Abstract

Objective To systematically review published and unpublished efficacy studies of agomelatine in people with depression.

Design Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources Literature search (Pubmed, Embase, Medline), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, European Medicines Agency (EMA) regulatory file for agomelatine, manufacturers of agomelatine (Servier).

Eligibility criteria Double blind randomised placebo and comparator controlled trials of agomelatine in depression with standard depression rating scales.

Data synthesis Studies were pooled by using a random effects model with DerSimonian and Laird weights for comparisons with placebo and comparator antidepressant. The primary efficacy measure (change in rating scale score) was summarised with standardised mean difference (SMD; a measure of effect size) and secondary outcome measures with relative risks. All results were presented with 95% confidence intervals. Statistical heterogeneity was explored by visual inspection of funnel plots and by the I2 statistic. Moderators of effect were explored by meta-regression.

Results We identified 20 trials with 7460 participants meeting inclusion criteria (11 in the published literature, four from the European Medicines Agency file, and five from the manufacturer). Almost all studies used the 17 item Hamilton depression rating scale (score 0-50). Agomelatine was significantly more effective than placebo with an effect size (SMD) of 0.24 (95% confidence interval 0.12 to 0.35) and relative risk of response 1.25 (1.11 to 1.4). Compared with other antidepressants, agomelatine showed equal efficacy (SMD 0.00, −0.09 to 0.10). Significant heterogeneity was uncovered in most analyses, though risk of bias was low. Published studies were more likely than unpublished studies to have results that suggested advantages for agomelatine.

Conclusions Agomelatine is an effective antidepressant with similar efficacy to standard antidepressants. Published trials generally had more favourable results than unpublished studies.

Introduction

Agomelatine is a novel antidepressant approved in February 2009 for use in the European Union.1 It is thought to act through a combination of antagonist activity at 5HT2C receptors and agonist activity at melatonergic MT1/MT2 receptors.2 As such, its pharmacology is unique among licensed antidepressant drugs, possessing no ability to interfere with the neuronal reuptake of serotonin, norepinephrine (noradrenaline), or dopamine. A meta-analysis of published trials suggested robust efficacy in major depression, with an estimated effect size of 0.26 compared with placebo.3

In medicine there is considerable concern over selective publication of trials with positive results—so called publication bias. With antidepressants, this was first commented on after the apparent suppression of negative data for antidepressants used in children.4 More recently, public access to details of trials registered with regulatory authorities has allowed a fuller assessment of the efficacy of newer antidepressants. For example, an analysis of antidepressant trials registered with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) found that 31% of registered trials were not published, most of them having negative findings.5 Of published studies, 95% had positive results, but of all studies only 51% had positive results. Analysis of both published and unpublished studies reduced the overall estimated effect size from 0.41 (published studies) to 0.31 (all studies). A similar, and again more complete, analysis of studies of the antidepressant reboxetine strongly suggested that it was in fact ineffective in major depression, showing no superiority over placebo when all studies were considered.6

We assessed the efficacy of agomelatine using both published trials and unpublished studies obtained from regulatory authorities and from the manufacturer.

Method

Eligibility criteria

Studies evaluating the efficacy of agomelatine in acute treatment (6-12 weeks) of depression in adults were eligible for inclusion. Included studies also had to be randomised, double blind, and controlled (placebo and/or other antidepressant). Patients needed to meet criteria for major depressive disorder as defined by each study. We considered only those studies evaluating agomelatine at the licensed recommended doses of 25 mg or 50 mg. Studies recruiting patients for evaluation of other outcomes were considered provided they met criteria for major depressive disorder as defined above and had collected data for outcomes in depression. Studies were excluded if the main outcome was prevention of relapse or if outcomes for the treatment of depression in the acute phase were not available.

Outcome measures

The main outcome was the change in mean scores on a depression rating scale at the end of treatment. We considered studies using established depression rating scales such as the Hamilton rating scale for depression (HAM-D)7 or the Montgomery-Åsberg depression rating scale (MADRS).8 Secondary outcome measures were response and remission of depression as defined by the primary studies. Most defined response as 50% reduction in baseline rating scale measurements and remission as HAM-D ≤7 or MADRS ≤12.

The emphasis of our review was efficacy and so we based selection criteria on factors related to efficacy outcomes. We did not intend to systematically evaluate adverse outcomes, but to set in context efficacy findings we also recorded outcomes related to tolerability and harms. Specifically, when available, we recorded early discontinuations from studies (both in total and those specifically related to adverse effects).

Search strategy and study selection

We searched for studies meeting our inclusion criteria using the following search terms: agomelatine, controlled trial, double blind, and depression. There were no limits applied for language and date of publication. We undertook a full electronic search of the following databases from inception to 2013: Embase, Medline, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and PubMed, with the last search performed in March 2013. We also searched references lists of retrieved articles, conference abstracts, and trials registries for additional studies. We applied to the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for details of all studies submitted in support of regulatory approval of agomelatine. We also contacted the European manufacturer of agomelatine, Servier, and requested details of published and unpublished studies.

Studies were first identified for inclusion by examining the title and abstract of each record. We then sought the full text version of suitable articles before applying the inclusion criteria. Two authors (OO and AS) applied the inclusion criteria independently to identify studies for the meta-analysis. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Data extraction

Using a standard spreadsheet, two authors (OO and SV) extracted data independently and any discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The following data were extracted:

Participants’ characteristics: age, sex, diagnosis, and measures of severity of depression (symptom rating scales)

Treatment: type of comparator (active or placebo), dose, and duration of treatment

Outcome measures: mean baseline and final depression rating scale scores and corresponding standard deviations (SDs), analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) effect estimates (when available) and corresponding standard errors, and number of responders and remitters in each treatment group

Information necessary to assess the risk of bias in included studies.

All outcome data were extracted on an intention to treat principle as defined in the primary studies. When information was missing on essential variables we contacted authors for further information.

Risk of bias

Two authors independently assessed the risk of bias in individual studies, and any disagreements were resolved by discussion. According to recommendations from the Cochrane Collaboration9 we assessed the risk of bias associated with sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and investigators, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other bias. Each domain was rated as low, high, or unclear. Overall, risk of bias for each study was judged on the first three items: sequence generation, allocation concealment, and blinding. Studies judged to have a high risk of bias on these domains were excluded from the main analysis.

Data synthesis

The primary summary measure of treatment effect is the standardised mean difference (SMD) using the method of Hedges (Hedges g).10 The SMD, which is the difference in mean final values between agomelatine and comparator standardised by the standard deviation, was chosen in preference to raw scores to enable results of different rating scales to be combined in the same analysis. The preferred measure of effect is an estimate produced by analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), which adjusts for baseline imbalances. This outcome is not often reported in trials of antidepressants, however, so we opted to use final values in favour of change scores as the former is equivalent to using ANCOVA estimates when there is no baseline imbalance.11 Moreover use of final values as the outcome measure saves the effort of having to impute standard deviations, which are often missing from results of outcomes with change scores.

For the secondary outcome measures, we computed risk ratios for responders and remitters and pooled across studies.

All analyses were performed with a random effects meta-analysis with DerSimonian and Laird weights. Separate analyses were conducted each for comparison of placebo and/or antidepressant with agomelatine. Studies that evaluated more than one dose of agomelatine were combined to form one composite measure as described by Borenstein and co-workers.10 All effect sizes were presented with corresponding 95% confidence intervals and P values. Non-significance was concluded if confidence intervals included 0 for continuous outcomes or 1 if outcomes were ratio measurements.

To test the robustness of methods used for our primary analyses we planned the following sensitivity analyses:

Summarising effects with a fixed effect model

Summarising with available ANCOVA estimates

Summarising with raw mean differences (HAM-D)

Summarising with final raw final values (HAM-D)

Restricting analyses to studies considered to have a low risk of bias.

Heterogeneity in effect sizes was explored by visual inspection of forest plots and quantified with the I2 statistic. For comparisons that showed considerable amount of heterogeneity (defined as I2 >50%) we further explored possible reasons for variation. As determined a priori, possible moderators of effect—such as treatment duration, dose of antidepressant, age, number of previous episodes, and aspects of study quality such as low risk of bias and allocation concealment—were considered for entry into a meta-regression.

