Abstract

The ETV6-RUNX1 fusion gene, found in 25% of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), is acquired in utero but requires additional somatic mutations for overt leukemia. We used exome and low-coverage whole-genome sequencing to characterize secondary events associated with leukemic transformation. RAG-mediated deletions emerge as the dominant mutational process, characterized by recombination signal sequence motifs near the breakpoints; incorporation of non-templated sequence at the junction; ~30-fold enrichment at promoters and enhancers of genes actively transcribed in B-cell development and an unexpectedly high ratio of recurrent to non-recurrent structural variants. Single cell tracking shows that this mechanism is active throughout leukemic evolution with evidence of localized clustering and re-iterated deletions. Integration of point mutation and rearrangement data identifies ATF7IP and MGA as two new tumor suppressor genes in ALL. Thus, a remarkably parsimonious mutational process transforms ETV6-RUNX1 lymphoblasts, targeting the promoters, enhancers and first exons of genes that normally regulate B-cell differentiation.

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 25% of B-cell precursor ALL is characterized by a balanced t(12;21) chromosomal translocation that creates the ETV6-RUNX1 fusion gene, conferring a favorable prognosis1. This particular disease has shaped our understanding of the development of cancer well beyond leukemia, illuminating the long latency between initiating genetic lesion and clinically overt disease; the patterns of co-operativity among oncogenic mutations; and the complex evolutionary trajectories a cancer can follow. Monozygotic twin studies with concordant ALL and ‘backtracking’ studies using archived neonatal blood spots established that ETV6-RUNX1 is an initiating event arising prenatally in a committed B-cell progenitor2. However, the fusion gene is not sufficient on its own to cause overt leukemia and a number of studies have now provided strong evidence that additional mutations are essential for the development of ALL3. Twin studies confirm that these additional events are most likely to be postnatal and secondary to the ETV6-RUNX1 fusion4.

The genome of ETV6-RUNX1 ALL has been well characterized at the copy number and cytogenetic level. Array-based genome-wide profiling studies have shown copy number aberrations (CNA) to be common, comprised mostly of deletions and affecting genes involved in B-lymphocyte development and differentiation5 such as CDKN2A, PAX5, BTG1, TBLXR1, RAG1, RAG2 and the wild-type copy of ETV6. The presence of V(D)J recombination sequence motifs close to these CNAs has suggested a role for aberrant RAG endonuclease targeting at these loci6-10, but these studies have been limited to analysis of a small number of annotated breakpoints at specific genes.

To obtain a detailed portrait of the composite genetic events that, in concert with the ETV6-RUNX1 fusion gene, drive this subtype of ALL, we carried out genomic analysis of diagnostic samples from 57 patients (Supplementary Table 1). We find that the critical secondary events leading to leukemic transformation in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL are frequently driven by genomic rearrangement mediated by aberrant RAG recombinase activity, and only infrequently by point mutations. The RAG-mediated signature is unparalleled among cancer-associated mutational processes for its specificity in inactivating the very genes that would usually promote normal cellular differentiation.

RESULTS

Structural variation analysis

Whole-genome sequencing for structural variation (SV) analysis (average physical depth: 22x) was performed on the leukemic samples of 51 cases (Supplementary Table 2). SV analysis identified the ETV6-RUNX1 fusion gene in all 51 samples tested, demonstrating high sensitivity for structural variant detection (Supplementary Table 3). All SVs reported in the present study were confirmed by breakpoint-specific PCR and shown to be somatically acquired (Supplementary Table 4). Mapping to base-pair resolution by capillary sequencing was obtained for 67.5% of breakpoints. For 50 of these cases and an additional 5 cases, we sequenced the exomes of paired leukemic and remission DNA (Supplementary Table 5). All putative coding mutations were validated using either high-depth pyrosequencing or capillary sequencing, and here we report only experimentally validated somatic variants (Supplementary Table 6). Whole-genome sequencing of both diagnostic and remission DNA to 50x average sequence coverage was performed for one patient. PCR for the IGH rearrangement showed that all samples in the study had rearranged V(D)J loci, with oligoclonality observed in most cases11 (Supplementary Table 1).

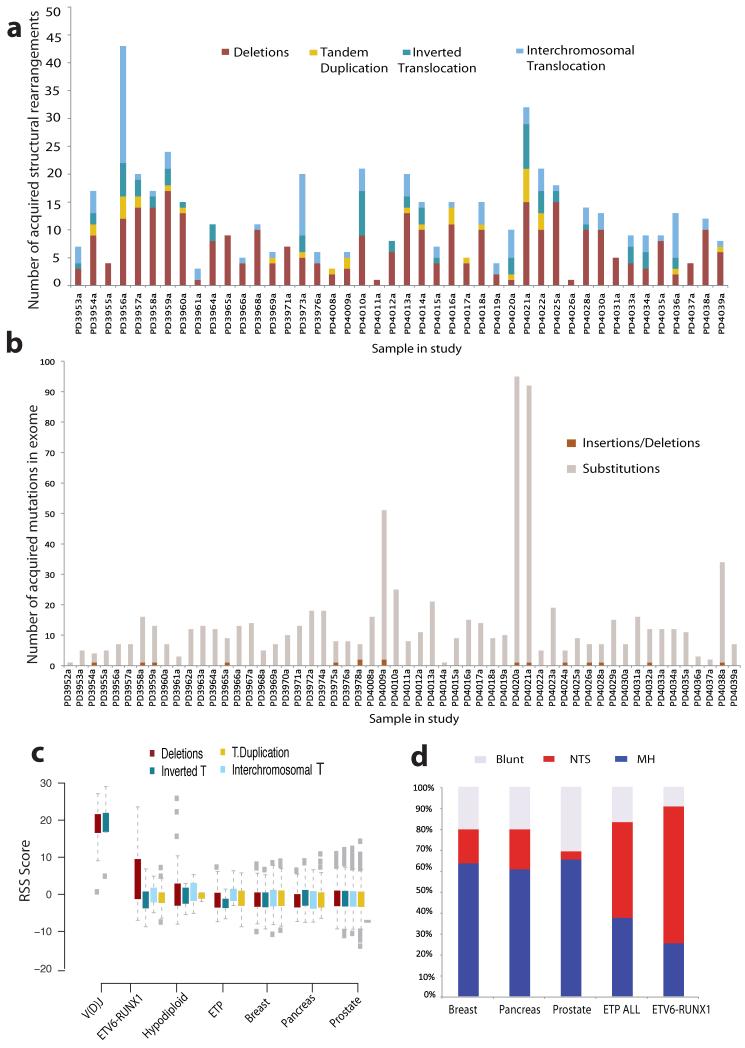

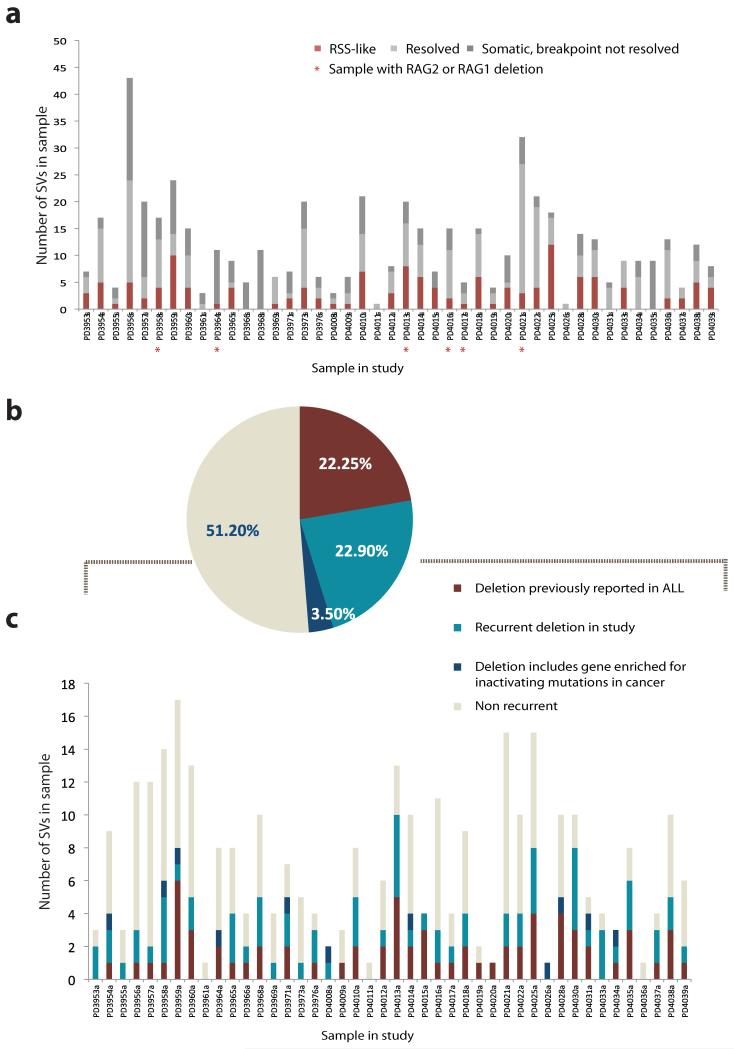

Further to the fusion gene, we confirmed 523 SVs (average=11/patient, range 0-49) in 44 of the samples in the study (Fig.1a). 417 were intrachromosomal and 106 were interchromosomal (Supplementary Table 4), with 76% of intrachromosomal rearrangements being deletions. We identified 779 somatic substitutions and 16 indels across 715 protein-coding genes and 3 microRNAs (Supplementary Table 6, Fig.1b). Each patient had on average 14 gene coding point mutations (range: 1-95), consistent with the low number of acquired somatic mutations reported in hematological cancers and childhood malignancies.

