Abstract

Background

Surgical site infection (SSI) after spinal surgery is a devastating complication. Various methods of skin closure are used in spinal surgery, but the optimal skin-closure method remains unclear. A recent report recommended against the use of metal staples for skin closure in orthopedic surgery. 2-Octyl-cyanoacrylate (Dermabond; Ethicon, NJ, USA) has been widely applied for wound closure in various surgeries. In this cohort study, we assessed the rate of SSI in spinal surgery using metal staples and 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate for wound closure.

Methods

This study enrolled 609 consecutive patients undergoing spinal surgery in our hospital. From April 2007 to March 2010 surgical wounds were closed with metal staples (group 1, n = 294). From April 2010 to February 2012 skin closure was performed using 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate (group 2, n = 315). We assessed the rate of SSI using these two different methods of wound closure. Prospective study of the time and cost evaluation of wound closure was performed between two groups.

Results

Patients in the 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate group had more risk factors for SSI than those in the metal-staple group. Nonetheless, eight patients in the metal-staple group compared with none in the 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate group acquired SSIs (p < 0.01). The closure of the wound in length of 10 cm with 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate could save 28 s and $13.5.

Conclusions

This study reveals that in spinal surgery, wound closure using 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate was associated with a lower rate of SSI than wound closure with staples. Moreover, the use of 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate has a more time saving effect and cost-effectiveness than the use of staples in wound closure of 10 cm in length.

Keywords: Surgical site infection, Spinal surgery, Wound closure, 2-Octyl-cyanoacrylate, Staples

Introduction

Surgical site infection (SSI) after spinal surgery is a devastating complication. SSI results in long-term intravenous antibiotics uses, re-operation and prolonged hospitalization and increases morbidity and mortality [1]. The total cost of care for a patient with SSI is more than four times that of an uncomplicated case [2]. The rate of SSI in spinal surgery has been reported from 0 to 32 % [3–10]. There are various methods of skin closure in spinal surgery, but the optimal skin-closure method remains unclear [11, 12]. A recent report recommended against the use of metal staples for skin closure in orthopedic surgery [13].

In 1949, a group of adhesives called ‘cyanoacrylates’ were synthesized via the reaction of cyanoacetate with formaldehyde, with variations in the alkyl group [14]. Octyl-cyanoacrylates, which are the longest-chain derivatives, represent the least toxic of the cyanoacrylates [15]. 2-Octyl-cyanoacrylate (Dermabond® topical skin adhesive; Ethicon, NJ, USA) has been widely used for wound closure in traumatic laceration [16, 17], facial surgery [18], craniotomy and craniectomy [19], pediatric neurosurgery [20, 21], corneal surgery [22], orthopedic surgery [23] and mammoplasty [24]. The use of 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate for wound closure in spinal surgery has been reported to provide sufficient wound closure with a low risk of SSI [25, 26]. In the current cohort study, 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate or metal staples were applied for wound closure in spinal surgery. The aim of this cohort study was to assess the rate of SSI in spinal surgery using these two different methods of wound closure.

Patients and methods

A total of 609 consecutive patients undergoing spinal surgery in Wakayama Rosai Hospital from April 2007 to February 2012 were enrolled in the study. All patients were followed up for more than 1 year after operation. Patients undergoing microendoscopic decompression surgery for the lumbar spine and debridement combined with interbody fusion for pyogenic or tuberculous spondylitis were excluded. All spinal surgeries were performed by two doctors (M.A. and K.M.) who were specialists in spinal surgery. The patients were divided into two groups. From April 2007 to March 2010 surgical wounds were closed with metal staples (group 1, n = 294). After Smith’s report against metal staples [13], skin closure was performed using 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate (group 2, n = 315) from April 2010 to February 2012. Group 1 included 151 men and 143 women with a mean age at operation of 65.3 years (range 15–91 years). Group 2 included 173 men and 142 women with a mean age at operation of 66.4 years (range 13–94 years). The following additional data were collected: body mass index, serum albumin, red blood cell count, smoking history, steroid use, the presence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, malignant tumor, rheumatoid arthritis, obstructive lung disease or coronary artery disease, transfusion, diagnosis, region, surgical approach, instrumentation, revision, number of decompression levels, number of fusion levels, estimated blood loss and duration of operation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Group 1 (n = 294) | Group 2 (n = 315) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (n, %) | |||

| Male | 151 (51) | 173 (55) | 0.379 |

| Female | 143 (49) | 142 (45) | |

| Age at surgery (years) (range) | 65.3 (15–91) | 66.4 (13–94) | 0.304 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) (range) | 23.5 (11.3–34.7) | 23.8 (15.4–35.3) | 0.425 |

| Serum albumin (g/dl) (range) | 4.2 (2–5.2) | 4.2 (2.6–5.2) | 0.582 |

| Red blood cells (×104 μl) (range) | 428 (271–652) | 419 (267–564) | 0.040 |

| Smoking (n, %) | 66 (22) | 52 (17) | 0.064 |

| Steroid use (n, %) | 15 (5) | 10 (3) | 0.231 |

| Hypertension (n, %) | 109 (37) | 100 (32) | 0.166 |

| Diabetes mellitus (n, %) | 56 (19) | 79 (25) | 0.073 |

| Malignant tumor (n, %) | 5 (2) | 5 (2) | 0.834 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis (n, %) | 11 (4) | 9 (3) | 0.541 |