We explored bias in study availability (“publication bias”) by visual inspection of funnel plots and by Egger’s test to test for funnel asymmetry. Analyses were performed with Revman 512 and Stata 11.13

Results

Description of studies

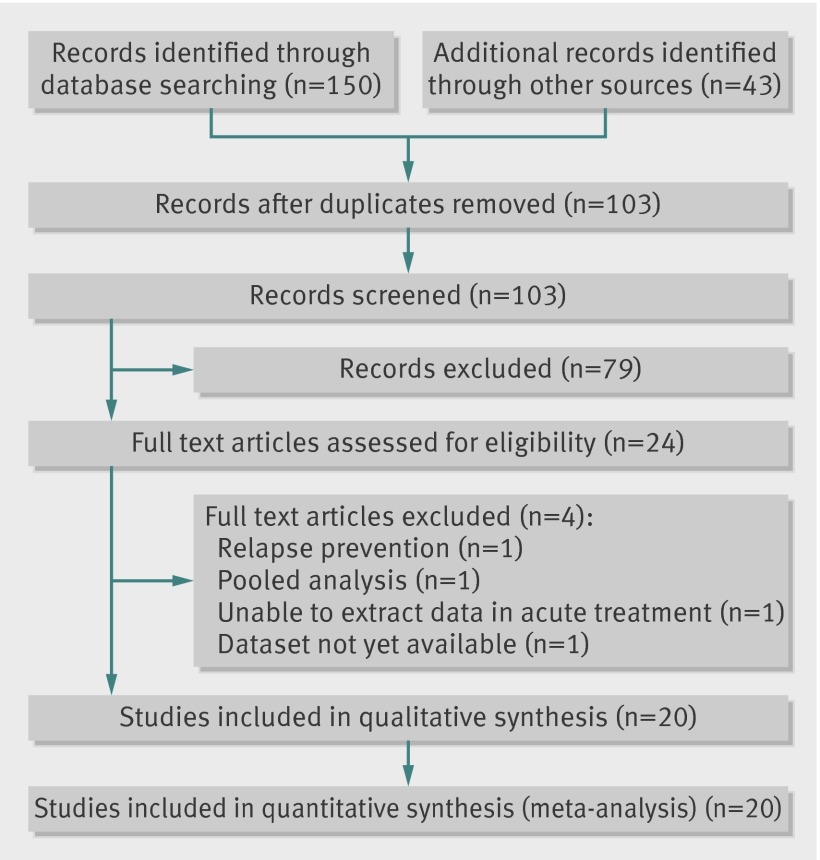

We completed our literature search in March 2013, and we also received a CD from the EMA giving full details of trials used in the regulatory process. Also in March 2013 the manufacturer, Servier, supplied internal reports of all completed trials sponsored by them. We identified 193 records from these sources (fig 1). After applying eligibility criteria, we considered 24 studies for inclusion but, on further examination, we excluded four of them.14 15 16 17

Fig 1 Flow chart of identification and inclusion of studies on antidepressant efficacy of agomelatine

Overall, we included in the meta-analysis 20 trials (n=7460),18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 making 12 pairwise comparisons with placebo and 13 comparisons with other antidepressants. The sources of these included studies were as follows: 11 were indentified in our literature search18 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36; four more were found in the EMA submission document19 20 21 22; and full details of five further studies were provided by the manufacturer, Servier23 24 25 26 37 (one of which26 was published in full38 during manuscript preparation). Servier also confirmed that there were no other completed studies known to them other than those we had ourselves identified and those about which they had notified us.

Most studies were multicentred and multinational, being conducted in 32 different countries (appendix). All studies were published in English; three studies were conducted in the United States, one in Asia, and the remainder in Europe and other parts of the world including South Africa and South America. Patients were diagnosed with major depressive disorder with criteria defined by the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, DSM-IV. With the exception of two studies,22 36 all studies used the HAM-D as their primary depression rating tool. One study included a small number (<2%) of patients with bipolar II depression.31

Several studies recruited depressed patients with the primary intention of evaluating conditions separate from depression: quality of sleep function (three studies)25 33 39 and sexual functioning (one study).36 Participants were considered to be moderately/severely ill at baseline with mean HAM-D score of 27.0 (SD 1.0) (using a cut off HAMD score of 23, as suggested by National Institute for Clinical Excellence guidelines in depression).40 Three studies specifically recruited adults aged over 60,22 23 26 and one study included only patients with severe depression (HAM-D ≥25).27 All studies had a preponderance of female participants, with proportions ranging from 58.4% to 77%. Antidepressants compared with agomelatine included escitalopram (n=2), fluoxetine (n=4), sertraline (n=1), paroxetine (n=4), and venlafaxine (n=2). Studies lasted from six weeks to 12 weeks. One trial, which was designed as a dose finding study, included low doses of agomelatine (1 mg and 5 mg),31 which are not licensed doses in the United Kingdom. Another examined 10 mg a day alongside 25 mg and 50 mg.37 Likewise 10 mg a day is not a licensed dose in the UK. These unlicensed doses were not included in the final analysis.

All studies included patients from what was described as the full analysis set, which is based on intention to treat principles. The full analysis set consisted of patients receiving at least one dose of drug and having at least one measurement after baseline. All studies reported using the last observation carried forward method for missing observations.

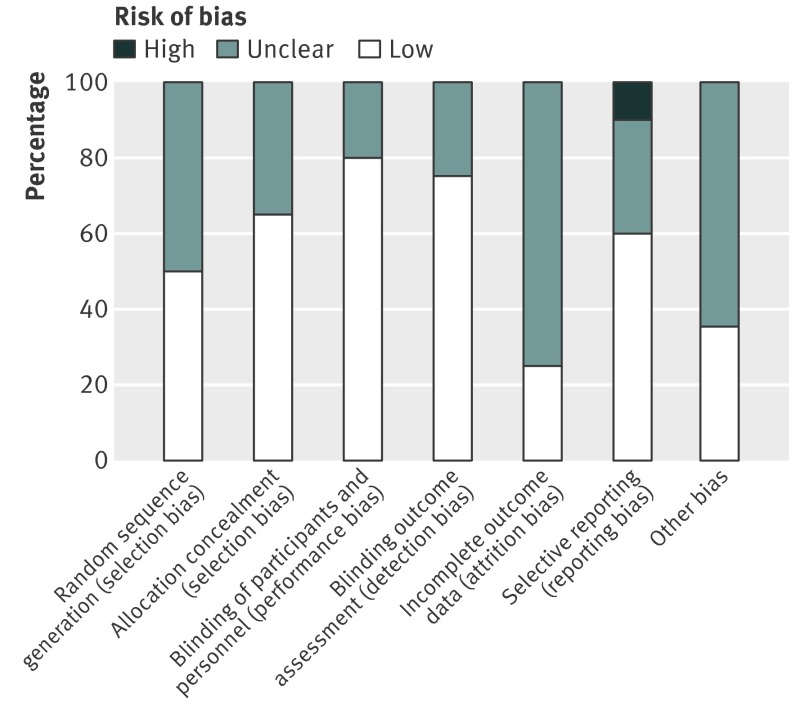

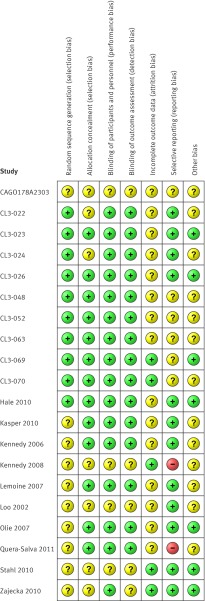

Risk of bias

Figure 2 shows the risk of bias across all studies. Most studies lacked sufficient information for full assessment. The unpublished reports supplied to us in general had more detail than published studies to allow a full assessment. Ten studies were considered as having a low risk of bias with respect to methods for sequence generation (fig 3). Blinding of participants and staff, when described, was of low risk or unclear risk, with none regarded as having high risk. Allocation concealment was considered adequate in most trials (13/20, 65%). We noted high risk of bias for two studies with regards to selective outcome reporting. Across all studies, the risk of bias was considered low or unclear based on evaluation of the first four domains, with eight studies meeting the criteria for low risk.

Fig 2 Risk of bias across studies on antidepressant efficacy of agomelatine

Fig 3 Risk of bias within studies on antidepressant efficacy of agomelatine

Quantitative analyses

As there were several unpublished studies, we decided (post hoc) to stratify each analysis by publication status.

Agomelatine v placebo

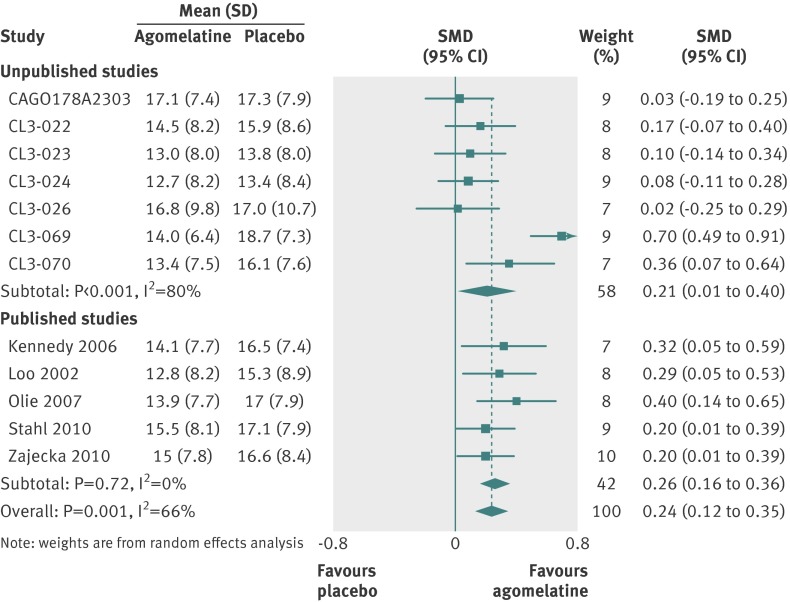

Twelve studies reported outcomes for 3951 randomised patients, which provided an intention to treat sample of 3855 patients for the primary analysis. Heterogeneity in effect sizes was substantial with I2=66% (fig 4). There was a significant difference favouring agomelatine (SMD 0.24, 95% confidence interval 0.12 to 0.35).

