Abstract

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of the Cycles Phonological Remediation Approach as an intervention for children with speech sound disorders (SSD). A multiple baseline design across behaviors was used to examine intervention effects. Three children (ages 4;3 to 5;3) with moderate-severe to severe SSDs participated in two cycles of therapy. Three phonological patterns were targeted for each child. Generalization probes were administered during baseline, intervention, and follow-up phases to assess generalization and maintenance of learned skills. Two of the three participants exhibited statistically and clinically significant gains by the end of the intervention phase and these effects were maintained at follow-up. The third participant exhibited significant gains at follow-up. Phonologically known target patterns showed greater generalization than unknown target patterns across all phases. Individual differences in performance were examined at the participant level and the target pattern level.

Learner Outcomes

The reader will be able to: (1) enumerate the three major components of the cycles approach, (2) describe factors that should be considered when selecting treatment targets, and (3) identify variables that may affect a child’s outcome following cycles treatment

Keywords: cycles approach, phonological intervention, speech sound disorder, children

1. Introduction

The Cycles Phonological Remediation Approach (Hodson & Paden, 1991; Hodson, 2010; Prezas & Hodson, 2010) is a prominent intervention method for treating severe speech sound disorders (SSD) in preschool and school age children. Not only is it one of the most frequently implemented phonological methods in clinical practice (Rvachew, Nowak, & Cloutier, 2004), but it has also been accepted as a standard method for treating SSDs in research studies. In particular, it has been combined with stuttering therapy (Conture, Louko, and Edwards, 1993), phonological awareness intervention (Gillon, 2005), and speech perception and stimulability training (Rvachew, Rafaat, and Martin, 1999, Study 2) in studies investigating subpopulations and sucharacteristics of children with SSDs.

The major components of the cycles approach were derived from principles of developmental phonology, cognitive psychology, and research in phonological acquisition (see Hodson, 2010, p. 109). These principles led to the hypothesis that children with SSDs would benefit most from a program that included (1) pattern-focused selection of intervention targets and stimuli, (2) cyclical targeting of problematic patterns, and (3) use of focused auditory input in combination with production-practice activities during treatment sessions. Hodson (e.g., Hodson & Paden, 1991) strongly emphasizes that all three of these components are essential aspects of cycles therapy. Previous experimental studies exploring the efficacy of the cycles approach have used modified versions of this treatment method (see Baker & McLeod, 2011). These modifications have involved the elimination or substantial alteration of one or more of the three principal components, and no two studies have implemented the same treatment procedures. Clinicians interested in using the cycles approach are faced with the difficult choice of either attempting to implement one of the several cycles modifications for which efficacy has been established, or using the approach as described by Hodson knowing that it has not been fully validated within the context of an experimental design. The decision is further complicated by the fact that the details of the modifications are not always reported in published studies, whereas Hodson has articulated her methods in books, book chapters, and manuscripts, removing much of the guesswork for clinical professionals.

This study aimed to provide preliminary evidence for the efficacy of the cycles approach as described by Hodson and colleagues using an experimental single-subject research design. In particular, we examined whether the combination of pattern-based target selection, cyclical treatment, focused auditory input, and production-practice activities would result in generalization of trained sounds to non-treatment stimuli. In this way, we endeavored to make evidence-based practice more accessible for professionals intending to use the unmodified cycles approach in clinical practice.

1.1. Previous research

A recent review (Baker & McLeod, 2011) identified only four studies that examined the efficacy of cycles-based procedures in experimental or quasi-experimental designs. Tyler, Edwards, and Saxman (1987) compared the cycles approach to the minimal pairs procedure in a multiple probe AB design. Four participants were assigned to one of the two intervention methods based on the nature and severity of their errors. For the cycles group, therapy targets were selected according to Hodson’s recommendations, treatment sounds were presented in facilitative phonetic environments, each participant received at least two cycles of therapy, and sessions consisted of auditory bombardment with production-practice activities. The only modification from the original cycles protocol involved discontinuing treatment of certain sounds (or patterns) if they were incorrect more than 50% of the time, and substituting less problematic targets in their place. The authors found that both intervention methods resulted in improvements for targets over non-targets, but that cycles resulted in remediation of three to five processes in the time it took to remediate one process with the minimal pairs procedure.

Tyler and Watterson (1991) used a between-subjects design with semi-random allocation to compare the efficacy of the cycles approach to that of a script-based language intervention approach in children who exhibited both language and speech sound disorders. These researchers modified the cycles approach to fit the study’s group treatment design. Modifications included targeting processes that were not characteristic of all participants and use of non-focused auditory bombardment. The children participated in only one cycle of therapy; therefore, problematic patterns were not recycled for additional treatment. These researchers found no significant differences between pre- and post-treatment measures of consonant accuracy (i.e., percentage consonants correct in single words) for either experimental group.

Almost and Rosenbaum (1998) examined the efficacy of phonological intervention in a randomized controlled trial. Thirteen participants were assigned to an immediate treatment group and thirteen to a delayed treatment group. The authors reported using a modification of the cycles approach when scheduling treatment of target patterns; however, other aspects of treatment were not cycles-specific. After four months of intervention, the immediate treatment group showed significantly greater accuracy in both single word and conversational contexts than the delayed treatment group suggesting that treatment resulted in meaningful improvements in speech sound accuracy.

Using a within-subjects design, Rvachew and colleagues (1999) examined whether progress and improvement during cycles treatment might be affected by individual differences in stimulability and speech perception ability. Because the authors were primarily concerned with these two characteristics, the unit of observation was individual sounds rather than individual children. As a result, the treatment protocol was modified from the original cycles approach – only one training sound was selected to teach each target pattern. Over 50% of stimulable sounds and over 60% of well-perceived sounds showed improvement; however, unstimulable sounds and poorly perceived sounds showed little improvement. Their results indicate that speech perception and stimulability may play a role in intervention progress.

The results of these four studies appear quite mixed with two suggesting little to no improvement following cycles training and two indicating that the cycles approach facilitates large and significant improvements in speech sound accuracy. Methodological differences across the studies could explain, to some degree, the variability in observed outcomes. For example, the number of sessions per participant ranged from 9 to 29, some studies used group therapy while one-on-one therapy was provided in others, and the outcome measures were different in each case (e.g., percentage occurrence of phonological processes vs. percentage consonants correct vs. performance on an articulation test). Furthermore, each study implemented a ‘modified’ version of the cycles approach. As the components of an intervention method are modified, the underlying nature of the method is also modified. For example, Stoel-Gammon and colleagues (2002) suggest that teaching only one sound per process changes an approach from one that is pattern-based to one that is phoneme-based. As a result, the successes and failures noted in previous studies may be attributable to study-specific intervention procedures rather than to the cycles approach itself – a valid concern for professionals interested in implementing the cycles approach as described by Hodson (e.g., Hodson, 2010).