Figure 1. Acquired mutations in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL.

(A) Structural variation in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL. Bar plots representing distribution of genomic rearrangement events in 44 samples (x-axis) with confirmed somatic SVs. Deletions are shown in burgundy, tandem duplications in yellow, inverted intrachromosomal in deep blue and inverted interchromosomal in light blue. All patients harbored the t(12;21) translocation which is not included in the bar plots. (B) Distribution of coding mutations as identified by exome sequencing across each patient in the study. Each sample is represented by a bar on the x-axis and the number of confirmed somatic substitutions and indels by the height of each bar plot on the y-axis. (C) RAG recognition sequence score enrichment in ETV6-RUNX1 deletions. RSS score for each SV class (Deletions, Inverted intrachromosomal rearrangements, Tandem Duplications and Interchromosomal Translocations) in the control V(D)J breakpoints and structural variants in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL, Hypodiploid ALL, ETP-ALL, breast cancer, pancreatic and prostate cancer. An RSS Score of 8.55 corresponds to FDR < 0.01. (D) Breakpoint resolution in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL. Bar charts showing the proportion of resolved breakpoint sequences with non-templated sequence insertion at the breakpoint junction (NTS), evidence of microhomology (MH) between the two ends of the breakpoint or clean blunt-ends at the breakpoint junctions in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL compared to the proportion of each breakpoint class in sets of confirmed rearrangements in Early T progenitor ALL (ETP), breast, pancreatic and prostate cancer.

SVs in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL bear the hallmarks of RAG activity

During lymphocyte development, cells undergo somatic recombination, also known as V(D)J recombination, at the variable immunoglobulin and T-Cell receptor loci12. This process is primarily mediated by the RAG endonucleases, RAG1 and RAG2, which are targeted to the V(D)J sites by Recombination Signal Sequences (RSS) consisting of a highly conserved heptamer (CACAGTG) and a less conserved nonamer (ACAAAAACC) separated by a 12bp or 23bp sequence-independent spacer13. RAG endonucleases bind DNA at the RSS sequences, and cleave the DNA at the boundary between the RSS and the flanking coding sequence, thereby generating two blunt and two hairpin ends that are held in close proximity to each other by the RAG complex13. Processing of these ends often involves the addition of non-templated sequence (NTS) at the breakpoint by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) in a process that results in further diversification of the V(D)J locus14. Functioning heptamer or nonamers outside the context of a conserved RSS sequence, an open chromatin state, H3K4me3, non-B DNA sequences, or deaminated methyl CpGs are all genomic conformations that have been associated with alternative mechanisms of RAG recruitment, targeting of DNA breaks, breakpoint localization and subsequent genomic rearrangement6,15,16.

The clustering of deletion breakpoints adjacent to RSS or motifs approximating the conserved RSS DNA sequences17 in lymphoid genes has provided some evidence of off-target RAG activity in leukemias6-10,18. However, this has not been systematically evaluated on a genome-wide basis.

We resolved 354/523 SVs to base-pair resolution, the largest such dataset in ALL by some margin (Supplementary Table 4), and searched for the conserved RSS sequence (Supplementary Fig.1), the proposed AID recognition motifs16 and for the presence of CpGs at breakpoint sites (Supplementary Fig.2) using a bespoke algorithm. As a positive control, we used 26 structural rearrangements at the IGH and TCR loci, representing canonical RAG sites (Fig.1c, Supplementary Table 7, Supplementary Fig.1a-c). To confirm that our findings were specific to ALL, we also evaluated two published ALL datasets (hypodiploid ALL, and early T progenitor ALL)10,19,10,19 and compared against published rearrangements from breast, pancreatic and prostate cancers (Fig.1c-1d)20-22.

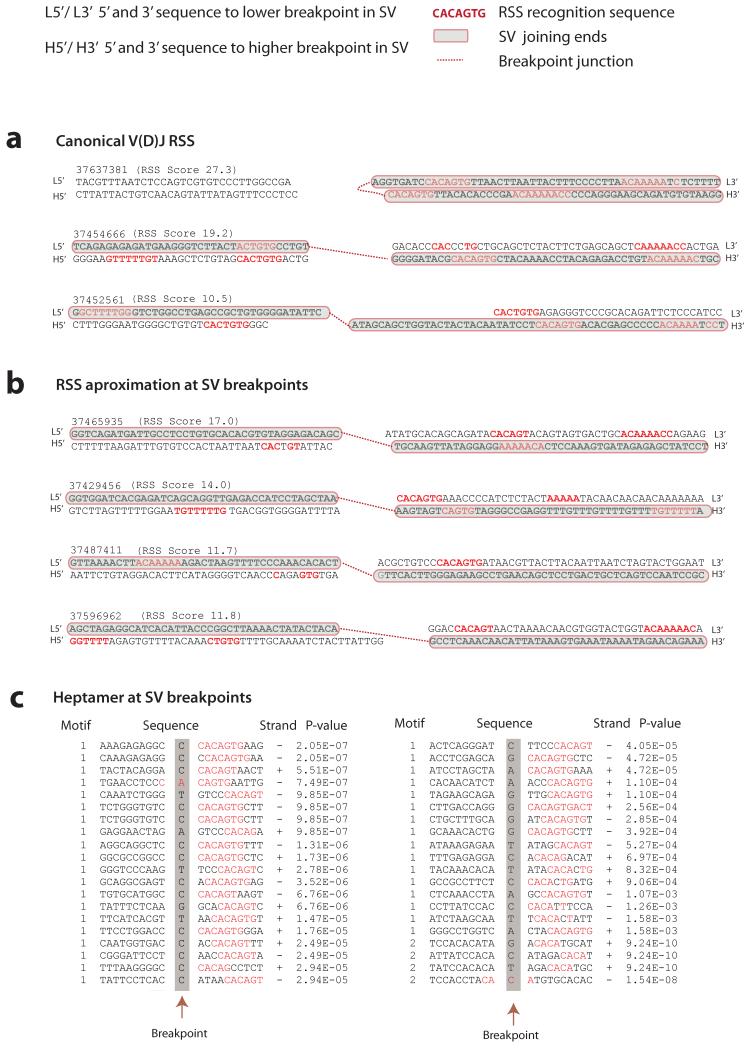

Conserved RSS sequences were computationally detected (RSS Score≥8.55) in 23 of the 26 positive control rearrangements (Fig.2a, Supplementary Table 7) and 44 of 354 somatic SVs outside of V(D)J sites (Fig.2b, Supplementary Table 4, Supplementary Fig.1d-f). As expected, canonical V(D)J RSS signals were characterized by deletions and inverted intrachromosomal rearrangements (Fig.1c) and in 92% (24/26) non-templated sequence was observed at the breakpoint junction (Supplementary Table 7). Enrichment for RSS motifs was particularly striking for genomic deletions in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL (Fig.1c) including variants targeting known B-ALL genes such as ETV6, BTG1, TBL1XR1, RAG2, and CDKN2A/B (Supplementary Table 4). We did not find conserved RSS sequences near breakpoints of the initiating ETV6-RUNX1 rearrangement itself, consistent with it arising in a very early B-lineage progenitor2 via non-homologous end joining.

Figure 2. Evaluation of V(D)J recombination motifs.

RSS heptamer and nonamer sequences are shown in red, spacing annotates position of breakpoint. Retained sequence flanking the breakpoint junction is shown in bold black, shaded in grey with red borders. Genomic sequence is annotated 5′ to 3′ as presented in the reference genome (+) strand. For each rearrangement, the first line indicates the sequence flanking the lower breakpoint, the second line corresponds to the sequence flanking the higher breakpoint. The RSS Score for each rearrangement is shown in parenthesis. A dotted red line annotates the breakpoint junction. For more detailed annotation please refer to Supplementary Figure 1. (A) Rearrangements at the V(D)J locus showing examples of canonical V(D)J recombination signal sequences (in red) in close proximity to the breakpoint junctions. (B) Close approximation to RSS sequence motifs near the breakpoint junction of confirmed structural variants in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL. Represented in this figure are sequence motifs spanning the breakpoints for TBL1XR1 (RgID 37439593); FAF1 and CDKN2C (RgID 37429456); BTG1 (RgID 37487411) and RgID 37596962 showing chr1:190,815,392-190,815,481 joining to chr1:190,926,946-190,927,035. (C) Heptamer sequences identified by agnostic motif search analysis using MEME. A representation of 40 of the 164 breakpoints identified to harbor heptamer like motifs within 20bp of the breakpoint junction. In red, the bases contributing to the motif identification in the ETV6-RUNX1 ALL dataset. Heptamer p values are annotated as calculated by MEME.

To explore the possibility of RAG targeting in non-canonical, or cryptic, RSS we next performed an agnostic motif search analysis23 in the 20bp of sequence spanning the 354 resolved breakpoints. Two significant motifs were discovered by this analysis: (1) the first six bases (underlined) of the perfect heptamer sequence CACAGTG (E-value=9.9×10−81)23, identified across 159 breakpoint junctions (Fig.2c, Supplementary Fig.1g-i); and (2) the first 4 bases of the heptamer sequence, the CACA tetranucleotide (E-value=4.9×10−2) (Supplementary Table 8), nearby 5 rearrangements. As both of these two motifs (CACAGT and the CACA) correspond to the most conserved portion17 of the RSS heptamer sequence, all breakpoints reporting either of these two motifs were annotated as ‘RSS-like’.

