Abstract

The involvement of hyperactive polyisoprenylated proteins in cancers has stimulated the search for drugs to target and suppress their excessive activities. Polyisoprenylated methylated protein methyl esterase (PMPMEase) inhibition has been shown to modulate polyisoprenylated protein function. For PMPMEase inhibition to be effective against cancers, polyisoprenylated proteins, the signaling pathways they mediate and/or PMPMEase must be overexpressed, hyperactive and be involved in at least some cases of cancer. PMPMEase activity in lung cancer cells and its expression in lung cancer cells and cancer tissues were investigated. PMPMEase was found to be overexpressed and significantly more active in lung cancer A549 and H460 cells than in normal lung fibroblasts. In a tissue microarray study, PMPMEase immunoreactivity was found to be significantly higher in lung cancer tissues compared to the normal controls (p < 0.0001). The mean scores ± SEM were 118.8 ± 7.7 (normal), 232.1 ± 25.1 (small-cell lung carcinomas), 352.1 ± 9.4 (squamous cell carcinomas), 311.7 ± 9.8 (adenocarcinomas), 350.0 ± 24.2 (papillary adenocarcinomas), 334.7 ± 30.1 (adenosquamous carcinomas), 321.9 ± 39.7 (bronchioloalveolar carcinomas), and 331.3 ± 85.0 (large-cell carcinomas). Treatment of lung cancer cells with L-28, a specific PMPMEase inhibitor, resulted in concentration-dependent cell death (EC50 of 8.5 μM for A549 and 2.8 μM for H460 cells). PMPMEase inhibition disrupted actin filament assembly, significantly inhibited cell migration and altered the transcription of cancer-related genes. These results indicate that elevated PMPMEase activity spur cell growth and migration, implying the possible use of PMPMEase as a protein biomarker and drug target for lung cancer.

Keywords: Polyisoprenylation, esterase, Ras, lung cancer, isoprenylation, methylation, nanostring, monomeric G-proteins

Introduction

Lung cancer is the second most prevalent form of cancer in the United States and is ranked as the leading cause of cancer-related deaths both in the United States and around the world [1,2]. In 2013, an estimated 228,190 new cases of lung cancer will be diagnosed and 159,480 will die from the disease (26% of all female cancer deaths and 28% of all male cancer death) in the United States alone [1]. Lung cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer as well as the leading cause of cancer deaths in males worldwide [1,3]. The increased incidence of lung cancer, especially in the United States and other developed countries, has been linked mainly to smoking and urbanization-related environmental pollution [4,5]. Of the two main histological categories of lung cancer, small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) is less prevalent (14%) although it is the more aggressive form, with a 5-year survival rate of only 6% compared to 17% for the non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [5]. NSCLC comprises 80-85% of lung cancer cases which are categorized as adenocarcinoma, squamous cell and large cell anaplastic carcinomas [6]. Treatment options, which include surgical resection, radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy, depend on the clinical stage and other patient factors [7,8]. With only 15.9% overall 5-year survival rate for all stages of lung cancer combined, there is a need to search for other, more effective management options [3,5,9].

Polyisoprenylated proteins play important roles in carcinogenesis [10,11]. Such proteins that include the Ras superfamily [11,12] are essential regulators of cell proliferation, differentiation, motility, apoptosis, intracellular signaling and cytoskeletal organization [13,14]. Indeed, the members of the Ras superfamily of small GTP-binding proteins mediate signaling pathways that regulate metastasis in cancer cells [10,15]. Studies have shown that up to 30% of lung adenocarcinomas are associated with K-Ras mutations [16,17]. Altered expression of the Ras proteins seen mostly in smokers frequently occurs in lung adenocarcinomas [18]. Efficient localization of Ras to the inner surface of plasma membranes and its expression of biological activity is dependent on polyisoprenylation followed by carboxymethylation at the carboxyl-terminal [19]. Enzymes of the polyisoprenylation pathway have thus been widely investigated for the development of anticancer agents [13,20,21]. Farnesyltransferase inhibitors such as Tipifarnib and Lonafarnib were evaluated in clinical trials for anticancer treatment but found to be less effective [22,23].

Polyisoprenylated protein methyl transferase (PPMTase) has also been the target of anticancer drug development efforts [24]. Although the research targeting the polyisoprenylation pathway has been geared mainly towards finding treatments for cancers with aberrantly active Ras proteins, the fact that cancer-promoting changes also occur upstream of the Ras proteins in the growth signaling pathway imply that effective anti-Ras agents may also be useful for cancers with hyperactive growth factors and their receptors. The epidermal growth factor and/or its receptors are hyperactive in cancers due either to overexpression and/or gain-in-function mutations [25]. In non-small cell lung cancer, 43-89% of the cases overexpress epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) or harbor hyperactive mutated forms [26].

Polyisoprenylated methylated protein methyl esterase (PMPMEase, EC 3.1.1.1) hydrolyzes the ester products of PPMTase at the terminal only reversible step of the pathway [27]. PMPMEase thus appears pivotal to the processing and functioning of polyisoprenylated proteins. PMPMEase as polyisoprenylation-dependent esterase was first identified in our laboratory [28] and its unique ability to selectively hydrolyze polyisoprenylated substrates was demonstrated with a series of substrates and cholinesterase enzymes [29]. We previously determined that PMPMEase might be a key regulator of cell growth using polyisoprenylated sulfonyl fluoride inhibitors which caused significant morphological changes and degeneration of human neuroblastoma cells [30]. Amissah and co-workers further demonstrated that inhibition of PMPMEase with polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) also causes cancer cell death [31,32]. The notion that PMPMEase activity correlates with cell viability also stems from the evidence that cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) is overexpressed in most tumors [33,34], cancer risks are lowered due to the consumption of foods rich in PUFAs [35] and/or the long term use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [36] coupled with the findings that PMPMEase and cell viability are both inhibited by PUFAs but not prostaglandins [31,32]. That PMPMEase or human carboxyesterase 1 (CES1) activity is indeed important for polyisoprenylated protein metabolism, activity and function, has recently been confirmed in studies with PMPMEase siRNA on RhoA methylation status, activation, and its effects on F-actin and cell morphology [37]. We thus hypothesized that PMPMEase is overexpressed and therefore hyperactive at least in some cases of lung cancer. As such, it would be a suitable candidate for further investigation as an early/companion diagnostic biomarker and target for therapeutic drug development. Therefore, the overexpression of PMPMEase in 88.3% of the over 400 lung cancer cases strongly supports a link between PMPMEase hyperactivity and lung cancer and that targeting this enzyme for specific inhibition constitutes a valid and novel strategy to clinically manage lung cancer.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human lung fibroblasts (WI-38) cells and human lung cancer (A549 and H460) cells were purchased from, authenticated and certified by American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). WI-38 cells were cultured in Minimum Essential Medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), A549 cells were cultured in F12 Kaighn’s Medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and H460 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). All media were supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The cultures were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2/95% humidified air.

Cell viability assays

The lung cell lines (WI-38, A549 and H460) were seeded at a density of 2 × 104 per well in 96-well tissue culture plates and allowed to attach overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2/95% humidified air. The cells were then treated with 2-trans, trans-farnesylthioethanesulfonyl fluoride (L-28) which was synthesized as previously described [30]. L-28 (1-200 μM) was dissolved in acetone (solvent, final concentration of 1% in wells). Control cells were treated with 1% of acetone. Identical amounts of L-28 were used to supplement the samples at 24 h for the 48 h exposure and 24 and 48 h for the 72 h exposure. CellTiter-Blue Cell Viability Assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI) was used to determine the cell viability as previously described [32]. Cell viability was expressed as the percentage of the fluorescence in the treated cells relative to that of the controls. Cell proliferation assay was also conducted on the lung cancer cells by exploring the cell viability before the initial treatment and after final treatment. The differences between the initial and final viabilities were quantified as the cell proliferation. In another experiment to determine cell recovery after treatment, media were removed from treated cells and replaced with drug-free growth media for 48 h to observe whether degenerating cells could be revived. Cell viability was measured and expressed as the percentage of the fluorescence in the treated cells relative to that of the controls.

Effect of PMPMEase inhibition on clonogenic cell survival

Clonogenic cell survival was evaluated by concentration-survival fractions as determined by a colony-forming assay. Exponential growing cells were seeded into 6-well culture plates at a density of 1 × 103 cells/well and left at 37°C for 24 h to attach. L-28 (5 and 10 μM) or 1 μL of acetone (carrier solution) were then added to triplicate wells. Identical amounts of L-28 were used to supplement the samples at 24 h and 48 h for 72 h exposure. After 72-h incubation, plates were washed twice in serum-free medium and incubated in fresh drug-free medium containing 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum for an additional 7 days. The resulting colonies were fixed with a 10:1 (v/v) mixture of methanol and acetic acid. These were stained with 1% crystal violet and the number of colonies containing > 50 cells were counted. Cell survival following L-28 exposure was expressed as the percentage of control survival.

