Abstract

Platelets possess a dynamic functional repertoire that mediates hemostatic and inflammatory responses. Many of these functions are altered in older adults, promoting a pro-thrombotic and pro-inflammatory milieu and contributing to an increased risk of adverse clinical events. This review summarizes, drawing primarily from human studies, key aspects of aging-related changes in platelets. The relationship between altered platelet functions and thrombotic and inflammatory disorders in older adults is highlighted. Established and developing anti-platelet therapies for the treatment of thrombotic and inflammatory disorders are also discussed in light of these data.

Keywords: Platelet, Monocyte, Inflammation, Aging, Thrombosis

INTRODUCTION

Platelets are highly specialized effector cells that rapidly respond to sites of vascular injury or endothelial damage. While the hemostatic roles of platelets are well recognized, emerging data demonstrate that platelets possess diverse and dynamic functions that also mediate inflammatory and immune responses. These functions are germane to disease processes prevalent among older adults and likely influence susceptibility to thrombotic and inflammatory disorders, including vascular diseases and infectious syndromes, such as sepsis. This review will summarize key aspects of aging-related changes in platelets in the context of inflammatory and thrombotic pathologies in older adults. In light of these emerging data, established and developing anti-platelet therapies for two thrombotic and inflammatory disorders are also discussed.

Aging Increases the Risk of Thrombotic and Inflammatory Disorders

Thrombotic diseases (including ischemic heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, stroke, and venous thromboembolism (VTE)) are among the most common causes of death worldwide. Among thromboembolic disorders, coronary artery disease (CAD) is the leading cause of death for adults ≥75 years, with more than 80% of all CAD-related deaths occurring in this population1. Older age is also a risk factor for VTE, including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), and VTE-related mortality2. While estimates vary with differences in population characteristics and study methods, the incidence of VTE rises exponentially with aging. Estimates suggest that rates of VTE increase from approximately 1/10,000 in those aged < 40 years to 1/1,000 (~10-fold increase) in adults 75 years and older3. VTE may also be more closely linked to cardiovascular disease risk than previously appreciated, suggesting the possibility of shared risk factors and mechanisms4. Consequently, as the life expectancy increases and the proportion of adults≥65 years rises, the burden of thrombotic disease in the elderly will likely become even greater.

Older adults are also at increased risk for acute systemic inflammatory and infectious syndromes, such as sepsis, acute lung injury, and acute respiratory distress syndrome5. For example, in a large longitudinal study, patients ≥s65 years accounted for more than 60% of all sepsis cases and had a 13-fold higher relative risk of developing sepsis compared with younger patients5. In this dataset, case-fatality rates also increased linearly with age5. While comorbid conditions, frailty, and immunosenescence are implicated in this higher risk, exaggerated and/or dysregulated platelet functions are also likely contributors.

