Abstract

In this article, we address how and why parent-child attachment is related to anxiety in children. Children who do not form secure attachments to caregivers risk developing anxiety or other internalizing problems. While meta-analyses yield different findings regarding which insecurely attached children are at greatest risk, our recent studies suggest that disorganized children may be most at risk. Insecure attachment itself may contribute to anxiety, but insecurely attached children also are more likely to have difficulties regulating emotions and interacting competently with peers, which may further contribute to anxiety. Clinical disorders occur primarily when insecure attachment combines with other risk factors. In this article, we present a model of factors related to developing anxiety.

Parent-child relationships influence children’s social and emotional development (Maccoby, 2007). An example is research on parent-child attachment: In the first year of life, all children form attachments to caregivers who provide them protection and care (Bowlby, 1982) and children organize their behavior to use a parent as a secure base (Ainsworth, 1989). The secure base phenomenon occurs when a child uses his or her parent as a safe haven during times of distress and as a secure base from which to explore the environment when not distressed. Although all children are expected to form attachments (except in cases of extreme deprivation), the quality (specifically, security) of attachments varies substantially. A child who is securely attached is able to use his or her parent as a safe haven and a secure base, and develops cognitive models of the self as loveable and of caregivers as responsive, sensitive, and available (Bowlby, 1973). Although attachments emerge in the first year of life, they are important for healthy development across the lifespan (Ainsworth, 1989), and parents continue to function as primary attachment figures for children at least through preadolescence (Seibert & Kerns, 2009) and possibly across the adolescent years.

A major tenet of attachment theory is the competence hypothesis, which posits that the formation of a secure attachment in childhood prepares a child for other social challenges (e.g., finding a place in the peer group) and places a child on a more positive developmental trajectory (Weinfield, Sroufe, Egeland, & Carlson, 2008). Several mechanisms may account for this effect (Contreras & Kerns, 2000; Sroufe, Egeland, & Carlson, 1999); for example, through daily interactions with sensitive caregivers, securely attached children may have more opportunities to learn competent social interaction and emotion regulation skills. In addition, securely attached children may develop more positive expectations about others and a greater sense of selfefficacy, which in turn facilitate their social relationships. Consistent with the competence hypothesis, children who are more securely attached form more positive relationships with peers, cooperate more with adults, and regulate their emotions more effectively (Kerns, 2008; Thompson, 2008; Weinfield et al., 2008).

More recently, researchers have asked how and why attachment contributes to the development of psychopathology. Bowlby (1982) originally focused on attachment because his clinical work identified parent-child relationships as influencing the development of troubled behavior in childhood; subsequently, scientists have sought to understand how insecure attachments may contribute to developing externalizing behaviors (e.g., aggression, delinquency) and internalizing behaviors (e.g., anxiety, depression). Our work focuses on whether parent-child attachment is a risk factor for developing anxiety and/or depression in childhood and adolescence, and addresses three interrelated questions, which we illustrate by discussing our work on attachment and anxiety: 1.) Is attachment related to anxiety and if so, is lack of secure attachment or specific forms of insecure attachment more strongly related to anxiety? 2.) What accounts for why attachment is related to anxiety—is it lack of a secure base per se that contributes to anxious feelings, or do other factors (e.g., child competencies) mediate or explain the link between attachment and anxiety? 3.) Is attachment related to anxiety when considering other known influences on anxiety such as parenting or temperament, and does it interact with other risk factors to magnify risk? The work we describe focuses on global measures of anxiety rather than specific forms of anxiety.

Is Parent-Child Attachment Related to Anxiety?

Bowlby (1973) suggested that children experience anxiety when they have doubts about the availability or accessibility of attachment figures, especially when they experience difficult or disturbing events. Conversely, access to a caregiver who provides a secure base and safe haven should mitigate anxious feelings. Over time, repeated experiences with attachment figures lead children to develop general expectations about the availability and accessibility of those attachment figures, which can lead to chronic anxiety if children come to believe that attachment figures are not consistently available, protective, and comforting.

