Abstract

Basic communication research has identified a major social problem: communicating about cancer from diagnosis through death of a loved one. Over the past decade, an award winning investigation into how family members talk through cancer on the telephone, based on a corpus of 61 phone calls over a period of 13 months, has been transformed into a theatrical production entitled The Cancer Play. All dialogue in the play is drawn from naturally occurring (transcribed) interactions between family members as they navigate their way through the trials, tribulations, hopes, and triumphs of a cancer journey. This dramatic performance explicitly acknowledges the power of the arts as an exceptional learning tool for extending empirical research, exploring ordinary family life, and exposing the often taken-for-granted conceptions of health and illness. In this study, a Phase I STTR project funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), we assess the feasibility of educating and impacting cancer patients, family members, and medical professionals who viewed the play as a live performance and through DVD screenings. Pre-and post-performance questionnaires were administered to solicit audience feedback. Pre-post change scores demonstrate overwhelming and positive impacts for changing opinions about the perceived importance, and attributed significance, of family communication in the midst of cancer. Paired-sample t-tests were conducted on 5 factor analyzed indices/indicators – two indices of opinions about cancer and family communication, two indices measuring the importance of key communication activities, and the self-efficacy indicator – and all factors improved significantly (<.001). Informal talkback sessions were also held following the viewings, and selected audience members participated in focus groups. Talkback and focus group sessions generated equally strong, support responses. Implications of the Phase I study are being applied in Phase II, a currently funded effort to disseminate the play nationally and to more rigorously test its impact on diverse audiences. Future directions for advancing research, education, and training across diverse academic and health care professions are discussed.

A fundamental priority of health communication is to better understand and minimize cancer burdens for patients, family members, and health care professionals. Organizations such as the National Cancer Institute (NCI, 2013), American Cancer Society (ACS, 2013), and Livestrong Foundation (2013) devote considerable resources to improving the lives of those adversely affected by cancer. Such organizations encourage creative initiatives to identify the psychosocial experiences and impacts of cancer, how communication gets employed to manage relationships throughout cancer journeys, and to advance interventions designed to reduce suffering, provide social support, promote healing outcomes, and enhance quality of living.

We address these concerns by reporting preliminary findings from a project entitled Conversations about Cancer (CAC), an educational intervention focusing on the critical importance of communication when navigating the trials, tribulations, hopes, and triumphs of a cancer journey. The CAC project includes a theatrical production (viewed live or via DVD recording), measures of the play’s impact on audiences using quantitative and qualitative evaluations, and the development of self-sustaining strategies for the distribution of the play to large, diverse audiences. The core intervention is a unique theatrical production created to convey important educational messages about how cancer patients and family members face a cancer diagnosis and come to grips with the impending death of a loved one. With The Cancer Play, we harness the exceptional power of the arts as an innovative learning tool for extending empirical research, exploring ordinary family life, and exposing often taken-for-granted conceptions of cancer, health, and illness. By integrating education and entertainment (see Beach et al., 2012; Duque et al., 2008; Harris et al., 2009; Learning Center, 2006; Sherman & Simonton, 2001; Slater, 2002), we developed a resource for promoting meaningful dialogue about delicate, complex, and frequently misunderstood communication challenges arising from a longitudinal examination of cancer diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis.

What follows are 1) a synopsis of health communication challenges when managing cancer, 2) a brief description of CAC’s background and development, 3) findings from a Phase I feasibility study involving audience reactions to live performances and DVD screenings of The Cancer Play, 4) ongoing efforts to design and implement a national effectiveness trial, and 5) future implications and applications of the CAC program for advancing research, education, and training across diverse academic and health care professions.

Health Communication and the Challenging Impacts of Cancer

Communicating about cancer is a major social problem in contemporary society. Cancer is the most ubiquitous disease in the world and the second leading cause of death in America (ACS, 2013). As three out of four U.S. families are affected by cancer at some time (ACS, 2007; Lichtman & Taylor, 1986; O'Hare, Kreps, & Sparks, 2007), the critical importance of communication for managing cancer diagnosis, treatment, and care is indispu`. Phone calls, particularly with the unprecedented growth of cell phones, are a primary means for coordinating daily cancer communication nationwide in home, work, and clinical environments (Beach, 2009; Kreps & Kunimoto, 1994). The sheer number of such calls indicates that families use the telephone for conversations that explain, inform, and commiserate about the impact of cancer on health and well-being.

The stress caused by the intrusion of a potentially threatening disease is compounded by related challenges such as altered physical appearances, lifestyle changes, reduction in quality of living, care giving burdens, and financial hardships (Gotay, 1984; Heinrich, Schag, & Ganz, 1984; Hinton, 1998). These challenges have been associated with significant, difficult, and often dysfunctional changes in social relationships (Leiber et al., 1976; Hilton, 1994; Watson, 1994). The majority of cancer patients report moderate to severe problems in family relationships (Calman, 1987; Leiber et al., 1976; Gotcher, 1995; Shields, 1984; Watson, 1994). Long term survival of families are threatened (Gotcher, 1993; Hess & Soldo, 1985; Litman, 1974; Rait & Lederberg, 1990) when traditional communication patterns get violated and disrupted by activities such as attempting to balance care giving tasks; new and alternative “jobs” within the family system; and expressing anger, frustration, and hopefulness (e.g., see Bunston et al., 1995; Farrow, Cash, & Simmons, 1990; Friedmann & DiMatteo, 1982; Hilton, 1994; Keller et al., 1996; Mireault & Compas, 1996). The offering and withholding of psychosocial support, and ability to adjust to altered circumstances due to cancer, also strongly influences family relationships and how stress gets managed (Leiber et al., 1976; Shields, 1984; Wortman & Dunkel-Schetter, 1979). Family members who communicate psychosocial support promote more enduring family relationships, function as more effective caregivers, and experience less stress. Research has also suggested that open, honest, and frequent communication is essential for ensuring that wishes of patients and family members are heard, and attended to, when deciding on care options, working through the anguish and uncertainty of cancer, and seeking “positive rehabilitation outcomes.” (Mesters et al., 1997; Montazeri et al., 1996; Rowland, 1990). Communication is thus fundamental for quality of life, level of adjustment to cancer, social support, and long-term survival of the family unit.