Western blot analysis

Whole-cell lysates were prepared from lung cancer cells in modified immunoprecipitation buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM NaF, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% [wt/vol] sodium deoxycholate, and 1% Triton X-100) containing phosphatase and protease inhibitors. Lysates containing 50 μg of protein were mixed with SDS-PAGE sample buffer, placed in boiling water bath for 5 min and separated by SDS-PAGE. Purified porcine PMPMEase (1.6 μg) was applied to one of the lanes as a positive control. Resolved proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, and the membranes were blocked with 3% BSA solution for 1 hour at room temperature and incubated at 4°C overnight with rabbit polyclonal human carboxylesterase 1 antibody (Santa Cruz biotechnology, CA). Membranes were then incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Immunoreactivity was detected using nitro-blue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3’-indolyphosphate solution (Santa Cruz biotechnology, CA) as an alkaline phosphatase substrate.

PMPMEase activity in lung cancer cells

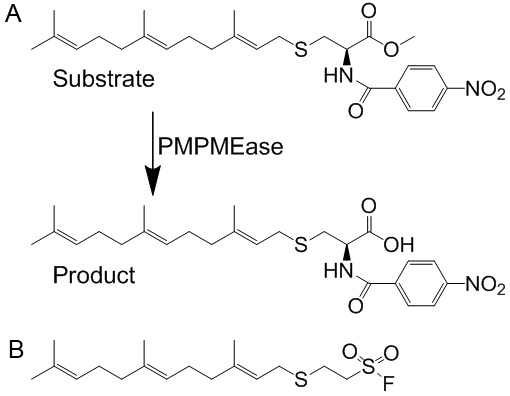

PMPMEase activity was assayed using a previously established method [29] incorporating the specific PMPMEase substrate, N-(4-nitrobenzoyl)-S-trans, trans-farnesyl-L-cysteine methyl ester synthesized in our laboratory as previously described [29] (Figure 1A). The hydrolysis of the substrate to product is sensitive to the PMPMEase specific inhibitor, L-28 (Figure 1B) [30]. Cells were cultured in 175 cm2 vented culture flasks at 37°C in 5% CO2/95% humidified air to confluence. The cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline, lysed with Triton-X 100 (0.1%) in 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4 containing EDTA (1 mM). Aliquots of the resulting lysate were incubated with N-(4-nitrobenzoyl)-S-trans, trans-farnesyl-L-cysteine methyl ester substrate (1 mM) in a total reaction volume of 100 μL at 37°C for 3 h and analyzed by HPLC as previously described [29]. The total protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford reagent. To establish the effect L-28 on PMPMEase activity in the lung cells, aliquots of the resulting lysate were pre-incubated for 10 min with L-28 (0.1-1000 μM) followed by assay for residual enzymatic activity.

Figure 1.

A. Schematic representation of the hydrolysis of the specific PMPMEase substrate, RD-PNB, to the product. B. Structure of the specific PMPMEase inhibitor, L-28.

Apoptosis assay

The mode of cell death induced by L-28 was determined by the modified EB/OA staining method [31,38]. A549 cells were seeded onto 24-well plates at a density of 1.5 × 105 cells and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2/95% humidified air. These were then treated with L-28 (0-10 μM) and incubated for 48 h at 37°C before staining with EB/AO. A solution containing both EB and AO was added to each well to a final concentration of 10 μg/mL and incubated in the dark for 15 min. The cells were viewed under a Zeiss microscope using 480/30 nm excitation filter. Images of the cells were captured with an Olympus DP70 Camera. The conventional EB/AO staining was also employed to quantify apoptosis [38,39]. Briefly, A549 cells treated with L-28 (0-10 μM) and incubated for 48 h at 37°C were harvested by transferring the media into 15 ml tubes. The rest of the cells were detached with Dulbecco’s PBS containing 1 mM EDTA and added to the transferred media. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 130 g for 5 minutes, washed with 1 mL of cold PBS and the cell pellets re-suspended in 25 μL of cold PBS and 2 μL EB/AO dye mix was added. Stained cell suspensions (10 μL) were placed on clean microscope slides and covered with coverslips. The cells were viewed and counted under the microscope at 40 × magnification using 480/30 nm excitation filter. The counts were conducted in triplicates with a minimum of 100 cells counted per replicate.

Effect of PMPMEase inhibition on lung cancer cell migration

Scratch assay was conducted to determine the effect of L-28 on A549 cell motility. The cells were seeded at a density of 2.5 × 105 in a 24 well plate. After 24 h, the medium was removed and replaced with medium containing 10% FBS. When the cells reached full confluence, the monolayers were wounded by scratching the surface as uniformly and straight as possible using a sterile 10 μL pipette tip at least three times. The cells were washed once with complete media to remove detached cells followed by the acquisition of the original image of the wound under a microscope. The wounded cell monolayer was then incubated with the cell culture medium containing an appropriate concentration of L-28 (0.5-1.0 μM). Images of the cells invading the scratch were captured with an Olympus DP70 Camera at indicated time points (0, 6, and 12 h). The pictures were analyzed and the width of the wounds measured using NIH ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). The difference between the widths is taken as the migration distance.

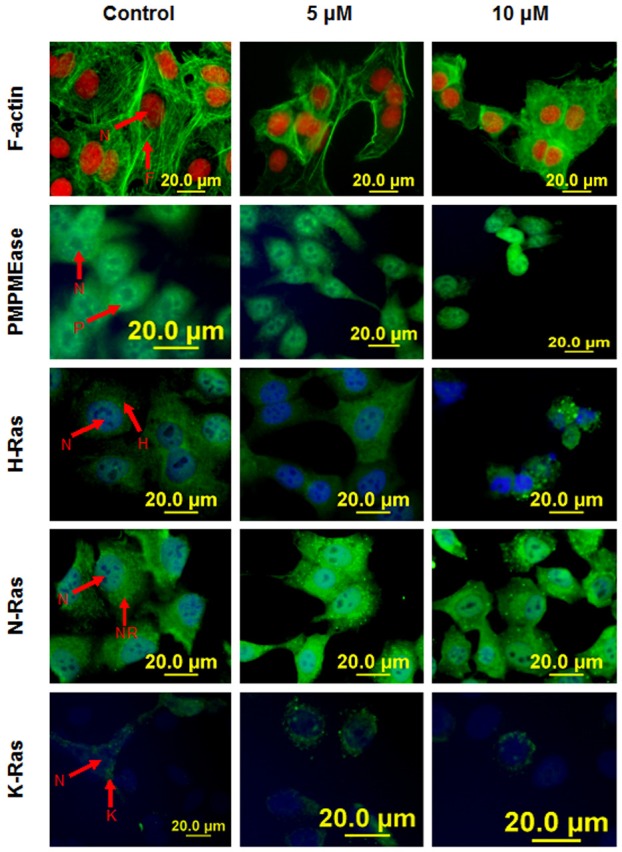

Effect of PMPMEase inhibition on F-actin filaments organization and cellular localization of PMPMEase and Ras proteins

To visualize the effect of L-28 on F-actin organization and localization of PMPMEase, K-ras, H-ras and N-ras, immunofluorescence analyses were performed on L-28-treated A549 cells in 4-well Lab-tek II chambers (Nalge Nunc International, NY). The cells were fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde (Sigma, MO) in PBS for 15 min at room temperature. After washing with PBS, the cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma, MO) for 5 min on ice and blocked with 1% BSA in PBS for 1 h at 4°C. To visualize F-actin organization, phalloidin (Biotium, CA) and propidium iodide (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) fluorescence staining were performed. To study the localization of PMPMEase, K-ras, H-ras and N-ras, the cells were incubated with the respective rabbit polyclonal antibodies against PMPMEase, K-Ras, H-ras or N-ras (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA) in 1% BSA in PBS overnight. After washing in PBS, the cells were incubated with flourescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA) for 1 h at room temperature in a humidified chamber. The cells were washed with PBS, stained with DAPI (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at a concentration of 0.1 μg/ml in PBS and mounted on microscope slides. These were then viewed on a Zeiss fluorescent microscope and the images captured with an Olympus DP70 Camera.