Several reviews have addressed whether insecure attachment is related to anxiety or, more generally, internalizing disorders. Two meta-analyses of parent-child attachment and internalizing problems (Groh, Roisman, van Ijzendoorn,Bakersman-Kranenberg, & Fearon., 2012; Madigan, Atkinson, Laurin, & Benoit, 2013) included only studies that used observational measures to assess attachment in early childhood. One narrative review (Brumariu & Kerns, 2010a) examined evidence for associations of parent-child attachment with anxiety, depression, or internalizing problems in childhood or adolescence, and included studies that used a diverse range of attachment measures (i.e., behavioral observation, representational measures, and questionnaires). Another meta-analysis (Colonnesi et al., 2011) examined the association between attachment and anxiety in childhood and adolescence, including studies that assessed either parent-child or child-peer attachment, using any type of attachment measure. All four of these reviews concluded that insecure attachment (compared with secure attachment) is associated with higher levels of anxiety and/or internalizing problems.

In contrast, researchers disagree about whether specific forms of insecure attachment place children at greater risk for anxiety. Common to all insecurely attached children is the inability to use one’s parent as a secure base and safe haven, and negative beliefs about the availability and accessibility of caregivers, but insecurity is manifested in different ways (Cassidy, 1994; Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985). Children with avoidant attachments can be overly self-reliant and maintain emotional distance from a rejecting caregiver; children with ambivalent (or preoccupied) attachments are chronically unsure of the caregiver’s availability, which can lead them to be vigilant about remaining in close contact with caregivers; and children with disorganized attachments, who have experienced caregivers who are harsh, psychologically unavailable, or unpredictable, may either lack a coherent strategy for relating to the parent or take control of the relationship through role reversal (e.g., taking care of the parent).

Insecure ambivalent children may be most prone to experience anxiety because they are chronically worried about the availability of attachment figures (Carlson & Sroufe, 1995). Alternatively, some researchers (e.g., Brumariu & Kerns, 2010a; Moss, Rousseau, Parent, St. Laurent, & Saintogne, 1998; Moss, Smolla, Cyr, Dubois-Comtois, Mazzarello, & Berthiaume, 2006) suggest that disorganized children, who perceive themselves as helpless and vulnerable, and caregivers as frightening and unable to protect them, may be at greatest risk for developing internalizing problems, including anxiety. Finally, ambivalent, avoidant, and disorganized attachment may predispose children to develop different types of anxiety (Manassis, 2001). For example, ambivalent children would be most prone to experience separation anxiety, avoidant children would be most prone to social phobia, and disorganized children may be prone to school phobia.

The four reviews differ in their conclusions about which specific types of insecure attachment are associated with greater risk for anxiety or internalizing problems. One reported that only avoidant attachment was related to internalizing problems, most strongly to social withdrawal (Groh et al., 2012). One found that both avoidant and disorganized attachment were associated with internalizing problems, although the latter was not significant after controlling for publication bias (Madigan et al., 2013). One examined only one insecure pattern— ambivalence—and concluded that children with ambivalent attachments are more prone to experiencing anxiety (Colonnesi et al., 2011). In our narrative review (Brumariu & Kerns, 2010a)—which examined avoidance, ambivalence, and disorganization, as well as security—we noted that firm conclusions were difficult to draw, especially when considering the use of different attachment measures and different ages. Nevertheless, we suggest, disorganized attachment may be the insecure attachment pattern most consistently related to internalizing problems.

