Abstract

Importance

Combining pharmacotherapies for tobacco dependence treatment may increase smoking abstinence.

Objective

Determine efficacy and safety of combination therapy with varenicline and sustained-release bupropion compared to varenicline monotherapy in cigarette smokers.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled multicenter clinical trial with a 12-week treatment period and 52-week follow-up conducted between October 2009 and April 2013 at three midwestern clinical research sites. Five hundred six adult (≥ 18 years) cigarette smokers were randomized and 315 (62%) completed the study.

Intervention

Twelve weeks of: (1) varenicline/bupropion SR (combination therapy); or (2) varenicline/placebo (varenicline monotherapy).

Main Outcome

Primary outcome was the prolonged (no smoking from 2 weeks after the target quit date) and 7-day point-prevalence (no smoking past 7 days) abstinence rates at week 12. Secondary outcomes were prolonged and point-prevalence smoking abstinence rates at weeks 26 and 52. Outcomes were biochemically-confirmed.

Results

At 12 weeks, 53% of the combination therapy group achieved prolonged and 56.2% achieved 7-day point-prevalence smoking abstinence compared to 43.2% and 48.6% in varenicline monotherapy (odds ratio [OR] 1.49, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.05–2.12; P = .028 and OR 1.36, 95% CI, 0.95–1.93; P = .090, respectively). At 26 weeks, 36.6% of the combination therapy group achieved prolonged and 38.2% achieved 7-day point-prevalence smoking abstinence compared to 27.6% and 31.9% in varenicline monotherapy (OR 1.52, 95% CI, 1.04–2.22; P = .031 and OR 1.32, 95% CI, 0.91–1.91; P = .14, respectively). At 52 weeks, 30.9% of the combination therapy group achieved prolonged and 36.6% achieved 7-day point-prevalence smoking abstinence compared to 24.5% and 29.2% in varenicline monotherapy (OR 1.39, 95% CI, 0.93–2.07; P = .106 and OR 1.40, 95% CI, 0.96–2.05; P = .077, respectively). Participants receiving combination therapy reported more anxiety (7.2% vs 3.1%, P = .044) and depressive symptoms (3.6% vs 0.8%; P = .034).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among cigarette smokers, combined use of varenicline and bupropion, compared with varenicline alone, increased prolonged abstinence but not 7-day point prevalence at 12 and 26 weeks; neither outcome was significantly different at 52 weeks. Further research is required to determine the role of combination treatment in smoking cessation.

INTRODUCTION

Smoking accounts for 62% of deaths among female smokers and 60% of deaths among male smokers.1 Innovative pharmacotherapeutic approaches to tobacco dependence treatment need investigation to reduce smoking-related death and disability.

Bupropion SR (sustained-release) and varenicline are non-nicotine pharmacotherapies indicated for tobacco dependence treatment. Bupropion SR may mediate effects through noradrenergic and dopaminergic systems2 with a competitive inhibitory effect on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors.3 Varenicline is a partial agonist that binds with high affinity and selectivity at α4β2 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors.4,5 Opportunities exist for additive or synergistic therapeutic effects from combination therapy with these two medications.

Combination pharmacotherapy for treating tobacco dependence may increase smoking abstinence compared to monotherapy. A combination of bupropion SR and the nicotine patch is more effective than nicotine patch therapy alone,6 suggesting that an additive benefit is achieved by combining therapies. In an open-label pilot study evaluating combination therapy with varenicline and bupropion SR, the combination was well tolerated with smoking abstinence rates exceeding those observed in prior trials with either drug as monotherapy.7 If proven to be more effective than single-drug therapy, this therapeutic approach may have important clinical implications for tobacco dependence treatment. Exploration of combination therapy with existing drugs may provide the best opportunity to advance treatment in the absence of new pharmacotherapies for tobacco dependence on the horizon.

To investigate the efficacy of combination pharmacotherapy with varenicline and bupropion SR for smoking cessation compared to varenicline monotherapy, we conducted a multicenter, randomized, phase III clinical trial.

METHODS

Study Design

A randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial was conducted at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN; a Mayo Clinic Health System site in La Crosse, WI; and the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, MN, between October 2009 and April 2013. The study consisted of a 12-week treatment period with follow-up through week 52. The Institutional Review Boards of Mayo Clinic and the University of Minnesota approved all study procedures. The trial ended when recruitment was achieved and follow-up was completed.

Screening and Eligibility Criteria

Participants were eligible to participate if they were ≥ 18 years of age, smoked ≥ 10 cigarettes per day (cpd) for at least 6 months, motivated to become smoking abstinent, completed written informed consent, and were in good health.