Fig 4 Standardised mean differences (SMD) for agomelatine v placebo in studies on antidepressant efficacy of agomelatine. Weights are from random effects analysis

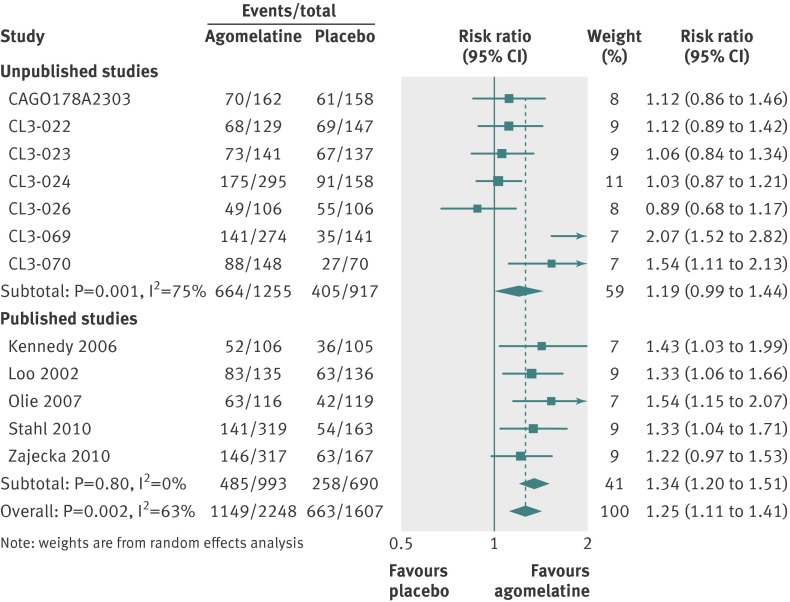

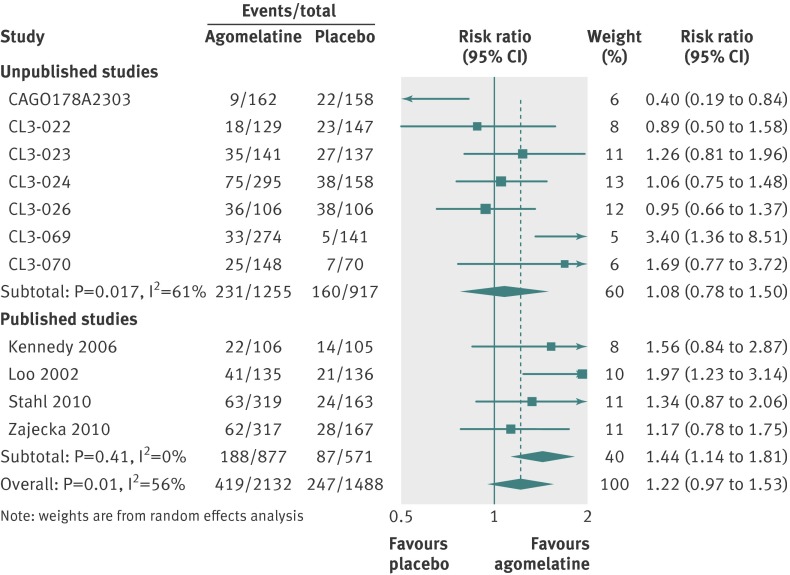

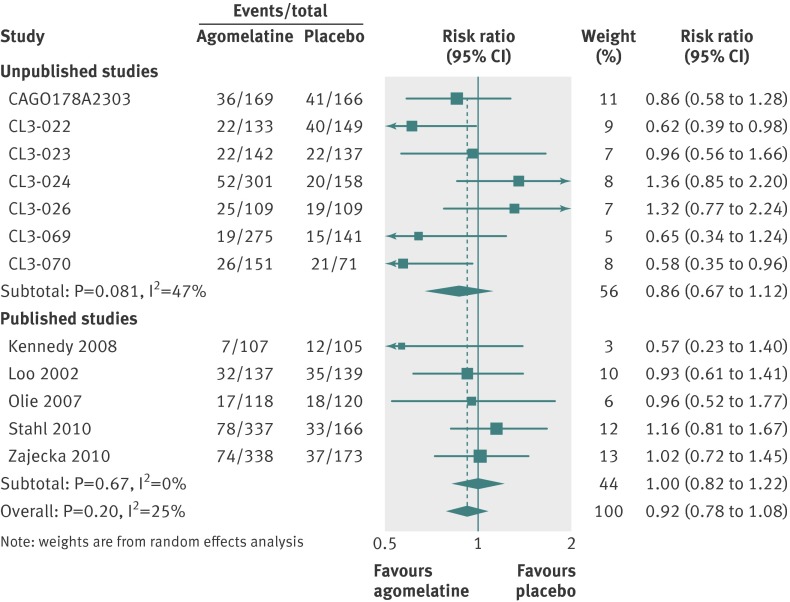

For secondary analyses, patients were more likely to respond to agomelatine than placebo (relative risk 1.25, 95% confidence interval 1.11 to 1.41; fig 5). Heterogeneity was high with I2=63%. In 11 studies reporting remission, there was no significant difference in remission rates between the agomelatine and placebo group (1.22, 0.97 to 1.53; fig 6). Again, heterogeneity was high with I2=56%.

Fig 5 Risk ratios for response with agomelatine v placebo in studies on antidepressant efficacy of agomelatine. Weights are from random effects analysis

Fig 6 Risk ratios for remission with agomelatine v placebo in studies on antidepressant efficacy of agomelatine. Weights are from random effects analysis