The reviews differed substantially in terms of the studies they considered. The Groh et al. (2012) and Madigan et al. (2013) meta-analyses included only studies that used observational measures of attachment (which are used with young children), and in these studies internalizing problems were usually assessed in early or middle childhood. Thus, these meta-analyses address the question of whether early attachment forecasts early childhood internalizing problems, and do not evaluate whether attachment is relevant for developing internalizing problems later. Depression and many types of anxiety occur more frequently in adolescence than earlier, so studies with younger children miss the period during which some internalizing problems occur.1 Colonnesi et al. (2011) included studies that assessed attachment across childhood and adolescence, and found that the association between attachment and anxiety was stronger in adolescence than in childhood and in studies that used questionnaires rather than other types of attachment measures. The limited pool of available studies that assessed specific insecure attachment patterns constrains all of the reviews, especially when looking at specific types of internalizing problems or specific age groups. For example, Groh et al. (2012) identified only two studies that examined disorganization and clinical depression, and even though they had a strong association, this finding was not interpreted due to the small sample size. Although Colonnesi et al. (2011) found that ambivalent attachment was related to child anxiety, they did not examine disorganized attachment in their analyses; in our review (Brumariu & Kerns, 2010a), although ambivalent attachment was related to anxiety in some studies, this was not the case for those studies that included children with disorganized attachments as a separate group.

To shed further light on the question of which insecure attachment pattern is most related to anxiety and to address gaps in the literature, we conducted a series of studies to examine how attachment is related to anxiety in preadolescence or adolescence (Brumariu, Kerns, & Siebert, 2012). We examined concurrent associations between a story stem measure of attachment and self-reports of anxiety symptoms in 10- to 12-year-olds. Children who were less secure or more disorganized were more anxious; in contrast, ambivalence and avoidance were not related to anxiety. In a different sample (Brumariu & Kerns, 2013), we used observational measures of attachment from the first three years to predict maternal reports of children’s anxiety symptoms at ages 10 to 12. Again, both security and disorganization were related to later anxiety, but ambivalence and avoidance were not. In a third study (Brumariu, Obsuth, & Lyons-Ruth, 2013) of older adolescents, disorganized attachment was assessed with both the Adult Attachment Interview and an observational measure of parent-child interaction, and anxiety disorders were assessed with a clinical interview. Adolescents with anxiety disorders had more disorganized representations and interaction patterns than adolescents without a clinical disorder. Thus, despite differences across the studies in how attachment and anxiety were assessed, all three showed that disorganized attachment was associated with greater anxiety. As more studies are done of insecure attachment and anxiety at older ages, we predict that disorganized children, who lack access to a secure base, will be most at risk for developing anxiety.

Why Is Attachment Related to Anxiety?

While insecurely attached children are apparently at risk for developing anxiety, the reason is less clear. Lack of a secure base may lead directly to feelings of anxiety (Bowlby, 1973). However, according to the competence hypothesis, children who are insecurely attached also are less socially and emotionally competent, which in turn may contribute to the development of anxiety. Thus, insecurely attached children may be anxious not only because they lack a secure base, but because they are prone to having other experiences (e.g., difficulties with peers) that contribute to anxiety.

We have speculated whether emotion regulation and peer competence partially explain associations between attachment and anxiety. We have focused on these two potential mechanisms because theoretical reasons suggest that each is related to attachment and anxiety. Emotion regulation is integral to attachment in that children use the attachment figure as a resource to regulate their own emotions (e.g., seeking comfort). Children also learn about emotions, emotion communication, and regulating emotion in the context of interactions with attachment figures (Cassidy, 1994; Contreras & Kerns, 2000). Securely attached children manage emotions better, even in the absence of the caregiver (e.g., Abraham & Kerns, in press; Kerns, Abraham, Schlegelmilch, & Morgan, 2007; Sroufe, Egeland, & Kreutzer, 1990). In addition, emotion regulation processes are related to anxiety. By definition, anxiety reflects difficulties managing emotional arousal and the intense experience of negative emotions. Anxious children regulate their emotions, but the processes involved in regulating emotion tend to be ineffective (Thompson, 2001). For example, anxious children have difficulty identifying their own emotions, are prone to negatively evaluate emotionally laden situations, and use less adaptive coping strategies (Brumariu et al., 2012; Southam-Gerow & Kendall, 2002).

We propose that processes of emotion regulation may help explain why insecurely attached children are more anxious (Brumariu & Kerns, 2010a; see Esbjorn, Bender, Reinholdt-Dunne, Munck, & Ollendick, 2012, for a similar perspective). In a cross-sectional study of 10- to 12-year-old children (Brumariu et al., 2012), children’s greater awareness of emotions helped explain why securely attached children are less anxious, and the tendency to catastrophize in upsetting situations helped explain why disorganized children are more anxious. Moreover, in two longitudinal studies (Bosquet & Egeland, 2006; Brumariu & Kerns, 2013), children who were securely attached early in life were less anxious in late childhood, in part because they managed their emotions better.

