Abstract

In the present study we examined whether LPA can be synthesized and act during in vitro maturation of bovine cumulus oocyte complexes (COCs). We found transcription of genes coding for enzymes of LPA synthesis pathway (ATX and PLA2) and of LPA receptors (LPAR 1–4) in bovine oocytes and cumulus cells, following in vitro maturation. COCs were matured in vitro in presence or absence of LPA (10−5 M) for 24 h. Supplementation of maturation medium with LPA increased mRNA abundance of FST and GDF9 in oocytes and decreased mRNA abundance of CTSs in cumulus cells. Additionally, oocytes stimulated with LPA had higher transcription levels of BCL2 and lower transcription levels of BAX resulting in the significantly lower BAX/BCL2 ratio. Blastocyst rates on day 7 were similar in the control and the LPA-stimulated COCs. Our study demonstrates for the first time that bovine COCs are a potential source and target of LPA action. We postulate that LPA exerts an autocrine and/or paracrine signaling, through several LPARs, between the oocyte and cumulus cells. LPA supplementation of maturation medium improves COC quality, and although this was not translated into an enhanced in vitro development until the blastocyst stage, improved oocyte competence may be relevant for subsequent in vivo survival.

1. Introduction

During the last decade, the functional role of lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) in the female reproduction has been the object of an increasing number of reports [1]. LPA, the simplest and at the same time one of the most potent phospholipids, has been regarded as an important signaling molecule participating in various biological processes, such as cell proliferation [2], differentiation [3], survival [4, 5], morphogenesis [6], and cytokine secretion [7]. This molecule is produced from membrane phospholipids by two main pathways/enzymes: autotaxin (ATX) and phospholipase A2 (PLA2) [8, 9]. In mammals, LPA exerts its action via at least six high affinity, transmembrane G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) types: LPAR1–LPAR6 and possibly through a nuclear receptor PPARγ [10–14]. Expression of LPARs is tissue and cell specific [15]. An association of LPA signaling with regulation of reproductive function first was described in women [16] and then in farm animals including ruminants [17, 18]. Our previous studies showed that LPA is locally produced and acts in the bovine uterus [18, 19] and ovary [20, 21]. We documented that the intravaginal administration of LPARs antagonist decreases pregnancy rate and that infusion of LPA prevents spontaneous luteolysis, prolongs the functional lifespan of the corpus luteum (CL), and also stimulates luteotropic prostaglandin (PG)E2 synthesis in heifers [18, 22]. Additionally, in in vitro studies, we found a stimulatory effect of LPA on progesterone (P4) synthesis and interferon (IFN)τ action in the steroidogenic cells of the bovine CL [20] and on luteotropic PGE2 synthesis in bovine endometrial cells [22]. Our recently published data demonstrates that bovine granulosa cells of the follicle are also the site of LPA synthesis and the target for LPA action [21]. In the above mentioned study [21], LPA exerted an autocrine and paracrine action in granulosa cells through several LPARs and stimulated estradiol (E2) synthesis via increased FSH receptor (FSHR) and 17β -hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (17β-HSD) expression. These results led us to hypothesize that cumulus oocyte complexes (COCs) may be the source and the target of LPA action during oocyte maturation. Oocyte maturation involves changes in the nucleus [23–25] and cytoplasm [26–29], and granulosa cells modulate chromatin configuration [30, 31], transcriptional activity [31], and cytoplasmic maturation [30, 32]. This bidirectional communication between the oocyte and surrounding cumulus cells is essential for proper oocyte maturation and determinates subsequent oocyte competence.

There are two major premises that initiated our studies on the effect of LPA supplementation of maturation medium on the communication between the oocyte and surrounding cumulus cells defined as embryonic development and the expression of genes involved in apoptosis and oocyte competence in oocytes and cumulus cells. The first premise documented by Boruszewska et al. [21] is concerned about an autocrine and paracrine action of LPA in the granulosa cells of the bovine ovarian follicle. The second premise regards the continuous, unrestrained development of the methods of in vitro culture of bovine embryos using variously supplemented media.

In the present study we examined whether LPA can be synthesized and act during in vitro maturation of bovine COCs. We also determined the effect of LPA supplementation of maturation medium on mRNA abundance of oocyte quality markers (follistatin-FST, growth and differentiation factor 9-GDF9, bone morphogenetic protein 15-BMP15, cysteine proteinases-cathepsins: CTSB, CTSK, CTSS, and CTSZ) and genes involved in apoptosis (BCL2 and BAX, as well as BAX/BCL2 ratio) in oocytes and cumulus cells. Finally, we evaluated the effect of LPA supplementation of maturation medium on cleavage and blastocyst rates on day 2 and day 7 of in vitro culture of bovine embryos, respectively.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Suppliers

All chemicals and reagents for in vitro culture were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Germany) unless otherwise stated. Plastic dishes, four-well plates, and tubes were obtained from Nunc (Thermo Scientific, Denmark). All chemicals for reverse transcription were acquired from Invitrogen (Life Technologies, USA).

2.2. Oocyte and Cumulus Cell Collection

All experimental procedures were approved by the Local Animal Care and Use Committee in Olsztyn, Poland (Agreement number 34/2012/N). Ovaries were collected from slaughtered cows and transported to the laboratory in sterile PBS at 37°C. COCs were obtained by aspiration from subordinate ovarian follicles, less than 5 mm in diameter. Only COCs consisting of oocytes with homogeneous ooplasm without dark spots and surrounded by at least three layers of compact cumulus cells were selected for the study. COCs were chosen under a stereomicroscope and washed two times in wash medium (TCM-199; #M2154) supplemented with 25 μg/mL amphotericin b (#A2942), 5 USP/mL heparin (#H3393), 25 mM HEPES (#H3784), 5 mM sodium bicarbonate (#S4019), 0.2 mM sodium pyruvate (#P3662), and 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS; #12106C) and subsequently washed in maturation medium.

2.3. Oocyte Maturation

26 groups of 25 immature COCs were cultured in four-well plates (#144444) containing 400 μL of maturation medium (TCM-199 supplemented with 0.4 mM L-glutamine (#G5763), 0.05 mg/mL gentamicin (#G1272), 1 μL/mL insulin-transferrin-sodium selenite, (ITS, #I3146), 10 UI/mL pregnant mare's serum gonadotropin (PMSG), and 5 UI/mL chorionic gonadotropin human (hCG; PG600, Intervet International, Boxmeer, The Netherlands) and 15% v/v FBS) under 400 μL of mineral oil (#M5310), as recently described by Torres et al. [33]. Two experimental groups were randomly generated for analyses from COCs: exposed to LPA agonist (LPA; 1-oleoyl-sn-glycerol 3-phosphate sodium salt; 10−5 M; #L7260) or PBS (control group) during in vitro maturation. The dose of LPA was taken from earlier reports on humans and rodents [34–36]. Subsequently COCs were matured in vitro for 24 h at 39°C under 5% CO2 in humidified air. After in vitro maturation, COCs were processed for total RNA extraction (for mRNA expression analysis) or in vitro fertilized and cultured (for cleavage and blastocyst rates analysis).