Potentially eligible participants were excluded if they were female and pregnant, lactating or likely to become pregnant and not willing to use contraception or had: (1) an unstable medical condition; (2) another household member in the study; (3) bupropion or varenicline allergies; (4) current use (previous 30 days) of tobacco dependence treatment and unable to discontinue use; (5) unstable angina, myocardial infarction, or coronary angioplasty (previous 3 months) or an untreated cardiac dysrhythmia; (6) a history of renal failure or renal dialysis; (7) a history of seizures; (8) as defined by the C-SSRS (Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale),8 current non-specific suicidal thoughts or lifetime history of a suicidal attempt (ie “potentially self-injurious act committed with at least some wish to die, as a result of act”); (9) a history of closed head trauma with > 30 minute loss of consciousness, amnesia, skull fracture, subdural hematoma, or brain contusion; (10) a history or psychosis, bipolar disorder, bulimia, or anorexia nervosa; (11) current moderate or severe depression determined by a score of ≥ 20 on the Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition (BDI-II)9; (12) active substance abuse other than nicotine; (13) current (previous 14 days) use of antipsychotics, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, or drugs with bupropion SR interactions; (14) recent antidepressant dose change (previous 3 months); (15) systolic blood pressure > 180 mmHg or diastolic > 100 mmHg; (16) current treatment with another tobacco dependence investigational drug (previous 30 days); or (17) current bupropion or varenicline use (previous 30 days).

Study Procedures

The study consisted of a telephone screen, 11 clinic visits, and 3 telephone calls. One follow-up telephone call occurred during the medication phase at the time of the target quit date (TQD) and 2 calls occurred after the medication phase. Two clinic visits occurred before the medication phase, 6 during the medication phase, and 3 after the medication phase.

We collected demographics, tobacco use history, and self-reported information on race/ethnicity according to National Institutes of Health guidelines and recommendations for federally-funded research.10 We assessed dependence with the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND).11 Scores on the FTND range from 0 to 10.

Depressive symptomatology was assessed using the BDI-II.9 The C-SSRS assessed for suicidal ideation or behaviors.8 Both assessments were completed at baseline and weeks 2, 4, 8, 14, 26, and 52.

A central pharmacy randomized study medication in a 1:1 ratio using a computer-generated randomization sequence with variable-sized blocks ranging from 2 to 8 stratified by study site. Study medication was labeled and dispensed according to participant identification ensuring that treatment assignment remained concealed to the participant, investigators, and all study personnel having participant contact. Following completion of informed consent, participants received randomly assigned medication at the baseline visit.

Brief (≤ 10 minutes) behavioral counseling12 was provided at clinic visits, and tobacco use status, vitals, exhaled air carbon monoxide (CO) measurements (measured in parts per million), and weight were obtained. Participants completed tobacco craving and nicotine withdrawal assessments using a daily diary containing the Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale, Revised (MNWS-R).13 The MNWS-R consisted of items assessing irritability, anxiety, tobacco craving, depressed mood, difficulty concentrating, hunger, impatience, insomnia, and restlessness. Items were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (not present) to 4 (severe) reporting symptoms during the previous day. Pill counts were conducted at clinic visits and through self-reports of missed doses.

Study Medication

Participants were randomized to: (1) varenicline + bupropion SR (combination therapy); or (2) varenicline + matching bupropion SR placebo (varenicline monotherapy). Medication was started the day after the baseline visit and TQD was the eighth day of therapy.

Varenicline is an oral medication we administered in an open-label fashion and dispensed in blister packs. Participants started with a recommended oral dosage of 0.5 mg once daily for 3 days, increasing to 0.5 mg twice daily for days 4 to 7, and then to the maintenance dose of 1 mg twice daily (total of 2 mg/day) for 11 weeks.

Bupropion SR or identical-appearing placebo tablets were dispensed in pill bottles. Bupropion SR was titrated 1 tablet (150 mg) by mouth once per day for days 1 to 3, then 1 tablet by mouth twice per day (total of 300 mg/day) for 12 weeks. Participants receiving placebo escalated dosing in the same fashion.

Study Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the biochemically-confirmed prolonged and 7-day point-prevalence smoking abstinence rates at week 12. Endpoints were selected using recommended outcomes for tobacco intervention studies.14 A CO level of ≤ 8 parts per million verified self-reported smoking abstinence.15 Point prevalence was defined as CO-confirmed self-reported no tobacco use in the previous 7 days. Participants who met criteria for CO-confirmed 7-day point-prevalence abstinence at week 12, 26, and 52 visits were defined as meeting criteria for prolonged abstinence if they submitted negative responses to both of the following questions: “Since 14 days after your target quit date, have you used any tobacco on each of 7 consecutive days?” and “Since 14 days after your target quit date, have you used any tobacco on at least one day in each of 2 consecutive weeks?” Secondary outcomes were prolonged and 7-day point-prevalence smoking abstinence rates at weeks 26 and 52, tobacco craving and nicotine withdrawal symptoms, and weight changes.

