Key messages

The NHS faces significant challenges in managing demand for health services that will not be met using current models of care.

A paradigm shift in models of care is needed away from a curative, acute-centric approach to a preventative, primary-care-focused approach.

Sustainable development principles can support this transformational change and ensure a whole-systems approach is taken to delivering care.

GP commissioning consortia should build sustainability principles into their governance and contracting processes.

Why this matters to me

I feel the health system has not grasped the full implications of the demand challenges and external risks facing the system in this century and the fundamental shift in the model of care required. In healthcare we are extremely good at responding to immediate crises and emergencies, capable of banding together to do some remarkable things in the face of adversity. However, with longer term strategic issues and risks, issues like climate change that my boss David Pencheon would term ‘slow burn emergencies’, we often seem to lack the strategic will to take decisive action despite the strength of the evidence base that shows our approach is untenable in the longer term.

I recently got married (October 2010) and this coincided with my first anniversary of starting at the NHS Sustainable Development Unit. This coupled with the huge NHS change programme has led me to reflect a great deal about the future and in particular how we can ensure that the values of the health system continue to endure. Before starting at the NHS Sustainable Development Unit I thought that sustainability was about turning lights off, driving the car less and turning the heating down – and actually this is an important aspect of environmental sustainability at a micro-level. However, I have subsequently learnt that at a macro-level sustainability is a philosophy, or a way of doing things at a whole-systems level to drive efficiency, contain costs, continually improve and ensure system resilience through balancing competing demands of the ‘here and now’ and the future.

Keywords: carbon footprint, conservation of energy resources, greenhouse effect, general practice, holistic health

Abstract

There are many challenges facing the health system in the 21st century – the majority of which are related to managing demand for health services. To meet these challenges emerging GP commissioning consortia will need to take a new approach to commissioning health services – an approach that moves beyond the current acute-centred curative paradigm of care to a new sustainable paradigm of care that focuses on primary care, integrated services and upstream prevention to manage demand. A key part of this shift is the recognition that the health system does not operate in a vacuum and that strategic commissioning decisions must take account of wider determinants of health and well-being, and operate within the finite limits of the planet's natural resources. The sustainable development principle of balancing financial, social and environmental considerations is crucial in managing demand for health services and ensuring that the health system is resilient to risks of resource uncertainty and a changing climate. Building sustainability into the governance and contracting processes of GP commissioning consortia will help deliver efficiency savings, impact on system productivity, manage system risk and help manage demand through the health co-benefits of taking a whole systems approach to commissioning decisions. Commissioning services from providers committed to corporate social responsibility and sustainable business practices allows us to move beyond a health system that cures people reactively to one in which the health of individuals and populations is managed proactively through prevention and education. The opportunity to build sustainability principles into the culture of GP commissioning consortia upfront should be seized now to ensure the new model of commissioning endures and is fit for the future.

Introduction

There is a problem at the heart of the acute-centric curative paradigm of care that has prevailed since the inception of the NHS in 1948. The tension between infinite need and finite resources is constant and the current treatment-focused approach seems unable to stem demand for health services and manage this tension. Undoubtedly, the innovation and ingenuity in the health system means the NHS has been very successful in curing people, in fact it has been too successful as demand continues to grow along with expectations around clinical outcomes and the experience of using the service. The problems facing new GP commissioning consortia can be summarised as:

a perpetually increasing demand on health services fuelled by a growing, less healthy, aging population with numerous co-morbidities

increasing expectations around quality of clinical outcomes and experience of using the service

global and national economic challenges

uncertainty due to diminishing global resources coupled with increasing demand from the developing world.

It is conceivable that the NHS could meet these challenges within the constraints of the current paradigm of delivering care and commissioning practices. However, when we add a changing climate and the well-documented associated risks to health1–3 the balance is tipped. The Lancet states that ‘climate change is the biggest global health threat of the 21st century’2 and based on UK climate projections to 2050 heat-related deaths are likely to increase, by about 2000 cases per annum (pa), cases of food poisoning are likely to increase significantly by perhaps 10000 cases pa, the risk of major disasters caused by severe winter gales and coastal flooding is likely to increase significantly, cases of skin cancer are likely to increase by perhaps 5000 cases pa and cataracts by 2000 cases pa.3 Globally, the indirect risks to health and health systems through a changing climate are likely to be far more catastrophic. Famine, drought, wars over increasingly scarce resources, civil unrest and mass migration have the potential to kill millions and the globalised nature of modern society means the UK will undoubtedly be affected.4

Einstein5 allegedly said ‘the significant problems we face cannot be solved at the same level of thinking we were at when we created them’ and this captures the very essence of what the current changes should be about – breaking free from the old acute-centred model of care delivery to a new transformational model of care delivery. To manage the many and varied challenges of the 21st century will require a new approach to commissioning. An approach that encourages the seamless integration of services, that manages demand, that aims to prevent ill health rather than incentivising secondary care activity, that uses evidence to make informed decisions and balances the operational needs of the short-term with the strategic needs of the longer term. In other words, the approach should be sustainable. The principles of sustainable development will help commissioners achieve integrated care and, if they are embedded into the governance, service redesign and contracting processes of GP commissioning consortia, will help catalyse the transformational shift to a primary care centred, preventative paradigm of care delivery.