2.4. Sample Collection for RNA Isolation and Reverse Transcription

After 24 h of in vitro maturation, for total RNA extraction (for mRNA expression analysis), the oocytes from 5 pools of each experimental group (control or LPA treated) were separated from cumulus cells by vortexing. Each pool consisted of 25 denuded oocytes and all cumulus cells separated from the respective oocytes. The oocytes and cumulus cells were suspended in the Extraction Buffer and processed for RNA isolation according to manufacturer's instructions (#KIT0204, Arcturus PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit, Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies, USA). DNase treatment was performed for the removal of genomic DNA contamination using RNase-free DNase Set (#79254, Qiagen, Germany). Samples were stored at −80°C until reverse transcription. The reverse transcription (RT) was performed using oligo (dT)12–18 primers (#18418-012) by Super Script III reverse transcriptase (#18080-044) in a total volume of 20 μL to prime the RT reaction and produce cDNA. The RT reaction was carried out at 65°C for 5 min and 42°C for 60 min followed by a denaturation step at 70°C for 15 min. RNase H (#18021-071) was used to degrade the RNA strand of an RNA-DNA hybrid (37°C for 20 min). RT products were diluted four times and were stored at −20°C until real-time PCR amplification.

2.5. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

The quantification of mRNA for the examined genes was conducted by real-time PCR using specific primers for LPAR1, LPAR2, LPAR3, LPAR4, ATX, PLA2, FST, GDF9, BMP15, CTSB, CTSK, CTSS, CTSZ, BCL2, and BAX. The results of mRNA expression were normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, an internal control) mRNA expression and were expressed as arbitrary units. The primers were designed using an online software package (http://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3/). Primer sequences and the sizes of the amplified fragments of all transcripts are shown in Table 1. Real-time PCR was performed with an ABI Prism 7900 (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies, USA) sequence detection system using Maxima SYBR Green/ROX qPCR Master Mix (#K0222, Fermentas, Thermo Scientific, USA). The PCR reactions were performed in 96-well plates. Each PCR reaction well (20 μL) contained 2 μL of RT product, 5 pmol/μL forward and reverse primers each, and 10 μL SYBR Green PCR master mix. In each reaction we used a quantity of cDNA equivalent to 0.25 oocyte or cumulus cells. Real-time PCR was performed under the following conditions: 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 60 sec. Subsequently in each PCR reaction melting curves were obtained to ensure single product amplification. In order to exclude the possibility of genomic DNA contamination in the RNA samples, the reactions were also performed either with blank-only buffer samples or in absence of the reverse transcriptase enzyme. The specificity of the PCR products for all examined genes was confirmed by gel electrophoresis and by sequencing. The efficiency range for the target and the internal control amplifications balance was between 95 and 100%. For the relative quantification of the mRNA expression levels real-time PCR Miner algorithm was used (http://www.miner.ewindup.info/version2).

Table 1.

Primers used for real-time PCR.

| Gene | Primer sequence (5′-3′) | Fragment size, bp | GenBank accession number |

|---|---|---|---|

| LPAR1 | ACGGAATCGGGATACCATGA | 86 | NM_174047.2 |

| CCAGTCCAGGAGTCCAGCAG | |||

|

| |||

| LPAR2 | TTCTATGTGAGGCGGCGAGT | 161 | NM_001192235.1 |

| AGACCATCCAGGAGCAGCAC | |||

|

| |||

| LPAR3 | TCCAACCTCATGGCCTTCTT | 101 | NM_001192741.2 |

| GACCCACTCGTATGCGGAGA | |||

|

| |||

| LPAR4 | CCACAGTACCTCCAGAAAGTTCA | 192 | NM_001098105.1 |

| TTGGAATTGGAAGTCAATGAATC | |||

|

| |||

| ATX | ACCCCCTGATTGTCGATGTG | 120 | NM_001080293.1 |

| TCTCCGCATCTGTCCTTGGT | |||

|

| |||

| PLA2 | CTGCGTGCCACAAAAGTGAC | 92 | NM_001075864.1 |

| TCGGGGGTTGAAGAGATGAA | |||

|

| |||

| FST | GCAGCTCTACATGCGTGGTG | 133 | NM_175801.2 |

| TGACAGGCACTGGGGTAGGT | |||

|

| |||

| GDF9 | TCGGACATCGGTATGGCTCT | 86 | NM_174681.2 |

| GGATGGTCTTGGCACTGAGG | |||

|

| |||

| BMP15 | GCAGAGGAAGCCTCGGATCT | 104 | NM_001031752.1 |

| CAATGGTGCGGTTTTCCCTA | |||

|

| |||

| CTSB | GGCTCACCCTCTCCAGTCCT | 136 | NM_174031.2 |

| TCACAACCGCCTTGTCTGAA | |||

|

| |||

| CTSK | GAACCACTTGGGGGACATGA | 77 | NM_001034435.1 |

| GGGAACGAGAAGCGGGTACT | |||

|

| |||

| CTSS | CCGCCGTCAGCATTCTTAGT | 99 | NM_001033615.1 |

| CATGTGCCATTGCAGAGGAG | |||

|

| |||

| CTSZ | GGGGAGGGAGAAGATGATGG | 146 | NM_001077835.1 |

| CCACGGAGACGATGTGGTTT | |||

|

| |||

| BCL2 | GAGTTCGGAGGGGTCATGTG | 203 | NM_001166486.1 |

| GCCTTCAGAGACAGCCAGGA | |||

|

| |||

| BAX | GTGCCCGAGTTGATCAGGAC | 126 | NM_173894.1 |

| CCATGTGGGTGTCCCAAAGT | |||

|

| |||

| GAPDH | CACCCTCAAGATTGTCAGCA | 103 | NM_001034034.2 |

| GGTCATAAGTCCCTCCACGA | |||

2.6. In Vitro Fertilization and Embryo Culture

Procedures of in vitro fertilization and embryo culture were performed according to Torres et al. [33]. Briefly, for in vitro fertilization (for developmental capacity analysis), 16 pools of 25 COCs were washed in fertilization medium (modified Tyrode's medium (TALP) supplemented with 5.4 USP/mL heparin, 10 mM penicillamine (#P4875), 20 mM hypotaurine (#H1384), 0.25 mM epinephrine (#E1635), and 0.1 mg/mL gentamicin solution. For in vitro insemination, frozen-thawed semen was used. After thawing, semen was layered below capacitation medium (TALP medium supplemented with 72.72 mM pyruvic acid sodium pyruvate and 0.05 mg/mL gentamicin) and incubated for 1 h at 39°C in a 5% CO2 in humidified air atmosphere to allow the recovery of motile sperm through the swim-up procedure. After incubation, the upper two-thirds of the capacitation medium were recovered, centrifuged at 200 ×g for 10 min, the supernatant removed, and the sperm pellet diluted in an appropriate volume of fertilization medium to give a final concentration of 106 sperm/mL. Groups of 25 COCs were coincubated with spermatozoa in four-well dishes containing 400 μL of fertilization medium under 400 μL of mineral oil for 48 h at 39°C in a 5% CO2 humidified air atmosphere. The day of in vitro insemination was considered day 0. At 48 h postinsemination (hpi) embryos were separated from cumulus cells by vortexing and washed three times in wash medium. The cleavage rates were assessed and embryos with four or more cells were placed in four-well dishes containing 400 μL culture medium (SOF; synthetic oviductal fluid medium described by Holm et al. [37] supplemented with amino acids: 30 μL/mL BME (#B6766) and 10 μL/mL MEM (#M7145), 0.34 mM trisodium-citrate (#6448.1000, Merck Millipore, Germany), 2.77 mM myo-inositol (#I7508), 1 μL/mL gentamicin, 1 μL/mL ITS, and 5% v/v FCS) overlaid with 400 μL mineral oil. Culture was carried out at 39°C in a 5% CO2 in air with high humidity. Blastocyst numbers were determined on day 7 postinsemination. The rates of development to the blastocyst stage were calculated based on the total number of matured oocytes.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All data concerning expression patterns of target genes are presented as mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls' multiple comparison test was used to determine differences in mRNA expression of LPARs in oocytes and cumulus cells (GraphPad PRISM 6.0). Differences in transcription levels of the remaining genes were analyzed by Student's t-test for independent pairs. Cleavage and blastocyst rates were analyzed by Fisher's exact test. Differences were considered statistically significant at the 95% confidence level (P < 0.05).

