Question

How can GP consortia lead the development of integrated musculoskeletal services?

Key messages

Musculoskeletal conditions are common in primary care and are associated with significant comorbidity and impairment of quality of life.

An integrated care approach, with most patients being managed in primary care and community settings, whilst providing clear and fast routes to secondary care, provides an effective and cost-effective solution compared with traditional models.

GP consortia, in conjunction with strong clinical leadership, inbuilt organisational and professional learning, and a GP champion, are well placed to deliver service redesign by co-ordinating primary care development, local commissioning of community services, and the acute commissioning vehicles responsible for secondary care.

Why this matters to me

I authored the first review of musculoskeletal services available for GPs in Ealing in 1994. Three reviews and 16 years later, progress has been frustratingly slow. GP consortia put clinicians in the driving seat, leading service design and steering a path to improved services for patients. Back pain is the leading single presentation of musculoskeletal problems in General Practice. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) estimates that about 50% of back pain patients, accounting for 30% of the cost of back pain treatments, seek private therapy (physiotherapy, osteopathy, chiropractic) because of inadequate NHS service provision. Musculoskeletal disorders are the second highest cause of time lost from work and have worse quality of life scores than cancer, mental health, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, visual and hearing impairment, and renal disease, which makes this a priority that needs championing.1 The government chose not to create a national clinical director for musculoskeletal services and community services were disconnected from acute services by the creation of acute commissioning vehicles. Only by creating an integrated service, led by GP consortia, can cohesive services and coherent pathways be developed. In a time of financial constraint, such service redesign will create extra capacity by the virement of funds from secondary to primary and community care. This will enable the patient to be seen in the right place at the right time by the right clinician.

Keywords: delivery of health care, integrated, musculoskeletal system, primary health care

Abstract

Background Musculoskeletal conditions are common in primary care and are associated with significant co-morbidity and impairment of quality of life. Traditional care pathways combined community-based physiotherapy with GP referral to hospital for a consultant opinion. Locally, this model led to only 30% of hospital consultant orthopaedic referrals being listed for surgery, with the majority being referred for physiotherapy. The NHS musculoskeletal framework proposed the use of interface services to provide expertise in diagnosis, triage and management of musculoskeletal problems not requiring surgery. The White Paper Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS has replaced PCT commissioning with GP consortia, who will lead future service development.

Setting Primary and community care, integrated with secondary care, in the NHS in England.

Question How can GP consortia lead the development of integrated musculoskeletal services?

Review: The Ealing experience We explore here how Ealing implemented a ‘See and Treat’ interface clinic model to improve surgical conversion rates, reduce unnecessary hospital referrals and provide community treatment more efficiently than a triage model. A high-profile GP education programme enabled GPs to triage in their practices and manage patients without referral.

Conclusion In Ealing, we demonstrated that most patients with musculoskeletal conditions can be managed in primary care and community settings. The integrated musculoskeletal service provides clear and fast routes to secondary care. This is both clinically effective and cost-effective, reserving hospital referral for patients most likely to need surgery. GP consortia, in conjunction with strong clinical leadership, inbuilt organisational and professional learning, and a GP champion, are well placed to deliver service redesign by co-ordinating primary care development, local commissioning of community services and the acute commissioning vehicles responsible for secondary care. The immediate priority for GP consortia is to develop a truly integrated service by facilitating consultant opinions within a community setting.

Background

Prevalence

In the UK, 16.5 million people have back pain,2 8.5 million people have peripheral joint pain,3 4.4 million have moderate or severe osteoarthritis3 and 650 000 have inflammatory arthritis.4 Twenty percent of the population present to GPs each year with a new onset or recurrence of a musculoskeletal problem5 and 10% of the population are referred from General Practice each year to community or secondary care with musculoskeletal problems.6

Impact, quality of life and co-morbidity

In total, 11.2 million working days per year are lost through musculoskeletal problems and these constitute the second largest group of patients in receipt of incapacity benefits (after mental ill-health).7 Musculoskeletal conditions were associated with the worst quality of life scores when compared with a basket of conditions in 15 000 people. The comparators included: mental health, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, visual and hearing impairment, renal disease and cancer.8 Twenty-seven percent of patients in primary care with chronic musculoskeletal pain have major depressive symptoms, often unrecognised,9 and conversely, 41% of patients with major depression have disabling chronic pain.10