What is sustainable development?

A commonly used definition is:

development that meets the needs of the present … without compromising the ability of others, in future or elsewhere now, to meet their own needs. (adapted from the World Commission on Environment and Development)6

Importantly, the quote talks about ‘needs’. It does not talk about ‘the environment’, ‘being green’ or ‘saving the planet’. Sustainability is not about being idealistic – it is about using resources sensibly so there are enough left for others in the world today and the next generation tomorrow.

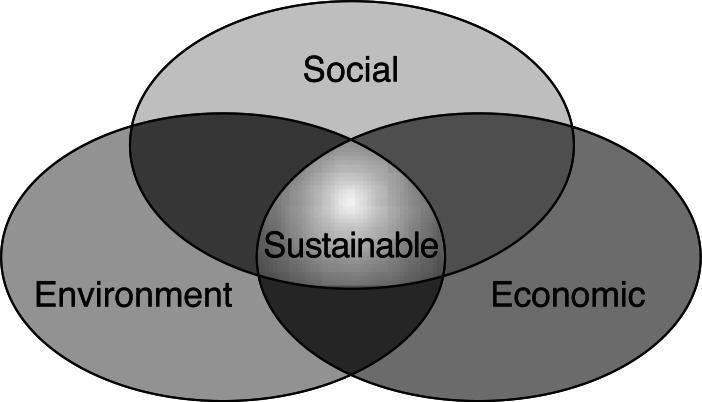

Sustainability is how we strike the right balance between three key areas: ‘economic sustainability’, ‘social sustainability’ and ‘environmental sustainability’. This is illustrated by the ‘sweet spot’ in Figure 1.7 Sustainability in health is simply the recognition that the health of the individual is inextricably linked to their physical and social environment – the consequence being that an acute-centred, purely curative model of healthcare will help stem demand but never manage it. Sustainability emerges when you look at the bigger picture and consider how different factors interact. Primary care clinicians intuitively see the whole picture as they are used to working with people, rather than parts of people.

Figure 1.

Why is sustainability a commissioning issue?

There are three main reasons: managing system risk, managing demand and contractual levers.

Managing system risk

Sustainability is essentially about excellence in business management. Commissioning organisations are able to, and must, take a whole-systems approach to both delivery (ensuring integration of provider services) and managing future risks (for example, resource uncertainty, a changing climate).

Fortunately, some of the risk of a changing climate can be mitigated through the NHS reducing the amount of greenhouse gases it produces. The current carbon footprint of the NHS is 21 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (a quarter of public sector emissions) and makes the NHS the largest emitter of greenhouse gases in Europe. The NHS Carbon Reduction Strategy8 published in 2009 sets out how organisations can reduce their carbon footprint by 10% by 2015 (against a 2007 baseline). As well as mitigating external risk, efforts to reduce carbon dioxide emissions and eliminate waste (in terms of resources and time) across the health system will drive the adoption of more efficient processes. This will allow organisations to deliver on the ‘triple bottom line’ – i.e. simultaneous financial, social and environmental return on investment (e.g. saving money, health improvement and mitigating climate change). A 2010 study9 by the NHS Sustainable Development Unit identified £180 million of direct savings across the NHS in England through initiatives aimed at reducing carbon. Perhaps more importantly though, in terms of whole-systems thinking, ‘measures taken to reduce the rate of climate change by reducing greenhouse gas emissions could produce secondary beneficial effects on health’.3

Carbon-intensive activities are often unhealthy activities and therefore reducing carbon will often impact both directly and indirectly on individual and population health.10 For example, more walking and cycling, and driving your car less, is good for health (all the health benefits of physical activity; less road trauma) and good for the environment (fewer carbon emissions, less air and noise pollution). In another example, eating more fruit and vegetables, and less red meat and processed foods, and eating locally produced foods, are good for both health and the environment.

Managing demand

Activity-based commissioning will not incentivise managing demand for health services. We need to start thinking about incentivising and enabling a ‘health and well-being service’ focused on an upstream preventative approach as opposed to an ‘ill health service’ based on activity

The current system of activity-based commissioning places undue weight on the operational needs of the short-term, often at the expense of the strategic needs of the longer term. Healthcare, by its nature, is often a very immediate activity. However, when taking commissioning decisions, the system would do well to remember that the strategic long-term of today is the operational reality of our children's tomorrow. Realistically, the next iteration of commissioning must demonstrate a greater degree of maturity, perspective and sophistication in how it balances and assesses investment in treatment services and investment in prevention services if demand is to be successfully managed.

Contractual levers

Commissioners are responsible for allocating money and therefore have the power to ensure providers adopt sustainable business practices – this is especially true with the shift to an ‘any willing provider’ model. All contracts and tenders need to include statements on demonstrating real action on sustainable business practices and reducing carbon emissions.

Buying services from a provider that damages public health through its environmental practices, or promotes social inequality through its employment practices is at best short-sighted and at worst a breach of duty of care. Equally, the health co-benefits of buying services from providers that take sustainability, staff health and well-being, environmental impact, etc. seriously will deliver savings and improve health outcomes through linked environmental, social and financial considerations.