Statistics

All analyses were performed using intention-to-treat. Smoking abstinence endpoints at week 12 (end-of-treatment), 26 weeks, and 52 weeks were analyzed separately using logistic regression. For these analyses, smoking abstinence was the dependent variable, treatment group was the independent variable, and study site was a covariate. Participants with missing smoking status information were adjudicated as smoking. A sample size of 250 participants per group was determined to provide statistical power (two-tailed, alpha=.05) of > 80% to detect a difference between treatment groups for the primary endpoint of prolonged tobacco abstinence at end-of-treatment (week 12). Sample size was based on reported smoking abstinence rates in previous trials of varenicline16,17 and a minimum detectible odds ratio of 1.7 for the comparison of varenicline and bupropion SR versus varenicline and placebo. In addition, we conducted planned exploratory analyses to assess whether treatment effect was moderated by age, gender, baseline smoking rate, < 20 cigarettes per day (cpd) [lighter smokers] versus ≥ 20 cpd (heavier smokers), or level of nicotine dependence, an FTND score ≤ 5 indicating a low/moderate level of dependence and an FTND score of ≥ 6 indicating a high level of dependence. For each characteristic, logistic regression analyses were performed with treatment, study site, and characteristic included as explanatory variables along with the treatment-by-characteristic interaction effect. If a significant interaction effect was detected, supplemental analyses were performed to compare treatment outcomes within subgroups defined by the characteristic.

The MNWS-R was completed daily. Tobacco craving was analyzed separately. A baseline score was calculated using MNWS-R data completed prior to starting medication. Scores obtained for the first 16 days after the TQD were analyzed as change from baseline. Mixed linear models were used with the daily change score as the dependent variable and a lag-1 autoregressive covariance structure used to take into account the clustering of repeated measurements within participants. Models included effects for treatment group, study day, and the treatment-by-study day interaction. Analyses were performed using all days for each participant and also using only data collected prior to the first reported tobacco use following TQD.

Among participants meeting criteria for prolonged abstinence, weight change from baseline was compared between groups using the two-sample t test. Frequency of adverse events was compared between groups using the Fisher exact test. In all cases, two-tailed P values were reported with values ≤ .05 considered statistically significant. Adverse events were adjudicated by investigators. Analyses were conducted using SAS (version 9.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA).

