Abstract

Background

Pulmonary embolism (PE) may trigger atrial fibrillation through increased right atrial pressure and subsequent atrial strain, but the degree of evidence is low. In this study, we wanted to investigate the impact of incident venous thromboembolism (VTE) on future risk of atrial fibrillation in a prospective population‐based study.

Methods and Results

The study included 29 974 subjects recruited from the Tromsø study (1994–1995, 2001–2002, 2007–2008). Incident VTE and atrial fibrillation events were registered from date of enrolment to end of follow‐up, December 31, 2010. Cox proportional hazard regression models using age as time‐scale and VTE as a time‐dependent variable were used to estimate crude and multivariable hazard ratios (HRs) for atrial fibrillation with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). During 16 years of follow up, 540 (1.8%) subjects had an incident VTE event, and 1662 (5.54%) were diagnosed with atrial fibrillation. Among those with VTE, 50 (9.3%) developed subsequent atrial fibrillation. Patients with VTE had 63% higher risk of atrial fibrillation compared to subjects without VTE (multivariable‐adjusted HR: 1.63, 95% CI: 1.22 to 2.17). The risk of atrial fibrillation was particularly high during the first 6 months after the VTE event (HR 4.00, 95% CI: 2.21 to 7.25) and among those with PE (HR 1.78, 95% CI: 1.13 to 2.80).

Conclusions

We found that incident VTE was associated with future risk of atrial fibrillation. Our findings support the hypothesis that PE may lead to cardiac dysfunctions that, in turn, could trigger atrial fibrillation.

Keywords: epidemiology, fibrillation, pulmonary heart disease, thrombosis

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation is the most common cardiac arrhythmia in the general population, with a lifetime risk of 1 in 4 for persons over 40 years of age.1 It is associated with substantial medical complications, such as a 5‐fold increased risk of ischemic stroke and doubled all‐cause mortality.2 Although several risk factors for atrial fibrillation (age, male gender, hypertension, diabetes, thyroid disease, congestive heart failure, sleep apnea, and renal failure)1–2 have been identified, the major health burden posed by atrial fibrillation necessitates further investigation of predisposing conditions.

Atrial fibrillation has been extensively studied in the context of heart failure, hypertension, and acute myocardial infarction,3 but less attention has been paid to the relation between venous thromboembolism (VTE) (pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis [DVT]) and atrial fibrillation. The reported prevalence of atrial fibrillation in acute pulmonary embolism (PE) varies widely,3–6 and most studies are focused on diagnostic purposes.4–5 Moreover, as the temporal sequence of events has not been determined in these studies,3,5–6 the question of cause and effect remains unanswered.

The putative association between VTE and atrial fibrillation is strongly supported by convincing evidence for a pathophysiological link between the diseases. An acute PE increases pulmonary vascular resistance and cardiac afterload, eliciting right ventricular and atrial strain that in turn may trigger atrial fibrillation.6–7 Even in normotensive patients, right ventricle dysfunction occurs in ≈50% of PE cases on admission,8 and may persist several months after the initial thrombotic event.9–10

Despite circumstantial evidence of an association, the relationship between VTE and future atrial fibrillation has never been investigated in a prospective observational study. In our study, we aimed to investigate whether VTE was associated with risk of atrial fibrillation in a cohort study with subjects recruited from a general population.

Methods

Study Population

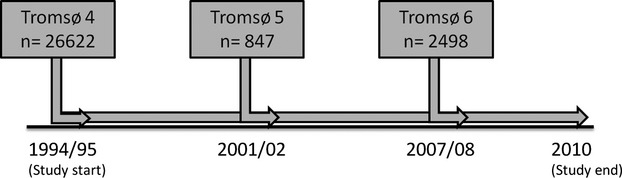

Study participants were recruited from the fourth (1994–1995), fifth (2001–2002), and sixth survey (2007–2008) of the Tromsø study. To these surveys, the entire population (Tromsø 4) or parts (Tromsø 5 and 6) of the population aged ≥25 years living in the municipality of Tromsø, Norway, were invited to participate. The overall attendance rate was high, ranging from 77% in Tromsø 4 to 66% in Tromsø 6. A total of 30 586 subjects aged 25 to 97 years participated in at least one of the surveys. A detailed description of study participation has been published elsewhere.11 The study was approved by The Regional Committee of Medical and Health Research Ethics North Norway, and all study participants provided informed written consent. Subjects who did not consent to medical research (n=225), those not officially registered as inhabitants of the municipality of Tromsø at time of enrollment (n=47), and subjects with VTE (n=76) or atrial fibrillation (n=264) prior to baseline were excluded. In total, 29 974 subjects were included in the study (Figure 1), and followed from the date of enrollment until the end of follow‐up (December 31, 2010).