Agomelatine v antidepressants

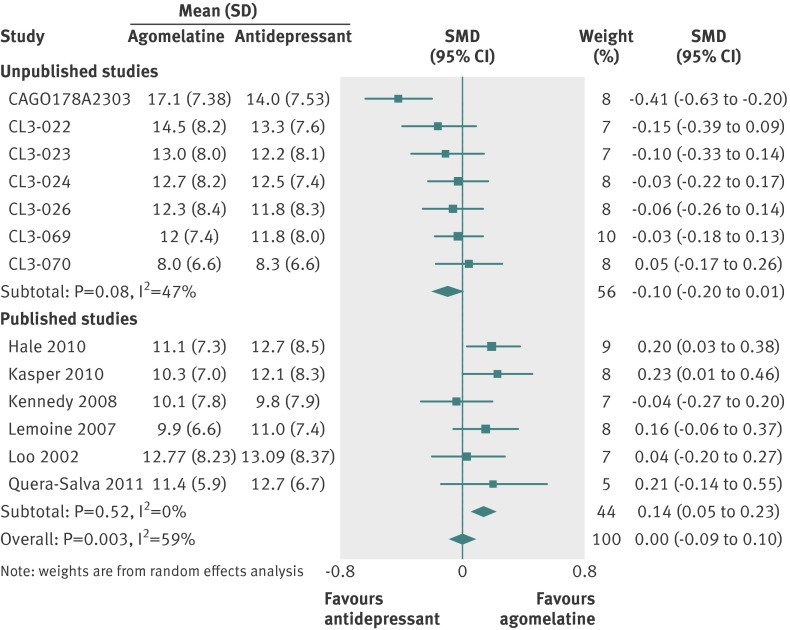

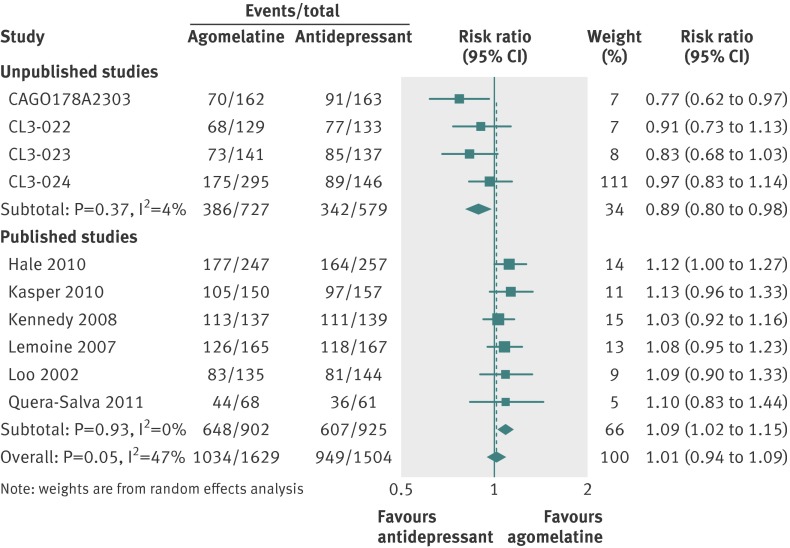

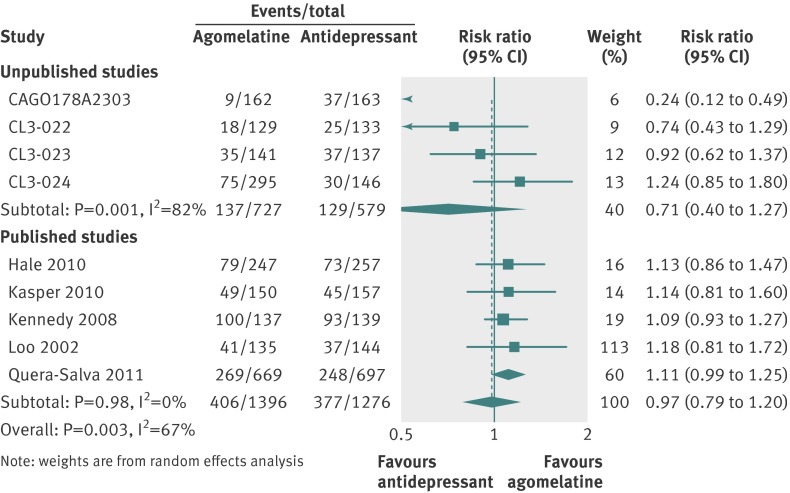

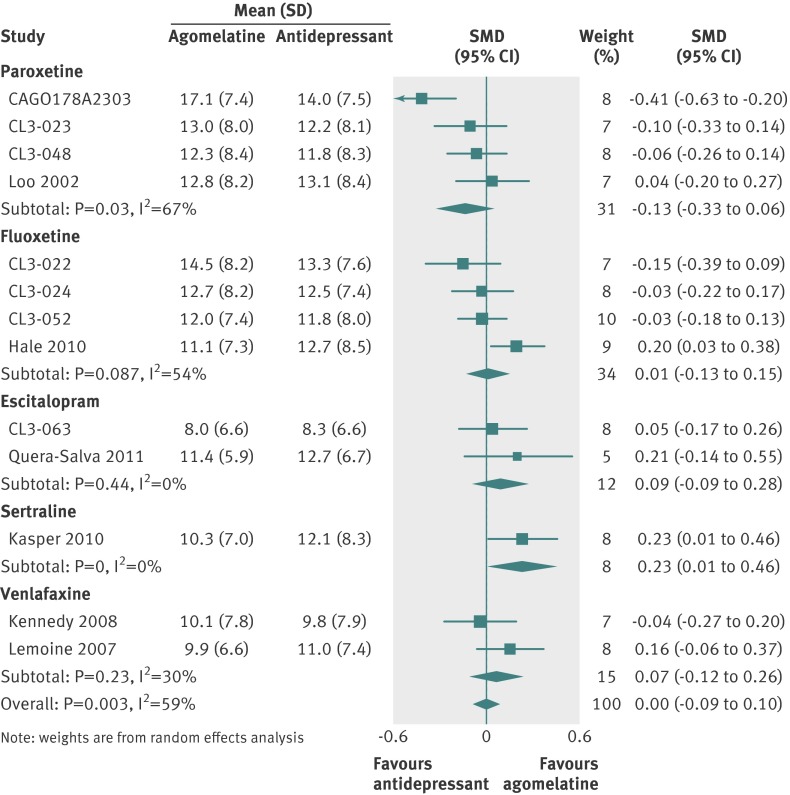

Thirteen studies (n=4559 randomised patients) were included in the primary analysis, providing an intention to treat sample of 4467 patients. Heterogeneity between effect sizes was substantial at I2=59%. There was no significant difference between groups (SMD 0.00, 95% confidence interval −0.09 to 0.10; fig 7). Responder analysis (10 studies) showed no significant difference between groups (relative risk 1.01, 0.94 to 1.09) with moderate heterogeneity (I2=47%) (fig 8). In eight studies reporting remission there was no difference in remission rates between the two groups (0.97, 0.79 to 1.20; I2=67%; fig 9).

Fig 7 Standardised mean differences (SMD) for agomelatine v antidepressant in studies on antidepressant efficacy of agomelatine. Weights are from random effects analysis

Fig 8 Risk ratios for response with agomelatine v antidepressant in studies on antidepressant efficacy of agomelatine. Weights are from random effects analysis

Fig 9 Risk ratios for remission with agomelatine v antidepressant in studies on antidepressant efficacy of agomelatine. Weights are from random effects analysis

We directly assessed variability in outcome related to comparator antidepressant by producing forest plots of the primary outcome examining each comparator in turn (fig 10). Few clear differences in outcome were apparent: agomelatine was significantly more effective than sertraline (SMD 0.23, 95% confidence interval 0.01 to 0.46), and there was a trend for agomelatine to be less effective than paroxetine (–0.13, −0.33 to 0.06).

Fig 10 Standardised mean differences for agomelatine v comparator by antidepressant in studies on antidepressant efficacy of agomelatine. Weights are from random effects analysis

Tolerability/harms

Data on overall discontinuation were available for 12 comparisons with placebo (2317 participants for agomelatine; 1634 for placebo) and 12 comparisons with comparator antidepressants (2215 participants for agomelatine; 2067 for comparator). Data on discontinuations because of adverse effects were available for the same number of studies and subjects for placebo comparisons but for 13 studies using active comparators (2352 participants for agomelatine; 2207 for comparator).

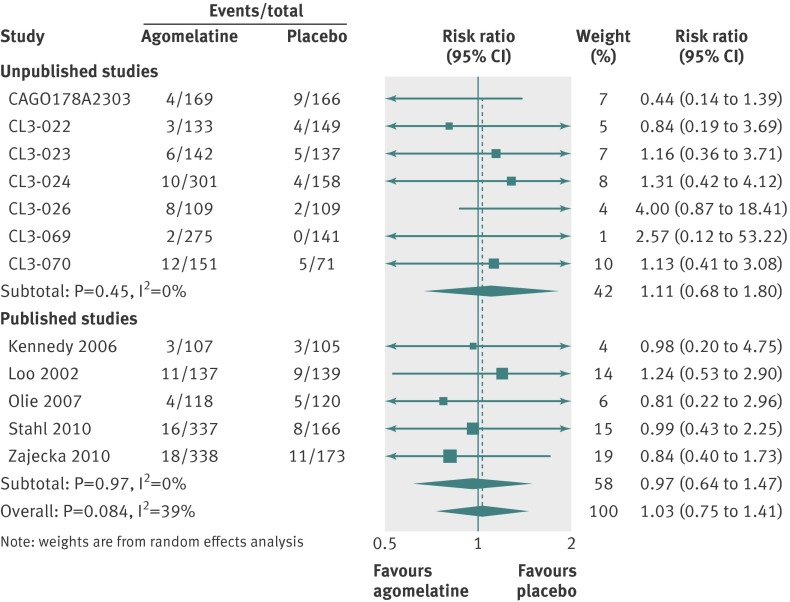

All cause discontinuations

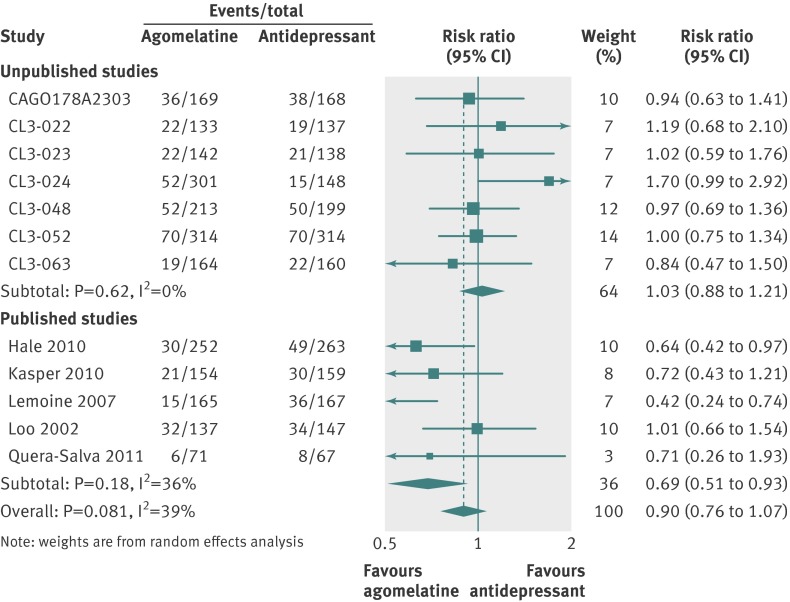

In placebo comparisons, all cause discontinuations were 410/2317 (18%) for agomelatine and 313/1634 (19%) for placebo (fig 11). In active comparator trials 377/2215 (17%) discontinued agomelatine and 392/2067 (19%) comparator antidepressants (fig 12). Patients were no more likely to discontinue agomelatine than placebo (relative risk 0.92, 95% confidence interval 0.78 to 1.08; fig 11) or comparator antidepressant (0.90, 0.76 to 1.07; fig 12).

