Abstract

Background

Although similar to cancer patients regarding symptom burden and prognosis, patients with heart failure (HF) tend to receive palliative care far less frequently. We sought to explore factors perceived by cardiology, primary care, and palliative care providers to impede palliative care referral for HF patients.

Methods and Results

We conducted semistructured interviews regarding (1) perceived needs of patients with advanced HF; (2) knowledge, attitudes, and experiences with specialist palliative care; (3) perceived indications for and optimal timing of palliative care referral in HF; and (4) perceived barriers to palliative care referral. Two investigators analyzed data using template analysis, a qualitative technique. We interviewed 18 physician, nurse practitioner, and physician assistant providers from 3 specialties: cardiology, primary care, and palliative care. Providers had limited knowledge regarding what palliative care is, and how it can complement traditional HF therapy to decrease HF‐related suffering. Interviews identified several potential barriers: the unpredictable course of HF; lack of clear referral triggers across the HF trajectory; and ambiguity regarding what differentiates standard HF therapy from palliative care. Nevertheless, providers expressed interest for integrating palliative care into traditional HF care, but were unsure of how to initiate collaboration.

Conclusions

Palliative care referral for HF patients may be suboptimal due to limited provider knowledge and misperceptions of palliative care as a service reserved for those near death. These factors represent potentially modifiable targets for provider education, which may help to improve palliative care referral for HF patients with unresolved disease‐related burden.

Keywords: health care, health disparities, health services research, healthcare access, heart failure

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a prevalent chronic disease characterized by high physical and psychosocial burdens that dramatically impair patients' quality of life and performance status.1–4 Current HF therapies relieve symptoms and prolong survival, but are not curative.5

Specialist palliative care is a multidisciplinary intervention that focuses on optimizing quality of life for patients and families affected by serious illness, independent of prognosis.6 It is related to, but distinct from hospice, which in the United States, is restricted to patients with a maximum expected prognosis of 6 months. Nonhospice palliative care may be initiated at any point in the disease trajectory and in conjunction with curative or life‐prolonging treatments. In this study, we considered palliative care as the service delivered by care teams with specialty expertise. Specialist palliative care includes: expert symptom identification and management; psychological, spiritual, and logistical support; assistance with treatment decision‐making and setting care goals; and complex care coordination.7 Palliative care has been shown to improve survival,8 quality of life,8–9 symptom burden,10–11 and caregiver outcomes,12–13 as well as reduce healthcare expenditures,7 and hospitalizations14 for patients with serious illness; to date, the bulk of this research has focused on patients with cancer. Nevertheless, the role of palliative care for patients with nonmalignant illnesses, including HF, remains somewhat undefined. Growing evidence supports the role of palliative care in reducing distress among patients with HF. For example, a recent case‐control study of outpatient palliative care consultations found reduced symptom burden and improved quality of life,15 while another study suggests improved satisfaction with care among Stage D HF patients receiving palliative care consultations.16 Additionally, palliative care may hold particular promise in HF management as a mechanism of advance care planning and goals‐of‐care identification; this is especially salient recognizing that 80% of Medicare beneficiaries with HF are hospitalized within the last 6 months of life.17

The 2013 HF management guidelines of the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association recommend considering palliative care across the HF trajectory, with particular focus paid to patients with advanced symptomatic HF and during inpatient discharge planning.18 In parallel, others have similarly called for palliative care integration within standard HF management.5,19–25 However, despite similar symptom burden and prognosis as advanced cancer patients,3–4,3–28 HF patients use palliative services less often than cancer patients.29 Provider behavior may contribute to underuse: in one study, more than half of cardiologists surveyed would not discuss palliative care with elderly advanced HF patients.30 Several additional factors appear to be related to the low rates of palliative care enrollment by HF patients, including: the unpredictable disease trajectory of HF5,19,31; the view of HF as a chronic, manageable disease5,19,32; and patient and caregiver confusion regarding prognosis.33–34 Prior qualitative studies exploring palliative care referral barriers for patients with HF in the United Kingdom and Australia suggest organizational, professional, and cognitive factors potentially at play.31–34 Recognizing differences in healthcare systems and culture, we conducted an exploratory qualitative study with primary care, cardiology, and palliative care providers to uncover potential barriers to palliative care referral for HF patients in the United States.

Methods

Design

We conducted semistructured interviews to allow flexibility in exploring topics. Participants electronically provided informed consent. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Sample and Recruitment

We used stratified purposeful sampling35 to recruit primary care, cardiology, and palliative care physicians and nonphysician providers from diverse practice settings (ie, academic/non‐academic, urban/rural). Chain referral was used to allow participants to suggest colleagues who might provide valuable insights based on clinical experience and expertise; study coauthors also suggested potential participants. Eligibility criteria were (a) physician, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant; (b) practicing in North Carolina; and (c) cared for ≥3 HF patients in the preceding 6 months. We offered a $50 honorarium.

Data Collection

One author (DK) conducted all interviews, in person or by telephone, between December 2011 and May 2012. Based upon a literature review regarding HF care transitions and discussions with 3 experts, we developed an interview guide (Table 1) containing 10 questions in 4 domains: needs of HF patients; knowledge and perceptions of palliative care; indications for, and optimal timing of, palliative care referral in HF; and barriers to palliative care referral in HF. To increase validity, we developed probes for “iterative questioning” to further explore providers' responses.36

Table 1.