Relationships with peers also may contribute to insecurely attached children’s anxiety. Securely attached children are more cooperative, better liked by peers, and form more supportive friendships than insecurely attached children (Booth-LaForce & Kerns, 2009; Schneider, Atkinson, & Tardif, 2001). Peer relationships are also related to anxiety in that more anxious children perceives themselves to be less competent with peers, are more likely to be victimized by peers, and have more difficulties in friendships and romantic relationships (Brumariu et al., 2013; Kingery, Erdley, Marshall, Whitaker, & Reuter, 2010). Consistent with the idea that peer relationships play a role in explaining associations between attachment and anxiety, in two studies, children securely attached in the first three years were more competent with peers in middle childhood, which in turn accounted for why they experienced less anxiety in late childhood or adolescence (Bosquet & Egeland, 2006; Brumariu & Kerns, 2013).

Placing Attachment in a Broader Context

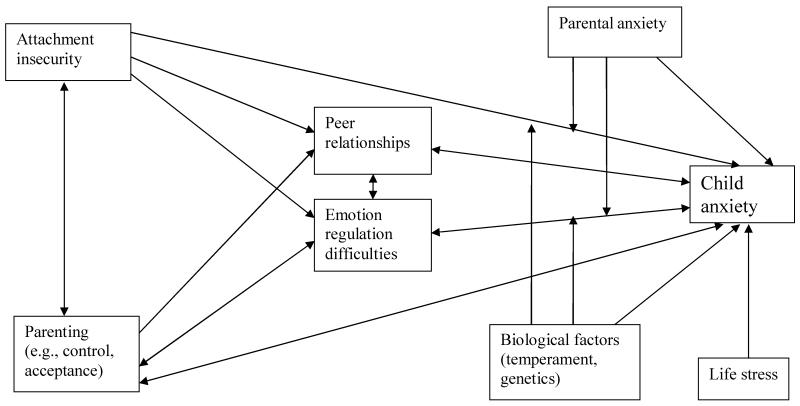

Failure to form a secure attachment to a caregiver in childhood places children at risk for developing anxiety. However, the magnitude of the association is modest and single risk factors, in isolation, rarely lead to the development of a clinical disorder. Consistent with a developmental psychopathology perspective (Cicchetti & Sroufe, 2000), multiple risk factors contribute to the development of anxiety (Brumariu & Kerns, 2010a; Kerns, Siener, & Brumariu, 2011). A number of potential pathways and moderating factors link family relationships, child characteristics, and child anxiety (see Figure 1, a simplified model that draws on an earlier conceptual model [Brumariu & Kerns, 2010a] and is an example of a broader model that considers the role of attachment in the development of anxiety). For example, as described previously and consistent with cascade models of the development of psychopathology (Masten & Cicchetti, 2010), insecure attachment may lead to anxiety or other internalizing problems in part because insecurely attached children have difficulties regulating emotions and getting along with peers, experiences that in turn further heighten children’s risk for developing anxiety.

Figure 1.

Simplified Conceptual Model of Factors Related to the Development of Anxiety

Anxiety also has been linked to several risk factors other than attachment, including temperament (e.g., behavioral inhibition, negative emotion), stressful life events, and parenting (e.g., acceptance, control). All of these factors are related to anxiety, independent of attachment (Brumariu & Kerns, 2010b; Brumariu & Kerns, 2013; Kerns et al., 2011). Thus, while attachment is an important part of understanding why some children develop anxiety, it is only part of the explanation. Risk factors such as temperament, specific genes, or maternal anxiety may accentuate or moderate the impact of attachment. For example, insecurely attached children had frequent symptoms of social phobia regardless of their levels of behavioral inhibition, whereas securely attached children had frequent symptoms of social phobia only if they were also inhibited (Brumariu & Kerns, 2010b). Finally, although parent-child relationships can influence later social competencies and anxiety, reciprocal effects exist across time, as shown in the figure. For example, as children become more anxious, they may have increasing difficulty regulating emotions and their parents may respond to their anxiety in ways that lead children to feel less secure (e.g., parents may be more rejecting or controlling).