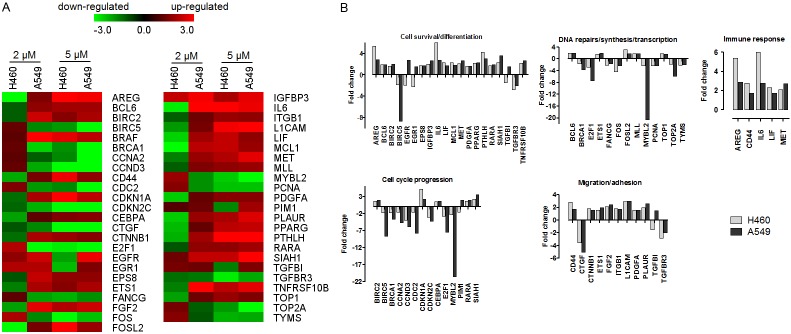

Effect of PMPMEase inhibition on the expression of cancer-related genes

Lung cancer A549 and H460 cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 per well in 24-well culture plates and allowed to attach overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2/95% humidified air. The cells were then treated with either solvent (control) or L-28 at 2 μM and 5 μM. After 48 h of treatment, the cells were detached with trypsin, washed once with PBS, counted and 10000 cells were lysed in 5 μL RLT buffer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The analysis for the relative expression of cancer-related genes was conducted using the nCounter GX Human Cancer References Kit for profiling cancer-related genes (NanoString Technologies, Seattle, WA) at the Oncogenomics Core Facility of the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. The raw nanoString counts were analyzed using the nSolver Software (NanoString Technologies, Seattle, WA) as previously described [40]. Briefly, the data were normalized using positive control spikes to correct for any such experimental variables between the samples as differences in efficiency in hybridization, purification or binding. This normalization is conducted on all nanoString counts by multiplying them with a normalization factor. The normalization factor is calculated by averaging the sum of the counts for all positive hybridization controls for each sample divided by the sum for each sample. The normalization factor within the required range was between 0.3-3. In addition, the data were normalized for RNA content using housekeeping genes and multiplying all counts by a calculated normalization factor. The normalization is optimized using multiple housekeeping genes that include those with high and low expression levels (CLTC, GAPDH, GUSB, HPRT1, PGK1, TUBB). This normalization factor is calculated by the average of the geometric mean of all the housekeeping gene counts for each sample divided by the geometric mean of each sample. Also, the average of negative controls consisting of eight codes with no transcript representing background noise was subtracted from the normalized gene counts. Multi Experiment Viewer (MeV v4.6.2) was employed to cluster the data sets to obtain the heat maps resulting from the numerical fold-change expression levels compared to the control. Heat maps were obtained by clustering based on Manhattan Distance. Prior to clustering, the data was filtered using criteria set such that only data values ≥ 3-fold changes were employed. A total of 47 genes passed the filtering criteria and were used for the heat map analyses. Color scale limits were set at “-3.0, 0.0, 3.0”, meaning that the brightest red represents ≥ 3-fold upregulation relative to the controls, the brightest green represents ≥ 3-fold downregulation, and black represents no change. The 47 genes were further grouped based on their main functions, and bar graphs indicating their relative expression levels were obtained using Graphpad Prism version 4.0 for Windows (San Diego, CA).

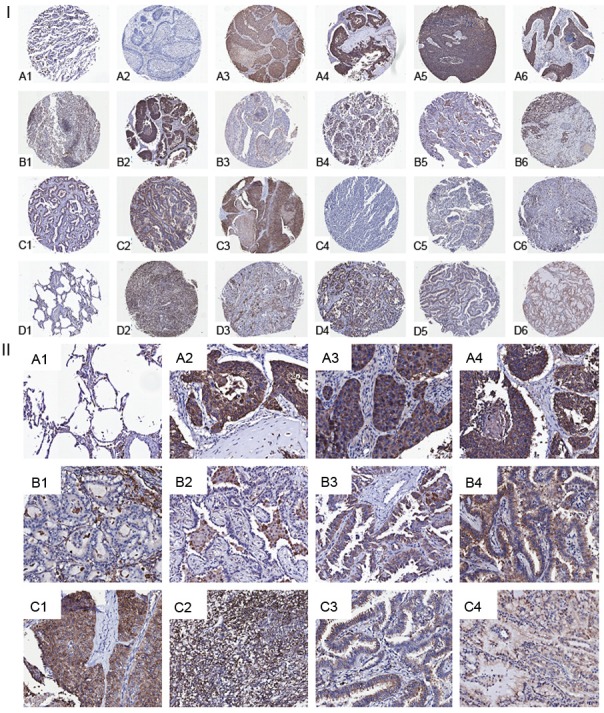

PMPMEase expression in lung cancer tissues

The expression of PMPMEase in lung cancer tissues was determined using immunohistochemical analysis as previously described [41] using human lung cancer and normal adjacent tissue microarrays (TMAs) comprising a total of 416 cores from 416 distinct cases. The tissues used were supplied by, and the immunohistochemistry conducted at US Biomax (Rockville, MD).

Statistical analysis

All results were expressed as the means ± S.E.M. The concentration-response curves were obtained by plotting the percent inhibition against the log of the inhibitor concentrations. Nonlinear regression plots were generated using Graphpad Prism version 4.0 for Windows (San Diego, CA). From these, the concentrations that inhibit 50% of the activity (IC50) were calculated. The tissue microarrays data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA using SAS 9.2 software (SAS Institute, Cary NC). Statistical differences between normal and cancer tissues were determined using Bonferroni’s procedure for multiple comparisons. The Bonferroni procedure takes into account the number of means to be compared and is more conservative than other multiple comparison methods. P-values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

PMPMEase inhibition suppresses lung cancer cell viability

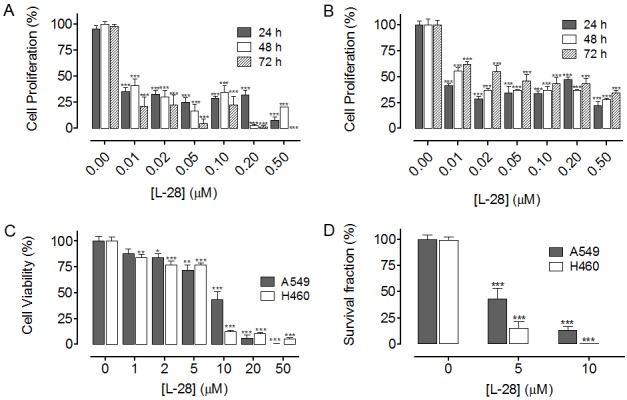

Previous studies revealed that PMPMEase inhibition induced cancer cell death [30,32], suggesting that PMPMEase activity may be increased in cancers. We therefore examined whether PMPMEase activity is increased in cancer cells. When cell lysates were analyzed for cellular PMPMEase activity, significantly higher specific activities were observed in lung cancer A549 (5.2 ± 0.10 nmol/h/mg of protein) and H460 (4.8 ± 0.05 nmol/h/mg of protein) compared to normal lung WI-38 cells (3.2 ± 0.04 nmol/h/mg of protein) (Figure 2A). This was confirmed by western blot analysis to be due to higher expression levels of PMPMEase in the cancer cells relative to the normal cells (Figure 2B). We further examined whether inhibition of PMPMEase activity by the specific inhibitor, L-28 may contribute to the inhibition of viability in the different lung cancer cell lines. Treatment of cells with L-28 for 24 hours resulted in a significant concentration-dependent decrease in cell viability compared with untreated cells (Figure 2C). The EC50 for L-28 against the two cancer cell lines were 8.5 μM (3.0 μg/ml) for A549 and 28 μM (9.6 μg/ml) for H460 compared to > 200 μM (70 μg/ml) for the normal WI-38 cells. Moreover, L-28 inhibited intracellular PMPMEase activity in all the cell lines. However, the inhibition was relatively higher in the cancer cells (IC50 values of 2.5 μM or 0.88 μg/ml for A549 and 41 μM or 14 μg/ml for H460) compared to 520 μM (180 μg/ml) for the normal WI-38 cells (Figure 2D). When the effect of PMPMEase inhibition on cell proliferation was determined, L-28 significantly inhibited the proliferation of both A549 (Figure 3A) and H460 cells (Figure 3B). In order to better understand the long term effect of PMPMEase inhibition on cancer cell viability, cells previously exposed to varying concentrations of L-28 for 72 h were further cultured for 48 h. Withdrawal of treatment with L-28 did not result in renewed increases in cell viability (Figure 3C). A clonogenic assay was used to assess the differences in reproductive viability between human lung cancer cells treated with L-28 and untreated control cells. The clonogenic deaths of A549 and H460 cells after incubation with either 5 or 10 μM of L-28 at 37°C are shown in Figure 3D. Treatment with either 5 or 10 μM of L-28 for 72 h reduced the clonogenic survival of A549 cells to about 43.4% and 15.5%, and H460 cells to about 13.5% and 0.2%, respectively. These results indicate that the lung cancer cells exposed to PMPMEase inhibitors are unlikely to recover from the degeneration effects.