RESULTS

Enrollment and Follow-Up

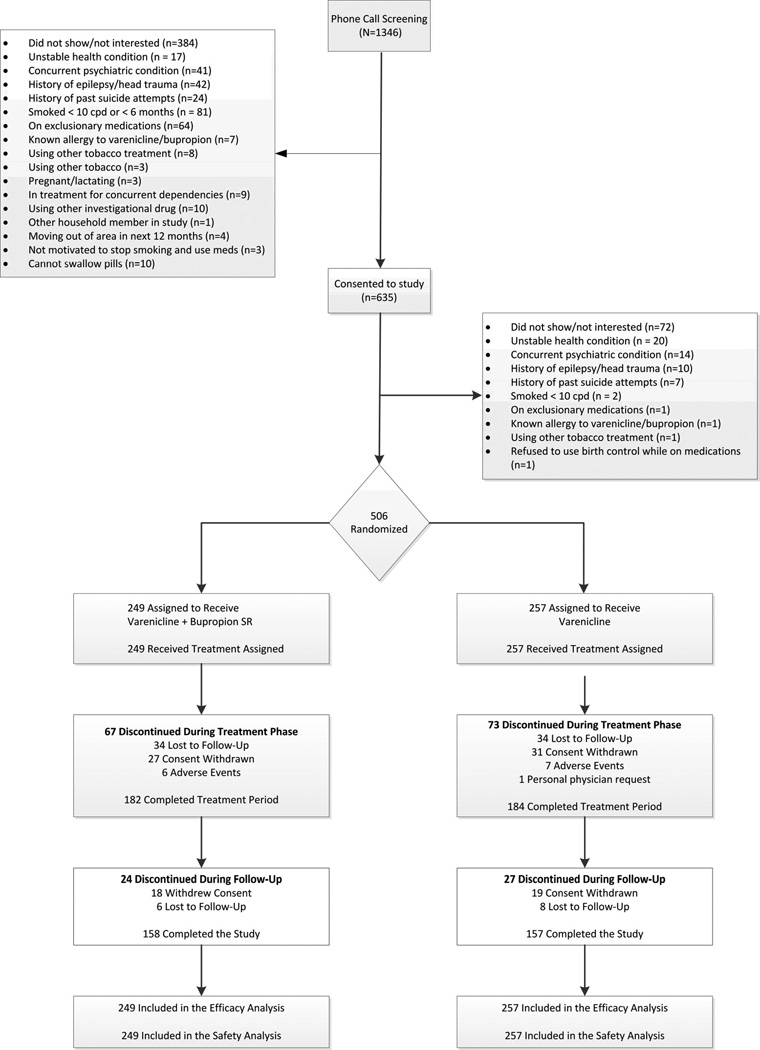

Of 635 potentially eligible participants consented, 506 (80%) were randomly assigned to varenicline and bupropion SR (n = 249) or varenicline and placebo (n = 257) (Figure). Overall study completion rates were 62% (315 participants), 63% (158 participants) in the varenicline and bupropion SR group (combination therapy) and 61% (157 participants) in the varenicline and placebo group (varenicline monotherapy). Patients assigned to study groups were similar at baseline (Table 1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Characteristic | Varenicline + Bupropion SR (n = 249) |

Varenicline + Placebo (n = 257) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean±SD | 42.2±12.2 | 41.9±12.7 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Female | 113 (45) | 126 (49) |

| Male | 136 (55) | 131 (51) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 234 (94) | 240 (93) |

| Other | 15 (6) | 17 (7) |

| Marital status, n (%)a | ||

| Never married | 73 (29) | 69 (27) |

| Separated/divorced | 53 (21) | 70 (27) |

| Married/living as married | 112 (45) | 111 (43) |

| Widowed/other | 10 (4) | 7 (3) |

| Highest level of education, n (%)a | ||

| High school graduate or less | 54 (22) | 67 (26) |

| Some college | 156 (63) | 137 (53) |

| College graduate or higher | 38 (15) | 53 (21) |

| Current smoking rate, cigarettes per day, mean±SD | 19.5±7.3 | 19.7±7.9 |

| < 20 cpd, n (%) | 102 (41) | 105 (41) |

| ≥ 20 cpd, n (%) | 147 (59) | 152 (59) |

| Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, mean±SDb | 5.2±2.0 | 5.3±2.0 |

| ≤ 5, n (%) | 127 (51) | 133 (52) |

| ≥ 6, n (%) | 120 (49) | 123 (48) |

| Duration of regular smoking, years, mean±SDa | 23.5±12.1 | 23.3±12.0 |

| Age when started smoking, years, mean±SDa | 17.6±3.9 | 17.5±4.1 |

| Ever made serious attempt to quit? n (%)a | ||

| No | 28 (11) | 19 (7) |

| Yes | 220 (89) | 238 (93) |

| Other tobacco users in household, n (%)a | ||

| No | 155 (63) | 162 (63) |

| Yes | 93 (37) | 95 (37) |

Abbreviations: SR, sustained-release, SD, standard deviation.

Missing data for 1 participant in the varenicline + bupropion SR group.

Scores range from 0 to 10 with higher scores indicating greater levels of nicotine dependence. An FTND score ≤ 5 indicates a low/moderate level of dependence and an FTND score of ≥ 6 indicates a high level of dependence. Missing data for 1 participant in the varenicline + placebo group and 2 participants in the varenicline + bupropion group.

Smoking Abstinence

Combination therapy was associated with significantly higher prolonged smoking abstinence rates at 12 and 26 weeks compared to varenicline monotherapy (Table 2). No significant differences were observed in prolonged smoking abstinence rates between the two groups at 52 weeks. No significant differences were observed between the two groups in the 7-day point-prevalence smoking abstinence rates at any time point.

Table 2.

Smoking Abstinence Outcomes

| 7-Day Point-Prevalence Smoking Abstinencea |

Prolonged Smoking Abstinencea |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nb | No. (%) | OR (95% CI) | P | No. (%) | OR (95% CI) | P | ||

| Overall | ||||||||

| Week 12 | ||||||||

| Varenicline+Bupropion SR | 249 | 140 (56.2) | 1.36 (0.95, 1.93) | .090 | 132 (53.0) | 1.49 (1.05, 2.12) | .028 | |

| Varenicline+Placebo | 257 | 125 (48.6) | 111 (43.2) | |||||

| Week 26 | ||||||||

| Varenicline+Bupropion SR | 249 | 95 (38.2) | 1.32 (0.91, 1.91) | .140 | 91 (36.6) | 1.52 (1.04, 2.22) | .031 | |

| Varenicline+Placebo | 257 | 82 (31.9) | 71 (27.6) | |||||

| Week 52 | ||||||||

| Varenicline+Bupropion SR | 249 | 91 (36.6) | 1.40 (0.96, 2.05) | .077 | 77 (30.9) | 1.39 (0.93, 2.07) | .106 | |

| Varenicline+Placebo | 257 | 75 (29.2) | 63 (24.5) | |||||

Abbreviations: cpd, cigarettes per day; SR, sustained-release.

