Abstract

Significance: Molecular oxygen is a Janus-faced electron acceptor for biological systems, serving as a reductant for respiration, or as the genesis for oxygen-derived free radicals that damage macromolecules. Superoxide is well known to perturb nonheme iron proteins, including Fe/S proteins such as aconitase and succinate dehydrogenase, as well as other enzymes containing labile iron such as the prolyl hydroxylase domain-containing family of enzymes; whereas hydrogen peroxide is more specific for two-electron reactions with thiols on glutathione, glutaredoxin, thioredoxin, and the peroxiredoxins. Recent Advances: Over the past two decades, familial cases of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) have been shown to have an association with commonly altered superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) activity, expression, and protein structure. This has led to speculation that an altered redox balance may have a role in creating the ALS phenotype. Critical Issues: While SOD1 alterations in familial ALS are manifold, they generally create perturbations in the flux of electrons. The nexus of SOD1 between one- and two-electron signaling processes places it at a key signaling regulatory checkpoint for governing cellular responses to physiological and environmental cues. Future Directions: The manner in which ALS-associated mutations adjust SOD1's role in controlling the flow of electrons between one- and two-electron signaling processes remains obscure. Here, we discuss the ways in which SOD1 mutations influence the form and function of copper zinc SOD, the consequences of these alterations on free radical biology, and how these alterations might influence cell signaling during the onset of ALS. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 20, 1590–1598.

Introduction

This discovery of oxygen containing free radicals in biological materials by Townsend, Commoner, and Pake in the 1950s raised several questions about their existence (10). Life in oxygen affords cells with a suitable reductant substrate with which to facilitate numerous biological reactions, including oxidative phosphorylation, cell signaling, and mounting an immune response. The addition of one electron to oxygen generates superoxide anion (O2•−), which is made as either a product or byproduct. As a product, superoxide is generated by endogenous oxidases with a multitude of biological objectives ranging from cellular defense to redox signaling pathways. Superoxide becomes a byproduct during the incomplete reduction of oxygen during oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondria. In both roles, O2•− has been speculated to influence diverse biological events, including cancer, aging, neurodegenerative disorders, and development. When the first superoxide dismutase (SOD) was discovered by McCord and Fridovich in the 1960s, the understanding of the function of O2•− in biology became more complex (36). Superoxide is generally labeled as a toxic species with SODs labeled as their “detoxifiers.” However, a more sophisticated perspective of superoxide can be held if we designate these enzymes as modifiers of superoxide function by regulating the flux of superoxide, rather than prescribing to them the diminutive role of free radical scavengers. Eukaryotic compartmentalization allows superoxide to exist in varying steady state levels within the same cell. Mammalian cells have three identified SODs: manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD), extracellular superoxide dismutase (ECSOD), and copper zinc superoxide dismutase (CuZnSOD), the last which will be the subject of this review. Alterations to the activities of these enzymes can have varying effects on the superoxide's function and be the etiology of numerous pathologies.

CuZnSOD, or SOD1, is a soluble protein that catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide in numerous subcellular compartments (52, 73). SOD1 was originally designated erythrocuprein, a copper storage protein with no known enzymatic activity. Since the discovery of SOD1's superoxide dismutase activity by McCord and Fridovich, several human conditions and pathologies have been associated with alterations in its function. SOD1 alterations have been shown to be associated with aging, cancer, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). ALS is a motor neuron disease that generally exhibits adult onset. Originally, it was suggested that roughly 20% percent of ALS cases are associated with mutations in SOD1 (58). Today, this estimate has been refined to ∼7% of ALS patients having SOD1 mutations (1). This realization has greatly increased our understanding of ALS, and the mechanisms that might be responsible for its manifestation. In this review, we will specifically address the ways in which alterations can influence the form and function of CuZnSOD, the consequences of these alterations on free radical biology, and how these alterations might influence cell signaling during the onset of ALS.

