305. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.031427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mejia AB, Ling PM. Tobacco industry consumer research on smokeless tobacco users and product development. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:78–87. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Trinkets & Trash Artifacts of the Tobacco Epidemic. Marketing Smokeless Tobacco: Moist Snuff, Snus, Dissolvables. The Online Surveillance System and Archive of Tobacco Products and Tobacco Industry Marketing Materials. Available at http://www.trinketsandtrash.org. Accessed: 18 December 2013.

- 5.Carpenter CM, Wayne GF, Pauly JL, et al. New cigarette brands with flavors that appeal to youth: tobacco marketing strategies. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24:1601–10. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.6.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klein SM, Giovino GA, Barker DC, et al. Use of flavored cigarettes among older adolescent and adult smokers: United States, 2004–2005. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:1209–14. doi: 10.1080/14622200802163159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blackwell JR. Richmond Times-Dispatch. Richmond, VA: 2012. Altria to test market new nicotine product in Virginia. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Craver R. Winston-Salem Journal. Winston-Salem, NC: 2012. Reynolds developing new smokeless products. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Trademarkia.com. Velo Rounds, 2012. Available at: http://www.trademarkia.com/velo-rounds-85737962.html. Accessed: 18 December 2013.

- 10. Smoking Cessation Leadership Center. Emerging Tobacco Products, 2012. Available at: http://smokingcessationleadership.ucsf.edu/webinar_28_nov_8_2012.pdf. Accessed: 18 December 2013.

- 11.Britton J. Should doctors advocate snus and other nicotine replacements? Yes. BMJ. 2008;336:358. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39479.427477.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomar SL, Alpert HR, Connolly GN. Patterns of dual use of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco among US males: findings from national surveys. Tob Control. 2010;19:104–9. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.031070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wetter DW, McClure JB, de Moor C, et al. Concomitant use of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco: prevalence, correlates, and predictors of tobacco cessation. Prev Med. 2002;34:638–48. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomar SL. Epidemiologic perspectives on smokeless tobacco marketing and population harm. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:S387–97. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klesges RC, Sherrill-Mittleman D, Ebbert JO, et al. Tobacco use harm reduction, elimination, and escalation in a large military cohort. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:2487–92. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.175091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Persson PG, Hellers G, Ahlbom A. Use of oral moist snuff and inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Epidemiol. 1993;22:1101–3. doi: 10.1093/ije/22.6.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlens C, Hergens M-P, Grunewald J, et al. Smoking, use of moist snuff, and risk of chronic inflammatory diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:1217–22. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200909-1338OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teo KK, Ounpuu S, Hawken S, et al. Tobacco use and risk of myocardial infarction in 52 countries in the INTERHEART study: a case-control study. The Lancet. 2006;368:647–58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69249-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bolinder G, Alfredsson L, Englund A, et al. Smokeless tobacco use and increased cardiovascular mortality among Swedish construction workers. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:399–404. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.3.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yatsuya H, Folsom AR. Risk of incident cardiovascular disease among users of smokeless tobacco in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:600–5. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boffetta P, Straif K. Use of smokeless tobacco and risk of myocardial infarction and stroke: systematic review with meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b3060. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hergens MP, Alfredsson L, Bolinder G, et al. Long term use of Swedish moist snuff and the risk of myocardial infarction amongst men. J Intern Med. 2007;262:351–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Smokeless Tobacco and Some Tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks (SCENIHR) Health Effects of Smokeless Tobacco Products. Brussels: Health and Consumer Protection Directorate-General, European Commission; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Institute of Medicine, Stratton K, Shetty P et al. Clearing the Smoke: Assessing the Science Base for Tobacco Harm Reduction. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2001. [PubMed]