Overall, in 140 of 354 (39.5%) rearrangements, we find convincing signatures of RAG recognition sequence motifs at one or both ends (Supplementary Fig.3) of the breakpoint junction. The overwhelming majority of patients studied had at least one SV with an RSS or heptamer signal, and most had several such variants. An equivalent analysis on breakpoints from breast cancers20, pancreatic cancers21 and prostate cancers22 did not show any evidence of RSS sequences (Fig1.c) nor was the heptamer motif identified (Supplementary Table 8). We did not observe specific enrichment for either CpG or any of the proposed AID recognition motifs16 in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL, relative to that observed in other cancers (Supplementary Table 9, Supplementary Fig.2).

The other feature of canonical RAG-mediated V(D)J rearrangement is non-templated sequence (NTS) at the breakpoint. All 44 rearrangements with a near-perfect RSS motif and 73 of the 96 rearrangements with a heptamer motif had novel sequence inserted at the breakpoints, suggestive of TdT activity during the formation of the breakpoint junction. Of the 354 resolved breakpoints overall, 248 (70%) had inserted non-templated sequence, 79 (22.4%) showed evidence of base-pair homology between the two breakpoints and 27 (7.9%) involved blunt-end breakpoints (Supplementary Fig.4). This dataset shows a marked increase in breakpoints characterized by non-templated sequence relative to breast cancer, pancreatic cancer and prostate cancer (frequency of non-templated sequence, 16.2% (n=193), 19% (n=36) and 6.7% (n= 395) respectively; p<2.2×10−16; Fig.1d).

Other mechanisms of genomic rearrangement were observed occasionally, including chromothripsis24 and chains of rearrangements similar to those reported in prostate cancer25(Supplementary Fig.5).

Chromatin signatures at structural variation sites

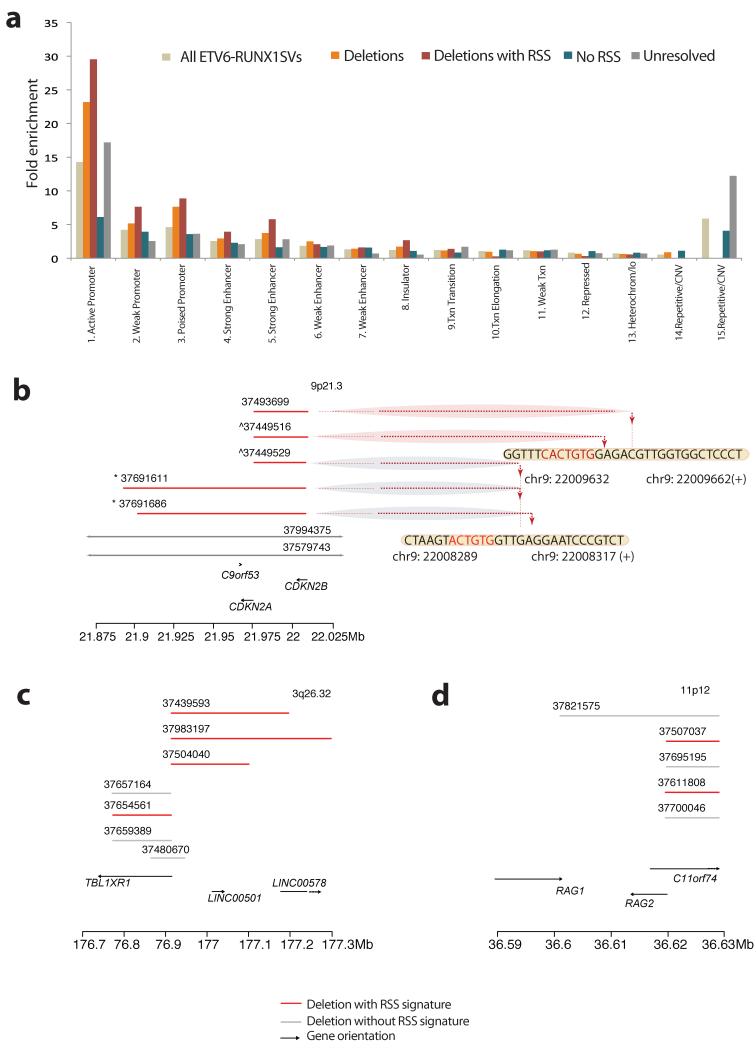

To explore underlying genomic features that influence the distribution of genomic rearrangements, we studied whether there was any enrichment for particular chromatin states among the 523 SVs identified. To do this, we used the 15 chromatin states defined by the ENCODE project26. We find that structural variants in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL show up to 14-fold enrichment for active promoter and enhancer regions relative to the other chromatin states (p<2.2×10−16, Fig.3a). This is particularly pronounced for those SVs that have an RSS-like motif – for example, deletions with RSS-like sequences show 33-fold enrichment for active promoter regions (p<2.2×10−16, Fig.3a). Overall, in our study 30% of resolved rearrangements mapping in close proximity to an RSS-like motif occurred in promoter sites, 14% in enhancers and 13% in sites of transcription (Supplementary Table 10).

Figure 3. Chromatin segmentation of all somatic SVs in ETV6-RUNX1.

(A) Bar plot of SVs identified in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL that map in one of the 15 chromatin states defined by the ENCODE project from lymphoblastoid cell line GIM12878 genome segmentation. The heights of the bars reflect the fold-enrichment of each SV category for the 15 chromatin states (Supplementary Table 10). ETV6-RUNX1 SVs show significantly different SV distribution from that expected by chance (Goodness of fit test; p<2.2×10−16)(B-D) Clustering of deletion breakpoints (Supplementary Table 12). Red lines represent deletions with resolved breakpoints with either an RSS Score ≥ 8.55 or a heptamer within 20 bp of the breakpoint junction. Grey lines indicate deletions with resolved breakpoints without significant RSS motif scores at their breakpoint junctions. Arrows indicate genes and orientation of transcription. Dotted lines point towards the precise base-pair involved at the breakpoint junction. (B) Clustering of deletions at the CDKN2A locus (9p21.3) with evidence of re-iterated deletions in 2 samples. The signs ^ and * indicate that SVs were identified in the same sample (Supplementary Table 10). (C) Clustering of deletions at the TBL1XR1 locus (9p21.3) and (D) the RAG1/2 locus (11p12).

The relationship between rearrangements and chromatin state observed in ETV6-RUNX1 genomes is significantly different (p<2.2×10−16) to that expected by chance. SVs reported in a recent analysis of 40 cases with hypodiploid ALL10 were also significantly different from the null distribution (p<2.2×10−16; Supplementary Fig.6), with SVs mapping close to RSS-like sequences also showing a preponderance for promoter and enhancer sites (13-fold and 17-fold enrichment respectively). In contrast, breast cancer SVs showed a rather uniform distribution across the 15 chromatin states with modest but statistically significant enrichment in gene footprint regions (p<2.2×10−16), as previously described27, but not promoters or enhancers (Supplementary Fig.6).

The inferred chromatin states in the ENCODE data derive from a combinatorial code of individual histone modifications. We therefore explored whether specific histone marks or transcription factor binding sites (Supplementary Table 11) were linked with genomic rearrangements in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL. We find significant correlation of rearrangement positions with peaks of H3K4me3, a marker of active promoters (q=0.02, Supplementary Fig.7). This is particularly important because the PHD finger of the RAG2 protein has been shown to bind trimethylated H3K428, which would explain why this mutational process so precisely targets regions residing within active promoters and enhancers.

Localized clustering of deletions close to RSS-like motifs across patients

Tight clustering of deletions next to RSS-like sequences9 as well as re-iterated CNAs in diagnostic ALL samples29 have been previously reported. We identified 14 clusters of at least 2 (range: 2-6) deletions with breakpoints in close proximity to each other as well as the heptamer (Fig.3b-d). Amongst 4 samples with deletions at 9p21.3, for example, the deletion breakpoints were 0 to 8bp apart from each other and in close proximity to an RSS-like sequence (Supplementary Table 12, Fig.3b). Consistent with the preceding analysis, these breakpoint clusters frequently coincided with gene promoters (Fig.3b-d, Supplementary Fig.8). Within each locus, deletions that did not satisfy our criteria for annotation as RSS-like were observed to cluster with SVs that did have a nearby RSS motif (Fig.3.d, Supplementary Table 12). Not surprisingly, the genes disrupted in these clustered and re-iterated deletions are among the most frequently targeted in ALL including CDKN2A, BTG1, BTLA, TBL1XR1 and RAG1/28-10,19,29.

These data emphasize the targeted nature of the RAG-mediated mutational process. Not only is there enrichment of structural variants in active promoter and enhancer regions genome-wide, there is also a striking propensity for breakpoints to cluster within very specific ranges in individual promoter or enhancer elements.

