To the editor:

Reduced access to healthcare and food in the United States is associated with poor health outcomes1-3 and facilitating access to providers, medications, and food has led to measured improvements in public health.4, 5 Food allergy is a common, chronic condition, affecting 4-8% of US children, and is increasing in prevalence for unclear reasons.6, 7 Whether patients with food allergy experience impaired access to healthcare and food is currently unknown. Minority populations share a significant burden of food allergy,7, 8 and the rate of increase in food allergy in Black children may be twice that in Caucasian children.7 We were interested in whether subjects with food allergy report reduced access to healthcare and food and how this is associated with race/ethnicity, as this may influence disease outcome.

We examined data from the 2011 and 2012 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), a household interview survey of the US population covering a range of health topics. In each household, an adult answered questions about a randomly chosen child in the household. We considered a child to have food allergy if the responding adult answered yes to the question “during the past 12 months, has the sample child had any kind of food or digestive allergy?” We used the adult's responses to questions regarding the child's access to healthcare and the family's access to food as measures of access to healthcare and food. Access to food was defined using the USDA's definition of “food security,” a measure of consistency of access to enough food for an active, healthy life. Please see the Online Repository at www.jacionline.org for additional information regarding the access measures, NHIS methodology and variable definitions. Statistical analyses were performed with STATA 12.0 software (StataCorp, College Station, Tex.). We used the chi square test to determine whether subjects with and without food allergy differed by demographic and access factors. We used logistic regression to determine the association between race/ethnicity and access, and adjusted for gender, age, family income and education, in a nested fashion. We incorporated survey weighting, sampling units, and strata in the primary chi square analysis, but because subjects were not equally distributed among the strata, only survey weights were incorporated in the chi square analysis stratified by race and in the logistic regression models.

Complete data were available for 26,021 children from the combined 2011-2012 dataset, of whom 1,351 (5.59%) reported food allergy. Of the food allergic children, 54.8% were White, 17.1% Black/African American, 17.7% Hispanic/Latino/Spanish, and 10.4% Other (Table E1). Food allergy in the sample child was more common in families with a higher education level and with a higher household income, in line with previously reported demographic trends.6, 9 The survey population was equally distributed between genders and among age groups.

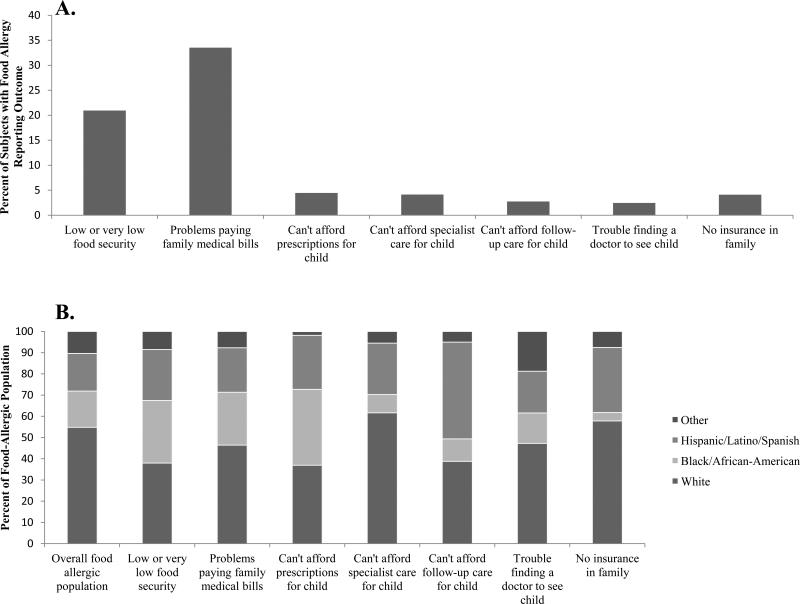

Among children with food allergy, 20.95% were determined to have low food security, 33.53% reported having problems paying family medical bills, 4.47% reported not being able to afford needed prescriptions, 4.14% reported not being able to afford needed specialist care, 2.76% reported not being able to afford needed follow-up care, 2.45% percent reported having trouble finding a doctor to see the child, and 4.11% reported having no family member with health insurance (Figure 1A and Table E1). With the exception of having family members without insurance, these values are all significantly higher than those for children without food allergy (p≤0.05), and similar trends were observed when stratifying by race/ethnicity (Table E2).