1.2. Evidence from non-experimental case studies

Baker and McLeod (2011) identified ten non-experimental case studies that have employed the cycles approach. Three of these have modified the approach (Culatta, Setzer, & Horn, 2005; Harbers, Paden, & Halle, 1999; Mota, Keske-Soares, Bagetti, Ceron, & Melo Filha, 2007), while seven have fully implemented the approach as described by Hodson. Among the latter group, two included children with additional deficits such as cleft palate (Hodson, Chin, Redmond, & Simpson, 1983) and hearing impairment (Gordon-Brannan, Hodson, & Wynne, 1992) and two others presented preliminary evidence for a tool that could be used to assess client progress during phonological intervention (Glaspey & Stoel-Gammon, 2005; Glaspey & Stoel-Gammon, 2007). The remaining three case studies focused on the facilitative effects of the cycles approach for children with isolated SSDs (Hodson, 1983; Hodson, Nonomura, & Zappia, 1998; Montgomery & Bonderman, 1989). The children in these studies exhibited various degrees of phonological improvement after a year or more of treatment often progressing from ratings of ‘severe’ or ‘profound’ to ratings of ‘mild’ or ‘moderate’. These case studies provide preliminary evidence for the effectiveness of the cycles approach and set the groundwork for future experimental studies.

The purpose of the current study was to experimentally evaluate the unmodified cycles approach as an intervention for preschool-age children with severe SSDs. To meet standards for high quality treatment research, we followed the Certainty of Evidence Framework (Simeonsson & Bailey, 1991), which includes criteria for interrater reliability and treatment integrity. Because we employed a single subject experimental design, we could examine the pattern of learning for each participant and investigate individual differences in performance and outcomes. We were interested in identifying not only the short-term effects of using the unmodified approach, but the long-term effects as well. In particular, we asked the following: (1) does target pattern accuracy improve within two cycles of therapy, and (2) are the positive effects of the intervention maintained after treatment is discontinued? By answering these questions, we looked to provide professionals with experimental findings to support the decision whether or not to use an unmodified cycles approach in clinical practice.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

This research was approved by the institutional review board of the authors’ university. Three children (2 males, 1 female) aged 4;3, 4;5, and 5;3, participated in this study. Each child exhibited a moderate-severe or severe SSD characterized by three or more phonological processes. In addition, the participants were monolingual speakers of English and exhibited: (1) normal hearing acuity as measured through a conditioned response to 20 dB HL pure tones at 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz; (2) typical oral motor structure and function according to a screening tool developed by Robbins and Klee (1987); (3) cognitive function and language comprehension skills within normal limits based on a standard score of 85 or above on the Columbia Mental Maturity Scale (CMMS; Burgemeister, Blum, & Lorge, 1972) and the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals – Preschool 2 Receptive Language Index (CELF:P-2, RLI; Semel, Wiig, & Secord, 2004); and (4) a non-autistic rating (15–27.5) on The Childhood Autism Rating Scale - 2 (CARS-2; Schopler, Van Bourgondien, Wellman, & Love, 2010). Table 1 summarizes the participant characteristics. Two of the participants had previously received speech and/or language services, but none of the participants were receiving services during the intervention phase of this study.

Table 1.

Pre-Treatment Characteristics of Study Participants

| Subject | Age (Yrs;Mos) | Oral Motor Structurea | Oral Motor Functiona | CMMSb (SS) | CELF-P:2c (SS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| William | 4;5 | 24 | 78 | 100 | 107 |

| Cassidy | 5;3 | 22 | 79 | 134 | 105 |

| Henry | 4;3 | 23 | 77 | 104 | 95 |

Raw scores are reported for Oral Motor Structure and Function. The maximum score for the Structure score is 24. The maximum score for the Function score is 84.

CMMS = Columbia Mental Maturity Scale

CELF-P:2 = Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals-Preschool 2, Receptive Language Index

2.2. Experimental design

A single-subject multiple baseline design (MBD) across behaviors (Baer, Wolf, & Risley, 1968) was implemented. Within a MBD across behaviors, three or more behaviors are selected and the independent variable, or target intervention, is successively applied to each behavior. Experimental control is established when an individual’s performance improves for behaviors that are being treated, but remains stable for those behaviors that have not yet been treated.

In this study, phonological patterns served as the behaviors. The treatment protocol for the cycles approach requires that new patterns be targeted before old patterns are fully learned (Hodson, 2010). As a result, progression of treatment from one behavior to the next was time-based rather than criterion-based. Each baseline was examined for a stable or downward trend before the next pattern was treated.

2.3. Therapy schedule

This study consisted of three phases: (1) baseline, (2) intervention, and (3) follow-up. The baseline and follow-up phases each required a minimum of three sessions and the intervention phase required 18 sessions. Following the procedures of Tyler et al. (1987), each child received two cycles of therapy (hereafter cycle I and cycle II) and each cycle was three weeks long. Cycle I and cycle II were separated by a one-week break. The sessions were approximately one hour in length and took place three times per week at the university speech and hearing clinic. A different pattern was targeted each week and a different sound every session. Thus, during one cycle of therapy, each pattern was targeted for three hours with each sound being the focus of at least one 60-minute session. All treatment was provided by the first author who is a licensed and certified Speech-Language Pathologist. Baseline data were collected the week before intervention began and follow-up data were collected two months after intervention was completed.

2.4. Target selection

Using Hodson’s distinctions (e.g., Hodson, 1983), we refer to the children’s systematic sound errors (e.g., fronting, gliding, and stopping) as phonological processes, and the classes of sounds treated in therapy (e.g., velars, liquids, and consonant clusters) as phonological patterns. Detailed phonological analyses were completed for the participants based on their production of the 50 single words from the Hodson Assessment of Phonological Patterns – Third Edition (HAPP-3; Hodson, 2004). This analysis is summarized in Table 2. Selection of three target phonological patterns was based on the suggestions provided by Hodson and Paden (1991). Considerations included: (1) developmental appropriateness (i.e., primary targets vs. secondary targets), (2) percentage of occurrence of 40% or higher, and (3) effect of the associated process on child intelligibility (Tyler et al., 1987). At least two sounds were chosen to represent each pattern based on clinical recommendations provided by Hodson (2010). Order of treatment was primarily dictated by the experimental design; however, developmental appropriateness, percentage of occurrence, and effect on intelligibility were also considered when possible. Target processes, patterns, and sounds for each participant are summarized below. Unless otherwise specified, the same sounds were used during cycle I and cycle II.

Table 2.

Pre-treatment Phonological Analysis by Participant

| Participant | Sex | Age | Severity | Absent from Inventory | Phonological Processesa | Affected Sounds |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| William | M | 4;5 | Mod-severe | f, v, θ, ð, ʒ, ʤ, r | Cluster reduction* | sp, st, sk, sm, sn, sw, sl, pl, bl, kl, gl, fl, tr, dr, kr, gr, θr |

| Gliding* | l, r | |||||

| Fricative alveolarization* | f, v, θ, ð, ʃ, ʒ, ʧ, ʤ | |||||

| Cassidy | F | 5;3 | Severe | k, g, ŋ, f, v, θ, ð, s, z, ʃ, ʒ, ʧ, ʤ, r, initial clusters | Cluster reduction* | sp, st, sk, sm, sn, sw, sl, pl, bl, kl, gl, fl, br, tr, dr, kr, gr, θr |

| Stopping* | f, v, θ, ð, s, z, ʃ, ʒ, ʧ, ʤ | |||||

| Fronting* | k, g, ŋ | |||||

| Gliding | l, r | |||||

| Henry | M | 4;3 | Severe | m, n, ŋ, f, v, θ, ð, ʃ, ʒ, ʤ, r, w, h, initial clusters | Cluster reduction* | sp, st, sk, sm, sn, sw, sl, pl, bl, kl, gl, fl, br, tr, dr, kr, gr, θr |

| Stopping | f, v, θ, ð, s, z, ʃ, ʒ, ʧ, ʤ | |||||

| Fronting | k, g | |||||

| Regressive assimilation* | initial b, p, t, k, g, m, n, f, v, θ, s, z, w, j, h, l, r | |||||

| Nasal omission* | m, n, ŋ |

All processes listed occurred with a frequency of 40% or higher. Processes marked with an asterisk were targeted during the intervention phase of the study

2.4.1. William

William exhibited two primary processes, cluster reduction and gliding, and one secondary process, fricative alveolarization, that is, producing all fricatives with an alveolar place of articulation (i.e., as /s/ or /z/). Cluster reduction was targeted first using /s/ clusters including initial /sp/, /st/, and /sk/. Fricative alveolarization was targeted second using non-alveolar fricative consonants including initial /f/, final /f/, and final /v/. Gliding was targeted last using liquid consonants including initial /l/, medial /l/, and initial /r/.