SOD1 Gene

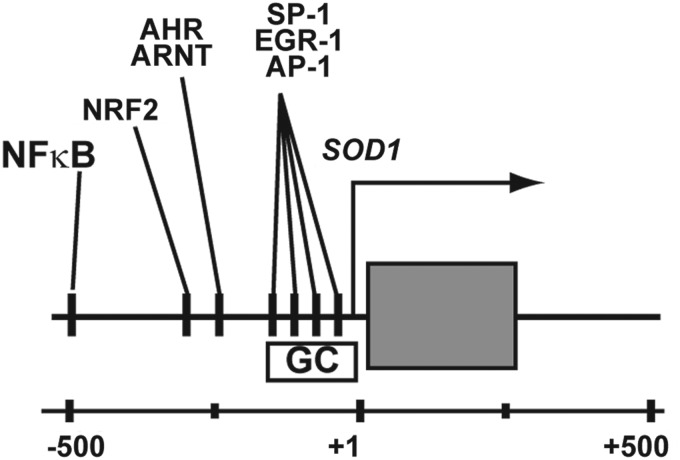

The gene encoding human CuZnSOD, SOD1, resides on chromosome 21q22.1 of the human genome. SOD1's association with multiple disease phenotypes has led to extensive characterization of the transcription factors that bind this region. The gene is ubiquitously expressed at a relatively high level in human tissues, an attribute that is facilitated by these generic transcriptional regulatory elements. The SOD1 gene contains numerous genetic features that are conserved across several eukaryotic species, and suggest they are required for the gene's function. A proximal promoter containing a TATA box, GC-rich region, and a CCAAT motif mediates basal expression of SOD1. Bona fide binding sites for activator protein 1 (AP-1), specificity protein 1 (SP-1), and early growth response 1 (EGR-1) are within the CG-rich domain of the proximal promoter (27) (Fig. 1). These elements are common to eukaryotic genes, and they are likely the mechanical factors that are responsible for driving SOD1's universal expression in all tissues and cell types.

FIG. 1.

Molecular genetic structure of the 5′-regulatory region of the human SOD1 gene that encodes CuZnSOD. Numerous cis-regulatory elements for common transcription factors are present in this region, some experimentally documented to be functional and others remaining as uncharacterized “putative” response elements. SOD1, superoxide dismutase 1; CuZnSOD, copper zinc superoxide dismutase.