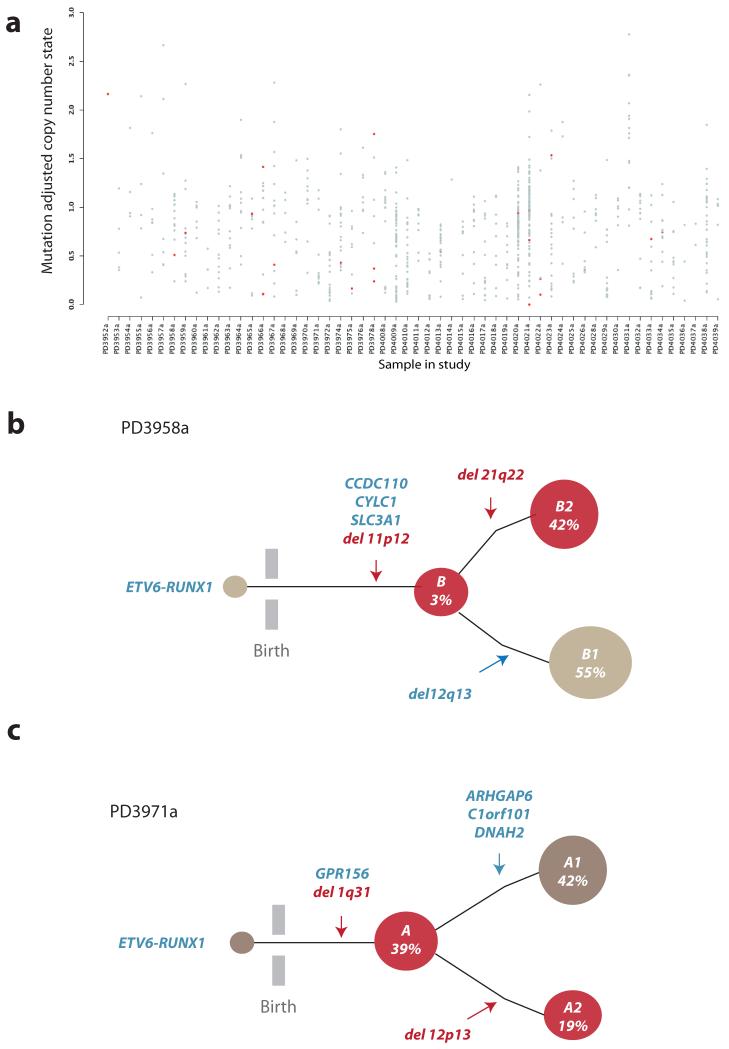

Clonal heterogeneity and timing of RAG-mediated deletions in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL

Massively parallel sequencing data enable estimation of the proportion of tumor cells carrying a mutation from the fraction variant allele20. To study the clonal complexity of ETV6-RUNX1 ALL, we calculated variant allele fractions for all mutations identified by exome sequencing (Supplementary Table 6). We find extensive clonal heterogeneity across most patients in the study (Fig.4a), confirming previous findings that multiple subclones co-exist at presentation in ETV6-RUNX1 patients7,29.

Figure 4. Clonal heterogeneity in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL.

(A) X-axis represents each sample, y-axis the adjusted copy number of each mutation taking into account variant allele fraction and tumor cellularity. Grey dots are all acquired substitutions and indels identified from the exome study. Red dots represent previously characterized oncogenic mutations in cancer (Supplementary Table 6). (B) PD3958a clonal architecture. Acquired mutations are shown in blue whilst SVs with an RSS or RSS-like sequence at the breakpoint junction are shown in red. 139 single cells were positive for the ETV6-RUNX1 fusion gene, the three missense mutations in CCDC110, CYLC1 and SLC3A1, as well as the deletion on 11p12. The remaining two deletions on 12q13 and 21q22.12, were present in 55% and 42% of the cells respectively and were mutually exclusive. Both 11p12 and 21q22.12 deletions contained RSS sequence motifs at the junction. (C) Schematic representation of clonal structure for PD3971a. Acquired mutations are shown in blue whilst SVs with an RSS or RSS-like sequence at the breakpoint junction are shown in red. ETV6-RUNX1 was present in all 130 cells, as were a heterozygous mutation in GPR156 and the deletion mapping to 1q31. Mutations on ARHGAP6, C1orf10 and DNAH2 co-occur within a distinct clonal branch (in grey) representing 39% of the cells whereas the 12p12-13 deletion, which affects ETV6, is present in 19% cells, identifying a distinct subclone (in red).

To assess the timing of aberrant RAG-mediated deletions, we used a single cell genotyping protocol30 in two patients (Supplementary Fig.9; Table 1). For PD3958a, 143 cells were interrogated for the fusion gene, three genomic deletions and three acquired missense mutations (Fig.4b, Supplementary Table 13). For PD3971a, 159 cells were genotyped for the fusion gene, deletions on 1q31 and 12p13.2-p12.3, and four point mutations (Fig.4c, Supplementary Table 14). With the exception of del(12p13), all deletions studied carried an RSS signature.

Table 1.

Single cell genotyping of acquired mutations and deletions in PD3958a and PD3971a.

Variant allele fraction is reported for next-generation sequencing data. Adjusted estimate of total cell fraction reporting the variant using next-generation sequencing data copy number profiles and derived estimates of aberrant (normal) cell fraction. Single cell data reports the proportion and confidence intervals of single cells (ETV6-RUNX1 +ve) reporting the variant of interest. All ETV6-RUNX1 −ve cells were wild type for all the remaining variants genotyped.

| Type | Variant | Chr | Pos | WT | Mt | Variant allele fraction | Copy number adjusted estimated cell fraction | Single cell data (normal cells excluded) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD3958a | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Deletion | Del11p12* | 100% (96.6-100) | ||||||

| Deletion | Del21q22* | 41.7% (33.5-50.4) | ||||||

| Deletion | Del12q13 | 55.3% (46.7-63.7) | ||||||

| Substitution | CCDC110_p.Q432E | 4 | 186380447 | G | C | 45.30% | 76.14%(72.78-79.6) | 100% (96.6-100) |

| Substitution | CYLC1_p.N205Y | X | 83128329 | A | T | 95.20% | 100% | 100% (96.6-100) |

| Substitution | SLC3A1_p.S168L | 2 | 44507927 | C | T | 52% | 100% | 100% (96.6-100) |

|

| ||||||||

| PD3971a | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Deletion | Del1q31* | 100% (96.4-100) | ||||||

| Deletion | Del12p13* | 19.2% (13.05-27.27) | ||||||

| Substitution | ARHGAP6_p.M362K | X | 11204544 | A | T | 12.70% | 29.2%(22.9-35.6) | 39% (33-50.5) |

| Substitution | C1orf101_p.G789S | 1 | 244769058 | G | A | 14.10% | 32% (19-47) | 39% (33-50.5) |

| Substitution | DNAH2_p.R1797* | 17 | 7681635 | C | T | 13% | 29.8%(24-35.8) | 39% (33-50.5) |

| Substitution | GPR156_p.S652A | 3 | 119886370 | A | C | 42.40% | 97.4%(87.1-100) | 100% (96.4-100) |

Indicate deletions with an RSS signature. For SV coordinates please refer to Supplementary Table 4.

Using the single cell data, we reconstructed partial phylogenies of tumor evolution for the two patients (Fig.4b-c). These show that: the ETV6-RUNX1 fusion gene was always on the trunk of the phylogenetic tree, as expected for an initiating lesion; point mutations could be either clonal or subclonal, and showed good correlation between the observed variant allele fraction in exome data and the fraction of single leukemia cells reporting the variant (Table 1); and, in both cases, the RAG-mediated deletions were found on both the trunk of the phylogenetic tree and further subclonal branches.

These data suggest that RAG-mediated genomic instability in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL was an ongoing mutational process in these two patients. Intriguingly, the RAG locus on chr11p12 is itself a frequent target of deletion (Supplementary Table 4). Non-templated sequence was present in 4 of the 5 resolved SVs and in 3 there was evidence of an RSS signature, suggesting that the RAG complex mediated its own deletion. Samples with 11p12 deletions did not differ in either the total number of observed SVs or the total number of RAG-mediated SVs (Fig.5a). The deletions we observed were heterozygous and it is therefore unclear what, if any, selective benefit might accrue to a clone from deleting this locus.

Figure 5. Characterization of structural variation in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL.

(A) Distribution of structural variant categories identified in each sample in the study. In red, the SVs with resolved breakpoints and evidence of RSS or heptamer motifs adjacent the breakpoint junction(n = 140), in light grey SVs with resolved breakpoint junctions that did not reach the criteria for the RSS motif assignment (n=214). In dark grey the proportion of confirmed SVs to be somatically acquired that failed resolution of the breakpoint junction (n=169). Red stars indicate samples with confirmed deletions spanning the RAG locus (B) Annotation of SVs in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL study showing deletions that have been previously reported in ALL (n=69, 22%), deletions that are recurrent in the study (n=71, 23%) or deletions that include genes enriched for inactivating mutations in cancer (n=11, 3.5%). Non-recurrent events are shown in light grey (n=159, 51%). (C) Same SV distribution by sample.

SVs show a high ratio of recurrent to non-recurrent variants

Classically, in cancer genomics, we use high rates of recurrence of a given event to distinguish mutations that are likely to be oncogenic from passenger variants. Restricting our analysis to deletions, we evaluated whether the genic consequence of each SV was recurrent in ALL or overlapped with genes showing recurrent copy number loss, or inactivation by point mutation in other cancers (Supplementary Table 4). Overall, of 310 eligible deletions (Supplementary Table 4), 151 satisfy these criteria, accounting for 49% of deletions in the study. Each sample carried on average three (n=3.4) CNAs that include genes previously reported to be inactivated in cancer or are recurrently affected by CNA in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL (Fig.5b, Supplementary Table 4). That half of deletions are recurrent is a rather remarkable figure.

This markedly non-random distribution of mutations has significant implications for the identification of cancer genes in ALL. Typically, the background distribution of mutations is assumed to be uniform. With this RAG-mediated mechanism, however, passenger rearrangements would also cluster in actively transcribed genes, and consequently mimic true cancer genes. In this setting, the best approach to distinguish a true cancer gene from clustered passenger rearrangements would be to find enrichment of truncating point mutations in the same gene. This has, for example, been observed in PAX5 and CDKN2A in ALL31. Thus, exome sequencing in ALL is an important confirmatory step for defining new cancer genes.

Integrative genome and exome analysis reveals new ALL genes

Integrative analysis of exome and whole-genome data identified 694 genes to be recurrently affected by copy number alteration, chromosomal rearrangement and/or acquired mutations (Supplementary Table 15). The most frequent and recurrent somatic alterations that are identified in the present study include deletion or mutation of ETV6, BTG1, TBL1XR1, PAX5, CDKN2A, NR3C2, RAG2 and BTLA, all loci previously described by cytogenetic or copy number profiling studies (Fig.6a)5. Of these genes, ETV6, BTG1 and TBL1XR1 all had an inactivating point mutation (nonsense, frameshift or splice site) and such mutations have been found previously in PAX5, CDKN2A, and ETV6, suggesting they are bona fide ALL genes. We note that the majority of these inactivating point mutations or genomic rearrangements were heterozygous, suggesting that haploinsufficiency of leukemia suppressor genes may be frequently operative in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL.