2.4.2. Cassidy

Cassidy exhibited four primary processes – cluster reduction, stopping, fronting, and gliding. Cluster reduction, stopping, and fronting were selected for therapy because these processes were the most prevalent in her speech and had the greatest impact on her intelligibility. Cluster reduction was targeted first using /s/ clusters including initial /sp/, /st/, and /sn/. Fronting was targeted second using velar consonants including final /k/, initial /k/, and initial /g/. Stopping was targeted last using final fricatives including final /ps/, /ts/, and /ks/ during cycle I and, after Cassidy exhibited some level of proficiency with these clusters, final /s/ and ‘sh’ during cycle II (Hodson, 2010, Hodson & Paden, 1991).

2.4.3. Henry

Henry exhibited five phonological processes; four of these – cluster reduction, stopping, fronting, and absence of nasal consonants (hereafter referred to as nasal omission) – are considered primary processes. The fifth process, regressive assimilation, is characterized as a secondary process; however, Henry’s phonological behavior reflected an inability to distinguish differences in place of articulation within single words (e.g., duck became /gΛ k/ and cat became /tæt/). Hodson and Paden (1991) suggest that contrasting anterior and posterior consonants is an essential and fundamental part of phonological development. Because of the high prevalence of this behavior and its remarkable effect on Henry’s intelligibility, regressive assimilation was chosen for treatment as well as nasal omission and cluster reduction. Nasal omission was targeted first using nasal consonants including initial /m/, final /m/, and final /n/. Regressive assimilation was targeted second using anterior-posterior contrasts including initial /p/ with final /t/ or /k/, initial /b/ with final /t/ or /k/, and initial /k/ with final /p/ or /t/. Cluster reduction was targeted last using /s/ clusters including /sp/, /st/, and /sk/.

2.5. Generalization probe

Participant progress was monitored using a generalization probe that was administered at the end of every session in the form of a single word elicitation task. The probe consisted of twenty-seven real words (i.e., nine per target process). Each word contained a sound that had been chosen for treatment. All words included one of the following phonetic patterns: CV/r/ or /r/VC where C represents the affected consonant and V represents any vowel. The phoneme /r/ was chosen as a constant due to its vowel-like qualities and unique articulatory placement. See Appendix A for a list of probe target patterns, sounds, and words. Many of the probe words are typically acquired in later childhood or adulthood and, therefore, were likely to be equivalent to non-words for our preschool-age participants. Note that /r/ was sometimes presented within the context of a cluster. The probe words were randomized to create three lists for each child. A different randomization of the list was used each day within the same week. None of the probe words were targeted in therapy activities.

The generalization probe words were elicited by the treating clinician through a direct imitation task, which has been used previously in research investigating the effects of SSD intervention (Powell & Elbert, 1984). During the probe task, the child was presented with an orthographic representation of each word and asked to say what the clinician said. No feedback was provided and the words were elicited in rapid succession.

2.6. Treatment procedures

All experimental sessions followed the format specified by Hodson and colleagues (Hodson, 2010; Hodson & Paden, 1991; Prezas & Hodson, 2010) and included review practice, auditory bombardment, stimulability practice, card coloring, production-practice activities, and phonological awareness. The overall goal of treatment was to facilitate errorless production of speech sounds; therefore, the clinician provided corrective feedback in the form of explicit verbal and visual cues as well as models when needed. The words used during intervention activities were chosen based on phonetic environment and age appropriateness. Homework was provided at the end of the week and was implemented with a compliance rate of 100% by all but Henry’s mother whose compliance rate was 70%.

During the baseline and follow-up sessions, the clinician facilitated therapeutic activities before administering the generalization probe to make these phases as similar to the intervention phase as possible. The ‘target’ sounds for these sessions were already correctly produced by the participants and were distinct from those under investigation. For William and Cassidy, the target sound for the baseline and follow-up phases was initial /p/. For Henry, the target sound was initial /t/.

2.7. Dependent measure

The primary measure of interest was the number of target sounds that were correctly produced during the generalization probe. A response was considered correct if the target sound in the word was accurate even if the remaining sounds were produced incorrectly. Generalization probe scores were graphed using Microsoft© Excel.

2.8. Additional measures

2.8.1. Clinical significance

A clinically significant improvement is one that is “sufficient enough to change the professional’s clinical description of, or clinical label for, a client” (Bothe and Richardson, 2011, p. 236). In this study, clinical significance was assessed through two measures that were calculated from participant productions of the 50 words from the HAPP-3, administered before baseline and after cycle II. These measures included Percentage Consonants Correct (PCC; Shriberg & Kwiatkowski, 1982) and phonological process percentage of occurrence.

PCC is a general measure of speech sound accuracy that correlates highly with clinical ratings of SSD severity. PCC scores fall into the following categories: (1) <50% is associated with a severe disorder, (2) 50% to 65% is associated with a moderate-severe disorder, (3) 65% to 85% is associated with a mild-moderate disorder, and (4) 85% to 100% is associated with a mild disorder (Shriberg & Kwiatkowski, 1982). For the current study, change on this measure was considered clinically significant if (1) severity rating improved and/or (2) accuracy increased by 15% or more.

Phonological process percentage of occurrence provides insight into the status of a child’s phonological system – the higher the percentage the more ingrained the process is likely to be and the more difficulty the child will have overcoming the process independently. Hodson (2010) indicates that processes occurring with a frequency of less than 40% do not need to be targeted in future cycles. We used this cutoff as our criterion of clinically significant improvement on this measure.

2.8.2. Social validity

In this study, parent perception of the cycles approach was assessed using a revised version of the Treatment Acceptability Rating Form (TARF; Reimers & Wacker, 1988). The TARF-Revised (TARF-R) included a series of questions related to the perceived effectiveness and disadvantages of the approach, the level of caregiver approval for the intervention method, and the degree of child improvement. Parents answered the questions using a one-to-five Likert-type scale (1 = low, 5 = high). This questionnaire was administered at the end of the follow-up phase of the study.

2.9. Data analysis

Three methods of analysis were used to compare participant performance on the generalization probe across baseline, cycle I, cycle II, and follow-up. The first method, visual analysis, is standard practice for single subject experimental research; however, the results of visual analysis tend to be subjective. Thus, in addition to visual analysis, effect size estimates were calculated to provide objective and quantifiable evidence of participant improvement, and All Pair-wise Comparisons for Unequal Group Sample Sizes (Dunn, 1964) was used to statistically evaluate the degree of change across the phases of the study.