Semistructured Interview Guide: Domains of Interest and Sample Questions

| Domain of Interest | Sample Question |

|---|---|

| Needs of heart failure patients | On the whole, what needs do your heart failure patients possess? |

| How effective do you believe that you are in managing your heart failure patients' needs? | |

| Knowledge and perceptions of palliative care | What is your familiarity with palliative care? How do you define it? |

| Throughout our conversation, I've been using the term “palliative care,” and I've been hearing you use the term “hospice.” Are those interchangeable for you, or do you see a distinction between them? | |

| Can palliative care be helpful in the management of heart failure patients? If so, how? If not, why not? | |

| Indications for, and optimal timing of, palliative care referral in heart failure | In your opinion, what makes a heart failure patient eligible for palliative care? |

| In your opinion what makes a heart failure patient appropriate for palliative care? | |

| Barriers to palliative care referral in heart failure | What are some of the barriers that you believe might be impeding the uptake of palliative care in heart failure? |

| If you suspect that a heart failure patient can benefit from palliative care, who do you believe is responsible for having this discussion [with the patient]? |

Prior to the interview, participants reviewed a vignette of a patient with advanced HF, typical comorbidities, and unaddressed palliative needs (Table 2). Such elicitation methods may be helpful when exploring values and perceptions.37 Participants completed a survey collecting demographics as well as self‐reported information about their HF patient caseload. Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim.

Table 2.

Hypothetical Heart Failure Patient Vignette Used to Frame Interviews

| Characteristic | ||

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | 67‐year‐old, white male; married, 2 nonlocal children | |

| History | ● 3 hospitalizations within the past year for acute HF decompensation events ● History of ST elevation myocardial infarct 5 years ago followed by coronary artery bypass grafting ● On recent cardiac catheterization, has multivessel coronary artery disease with all grafts patent ● No ischemia on stress testing and no angina symptoms |

|

| BMI | 34.5 kg/m2 | |

| Ejection fraction | 18% | |

| Transplantation | Carefully reviewed by transplantation team and deemed ineligible for cardiac transplantation or other cardiac surgery due to age, kidney disease, and insulin‐dependent diabetes | |

| Dyspnea | 9/10 on exertion; 3/10 at rest | |

| Orthopnea | 4‐pillow orthopnea | |

| Edema | Reports worsening bilateral lower extremity edema over the last 2 weeks | |

| Pain | 5/10 over the past 2 weeks, in both legs and limiting walking | |

| Depression | Moderate over the past 2 weeks | |

| Physical exam | Vitals: SBP 88, HR 80 Neck: JVP elevated 10 cm Irregular rate, 3/6 systolic murmur consistent with mitral regurgitation Lungs with bilateral rales at both bases Abdomen normal Extremities: bilaterally edema, 2/4, pitting |

|

| NT‐ProBNP | 2100 pg/mL | |

| Devices | Implantable biventricular pacemaker—cardioverter‐defibrillator; ventricular resynchronization×3 years (not recent) | |

| Comorbidities | ● Atrial fibrillation ● Major depression ● Chronic kidney disease, stage 3, creatinine 2.5 mg/dL and has increased from 2.0 in the past 2 months ● Hypertension; recently with hypotension due to heart failure and has not tolerated higher doses of antihypertensive medications ● Type II diabetes mellitus |

|

| Current medications | ● Lisinopril 5 mg QD ● Furosemide 80 mg BID ● Carvedilol 3.125 mg BID ● Spironolactone 12.5 mg QD |

● Insulin lispro ● Humulin n ● Bupropion xl 300 mg QD ● Warfarin |

BID indicates twice daily; BMI, body mass index; HF, heart failure; HR, heart rate; JVP, jugular venous pressure; NT‐ProBNP, N‐terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic protein; QD, daily; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Analysis

We used template analysis, a qualitative approach that combines content analysis and grounded theory.38 Template analysis flexibly integrates a priori assumptions and hypotheses for a hybrid inductive/deductive analytic process. Data analysis was performed iteratively, with the initial codebook informed by an extensive literature review. Two authors (DK, EMM) independently coded a random 50% sample of transcripts in 3 rounds. After each round, consensus meetings were held to discuss and arbitrate discrepancies. DK coded all remaining transcripts, which EMM reviewed and verified. Using the constant comparative technique, text units were compared with previously coded data to ensure stability and relevance of themes.39 We used NVivo9 (version 9, QSR International) to code and query transcripts. To further explore our data, we performed matrix and compound queries. We applied 9 techniques (Table 3) to improve the trustworthiness of our findings across 4 domains: credibility; transferability; dependability; and confirmability.36,40–42 Regarding saturation, we followed the guidance of Strauss and Corbin, who suggest ceasing data collection when additional interviews do not significantly expand upon prior findings.43 As a method of quality assurance, we compared every additional interview to prior interviews, scrutizing the degree of theme overlap versus marginal gain.

Table 3.