Fig 11 Risk ratios all cause discontinuation v placebo in studies on antidepressant efficacy of agomelatine. Weights are from random effects analysis

Fig 12 Risk ratios all cause discontinuation v antidepressant in studies on antidepressant efficacy of agomelatine. Weights are from random effects analysis

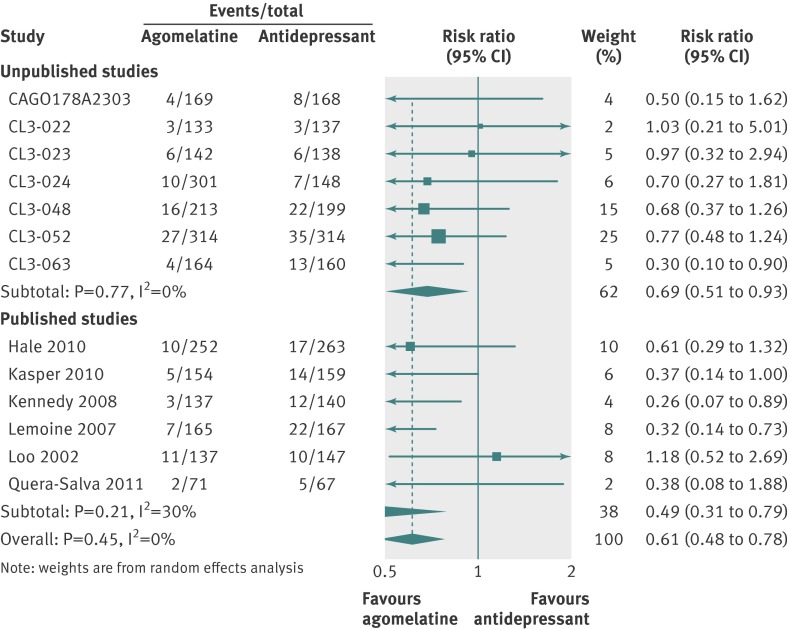

Discontinuations because of adverse effects

In placebo comparisons, discontinuations because of adverse effects were 97/2317 (4%) for agomelatine and 65/1634 (4%) for placebo (fig 13). In active comparator trials 108/2352 (5%) discontinued agomelatine and 174/2207 (8%) discontinued comparator antidepressants (fig 14).

Fig 13 Risk ratios for discontinuation because of adverse effects for agomelatine v placebo. Weights are from random effects analysis

Fig 14 Risk ratios for discontinuations because of adverse effects for agomelatine v another antidepressant. Weights are from random effects analysis

Participants randomised to agomelatine were no more likely to discontinue because of adverse effects than those randomised to placebo (relative risk 1.03, 95% confidence interval 0.75 to 1.41) (fig 13). Those randomised to agomelatine were less likely than those receiving comparator antidepressants to discontinue treatment because of adverse effects (0.61, 0.48 to 0.78; fig 14).

Sensitivity analysis

We did not undertake a sensitivity analysis of studies with low risk of bias for placebo comparisons as this would have resulted in a meta-analysis of only four studies, which would be insufficient to draw meaningful conclusions. For similar reasons we did not pool ANCOVA estimates or studies with low risk of bias for agomelatine versus antidepressants. The results of other sensitivity analyses did not significantly alter the direction or magnitude of the results in any of the comparisons (table 1).

Table 1.

Sensitivity analyses of studies on antidepressant efficacy of agomelatine

| Meta-analysis | No of studies | Effect size (95% CI) | I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agomelatine v placebo | |||

| Fixed effect model using final scores | 12 | 0.23 (0.17 to 0.30) | 66 |

| Random effects model using changes scores | 12 | 0.23 (0.12 to 0.34) | 66 |

| Random effects model using ANCOVA estimates (HAM-D scores only) | 10 | 1.9 (0.94 to 2.87)* | 68 |

| Random effects model using raw HAM-D final scores | 11 | 1.97 (1.12 to 2.82)† | 60 |

| Agomelatine v other antidepressant | |||

| Fixed effect model using final scores | 13 | 1.00 (−0.06 to 0.06) | 59 |

| Random effects model using changes scores | 13 | −0.01 (−0.10 to 0.10) | 56 |

| Random effects model using raw HAM-D final scores | 12 | 0.06 (−0.40 to 0.53)† | 63 |

*Raw mean differences on HAM-D scale adjusted for baseline scores.

†Raw mean differences on HAM-D scale.

Meta-regression

Table 2 shows the impact of effect moderators on the outcome. We were not able to fully explore the moderators of effect as planned because studies were either too few (age) or lacked sufficient variation in the covariate of interest (antidepressant dose and number of previous episodes) to produce meaningful results. Instead, we explored the effect of low risk of bias, allocation concealment, treatment duration, and duration of current episode in univariate analyses. There was no evidence of effect modification in the agomelatine versus placebo analyses for any of the variables tested. We found a non-significant association between allocation concealment and effect size, with adequate concealment associated with larger effect sizes. Allocation concealment explained 38% of the heterogeneity seen between studies of agomelatine compared with another antidepressant.

Table 2.

Meta-regression of effect modifiers

| Variable tested | Coefficient (95% CI)l | P value | Proportion (%) of variation explained by covariate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agomelatine v placebo (12 studies) | |||

| Duration of treatment >6 weeks | 0.04947 (−0.2158 to 0.3148) | 0.687 | −11.20 |

| Low risk of bias | 0.1043 (−0.1680 to 0.3766) | 0.413 | 0.35 |

| Allocation concealment | 0.1652 (−0.0717 to 0.4021) | 0.151 | 20.38 |

| Agomelatine v antidepressant (13 studies) | |||

| Duration of treatment >6 weeks | −0.0333 (−0.2557 to 0.1891) | 0.748 | −15.98 |

| Duration of current episode* | 0.0006 (−0.0021 to 0.0033) | 0.655 | −33.93 |

| Low risk of bias | 0.0191 (−0.1886 to 0.2268) | 0.843 | −17.46 |

| Allocation concealment | 0.1645 (−0.0165 to 0.3456) | 0.071 | 38.47 |

*12 studies.