| Obstructive lung disease (n, %) | 16 (5) | 14 (4) | 0.570 |

| Coronary artery disease (n, %) | 18 (6) | 15 (5) | 0.459 |

| Diagnosis (n, %) | |||

| Degenerative disease | 272 (93) | 291(92) | 0.704 |

| Spine injury | 13 (4) | 17 (5) | |

| Spinal tumor | 9 (3) | 7 (2) | |

| Region (n, %) | |||

| Cervical | 81 (28) | 98 (31) | 0.179 |

| Thoracic | 30 (10) | 43 (14) | |

| Lumbar | 183 (62) | 174 (55) | |

| Surgical approach (n, %) | |||

| Anterior | 4 (1) | 4 (1) | 0.793 |

| Posterior | 290 (99) | 311 (99) | |

| Instrumentation (n, %) | 87 (30) | 96 (30) | 0.812 |

| Revision (n, %) | 35 (12) | 39 (12) | 0.857 |

| Number of decompression levels (n, %) | |||

| 1–2 | 55 (27) | 45 (21) | 0.015 |

| 3 | 51 (25) | 35 (16) | |

| 4–6 | 46 (46) | 128 (58) | |

| ≥7 | 5 (2) | 11 (5) | |

| Number of fusion levels (n, %) | |||

| 1–2 | 50 (57) | 51 (53) | 0.686 |

| 3 | 10 (11) | 15 (16) | |

| 4–6 | 20 (23) | 19 (20) | |

| ≥7 | 7 (8) | 11 (11) | |

| Estimated blood loss (g) (range) | 171.8 (2–1,951) | 237.4 (4–3,338) | 0.006 |

| Duration of operation (min) (range) | 164.0 (2–744) | 197.7 (39–775) | <0.001 |

| Transfusion (n, %) | 59 (20) | 93 (30) | 0.007 |

| Packed red blood cells (n, %) | 16 (5) | 25 (8) | 0.220 |

| Autologous blood (n, %) | 43 (15) | 68 (22) | 0.026 |

| SSI (n, %) | 8 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.009 |

| Superficial (n, %) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.449 |

| Deep (n, %) | 6 (2) | 0 (0) | 0.033 |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean (range)

Wound closure and postoperative wound care

In group 1, subcutaneous layers were closed with 2–0 absorbable sutures for wound adaptation and skin-edge approximation followed by skin closure with skin staples (PreciseTM Vista disposable skin stapler; 3 M, Maplewood, MN, USA). Wounds were covered with a post-surgical dressing (Opposite Post-Op Visible; Smith and Nephew Medical, Hull, UK). Staples were removed 10–14 days post-operation. In group 2, subcutaneous layers were closed in the same manner as that in group 1, followed by applying 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate (Dermabond® topical skin adhesive, Ethicon, Inc., NJ, USA) to skin incision. After crushing the inner vial, 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate was brushed on-to the skin incision. After the layers had dried, the wound was covered with the same post- surgical dressing as in group 1. Patients were allowed to shower on postoperative day 3. The post-surgical dressing was removed ~7–10 days after surgery.

Identification of SSIs was determined according to the criteria of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [27]. A wound infection occurring within 30 days of the operation in non-instrumented surgery and within 1 year in instrumented surgery was considered an SSI. A superficial SSI was defined as an infection involving only the skin and subcutaneous tissue, while an infection involving the deep soft-tissue muscle and fascia was designated a deep SSI. All SSIs were confirmed by specialists for orthopedic surgery (M.A., K.M. and S.S.)