Addressing the health communication challenges of family cancer requires moving away from isolating patients’ cancer experiences to situated conduct within family interactions. One depiction, “A family…a phone call…a diagnosis…one family’s journey through cancer” (Beach, 2009), emphasized how cancer care impacted family members and the sharing of ongoing burdens (Addington-Hall & McCarthy, 1995; Seaburn et al., 1996). Yet psychosocial and cancer survivor investigations focus predominantly on individual experiences (Beach & Andersen, 2003), including reports of how family members perceive helping each other cope (Broccolo, 1997), experiences of living with a cancer patient (Hensel, 1997), suffering from deaths of loved ones (Brooks, 1997; Byock, 1997; Spears, 1990), providing care by nurses (Joseph, 1992; Parisi, 1996), and a variety of family survival guides for coping with cancer (Hermann et al., 1988; Kowalczyk, 1995; Renz, 1994). Prior research has not directly studied family cancer communication interactionally, and access to actual recordings and transcriptions has been minimal. This dearth of prior research creates a special need and unique opportunities to closely examine and better understand how cancer triggers communication challenges, as well as how family members (and cancer patients) use communication to minimize such difficulties by socially constructing support, hope, and wellness (e.g., see Beach, in press; 2013; 2012; Beach et al., in press; 2012).

By integrating theatrical performances and innovative productions, including talkback sessions, CAC helps disseminate and popularize the findings of basic communication research on family interactions. Distinct communication challenges, occurring in the midst of cancer, are consequential and can be directly addressed with CAC and its supporting materials. The program has enormous potential to positively impact the lives of the nearly 12 million people living with cancer (ACS, 2013), as well as their family members, friends, coworkers, and health care providers.

CAC’s Background And Development

In 1998, a San Diego family donated a corpus of recorded phone calls (61 over a period of 13 months) among family members as they communicated about the diagnosis, treatment, and eventual death of a mother/wife/sister throughout their shared cancer.1 This generous donation of the audio recordings was motivated by two primary hopes. First, the family hoped to advance scientific understandings of how everyday conversations about cancer get accomplished. Over a decade of analysis, this culminated in A Natural History of Family Cancer: Interactional Resources for Managing Illness (Beach, 2009).2 The book (referenced as NH throughout this article) reported important findings about primary social activities such as delivering and receiving bad and good news, managing lives in times of uncertainty and crises, reporting on and assessing medical care, commiserating and being hopeful about the future. In the social sciences, these recordings comprise the first natural history of family telephone conversations focusing primarily on monitoring and coping with a loved one’s cancer.

Second, the family also hoped that these research findings might assist other patients, families, and medical experts as they communicate throughout cancer journeys. The CAC production addresses these educational priorities by extending basic research findings into a creative theatrical production.

Everyday life performances (ELP’s) are stage productions where conversation analytic (CA) transcriptions of real conversations are adapted into play scripts to increase understandings and enhance education about communication (e.g., see Stucky, 1993, 1998; Stucky & Glenn, 1993; Hopper, 1993; Gray & Van Oosting, 1996). The play utilized only naturally occurring dialogue from these phone conversations between family members. Seventy minutes in length (edited from more than 7 hours of conversations), the CAC projects adapts key findings from NH to vividly demonstrate primary communication patterns enacted by family members as they talk about and through cancer on the telephone. Actual family phone conversations about cancer have never been studied in such detail, from the onset of diagnosis through the activities involved as the mother’s condition becomes terminal.

No such materials have been artistically adapted to theatre. Live performances and DVD screenings offer more realistic access to everyday life events than do role-playing and other hypothetical scenarios. Watching the play triggers practical and illuminating discussions about the experiences and impacts of cancer. These occasions also provide unique opportunities to assess impacts on audiences and to identify primary communication challenges and practices for managing cancer journeys. Assessments of audience reactions (described below) are grounded in research findings about the interactional organization of these phone calls.