3. Results

3.1. The Expression Patterns of LPARs (LPAR1, LPAR2, LPAR3, and LPAR4) and Enzymes Involved in LPA Synthesis (ATX and PLA2) in Oocytes and Cumulus Cells after In Vitro Maturation

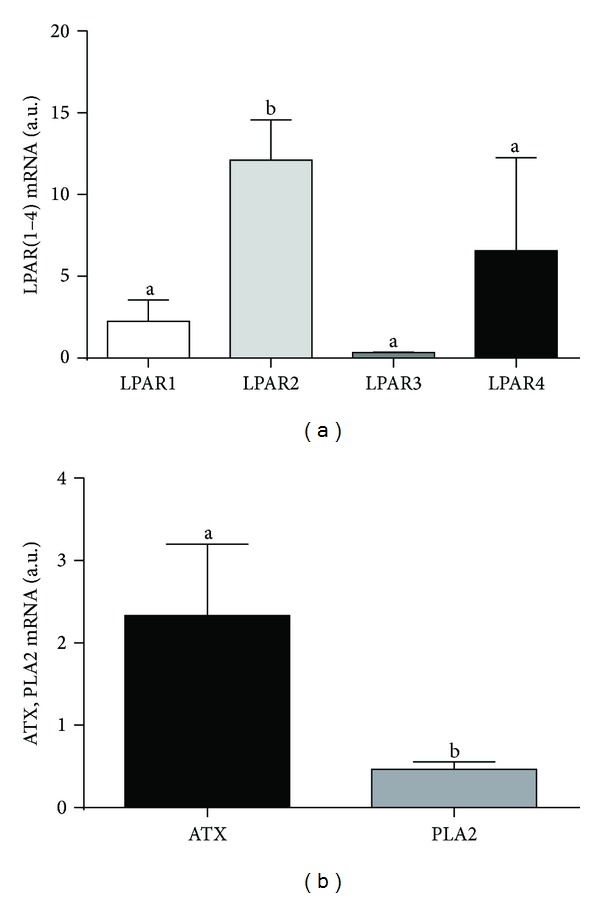

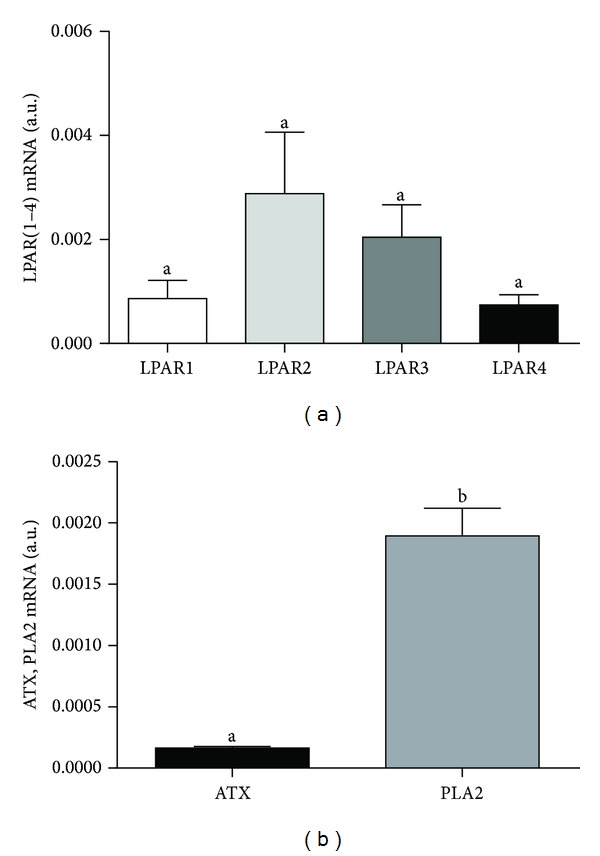

After in vitro maturation of COCs, oocytes and cumulus cells transcribe genes coding for enzymes involved in LPA synthesis (ATX and PLA2) as well as LPARs (Figures 1 and 2). We found significantly higher mRNA expression of LPAR2 than other three LPARs in bovine oocytes (Figure 1(a); P < 0.05). The expression of all examined LPARs in the cumulus cells did not significantly differ (Figure 2(a); P > 0.05). In the bovine oocytes the expression of ATX was higher than that of PLA2 (Figure 1(b); P < 0.05), whereas in cumulus cells the opposite was observed (Figure 2(b); P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

mRNA expression of (a) LPA receptors (LPAR1–4) and (b) autotaxin (ATX) and phospholipase A2 (PLA2) in oocytes. The values are expressed as mean ± SEM. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05), as determined by one-way ANOVA and Student's t-test, respectively.

Figure 2.

mRNA expression of (a) LPA receptors (LPAR1–4) and (b) autotaxin (ATX) and phospholipase A2 (PLA2) in cumulus cells. The values are expressed as mean ± SEM. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05), as determined by one-way ANOVA and Student's t-test, respectively.

3.2. Effect of LPA on mRNA Abundance of Oocyte Quality Markers and Genes Involved in Apoptosis in Oocytes and Cumulus Cells after In Vitro Maturation