Analyses were performed using logistic regression. In addition to treatment, the logistic regression analysis included a covariate for study site. Odds ratios > 1.0 indicate an increased likelihood of abstinence for varenicline + bupropion SR compared to varenicline + placebo.

179 participants (80 varenicline+bupropion SR, 99 varenicline+placebo) did not attend the week 12 visit. Of these, 101 (47 V+B, 54 V+P) reported smoking at the last visit they attended or had already reported failing prolonged abstinence criteria at a prior visit. 203 participants (93 V+B, 110 V+P) did not attend the week 26 visit of whom 118 (56 V+B, 62 V+P) reported smoking at the last visit they attended or had already failed prolonged abstinence criteria. 198 participants (93 V+B, 105 V+P) did not attend the week 52 visit of whom 121 (59 V+B, 62 V+P) reported smoking at the last visit they attended or had already failed prolonged abstinence criteria.

Nicotine Withdrawal and Tobacco Craving

Over 16 days following TQD, no significant differences in nicotine withdrawal or craving were observed between the two groups (mean treatment difference for nicotine withdrawal = +.04, 95% CI, −.02 to +.10; P = .253; mean treatment difference for craving = +.05, 95% CI, −.20 to +.30; P = .704). Similar results were obtained when the analysis included only data for days that participants reported abstinence (mean treatment difference for nicotine withdrawal = +.03, 95% CI,−.15 to +.21; P = .736; mean treatment difference for craving = +.06, 95% CI −.47 to +.59; P = .813).

Weight Gain

Among participants meeting criteria for prolonged smoking abstinence at end-of-treatment (week 12), the mean (95% CI) weight change from baseline to week 12 was significantly less in the combination therapy group compared to the varenicline monotherapy group (1.1 kg, 95% CI, 0.5–1.7 vs 2.5 kg, 95% CI, 2.0–3.0; P < .001). At 26 weeks, differences in weight gain were not observed and participants in the combination therapy group gained 3.4 kg, 95% CI, 2.5–4.3, and participants in the varenicline monotherapy group gained 3.8 kg, 95% CI, 2.9–4.8 (P = .479). At week 52, weight gain from baseline for the combination therapy group was 4.9 kg, 95% CI, 3.6–6.2, and for the monotherapy group it was 6.1 kg, 95% CI, 4.6–7.6 (P = .227).

Adverse Events

Adverse events occurring in ≥ 2% of one of the study groups are listed in Table 3. Anxiety was reported more commonly with combination therapy than with varenicline monotherapy (7.2% vs 3.1%; P = .044). Depressive symptoms were also reported more commonly with combination therapy than with varenicline monotherapy (3.6% vs 0.8%; P = .034).

Table 3.

Adverse Eventsa

| No. (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse Events | Varenicline + Bupropion SR (n = 249) |

Varenicline + Placebo (n = 257) |

P Valueb |

| Sleep disturbance | 100 (40.2) | 91 (35.4) | .273 |

| Nausea | 55 (22.1) | 54 (21.0) | .829 |

| Constipation | 26 (10.4) | 19 (7.4) | .275 |

| Headache | 21 (8.4) | 22 (8.6) | >.99 |

| Irritability | 21 (8.4) | 12 (4.7) | .105 |

| Abnormal dreams | 9 (3.6) | 19 (7.4) | .080 |

| Anxiety | 18 (7.2) | 8 (3.1) | .044 |

| Difficulty concentrating | 14 (5.6) | 10 (3.9) | .407 |

| Fatigue | 7 (2.8) | 17 (6.6) | .058 |

| Dizziness | 10 (4.0) | 10 (3.9) | >.99 |

| Mood disturbance | 13 (5.2) | 7 (2.7) | .175 |

| Dry mouth | 7 (2.8) | 9 (3.5) | .801 |

| Restlessness | 9 (3.6) | 5 (1.9) | .288 |

| Depressive symptoms | 9 (3.6) | 2 (0.8) | .034 |

| Flatulence | 1 (0.4) | 9 (3.5) | .020 |

| Dyspepsia | 5 (2.0) | 1 (0.4) | .117 |

Abbreviation: SR, sustained-release.

Adverse events considered to be possibly, probably, or definitely related to study medication and reported by ≥ 2% of either study group are summarized.

Fisher exact test.

During the medication phase or within 7 days of stopping medication, 4 serious adverse events (SAEs) occurred. In the combination therapy group, 1 participant sustained trauma during a motor vehicle collision after being on medication for two months. In varenicline monotherapy, the 3 events included food poisoning, diverticulitis, and breast cancer. No events were adjudicated to be related to study medication.