Conclusions

Insecure parent-child attachment is one risk factor for the development of anxiety. Our recent studies also show that disorganized attachment is associated with anxiety. Attachment may be associated with anxiety, in part, because insecurely attached children are less likely to develop competent emotion regulation and social interaction skills, which in turn places them at risk for experiences that contribute to the development of anxiety. Researchers should further test factors that may explain why attachment and anxiety are related, as well as broader models of how different risk factors interact over time to explain why some children develop anxiety disorders.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Kent State University Research Council and NICHD (Early Child Care Study).

Footnotes

A reviewer asked why avoidant attachment was related to internalizing problems in two of the meta-analyses. Measures of internalizing symptoms in young children will capture only those symptoms seen at that age (e.g., social withdrawal but not depression). Avoidant attachment was related most strongly in Groh et al. (2012) to social withdrawal, which we speculate may reflect the fact that avoidantly attached children have difficulties in peer interactions at young ages.

Contributor Information

Kathryn A. Kerns, Department of Psychology Kent State University

Laura E. Brumariu, Derner Institute of Psychology Adelphi University

References

- Abraham MM, Kerns KA. Positive and negative emotions and coping as mediators of the link between mother-child attachment and peer relationships. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. In press. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS. Attachments beyond infancy. American Psychologist. 1989;44:709–716. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.4.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth-LaForce C, Kerns KA. Child-parent attachment relationships, peer relationships, and peer group functioning. In: Rubin KH, Bukowski W, Laursen B, editors. Handbook of Peer Interactions, Peer Relationships, and Peer Group Functioning. Guilford; New York, NY: 2009. pp. 490–507. [Google Scholar]

- Bosquet M, Egeland B. The development and maintenance of anxiety symptoms from infancy through adolescence in a longitudinal sample. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:517–550. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 2: Separation. Basic; New York, NY: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1: Attachment. 2nd ed. Basic; New York, NY: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Brumariu LE, Kerns KA. Parent-child attachment and internalizing symptomatology in childhood and adolescence: A review of empirical findings and future directions. Development and Psychopathology. 2010a;22:177–203. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumariu LE, Kerns KA. Mother-child attachment patterns and different types of anxiety symptoms: Is there specificity of relations? Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2010b;41:663–674. doi: 10.1007/s10578-010-0195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumariu LE, Kerns KA. Pathways to anxiety: Contributions of attachment history, temperament, peer competence, and ability to manage intense emotions. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2013;44:504–515. doi: 10.1007/s10578-012-0345-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumariu LE, Kerns KA, Seibert AC. Mother-child attachment, emotion regulation, and anxiety symptoms in middle childhood. Personal Relationships. 2012;19:569–585. [Google Scholar]

- Brumariu LE, Obsuth I, Lyons-Ruth K. Quality of attachment relationships and peer relationship dysfunction among late adolescents with and without anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2013;27:116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson EA, Sroufe LA. Contribution of attachment theory to developmental psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology, Vol. 1: Theory and methods. Wiley; Oxford, England: 1995. pp. 581–616. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J. Emotion regulation: Influences of attachment relationships. The development of emotion regulation: Biological and behavioral considerations. In: Fox NA, editor. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. Vol. 59. 1994. Serial No. 240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Sroufe A. The past as prologue to the future: The times, they’ve been a-changin’. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:255–264. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colonnesi C, Draijer EM, Stams GJJM, van der Bruggem CO, Bogels SM, Noom MJ. The relation between insecure attachment and child anxiety: A meta-analytic study. Journal of Child Clinical and Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40:630–645. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.581623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras JM, Kerns KA. Emotion regulation processes: Explaining links between parent-child attachment and peer relationships. In: Kerns KA, Contreras JM, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Family and peers: Linking two social worlds. Praeger; Westport, CT: 2000. pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Esbjorn BH, Bender PK, Reinholdt-Dunne ML, Munck LA, Ollendick TH. The development of anxiety disorders: The contributions of attachment and emotion regulation. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2012;15:129–143. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groh AM, Roisman GI, van Ijzendoorn MH, Bakersman-Kranenburg MJ, Fearon RP. The significance of insecure and disorganized attachment for children’s internalizing symptoms: A meta-analytic study. Child Development. 2012;83:591–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns KA. Attachment in middle childhood. In: Cassidy J, Shaver P, editors. Handbook of attachment. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2008. pp. 366–382. [Google Scholar]