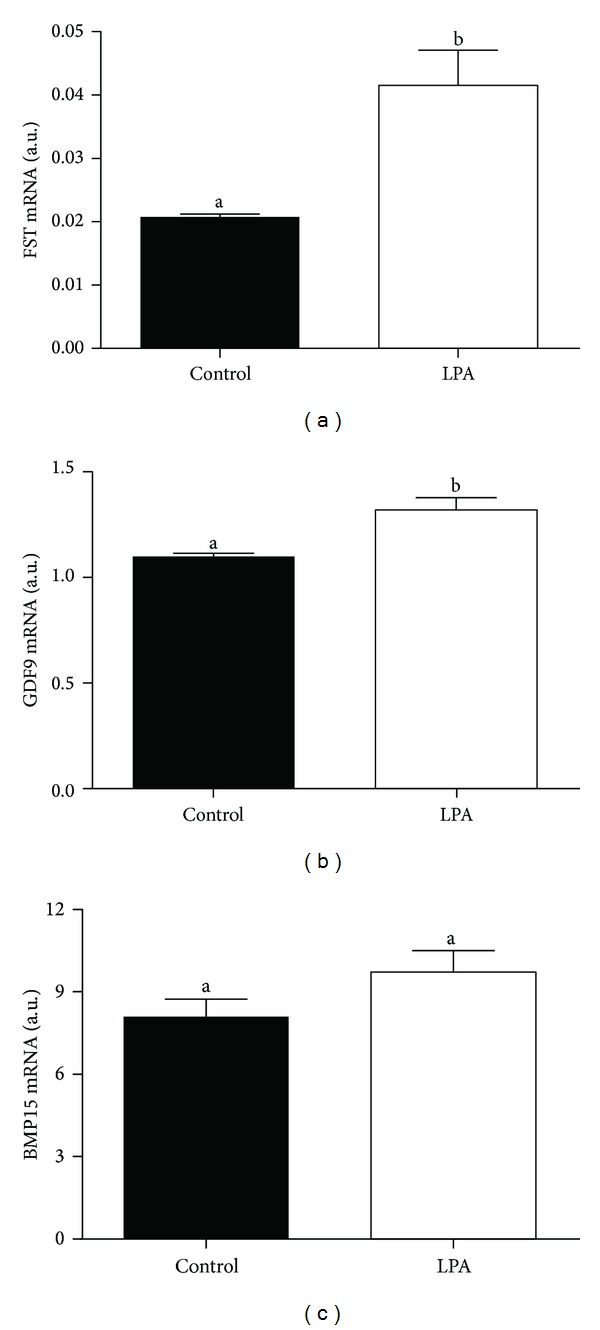

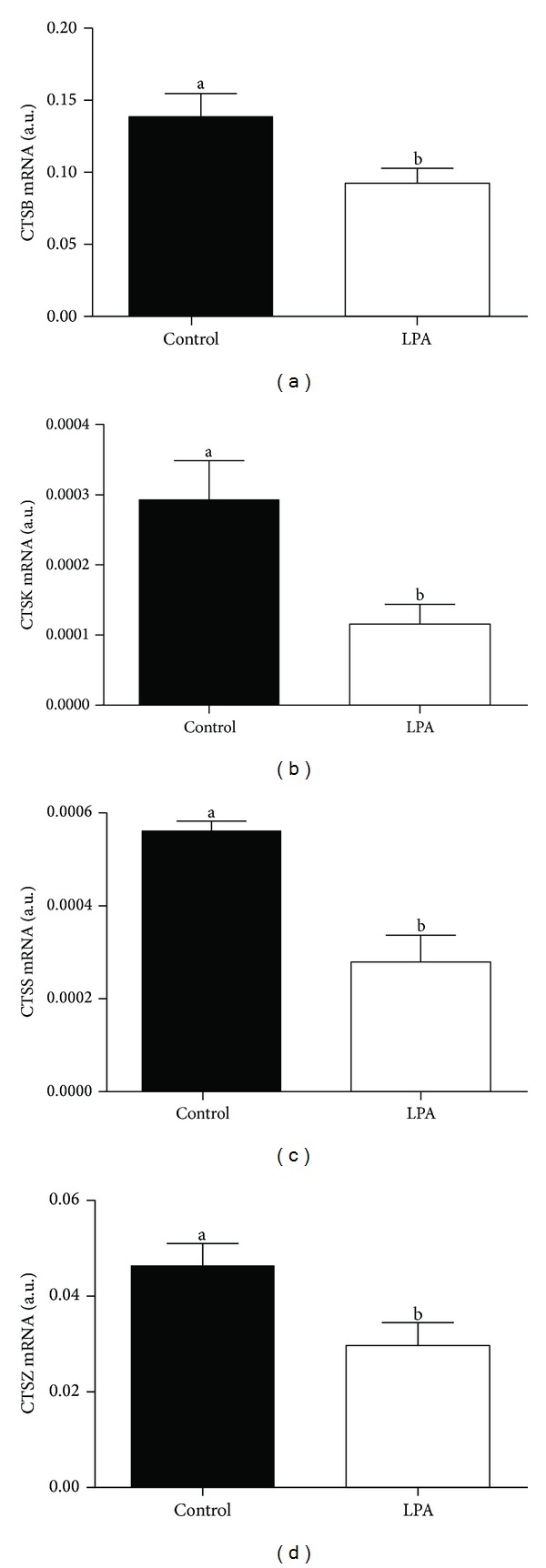

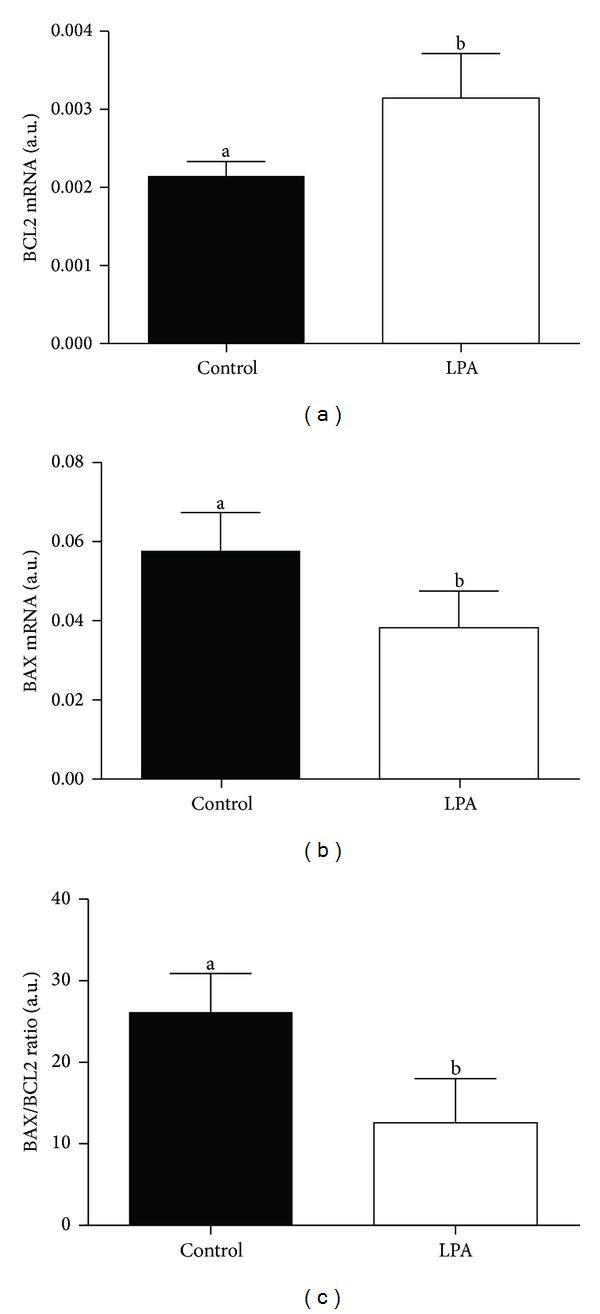

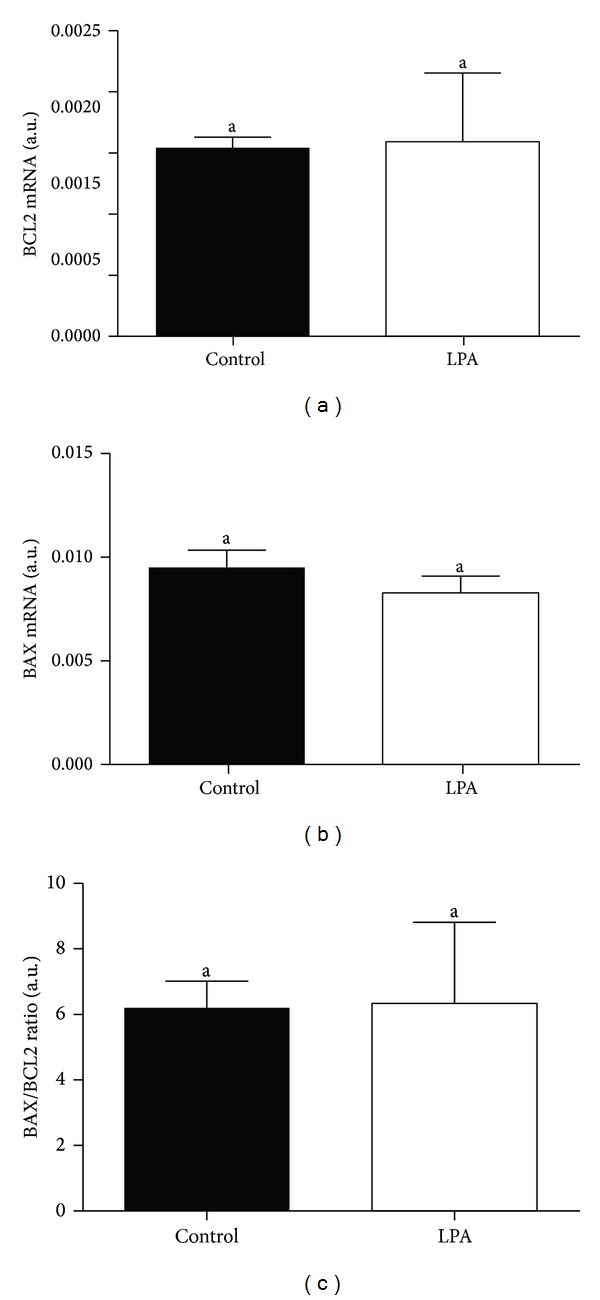

We found higher mRNA abundance of FST and GDF9 in the oocytes from the LPA-stimulated group compared to oocytes from the control group (Figures 3(a) and 3(b); P < 0.05). The supplementation of the maturation medium with LPA did not significantly influence BMP15 mRNA level in the examined oocytes (Figure 3(c); P > 0.05). In the cumulus cells there was lower mRNA abundance of all examined CTSs from the LPA-stimulated group compared to cumulus cells from the control group (Figure 4; P < 0.05). We demonstrated higher BCL2 and lower BAX mRNA level in the oocytes from the LPA-stimulated group compared to oocytes from the control group (Figures 5(a) and 5(b); P < 0.05). The BAX/BCL2 ratio was significantly lower in the oocytes matured in the presence of LPA compared to the oocytes from the control group (Figure 5(c); P < 0.05). The supplementation of the maturation medium with LPA did not significantly influence mRNA level of BCL2 and BAX or BAX/BCL2 ratio in the examined cumulus cells (Figure 6; P > 0.05).

Figure 3.

The effect of LPA (10−5 M) supplementation of maturation medium on mRNA abundance of FST (a), GDF9 (b), and BMP15 (c) in oocytes. The values are expressed as mean ± SEM. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05), as determined by Student's t-test.

Figure 4.

The effect of LPA (10−5 M) supplementation of maturation medium on mRNA abundance of CTSB (a), CTSK (b), CTSS (c), and CTSZ (d) in cumulus cells. The values are expressed as mean ± SEM. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05), as determined by Student's t-test.

Figure 5.

The effect of LPA (10−5 M) supplementation of maturation medium on mRNA abundance of BCL2 (a), BAX (b), and BAX/BCL2 ratio (c) in oocytes. The values are expressed as mean ± SEM. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05), as determined by Student's t-test.

Figure 6.

The effect of LPA (10−5 M) supplementation of maturation medium on mRNA abundance of BCL2 (a), BAX (b), and BAX/BCL2 ratio (c) in cumulus cells. The values are expressed as mean ± SEM. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05), as determined by Student's t-test.

3.3. Effect of LPA Supplementation of Maturation Medium on Embryonic Development

As shown in Table 2, we did not find any significant differences in the cleavage rates on day 2 between the control group and the LPA-stimulated group (61.7% versus 56.8%, resp.; P > 0.05). The blastocyst rates on day 7 were similar in the control group and the LPA-stimulated group (24.5% versus 28.4%, resp.; P > 0.05).

Table 2.

The effect of LPA supplementation of in vitro maturation medium on cleavage and blastocyst rates on day 2 and day 7, respectively.

| Supplement | Matured oocytes, n | Cleaved embryos, n | Cleavage rate, % | Blastocyst on day 7, n | Blastocyst rate, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (PBS) | 188 | 116 | 61,7 | 46 | 24,5 |

| LPA (10−5 M) | 190 | 108 | 56,8 | 54 | 28,4 |

Proportion of cleaved embryos and of blastocysts relative to the total number of matured oocytes.

4. Discussion

This study is the first to demonstrate mRNA expression of four types of LPARs and two main enzymes involved in LPA synthesis (ATX and PLA2) in bovine oocytes and cumulus cells. This indicates that bovine COCs are a potential source and target of LPA action and that LPA may be involved in cellular signaling between the oocyte and cumulus cells during maturation. Up to now, the presence of LPAR1 and LPAR2 was proposed only in the murine cumulus cells [35]. In mice it was also demonstrated that during blastocyst differentiation in vitro, embryos expressed LPAR1 mRNA constitutively, LPAR2 only in the late stage blastocysts, and there was no expression of LPAR3 [38]. However, van Meeteren et al. [39] demonstrated mRNA expression of four LPA receptors during murine embryonic development in vivo from E6.5 to E10.5 with significantly higher expression of LPAR1 than that of LPAR2–4. In ruminants, Liszewska et al. [17] showed that LPAR1, LPAR2, and LPAR3 transcripts were expressed in ovine conceptuses during early pregnancy and postulated the main role of LPAR1 and LPAR3 at the time of implantation. In cows, we documented the presence of LPAR1 in the endometrium and four isoforms of LPARs in the CL with the dominant function of LPAR2 and LPAR4 [19, 20]. Moreover, in bovine granulosa cells four types of LPARs were expressed with the highest transcript abundance of LPAR1 [21].