Platelet Functions Bridge Thrombosis and Inflammation

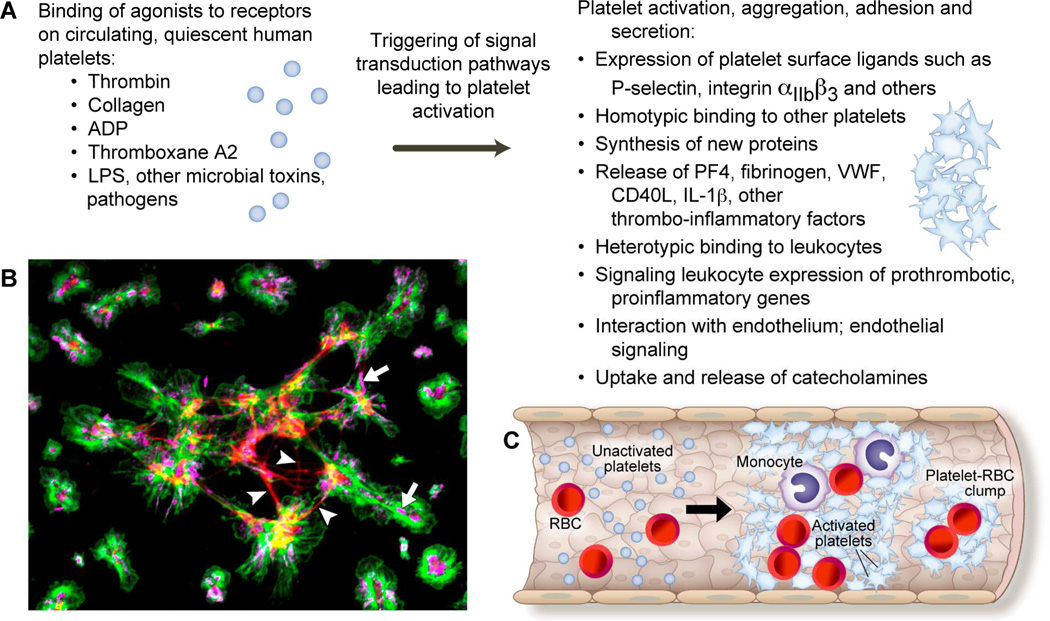

Platelets are anucleate blood cells specialized for rapid hemostatic reactions directed at sites of vascular injury6. The central role of platelets in thrombus initiation and propagation has long been recognized6. Nevertheless, initially thought to be merely circulating cell fragments with a relatively fixed repertoire of functional responses, more recent discoveries demonstrate that platelets are more versatile and dynamic effector cells that bridge thrombotic and inflammatory continua(Figure 1 and6).Platelet activation, which can be induced by thrombin, collagen, platelet-activating factor (PAF), microbial agents and/or toxins, and other agonists, leads to numerous platelet responses, including activation of integrin αIIbβ3 and upregulation of surface p-selectin, secretion of antimicrobial factors, chemokines, and cytokines, and enhanced aggregation with other cells6.

Figure 1.

Human platelets have a rich repertoire of dynamic functions that span thrombotic and inflammatory pathways. Panel A: In response to agonists such as thrombin, adenosine diphosphate (ADP), lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and other pathogens or toxins, platelets are activated. Platelet activation results in numerous functional responses that include the expression of surface ligands, homotypic and heterotypic binding, protein synthesis, the release of pro-thrombotic and pro-inflammatory mediators, and signaling to leukocytes and endothelial cells. These responses and interactions are discussed in the text. Panel B: Immunocytochemistry (ICC) image demonstrating freshly isolated human platelets activated with thrombin and adhering to fibrinogen. In this image, the green stain identifies actin filaments, the red stain identifies fibrin strands (white arrowheads), and the magenta stain identifies the binding of wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) to sialic acid residues within platelets (white arrows). Panel C: The functional responses of activated platelets are pivotal in acute thrombotic disorders, such as stroke. Illustrated here are activated platelets interacting with and binding to monocytes and red blood cells (RBC) to form a thrombotic occlusion within the vascular lumen.

Human platelets possess adrenergic and dopaminergic receptors and avidly take up and secrete catecholamines7. While plasma catecholamine levels fluctuate dynamically, platelet catecholamine levels accumulate in a more stable, progressive pattern. Catecholamine secretion induces platelet activation and aggregation and may also potentiate the effects of other platelet agonists, including beta-thromboglobulin (β-TG) and platelet factor 4 (PF4). In settings of sympathoadrenal activation, including cardiovascular disease and sepsis, increases in circulating and platelet catecholamine levels may potentiate platelet functional responses.

Activated platelets aggregate with other platelets (homotypic aggregation) and with leukocytes, including neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes (heterotypic aggregation). Platelet-leukocyte aggregation induces the secretion of numerous proteins, peptides, biologically active lipids, and eicosanoid mediators by activated platelets6. In addition, platelet-leukocyte aggregation leads to the upregulation of pro-inflammatory gene synthesis by leukocytes, further contributing to thrombotic and inflammatory responses8–10. Increased platelet-leukocyte aggregates have been detected in patients with acute coronary syndromes, stroke, sepsis, acute lung injury, and other diseases6, 9, 11, 12. Dysregulated platelet-leukocyte interactions may contribute to injurious thrombotic and inflammatory responses in older patients, leading to an increased risk of adverse clinical outcomes.

Activated platelets serve as a platform for the induction and amplification of thrombus formation through numerous direct and indirect mechanisms. Platelet activation results in the transport of negatively charged phospholipids to the platelet surface membrane, forming a site for assembly of the tenase and prothrombinase complexes (which include activated factor(F) FVa, FVIIIa, and FXa)13. Platelets are also major reservoirs for pro-thrombotic, fibrinolytic, and inflammatory mediators. These key factors, many of which are stored within platelet granules and released upon activation, include fibrinogen, von willebrand factor (vWF), and plasminogen-activating inhibitor (PAI)-1. Fibrinogen and vWF both promote hemostasis and thrombosis (whether adaptive or maladaptive) while PAI-1 enhances fibrinolysis.

Older adults may have comorbid conditions (e.g. cancer, immobility, diabetes, obesity, etc.) that increase their risk of thrombo-inflammatory disorders. Nevertheless, underlying, age-related changes in platelets are also likely contributors. While these changes remain only partially understood (and thus present important opportunities for well-designed experimental and clinical studies), established and emerging evidence support the supposition that the platelet molecular signature and associated functional responses are altered during aging, contributing to thrombotic and inflammatory syndromes in older adults.

Intrinsic Platelet Activation, Aggregation, and Secretion are Enhanced in Older Adults

The classic platelet functions of activation and aggregation are altered during aging. For example, plasma levels of beta-thromboglobulin (β-TG) and platelet factor 4 (PF4), factors secreted upon platelet activation, are increased in healthy older adults14, 15. β-TG and PF4 are key effector molecules implicated in the pathophysiology of vascular wall and systemic inflammatory disorders and wound repair6.

