Abstract

Patients with coarctation of the aorta (CoA) are prone to morbidity including atherosclerotic plaque that has been shown to correlate with altered wall shear stress (WSS) in the descending thoracic aorta (dAo). We created the first patient-specific computational fluid dynamics (CFD) model of a CoA patient treated by Palmaz stenting to date, and compared resulting WSS distributions to those from virtual implantation of GenesisXD and modified NumedCP stents also commonly used for CoA. CFD models were created from magnetic resonance imaging, fluoroscopy and blood pressure (BP) data. Simulations incorporated vessel deformation, downstream vascular resistance and compliance to match measured data and generate blood flow velocity and time-averaged WSS (TAWSS) results. TAWSS was quantified longitudinally and circumferentially in the stented region and dAo. While modest differences were seen in the distal portion of the stented region, marked differences were observed downstream along the posterior dAo and depended on stent type. The GenesisXD model had the least area of TAWSS values exceeding the threshold for platelet aggregation in vitro, followed by the Palmaz and NumedCP stents. Alterations in local blood flow patterns and WSS imparted on the dAo appear to depend on the type of stent implanted for CoA. Following confirmation in larger studies, these findings may aid pediatric interventional cardiologists in selecting the most appropriate stent for each patient, and ultimately reduce long-term morbidity following treatment for CoA by stenting.

Keywords: CHD great vessel anomalies, computer simulation, circulatory hemodynamics, aortic operation, computer applications

INTRODUCTION

Coarctation of the aorta (CoA) is characterized by a stenosis of the proximal descending thoracic aorta and is one of the most common congenital heart defects (8–11%) affecting 5,000 to 8,000 births annually in the United States[13,5]. While surgical therapy has long been the mainstay of treatment, the less invasive nature, shorter hospitalization, reduced pain and decreased cost of catheter-based therapies has led to them playing an increasing role[30]. In particular, stents have become a popular choice for their ability to cause less trauma and resist recoarctation more effectively relative to balloon angioplasty.

Since the first clinical use of stents for CoA in 1991, numerous reports have shown their ability to successfully reduce the pressure gradient across a coarctation and generally restore the aorta to normal caliber[11,21,27,28]. Although stents with various designs may satisfy these criteria for success, the geometry of stents used in other vascular beds is known to influence local flow disturbances[19,24,35] including indices of wall shear stress (WSS, defined as the tangential force per unit area exerted on a blood vessel wall as a result of flowing blood). Interestingly, in a study of ten middle-aged adults with pre-existing plaques, areas of low time-averaged WSS (TAWSS) were found in a rotating pattern progressing down the descending thoracic aorta (dAo) and correlated with areas of atherosclerosis[34]. Other studies have indicated excessively high WSS can also be deleterious by initiating platelet aggregation[12]. Thus, geometric intricacies of the particular stent used to treat CoA may uniquely influence the likelihood and severity of future dAo pathology. Stent-induced local flow alterations may also be accentuated in cases of residual narrowing where even a modest reduction in diameter within the coarctation region can accelerate blood through the stent and further contribute to deleterious downstream flow alterations. No studies to date have characterized local WSS after stenting for CoA.

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) enables detailed spatiotemporal quantification of hemodynamic indices including WSS based on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and blood pressure (BP) data. CFD also facilitates virtual treatment of CoA for comparison of hemodynamic alterations between stents in the same vessel[10]. The objective of the current investigation was to create the first patient-specific CFD model of a patient treated for CoA by stenting, and compare distributions of WSS to those resulting from virtual implantation of two other stents commonly used to treat CoA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A CFD model of the vasculature was created by converting medical imaging data into a geometrically representative computer model[36]. MRI was performed for a 15 year old patient previously treated for CoA by Palmaz stent placement (Cordis Corp., Miami Lakes, FL) as part of a clinically ordered imaging session and after IRB approval facilitating use of the data for computational modeling. Gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) and phase contrast MRI (PC-MRI) were conducted to delineate vascular morphology[20,36] and calculate time-resolved volumetric blood flow[17], respectively. Upper extremity supine systolic, mean and diastolic BP values of 113, 85 and 64 mmHg, respectively, were measured using an automated sphygmometer cuff.