The transcript level of ATX mRNA was only identified during early embryo development in mouse and it was shown that the offspring of ATX-knockout mice died during embryonic development [39]. In sheep, Liszewska et al. [17] detected expression of ATX in embryonic trophectoderm from day 12 to day 16 of pregnancy. In our previous study, we demonstrated the presence of ATX and PLA2 in stromal and epithelial cells of the bovine endometrium as well as mRNA expression of ATX and PLA2 in granulosa cells [21, 40].

Considering that there is the possibility of LPA synthesis and action during in vitro maturation of COCs, in the second part of our study we examined the effect of LPA supplementation of maturation medium on mRNA abundance of the oocyte quality markers in oocytes and cumulus cells obtained after in vitro maturation. Supplementation of maturation medium with LPA increased oocyte GDF9 and FST transcripts, whereas BMP15 mRNA abundance was not affected. Morphological quality of oocytes can be depicted from the number and compactness of the neighboring cumulus cell layers [41]. Oocytes are responsible for cumulus cell expansion [42, 43], regulate steroid production [43–45], and maintain cumulus cell phenotype [45]. This is accomplished through the paracrine secretion of factors, which include TGF-β superfamily members, notably GDF9 and BMP15, also known as GDF-9B [46–48]. In cow, BMP15 and GDF9 transcription occur in oocyte during processes of in vitro maturation and fertilization and in preimplantation embryos until the five- to eight-cell or morula stage as well as in high quality oocytes [49–51]. Therefore, BMP15 and GDF9 are considered valid oocyte quality marker genes [50–52]. Moreover, Gendelman et al. [50] found that mRNA expression of GDF9 was higher in early- versus late-cleaved embryos. Gendelman and Roth [51] documented higher GDF9 transcript level in matured oocytes collected in the cold season than in those from the hot season and postulated that seasonally induced alterations in GDF9 expression were involved in the reduced developmental competence noted for oocytes collected in the hot season. In fact, addition of BMP15 and GDF9 to maturation medium enhanced oocyte developmental competence in the cow [52]. Oocyte mRNA abundance of FST was associated with time of the first cleavage that accounted for high developmental competence of the oocyte [53]. Moreover, Lee et al. [54] showed higher level of FST protein in early versus late cleaving two-cell embryos and the stimulatory effects of FST on time to first cleavage, blastocyst rate, and cell allocation within the blastocyst. Here, increased transcription levels of GDF9 and FST following LPA supplementation during in vitro maturation may indicate that LPA increased oocyte competence.

The role of cumulus cells during in vitro maturation is vital for oocyte maturation and subsequent fertilization and embryo development [55, 56]. Cumulus cells play a pivotal role in the provision of nutrients to the oocyte [57, 58] as well as stimulate oocyte glutathione synthesis [59]. Therefore, gene expression in cumulus cells may also reflect oocyte quality and competence. Bettegowda et al. [60] demonstrated negative correlation between CTSs transcript abundance in cumulus cells and oocyte quality as well as their developmental competence. Here, LPA supplementation of maturation medium decreased cumulus cell transcript levels of CTSB, CTSK, CTSS, and CTSZ. Again, this may indicate that LPA increased oocyte competence.

