Recent estimates released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicate that 34% of the US population is obese, with the prevalence projected to increase to 42% by 2030 if government and non-governmental stakeholders do not take action.1 Media attention surrounding these estimates highlighted the population-based approaches proposed by various stakeholders.2 The Institute of Medicine (IOM) released a report suggesting interventions to stem the obesity epidemic in the US that could comprise a comprehensive national obesity prevention strategy.3 Decision makers at the federal, state, and local levels face the task of selecting from these and other guidelines to address obesity and other public health issues. As a product of this work, they often develop a public health strategy, defined in this context as a set of policies or programs aimed at changing chronic disease risk factors and disease outcomes.

There is no single bullet solution for the leading global risk factors for disease and disability such as obesity, tobacco, and HIV/AIDS; they require multipronged comprehensive approaches. Those tasked with defining a national or state-level public health strategy face numerous recommended programs and policy instruments for each risk factor or disease area, and can select from already prioritized lists of interventions to reduce non-communicable diseases, some based on the cost-effectiveness of available options.4–6 In addition, priority setting tools, such as the one proposed by Magnusson (2011), as well as those discussed in a recent IOM workshop, are available for decision makers to use in selecting legal and regulatory approaches to address the burden of chronic disease.7,8

An intervention's inclusion in a strategy document is not a guarantee that the health department or other responsible agency will implement the strategy in its entirety if they face barriers, such as inadequate funding or pressure from interest groups. In general, the evaluation of comprehensive strategies has focused on a set of interventions contained within the strategy with little emphasis on the processes used by decision-makers to formulate, staff, and fund the final strategy for a given jurisdiction. Further, the literature has not explored the extent to which these processes, such as using a priority-setting tool, influence strategy implementation and its impact on health outcomes. The extent to which the aspects of the strategy development process, such as the degree of stakeholder involvement or the availability of resources, influence the strategy as it appears on paper, and also the extent to which responsible implementing agencies carry out the strategy as originally envisioned are not known. When faced with a menu of evidence-based interventions for inclusion in a strategy – how, why, and with what support are the interventions selected and implemented?

A conceptual framework for examining the strategy development process

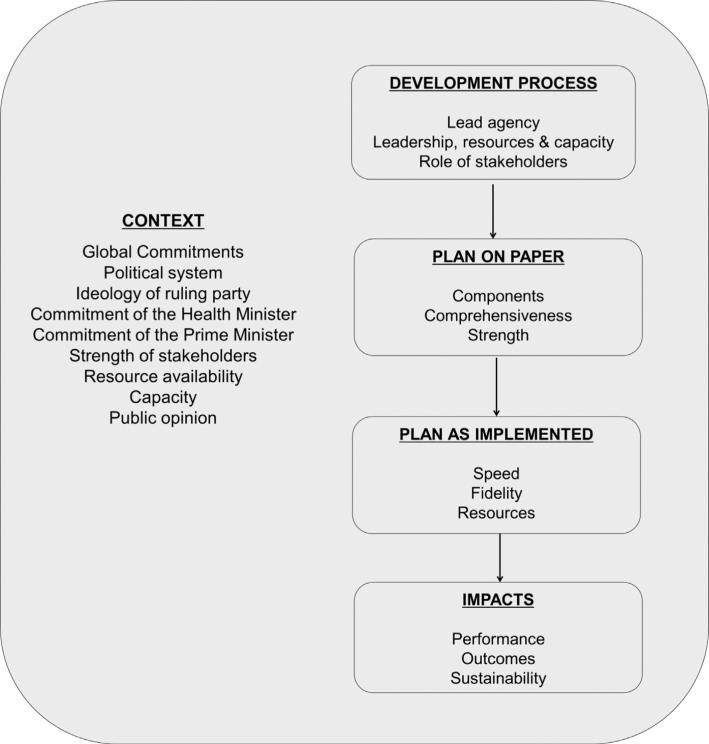

While several studies have explored the uptake of research evidence in policy-making, to the authors’ knowledge no empirical research has evaluated the factors influencing the decision-making process among those tasked with defining a comprehensive public health strategy.9 In developing a framework for areas of further study and understanding of these processes, the author's drew from the disciplinary and theoretical literature in the following areas: health policy and systems research;10 coalition building theory and models;11 management and organizational strategic decision making;12 and organizational learning.13 A conceptual framework has been proposed for exploring how policy makers develop and implement a comprehensive public health strategy (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A conceptual framework for examining the strategic development process.