Figure 1.

Inclusion of study participants (unique individuals) from the fourth, fifth, and sixth survey of the Tromsø study.

Baseline Measurements

Baseline information was collected by physical examination, nonfasting blood samples and self‐administered questionnaires. Blood pressure was recorded with an automatic device (Dinamap Vital Signs Monitor 1846; Critikon Inc) by trained personnel. Participants rested for 2 minutes in a sitting position and then 3 readings were taken on the upper right arm at 2‐minute intervals. The average of the 2 last readings was used in the analysis. Nonfasting blood samples were collected from an antecubital vein. Serum was prepared by centrifugation after a 1‐hour respite at room temperature and analyzed at the Department of Clinical Biochemistry, University Hospital of North Norway. Serum total cholesterol was analyzed by an enzymatic colorimetric method using a commercially available kit (CHOD‐PAP, Boehringer‐Mannheim). Serum HDL‐cholesterol was measured after precipitation of lower‐density lipoproteins with heparin and manganese chloride. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters (kg/m2). History of arterial cardiovascular disease (CVD) (angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, or stroke), diabetes and current smoking was obtained from a self‐administered questionnaire.

Venous Thromboembolism: Identification and Validation

All incident VTE events during follow‐up were identified by searching the hospital discharge diagnosis registry, the autopsy registry and the radiology procedure registry at the University Hospital of North Norway as previously described.12 All hospital care and relevant diagnostic radiology in the Tromsø municipality are provided exclusively by this hospital. The medical record for each potential VTE case was reviewed by trained personnel. A potential VTE event derived from the hospital discharge diagnosis registry or the radiology procedure registry, was recorded when presence of clinical signs and symptoms of DVT or PE were combined with objective confirmation tests (compression ultrasonography, venography, spiral computed tomography, perfusion‐ventilation scan, pulmonary angiography, autopsy), and resulted in a VTE diagnosis that required treatment. VTE cases from the autopsy registry were recorded when the death certificate indicated VTE as cause of death or a significant condition associated with death.

Atrial Fibrillation: Identification and Validation

Incident events of atrial fibrillation during follow‐up were identified by the hospital discharge diagnosis registry at the University Hospital of North Norway (included diagnoses from hospitalizations and outpatient clinic) and by the National Causes of Death registry, using the following International Classification of Disease version 9 (ICD‐9) codes 427.0 to 427.99 and ICD‐10 codes I47 to I48. In addition, a search through medical records of patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cerebrovascular events was performed.13 The diagnosis of atrial fibrillation had to be documented by an electrocardiogram, and adjudication of the events was performed by an independent endpoint committee. Classification of atrial fibrillation into paroxysmal and persistent versus permanent forms was performed when possible. Persons having a paroxysmal course of atrial fibrillation initially, but who later developed a permanent form, were classified as having permanent atrial fibrillation. Coexisting heart disease at the time of atrial fibrillation diagnosis (coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, valvular disease, structural changes) was recorded if present.

Statistical Analyses

Subjects who developed VTE during the study period contributed with nonexposed person time from the baseline inclusion date to the date of a diagnosis of VTE, and then with exposed person time from the date of VTE and onwards. Subjects diagnosed with incident atrial fibrillation and VTE on the same day (n=7) were excluded from the analyses because the temporal sequence of events could not be determined. For each participant, nonexposed and exposed person‐years were counted from the date of enrollment (1994–1995, 2001–2002, or 2007–2008) to the date of an incident atrial fibrillation diagnosis, the date the participant died or moved from the municipality of Tromsø, or until the end of the study period, December 31, 2010, whichever came first. Subjects who died (n=3079) or moved from Tromsø (n=4289) during follow‐up were censored at the date of migration or death.