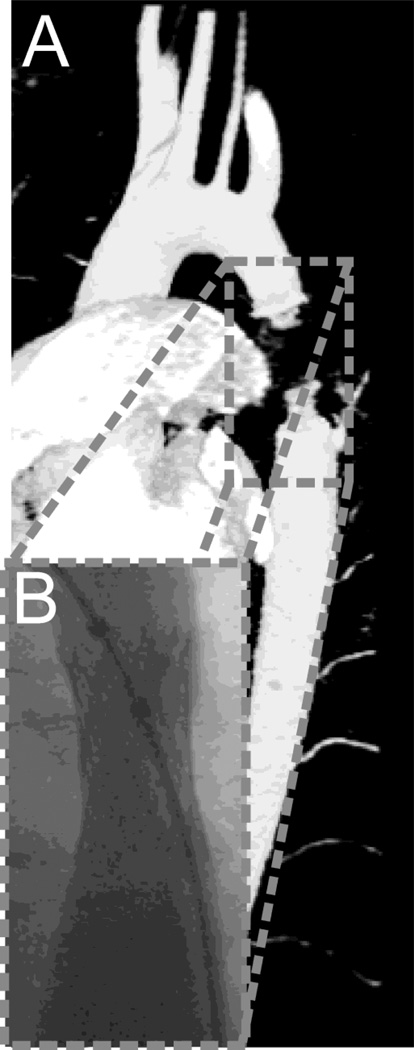

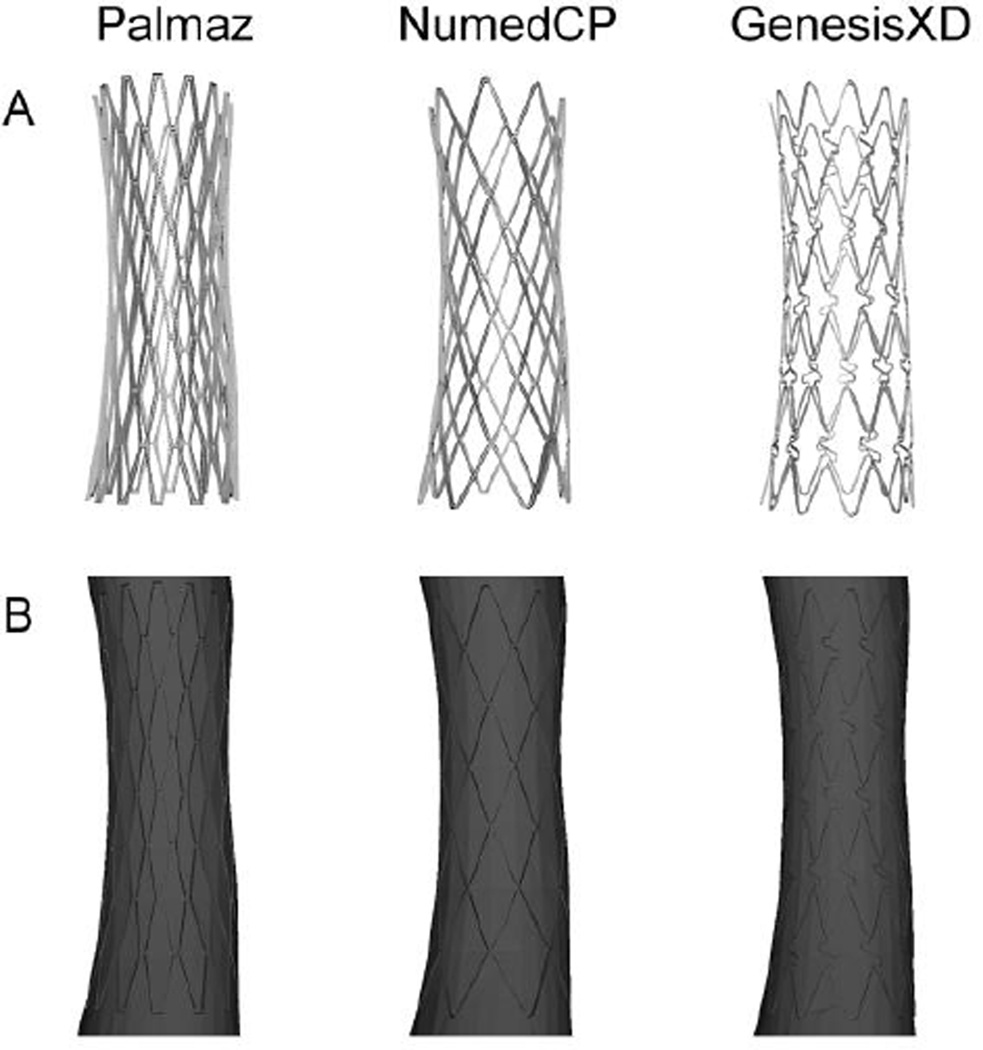

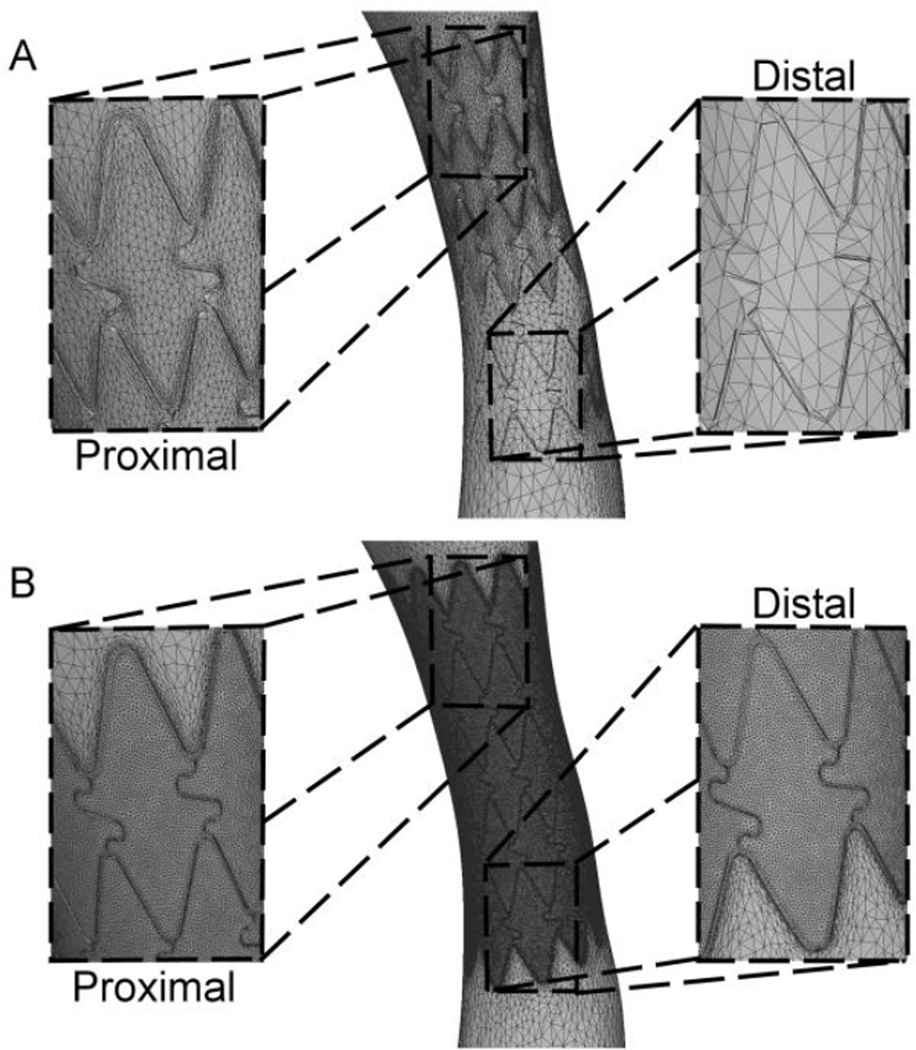

MRA data was processed for gradient nonlinearities[2] before CFD models were constructed using the SimVascular software package (https://simtk.org)[36]. Magnetic field inhomogeneities from the stent caused signal dropout in the volumetric MRA data (Figure 1A). Fluoroscopic angiography data from the same time period (Figure 1B) was therefore used to extract the dimensions and positioning of the stent within the coarctation region (e.g. average diameter in stented region 12 mm). Geometric characteristics (Table 1) of the implanted and two additional stents, a modified Numed Cheatham Platinum (Hopkinton, NY) with rectangular, as compared to circular, struts and a Genesis XD (Cordis Corp.), were obtained from literature[4,7]. These stents were created using computer aided design software (Solidworks Corp., Concord, MA). Each was then virtually implanted into a separate, but otherwise equivalent, CFD model of the patient's thoracic aorta before stenting (Figure 2) using the methods described by Gundert et al[10]. It was assumed that no portion of the stent's thickness was embedded in the aortic wall immediately after implantation since data was not available on the potentially differing amounts of strut thickness recessed into the aortic wall for each stent. Models were discretized using a commercially available, automatic mesh generation program (MeshSim, Simmetrix, Clifton Park, NY). Meshes were refined using an adaptive method[23,29] to automatically allocate elements based on the complexity of local flow patterns outside the stented region and reduce computational cost as compared to isotropic meshes. The size of elements near stent struts and the vessel wall were explicitly defined to adequately resolve flow features throughout the stent (Figure 3, Supporting Information). Simulations incorporating aortic deformation[6,17], downstream vascular resistance and compliance[32,31] were performed using a novel stabilized finite element method to solve the conservation of mass (continuity), balance of fluid momentum (Navier-Stokes) and vessel wall elastodynamics equations[6] until flow rate and BP fields were periodic and matched measured data.

