Abstract

Coenzyme Q biosynthesis in yeast requires a multi-subunit Coq polypeptide complex. Deletion of any one of the COQ genes leads to respiratory deficiency and decreased levels of the Coq4, Coq6, Coq7, and Coq9 polypeptides, suggesting that their association in a high molecular mass complex is required for stability. Over-expression of the putative Coq8 kinase in certain coq null mutants restores steady-state levels of the sensitive Coq polypeptides and promotes the synthesis of late-stage Q-intermediates. Here we show that over-expression of Coq8 in yeast coq null mutants profoundly affects the association of several of the Coq polypeptides in high molecular mass complexes, as assayed by separation of digitonin extracts of mitochondria by two-dimensional blue-native/SDS PAGE. The Coq4 polypeptide persists at high molecular mass with over-expression of Coq8 in coq3, coq5, coq6, coq7, coq9, and coq10 mutants, indicating that Coq4 is a central organizer of the Coq complex. Supplementation with exogenous Q6 increased the steady-state levels of Coq4, Coq7, Coq9, and several other mitochondrial polypeptides in select coq null mutants, and also promoted the formation of late-stage Q-intermediates. Q supplementation may stabilize this complex by interacting with one or more of the Coq polypeptides. The stabilizing effects of exogenously added Q6 or over-expression of Coq8 depend on Coq1 and Coq2 production of a polyisoprenyl intermediate. Based on the observed interdependence of the Coq polypeptides, the effect of exogenous Q6, and the requirement for an endogenously produced polyisoprenyl intermediate, we propose a new model for the Q-biosynthetic complex, termed the CoQ-synthome.

Keywords: coenzyme Q supplementation, mitochondrial metabolism, protein complexes, Q-biosynthetic intermediates, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, ubiquinone

1. Introduction

Coenzyme Q (ubiquinone, CoQ or Q)1 is a lipid composed of a fully substituted benzoquinone ring and a polyisoprenyl chain, which contains six isoprene units in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Q6), eight in Escherichia coli (Q8), and ten in humans (Q10) [1]. Q is an electron carrier in the mitochondrial respiratory chain, and is essential in cellular energy metabolism [2]. The oxidized quinone (Q) accepts electrons from NADH via complex I, or succinate via complex II, and the reduced hydroquinone (QH2) donates electrons to cytochrome c via complex III. Instead of complex I, S. cerevisiae rely on the much simpler NADH:Q oxidoreductases that oxidize NADH external to the mitochondria (Nde1 and Nde2), or inside the matrix (Ndi1) [3]. In mammalian mitochondria Q functions to integrate the respiratory chain with many aspects of metabolism by serving as an electron acceptor for glycerol-3-phosphate, dihydroorotate, choline, sarcosine, sulfide, and several amino acid and fatty acylCoA dehydrogenases [4, 5]. QH2 also functions as a crucial lipid-soluble antioxidant [6] and decreased levels of Q are associated with mitochondrial, cardiovascular, kidney and neurodegenerative diseases [7–11]. A better understanding of the enzymatic steps and organization of the polypeptides and cofactors required for Q biosynthesis will aid efforts to determine how the content of this important lipid can be regulated for optimal metabolism and health.

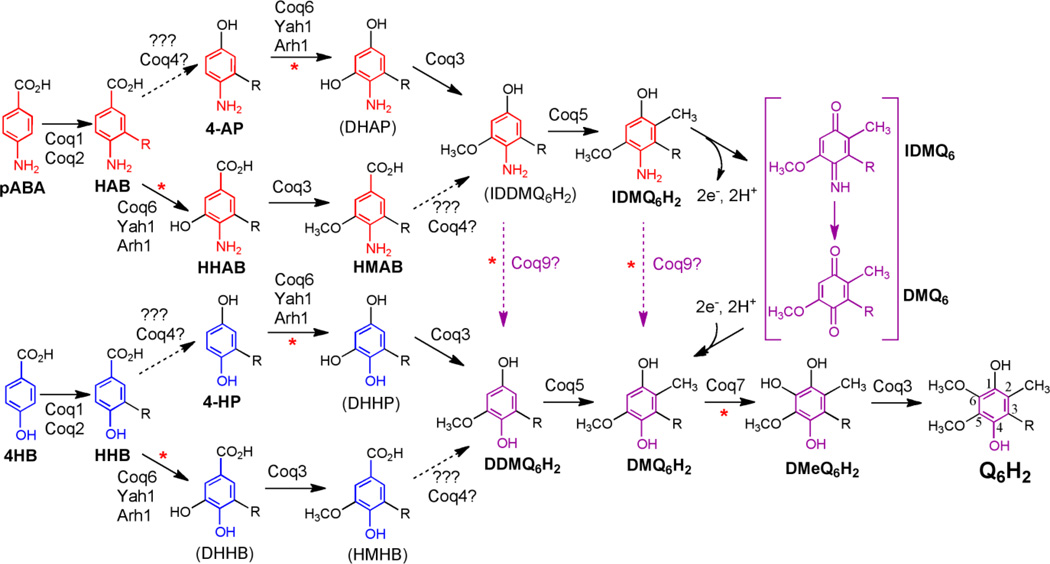

Q biosynthesis in S. cerevisiae requires at least eleven proteins, Coq1-Coq9, Arh1, and Yah1 (Fig. 1) [12–14]. Yeast mutants lacking any of the Coq1-Coq9 polypeptides are respiratory deficient due to the lack of Q. The Coq1 polypeptide synthesizes the hexaprenyl diphosphate tail, and Coq2 attaches the tail to either 4-hydroxybenzoic acid (4HB) or para-aminobenzoic acid (pABA); both are used as aromatic ring precursors in the biosynthesis of Q in yeast [13, 15]. The other Coq polypeptides catalyze ring modification steps including O-methylation (Coq3), C-methylation (Coq5), or hydroxylation (Coq6 and Coq7). Coq6 requires ferredoxin (Yah1) and ferredoxin reductase (Arh1), which presumably serve as electron donors for the ring hydroxylation step [13, 16]. Coq4, Coq8, and Coq9 polypeptides are essential for Q biosynthesis but their functional roles are not yet completely understood. In the Q-biosynthetic pathway proceeding from pABA, Coq9 is required for the replacement of the ring amino substituent with a hydroxyl group, although it remains uncertain exactly how this step is carried out [17].

Figure 1.

Q6 biosynthesis in S. cerevisiae proceeds from either 4HB or pABA. The classic Q biosynthetic pathway is shown in blue emanating from 4HB (4-hydroxybenzoic acid). R represents the hexaprenyl tail present in Q6 and all intermediates. The numbering of the aromatic carbon atoms used throughout this study is shown on the reduced form of Q6, Q6H2. Coq1p synthesizes the hexaprenyldiphosphate tail, which is transferred by Coq2p to 4HB to form HHB (3-hexaprenyl-4-hydroxybenzoic acid). Alternatively, the red pathway indicates that pABA (para-aminobenzoic acid) is prenylated by Coq2p to form HAB (3-hexaprenyl-4-aminobenzoic acid). Both HHB and HAB are early Q6-intermediates, readily detected in each of the coq null strains (Δcoq3-Δcoq9). Subsequent ring modification steps are thought to occur in the sequences shown, including hydroxylation by Coq6 in concert with ferredoxin (Yah1) and ferredoxin reductase (Arh1). Coq3 performs the two O-methylation steps, Coq5 the C-methylation step, and Coq7 performs the penultimate hydroxylation step. The functional roles of the Coq4, Coq8, and Coq9 polypeptides are elaborated in this study. Coq8p over-expression (hcCOQ8) in certain Δcoq strains leads to the accumulation of novel intermediates [17], suggesting these branched pathways. For example, in the presence of hcCOQ8, coq6 or coq9 mutants accumulate 4-AP (derived from pABA), and 4-HP (derived from 4HB) [17], indicating that in some cases decarboxylation and hydroxylation at position 1 of the ring may precede the Coq6 hydroxylation step. Purple dotted arrows designate the replacement of the C4-amine with a C4-hydroxyl and correspond to a proposed C4-deamination/deimination reaction, resulting in a convergence of the 4HB and pABA pathways. A putative mechanism to replace the C4-imino group with the C4-hydroxy group is shown in purple brackets for IDMQ6 but could also occur on IDDMQ6 (not shown). Several steps defective in the Δcoq9 strain are designated with red asterisks. Intermediates previously detected are shown in bold: 4-AP (3-hexaprenyl-4-aminophenol); DDMQ6H2, the reduced form of demethyl-demethoxy-Q6; DMQ6, demethoxy-Q6; DMQ6H2, demethoxy-Q6H2 (the reduced form of DMQ6); HHAB, 3-hexaprenyl-5-hydroxy-4-aminobenzoic acid; HMAB, 3-hexaprenyl-5-methoxy-4-aminobenzoic acid; 4-HP (3-hexaprenyl-4-hydroxyphenol); IDMQ6, (4-imino-demethoxy-Q6); IDMQ6H2, 4-amino-demethoxy-Q6H2 (the reduced form of IDMQ6). Intermediates shown in parentheses indicate that they have not yet been detected: DHAP, 5-hydroxy-4-aminohexaprenylphenol; DHHB, 3-hexaprenyl-4,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid; DHHP, 4,5-dihydroxy-hexaprenylphenol; HMHB, 3-hexaprenyl-4-hydroxy-5-methoxybenzoic acid; IDDMQ6H2, 4-amino-demethyl-demethoxyQ6H2.

Both genetic and physical evidence indicate that a multi-subunit Coq polypeptide complex is essential for Q biosynthesis [12, 18–20]. Deletion of any one of the COQ genes in S. cerevisiae leads to destabilization of several other Coq polypeptides; the levels of Coq4, Coq6, Coq7, and Coq9 polypeptides are significantly decreased in each of the coq1-coq9 null mutant yeast strains [20]. Although steady-state levels of the Coq3 polypeptide were also found to be decreased [20], Coq3 levels in mitochondria isolated from the coq4-coq9 null mutants were shown to be preserved in subsequent studies performed in the presence of phosphatase and protease inhibitors [17, 21]. As a result of the interdependence of the Coq polypeptides, coq3-coq9 null mutant yeast accumulate only the early intermediates 3-hexaprenyl-4-hydroxybenzoic acid (HHB) and 3-hexaprenyl-4-aminobenzoic acid (HAB), produced by the prenylation of 4HB and pABA, respectively (Fig. 1) [17]. Whereas each of the coq null mutants lacks the designated Coq polypeptide [20], several coq mutants harboring certain amino acid substitution mutations show a less drastic block in Q biosynthesis as compared to coq null mutants. For example, certain coq7 point mutants retain steady-state levels of the Coq7 polypeptide and accumulate demethoxy-Q6 (DMQ6), a late-stage Q-intermediate missing just one methoxy group [22, 23]. Some of the Coq polypeptides physically interact – biotinylated Coq3 co-purifies with Coq4 [18], and Coq9 tagged with the hemagglutinin epitope co-purifies with Coq4, Coq5, Coq6, and Coq7 polypeptides [20]. These studies were performed with digitonin-extracts of purified mitochondria. In such extracts the O-methyltransferase activity of Coq3 co-eluted with several of the other Coq polypeptides as high molecular mass complexes as determined by gel-filtration and by blue-native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) [18–21]. Indeed, the ability of Coq4 to organize high molecular mass complexes including Coq3 were shown to be essential for Q biosynthesis [19].

Several lines of evidence suggest that the Coq polypeptides and the multi-subunit Q-biosynthetic complex appear to be influenced by phosphorylation, either directly or indirectly due to Coq8. Coq8 (originally identified as Abc1) is a member of an ancient atypical kinase family [24]. Coq8/Abc1 homologs are required for Q biosynthesis in E. coli [25], yeast [26, 27], and humans [28, 29]. There is conservation of function as plant and human homologs of Coq8 are able to restore Q biosynthesis in yeast coq8 mutants [30, 31]. Conserved kinase motifs present in Coq8 are essential for maintenance of Q content [28, 29, 31], for the phosphorylation of Coq3, Coq5, and Coq7 polypeptides [21, 31], and the association of Coq3 with a high molecular mass Coq polypeptide complex [21]. Collectively these studies suggest that maintenance or assembly of the Q-biosynthetic complex and phosphorylated forms of Coq3, Coq5, and Coq7 polypeptides depend on the presence of intact kinase motifs present in Coq8. However, it is important to note that kinase activity has not been demonstrated directly for yeast Coq8, or for the Coq8 homologs in prokaryotes, plants, or animals. Thus substrates of Coq8 have yet to be identified. In fact, there is evidence that phosphorylation may negatively regulate yeast Coq7 [32]. Moreover, recent work identified yeast Ptc7 as a mitochondrial phosphatase recognizing Coq7 and indicated that Ptc7 is required for optimal Q6 content and function [33]. Thus although it appears that kinases and phosphatase activities modulate Q6 biosynthesis and function in yeast, the role(s) played by Coq8 remain to be determined.