Statistical analyses were performed with STATA version 12.0 (Stata Corporation). Cox proportional hazard regression models were used to obtain crude and multivariable adjusted hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Attained age was used as time‐scale, with subjects' age at study enrollment defined as entry‐time, and exit‐time defined as age at the censoring event (atrial fibrillation, death, migration, or study end). The exposure variable VTE was included as a time‐dependent variable using multiple observation periods per subject. That is, no subjects were registered with VTE at baseline, but the variable was updated for those who developed VTE during follow‐up. The multivariable HRs were adjusted for potential confounders including sex, BMI, smoking status, diastolic blood pressure, cholesterol levels, self‐reported CVD, and diabetes. In addition, subgroup analyses of PE and DVT as exposure variables for atrial fibrillation were performed. Since the incidence of both VTE and atrial fibrillation highly increases with age, we also did age‐stratified analyses to explore the effect of VTE on atrial fibrillation in various age groups. A test of the proportional hazard assumption using Schoenfeld residuals revealed that VTE violated the assumption of proportional hazard. HRs in different time intervals after the VTE event were therefore calculated. Statistical interactions between VTE and sex or age were tested by including cross‐product terms in the proportional hazard model. No statistical interactions between VTE and sex or age were found. Correct assessment of the temporal sequence of events was especially important in this study because VTE can be both the cause and the consequence of atrial fibrillation, and patients can present with the 2 conditions concomitantly. In the main analysis all incident atrial fibrillation events that occurred ≥1 day after the diagnosis of VTE were considered as potentially caused by the VTE. In addition, analyses excluding atrial fibrillation events occurring only in the presence of surgery or MI were performed.

Results

Among 29 967 participants, 540 subjects were diagnosed with VTE (crude IR: 1.48 [95% CI: 1.36 to 1.60] per 1000 person‐years) and 1662 subjects were diagnosed with atrial fibrillation (crude IR 4.60 [95% CI: 4.39 to 4.83] per 1000 person‐years) during a median of 15.7 years of follow‐up. There were 50 (9.3%) subjects who experienced subsequent atrial fibrillation after a VTE event, while 1612 (5.5%) were diagnosed with atrial fibrillation among subjects without VTE during follow‐up.

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics for subjects with VTE and subsequent atrial fibrillation, those with VTE only, those with atrial fibrillation only, and for those with neither VTE nor atrial fibrillation during follow‐up. Among those with atrial fibrillation only, 55.7% were men, while of those with subsequent atrial fibrillation after a diagnosis of VTE only 42% were men. Those with atrial fibrillation only and those with VTE and subsequent atrial fibrillation were on average >20 years older than those with neither VTE nor atrial fibrillation. BMI, total cholesterol, and blood pressure were highest among those with VTE and atrial fibrillation, followed by those with atrial fibrillation only, those with VTE only, and the lowest mean values were registered among those with no events. Self‐reported cardiovascular disease and diabetes were most frequent among those with atrial fibrillation with or without a preceding event of VTE.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Subjects Without VTE With/Without Atrial Fibrillation During Follow‐up and of Subjects With VTE During Follow‐up With/Without Subsequent Atrial Fibrillation During Follow‐up

| No VTE During Follow‐up | VTE During Follow‐up | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Atrial Fibrillation | Atrial Fibrillation | No Atrial Fibrillation | Subsequent Atrial Fibrillation | |

| Subjects, n | 27 815 | 1612 | 490 | 50 |

| Sex (male), % | 47.0 (13 065) | 55.7 (898) | 46.3 (227) | 42.0 (21) |

| Age, y | 45.2±14.0 | 64.0±11.7 | 56.8±14.2 | 68.3±9.4 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.2±3.9 | 26.9±4.3 | 26.7±4.4 | 29.2±4.0 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 5.93±1.29 | 6.68±1.24 | 6.56±1.35 | 6.94±1.18 |

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.49±0.41 | 1.51±0.44 | 1.51±0.43 | 1.51±0.38 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 132±20 | 152±24 | 141±22 | 159±21 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 77±12 | 86±14 | 81±13 | 88±13 |

| Smoking, % | 36.5 (10 121) | 27.3 (439) | 32.7 (160) | 22.0 (11) |

| Self‐reported CVD*, % | 4.9 (1362) | 23.4 (376) | 11.0 (54) | 22.0 (11) |

| Self‐reported diabetes, % | 1.6 (448) | 5.3 (85) | 2.5 (12) | 6.0 (3) |

Values are given as percentages with absolute numbers in brackets or as means±standard deviations. BMI indicates body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Self‐reported history of cardiovascular disease (angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, or stroke).