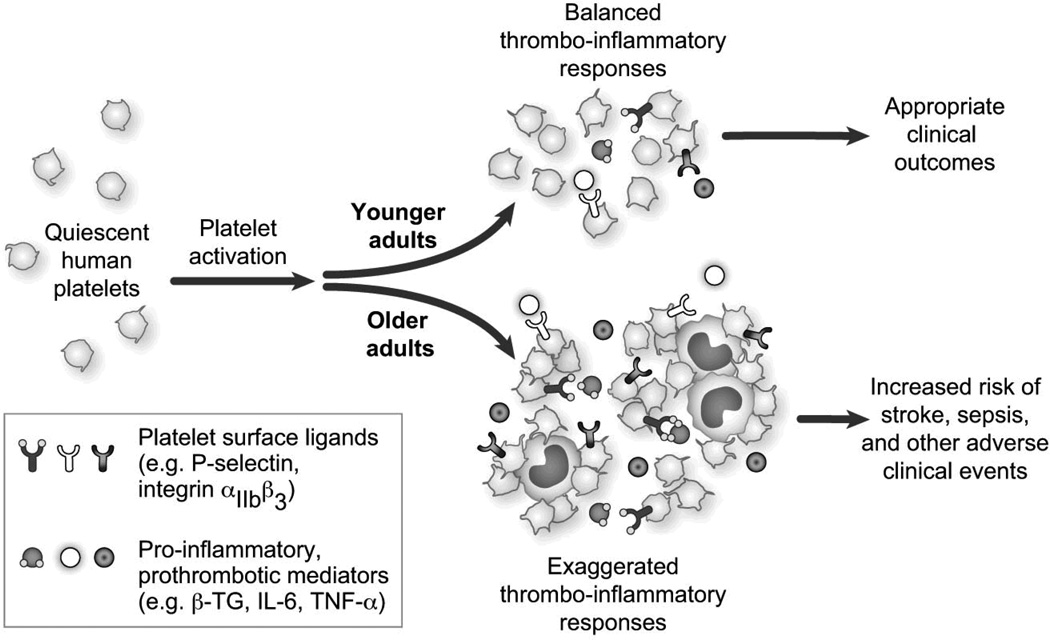

Bleeding time, a measure of platelet aggregation responses (i.e. greater aggregation associated with fast clot formation and shorter bleeding time), decreases with aging, an indirect demonstration that platelets are hyperreactive in older adults16, 17. Similarly, adults 60 years and older have reduced platelet aggregation thresholds in settings of stimulation with adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and collagen, compared to younger subjects14, 18, 19. Platelet alpha 2-adrenergic receptor density and receptor-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase, which mediate platelet aggregation, are also reduced in healthy older adults, contributing to a propensity towards platelet activation and homotypic aggregation responses20, 21. Older adults also have decreased platelet surface prostacyclin (PGI2) receptor density, increased platelet resistance to PGI2 inhibition, and increased urinary excretion of prostacyclin metabolites17, 22. PGI2 is an eicosanoid that inhibits platelet aggregation and leads to vasodilation. Similarly, in experimental and human studies endothelial and platelet nitric oxide production decreases in aging, further leading to heightened platelet activation, atherogenesis, and thrombosis23, 24. Interestingly, enhanced platelet activity in older healthy subjects correlates with higher basal platelet polyphosphoinositide content and thrombin-stimulated platelet polyphosphoinositide turnover, patterns indicative of age-related increases in platelet lipid concentration15. These observations demonstrate that in humans, aging is associated with increases in platelet transmembrane signaling, prostaglandin synthesis, and cyclooxygenase activity. Taken together, these findings provide evidence that the structure, intra-cellular content, and function of platelets are significantly altered in older adults, thus promoting a pro-thrombotic, pro-inflammatory milieu (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Aging is associated with platelet hyperreactivity, leading to increased expression of platelet surface ligands, exaggerated platelet and leukocyte aggregation, and enhanced release of pro-thrombotic and pro-inflammatory mediators. These changes contribute to the increased risk of adverse thrombo-inflammatory events in older adults and are discussed in the text.

Enhanced Platelet-Monocyte Interactions in Older Adults May Promote Injurious Thrombo-Inflammatory Responses

In addition to platelet activation and aggregation, monocyte phenotype and function are altered in older adults, resulting in amplified platelet-monocyte interactions and downstream thrombo-inflammatory effects. Circulating monocytes are innate immune cells that rapidly respond to infectious and inflammatory cuesto produce numerous regulatory and pro-inflammatory molecules. These molecules include interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α25, 26. Of these, IL-6 has been particularly implicated as a central mediator of dysregulated inflammatory pathways in aging27. IL-6 serum concentrations increase with aging, independent of confounding illnesses28. IL-6 mediates inflammatory activities and also upregulates the synthesis of hemostatic factors, such as fibrinogen27. IL-6 may also directly activate platelets, leading to platelet aggregation and secretion of arachidonic acid metabolites such as thromboxane A2 and β-TG29.