The content of Coq8 profoundly influences Q biosynthesis in S. cerevisiae. Over-expression of Coq8 was shown to restore synthesis of DMQ6 in coq7 null mutant yeast [17, 34], suggesting the functional restoration of the Coq polypeptides up to this penultimate step of Q biosynthesis. In fact over-expression of Coq8 in the coq3 and coq5 null mutants restored steady-state levels of the Coq4, Coq6, Coq7, and Coq9 polypeptides [17, 35]. Similarly, over-expression of Coq8 in the coq3-coq9 null mutants restored steady-state levels of the unstable Coq polypeptides and resulted in the accumulation of late-stage Q-intermediates [17]. For example, over-expression of Coq8 in the coq5 null mutant led to the synthesis of a late-stage Q intermediate diagnostic of the blocked C-methylation step (demethyldemethoxy-Q6, DDMQ6) (Fig. 1) [17]. These results suggest a model whereby the over-expression of Coq8 stabilizes the remaining component Coq polypeptides, and allows the formation of high molecular mass Coq complexes.

A growing body of evidence indicates that Q or certain polyisoprenylated Q-intermediates also associate with the Q-biosynthetic complex. It was shown that DMQ6 co-elutes with Coq3 O-methyltransferase activity and high molecular mass Coq polypeptide complexes during size exclusion chromatography of digitonin extracts of mitochondria [18]. Yeast coq7 null mutants cultured in the presence of exogenous Q6 were able to synthesize DMQ6, and steady-state levels of Coq4 polypeptides were restored, indicating that the presence of Q6 itself may stabilize the Coq polypeptide complexes [23, 34]. Over-expression of Coq8 has no effect on either the coq1 or coq2 null mutants [17], which lack the ability to synthesize polyisoprenylated ring intermediates. This indicates that a polyisoprenylated component is essential for complex formation. Indeed, expression of diverse polyprenyl-diphosphate synthases, derived from prokaryotic species that do not synthesize Q, rescue Q synthesis in yeast coq1 null mutants, and restore steady-state levels of the sensitive Coq polypeptides, including Coq4 and Coq6 [36]. Thus, exogenously supplied Q, or a polyisoprenylated Q-intermediate is postulated to interact with the complex and/or may stabilize certain of the Coq polypeptides.

Recent evidence suggests that the interaction between the Coq10 polypeptide and Q is essential for the function of Q in respiration and for efficient de novo synthesis of Q [37–39]. Respiration in mitochondria isolated from yeast coq10 mutants can be rescued by the addition of Q2, a soluble analog of Q6. This is considered to be a hallmark phenotype of the yeast coq mutants unable to synthesize Q6. However, unlike the coq1-coq9 mutants, yeast coq10 mutants retain the ability to synthesize Q6, although its synthesis as measured with stable isotope-labeled ring precursors is less efficient [38]. The defects in Q respiratory function and de novo synthesis in the coq10 mutant are rescued by human [37] or Caulobacter crescentus orthologs of Coq10 [38]. Structural determination of the C. crescentus Coq10 ortholog CC1736 identified a steroidogenic acute regulatory protein-related lipid transfer (START) domain [40]. The START domain forms a hydrophobic binding pocket and family members have been shown to bind sterols, phospholipids and other hydrophobic ligands. START domain proteins function as transporters and/or act as sensors of lipid ligands that regulate lipid metabolism and signaling [41, 42]. The CC1736 START domain protein binds Q10, Q6, Q3, Q2 and DMQ3, but not ergosterol or a farnesylated analog of HHB [38]. Thus, the Coq10 START polypeptide binds Qn isoforms and facilitates both de novo Q biosynthesis and respiratory electron transport.

In this study we examine the sub-mitochondrial localization of the yeast Coq polypeptides, and determine the effects of over-expression of COQ8 on the high molecular mass Coq polypeptide complexes in the coq1-coq10 null mutants. The effects of Q supplementation on Coq polypeptide steady-state levels and the accumulation of Q-intermediates are also determined in each of the coq null mutants. The findings suggest that over-expression of Coq8 or Q6 supplementation enhances the formation or maintenance of the Coq polypeptide complexes and are integrated into a new model of Q-biosynthesis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Yeast strains and plasmids

S. cerevisiae strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Growth media for yeast were prepared as described [43], and included YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose), YPGal (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% galactose, 0.1% dextrose) and YPEG (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% ethanol and 3% glycerol). Yeast were transformed with lithium acetate as described [44]. Transformed yeast strains were selected and maintained in SD−Ura (selective synthetic medium with 2% dextrose lacking uracil) [43], modified as described [45]. The p4HN4 plasmid used in this study (hcCOQ8) contains the COQ8 gene in pRS426, a multi-copy yeast shuttle vector [46].

Table 1.

Genotype and Source of Yeast Strains

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| JM43 | MAT α leu2-3,112 ura3-52 trp1-289 his4-580 | [96] |

| W3031A | MAT a ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 | R. Rothsteina |

| BY4741 | MAT a his3Δ0 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 | Open Biosystems |

| W303Δcoq1 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 coq1::LEU2 | [36] |

| W303Δcoq2 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 coq2::HIS3 | [97] |

| CC303 | MAT α ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 coq3::LEU2 | [98] |

| W303Δcoq4 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 coq4::TRP1 | [99] |

| W303Δcoq5 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 coq5::HIS3 | [45] |

| W303Δcoq6 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 coq6::LEU2 | [49] |

| W303Δcoq7 | MAT α ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 coq7::LEU2 | [22] |

| BY4741Δcoq9 | MAT a his3Δ0 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 coq9::KanMX4 | Open Biosystems |

| W303Δcoq10 | MAT a ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 coq10::HIS3 | [37] |

Dr. Rodney Rothstein, Department of Human Genetics, Columbia University.

2.2 Mitochondrial isolation and immunoblot analyses with JM43 yeast

Yeast were cultured in YPGal medium (30 °C, 250 rpm) to an absorbance (A600nm) of 2–4. Preparation of spheroplasts and fractionation of cell lysates were performed as described [47]. Crude mitochondria were isolated and further purified over a linear Nycodenz gradient as described previously [48]. Protein concentrations were determined with the bicinchoninic acid assay (Thermo). Indicated amounts of protein from the Nycodenz-purified mitochondrial fractions were analyzed by electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on 12% acrylamide, 2.5 M urea, Tris/glycine gels, then transferred to Hybond ECL Nitrocellulose (Amersham Biosciences). Subsequent immunoblot analyses and treatment of membranes for detection of antibodies were as described [49]. Primary antibodies to yeast mitochondrial polypeptides (Table 2) were used at the following concentrations: Coq1, 1:10,000; Coq2, 1:1000; Coq3, 1:1000; Coq4, 1:2000; Coq5, 1:5000; Coq6, 1:500; Coq7, 1:1000; affinity purified Coq8, 1:100; the beta subunit of F1-ATPase complex (Atp2), 1:4000; cytochrome b2 (Cytb2) 1:5000; cytochrome c (Cytc), 1:10,000; cytochrome c1 (Cytc Heat shock protein 60 (Hsp60), 1:10,000. Goat anti-rabbit and goat anit-mouse secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Calbiochem) were each used at a 1: 10,000 dilution.

Table 2.

Description and Source of Antibodies

| Antibody | Source |

|---|---|

| Atp2 | Carla. M. Koehlera |

| Coq1 | [36] |

| Coq2 | [20] |

| Coq3 | [68] |

| Coq4 | [67] |

| Coq5 | [66] |

| Coq6 | [49] |

| Coq7 | [23] |

| Coq8 | [20] |

| Coq9 | [20] |

| Cytc | Carla M. Koehlera |

| Cytb2 | Carla M. Koehlera |

| Cytc1 | A. Tzagoloffb |

| Hsp60 | Carla M. Koehlera |

| Mdh1 | Lee McAlister-Hennc |

| Rip1 | B. Trumpowed |

Dr. Carla. M. Koehler, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, UCLA.

Dr. A. Tzagoloff, Department of Biological Sciences, Columbia University.

Dr. Lee McAlister-Henn, Department of Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry, University of Texas Health Sciences Center, San Antonio.

Dr. B. Trumpower, Department Biochemistry, Dartmouth Medical School.

2.3 Sub-mitochondrial localization of Coq2 and Coq7 polypeptides

Mitochondria from JM43 yeast (3 mg protein, 150 µl) were suspended in five volumes of hypo-osmotic buffer (20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4), and incubated on ice for 30 min. The mixture was then centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C to separate the intermembrane space components (supernatant) from the mitoplasts (pellet), as described [50]. Mitoplasts were then sonicated (four 20-s-pulses on ice slurry, 20% duty cycle, 2.5 output setting; Sonifier W350, Branson Sonic Power Co.), then centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C to generate matrix (supernatant) and membrane (pellet) fractions. Alternatively, mitoplasts were subjected to alkaline carbonate extraction [51], and the mixture was then centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C to separate the integral membrane components (pellet) from the peripheral membrane and matrix components (supernatant). Equal aliquots of Nycodenz-purified mitochondria, untreated mitoplasts, pellet and supernatant fractions from either sonication or alkaline carbonate extraction, and intermembrane space components were subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis followed by immunoblot analyses.

Proteinase K treatment of mitochondria was performed as described [52] with some modifications. Proteinase K was added from a freshly made concentrated stock solution (10 mg/ml) to mitochondria suspended in buffer C (0.6 M sorbitol, 20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4) (0.3 mg protein/ml) to a final concentration of 100 µg/ml. For treatment of mitoplasts, proteinase K was prepared in the hypo-osmotic buffer (20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4). When required, Triton-X100 or SDS were added to final concentration (w/v) of 1% or 0.5%, respectively, and incubated for 30 min at 4 °C. PMSF was added to inactivate the proteinase, followed by the addition of trichloroacetic acid (TCA; 60 °C) to a final concentration of 20%. The TCA pellets were subsequently collected by centrifugation and resuspended in Thorner buffer [53]; equal aliquots were processed for electrophoresis as described above.

2.4 Salt-wash treatments of sonicated mitoplasts

Salt-wash treatments were performed as described previously [54] with some modifications. Equal volumes of sonication buffer (as a no salt control) or sonication buffer containing either KCl or NaCl were added to sonicated mitoplasts to final concentrations of 0.5 M or 1.0 M for KCl, and 0.5 M for NaCl. The samples were incubated on ice for 15 min, followed by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C to separate the membrane associated components (pellet) from the soluble components (supernatant). Equal aliquots of starting mitochondria, unsonicated mitoplasts, intermembrane space components, membrane pellet, and supernatant fractions from salt-wash treatments of the sonicated mitoplasts were subjected to SDS-PAGE separation followed by immunoblot analyses.

2.5 Mitochondrial isolation and digitonin solubilization of W303 and BY4741 yeast strains

Yeast cultures were grown to an A600nm of 3–4 in YPGal media, and crude mitochondria were isolated from a total volume of 1.8 L of culture as described above. Crude mitochondria were further purified with an Optiprep discontinuous iodixanol gradient, and were collected from the interface of the gradient after ultracentrifugation. Briefly, the crude mitochondrial pellet was resuspended in 3 ml of Solution C. Solution C was prepared by adding 2 volumes of OptiPrep (60% w/v iodixanol; Sigma-Aldrich) to 1 volume of 0.8 M sorbitol, 60 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4. Solutions of ρ (density) = 1.10 and 1.16 g/ml were prepared by mixing Solution C with Solution D (3 + 7 and 6.25 + 3.75, v/v respectively). Solution D contains 0.6 M sorbitol, 20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4. In centrifuge tubes, 3 ml of crude mitochondria suspended in Solution C was layered at the bottom of a 14 × 89 mm Ultra-Clear centrifuge tube (Beckman), followed by 4.5 ml of the ρ =1.16 g/ml iodixanol solution, and finally 4.5 ml of the ρ = 1.10 g/ml iodixanol solution was layered on top. Tubes were subjected to centrifugation (80,000 × g for 3 h, 4 °C). The band of mitochondria was collected and washed with 10 volumes of solution D. Purified mitochondria were harvested by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min, 4 °C, and were resuspended in 1 ml of solution D, and stored at −80 °C. Aliquots of purified mitochondria (200 µg), were solubilized in 50 µl of 1.6% digitonin, 1 × protease inhibitor EDTA-free (Roche), 1:100 phosphatase inhibitor cocktail sets I and II (Calbiochem), 1 × NativePAGE sample buffer (Invitrogen), and mitochondria suspension buffer (0.6 M sorbitol, 20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4). Samples were incubated on ice for 1 h with mixing by pipetting up and down every 20 min. The soluble supernatant fraction was separated from the insoluble pellet by centrifugation in a Beckman Airfuge (100,000 × g, 10 min, chilled rotor).