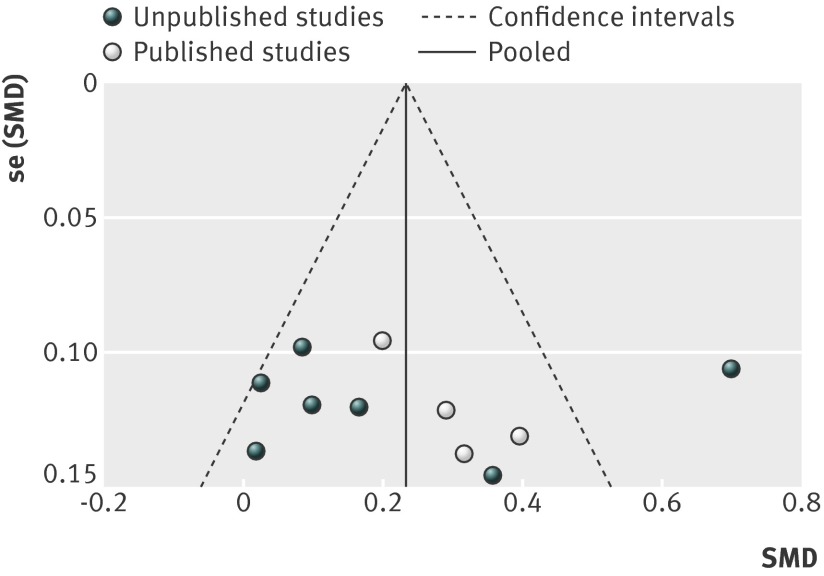

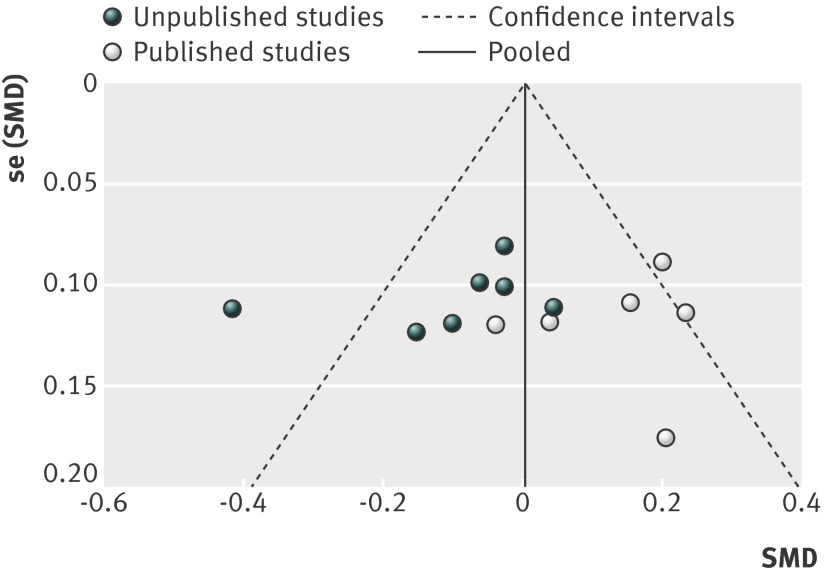

Publication/availability bias

Figures 15 and 16 show funnel plots of standardised mean differences by publication status. As included studies were of similar size (and thus precision), we could not tease out small study effects (smaller studies showing larger effects) from the funnel plots. Visual inspection of funnel plots and result of Egger’s test showed no evidence of funnel plot asymmetry for comparisons with placebo (P=0.793) (fig 15) and antidepressants (P=0.949) (fig 16). The plots did, however, show evidence of publication bias: unpublished studies were more likely to show positive results.

Fig 15 Funnel plot of standardised mean differences (SMD) for agomelatine v placebo in studies on antidepressant efficacy of agomelatine

Fig 16 Funnel plot standardised mean differences (SMD) for agomelatine v other antidepressant in studies on antidepressant efficacy of agomelatine

Discussion

This meta-analysis of completed trials of agomelatine in depression suggests an effect size for agomelatine compared with placebo of 0.24 (95% confidence interval 0.12 to 0.35), a relative risk of response of 1.25 (1.11 to 1.41), and relative risk of remission of 1.22 (0.97 to 1.53). Overall, agomelatine showed equal efficacy to other antidepressants on all measures, with little likelihood of important differences in efficacy in either direction. We can conclude that agomelatine is an antidepressant with similar efficacy to standard drug treatments; an important finding given its unique mode of action. Its failure to show statistical superiority to placebo for remission could reflect the fact that not all studies reported this outcome and so power to discern differences was accordingly reduced. Our unplanned analysis of acceptability showed that agomelatine was broadly better tolerated than comparator antidepressants.

Comparison with other antidepressants

An estimated effect size of 0.24 is small in absolute terms (see table 3) and is somewhat lower than that calculated from comprehensive reviews of trials of other antidepressants (effect size estimated at 0.315). If we accept that agomelatine is as effective as other antidepressants, as our analysis strongly suggests, then these disparate estimates require explanation. One probable contributor is the strengthening of placebo response in depression trials over time: the effect of placebo has increased substantially over the past decades,41 meaning that more recently examined drugs are likely to show a relatively small effect size compared with placebo. It is also possible that the effect size estimates derived for other antidepressants might be based on incomplete datasets and might not include unregistered or otherwise “hidden” studies with negative results, leading to an overestimate of their effect size. It is also worthy of note that the confidence intervals around our estimated effect size (0.12 to 0.35) include the effect size estimated for other antidepressants.

Table 3.

Real life examples of effect size*

| Effect size | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| 0.2 | Small | Difference in height between girls aged 15 and 16 |

| 0.5 | Medium “visible to naked eye” | Difference in height between girls aged 14 and 18 |

| 0.8 | Large “grossly perceptible” | Difference in height between girls aged 13 and 18 |

*Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum, 1988.

Publication bias

Visual inspection of our forest plots and funnel plots shows that unpublished studies tend to have less favourable results for agomelatine. With placebo as the comparator, the effect size was 0.21 (95% confidence interval 0.01 to 0.40) for unpublished studies and 0.26 (0.16 to 0.36) for published studies. Results of unpublished studies suggested no advantage for agomelatine over placebo in respect to response and remission. In comparisons with other antidepressants, published studies favoured agomelatine (standardised mean difference 0.14, 95% confidence interval 0.05 to 0.23) and unpublished studies tended to favour the comparator (−0.10, −0.20 to 0.01). In unpublished comparator studies, treatment response was statistically more likely with the comparator antidepressant—the opposite finding of the combined results of published studies. Overall, there is a strong impression of publication of trials whose results favoured agomelatine and the non-publication of less favourable trials (although Servier’s willingness to provide us with all data relating to trials of agomelatine should be noted).

Agomelatine is clearly an effective antidepressant, but its efficacy is undoubtedly overestimated when only published studies are considered—an observation confirmed by the results of other smaller meta-analyses, which have largely included only selected published data.3 42 43 The most recent meta-analysis including both published and unpublished studies estimated agomelatine’s effect size compared with placebo to be 0.18.43 This analysis did not include recently completed unpublished studies or studies with an active comparator. Table 4 summarises the results of this study and previous meta-analyses.

Table 4.

Other meta-analyses of agomelatine v placebo or other antidepressants

| Reference | Placebo studies | Antidepressant comparator studies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies/participants* | Outcome | Studies/participants* | Outcome | ||

| Singh, 2011 | 5/1963 | Agomelatine effect size (SMD) v placebo†=0.26 | 5/1698 | Agomelatine effect size (SMD) v comparator†=0.11 | |

| Kasper, 2013 | Nil | NA | 6/2034 | Mean difference in HAM-d score change=0.86 points† | |

| Koesters, 2013 | 10/2896 | Agomelatine effect size (SMD) v placebo†=0.18 | Nil | NA | |

| Current study | 12/3951 | Agomelatine effect size (SMD) v placebo†=0.24 | 13/4559 | Agomelatine effect size (SMD) v comparator=0.00 | |

SMD=standardised mean difference; NA=not applicable.

*Number randomised.

†Agomelatine significantly better on measure described.

Comparison with other specialties in medicine

The effect size of agomelatine estimated here, and that of other antidepressants, might suggest some doubt over their clinical utility and lend support to those who call for a more restricted use of antidepressants. Three observations should, however, be taken into account. Firstly, the effect size for antidepressants compared with placebo might be small, but the effect size of placebo itself in major depression has been estimated to be greater than 0.9.44 Indeed, placebo shows a clear “dose related” effect in depression: the more patients are visited and examined, the better their response.45 Secondly, where placebo effects are less apparent, in, for example, the prevention of depressive relapse, antidepressants show much higher effect sizes, usually greater than 0.5.46 Thirdly, even the small effect sizes calculated for antidepressants in acute treatment are not dissimilar to those observed in medical conditions such as hypertension (effect size for ACE inhibitors in prevention of cardiovascular events is 0.16) and acute stroke (effect size of thrombolysis on survival is 0.11).46 As with the use of other antidepressants, agomelatine might be expected to result in the improvement of perhaps three quarters of patients, although most these will be placebo responders.

Limitations

As with many meta-analyses our study has several limitations. We considered only short term efficacy studies of agomelatine, some of which did not have changes in depression rating scores as their primary outcome. The risk of bias assessment was hindered by poor reporting, thereby making it difficult to judge the quality of studies for some particular domains (such as sequence generation). Another potential limitation is that we aggregated data for 25 mg and 50 mg doses of agomelatine, which could result in some heterogeneity in effect size estimation. Agomelatine, however, has not shown a clear dose response relation between 25 mg and 50 mg a day, with outcomes for the two doses invariably being near identical and no clear pattern for one dose more often being more effective than another. Lastly, a particular concern was the high level of heterogeneity observed for both placebo controlled and comparator controlled studies and our inability to identify variables likely to be significant contributors to this heterogeneity. Interestingly, the one study that contributed most to the heterogeneity of placebo controlled outcomes was a study with particularly positive results for agomelatine, largely because of a much smaller placebo response than in other studies and not because of an unusually high absolute response to agomelatine.37 Perhaps most importantly we can be reasonably confident that we have captured all available data, taking into account the information supplied to us by the European Medicines Agency and by the manufacturer and the appearance of the funnel plots.

Strengths

Clearly the major strength of this analysis is that we have analysed what we believe to be all available suitable data from completed studies of agomelatine (as shown in our funnel plots) by a robust method that enabled minimisation of risk of bias. Data capture is perhaps the most important aspect of comprehensive meta-analysis, and the incalculable impact of reporting or publication bias is well recognised.47 48

Our analysis, the largest conducted to date, shows a modest effect for agomelatine compared with placebo (an effect both overestimated 3 and underestimated 43 in previous analyses) and its equivalence to comparator drugs (superior efficacy for agomelatine being suggested in previous meta-analyses3 42).