Through using NHS organisations' corporate powers and resources in ways that benefit rather than damage the social, economic and physical environment the NHS can make a big difference to people's health and to the well-being of society, the economy and the environment.

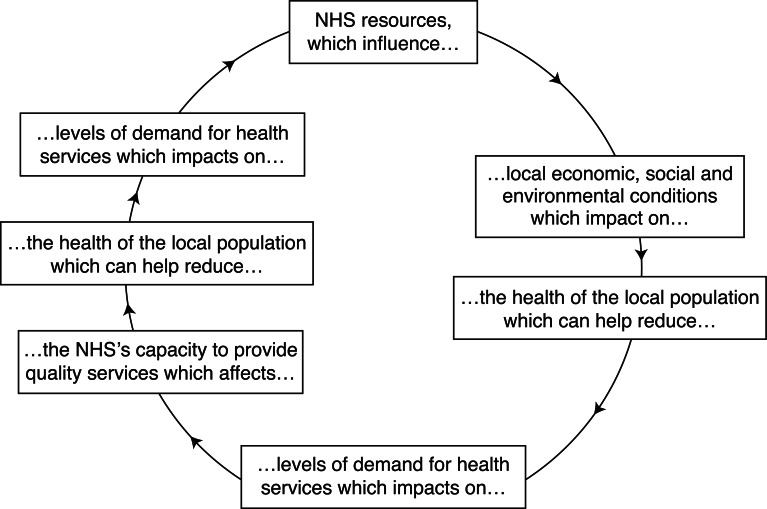

The business case for public sector organisations to adopt a corporate social responsibility (CSR) approach is far clearer in many instances than the business case for private sector firms (see Figure 2). This is because health and well-being are the business of the NHS, and CSR could play a key role in managing demand for NHS services through improved prevention. Also, as the largest employer in Europe, any benefits to the physical and mental well-being of the population could potentially improve productivity through decreased staff absence and a healthier, happier work-force. Therefore, unlike for many private firms, taking sustainability seriously has many direct implications for the health system.

Figure 2.

Virtuous circle for NHS corporate social responsibility.8 What now?

What now?

To break the cycle of costly structural changes in the health system any new commissioning approach must be sustainable. As the structures, governance and culture of the GP commissioning consortia continue to take shape it is an ideal opportunity to consider how the principles of sustainability can be embedded up front to ensure the longevity and resilience of the health system in an uncertain future. Systemic quality, must at least partially, be judged on how well it endures and the strategist who is unconcerned by sustainability is akin to the architect who cares not whether their building stands or falls. In recognition of this the Royal College of General Practitioners Centre for Commissioning have identified sustainability as one of five foundations of effective commissioning.11

Regardless of personal views about the health reforms, the choice to do things differently is firmly in the hands of GPs. In these turbulent times of transition and change, one thing is certain – the demand challenges of the 21st century will need to be addressed at some point; if not now, then when?

REFERENCES

- 1.McMichael A, Woodruf R, Hales S. Climate change and human health: present and future risks. Lancet 2006;367:859–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costello A, Abbas M, Allen A, et al. Managing the health effects of climate change. Lancet 2009;373:1693–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health Health Effects of Climate Change in the UK. www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4068835.pdf (accessed 14 January 2011).

- 4.Pencheon D. Can Primary Care Lead the Way for a Sustainable Health Service? Presented at Royal College of General Practitioner's Annual Conference Harrogate, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wikipedia Albert Einstein. http://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Albert_Einstein (accessed 14 January 2011).

- 6.United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development Our Common Future: report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. www.un-documents.net/ocf-02.htm (accessed 14 January 2011).

- 7.Barbier E. The concept of sustainable economic development. Environmental Conservation 1987;14(2):101–10 [Google Scholar]

- 8.NHS Sustainable Development Unit Saving Carbon Improving Health; NHS carbon reduction strategy for England. www.sdu.nhs.uk/publications-resources/3/NHS-Carbon-Reduction-Strategy (accessed 14 January 2011).

- 9.NHS Sustainable Development Unit Saving carbon improving health; update – NHS carbon reduction strategy. www.sdu.nhs.uk/publications-resources/42/NHS-Carbon-Reduction-Strategy-Update (accessed 14 January 2011).

- 10.Haines A, Smith KR, Anderson D, et al. Policies for accelerating access to clean energy, improving health, advancing development, and mitigating climate change. Lancet 2007;370:66–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Royal College of General Practitioners Centre for Commissioning Foundations for Effective Commissioning. www.rcgp.org.uk/centre_for_commissioning/effective_commissioning.aspx (accessed 14 January 2011). [Google Scholar]

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Not needed because the article does not involve human participants, either directly (e.g. through use of interviews, questionnaires) or indirectly (e.g. through provision of, or access to, a person's data). The article only uses publicly available anonymous data, such as census, population or other official statistical data.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

James Mackenzie is the Organisational and Workforce Development Advisor for the NHS Sustainable Development Unit.