2.9.1 Visual analysis

Visual analysis was performed using the four-step process proposed by Kratochwill and colleagues (2010). First, we inspected baseline data to ensure a stable pattern of performance was established. Second, the level (mean), trend (slope), and variability (standard deviation) of the data within each experimental phase were determined. Third, the immediacy of effect, overlap, and consistency of data between and across phases were identified. Finally, the collected information was integrated to assess whether three demonstrations of the effect occurred across three different phase repetitions, which would confirm a causal relationship between the intervention and the outcomes.

2.9.2. Effect size estimates

Intervention effects for each behavior were evaluated using Percentage of Non-overlapping Data (PND; Scruggs, Mastropieri, & Casto, 1987). This metric is calculated by determining the number of data points in the intervention phase which exceed the highest data point in baseline and dividing this number by the total number of intervention data points. This yields a proportion of non-overlapping data points which can be interpreted as follows: scores above 90% indicate high level effectiveness, those between 70% and 90% indicate a fair effectiveness, those between 50% and 70% represent questionable effectiveness, and scores below 50% indicate unreliable effectiveness (Scruggs, Mastropieri, Cook, & Escobar, 1986).

2.9.3. Phase comparisons

All Pair-wise Comparisons for Unequal Group Sample Sizes (Dunn, 1964) was selected to compare performance across phases. A SAS® macro was programmed to make six key comparisons at an alpha level of .05 and to flag significant differences across phases (modified from Juneau, 2004). These comparisons included: (1) baseline vs. cycle I, (2) baseline vs. cycle II, (3) baseline vs. follow-up, (4) cycle I vs. cycle II, (5) cycle I vs. follow-up, and (6) cycle II vs. follow-up.

2.10. Analyses of phonological knowledge

Dinnsen and colleagues (e.g., Dinnsen & Elbert, 1984) proposed that greater generalization should be observed for phonologically known targets than for targets that are phonologically unknown. Phonological knowledge was assessed using the results from the HAPP-3 at baseline, after cycle I, and after cycle II according to the conventions described by Gierut et al. (1987). A target pattern was categorized as ‘known’ if at least one target sound in the pattern was known and categorized as ‘unknown’ if no target sounds were known. Mann-Whitney U tests (Mann & Whitney, 1947) were used to compare across-participant accuracy for known vs. unknown patterns during cycle I, cycle II, and follow-up.

2.11. Interrater Reliability

A certified Speech-Language Pathologist, trained in transcription of children with language and SSDs, served as an independent and blinded observer to determine interrater reliability (IRR) for the collected data. She was familiarized with the scoring procedure and evaluated 25% of the generalization probes for all participants (i.e., six sessions per participant or 24 sessions total). Probes were randomly selected and proportionally distributed across baseline, intervention, and follow-up phases. Scoring agreements and disagreements were tallied. IRR was calculated by dividing the number of scoring agreements by the total number of opportunities for agreement. IRR was 92% for William’s data, 97% for Cassidy’s data, and 94% for Henry’s data.

2.12. Treatment Integrity

A second certified Speech-Language Pathologist who specializes in treatment of children with SSDs served as an additional independent observer to determine integrity of treatment implementation (TI). She was given a detailed description of session activities (modified from Prezas and Hodson, 2010) and a checklist to identify the number of steps completed during each treatment session. Twenty-eight percent of the treatment sessions were randomly selected for analysis (i.e., five sessions per participant or 20 sessions total). TI was calculated by dividing the number of steps implemented by the total number of steps possible and multiplying by 100. TI was 100% for each participant.

3. Results

Results are reported individually for each participant. Graphs contain data from the generalization probes and display participant performance throughout the three experimental phases. Raw scores (range 0–9) were graphed and the following conventions were established for visual analysis based on clinical perception of improvement: scores from 0 to 3 indicated low-level accuracy, from 3 to 6 indicated mid-level accuracy, and from 6 to 9 indicated high-level accuracy. For those children who showed little improvement within a particular pattern, data points reflecting target sound accuracy during review practice were also graphed for comparison.

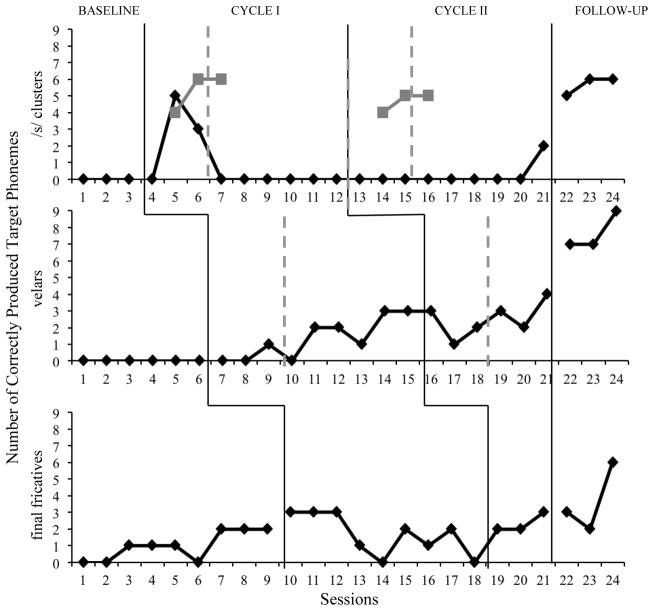

3.1. William

3.1.1. Baseline

A graphic display of William’s data is shown in Figure 1 and the descriptive statistics for his performance are summarized in Table 3. Mean accuracy levels were low for all targeted patterns during baseline. In addition, all three baselines were either stable or trended downward and variability was minimal.

Figure 1. William’s generalization probe data.

Diamond data points represent number of correct target phonemes produced in untrained words. Scores range from 0 to 9 for each target process. Each phase of the study is demarcated by solid lines. Direct treatment of individual target patterns occurred during the three sessions preceding the dashed line in each cycle.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics and Effect Size Estimate for William

| S-Clusters | Non-alveolar Fricatives | Liquids | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Accuracy (SD)a | |||

| Baseline | 1.0 (1.0) | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.9 (0.9) |

| Cycle I | 6.4 (1.9) | 1.8 (1.2) | 1.7 (1.9) |

| Cycle II | 8.7 (0.5) | 3.2 (0.4) | 5.0 (0.0) |

| Follow-up | 6.0 (1.0) | 1.7 (1.2) | 5.0 (1.0) |

| Percentage Non-overlapping Data (%) | |||

| Cycle I | 100 | 66.7 | 66.7 |

| Cycle II | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Follow-up | 100 | 33.3 | 100 |

Raw scores are reported. The maximum possible score is 9.

3.1.2. Intervention

Accuracy of /s/ clusters (behavior 1) trended upward during cycle I and stabilized at a high-level during cycle II. Improvement was immediate with no overlap between baseline and intervention. Non-alveolar fricatives (behavior 2) showed no initial improvement, but accuracy trended gradually upward during cycle I and stabilized at mid-level during cycle II. For the third pattern, liquids (behavior 3), gradual but steady improvement was observed. Accuracy stabilized at mid-level during cycle I and remained stable during cycle II. PND scores corroborate these observations. Only /s/ clusters showed consistent performance above baseline in cycle I, whereas all three patterns showed consistent improvement over baseline in cycle II. The results from the phase comparisons (see Table 6) indicate that accuracy of target patterns significantly increased during cycle I and that these improvements were maintained in cycle II. The change in performance from cycle I to cycle II approached significance indicating that William continued to show progress during cycle II.