The characteristics of the incident atrial fibrillation events (n=1662) during follow‐up are shown in Table 2. Coronary artery disease was more prevalent in subjects who did not experience a VTE event, while the percentages of subjects with heart failure, valvular heart disease or structural heart changes were similar between the 2 groups.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Incident Atrial Fibrillation Events (n=1662) During Follow‐Up: The Tromsø Study

| No VTE, % (n) | VTE, % (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Atrial fibrillation | 1612 | 50 |

| Paroxystic/persistent* | 40.5 (653) | 50.0 (25) |

| Permanent | 37.0 (596) | 40.0 (20) |

| Post‐operative AF* | 9.8 (158) | 2.0 (1) |

| Post‐MI AF* | 5.0 (80) | — |

| Cardiac risk factors | ||

| Coronary artery disease* | 42.0 (677) | 26.0 (13) |

| Heart failure* | 16.1 (259) | 16.0 (8) |

| Valvular heart disease | 15.7 (253) | 16.0 (8) |

| Structural heart changes | 8.2 (132) | 8.0 (4) |

| No known heart disease | 34.6 (557) | 48.0 (24) |

AF indicates atrial fibrillation; ICD, International Classification of Disease; MI, myocardial infarction.

Atrial fibrillation events were characterized as paroxystic/persistent or permanent when possible.

Within 28 days of surgery.

Within 28 days of an acute myocardial infarction.

Previous myocardial infarction and/or atherosclerosis verified by coronary angiography.

Consensus diagnosis based on information from medical journals, radiology reports, echocardiographic findings, and ICD‐10 codes.

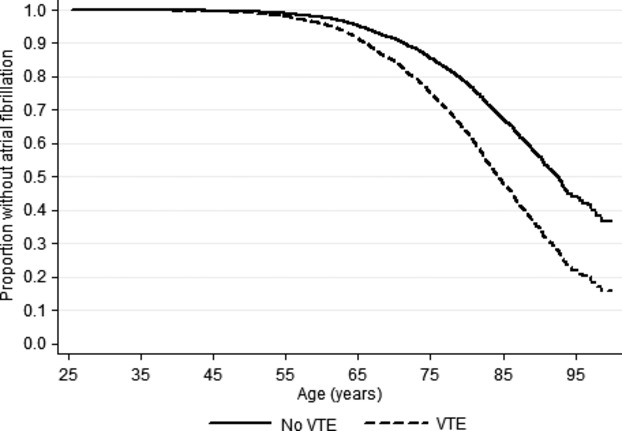

Incidence rates and hazard ratios for atrial fibrillation in subjects who developed VTE compared to subjects without VTE during follow‐up are presented in Table 3, and atrial fibrillation free survival curve for those with and without VTE are shown in Figure 2. Subjects with VTE had a 1.8‐fold higher risk of atrial fibrillation compared with those without VTE. Similar risk estimates were found in multivariable adjusted analyses (HR: 1.63, 95% CI: 1.22 to 2.17). Separate analyses for PE and DVT showed that PE was associated with higher relative and absolute risks for atrial fibrillation than DVT (Table 3). A PE event during follow‐up was associated with a 1.8‐fold higher risk (HR: 1.78, 95% CI: 1.13 to 2.80), and a DVT event was associated with 1.5‐fold increased risk (HR: 1.51, 95% CI: 1.05 to 2.18) of atrial fibrillation compared to those without VTE during follow‐up (Table 3).

Table 3.

Incidence Rates and Hazard Ratios for Atrial Fibrillation in Subjects Developing VTE, PE and DVT During Follow‐up Compared to Subject Without VTE During Follow‐up

| Person‐Years | AF Events | Crude IR (95% CI) | Model 1*, HR (95% CI) | Model 2*, HR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total VTE | |||||

| No VTE | 358 845 | 1612 | 4.5 (4.3 to 4.7) | Ref | Ref |

| VTE | 2234 | 50 | 22.4 (17.0 to 29.5) | 1.84 (1.39 to 2.44) | 1.63 (1.22 to 2.17) |

| PE | |||||

| No VTE | 356 211 | 1612 | 4.5 (4.3 to 4.8) | Ref | Ref |

| PE | 723 | 19 | 26.3 (16.8 to 41.2) | 2.08 (1.32 to 3.28) | 1.78 (1.13 to 2.80) |

| DVT | |||||

| No VTE | 356 950 | 1612 | 4.5 (4.3 to 4.7) | Ref | Ref |

| DVT | 1511 | 31 | 20.5 (14.4 to 29.2) | 1.69 (1.18 to 2.41) | 1.51 (1.05 to 2.18) |

AF indicates atrial fibrillation; CI, confidence interval; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; HR, hazard ratio; IR, incidence rate; PE, pulmonary embolism; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Using age as time scale.