Techniques Used to Ensure Qualitative Rigor and Trustworthiness of Findings

| Aspect | Technique | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Credibility How reflective of reality are the research findings? |

Field observation | DK observed patient encounters in heart failure clinics and palliative care home visits during study design. |

| Iterative questioning36 | We employed deliberate, explicit probes in order to understand participants' responses with greater precision. | |

| Expert review of protocol | Disciplinary experts assisted in the development of the interview guide and patient vignette. | |

| Frequent debriefing | Weekly meetings were held between the lead and senior authors to discuss findings and concerns. | |

| Transferability How applicable are the research findings to other contexts or situations? |

Contextual review | We performed a detailed literature review to understand the context within which our work falls. |

| Dependability How reproducible are the research findings? |

Audit trail | We maintained an extensive audit trail throughout the analytic process, detailing decision rules and justifications. |

| Confirmability How objective was the analysis? |

Bracketing42 | Recognition of investigators' preconceptions and assumptions regarding the phenomena of interest. |

| Triangulation | Investigator triangulation (ie, multiple researchers analyzed data) and disciplinary triangulation (ie, researchers represented a variety of related expertise). | |

| Member checking41 | Interview participants were invited to review this manuscript before submission for publication. |

Results

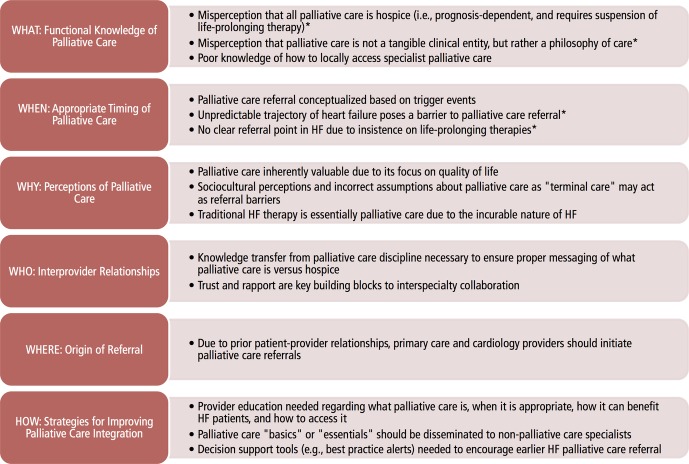

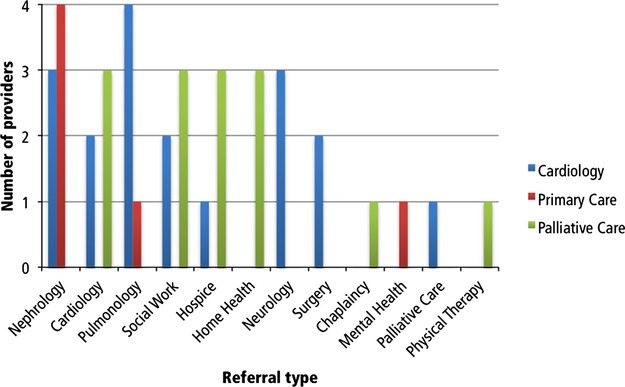

Of 22 individuals contacted, 19 agreed to participate; we interviewed 18. Within each specialty, we interviewed 4 physicians and 2 nonphysician providers (Table 4). All but one participant had both inpatient and outpatient palliative care services within their geographic area (data not shown). Participants represented 2 academic medical centers, the Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and community‐based non‐academic practices. Providers served a mix of inpatient and outpatient settings. Interviews lasted a median of 37 minutes (range: 25 to 51). During analysis, we allowed themes to naturally emerge from interview data; coincidentally, we discovered a latent “what, when, why, who, where, and how” structure to the themes (Figure 1). This organizational framework was applied once all themes had been identified, and not a priori. Common referrals made by participants for their patients with HF are displayed in Figure 2.

Table 4.

Characteristics of Study Participants

| Characteristic | Full Sample, n (%) | Cardiology, n (%) | Primary Care, n (%) | Palliative Care, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 18 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Age, median [range], years | 42.5 [27 to 57] | 39.5 [33 to 56] | 46 [35 to 55] | 52.5 [27 to 57] |

| Female | 11 (61) | 3 (50) | 3 (50) | 5 (83) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 16 (89) | 4 (67) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) |

| African American | 1 (5) | 1 (17) | — | — |

| Asian | 1 (5) | 1 (17) | — | — |

| Years in practice, median [range] | 12 [2 to 38] | 9.5 [2 to 23] | 16.5 [7 to 32] | 23 [3 to 38] |

| Practice setting | ||||

| Academic | 12 (67) | 4 (67) | 6 (100) | 2 (33) |

| Nonacademic | 5 (28) | 1 (17) | — | 4 (67) |

| Both | 1 (6) | 1 (17) | — | — |

| Provider type | ||||

| Physician | 12 (67) | 4 (67) | 4 (67) | 4 (67) |

| Nurse practitioner | 3 (18) | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 1 (17) |

| Physician assistant | 3 (18) | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 1 (17) |

| Current HF caseload, patients | ||||

| 0 | 1 (6) | — | — | 1 (20) |

| 1 to 10 | 5 (28) | — | 2 (33) | 3 (50) |

| 11 to 25 | 3 (18) | — | 2 (33) | 2 (40) |

| 26 to 50 | 3 (18) | 2 (33) | 1 (17) | — |

| 51 to 100 | 2 (12) | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | — |

| >100 | 3 (18) | 3 (50) | — | — |

| HF caseload in past year, patients | ||||

| 1 to 10 | 3 (18) | — | 3 (50) | — |

| 11 to 25 | 2 (12) | — | 1 (17) | 1 (20) |

| 26 to 50 | 5 (29) | 1 (17) | 2 (33) | 2 (40) |

| 51 to 100 | 2 (12) | — | — | 2 (40) |

| >100 | 5 (29) | 5 (83) | — | — |

Columns may not total 100% due to rounding and missing data. HF indicates heart failure.