Figure 2.

PMPMEase is overexpressed and is hyperactive in lung cancer cells. A. Cultured human lung fibroblasts (WI-38) cells, alveolar adenocarcinoma (A549) cells and non-small cell carcinoma (H460) cells were lysed and assayed for PMPMEase activity using RD-PNB as substrate. The specific activities are expressed as the amount of product formed/h/mg of total protein ± SEM of triplicate determinations. B. Western blot analysis of whole cell lysates showing relative expressions of PMPMEase and GAPDH in normal and lung cancer cells under normal cell culture conditions. C. Cells were treated with varying concentrations of L-28 for 24 h as described in the methods. The viability of the treated cells was determined by fluorescence using the resazurin reduction assay. The results are expressed as the means (± SEM, N = 4) relative to the controls. D. Aliquots of cell lysates were assayed for PMPMEase activity after 3 h incubation at 37°C using RD-PNB as the substrate in the presence of L-28.

Figure 3.

L-28 inhibits lung cancer cell proliferation. Cultured human lung cancer (A) A549 and (B) H460 cells were treated with varying concentrations of L-28 for 72 h as described in the methods. Cell viability was determined before the initial treatment and then after the final treatment by fluorescence using the resazurin reduction assay. Cell proliferation was calculated as the difference in cell viability between the initial and final readings. (C) L-28 induces irreversible lung cancer cell degeneration. Cultured human lung cancer (A549 and H460) cells were treated with varying concentrations of L-28 for 72 h as described in the methods. The treatment medium was replaced with normal growth medium and cultured for a further 48 h. The cell viability was determined by fluorescence using the resazurin reduction assay. The results are expressed as the means (± SEM, N = 4) relative to the controls. (D)Clonogenic cell death caused by L-28. Exponentially growing cells in culture were treated with L-28 (5 or 10 μM) for 72 h, washed, cultured for a further 7 days at 37°C, and clonogenic survival was determined. The results are expressed as the means (± SEM, N = 4) relative to the controls. Significance (***p < 0.001) was determined by Student’s t-test.

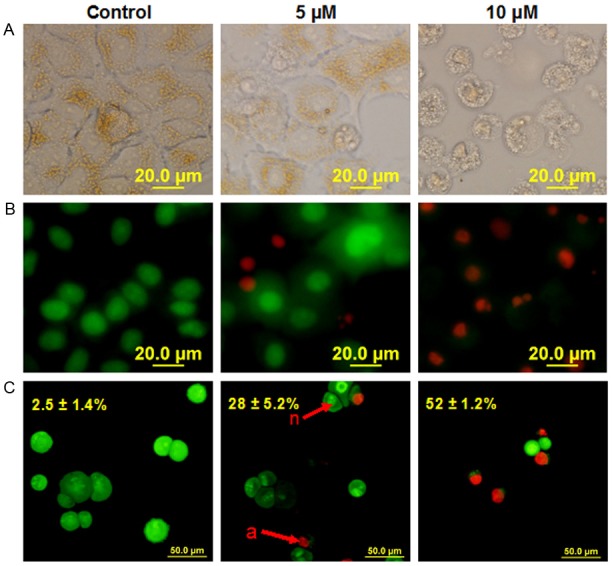

The AO/EB method was used to determine the mode of L-28-induced cytotoxicity as previously described [31,38]. Fluorescence light microscopy coupled with the differential uptake of the fluorescent DNA-binding dyes, EB and AO, was used for its simplicity, rapidity, and accuracy [38]. AO permeated the live control cells as well as cells exposed to lower concentrations of L-28 turning their nuclei green. Cells treated with L-28 fluoresced red due to EB uptake following the loss of cytoplasmic membrane integrity. L-28 induced apoptosis in a concentration dependent manner as depicted in Figure 4. Taken together, these results indicate that higher levels of PMPMEase likely contribute to lung cancer progression thereby making PMPMEase a viable target for anticancer drug development.

Figure 4.

L-28 induces apoptosis of human lung cancer A549 cells. Cells were treated with L-28 (5 and 10 μM) for 48 h and stained with acridine orange and ethidium bromide (AO/EB, 10 μg/ml) as described in the methods. When stained with AO/EB, live cells with normal nuclei (n) appear green; apoptotic cells (a) with condensed or fragmented chromatin in the nuclei appear orange. A. Shows pictures of cells taken with bright field focus. B. Indicates AO/EB overlay pictures obtained from the simplified morphological observation. C. Shows quantification of apoptotic A549 cells (shown as percentages) using the conventional method of staining.

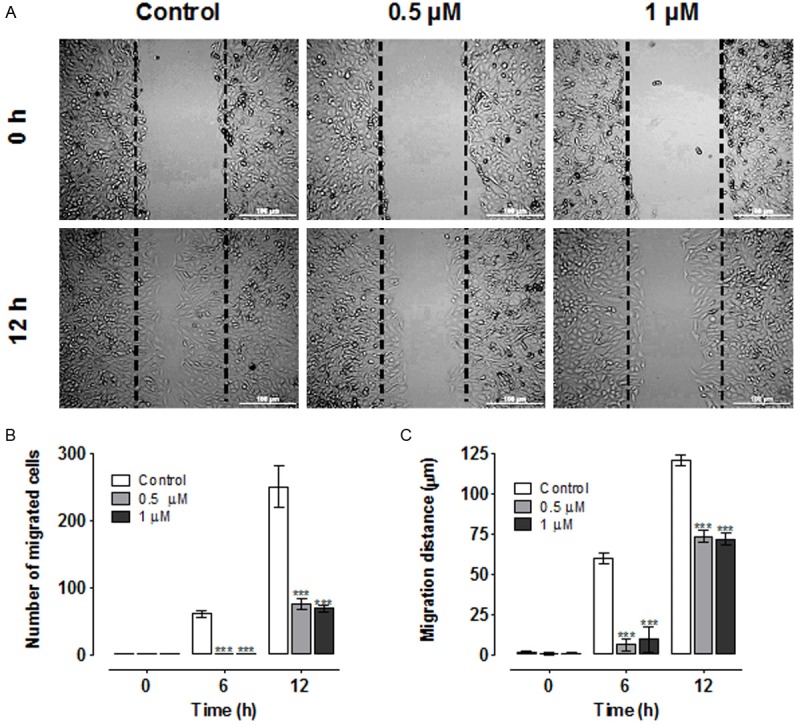

PMPMEase inhibition attenuates cell migration

To examine the effect of L-28 on lung cancer A549 cell migration, we employed the widely used wound-healing assay [42] to characterize the cell migration response in A549 cells. The number of cells involved in the wound sealing as well as the mean distance of migration were evaluated after 6 h and 12 h. Control untreated A549 cells migrated into the wound area faster, reaching 40% and 85% sealing at 6 and 12 h after wound scratch, respectively (Figure 5A and 5B). The number of cells in the control that migrated into the wound area after 6 and 12 h were 61 ± 5.0 and 250 ± 31, respectively. Treatment of A549 cells with 0.5 μM of L-28 significantly decreased the number of cells that differentiamigrated into the wound area to 1.3 ± 0.3 and 75 ± 9.0 after 6 and 12 h, respectively (p < 0.001). A further decrease in the number of migrated cells was observed with 1.0 μM of L-28 treatment (1.0 ± 0.5 and 69 ± 5.0) after 6 and 12 h, respectively (p < 0.001). The rate of migration as indicated by migration distance was also significantly inhibited by L-28 compared with that of control untreated cells at each of the time points examined (Figure 5A and 5C). L-28 significantly decreased the distance of migration into the wound area from 120.6 ± 3.1 μm (control) to 73.5 ± 3.5 μm (0.5 μM) and 71.7 ± 3.7 μm (1 μM), respectively after 12 h (p < 0.001). These results indicate that inhibition of PMPMEase inhibits wound-induced cell migration.

Figure 5.

Wound healing and cell migration assays. A. Cell motility in wound healing assay. A uniform scratch was made in 90% confluent monolayer culture of A549 cells and the extent of closure was monitored under microscope and photographed. Representative images of three independent experiments done in duplicate are shown. Results of three independent experiments were plotted. Migrating cells within the scratch were quantified and the distance of migration measured using NIH ImageJ software (n = 3 individual experiments). B. Treatment with L-28 (0.5 μM and 1 μM) significantly inhibited the number of migrated cells compared with the control solvent-treated cells. C. Over the same incubation time, the cells in the control groups migrated farther, achieving a complete or near closure of the wounds. The results are expressed as the means (± SEM, N = 5) relative to the controls. Significance (***p < 0.001) was determined by Student’s t-test.