Table 6.

Phase Comparisons for All Participants

| Comparison | William | Cassidy | Henry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline vs. Cycle I | X | ||

| Baseline vs. Cycle II | X | X | |

| Baseline vs. Follow-up | X | X | X |

| Cycle I vs. Cycle II | X | ||

| Cycle I vs. Follow-up | X | X | |

| Cycle II vs. Follow-up | X |

Note. X = indicates significant improvement between phases (p ≤ 0.05).

3.1.3. Follow-up

At follow-up, William exhibited mid-level accuracy for /s/ clusters and liquids, but baseline levels of accuracy for non-alveolar fricatives. PND results indicate that production of /s/ clusters and liquids was consistently above baseline levels at follow-up, but production of non-alveolar fricatives was unstable. Despite reduced accuracy of non-alveolar fricatives, performance during follow-up was significantly better than performance during baseline and not significantly different from performance during cycle II (see Table 6).

3.2 Cassidy

3.2.1. Baseline

A graphic display of Cassidy’s performance is shown in Figure 2 and descriptive statistics are summarized in Table 4. Cassidy exhibited stable, low-level baselines for /s/ clusters (behavior 1) and velars (behavior 2). Accuracy for final fricatives (behavior 3) showed a gradual upward trend, but stabilized at a low level before intervention was implemented.

Figure 2. Cassidy’s generalization probe data.

Diamond data points represent number of correct target phonemes produced in untrained words. Scores range from 0 to 9 for each target process. Square data points represent number of correct target phonemes produced in trained words during Review Practice. Scores range from 0 to 6. Each phase of the study is demarcated by solid lines. Direct treatment of individual target patterns occurred during the three sessions preceding the dashed line in each cycle.

Table 4.

Descriptive Statistics and Effect Size Estimate for Cassidy

| S-Clusters | Velars | Final Fricatives | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Accuracy (SD)a | |||

| Baseline | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 1.0 (0.9) |

| Cycle I | 0.9 (1.8) | 1.3 (1.2) | 1.8 (1.3) |

| Cycle II | 0.2 (0.7) | 2.5 (1.1) | 2.3 (0.6) |

| Follow-up | 5.7 (0.6) | 7.7 (1.2) | 3.7 (2.1) |

| Percentage Non-overlapping Data (%) | |||

| Cycle I | 22.2 | 66.7 | 44.4 |

| Cycle II | 11.1 | 100 | 33.3 |

| Follow-up | 100 | 100 | 66.7 |

Raw scores are reported. The maximum possible score is 9.

3.2.2. Intervention

Accuracy of /s/ clusters (behavior 1) showed immediate improvement after the first session, however, this level was not maintained when a different pattern became the focus of treatment (session 7). Accuracy of /s/ clusters remained at baseline levels throughout the rest of cycle I and cycle II with a slight upward trend during the last intervention session. Data points reflecting accuracy during review practice indicate that Cassidy was able to produce /s/clusters during treatment in carefully selected words, but did not generalize accurate production to the generalization probe words. Accuracy of velars (behavior 2) showed a delayed, but upward trend during cycle I. Performance during cycle II was variable, but remained slightly above baseline levels. Accuracy of final fricatives (behavior 3) initially improved, but performance became variable and declined when a new pattern was targeted (session 13). An increasing trend was noted during cycle II. Overall, Cassidy’s performance indicated that she was able to produce the targeted sounds, but became inconsistent when sufficient structure and support were not available. PND scores indicate that only velar consonants showed consistent improvement over baseline by the end of cycle II. No significant improvements were made between baseline and intervention or between cycle I and cycle II (see Table 6).

3.2.3. Follow-up

Cassidy’s follow-up data indicate that production of /s/ clusters and final fricatives increased to mid-level accuracy and production of velars increased to high-level accuracy. Follow-up PND scores reveal that accuracy was consistently above baseline levels for both /s/ clusters and velars, though not for final fricatives. Phase comparisons identified significant change between baseline and follow-up, cycle I and follow-up, and cycle II and follow-up which suggests that the greatest change occurred during the period between cycle II and follow-up.

3.3. Henry

3.3.1. Baseline

A graphic display of Henry’s performance is shown in Figure 3 and descriptive statistics can be found in Table 5. During the baseline phase, accuracy for all three target patterns was low-level and stable.

Figure 3. Henry’s generalization probe data.

Diamond data points represent number of correct target phonemes produced in untrained words. Scores range from 0 to 9 for each target process. Square data points represent number of correct target phonemes produced in trained words during Review Practice. Scores range from 0 to 6. Each phase of the study is demarcated by solid lines. Direct treatment of individual target patterns occurred during the three sessions preceding the dashed line in each cycle.

Table 5.

Descriptive Statistics and Effect Size Estimate for Henry

| Nasals | Anterior-Posterior Contrasts | S-Clusters | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Accuracy (SD)a | |||

| Baseline | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.5 (0.6) | 0.1 (0.3) |

| Cycle I | 0.7 (0.7) | 2.0 (1.2) | 0.3 (0.5) |

| Cycle II | 4.7 (1.3) | 4.5 (0.6) | 0.3 (0.6) |

| Follow-up | 6.7 (0.6) | 8.3 (0.6) | 2.7 (1.2) |

| Percentage Non-overlapping Data (%) | |||

| Cycle I | 55.6 | 66.7 | 0 |

| Cycle II | 100 | 100 | 0 |

| Follow-up | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Raw scores are reported. The maximum possible score is 9.

3.3.2. Intervention

Accuracy of nasals (behavior 1) was low-level and variable throughout cycle I. However, during cycle II, immediate improvement and an upward trend were noted followed by stable mid-level performance. A similar pattern was observed for anterior-posterior contrasts (behavior 2). Performance for /s/ clusters (behavior 3) remained at baseline levels throughout the intervention phase. Data from review practice indicate that Henry was able to produce /s/ clusters in trained words during treatment, but was unable to generalize accurate production to the probe words. PND scores for both nasals and anterior-posterior contrasts indicate that performance in cycle II was consistently above baseline. Phase comparisons (see Table 6) reveal that performance during cycle II was significantly better than performance during baseline and cycle I.

3.3.3. Follow-up

At follow-up, accuracy of nasal consonants and anterior-posterior contrasts increased to high-level accuracy. Accuracy of /s/ clusters increased slightly, but remained low-level. PND scores suggest that performance for all three target patterns was consistently above baseline levels at follow-up. Phase comparisons corroborate these results – performance during follow-up was significantly better than performance during baseline and cycle I. The change from cycle II to follow-up, however, was not significant.

3.4. Phonological knowledge

The results of the phonological knowledge analysis revealed that William knew two out of three patterns at baseline (/s/ clusters, liquids) and learned the third pattern by the end of cycle I (non-alveolar fricatives). Cassidy knew no patterns at baseline, but learned one pattern by the end of cycle I (/s/ clusters), and a second pattern by the end of cycle II (velars). Henry similarly knew no patterns at baseline, but acquired knowledge of two patterns by the end of cycle I (nasals, anterior-posterior contrasts). He did not acquire knowledge of the third pattern during the intervention period. Generalization of known patterns was significantly greater than generalization of unknown patterns during cycle I (Z = 5.70, p < .001), cycle II (Z = 2.95, p = .003), and follow-up (Z = 2.45, p = .014).