Figure 1.

Qualitative themes identified related to palliative care referral for patients with heart failure (HF). Asterisks denote misperceptions that likely indicate confusion between non‐hospice palliative care and hospice care.

Figure 2.

Referrals commonly made by interview participants for patients with heart failure.

“What”: Lack of Functional Knowledge Regarding Palliative Care

Although all providers reported that they could define palliative care, probing revealed variation across cardiology and primary care providers. Specifically, nearly all primary care and cardiology providers lacked clarity that palliative care is not prognosis dependent and may be administered concurrently with life‐prolonging therapy. Many cardiology and primary care providers failed to recognize specialist palliative care as a tangible clinical service. For example, a primary care physician said: “Palliative care is a philosophy. Hospice is a treatment approach complete with billables, and payers, and all that crap, within that treatment philosophy.” When asked to describe eligibility and appropriateness criteria for palliative care (for which there are none, aside from patient need), cardiology and primary care providers used the terms “hospice” and “palliative care” interchangeably unless prompted for clarification.

Interviewer:

So in your opinion, what makes a HF patient eligible for palliative care?

Cardiologist:

Well, eligibility is not my decision. I mean, that's a legislative decision….

Interviewer:

And, so in your mind, is there a distinction between palliative care and hospice care?

Cardiologist:

No. Not in my mind. Is there?

Incorrectly believing that palliative care mandates suspension of life‐prolonging therapies, cardiology and primary care providers reported that patient goals determine eligibility:

… If the patient wants to focus on symptoms and is willing to accept the sort of basics … then the patient's eligible for palliative care. (Primary care physician)

Some cardiology and primary care providers recognized differences between palliative care and hospice. For example:

… I think I'm reasonably familiar [with palliative care], but I also think that to me, it's become somewhat of a confusing term … I see it as something distinct from, say, hospice care. I worry that sometimes we confuse palliative care, meaning it has to equal end‐of‐life care. I prefer to view palliative care as clear management of symptoms and emphasis of the patient's quality of life in decision‐making. (Primary care physician)

Most nonpalliative care providers lacked experience with specialist palliative care providers/teams. They frequently acknowledged not knowing how to access palliative care; a primary care physician from a large academic medical center said:

I don't even know where they are or where they exist, or even really what they do … I wouldn't even know where to start to try and get in touch with someone.

“When”: Appropriate Timing for Palliative Care Referral

Most providers based referral on “triggers,” including physiological findings (eg, symptom presence), disease status (eg, functional decline), or events (eg, device implantation). Among primary and palliative care providers, repeated hospitalizations over a short interval (eg, 3 in 6 months) suggested that palliative care might be appropriate. However, cardiology providers frequently discussed the “point at which you are unable to do more” as another trigger:

… I think that the trigger to get [the palliative care service] involved was knowing that my patient was dying and that I didn't have other medical options for them. Meaning that they weren't candidates for advanced therapies and that there was nothing else I could do to alter the natural history of the disease … (Cardiologist)

The unpredictable trajectory of HF was a frequently cited barrier, especially when providers believed that palliative care eligibility or reimbursement were dependent upon prognosis (as with hospice). Moreover, some providers spoke of the difficulty of recognizing and acting upon triggers:

…I think the main challenge is both for the cardiologist and for the patient, recognizing those prognostic signs that say this is an individual who is moving into the last phase of their disease. There's so much experience with successful management of exacerbations … that it's hard for both the patient and the doctor to say, ‘Wait a minute. The pattern is changing. There's (sic) more exacerbations … It's more difficult to get this person back from the edge.’ … (Palliative care physician)

Providers commonly mentioned the insistence on life‐prolonging treatments as a barrier to palliative care referral. One palliative care physician thought,

…that [cardiologists] are not only procedure driven but intervention driven … they have a hard time seeing an endpoint … in the same way that oncologists have a difficult time really seeing when their treatments just aren't working anymore.

“Why”: Perceptions of Palliative Care in HF

All providers endorsed palliative care in HF and believed that palliative care providers are experts regarding: symptom management; care coordination; and facilitating difficult discussions about prognosis, and advance care planning. Many appreciated its focus on quality of life:

… [T]o have a voice from the palliative care … team where we don't forget to focus on quality of life as much as survival would be … ideal for the patient population that we see. (Cardiologist)

Providers also discussed how sociocultural attitudes regarding death influenced provider referral, but often alluded to hospice when discussing palliative care. One primary care physician described, “a cultural bias against adopting palliative care unless you ‘know you're going to die.’”