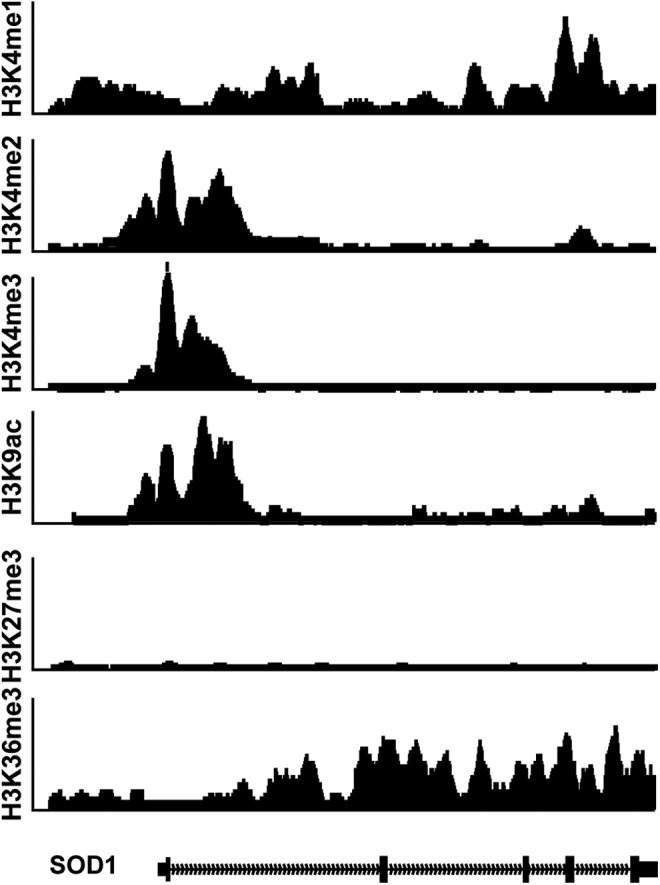

SOD1 transcription can also be induced following numerous abiotic and biotic stimuli via the activation of other accessory cis-regulatory elements. These enhancer-like elements in SOD1 are located upstream from its transcriptional start site. Again, SOD1's association with human disease has led to the thorough characterization of these DNA elements (Fig. 1). A majority of inducible SOD1 expression is facilitated by the binding of nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB), nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (NRF2), aryl hydrocarbon receptor/aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (AHR/ARNT), and CAATT enhancer binding proteins (C/EBP) transcription factors to enhancer regions of SOD1 (38, 40, 47). For example, NFκB binding the human SOD1 promoter increases after exposure to cytokines, oxidative stress, and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (32, 40). Likewise, cellular stress leads to the swift localization of NRF2 to the nucleus to increase the expression of genes such as SOD1. Similar mechanisms lead to the transcriptional activation of SOD1 by increasing the binding of AHR/ARNT and C/EBP at the proximal promoter. As a part of the encyclopedia of DNA elements (ENCODE) project, several histone modifications have been mapped to the entire genome of numerous cell lines using Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-Seq). The confluence of these efforts provides a qualitative view of the “epigenetic landscape” of SOD1 in model cell lines (Fig. 2). The presence of H3K4me3, and H3K9ac at a gene's basal promoter, as well as H3K36me3 within its coding region, are hallmarks of a gene that is actively expressed (54, 60). Both these histone modifications are present at SOD1 in numerous cell lines (Fig. 2). Likewise, the cis-elements of SOD1 bound by NFκB, NRF2, AHR/ARNT, and C/EPB are enriched with H3K4me2 modified histones, a modification that is synonymous with enhancers (48, 57). Combined, SOD1's transcriptional regulatory elements not only govern its basal expression in all tissues, but also mobilize increased levels of CuZnSOD activity in response to pro-oxidants, toxins, and cytokines. While these studies suggest that SOD1 expression may be altered following some exogenous stimuli, it should also be noted that the production of a fully formed, active CuZnSOD dimer formation by post-translational processing may facilitate another means by which dismutase activity can be altered in cells.

FIG. 2.

ChIP-Seq tracks from the ENCODE project showing the localization of various modified histone markers along the human SOD1 gene. The gene possesses an epigenetic landscape that is consistent with a constitutively expressed gene in all cell and tissue types. ENCODE, encyclopedia of DNA elements.

ALS-Associated Changes in Expression

Thus far, studies testing an association between SOD1 gene activity and the development of ALS have produced mixed results. An early study noted that of SOD1 mRNA levels in the motor, neurons of sporadic and familial cases were not significantly different from those exhibited by normal controls; however, decreased expression was observed in atrophic neurons (43). These reports have been confirmed by others looking at expression profile of several genes in ALS (64). Conversely, others have suggested that SOD1 expression might be higher in ALS patients (11, 19). This duplicity regarding SOD1 expression in ALS is confusing, and it is mostly likely confounded by the complex pathology of the disease, or attributable to disease-associated mutations in SOD1. Recently, a 50 bp deletion in the SOD1 promoter was identified in individuals with sporadic ALS of Italian decent. However, these changes were shown to have no effect on SOD1 transcription (39). Epigenetic repression is another possibility leading to altered gene expression. While this mechanism has not been completely explored, SOD1 is probably not a target for epigenetic silencing by cytosine methylation in ALS (44). Decreasing the expression of SOD1 has also been explored as a therapeutic avenue to reduce SOD1 expression in ALS. Compounds that inhibit SOD1 transcription in model cell lines have been identified, and may serve as the basis for developing clinically viable strategies for ALS aimed at decreasing SOD1 expression (66).