PMPMEase inhibition disrupts actin cytoskeleton organization

Polyisoprenylated monomeric G-proteins such as Ras and Rho family of G proteins play important roles in regulating migration, differentiation, survival and proliferation [43]. We determined whether PMPMEase inhibition by L-28 affects actin cytoskeleton organization which plays a vital role in cell shape, adhesion and migration [44]. We also aimed to determine the effect of PMPMEase inhibition on the cellular localization of PMPMEase, N-Ras, K-Ras, and H-Ras in A549 cells. Treatment of cells with PMPMEase inhibitor did not appear to alter neither the levels nor the distribution of PMPMEase as well as N-Ras, K-Ras and H-Ras in the A549 cells (Figure 6). This is consistent with the expression levels of the different genes coding for Ras proteins observed with the nanostring studies which were neither downregulated nor upregulated. However, F-actin organization was notably disrupted by L-28. When control untreated cells were stained with DAPI and flourescein-conjugated phalloidin, the cells revealed only a fine polymerized filamentous actin with centrally located nuclei (Figure 6). Prominent perinuclear and well organized F-actin filaments were observed. However, treatment with L-28 resulted in altered formation and distribution of F-actin in cells (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Immunofluorescence analysis of PMPMEase inhibition on F-actin filaments and cellular localization of PMPMEase and Ras proteins. Cells treated with L-28 (0-10 μM) were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 as described in methods. These were then probed with FITC-labeled antisera directed against PMPMEase (P), H-Ras (H), N-Ras (NR), K-Ras (K) or RhoA (R). Cell nuclei (N) were labeled either with propidium iodide (red) or DAPI (blue). F-actin filaments (F) were stained green with fluorescein-conjugated phalloidin. Fluorescent images were captured using a fluorescent microscope equipped with propidium iodide and fluorescein band pass filters and an Olympus DP70 camera.

PMPMEase inhibition alters the expression of cancer-related genes in H460 and A549 cells

To further understand the anticancer potential of PMPMEase inhibition, we profiled the expression of a broad panel of inducible cancer-related genes using RNA profiling technology that employs molecularly bar-coded fluorescent probes (nCounter, NanoString). We found that treatment with 2 and 5 μM of L-28 altered the expression of several genes in both A549 and H460 lung cancer cell lines. When the results for the 5 μM of L-28 treatment was used in the subsequent analysis and a fold change of ≤ -1.5 or ≥ 1.5 were considered significant, 86 genes were affected in the A549 cells while in the H460 cells, 79 genes were altered. The expression patterns of a total of 47 genes were similarly altered in both A549 and H460 cell lines, (Figure 7A). This subset of genes were further grouped, based on their principal functions, into (1) DNA repair/transcription, (2) cell cycle regulation, (3) cell growth, proliferation, differentiation and survival, (4) cell adhesion and migration and (5) immune response (Figure 7B). In general, L-28 robustly activated the expression of pro-apoptotic and cell cycle arrest genes (BCL6, CDKN1A, IGFBP3, MLL, ETS1, TGFBI, TNFRSF10B, RARA, SIAH1, and CEBPA), while anti-apoptotic genes as well as genes promoting cell proliferation (BIRC5, CDC2, E2F1, PCNA, MYBL2, CCNA2 and CCND3) were downregulated. Notably, the expression of the transcription factor and cell cycle progression gene, MYBL2 was severely suppressed in both H460 and A549 cell lines. The death receptor genes, TNFRSF10B and PPARG were both upregulated. Also, genes involved in lung development (CTNNB1, PDGFA, PTHLH and FGF2) were upregulated whilst CTGF was downregulated by L-28 treatment. In addition, L-28 induced the upregulation of genes for the growth factors, FGF2, MET, AREG, IGFBP3, and EGFR, as well as their receptors. Genes involved in integrin signaling were either upregulated (LICAM, ITGB1 and PLAUR) or downregulated (CTGF). L-28 treatment induced the upregulation of CTNNB1, CD44, MET and CDKN1A. Moreover, genes that either code for ligands (AREG, FGF2, MET, IL6, L1F), receptors (EGFR, PLAUR) and downstream signaling mediators (BRAF, EPS8) in receptor tyrosine kinase pathways were upregulated. These data suggest that the observed effects of L-28 on the cells involve significant changes that impact signaling pathways involved in cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis survival, adhesion and migration.

Figure 7.

nCounter analysis of the effect of L-28 on cancer-related genes in A549 and H460 cells. Cells were treated with L-28 (2 μM and 5 μM) for 72 h. Isolated RNA was purified and subjected to nCounter measurements for transcripts of cancer-related genes. Data were normalized based on seven house-keeping genes showing stable expression levels in both cell lines. Genes with fold changes of ≥ 3 or ≤ 3 are shown. For these differentially regulated genes, their fold change values in the treated cells versus control conditions were obtained. A. Heat map of the fold change in gene expression values are shown. MultiExperimentViewer (MeV v4.6.2) was used for hierarchical clustering by average linkage clustering based on Manhattan distance (red indicates upregulated genes; green indicates downregulated genes). B. Bar graph of fold change in expression values of selected genes.

PMPMEase is overexpressed in lung cancer

The results showing that PMPMEase activities and protein levels are higher in lung cancer versus normal cells and the observation that PMPMEase inhibition in these cells induces apoptosis and the altered expression of cancer-related genes led us to examine TMAs consisting of various lung cancer tissues and normal lung tissues for the relative expression of PMPMEase. The demographic and histopathological characteristics of the tissues donors for the TMAs are shown in Table 1. The ages of the patients ranged from 27 to 77 years and most (76.25%) were males. As shown in Table 1, there were 416 total cases out of which 16 were normal tissues and 21 were SCLC. The NSCLC tumors comprised 204 squamous cell carcinomas (SCC), 109 adenocarcinomas (AC), 21 papillary adenocarcinomas (PAC), 21 adenosquamous carcinomas (ASC), 8 bronchioloalveolar carcinomas (BAC), 5 large-cell carcinomas (LCC) and 11 other tumors. In general, all the lung cancers showed intense intracellular PMPMEase immunoreactivity. Figure 8 shows representative images of normal lung and lung cancer tissues. The data indicate that increasing levels of PMPMEase expression are associated with tumors (Figure 8I). We observed predominantly peri-nuclear cytoplasmic staining indicative of PMPMEase protein expression in the lung cells (Figure 8II) consistent with the endoplasmic reticulum localization of the enzyme [28,45]. In the control cores consisting of normal lung tissues, staining was present in a few normal bronchial and glandular epithelial cells. However, in general, only trace to weak immunostaining was observed in the normal lung tissues. Solid tumors with deeply stained epithelial cells were displayed especially in most of the SCC, ASC, BAC, AC and PAC. Scattered patterns of staining were observed among the LCC and the SCLC tumor cells, with positive areas spread out throughout the cores. Significant differences in PMPMEase immunoreactivity intensities between the normal tissues and the different lung tumor categories were observed when the stained sections were analyzed (p = 0.0002 - < 0.0001) (Table 2). The mean scores ± SEM were 118.8 ± 7.7 (normal), 232.1 ± 25.1 (small-cell lung carcinomas), 352.1 ± 9.4 (squamous cell carcinomas), 311.7 ± 9.8 (adenocarcinomas), 350.0 ± 24.2 (papillary adenocarcinomas), 334.7 ± 30.1 (adenosquamous carcinomas), 321.9 ± 39.7 (bronchioloalveolar carcinomas), and 331.3 ± 85.0 (large-cell carcinomas). Very high PMPMEase expression (score = 401-500) were observed in 43.1% of SCC. The mean PMPMEase immunoreactivity score was significantly high even at early-stage (stages I and II) lesions, with progressively increasing staining intensities (Figure 8, Table 2). Although no specific trend was observed when the data were analyzed according to pathological stages, grades, tumor size, nodal status and metastases, there were significant differences when compared to the normal tissues regardless of the parameter under consideration.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical and histopathological characteristics of the 416 donors of the lung tissues used in the tissue microarray studies

| Characteristics | Patients | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| n | (%) | ||

| Age | ≤ 65 years | 326 | 78.4 |

| > 65 years | 90 | 21.6 | |

| Sex | Female | 102 | 24.5 |

| Male | 314 | 75.5 | |

| Histology | Normal | 16 | 3.8 |

| Small cell lung carcinomas | 21 | 5.0 | |

| Non-small cell lung carcinomas | |||

| Squamous cell carcinomas | 204 | 49.0 | |

| Adenocarcinomas | 109 | 26.2 | |

| Papillary adenocarcinoma | 21 | 5.0 | |

| Adenosquamous carcinomas | 21 | 5.0 | |

| Bronchioloalveolar carcinomas | 8 | 1.9 | |

| Large-cell carcinomas | 5 | 1.3 | |

| Others | 11 | 1.2 | |

| Grade | 1 | 25 | 6.0 |

| 2 | 228 | 54.8 | |

| 3 | 58 | 13.9 | |

| Not determined | 89 | 21.4 | |

| Pathological stage | I | 223 | 53.6 |

| II | 77 | 18.5 | |

| IIIa | 38 | 9.1 | |

| IIIb | 48 | 11.5 | |

| IV | 4 | 1.0 | |

| Tumor status | 1 | 17 | 4.1 |

| 2 | 304 | 73.1 | |

| 3 | 30 | 7.2 | |

| 4 | 49 | 11.8 | |

| Nodal status | 0 | 270 | 64.9 |

| 1 | 105 | 25.2 | |

| 2 | 22 | 5.2 | |

| 3 | 2 | 0.5 | |

| Metastasis | 0 | 396 | 95.2 |

| 1 | 4 | 1.0 | |

Figure 8.