Providers commonly contrasted HF and cancer. Unlike the cure‐oriented goal of oncology, providers believed that HF, as a progressive, incurable disease, poses challenges to integrating palliative care into standard HF management: “…[A]ll medical therapy for HF is really to relieve their symptoms. And so, in a sense, to me, it all feels like palliative care.” (Primary care physician)

“Who”: Inter‐provider Relationships and Responsibilities

To improve familiarity and acceptance, providers thought that palliative care must demonstrate and market its benefit to patients and providers. Trust and rapport were identified as key facilitators to palliative care referral, especially because palliative care knowledge is limited. Palliative care providers discussed how networking and peer education have resulted in greater and earlier referrals, by “winning over” previously skeptical colleagues:

…I think a lot of people really don't know what we do. I did a consult not too long ago. I showed up. The doctor looked up from the desk and he said ‘My patient doesn't need a morphine drip’ and I said, ‘I'm not here to start one.’ I said, ‘I do a whole lot more than start morphine drips, thank God.’ So I actually, in a good‐natured way, really try to do a little education with folks, and I think they really appreciate it. That same cardiologist has sent me several more consults since then … I think once he realized that we're not the ‘grim reaper service’ and that we're really about ‘what does the patient want,’ they sort of lay down their baggage. (Palliative care physician)

“Where”: Origin of Referral

Nearly all providers felt that primary care or cardiology providers should initiate conversations about palliative care due to their preexisting relationships with patients. However, palliative care providers feared that such conversations are inhibited by providers' discomfort with discussing palliation.

…I think it's perfectly fine for the primary treating cardiologist to begin that conversation … to say, ‘We need to start talking about your HF being in its latest stages. We need to think about what our options are for how to give you the best quality of life under these circumstances.’ But it's also perfectly fine for them to duck that conversation and say, ‘I want to pass the baton. I want the palliative care team to really help with that more difficult communication.’… (Palliative care physician)

“How”: Strategies to Increase Palliative Care Referral

A major barrier to palliative care referral was lack of knowledge within the healthcare community; overcoming this barrier requires intervention directed at providers during graduate or postgraduate training:

…[E]ducating HF physicians on the value and availability and the utilization of palliative care services is key. I don't think we get a good job of learning about that during our medical school or residency or fellowship training and if you don't train us at that point, you can't expect us to understand or know how to use them at this point …. [M]any of us physicians struggle with even bringing up the palliative care concept with patients because we're just not skilled necessarily at doing it. (Cardiologist)

All providers expressed the need to develop “palliative care basics” (eg, symptom identification/management in advanced illness, communication skills regarding goals of care), albeit for different reasons. Some cardiology providers desired to gain confidence in difficult communication, whereas palliative care providers often spoke of workforce constraints:

…There are still only 3,000 board‐certified palliative medicine physicians in the U.S. … [T]heir practices are predominantly hospital based. So from a practical standpoint, I think that has a couple of implications. One is the dominant model in the next several years would be to promote early inpatient consultation … maybe through identifying mutually agreed‐upon triggers for referrals with a cardiology service. And then I think the second element is to ramp up the level of palliative care expertise that cardiologists…have to exercise in their own practice so that it's not purely dependent on consultative services… (Palliative care physician)

Finally, providers discussed various practical strategies to encourage palliative care referral. For example:

…[Palliative care referral] relies on me asking for it when it probably should be more automated. It's like if someone has a big tumor on a CT scan, it's pretty quick how they get into an oncologist or get in for a biopsy but if it's got a really clear indicator for worsening trajectory, they don't automatically get [palliative care]…” (Primary care nurse)

Discussion

This is the first US study to explore barriers to palliative care referral for advanced HF patients among providers frequently caring for these patients. Despite the majority of cardiology and primary care providers practicing near specialist palliative care services, we found limited knowledge related to: what nonhospice palliative care is (especially differences from hospice); what it offers patients, families, and providers; when it is indicated; and, how to access it.

One barrier is confusion about the term “palliative care” itself. All cardiology and primary care providers reported familiarity with nonhospice palliative care; however, phrases such as “comfort care” or “just the basics” implied their equating nonhospice and hospice palliative care. Consistent with previous studies,44–45 nonpalliative care providers often reported criteria associated with the Medicare Hospice Benefit (ie, ≤6 months expected survival, suspending life‐prolonging treatments) as those for nonhospice palliative care. Notably, because providers almost unanimously used triggers to initiate palliative care, using inappropriate triggers (eg, active dying) may result in late referrals (if any). Prior work suggests that oncologists are more comfortable and are more likely to refer patients to a service called “supportive care” as opposed to “palliative care.”45 Similarly, in a 2×2 trial comparing the 2 names, patients with cancer had more favorable impressions of the term “supportive care.”46 The implications of the name “palliative care” have yet to be elucidated in the cardiogy population. Nevertheless, we must not lose sight of the fact that perception is paramount, particularly in sensitive contexts, such as serious illness. Our finding offers an important seed for future research.