Phases and Research Activities for CAC Development

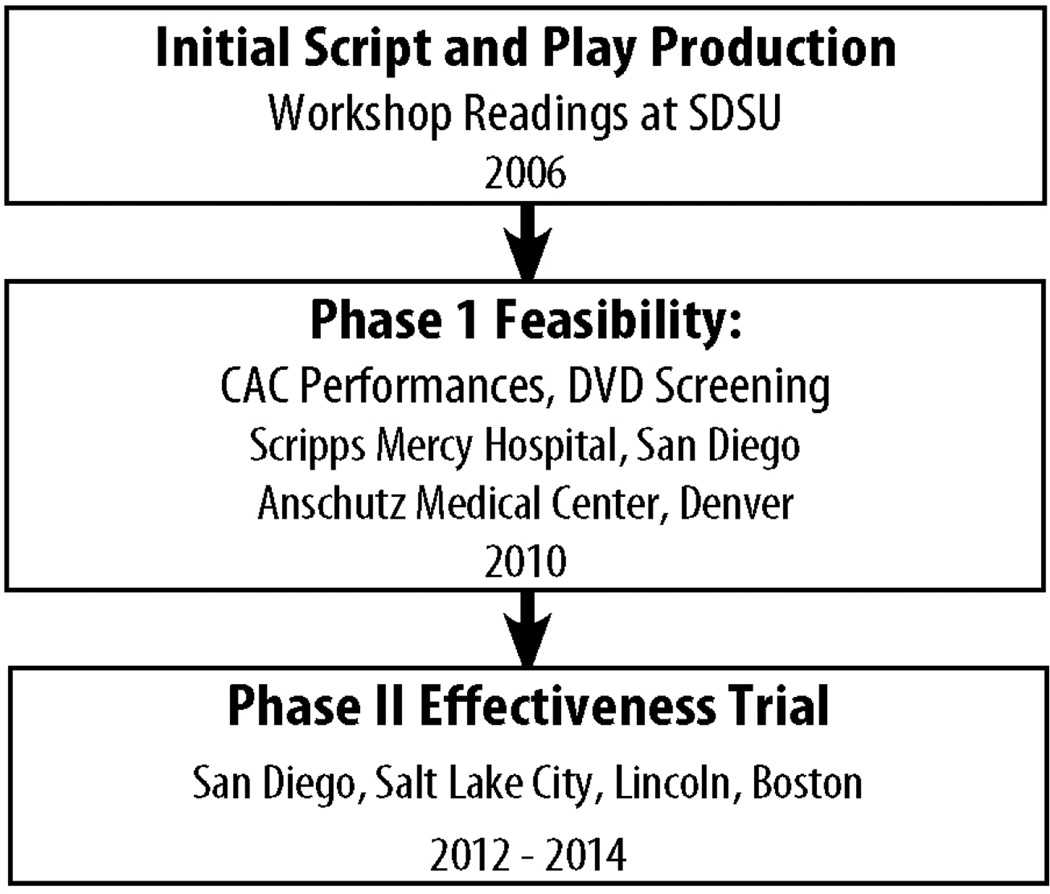

The three phases of CAC development are summarized in Figure 2. In 2006, 6 initial workshop readings and 5 experimental stage productions solicited strong and encouraging feedback from approximately 1000 San Diego community members. The Phase I project was conducted between June 2010 and August 2011. Key activities included revising the script; hiring professional actors, theatre experts, and videographers; creating reliable and valid quantitative assessment measures; conducting talkback sessions; and moderating focus groups. The Phase II effectiveness trial, currently underway, is elaborated in the conclusion of this article.

Figure 2.

Three Phases of CAC Development

To summarize, the CAC project and The Cancer Play are significant and innovative new tools designed to help patients, family members, significant others, and medical experts navigate their way through changing cancer circumstances. High-quality family communication about cancer encompasses close attention to maintaining family relationships, creative decision-making, and the ability to resolve communication and medical problems. The focus on talk among family members, rather than individual cancer patients in isolation, is an appropriate unit of analysis when seeking to understand cancer journeys because patients and family members typically experience the diagnosis, treatment, and resolution of cancer together. The CAC project exemplifies an alternative, viable theatrical genre grounded in authentic, naturally occurring phone conversations. By relying on both live performances and DVD screenings, CAC extends established theoretical frameworks for creating educational messages, triggers meaningful conversations about otherwise inaccessible communication events, uses mixed methods to solicit and analyze audience feedback, and measures impact on cancer patients and family members (see Beach et al., 2012; in press).

Methodology: Developing Measures and Recruiting Audiences

An interdisciplinary team of health communication researchers and theatre professionals has been formed in partnership with Klein Buendel, Inc. (KB), a small research firm specializing in developing, evaluating and disseminating health communication programs. The team developed an Expert Advisory Panel (EAP) consisting of a medical oncologist, surgeon, registered nurse practitioner and breast cancer navigator, theatre professional, cancer survivors, an expert on diversity, identity, and communication, an Associate Dean of liberal arts and sciences, and an academic Dean overseeing professional studies and fine arts. The team also created tools to assess the efficacy of The Cancer Play to impact audience members.

Instrumentation

Quantitative measures were derived primarily from the large corpus of telephone conversations and the findings in NH, following an inductive, grounded theoretic approach. This permitted the measures to “capture the original meaning validly, yet explicate them on a level that gives the results maximum impact” (Christians & Carey, 1989, p. 370). When linkages were noted between the inductive measures from the NH conversations and findings and the extant psychosocial research on communication and family cancer journeys, additional items were added. This rigorous abductive process yielded a total of 15 opinion items and 10 additional items measuring key communication activities in families dealing with cancer. A 9-point Likert-type scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (9) was used to measure opinion items. The midpoint (5) indicated a “neutral/unsure” evaluation. A 9-point scale was used to rate the importance of communication activities, from “not important” (1) to “extremely important” (9). The midpoint (5) indicated “average importance.” The distinction between opinions about the cancer journey and communication activities is both conceptual and operational. Conceptually, the grounded opinion measures seek to capture valences toward certain perceptions of a family’s cancer journey. Operationally, they utilize easy-to-understand agree/disagree measures. Conceptually, certain communication activities might seem unimportant in the context of everyday family life. Cancer, however, imposes a “new normal” on the family in the play. Inductively, the research team wondered if the importance of these communication activities might shift as a function of exposure to the play. Operationally, this suggested the use of the scale described above.

The team reviewed the questionnaires and pilot tested the instrumentation informally for clarity and appropriate vocabulary. The EAP also evaluated the questionnaires. Later, the EAP provided feedback on emerging study findings and future possibilities for CAC application and dissemination.

Recruitment and Data Collection

Cancer patients, family members of cancer patients, and healthcare providers were recruited in the San Diego and Denver areas. Participants completed IRB-approved consent forms and filled out self-administered questionnaires before and after viewing 3 live performances (San Diego) and 4 DVD screenings (Denver) of The Cancer Play. Sample size was 204. Audience size averaged 51 (range: 32–65). Among viewers, 31% were cancer patients/survivors, 57% were members of families with cancer patients, and 12% were cancer-related healthcare providers. Data were collected using a self-administered questionnaire immediately prior to and after exposure to the play.

Findings: Assessing Audience Impacts and Demonstrating Feasibility

The feasibility for the CAC project was amply demonstrated. Responses to the quantitative measures were collapsed into “disagree” (1–4), “neutral” (5), and “agree” (6–9). Following the performances and screenings, 91% of respondents agreed CAC provided an authentic portrayal of a family’s journey with cancer, 89% agreed the play held their interest from beginning to end, 89% considered CAC appropriate for “people like me,” 85% said CAC would influence people like them, and 74% indicated that CAC was uplifting and inspiring. Only 10% considered CAC “too depressing,” despite the impending death of the cancer patient in the play (which occurred shortly after the last of 61 phone calls; the actual death was not portrayed in the play).

From pre-test to post-test, agreement increased significantly for 14 of 15 opinions about cancer, family, and communication (1-tailed paired sample t-test for repeated measures, alpha=.05). From pre-test to post-test, the importance of 7 of 10 key communication activities also increased significantly.

Primary Factors Across 15 Opinion Items

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) is often misused in communication research (see Morrison, 2009, for a systematic review); however, in the present study, it is entirely appropriate, given the inductive approach to instrumentation development. This research ‘explores’ the “dimensionality of item responses” (p. 201). Researchers held few or no a priori assumptions about the number and nature of latent variables. Thus, the factors from the present study are offered as empirically grounded hypotheses about latent variables at play when family members communicate about the cancer of a loved one.