Monocyte surface antigens differentiate cellular sub-populations. The two major subsets are commonly defined based on the expression of the CD14 (also the receptor for lipopolysaccharide (LPS)) and CD16 (FcγRIII receptor) surface antigens. In healthy individuals, the majority of circulating monocytes (~95%) display the cell surface antigen CD14 and the remaining, smaller fraction of monocytes also express CD16, a pattern typically referred to as ‘classical’ CD14high/CD16low(or CD14++/CD16−). The remaining ‘non-classical’ monocytes are referred to as CD14low/CD16high(or CD14+/CD16+). Differences in the receptors and functional responses of these two monocyte subtypes are worth briefly noting as they provide biological links to thrombotic and inflammatory disorders. CD14high/CD16lowmonocytes possess the Chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 2 (CCR2), CD62L (L-selectin), and FCγRI. In contrast, CD14low/CD16high monocytes lack CCR2 but possess higher levels of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-II as well as the receptor FCγRII and, accordingly, synthesize greater amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines30. During acute settings of systemic activation and increased platelet-monocyte aggregation (such as sepsis), the population of circulating CD14low/CD16highmonocytes is expanded, potentially contributing to exaggerated cytokine generation and injurious thrombo-inflammatory responses30, 31.

Clinical studies suggest, however, that even in the absence of acute inflammatory syndromes, aging is associated with a shift towards non-classical, pro-inflammatory monocytes (e.g. CD14low/CD16high). For example, in a cohort of 181 healthy adults aged 18–88 years, non-classical CD14low/CD16highmonocyte counts increased with age and, consistent with phenotypic changes described above, demonstrated altered surface protein and chemokine receptor expression25. These findings were consistent with results from a smaller study of nursing home residents where isolated monocytes from older adults produced higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and/or exhibited imbalanced cytokine production32. Importantly, ex vivo incubation of freshly isolated monocytes with platelets from older, healthy adults leads to higher levels of IL-6 and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (Rondina MT, Campbell RC, et al; unpublished observations). Thus, taken together, these clinical data suggest that the chronic inflammatory condition that often exists in older adults may be due, in part, to shifts in monocyte sub-populations, a greater propensity towards interactions with platelets, and exaggerated, downstream, pro-inflammatory gene synthesis (Figure 2). While more investigations are needed, these molecular changes may have direct links to the increased risk of thrombotic and inflammatory events in older adults.

Platelet Hemostatic Factors are Increased in Older Adults

Aging is associated with alterations in many plasma coagulation factors that are stored, synthesized, and/or released by platelets. For example, platelet alpha granules contain fibrinogen, factor V, and vWF and upon activation release these and other mediators into the systemic milieu. Fibrinogen binds to activated αIIbβ3 integrin on the platelet surface, allowing for platelet activation and aggregation. Plasma fibrinogen levels increase with age, with an approximate 10 mg/dL incremental rise per decade in healthy subjects33. Increased fibrinogen levels are correlated with an increased risk of stroke and myocardial infarction34 and may also predispose older adults to VTE35. In similar fashion, vWF levels also increase with aging36, 37. vWF, which is produced constitutively in megakaryocytes and stored within platelets, binds collagen at areas of damaged endothelium or sub endothelium, thus contributing to the development of atherosclerotic plaque. vWF also binds to Factor VIII (FVIII), providing a stable platform for continued propagation of thrombin generation. FVIII levels also increase with aging and are associated with an increased risk of sub clinical cardio vascular disease and overt thrombosis38.

Platelet-associated components of the fibrinolytic pathway are substantially altered in older adults. For example, plasma levels of PAI-1, the major inhibitor of fibrinolysis, increase with aging39. While platelets are not the only source of PAI-1, platelets synthesize, store, and release large amounts of functional PAI-1 in a signal-dependent fashion40. Obesity, which is more common in older adults, may also increase PAI-1 levels, thus further enhancing the risk of thrombotic events. Interestingly, transgenic mice that overexpress a stable variant of human PAI-1 demonstrate spontaneous coronary artery thrombosis that only occurs in older mice (i.e. in an age-dependent fashion)41. While mouse models may not always precisely recapitulate human physiology, these observations provide intriguing mechanistic insights and support clinical observations in older adults.

Taken together, these findings highlight the numerous soluble thrombo-inflammatory factors that are substantially altered in older adults (Table 1). Platelets and platelet precursors (megakaryocytes) synthesize and/or internalize these factors and, in response to activating signals (e.g. damaged endothelium, bacterium or bacterial toxins, cytokines, and other agonists), rapidly release them into the systemic circulation. Thus, platelets in older adults may be “primed” for exaggerated responses, enhancing susceptibility to adverse clinical outcomes in settings of acute vascular and systemic inflammatory syndromes.

Table 1.