Providers from all specialties interviewed frequently reported the unpredictability of HF as a barrier to palliative care referral, as seen elsewhere.31,33–34 Unlike the current hospice framework, nonhospice palliative care may present a more flexible alternative for addressing the needs of patients with diseases with volatile trajectories.47 Crisp demarcations between curative and palliative modalities reflect an unnecessary dichotomy that defers focusing on quality of life improvement until disease futility has been established (ie, hospice).23 Confusion regarding nonhospice palliative care and hospice was evident from both explicit statements and implicit comments. For example, the prognostic difficulty of HF and the insistence on life‐prolonging treatments were frequently discussed as barriers; however, they are actually only barriers to hospice referral, not to nonhospice palliative care.

All nonpalliative care providers interviewed explicitly expressed interest in exploring how to collaborate with palliative care. Prior qualitative research with physicians31–32,34 and nurses,33 in the United Kingdom and Australia suggests a mixture of professional, organizational, and cognitive factors impeding palliative care referral for HF patients, including concerns that patients might be “stolen” by palliative care providers.31 We did not identify such sentiments among our participants. Nevertheless, nonpalliative care providers reported being unsure of how and when to integrate specialist palliative care into standard HF management, the overarching reason cited for low referral.

Indeed, our research provides supporting evidence that collaboration between palliative and cardiology providers is suboptimal, despite mutual agreement of the likely benefit to patients that could result from palliative care. As such, clinical education must be improved to expose all learners to palliative care topics.48 Such training should strive to: correct misconceptions about palliative care and hospice (ie, that hospice is a specific subset of palliative care, largely defined by policy); teach providers how to identify palliative needs in their patients; how to provide primary palliative care themselves when appropriate; how to determine when specialist palliative care referral or consultation is indicated; and, how to effectively work with palliative care specialists. Consistent with previous work,23,49 nonpalliative care providers in our study were interested in learning more about palliative care from palliative care experts themselves. In the same vein, a palliative care physician said, “We must reach out and give [cardiology and primary care providers] the language [of palliative care].” Additionally, identifying and supporting “internal champions” within primary care or cardiology to serve as interdisciplinary liaisons with palliative care may be another mechanism by which to enhance meaningful collaboration between specialties. Nevertheless, palliative care specialists may serve as valuable resources to correct misconceptions regarding palliative care and hospice among medical professionals, patients, and caregivers.

Our findings support that the role of specialist palliative care has yet to be articulated for HF patients.32,50 Several steps pave the way to a clearer understanding of how specialist palliative care can be integrated into HF care. First, it is critical to determine whether palliative care improves HF patient outcomes in a randomized, controlled trial (as has been demonstrated in lung cancer8); these studies are underway, although preliminary studies offer signals that palliative care indeed holds promise in reducing HF‐related suffering.15–16 Second, research should define the optimal model for palliative care to maximize benefit while being flexible enough to accomodate patients with unpredictable trajectories (eg, HF). It is unlikely that the contemporary model of palliative care in oncology (ie, referral at the point of diagnosis) will seamlessly translate to HF. Needs‐based, as opposed to diagnosis‐based, referral may be a better approach to leveraging palliative care resources. If so, future research will need to identify clinically relevant, patient‐centered referral triggers specific to HF (eg, transition to Stage C HF). The increasing prevalence of patients with life‐limiting illnesses warrants exploring strategies to expand palliative care coverage, such as outpatient and community‐based palliative care programs.51–54

Limitations

This study has several limitations worth noting. First, generalizability may be limited because providers come from a single state and many practice in large, academic medical centers with palliative care programs.55 Our sample is likely more familiar with palliative care than most providers. Second, although we used sound methodological techniques that maximize analytic rigor and trustworthiness, others may have ultimately identified different themes. Third, whereas some may find our sample of 18 providers too small to provide generalizations to all cardiology, primary care, and palliative care providers, we caution that such conclusions are inappropriate given our qualitative study design. Furthermore, qualitative theory fundamentally discourages insistence upon sample size requirements and broad‐based generalizable inference. Nevertheless, Guest and colleagues suggest that thematic saturation generally occurs within the first 12 interviews, with basic themes emerging after 6 interviews; we conducted 18.56 Our work naturally sets the stage for survey research to confirm our findings on a national level.

Conclusions

Our research suggests that deficits in providers' knowledge and comfort in discussing palliative care for a difficult‐to‐predict disease present major barriers to referring patients with advanced HF for palliative care. This issue is of high relevance due to the recent ACC/AHA guidelines which emphasize the potential benefit of integrating palliative care in HF management18; our work provides a glimpse at impediments that pave the road to eventual operationalization of the guidelines. Indeed, our research highlights the need for increasing awareness of palliative care among healthcare providers, correcting misconceptions that it is only appropriate for the terminally ill. Future work should seek to develop provider‐ and patient‐centered interventions to reduce actionable barriers to palliative care uptake in HF.

Sources of Funding

This research was supported by a National Research Service Award Pre‐doctoral Traineeship from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, sponsored by the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Grant No. T32‐HS‐000032‐19. Dr Kavalieratos is currently supported by a National Research Service Award Post‐doctoral Traineeship from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, sponsored by the Division of General Internal Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh, Grant No. T32‐HS‐017587‐05.......