2.6 Rescue of coq mutants with exogenous Q6

Medium containing a final concentration of 10 µM Q6 was prepared with a 6.54 mM Q6 stock in ethanol; vehicle control medium contained an equivalent volume of added ethanol (1.5 µl/ml). Both Q6-supplemented (+Q6) and unsupplemented (−Q6) YPD were sterile filtered. Designated wild-type W3031B or coq null mutants were grown in 20 ml YPD overnight and diluted to 0.1 A600nm in 18 ml of (+Q6) or (−Q6) YPD. Yeast cells were grown at 30 °C for 42 h. Cells (30 A600nm) were centrifuged for lipid extraction and 145 pmol Q4 was added to each cell pellet as an internal standard prior to lipid extraction. Yeast pellets were washed twice with distilled water before lipid extraction. Lipid extracts were analyzed by RP-HPLC-MS/MS [17]. Data were processed with Analyst version 1.4.2 software (Applied Biosystems). Cells (10 A600nm) were collected by centrifugation for protein extraction as described [55]. Aliquots (corresponding to 1.3 A600nm) of yeast whole cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% acrylamide gels followed by immunoblot analyses as described below.

To determine de novo synthesis of 13C6-DMQ6 in the coq7 null mutant strain in the presence or absence of exogenous Q6, cells were diluted to 0.1 A600nm in 18 ml of Q6-supplemented (+Q6) or unsupplemented (−Q6) YPD. Media also contained 10 µg/ml 13C6-4HB. Incubations proceeded for 42 h, and cell pellets were processed by lipid extraction and RP-HPLC-MS/MS as described above.

2.7 Two-dimensional Blue Native/SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analyses

Protein concentrations of purified mitochondria were determined by the bicinchoninic acid assay (Thermo). NativePAGE 5% G-250 sample additive (Invitrogen) was added to the supernatant from 200 µg of digitonin-solubilized mitochondria (50 µl) to a final concentration of 0.1%. BN-PAGE was performed as described in Native PAGE user manual with NativePAGE 4–16% Bis-Tris gel 1.0 mm × 10 wells (Invitrogen). First dimension gel slices were soaked in 65 °C 2 × SDS sample buffer for 10 min before loading onto pre-cast 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Proteins were transferred to Immobilon-P transfer membrane (Millipore), and blocked in 1% skim milk, phosphate-buffered saline, 0.1% Tween-20 (phosphate buffered saline is composed of 0.14 M NaCl, 1.2 mM NaH2PO4, and 8.1 mM Na2HPO4). Membranes were treated with the following primary antibodies (Table 2) at the dilution indicated: Coq4, 1:250; Coq7, 1:1000; Coq9, 1:1000; porin, 1:1000. Secondary antibodies were goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L chain specific peroxidase conjugate (Calbiochem).

3. Results

3.1 Sub-mitochondrial localization of Coq2 and Coq7 polypeptides

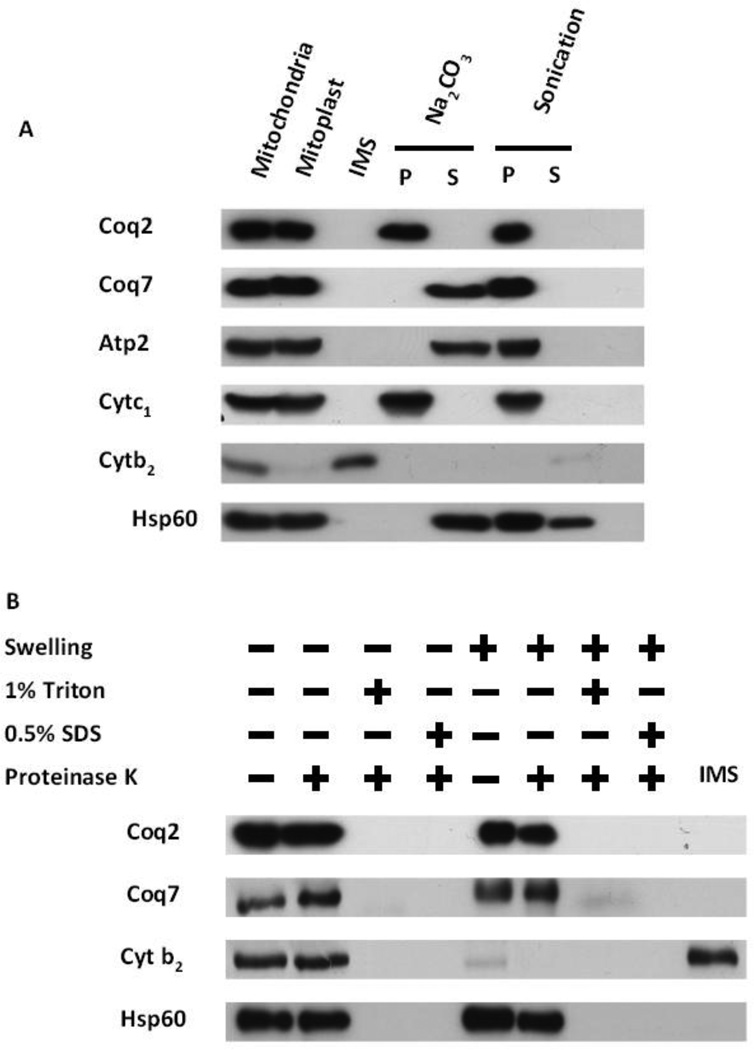

According to earlier studies [50, 56], the yeast Coq2 and Coq7 proteins both reside in mitochondria. However, the sub-mitochondrial localization of these proteins (in their untagged forms) was not determined. To determine the sub-mitochondrial localizations of Coq2 and Coq7, yeast mitochondria were further fractionated as described in Experimental Procedures. Purified mitochondria were treated with hypotonic buffer, resulting in the disruption of the outer membrane and subsequent release of soluble components of the intermembrane space while keeping the inner membrane intact. Immunoblot analyses of the sub-mitochondrial fractions indicated that Coq2 and Coq7 polypeptides associated with the pellet (mitoplast fraction) and did not co-localize with cytochrome b2 (Cytb2), the intermembrane space marker (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Coq2 is an integral membrane protein while Coq7 is peripherally associated to the inner mitochondrial membrane, facing toward the matrix side. (A), Mitochondria were subjected to a hypotonic swelling and centrifugation to separate intermembrane space protein (IMS) and mitoplasts. The mitoplasts were treated with 0.1 M Na2CO3, pH 11.5, or sonicated, then separated by centrifugation (100,000× g for 1 h) into supernatant (S) or pellet (P) fractions. (B), Intact mitochondria or mitoplasts were treated with 100 µg/ml Proteinase K for 30 min on ice, with or without detergent. Equal aliquots of pellet and TCA-precipitated soluble fractions were analyzed. Mitochondrial control markers are: Atp2, peripheral inner membrane protein; Cytb2, inter-membrane space protein; Cytc1, integral inner membrane protein; and Hsp60, soluble matrix protein.

Mitoplasts were further fractionated either by sonication, releasing soluble matrix components into the supernatant following high speed centrifugation, or by extraction with alkaline carbonate, which releases peripherally bound membrane proteins into the supernatant [57]. Sonication treatment partially dissociated Hsp60, the matrix marker [58], however, neither Coq2 nor Coq7 were released from the membrane/pellet fraction (Fig. 2A). Coq7 was released into the supernatant by alkaline carbonate extraction in a manner similar to Atp2, a peripheral inner membrane protein [59], while Coq2 remained in the pellet, along with Cytc1 an integral membrane marker [60]. These results indicated that Coq2 is an integral membrane protein while Coq7 behaves as a peripheral membrane protein.

To further characterize the membrane association of Coq2 and Coq7 proteins, purified mitochondria or mitoplasts were treated with Proteinase K in the absence and presence of detergent (1% Triton X-100 or 0.5% SDS). The results (Fig. 2B) showed that Coq2, Coq7, and Hsp60 polypeptides, were protected from the protease both in intact mitochondria and in mitoplasts. As expected, detergent treatment of either mitochondria or mitoplasts rendered all proteins protease-sensitive. The results indicate both Coq2 and Coq7 polypeptides are inner membrane proteins facing the matrix side in yeast mitochondria.

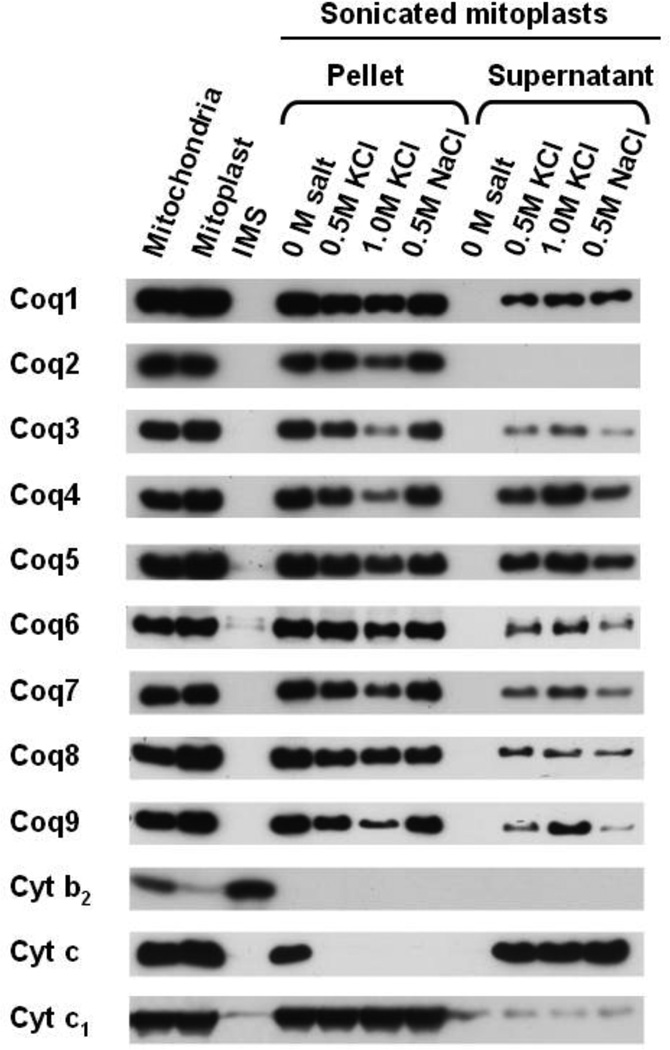

3.2 Coq2 is resistant to salt extraction while other Coq polypeptides are sensitive

The above sub-mitochondrial localization results indicated that Coq7 is a peripheral membrane protein. However, modeling studies have predicted Coq7 to be an interfacial inner mitochondrial membrane protein [61, 62]. Interfacial membrane proteins, such as prostaglandin synthase [63] and squalene cyclase [64], are embedded in the membrane via interaction with only one leaflet of the bilayer. To distinguish between a peripheral and an interfacial membrane association for Coq7, salt extraction analyses (with 0.5 M KCl, 1.0 M KCl, or 0.5 M NaCl) were performed on sonicated mitoplasts prepared as described above. The resulting mixtures were subsequently separated into supernatant and pellet (membrane associated) fractions via high-speed centrifugation. Western blot analysis of the fractions (Fig. 3) showed that Coq7 and each of the Coq polypeptides, except for Coq2, were partially released from the membrane following the addition of salt. Interestingly, the degree of dissociation of these proteins depended on salt concentration and not its identity per se, KCl versus NaCl. In contrast, Coq2 and the integral membrane marker, Cytc1, were resistant to salt extraction and thus remained in the membrane fraction. Cytochrome c, which peripherally attaches to the inner mitochondrial membrane through electrostatic interactions with fatty acids and acidic phospholipids [65], was released from the sonicated mitoplasts following salt addition, as expected. These results provide further support for the sub-mitochondrial localization data indicating that yeast Coq7 is a peripheral membrane protein on the matrix side as are Coq1, Coq3, Coq4, Coq5, Coq6, Coq8, and Coq9 polypeptides [20, 31, 36, 49, 66–68].

Figure 3.

Coq2 is resistant to salt extraction of sonicated mitoplasts while other Coq proteins are partially disassociated from the mitochondrial inner membrane. Purified mitochondria were subjected to hypotonic swelling to generate mitoplasts. Equal volumes of sonication buffer with or without salt were added to sonicated mitoplasts. Samples were incubated for 15 min on ice then separated by centrifugation (100,000 × g for 1 h) into supernatant or pellet fractions. Equal aliquots of pellet and TCA-precipitated supernatant fractions were analyzed.