3.5. Clinical significance

Pre- and post-treatment PCC and percentage of occurrence are reported in Table 8. PCC increases of 15% or more were observed for both William and Henry. This change resulted in a milder severity rating for William. Cassidy exhibited only slight improvement on this measure. Percentage of occurrence decreased for all target processes. Notably, occurrence decreased by almost half for one of William’s processes and by more than half for one of Henry’s processes resulting in a frequency of occurrence of 43% in both cases. This value approaches Hodson’s (2010) 40% criterion for discontinued treatment. Remediated processes included fricative alveolarization for William and regressive assimilation for Henry.

3.6. Social validity

The parents of all participants provided high ratings for this approach suggesting that they found it very acceptable (M = 5) and effective (M = 5), easy to understand (M = 4), and very likely to make permanent improvements in the speech of their children (M = 5). They further specified that disadvantages and negative effects were unlikely (M = 1.7) and that their children were more intelligible post-treatment (M = 3.7) than pre-treatment (M = 2.3). These results indicate that parents recognized the progress their children had made during treatment and felt that these improvements were maintained after a two-month period without cycles intervention.

4. Discussion

Two out of three preschool-age children with moderate-severe to severe SSDs exhibited statistically and clinically significant improvements in speech sound production after 18 hours, or two cycles, of treatment using the Cycles Phonological Remediation Approach. Target sound accuracy was stable or improved for all three children after two months without cycles treatment indicating that the effects of the approach were enduring. These results generally support the efficacy of the cycles approach for children with SSDs; however, clinicians considering whether or not to use this approach must keep in mind certain limitations of the method as well as individual differences across participants and target patterns that were observed in this study.

4.1. Limitations of the cycles approach

One of the key components of cycles approach is pattern-focused target selection. In this study, the typical error descriptions (e.g., fronting, backing, gliding, cluster reduction, etc.) did not always adequately represent the processes that were prevalent in the speech of our participants. Some atypical examples include William’s tendency to produce all fricatives as alveolar sounds and Henry’s tendency to assimilate initial consonants with final consonants. In these cases, it may have been more appropriate to use other approaches, such as multilinear analysis (Rvachew & Brousseau-Lapre, 2012), to characterize the errors.

A second key component of the cycles approach is cyclical targeting of problematic patterns, which requires treating a new sound or pattern every few sessions regardless of child proficiency. This goal attack strategy achieved rapid results for William and Henry, that is, significant improvements were observed for at least two of their patterns after only two cycles of therapy. However, it may have been too taxing for Cassidy’s phonological system. Figure 2 indicates that Cassidy was experiencing treatment effects for /s/ clusters and final fricatives, that is, her accuracy increased when these patterns were directly targeted, but showed a noticeable decline when new patterns became the focus of treatment. If these patterns had been targeted until Cassidy achieved a certain level of stability, they may have shown greater generalization during the intervention phase.

4.2. Participant-level differences

According to the recommendations of the authors (e.g., Hodson & Paden, 1991), the children selected to participate in this study were good candidates for cycles treatment. They exhibited severe or borderline severe SSDs that greatly reduced their intelligibility even among familiar listeners. Furthermore, they exhibited multiple phonological processes, which were highly prevalent in their speech occurring with a frequency of more than 60%. Despite meeting these qualifications, William and Henry make statistically significant gains during the intervention phase of the study while Cassidy did not make statistically significant gains until the follow-up phase. These results cannot be attributed to differences in severity – Henry exhibited the most profound impairment and William’s was the mildest, yet both showed good progress during treatment. Neither can our findings be attributed to differences in receptive language ability, cognitive ability, hearing acuity, or oral motor structure and function since all three children were comparable on these measures. Gender-related differences in performance have not been observed in previous studies (e.g. Montgomery & Bonderman, 1989).

Some authors have attributed individual differences in participant performance to parent motivation as measured by regularity and/or frequency of child attendance (Almost & Rosenbaum, 1998; Montgomery & Bonderman, 1989). The parents of our participants were highly motivated and dedicated to the rigorous intervention schedule. Each child participated in 18 60-minute sessions and any sessions that they missed were made up within the same week. Therefore, parent motivation is not likely to be a differentiating factor in the current study.

Differences in age might contribute to the across-participant variability observed in the current study. Hodson and Paden (1991) suggest that repeated incorrect production of problematic speech sounds may ‘fortify’ inaccurate internal representations over time. This implies that older children may have more difficulty overcoming their errors than younger children for whom, theoretically, erroneous patterns are less entrenched. Cassidy was the only five year old enrolled in the current study. The age gap between her and the remaining two participants may be partially responsible for her more gradual rate of improvement.

4.3. Pattern-level differences

Within-participant variability is a common phenomenon in SSD intervention studies (e.g., Tyler et al., 1987). In the current study, differences in generalization across target patterns could not be attributed to treatment duration or exposure. Each pattern was the direct target of therapy for exactly six sessions. Each session included 40 focused auditory exposures to the selected sound (20 at the beginning and 20 at the end) and incorporated six production practice words that were used for all activities. Furthermore, at least two contrasts were selected per pattern, which was previously found to be sufficient for generalization (Tyler et al.). This suggests that pattern-level differences are attributable to other factors.

Different target patterns and sounds were selected for each participant based on the requirements of the cycles protocol. These requirements were strictly observed insofar as our experimental design would allow. For William, this resulted in the selection of at least two patterns that were phonologically known even before treatment began, whereas, for Cassidy and Henry, this resulted in the selection of only phonologically unknown patterns. The results of our analysis suggest that known phonological patterns are more effectively and efficiently generalized than unknown patterns, which may explain why /s/ clusters and liquids showed the most rapid generalization for William, whereas Henry and Cassidy showed little progress during cycle I. Furthermore, Cassidy’s treatment program focused on later developing consonants (i.e., /s/ clusters, fricatives, and velars) while earlier developing consonants, such as nasals and stops, were targeted in Henry’s treatment program. This may explain why nasals and anterior-posterior contrasts showed more rapid generalization than /s/ clusters for Henry and why he showed greater progress than Cassidy during the intervention phase. Cassidy was likely to be at the greatest disadvantage both because targeted patterns were unknown and because targeted sounds were later developing.

Additional characteristics that have been associated with differences in pattern generalization include speech perception ability and stimulability (Rvachew et al., 1999), as well as order of treatment (Dinnsen & Elbert, 1984). None of these factors were directly addressed in the current study, but may account for additional variability in observed outcomes and should be pursued in future research investigating the cycles approach.

4.4. Comparison to clinical improvement

Those children who showed the most improvement on the generalization probe during the intervention phase were the same who made the greatest gains on PCC and percentage occurrence of phonological processes between pre- and post-intervention assessments. This is not surprising given that the patterns we targeted in treatment were meant to facilitate increased intelligibility and reduction of phonological process use. However, there was some discrepancy between improvement on the generalization probe and phonological process use. This may be due, in part, to the fact that one process can affect multiple phonological patterns. For example, cluster reduction affects /s/ clusters as well as liquid clusters; both would need to be treated for a significant decrease in cluster reduction to occur. If participants had received treatment for a greater variety of phonological patterns, we would likely have seen a higher degree of correspondence between performance on the generalization probe and performance on this clinical measure.