- Kerns KA, Abraham MM, Schlegelmilch A, Morgan TA. Mother-child attachment in later middle childhood: Assessment approaches and associations with mood and emotion regulation. Attachment and Human Development. 2007;9:33–53. doi: 10.1080/14616730601151441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns KA, Siener S, Brumariu LE. Mother-child relationships, family context, and child characteristics as predictors of anxiety symptoms in middle childhood. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23:593–604. doi: 10.1017/S0954579411000228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingery JN, Erdley CA, Marshall KC, Whitaker KG, Reuter TR. Peer experiences of anxious and socially withdrawn youth: An integrative review of the developmental and clinical literature. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2010;13:91–128. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. Historical overview of socialization research and theory. In: Grusec JE, Hastings PD, editors. Handbook of socialization. Guilford; New York, NY: 2007. p. 1.p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Madigan S, Atkinson L, Laurin K, Benoit D. Attachment and internalizing behavior in childhood: A meta-analysis. Developmental Psychology. 2013;49:672–689. doi: 10.1037/a0028793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Kaplan N, Cassidy J. Security of infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. In: Bretherton I, Waters E, editors. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. Vol. 50. 1985. Serial No. 209. [Google Scholar]

- Manassis K. Child-parent relations: Attachment and anxiety disorders. In: Silverman WK, Treffers PDA, editors. Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: Research, assessment, and intervention. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2001. pp. 255–272. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Cicchetti D. Developmental cascades. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:491–495. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss E, Rousseau D, Parent S, St.-Laurent D, Saintonage J. Correlates of attachment at school age: Maternal reported stress, mother-child interaction, and behavior problems. Child Development. 1998;69:1390–1405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss E, Smolla N, Cyr C, Dubois-Comtois K, Mazzarello T, Berthiaume C. Attachment and behavior problems in middle childhood as reported by adult and child informants. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:425–444. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider BH, Atkinson L, Tardif C. Child-parent attachment and children’s peer relations: A quantitative review. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:86–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibert AC, Kerns KA. Attachment figures in middle childhood. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2009;33:347–355. [Google Scholar]

- Southam-Gerow MA, Kendall PC. Emotion regulation and understanding: Implications for child psychopathology and therapy. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22:189–222. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00087-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Egeland B, Carlson EA. One social world: The integrated development of parent-child and peer relationships. In: Collins WA, Laursen B, editors. Relationships as developmental contexts. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1999. pp. 241–261. [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Egeland B, Kreutzer T. The fate of early experience following developmental change: Longitudinal approaches to individual adaptation in childhood. Child Development. 1990;61:1363–1373. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA. Childhood anxiety disorders from the perspective of emotion regulation and attachment. In: Vasey MW, Dadds MR, editors. The developmental psychopathology of anxiety. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2001. pp. 160–182. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA. Early attachment and later development: Familiar questions, new answers. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment. 2nd ed. Guilford; New York, NY: 2008. pp. 348–365. [Google Scholar]

- Weinfield NS, Sroufe LA, Egeland B, Carlson E. Individual differences in infant-caregiver attachment: Conceptual and empirical aspects of security. In: Cassidy J, Shaver P, editors. Handbook of attachment. 2nd ed. Guilford; New York, NY: 2008. pp. 78–101. [Google Scholar]