Figure 1.

A: Percentage of subjects with food allergy reporting impaired food security or reduced access to healthcare metric. B: Distribution of subjects with food allergy reporting impaired food security or reduced access to healthcare metric by race/ethnicity.

Compared to White children with food allergy, after adjusting for age and gender, Black children with food allergy were significantly more likely to have low food security (OR 3.31, 95% CI 2.17-5.06), to have problems paying family medical bills (OR 2.28, 95% CI 1.55-3.35), and to be unable to afford needed prescriptions (OR 3.44, 95% CI 1.68-7.02; Table 1 and Figure 1B). Hispanic children with food allergy were more likely to have low food security (OR 2.44, 95% CI 1.61-3.70), to have problems paying family medical bills (OR 1.56, 95% CI 1.08-2.23), and were more likely to be unable to afford needed prescriptions (OR 2.38, 95% CI 1.13-5.03) and follow-up care (OR 3.74, 95% CI 1.70-8.24). Many of these associations were attenuated after further adjusting for income and parental education. However, even after incorporating these variables, Black respondents with food allergy were significantly more likely to have low food security (OR 2.15, 95% CI 1.30-3.53), to have problems paying family medical bills (1.68, 95% CI 1.09-2.59), and to have trouble affording prescriptions for the child (OR 2.40, 95% CI 1.14-5.05) and Hispanic respondents with food allergy were significantly more likely to have trouble affording follow-up care (OR 3.02, 95% CI 1.34-6.81; Table 1) compared to White respondents with food allergy. There were no significant race/ethnicity differences in ability to afford specialist care or difficulty finding a doctor to see the child. Black respondents with food allergy were more likely in all models to have any family member with health insurance. We next compared children with food allergy to those with other chronic medical conditions and found that children with food allergy have similar or greater difficulty with access to care and food as children with other chronic medical conditions, with similar racial/ethnic disparities as in the previous analysis (Table E3).

Table 1.

Racial/ethnic disparities in likelihood of poor food security and reduced healthcare access among children with food allergy

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Model 1: adjusted for child's age, gender | Model 2: Model 1, adjusted for parental education | Model 3: Model 1, adjusted for income group | Full Model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low or very low food security | |||||

| White | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] |

| Black/African-American | 3.39 (2.21-5.19) | 3.31 (2.17-5.06) | 2.63 (1.64-4.22) | 2.20 (1.36-3.56) | 2.15 (1.30-3.53) |

| Hispanic/Latino/Spanish | 2.45 (1.61-3.71) | 2.44 (1.61-3.70) | 1.63 (1.04-2.57) | 1.67 (1.07-2.62) | 1.47 (0.92-2.34) |

| Other | 1.16 (0.62-2.14) | 1.17 (0.63-2.18) | 1.18 (0.63-2.23) | 1.20 (0.64-1.73) | 1.19 (0.62-2.27) |

| Problems paying family medical bills | |||||

| White | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] |

| Black/African-American | 2.30 (1.57-3.38) | 2.28 (1.55-3.35) | 1.95 (1.29-2.93) | 1.69 (1.10-2.60) | 1.68 (1.09-2.59) |

| Hispanic/Latino/Spanish | 1.57 (1.09-2.25) | 1.56 (1.08-2.23) | 1.21 (0.82-1.80) | 1.23 (0.83-1.83) | 1.18 (0.78-1.79) |

| Other | 0.76 (0.48-1.20) | 0.76 (0.48-1.21) | 0.75 (0.47-1.21) | 0.81 (0.49-1.35) | 0.81 (0.49-1.35) |

