Key messages

Communication for the care of patients with complex needs can usefully be improved when general practitioners post Special Patient Notes on the out-of-hours database, when information of out-of-hours consultations are cascaded to community matrons as well as to general practices, and when regular educational meetings between community matrons and general practitioners are held.

A collaborative inquiry with people from all parts of a system of care, coupled with a systems diagram, helps practitioners and managers to agree a shared approach to communication problems.

Why this matters to me

We are all frustrated by poor communication within extended primary care teams that wastes our time and results in poor patient care. We recognise that good communication is diffcult to achieve because of the overwhelming amount of work to be done. We seek a simple formula that all could follow, to help the timely transfer of relevant information, and also to facilitate creative interaction between the disciplines.

Keywords: case management, communication, community matrons, out-of-hours, primary care team, vulnerable patients

Abstract

Background Poor communication between community matrons (CMs), in-hours and out-of-hours (OoH) general practitioners (GPs) causes uncertainty and inefficiencies.

Setting A practice-based commissioning group in West London and the associated CMs who case manage high users of hospital services.

Question What helps good communication between CMs, GPs and OoH services to ensure that the right patients are case managed and hospital admissions are avoided?

Methods Whole system participatory action research, with four stages: 1) identify communication problems as perceived by a wide range of stakeholders; 2) draw a diagram of the existing communication system, and with stakeholders redraw this to overcome its weaknesses; 3) pilot the changes proposed; 4) gain consensus among stakeholders about policy.

Results Stakeholders agreed that standards should be adopted to improve communication for the care of patients who are case managed by CMs. Routine passage of information between GP, CMs and the OoH services would achieve this, and is feasible. Specifically:

routine information (termed Special Patient Notes) should be sent to the OoH service about vulnerable patients, including those who are case managed by CMs

clear information about CM attachment to general practices and how to refer to them should be easily accessible

GPs and CMs should meet quarterly for mutual learning and to discuss patients

the OoH service electronically should cascade information to GPs, CMs and others named in the Special Patient Notes

commissioners should routinely gather data to compare clusters of general practices for i) referrals to CMs, ii) posting Special Patient Notes, iii) unscheduled consultations and hospital admissions of all patients including those being case managed.

Discussion This project revealed system-wide communication problems for the care of patients being case managed by CMs, and ways to overcome these. Commissioners could insist that these are adopted locally, and gather data to prompt compliance and evaluate the consequential cost savings.

Background

In Ealing, 194 GPs in 83 general practices serve a population of over 300 000. In 2007, 12 community matrons (CMs) were attached to these practices to case manage very high users of hospital services, aiming to reduce hospital admissions. Case management is a way of bringing focused and continued attention to the breadth of problems experienced by a patient/client that, for one reason or another, are difficult to manage in a more ad hoc way.1 Under the broad term ‘chronic care model’, nurses have successfully used case management to reduce glycosylated haemoglobin, mortality and complications in diabetics and improve healthy behaviours.2

In 2008, members of a practice-based commissioning group became suspicious that poor communication between CMs, in-hours and out-of-hours (OoH) GPs was causing inefficiencies, resulting in unnecessary admissions to hospital. In 2009 a grant from West London CLAHRC allowed them to explore this concern.

Methods

We used whole system participatory action research (PAR)3 because it has the ability to improve whole systems of care. It can deal with three well-known obstacles to success in complex situations:

primary care is not one organisation, but a network of organisations that employ different practitioners with different roles – changing the way they communicate requires a consensus that the proposed changes are useful and feasible

communication systems are used for many purposes – changing one aspect often destabilises others unless they also change at the same time

doing more of one thing means doing less of something else – the change process must reveal that proposed changes are time-efficient and cost-efficient.

Whole system PAR gains consensus, facilitates mutual adaptations and evaluates efficiencies through cycles of collective reflection and action. A range of practitioners and managers appropriate for the system under study reflect on their own experiences and agree what is wrong with the present situation. They model a new way of doing things and pilot synchronous changes. Finally they agree a set of policies to create and maintain the new system. They commission training and ongoing data-gathering for long-term sustainability.

Five stages were punctuated by four multidisciplinary stakeholder workshops. Stakeholder workshops included practitioners and managers who needed to communicate for the care of patients being case managed by CMs. Small-group–large-group iterations, brainstorming and role play were used at the workshops to reveal the deeper issues, critique progress and agree next steps. A report of each workshop records the ideas of participants as well as agreements about action.

An ‘Oversight Team’ of 19 co-inquirers was created, including practitioners and managers from various parts of the system. Oversight Team members critiqued the work of the project team at each stage, sense-checked conclusions, and facilitated dissemination of findings. Fourteen members of the Oversight Team attended at least one workshop (all received workshop reports). Total participants at the workshops ranged from 19 to 31.