The 15 opinion items were subjected to exploratory factor analysis (principal component extraction rotated to Varimax solution) and yielded 3 factors.

The 6 items on Factor 1 emphasized communication that helps maintain the fabric of family life while dealing with cancer. Items included opinions such as “I understand how topics like cars, dogs, and food are important resources for families,” “When families deal with cancer, they should seek to balance the serious with the funny,” and “Activities like playing together, teasing, and humor are basic tools for dealing with cancer.” Cronbach’s alpha for the Family Fabric index (based on pre/post measures) was .75.

The 5 items on Factor 2 emphasized opinions about family communication, including “Open communication about cancer in the family strengthens the family bond,” “Talking about cancer helps family members guide each other in giving better emotional care,” and “Talking about cancer helps family members reduce their uncertainty.” Cronbach’s alpha for the Family Communication index was .81.

The 4 items on Factor 3 included a self-efficacy item related to cancer and communication: “I am sure I can talk with my family about a family member’s cancer.” Cronbach’s alpha for the Communication Efficacy index was .66.

Primary Factors Across 10 Communication Support Activities

The 10 items measuring the importance of key communication support activities were also subjected to factor analysis and yielded 2 factors.

Factor 1 consisted of 7 items emphasizing the importance of emotional support. These included the importance of “The role of emotional support from the family,” “The role of commiseration,” “The role of compassion,” and “The role of family members as caregivers to the patient.” Cronbach’s alpha for the Emotional Support index was .87.

Factor 2 consisted of 3 items that emphasized the importance of communication and support of those outside the nuclear family. Items included the importance of “Talking to others outside the family about the cancer journey,” “Talking to other (non-nuclear) family members about their journey with cancer,” and “The role of communication in managing cancer.” Cronbach’s alpha for the Outsider Communication index was .74.

Impact of The Cancer Play on Audiences

Paired-sample t-tests for the pre-test and post-test measures repeated within respondent were conducted on the 5 indices derived from the factor analysis to determine if these measures of CAC impact had improved significantly after viewing The Cancer Play. Table 3 (below) unequivocally shows that the 3 indices of opinions about cancer and family communication, and the 2 indices measuring the importance of key communication support activities, improved significantly.

Table 3.

Changes in Opinions and Perceived Importance of Support Activities

| Before Viewing | After Viewing | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opinion Indices | Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | t-test | d.f | Sig. |

| Family Fabric | 7.53 | 0.95 | 8.14 | 0.83 | 10.11 | 194 | <.001 |

| Family Comm. | 7.81 | 0.90 | 8.19 | 0.82 | 6.72 | 191 | <.001 |

| Comm. Efficacy | 7.81 | 1.59 | 8.23 | 1.15 | 4.32 | 201 | <.001 |

| Support Indices | |||||||

| Emotional Support | 8.13 | 0.88 | 8.40 | 0.68 | 5.86 | 191 | <.001 |

| Outsider Comm. | 7.93 | 0.90 | 8.29 | 0.81 | 6.12 | 196 | <.001 |

Further, for 4 of the 5 indices, The Cancer Play’s impact did not differ significantly between the live performances (San Diego) and DVD screening (Denver). The only exception was that increases in the perceived importance of the Emotional Support index were greater after the DVD showings than after the live performances. This seems counterintuitive, since one might postulate that a live performance before a live audience would have greater impact than a video recording and viewing of the same performance. However, this finding and the more general lack of differences between live performance and DVD screening suggest there are great opportunities for mediated distribution of The Cancer Play at a fraction of the cost of multiple live performances.

Impact did not differ for cancer patients, family members, and healthcare providers. Change scores were computed for the 5 indices. One-way ANOVA was used to test differences between cancer patients, family members, and healthcare providers. None of the differences was statistically significant (alpha>.05).

In addition to quantitative measures of CAC impact, 7 focus groups were conducted after the live performances and the DVD screenings (n=55). Focus groups were stratified by cancer patients, family members, nurses, cancer support professionals (2 groups), physicians, and theater professionals.

Content analyses of focus group discussions are reported elsewhere (see Moran et al, 2012). However, comments offered by focus group participants were overwhelmingly positive. Focus groups provided useful suggestions for appropriate venues for CAC and technical recommendations for improving the production of The Cancer Play.

One emergent theme among healthcare professionals was the concern that the family in the play is white, and people of color and from different cultural backgrounds might not relate to the cancer journey of a white, middle-class family. However, cancer patients in the focus group who were not white did not raise this concern. Quantitatively, when compared to white audience members, CAC had the same positive impact on people of color across all 5 indices. One-way ANOVA of change scores between whites and people of color showed no significant differences (alpha>.05).

After reviewing the data, the EAP unanimously confirmed the feasibility and value of the CAC program, as determined by quantitative pre/post measures of opinion change and the importance of communication activities. These findings are reflected in the high level of audience participation in the talkback sessions and comments extracted from post-performance focus group studies among cancer patients, family members, and healthcare professionals.

To summarize, the major activities of a Phase I assessment of CAC feasibility provided compelling evidence that 1) an Expert Advisory Panel (EAP) can be drawn from various areas of expertise and provide valuable guidance to the research team; 2) a compelling script, grounded in a large corpus of phone call materials, can be directly and effectively adapted to a theatrical production; 3) valid and reliable quantitative measures can be developed to measure the impact of The Cancer Play on audience members regarding cancer, communication, and the family; 4) those quantitative measures provide strong and compelling evidence of significant impact of CAC on cancer patients, family members, and healthcare providers; 5) live performances and DVD screenings are equally impactful for diverse audiences, creating unique and powerful opportunities for discussing both individual experiences and family cancer communication; and 6) additional evidence in the form of focus group and talkback session discussions further corroborate the overall positive impact of viewing The Cancer Play.

Discussion: Implementing a National Effectiveness Trial

The research team is currently refining and extending the CAC project to a national effectiveness trial. Researchers will recruit and assess the impacts of The Cancer Play on larger and more diverse audiences. Based on feedback and findings from Phase I, the play script and pre-post quantitative measures are being further refined. Professional actors and theatre experts continue to fine-tune the production. We are exploring the use of alternative theatre venues. Team members are investigating innovative videography techniques for capturing and editing live performances for DVD screenings.