CuZnSOD Protein

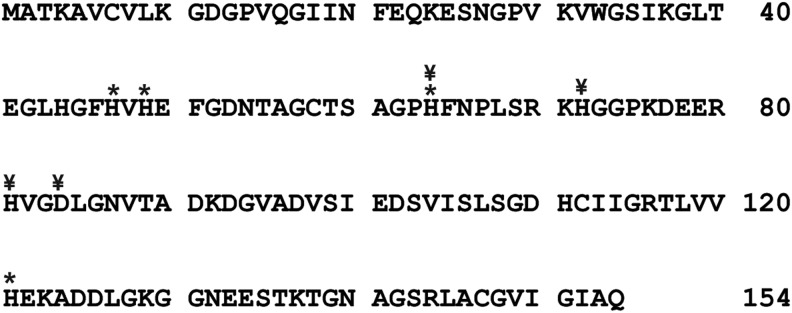

Manufacturing a functional CuZnSOD dimer requires a process that includes several concerted steps: disulfide bond formation, protein folding, metal ion loading, and dimer formation. Each monomer is 153 amino acids, and it weighs ∼19 kDa. An SOD1 homodimer consists of two catalytically active nondisulfide linked subunits; however, creating and maintaining the structure of each monomer utilizes intramolecular disulfides (5). Fully formed monomers contain a disulfide bond between Cys 57 and Cys 146, but may use other cysteines to obtain proper folding (9, 67). Loss of the disulfide bridge results in a catalytically dead version of CuZnSOD.

The loading of Cu(II) and Zn(II) ions is another critical step in forming active SOD1. Both metals are coordinated in the active site of the enzyme by several histidine residues. In humans, the active site metal ions are held in place by His46, 48, 60, 63, 71, and 120 (Fig. 3). The layout and structure of the SOD1 active site is distinct from the other mammalian SODs, MnSOD, and EcSOD (41). The nature of active site most likely bestows SOD1 with unique activities unobserved in the other SODs. The addition of copper to SOD1 is assisted by the protein copper chaperone for SOD1 (CCS). CCS contains unique structural motifs that create a binding site to stabilize the structure of a nascent SOD1 monomer to facilitate the integration of copper into the enzyme (17, 20). Interactions with CCS facilitate SOD1 folding, metal ion chelation, and disulfide formation to create an active protein (28). This mechanism is reliant on a stable structure of CCS, which is oxidatively sensitive (20).

FIG. 3.

Primary amino-acid sequence of the product of the human SOD1 gene, the human CuZnSOD protein. Asterisks mark histidine amino-acid residues that are responsible for chelating the Cu and Zn ions in the holoenzyme. ¥ mark the amino-acid residues that are commonly mutated in familial ALS. ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