| Can't afford prescriptions for child | |||||

| White | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] |

| Black/African-American | 3.34 (1.65-6.74) | 3.44 (1.68-7.02) | 3.13 (1.50-6.50) | 2.37 (1.13-4.98) | 2.40 (1.14-5.05) |

| Hispanic/Latino/Spanish | 2.29 (1.07-4.89) | 2.38 (1.13-5.03) | 2.02 (0.88-4.61) | 1.76 (0.80-3.92) | 1.78 (0.77-4.10) |

| Other | 0.23 (0.05-1.15) | 0.23 (0.05-1.16) | 0.24 (0.05-1.16) | 0.23 (0.05-1.17) | 0.23 (0.05-1.18) |

| Can't afford specialist care for child | |||||

| White | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] |

| Black/African-American | 0.44 (0.15-1.26) | 0.43 (0.15-1.25) | 0.39 (0.14-1.11) | 0.35 (0.12-0.96) | 0.34 (0.13-0.95) |

| Hispanic/Latino/Spanish | 1.22 (0.51-2.91) | 1.25 (0.52-3.00) | 1.08 (0.46-2.57) | 1.08 (0.48-2.42) | 1.06 (0.47-2.42) |

| Other | 0.44 (0.13-1.52) | 0.45 (0.13-1.56) | 0.45 (0.13-1.56) | 0.45 (0.13-1.60) | 0.45 (0.13-1.60) |

| Can't afford follow-up care for child | |||||

| White | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] |

| Black/African-American | 0.85 (0.30-2.40) | 0.85 (0.30-2.40) | 0.76 (0.26-2.17) | 0.59 (0.20-1.71) | 0.59 (0.20-1.72) |

| Hispanic/Latino/Spanish | 3.65 (1.67-8.01) | 3.74 (1.70-8.24) | 3.18 (1.41-7.17) | 2.92 (1.30-6.56) | 3.02 (1.34-6.81) |

| Other | 0.63 (0.11-3.68) | 0.64 (0.11-3.71) | 0.64 (0.11-3.69) | 0.65 (0.11-3.83) | 0.65 (0.11-3.84) |

| Trouble finding a doctor to see child | |||||

| White | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] |

| Black/African-American | 1.00 (0.27-3.70) | 0.97 (0.26-3.56) | 0.80 (0.20-3.28) | 0.85 (0.20-3.56) | 0.82 (0.19-3.51) |

| Hispanic/Latino/Spanish | 1.30 (0.46-3.64) | 1.29 (0.47-3.57) | 1.00 (0.35-2.89) | 1.19 (0.42-3.35) | 1.02 (0.35-2.97) |

| Other | 2.06 (0.68-6.24) | 2.12 (0.71-6.36) | 2.12 (0.70-6.36) | 2.17 (0.71-6.60) | 2.16 (0.72-6.54) |

| No insurance in family | |||||

| White | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] | 1.00 [REF] |

| Black/African-American | 0.21 (0.05-0.92) | 0.23 (0.05-1.00) | 0.17 (0.04-0.77) | 0.15 (0.03-0.65) | 0.14 (0.03-0.63) |

| Hispanic/Latino/Spanish | 1.66 (0.82-3.38) | 1.74 (0.85-3.57) | 1.16 (0.54-2.48) | 1.24 (0.56-2.73) | 1.10 (0.51-2.39) |

| Other | 0.65 (0.19-2.20) | 0.63 (0.19-3.57) | 0.65 (0.19-2.19) | 0.62 (0.18-2.13) | 0.63 (0.18-2.16) |

Values in boldface are statistically significant.