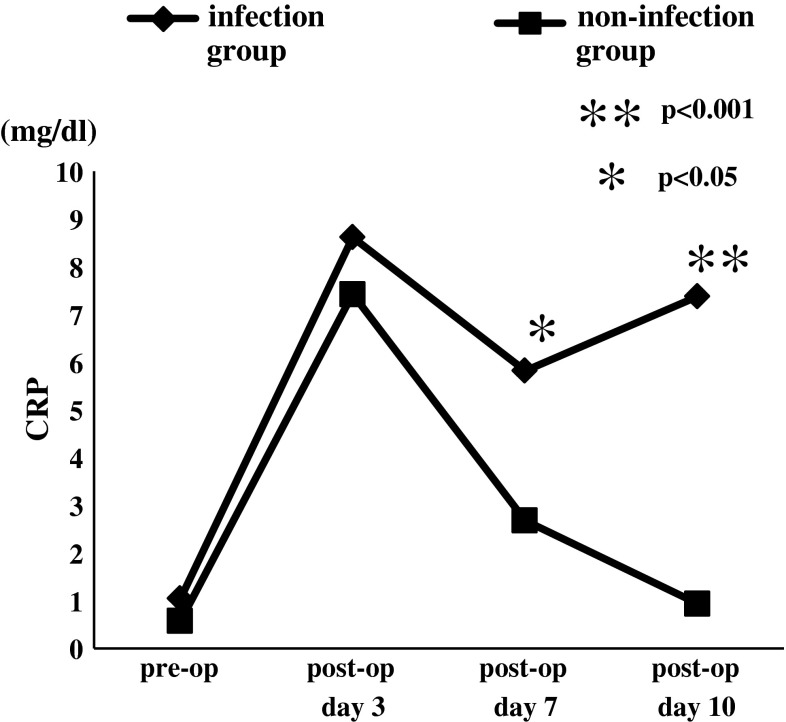

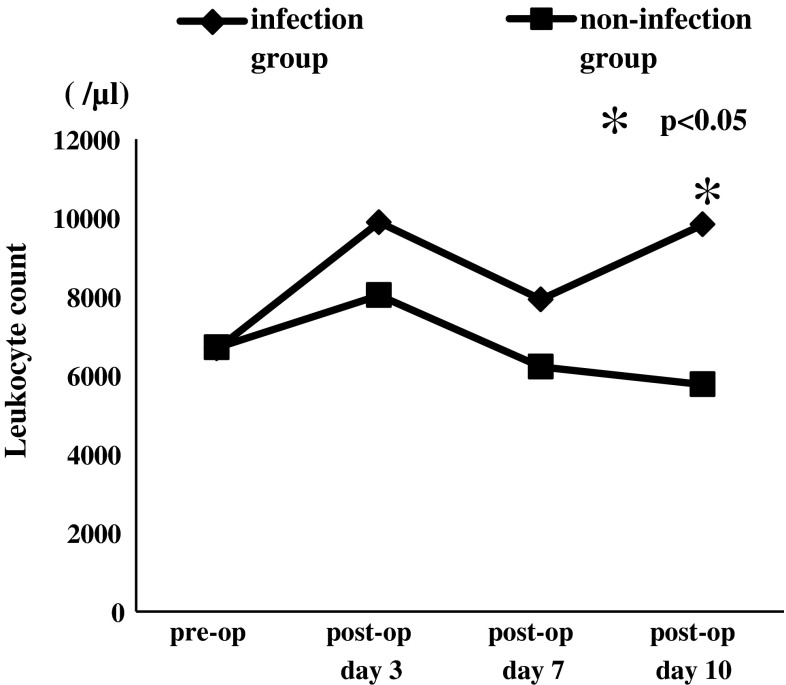

C-reactive protein (CRP) and leukocyte count were monitored as infection markers preoperatively and on postoperative days 3, 7 and 10 in all patients.

For intraoperative antimicrobial prophylaxis, cefazolin sodium (CEZ) or sulbactam sodium/ampicillin sodium (SBT/ABPC) was administrated by intravenous drip infusion at the induction of general anesthesia. CEZ was used for non-instrumented surgery while SBT/ABPC was used for instrumented surgery. Additional intraoperative injections of CEZ or SBT/ABPC were given every 3 h during surgery. Antibiotics were administrated every 6 h during the first 24 h after wound closure followed by the administration of every 12 h during second 24 h after operation, while closed-suction drainage was removed 48 h after surgery. The dose of CEZ administrated per one intraoperative injection was 1 g and the total dose after surgery was 6–8 g. A single dose of SBT/ABPC was 1.5 g and the total dose administered after surgery was 9–12 g.

Skin preparation was performed with 0.2 % benzalkonium chloride (WELPAS; Maruishi pharmacy, Osaka, Japan) and 10 % povidone iodine, followed by covering of the surgical field with an iodine-impregnated incision drape. Surgical staff used double gloves and changed the outer gloves every 3 h and just before wound closure. During surgery, pulse lavage using saline was performed every 3 h and just before wound closure to decrease intraoperative bacterial contamination. In addition, just before and after setting of instrument, pulse lavage irrigation was performed in instrumentation surgeries. The amount of saline used in one lavage was 1,000–2,000 ml depending on the size of operative field.

To analyze the time the surgeons needed for and the costs of these two different skin closures, wound closures of each ten patients with 7–20 cm wound length were observed prospectively. The time to closure was measured in seconds and the time to close the wound per 10 cm in length was calculated. The cost of wound closure was determined also.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t test, χ2 test. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

No patients showed adverse reaction such as an acute inflammation of erythema, warmth and pain for 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate use. Eight patients using staples (group 1) acquired SSIs (two patients with superficial SSIs and six with deep SSIs). There was no case of SSI in patients using 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate (group 2). Group 1 showed statistical significance with increased infection rates (p < 0.01). The red blood cell count was significantly lower (p < 0.05) in group 2 than in group 1, and the number of decompression levels (p < 0.05), estimated blood loss (p < 0.01) and duration of operation (p < 0.001) were significantly higher in group 2 than in group 1 (Table 1). In the comparison of patient characteristics in those with and without SSI in group 1, the rates of diabetes mellitus (p < 0.001), malignant tumor (p < 0.05), instrumentation surgery (p < 0.001) and transfusion, especially packed red blood cells (p < 0.001) were significantly higher in patients with SSI (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients with and without SSI in group 1

| Infected group (n = 8) | Non-infected group (n = 286) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (n, %) | |||

| Male | 4 (50) | 147 (51) | 0.938 |

| Female | 4 (50) | 139 (49) | |

| Age at surgery (years) (range) | 68.5 (52–83) | 65.2 (15–91) | 0.281 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) (range) | 23.6 (16.6–28.1) | 23.5 (11.3–34.7) | 0.315 |