During follow-up and after medication discontinuation for at least 7 days, 8 SAEs were reported. Five occurred in combination therapy and included acute coronary syndrome, deep vein thrombosis complicated by acute coronary syndrome, prostate cancer, a new coronary artery disease diagnosis, and pneumothorax. In varenicline monotherapy, 3 SAEs occurred: 1 death due to complications from human immunodeficiency virus 6 months after study drug was discontinued, 1 attempted suicide 9 months after the medication was completed, and 1 lung cancer. No events were adjudicated to be related to study medication.

Additional Analyses

Preplanned exploratory analyses were performed to assess potential moderators of the effect of treatment on abstinence, and we observed no evidence that treatment effects differed according to age or gender (P > .25 for all age-by-treatment and gender-by-treatment interaction effects). However, we observed evidence that an effect of treatment on prolonged abstinence at 6 and 12 months was dependent on baseline smoking rate (interaction effect P = .040 and P = .011 at 6 months and 12 months, respectively) and level of nicotine dependence (interaction effect P = .026, P = .010). From supplemental subgroup analyses, no differences were observed between the two groups at any time point for either prolonged or point-prevalence smoking abstinence among lighter smokers (< 20 cpd). However, heavier smokers (≥ 20 cpd) receiving combination therapy were more likely to achieve prolonged smoking abstinence at weeks 12, 26, and 52 (Table 4) and 7-day point-prevalence smoking abstinence at weeks 26 and 52. For smokers with low/moderate levels of nicotine dependence (FTND ≤ 5), no difference in abstinence outcomes were detected at any time point. However, among participants with high levels of nicotine dependence (FTND ≥ 6), combination therapy was associated with an increased likelihood of prolonged abstinence at weeks 12, 26, and 52 and 7-day point-prevalence abstinence at week 52 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Smoking Abstinence Outcomes According to Baseline Smoking Rate and Level of Nicotine Dependence

| 7-Day Point-Prevalence Smoking Abstinencea |

Prolonged Smoking Abstinencea |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | No. (%) | OR (95% CI) | P | No. (%) | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Baseline Smoking Rate | |||||||

| Lighter Smokers (< 20 cpd) | |||||||

| Week 12 | |||||||

| Varenicline+Bupropion SR | 102 | 61 (59.8) | 1.20 (0.68, 2.11) | .532 | 58 (56.9) | 1.14 (0.65, 2.01) | .645 |

| Varenicline+Placebo | 105 | 59 (56.2) | 57 (54.3) | ||||

| Week 26 | |||||||

| Varenicline+Bupropion SR | 102 | 41 (40.2) | 0.94 (0.53, 1.66) | .817 | 40 (39.2) | 1.01 (0.57, 1.80) | .970 |

| Varenicline+Placebo | 105 | 45 (42.9) | 42 (40.0) | ||||

| Week 52 | |||||||

| Varenicline+Bupropion SR | 102 | 40 (39.2) | 1.10 (0.62, 1.96) | .740 | 30 (29.4) | 0.80 (0.43, 1.46) | .462 |

| Varenicline+Placebo | 105 | 40 (38.1) | 37 (35.2) | ||||

| Heavier Smokers (≥ 20 cpd) | |||||||

| Week 12 | |||||||

| Varenicline+Bupropion SR | 147 | 79 (53.7) | 1.52 (0.96, 2.40) | .075 | 74 (50.3) | 1.84 (1.16, 2.93) | .010 |

| Varenicline+Placebo | 152 | 66 (43.4) | 54 (35.5) | ||||

| Week 26 | |||||||

| Varenicline+Bupropion SR | 147 | 54 (36.7) | 1.79 (1.09, 2.96) | .022 | 51 (34.7) | 2.24 (1.32, 3.81) | .003 |

| Varenicline+Placebo | 152 | 37 (24.3) | 29 (19.1) | ||||

| Week 52 | |||||||

| Varenicline+Bupropion SR | 147 | 51 (34.7) | 1.76 (1.06, 2.93) | .030 | 47 (32.0) | 2.26 (1.31, 3.92) | .004 |

| Varenicline+Placebo | 152 | 35 (23.0) | 26 (17.1) | ||||

| Level of Nicotine Dependence | |||||||

| Low/moderate (FTND ≤ 5) | |||||||

| Week 12 | |||||||

| Varenicline+Bupropion SR | 127 | 77 (60.6) | 1.20 (0.72, 2.00) | .477 | 74 (58.3) | 1.31 (0.79, 2.18) | .296 |

| Varenicline+Placebo | 133 | 74 (55.6) | 68 (51.1) | ||||

| Week 26 | |||||||

| Varenicline+Bupropion SR | 127 | 55 (43.3) | 1.16 (0.69, 1.92) | .578 | 52 (40.9) | 1.10 (0.66, 1.84) | .708 |