Summary of select age-related changes discussed in the manuscript text. A brief description of several of the key functions is also provided.

| Description and Function | Change During Aging | |

|---|---|---|

| Platelet factor 4 (PF4) | Secreted by platelets upon activation;pro-coagulant factor; chemoattractant for neutrophils and fibroblasts | Increased in older adults |

| Interleukin-6 | Pro-inflammatory cytokine; produced by monocytes bound to and activated by platelets; in some settings may activate platelets | Increased in older adults |

| Fibrinogen | Released by activated platelets; binds activated αIIbβ3 integrin on platelet surface; induces platelet aggregation | Increased in older adults |

| von Willebrand Factor (vWF) | Released by activated platelets; binds collagen at areas of damaged endothelium or sub-endothelium; binds Factor VIII allowing for thrombin generation | Increased in older adults |

| Plasminogen-activating inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) | Major inhibitor of fibrinolysis; synthesized, stored, and released by platelets | Increased in older adults |

Clinical and Therapeutic Considerations Targeting Dysregulated Platelet Responses in Older Adults

As noted above, the prevalence of thrombotic and inflammatory disorders increases markedly in older adults. While comorbid conditions may predispose the elderly to these disorders, aging-associated changes in platelet phenotype and function, increased levels of platelet hemostatic factors, and enhanced interactions with leukocytes and endothelial cells also contribute to these disease processes. Established and emerging therapies that inhibit platelet activation, aggregation, and adhesion continue to evolve. A brief review of anti-platelet agents (APAs) and their role in two thrombo-inflammatory disorders, ischemic stroke and sepsis, is provided here. We have chosen to focus on these two diseases given their high prevalence, morbidity, and mortality in older adults.

Anti-Platelet Agents in Ischemic Stroke

Alterations in platelet phenotype and function underlie the pathophysiology of ischemic stroke9 and APAs remain the cornerstone of therapy in preventing recurrent stroke. Current, FDA-approved APAs for secondary stroke prevention (Table 2) include aspirin, clopidogrel, and dipyridamole42. These drugs inhibit platelet activation and aggregation and improve clinical outcomes. While current guidelines generally accept any of these APAs for secondary stroke prevention, the combination of aspirin plus extended-release dipyridamole is recommended over aspirin alone in the 2012 American College of Chest Physician guidelines, particularly if cost is not an issue42.

Table 2.

Mechanisms of Action of Antiplatelet Agents and 2012 American College of Chest Physician (ACCP) Guidelines for the Prevention of Recurrent Stroke

| Antiplatelet Agent |

Primary Mechanism of Action |

Recommended Dose |

Grade of Evidencea |

Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | Inhibits cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1)-dependent synthesis of thromboxane A2 | 50–325mg once daily | 1A | Aspirin as monotherapy or in combination with extended-release dipyridamole |

| Dipyridamole | Inhibits phosphodiesterase enzymes that break down cAMP and cGMP; increases extracellular adenosine levels | 200mg twice daily | 1A | Combination of aspirin with extended-release dipyridamole preferred in some settings over aspirin monotherapy |

| Clopidogrel | Thienopyridine that specifically and irreversibly inhibits the P2Y12 ADP receptor | 75mg once daily | 1A | As monotherapy, particularly in patients allergic to aspirin |

Grade definitions: 1A, strong recommendation, high evidence; 1B, strong recommendation, moderate quality evidence; 2B, weak recommendation, moderate quality evidence. (ADP: adenosine diphosphate, cAMP: cyclic adenosine monophosphate, cGMP: cyclic guanisine monophosphate)

Several key aspects of these APAs are worth mentioning. Mechanistically, aspirin blocks cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) dependent synthesis of thromboxane while clopidogrel irreversibly inhibits the P2Y12 ADP receptor. Through inhibition of ADP-mediated platelet aggregation, clopidogrel, but not aspirin, also blocks platelet surface P-selectin, platelet-leukocyte aggregate formation, and the presence of tissue factor on the surface of platelets and leukocytes43, 44. Through these and other mechanisms, clopidogrel may attenuate downstream thrombo-inflammatory processes in addition to its direct inhibition of platelet aggregation. Consistent with these experimental data, clinical trial data from CAPRIE suggest that compared to aspirin 325mg daily, clopidogrel (at a dose of 75mg daily) is more effective at reducing the composite endpoint of stroke, myocardial infarction, or vascular death (5.32% vs. 5.83%, relative risk reduction of 8.7%, p=0.043) without significant increases in bleeding risk45.

Dipyridamole inhibits phosphodiesterase enzymes, leading to increases in extra cellular adenosine levels. While a potent anti-platelet agent, dipyridamole also has selective anti-inflammatory properties. For example, in vitro investigations using co-incubated human platelets and monocytes demonstrate that dipyridamole (at concentrations similar to those achieved clinically), attenuates IL-8 and MCP-1 synthesis46. In these same investigations, aspirin did not block pro-inflammatory gene synthesis. These experimental observations support clinical trial data suggesting that compared to aspirin as monotherapy, the combination of aspirin plus extended-release dipyridamole results in significant reductions in adverse clinical events, including vascular death, stroke, and myocardial infarction47. Moreover, aspirin plus extended-release dipyridamole have similar safety and efficacy profiles relative to clopidogrel monotherapy48. Aspirin plus clopidogrel is generally not a recommended therapy for secondary stroke prevention. This combination increases bleeding risk without offering any significant clinical benefits over aspirin or clopidogrel monotherapy.