Using age as times.

Figure 2.

Atrial fibrillation free survival in subjects with and without venous thromboembolism (VTE). The Tromsø study 1994‐2010.

Subjects with VTE and atrial fibrillation were substantially older than those without atrial fibrillation. Therefore, we additionally conducted age‐stratified analyses to explore whether the association was still present in various age groups. In those younger than 65 years the HR of AF after a VTE was 1.95 (95% CI: 0.81 to 4.73) compared to those without a VTE, whereas in those above 65 years the HR was 1.83 (95% CI: 1.36 to 2.46). If the cut‐off was set at age 75 years, the HR of AF after VTE was 1.88 (95% CI: 1.16 to 3.05) in those younger than 75, and 1.82 (95% CI: 1.28 to 2.58) in those older than 75 years (data not shown).

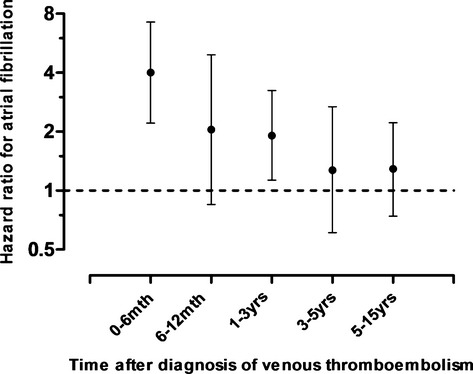

Figure 3 displays the age‐ and sex‐adjusted hazard ratios for atrial fibrillation at different time intervals after a VTE diagnosis. In the first 6 months, VTE patients had a 4‐fold higher risk of atrial fibrillation compared with subjects without VTE (HR: 4.00, 95% CI: 2.21 to 7.25). The hazard ratio declined steeply the first year after VTE diagnosis, but remained significantly elevated in the first 3 years after the thrombotic event.

Figure 3.

Age‐ and sex‐adjusted hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals for atrial fibrillation at different time intervals after a diagnosis of venous thromboembolism.

There were 239 cases of atrial fibrillation that occurred within 28 days after surgery or myocardial infarction. When these cases were excluded, the risk of atrial fibrillation in VTE subjects was higher, with a HR of 1.80 (95% CI: 1.35 to 2.42) in multivariable adjusted analyses (data not shown).

Discussion

In the present study, we found that patients with VTE had increased risk of subsequent atrial fibrillation. Overall, subjects with VTE had a 1.6‐fold higher risk of atrial fibrillation compared with those without VTE, and the risk was especially high in the first 6 months after the thromboembolic event. PE was associated with higher relative and absolute risks for atrial fibrillation than DVT.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first cohort study to show that VTE is associated with subsequent risk of atrial fibrillation in a general population. As this is an observational study, we cannot draw any conclusions on the pathophysiology behind this finding. However, the mechanistic basis of such an association is supported in the literature. An acute PE increases pulmonary vascular resistance and right ventricular afterload by obstructing pulmonary arteries and triggering the release of vasoconstrictive mediators.7 Consequently, the increase in right ventricular and atrial pressures elicits stretch injuries that, in turn, can trigger atrial fibrillation.7–8 Atrial fibrillation in acute PE patients likely reflects the degree of right ventricular failure and hemodynamic compromise.14 Even in hemodynamically stable patients, an acute PE frequently presents with pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular dysfunction.15–16 Right ventricular dysfunction was also found to be an independent predictor of atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure.17 The incidence of atrial fibrillation in patients with right ventricular dysfunction was 39% as compared with 12% of patients with normal right ventricular function.17