The team also is developing and implementing a comprehensive website for Phase II. The website will provide an online, interactive portal for accessing CAC tools and materials (e.g., script, DVD, director’s notes, talkback questions, resources for improving communication about cancer) and executing CAC across diverse local environments. The current prototype website has eight sections, five interactive tools, social media links, and password-protected sections for future subscribers/licensees. For consistency, recognition, and branding, the website has a graphically designed look-and-feel to match A Natural History of Family Cancer. The EAP reviewed the prototype website, offered constructive suggestions, and determined that its design and content structure were appropriately targeted, attractive, complete, credible, and easy to navigate. A professional multimedia team will fully develop the website, resource materials, and tools in Phase II.

Multi-Site University and Community Collaborations

The basic model for a national effectiveness trial is anchored in multi-disciplinary collaborations across university/college, community institutions and urban/rural cancer networks, theatre troupes, and experts in professional stage productions. As summarized below, the sites for audience viewings will be San Diego, Salt Lake City, Lincoln, and Boston:

| San Diego | Salt Lake City |

| San Diego State University | University of Utah |

| Moores UCSD Cancer Center | Huntsman Cancer Institute |

| Scripps Cancer Center (Mercy) | College of Nursing |

| American Cancer Society | American Cancer Society |

| Lincoln | Boston |

| University of Nebraska | Emerson College |

| Eppley Cancer Institute/Omaha | Massachusetts General |

| St. Elizabeth Cancer Center | Hospital Cancer Center |

| American Cancer Society | American Cancer Society |

In each of the four cities, faculty members from departments/schools of communication and a school of dentistry will coordinate play activities in unison with major cancer centers and a college of nursing at specific locations. Several national and community-based cancer organizations, including branches of the American Cancer Society, will also assist with audience recruitment through promotional materials, using newspapers, community network flyers, cancer center venues, and varied online mechanisms.

To test the effect of CAC on family communication about cancer, the research team will utilize a group-randomized, pretest-posttest controlled design. Audience members include cancer patients and family members. Adults will be recruited to 1 of 8 DVD screenings, two in each city/site (one intervention and one control screening that will utilize a video about cancer that does not focus on family communication). There will be 300 participants in each city (N=1,200), and another 480 participants will receive 1-month follow-up online surveys to assess continued impacts of The Cancer Play. Results from this effectiveness trial will be provided in subsequent publications.

Discussion: Implications and Applications Of CAC

The CAC program exemplifies the potential transformation of basic communication research into a national program capable of impacting large and diverse audiences. The continuing development of the CAC project creates theatrical, educational, and community-based applications that advance understandings about the primary importance of communication throughout family cancer journeys.

The Cancer Play can be adapted to a wide variety of live stage theatrical programs focusing on cancer patients and survivors, family members, friends, and/or the medical community. Whether the forum involves professional stage productions, community theatre, or high school productions, change agents increasingly use theatre as an educational tool for a wide range of topics (Novak-Leonard & Brown, 2008). New approaches have transformed theater by supplementing traditional stage settings with new venues such as community meeting places, alternative schools, prisons, and nursing homes. Producers can adapt The Cancer Play to alternative venues based on the needs of audiences or application of its use. For example, the production could be staged in hospital auditoriums. The three live San Diego performances for the Phase I study were held in West Auditorium at Scripps Mercy Hospital.

The use of theatre in health care settings is an emerging phenomenon that weds art with science to re-shape the way we think about medicine and the healing potential of the arts (Brodzinkski, 2010). One useful illustration is Kaiser Permanente’s Educational Theatre Programs (2011), designed to inspire children, teens, and adults across the country to make informed decisions about their health and to build stronger, healthier neighborhoods. Recent plays, or plays-turned-movies, have successfully combined theatrical arts with health or social-issue advocacy and education. Numerous popular theatrical productions have paved the way for CAC. Consider five examples: Next to Normal is a rock musical about a mother who struggles with worsening bipolar disorder and the effect her illness has on her family. Next to Normal toured the country and opened on Broadway in 2009, winning 3 Tony Awards. When performed in Denver in 2011, the play was accompanied by a day of workshops and sessions (open to the public) on mental health issues; The Laramie Project premiered in Denver in 2000 and has since performed around the world. The play tells the story of Matthew Shepard, a victim of violence, hate crime, and homophobia. The Laramie Project has evolved into a social movement to teach about prejudice and tolerance, inspiring multiple grassroots initiatives; The Theater of War (2012) project uses live readings and discussions of Sophocles’ ancient plays to raise awareness and reduce the stigma of post-deployment psychological injury. Over 40,000 military and civilians in the US, Europe, and Japan have viewed the play in contexts ranging from the Pentagon to homeless shelters; The Vagina Monologues, which premiered in 1996, is a theatrical production that discusses the un-mentionable parts of the female body and experience and combats violence against women. The play has inspired a movement, “V-Day,” which has generated $75 million dollars to combat violence against women; and finally, Wit is an award-winning play and movie about a woman’s end-of-life experience with ovarian cancer. Since its premier in 1995, Wit won a Pulitzer Prize in 1999, was made into an Emmy Award-winning HBO movie in 2001, and has won awards on Broadway. UCLA turned Wit into a widely disseminated training program for medical school students with funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The CAC project can benefit higher education institutions that offer programs in health communication, medicine, nursing, counseling, social work, hospice care, psychology, psychiatry, and other allied disciplines that train professionals to provide health care to cancer patients, cancer survivors, and their family members and friends. In nearly every Phase I focus group, participants suggested that The Cancer Play could be a powerful tool to inform health care professionals (e.g., medical, nursing, counseling, and related health areas) about family cancer experiences. Pre-service and continuing education programs targeted to healthcare professionals could rely on CAC for obtaining continuing medical education units (CME’s). As an educational tool, CAC could also be integrated into medically based professional development packages that teach communication skills to medical, nursing and counseling students in the classroom as well as professional staff at conferences and workshops. Live performances or DVD screenings could also occur at medically based support group meetings, at hospices, in classrooms, at non-profit foundation events, or community-wide in churches and other organizations. Pharmaceutical companies and insurance companies are important stakeholders that may underwrite such uses of The Cancer Play.