This study is perhaps a unique example of where working with regulatory authorities and drug manufacturers allows a full and realistic appraisal of the efficacy of a marketed drug.

Agomelatine in clinical guidelines

The most recent NICE guideline on depression published in 2009 did not include agomelatine because the drug was “not licensed at the time of data analysis.”40 Agomelatine is briefly mentioned in NICE guidelines on depression in chronic physical illness as one of a number of “third generation antidepressants.”49 Both guidelines recommend switching to “a better tolerated, newer-generation antidepressant” when there is inadequate response to a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). This somewhat vague description could be said to include agomelatine, although mirtazapine, duloxetine, and perhaps trazodone are also implied. There is strong evidence in this analysis that agomelatine is indeed “better tolerated.”

The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry suggest agomelatine as a possible choice of treatment after failure of two previous antidepressants.50 Support for this “third line” positioning is rather weak and based on a single naturalistic study,51 and theoretical considerations related to mode of action—that is, a different pharmacological action from SSRIs—might produce a response. Agomelatine is also recommended in these guidelines as an alternative to other antidepressants when poor tolerability or contraindications preclude the use of SSRIs, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), or mirtazapine.

Agomelatine—place in treatment

Agomelatine is a branded drug still protected by patent and therefore considerably more expensive than any of the large number of generic alternatives. Its use is further inhibited by the formal requirement for liver function testing at baseline and three, six, 12, and 24 weeks.52 This monitoring is mandated because of a low but important incidence (1.3%) of raised liver enzyme activity52 and the risk of non-fatal “toxic hepatitis”—six cases were reported from analysis of a German database,53 although only three cases of apparent liver “toxicity” (two cholelithiasis, one jaundice) have been reported in the UK since its introduction.54 In neither case do available data allow the calculation of the likely incidence of serious hepatic reaction to agomelatine. (Assessment of toxicity was not a specific objective of our analysis, and indeed we found no useful data relating to risk of hepatic reactions.)

Thus, despite agomelatine’s apparent equal efficacy to standard antidepressants, its costs and monitoring requirements make it unsuitable as a first line treatment. Agomelatine is a drug worthy of consideration because of its better tolerability and use in patients with adverse effects with standard antidepressants. SSRIs are sometimes poorly tolerated because they cause nausea, insomnia, and sexual dysfunction.55 Agomelatine has a low incidence of nausea,52 improves sleep,56 and seems not to affect sexual function.36 57 In addition, SSRIs are sometimes contraindicated because of their effect on blood clotting and the consequent risk of bleeding.58 59 Mirtazapine is often suggested as an alternative,49 but its use is complicated by weight gain60 and somnolence.61 Agomelatine does not seem to affect the blood clotting mechanism and has a low incidence of weight gain.52 Lastly, the use of perhaps all standard antidepressants is associated with discontinuation symptoms,62 which do not seem to occur with agomelatine.16 On balance, therefore, agomelatine is one of several sensible treatment options for those patients who cannot take standard antidepressants.

Agomelatine in long term treatment

In this analysis we focused on short term efficacy studies, but of course depression is often a chronic recurring condition. Pooled analysis of four published 24 week studies suggested that agomelatine was at least as effective as treatment with an SSRI.63 Agomelatine also seems to prevent relapse of generalised anxiety disorder over a six month period.64 There is one published 24 week relapse prevention study of agomelatine14 in depression, which showed a significant advantage for agomelatine over placebo. A meta-analysis including this and two further unpublished relapse prevention studies, however, suggested no advantage for agomelatine over placebo.43 The long term benefit of agomelatine thus remains unproved.

Conclusion

In this comprehensive meta-analysis of both published and unpublished studies we have shown that agomelatine is moderately more effective than placebo and has similar efficacy to standard antidepressants. It is clear, however, that many studies of this drug with negative or equivocal results have not been published. Any meta-analysis of a less than exhaustive selection of completed studies is therefore likely to give erroneous results. Nonetheless, agomelatine’s demonstrable acute efficacy is intriguing given its unique pharmacological mode of action and good tolerability, and our findings certainly support further research into compounds possessing melatonergic activity. That agomelatine is no less effective than comparator antidepressants is also noteworthy given its relatively small risk of sexual adverse effects, insomnia, and discontinuation reactions (all commonly seen with serotonergic antidepressants). As such it serves as an appropriate alternative to these longer established antidepressants, although its relative cost, the small risk of hepatic toxicity, and need for liver function monitoring should be noted.65

What is already known on this topic

Agomelatine is a licensed antidepressant with a unique mode of action, widely used in the European Union

Previous meta-analyses have produced varied estimates of the efficacy of agomelatine because of differences in the number and type of studies included

What this study adds

The effect size for agomelatine compared with placebo is similar to that of other marketed antidepressants

Agomelatine shows similar efficacy to standard antidepressant in comparator controlled trials

Agomelatine is a valid treatment option in patients unable to tolerate adverse effects of standard antidepressants or in whom standard drugs are contraindicated

Contributors: All authors contributed to the drafting and editing of the manuscript. AS performed searching and study selection, SV extracted data and assessed risk of bias. OO contributed to searching, study selection, assessment of risk of bias, data extraction, statistical plan, and analysis. DT initiated and oversaw the research, monitored the progress, prepared the draft manuscript, and is guarantor.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare that DT has received personal fees and grants from Servier outside the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: Datasets and statistical codes are available from the corresponding author.

Declaration of transparency: The lead author affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Cite this as: BMJ 2104;348:g1888

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Appendix: Characteristics of included studies

References

- 1.European Medicines Agency. Valdoxan (agomelatine). 2012. www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/000915/human_med_001123.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124.

- 2.Racagni G, Riva MA, Molteni R, Musazzi L, Calabrese F, Popoli M, et al. Mode of action of agomelatine: synergy between melatonergic and 5-HT2C receptors. World J Biol Psychiatry 2011;12:574-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh SP, Singh V, Kar N. Efficacy of agomelatine in major depressive disorder: meta-analysis and appraisal. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2011;23:1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medawar C, Hardon A, Herxheimer A. Depressing research. Lancet 2004;363:2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner EH, Matthews AM, Linardatos E, Tell RA, Rosenthal R. Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. N Engl J Med 2008;358:252-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eyding D, Lelgemann M, Grouven U, Härter M, Kromp M, Kaiser T, et al. Reboxetine for acute treatment of major depression: systematic review and meta-analysis of published and unpublished placebo and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor controlled trials. BMJ 2010;341:c4737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960;23:56-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 1979;134:382-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman SD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Multiple comparisons within a study. In: Introduction to meta-analysis. Wiley-Blackwell, 2009:239-42.

- 11.Trowman R, Dumville JC, Torgerson DJ, Cranny G. The impact of trial baseline imbalances should be considered in systematic reviews: a methodological case study. J Clin Epidemiol 2007;60:1229-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.0. Nordic Cochrane Centre, Cochrane Collaboration, 2008.

- 13.StataCorp. Stata statistical software: release 11. StataCorp LP, 2009.

- 14.Goodwin GM, Emsley R, Rembry S, Rouillon F; Agomelatine Study Group. Agomelatine prevents relapse in patients with major depressive disorder without evidence of a discontinuation syndrome: a 24-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2009;70:1128-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kasper S, Hajak G. The efficacy of agomelatine in previously-treated depressed patients. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2010;14(suppl 1):26-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montgomery SA, Kennedy SH, Burrows GD, Lejoyeux M, Hindmarch I. Absence of discontinuation symptoms with agomelatine and occurrence of discontinuation symptoms with paroxetine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled discontinuation study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2004;19:271-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vahia V, Yadav A. Efficacy and safety of agomelatine with flexible dose (25 mg/day with blinded potential adjustment at 50 mg) given orally for 8 weeks in Indian outpatients with major depressive disorder. A randomised double-blind national multicentric study with parallel groups, versus sertraline (50 mg/day with blinded potential adjustment at 100 mg). CL3-20098-074. 2011. [Data from European Medicines Authority.]

- 18.Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. An 8-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-and paroxetine-controlled study of the efficacy, safety and tolerability of agomelatine 25 or 50mg given once daily in the treatment of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). Study CAGO178A2303. Novartis, 2008. www.novctrd.com/ctrdWebApp/clinicaltrialrepository/displayFile.do?trialResult=2659.

- 19.Servier. Report including additional analyses: efficacy and safety of agomelatine (25mg) given orally once a day for 6 weeks versus fluoxetine (20mg) in in- or out-patients with Major Depressive Disorder. A randomised double-blind, placebo controlled parallel-group study. 18 week optional treatment period. CL3-20098-022. Vol 1/36. 2007. [Data from European Medicines Authority.]