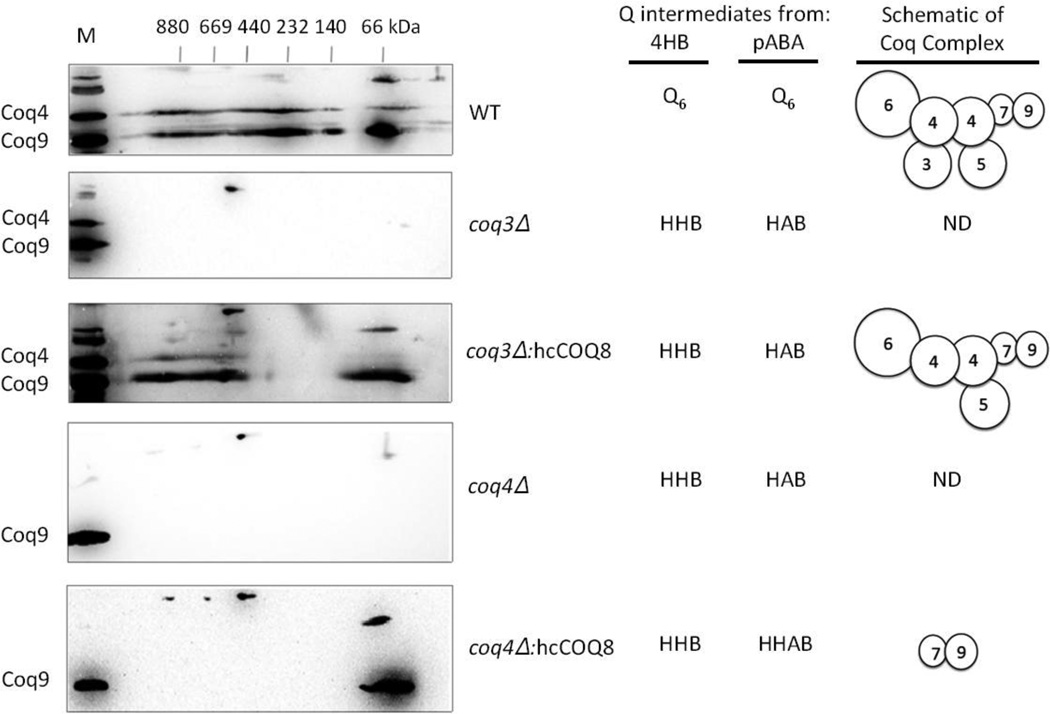

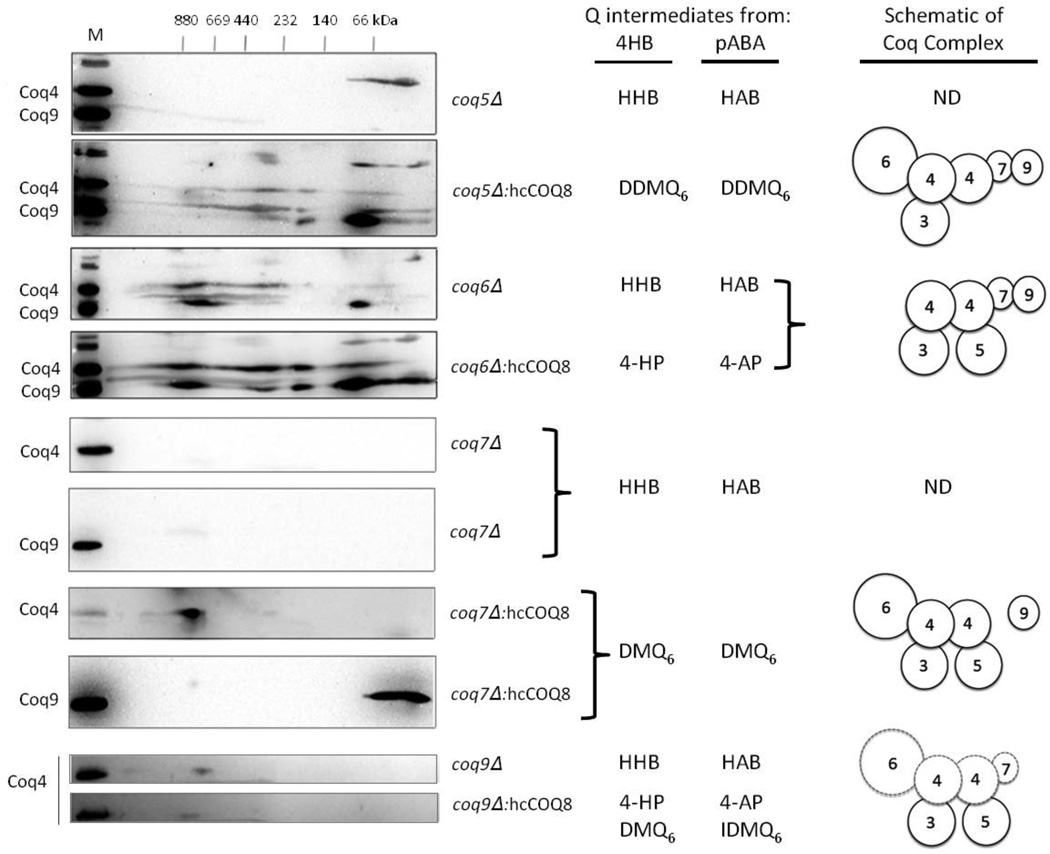

3.3 The Coq4 and Coq9 polypeptides are sensitive indicators of the Coq polypeptide Q-biosynthetic complexes – and over-expression of COQ8 stabilizes these complexes in certain coq null mutants

The co-localization of the Coq polypeptides with the mitochondrial inner membrane is consistent with their interaction in Q-biosynthetic complexes. The yeast Coq4 and Coq9 polypeptides co-purify with other Coq polypeptides and both migrate at high molecular mass in separation of digitonin extracts of mitochondria [18–21]. Thus, we used the Coq4 and Coq9 polypeptides as sensitive indicators of the state of the high molecular mass Coq complexes. Mitochondria from wild type and coq null mutant yeast were purified, solubilized with digitonin, separated by two-dimensional blue native/SDS PAGE, and antibodies against Coq4 and Coq9 were used to detect their presence. In digitonin extracts of wild-type mitochondria, Coq4 and Coq9 polypeptides are detected in several high molecular mass complexes (from 669 to >880 kDa) (Fig. 4). The Coq4 and Coq9 polypeptides are also detected at lower molecular mass (66 – 440 kDa), perhaps indicating their presence in partial-or distinct sub-complexes. In contrast, Coq4 and Coq9 were not detected in digitonin extracts of mitochondria isolated from coq3, coq4, coq5, or coq7 null mutant strains (Figs. 4 and 5). In each of the coq3-coq9 null mutant strains, the lack of one of the Coq polypeptides is thought to destabilize the Coq polypeptide complex, and the mutants accumulate only the early Q-intermediates HHB and HAB, generated from the aromatic ring precursors 4HB and pABA, respectively (Figs. 1, 4and 5). In contrast, the Coq4 and Coq9 polypeptides are detected at high molecular mass in the coq6 null mutant, and the Coq4 polypeptide is detected in the coq9 null mutant (Fig. 5). These observations are consistent with the presence of steady state levels of these polypeptides noted previously in these two null mutants [17]. Schematics showing possible interactions between the Coq polypeptides are depicted in Figs. 4 and 5.

Figure 4.

Over-expression of Coq8 in the coq3 null mutant, but not in the coq4 null mutant, stabilizes the multi-subunit Coq polypeptide complex. Mitochondria were isolated from WT (W303-1A), coq3 null or coq4 null with and without the over-expression of Coq8 (hcCOQ8). Purified mitochondria (200 µg protein), were separated by two-dimensional blue native/SDS PAGE, and the immunoblots were probed with antibodies against Coq4 and Coq9. A sample of wild-type mitochondria separated just in the SDS-second dimension served as a positive control and is designated by M. Q or Q-intermediates derived from either 4HB or pABA that accumulated in the yeast strains were determined in the study by Xie et al. [17]. The coq mutants over-expressing Coq8 continue to produce HHB and HAB, but in addition the coq4 mutant also accumulates HHAB. Schematics show interactions of the Coq polypeptides and illustrate interactions potentially favored by over-expression of Coq8; ND, Coq polypeptides not detected.

Figure 5.

Over-expression of Coq8 in coq5, coq6, coq7 or coq9 null mutant strains stabilizes the multi-subunit Coq polypeptide complex. Mitochondria were isolated from yeast strains harboring a deletion in one of the coq5, coq6, coq7, or coq9 genes with and without the over-expression of Coq8 (hcCOQ8). Purified mitochondria (200 µg protein) were separated by two-dimensional blue native/SDS PAGE, and the immunoblots were probed with antibodies against Coq4 and Coq9. A sample of wild-type mitochondria separated only in the SDS-second dimension served as a positive control and is designated by M. Q-intermediates derived from either 4HB or pABA that accumulated in the yeast mutants were determined in the study by Xie et al. [17]. The coq mutants over-expressing Coq8 continue to produce HHB and HAB, but in addition the designated late-stage Q-intermediates are also observed. Schematics show interactions of the Coq polypeptides and illustrate interactions potentially favored by over-expression of Coq8; dotted lines indicate that steady state-Coq polypeptides are present but are decreased relative to wild type; ND, Coq polypeptides not detected.

The over-expression of Coq8, a putative kinase, has dramatic effects on the phenotypes of the coq null mutants. Over-expression of Coq8 restores steady state levels of several of the Coq polypeptides, and enables the synthesis of late-stage Q-intermediates in several of the coq null mutants [17]. To investigate whether over-expression of Coq8 stabilizes high molecular mass Coq polypeptide complexes, mitochondria were prepared from coq null mutant yeast over-expressing Coq8, and digitonin extracts were separated by two-dimensional blue native/SDS PAGE. We were particularly interested in examining the high molecular mass complexes in the coq3 and coq4 mutants, because over-expression of Coq8 stabilizes the Coq6, Coq7, and Coq9 polypeptides, yet the coq3 and coq4 mutants persist in accumulating early Q-intermediates. Over-expression of Coq8 in the coq3 mutant restored Coq4 and Coq9 polypeptides to both high and low molecular mass complexes (440–880 kDa and 66 kDa) (Fig. 4), yet only early-stage intermediates HHB (with 4-HB as precursor) and HAB (with pABA as precursor) were detected in this strain [17]. Over-expression of Coq8 in the coq4 null mutant restored the presence of the Coq9 polypeptide, although it was detected in only a low molecular mass complex (66 kDa) (Fig. 4); under these conditions, HHAB is detected (Fig. 1) [17], indicating the presence of functional Coq6. These results indicate that although over-expression of Coq8 stabilizes Coq6, Coq7 and Coq9 polypeptides in the coq4 mutant, in the absence of the Coq4 polypeptide, a high molecular mass complex is not observed, and HHAB is the only novel Q-intermediate detected. Conversely, although the over-expression of Coq8 in the coq3 mutant restores high molecular mass complexes of Coq4 and Coq9, this does not appear to result in production of new Q-intermediates.

The effects of Coq8 over-expression on the native molecular mass of the Coq4 and Coq9 polypeptides were also studied in the coq5, coq6, coq7, and coq9 null mutants. Over-expression of Coq8 restored the Coq4 and Coq9 polypeptides to several high and low molecular mass complexes in the coq5 and coq6 null mutants (Fig. 5). Over-expression of COQ8 restored the Coq4 polypeptide to a high molecular mass complex and the Coq9 polypeptide to a low molecular mass complex in the coq7 null yeast mutant (Fig. 5). In the coq5, coq6 and coq7 null mutants, over-expression of Coq8 enables synthesis of late-stage Q-intermediates: coq5 null mutant accumulates DDMQ6, coq6 null accumulates 4-HP (with 4-HB as precursor) and 4-AP (with pABA as precursor), and coq7 null accumulates DMQ6 [17]. Coq4 steady-state levels decrease dramatically in the coq9 null mutant, but a small amount of Coq4 is detected near 669 kDa. Over-expression of COQ8 in the coq9 null mutant has only mild effects on Coq4 steady-state levels [17], but Coq4 is present at a higher molecular weight (around 800 kDa) (Fig. 5). The coq9 null mutant harboring multi-copy Coq8 accumulates 4-HP and DMQ6 (with 4-HB as precursor) and 4-AP and IDMQ6 (with pABA as precursor)[17]. These results indicate that over-expression of COQ8 stabilizes Coq polypeptide complexes in several of the coq null mutants.