| Serum albumin (g/dl) (range) | 4.3 (3.5–4.7) | 4.2 (2–5.2) | 0.606 |

| Red blood cells (×104 μl) (range) | 442.6 (397–496) | 427.2 (271–652) | 0.419 |

| Smoking (n, %) | 0 (0) | 66 (23) | 0.123 |

| Steroid use (n, %) | 0 (0) | 15 (5) | 0.506 |

| Hypertension (n, %) | 3 (38) | 106 (37) | 0.980 |

| Diabetes mellitus (n, %) | 4 (50) | 52 (18) | <0.001 |

| Malignant tumor (n, %) | 1 (13) | 4 (1) | 0.017 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis (n, %) | 0 (0) | 10 (3) | 0.590 |

| Obstructive lung disease (n, %) | 0 (0) | 15 (5) | 0.506 |

| Coronary artery disease (n, %) | 1 (13) | 17 (6) | 0.446 |

| Diagnosis (n, %) | |||

| Degenerative disease | 6 (75) | 266 (93) | 0.144 |

| Spine injury | 1 (13) | 12 (4) | |

| Spinal tumor | 1 (13) | 8 (3) | |

| Region (n, %) | |||

| Cervical | 1 (13) | 80 (28) | 0.130 |

| Thoracic | 3 (38) | 27 (9) | |

| Lumbar | 4 (50) | 179 (62) | |

| Surgical approach (n, %) | |||

| Anterior | 0 (0) | 4 (1) | 0.736 |

| Posterior | 8 (100) | 282 (99) | |

| Instrumentation (n, %) | 7 (88) | 80 (28) | <0.001 |

| Revision (n, %) | 1 (13) | 34 (12) | 0.958 |

| Number of decompression levels (n, %) | |||

| 1–2 | 1 (100) | 54 (26) | N/A |

| 3 | 0 (0) | 51 (25) | |

| 4–6 | 0 (0) | 96 (47) | |

| ≥7 | 0 (0) | 5 (2) | |

| Number of fusion levels (range) | |||

| 1–2 | 1 (14) | 49 (61) | 0.238 |

| 3 | 2 (29) | 8 (10) | |

| 4–6 | 3 (43) | 17 (21) | |

| ≥7 | 1 (14) | 6 (8) | |

| Estimated blood loss (g) (range) | 295.6 (5–1,014) | 158.3 (2–1,951) | 0.101 |

| Duration of operation (min) (range) | 245.4 (78–425) | 161.7 (22–744) | 0.102 |

| Transfusion (n, %) | 6 (80) | 53 (18) | <0.001 |

| Packed red blood cells (n, %) | 4 (50) | 12 (4) | <0.001 |

| Autologous blood (n, %) | 2 (30) | 41 (14) | 0.400 |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean (range)

When characteristics of infected patients were classified as instrumented and non-instrumented cases, there were no statistical significant differences in each factor (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of infected patients classified as instrumented and non-instrumented cases

| Instrumented cases (n = 6) | Non-instrumented cases (n = 2) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (n, %) | |||

| Male | 2 (33) | 2 (100) | 0.214 |

| Female | 4 (67) | 0 (0) | |

| Age at surgery (years) (range) | 68.5 (66–83) | 57.5 (52–63) | 0.067 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) (range) | 24.0 (20.4–28.1) | 21.4 (16.6–26.1) | 0.617 |

| Serum albumin (g/dl) (range) | 4.4 (4.1–4.7) | 3.9 (3.5–4.3) | 0.309 |

| Red blood cells (×104 μl) (range) | 457 (414–496) | 400 (397–403) | 0.067 |

| Smoking (n, %) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | N/A |

| Steroid use (n, %) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | N/A |

| Hypertension (n, %) | 2 (33) | 1 (50) | 0.893 |

| Diabetes mellitus (n, %) | 4 (67) | 0 (0) | 0.214 |

| Malignant tumor (n, %) | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 0.750 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis (n, %) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Obstructive lung disease (n, %) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 0.250 |

| Coronary artery disease (n, %) | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 0.750 |

| Diagnosis (n, %) | |||

| Degenerative disease | 5 (83) | 2 (100) | 0.750 |

| Spine injury | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Spinal tumor | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | |

| Region (n, %) | |||

| Cervical | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.536 |

| Thoracic | 2 (33) | 0 (0) | |

| Lumbar, ilium | 4 (67) | 2 (100) | |

| Surgical approach (n, %) | |||

| Anterior | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | N/A |

| Posterior | 6 (100) | 2 (100) | |

| Revision (n, %) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 0.250 |

| Number of decompression or fusion levels (n, %) | |||

| 1–2 | 1 (17) | 2 (100) | 0.108 |

| 3 | 2 (33) | 0 (0) | |

| 4–6 | 3 (50) | 0 (0) | |

| ≥7 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Estimated blood loss (g) (range) | 235 (50–1014) | 250.5 (5–496) | 0.868 |

| Duration of operation (min) (range) | 230 (150–335) | 251.5 (78–425) | 0.888 |

| Transfusion (n, %) | 5 (83) | 1 (50) | 0.464 |

| Packed red blood cells (n, %) | 3 (50) | 1 (50) | 0.786 |

| Autologous blood (n, %) | 2 (33) | 0 (0) | 0.536 |

Data are presented as n (%) or median (range)

In six of the eight patients with SSIs, methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) was isolated from cultures obtained from surgical wounds. Superficial SSIs were treated with debridement. Deep SSIs occurred in the instrumented area in four patients; two of these four-patients underwent removal of instrumentation (Table 4).