| Varenicline+Placebo | 133 | 54 (40.6) | 52 (39.1) | ||||

| Week 52 | |||||||

| Varenicline+Bupropion SR | 127 | 49 (38.2) | 1.11 (0.66, 1.86) | .702 | 40 (31.5) | 0.92 (0.53, 1.57) | .751 |

| Varenicline+Placebo | 133 | 49 (36.8) | 45 (33.8) | ||||

| High (FTND ≥ 6) | |||||||

| Week 12 | |||||||

| Varenicline+Bupropion SR | 120 | 62 (51.7) | 1.55 (0.93, 2.58) | .091 | 57 (47.5) | 1.74 (1.04, 2.93) | .035 |

| Varenicline+Placebo | 123 | 50 (40.6) | 42 (34.2) | ||||

| Week 26 | |||||||

| Varenicline+Bupropion SR | 120 | 39 (32.5) | 1.74 (0.98, 3.09) | .060 | 38 (31.7) | 2.76 (1.47, 5.21) | .002 |

| Varenicline+Placebo | 123 | 27 (22.0) | 18 (14.6) | ||||

| Week 52 | |||||||

| Varenicline+Bupropion SR | 120 | 41 (34.2) | 2.04 (1.14, 3.66) | .016 | 36 (30.0) | 2.77 (1.44, 5.30) | .002 |

| Varenicline+Placebo | 25 (20.3) | 17 (13.8) | |||||

Abbreviations: cpd, cigarettes per day; SR, sustained-release.

Analyses were performed using logistic regression. In addition to treatment, the logistic regression analysis included a covariate for study site. Odds ratios > 1.0 indicate an increased likelihood of abstinence for varenicline + bupropion SR compared to varenicline + placebo.

DISCUSSION

Among cigarette smokers, the combined use of varenicline and bupropion, compared with varenicline alone, resulted in an increase in prolonged smoking abstinence but not 7-day point-prevalence smoking abstinence at 12 and 26 weeks. Neither outcome was significant at 52 weeks. Our observed rates of prolonged smoking abstinence with varenicline monotherapy were consistent with those of previous varenicline studies at all time points.16,17

We observed a greater attenuation of weight gain at 3 months in participants continuously abstinent from smoking with combination therapy compared to varenicline monotherapy. Meta-analyses have suggested that bupropion SR attenuates post-cessation weight gain more than varenicline at the end of treatment.18 In previous trials, mean weight gain with varenicline among smoking-abstinent participants from baseline to 12 weeks was 2.37 kg16 and 2.89 kg,17 and 2.12 kg16 and 1.88 kg17 for bupropion SR. Most weight gain after smoking cessation occurs in the first 3 months,19 and weight gain has been shown in some studies to lead to smoking relapse.20–23 Combination therapy could provide a clinical option for patients concerned about weight gain and for whom weight gain may undermine smoking cessation in the short term.

Anxiety and depressive symptoms were reported more commonly in combination therapy. In previous smoking cessation studies with varenicline and bupropion SR, no significant increases in anxiety were observed with either varenicline or bupropion SR compared to placebo.16,17 Bupropion SR is known to be associated with anxiety when used in the treatment of tobacco dependence.24 Tobacco withdrawal has also been associated with both anxiety and depressive symptoms.25 All patients being treated with pharmacotherapy for tobacco dependence should be monitored for changes in anxiety and mood, an approach consistent with standard clinical practice.

Our study has limited generalizability to the general population of smokers since we excluded patients with serious medical and psychiatric illnesses including those with active substance abuse. Our reported abstinence rates and treatment comparisons need to be interpreted with the knowledge that 38% of participants did not complete the study. This may lead to overestimation or underestimation of the true treatment effects. However, drop-out rate was comparable between the two groups and comparable to previous trials using varenicline for smoking cessation.16,17 We conducted additional data analyses using multiple imputation, but for tobacco cessation studies empirical evidence has suggested that subjects who drop out are likely to have relapsed to smoking.26 The analyses of the effect of treatment by smoking rate and nicotine dependence level were exploratory and hypothesis-generating.

We considered multiple imputation to handle missing data; however, this requires the assumption that missing outcomes are missing at random which empirical evidence suggests is not true for smoking cessation studies.26 However, the assumption that all drop-outs have resumed smoking could underestimate abstinence rates.

CONCLUSION

Among cigarette smokers, combined use of varenicline and bupropion, compared with varenicline alone, resulted in an increase in prolonged abstinence but not 7-day point prevalence at 12 and 26 weeks; neither outcome was significantly different at 52 weeks. Further research is required to determine the role of combination treatment in smoking cessation.

Acknowledgements

The clinical trial was supported by NIH grant CA 138417 (PI: JOE).