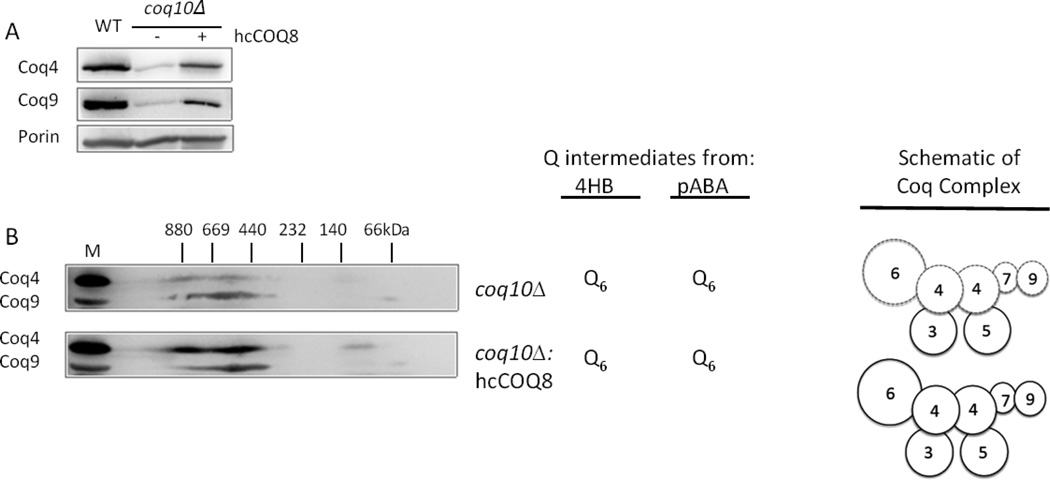

3.4 Over-expression of COQ8 enhances Coq4 and Coq9 levels in a coq10 null mutant

Previous work showed that steady-state levels of Coq4, Coq6, Coq7, and Coq9 polypeptides were decreased in the coq10 null mutant [20]. Although the coq10 null mutant produces Q6, the rate of de novo Q6 biosynthesis is decreased relative to that of wild-type yeast [38]. Moreover, the respiratory defect and Q6 de novo biosynthesis in the coq10 mutant is rescued by over-expression of COQ8 [37, 38]. Over-expression of COQ8 enhances steady-state levels of Coq4 and Coq9 in the coq10 null mutant (Fig. 6A). While both Coq4 and Coq9 are detected in high molecular mass complexes in the coq10 null mutant, over-expression of COQ8 appears to increase the association of Coq4 with the complex (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Over-expression of Coq8 in coq10 null mutant strain stabilizes the Coq4 and Coq9 polypeptide levels. Mitochondria were purified from coq10 null mutant yeast strain with and without the over-expression of Coq8 (hcCOQ8). (A), Purified mitochondria (20 µg protein) were subject to SDS-PAGE and Western blot probing with antibodies against Coq4, Coq9, and Porin. (B), Purified mitochondria (200 µg protein), were subjected to two-dimensional Blue Native/SDS PAGE, and immunoblots were probed with antibodies against Coq4 and Coq9. A sample of wild-type mitochondria separated only in the SDS-second dimension served as a positive control and is designated by M. The coq10 mutant produces Q6 from 4HB and pABA and retains high molecular mass complexes of the Coq polypeptides as indicated by the schematic of the Coq complex; dotted lines indicate that steady state-Coq polypeptides are present but are decreased relative to wild type.

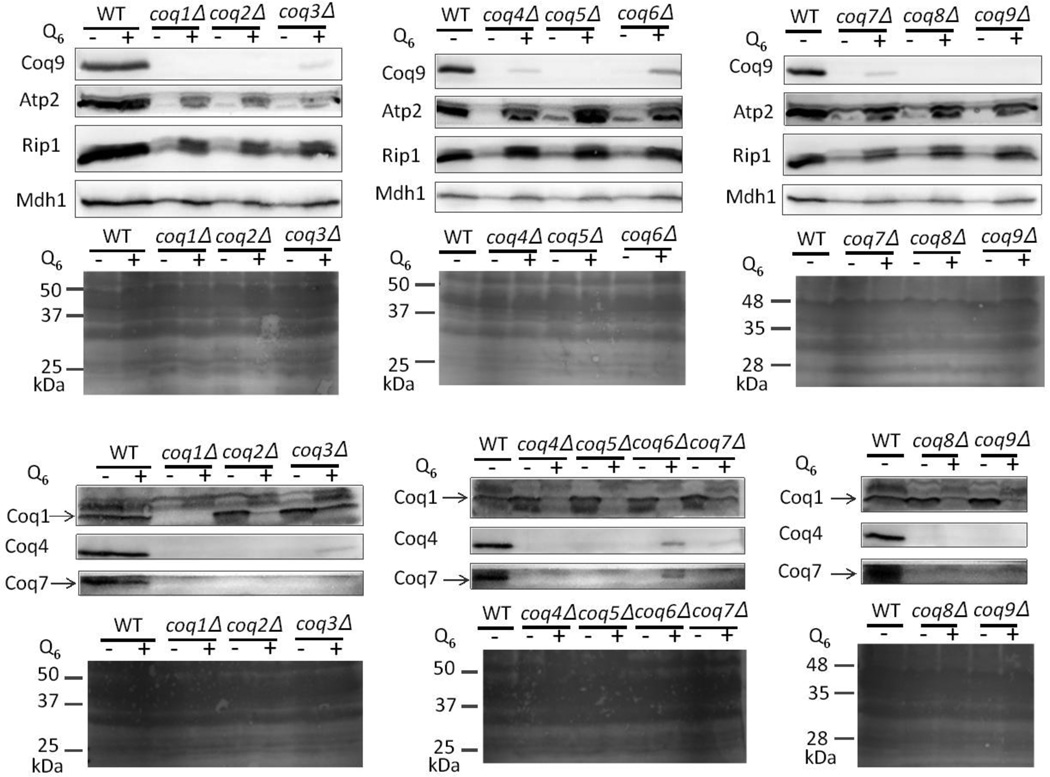

3.5 Q6 supplementation changes steady-state levels of certain Coq polypeptides and promotes accumulation of late-stage Q-intermediates in certain coq null mutants

Exogenous Q6 has been shown to rescue the growth of the S. cerevisiae coq2, coq3, coq5, coq7, coq8, coq9, and coq10 null mutants on media containing non-fermentable carbon sources [12, 26, 37, 50, 69]. We were able to rescue the growth of each of the coq1-coq9 null mutants on YPEG medium containing ethanol and glycerol as non-fermentable carbon sources, with the addition of 2 µM Q6 to the medium (data not shown). To determine the effect of exogenous Q6 on the Coq polypeptide levels, each of the coq1-coq9 null mutants was cultured in YPD in the presence or absence of exogenous Q6. For these experiments YPD medium was chosen because growth of the coq null mutants in the absence of Q6 is supported by dextrose. Previous studies indicate that both plasma membrane and mitochondrial Q6 content in coq7 null mutant (W303 genetic background) were increased when cultured in YPD supplemented with 2 µM Q6 [70]. Succinate-cytochrome c reductase activity also increased under these conditions, indicating exogenous Q6 restored activity in the mitochondrial respiratory chain [70]. The YPD medium was supplemented with 10 µM Q6, because this concentration is near optimal for restoration of growth [69]. Wild-type yeast and each of the coq null mutants in YPD were cultured in either the presence or absence of 10 µM Q6. The addition of Q6 does not appear to affect mitochondrial protein levels in wild-type yeast (Fig. 7). However, Q6 supplementation increases Coq9 polypeptide steady-state levels in coq3, coq4, coq6 and coq7 null mutants and increases Coq4 in coq3, coq6 and coq7 null mutants (Fig. 7). The most significant increases in Coq4, Coq7 and Coq9 polypeptide levels were observed in the coq6 null mutant supplemented with Q6 (Fig. 7). In contrast, Q6 supplementation decreases steady-state levels of Coq1 in coq2-coq9 null mutants. To determine whether supplementation with Q6 affects other mitochondrial proteins, we investigated the steady-state levels of the beta subunit of the F1 sector of mitochondrial F1F0 ATP synthase (Atp2), malate dehydrogenase (Mdh1), and the Rieske iron-sulfur protein (Rip1) of the cytochrome bc1 complex. The addition of Q6 increases steady-state levels of Atp2, Mdh1 and Rip1 in each of the coq null mutants, suggesting that supplementation with Q6 may have general protective effects on mitochondria.

Figure 7.

Inclusion of exogenous Q6 during culture of coq1-coq9 null yeast mutants stabilizes certain Coq and mitochondrial polypeptides. Wild type or coq1-coq9 null mutant yeast were grown in 18 ml of YPD with either 1.5 µl ethanol/ml medium (no Q6 addition) or the same volume of Q6 dissolved in ethanol giving a final concentration of 10 µM Q6 (+Q6) for 42 hours. Yeast cells (10 A600nm) were collected as pellets. Protein extracts were prepared from the pellets and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot. Immunoblots were performed with antibodies against Coq1, Coq4, Coq7, Coq9, Atp2, malate dehydrogenase (Mdh1), or Rieske iron-sulfur protein (Rip1). Ponceau staining was used to detect the total proteins transferred to the membrane and served as the loading control.

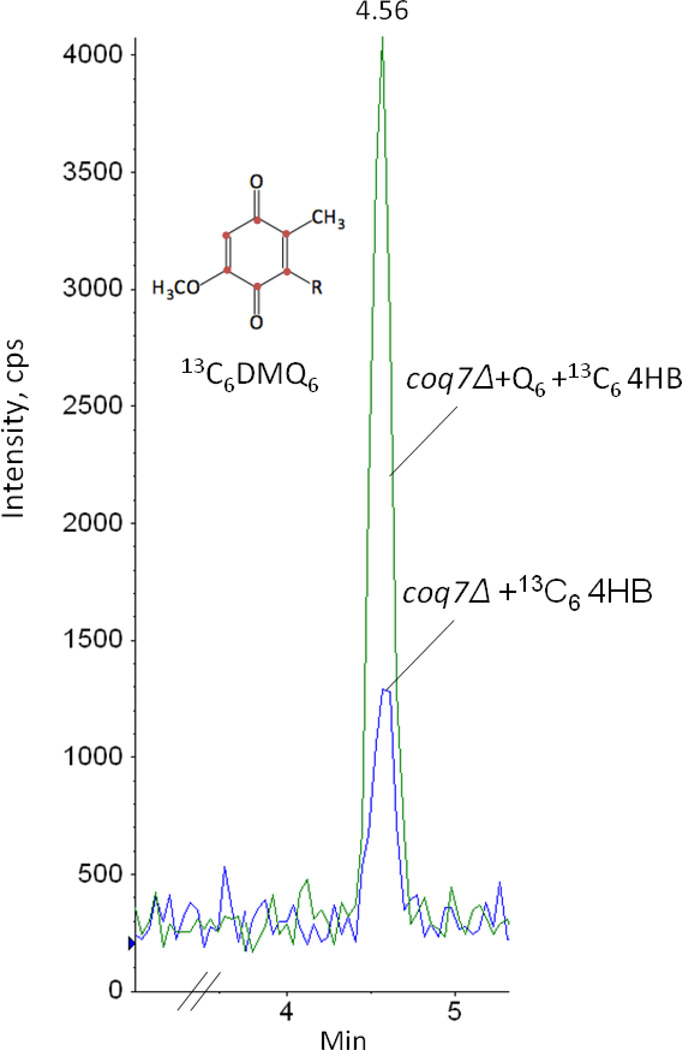

The effect of Q6 supplementation on Q intermediates was assessed in each of the coq null mutants. The coq3-coq9 null mutants accumulate only early stage intermediates HHB and HAB (Fig. 1). However, DMQ6 is produced in coq7 null mutants cultured in the presence of exogenous Q6 [34]. Here, we used HPLC with tandem mass spectrometry to detect Q6 intermediates in lipid extracts of coq null mutants cultured in either the presence or absence of 10 µM exogenous Q6. We confirmed the accumulation of DMQ6 in the coq7 null mutant cultured in exogenous Q6 (Fig. 8). Since exogenous Q6 contains a small amount of DMQ6, 13C6-4HB was used to detect de novo synthesis of 13C6-DMQ6. A very small amount of 13C6-DMQ6 was detected in coq7 null mutant labeled with 13C6-4HB. (We note that DMQ6 is detectable in coq7 null mutant when lipid extracts are prepared from 30 A600nm or more yeast and attribute this to the high sensitivity LC-MS/MS system). In the presence of 10 µM exogenous Q6, 13C6-DMQ6 accumulation increased significantly in coq7 null mutant labeled with 13C6-4HB. 13C6-DMQ6 was identified by its retention time of 4.56 min (the same as DMQ6), and a precursor-to-product ion transition of 567.0/173.0, consistent with the presence of the 13C6-ring (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Exogenous Q6 increases synthesis of demethoxy-Q6 (DMQ6) in coq7 null mutant. Yeast coq7 null mutant was cultured in YPD with either 10 µg/ml 13C6 -4HB and 1.5 µl ethanol/ml medium (no Q6 addition) or 10 µg/ml 13C6 -4HB and the same volume of Q6 dissolved in ethanol giving a final concentration of 10 µM Q6 (+Q6) for 42 hours. Yeast cells (30 A600nm) were collected as pellets and washed twice with distilled water. Q4 (145.4 pmol) was added as internal standard. Lipid extracts were prepared from the pellets and analyzed by RP-HPLC-MS/MS. Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) detected precursor-to-product ion transitions 567.0/173.0 (13C6 -DMQ6). The green trace designates the 13C6-DMQ6 signal in the +Q6 condition, and the blue trace indicates the 13C6-DMQ6 signal in the absence of added Q6. The peak areas of 13C6-DMQ6 normalized by peak areas of Q4 are 0.0665 in coq7Δ +13C6-4HB and 0.215 in coq7Δ+ Q6 +13C6-4HB.