Cost

NHS expenditure on musculoskeletal disorders was £4.2 billion in 2008–2009. This is the fifth highest area of spend in the NHS, and has a separately identified programme budget from the Department of Health.11

Interface clinics

An Interface Service is ‘any service (excluding consultant-led services) that incorporates any intermediate levels of triage, assessment and treatment between traditional Primary Care and Secondary Care’.12 The Musculoskeletal Services Framework (MSF) advised that many patients with musculoskeletal problems could receive faster and more appropriate care in the community, with reduced waiting times to start active management.13 Equally important, by diverting patients to community services, waiting times for those patients requiring surgery would also be reduced. Interface clinics were promoted to provide assessment, diagnosis and treatment in the community. Integrated care pathways were suggested to allow referral back to GPs, to other community services or on to secondary care using locally agreed evidence-based guidelines. The MSF stated the need for strong leadership, robust clinical governance, accountability and integrated collaboration with primary and secondary care clinicians. Some Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) in West London adopted a community-based triage service staffed by extended scope physiotherapists. Ealing implemented a ‘See and Treat’ model with similar aims, and with the potential to generate greater efficiencies.

Shared leadership

Shared leadership is where leadership is not restricted to people who hold designated leadership roles, and where there is a shared sense of responsibility for the success of the organization and its services.14 In Ealing, the Musculoskeletal Core Strategy Group utilises shared leadership for the benefit of the organisation by defining goals, motivating musculoskeletal service staff and GPs, inspiring change, mapping processes and maintaining good communications.

GP confidence and musculoskeletal training

British undergraduate training in musculoskeletal conditions has been meagre, resulting in poor confidence among GPs in diagnosing and managing musculoskeletal conditions.15 This may be a significant factor contributing to referrals to secondary care for patients who could be managed conservatively in the community.15 The Ealing postgraduate tutors supported a rolling musculoskeletal education programme, delivered by Ealing and Harrow Community Services, ensuring funding for the programme and for training facilitators.

‘Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS’

The government White Paper published in 2010 provides new opportunities for commissioning services.16 The White Paper signals a shift in decision-making to clinicians close to patients. ‘Commissioning by GP consortia will mean that the redesign of patient pathways and local services is always clinicallyled and based on more effective dialogue and partnership with hospital specialists.’16 In Ealing, these changes will provide impetus to develop a fully integrated musculoskeletal service, not least because of the high prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions in primary care.

The Appendix considers how the NHS Operating Framework 2011/12,17 the NHS Outcomes Frame-work 2011/1218 and the Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention (QIPP) Agenda19 pertain to commissioning musculoskeletal services by GP consortia. The Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance (ARMA) is concerned, however, that the direction of the quality standards in the NHS Outcome Frame-work will focus commissioners' attention away from musculoskeletal conditions, ‘… if it isn't measured, it won't be managed’.20

Our experience in developing the Musculoskeletal Interface Service in Ealing helps answer the question: How can GP consortia lead the development of integrated musculoskeletal services?

Setting

Primary and community care, integrated with secondary care, in the NHS in England.

In the ‘See and Treat’ model implemented in Ealing, triage occurs at the point of GP referral. The referring GP chooses either general physiotherapy, interface clinics or secondary care. This decision is supported by referral guidance distributed to all GPs and by the musculoskeletal education programme described below. For patients seen in the general physiotherapy or interface clinics, there is no further triage other than a paper-based triage for urgent referrals. Patients start their definitive treatment with the first therapist they see, reducing referral-to-treatment times. Patients can be internally referred between any stream, or to classes or secondary care.

The Ealing PCT central booking service handles 13 000 GP referrals per year for general physiotherapy and 9000 for the interface services; a total of 22 000 GP referrals per year to the community services. A further 11 000 musculoskeletal referrals per year from GPs directly to hospital are triaged by a separate GP-led paper/electronic-based triage system: the Clinical Assessment Service (CAS). The CAS GPs have in-service training provided by the musculoskeletal service and they can request email advice. This maintains the GPs' independence in the referral process. Currently, 15% of CAS referrals to orthopaedics are discussed by fax with referring GPs, with formative advice to consider diversion to the community musculoskeletal service.