The conceptual framework for studying strategy development and implementation outlines contextual factors, including stakeholders that may influence the development, implementation, and ultimate impacts of the strategy. In consideration of contextual factors, for example leadership commitment and global disease commitments such as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the development process often involves a leading agency that may facilitate the role of other stakeholders in the process.14 In 2011, the World Health Organization recommended intersectoral action in developing policies that promote and support health, providing a series of recommended steps for achieving effective policy outcomes.14 The influence of contextual factors on the development process would result in a plan on paper consisting of components of varying comprehensiveness and strength. Subsequently, the implementation speed and fidelity of the strategy outlined on paper may depend in part on the resources allocated. Lastly, the impact of the strategy may depend on the implementing agency's performance and its ability to sustain the strategy over the length of time needed to influence health outcomes.

The value in evaluating the process: understanding key components of success

There is still much to learn about which development and implementation configurations perform best in which contexts. For example, prospective research is needed on the process used to define the components of a strategy and how these approaches influence the extent to which the strategy is implemented. In addition, of interest is the evaluation of the role of the stakeholders involved and the mix of funds allocated for the programmatic activities that make up the strategy. A better understanding of these aspects of the process could be useful if linked to population-level health outcomes assessed in national and state-level surveys.

The proposed conceptual model can guide future empirical work and act as a starting point for further discussion regarding the need for practice-based evidence to examine the development and implementation of comprehensive public health strategies.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewer for the helpful comments in strengthening this communication.

Funding

ED and JEC received support from the Bloomberg Initiative to Reduce Tobacco Use, as part of a grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies to the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. ED also receives support for her doctoral training from the T32 NCI CA009314.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier's archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/authorsrights

Competing interests

None declared.

Ethical approval

None sought.

REFERENCES

- 1.Finkelstein EA, Khavjou OA, Thompson H, Trogdon JG, Pan L, Sherry B, Dietz W. Obesity and severe obesity forecasts through 2030. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012;42(6):563–70. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nation's obesity problem demands sweeping changes, panel says. Los Angeles Times; [28 June 2012]. Available at: http://www.latimes.com/ health/boostershots/la-heb-fight-obesity-20120508,0,2071987.story; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine . Accelerating progress in obesity prevention: solving the weight of the nation. The National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.: 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization . WHO framework convention on tobacco control. World Health Organization Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chisholm D, Baltussen R, Evans D, Ginsberg G, Lauer J, Lim S, Ortegon M, Salomon J, Stanciole A, Edejer Tan-Torres T. What are the priorities for prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases and injuries in sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia? British Medical Journal. 2012;344:e586. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Horton R, Adams C, Alleyne G, Asaria P, Baugh V, Bekedam H, Billo N, Casswell S, Cecchini M, Colagiuri R, Colagiuri S, Collins T, Ebrahim S, Engelgau M, Galea G, Gaziano T, Geneau R, Haines A, Hospedales J, Jha P, Keeling A, Leeder S, Lincoln P, McKee M, Mackay J, Magnusson R, Moodie R, Mwatsama M, Nishtar S, Norrving B, Patterson D, Piot P, Ralston J, Rani M, Reddy KS, Sassi F, Sheron N, Stuckler D, Suh I, Torode J, Varghese C, Watt J. Lancet NCD Action Group; NCD Alliance. Priority actions for the non-communicable disease crisis. Lancet. 2011;377:1438–47. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60393-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institute of Medicine . Country-level decision-making for control of chronic diseases. Workshop summary. The National Academies Press; Washington D.C.: 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magnusson R. Using a legal and regulatory framework to identify and evaluate priorities for cancer prevention. Public Health. 2011;125:854–75. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brownson RC, Jones E. Bridging the gap: translating research into policy and practice. Preventive Medicine. 2009;49(4):313–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilson L, editor. Health policy and systems research: a methodology primer. World Health Organization, Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research; Geneva, Switzerland: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kegler MC, Swan DW. Advancing coalition theory: the effect of coalition factors on community capacity mediated by member engagement. Health Education Research. 2011:11e3. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dean JW, Sharfman MP. Does decision matter? A study of strategic decision-making effectiveness. Academy of Management. 1996;39(2):368–96. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weaver L, Cousins JB. Unpacking the participatory process. Journal of MultiDisciplinary Evaluation. 2002;1:19–40. [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO . First global ministerial conference on healthy lifestyles and noncommunicable disease control. Moscow: Apr 28–29, 2011. Discussion paper. Intersectoral action on health: a path for policy-makers to implement effective and sustainable intersectoral action on health. http://www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncds_policy_makers_to_implement_ intersectoral_action.pdf. [Google Scholar]