Figure 1.

Rendering of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data (A) and an angiographic image of the same patient obtained by fluoroscopy (B). CFD models were constructed using the MRI data with diameters of the stented region extracted from the fluoroscopy data to account for signal dropout created by artifacts due to the implanted Palmaz stent.

Table 1.

Design attributes of stents virtually implanted for CoA

| Palmaz | NumedCP | GenesisXD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thickness (mm) | 0.312 | 0.254 | 0.173 |

| Strut width (mm) | 0.338 | 0.3 | 0.205 (macro) 0.123 (micro) |

| Number of circumferential repeating units | 14 | 8 | 11 |

| Number of longitudinal repeating units | 7 | 6 | 5 |

| Stent/Vessel contact area (mm2) | 243 | 128 | 106 |

Figure 2.

Palmaz (left), NumedCP (middle) and GenesisXD (right) stents created using computer aided design software (top row). These stents were then subtracted from copies of the same patient-specific computational model to produce the flow domain associated with each stent (bottom row).

Figure 3.

Example illustrating the meshing approach for the stented region. An adaptive meshing process created elements of appropriate size in proximal intrastrut regions (A, top images), but regions of low velocity adjacent to stents struts and the distal portion of the stented region contained fewer and larger elements after the adaptive process. The minimum edge size of all elements within the proximal stented region after adapting was therefore determined and explicitly applied within the stented region to generate meshes containing ~8.3 million elements (B, bottom images).

Results for TAWSS within the stented region and the dAo distal to the stent were quantified by unwrapping the surface geometry of the vessel at the inner curvature[16,33]. TAWSS values were then plotted circumferentially for the proximal and distal regions of the stent as well as four locations along the dAo. TAWSS values were also plotted longitudinally along regions of particular interest within the dAo. To further delineate local differences in TAWSS due to stent type, the area of the dAo exposed to a high TAWSS threshold of 50 dyne/cm2 (at which platelet aggregation occurs in vitro[12]) was quantified.