Anti-Platelet Agents in Septic Syndromes

Septic syndromes, including sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock, are the 10th leading cause of death among older adults. Septic syndromes are characterized by pervasive platelet activation, adhesion, and aggregation. As a result, pre-formed and newly-synthesized platelet mediators (IL-1β, tissue factor, PF4, β-TG, p-selectin, etc.) are released into the systemic milieu, contributing to exaggerated inflammation, micro- and macro-vascular thrombosis, organ failure, and death. While still incompletely understood, age-associated platelet hyperreactivity, along with expansion in non-classical monocyte populations, may strongly influence the increased incidence, severity, and mortality from sepsis in older adults5. Consistent with this supposition, older adults with the highest circulating levels of TNF-α and IL-6 (pro-inflammatory cytokines produced upon platelet-monocyte aggregate formation) had the highest risk of sepsis due to pneumonia, independent of medical conditions, steroid use, or smoking status49.

Given the important role that platelets play in the pathophysiology of septic syndromes, recent studies have examined whether APAs improve clinical outcomes in both experimental and clinical sepsis. In a rat model of endotoxin-induced systemic inflammation, clopidogrelreduced the synthesis of TNF-α and IL-6, and attenuated liver and lung inflammation50. Similarly, in acid-induced and transfusion-related lung injury models, platelet depletion as well as inhibiting platelet adhesion and activation, protects against lung injury51, 52. In clinical studies, pre-hospital aspirin therapy was associated with significantly lower rates of acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome (ALI/ARDS), which is commonly caused by sepsis (incidence of ALI/ARDS of 17.7% vs. 28.0% for pre-hospital, aspirin non-users, p<0.05)53. Similarly, a larger retrospective analysis examined mortality rates in more than 1600 critically ill patients admitted to an ICU, based on the in-hospital prescription of APAs for the secondary prevention of vascular disease. Overall, patients who received an APA (approximately 25% of the entire cohort) had significant mortality reductions, without any increase in bleeding complications54. Studies in critically ill patients receiving blood transfusions, another common risk factor for ALI/ARDS, have also found benefit with APAs55.

Thus, these emerging data highlight an intriguing new potential therapeutic role for APAs in the prevention of ALI/ARDS. Furthermore, in older patients, who often have an increased bleeding risk, low-dose aspirin offers the possibility or reducing adverse clinical events in critical illness without causing significant harm. A large, prospective randomized clinical trial evaluating the role of aspirin for the prevention of ALI in hospitalized, high risk patients is currently ongoing56.

Conclusions

In conclusion, aging is associated with altered and dysregulated platelet functions, leading to platelet hyperreactivity, enhanced aggregation and interactions with other cells, and an increased risk of injurious thrombo-inflammatory events. Nevertheless, our understanding of the molecular and phenotypic changes in platelets with aging remain only partially understood, limiting advances in therapeutic options. Currently approved anti-platelet agents have clear roles in cardiovascular disease prevention and treatment and emerging roles in acute systemic inflammatory syndromes such as sepsis and ALI/ARDS. Ongoing research is needed to fill these knowledge gaps and identify novel therapies that safely and effectively reduce the burden of thrombo-inflammatory disease in older adults.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The corresponding author, Dr. Rondina, has listed everyone who contributed significantly to this work and has obtained written consent from all contributors who are not authors and are named in the acknowledgment section. We thank Ms. Diana Lim for her outstanding skill with figure preparation and Ms. Alex Greer for her excellent editorial assistance.

Funding Support: This work was supported by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute and the National Institute of Aging (K23HL092161, R03AG040631, and 1U54 HL112311 to M.T.R.).

