Key messages

It is possible to create a system for diabetes care that ensures follow up in the community rather than in hospital. Doing this in a way that keeps all relevant organisations engaged was helped by facilitated participation in the co-construction of the new system. This approach could be successfully used to continually improve the shared care system for diabetes and also to develop shared care for other conditions.

Why this matters to me

As a carer for an elderly lady with diabetes, a number of complications of diabetes and comorbidities, and a family at risk of diabetes, I have often experienced the difficulties that people with diabetes face in navigating the healthcare system. With sometimes conflicting advice from healthcare professionals, leaving appointments confused and unsure who to turn to for advice, I have often had to step in and help clear up some of the confusion. Seeing the sometimes easy solutions that would simplify health-care on behalf of the patient became important for me. As a commissioner I was in a position to affect change.

Keywords: diabetes, integrated care, long-term conditions, shared care

Abstract

We describe four stages of an initiative to co-create a shared care system to treat patients with diabetes out of hospital and in the community.

Introduction

Ealing has a population of 390 000, 20% of the population of north-west London. It has around 20% of all diabetics in west London (19 600/98 000) and there are pockets where the prevalence is higher. Southall is home to 40% of Ealing diabetics despite having only 30% of the Ealing population. Ealing has the highest rates of emergency admission in London for hypoglycaemia and ketoacidosis, and a low rate of retinopathy screening (71%). Programme Budgeting Marginal Analysis shows diabetes care falls within the Low Cost–Worst Outcomes box.

The problem will get worse and the cost of care for diabetes seems certain to rise; 6.5% of the Ealing population are known to have diabetes, but the true prevalence is calculated to be 8.6% and this is expected to increase to 9.9% by 2020 as a result of the ageing population and rise in obesity levels.

The cost of care for other long-term conditions is similarly rising – improved detection and survival are increasing the cost of care for dementia, cancer, heart and lung conditions. But National Health Service (NHS) resources are reducing. This makes it essential that we create new, more cost-effective ways of using NHS resources for these conditions.

Improving diabetes care is a priority for the Ealing Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) because diabetes control is poor (high HbA1C levels), and primary care lacks the ability to manage diabetes systematically and comprehensively. Ealing CCG recognises the need to improve diabetes care because it will have a knock-on effect on a number of other long-term conditions.

In Ealing, we have been developing a model that systematically develops and supports shared care for diabetes – teamworking across disciplinary and organisational boundaries that avoids duplication, synchronises efforts, quickly accesses specialist knowledge and helps patients to help themselves.

Since 2009, we have been piloting different aspects of the shared care model, mindful that it might be later adapted to all long-term conditions. This paper describes our progress with transforming the whole system of diabetes care towards shared care and on-going collaborative improvements.

Stages of developing a model of shared care for diabetes

Stage one: pilot work, 2009–2011

The Southall Initiative for Integrated Care (2009–2011) was designed to bring together practitioners from different disciplines and organisations, to think through the challenges that Southall faced in delivering improvements in clinical outcomes. Following a detailed needs analysis, four issues were identified that required long-term collaboration and co-ordination between primary care teams and four different sectors or agencies: (1) dementia (social care); (2) anxiety and depression (mental health); (3) patient advocacy (public health); and (4) diabetes, the focus of this paper.

The Southall Initiative divided the 26 general practices in Southall into four localities (approximately 15 000 population, 6–8 practices), each to lead on one of the four issues. Through a series of connected workshops, participants from the relevant agencies worked together to identify ways to communicate and collaborate effectively between their agencies to co-create a better system of care.

The diabetes group worked with: (1) general practitioners (GPs), practice nurses, practice managers and administrative teams; (2) community services – community matrons, podiatry, dietetics; (3) acute teams – diabetes specialist nurses and diabetes consultants from the local hospital; (4) public health – health-promotion teams and statistics; (5) local authority – adult and children social services; and (6) voluntary groups. They held two large patient and public consultation events, with the help of Diabetes UK, to inform the commissioning plans.

They proposed a new system of community-based shared care for diabetes, influenced by the model being promoted by London Strategic Health Authority. This led to a detailed service specification that proposed the transfer of resources from acute to community care.

Stage two: policy, 2011–2012

At this stage, Ealing CCG was taking shape and a clinical lead (RC) was identified to work with the lead manager (NU) to build from the learning so far to define a diabetes strategy for Ealing. Over three months, the clinical lead interviewed partners and visited external agencies, to review local progress and compare with models from other places.