Table 4.

Characteristics of patients with SSI

| Age (years) | Gender | Type of SSI | Diagnosis | Operative procedure | Instrumentation of SSI site | Treatment for SSI | Microorganism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 63 | M | Deep | LDH | L4/5 discectomy | – | Debridement | Unknown |

| 83 | F | Deep | LSS | L2–5 PLF | + | Debridement | MRSA |

| 68 | F | Deep | LSS | L4–5 PLF | + | Removal of instrument | Unknown |

| 69 | F | Superficial | LSS | L2–5 PLF | + | Debridement | MRSA |

| 52 | M | Deep (Ilium, donor site) | C1/2 dislocation, CSM | OCT fusion | – | Debridement | MRSA |

| 66 | F | Deep | Spinal metastasis | T4–9 PLF | + | Removal of instrument | MRSA |

| 67 | M | Superficial | T12, L1 fracture | T10–L3 PLF | + | Debridement | MRSA |

| 80 | M | Deep | T12 fracture | T10–L3 PLF | + | Debridement | MRSA |

CSM cervical spondylotic myelopathy, F female, LDH lumbar disc herniation, LSS lumbar spinal stenosis, M male, MRSA methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, OCT occipito-cervico-thoracic, PLF posterolateral fusion, SSI surgical site infection

In both non-infection group and infection group, CRP and leukocyte count increased on postoperative day 3 and decreased on postoperative day 7. On postoperative day 10, CRP and leukocyte count increased again in infection group; however, non-infection group showed more decrement in CRP and leukocyte count. The mean value of CRP in infection group on pre-operation, postoperative day 3, 7 and 10 were 1.0 ± 1.9 mg/dl, 8.6 ± 2.8 mg/dl, 5.8 ± 4.2 mg/dl and 7.4 ± 9.5 mg/dl. Non-infection group values of CRP were 0.6 ± 1.6 mg/dl, 7.4 ± 4.7 mg/dl, 2.7 ± 2.3 mg/dl, 0.9 ± 1.4 mg/dl, respectively (Fig. 1). The mean measured leukocyte count in infected group on pre-operation, postoperative day 3, 7 and 10 were 6,675.0 ± 2,594.9, 9,885.7 ± 3,799.7, 7,925 ± 4,428.1 and 9,828.6 ± 4,525.4 while the count in non-infected group were 6,708.3 ± 1,907.4, 8,032.6 ± 2,120.9, 6,216.3 ± 1,764.6 and 5,768.2 ± 1,391, respectively (Fig. 2). CRP on postoperative day 7, 10 and leukocyte count on postoperative day 10 revealed significantly higher in infection group than those in non-infection group.

Fig. 1.

Mean values of CRP with and without postoperative infection. On postoperative days 7 and 10, CRP values showed significantly higher in infection group than those in non-infection group

Fig. 2.

Mean values of leukocyte count with and without postoperative infection. On postoperative day 10, leukocyte count showed significantly higher in infection group than that in non-infection group

The average time to close 10 cm wound was 48.0 ± 12.6 s in group 1 and 19.9 ± 10.7 s in group 2. Closing time using 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate was significantly faster than that using staples (p < 0.001). The cost of a single-use skin stapler (35 clips) was $38.5 while a set of 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate was $25.0. One set of 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate can be used for wound upto 12–13 cm in length. Since we usually use staples with 5–6 mm pitch, 12–13 cm wound was closed by 20–26 clips. Therefore, at least to this length of the wound, the use of 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate has a more cost-effectiveness than the use of staples.

Discussion

This cohort study found that in spinal surgery, wound closure using staples (group 1) was associated with a higher rate of SSI than wound closure using 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate (group 2), although the patients of group 2 had significant higher risk factors for surgical site infections than the patients in group 1. The only difference in SSI is the method of wound closure between two groups. Concerning the two groups, the patients are almost the same and all surgeries were performed by only two surgeons to avoid bias.

Several studies have reported disadvantages for wound closure with staples in terms of SSIs in orthopedic surgery [13, 28–30]. Another report emphasized that wound closure with staples, having a time-saving merit, might have a psychological benefit for surgeons and operating staff, especially after long-duration surgery [28, 31, 32].

Smith et al. [13] have reported a significantly higher risk of wound infection when wounds are closed with staples rather than sutures in orthopedic surgery. In hip surgery, the risk of developing a wound infection was four times greater after staple closure than suture closure. Smith et al. [13] recommended against the use of staples for wound closure in hip or knee surgery. Poor results for wound closure with staples are attributable to poor technique in clip placement, resulting in overlapping or inverted wound edges. This consequently leads to oozing from the wound edges, delayed healing and possible sites for infection [32]. There is a strong correlation between superficial wound infection and the probability of developing deep wound infection in hip and knee joint replacement [33]. Therefore, preventing superficial wound infection might decrease the rate of deep wound infection.