Figure 6. Acquired somatic events in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL.

(A) Each column represents a sample. The first row indicates the patients with exome sequencing data, the second row depicts samples with whole-genome sequencing data for rearrangements. In the ETV6-RUNX1 row, purple boxes indicate the automated detection of the fusion genes in the samples that whole-genome sequencing was performed. First panel concentrates on genes that are predominantly affected by genomic rearrangement. Second panel annotates previously characterized cancer genes that are recurrently mutated in the present study. Crosses indicate homozygote events and mixed colors indicate occurrence of more than one type of event in the same sample. (B) Independent deletion of ATF7IP. Copy number plot showing a focal deletion of ATF7IP in PD4028a, RgID HS20_6248:31106.

A systematic evaluation of all genes affected by structural variation and mutation together identified three previously unreported genes that would not have been highlighted by either dataset alone in ALL. ATF7IP encodes a nuclear protein that, by interaction with MBD1 and SETDB1, mediates heterochromatin formation and transcriptional repression. ATF7IP maps to 12p13.1 and it is located 2.7Mb centromeric to ETV6, which is a target of frequent deletions32. In our cohort, eight of the nine patients with 12p13 deletions had concomitant deletions in both genes. One patient, however, had a focal deletion on 12p13.1 targeting ATF7IP only (Fig.6b). Furthermore, exome sequencing analysis identified two additional samples with ATF7IP mutations, one inactivating nonsense mutation (p.R363*) and one missense mutation (p.R571Q) that alters the likely nuclear localization signal, maps within the SETDB1 interaction domain and is predicted to be deleterious (Supplementary Table 6). Additional evaluation of existing SNP6 array data from 21 ETV6-RUNX1 patients at diagnosis and relapse33 identified 10 samples with deletions extending to both genes, 7 patients with ETV6 only deletions and one patient with an independent ATF7IP deletion acquired at relapse (Supplementary Table 16). ETV6 and ATF7IP are two of the most commonly mutated genes in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL and although they are deleted simultaneously in ~67% of the 12p13 deletions, the present study provides evidence for an independent role for ATF7IP mutations in ETV6-RUNX1 pathogenesis.

MGA is a transcription factor that regulates the expression of Max network and T-box family target genes including MYC34. Deletions mapping to 15q14-q15.2 resulting in loss of MGA, were identified in two patients (PD3971a and PD3951a). In addition, a frameshift nonsense mutation p.D187fs*46 in PD4026a and a missense mutation in PD4010a, p.S162F, mapping within the DNA binding domain were identified. STAG2 is a component of the cohesin complex, which is often inactivated by mutations in myeloid leukemias35 and has recently been observed in chromosomal translocations in T-ALL36. In our study, STAG2 was mutated in 5 patients; three had interchromosomal rearrangements between Xq25 and chromosomes 6 and 9, whilst PD4018a and PD4031a harbored focal intronic deletions of unclear consequence. A missense mutation p.R344K was identified in PD4022a. We also identified a nonsense mutation in SMC1A and a missense mutation in SMC5, two additional components of the cohesin complex (Fig.6a).

Exome sequencing analysis identified 795 somatic mutations mapping to 719 genes, with 36 genes carrying recurrent non-silent mutations in at least two patients each. Of these genes only 3 (KRAS, NRAS and SAE1) were mutated significantly more than expected by chance, as were the recently reported hotspot mutations in NSD2 37 (Supplementary Table 6). Importantly, 34 of the genes reported in the present study were enriched for inactivating mutations across the 7,651 cancers (Supplementary Table 17). Of these, the most significant genes are well-recognized tumor suppressors such as CDKN2A/B, NF1, MLL2, ARID2, P53, RB1, APC, SETD2, KDM6A, CTCF, ARID1B, FBXW7 and BCOR. This heterogeneity underscores the biological complexity present even within a well-defined subtype of ALL.

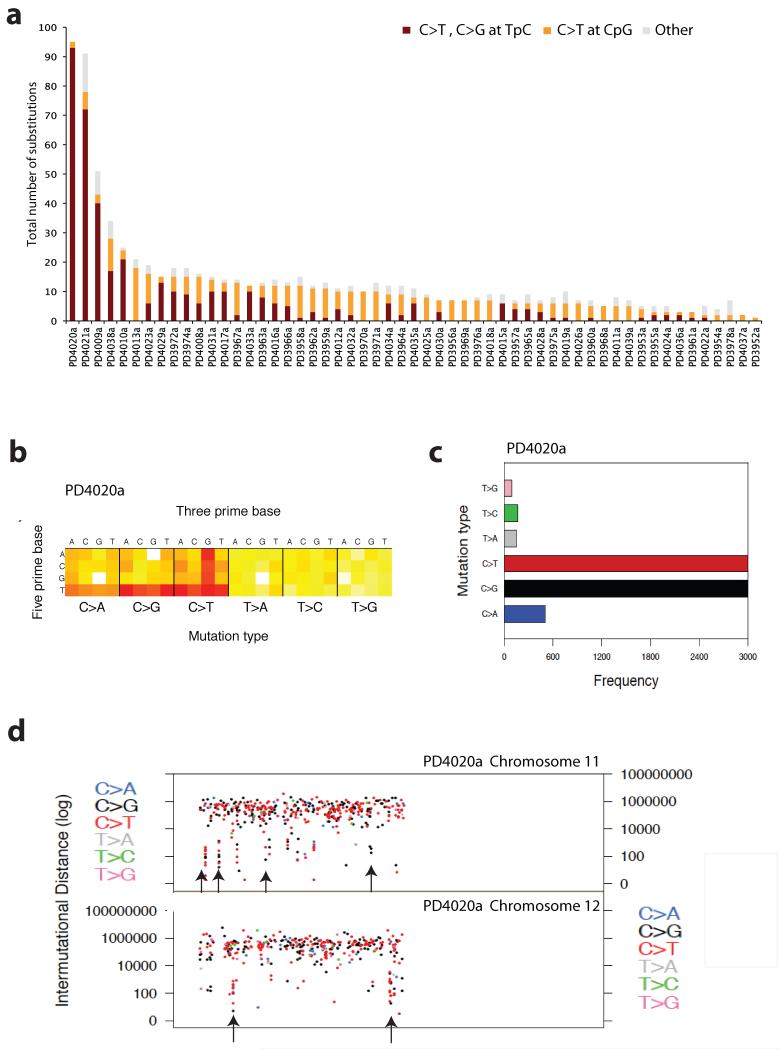

Mutational signatures in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL

Analysis of the nucleotide composition of each mutation and the sequence context in which they occur identified two main mutational signatures: C>T transitions at CpGs and C>G and C>T at TpCs, contributing 56% and 32% of all substitutions respectively (Fig.7a). The number of C>T mutations at CpGs significantly correlated with age at diagnosis (r2=0.62, p=1.6×10−5), whereas C>T mutations at TpCs did not. C>T at methylated cytosine is the most widespread mutational process in genome evolution and cancer.

Figure 7. Mutational signatures in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL.

(A) Sequence context of point mutations identified in exome study. In burgundy all point mutations that correspond to a C>T or C>G at a TpC locus, in orange all C>T changes at CpG loci and in grey all remaining acquired substitutions. (B) Heatmap representation of all the mutations identified by whole-genome sequencing in PD4020a. The heatmap is separated into six boxes representing each mutation type(C>A, C>G, C>T, T>A, T>C and T>G). For each mutation type, 16 possible combinations of a 5′ preceding base as shown on the Y axis followed by one of 4 nucleotide basis on the X axis. Red indicates high number of mutations, yellow few and white no such mutations observed. (C) Barplot showing the mutation spectrum across all point mutations identified in the genome for PD4020a. (D) Scatter plot showing mutations clusters in chromosomes 11 and 12 identified by whole-genome sequencing of PD4020a. Each dot represents a mutation type, in blue C>A, black C>G, red C>T, grey T>A, green T>C and pink T>C. The order of the mutations along the x-axis reflects their position in the genome but not the precise chromosome coordinate i.e. mutation 1 followed by mutation 2, etc. The height of each subsequent mutation reflects the distance from the preceding mutation on a log scale i.e. 100bp, 1000bp or 1 MB. Mutation trickles are seen where localized clusters of hypermutation are observed, mostly comprised of C>G or C>T mutations (Supplementary Table 18).

The second most frequent process involved transitions and transversions at cytosines in a TpC context. This process was observed in 36 (64%) of the samples sequenced, and was the predominant signature in the three samples with the most acquired mutations (Fig.7a). This signature is mostly represented by TpCpW (where W=A or T) (Supplementary Fig.10) and is consistent with the reported preference of APOBEC family of enzymes for cytosine deamination to uracil38,39. This process has recently been proposed as a likely mechanism underlying clusters of localized somatic hypermutation, kataegis in breast and other cancers20,40,41.

To explore this signature, high-depth whole-genome sequencing was performed in PD4020a. Whole-genome sequencing analysis identified 7,948 high-confident substitutions and 122 indels (Supplementary Tables 18-19). Strikingly, 94% of the substitutions were C>G or C>T at TpC (Fig.7b-c). 19 clusters of 6 or more mutations presenting on the same strand were identified40 (Supplementary Table 18, Supplementary Fig.11). Kataegis in breast cancer often co-localizes with structural rearrangement. This however was not the case in PD4020a, where no SVs mapped within 5Kb of any mutation cluster.