Five stages

Clarifying the problems. Stage one: 2008– April 2009

A series of workshops, interviews, observations and role play produced a range of insights that were discussed at a stakeholder workshop on 30 April 2009. At the workshop, GPs, CMs, practice managers, practice nurses, and OoH managers agreed that many aspects of communication were poor. Many GPs did not even know that CMs were attached to their practice. Other GPs had lost touch with the patients, becoming less able to fulfil their role when needed. Too few patients were known to the OoH services, inhibiting good decisions by OoH GPs.4 OoH services send information to GPs and not to CMs, delaying recognition that their client was deteriorating. The project team was charged with finding more information, prior to agreement about pilot changes.

Rapid appraisal. Stage two: April–July 2009

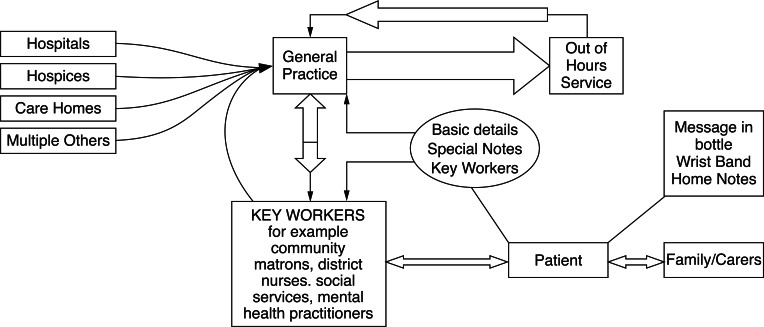

Rapid appraisal is a technique that quickly reveals a ‘big picture’ of a complex issue in a way that helps a community to lead action for change.5 It combines observations, interviews and literature. To complement the insights from Stage One, the project team undertook a literature review, analysed hospital attendances, and worked with stakeholders to draw a diagram of the present communication system (Figure 1) and a proposed improved system (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Present communication system

Figure 2.

Improved communication system

Figure 1 shows disconnects in the system that prevent adequate information passing between GPs, OoH services and CMs, and poor engagement of patients in the process. The diagram reminds us that most practitioners in primary and secondary care send information to GPs, but the enormous volume of information prevents GPs from cascading relevant bits to other practitioners, including CMs. Mostly this does not matter because CMs already have up-to-date information, or there is no urgency. Sometimes it does matter, for example, when a patient is seen by an OoH practitioner for a crisis.

The OoH practitioner is helped to make the best decision about a patient in crisis (e.g. if s/he collapses) when they have brief but insightful information about patient wishes and needs (e.g. if they do not want to be resuscitated). The system to alert the OoH practitioners is called the ‘Special Patient Notes’ system – a web-based database. Presently it is mainly GPs who post notes and receive information about OoH consultations. The Special Patient Notes system is under-used, probably causing unnecessary admissions to hospital.

Patients have no input into the special notes system. Some have other mechanisms to alert OoH practitioners to special needs, e.g. home notes, with brief summary in a bottle in the fridge. Participants in this study thought that patient input would be valuable.

Figure 2 shows a proposed communication system devised by participants to solve these problems. It involves: a) regular posting of ‘Special Patient Notes’ and electronic communication from OoH practitioners to both GPs and CMs; b) regular communication between GPs and CMs; c) patient input into the notes.

Pilot changes. Stage three: July–November 2009

At the second stakeholder workshop on 15 July 2009, participants reviewed the diagrams. Carers of a patient of a CM who had died the previous week gave a rich account of the consequences of poor communication. Participants reached consensus that they had to improve communication, proposing the following plan:

Six general practices would pilot ways to overcome the weak links in the diagram, including: a) referral to CMs; b) posting Special Patient Notes for the OoH services; c) improved communication between GPs, OoH and CMs.

Two CMs would pilot a way for patients to draw a diagram of how they experience communication problems within the system of care.

Results. Stage four: November 2009–July 2010

Participants reviewed data and the ongoing experience of the practices at the stakeholder workshop on 19 November 2009 (to agree interim conclusions) and on 24 June 2010 (to finalise these). They agreed that posting Special Patient Notes and better communication between CMs and GPs was desirable and feasible. Cascade of information to CMs was not easy from general practice, but it might be possible to develop this function from the OoH service. Patient involvement, though valuable, was too time-consuming. A training pack to improve communication was developed and used with practices (March 2010).

Stakeholders agreed that the following standards should be adopted to improve communication for the care of patients who are case managed by CMs:

Routine information (Special Patient Notes) should be sent to the OoH service about vulnerable patients, including those who are case managed by CMs.

Clear information about CM attachment to general practices and how to refer to them should be easily accessible.

GPs and CMs should meet quarterly for mutual learning and to discuss patients.

The OoH service electronically should cascade information to GPs, CMs and others named in the Special Patient Notes.

Commissioners should routinely gather data to compare clusters of general practices for: i) referrals to CMs; ii) posting Special Patient Notes; iii) un-scheduled consultations and hospital admissions of all patients including those being case managed by CMs.