The benefits of wound closure with 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate include less procedure-related pain and time-savings. A hard barrier formed from these monomers sloughs off after the wound matures; there is no need to remove a non-absorbable suture, resulting in savings in time and resources for patients and medical staff [21]. In a study with bilateral reduction mammoplasties, operative times, rates of wound dehiscence, hypertrophic scar revisions and cellulitis were decreased with the use of 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate compared with suture closure [24]. Wound closure using 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate has also been reported to be associated with a low risk of SSI in spinal surgery [25, 26]. The low infection rate of wounds closed with 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate is possibly a result of antibacterial effects, particularly against gram-positive organisms [34] and the creation of an effective barrier to microbial penetration by gram-positive and gram-negative motile and non-motile species [35]. In addition, the avoidance of repeatedly compromising the skin barrier with a suture needle during the suturing process has been attributed to lowering the risk of infection [25].

Many factors increase the risk of SSI in spinal surgery. Patient-based risk factors are reported to be age [8], history of spinal surgery [36], previous SSI [1, 8], smoking [8, 36], steroid use [37], diabetes mellitus [8, 36, 38, 39], obesity [8, 39, 40], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [39], coronary heart disease [39], malignant tumor [41], anemia [42] and malnutrition [5]. Risk factors related to the surgical procedure are surgical level [6], number of fusion levels [36], transfusion [40], estimated blood loss [1, 40] and surgical duration [43]. In the current study, the red blood cell count was significantly lower in patients in group 2, while the number of decompression levels, estimated blood loss, duration of operation and transfusion rate were significantly higher in group 2. As anemia, an increased number of decompression levels, increased estimated blood loss, increased duration of operation time and transfusion are risk factors for SSI, patients in group 2 were more at risk for SSI than those in group 1. Nevertheless, no SSI occurred in group 2. In group 1, patients who developed SSI had more risk factors for SSI than those who did not develop an infection; the group of patients who developed SSI showed higher rates of diabetes mellitus, malignant tumor, instrumentation surgery and transfusion.

In this study for antimicrobial prophylaxis, the initial dose of CEZ and SBT/ABPC administrated was 1 and 1.5 g in all patients of group 1 and group 2. In our series there was no significant difference in BMI between infected patients and non-infected patients in group 1. However, obesity has consistently been reported as a risk factor for SSI [39]. Since standard doses of antimicrobial agents may result in low serum and tissue concentrations in obese patients, highest dose of prophylactic antimicrobial agent (for CEZ minimal initial dose of 2 g) was proposed to be used for bariatric surgical prophylaxis [44].

Early detection and immediate treatment for SSI are essential to obtain a good result. In this study the serial monitoring of CRP as an infection marker was useful for early detection of SSI. On the postoperative days 7 and 10, CRP showed a significant difference between infection group and non-infection group while leukocyte count revealed no significant difference on postoperative day 7. Similar results were reported previously. Kang et al. [45] mentioned that CRP value revealed a characteristic increase and decrease pattern after spinal surgery in patients with normal clinical course with regard to early infectious complications; therefore abnormal response at 5 or 7 days after surgery was the sign of SSI.

In our series, six of the eight (75 %) cases of SSI were due to MRSA. Recently, a consecutive series of 3,218 patients undergoing posterior lumbar instrumented surgery was reviewed by Koutsoumbelis et al. [39]. In this series, 34 % of SSIs revealed positive MRSA culture, indicating an increasing prevalence of this organism. According to other report [46] of 239 SSIs cases of spinal surgery methicillin-resistant organisms (S. aureus or S. epidermidis) were present in 82 (34.3 %) cases. Patients undergoing revision surgery were more likely to have an infection caused by methicillin-resistant staphylococci than those undergoing primary surgery (47.4 vs. 28.0 %). Spinal infection due to MRSA has been shown to be more difficult to treat and especially may increase mortality and morbidity when disseminated [47]. Management of SSI in posterior spinal surgery without instrumentation needs surgical debridement with removal of all necrotic tissue with surgical closure over drains [48] while SSI in instrumented surgery both interbody and posterior instrumentation can be left in place in the setting of early postoperative infections [5, 39, 49]. However, postoperative spine wound infection with positive culture for MRSA predicts a high tendency of failure to suppress the infection with a single irrigation and debridement [50].

Prospective study of the time and cost evaluation revealed that closure of the wound in length of 10 cm with 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate could save 28 s and $13.5. Because the use of 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate has a more time saving and cost-effectiveness than the use of staples in wound closure of 10 cm in length, from a time saving and a cost effective points of view, 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate can be used.

Preventive measures for SSI used in this study (i.e. antimicrobial prophylaxis, skin preparation of the surgical field, using double gloves during surgery and intraoperative lavage with saline) were the same in both groups. The only difference that influenced the higher SSI rate in group 1 is the method of wound closure. This study found that in spinal surgery, wound closure using 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate was associated with a lower rate of SSI than wound closure with staples.