Current waiting times are: general physiotherapy, 11 weeks; interface clinics, 2–4 weeks; urgent referrals, 1–2 weeks. Using a cost per case model, interface clinic treatments were 32–40% cheaper than secondary care tariffs providing the same treatments.21 Full descriptions of the musculoskeletal service21 and referral pathways22 have been published.

Methods

Audit reports and verification of outpatient attendances and surgical conversion rates were performed using CSE Servelec RiO® Data Warehouse Reports Manager and Dr Foster Intelligence, Practice and Provider Monitor (PPM) Tool®.

Evidence and review: the Ealing experience

Core strategy group

The Musculoskeletal Core Strategy Group was formed in Ealing in 2003. The core group consists of a commissioner with special responsibility for musculoskeletal service development, the clinical lead and the associate director of the musculoskeletal provider services, and the PCT musculoskeletal clinical advisor/GP clinical champion for musculoskeletal conditions. This is an informal group that generates ideas and evaluates current and future service provision; focusing on improving outcomes for patients with musculoskeletal conditions, within an ethical framework.1 This group worked with constituent GP practice-based commissioning groups to adopt a single provider across the PCT (2005), with accompanying economies of scale; consolidated the interface clinic (2006); developed common referral guidelines (2009); and is drafting unified patient pathways across primary and secondary care.

Musculoskeletal service commissioning

Input into commissioning local musculoskeletal services occurs in five ‘layers’:

a dedicated musculoskeletal commissioner

the Musculoskeletal Core Strategy Grou

the practice-based commissioning musculoskeletal leads

Ealing PCT commissioning the community provider (Ealing and Harrow Community Services)

the North West London Acute Commissioning Vehicle.

The Ealing PCT musculoskeletal clinical advisor liaises with all the layers to ensure coherent commissioning that is informed by national guidance and clinical evidence. This liaison is essential because patient pathways span primary care, community services and secondary care.

Musculoskeletal service provider

Integrating musculoskeletal care across primary care, community services and secondary care requires strong clinical leadership. The community physiotherapy and interface services are led by a consultant physiotherapist. This therapist-led service inspires the therapists to provide evidence-based care and improve clinical and cost-effectiveness. The musculoskeletal service provider has hosted network meetings with public health, social services and service users. The musculoskeletal interface service and mental health services are developing pathways for patients with co-morbidity and chronic pain.

Musculoskeletal education

Ealing and Harrow Community Services appointed an education lead, who holds a postgraduate certificate for teaching in primary care. The education lead instigated the multidisciplinary education programme for therapists and musculoskeletal physicians working in the interface clinics. The education lead has responsibility for musculoskeletal education for GPs, GP registrars and a new specialist training post in musculoskeletal medicine. The education programme is jointly funded by Ealing PCT, Ealing and Harrow Community Services and the London Deanery (for GP registrar teaching). A rolling programme of core skills and advanced musculoskeletal topics helps to improve GP confidence in diagnosis and in managing patients who do not need referral. This is a vital component of the ‘See and Treat’ model, which moves triage to GPs in their practices.

The interface clinicians provide feedback to GPs in discharge letters, emails or by telephone regarding the appropriateness of the referrals and with suggestions for further management, in accordance with local and national clinical evidence. Trends in feedback are used to inform the GP education programme and case discussions.