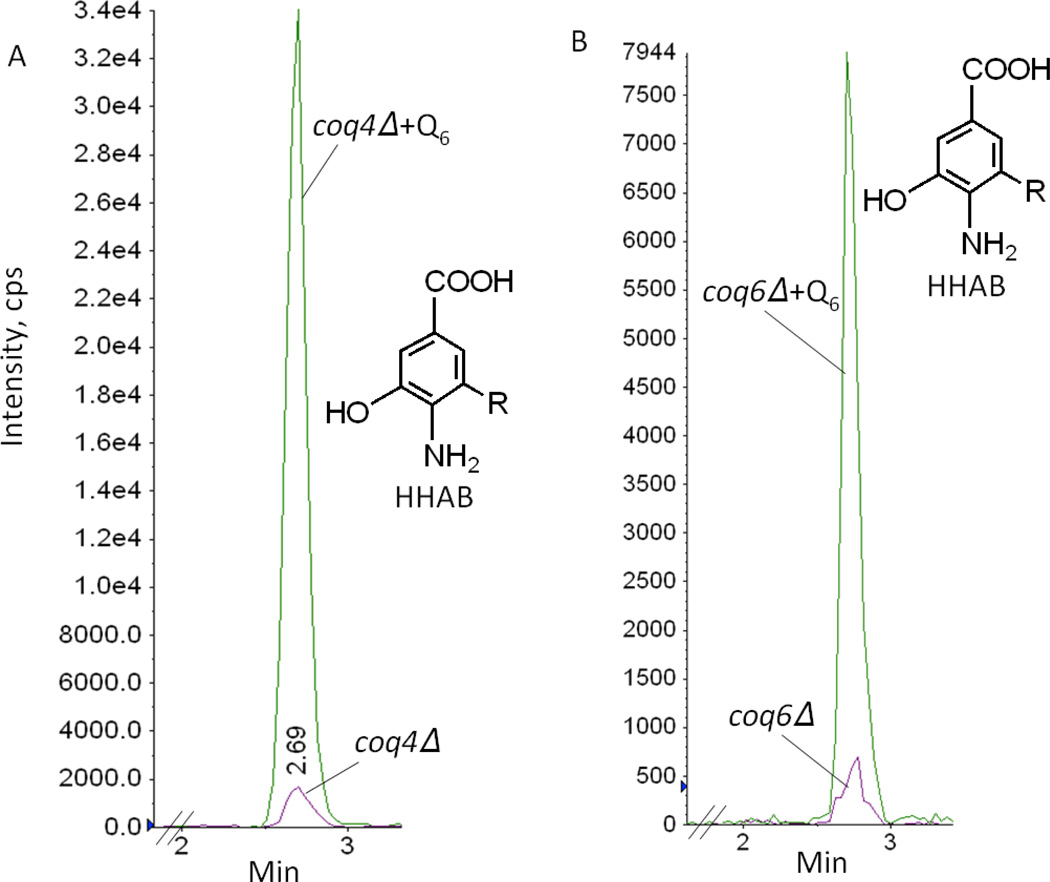

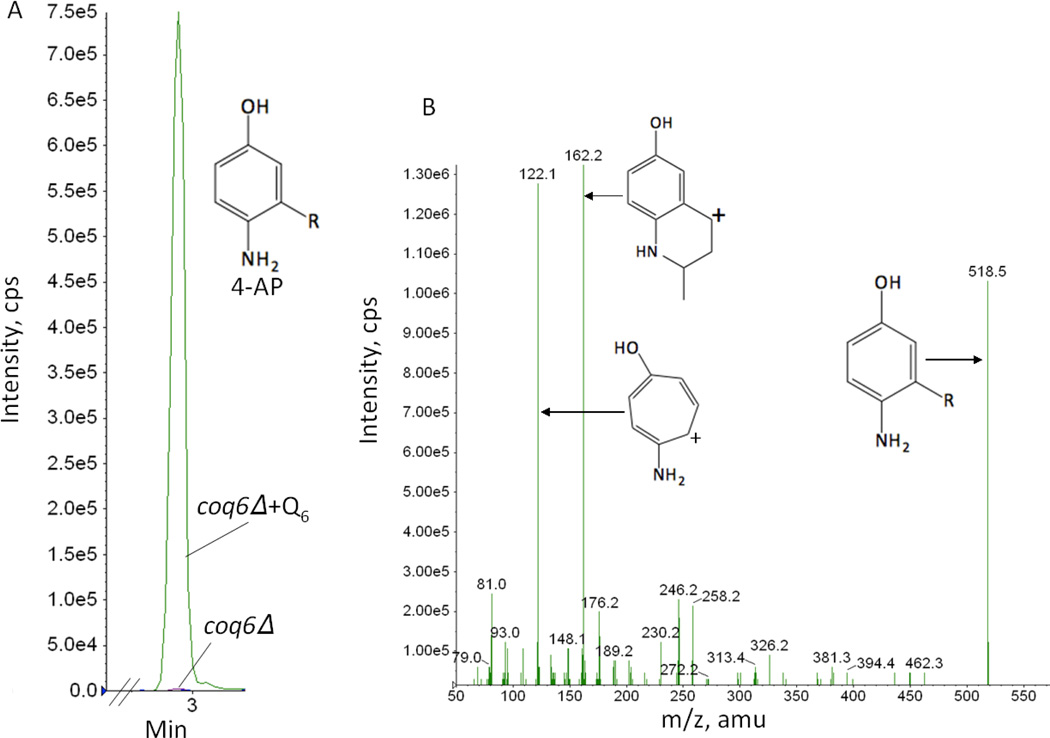

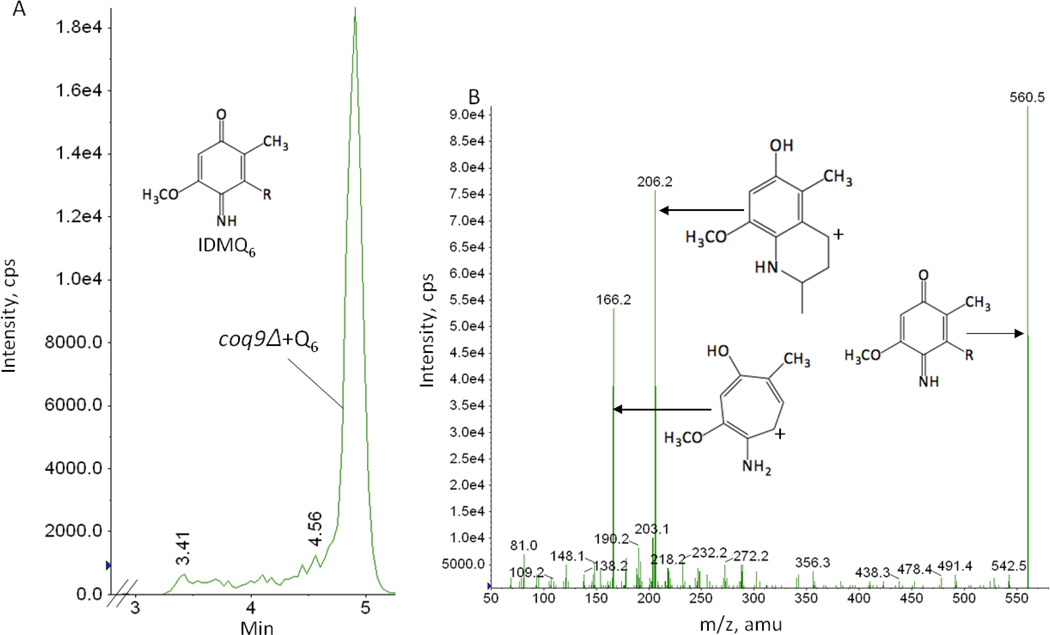

In addition, exogenous Q6 led to an increased accumulation of 3-hexaprenyl-4-amino-5-hydroxybenzoic acid (HHAB) in coq4 (Fig. 9A). This intermediate has a retention time of 2.69 min and a precursor-to-product ion transition of 562.0/166.0 detected with multiple reaction monitoring (MRM). We have previously detected HHAB in lipid extracts of coq4-1 mutants, harboring a point mutation [17]. Surprisingly, smaller but readily detectable amounts of HHAB (a product of the Coq6 step) were also detected in the coq6 mutant cultured with exogenous Q6 (Fig. 9B). In addition to HHAB, 4-AP increased significantly in the coq6 null mutant cultured with exogenous Q6 (Fig. 10A). 4-AP was identified by its retention time (2.88 min), precursor-to-product ion transition (518.5/162.2), and fragmentation spectrum (Fig. 10B). 4-AP has been shown to accumulate in certain coq6 point mutants [16], and in coq6 and coq9 null mutants over-expressing Coq8 [17]. The addition of Q6 caused the accumulation of imino-demethoxy-Q6 (IDMQ6) in the coq9 null mutant (Fig. 11A). This intermediate has a retention time of 4.9 min and a precursor-to-product ion transition of 560.5/166.1. Its identity is further confirmed by the fragmentation spectrum (Fig. 11B). In contrast, late-stage Q-intermediates were not detected in the other coq null mutants. Thus only coq4, coq6, coq7 and coq9 null mutants accumulate late-stage Q-intermediates upon the addition of Q6. These data indicate that Q6 stabilizes the Q-biosynthetic complex and allows later Q-intermediates to accumulate.

Figure 9.

Exogenous Q6 increases the accumulation of 3-hexaprenyl-4-amino-5-hydroxybenzoic acid (HHAB) in coq4 and coq6 null mutants. Yeast coq4 and coq6 null mutants were cultured in YPD with either 1.5 µl ethanol/ml medium (no Q6 addition) or the same volume of Q6 dissolved in ethanol giving a final concentration of 10 µM Q6 (+Q6) for 42 hours. Yeast cells (30 A600nm) were collected as pellets and washed twice with distilled water. Q4 (145.4 pmol) was added as internal standard. Lipid extracts were prepared from the pellets and analyzed by RP-HPLC-MS/MS. Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) detected precursor-to-product ion transitions 562.0/166.0 (HHAB) and 455.4/197.0 (Q4). The arbitrary units (cps) and the scale is the same for all the traces within the same panel. In panels A and B, green traces designate the HHAB signal in the +Q6 condition, and purple traces the HHAB signal in the absence of added Q6. The peak areas of HHAB normalized by peak areas of Q4 are 0.01 in coq4Δ (A), 0.14 in coq4Δ+ Q6 (A), 0.003 in coq6Δ (B), and 0.03 in coq6Δ+Q6 (B). The retention times of HHAB are 2.69 min in coq4Δ+Q6 (A), and 2.71 min in coq6Δ+Q6 (B).

4. Discussion

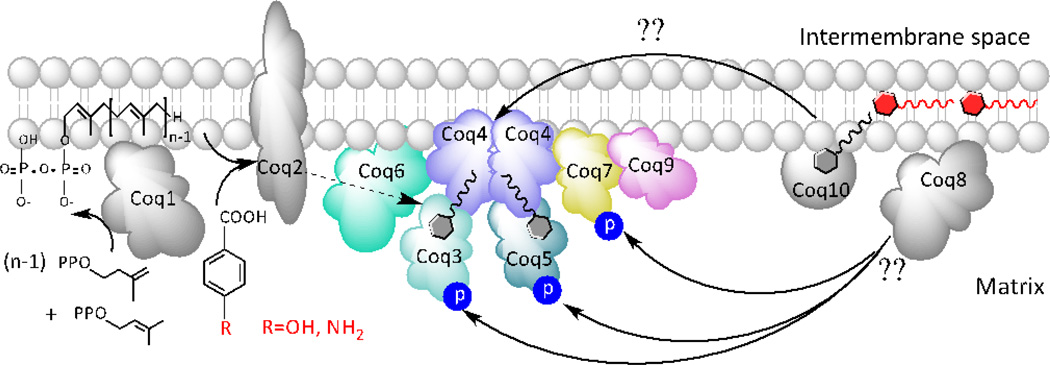

This study examined the location and organization of the yeast mitochondrial Q-biosynthetic complex. We found that over-expression of Coq8, an ancient atypical putative kinase, stabilizes the high molecular mass Coq polypeptide complex in several of the coq null mutants. Supplementation of growth medium with exogenous Q6 restored steady-state levels of Coq polypeptides and enhanced the production of late-stage Q-intermediates in certain coq null mutants. Based on the observed interdependence of the Coq polypeptides, the effect of exogenous Q6, and the requirement for an endogenously produced polyisoprenyl intermediate (summarized in Table 3), we propose a new model for the CoQ-synthome, a Coq multi-subunit polypeptide and lipid complex required for the biosynthesis of Q in yeast (Fig. 12).

Table 3.