Figure 3 shows the number of Special Patient Notes posted per 1000 patients by practices in Ealing. The six pilot practices considered it necessary to post almost twice the average of other practices in their own commissioning group (Group One), and more than the all the other groups. If their experience is translatable to other practices, it suggests that every practice should expect to have at least two notes per 1000 patients posted at any time.

Figure 3.

Number of special patient notes posted with the OoH service between October 2009 and June 2010

Figure 4 shows that referrals to CMs in the first year (2008–2009) were much higher and irregular than in the second year. Between two and 25 patients each month were referred from practices of the involved commissioning group. A similar trend happened throughout Ealing. CMs explained that this was a backlog of complex fragile patients being cleared. The levelling off at 20 new referrals per month seen in year two might reflect future demand.

Figure 4.

Patients referred to CMs

Embedding within policy. Stage five. July 2010+

To implement these findings Ealing commissioners are now:

inviting all GP commissioning groups to debate these findings, adopt the standards, and sign up for electronic links to post Special Patient Notes and receive communication from the OoH service electronically

asking the OoH service to give information to all practices about how to set up web-posting and electronic links and ensure that their Special Patient Notes form includes contact details of practitioners other than GPs (including CMs)

working with the OoH provider and the Adastra software company to develop the software to cascade information to key practitioners other than GPs (including CMs)

inviting practice managers to debate these findings, to recognise the importance of posting notes, and set up electronic links

inviting managers of community nurses and applied health professionals to support CMs to lead next steps in embedding the new communication system, including the regular educational meetings with practices

asking the NHS Ealing Information Management team to send GP commissioning groups data of referrals to community matrons, posting Special Patient Notes and unscheduled admissions of patients

inviting other members of the extended primary care team to consider ways in which the communication system could be useful to them.

Discussion

This study complements our previous study on communication for end-of-life care.4 Together they reveal a way to stimulate team-working for the care of vulnerable patients, and measure the effect on costly hospital admissions. Both can be ensured through commissioning.

The most important thing this project did was help practitioners and managers from different parts of the system to pool their insights and from these to form a shared vision about something that was too complex for any of them to see on their own. As with the previous study, when participants from different parts of the system were able to stand back and examine the system as a whole, they quickly recognised important disconnects within it and came to consensus about what to do about them. This was greatly helped by a systems diagram that helped participants to see the whole system.

Whole system participatory action research is one of several methodologies and methods that help practitioners and managers to see a bigger picture, learn from and with each other about how to improve it, and then collaborate to make synchronous changes. Others include action learning,6 organisational learning,7 learning communities8 and Plan Do Study Act (PDSA) cycles. If commissioning is to meaningfully examine whole system of care it needs to use approaches like these.

One question that greatly interests us is whether the stages described in this project could be embedded within GP commissioning. This would make the commissioning cycle a learning cycle, and allow timely input of large numbers of people from a broader ‘local health community’. This could integrate different efforts for health in horizontal as well as vertical directions.9 We are very encouraged that our timeline happened almost exactly as planned, suggesting that it could be embedded in this way.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Our thanks to Ealing Acton Commissioning Group and the six general practices that piloted this work. Thanks to leaders of a related project in NHS Brent that piloted the use of case management by primary care practitioners. Thanks also to Karen Phekoo from CLAHRC.

Contributor Information

Paul Thomas, Clinical Director, NHS Ealing Primary Care Trust, Southall, UK.

Gilly Stoddart, NHS Ealing Applied Research Unit Facilitator.

Johnny Nota, Ealing & Harrow Community Services.

Ling Teh, Community Matron.

Victoria Wells, Practice Manager, Hillcrest Surgery.

Gouri Dhillon, General Practitioner, Argyle Surgery.

Yvonne Leese, Associate Director of Operational Services, Ealing & Harrow Community Services.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lewis S. Case management. In: Neno R, Price D. (eds) The Handbook for Advanced Primary Care Nurses. Maidenhead: Open University Press, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodenheimer T, MacGregor K. Nurses as leaders in chronic care. BMJ 2010; 330(7492):612–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas P, McDonnell J, McCulloch J, While A, Bosanquet N, Ferlie E. Increasing capacity for innovation in large bureaucratic primary care organizations – a whole system participatory action research project. Annals of Family Medicine 2005;3:312–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas P. Inter-organisation communication for end of life care. London Journal of Primary Care 2010; 2(2):118–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armson R, Ison RL, Short L, Ramage M, Reynolds M. Rapid Institutional Appraisal. 2005, personal communication

- 6.Revans R. ABC of Action Learning. London: Lemos and Crane, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Argyris C, Schon DA. Organizational Learning 2 – Theory, method and practice. USA: Addison Wesley, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wenger E. Communities of practice and social learning systems. Organization 2000; 7(2):225–46 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas P, Meads G, Moustafa A, Nazareth I, Stange K. Combining horizontal and vertical integration of care: a goal of practice based commissioning. Quality in Primary Care 2008; 16(6):425–32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

ETHICAL APPROVAL

This was a service improvement project so did not need research ethical committee approval. Instead NHS Ealing Clinical Governance Group approved and monitored the project.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None.