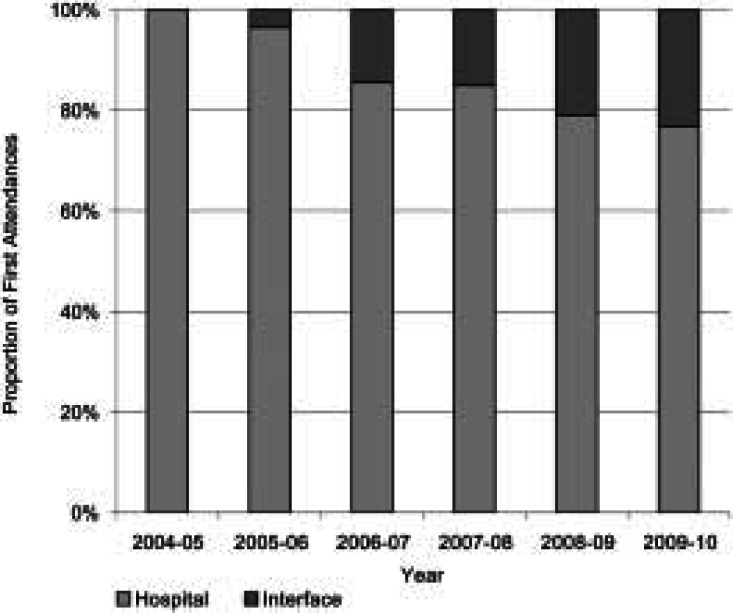

Outcomes

Figure 1 shows the proportion of specialist musculoskeletal opinions occurring in secondary care has fallen from 100% in 2005 to 73% in 2010 as GPs have referred to the interface service in preference to hospital. A further shift should be achievable with direct input from secondary care consultants in the interface clinics, as suggested by the Musculoskeletal Service Framework13 and the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement.23 The surgical conversion rate for onward referral from the interface service is 70%, compared with 30% for GP referral direct to secondary care (S Griffiths, personal communications: Ealing and Harrow Community Services and M Nyadzayo, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust). Data are verified using NHS number tracking, as per the Methods section.

Figure 1.

Proportion of first attendances: hospital orthopaedics and community musculoskeletal interface clinics (percentages per financial year, all referral sources). Sources: CSE Servelec RiO® Data Warehouse Reports Manager, Dr Foster Intelligence Practice and Provider Monitor Tool (PPM)®

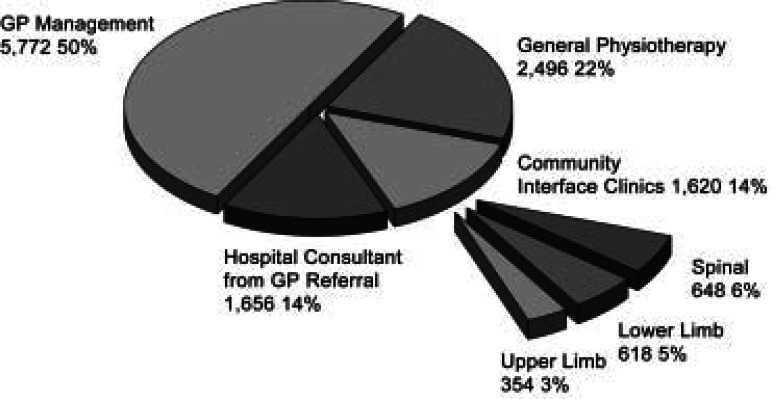

The introduction of referral guidance coupled with a high-profile GP education programme in 2009 led to a sustained 10% reduction in GP referrals into the musculoskeletal service, with inappropriate referrals now accounting for just 1% of the total. Figure 2 shows how GPs have referred or managed patients with musculoskeletal conditions in general practice using the ‘See and Treat’ model. The advantage of this model is that patients start their definitive treatment earlier. No further triage by the musculoskeletal service is performed for non-urgent referrals because the patient has been triaged by the GP before referral. The model demonstrates successful demand management by empowering GPs through education and feedback.

Figure 2.

GP management and GP referrals for musculoskeletal conditions (percentages and annual rates per 100 000 Population, Ealing PCT, 2009). Sources: CSE Servelec RiO® Data Warehouse Reports Manager, Dr Foster Intelligence Practice and Provider Monitor Tool (PPM)®, Ealing CAS Database, NICE Epidemiology Review

Table 1 shows how the Ealing PCT musculoskeletal interface clinics have performed against the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement musculoskeletal management indicators.23 The cost-effectiveness of the treatments offered meets the NICE threshold for funding NHS intervention.24

Table 1.

NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement Musculoskeletal Interface Performance Management Indicators (Ealing PCT interface clinic performance, December 2010). Source: CSE Servelec RiO® Data Warehouse Reports Manager

| Interface performance indicator | Outcome |

|---|---|

| 18 weeks Referral to Treatment data | Average referral to treatment time: 8 weeks (includes time for investigations before staring treatment.) |

| Appropriateness of referrals into service | 99% |

| Did not attend (DNA) rates | Initial appointment: 7% |

| Follow-up appointments: 15% | |

| Initial DNAs reduced from 10% in 2009 as waiting times have fallen. | |

| Text reminder service being piloted to reduce DNAs further. | |

| Number of new attendances and follow-ups | New patients: 4682 |

| Follow-ups: 7053 | |

| Average 2.5 visits per episode | |

| Treatments performed in the service and outcomes | Specific postural, stretching and strengthening exercises, manipulation, acupuncture, injections (soft tissue, joint and caudal epidural), FP10 prescriptions. |

| Treatments offered are clinically and cost-effective in accordance with NICE guidelines and NHS Evidence Clinical Knowledge Summaries. | |

| MYMOP2 outcome measure being piloted. | |

| Appropriateness of referrals to diagnostic tests such as MRI | New patients seen: 4682 |

| MRI scans requested: 551 | |

| MRI rate: 12% | |

| Radiology audit in 2007 showed that MRI scans were being requested in accordance with Royal College of Radiologists guidelines. | |

| Further audit on clinical appropriateness planned. | |

| Onward referral rates to secondary care | New patients seen: 4682 |

| Secondary care referrals: 455 | |

| Onward referral rate: 10% | |

| Surgical intervention rates within secondary care | 70%† |

| Capacity and demand monitoring | Block contract |

| 4682 patients/year (interface service) | |

| 6909 patients/year (general physiotherapy | |

| Service at capacity. | |

| Waiting times in steady state: interface clinics, 3 weeks; general physiotherapy, 11 weeks. General physiotherapy stream demand fell by 10% after introduction of referral guidelines in 2009. | |

| Turnaround time for diagnostics. | Blood tests and X-rays, 1 week; MRI Alliance, 2.5 weeks; MRI InHealth (spine) 2.5 weeks; MRI InHealth (peripheral) 3.5 weeks |

† Audit, S Griffiths, personal communication, 2010.

Musculoskeletal services are a low-cost, high-volume service accounting for a total expenditure of £45 per head of population compared with the total PCT expenditure of £1413 per head.25 This modest expenditure benefits 20 000 patients per year in Ealing.

Organisational learning

Clinicians from general practice, community physiotherapy and interface services, and hospital consultants have been in involved in organisational learning. Multidisciplinary teams explored what needed to change in different professional groups, particularly within the interface service and in general practice. The discussions were informed by data about referral patterns, treatments and outcomes. Clinicians collaborated to develop local evidence-based referral and investigation guidelines.22,26

Conclusion

In Ealing, we have demonstrated that 86% of patients presenting to GPs with musculoskeletal conditions can managed in primary care and community settings. The integrated musculoskeletal service provides clear and fast routes to secondary care for about one-fifth of the referrals received, with a surgical conversion rate of 70%. This is both clinically effective and cost-effective, reserving hospital referral for patients most likely to need surgery.

The immediate focus for the GP consortium in Ealing is to enable consultants from secondary care to work in the interface clinics. The total savings from moving work from secondary to primary care is small; financial modelling estimates this at £1 million recurrent savings per year. However, the benefits of consultant input into the interface clinics are significant: it strengthens the confidence of GPs to refer to the community clinics, there are educational benefits for the extended scope physiotherapists, and clinical governance is enhanced. Integrated care will facilitate patients seeing the most appropriate clinician and starting their definitive treatment sooner.

The boundaries for GP consortia, acute commissioning vehicles, integrated care organisations, and other providers are not co-terminus. GP consortia should consider whether it would be more efficient for one body to lead commissioning for integrated community and elective musculoskeletal care pathways on behalf of all commissioners in a sector.

GP consortia are in a position to commission for improving the quality of life for patients with musculoskeletal conditions. The Ealing PCT musculoskeletal service can offer transferrable experience to embryonic GP consortia. Two aspects of our current service should be carried forwards. First, strong clinical leadership, a core strategy group and a GP champion are essential for service transformation by coordinating primary care development, local commissioning of community services and the acute commissioning vehicles responsible for secondary care. Second, in-built organisational and professional learning for providers at every stage of the care pathway from general practice, community general physiotherapy and interface services to secondary care will be important to the longer term success of service redesign.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to acknowledge the help of the Musculoskeletal Core Strategy Group in preparing this paper and for permission to use audit data: Stephanie Griffiths and Neha Unadkat.