RESULTS

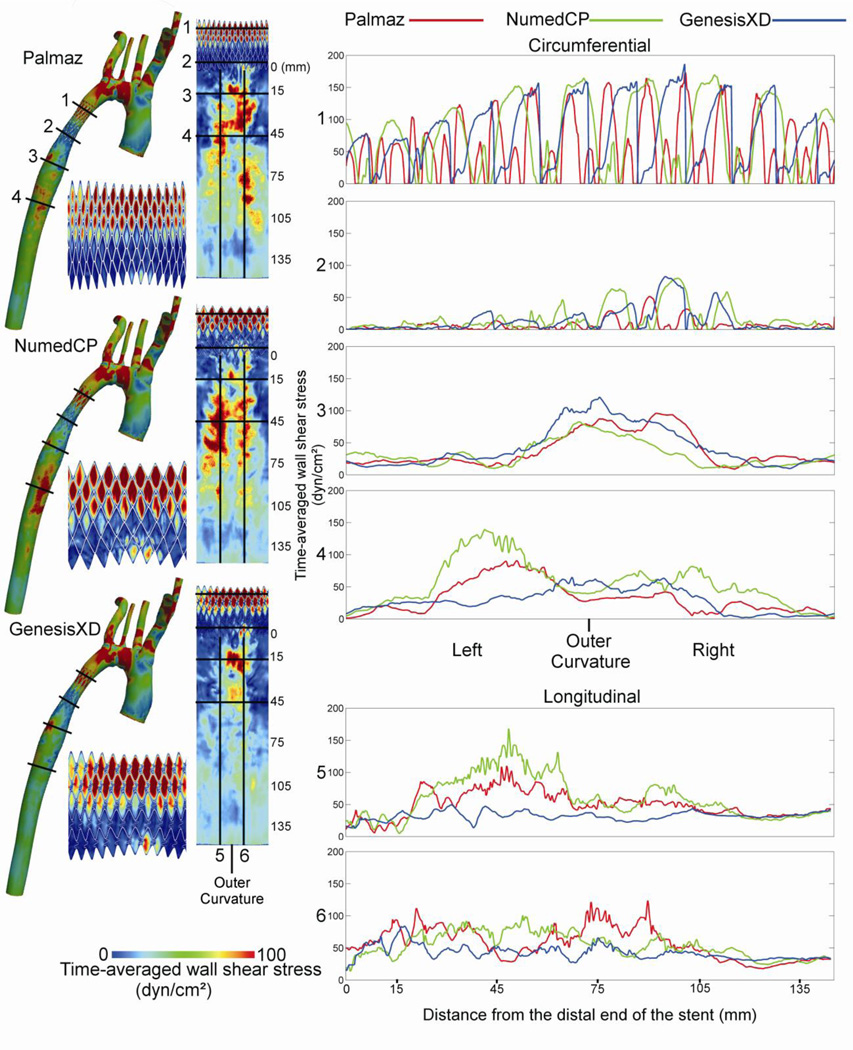

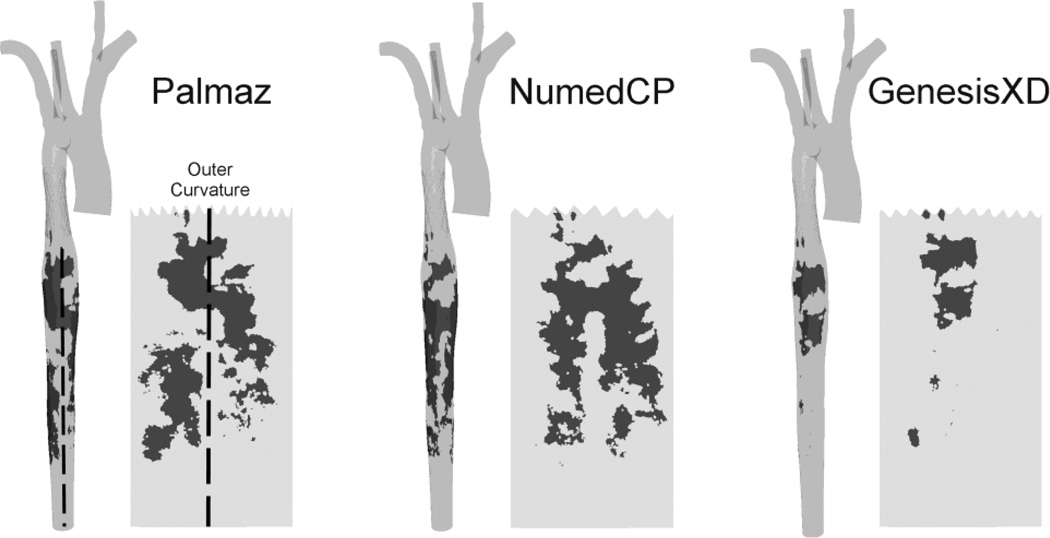

TAWSS values >100 dyn/cm2 were observed within the proximal portion of the stented region and in the dAo 10 mm to 110 mm distal to the stent, with varying severity depending on stent type (Figure 4). The Palmaz stent showed two focal regions of elevated TAWSS in the dAo. The first initiated along the outer right luminal surface ~10 mm distal to the stent and extended to the center and then the outer left surface over ~40 mm. The second was located 75–100 mm distal to the stent along the outer right luminal surface. The NumedCP stent also displayed two focal regions of elevated TAWSS along the outer left and right luminal surfaces ~30 to 70 mm distal to the stent. In contrast, the GenesisXD stent displayed a single focal region of elevated TAWSS along center of the outer luminal surface from ~10 to 20 mm distal to the stent. The lowest TAWSS values (<25 dyn/cm2) appeared within the distal stented region and along the inner curvature of the proximal dAo 0 to 50 mm downstream regardless of the type of stent implanted.