- 26.Zendehdel K, Nyrén O, Luo J, et al. Risk of gastroesophageal cancer among smokers and users of Scandinavian moist snuff. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:1095–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boffetta P, Aagnes B, Weiderpass E, et al. Smokeless tobacco use and risk of cancer of the pancreas and other organs. Int J Cancer. 2005;114:992–5. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wikstrom AK, Cnattingius S, Stephansson O. Maternal use of Swedish snuff (snus) and risk of stillbirth. Epidemiology. 2010;21:772–8. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181f20d7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gupta PC, Subramoney S. Smokeless tobacco use and risk of stillbirth: a cohort study in Mumbai, India. Epidemiology. 2006;17:47–51. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000190545.19168.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou J, Michaud DS, Langevin SM, et al. Smokeless tobacco and risk of head and neck cancer: evidence from a case-control study in New England. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:1911–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ostenson CG, Hilding A, Grill V, et al. High consumption of smokeless tobacco (“snus”) predicts increased risk of type 2 diabetes in a 10-year prospective study of middle-aged Swedish men. Scand J Public Health. 2012;40:730–7. doi: 10.1177/1403494812459814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Foulds J, Furberg H. Is low-nicotine Marlboro snus really snus? Harm Reduct J. 2008;5:9. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-5-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foulds J, Ramstrom L, Burke M, et al. Effect of smokeless tobacco (snus) on smoking and public health in Sweden. Tob Control. 2003;12:349–59. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.4.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramstrom LM, Foulds J. Role of snus in initiation and cessation of tobacco smoking in Sweden. Tob Control. 2006;15:210–4. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haddock CK, Weg MV, DeBon M, et al. Evidence that smokeless tobacco use is a gateway for smoking initiation in young adult males. Prev Med. 2001;32:262–7. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Connolly GN, Richter P, Aleguas A, Jr, et al. Unintentional child poisonings through ingestion of conventional and novel tobacco products. Pediatrics. 2010;125:896–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu ST, Nemeth JM, Klein EG, et al. Adolescent and adult perceptions of traditional and novel smokeless tobacco products and packaging in rural Ohio. Tob Control. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050470. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050470 (Epub ahead of print: October 9, 2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choi K, Fabian L, Mottey N, et al. Young adults' favorable perceptions of snus, dissolvable tobacco products, and electronic cigarettes: findings from a focus group study. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:2088–93. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choi K, Forster J. Awareness, perceptions and use of snus among young adults from the upper Midwest region of the USA. Tob Control. 2013;22:412–7. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bahreinifar S, Sheon NM, Ling PM. Is snus the same as dip? Smokers' perceptions of new smokeless tobacco advertising. Tob Control. 2013;22:84–90. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Biener L, Bogen K. Receptivity to Taboka and Camel Snus in a U.S. test market. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:1154–9. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wetter DW, Cofta-Gunn L, Fouladi RT, et al. Late relapse/sustained abstinence among former smokers: a longitudinal study. Prev Med. 2004;39:1156–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reid DJ, Reid FJM. An in-depth comparison of computer-mediated and conventional focus group discussions. Int J Market Res. 2005;47:131–62. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gaiser T. Online focus groups. In: Fielding NG, Lee RM, Blank G, editors. The Sage Handbook of Online Research Methods. London/Beverly Hills: Sage: 2008. pp. 290–306. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wackowski OA, Lewis MJ, Delnevo CD. Qualitative analysis of Camel Snus' website message board—users' product perceptions, insights and online interactions. Tob Control. 2011;20:e1. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.037911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Regan AK, Dube SR, Arrazola R. Smokeless and flavored tobacco products in the U.S.: 2009 Styles survey results. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Popova L, Ling PM. Alternative tobacco product use and smoking cessation: a national study. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:923–30. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Witte K, Allen M. A meta-analysis of fear appeals: implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27:591–615. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Witte K. Putting the fear back into fear appeals—the extended parallel process model. Commun Monogr. 1992;59:329–49. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weinstein ND, Slovic P, Gibson G. Accuracy and optimism in smokers' beliefs about quitting. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:375–80. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331320789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moffat BM, Johnson JL. Through the haze of cigarettes: teenage girls' stories about cigarette addiction. Qual Health Res. 2001;11:668–81. doi: 10.1177/104973201129119361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang C, Henley N, Donovan RJ. Exploring children's conceptions of smoking addiction. Health Educ Res. 2004;19:626–34. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dillard JP, Shen LJ, Vail RG. Does perceived message effectiveness cause persuasion or vice versa? 17 consistent answers. Human Commun Res. 2007;33:467–88. [Google Scholar]