Disclosures

.Dr Abernethy has research funding from the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Cancer Institute, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Biovex, DARA, Helsinn, MiCo, Dendreon and Pfizer; these funds are all distributed to Duke University Medical Center to support research including salary support for Dr Abernethy. In the last 2 years she has had nominal consulting agreements with or received honoraria from (<$10 000 annually) Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Pfizer. Further consulting with Bristol Meyers Squibb is pending in 2013, for role as co‐Chair of a Scientific Advisory Committee. Dr Abernethy has a paid leadership role with American Academy of Hospice & Palliative Medicine (President). She has corporate leadership responsibility in Advoset (an education company that has a contract with Novartis) and Orange Leaf Associates LLC (an IT development company). Dr Biddle receives industry funding from Bristol Myers Squibb to oversee a fellowship program. Dr Carey receives funding from NIH, AHRQ, and the Patient‐Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). Dr Weinberger receives research funding from NIH, AHRQ, and the Department of Veterans Affairs. All other authors have no disclosures.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to our participants for sharing their time and experiences. Additionally, we thank Sarah Birken, PhD, for her thoughtful and constructive comments during the planning and interpretation of this study.

References

- 1.Walke LM, Byers AL, Tinetti ME, Dubin JA, McCorkle R, Fried TR. Range and severity of symptoms over time among older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2007; 167:2503-2508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bekelman DB, Havranek EP, Becker DM, Kutner JS, Peterson PN, Wittstein IS, Gottlieb SH, Yamashita TE, Fairclough DL, Dy SM. Symptoms, depression, and quality of life in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2007; 13:643-648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bekelman DB, Rumsfeld JS, Havranek EP, Yamashita TE, Hutt E, Gottlieb SH, Dy SM, Kutner JS. Symptom burden, depression, and spiritual well‐being: a comparison of heart failure and advanced cancer patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2009; 24:592-598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kavalieratos D, Kamal AH, Abernethy AP, Biddle AK, Carey TS, Dev S, Reeve BB, Weinberger M. Comparing unmet needs of community‐based palliative care patients with heart failure and cancer. J Palliat Med [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodlin SJ. Palliative care in congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009; 54:386-396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morrison RS, Meier DE. Palliative care. N Engl J Med. 2004; 350:2582-2590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morrison RS, Dietrich J, Ladwig S, Quill TE, Sacco J, Tangeman J, Meier DE. Palliative care consultation teams cut hospital costs for Medicaid beneficiaries. Health Aff. 2011; 30:454-463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, Dahlin CM, Blinderman CD, Jacobsen J, Pirl WF, Billings JA, Lynch TJ. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010; 363:733-742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, Balan S, Brokaw FC, Seville J, Hull JG, Li Z, Tosteson TD, Byock IR, Ahles TA. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the project enable II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009; 302:741-749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rabow M, Dibble S, Pantilat S, McPhee S. The comprehensive care team: a controlled trial of outpatient palliative medicine consultation. Arch Intern Med. 2004; 164:83-91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elsayem A, Swint K, Fisch MJ, Palmer JL, Reddy S, Walker P, Zhukovsky D, Knight P, Bruera E. Palliative care inpatient service in a comprehensive cancer center: clinical and financial outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2004; 22:2008-2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang B, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, Nilsson ME, Maciejewski ML, Earle CC, Block SD, Maciejewski PK, Prigerson HG. Health care costs in the last week of life: associations with end‐of‐life conversations. Arch Intern Med. 2009; 169:480-488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abernethy AP, Currow DC, Fazekas BS, Luszcz MA, Wheeler JL, Kuchibhatla M. Specialized palliative care services are associated with improved short‐ and long‐term caregiver outcomes. Support Care Cancer. 2008; 16:585-597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enguidanos S, Cherin D, Brumley R. Home‐based palliative care study: site of death, and costs of medical care for patients with congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cancer. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2005; 1:37-56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evangelista LS, Lombardo D, Malik S, Ballard‐Hernandez J, Motie M, Liao S. Examining the effects of an outpatient palliative care consultation on symptom burden, depression, and quality of life in patients with symptomatic heart failure. J Card Fail. 2012; 18:894-899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwarz ER, Baraghoush A, Morrissey RP, Shah AB, Shinde AM, Phan A, Bharadwaj P. Pilot study of palliative care consultation in patients with advanced heart failure referred for cardiac transplantation. J Palliat Med. 2012; 15:12-15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Unroe KT, Greiner MA, Hernandez AF, Whellan DJ, Kaul P, Schulman KA, Peterson ED, Curtis LH. Resource use in the last 6 months of life among Medicare beneficiaries with heart failure, 2000–2007. Arch Intern Med. 2011; 171:196-203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJV, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WHW, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL. 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013; 128:e240-e327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodlin S, Hauptman P, Arnold R, Grady K, Hershberger RE, Kutner JS, Masoudi F, Spertus J, Dracup K, Cleary JF, Medak R, Crispell K, Piña I, Stuart B, Whitney C, Rector T, Teno J, Renlund D. Consensus statement: palliative and supportive care in advanced heart failure. J Cardiac Fail. 2004; 10:200-209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodlin SJ. Palliative care for end‐stage heart failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2005; 2:155-160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adler ED, Goldfinger JZ, Kalman J, Park ME, Meier DE. Palliative care in the treatment of advanced heart failure. Circulation. 2009; 120:2597-2606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hupcey JE, Penrod J, Fogg J. Heart failure and palliative care: implications in practice. J Palliat Med. 2009; 12:531-536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ward C. The need for palliative care in the management of heart failure. BMJ. 2002; 87:294-298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hauptman PJ, Havranek EP. Integrating palliative care into heart failure care. Arch Intern Med. 2005; 165:374-378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buck HG, Zambroski CH. Upstreaming palliative care for patients with heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2012; 27:147-153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steinhauser KE, Arnold RM, Olsen MK, Lindquist J, Hays J, Wood LL, Burton AM, Tulsky JA. Comparing three life‐limiting diseases: does diagnosis matter or is sick, sick? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011; 42:331-341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Solano J, Gomes B, Higginson I. A comparison of symptom prevalence in far advanced cancer, aids, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and renal disease. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006; 31:58-69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Leary N, Murphy NF, O'Loughlin C, Tiernan E, McDonald K. A comparative study of the palliative care needs of heart failure and cancer patients. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009; 11:406-412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.NHPCO Facts and Figures: Hospice Care in America. Alexandria, VA: National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization; http://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/.../Statistics.../2013_Facts_Figures.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matlock DD, Peterson PN, Sirovich BE, Wennberg DE, Gallagher PM, Lucas FL. Regional variations in palliative care: do cardiologists follow guidelines? J Palliat Med. 2010; 13:1315-1319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanratty B, Hibbert D, Mair F, May C, Ward C, Capewell S, Litva A, Corcoran G. Doctors' perceptions of palliative care for heart failure: focus group study. BMJ. 2002; 325:581-585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanratty B, Hibbert D, Mair F, May C, Ward C, Corcoran G, Capewell S, Litva A. Doctors' understanding of palliative care. Palliat Med. 2006; 20:493-497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wotton K, Borbasi S, Redden M. When all else has failed: nurses' perception of factors influencing palliative care for patients with end‐stage heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2005; 20:18-25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Green E, Gardiner C, Gott M, Ingleton C. Exploring the extent of communication surrounding transitions to palliative care in heart failure: the perspectives of health care professionals. J Palliat Care. 2011; 27:107-116 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 2001Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shenton AK. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Educ Inform. 2004; 22:63-76 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hughes R, Huby M. The application of vignettes in social and nursing research. J Adv Nurs. 2002; 37:382-386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.King N. In: Symon G, Cassell C. (eds.). Template analysis. Qualitative Methods and Analysis in Organizational Research. 2004London, UK: Sage; 256-270 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 1994Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. 1985Beverly Hills, CA: Sage [Google Scholar]