4.5. Limitations

The generalizability of our results may be limited by certain factors related to study design, probe administration, and treatment implementation. The findings must, therefore, be considered in light of these limitations.

First of all, single-subject research, by definition, involves small samples of participants. As a result, single-subject investigators are limited in their ability to draw general conclusions. While this is certainly a limitation of the methodology used in the current study, single subject designs allow analysis of individual learning and performance – aspects that are often lost in group study designs.

Second, the generalization probes were administered by the treating clinician, which prohibited blind administration. Lack of blinding could bias the administrator towards differential implementation and may affect the construct validity of a study. In the current study, the probe was a direct imitation task where the stimuli were presented in rapid succession and no corrective feedback was provided. The probe generally took less than three minutes to administer. Opportunities for biased implementation were limited. Furthermore, effect size estimates and phase comparisons were not calculated until after every participant had completed the study protocol, therefore, the clinician could not know whether participants were making significant progress. Interrater reliability for scoring was performed by a blind observer and agreement was high (range: 92%–97%) verifying that the results reported are reflective of participant performance on the probe.

Third, the generalization probe words were elicited in imitation rather than spontaneously. Spontaneous production can provide a more representative reflection of a child’s conversational ability. However, in the current study, statistically significant improvement on the probe generally corresponded with clinically significant improvement on measures of consonant accuracy and phonological process use. The assessment instrument used to obtain the clinical measures involved spontaneous production suggesting that performance on the direct imitation task provided a reasonable representation of participant ability in spontaneous production contexts.

Fourth, there were many within-session factors that were not controlled. For example, the types of facilitative cues varied from child to child based on individual needs and no criterion was set for number of productions per session. While types of cues and number of production opportunities may affect treatment outcomes, the authors of the cycles approach emphasize errorless learning over these aspects. They recommend that clinicians should do everything they can to promote correct productions of the training sounds in carefully selected words, and suggest that number of productions is not as important as accuracy of production. Accuracy was the focus of treatment in the current study, so aspects related to frequency were left free to vary.

Fifth, all of our measures focused on phoneme-level accuracy within the context of single words. It is possible that our participants were exhibiting changes at higher levels of the phonological hierarchy, which could have affected their intelligibility in spontaneous speech. However, we chose to focus on single word production in the current study because the poor intelligibility of our participants limited the interpretability of their spontaneous speech. Nonetheless, examining performance at other levels of the phonological hierarchy could have provided valuable information about their abilities that was not captured by our measures.

Finally, in terms of frequency and duration, the treatment schedule implemented in this study was more intense than the treatment that is typically provided in clinical practice. Our participants received three hours of individual therapy every week, whereas, school-age children with speech sound disorders generally participate in one or two 20 to 30 minute group sessions per week. The impact of intensity on participant progress was not addressed in the current study and it is possible that progress would have been less pronounced if there has been more time for skill loss between sessions. On the other hand, decreased intensity may allow for greater consolidation of learned skills, especially if parents reinforce learning with daily home practice exercises.

4.7. Conclusions, future directions, and clinical implications

The results of this study provide experimental evidence in support of the efficacy of the cycles approach when implemented as described by Hodson and colleagues (Hodson & Paden, 1991; Hodson, 2010; Prezas & Hodson, 2010). The combination of pattern-based target selection, cyclical treatment, focused auditory input, and production-practice activities resulted in statistically reliable generalization to non-treatment stimuli for two out of three children by the end of the intervention phase and for all three children by the follow-up phase. This suggests that the cycles approach is an efficient and effective method for treating severe SSDs in preschool age children.

However, this evidence is preliminary. We identified some possible limitations of using the unmodified cycles approach and suggest that other methods of target selection may be appropriate depending on the client’s phonological profile. It is also possible that variations in treatment intensity, goal attack strategy, or order of treatment may result in more rapid generalization. Future research is needed to explore these manipulations. In addition, this study does not provide insight into the efficacy of the cycles approach relative to other common treatment methods, such as the minimal pairs approach or traditional articulation therapy. However, the positive results of the current investigation are encouraging and promote the implementation of a randomized group comparison study in which the unmodified cycles approach is tested against an alternative SSD treatment method.

For clinicians interested in using the cycles approach as described by Hodson, the results of this study suggest that learning may occur in stages. If target patterns are known before treatment begins, the client may show good progress during the first cycle of therapy. Good progress may also be observed if target sounds are early developing. However, if target patterns are unknown or target sounds are later developing, one or more cycles may be needed to set a phonological foundation before meaningful improvement is detected. Though interpretation of our results is limited by constraints of design and implementation, the findings provide insight into potential sources of individual variability and offer experimental evidence supporting the efficacy of the unmodified cycles approach.

Table 7.

Percentage Consonants Correct and Phonological Process Percentage of Occurrence

| Pre-treatment (%) | Post-treatment (%) | Diff (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage Consonants Correcta | |||

| William | 54 | 69 | 15 |

| Severity | moderate-severe | mild-moderate | |

| Cassidy | 30 | 37 | 7 |

| Severity | severe | severe | |

| Henry | 18 | 34 | 16 |

| Severity | severe | severe | |

| Percentage of Occurrencea | |||

| William | |||

| Cluster Reduction | 68 | 58 | 10 |

| Fricative Alveolarization | 83 | 43 | 40 |

| Gliding | 80 | 71 | 9 |

| Cassidy | |||

| Cluster Reduction | 97 | 84 | 13 |

| Fronting | 100 | 95 | 5 |

| Stopping | 89 | 72 | 17 |

| Henry | |||

| Nasal Omission | 100 | 76 | 24 |

| Regressive Assimilation | 100 | 43 | 57 |

| Cluster Reduction | 94 | 90 | 4 |

Calculated based on production of 50 single words from the HAPP-3.

Highlights.

the cycles approach significantly improved speech sound accuracy

the number of cycles needed to achieve generalization varied

known targets were more efficiently and effectively learned than unknown targets

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support provided by a Student Research Grant in Early Childhood Language Development from the American Speech-Language-Hearing Foundation and by Grant TL1 RR025759 (A. Shekhar, PI) from the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Clinical and Translational Sciences Award. We thank the families who participated in this study for their time, dedication, and dependability. We extend special thanks to Dr. Anu Subramanian and Allison Gladfelter who performed reliability checks for treatment implementation and data collection and to Casey Hobbs who helped with material preparation.