The Medical Humanities are broadly defined as the incorporation of humanities and arts-based teaching materials into medical school and residency curricula (Shapiro & Rucker, 2003). Implemented by medical schools across the country, these Medical Humanities Programs include the use of art, literature, poetry, photography, film, history, theater, and philosophy to help medical students “better understand and empathize with their patients experiences; and ultimately treat their patients more humanely and effectively” (University of California-Irvine, 2012). For example, in the University of California-Irvine program, students participate in a readers’ theater performance of Wit, a play about a woman dying of ovarian cancer. Activities include writing a point-of-view poem from the perspective of a patient recently diagnosed, making a “parallel chart” recording all that they notice, imagine patient perspectives having no place in the formal patient chart, drawing a picture representing a difficult patient encounter, or reflecting on cultural differences in medicine through a narrative essay. From these and related programs, important characteristics of medical professionalism are enhanced as primary educational outcomes, including altruism, compassion, caring toward patients, and the development of communication and observational skills (Shapiro & Rucker, 2003; Doukas, McCullough, & Wear, 2010).

Through viewings and facilitated discussions following performances of The Cancer Play, each of these entities could enhance education and refine approaches for providing healthcare and/or support services to current cancer patients, survivors, and family members. The long-term vision of CAC project is to make The Cancer Play available to cancer patients, family members, health and theatre professionals in each of the 50 states. The play will also be integrated into a broad, innovative curricular program designed to trigger meaningful stories about communication and family cancer, to stimulate informative dialogue, and to provide grounded assistance about alternative approaches to organizing social interactions when faced with threatening health circumstances (cancer being only one primary example).

In closing, this study does have several limitations. First, in Phase I we did not measure behavioral changes in how families communicate about their cancer journey. Second, the study employed a one-group pretest-posttest design, which includes several threats to internal validity (Campbell & Stanley, 1963). And finally, generalizability was limited since subjects were recruited only from the San Diego and Denver areas. These limitations will be be addressed during Phase II of this investigation.

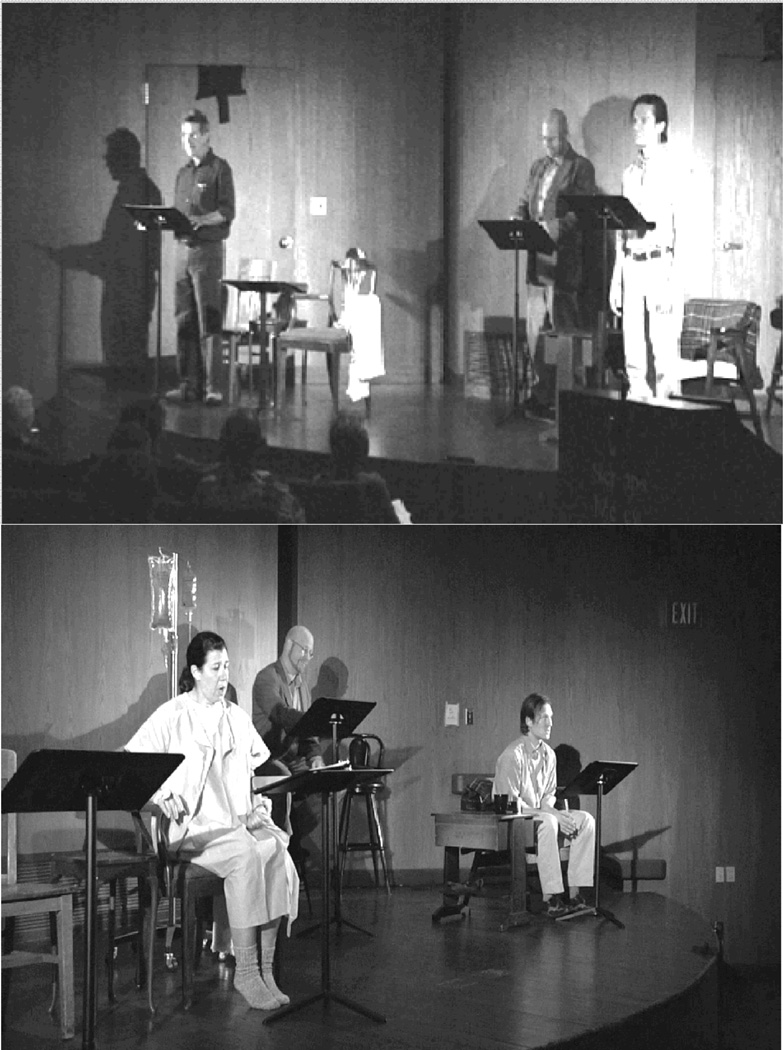

Figure 1.

Scenes from The Cancer Play

Table 1.

Factor Analysis of 15 Opinions About A Family’s Cancer Journey

| Opinion Items From “Disagree Strongly (1) to “Agree Strongly (9) |

1 Family Fabric Factor |

2 Family Comm. Factor |

3 Comm. Efficacy Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| I understand how topics like cars, dogs, and food are important resources for families as they talk about cancer. |

.80 | ||

| When family members deal with cancer, they should seek to balance the serious with the funny or humorous. |

.79 | .29 | |

| Activities like playing together, teasing, and humorous stories are basic tools for dealing with cancer. |

.69 | .31 | .25 |

| A new kind of “normal” emerges as cancer patients and their families adjust to different phases of diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. |

.62 | .37 | |

| Guessing and speculating about the possibility of death is a central topic when dealing with cancer. |

.55 | .33 | |

| Cancer changes one’s philosophy about living. | .44 | .43 | |

| Open communication in the family about cancer helps strengthen the family bond. |

.83 | ||

| Talking about cancer helps family members guide each other in giving better emotional care for each other. |

.83 | .21 | |

| Talking about cancer helps family members reduce their uncertainty about cancer. |

.72 | ||

| The power of ordinary communication should not be taken for granted. |

.57 | .24 | |

| In the end, hope eventually overcomes despair when a family expereinces cancer. |

.41 | .53 | |

| Delivering and receiving both good and bad news are important for family members dealing with cancer. |

.45 | .20 | .74 |

| I am sure I can talk with my family about a family member’s cancer. |

.29 | .72 | |

| Communication is critical for allowing joy to exist in the midst of suffering. |

.50 | .23 | .65 |

| When dealing with cancer, family members need to trust and rely on each other. |

.47 | .35 | .61 |

Table 2.