Sponsor’s Role: The sponsor had no role in literature review, analysis, or preparation of paper.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Supiano is a Board member of the American Geriatrics Society and the Association of Directors of Geriatric Academic Programs. The other authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed significantly to the conception and design of this work (MTR, Donya Mohebali, David Kaplan), drafting and revising the article critically (Matthew T. Rondina, Donya Mohebali, CK, McKenzie Carlisle, Mark A. Supiano), and/or final approval of the version being submitted (Matthew T. Rondina, Donya Mohebali, CK, McKenzie Carlisle, Mark A. Supiano). Each author will also be involved in the final approval of the manuscript version to be published.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kung HC, Hoyert DL, Xu J, et al. Deaths: final data for 2005. National vital statistics reports: from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Nat Vital Stat Syst. 2008;56:1–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stein PD, Hull RD, Kayali F, et al. Venous thromboembolism according to age: the impact of an aging population. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2260–2265. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.20.2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White RH. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107:I4–I18. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078468.11849.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piazza G, Goldhaber SZ, Lessard DM, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with symptomatic atherosclerosis. Thromb Haemost. 2011;106:1095–1102. doi: 10.1160/TH11-07-0469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin GS, Mannino DM, Moss M. The effect of age on the development and outcome of adult sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:15–21. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000194535.82812.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vieira-de-Abreu A, Rondina MT, Weyrich AS, et al. Inflammation. In: Michelson AD, editor. Platelets. 3rd edn. New York: Elsevier; 2012. pp. 733–766. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anfossi G, Trovati M. Role of catecholamines in platelet function: pathophysiological and clinical significance. Eur J Clin Invest. 1996;26:353–370. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1996.150293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Passacquale G, Vamadevan P, Pereira L, et al. Monocyte-platelet interaction induces a pro-inflammatory phenotype in circulating monocytes. PloS one. 2011;6:e25595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franks ZG, Campbell RA, Weyrich AS, et al. Platelet-leukocyte interactions link inflammatory and thromboembolic events in ischemic stroke. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1207:11–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05733.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flick MJ, Du X, Witte DP, et al. Leukocyte engagement of fibrin(ogen) via the integrin receptor alphaMbeta2/Mac-1 is critical for host inflammatory response in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1596–1606. doi: 10.1172/JCI20741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lukasik M, Dworacki G, Kufel-Grabowska J, et al. Upregulation of CD40 ligand and enhanced monocyte-platelet aggregate formation are associated with worse clinical outcome after ischaemic stroke. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107:346–355. doi: 10.1160/TH11-05-0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rondina MT, Weyrich AS, Zimmerman GA. Platelets as cellular effectors of inflammation in vascular diseases. Circ Res. 2013;112:1506–1519. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolberg AS, Campbell RA. Thrombin generation, fibrin clot formation and hemostasis. Transfus Apher Sci. 2008;38:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zahavi J, Jones NA, Leyton J, et al. Enhanced in vivo platelet "release reaction" in old healthy individuals. Thromb Res. 1980;17:329–336. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(80)90067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bastyr EJ, 3rd, Kadrofske MM, Vinik AI. Platelet activity and phosphoinositide turnover increase with advancing age. Am J Med. 1990;88:601–606. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90525-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jorgensen KA, Dyerberg J, Olesen AS, Stoffersen E. Acetylsalicylic acid, bleeding time and age. Thromb Res. 1980;19:799–805. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(80)90007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reilly IA, FitzGerald GA. Eicosenoid biosynthesis and platelet function with advancing age. Thromb Res. 1986;41:545–554. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(86)91700-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson M, Ramey E, Ramwell PW. Sex and age differences in human platelet aggregation. Nature. 1975;253:355–357. doi: 10.1038/253355a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sie P, Montagut J, Blanc M, et al. Evaluation of some platelet parameters in a group of elderly people. Thromb Haemost. 1981;45:197–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Supiano MA, Hogikyan RV. High affinity platelet alpha 2-adrenergic receptor density is decreased in older humans. J Gerontol. 1993;48:B173–B179. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.5.b173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Supiano MA, Linares OA, Halter JB, et al. Functional uncoupling of the platelet alpha 2-adrenergic receptor-adenylate cyclase complex in the elderly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987;64:1160–1164. doi: 10.1210/jcem-64-6-1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Modesti PA, Fortini A, Abbate R, et al. Age related changes of platelet prostacyclin receptors in humans. Eur J Clin Invest. 1985;15:204–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1985.tb00169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chou TC, Yen MH, Li CY, et al. Alterations of nitric oxide synthase expression with aging and hypertension in rats. Hypertension. 1998;31:643–648. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.2.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loscalzo J. Nitric oxide insufficiency, platelet activation, and arterial thrombosis. Circ Res. 2001;88:756–762. doi: 10.1161/hh0801.089861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seidler S, Zimmermann HW, Bartneck M, et al. Age-dependent alterations of monocyte subsets and monocyte-related chemokine pathways in healthy adults. BMC Immunol. 2010;11:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-11-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fagiolo U, Cossarizza A, Scala E, et al. Increased cytokine production in mononuclear cells of healthy elderly people. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2375–2378. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ershler WB. Interleukin-6: a cytokine for gerontologists. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41:176–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb02054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrucci L, Corsi A, Lauretani F, et al. The origins of age-related proinflammatory state. Blood. 2005;105:2294–2299. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oleksowicz L, Mrowiec Z, Zuckerman D, et al. Platelet activation induced by interleukin-6: evidence for a mechanism involving arachidonic acid metabolism. Thromb Haemost. 1994;72:302–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ziegler-Heitbrock L. The CD14+ CD16+ blood monocytes: Their role in infection and inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:584–592. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0806510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fingerle G, Pforte A, Passlick B, et al. The novel subset of CD14+/CD16+ blood monocytes is expanded in sepsis patients. Blood. 1993;82:3170–3176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sadeghi HM, Schnelle JF, Thoma JK, et al. Phenotypic and functional characteristics of circulating monocytes of elderly persons. Exp Gerontol. 1999;34:959–970. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(99)00065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Franchini M. Hemostasis and aging. Crit Reviews Oncol/Hematol. 2006;60:144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilhelmsen L, Svardsudd K, Korsan-Bengtsen K, et al. Fibrinogen as a risk factor for stroke and myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:501–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198408233110804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farrell DH. gamma' Fibrinogen as a novel marker of thrombotic disease. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2012;50:1903–1909. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2012-0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conlan MG, Folsom AR, Finch A, et al. Associations of factor VIII and von Willebrand factor with age, race, sex, risk factors for atherosclerosis. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Thromb Haemost. 1993;70:380–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coppola R, Mari D, Lattuada A, Franceschi C. Von Willebrand factor in Italian centenarians. Haematologica. 2003;88:39–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tracy RP, Arnold AM, Ettinger W, et al. The relationship of fibrinogen and factors VII and VIII to incident cardiovascular disease and death in the elderly: Results from the cardiovascular health study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:1776–1783. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.7.1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mehta J, Mehta P, Lawson D, et al. Plasma tissue plasminogen activator inhibitor levels in coronary artery disease: Correlation with age and serum triglyceride concentrations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1987;9:263–268. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(87)80373-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nylander M, Osman A, Ramstrom S, et al. The role of thrombin receptors PAR1 and PAR4 for PAI-1 storage, synthesis and secretion by human platelets. Thromb Res. 2012;129:e51–e58. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eren M, Painter CA, Atkinson JB, et al. Age-dependent spontaneous coronary arterial thrombosis in transgenic mice that express a stable form of human plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. Circulation. 2002;106:491–496. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000023186.60090.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lansberg MG, O'Donnell MJ, Khatri P, et al. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e601S–e636S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klinkhardt U, Bauersachs R, Adams J, et al. Clopidogrel but not aspirin reduces P-selectin expression and formation of platelet-leukocyte aggregates in patients with atherosclerotic vascular disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;73:232–241. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2003.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Storey RF, Judge HM, Wilcox RG, Heptinstall S. Inhibition of ADP-induced P-selectin expression and platelet-leukocyte conjugate formation by clopidogrel and the P2Y12 receptor antagonist AR-C69931MX but not aspirin. Thromb Haemost. 2002;88:488–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Committee CS. A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). CAPRIE Steering Committee. Lancet. 1996;348:1329–1339. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)09457-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weyrich AS, Denis MM, Kuhlmann-Eyre JR, et al. Dipyridamole selectively inhibits inflammatory gene expression in platelet-monocyte aggregates. Circulation. 2005;111:633–642. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000154607.90506.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Group ES, Halkes PH, van Gijn J, et al. Aspirin plus dipyridamole versus aspirin alone after cerebral ischaemia of arterial origin (ESPRIT): Randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367:1665–1673. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68734-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sacco RL, Diener HC, Yusuf S, et al. Aspirin and extended-release dipyridamole versus clopidogrel for recurrent stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1238–1251. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yende S, Tuomanen EI, Wunderink R, et al. Preinfection systemic inflammatory markers and risk of hospitalization due to pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:1440–1446. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200506-888OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hagiwara S, Iwasaka H, Hasegawa A, et al. Adenosine diphosphate receptor antagonist clopidogrel sulfate attenuates LPS-induced systemic inflammation in a rat model. Shock. 2011;35:289–292. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181f48987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zarbock A, Singbartl K, Ley K. Complete reversal of acid-induced acute lung injury by blocking of platelet-neutrophil aggregation. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3211–3219. doi: 10.1172/JCI29499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Looney MR, Nguyen JX, Hu Y, et al. Platelet depletion and aspirin treatment protect mice in a two-event model of transfusion-related acute lung injury. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3450–3461. doi: 10.1172/JCI38432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Erlich JM, Talmor DS, Cartin-Ceba R, et al. Prehospitalization antiplatelet therapy is associated with a reduced incidence of acute lung injury: A population-based cohort study. Chest. 2011;139:289–295. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Winning J, Neumann J, Kohl M, et al. Antiplatelet drugs and outcome in mixed admissions to an intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:32–37. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b4275c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harr JN, Moore EE, Johnson J, et al. Antiplatelet therapy is associated with decreased transfusion-associated risk of lung dysfunction, multiple organ failure, and mortality in trauma patients. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:399–404. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31826ab38b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kor DJ, Talmor DS, Banner-Goodspeed VM, et al. Lung Injury Prevention with Aspirin (LIPS-A): A protocol for a multicentre randomised clinical trial in medical patients at high risk of acute lung injury. BMJ. 2012;2:e001606. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]