DISCUSSION

The present study has provided a detailed characterization of the genomic architecture of 57 patients with ETV6-RUNX1 ALL. A paucity of recurrent coding region mutations and a scarcity of kinase mutations that are common in the high-risk subtypes of ALL42 is observed. Genomic rearrangement emerges as the predominant driver of this disease. In a high proportion of the SVs characterized, we identify RAG recognition sequences near the breakpoint junctions, evidence of TdT activity and enrichment in active promoter and enhancer regions. Our data may underestimate the contribution of RAG-mediated recombination to structural variation in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL. We find a large proportion of SVs that did not satisfy our RSS annotation criteria, yet followed the same chromatin distribution as the RSS-like SVs, with strong enrichment at promoters, and exhibited non-templated sequence at the breakpoint junction. A proportion of those may have been mediated by RSS sequences that were less conserved or more distant than those we screened6,43.

That aberrant RAG activity might contribute to leukemogenesis has been proposed previously6-10. We note that the presence of full or partial RAG recognition motifs in genes near breakpoints is not itself evidence for functional competence of those sites nor is the presence of non-templated sequence at the breakpoint junction firm evidence of TdT activity post RAG targeting. Furthermore, TdT can act on DNA breaks caused by mechanisms other than RAG activity44. However, the specificity of the genomic profiles observed in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL coupled with the absence of these motifs near rearrangements from breast, pancreatic and prostate cancer, make their functional relevance highly probable. There is still much to explore to obtain a detailed understanding of the biochemical relationships linking sequence context, chromatin landscape and RAG activity in ETV6-RUNX1 positive lymphoblasts.

The picture that emerges of ETV6-RUNX1 ALL is one of stalled early B-lineage differentiation2,45. The ETV6-RUNX1 fusion itself arises in either a foetal haemopoietic stem cell or very early B-progenitor2,45, promoting a covert pre-leukaemic clone with partially stalled passage through the B-precursor developmental compartment2,45,46. RAG recombinases continue to be highly expressed by ETV6-RUNX1 cells, resulting in diverse and ongoing oligoclonal V(D)J rearrangements11. Inactivation of genes that encode transcription factors for B-lineage differentiation would further trap cells within the precursor compartment. These features are not unique to ETV6-RUNX1 ALL, but this subtype, compared with others, does appear to have more extensive IGH rearrangements6,11 and higher RAG gene expression47. It will be interesting to replicate these analyses across the many other subtypes of ALL to evaluate the generality of this mutational process in lymphoblastic leukaemia.

ONLINE METHODS

Patient samples

The patient samples studied in this investigation were collected from Italian or UK hospitals, with informed consent and local ethical review committee approval (CCR 2285, Royal Marsden Hospital NHS Foundation Trust). Collection and use of patient samples were approved by the appropriate IRB of each institution. In addition, this study and usage of its collective materials had specific IRB approval.

Exome capture library construction and sequencing

Matched genomic DNA (3-5ug) from leukemic and samples at full remission from 56 patients with childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (cALL) was prepared for Illumina paired end sequencing (Illumina Inc, SanDiego, CA). Exome enrichment was performed using the Agilent SureSelect Human All Exon 50Mb (Agilent Technologies LTD, Berkshire, UK) kit. Flow-cell preparation, cluster generation and paired end sequencing (75base-pair reads) was performed according to the Illumina protocol guidelines on an Illumina GAII Genome Analyzer. The target coverage per sample was for 70% of the captured regions at a minimum depth of 30× sequencing coverage. Detailed sequencing metrics are provided in Supplementary Table 5.

Low depth whole-genome sequencing

Leukemic DNA (2-5ug) for 51 patients was prepared for short insert (300-400bp) library construction flow cell preparation and cluster formation using the Illumina no-PCR library protocol48. 50 base paired-end sequencing was performed on an Illumina GAIIx Genome Analyzer as per manufacturers guidelines. Detailed sequencing metrics statistics are presented in Supplementary Table 3.

Variant detection -Substitutions

Sequencing reads were aligned to the human genome (NCBI build 37) using the BWA algorithm on default settings49. An in-house algorithm, CaVEMan (Cancer Variants through Expectation Maximisation), was used to identify somatically acquired single nucleotide substitutions. CaVEMan uses a naïve Bayesian approach to estimate the posterior probability of each possible genotype (wild-type, germline, somatic mutation) at each base given the reference base and the predefined copy number status and proportion of tumour cells in the sample sequenced. To increase variant specificity several post processing filters as well as manual curation was applied to the initial set of CaVEMAN mutation calls. Briefly the spectrum of variant allele representation between forward and reverse reads and the range of positions in each read was evaluated as well as regions of low sequencing depth or poor sequence quality as previously described50. All substitutions were annotated to Ensembl version 58.

Variant detection - insertions, deletions and complex indels

A modified version of the PINDEL51 algorithm allowing for mapping of split-reads was using either one or both reads as an anchor whilst evaluating the second read through a series of split mappings was used for identifying the presence of indels. All putative indel calls were further filtered on the basis of coverage (minimum of 3 reads supporting a call), orientation (at least one read in each direction must report the call), local sequence context (variant length < = 4 within a sequence were the variant motif is repeated up to 9 times) and with no more than 5% of normal reads reporting the indel variant. All indels were annotated to Ensembl version 58.

Variant detection - Structural variation

Sequencing reads were mapped to the reference genome. Groups of at least 2 discordantly mapping paired-end reads by distance or orientation were identified using Brass (Breakpoint via assembly)20.

Putative structural variation was selected on the following criteria:

Groups of discordant mapping paired-end reads supported by at least 3 discordant reads;

Absence of discordant reads supporting the same variant in a panel of 45 in house control genomes;

Absence of discordant mapping paired-end reads that showed at least 20% homology on either side of structural variant breakpoints identified in the 1000 genomes sequenced by the 1000 genome Project Consortium;

Tandem duplications, intrachromosomal events and deletions greater than 1Kb in length;

Absence of alternative best mapping solution in the expected read pair position called using less stringent alignment parameters;

Absence of read clustering overlapping one of the paired read ends in the group indicative of misalignment due to repetitive or recurrent genomic sequences;

Groups of discordant mapping paired-end reads that are supported by segmentation of GC normalized copy number profiles.

Variant Validation- substitutions

Primers were designed to amplify 300-500bp fragments by conventional PCR for putative single nucleotide substitutions identified by exome sequencing. PCR amplification was performed for both tumour and remission DNA pairs and fragments were purified using SPRI bead clean up (Agencourt AMPure XP beads, Beckman Coulter, UK). A sample specific 8bp index tag was incorporated during amplification to allow subsequent de-convolution of sample origin in all recurrent variants. Individual pools of normal and tumour samples were prepared and subjected to 454 pyrosequencing (Roche, Branford, CT, USA). Sequencing data were aligned as previously described and targeted evaluation of sequence reads by chromosome, position and variant base was performed to confirm somatic status of reported variant.

Variant Validation- indels

Primers were designed to amplify 300-500bp fragments covering the genomic location of the identified indels. Following purification, DNA fragments were sequenced twice using the ABI Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems).

Variant Validation- structural variation

Primers mapping on either end of the reported structural variant in the appropriate orientation were designed and used by conventional PCR amplification on both tumour and remission DNA. PCR reactions were performed in duplicate and amplimers were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. Conventional Sanger sequencing of amplimers unique to tumour samples enabled breakpoint resolution to the base pair level. Sanger sequencing derived sequences were mapped to the reference genome and genomic breakpoints co-ordinates were characterized as well as annotated for the presence of microhomology, if homologous sequence was present in the respective 5′ and 3′ ends of the breakpoints, non-templated sequence (NTS) of 1 or more nucleotide bases were present in the breakpoint junction that did not map to the reference genome, or as clean blunt ends if the two breakpoints were continuous (Supplementary Figure 3).

Copy number and LOH analysis

Copy number analysis was performed using ASCAT (version 2.2)52 taking into account non-neoplastic cell infiltration and tumor aneuploidy, and resulted in integral allele-specific copy number profiles for the tumor cells. Allele-specific copy number estimates for point mutations and indels were obtained by integrating copy number and sequencing data.

PD4020 variant annotation

For PD4020a substitutions, we used Caveman parameters that have shown a positive predictive value of 92.1% in a recent panel of 21 breast cancer genomes20. We further utilized a panel of DNA from 250 in house unmatched normal samples to screen out variants in regions characterized by common sequencing artifacts. Variants present in 5 or more unmatched samples at a variant allele fraction greater than 5% were removed from the dataset.

V(D)J Score Calculations

Recombination signal sequence (RSS) motifs were scanned using a position weight matrix (PWM) with weights taken from RSS conservation table of Hesse et al17. Pseudocounts of 1 were used and log2 likelihood scores for the PWM were calculated using the background model of 20% background rate for C/G and 30% for A/T. Spacer lengths were scored using log2(relative affinity/optimal affinity) with the affinity values taken from Hesse et al17. The experimental distribution of resection lengths (number of bases deleted before the final rearrangement join) were collated from real resection data from Waanders et al, Tsai et al and Mullighan et al 9,16,18. Spacer lengths of 9bp-13bpp were allowed for 12-mer spacer and 20-25 for the 23-mer spacers. Resection lengths of −1 to −50 were allowed, and under the null model all resection lengths were given the same weight. Resection likelihood score for resection length l was defined as log2(relative observed resection length l frequency/null frequency). The PWM, spacer and resection log scores were treated as independent and for each breakpoint, both strands were searched for the best scoring motif defined as the sum of the three above scores. To validate the RSS assignment 26 structural variants mapping to known targets of physiological V(D)J recombination were evaluated, successfully annotating the presence of a canonical RSS motif for 24 of the 26 variants (Sensitivity= 92.3%). Furthermore, three sets of experimentally validated somatic rearrangements from a breast cancer study20, a pancreatic cancer study21 and a prostate cancer study22 were used as control data. The RSS scores were calculated for these two datasets and an FDR > 0.01 corresponding to an RSS score of 8.55 was used as a score cutoff for calling RSS motifs from ALL rearrangements.