Summary of the effect of over-expressing Coq8 or supplementation with exogenous Q6

| Strains | No Treatment | +hcCOQ8 | +10uM Q6 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polypeptides | Intermediates from: |

Polypeptides | Intermediates from: |

Polypeptides | Intermediates from: |

||||||||||

| Coq4 | Coq7 | Coq9 | 4HB | pABA | Coq4 | Coq7 | Coq9 | 4HB | pABA | Coq4 | Coq7 | Coq9 | 4HB | pABA | |

| WT | + | + | + | Q6 | Q6 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | + | + | + | Q6 | Q6 |

| Coq1Δ | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Coq2Δ | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Coq3Δ | − | − | − | HHB | HAB | + | + | + | HHB | HAB | + | − | + | HHB | HAB |

| Coq4Δ | − | − | − | HHB | HAB | − | + | + | HHB | HHAB | − | − | + | HHB | HHAB |

| Coq5Δ | − | − | − | HHB | HAB | + | + | + | DDMQ6 | DDMQ6 | − | − | − | HHB | HAB |

| Coq6Δ | − | − | − | HHB | HAB | + | + | + | 4-HP | 4-AP | + | + | + | HHB | HHAB, 4-AP |

| Coq7Δ | − | − | − | HHB | HAB | + | − | + | DMQ6 | DMQ6 | + | − | + | DMQ6 | DMQ6 |

| Coq8Δ | − | − | − | HHB | HAB | + | + | + | Q6 | Q6 | − | − | − | HHB | HAB |

| Coq9Δ | − | − | − | HHB | HAB | + | + | − | DMQ6 | IDMQ6 | − | − | − | N/A | IDMQ6 |

The Coq4 and Coq9 polypeptides were used as sensitive indicator polypeptides to monitor the state of high molecular mass Coq polypeptide complexes in digitonin extracts of mitochondria, as assayed by two-dimensional blue native/SDS PAGE. The over-expression of Coq8 in the coq null mutants was found to profoundly affect the association of Coq4 and Coq9 in high molecular mass complexes. The Coq4 polypeptide persists at high molecular mass with the over-expression of Coq8 in the coq3, coq5, coq6, coq7, and coq9 null mutants (Figs. 4 and 5). This finding indicates that deletion of any of these Coq polypeptide components has little impact on the association of Coq4 with a high molecular mass Coq complex. The Coq9 polypeptide persists at high molecular mass with the over-expression of Coq8 in the coq3, coq5 and coq6 null mutants, but is present only at low molecular mass in the coq4 and coq7 null mutants upon Coq8 over-expression (Fig. 5). Hence, we propose that Coq4 may be a crucial component through which Coq3, Coq5, Coq6, Coq7, and Coq9 associate to form the CoQ-synthome. Coq7 is an important component through which Coq9 associates with Coq4.

Based on these findings our model depicts Coq4 as a central organizer, and the Coq3, Coq5 and Coq6 polypeptides as more peripheral members of the CoQ-synthome (Fig. 12). In this model Coq4 is depicted as a homodimer, with each monomer harboring a binding site for the polyisoprenyl-tail of Q6 or a polyisoprenyl-intermediate. This is based on the structure determined for Alr8543, a Coq4 homolog from Nostoc sp. PCC7120, and the molecular modeling of the highly similar S. cerevisiae Coq4 [71]. Each monomer of the Alr8543 homodimer co-crystalized with a geranylgeranyl monophosphate, and Rea et al. [71] proposed that yeast Coq4 may similarly bind to the polyisoprenyl tail of HHB (or HAB), consistent with the idea that Coq4 forms a scaffold organizing the Coq polypeptide complex [19], facilitating the action of the Coq6 hydroxylase, the Coq3 and Coq5 methyltransferases, and the Coq7 hydroxylase. The model is also consistent with the hypothetical branched biosynthetic scheme of Q biosynthesis (Fig. 1). For example, in the presence of hcCOQ8, coq6 or coq9 mutants accumulate 4-AP (derived from pABA), and 4-HP (derived from 4HB) [17], indicating that in some cases decarboxylation and hydroxylation at position 1 of the ring (catalyzed by yet to be identified enzymes) might precede the Coq6 hydroxylation step.

The CoQ-synthome represents a minimal schematic model because the total predicted mass based on the sum of the component Coq polypeptides is only 230–240 kDa [31] (Fig. 12); this is well below the 1 MDa size of the complex estimated from blue-native gels. The stoichiometry of the Coq polypeptides in the complex is not known and it is likely that additional components remain to be identified. The model is consistent with the peripheral association of each of the Coq polypeptides to the matrix side of the mitochondrial inner membrane, with the exception of Coq2 (Figs. 2 and 3). In addition to interaction with Coq4, it is possible that the association of Coq polypeptides with the inner mitochondrial membrane may derive from interactions with Q6 and/or a polyisoprenyl-intermediate. So far, Coq2 is the only integral membrane protein of the Q-biosynthetic proteins. Previous models suggested that Coq2 might serve as an ideal anchor-protein candidate for the Coq complex [12], and blue native/SDS PAGE indicated Coq2 migrated at high molecular mass [21]. However, co-precipitation experiments have so far failed to identify any physical interactions between Coq2 and the other Coq polypeptides (data not shown). Based on this, Fig. 12 shows Coq1 and Coq2 independently generate HHB or HAB, early Q-intermediates that accumulate in each of the coq3 - coq9 null mutants.

Studies in S. cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe have set the stage for understanding Q biosynthesis in animals; many human and mouse COQ homologs have been shown to rescue the corresponding yeast coq mutants [14, 72]. Expression of human COQ4 has been shown to rescue the S. cerevisiae coq4 null mutant [73], suggesting that human COQ4 might maintain interactions with yeast Coq polypeptides. However, certain animal Q biosynthetic proteins require specific partner proteins to observe cross complementation of the yeast mutant. For example, Pdss1 and Pdss2 (Coq1 homologs) from S. pombe, mouse, and human form heterotetrameric complexes, and must be co-expressed to reconstitute synthesis of the polyisoprene-diphosphate tail [74, 75]. Human COQ9 has not yet demonstrated interspecific complementation of the yeast coq9 mutants [76]; this might be due to interactions of Coq9 with Coq7. Similar to yeast, the function of Coq7 in mouse requires Coq9. A homozygous Coq9X/X mouse, containing a Coq9-R239X stop codon mutation, displayed a severe reduction of Q9 content, accumulated DMQ9, and showed a profound decrease in steady state Coq7 polypeptide levels [77]. The Coq9X/X mouse model was patterned after human patients with Q deficiency and mitochondrial encephalomyopathy [76]. The recapitulation of the human disease in the Coq9X/X mouse model suggests that COQ7 hydroxylation of DMQ requires COQ9 in mice and humans. Other interactions between human COQ polypeptides have been reported recently. ADCK4 (a human homolog of yeast Coq8) was shown to interact with COQ6 and COQ7 polypeptides in podocyte cell cultures [78]. Although we have not detected Coq8 in direct association with any of the yeast Coq polypeptides, it is tempting to speculate that human ADCK4 may recognize COQ6 and COQ7 as potential substrates for phosphorylation. Interestingly, while expression of ADCK4 failed to rescue the yeast coq8 mutant [78], expression of human ADCK3 did rescue the coq8 mutant, partially restore Q6 content as well as phosphorylated forms of yeast Coq3, Coq5, and Coq7 [31].

We investigated the effects of Coq8 over-expression on the Coq4 and Coq9 polypeptides in the coq10 null mutant. Over-expression of Coq8 in the coq10 null mutant increases steady-state levels of the Coq4 and Coq9 polypeptides and their association with the high molecular mass Coq complexes (Fig. 6). In the coq10 null mutant the rate of Q biosynthesis is reduced but may be significantly increased by Coq8 over-expression, or by the expression of a START domain ortholog of Coq10 [38]. These findings are consistent with the model that the Coq10:Q polypeptide ligand complex functions as a chaperone of Q and that Q delivery to the CoQ-synthome is necessary for efficient de novo Q biosynthesis (Fig. 12), and/or for delivery of Q to the N-site of the bc1 complex [38, 79]. It is tempting to speculate that Coq10 may function to chaperone the “inactive” pool of Q (depicted as residing at the midplane of the bilayer [80, 81]) to form an “active” pool of Q, consistent with a dedicated subset of Q molecules performing electron transport within the respirasomes [82, 83].

Results presented here show that exogenous Q6 restores the growth of any of the coq1-coq10 null mutant yeast in medium containing a nonfermentable carbon source. This effect of supplementation with exogenous Q6 is known to require uptake; Q6 binds to soluble proteins derived from peptone in the growth medium and is taken up by cells and transported to mitochondria via an endocytic pathway [84]. James et al., [85] identified 16 yeast ORFs required for utilization of exogenous Q4 in a yeast double knockout library (ΔORFΔcoq2). We determined the steady-state levels of the Coq4, Coq7, and Coq9 polypeptides as indicators of the CoQ-synthome, and scanned for Q6-intermediates by HPLC tandem mass spectrometry. Upon the addition of Q6, the coq3, coq4, coq6, coq7 and coq9 null mutants accumulate distinct hexaprenyl Q-intermediates and/or show increased steady-state levels of one or more of the indicator Coq polypeptides (Figs 8–11 and Table 3). These findings confirm and extend previous studies showing that addition of exogenous Q6 restored de novo synthesis of DMQ6 and increased steady-state levels of the Coq4 polypeptide in a coq7 null mutant [23, 34]. These results indicate that Q6 itself may interact with certain Coq polypeptides and enhance formation of later Q-intermediates. Surprisingly, HHAB (a product of the Coq6 step) was detected in the coq6 mutant cultured with exogenous Q6 (Fig. 9B). It is possible that the presence of Q6 facilitates the function of another hydroxylase; such a scenario has been reported for hydroxylases in E. coli Q8 biosynthesis [86]. However, HHAB as identified in Fig. 9, may actually have the hydroxyl substituent located in another position on the ring. Determination of this will require purification of the intermediate and structural characterization.

In contrast, addition of exogenous Q6 had no discernable effect on the Coq4, Coq7, or Coq9 indicator polypeptides or late-stage Q-intermediates in the coq1, coq2, coq5 or coq8 null mutants (Fig. 7 and Table 3). The steady-state levels of Coq1, Coq2, and Coq5 polypeptides are not affected by deletions in any of the other COQ genes [20]. While Coq8 over-expression in the coq1 or coq2 null mutants has little effect, Coq8 over-expression in the coq5 null mutant allows production of DDMQ6, and enhances steady-state levels of the Coq4, Coq6, Coq9 and Coq7 polypeptides [17]. Because Coq5 physically interacts with the other core-Coq polypeptides, yet the stabilizing effect of exogenous Q6 on the other Coq polypeptides is not observed in the coq5 null mutant, the Coq5 polypeptide is required for the interaction of Q6 with CoQ-synthome (Fig. 12). On the other hand, there is no evidence that the Coq1 or Coq2 polypeptides are physically associated with the CoQ-synthome. In fact steady-state levels of indicator Coq polypeptides in the coq1 null mutant are restored by expression of diverse polyisoprenyl-diphosphate synthases, including those from species that do not produce Q and hence would not be expected to interact with Coq polypeptides in yeast [36]. These findings support the interpretation that the stabilizing effects of exogenously added Q6 or over-expression of Coq8 must depend on the synthesis of an endogenously produced polyisoprenyl-intermediate, such as HHB or HAB (Fig. 12).

In this study, steady-state levels of Coq1 are decreased upon supplementation of the coq null mutants with exogenous Q6. It is tempting to speculate that Coq1 may play a regulatory step in the pathway where increases in Q6 lead to a decrease in Coq1 polypeptide levels. This effect is not observed in wild type perhaps because supplementation with exogenous Q6 does not have a significant impact on mitochondrial Q6 content in wild-type yeast [70]. In contrast supplementation with exogenous Q6 dramatically increases mitochondrial content of Q6 in the coq null mutants, provided steps of endocytosis required for Q6 uptake and trafficking to mitochondria are retained [70, 84].

Dietary supplementation with Q10 can be an effective treatment for patients with partial defects in Q biosynthesis [87, 88], and also shows benefit in mouse and C. elegans models of Q deficiency [89–92], and in cell culture models of mitochondrial diseases [93, 94]. In this study we found that inclusion of exogenous Q6 in the growth medium increased steady-state levels of mitochondrial polypeptides involved in respiratory electron transport and the citric acid cycle, including Rip1 (a subunit of complex III), Atp2 (a subunit of F1 of complex V), and Mdh1, malate dehydrogenase. Previous studies indicated that supplemented Q6 in coq7 null mutant yeast restored steady-state levels of Atp2, cytochromes c and c1, as well as porin, a mitochondrial outer membrane protein [95]. Exogenously supplied Q is converted to QH2 by the respiratory chain, and QH2 would exert it well known antioxidant effect on the mitochondrial membrane compartment and associated proteins [6]. Endogenous (hydroquinone) Q-intermediates formed after over-expression of Coq8 might also act as antioxidants. It is also possible that exogenous Q restored mitochondrial protein levels by increasing the content of mitochondria in coq null mutants. Q deficiencies may result from mitochondrial mutations affecting other processes; this is consistent with the observed effects of Q deficiency on mitophagy, and the inhibition of mitophagy by Q supplementation [93, 94]. The findings presented here suggest that Q supplementation may correct defects in mitochondrial function through its beneficial effects in stabilizing the CoQ-synthome and de novo biosynthesis of Q, as well as contributing to enhanced respiratory electron transport and mitochondrial metabolism.

Figure 10.