Appendix A

| Participant | Process | Target Pattern | Target Sounds | Probe Words |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| William | Cluster Reduction | S-clusters | initial sp, st, sk | spare, spear, spur star, stir, store scar, scare, score |

| Fricative Alveolarization | Non-alveolar fricatives | initial f, final f, final v | far, fear, fur brief, trough, graph, brave, drive, groove |

|

| Gliding | Liquids | initial l, medial l, initial r | leer, lore, lure polar, dealer, color rare, rear, roar |

|

| Cassidy | Cluster Reduction | S-clusters | initial sp, st, sn | spare, spear, spur star, stir, store snare, sneer, snore |

| Fronting | Velars | final k, initial k, initial g | brake, truck, greek core, car, care gear, guard, gourd |

|

| Stopping | Final fricatives | final s, ʃ | drops, grapes, cracks price, dress, grass brush, trash, crash |

|

| Henry | Nasal Omission | Nasals | initial m, final m, final n | mar, mere, more broom, trim, cream brown, train, croon |

| Regressive Assimilation | Anterior-posterior contrastsa | initial p with final t or k initial b with final t or k initial k with final p or t |

port, part, perk bark, bert, bark carp, cart, court |

|

| Cluster Reduction | S-clusters | initial sp, st, sk | spare, spear, spur star, stir, store scar, scare, score |

Henry was required to produce both the initial and final consonant of the probe words correctly in order to receive credit for anterior-posterior contrasts.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Almost D, Rosenbaum P. Effectiveness of speech intervention for phonological disorders: A randomized-controlled trial. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 1998;40:319–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer DM, Wolf MM, Risley TR. Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1968;1:91–97. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker E, McLeod S. Evidence-based practice for children with speech sound disorders: Part 1 narrative review. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in the Schools. 2011a;42(2):102–139. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2010/09-0075). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bothe AK, Richardson JD. Statistical, practical, clinical, & Personal Significance: Definitions and applications in speech-language pathology. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2011;20:233–242. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2011/10-0034). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgemeister BB, Blum LH, Lorge I. Colombia Mental Maturity Scale. 3. New York: Harcourt Brace; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Conture EG, Louko LJ, Edwards ML. Simultaneously treating stuttering and disordered phonology in children: Experimental treatment, preliminary findings. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 1993;2:72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Culatta B, Setzer LA, Horn D. Meaning-based intervention for a child with speech and language disorders. Topics in Language Disorders. 2005;25(4):388–401. [Google Scholar]

- Dinnsen DA, Elbert M. On the relationship between phonology and learning. In: Elbert M, Dinnsen DA, Weismer G, editors. Phonological theory and the misarticulating child. Rockville, MD: ASHA; 1984. pp. 59–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn OJ. Multiple comparisons using rank sums. Technometrics. 1964;6:241–252. [Google Scholar]

- Gierut JA, Elbert M, Dinnsen DA. A functional analysis of phonological knowledge and generalization learning in misarticulating children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1987;30:462–479. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3004.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillon GT. Facilitating phoneme awareness development in 3- and 4-year-old children with speech impairment. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 2005;36:308–324. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2005/031). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaspey A, Stoel-Gammon C. Dynamic assessment in phonological disorders: The scaffolding scale of stimulability. Topics in Language Disorders. 2005;25(3):220–230. [Google Scholar]

- Glaspey A, Stoel-Gammon C. A dynamic approach to phonological assessment. Advances in Speech-Language Pathology. 2007;9(4):286–296. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Brannan M, Hodson B, Wynne M. Remediating unintelligible utterances of a child with a mild hearing loss. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 1992;1:28–38. [Google Scholar]

- Harbers HM, Paden EP, Halle JW. Phonological awareness and production: Changes during intervention. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 1999;30(1):50. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461.3001.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodson B. A facilitative approach for remediation of a child’s profoundly unintelligible phonological system. Topics in Language Disorders. 1983;3:24–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hodson B. Evaluating and enhancing children’s phonological systems: Research and theory to practice. Wichita, KS: Phonocomp Publishers; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hodson B. Hodson Assessment of Phonological Patterns. 3. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hodson B, Chin L, Redmond B, Simpson R. Phonological evaluation and remediation of deviations of a child with a repaired cleft palate: A case study. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1983;48:93–98. doi: 10.1044/jshd.4801.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodson B, Nonomura CW, Zappia M. Phonological disorders: Impact on academic performance? Seminars in Speech and Language. 1989;10(3):252–259. [Google Scholar]

- Hodson B, Paden E. Targeting intelligible speech: A phonological approach to remediation. 2. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed/College Hill; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Juneau P. Simultaneous Nonparametric Inference in a One-Way Layout Using the SAS® System. 2004. May, Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Kratochwill TR, Hitchcock J, Horner RH, Levin JR, Odom SL, Rindskopf DM, Shadish WR. Single-case designs technical documentation. 2010 Retrieved from What Works Clearinghouse website: http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/pdf/wwc_scd.pdf.

- Mann HB, Whitney DR. On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1947;18(1):50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery JK, Bonderman IR. Serving preschool children with severe phonological disorders. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 1989;20:76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Mota HB, Keske-Soares M, Bagetti T, Ceron MI, Filha MDGDC. Análise comparativa da eficiência de três diferentes modelos de terapia fonológica. Pró-Fono Revista de Atualização Científica. 2007;19(1):67–74. doi: 10.1590/s0104-56872007000100008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell TW, Elbert M. Generalization following the remediation of early- and later-developing consonant clusters. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1984;49:211–218. doi: 10.1044/jshd.4902.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prezas RF, Hodson BW. The cycles phonological remediation approach: Enhancing children’s phonological systems. In: Williams L, McLeod S, McCauley R, editors. Interventions for speech sound disorders in children. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing Company; 2010. pp. 137–158. [Google Scholar]

- Reimers T, Wacker D. Parents’ ratings of the acceptability of behavioral treatment recommendations made in an outpatient clinic: A preliminary analysis of the influence of treatment effectiveness. Behavioral Disorders. 1988;14:7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins J, Klee T. Clinical assessment of oropharyngeal motor development in young children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1987;52:271–7. doi: 10.1044/jshd.5203.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rvachew S, Brosseau-Lapre F. Developmental phonological disorders: Foundations of clinical practice. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rvachew S, Nowak M, Cloutier G. Effect of phonemic perception training on the speech production and phonological awareness skills of children with expressive phonological delay. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2004;13:250–263. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2004/026). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rvachew S, Rafaat S, Martin M. Stimulability, speech perception skills, and the treatment of phonological disorders. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 1999;8(1):33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Schopler E, Van Bourgondien ME, Wellman GJ, Love SR. Childhood Autism Rating Scale, Second Edition (CARS-2) Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Scruggs TE, Mastropieri MA, Casto G. The quantitative synthesis of single-subject research: Methodology and validation. Remedial and Special Education. 1987;8:24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Scruggs TE, Mastropieri MA, Cook, Escobar C. Early intervention for children with conduct disorders: A quantitative synthesis of single-subject research. Behavioral Disorders. 1986;11:260–271. [Google Scholar]

- Semel EM, Wiig EH, Secord WA. Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals – Preschool 2. San Antonio, TX: PsychCorp/Harcourt; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shriberg LD, Kwiatkowski J. Phonological disorders III: A procedure for assessing severity of involvement. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1982;47:256–270. doi: 10.1044/jshd.4703.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeonsson R, Bailey D. Evaluating programme impact: Levels of certainty. In: Mitchell D, Brown R, editors. Early intervention studies for young children with special needs. London: Chapman & Hall; 1991. pp. 280–296. [Google Scholar]

- Stoel-Gammon C, Stone-Goldman J, Glaspey A. Pattern-based approaches to phonological therapy. Seminars in Speech and Language. 2002;23(1):3–13. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-23507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler AA, Edwards ML, Saxman JH. Clinical application of two phonologically based treatment procedures. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1987;52:393–409. doi: 10.1044/jshd.5204.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler AA, Watterson KH. Effects of phonological versus language intervention in preschoolers with both phonological and language impairment. Child Language Teaching and Therapy. 1991;7:141–160. [Google Scholar]