Figure 4.

Distributions of time-averaged wall shear stress for the Palmaz, NumedCP, and GenesisXD stents. CFD results for the full model are shown next to spatial maps that have been unwrapped about the outer (posterior) surface for the stented region and the distal descending aorta. Circumferential and longitudinal plots are also shown at several locations: proximal stented region (1), distal stented region (2), 15 mm distal to the stent (3), 45 mm distal to the stent (4), as well as the left (5) and right (6) portions of the outer curvature. Note that values occurring atop stent struts have been removed to improve the legibility of plots.

Circumferential quantification revealed higher TAWSS along the outer portion of the stented region (Figure 4, locations 1 and 2), while TAWSS along the inner curvature did not exceed 20 dyn/cm2. Differences in TAWSS were more pronounced in the distal versus the proximal stented region. For example, TAWSS peaked at ~ 80 dyn/cm2 in the distal region of the GenesisXD simulation as compared to values >80 dyn/cm2 throughout the entire proximal stented region. The Palmaz stent had the lowest value of peak TAWSS in the distal region (51.7 dyn/cm2) as compared to NumedCP (80.0 dyn/cm2) and GenesisXD (82.4 dyn/cm2). The region with elevated TAWSS ~15 mm distal to the stent (Figure 4, location 3) was also quantified circumferentially. Spatial distributions of TAWSS were similar among stents with highest values along the outer curvature (peak TAWSS of 95.7, 82.6 and 121 dyn/cm2 for Palmaz, NumedCP and GenesisXD, respectively) and low TAWSS values <25 dyn/cm2. Peak TAWSS ~45 mm distal to the stent (Figure 4, location 4) was located along the left outer luminal surface of the dAo for Palmaz and NumedCP (90.5 and 139 dyn/cm2respectively), while the GenesisXD had a more uniform TAWSS distribution with a peak value of 64.8 dyn/cm2 along the outer curvature.

Longitudinal quantification was additionally performed along regions of the dAo distal to the stent with elevated TAWSS. Distributions of TAWSS along the outer left luminal surface for NumedCP and Palmaz stents (Figure 4, location 5) were elevated between 20 mm and 110 mm with peak values of 168 and 110 dyn/cm2 as compared to 49.3 dyn/cm2 for the GenesisXD. Differences in TAWSS along the right outer luminal surface (Figure 4, location 6) were less pronounced between stents with values for GenesisXD generally lower than others.

Figure 5 shows the area of TAWSS in the dAo exceeding the threshold for platelet aggregation in vitro[12]. The GenesisXD model had the least area of TAWSS above the threshold (Table 2) followed by the Palmaz and NumedCP stents.

Figure 5.

Locations of elevated time-averaged wall shear stress for the Palmaz, NumedCP, and GenesisXD stents. The full CFD model results are shown next to spatial maps that have been unwrapped about the outer (posterior) surface for the descending aorta distal to the stent. Regions with time-averaged wall shear stress above 50 dyn/cm2 have been made opaque. Values above this threshold have been previously correlated with platelet aggregation.

Table 2.

The area (mm2) of the descending thoracic luminal surface exposed time-averaged wall shear stress above the threshold for platelet aggregation in vitro

| Palmaz | NumedCP | GenesisXD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Area (mm2) in descending aorta with TAWSS above the threshold (mm2) | 1880 | 2010 | 559 |

DISCUSSION

The objective of this investigation was to create the first patient-specific CFD model of a patient treated for CoA by stenting, and compare distributions of WSS in the stent and dAo to those from virtual implantation of two other stents commonly used to treat CoA. This objective was motivated by stents playing an increasing role in the treatment of CoA. The results illustrate how CFD can provide useful insight and potentially scrutinize stent performance in a retrospective or prospective manner.

The main finding of this investigation is that alterations in local flow patterns and WSS imparted on the thoracic aorta in patients treated for CoA may uniquely depend on the type of stent implanted. While modest differences were seen in the distal portion of the stented region, marked differences were observed downstream along the posterior surface of the dAo. It is important to note that the methods applied with CFD models were carefully controlled to isolate the influence of stent design. The overall vessel geometry, including residual narrowing in the stented region, was consistent between simulations. Inlet and outlet boundary conditions were also consistent for all models, resulting in <0.3% difference in the distribution of flow to the dAo between simulations for each stent type. An analysis of mesh independence (Supporting Information) confirmed differences were not due to aspects of the computational meshes used for each simulation.