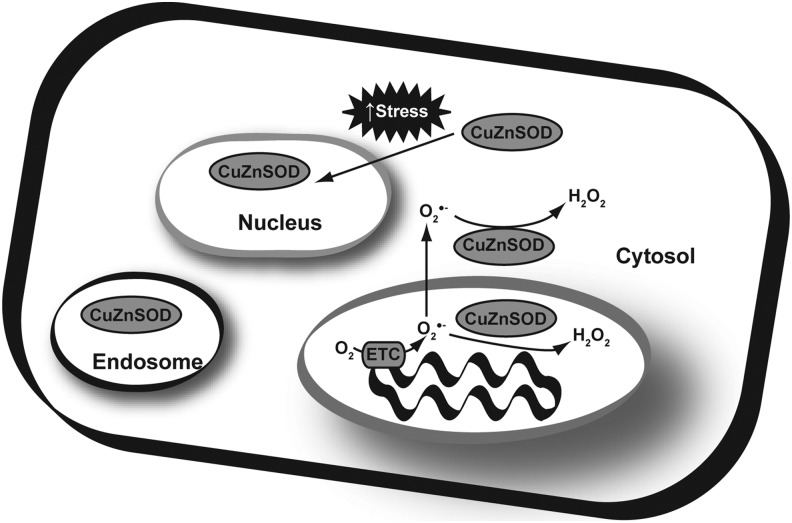

SOD1 processing may also be involved in directing its subcellular localization. SOD1 is most abundant in the cytosol; however, it has also been observed in endosomes, and the mitochondrial intermembrane space (24, 52) (Fig. 4). During mitochondrial import, SOD1 is imported as an immature, catalytically inactive form into the intermembrane space. Once there, it is processed by CCS into the active form, becoming trapped in the mitochondria (24, 30). This mechanism allows SOD1 to be targeted to the intermembrane space even without a canonical mitochondrial targeting sequence. Stress signals may also influence the subcellular localization of SOD1. Increased stress can trigger events that lead to the import of SOD1 from the cytoplasm and into the nucleus (73).

FIG. 4.

Sub-cellular localization of CuZnSOD protein. Typically considered a cytosolic protein, evidence indicates that approximately 10% of CuZnSOD resides in the mitochondrial intermembrane space with the presumptive function of scavenging superoxide leaked from the back side of the coenzyme Q cycle in complex III of the electron transport chain. In addition, under conditions of significant oxidative stress, CuZnSOD can re-localize to the nucleus of cells. Although its function in the nucleus is less clear, it may re-localize there to maintain nuclear redox buffering capacity and keep nuclear Zn finger transcription factors and other DNA binding proteins in a properly reduced state for optimal responses to oxidant stress.