Medication (varenicline) was provided by Pfizer. JOE and JTH have served as investigators for clinical trials funded by Pfizer. RDH has received consulting fees from Pfizer and an unrestricted grant from Pfizer Medical Education Group. Neither the NIH nor Pfizer had a role in the conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication. JOE has received personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline and research support from Orexigen and JHP Pharmaceuticals outside of the current study.

DKH has received research support from NabiBiopharmaceuticals outside of the current study.

Footnotes

Trial Registration: Varenicline and Bupropion for Smoking Cessation (CHANBAN); NCT00935818; http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00935818.

ITC, DRS, and SSA have no conflicts of interests to report.

JOE had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jha P, Ramasundarahettige C, Landsman V, et al. 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(4):341–350. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1211128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ascher JA, Cole JO, Colin JN, et al. Bupropion: a review of its mechanism of antidepressant activity. J Clin Psychiatry. 1995;56(9):395–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Damaj MI, Carroll FI, Eaton JB, et al. Enantioselective effects of hydroxy metabolites of bupropion on behavior and on function of monoamine transporters and nicotinic receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66(3):675–682. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.001313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Obach RS, Reed-Hagen AE, Krueger SS, et al. Metabolism and disposition of varenicline, a selective alpha4beta2 acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, in vivo and in vitro. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34(1):121–130. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.006767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tapper AR, McKinney SL, Nashmi R, et al. Nicotine activation of alpha4* receptors: sufficient for reward, tolerance, and sensitization. Science. 2004;306(5698):1029–1032. doi: 10.1126/science.1099420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jorenby DE, Leischow SJ, Nides MA, et al. A controlled trial of sustained-release bupropion, a nicotine patch, or both for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(9):685–691. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903043400903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ebbert JO, Croghan IT, Sood A, Schroeder DR, Hays JT, Hurt RD. Varenicline and bupropion sustained-release combination therapy for smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(3):234–239. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Posner K. Suicidality issues in clinical trials: Columbia Suicide Adverse Event Identification in FDA Safety Analyses. [Accessed June 27, 2013];2007 http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/07/slides/2007-4306s1-01-CU-Posner.ppt.

- 9.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory Manual. Second ed. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institutes of Health. NIH Policy on Reporting Race and Ethnicity Data: Subjects in Clinical Research. [Accessed September 25, 2013];2001 http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOTOD-01-053.html.

- 11.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Croghan IT, Trautman JA, Winhusen T, et al. Tobacco dependence counseling in a randomized multisite clinical trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33(4):576–582. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes JR. Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale - Revised. [Accessed October 9, 2013];2007 http://www.uvm.edu/~hbpl/?Page=minnesota/default.html. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, Ossip-Klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GE. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5(1):13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benowitz NL, Ahijevych K, Hall S, et al. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4(2):149–159. doi: 10.1080/14622200210123581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzales D, Rennard SI, Nides M, et al. Varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296(1):47–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jorenby DE, Hays JT, Rigotti NA, et al. Efficacy of varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs placebo or sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296(1):56–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farley AC, Hajek P, Lycett D, Aveyard P. Interventions for preventing weight gain after smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;1:CD006219. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006219.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aubin HJ, Farley A, Lycett D, Lahmek P, Aveyard P. Weight gain in smokers after quitting cigarettes: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:e4439. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Copeland AL, Martin PD, Geiselman PJ, Rash CJ, Kendzor DE. Smoking cessation for weight-concerned women: group vs. individually tailored, dietary, and weight-control follow-up sessions. Addict Behav. 2006;31(1):115–127. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pomerleau C, Zucker A, Stewart A. Characterizing concerns about post-cessation weight gain: Results from a national survey of women smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001;3:51–60. doi: 10.1080/14622200020032105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyers A, Klesges RC, Winders S, Ward K, Peterson B, Eck L. Are weight concerns predictive of smoking cessation? A prospective analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65(3):448–452. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.3.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clark MM, Hurt RD, Croghan IT, et al. The prevalence of weight concerns in a smoking abstinence clinical trial. Addict Behav. 2006;31(7):1144–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hays JT, Ebbert JO. Adverse effects and tolerability of medications for the treatment of tobacco use and dependence. Drugs. 2010;70(18):2357–2372. doi: 10.2165/11538190-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hughes JR. Effects of abstinence from tobacco: etiology, animal models, epidemiology, and significance: a subjective review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(3):329–339. doi: 10.1080/14622200701188927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foulds J, Stapleton J, Hayward M, et al. Transdermal nicotine patches with low-intensity support to aid smoking cessation in outpatients in a general hospital. A placebocontrolled trial. Arch Fam Med. 1993;2(4):417–423. doi: 10.1001/archfami.2.4.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]