Motif search for CpGpC or CpG sequences or either of the proposed AID motifs16 (WRYC, RGYW, WGCW) was also performed in parallel for all resolved breakpoints. Agnostic repetitive un-gapped motif analysis was performed using standard MEME23 parameters across 20bp sequence fragments spanning the breakpoint junctions of all confirmed structural variants in the dataset. The limit of output motifs was raised to 15 and the 3 most significant in each subset are presented. MEME analysis was also performed for the Breast and Pancreas dataset as described.

Chromatin state annotation of ETV6-RUNX1 ALL SVs

Chromatin segmentation profiles were generated using the ENCODE annotation for GM12878. Each breakpoint junction was annotated for the respective segmentation using the intersect and match functions of the R package G-Ranges. Appreciating that each joining end at a breakpoint junction is associated with an independent chromatin state, each breakpoints was annotated independently to one of the 15 Chromatin states as defined by the encode segmentation map.

Relative genomic segment representation was normalized to the proportion of each genomic segment in GM12878 by calculating the effect size of the number of structural variants in each chromatin segment over the total structural variants identified in the study to the proportion of each chromatin segment in the genome. The same calculations were performed for the control breast cancer and metastatic pancreatic cancer using the HMMHMec epithelial cell line as provided by Encode.

Analysis of SV distribution by chromatin state

Should SVs formation be random one would expect that the total number of SVs in each chromatin state to be reflective of the relative length of that genome state. To derive values for the null hypothesis of a random distribution of SVs across the genome we calculated the proportion of each chromatin state in the annotated genome. For example in GM12878 72.6% of the genome is annotated as Heterochromatin, whereas Active Promoters occupy less than 1% of the genome (0.78%). To evaluate if the overall distribution of SVs in each study is different to what one would expect under a null model we compared the proportion of SVs mapping to each chromatin state to the relative proportion of the chromatin state in the tissue defined reference genome. This was performed for both the total SVs in the present study as well as the total SVs within each class (SVs with resolved breakpoints, SVs with resolved breakpoints and a RSS signature, SVs with resolved breakpoints with no RSS signature) that maps within each chromatin state. We performed the same for the breast cancer, pancreatic cancer dataset as well as the hypodiploid ALL set. This analysis was not possible for prostate cancer due to unavailability of a chromatin segmentation map for prostate tissue.

To test whether the observed distribution of rearrangements was different from that expected by chance, we used Pearson’s goodness of fit tests. Essentially, the expected proportions of rearrangements falling in each chromatin state under the null hypothesis were taken from the fraction of base-pairs registered in each category from the genome-wide ENCODE data of the matching normal cell type. All data were downloaded from UCSC genome browser.

Biological relevance of identified mutations and structural rearrangement

Variants in known cancer genes were annotated as per an established reference of cancer genes from the Cancer Gene Census, known to be recurrently mutated by base substitutions and indels and thought to contribute to cancer development. Variants that conformed to the well-recognised patterns of cancer-causing mutations for each cancer gene were annotated as ‘oncogenic’. For example, for recessive cancer genes or known tumor suppressors, truncating mutations and essential splice site mutations were annotated as oncogenic. Missense mutations were included where they had been seen previously or conformed to the known pattern of missense mutation clusters previously reported for each gene in the COSMIC database.

All SVs in study were cross-referenced with a table of common regions of LOH as well as fragile sites as defined by a meta-analysis of SNP array data derived from 2,218 primary tumours from 12 human cancers (Cheng J, Wedge DC, Pitt JJ, Russnes HG, Vollan HKM et al, manuscript submitted).

Deciphering Signatures of Mutational Processes

Mutational signature analysis was performed using our previously developed theoretical model and its corresponding computational framework53. Briefly, we converted all mutation signature data from the exome dataset into a matrix that is made up of 96 features comprising mutations counts for each mutation type (C>A, C>G, C>T, T>A, T>C, T>G) using each possible 5′ and 3′ context for all samples in the exome study. The algorithm deciphers the minimal set of mutational signatures that optimally explains the proportion of each mutation type and then estimates the contribution of each signature to each sample.

Significance of acquired somatic mutations in study

To evaluate at each gene whether the frequency of missense, nonsense and splice site mutations was higher than expected by chance, we used an adaptation of the method as described previously54. Briefly, the rate of mutations is modeled as a Poisson process, with a rate given by a product of the mutation rate and the impact of selection. In particular, we use 12 parameters to describe the different rates of the 12 possible single nucleotide substitutions, 2 parameters to better account for the CpG effect on C>T transitions in each strand, and 3 selection parameters to measure the observed-over-expected ratio of missense (wMIS), nonsense (wNON) and essential splice site (wSPL) mutations. For example, the expected number of A>C missense mutations is modeled as: ratemisA>C = (t)*(AtoC)*(wMIS)*(LmisA>C), LmisA>C being the number of sites that can suffer a missense A>C mutation (which is calculated for any particular sequence). “t” refers to the overall mutation rate or the density of mutations. The likelihood of observing nmisA>C missense A>C mutations given the expected ratemisA>C is then calculated as Lik = Pois(nmisA>C|ratemisA>C). The likelihood of the entire model is the product of all individual likelihoods. This allows us to quantify the strength of selection while avoiding the confounding effect of gene length, sequence composition and different rates of each substitution type. To obtain accurate estimates of the relative rates of each substitution type, the 14 rate parameters were estimated from the entire collection of mutations. These rates are shared by all genes and maximum-likelihood estimates for “wMIS”, “wNON” and “wSPLICE” are obtained for each gene. Likelihood Ratio Tests are then used to test deviations from neutrality (wMIS = 1, wNON = 1 or wSPL = 1). Owing to the limited number of mutations, mutation rates were assumed constant among genes but an additional Likelihood Ratio Test was performed for each gene to detect violations of this assumption (comparing the observed number of synonymous mutations to the assumed mutation rate). No gene was found to deviate significantly from its estimated mutation rate in this dataset (q>0.05 for all genes). For Indels we test for significant enrichment of indel recurrence within gene coding sequences compared to the expected background rate, under a uniform distribution model. Interactions between mutations were assessed to determine any co-dependence or mutual exclusivity using previously described methods54. Results for all validated substitutions are shown in Supplementary Table 6.

Chromatin binding protein motif enrichment in ETV6-RUNX1 ALL rearrangements

In order to control for the effect of differential rearrangement rates within varying chromatin states, the rearrangement rate per MB, qi, was calculated as ni × 1000000/si, where ni and si are, respectively, the number of rearrangements that fall within a region with chromatin state i and the total number of bp throughout the genome in chromatin state i. For each of 75 chromatin binding proteins (CBPs) or chromatin modifications, the expected number of rearrangement breakpoints that would fall within the binding sites of that CBP, E(rj) is then given by

where si,j is the amount of DNA within the binding sites of chromatin binding protein j identified by ENCODE as having chromatin state i. Assuming a Poisson distribution, the probability that the observed number of rearrangements within the binding sites of a CBP, rj,obs, was greater than expected by chance was then given by

Analysis was separately performed on (i) all rearrangement breakpoints (ii) rearrangement breakpoints with a RAG signature. For CBPs with technical replicates we evaluated each replicate individual as well as a more stringent subset comprised of intersect of the two technical replicates. False discovery rates were calculated using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure55, after which H3K4me3 was the only CBP found to have an enrichment of rearrangements within its binding sites.

Single cell labeling, flow sorting and analysis

Patient samples were thawed from liquid nitrogen stored cryovials and stained using carboxyfluorescin diacetate, succinimidyl ester (CFSE). CFSE is an in vivo cell viability tracer that passively diffuses into cells and only fluoresces once intracellular esterases cleave the acetyl groups from the compound. Single cell sorting was performed on a BDFACSAria1-SORP instrument (BD®, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) equipped with an automated cell deposition unit using the following settings: 100micron nozzle, 1.4bar sheath pressure, 32.6KHz head drive and a flow rate that gave 1-200 events per second. Cell selection by forward-scattered light (FSC) and side-scattered light (SSC) accounted for cell size and internal complexity allowing accurate selection of single cells avoiding doublets and clumps. This novel approach for single cell multiplex quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) analysis was followed according to Potter N E, et al. submitted. Briefly, single cells were sorted directly into lysis buffer and lysed. Specific (DNA) target amplification (STA) was then performed before Q-PCR. This multiplex STA reaction involves the simultaneous amplification of all target regions of interest using custom designed Taqman assays for patient specific mutations. Genotyping assays for the mutations of interest were custom designed according to manufacturer’s guidelines. The STA product was then diluted prior to Q-PCR interrogation using the 96.96 dynamic microfluidic array and the BioMark™ HD (Fluidigm, UK) as recommended by the manufacturer. Detailed methods can be found in Potter et al30.

V(D)J analysis

To determine the status of V(D) J recombination for the samples in the study we used the 21 BIOMED-2 primers56, and for each sample in the study performed 20 independent PCR. PCR analysis corresponding to the V(D)J segments with the brightest band where independently validated with a second PCR reaction using the reaction conditions as detailed in the BIOMED-2 protocol.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Kay Kendall Leukaemia Fund (grant reference KKL407), the Leukemia and Lymphoma Research (grant reference 11021) and the Wellcome Trust (grant reference 077012/Z/05/Z). PJC is personally funded through a Wellcome Trust Senior Clinical Research Fellowship (grant reference WT088340MA). PVL is supported by a postdoctoral research fellowship of the Research Foundation-Flanders (FWO). SNZ is a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Clinical Fellow (grant reference WT100183MA). FVD is funded by the KKLF (grant reference KKL417). JZ is supported by University Hospital Motol MH-CR DRO 00064203 grant, Prague, Czech Republic.