Exogenous Q6 increases the accumulation of 3-hexaprenyl-4-aminophenol (4-AP) in the coq6 null mutant. Lipid extracts were prepared from the cell pellets of coq6 null mutant yeast following growth in YPD with either the presence (+Q6) or absence of Q6 and analyzed by RP-HPLC-MS/MS as described in Fig.9. MRM detected precursor-to-product ion transitions 518.4/122.0 (4-AP) and 455.4/197.0 (Q4). In panel A, the green trace designates the 4-AP signal in the +Q6 condition, and the purple trace designates the 4-AP signal in the absence of added Q6 (coq6Δ). The peak areas of 4AP normalized by peak areas of Q4 are 0.008 in coq6Δ and 2.68 in coq6Δ+Q6. Panel B shows the fragmentation spectrum for the 4-AP [M+H]+ precursor ion (C36H56NO+; monoisotopic mass 518.4), the 4-AP tropylium ion [M]+ (C7H8NO+; 122.06), and the 4-AP chromenylium ion [M]+ (C10H12NO+; 162.1).

Figure 11.

Exogenous Q6 leads to the accumulation of imino-demethoxy-Q6 (IDMQ6) in the coq9 null mutant. Lipid extracts were prepared from cell pellets of the coq9 null mutant yeast following growth in YPD with either the presence (+Q6) or absence of Q6 and analyzed by RP-HPLC-MS/MS as described in Fig. 8. Panel A shows the MRM detected precursor-to-product ion transition 560.5/166.2 (IDMQ6). Panel B, shows the fragmentation spectrum for the IDMQ6 [M+H]+ precursor ion (C38H58NO+; monoisotopic mass 560.4), the IDMQ6 tropylium ion [M]+ (C9H12NO2 +; 166.1), and the IDMQ6 chromenylium ion [M]+ (C12H16NO2 +; 206.1).

Figure 12.

Proposed model for the yeast CoQ-synthome. This model is consistent with co-precipitation studies in S. cerevisiae with tagged Coq polypeptides, and the association of several of the Coq polypeptides in high molecular mass complexes, as assayed in digitonin extracts of mitochondria separated by two-dimensional blue native/SDS PAGE. The over-expression of Coq8, a putative kinase, is required to observe phosphorylated forms of Coq3, Coq5, and Coq7 [31]. Coq10, a START domain polypeptide, binds to Q and is postulated to act as a Q chaperone that delivers Q to the CoQ-synthome and/or the bc1 complex [38]. Coq4 is denoted as a scaffolding protein, with binding sites for Q or polyisoprenyl-intermediates and serves to organize the high molecular mass Q biosynthetic complexes. See text for additional explanation.

Highlights.

Multi-copy Coq8 stabilizes Coq polypeptide complexes in certain coq null mutants.

Exogenous Q6 restored certain Coq polypeptides in select coq null mutants.

Exogenous Q6 promotes synthesis of late-stage coenzyme Q-intermediates.

A model of the CoQ-synthome, multi-subunit Coq polypeptide complex is proposed.

Establishing the subunit interdependence helps elucidate steps in Q biosynthesis.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Chandra Srinivasan, Steve Clarke, and the members of the CF Clarke lab for their advice and input on this manuscript. We thank Drs. A. Tzagoloff (Columbia University) for the cytochrome c1 antibody and the original yeast coq mutant strains, B. Trumpower (Dartmouth College) for the monoclonal antisera to Rip1, and C. M. Koehler (UCLA) for the cytochrome c, cytochrome b2, Hsp60, and Atp2 antibodies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The abbreviations used are: 4-AP, 3-hexaprenyl-4-aminophenol; Coq1, the Coq1 polypeptide; COQ1, designates the wild-type gene encoding the Coq1 polypeptide; coq1, designates a mutated gene; DDMQ6, the oxidized form of demethyl-demethoxy-Q6H2; DMQ6, demethoxy-Q6; DMQ6H2, demethoxy-Q6H2; 4- HB, 4-hydroxybenzoic4-hydroxybenzoic acid (4HB) or para-aminobenzoic acid (pABA) acid; HAB, 3- hexaprenyl-4-aminobenzoic acid; HHAB, 3-hexaprenyl-4-amino-5-hydroxybenzoic acid; HHB, 3- hexaprenyl-4-hydroxybenzoic acid; HMAB, 3-hexaprenyl-4-amino-5-methoxybenzoic acid; 4-HP, 3- hexaprenyl-4-hydroxyphenol; IDMQ6, 4-imino-demethoxy-Q6; MRM, multiple reaction monitoring; pABA, para-aminobenzoic acid; Q, ubiquinone or coenzyme Q; Q6H2, ubiquinol or coenzyme Q6H2; RPHPLC- MS/MS, Reverse phase-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry; START, steroidogenic acute regulatory protein-related lipid transfer.

This work was supported in part by the National Science Foundation Grant 0919609 (C.F.C.), and by National Institutes of Health S10RR024605 from the National Center for Research Resources for purchase of the LC-MS/MS system. C.H.H. was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant T32 GM 008496 and by the UCLA Graduate Division. L.X.X. was supported by Ruth L. Kirschstein National Institutes of Health Service Award GM007185.

REFERENCES

- 1.Crane FL, Barr R. Chemical structure and properties of coenzyme Q and related compounds. In: Lenaz G, editor. Coenzyme Q: Biochemistry, bioenergetics and clinical applications of ubiquinone. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1985. pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turunen M, Olsson J, Dallner G. Metabolism and function of coenzyme Q. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1660:171–199. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Overkamp KM, Bakker BM, Kotter P, van Tuijl A, de Vries S, van Dijken JP, Pronk JT. In vivo analysis of the mechanisms for oxidation of cytosolic NADH by Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondria. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:2823–2830. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.10.2823-2830.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lenaz G, De Santis A. A survey of the function and specificity of ubiquinone in the mitochondrial respiratory chain. In: Lenaz G, editor. Coenzyme Q Biochemistry, Bioenergetics and Clinical Applications of Ubiquinone. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1985. pp. 165–199. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hildebrandt TM, Grieshaber MK. Three enzymatic activities catalyze the oxidation of sulfide to thiosulfate in mammalian and invertebrate mitochondria. The FEBS journal. 2008;275:3352–3361. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bentinger M, Brismar K, Dallner G. The antioxidant role of coenzyme Q. Mitochondrion. 2007;7(Suppl):S41–S50. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montero R, Grazina M, Lopez-Gallardo E, Montoya J, Briones P, Navarro-Sastre A, Land JM, Hargreaves IP, Artuch R, Coenzyme QDSG. Coenzyme Q10 deficiency in mitochondrial DNA depletion syndromes. Mitochondrion. 2013;13:337–341. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emmanuele V, Lopez LC, Berardo A, Naini A, Tadesse S, Wen B, D'gostino E, Solomon M, DiMauro S, Quinzii C, Hirano M. Heterogeneity of coenzyme Q10 deficiency: patient study and literature review. Arch. Neurol. 2012;69:978–983. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2012.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma S, Moon CS, Khogali A, Haidous A, Chabenne A, Ojo C, Jelebinkov M, Kurdi Y, Ebadi M. Biomarkers in Parkinson' disease (recent update) Neurochem. Int. 2013;63:201–229. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fotino AD, Thompson-Paul AM, Bazzano LA. Effect of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on heart failure: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013;97:268–275. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.040741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gasser DL, Winkler CA, Peng M, An P, McKenzie LA, Kirk GD, Shi Y, Xie LX, Marbois BN, Clarke CF, Kopp JB. Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis Is Associated With a PDSS2 Haplotype and Independently, With a Decreased Content of Coenzyme Q10. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2013 doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00143.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tran UC, Clarke CF. Endogenous synthesis of coenzyme Q in eukaryotes. Mitochondrion. 2007;7(Supplement):S62–S71. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pierrel F, Hamelin O, Douki T, Kieffer-Jaquinod S, Mühlenhoff U, Ozeir M, Lill R, Fontecave M. Involvement of Mitochondrial Ferredoxin and Para-Aminobenzoic Acid in Yeast Coenzyme Q Biosynthesis. Chem. Biol. 2010;17:449–459. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y, Hekimi S. Molecular genetics of ubiquinone biosynthesis in animals. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2013;48:69–88. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2012.741564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marbois B, Xie LX, Choi S, Hirano K, Hyman K, Clarke CF. para-Aminobenzoic acid is a precursor in coenzyme Q6 biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:27827–27838. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.151894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ozeir M, Muhlenhoff U, Webert H, Lill R, Fontecave M, Pierrel F. Coenzyme Q biosynthesis: Coq6 is required for the C5-hydroxylation reaction and substrate analogs rescue Coq6 deficiency. Chem. Biol. 2011;18:1134–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xie LX, Ozeir M, Tang JY, Chen JY, Jaquinod SK, Fontecave M, Clarke CF, Pierrel F. Overexpression of the Coq8 kinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae coq null mutants allows for accumulation of diagnostic intermediates of the coenzyme Q6 biosynthetic pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:23571–23581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.360354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marbois B, Gin P, Faull KF, Poon WW, Lee PT, Strahan J, Shepherd JN, Clarke CF. Coq3 and Coq4 define a polypeptide complex in yeast mitochondria for the biosynthesis of coenzyme Q. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:20231–20238. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501315200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marbois B, Gin P, Gulmezian M, Clarke CF. The yeast Coq4 polypeptide organizes a mitochondrial protein complex essential for coenzyme Q biosynthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1791:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsieh EJ, Gin P, Gulmezian M, Tran UC, Saiki R, Marbois BN, Clarke CF. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Coq9 polypeptide is a subunit of the mitochondrial coenzyme Q biosynthetic complex. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007;463:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tauche A, Krause-Buchholz U, Rodel G. Ubiquinone biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: the molecular organization of O-methylase Coq3p depends on Abc1p/Coq8p. FEMS Yeast Res. 2008;8:1263–1275. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2008.00436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marbois BN, Clarke CF. The COQ7 gene encodes a protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae necessary for ubiquinone biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:2995–3004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tran UC, Marbois B, Gin P, Gulmezian M, Jonassen T, Clarke CF. Complementation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae coq7 mutants by mitochondrial targeting of the Escherichia coli UbiF polypeptide: two functions of yeast Coq7 polypeptide in coenzyme Q biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:16401–16409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513267200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leonard CJ, Aravind L, Koonin EV. Novel families of putative protein kinases in bacteria and archaea: evolution of the "eukaryotic" protein kinase superfamily. Genome Res. 1998;8:1038–1047. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.10.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poon WW, Davis DE, Ha HT, Jonassen T, Rather PN, Clarke CF. Identification of Escherichia coli ubiB, a gene required for the first monooxygenase step in ubiquinone biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:5139–5146. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.18.5139-5146.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Do TQ, Hsu AY, Jonassen T, Lee PT, Clarke CF. A defect in coenzyme Q biosynthesis is responsible for the respiratory deficiency in Saccharomyces cerevisiae abc1 mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:18161–18168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100952200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saiki R, Ogiyama Y, Kainou T, Nishi T, Matsuda H, Kawamukai M. Pleiotropic phenotypes of fission yeast defective in ubiquinone-10 production. A study from the abc1Sp (coq8Sp) mutant. Biofactors. 2003;18:229–235. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520180225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lagier-Tourenne C, Tazir M, Lopez LC, Quinzii CM, Assoum M, Drouot N, Busso C, Makri S, Ali-Pacha L, Benhassine T, Anheim M, Lynch DR, Thibault C, Plewniak F, Bianchetti L, Tranchant C, Poch O, DiMauro S, Mandel JL, Barros MH, Hirano M, Koenig M. ADCK3, an ancestral kinase, is mutated in a form of recessive ataxia associated with coenzyme Q10 deficiency. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008;82:661–672. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mollet J, Delahodde A, Serre V, Chretien D, Schlemmer D, Lombes A, Boddaert N, Desguerre I, de Lonlay P, de Baulny HO, Munnich A, Rotig A. CABC1 gene mutations cause ubiquinone deficiency with cerebellar ataxia and seizures. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008;82:623–630. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cardazzo B, Hamel P, Sakamoto W, Wintz H, Dujardin G. Isolation of an Arabidopsis thaliana cDNA by complementation of a yeast abc1 deletion mutant deficient in complex III respiratory activity. Gene. 1998;221:117–125. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00417-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xie LX, Hsieh EJ, Watanabe S, Allan CM, Chen JY, Tran UC, Clarke CF. Expression of the human atypical kinase ADCK3 rescues coenzyme Q biosynthesis and phosphorylation of Coq polypeptides in yeast coq8 mutants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1811:348–360. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin-Montalvo A, Gonzalez-Mariscal I, Padilla S, Ballesteros M, Brautigan DL, Navas P, Santos-Ocana C. Respiratory-induced coenzyme Q biosynthesis is regulated by a phosphorylation cycle of Cat5p/Coq7p. Biochem. J. 2011;440:107–114. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin-Montalvo A, Gonzalez-Mariscal I, Pomares-Viciana T, Padilla-Lopez S, Ballesteros M, Vazquez-Fonseca L, Gandolfo P, Brautigan DL, Navas P, Santos-Ocana C. The phosphatase Ptc7 induces coenzyme Q biosynthesis by activating the hydroxylase Coq7 in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 2013 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.474494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]