Factor Analysis of the Importance of Various Support Activities

| Importance Items From “Not Important” (1) to “Extremely Important” (9) |

1 Emotional Support Factor |

2 Outsider Support Factor |

|---|---|---|

| The role of emotional support from the family. | .78 | |

| The role of commiseration (being in the moment together, whether good or bad). |

.75 | .24 |

| The role of compassion. | .73 | |

| The role of family members as caregivers to the patient. | .70 | |

| The role of family members as caregivers to others beside the patient. | .54 | .40 |

| Regular news updates on the cancer patient’s condition. | .54 | .46 |

| The role of faith or spiritual beliefs. | .45 | |

| Talking to others outside the family about the journey with cancer. | .90 | |

| Talking to other family members about their journey with cancer. | .25 | .82 |

| The role of communication in managing cancer. | .47 | .61 |

Footnotes

This project was supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through, Grant CA144235.

As noted in A Natural History of Family Cancer, the authors gratefully acknowledge the anonymous family that graciously donated the corpus of recorded phone conversations that made the CAC project and The Cancer Play possible. The authors also gratefully acknowledge the work of Alane S. Lockwood, who initially explored the use of this corpus of recordings and transcriptions to develop a play script (Lockwood, 2002).

In 2010–2011 this book received two awards from the National Communication Association (NCA): The Outstanding Book Award from the Health Communication Division, and the Outstanding Scholarship Award from the Language and Social Interaction Division.

Contributor Information

Wayne A. Beach, Professor, School of Communication, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA 92182-4561, wbeach@mail.sdsu.edu Adjunct Professor, Department of Surgery, Member, Moores Cancer Center, University of California, San Diego.

Mary K. Buller, Klein Buendel, Inc

David M. Dozier, San Diego State University

David B. Buller, Klein Buendel, Inc

Kyle Gutzmer, San Diego State University

References

- Addington-Hall J, McCarthy M. Dying from cancer: results of a national population-based investigation. Palliative Medicine. 1994;9:295–305. doi: 10.1177/026921639500900404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. 2013 http//www.cancer.org.

- American Cancer Society. 2013 http://www.cancer.org/Research/CancerFactsFigures.

- American Cancer Society. California Cancer Facts and Figures; 2007. California Division and Public Health Institute, California Cancer Registry. [Google Scholar]

- Beach WA. A natural history of family cancer: Interactional resources for managing illness. Mahwah, NJ: Hampton Press, Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Beach WA. Managing hopeful moments: Initiating and responding to delicate concerns about illness and health. In: Hamilton HE, Chou WS, editors. Handbook of language and health communication. Routledge; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Beach WA. Patients’ efforts to justify wellness in a comprehensive cancer clinic. Health Communication. 2012;28:1–15. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2012.704544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach WA. Introduction: Raising and responding to concerns about life, illness, and disease. In: Beach W, editor. Handbook of patient-provider interactions: Raising and responding to concerns about life, illness, and disease. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press, Inc; 2013. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Beach WA, Andersen J. Communication and cancer: The noticeable absence of interactional research. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2003;21:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Beach WA, Gutzmer K, Dozier D, Buller MK, Buller D. Conversations about Cancer (CAC): A global strategy for accessing naturally occurring family interactions. In: Kim DK, Singhal A, Kreps G, editors. Global health communication strategies in the 21st century: Design, implementation, and evaluation. Peter Lange Publishing Group; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Beach WA, Buller M, Dozier D, Buller D, Gutzmer K. Edutainment and family communication: An intervention strategy for triggering conversations about cancer. 2012 Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom J. Social support of the cancer patient and the role of the family. In: Baider L, Cooper CL, Kaplan De-Nour A, editors. Cancer and the family. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 1996. pp. 53–70. [Google Scholar]

- Broccolo A. A piece of my mind. My father's hands. JAMA. 1997;277:1809. doi: 10.1001/jama.277.22.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodzinski E. Theatre in health and care. Hampshire, England: Palgrave Macmillan; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Brookes T. Signs of life: A memoir of dying and discovery. New York: Times Books; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bunston T, Mings D, Mackie A, Jones D. Facilitating hopefulness: The determinants of hope. Journal of Psychology Oncology. 1995;13:79–104. [Google Scholar]

- Byock I. Dying well: The prospect for growth at the end of life. New York: Riverhead Books; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Calman KC. Definitions and dimensions of quality of life. In: Aaronson NK, Beckman J, editors. The quality of life of cancer patients. New York: Raven Press; 1987. pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Christians CG, Carey JW. The logic and aims of qualitative research. In: Stempel GHI, Westley BH, editors. Research methods in mass communication. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1989. pp. 354–374. [Google Scholar]

- Doukas DJ, McCullough LB, Wear S. Reforming medical education in ethics and humanities by finding common ground with Abraham Flexner. Academic Medicine. 2010;85:318–323. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c85932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duque G, Fung S, Mallet L, et al. Learning while having fun: the use of video gaming to teach geriatric house calls to medical students. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2008;56:1328–1332. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow JM, Cash DK, Simmons G. Communication with cancer patients and their families. In: Blitzer A, et al., editors. cancer Communicating with patients their families. Philadelphia: The Charles Press; 1990. pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman HS, DiMatteo MR. Relations with others, social support, and the health care system. In: Friedman HS, DiMatteo MR, editors. Interpersonal issues in health care. New York: Academic; 1982. pp. 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Gotay CC. The experience of cancer during early and advanced stages: The views of patients and their mates. Social Science & Medicine. 1984;18:605–613. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(84)90076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotcher JM. The effects of family communication on psychosocial adjustment of cancer patients. Journal of Applied Communication Research. 1993;21:176–188. [Google Scholar]