- 20.Servier. Efficacy and safety of agomelatine (25mg) given orally once a day for 6 weeks versus paroxetine, in patients with Major Depressive Disorder. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled - parallel groups study, 18-weeks extension period. CL3-20098-023. Vol 1/34. 2004. [Data from European Medicines Authority.]

- 21.Servier. Efficacy and safety of agomelatine given orally once a day for 6 weeks in patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Confirmation of the efficacy of the agomelatine 25mg dosage and study of the efficacy of agomelatine 50mg dosage. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, versus fluoxetine, parallel groups study. 18-week continuation period. CL3-20098-024. Vol 1/53. 2004. [Data from European Medicines Authority.]

- 22.Servier. Efficacy and safety of agomelatine (25mg) given orally once a day for 6 weeks in elderly patients with Major Depressive Disorder. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study with a 18-week extension period. CL3-20098-026. Vol 1/28. 2004. [Data from European Medicines Authority.]

- 23.Servier Laboratories. Study CL3-048—Agomelatine (Servier Data on File). 2008. [Unpublished results supplied by manufacturer.]

- 24.Servier Laboratories. Study CL3-052—Agomelatine (Servier Data on File). 2013. [Unpublished results supplied by manufacturer.]

- 25.Servier Laboratories. Study CL3-063—Agomelatine (Servier Data on File). 2009. [Unpublished results supplied by manufacturer.]

- 26.Servier Laboratories. Study CL3-070—Agomelatine (Servier Data on File). 2009. [Unpublished results supplied by manufacturer.]

- 27.Hale A, Corral RM, Mencacci C, Ruiz JS, Severo CA, Gentil V. Superior antidepressant efficacy results of agomelatine versus fluoxetine in severe MDD patients: a randomized, double-blind study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2010;25:305-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kasper S, Hajak G, Wulff K, Hoogendijk WJ, Motejo AL, Smeraldi E, et al. Efficacy of the novel antidepressant agomelatine on the circadian rest-activity cycle and depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder: a randomized, double-blind comparison with sertraline. J Clin Psychiatry 2010;71:109-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kennedy SH, Emsley R. Placebo-controlled trial of agomelatine in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2006;16:93-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lemoine P, Guilleminault C, Alvarez E. Improvement in subjective sleep in major depressive disorder with a novel antidepressant, agomelatine: randomized, double-blind comparison with venlafaxine. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68:1723-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loo H, Hale A, D’haenen H. Determination of the dose of agomelatine, a melatoninergic agonist and selective 5-HT(2C) antagonist, in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a placebo-controlled dose range study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2002;17:239-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olie JP, Kasper S. Efficacy of agomelatine, a MT1/MT2 receptor agonist with 5-HT2C antagonistic properties, in major depressive disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2007;10:661-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quera-Salva MA, Hajak G, Philip P, Montplaisir J, Keufer-Le Gall S, Laredo J, et al. Comparison of agomelatine and escitalopram on nighttime sleep and daytime condition and efficacy in major depressive disorder patients. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2011;26:252-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stahl SM, Fava M, Trivedi MH, Caputo A, Shah A, Post A. Agomelatine in the treatment of major depressive disorder: an 8-week, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2010;71:616-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zajecka J, Schatzberg A, Stahl S, Shah A, Caputo A, Post A. Efficacy and safety of agomelatine in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2010;30:135-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kennedy SH, Rizvi S, Fulton K, Rasmussen J. A double-blind comparison of sexual functioning, antidepressant efficacy, and tolerability between agomelatine and venlafaxine XR. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2008;28:329-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kennedy SH, Avedisova A. Efficacy and safety of 3 agomelatine dose regimens (10, 25, 25-50mg) versus placebo in out-patients suffering from moderate to severe major depressive disorder. Abstract presented at 21st European Congress of Psychiatry, Nice, France, 6-9 April 2013.

- 38.Heun R, Ahokas A, Boyer P, Giménez-Montesinos N, Pontes-Soares F, Olivier V, et al. The efficacy of agomelatine in elderly patients with recurrent Major Depressive Disorder: a placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry 2013;74:587-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lemoine P, Guilleminault C, Alvarez E. Improvement in subjective sleep in major depressive disorder with a novel antidepressant, agomelatine: randomized, double-blind comparison with venlafaxine. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68:1723-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Depression: the treatment and management of depression in adults (update). CG90. NICE, 2009. www.nice.org.uk/.

- 41.Rief W, Nestoriuc Y, Weiss S, Welzel E, Barsky AJ, Hofmann SG. Meta-analysis of the placebo response in antidepressant trials. J Affect Dis 2009;118:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kasper S, Corruble E, Hale A, Lemoine P, Montgomery SA, Quera-Silva MA. Antidepressant efficacy of agomelatine versus SSRI/SNRI: results from a pooled analysis of head-to-head studies without a placebo control. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2013;28:12-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koesters M, Guaiana G, Cipriani A, Becker T, Barbui C. Agomelatine efficacy and acceptability revisited: systematic review and meta-analysis of published and unpublished randomised trials. Br J Psychiatry 2013;203:179-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kirsch I, Deacon BJ, Huedo-Medina TB, Scoboria A, Moore TJ, Johnson BT. Initial severity and antidepressant benefits: a meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration. PLoS Med 2008;5:e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Posternak MA, Zimmerman M. Therapeutic effect of follow-up assessments on antidepressant and placebo response rates in antidepressant efficacy trials: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2007;190:287-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leucht S, Hierl S, Kissling W, Dold M, Davis JM. Putting the efficacy of psychiatric and general medicine medication into perspective: review of meta-analyses. Br J Psychiatry 2012;200:97-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Doshi P, Dickersin K, Healy D, Vedula SS, Jefferson T. Restoring invisible and abandoned trials: a call for people to publish the findings. BMJ 2013;346:f2865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kirkham JJ, Dwan KM, Altman DG, Gamble C, Dodd S, Smyth R, et al. The impact of outcome reporting bias in randomised controlled trials on a cohort of systematic reviews. BMJ 2010;340:c365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Depression with a chronic physical health problem. Clinical Guidance 91. 2009. www.nice.org.uk/CG91.

- 50.Taylor D, Paton C, Kapur S. Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. 11th ed. Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

- 51.Sparshatt A, McAllister Williams RH, Baldwin DS, Haddad PM, Bazire S, Weston E, et al. A naturalistic evaluation and audit database of agomelatine: clinical outcome at 12 weeks. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2013;128:203-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sevier Laboratories. Summary of Product Characteristics. Valdoxan. Sevier, 2013. www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/21830/SPC/Valdoxan/.

- 53.Gahr M, Freudenmann RW, Connemann BJ, Hiemke C, Schönfeldt-Lecuona C. Agomelatine and hepatotoxicity: implications of cumulated data derived from spontaneous reports of adverse drug reactions. Pharmacopsychiatry 2013;46:214-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Yellow card: drug analysis print. Drug name: agomelatine. 2013. www.mhra.gov.uk/home/groups/public/documents/sentineldocuments/dap_1382088923328.pdf.

- 55.Serretti A, Chiesa A. Treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction related to antidepressants: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2009;29:259-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Corruble E, de Bodinat C, Belaïdi C, Goodwin GM; Agomelatine Study Group. Efficacy of agomelatine and escitalopram on depression, subjective sleep and emotional experiences in patients with major depressive disorder: a 24-wk randomized, controlled, double-blind trial. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2013;16:2219-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Montejo A, Majadas S, Rizvi SJ, Kennedy SH. The effects of agomelatine on sexual function in depressed patients and healthy volunteers. Hum Psychopharmacol 2011;26:537-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hackam DG, Mrkobrada M. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and brain hemorrhage: a meta-analysis. Neurology 2012;79:1862-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hung CC, Lin CH, Lan TH, Chan CH. The association of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors use and stroke in geriatric population. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013;21:811-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Serretti A, Mandelli L. Antidepressants and body weight: a comprehensive review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2010;71:1259-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Watanabe N, Omori IM, Nakagawa A, Cipriani A, Barbui C, Churchill R, et al. Mirtazapine versus other antidepressive agents for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;12:CD006528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Taylor D, Stewart S, Connolly A. Antidepressant withdrawal symptoms-telephone calls to a national medication helpline. J Affect Disord 2006;95:129-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Demyttenaere K, Corruble E, Hale A, Quera-Salva MA, Picarel-Blanchot F, Kapser S. A pooled analysis of six month comparative efficacy and tolerability in four randomized clinical trials: agomelatine versus escitalopram, fluoxetine, and sertraline. CNS Spectr 2013;18:163-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stein DJ, Ahokas A, Albarran C, Olivier V, Allgulander C. Agomelatine prevents relapse in generalized anxiety disorder: a 6-month randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled discontinuation study. J Clin Psychiatry 2012;73:1002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Howland RH. A benefit-risk assessment of agomelatine in the treatment of major depression. Drug Saf 2011;34:709-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix: Characteristics of included studies