The current results indicate adverse local flow alterations were least severe for the GenesisXD, for which regions of elevated TAWSS and variability at the specific locations quantified were smallest. In contrast, the Palmaz and NumedCP stents both exhibited a greater percentage of high TAWSS along the posterior dAo. These differences are likely rooted in the design attributes of each stent. Attributes including strut thickness, proximity, angle relative to the primary flow direction, and ratio of stent-to-vessel area were predictive of adverse distributions of WSS in prior studies[24,3,18]. Since all stent struts disturb local flow patterns, thicker struts protrude further into the flow domain and increase the severity of these disturbances. Similarly, the relative ratio of stent-to-vessel area influences the total amount of the vessel wall exposed to potentially deleterious flow patterns. The angle of struts relative to the primary direction of fluid flow, together with the overall stent geometry, can also influence the severity of flow disturbances caused by a stent. Stents with their linkages primarily arranged longitudinally have the potential to cause less severe flow disruptions as compared to ring-and-link designs primarily arranged circumferentially. For example, when stents are expanded to larger diameters, as can occur with redilation for recurrent CoA, their overall linkage design becomes arranged in a less longitudinal manner causing adjacent layers of fluid to be redirected more abruptly as they pass through the stented region. In contrast, larger intrastrut regions aligned in the primary direction of fluid flow limit separation and stagnation between struts. The Palmaz stent modeled in the current investigation with the greatest strut thickness and width, number of circumferential and longitudinal repeating units, and ratio of stent-to-vessel area showed two focal regions of elevated TAWSS in the downstream dAo. The NumedCP stent with larger intrastrut area and only slightly thinner struts also displayed two focal regions of elevated TAWSS along the dAo. In contrast, the GenesisXD stent with the thinnest struts, large intrastrut regions, and ratio of stent-to-vessel area similar to the NumedCP stent displayed a single focal region of elevated TAWSS downstream of the stent.

An analysis of Reynolds numbers may further explain the current results. The Reynolds number (Re) is a dimensionless parameter describing the ratio of convective inertial forces to viscous forces. In general, values <2,000 constitute laminar flow where adjacent layers of fluid move in layers without mixing, while those >2,000 may be characterized as transitional or turbulent depending on specific details of the local flow domain. Mean and peak Re in the dAo for the patient studied here were ~1,750 and 5,300, respectively. These Re suggest flow was generally laminar throughout the cardiac cycle, but there were undoubtedly portions during which flow was transitional or turbulent. During these times modest differences in local vessel geometry caused by design attributes of a particular stent could cause perturbations resulting in irregular erratic intermingling of fluid particles downstream of the stent and manifest in the differences observed.

The current results may have important clinical implications as low TAWSS values are associated with the onset and progression of cardiovascular disease in many vascular beds[37], and TAWSS above a certain preferential value may be associated endothelial injury, plaque rupture, or thrombogenesis[14,15]. For example, a previous study of healthy young adults found areas of adverse WSS in a rotating pattern progressing down the dAo[8]. A second previous study of ten middle-aged adults with pre-existing plaques revealed similar WSS patterns that correlated with areas of atherosclerosis[34]. When joined with the current results, the collective findings suggest the type of stent used to treat CoA may uniquely influence the future location and severity of aortic plaque. This may be of particular importance for CoA patients since their stents are often implanted at a younger age than adults receiving stents for the treatment of acquired cardiovascular disease. In addition to vascular remodeling processes triggered by indices of WSS[9], local velocity jets and accompanying high TAWSS values imparted on the posterior wall due to a particular stent type may lead to tortuosity as seen in a rabbit model of CoA[22], or disturb the cushioning function of the thoracic aorta by increasing stiffness[25]. However, these hypotheses remain to be tested in a follow-up study.

While there are many publications quantifying outcomes from stenting as compared to surgery or balloon angioplasty, most of these studies have grouped outcomes from several stents together thereby resulting in a paucity of data comparing one stent type to another for metrics beyond stent fracture. To our knowledge, this is the first investigation to incorporate realistic stent geometries into an entire thoracic aortic CFD model in order to quantify the impact of stent design on local hemodynamic alterations. While previous CFD studies involving stenting of the thoracic aorta provided invaluable information, they often included limitations such as omitting detailed geometric intricacies of a stent, used models restricted to the stented region, or did not include analysis of downstream hemodynamic alterations. The current investigation strongly suggests these downstream hemodynamic alterations unique to a given stent may be an important factor contributing to mechanical stimuli, and likely influencing vascular remodeling or plaque formation, after treatment for CoA.

The current results also extend the body of literature using CFD to study treatments for CoA by quantifying TAWSS alterations due to stent design. Previously Coogan et al. used a patient-specific CFD model of the thoracic aorta to study compliance mismatch created by making a portion of the dAo rigid, which had only a modest impact on cardiac work and BP[1]. The current results can also be appreciated relative to those from CFD models of untreated (i.e. native) CoA patients and those corrected by end-to-end or end-to-side repair that used equivalent CFD methods[17]. The range of TAWSS in the dAo here are below the values observed with untreated patients in the prior study (1,777–6,000 dyn/cm2), but were still more severe than those observed with surgically corrected or normal patients in the prior study.

The current study should be interpreted relative to other sources of morbidity in CoA, such as hypertension, and with the constraints of several potential limitations. The strut cross section of the virtually implanted NumedCP was rectangular, rather than circular, due to restrictions with the virtual stenting process. The use of a NumedCP stent with circular struts would likely decrease the severity of downstream hemodynamic alterations shown here. Future studies will strive to incorporate this realism. The prolapse of tissue into intrastrut regions was not considered here since the main focus was to quantify hemodynamic alterations downstream of the stented region and isolate the impact of different stent designs. Nevertheless, this factor should also be considered in future studies, perhaps using the approach Murphy el al. applied in CFD models of a stented coronary artery[24].

Results presented correspond to the acute period after stenting. Prior studies linking WSS distributions with future plaque locations suggest the distributions created by a given stent during the acute period are important as they establish the severity of mechanical stimuli for potential cellular proliferation. Nonetheless, these distributions of WSS will change over time so future studies are necessary to characterize chronic WSS distributions occurring in response to geometric changes from neointimal or somatic growth.