In this large national survey, we examined access to healthcare and food among subjects with food allergy, a chronic disease rising in prevalence. We found that compared to subjects without food allergy, subjects with food allergy are significantly more likely to report difficulty with access to care and food. Furthermore, parents of non-White children with food allergy were significantly more likely to report difficulty affording medical care and medications and low food security compared to parents of White children with food allergy. Not surprisingly, many of these associations were attenuated when we included parental income and education in the analysis. However, we were surprised that even after adjusting for income and education, Black respondents with food allergy were significantly more likely to report low food security and trouble affording prescriptions, and Hispanic respondents with food allergy were significantly more likely to report trouble affording follow-up care compared to White respondents. While it may be unsurprising that families of children with food allergies report more trouble accessing healthcare than families of children without food allergy, we did find that families of children with food allergy report at least as much, if not more, trouble accessing healthcare as families of children with other chronic diseases (Table E3 and supplementary information). Our results suggest there may be a barrier to accessing healthcare and food in children with food allergy, particularly among non-White children. Poor access to healthcare and food may increase morbidity, especially among minority children, by imposing poor nutrition and delayed treatment for allergic reactions.

Associations drawn from cross-sectional studies are only a first step in understanding the association between food allergy and access to care. Our study is limited by the use of parental report of food or digestive allergy within the last year. This may over- or under-estimate food allergy prevalence, and further validation studies are needed to perform population based studies of food allergy. However, parent-reported food allergy prevalence in our sample falls within the range of previously reported estimates, and has been used in many epidemiologic studies of food allergy.6, 7, 9 Our cross-sectional study is also limited by the possibility of reverse causation in that decreased access to healthcare and food may increase the likelihood of self-report of food allergy. However, we incorporated potentially important socio-economic confounders such as income and education into our analyses, making this effect less likely. We were also limited by our inability to incorporate the full sampling design into our analysis due to the distribution of subjects within strata. Our estimates are therefore not necessarily nationally representative. However, this study is notable as it is the first to examine access to care among patients with food allergy and includes over 1,000 subjects with parent-reported food allergy, nearly 50% of whom are non-White.

In summary, we have demonstrated that subjects with food allergy report difficulty with access to medical care and food, and that there are significant disparities in access associated with race/ethnicity. We were surprised that many of these disparities persisted after adjusting for income and education, which may be explained by socio-cultural factors and needs further investigation. Given the rising burden of food allergy, particularly among children of Black/African-American ethnicity, our results may have significant public health implications. Further study is necessary to determine if impaired access to care in patients with food allergy is associated with increased morbidity, and if improvements in access can improve disease outcome, as has been shown for other allergic disease such as asthma.4

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: This work was supported in part by grants from The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology and FARE and a KL2 Medical Research Investigator Training award (an appointed KL2 award) from Harvard Catalyst | The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award 1KL2 TR001100-01 to JHS. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jones R, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in asthma-related emergency department visits and hospitalizations among children with wheeze in Buffalo. 10. Vol. 45. J Asthma; New York: 2008. pp. 916–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cook JT, et al. Food insecurity is associated with adverse health outcomes among human infants and toddlers. J Nutr. 2004;134(6):1432–8. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.6.##. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Price JH, et al. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Chronic Diseases of Youths and Access to Health Care in the United States. Biomed Res Int. 2013:787616. doi: 10.1155/2013/787616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox P, et al. Improving asthma-related health outcomes among low-income, multiethnic, school-aged children: results of a demonstration project that combined continuous quality improvement and community health worker strategies. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):e902–11. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kowaleski-Jones L, Duncan GJ. Effects of participation in the WIC program on birthweight: evidence from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(5):799–804. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta RS, et al. The prevalence, severity, and distribution of childhood food allergy in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):e9–17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keet CA, Savage JH, Seopaul S, Peng RD, Wood RA, Matsui EC. Temporal Trends and Recent Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Pediatric Food Allergy in the US. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2013.12.007. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor-Black S, Wang J. The prevalence and characteristics of food allergy in urban minority children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;109(6):431–7. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGowan EC, Keet CA. Prevalence of self-reported food allergy in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2007-2010. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(5):1216–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.