- Gotcher JM. Well-adjusted and maladjusted cancer patients: An examination of communication variables. Health Communication. 1995;7:21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Gray PH, Van Oosting J. Performance in life and theatre. Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Harris J, Bowen DJ, Badr H, et al. Family communication during the cancer experience. Journal of Health Communication. 2009;14:76–84. doi: 10.1080/10810730902806844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich RL, Schag CC, Ganz PA. Living with cancer: the Cancer Inventory of Problem Situations. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1984;40:972–980. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198407)40:4<972::aid-jclp2270400417>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensel WA. A piece of my mind. Bea's legacy. JAMA. 1997;277:1913–1914. doi: 10.1001/jama.277.24.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann JF, Wojtkowiak SL, Houts, et al. Helping people cope: A guide for families facing cancer. Pennsylvania Department of Health; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hess BB, Soldo BJ. Husband and wife networks. In: Sauer WJ, Coward RT, editors. Social support networks and the care of the elderly: Theory, research, and practice. New York: Springer; 1985. pp. 67–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hilton BA. Family communication patterns in coping with early breast cancer. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1994;16:366–388. doi: 10.1177/019394599401600403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton J. An assessment of open communication between people with terminal cancer, caring relatives, and others during home care. Journal of Palliative Care. 1998;14:15–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopper R. Conversational dramatism: A symposium. Text and Performance Quarterly. 1993;13:181–183. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph ST. One of the family. Nursing. 1992;22:92. doi: 10.1097/00152193-199208000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Permanente. Education Theatre Programs (on-line) 2011 Available at: http://xnet.kp.org/etp/

- Keller M, Henrich G, Sellschopp A, et al. Between distress and support: Spouses of cancer patients. In: Baider L, Cooper CL, De-Bour AK, editors. Cancer and the family. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1996. pp. 187–223. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk RS. Breast cancer: A family survival guide. Choice. 1995;33:498. [Google Scholar]

- Krackov SK, Levin RI, Catanese V, et al. Medical humanities at New York University School of Medicine: an array of rich programs in diverse settings. Academic Medicine. 2003;78:977–982. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200310000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreps G, Kunimoto EN. Effective communication in multicultural health care settings. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Learningcenter.org. Writers and producers honored for addressing medical and ethical issues in television storylines (on-line) Available at: http://www.learcenter.org/images/event_uploads/Sentinel06Winners.pdf.

- Leiber L, Plumb MM, Gerstenzang ML, et al. The communication of affection between cancer patients and their spouses. Psychosomatic Medicin.e. 1976;38:379–89. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197611000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtman RR, Taylor SE. Close relationships and the female cancer patient. In: Andersen BL, editor. Women with cancer: Psychological perspectives. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1986. pp. 233–256. [Google Scholar]

- Litman TJ. The family as a basic unit in health and medical care: a social-behavioral overview. Social Science & Medicine. 1974;8:495–519. doi: 10.1016/0037-7856(74)90072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livestrong Foundation. 2013 http://www.livestrong.org.

- Lockwood AS. Communication and cancer: Creating a play script from family conversations. (Unpublished master’s thesis) San Diego, CA: San Diego State University; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- I, van den BH, McCormick L, et al. Openness to discuss cancer in the nuclear family: Scale, development, and validation. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1997;59:269–79. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199705000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mireault GC, Compas BE. A prospective study of coping and adjustment before and after a parent's death from cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 1996;14:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Montazeri A, Milroy R, Gillis CR, et al. Interviewing cancer patients in a research setting: The role of effective communication. Support Care in Cancer. 1996;4:447–454. doi: 10.1007/BF01880643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison JT. Evaluating factor analysis decisions for scale design in communication research. Communication Methods and Measures. 2009;3(4):195–215. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. 2013 http//www.cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/hcirb.

- Novak-Leonard JL, Brown AS. Beyond attendance: A multi-modal understanding of arts participation. National Endowment for the Arts. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- O'Hair D, Kreps G, Sparks L. Handbook of communication and cancer care. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press, Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Parisi SB. Nothing to fear. Nursing. 1996;26:80. doi: 10.1097/00152193-199611000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rait D, Lederberg M. The family of the cancer patient. In: Holland JC, Rowland JH, editors. Handbook of psychology: Psychological care of the patient with cancer. New York: Oxford; 1990. pp. 585–597. [Google Scholar]

- Renz MC. Room full of love. Nursing. 1994;24:104. doi: 10.1097/00152193-199411000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland JH. Interpersonal resources: Social support. In: Holland JC, Rowland JH, editors. Handbook of psychooncology: Psychological care of the patient with cancer. New York: Oxford; 1990. pp. 58–71. [Google Scholar]

- Seaburn DB, Lorenz A, Campbell TL, et al. A mother's death: Family stories of illness, loss, and healing. Families, System & Health. 1996;14:207–221. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro J, Rucker L. Can poetry make better doctors? Teaching the humanities and arts to medical students and residents at the University of California, Irvine, College of Medicine. Academic Medicine. 2003;78:953–957. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200310000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman AC, Simonton S. Coping with cancer in the family. The Family Journal. 2001;9:193–199. [Google Scholar]

- Shields P. Communication: A supportive bridge between cancer patient, family, and health care staff. Nursing Forum. 1984;21:31–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.1984.tb01093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater M. Entertainment education and the persuasive impact of narratives. In: Green MC, Strange JJ, Brock TC, editors. Narrative impact: Social and cognitive foundations. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 157–181. [Google Scholar]

- Spears JB. Until death do us part. Nursing. 1990;20:45. doi: 10.1097/00152193-199005000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stucky N. Toward an aesthetics of natural performance. Text and Performance Quarterly. 1993;13:168–180. [Google Scholar]

- Stucky N. Unnatural acts: Performing natural conversation. Literature in Performance. 1998;8:28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Stucky N, Glenn P. Invoking empirical muse: Conversation, performance, and pedagogy. Text and Performance Quarterly. 1993;13:192–196. [Google Scholar]

- Theatre of War. 2012 outsidethewirellc.com. [Google Scholar]

- University of California-Irvine. Program in Medical Humanities and Arts (on-line) 2012 Available at: http://www.meded.uci.edu/medhum/index.asp.

- Watson M. Psychological care for patients and their families. Journal of Mental Health. 1994;3:457–465. [Google Scholar]

- Wortman C, Dunkel-Schetter C. Interpersonal relationships and cancer. Journal of Social Issues. 1997;35:120–155. [Google Scholar]