A feared complication of acute PE is development of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH), in which a mean pulmonary artery pressure >25 mm Hg persists 6 months after a PE diagnosis, resulting in chronic right ventricular pressure overload.18 In a retrospective analysis of 231 patients with pulmonary hypertension including CTEPH patients, the annual incidence of supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) was 3%, with atrial fibrillation and flutter being the most common types of SVT.19 Furthermore, although the majority of PE survivors do not develop overt CTEPH, several studies show long‐term right ventricular abnormalities and functional limitations in a significant number of PE cases.9–10,20 In a study by Kline and coworkers, elevated right ventricle systolic pressure persisted 6 months after a PE in 50% of the patients, often accompanied by dyspnea at rest or exercise intolerance.9 It is plausible that these morphological and functional changes may result in atrial fibrillation. Dilatation of the tricuspid valve annulus and resultant tricuspid regurgitation is frequently seen in patients with elevated pulmonary artery pressure. As the right atrium dilates to accommodate the regurgitant volume, fibrosis may ensue, creating foci for reentry and thus, atrial fibrillation.7 We found atrial fibrillation risk to be highest in the first 6 months after the thrombotic event, but it remained elevated several years after VTE.

In our study, subjects with an isolated DVT had higher risk of atrial fibrillation compared to subjects without a VTE event. As clinically silent PE is present in ≈30% of DVT cases,21 undiagnosed concurrent PE events may account for the higher atrial fibrillation risk observed among the DVT patients. Shared environmental, genetic, or other risk factors for VTE and atrial fibrillation may also contribute to the observed association. In a study by Poli and co‐workers, the prevalence of the prothrombin gene variant (G20210A), a known VTE risk factor, was about 2‐fold higher in atrial fibrillation patients compared with healthy controls.22 An Italian case report found subclinical hyperthyroidism to both trigger paroxystic atrial fibrillation and induce a hypercoagulable state with resulting VTE.23

Major strengths of this study include the large number of participants recruited from a general population, the high attendance rate, the prospective design and the measurements of potential confounders. We cannot exclude that undetected atrial fibrillation episodes prior to the recorded VTE event may have biased our risk estimates. However, a rigorous validation scheme of exposure and outcome variables was used to establish the temporal sequence of events as accurately as possible. Some limitations merit consideration. As many episodes of atrial fibrillation are asymptomatic,24 an underestimation of the true incidence of atrial fibrillation in our study population is possible. Furthermore, potential confounders such as BMI and co‐morbidities were assessed at baseline inclusion only, and these factors may have changed over time.

In conclusion, patients with venous thromboembolism had a higher risk of atrial fibrillation, particularly during the first 6 months after the incident VTE event. Our findings support the concept that right ventricular pressure overload causes persistent right‐sided ventricular dysfunction and strain, resulting in atrial stretch and subsequent fibrillation.

Sources of Funding

Drs Hald, Braekkann, and Hansen receive grants from the Northern Norwegian Regional Health Authority.