Detailed patterns of TAWSS shown here were influenced by stent type, are also largely dictated by vessel morphology and flow distributions to the head and neck arteries. For example, the presence of elevated TAWSS in the proximal stented region was a function of patient arch morphology and may not have been present in a patient with a gothic or crenel arch[26]. The current results would likely be altered by different arch morphologies, surgical corrections or other stent types. By applying knowledge gained from prior studies it may be possible to use the current techniques to predict outcomes for a variety of interventions. Future work should be conducted with patients undergoing treatment of CoA using different stents before CFD results are used to recommend a specific stent for a given patient. The current investigation demonstrates that the type of stent implanted can influence TAWSS distributions, which may be further accentuated or mitigated depending on a given patient's aortic morphology.

CONCLUSION

In summary, the current study is the first to quantify downstream hemodynamic alterations due to stenting in CoA patients using patient-specific CFD models with virtually implanted stents. The current results showed marked differences in TAWSS patterns in the downstream dAo depending on the stent implanted. Following confirmation with future studies containing more patients, these findings may aid pediatric interventional cardiologists in determining which models to stock within the cath lab, selecting the most appropriate stent for each patient, elucidating favorable attributes for next-generation designs that optimize downstream flow disturbances, and reducing long-term morbidity following treatment for CoA by stenting.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge Charles Taylor PhD, Mary Draney PhD, Frandics Chan MD PhD, Stanton Perry MD, Nathan Wilson PhD, Laura Ellwein PhD and Timothy Gundert MS for technical assistance.