- 41.Creswell JW, Miller DL. Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theor Pract. 2000; 39:124-130 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ahern KJ. Ten tips for reflexive bracketing. Qual Health Res. 1999; 9:407-411 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2008Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rodriguez KL, Barnato AE, Arnold RM. Perceptions and utilization of palliative care services in acute care hospitals. J Palliat Med. 2007; 10:99-110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fadul N, Elsayem A, Palmer JL, del Fabbro E, Swint K, Li Z, Poulter V, Bruera E. Supportive versus palliative care: what's in a name? Cancer. 2009; 115:2013-2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maciasz RM, Arnold RM, Chu E, Park SY, White DB, Vater LB, Schenker Y. Does it matter what you call it? A randomized trial of language used to describe palliative care services. Support Care Cancer. 2013; 21:3411-3419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fox E, Landrum‐McNiff K, Zhong Z, Dawson NV, Wu AW, Lynn J. Evaluation of prognostic criteria for determining hospice eligibility in patients with advanced lung, heart, or liver disease. Support investigators. Study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments. JAMA. 1999; 282:1638-1645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care—creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med. 2013; 368:1173-1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Selman L, Harding R, Beynon T, Hodson F, Coady E, Hazeldine C, Walton M, Gibbs L, Higginson IJ. Improving end‐of‐life care for patients with chronic heart failure: “Let's hope it'll get better, when i know in my heart of hearts it won't”. Heart. 2007; 93:963-967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brännström M, Forssell A, Pettersson B. Physicians' experiences of palliative care for heart failure patients. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011; 10:64-69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meier DE, Beresford L. Outpatient clinics are a new frontier for palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2008; 11:823-828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kamal AH, Currow DC, Ritchie CS, Bull J, Abernethy AP. Community‐based palliative care: the natural evolution for palliative care delivery in the U.S. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013; 46:254-264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kamal AH, Bull J, Kavalieratos D, Taylor DH, Jr, Downey W, Abernethy AP. Palliative care needs of patients with cancer living in the community. J Oncol Pract. 2011; 7:382-388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bekelman DB, Nowels CT, Allen LA, Shakar S, Kutner JS, Matlock DD. Outpatient palliative care for chronic heart failure: a case series. J Palliat Med. 2011; 14:815-821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Center to Advance Palliative Care, National Palliative Care Research Center America's care of serious illness: a state‐by‐state report card on access to palliative care in our nation's hospitals. 2011; Available at http://reportcard.capc.org/pdf/state-by-state-report-card.pdf? Accessed December 19, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough?: an experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006; 18:59-82 [Google Scholar]