LPA supplementation of maturation medium had no effect on transcription levels of proapoptotic (BAX) and antiapoptotic (BCL2) genes in cumulus cells but decreased oocyte BAX mRNA abundance and increased oocyte BCL2 transcript levels. Moreover, the BAX/BCL2 ratio was lower in the oocytes matured in the presence of LPA compared to the oocytes from the control group. Apoptosis in cumulus cells may be also a good marker of oocyte developmental competence [61] due to the bidirectional communication between oocytes and cumulus cells [62]. Cumulus cells regulate nuclear and cytoplasmic maturation of oocytes and prevent apoptosis induced by oxidative stress during in vitro maturation [63, 64]. However, the relationship between the occurrence of apoptosis in cumulus cells and oocyte developmental competence is controversial [65–69]. In fact, some studies report that oocytes with early signs of atresia are developmentally more competent [70, 71]. Oocytes with the highest transcriptional level of BAX and the lowest mRNA level of BCL2 exhibited the highest nuclear maturation, cleavage, and blastocyst rate [71]. In contrast, in other studies, good quality oocytes showed the highest transcription levels of BCL2 and the lowest mRNA abundance of BAX [72]. The ratio of BCL2 to BAX may be an indicator of the tendency of oocytes and embryos towards either survival or apoptosis [72]. According to Yuan et al. [73] COCs with no signs of atresia yield higher blastocyst rates. The authors found that the degree of apoptosis in the cumulus cells is negatively correlated to the developmental competence of oocyte [73]. On the other hand, another group of authors demonstrated that the level of apoptosis in cumulus cells does not correlate either with COC morphology or oocyte meiotic stage [74]. Here, LPA decreased BAX/BCL2 ratio, indicating that an antiapoptotic balance was induced in the oocyte, which may be relevant for oocyte competence. Hussein et al. [75] showed that, at the beginning, the apoptotic signal appears in the cumulus cells and then in the oocyte. Similarly, we have detected an antiapoptotic effect of LPA in cultured luteal cells: LPA inhibited the stimulatory effects of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) and interferon gamma (IFNγ) on the expression of BAX mRNA and protein in steroidogenic luteal cells [76].

Although, LPA supplementation of maturation medium promoted transcription of quality marker genes in oocytes, decreased transcription of CTSs in cumulus cells, and induced and antiapoptotic balance in oocytes, this was not translated into a higher number of cleaved embryos and subsequent blastocyst development. Ye et al. [77] examined the influence of LPA on the embryo implantation in LPA3 receptor null mice. According to these authors, examined mice exhibited delayed implantation, reduced number of implantation sites, delayed embryonic development, and increased embryonic mortality [77]. However, we did not examine the effect of LPA on the implantation of bovine embryos. Moreover, we cannot exclude that LPA supplementation of maturation medium can impact the maturation process itself and/or early pronuclear stages of embryo development. In rodents, LPA promoted nuclear and cytoplasmic oocyte maturation via cumulus cells and through the closure or loosening of gap junctions between cumulus cells and the oocyte [35, 36], as well as stimulated blastocyst development [38, 78, 79]. Differences in early embryonic development between the mouse and bovine models may account for the discrepancy in the rate of blastocyst development observed in our study and in the studies with rodents. Further studies are needed to evaluate the role of LPA stimulation during in vitro maturation and embryo culture in in vivo survival of bovine embryos.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates for the first time that bovine COCs (both oocytes and cumulus cells) are a potential source and target of LPA action. We postulate that LPA exerts an autocrine and/or paracrine signaling, through several LPARs, between the oocyte and cumulus cells. LPA supplementation of maturation medium increases oocyte transcripts of quality marker genes (FST and GDF9), promotes an antiapoptotic balance in transcription of genes involved in apoptosis (BCL2 and BAX), and decreases cumulus cells transcripts associated with low viability (CTSs). These effects, although not affecting in vitro development until the blastocyst stage, may be of relevance for subsequent in vivo developmental competence.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Polish National Science Centre (2012/05/E/NZ9/03480). This research was founded by a Grant from the Foundation for Science and Technology PTDC/CVT/65690/2006. Dorota Boruszewska and Ilona Kowalczyk-Zieba were supported by the European Union within the European Social Fund (DrINNO3).

Disclosure

The data presented in the manuscript are the part of PhD Thesis of Dorota Boruszewska.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Authors' Contribution