Analysis of lung cancer tissue microarrays cores for PMPMEase immunoreactivity. Lung TMAs consisting of 416 cores from 416 distinct cases were subjected to immunohistochemical analysis using a PMPMEase polyclonal antibody specific for PMPMEase protein. (I) Relatively high scores were observed in lung squamous cell carcinoma (stage I, A2-A4; stage IIa, A5; stage IIIb, A6), lung adenosquamous carcinoma (stage I, B1; stage II, B2; stage IIIb, B3), adenocarcinoma (stage I, B1; stage IIa, B5; stage IIIb, B6), papillary adenocarcinoma (stage I, C1 and C2), small cell lung carcinoma (stage I, C4; stage II, C4; stage IIIa, C5), large cell lung carcinoma (stage I, C6; stage IIIa, D2; stage IIIb, D3), bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (stage I, D4 and D5) and mucinous bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (stage I, D6). (A1 and F1) are images of sections obtained from normal lung tissues. (II) Representative sections of normal lung tissue (A1), lung squamous cell carcinoma (A2 and A3), lung adenosquamous carcinoma (A4), adenocarcinoma (B1 and B2), papillary adenocarcinoma (B3 and B4), small cell lung carcinoma (C1 and C2), bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (C3) and mucinous bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (C4) slices showing the brown staining indicative of PMPMEase. Areas with dense populations of blue-stained nuclei indicative of tumor cells also show a higher intensity of brown staining for PMPMEase. Each image represents a different case.

Table 2.

Association of PMPMEase immunoreactivity with the pathologic features of lung cancer

| Characteristics | PMPMEase Staining Intensity, N (%) | p-value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| 1-100 Trace | 101-200 Weak | 201-300 Intermediate | 301-400 Strong | 401-500 Very strong | Missing | Mean Scores | ||

| Histology | ||||||||

| Normal | 9 (56.2) | 7 (43.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 118.8 ± 7.7 | 0.0001 |

| Small cell lung carcinomas | 3 (14.3) | 7 (33.3) | 7 (33.3) | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | 0 | 232.1 ± 25.1 | |

| Non-small cell lung carcinomas | ||||||||

| Squamous cell carcinomas | 9 (4.4) | 32 (15.7) | 36 (17.6) | 36 (17.6) | 88 (43.1) | 3 (1.5) | 352.1 ± 9.4 | |

| Adenocarcinomas | 4 (3.7) | 14 (12.8) | 34 (31.2) | 37 (33.9) | 18 (16.5) | 2 (1.8) | 311.7 ± 9.8 | |

| Papillary adenocarcinoma | 0 | 3 (14.3) | 5 (23.8) | 7 (33.3) | 6 (28.6) | 0 | 350.0 ± 24.2 | |

| Adenosquamous carcinomas | 1 (4.7) | 2 (9.5) | 6 (28.6) | 3 (14.3) | 6 (28.6) | 3 (14.3) | 334.7 ± 30.1 | |

| Bronchioloalveolar carcinomas | 0 | 2 (25.0) | 0 | 5 (62.5) | 1 (12.5) | 0 | 321.9 ± 39.7 | |

| Large-cell carcinomas | 0 | 1 (20.0) | 1 (20.0) | 0 | 2 (40.0) | 1 (20.0) | 331.3 ± 85.0 | |

| Others | 2 (18.2) | 4 (36.4) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (18.2) | 2 (18.2) | 0 | 238.3 ± 43.0 | |

| Pathological stage | ||||||||

| Normal | 9 (56.2) | 7 (43.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 118.8 ± 7.7 | 0.0001 |

| I | 12 (5.1) | 34 (14.3) | 55 (23.2) | 58 (24.5) | 73 (30.8) | 5 (2.1) | 334.2 ± 8.3 | |

| II | 4 (5.3) | 14 (18.7) | 19 (25.3) | 18 (24.0) | 17 (22.7) | 3 (4.0) | 305.0 ± 14.0 | |

| IIIa | 2 (5.3) | 7 (18.4) | 5 (13.2) | 8 (21.1) | 15 (39.5) | 1 (2.6) | 342.6 ± 22.5 | |

| IIIb | 1 (2.1) | 9 (19.1) | 11 (23.4) | 8 (17.0) | 18 (38.3) | 0 | 333.0 ± 17.8 | |

| IV | 0 | 1 (25.0) | 1 (25.0) | 0 | 2 (50.0) | 0 | 325.0 ± 89.0 | |

| Grade | ||||||||

| Normal | 9 (56.2) | 7 (43.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 118.8 ± 7.7 | 0.0001 |

| 1 | 0 | 6 (24.0) | 5 (20.0) | 3 (12.0) | 11 (44.0) | 0 | 333.0 ± 27.2 | |

| 2 | 9 (3.9) | 31 (13.6) | 46 (20.2) | 56 (24.6) | 86 (37.7) | 1 (0.4) | 348.8 ± 8.0 | |

| 3 | 3 (5.4) | 7 (12.5) | 19 (33.9) | 17 (30.4) | 10 (17.9) | 0 | 312.9 ± 15.0 | |

| Not determined | 7 (7.9) | 20 (22.5) | 19 (21.3) | 16 (18.0) | 19 (21.3) | 8 (9.0) | 262.9 ± 13.9 | |

| Tumor size | ||||||||

| Normal | 9 (56.2) | 7 (43.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 118.8 ± 7.7 | 0.0001 |

| 1 | 0 | 2 (11.8) | 4 (23.5) | 6 (35.3) | 4 (23.5) | 1 (5.9) | 340.6 ± 26.4 | |

| 2 | 14 (4.7) | 48 (16.2) | 67 (22.6) | 69 (23.2) | 91 (30.1) | 8 (2.7) | 330.3 ± 7.5 | |

| 3 | 3 (10.1) | 5 (17.2) | 4 (13.8) | 6 (20.7) | 10 (34.5) | 0 | 319.0 ± 27.1 | |

| 4 | 1 (2.1) | 8 (17.0) | 11 (23.4) | 8 (17.0) | 19 (40.4) | 0 | 337.8 ± 18.1 | |

| Nodal status | 9 (56.2) | 7 (43.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 118.8 ± 7.7 | 0.0001 |

| 0 | 13 (4.7) | 40 (14.7) | 60 (22.0) | 66 (24.2) | 89 (32.6) | 5 (1.8) | 336.3 ± 7.7 | |

| 1 | 5 (4.8) | 19 (18.1) | 25 (23.8) | 23 (21.9) | 30 (28.6) | 3 (2.9) | 317.2 ± 12.7 | |

| 2 | 1 (5.0) | 6 (30.0) | 3 (15.0) | 2 (10.0) | 7 (35.0) | 1 (5.0) | 309.2 ± 32.7 | |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 (50.0) | 0 | 1 (50.0) | 0 | 362.5 ± 62.5 | |

| Metastasis | ||||||||

| Normal | 9 (56.2) | 7 (43.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 118.8 ± 7.7 | 0.0001 |

| 0 | 19 (4.9) | 64 (16.5) | 89 (23.0) | 92 (23.8) | 123 (31.8) | 9 (2.4) | 329.7 ± 6.4 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 (25.0) | 1 (25.0) | 0 | 2 (50.0) | 0 | 325.0 ± 89.6 | |

Significantly higher PMPMEase immunoreactivities were observed in the different types, grades, stages, sizes, nodal invasion and metastasis of lung cancers as shown by the means ± SEM versus normal tissues compared by ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s posttest.