Appendix

In 2010, the government White Paper Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS proposed the formation of GP consortia to replace PCTs' responsibilities for commissioning in the NHS in England.a1 Three further documents have been published by the Department of Health, which add operational detail to the reconfiguration of the NHS outlined in the White Paper. This Appendix considers how The NHS Operating Framework 2011/12,a2 the NHS Outcomes Framework 2011/12a3 and the Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention (QIPP) Agendaa4 pertain to commissioning musculoskeletal services by GP consortia.

The NHS Operating Framework 2011/12

The NHS Operating Framework sets out how the NHS will improve quality for patients, by improving safety, effectiveness and patient experience.a2 The key national priorities for 2011/12 include maintaining performance on key waiting times, continuing to reduce healthcare associated infections, and reducing emergency readmission rates.

The operating framework measures that are relevant to commissioning musculoskeletal services (as distinct from acute trauma services) are:

to meet Referral to Treatment waits

to maintain patient choice, within a framework of PCT clusters.

There are a number of ‘supporting measures’ that will be monitored:

people with long term conditions feeling independent and in control of their condition

community activity

outpatient activity

follow-up ratios.

The NHS Outcomes Framework for 2011/12

The Department of Health envisages that the Outcomes Framework will provide national accountability for NHS performance, and will catalyse quality improvement through outcomes measurements.a3 The Outcomes Framework moves away from previous process targets, but is dependent on being able to define and then measure outcomes of relevance. To this end, NICE is producing a set of 150 quality standards to support the main pathways of patient care in the NHS. The Outcomes Framework also focuses on reducing health inequalities through the chosen outcome indicators.

The structure of the NHS Outcomes Framework is based on five domains. The most relevant to musculoskeletal conditions are:

domain 2 – enhancing quality of life for people with long-term conditions

domain 3 – helping people to recover from episodes of ill health or following injury.

Musculoskeletal conditions are heterogeneous. Most of these conditions affect quality of life, morbidity and loss of productivity, rather than mortality. Therefore, in contrast to cancer services, cardiovascular and respiratory conditions, mortality is a poor quality standard for musculoskeletal services. Specific outcome measures within the domains are not yet defined for the majority of musculoskeletal conditions. In practice, this means that the commissioning of musculoskeletal services will still be dependent on process measures as surrogates for outcomesa5 and benchmarking against national data setsa6–8 until validated outcome measures have been developed. The challenge will be to fund data collection for outcomes, from accredited sources, without detracting clinicians from patient care.a9

The domain most relevant to commissioning musculoskeletal conditions that do not require admission is: domain 2 ‘Enhancing quality of life for people with long-term conditions’. The relevant indicators chosen for domain 2 for 2011/12 are:

the proportion of people feeling supported to manage their condition

employment of people with long-term conditions.

Achieving these will require considerable cooperation between health, social and employment services. This will require new, less insular ways of working for GP consortia and providers. However, contrasting with chronic conditions, many acute and recurrent conditions will not be captured by these outcome measures.

For those patients admitted electively or as emergencies with musculoskeletal problems, the most relevant domain is: domain 3 ‘Helping people to recover from episodes of ill health or following injury’. The relevant indicators chosen for domain 3 for 2011/12 are:

emergency admissions for acute conditions that should not usually require hospital admission

emergency readmissions

patient reported outcomes measures

the proportion of fragility fracture patients recovering to their previous levels of mobility/walking ability.

In addition, there are patient experience, access and safety indicators in domains 4 and 5.

Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention

The Operating Framework for the NHS in England 2011/12 outlines how GP consortia will need to oversee management and implementation of Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention (QIPP) plans, to deliver change, and savings whilst maintaining quality and outcomes.a2 The QIPP agenda aims to maintain quality care in an era of financial constraint by increasing productivity and integrating services.a2,a4 The QIPP Long-Term Conditions workstream is the most closely allied to musculoskeletal service delivery, although it is less relevant for acute and recurrent presentations of musculoskeletal disorders. Although the focus is on preventing (costly) hospital admissions, the workstream promotes integrated care teams, which treat and supporting the person rather than a condition. Perhaps the strongest contribution to musculoskeletal services is the strand of the workstream that promotes patient self-care and management. This reflects current NICE advice about the management of osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and low back pain.a10–12 It has been difficult to secure funding for these low-level interventions from the health budget, because of the lack of pump priming funding, and because the musculoskeletal health–economic benefits from self-care, weight loss and cardiovascular exercise are modest and take a long time to realise.a10–12

The challenge for GP consortia will be to liaise with social care to ensure the availability of affordable leisure facilities and coaching as well as finding the pump priming funds for education programmes to continually encourage patients to persevere with weight loss and exercise.

ADDITIONAL REFERENCES

- a1.Department of Health Equity and excellence; liberating the NHS. London: Department of Health, 2010. www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/@ps/documents/digitalasset/dh_117794.pdf (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- a2.Department of Health The operating framework for the NHS in England 2011/12. London: Department of Health, 2010. www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/@ps/documents/digitalasset/dh_122736.pdf (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- a3.Department of Health The NHS outcomes framework 2011/12. London: Department of Health, 2010. www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/@ps/documents/digitalasset/dh_122956.pdf (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- a4.Department of Health The NHS quality, innovation, productivity and prevention challenge: an introduction for clinicians. London: Department of Health, 2010. www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/@ps/documents/digitalasset/dh_113807.pdf (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- a5.Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance Liberating the NHS: transparency in outcomes – a framework for the NHS. Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance consultation response. London: Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance, 2010. www.arma.uk.net/pdfs/Transparency%20in%20outcomes%20ARMA%20response%20FINAL%202.pdf (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- a6.Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance Joint working? An audit of the implementation of the Department of Health's musculoskeletal services framework. London: Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance, 2009. www.arma.uk.net/pdfs/MSF%20Review_FINAL1.pdf (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- a7.Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance The musculoskeletal map of England. Evidence of local variation in the quality of NHS musculoskeletal services. London: Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance, 2010. www.arma.uk.net/pdfs/Musculoskeletal%20map%20FINAL%202.pdf (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- a8.Bernstein I. Funding for community musculoskeletal services. London: NHS Ealing, 2010. www.ealingpct.nhs.uk/Library/Pec_papers/PECBoard2010/March2010/Funding%20for%20Community%20Musculoskeletal%20Services.pdf/ (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- a9.Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance Response of ARMA to ‘Equity and Excellence Liberating the NHS’. London: Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance, 2010. www.arma.uk.net/pdfs/ARMA%20White%20Paper%20Response%20FINAL.pdf (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- a10.National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions Osteoarthritis: national clinical guideline for care and management in adults. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2008. www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG059FullGuideline.pdf (accessed 26 December 2010). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a11.National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions Rheumatoid arthritis: national clinical guideline for care and management in adults. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2009. www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG79FullGuideline.pdf (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- a12.Savigny P, et al. Low back pain: early management of persistent non-specific low back pain. London: National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care and Royal College of General Practitioners, 2009. www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG88fullguideline.pdf (accessed 26 December 2010). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