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Kannel WB, Benjamin EJ. Status of the epidemiology of atrial fibrillation. Med Clin North Am. 2008; 92:17-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GY, Schotten U, Savelieva I, Ernst S, Van Gelder IC, Al‐Attar N, Hindricks G, Prendergast B, Heidbuchel H, Alfieri O, Angelini A, Atar D, Colonna P, De Caterina R, De Sutter J, Goette A, Gorenek B, Heldal M, Hohloser SH, Kolh P, Le Heuzey JY, Ponikowski P, Rutten FH. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the task force for the management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2010; 31:2369-2429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koracevic G, Atanaskovic V. Is atrial fibrillation a prognosticator in acute pulmonary thromboembolism? Med Princ Pract. 2010; 19:166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stein PD, Dalen JE, McIntyre KM, Sasahara AA, Wenger NK, Willis PW., III The electrocardiogram in acute pulmonary embolism. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1975; 17:247-257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barra SN, Paiva LV, Providencia R, Fernandes A, Leitao Marques A. Atrial fibrillation in acute pulmonary embolism: prognostic considerations. Emerg Med J. 2013. 10.1136/emermed‐2012‐202089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gex G, Gerstel E, Righini M, Le Gal G, Aujesky D, Roy PM, Sanchez O, Verschuren F, Rutschmann OT, Perneger T, Perrier A. Is atrial fibrillation associated with pulmonary embolism? J Thromb Haemost. 2012; 10:347-351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matthews JC, McLaughlin V. Acute right ventricular failure in the setting of acute pulmonary embolism or chronic pulmonary hypertension: a detailed review of the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2008; 4:49-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torbicki A, Perrier A, Konstantinides S, Agnelli G, Galie N, Pruszczyk P, Bengel F, Brady AJ, Ferreira D, Janssens U, Klepetko W, Mayer E, Remy‐Jardin M, Bassand JP. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism: the task force for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2008; 29:2276-2315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kline JA, Steuerwald MT, Marchick MR, Hernandez‐Nino J, Rose GA. Prospective evaluation of right ventricular function and functional status 6 months after acute submassive pulmonary embolism: frequency of persistent or subsequent elevation in estimated pulmonary artery pressure. Chest. 2009; 136:1202-1210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevinson BG, Hernandez‐Nino J, Rose G, Kline JA. Echocardiographic and functional cardiopulmonary problems 6 months after first‐time pulmonary embolism in previously healthy patients. Eur Heart J. 2007; 28:2517-2524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobsen BK, Eggen AE, Mathiesen EB, Wilsgaard T, Njolstad I. Cohort profile: the Tromso study. Int J Epidemiol. 2012; 41:961-967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braekkan SK, Borch KH, Mathiesen EB, Njolstad I, Wilsgaard T, Hansen JB. Body height and risk of venous thromboembolism: the Tromso study. Am J Epidemiol. 2010; 171:1109-1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nyrnes A, Mathiesen EB, Njolstad I, Wilsgaard T, Lochen ML. Palpitations are predictive of future atrial fibrillation. An 11‐year follow‐up of 22,815 men and women: the Tromso study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2013; 20:729-736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geibel A, Zehender M, Kasper W, Olschewski M, Klima C, Konstantinides SV. Prognostic value of the ECG on admission in patients with acute major pulmonary embolism. Eur Respir J. 2005; 25:843-848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ten Wolde M, Sohne M, Quak E, Mac Gillavry MR, Buller HR. Prognostic value of echocardiographically assessed right ventricular dysfunction in patients with pulmonary embolism. Arch Intern Med. 2004; 164:1685-1689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Golpe R, Perez‐de‐Llano LA, Castro‐Anon O, Vazquez‐Caruncho M, Gonzalez‐Juanatey C, Veres‐Racamonde A, Iglesias‐Moreira C, Farinas MC. Right ventricle dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension in hemodynamically stable pulmonary embolism. Respir Med. 2010; 104:1370-1376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aziz EF, Kukin M, Javed F, Musat D, Nader A, Pratap B, Shah A, Enciso JS, Chaudhry FA, Herzog E. Right ventricular dysfunction is a strong predictor of developing atrial fibrillation in acutely decompensated heart failure patients, ACAP‐HF data analysis. J Cardiac Fail. 2010; 16:827-834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldhaber SZ, Bounameaux H. Pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis. Lancet. 2012; 379:1835-1846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tongers J, Schwerdtfeger B, Klein G, Kempf T, Schaefer A, Knapp JM, Niehaus M, Korte T, Hoeper MM. Incidence and clinical relevance of supraventricular tachyarrhythmias in pulmonary hypertension. Am Heart J. 2007; 153:127-132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ciurzynski M, Kurzyna M, Bochowicz A, Lichodziejewska B, Liszewska‐Pfejfer D, Pruszczyk P, Torbicki A. Long‐term effects of acute pulmonary embolism on echocardiographic Doppler indices and functional capacity. Clin Cardiol. 2004; 27:693-697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stein PD, Matta F, Musani MH, Diaczok B. Silent pulmonary embolism in patients with deep venous thrombosis: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2010; 123:426-431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poli D, Antonucci E, Cecchi E, Betti I, Valdre L, Mugnaini C, Alterini B, Morettini A, Nozzoli C, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Prisco D. Thrombophilic mutations in high‐risk atrial fibrillation patients: high prevalence of prothrombin gene G20210A polymorphism and lack of correlation with thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost. 2003; 90:1158-1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patane S, Marte F, Curro A, Cimino C. Recurrent acute pulmonary embolism and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation associated with subclinical hyperthyroidism. Int J Cardiol. 2010; 142:e25-e26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Savelieva I, Camm AJ. Clinical relevance of silent atrial fibrillation: prevalence, prognosis, quality of life, and management. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2000; 4:369-382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]