This led to:

a diabetes strategy, approved by Ealing CCG (December 2011). This described shared care that included: (1) tier 1 clinics (practice nurse-led within general practices) for the majority of patients; (2) tier 2 clinics (specialist-led clinics that serve geographic clusters of practices of approximately 50 000 population) for specialist review of some patients before being returned to follow-up in tier 1 clinics; (3) tier 3 (hospital care) for pregnant women, children and those who need review by combined consultant teams; and (4) real-time telephone advice for tier 1 practitioners given by diabetes specialist nurses to improve local quality and avoid referral

a diabetes redesign board with technical, clinical and commissioning work streams, each with objectives to co-ordinate and lead change throughout Ealing to create the infrastructure of leadership and data needed to support tier 1 and tier 2 care

active leadership by the CCG to engage all Ealing practices, hospital and community practitioners in the transformational process.

Stage three: Establishing structures, 2012

Health Networks

All practices in Ealing have now been organised into geographical areas of approximately 50 000 population (10–20 general practices) called Health Networks. This area is thought to be small enough to build local relationships, and large enough to have strategic commissioning impact (see accompanying paper in this issue). Each Health Network has a representative on the CCG Board.

Integrated Care Pilot

In August 2012, most Ealing practices agreed to participate in the Integrated Care Pilot (ICP).1 The ICP is a mechanism to build trust and facilitate collaborative improvements across multiple organisational boundaries. It revolves around twice-monthly case conferences within geographic (MDG) areas of approximately 50 000 population; we aligned the boundaries of Ealing's Health Networks to these MDG areas and appointed two co-chairs for each (14 in total) to lead collaborative improvements. Practitioners from different disciplines and organisations are paid to attend to discuss the care of patients who need multiple agency input (especially those with diabetes or who are elderly). They also devise innovations to improve whole systems of care (there is an Innovation Fund for Health Networks to apply). The anticipated reduction of hospital admissions pays for the ICP.

Care plans

The practices that engaged in the ICP are paid for each care plan they produce for people living with diabetes or who over the age of 75. This helps to improve the care of those individuals. It also helps to identify gaps in care and to co-ordinate the delivery of care. Care plans that pose difficult questions or have illustrative learning are discussed at the monthly ICP case conferences.

Specialist-led tier 2 clinic

The first was piloted in one Health Network in January 2012. A second was established in June 2012 and a third in December 2012. All seven Health Networks will have similar clinics by December 2013. Hospitals will continue to transfer patients into tier 2 or tier 1 clinics throughout 2013.

Generalist-led tier 1 clinics

In autumn 2012, a training course was run to help practices set up and run diabetes clinics. In December 2012, guidelines arising from this course were posted on the local ‘extranet’ (a website for local practitioners). Practices use the principles of ‘year of care’ – patients are given their results a week ahead of their review so they can have a good conversation with the tier 1 clinic practitioner about these results.

Stage four: developing sustainable processes, 2013+

Having established the basic structures for community-based care, we are now developing an annual schedule of events to engage a breadth of stakeholder in continuous quality improvements, using principles of experienced-based co-design. Like bus or train routes, we need to make the junctions where people come together as clear as possible and to connect with the annual planning cycles of partner organisations.2

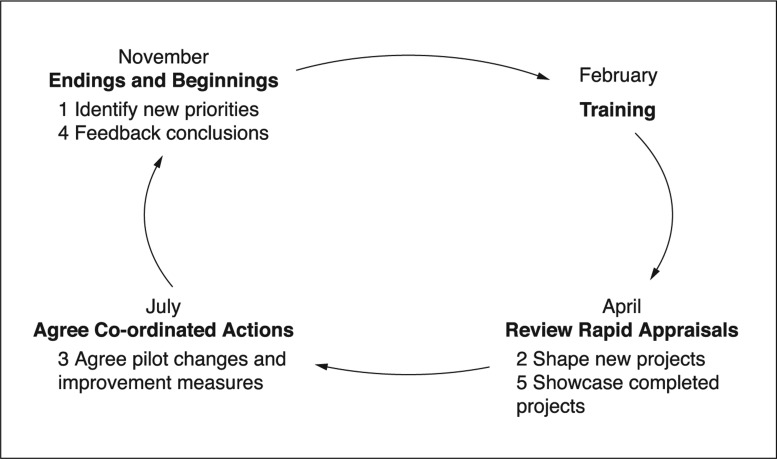

This annual cycle (Figure 1) allows all practitioners to understand and critique the system, learn about diabetes care and develop relationships across organisational boundaries.

Figure 1.