REFERENCES

- 1.Bernstein I. Across the divide: joined-up working. The challenge of delivering musculoskeletal services under the UK's National Health Service reforms. Journal of Orthopaedic Medicine 2007;29(1):1–8 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clinical Standards Advisory Group for Back Pain Back pain report of a CSAG Committee on Back Pain. London: HMSO, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions Osteoarthritis: national clinical guideline for care and management in adults. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2008. www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG059FullGuideline.pdf (accessed 26 December 2010). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance Standards of care for people with inflammatory arthritis. London: Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance, 2004. www.arma.uk.net/pdfs/ia06.pdf (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke A, Symmons D. The burden of rheumatic disease. Medicine 2006;34(9):333–5 doi:10.1053/j.mpmed.2006.06.007 (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arthritis Research Campaign Arthritis: the big picture. Chesterfield: Arthritis Research Campaign, 2002. www.ipsosmori.com/Assets/Docs/Archive/Polls/arthritis.pdf (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance Joint working? An audit of the Department of Health's musculoskeletal services strategy. London: Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance, 2009. www.arma.uk.net/pdfs/MSF%20Review_FINAL1.pdf (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Bone and Joint Health Strategies Project European action towards better musculoskeletal health: a public health strategy to reduce the burden of musculoskeletal conditions. Lund, Sweden: The Bone and Joint Decade, 2004. http://www.boneandjointdecade.org/ViewDocument.aspx?ContId=534 (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K. Depression and pain comorbidity a literature review. Archives of Internal Medicine 2003;163(20):2433–45 http://archinte.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/163/20/2433 (accessed 26 December 2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnow BA, et al. Comorbid depression, chronic pain, and disability in primary care. Psychosomatic Medicine 2006;68:262–8 www.psychosomaticmedicine.org/cgi/content/full/68/2/262 (accessed 26 December 2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Health Estimated England level gross expenditure by programme budget. London: Department of Health, 2010. www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_general/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_118577.pdf (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Department of Health NHS business definitions: interface service. London: Department of Health, 2010. www.datadictionary.nhs.uk/data_dictionary/nhs_business_definitions/i/interface_service_de.asp?shownav=1 (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Department of Health The musculoskeletal services framework. London: Department of Health, 2006. www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4138412.pdf (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 14.NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement and Academy of Medical Royal Colleges Medical leadership competency framework, enhancing engagement in medical leadership, 3rd edition Coventry: NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, 2010. www.institute.nhs.uk/images/documents/Medical%20Leadership%20Competency%20Framework%203rd%20ed.pdf (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goh L, Samanta A, Cavendish S, Heney D. Rheumatology curriculum: passport to the future successful handling of the musculoskeletal burden? Rheumatology 2004;43(12):1468–72 http://rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org/content/43/12/1468.full.pdf+html (accessed 26 December 2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Department of Health Equity and excellence; liberating the NHS. London: Department of Health, 2010. www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/@ps/documents/digitalasset/dh_117794.pdf (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Department of Health The operating framework for the NHS in England 2011/12. London: Department of Health, 2010. www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/@ps/documents/digitalasset/dh_122736.pdf (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Department of Health The NHS outcomes framework 2011/12. London: Department of Health, 2010. www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/@ps/documents/digitalasset/dh_122956.pdf (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Department of Health The NHS quality, innovation, productivity and prevention challenge: an introduction for clinicians. London: Department of Health, 2010. www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/@ps/documents/digitalasset/dh_113807.pdf (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance Liberating the NHS: transparency in outcomes – a framework for the NHS. Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance consultation response. London: Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance, 2010. www.arma.uk.net/pdfs/Transparency%20in%20outcomes%20ARMA%20response%20FINAL%202.pdf (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernstein I. Ealing PCT Integrated musculoskeletal service. International Musculoskeletal Medicine 2009;31(2):87–88, 93 doi:10.1179/175361409X412638 (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernstein I, Griffiths S. Guidelines for GP referral for musculoskeletal conditions. London: NHS Ealing, 2009. www.ealingpct.nhs.uk/Library/Pec_papers/PECBoard2009/October%202009/Item%206%20WCC%20Guidelines%20for%20GP%20Referral%20for%20Musculoskeletal%20Conditions%20IAB%20SG%202009–09–26col.pdf (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 23.NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement Focus on: musculoskeletal interface services. Coventry: NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, 2009. www.institute.nhs.uk/msk (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernstein I. Musculoskeletal services: adding life to years. London: NHS Ealing, 2009. www.ealingpct.nhs.uk/Library/PDF/Publication_PDFs/Bernstein_2009_Musculoskeletal_Services-_Adding_Life_to_Years.pdf (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ealing Council and NHS Ealing Joint strategic needs assessment update 2009–10. London: Ealing PCT, 2010. www.ealingpct.nhs.uk/Library/JSNA/JSNA_2009–2010_Updates/JSNA_update_2009–2010_statement_Part%20Two_FINAL.doc (accessed 26 December 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernstein I. EPCT MRI Scanning from primary care for musculoskeletal conditions. London: NHS Ealing, 2010 [Google Scholar]

FUNDING

None.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Not required.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Ian Bernstein is a clinical advisor to Ealing PCT and the British Institute of Musculoskeletal Medicine. He is also a musculoskeletal physician with Ealing and Harrow Community (Provider) Services.