Dorota Boruszewska and Ana Catarina Torres contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Ye X, Chun J. Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) signaling in vertebrate reproduction. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2010;21(1):17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goetzl EJ, Dolezalova H, Kong Y, et al. Distinctive expression and functions of the type 4 endothelial differentiation gene-encoded G protein-coupled receptor for lysophosphatidic acid in ovarian cancer. Cancer Research. 1999;59(20):5370–5375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spohr TC, Choi JW, Gardell SE, et al. Lysophosphatidic acid receptor-dependent secondary effects via astrocytes promote neuronal differentiation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(12):7470–7479. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707758200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiner JA, Chun J. Schwann cell survival mediated by the signaling phospholipid lysophosphatidic acid. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(9):5233–5238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ye X, Skinner MK, Kennedy G, Chun J. Age-dependent loss of sperm production in mice via impaired lysophosphatidic acid signaling. Biology of Reproduction. 2008;79(2):328–336. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.068783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Härmä V, Knuuttila M, Virtanen J, et al. Lysophosphatidic acid and sphingosine-1-phosphate promote morphogenesis and block invasion of prostate cancer cells in three-dimensional organotypic models. Oncogene. 2012;31(16):2075–2089. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang M-C, Lee H-Y, Yeh C-C, Kong Y, Zaloudek CJ, Goetzl EJ. Induction of protein growth factor systems in the ovaries of transgenic mice overexpressing human type 2 lysophosphatidic acid G protein-coupled receptor (LPA2) Oncogene. 2004;23(1):122–129. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aoki J. Mechanisms of lysophosphatidic acid production. Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2004;15(5):477–489. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakamura K, Kishimoto T, Ohkawa R, et al. Suppression of lysophosphatidic acid and lysophosphatidylcholine formation in the plasma in vitro: proposal of a plasma sample preparation method for laboratory testing of these lipids. Analytical Biochemistry. 2007;367(1):20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bandoh K, Aoki J, Hosono H, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel human G-protein- coupled receptor, EDG7, for lysophosphatidic acid. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(39):27776–27785. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Im D-S, Heise CE, Harding MA, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of a lysophosphatidic acid receptor, Edg-7, expressed in prostate. Molecular Pharmacology. 2000;57(4):753–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noguchi K, Ishii S, Shimizu T. Identification of p2y9/GPR23 as a novel G protein-coupled receptor for lysophosphatidic acid, structurally distant from the Edg family. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(28):25600–25606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302648200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aoki J, Inoue A, Okudaira S. Two pathways for lysophosphatidic acid production. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2008;1781(9):513–518. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McIntyre TM, Pontsler AV, Silva AR, et al. Identification of an intracellular receptor for lysophosphatidic acid (LPA): LPA is a transcellular PPARγ agonist. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(1):131–136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0135855100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okudaira S, Yukiura H, Aoki J. Biological roles of lysophosphatidic acid signaling through its production by autotaxin. Biochimie. 2010;92(6):698–706. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jarvis AA, Cain C, Dennis EA. Purification and characterization of a lysophospholipase from human amnionic membranes. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1984;259(24):15188–15195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liszewska E, Reinaud P, Billon-Denis E, Dubois O, Robin P, Charpigny G. Lysophosphatidic acid signaling during embryo development in sheep: involvement in prostaglandin synthesis. Endocrinology. 2009;150(1):422–434. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woclawek-Potocka I, Kowalczyk-Zieba I, Skarzynski DJ. Lysophosphatidic acid action during early pregnancy in the cow: in vivo and in vitro studies. The Journal of Reproduction and Development. 2010;56(4):411–420. doi: 10.1262/jrd.09-205k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woclawek-Potocka I, Komiyama J, Saulnier-Blache JS, et al. Lysophosphatic acid modulates prostaglandin secretion in the bovine uterus. Reproduction. 2009;137(1):95–105. doi: 10.1530/REP-08-0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kowalczyk-Zieba I, Boruszewska D, Saulnier-Blache JS, et al. Lysophosphatidic acid action in the bovine corpus luteum—an in vitro study. The Journal of Reproduction and Development. 2012;58(6):661–671. doi: 10.1262/jrd.2012-060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boruszewska D, Sinderewicz E, Kowalczyk-Zieba I, Skarzynski DJ, Woclawek-Potocka I. Influence of lysophosphatidic acid on estradiol production and follicle stimulating hormone action in bovine granulosa cells. Reproductive Biology. 2013;13(4):344–347. doi: 10.1016/j.repbio.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woclawek-Potocka I, Kondraciuk K, Skarzynski DJ. Lysophosphatidic acid stimulates prostaglandin E2 production in cultured stromal endometrial cells through LPA1 receptor. Experimental Biology and Medicine. 2009;234(8):986–993. doi: 10.3181/0901-RM-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sorensen RA, Wassarman PM. Relationship between growth and meiotic maturation of the mouse oocyte. Developmental Biology. 1976;50(2):531–536. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(76)90172-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wickramasinghe D, Ebert KM, Albertini DF. Meiotic competence acquisition is associated with the appearance of M-phase characteristics in growing mouse oocytes. Developmental Biology. 1991;143(1):162–172. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(91)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eppig JJ, Schultz RM, O’Brien M, Chesnel F. Relationship between the developmental programs controlling nuclear and cytoplasmic maturation of mouse oocytes. Developmental Biology. 1994;164(1):1–9. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Payne C, Schatten G. Golgi dynamics during meiosis are distinct from mitosis and are coupled to endoplasmic reticulum dynamics until fertilization. Developmental Biology. 2003;264(1):50–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torner H, Brüssow K-P, Alm H, et al. Mitochondrial aggregation patterns and activity in porcine oocytes and apoptosis in surrounding cumulus cells depends on the stage of pre-ovulatory maturation. Theriogenology. 2004;61(9):1675–1689. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2003.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Vantéry C, Gavin AC, Vassalli JD, Schorderet-Slatkine S. An accumulation of p34cdc2 at the end of mouse oocyte growth correlates with the acquisition of meiotic competence. Developmental Biology. 1996;174(2):335–344. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krischek C, Meinecke B. In vitro maturation of bovine oocytes requires polyadenylation of mRNAs coding proteins for chromatin condensation, spindle assembly, MPF and MAP kinase activation. Animal Reproduction Science. 2002;73(3-4):129–140. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4320(02)00131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carabatsos MJ, Sellitto C, Goodenough DA, Albertini DF. Oocyte-granulosa cell heterologous gap junctions are required for the coordination of nuclear and cytoplasmic meiotic competence. Developmental Biology. 2000;226(2):167–179. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de La Fuente R, Eppig JJ. Transcriptional activity of the mouse oocyte genome: companion granulosa cells modulate transcription and chromatin remodeling. Developmental Biology. 2001;229(1):224–236. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reynaud K, Cortvrindt R, Smitz J, Driancourt MA. Effects of Kit Ligand and anti-Kit antibody on growth of cultured mouse preantral follicles. Molecular Reproduction and Development. 2000;56(4):483–494. doi: 10.1002/1098-2795(200008)56:4<483::AID-MRD6>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Torres A, Batista M, Diniz P, Mateus L, Lopes-da-Costa L. Embryo-luteal cells co-culture: an in vitro model to evaluate steroidogenic and prostanoid bovine early embryo-maternal interactions. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology. 2013;49(2):134–146. doi: 10.1007/s11626-012-9577-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tokumura A, Miyake M, Nishioka Y, Yamano S, Aono T, Fukuzawa K. Production of lysophosphatidic acids by lysophospholipase D in human follicular fluids of in vitro fertilization patients. Biology of Reproduction. 1999;61(1):195–199. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod61.1.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Komatsu J, Yamano S, Kuwahara A, Tokumura A, Irahara M. The signaling pathways linking to lysophosphatidic acid-promoted meiotic maturation in mice. Life Sciences. 2006;79(5):506–511. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hinokio K, Yamano S, Nakagawa K, et al. Lysophosphatidic acid stimulates nuclear and cytoplasmic maturation of golden hamster immature oocytes in vitro via cumulus cells. Life Sciences. 2002;70(7):759–767. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01448-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holm P, Booth PJ, Schmidt MH, Greve T, Callesen H. High bovine blastocyst development in a static in vitro production system using SOFaa medium supplemented with sodium citrate and myo-inositol with or without serum-proteins. Theriogenology. 1999;52(4):683–700. doi: 10.1016/S0093-691X(99)00162-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Z, Armant DR. Lysophosphatidic acid regulates murine blastocyst development by transactivation of receptors for heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor. Experimental Cell Research. 2004;296(2):317–326. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Meeteren LA, Ruurs P, Stortelers C, et al. Autotaxin, a secreted lysophospholipase D, is essential for blood vessel formation during development. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2006;26(13):5015–5022. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02419-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boruszewska D, Kowalczyk-Zieba I, Piotrowska-Tomala K, et al. Which bovine endometrial cells are source and target for lysophosphatidic acid? Reproductive Biology. 2013;13(1):100–103. doi: 10.1016/j.repbio.2013.01.