Discussion

Previous studies revealed the death of cancer cells treated with polyisoprenylated small molecule inhibitors of PMPMEase [30] or PUFAs [32]. Despite this apparent dependency of cancer cell viability on PMPMEase activity, the possible role of PMPMEase in cancer progression has not received similar research attention as the other polyisoprenylation pathway enzymes. In addition, polyisoprenylated proteins are involved in a wide array of intracellular signaling functions that influence cell proliferation, differentiation, cytoskeleton organization and vesic-ular trafficking, all of which are associated with various aspects of cancer biology [14,44,46-48]. PMPMEase may indeed play a critical regulatory role in polyisoprenylated protein function due to its ability to create a negatively charged carboxylate ion with the propensity to induce conformational changes near the polyisoprenyl moiety that is critical for protein-protein interactions [46]. That PMPMEase expression and activity is important for cell growth was suggested by previous work from this laboratory in which PMPMEase inhibition induced cancer cell death [30,31,41]. Cushman et al., using a knockdown approach in a recent study identified CES 1 (PMPMEase), as a specific esterase whose function is important for the methylation status as well as activation of RhoA and cell morphology. The elevated PMPMEase activity and expression in the lung cancer cells compared to the normal lung fibroblasts suggests that overexpression of PMPMEase may indeed spur cell growth.

This study shows that PMPMEase inhibition is associated with decrease in cell viability through the induction of apoptosis and the inhibition of cell proliferation and survival. These were further confirmed by the gene expression studies that revealed the downregulation of anti-apoptotic genes as well as the upregulation of pro-apototic and death receptor pathway and cell cycle arrest genes. TNFRSF10B can be activated by the tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand, TNFSF10/TRAIL/APO-2L, and mediates in apoptosis signal transduction. Downregulation of DNA repair genes such as TYMS and TOP2A through inhibition of PMPMEase activity indicates the dysregulation of DNA damage response. Since DNA damage response is essential to genomic integrity and prevention of carcinogenesis [49], failure to repair DNA damage can lead to genomic instability and cell death that enhances chemotherapy benefit. A large body of evidence from pre-clinical and clinical studies indicates that BRCA1 is central to DNA damage repair response [50]. It is therefore not surprising to observe that its downregulation in the current study is associated with loss of cell viability. Moreover, since cell cycle checkpoints are essential for maintaining genomic integrity, the observation that cell cycle arrest genes are upregulated while cell cycle progression genes are downregulated is consistent with the observed effects of PMPMEase inhibition on cell viability.

In addition to harboring K-RAS mutations, A549 cells are known to express activated EGFR as a result of constitutive upregulation of EGFR ligands, particularly AREG, which together play important roles in the pathogenesis of lung cancer. EGFR signaling pathways play pertinent roles in evading apoptosis and promoting survival which are the hallmarks of cancer cells [51]. The key signaling pathways initiated by EGFR through its Grb2/Sos1 associations involve Ras proteins which then stimulates the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Ras activation is subsequently involved in cell growth, proliferation, motility, survival and transformation [52]. Experimental and clinical evidence indicates that overexpression or mutation of EGFR mediates tumor resistance to both chemotherapy and especially radiotherapy [53]. Upregulation of trophic factors and their signaling mediators in the current study likely indicates a feedback survival effort due to impaired downstream mediator(s). Although RAS genes, as well as Ras protein localization, were not significantly altered, inhibition of PMPMEase likely affected the methylated/demethylated ratios the proteins, impacting their conformations and altering their interactions with downstream mediators in the signaling pathway.

Inhibition of PMPMEase was also associated with significant disruption of F-actin organization as well as inhibition of cell motility. These may be attributed to defective processing of polyisoprenylated Rho family of small GTPases such as Rac1, RhoA and Cdc42 that control the dynamics of actin cytoskeleton [44]. The gene expression study also revealed changes in the expression of some pertinent genes (FGF2, MET, PLAUR, ITGB1 and TGFB1) necessary for chemotaxis, receptors signaling, cell adhesion and migration upon treatment of the cells with L-28. Genes such as CTNNB1, MET, CDKN1A and CD44 are associated with β-catennin, which is located at cell-cell adherens junction where it links cadherens to actin cytoskeleton [54,55]. Also, the expression of genes such as CTGF, LICAM, ITGB1 and PLAUR which are associated with integrin and its signaling, were affected. Integrin regulates cytoskeleton organization necessary for cell polarity, migration, proliferation [54]. Integrins also function as transmembrane linkers to the cytoskeleton required for the cells to grip the extracellular matrix [54]. These changes are therefore consistent with the observed inhibition of cell migration due to PMPMEase inhibition.

Tissue microarrays continue to play a prominent role in the identification of disease biomarkers and validation of putative therapeutic targets [56,57]. Positive PMPMEase immunoreactivity in various types of lung cancer strongly suggests that PMPMEase hyperactivity may play crucial roles in cancer etiology and/or progression. This finding is in strong agreement not only with studies showing the cancer cell death associated with PMPMEase inhibition but also the well documented roles that aberrant polyisoprenylated protein function plays in carcinogenicity [16,18] and cell migration [14,48]. Taken together, it can be concluded that PMPMEase is overexpressed in lung cancer where its hyperactivity likely spurs cancer cell growth. Therefore, the enzyme assay and/or protein immunodetection methods could be developed to serve in the diagnosis or companion diagnosis of lung cancer. The enzyme may further serve as a target for the development of a novel class of drugs to combat lung cancer. L-28, a polyisoprenylated small molecule inhibitor of PMPMEase was shown to irreversibly inhibit isolated PMPMEase activity as well as activities in cultured cancer cells resulting in cell death [30]. Our current results show that L-28 has the potential to inhibit lung cancer cell viability through inhibition of PMPMEase activity.

This and previous studies suggest that PMPMEase activity likely plays a vital role not only in cancers but also in degenerative disorders. Experimental conditions which favor polyisoprenylated protein methylation induce Parkinson disease-like effects in animals [58,59]. Inhibition of PMPMEase by pesticides [59] and PUFAs may replicate a hypermethylation scenario and cell apoptosis observed with specific PMPMEase inhibition [30]. Although some pesticides [59,60] but not PUFAs have been implicated in human Parkinsonism, both classes of compounds may constitute environmental and endogenous risk factors for Parkinson’s disease. Aberrant geranylgeranyl transferase leading to defective polyisoprenylated proteins accounts for the macular degeneration observed in choroideremia [61]. These demonstrate that while targeted inhibition of PMPMEase may hold promise in the control of cell proliferation in lung cancer, the degree of enzyme inhibition must be carefully determined to avoid the detrimental consequences that may result from excessive inhibition.