Conflict of interest

No funds were received in support of this work. No benefits in any form have been or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Pull ter Gunne AF, van Laarhoven CJ, Cohen DB. Incidence of surgical site infection following adult spinal deformity surgery: an analysis of patient risk. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:982–988. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-1269-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calderone RR, Garland DE, Capen DA, Oster H. Cost of medical care for postoperative spinal infections. Orthop Clin North Am. 1996;27:171–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubinstein E, Findler G, Amit P, Shaked I. Perioperative prophylactic cefazolin in spinal surgery. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial. J Bone Jt Surg. 1994;76-B:99–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wimmer C, Gluch H, Franzreb M, Ogon M. Predisposing factors for infection in spine surgery: a survey of 850 spinal procedures. J Spinal Disord. 1998;11:124–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinstein MA, McCabe JP, Cammisa FP., Jr Postoperative spinal wound infection: a review of 2,391 consecutive index procedures. J Spinal Disord. 2000;13:422–426. doi: 10.1097/00002517-200010000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blam OG, Vaccaro AR, Vanichkachorn JS, Albert TJ, Hilibrand AS, Minnich JM, Murphey SA. Risk factors for surgical site infection in the patient with spinal injury. Spine. 2003;28:1475–1480. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000067109.23914.0A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olsen MA, Mayfield J, Lauryssen C, Polish LB, Jones M, Vest J, Fraser VJ. Risk factors for surgical site infection in spinal surgery. J Neurosurg. 2003;98(2 Suppl):149–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fang A, Hu SS, Endres N, Bradford DS. Risk factors for infection after spinal surgery. Spine. 2005;30:1460–1465. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000166532.58227.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demura S, Kawahara N, Murakami H, Nambu K, Kato S, Yoshioka K, Okayama T, Tomita K. Surgical site infection in spinal metastasis: risk factors and countermeasures. Spine. 2009;34:635–639. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31819712ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tofuku K, Koga H, Yanase M, Komiya S. The use of antibiotic-impregnated fibrin sealant for the prevention of surgical site infection associated with spinal instrumentation. Eur Spine J. 2012;21:2027–2033. doi: 10.1007/s00586-012-2435-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh B, Mowbray MAS, Nunn G, Mearns S. Closure of hip wound, clips or subcuticular sutures: does it make a difference? Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2006;16:124–129. doi: 10.1007/s00590-005-0043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singhal AK, Hussain A. Skin closure with automatic stapling in total hip and knee arthroplasty. JK Practit. 2006;13:142–143. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith TO, Sexton D, Mann C, Donell S. Sutures versus staples for skin closure in orthopaedic surgery: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;340:c1199. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quinn JV, Drzewiecki A, Li MM, Stiell IG, Sutcliffe T, Elmslie TJ, Wood WE. A randomized, controlled trial comparing a tissue adhesive with suturing in the repair of pediatric facial lacerations. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22:1130–1135. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(05)80977-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikada Y. Tissue adhesives. In: Chu CC, Greisler HP, Von Fraunhofer JA, editors. Wound closure biomaterials and devices. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1997. pp. 317–346. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farion K, Osmond MH, Hartling L, Russell K, Klassen T, Crumley E, Wiebe N. Tissue adhesives for traumatic lacerations in children and adults. Cochr Datab Sys Rev. 2002;3:CD003326. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liebelt EL. Current concepts in laceration repair. Curr Opin Pediatr. 1997;9:459–464. doi: 10.1097/00008480-199710000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collin TW, Blyth K, Hodgkinson PD. Cleft lip repair without suture removal. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:1161–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2008.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho J, Harrop J, Veznadaroglu E, Andrews DW. Concomitant use of computer image guidance, linear or sigmoid incisions after minimal shave, and liquid wound dressing with 2-octyl cyanoacrylate for tumor craniotomy or craniectomy: analysis of 225 consecutive surgical cases with antecedent historical control at one institution. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:832–840. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000054219.35102.B4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee KW, Sherwin T, Won DJ. An alternate technique to close neurosurgical incisions using octyl cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1999;31:110–114. doi: 10.1159/000028844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang MY, Levy ML, Mittler MA, Liu CY, Johnston S, McComb JG. A prospective analysis of the use of octyl cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive for wound closure in pediatric neurosurgery. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1999;30:186–188. doi: 10.1159/000028792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leung GY, Peponis V, Varnell ED, Lam DS, Kaufman HE. Preliminary in vitro evaluation of 2-octyl cyanoacrylate (Dermabond) to seal corneal incisions. Cornea. 2005;24:998–999. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000159734.75672.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee J, Singletary R, Schmader K, Anderson DJ, Bolognesi M, Kaye KS. Surgical site infection in the elderly following orthopaedic surgery. Risk factors and outcomes. J Bone Jt Surg. 2006;88-A:1705–1712. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott GR, Carson CL, Borah GL. Dermabond skin closures for bilateral reduction mammaplasties: a review of 255 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120:1460–1465. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000282032.05203.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall LT, Bailes JE. Using Dermabond for wound closure in lumbar and cervical neurosurgical procedures. Neurosurgery. 2005;56(1 Suppl):147–150. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000144170.39436.