Sources of funding: This work was supported by a Dean’s Postdoctoral Fellowship, the Vera Moulton Wall Center for Pulmonary Vascular Disease at the Stanford University School of Medicine, the Alvin and Marion Birnschein Foundation, NIH grant R15HL096096-01, and NSF awards OCI-0923037 and CBET-0521602.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coogan JS, Chan FP, Taylor CA, Feinstein JA. Computational fluid dynamic simulations of aortic coarctation comparing the effects of surgical- and stent-based treatments on aortic compliance and ventricular workload. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;77(5):680–691. doi: 10.1002/ccd.22878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Draney MT, Alley MA, Tang BT, Wilson NM, Herfkens RJ, Taylor CA. Importance of 3D nonlinear gradient corrections for quantitative analysis of 3D MR angiographic data. Honolulu, HI: International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duraiswamy N, Schoephoerster RT, Moore JE., Jr Comparison of near-wall hemodynamic parameters in stented artery models. J Biomech Eng. 2009;131(6):061006. doi: 10.1115/1.3118764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ebeid MR. Balloon expandable stents for coarctation of the aorta: review of current status and technical considerations. Images Pediatr Cardiol. 2003;15:25–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferencz C, Rubin JD, McCarter RJ, Brenner JI, Neill CA, Perry LW, Hepner SI, Downing JW. Congenital heart disease: prevalence at livebirth. The Baltimore-Washington Infant Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1985;12(1):31–36. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Figueroa CA, Vignon-Clementel IE, Jansen KE, Hughes TJR, Taylor CA. A coupled momentum method for modeling blood flow in three-dimensional deformable arteries. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2006;195:5685–5706. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forbes TJ, Rodriguez-Cruz E, Amin Z, Benson LN, Fagan TE, Hellenbrand WE, Latson LA, Moore P, Mullins CE, Vincent JA. The Genesis stent: A new low-profile stent for use in infants, children, and adults with congenital heart disease. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2003;59(3):406–414. doi: 10.1002/ccd.10547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frydrychowicz A, Stalder AF, Russe MF, Bock J, Bauer S, Harloff A, Berger A, Langer M, Hennig J, Markl M. Three-dimensional analysis of segmental wall shear stress in the aorta by flow-sensitive four-dimensional-MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;30(1):77–84. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibbons GH, Dzau VJ. The emerging concept of vascular remodeling. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(20):1431–1438. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199405193302008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gundert TJ, Shadden SC, Williams AR, Koo BK, Feinstein JA, Ladisa JF., Jr A rapid and computationally inexpensive method to virtually implant current and next-generation stents into subject-specific computational fluid dynamics models. Ann Biomed Eng. 2011;39(5):1423–1437. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-0238-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harrison DA, McLaughlin PR, Lazzam C, Connelly M, Benson LN. Endovascular stents in the management of coarctation of the aorta in the adolescent and adult: one year follow up. Heart. 2001;85:561–566. doi: 10.1136/heart.85.5.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hathcock JJ. Flow effects on coagulation and thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26(8):1729–1737. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000229658.76797.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics - 2005 Update. Dallas: American Heart Association; [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holme PA, Orvim U, Hamers MJ, Solum NO, Brosstad FR, Barstad RM, Sakariassen KS. Shear-induced platelet activation and platelet microparticle formation at blood flow conditions as in arteries with a severe stenosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17(4):646–653. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.4.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karino T, Goldsmith HL. Role of blood cell-wall interactions in thrombogenesis and atherogenesis: a microrheological study. Biorheology. 1984;21(4):587–601. doi: 10.3233/bir-1984-21417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LaDisa JF, Jr, Alberto Figueroa C, Vignon-Clementel IE, Kim HJ, Xiao N, Ellwein LM, Chan FP, Feinstein JA, Taylor CA. Computational simulations for aortic coarctation: representative results from a sampling of patients. J Biomech Eng. 2011;133(9):091008. doi: 10.1115/1.4004996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LaDisa JF, Jr, Figueroa CA, Vignon-Clementel IE, Kim HJ, Xiao N, Ellwein LM, Chan FP, Feinstein JA, Taylor CA. Computational simulations for aortic coarctation: representative results from a sampling of patients. J Biomech Eng. 2011;133(9):091008. doi: 10.1115/1.4004996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LaDisa JF, Jr, Olson LE, Guler I, Hettrick DA, Audi SH, Kersten JR, Warltier DC, Pagel PS. Stent design properties and deployment ratio influence indexes of wall shear stress: a three-dimensional computational fluid dynamics investigation within a normal artery. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:424–430. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01329.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LaDisa JF, Jr, Olson LE, Molthen RC, Hettrick DA, Pratt PF, Hardel MD, Kersten JR, Warltier DC, Pagel PS. Alterations in wall shear stress predict sites of neointimal hyperplasia after stent implantation in rabbit iliac arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288(5):H2465–H2475. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01107.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Les AS, Shadden SC, Figueroa CA, Park JM, Tedesco MM, Herfkens RJ, Dalman RL, Taylor CA. Quantification of hemodynamics in abdominal aortic aneurysms during rest and exercise using magnetic resonance imaging and computational fluid dynamics. Ann Biomed Eng. 2010;38(4):1288–1313. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-9949-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magee AG, Brzezinska-Rajszys G, Qureshi SA, Rosenthal E, Zubrzycka M, Ksiazyk J, Tynan M. Stent implantation for aortic coarctation and recoarctation. Heart. 1999;82:600–606. doi: 10.1136/hrt.82.5.600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Menon A, Eddinger TJ, Wang H, Wendell DC, Toth JM, Ladisa JF., Jr Altered hemodynamics, endothelial function, and protein expression occur with aortic coarctation and persist after repair. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;303(11):H1304–H1318. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00420.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muller J, Sahni O, Li X, Jansen KE, Shephard MS, Taylor CA. Anisotropic adaptive finite element method for modeling blood flow. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin. 2005;8(5):295–305. doi: 10.1080/10255840500264742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy JB, Boyle FJ. A full-range, multi-variable, CFD-based methodology to identify abnormal near-wall hemodynamics in a stented coronary artery. Biorheology. 2010;47(2):117–132. doi: 10.3233/BIR-2010-0568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Rourke MF, Cartmill TB. Influence of aortic coarctation on pulsatile hemodynamics in the proximal aorta. Circulation. 1971;44(2):281–292. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.44.2.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ou P, Bonnet D, Auriacombe L, Pedroni E, Balleux F, Sidi D, Mousseaux E. Late systemic hypertension and aortic arch geometry after successful repair of coarctation of the aorta. Eur Heart J. 2004;25(20):1853–1859. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perloff JK. Clinical recognition of congenital heart disease. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2003. Coarctation of the aorta; pp. 113–143. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Redington AN, Hayes AM, Ho SY. Transcatheter stent implantation to treat aortic coarctation in infancy. Br Heart J. 1993;69:80–82. doi: 10.1136/hrt.69.1.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sahni O, Muller J, Jansen KE, Shephard MS, Taylor CA. Efficient anisotropic adaptive discretization of the cardiovascular system. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin. 2006;195:5634–5655. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shim D, Lloyd TR, Moorehead CP, Bove EL, Mosca RS, Beekman RHr. Comparison of hospital charges for balloon angioplasty and surgical repair in children with native coarctation of the aorta. American Journal of Cardiology. 1997;79(8):1143–1146. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vignon-Clementel IE, Figueroa CA, Jansen KE, Taylor CA. Outflow boundary conditions for 3D simulations of non-periodic blood flow and pressure fields in deformable arteries. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin. 2010;13(5):625–640. doi: 10.1080/10255840903413565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vignon-Clementel IE, Figueroa CA, Jansen KE, Taylor CA. Outflow boundary conditions for three-dimensional finite element modeling of blood flow and pressure in arteries. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2006;195:3776–3796. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wendell DC, Samyn MM, Cava JR, Ellwein LM, Krolikowski MM, Gandy KL, Pelech AN, Shadden SC, LaDisa JF., Jr Including aortic valve morphology in computational fluid dynamics simulations: initial findings and application to aortic coarctation. Med Eng Phys. 2013;35(6):723–735. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2012.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wentzel JJ, Corti R, Fayad ZA, Wisdom P, Macaluso F, Winkelman MO, Fuster V, Badimon JJ. Does shear stress modulate both plaque progression and regression in the thoracic aorta? Human study using serial magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(6):846–854. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wentzel JJ, Whelan DM, van der Giessen WJ, van Beusekom HM, Andhyiswara I, Serruys PW, Slager CJ, Krams R. Coronary stent implantation changes 3-D vessel geometry and 3-D shear stress distribution. Journal of Biomechanics. 2000;33(10):1287–1295. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(00)00066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson N, Wang K, Dutton R, Taylor CA. A software framework for creating patient specific geometric models from medical imaging data for simulation based medical planning of vascular surgery. Lect Notes Comput Sci. 2001;2208:449–456. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zarins CK, Giddens DP, Bharadvaj BK, Sottiurai VS, Mabon RF, Glagov S. Carotid bifurcation atherosclerosis. Quantitative correlation of plaque localization with flow velocity profiles and wall shear stress. Circ Res. 1983;53(4):502–514. doi: 10.1161/01.res.53.4.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.