Conclusion

In summary, PMPMEase activity and expression is elevated in lung cancer. Inhibition of PMPMEase activity induces lung cancer cell apoptosis. This makes it a suitable biomarker that can be developed into a procedure for the early/companion diagnosis of lung cancer. Potent and specific inhibitors of PMPMEase could eventually be developed as a new class of targeted therapies for breast cancer.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health through Grant Number 8 G12 MD007582-28 and 2 G12 RR003020.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boffetta P, Nyberg F. Contribution of environmental factors to cancer risk. Br Med Bull. 2003;68:71–94. doi: 10.1093/bmp/ldg023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2011. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Traynor AM, Schiller JH. Systemic treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Drugs Today (Barc) 2004;40:697–710. doi: 10.1358/dot.2004.40.8.850472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Travis WD, Rekhtman N. Pathological diagnosis and classification of lung cancer in small biopsies and cytology: strategic management of tissue for molecular testing. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;32:22–31. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1272866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganti AK, Huang CH, Klein MA, Keefe S, Kelley MJ. Lung cancer management in 2010. Oncology (Williston Park) 2011;25:64–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siegel R, Ward E, Brawley O, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2011: the impact of eliminating socioeconomic and racial disparities on premature cancer deaths. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:212–236. doi: 10.3322/caac.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schubbert S, Shannon K, Bollag G. Hyperactive Ras in developmental disorders and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:295–308. doi: 10.1038/nrc2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sebti SM. Protein farnesylation: implications for normal physiology, malignant transformation, and cancer therapy. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:297–300. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McTaggart SJ. Isoprenylated proteins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:255–267. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5298-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winter-Vann AM, Casey PJ. Post-prenylation- processing enzymes as new targets in oncogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:405–412. doi: 10.1038/nrc1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bifulco M. Role of the isoprenoid pathway in ras transforming activity, cytoskeleton organization, cell proliferation and apoptosis. Life Sci. 2005;77:1740–1749. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flotho C, Kratz C, Niemeyer CM. Targeting RAS signaling pathways in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Curr Drug Targets. 2007;8:715–725. doi: 10.2174/138945007780830773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mills NE, Fishman CL, Scholes J, Anderson SE, Rom WN, Jacobson DR. Detection of K-ras oncogene mutations in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid for lung cancer diagnosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1056–1060. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.14.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ridanpaa M, Karjalainen A, Anttila S, Vainio H, Husgafvelpursiainen K. Genetic alterations in p53 and k-ras in lung-cancer in relation to histopathology of the tumor and smoking history of the patient. Int J Oncol. 1994;5:1109–1117. doi: 10.3892/ijo.5.5.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodenhuis S, Slebos RJ. Clinical significance of ras oncogene activation in human lung cancer. Cancer Res. 1992;52:2665s–2669s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clarke S, Vogel JP, Deschenes RJ, Stock J. Posttranslational modification of the Ha-ras oncogene protein: evidence for a third class of protein carboxyl methyltransferases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:4643–4647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghobrial IM, Adjei AA. Inhibitors of the ras oncogene as therapeutic targets. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2002;16:1065–1088. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(02)00050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wiemer AJ, Hohl RJ, Wiemer DF. The intermediate enzymes of isoprenoid metabolism as anticancer targets. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2009;9:526–542. doi: 10.2174/187152009788451860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazieres J, Pradines A, Favre G. Perspectives on farnesyl transferase inhibitors in cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2004;206:159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2003.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agrawal AG, Somani RR. Farnesyltransferase inhibitor as anticancer agent. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2009;9:638–652. doi: 10.2174/138955709788452702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kloog Y, Zatz M, Rivnay B, Dudley PA, Markey SP. Nonpolar lipid methylation-identification of nonpolar methylated products synthesized by rat basophilic leukemia cells, retina and parotid. Biochem Pharmacol. 1982;31:753–759. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(82)90459-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen HX, Cleck JN, Coelho R, Dancey JE. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors: current status and future directions. Curr Probl Cancer. 2009;33:245–294. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gupta R, Dastane AM, Forozan F, Riley-Portuguez A, Chung F, Lopategui J, Marchevsky AM. Evaluation of EGFR abnormalities in patients with pulmonary adenocarcinoma: the need to test neoplasms with more than one method. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:128–133. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Casey PJ. Biochemistry of protein prenylation. J Lipid Res. 1992;33:1731–1740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oboh OT, Lamango NS. Liver prenylated methylated protein methyl esterase is the same enzyme as Sus scrofa carboxylesterase. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2008;22:51–62. doi: 10.1002/jbt.20214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lamango NS, Duverna R, Zhang W, Ablordeppey SY. Porcine Liver Carboxylesterase Requires Polyisoprenylation for High Affinity Binding to Cysteinyl Substrates. Open Enzym Inhib J. 2009;2:12–27. doi: 10.2174/1874940200902010012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aguilar B, Amissah F, Duverna R, Lamango NS. Polyisoprenylation potentiates the inhibition of polyisoprenylated methylated protein methyl esterase and the cell degenerative effects of sulfonyl fluorides. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2011;11:752–762. doi: 10.2174/156800911796191015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amissah F, Poku RA, Aguilar BJ, Duverna R, Abonyo BO, Lamango NS. Polyisoprenylated Methylated Protein Methylesterase: The Fulcrum of Chemopreventive Effects of NSAIDs and PUFAs. Nova Science Publishers; 2013. pp. 119–144. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amissah F, Taylor S, Duverna R, Ayuk-Takem LT, Lamango NS. Regulation of polyisoprenylated methylated protein methyl esterase by polyunsaturated fatty acids and prostaglandins. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol. 2011;113:1321–1331. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.201100030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Half E, Tang XM, Gwyn K, Sahin A, Wathen K, Sinicrope FA. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human breast cancers and adjacent ductal carcinoma in situ. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1676–1681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim YB, Kim GE, Cho NH, Pyo HR, Shim SJ, Chang SK, Park HC, Suh CO, Park TK, Kim BS. Overexpression of cyclooxygenase-2 is associated with a poor prognosis in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix treated with radiation and concurrent chemotherapy. Cancer. 2002;95:531–539. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moyad MA. An introduction to dietary/supplemental omega-3 fatty acids for general health and prevention: part I. Urol Oncol. 2005;23:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rayyan Y, Williams J, Rigas B. The role of NSAIDs in the prevention of colon cancer. Cancer Invest. 2002;20:1002–1011. doi: 10.1081/cnv-120005917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cushman I, Cushman SM, Potter PM, Casey PJ. Control of RhoA Methylation by Carboxylesterase I. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:19177–19183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.467407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ribble D, Goldstein NB, Norris DA, Shellman YG. A simple technique for quantifying apoptosis in 96-well plates. BMC Biotechnol. 2005;5:12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-5-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen JJ. Apoptosis. Immunol Today. 1993;14:126–130. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90214-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jeselsohn RM, Werner L, Regan MM, Fatima A, Gilmore L, Collins LC, Beck AH, Bailey ST, He HH, Buchwalter G, Brown M, Iglehart JD, Richardson A, Come SE. Digital quantification of gene expression in sequential breast cancer biopsies reveals activation of an immune response. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amissah F, Duverna R, Aguilar BJ, Poku RA, Lamango NS. Polyisoprenylated methylated protein methyl esterase is both sensitive to curcumin and overexpressed in colorectal cancer: implications for chemoprevention and treatment. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:416534. doi: 10.1155/2013/416534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liang CC, Park AY, Guan JL. In vitro scratch assay: a convenient and inexpensive method for analysis of cell migration in vitro. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:329–333. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adjei AA. Blocking oncogenic Ras signaling for cancer therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1062–1074. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.14.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hall A. Rho GTPases and the actin cytoskeleton. Science. 1998;279:509–514. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Munro S, Pelham HR. A C-terminal signal prevents secretion of luminal ER proteins. Cell. 1987;48:899–907. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90086-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boguski MS, McCormick F. Proteins regulating Ras and its relatives. Nature. 1993;366:643–654. doi: 10.1038/366643a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bourne HR, Sanders DA, McCormick F. The GTPase superfamily: a conserved switch for diverse cell functions. Nature. 1990;348:125–132. doi: 10.1038/348125a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cushman I, Casey PJ. RHO methylation matters: a role for isoprenylcysteine carboxylmethyltransferase in cell migration and adhesion. Cell Adh Migr. 2011;5:11–15. doi: 10.4161/cam.5.1.13196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Truong LN, Wu X. Prevention of DNA re-replication in eukaryotic cells. J Mol Cell Biol. 2011;3:13–22. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjq052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu J, Lu LY, Yu X. The role of BRCA1 in DNA damage response. Protein Cell. 2010;1:117–123. doi: 10.1007/s13238-010-0010-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McKenzie S, Kyprianou N. Apoptosis evasion: the role of survival pathways in prostate cancer progression and therapeutic resistance. J Cell Biochem. 2006;97:18–32. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shields JM, Pruitt K, McFall A, Shaub A, Der CJ. Understanding Ras: ‘it ain’t over ‘til it’s over’. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:147–154. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01740-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Milas L, Raju U, Liao Z, Ajani J. Targeting molecular determinants of tumor chemo-radioresistance. Semin Oncol. 2005;32:S78–81. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2005.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hood JD, Cheresh DA. Role of integrins in cell invasion and migration. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:91–100. doi: 10.1038/nrc727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shibamoto S, Hayakawa M, Takeuchi K, Hori T, Oku N, Miyazawa K, Kitamura N, Takeichi M, Ito F. Tyrosine phosphorylation of beta-catenin and plakoglobin enhanced by hepatocyte growth factor and epidermal growth factor in human carcinoma cells. Cell Adhes Commun. 1994;1:295–305. doi: 10.3109/15419069409097261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Braunschweig T, Chung JY, Hewitt SM. Tissue microarrays: bridging the gap between research and the clinic. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2005;2:325–336. doi: 10.1586/14789450.2.3.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brennan DJ, Kelly C, Rexhepaj E, Dervan PA, Duffy MJ, Gallagher WM. Contribution of DNA and tissue microarray technology to the identification and validation of biomarkers and personalised medicine in breast cancer. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2007;4:121–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lamango NS, Ayuk-Takem LT, Nesby R, Zhao WQ, Charlton CG. Inhibition mechanism of S-adenosylmethionine-induced movement deficits by prenylcysteine analogs. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;76:433–442. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2003.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lamango NS, Koikov L, Duverna R, Abonyo BO, Hubbard JB. Non-cholinergic organophosphorus toxicity: possible mechanism involving the protein prenylation pathway. In: Webster LR, editor. Neurotoxicity Syndromes. New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc.; 2007. pp. 37–68. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moretto A, Colosio C. Biochemical and toxicological evidence of neurological effects of pesticides: the example of Parkinson’s disease. Neurotoxicology. 2011;32:383–391. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Seabra MC, Ho YK, Anant JS. Deficient geranylgeranylation of Ram/Rab27 in choroideremia. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:24420–24427. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.24420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]