Footnotes

ACCESSION NUMBERS

The raw sequencing data are available through the European Genome-phenome Archive (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ega/ Accession Numbers: EGAD00001000634, EGAD00001000635, EGAD00001000636).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bhojwani D, et al. ETV6-RUNX1-positive childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: improved outcome with contemporary therapy. Leukemia: official journal of the Leukemia Society of America, Leukemia Research Fund, U.K. 2012;26:265–270. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greaves MF, Wiemels J. Origins of chromosome translocations in childhood leukaemia. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2003;3:639–649. doi: 10.1038/nrc1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mori H, et al. Chromosome translocations and covert leukemic clones are generated during normal fetal development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:8242–8247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112218799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bateman CM, et al. Acquisition of genome-wide copy number alterations in monozygotic twins with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115:3553–3558. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-251413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mullighan CG, et al. Genome-wide analysis of genetic alterations in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2007;446:758–764. doi: 10.1038/nature05690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang M, Swanson PC. V(D)J recombinase binding and cleavage of cryptic recombination signal sequences identified from lymphoid malignancies. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:6717–6727. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710301200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mullighan CG, et al. Genomic analysis of the clonal origins of relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science. 2008;322:1377–1380. doi: 10.1126/science.1164266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raschke S, Balz V, Efferth T, Schulz WA, Florl AR. Homozygous deletions of CDKN2A caused by alternative mechanisms in various human cancer cell lines. Genes, chromosomes & cancer. 2005;42:58–67. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waanders E, et al. The origin and nature of tightly clustered BTG1 deletions in precursor B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia support a model of multiclonal evolution. PLoS genetics. 2012;8:e1002533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmfeldt L, et al. The genomic landscape of hypodiploid acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nature genetics. 2013 doi: 10.1038/ng.2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hubner S, et al. High incidence and unique features of antigen receptor gene rearrangements in TEL-AML1-positive leukemias. Leukemia: official journal of the Leukemia Society of America, Leukemia Research Fund, U.K. 2004;18:84–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schatz DG, Swanson PC. V(D)J recombination: mechanisms of initiation. Annual review of genetics. 2011;45:167–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fugmann SD, Lee AI, Shockett PE, Villey IJ, Schatz DG. The RAG proteins and V(D)J recombination: complexes, ends, and transposition. Annual review of immunology. 2000;18:495–527. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komori T, Okada A, Stewart V, Alt FW. Lack of N regions in antigen receptor variable region genes of TdT-deficient lymphocytes. Science. 1993;261:1171–1175. doi: 10.1126/science.8356451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raghavan SC, Swanson PC, Ma Y, Lieber MR. Double-strand break formation by the RAG complex at the bcl-2 major breakpoint region and at other non-B DNA structures in vitro. Molecular and cellular biology. 2005;25:5904–5919. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.14.5904-5919.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsai AG, et al. Human chromosomal translocations at CpG sites and a theoretical basis for their lineage and stage specificity. Cell. 2008;135:1130–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hesse JE, Lieber MR, Mizuuchi K, Gellert M. V(D)J recombination: a functional definition of the joining signals. Genes & development. 1989;3:1053–1061. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.7.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mullighan CG, et al. BCR-ABL1 lymphoblastic leukaemia is characterized by the deletion of Ikaros. Nature. 2008;453:110–114. doi: 10.1038/nature06866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang J, et al. The genetic basis of early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2012;481:157–163. doi: 10.1038/nature10725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nik-Zainal S, et al. Mutational processes molding the genomes of 21 breast cancers. Cell. 2012;149:979–993. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell PJ, et al. The patterns and dynamics of genomic instability in metastatic pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2010;467:1109–1113. doi: 10.1038/nature09460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baca SC, et al. Punctuated evolution of prostate cancer genomes. Cell. 2013;153:666–677. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bailey TL, Williams N, Misleh C, Li WW. MEME: discovering and analyzing DNA and protein sequence motifs. Nucleic acids research. 2006;34:W369–373. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stephens PJ, et al. Complex landscapes of somatic rearrangement in human breast cancer genomes. Nature. 2009;462:1005–1010. doi: 10.1038/nature08645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berger MF, et al. The genomic complexity of primary human prostate cancer. Nature. 2011;470:214–220. doi: 10.1038/nature09744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dunham I, et al. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stephens PJ, et al. Massive genomic rearrangement acquired in a single catastrophic event during cancer development. Cell. 2011;144:27–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shimazaki N, Tsai AG, Lieber MR. H3K4me3 stimulates the V(D)J RAG complex for both nicking and hairpinning in trans in addition to tethering in cis: implications for translocations. Molecular cell. 2009;34:535–544. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson K, et al. Genetic variegation of clonal architecture and propagating cells in leukaemia. Nature. 2011;469:356–361. doi: 10.1038/nature09650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Potter NE, et al. Single cell mutational profiling and clonal phylogeny in cancer. Genome research. 2013 doi: 10.1101/gr.159913.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Familiades J, et al. PAX5 mutations occur frequently in adult B-cell progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia and PAX5 haploinsufficiency is associated with BCR-ABL1 and TCF3-PBX1 fusion genes: a GRAALL study. Leukemia: official journal of the Leukemia Society of America, Leukemia Research Fund, U.K. 2009;23:1989–1998. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kempski H, et al. An investigation of the t(12;21) rearrangement in children with B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia using cytogenetic and molecular methods. British journal of haematology. 1999;105:684–689. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Delft FW, et al. Clonal origins of relapse in ETV6-RUNX1 acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2011;117:6247–6254. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-314674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hurlin PJ, Steingrimsson E, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Eisenman RN. Mga, a dual-specificity transcription factor that interacts with Max and contains a T-domain DNA-binding motif. The EMBO journal. 1999;18:7019–7028. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.24.7019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;368:2059–2074. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen S, et al. Novel non-TCR chromosome translocations t(3;11)(q25;p13) and t(X;11)(q25;p13) activating LMO2 by juxtaposition with MBNL1 and STAG2. Leukemia: official journal of the Leukemia Society of America, Leukemia Research Fund, U.K. 2011;25:1632–1635. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jaffe JD, et al. Global chromatin profiling reveals NSD2 mutations in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nature genetics. 2013;45:1386–1391. doi: 10.1038/ng.2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harris RS, Petersen-Mahrt SK, Neuberger MS. RNA editing enzyme APOBEC1 and some of its homologs can act as DNA mutators. Molecular cell. 2002;10:1247–1253. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00742-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neuberger MS, Rada C. Somatic hypermutation: activation-induced deaminase for C/G followed by polymerase eta for A/T. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2007;204:7–10. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alexandrov LB, et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013;500:415–421. doi: 10.1038/nature12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roberts SA, et al. Clustered mutations in yeast and in human cancers can arise from damaged long single-strand DNA regions. Molecular cell. 2012;46:424–435. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roberts KG, et al. Genetic alterations activating kinase and cytokine receptor signaling in high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer cell. 2012;22:153–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsai AG, Lieber MR. RAGs found “not guilty”: cleared by DNA evidence. Blood. 2008;111:1750. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-113381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boubakour-Azzouz I, Bertrand P, Claes A, Lopez BS, Rougeon F. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase requires KU80 and XRCC4 to promote N-addition at non-V(D)J chromosomal breaks in non-lymphoid cells. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40:8381–8391. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hong D, et al. Initiating and cancer-propagating cells in TEL-AML1-associated childhood leukemia. Science. 2008;319:336–339. doi: 10.1126/science.1150648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsuzuki S, Seto M, Greaves M, Enver T. Modeling first-hit functions of the t(12;21) TEL-AML1 translocation in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:8443–8448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402063101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ross ME, et al. Classification of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia by gene expression profiling. Blood. 2003;102:2951–2959. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kozarewa I, et al. Amplification-free Illumina sequencing-library preparation facilitates improved mapping and assembly of (G+C)-biased genomes. Nature methods. 2009;6:291–295. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:589–595. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Varela I, et al. Exome sequencing identifies frequent mutation of the SWI/SNF complex gene PBRM1 in renal carcinoma. Nature. 2011;469:539–542. doi: 10.1038/nature09639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ye K, Schulz MH, Long Q, Apweiler R, Ning Z. Pindel: a pattern growth approach to detect break points of large deletions and medium sized insertions from paired-end short reads. Bioinformatics. 2009 doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van Loo P, et al. Allele-specific copy number analysis of tumors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:16910–16915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009843107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, Campbell PJ, Stratton MR. Deciphering signatures of mutational processes operative in human cancer. Cell reports. 2013;3:246–259. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Greenman C, Wooster R, Futreal PA, Stratton MR, Easton DF. Statistical analysis of pathogenicity of somatic mutations in cancer. Genetics. 2006;173:2187–2198. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.044677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Klipper-Aurbach Y, et al. Mathematical formulae for the prediction of the residual beta cell function during the first two years of disease in children and adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Medical hypotheses. 1995;45:486–490. doi: 10.1016/0306-9877(95)90228-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Dongen JJ, et al. Design and standardization of PCR primers and protocols for detection of clonal immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor gene recombinations in suspect lymphoproliferations: report of the BIOMED-2 Concerted Action BMH4-CT98-3936. Leukemia: official journal of the Leukemia Society of America, Leukemia Research Fund, U.K. 2003;17:2257–2317. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.