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wachter D, Brückel A, Stein M, Oertel MF, Christophis P, Böker DK. 2-Octyl-cyanoacrylate for wound closure in cervical and lumbar spinal surgery. Neurosurg Rev. 2010;33:483–489. doi: 10.1007/s10143-010-0258-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Martone WJ, Jarvis WR, Emori TG. CDC definitions of nosocomial surgical site infections, 1992: a modification of CDC definitions of surgical wound infections. Inf Cont Hosp Epidemiol. 1992;13:606–608. doi: 10.2307/30148464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stockley I, Elson RA. Skin closure using staples and nylon sutures: a comparison of results. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1987;69:76–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shetty AA, Kumar VS, Morgan-Hough C, Georgeu GA, James KD, Nicholl JE. Comparing wound complication rates following closure of hip wounds with metallic skin staples or subcuticular vicryl suture: a prospective randomised trial. J Orthop Surg. 2004;12:191–193. doi: 10.1177/230949900401200210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh B, Mowbray MAS, Nunn G, Mearns S. Closure of hip wound, clips or subcuticular sutures: does it make a difference? Eur J Ortop Surg Traumatol. 2006;16:124–129. doi: 10.1007/s00590-005-0043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gatt D, Quick CR, Owen-Smith MS. Staples for wound closure: a controlled trial. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1985;67:318–320. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murphy M, Prendergast P, Rice J. Comparison of clips versus sutures in orthopedic wound closure. Eur J Ortop Surg Traumatol. 2004;14:16–18. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saleh K, Olson M, Resig S, Bershadsky B, Kuskowski M, Gioe T, Robinson H, Schmidt R, McElfresh E. Predictors of wound infection in hip and knee joint replacement: results from a 20 year surveillance program. J Orthop Res. 2002;20:506–515. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00153-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quinn JV, Osmond MH, Yurack JA, Moir PJ. N-2 butyl cyanoacrylate: risk of bacterial contamination with an appraisal of its antimicrobial effects. J Emerg Med. 1995;13:581–585. doi: 10.1016/0736-4679(95)80025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhende S, Rothenburger S, Spangler DJ, Dito M. In vitro assessment of microbial barrier properties of Dermabond topical skin adhesive. Surg Inf (Larchmt) 2002;3:251–257. doi: 10.1089/109629602761624216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schimmel JJ, Horsting PP, de Kleuver M, Wonders G, van Limbeek J. Risk factors for deep surgical site infections after spinal fusion. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:1711–1719. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1421-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McPhee IB, Williams RP, Swanson CE. Factors influencing wound healing after surgery for metastatic disease of the spine. Spine. 1998;23:726–732. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199803150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen S, Anderson MV, Cheng WK, Wongworawat MD. Diabetes associated with increased surgical site infections in spinal arthrodesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:1670–1673. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0740-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koutsoumbelis S, Hughes AP, Girardi FP, Cammisa FP, Jr, Finerty EA, Nguyen JT, Gausden E, Sama AA. Risk factors for postoperative infection following posterior lumbar instrumented arthrodesis. J Bone Jt Surg. 2011;93-A:1627–1633. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwarzkopf R, Chung C, Park JJ, Walsh M, Spivak JM, Steiger D. Effects of perioperative blood product use on surgical site infection following thoracic and lumbar spinal surgery. Spine. 2010;35:340–346. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b86eda. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Veeravagu A, Patil CG, Lad SP, Boakye M. Risk factors for postoperative spinal wound infections after spinal decompression and fusion surgeries. Spine. 2009;34:1869–1872. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181adc989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abdul-Jabbar A, Takemoto S, Weber MH, Hu SS, Mummaneni PV, Deviren V, Ames CP, Chou D, Weinstein PR, Burch S, Berven SH. Surgical site infection in spinal surgery: description of surgical and patient-based risk factors for postoperative infection using administrative claims data. Spine. 2012;37:1340–1345. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318246a53a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boston KM, Baraniuk S, O’Heron S, Murray KO. Risk factors for spinal surgical site infection, Houston, Texas. Inf Cont Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30:884–889. doi: 10.1086/605323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chopra T, Zhao JJ, Alangaden G, Wood MH, Kaye KS. Preventing surgical site infections after bariatric surgery: value of perioperative antibiotic regimens. Exp Rev Pharmacoecon Outcom Res. 2010;10:317–328. doi: 10.1586/erp.10.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kang BU, Lee SH, Ahn Y, Choi WC, Choi YG. Surgical site infection in spinal surgery: detection and management based on serial C-reactive protein measurements. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;13:158–164. doi: 10.3171/2010.3.SPINE09403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abdul-Jabbar A, Berven SH, Hu SS, Chou D, Mummaneni PV, Takemoto S, Ames C, Deviren V, Tay B, Weinstein P, Burch S, Liu C. Surgical site infections in spine surgery: identification of microbiologic and surgical characteristics in 239 cases. Spine. 2013;38:E1425–E1431. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182a42a68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al-Nammari SS, Lucas JD, Lam KS. Hematogenous methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus spondylodiscitis. Spine. 2007;32:2480–2486. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318157393e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meredith DS, Kepler CK, Huang RC, Brause BD, Boachie-Adjei O. Postoperative infections of the lumbar spine: presentation and management. Int Orthop. 2012;36:439–444. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1427-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pappou IP, Papadopoulos EC, Sama AA, Girardi FP, Cammisa FP. Postoperative infections in interbody fusion for degenerative spinal disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;444:120–128. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000203446.06028.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dipaola CP, Saravanja DD, Boriani L, Zhang H, Boyd MC, Kwon BK, Paquette SJ, Dvorak MF, Fisher CG, Street JT. Postoperative infection treatment score for the spine (PITSS): construction and validation of a predictive model to define need for single versus multiple irrigation and debridement for spinal surgical site infection. Spine J. 2012;12:218–230. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]