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amer HA, Hegab A-RO, Zaabal SM. Some studies on the morphological aspects of buffalo oocytes in relation to the ovarian morphology and culture condition. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s11626-009-9224-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buccione R, Vanderhyden BC, Caron PJ, Eppig JJ. FSH-induced expansion of the mouse cumulus oophorus in vitro is dependent upon a specific factor(s) secreted by the oocyte. Developmental Biology. 1990;138(1):16–25. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(90)90172-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elvin JA, Clark AT, Wang P, Wolfman NM, Matzuk MM. Paracrine actions of growth differentiation factor-9 in the mammalian ovary. Molecular Endocrinology. 1999;13(6):1035–1048. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.6.0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vanderhyden BC, Tonary AM. Differential regulation of progesterone and estradiol production by mouse cumulus and mural granulosa cells by a factor(s) secreted by the oocyte. Biology of Reproduction. 1995;53(6):1243–1250. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod53.6.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li R, Norman RJ, Armstrong DT, Gilchrist RB. Oocyte-secreted factor(s) determine functional differences between bovine mural granulosa cells and cumulus cells. Biology of Reproduction. 2000;63(3):839–845. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.3.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carabatsos MJ, Elvin J, Matzuk MM, Albertini DF. Characterization of oocyte and follicle development in growth differentiation factor-9-deficient mice. Developmental Biology. 1998;204(2):373–384. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Otsuka F, Yao Z, Lee T-H, Yamamoto S, Erickson GF, Shimasaki S. Bone morphogenetic protein-15: identification of target cells and biological functions. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(50):39523–39528. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007428200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Juengel JL, Hudson NL, Heath DA, et al. Growth differentiation factor 9 and bone morphogenetic protein 15 are essential for ovarian follicular development in sheep. Biology of Reproduction. 2002;67(6):1777–1789. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.007146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pennetier S, Uzbekova S, Perreau C, Papillier P, Mermillod P, Dalbiès-Tran R. Spatio-temporal expression of the germ cell marker genes MATER, ZAR1, GDF9, BMP15, and VASA in adult bovine tissues, oocytes, and preimplantation embryos. Biology of Reproduction. 2004;71(4):1359–1366. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.030288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gendelman M, Aroyo A, Yavin S, Roth Z. Seasonal effects on gene expression, cleavage timing, and developmental competence of bovine preimplantation embryos. Reproduction. 2010;140(1):73–82. doi: 10.1530/REP-10-0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gendelman M, Roth Z. In vivo vs. in vitro models for studying the effects of elevated temperature on the GV-stage oocyte, subsequent developmental competence and gene expression. Animal Reproduction Science. 2012;134(3):125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hussein TS, Thompson JG, Gilchrist RB. Oocyte-secreted factors enhance oocyte developmental competence. Developmental Biology. 2006;296(2):514–521. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patel OV, Bettegowda A, Ireland JJ, Coussens PM, Lonergan P, Smith GW. Functional genomics studies of oocyte competence: evidence that reduced trascript abundance for follistatin is associated with poor developmental competence of bovine oocytes. Reproduction. 2007;133(1):95–106. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.01123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee K-B, Bettegowda A, Wee G, Ireland JJ, Smith GW. Molecular determinants of oocyte competence: potential functional role for maternal (oocyte-derived) follistatin in promoting bovine early embryogenesis. Endocrinology. 2009;150(5):2463–2471. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fukui Y, Sakuma Y. Maturation of bovine oocytes cultured in vitro: relation to ovarian activity, follicular size and the presence or absence of cumulus cells. Biology of Reproduction. 1980;22(3):669–673. doi: 10.1093/biolreprod/22.3.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fatehi AN, Zeinstra EC, Kooij RV, Colenbrander B, Bevers MM. Effect of cumulus cell removal of in vitro matured bovine oocytes prior to in vitro fertilization on subsequent cleavage rate. Theriogenology. 2002;57(4):1347–1355. doi: 10.1016/s0093-691x(01)00717-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sutton-McDowall ML, Gilchrist RB, Thompson JG. Cumulus expansion and glucose utilisation by bovine cumulus-oocyte complexes during in vitro maturation: the influence of glucosamine and follicle-stimulating hormone. Reproduction. 2004;128(3):313–319. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Preis KA, Seidel G, Jr., Gardner DK. Metabolic markers of developmental competence for in vitro-matured mouse oocytes. Reproduction. 2005;130(4):475–483. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.de Matos DG, Furnus CC, Moses DF. Glutathione synthesis during in vitro maturation of bovine oocytes: role of cumulus cells. Biology of Reproduction. 1997;57(6):1420–1425. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod57.6.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bettegowda A, Patel OV, Lee K-B, et al. Identification of novel bovine cumulus cell molecular markers predictive of oocyte competence: functional and diagnostic implications. Biology of Reproduction. 2008;79(2):301–309. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.067223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Corn CM, Hauser-Kronberger C, Moser M, Tews G, Ebner T. Predictive value of cumulus cell apoptosis with regard to blastocyst development of corresponding gametes. Fertility and Sterility. 2005;84(3):627–633. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.de Loos F, Kastrop P, van Maurik P, van Beneden TH, Kruip TA. Heterologous cell contacts and metabolic coupling in bovine cumulus oocyte complexes. Molecular Reproduction and Development. 1991;28(3):255–259. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080280307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tanghe S, van Soom A, Nauwynck H, Coryn M, de Kruif A. Minireview: functions of the cumulus oophorus during oocyte maturation, ovulation, and fertilization. Molecular Reproduction and Development. 2002;61(3):414–424. doi: 10.1002/mrd.10102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tatemoto H, Sakurai N, Muto N. Protection of porcine oocytes against apoptotic cell death caused by oxidative stress during in vitro maturation: role of cumulus cells. Biology of Reproduction. 2000;63(3):805–810. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.3.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mikkelsen AL, Høst E, Lindenberg S. Incidence of apoptosis in granulosa cells from immature human follicles. Reproduction. 2001;122(3):481–486. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1220481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kölle S, Stojkovic M, Boie G, Wolf E, Sinowatz F. Growth hormone-related effects on apoptosis, mitosis, and expression of connexin 43 in bovine in vitro maturation cumulus-oocyte complexes. Biology of Reproduction. 2003;68(5):1584–1589. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.010264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Szołtys M, Tabarowski Z, Pawlik A. Apoptosis of postovulatory cumulus granulosa cells of the rat. Anatomy and Embryology. 2000;202(6):523–529. doi: 10.1007/s004290000122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Manabe N, Imai Y, Ohno H, Takahagi Y, Sugimoto M, Miyamoto H. Apoptosis occurs in granulosa cells but not cumulus cells in the atretic antral follicles in pig ovaries. Experientia. 1996;52(7):647–651. doi: 10.1007/BF01925566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang MY, Rajamahendran R. Morphological and biochemical identification of apoptosis in small, medium, and large bovine follicles and the effects of follicle-stimulating hormone and insulin-like growth factor-I on spontaneous apoptosis in cultured bovine granulosa cells. Biology of Reproduction. 2000;62(5):1209–1217. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod62.5.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bilodeau-Goeseels S, Panich P. Effects of oocyte quality on development and transcriptional activity in early bovine embryos. Animal Reproduction Science. 2002;71(3-4):143–155. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4320(01)00188-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li HJ, Liu DJ, Cang M, et al. Early apoptosis is associated with improved developmental potential in bovine oocytes. Animal Reproduction Science. 2009;114(1–3):89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang MY, Rajamahendran R. Expression of Bcl-2 and Bax proteins in relation to quality of bovine oocytes and embryos produced in vitro. Animal Reproduction Science. 2002;70(3-4):159–169. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4320(01)00186-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yuan YQ, van Soom A, Leroy JLMR, et al. Apoptosis in cumulus cells, but not in oocytes, may influence bovine embryonic developmental competence. Theriogenology. 2005;63(8):2147–2163. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2004.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Warzych E, Pers-Kamczyc E, Krzywak A, Dudzińska S, Lechniak D. Apoptotic index within cumulus cells is a questionable marker of meiotic competence of bovine oocytes matured in vitro. Reproductive Biology. 2013;13(1):82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.repbio.2013.01.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hussein TS, Froiland DA, Amato F, Thompson JG, Gilchrist RB. Oocytes prevent cumulus cell apoptosis by maintaining a morphogenic paracrine gradient of bone morphogenetic proteins. Journal of Cell Science. 2005;118(22):5257–5268. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Woclawek-Potocka I, Kowalczyk-Zieba I, Tylingo M, Boruszewska D, Sinderewicz E, Skarzynski DJ. Effects of lysophopatidic acid on tumor necrosis factor α and interferon γ action in the bovine corpus luteum. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2013;377(1-2):103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ye X, Hama K, Contos JJA, et al. LPA3-mediated lysophosphatidic acid signalling in embryo implantation and spacing. Nature. 2005;435(7038):104–108. doi: 10.1038/nature03505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kobayashi T. Effect of lysophosphatidic acid on the preimplantation development of mouse embryos. FEBS Letters. 1994;351(1):38–40. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00815-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jo JW, Jee BC, Suh CS, Kim SH. Addition of lysophosphatidic acid to mouse oocyte maturation media can enhance fertilization and developmental competence. Human Reproduction. 2014;29(2):234–241. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]