Annual cycle of interorganisational continuous quality improvement

It includes an autumn four-day training course on tier 1 diabetes clinics (with subsequent in-practice mentorship), a course for injectable treatments, collaborative learning events to co-ordinate improvement projects (spring), simultaneous, co-ordinated improvements between organisations (autumn) and three connected stakeholder workshops to co-design improvement projects (April, July and November). Priority projects and shared leadership teams are agreed at the November stakeholder conference to move innovations forward for a year or so before handing over to new teams.

Other features of the shared care system include:

a patient forum – acts as a critical friend of the diabetes strategy team and participates in the annual schedule of events

a telephone advice line for tier 1 clinicians to gain in-the-moment advice from tier 2 clinicians

patient-held records to support communication between generalists and specialists

patient self-help materials

an enhanced service for diabetes for lead practices for diabetes to ensure cohesion of the diabetes shared care system and initiate injectable treatments in Health Networks

monthly reports from routinely gathered data to compare monthly measures of cost and quality (e.g. hospital episodes) between all Health Networks

a routine mechanism (through the ICP peer review system) to evaluate patient and clinician satisfaction with the diabetes system of shared care

a directory of services for diabetes

establish a partnership with multiple universities to co-badge Health Networks as University Linked Localities3

develop relationships with case study sites outside Ealing to share insights about shared care for long-term conditions within Health Networks.

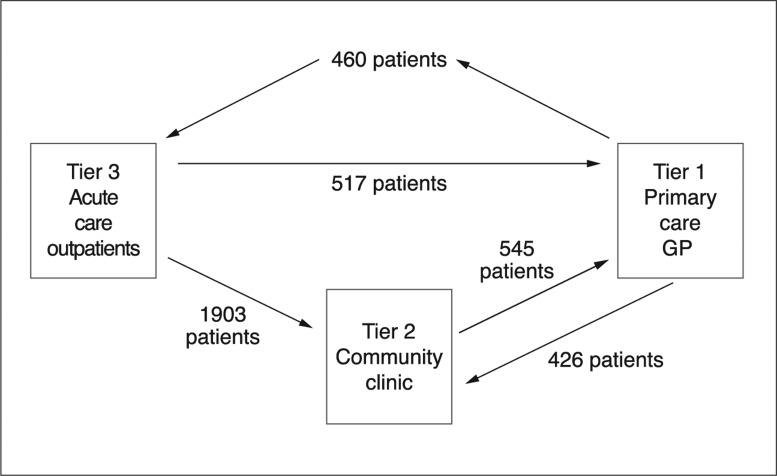

Improvement measures: transferring patients out of hospital into the community

Figures 2 and 3 show that between April and October 2012, of the 4000+ patients with diabetes being followed up at Ealing hospital, 1903 were transferred to community-based tier 2 diabetes clinics. Of these 1903 patients, 545 were then transferred to primary care for on-going tier 1 diabetes care. During the same period, a further 517 patients were transferred from acute-based outpatient care directly to primary care. In total, 2420 patients moved from hospital to community-based care (tier 2 clinics or tier 1 primary care) in those seven months. Some were ‘dormant’ patients who had not been seen in acute outpatients for over 12 months. In those same months, 426 patients were referred from tier 1 to tier 2 clinics.

Figure 2.

Diagram representing shifting settings of care

Figure 3.

Graph showing data of changed settings of care

Contributor Information

Neha Unadkat, Integrated Care Pilot Project Manager, NHS Ealing, UK.

Liz Evans, Project Manager, Ealing Clinical Commissioning Group, UK.

Laura Nasir, Tutor, Florence Nightingale School of Nursing & Midwifery, King's College, London, UK.

Paul Thomas, Clinical Lead, Ealing Clinical Commissioning Group & NHS Ealing, UK.

Raj Chandok, GP, Vice Chair, Ealing Clinical Commissioning Group, UK.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

This work was a service improvement project and did not require research ethics committee approval. It was approved and monitored by NHS Ealing and Ealing Clinical Commissioning Group. Ethical issues were considered by the Diabetes Redesign Group.

REFERENCES

- 1.Steeden A. The Integrated Care Pilot in north-west London. London Journal of Primary Care 2013;5(2). www.londonjournalofprimarycare.org.uk/articles/5872852.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bate P, Robert G. Experience-based design: from redesigning the system around the patient to co-designing services with the patient. Quality & Safety in Health Care 2006;15:307–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas P, Gnani S, Banarsee R. Achieving University Linked Localities through Health Networks. London Journal of Primary Care 2012;5(1):12–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]