SOD1 Catalytic Mechanism and ALS

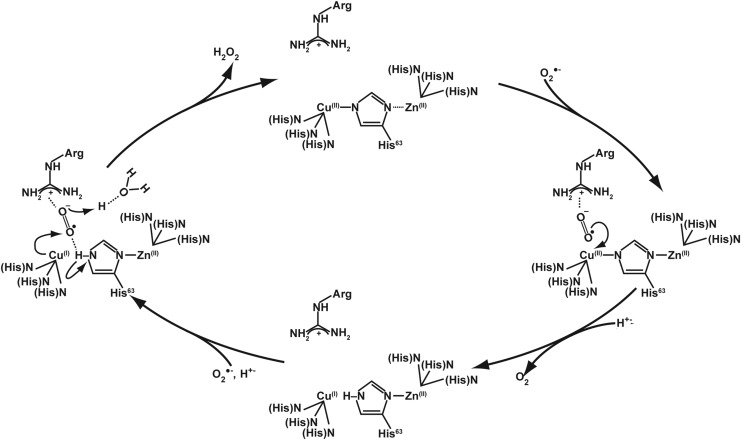

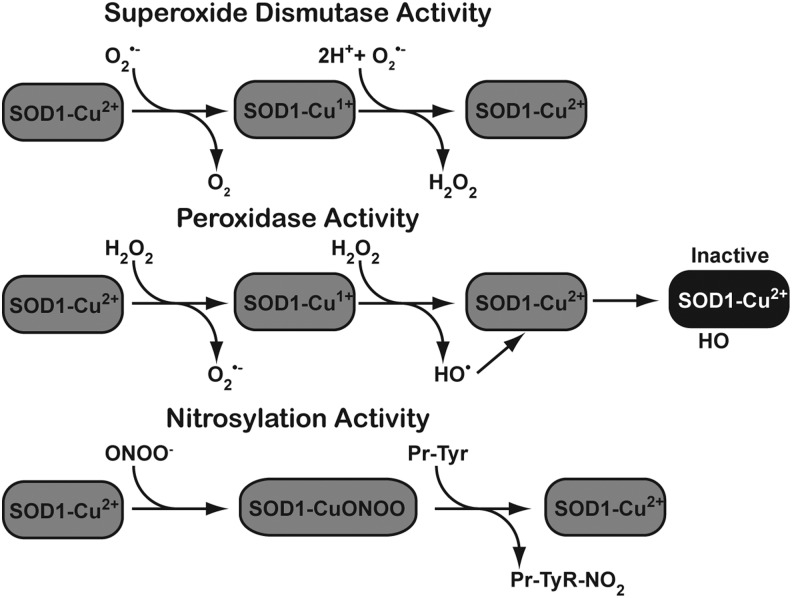

Similar to other mammalian SODs, SOD1 utilizes a ping-pong mechanism that requires two successive loadings of O2•−. The step-by-step mechanism for human SOD1 is shown in Figure 5. In this mechanism, the metals in the catalytic core of SOD1 withdraw an electron from the first superoxide, then mask the negative charge by redistributing it, which favors the attraction of a second O2•− molecule. SOD1 also exhibits a low level of intrinsic peroxidase activity. This activity of SOD1 is unique among mammalian SODs (Fig. 6). Specific conditions appear to favor this activity, such as H2O2 and superoxide concentration.

FIG. 5.

Enzymatic mechanism for the activity of CuZnSOD. The enzyme works through a so-called ping pong mechanism in which the first reacting superoxide reduces the holoenzyme Cu at the active site, depositing an electron and leaving as molecular oxygen. The second reacting superoxide then accepts an electron from the reduced Cu to become hydrogen peroxide (HOOH) and leaving the Cu oxidized and ready to accept another electron, thus completing the cycle.

FIG. 6.

Several reactions can be catalyzed by CuZnSOD. In addition to the canonical SOD reaction (top panel), CuZnSOD also has a peroxidase activity (middle panel) as well as a nitrosylation activity (bottom panel).

SOD1 Mutations Influence Its Activity in ALS

The association between SOD1 mutations that affect enzyme activity and ALS has garnered much attention beginning with the initial report of Rosen et al. describing the linkage between the two (51). Thus far, SOD1 mutations associated with ALS have been identified in the promoter, untranslated regions, exons, and introns. To date, ∼150 mutations scattered across the coding region of SOD1 have been identified as associated with ALS. In North America, the most abundant mutation is the A4V mutant. This mutation is associated with aggressive forms of familial ALS, with a median survival time of 1.2 year compared with other mutations with a survival of 2.5 year after onset (50). Other familial mutations such as H46R and G93 present a less severe phenotype and exhibit longer survival times after disease onset (58).

The identification of ALS-associated mutations in familial cases has ushered in the development of mouse genetic models that attempt to emulate the ALS phenotype. Several SOD1 mutant transgenic mouse models corresponding to human mutations have been created and characterized in an attempt to gain insights into the etiology of ALS, the principal of which are A4V, H46R, H48Q, and G93A (23, 46). These enzymes vary in the amount of SOD activity they exhibit in vitro. Some forms display no detectable SOD activity, while others appear to process superoxide that is similar to wild-type CuZnSOD. Furthermore, unlike these transgenic lines, SOD1 knockout mice do not develop an ALS phenotype (56). This suggests that mutant forms of SOD1 exhibit a gain of function that is responsible for the manifestation of the ALS phenotype. Both the expression level of mutant SOD1 and the genetic background of mice transgenic cell lines appear to influence the severity of disease and the time at which ALS symptoms are exhibited (12, 55). Even with this caveat, a great deal has been learned about ALS disease pathology. Some of the mutations, such as the aggregation mutation AV4, do not create the ALS phenotype in transgenic systems, even though protein aggregation is present (16). Several elegant in vitro and in vivo studies using these genetic models have rendered some insights into the various mechanisms by which mutant SOD1 may be responsible for ALS. The power of these model systems has allowed investigators to determine whether a broad spectrum of items may influence ALS symptoms, including diet, overexpression of other neuronal proteins, altered signaling cascades, and antioxidant status (7, 29, 31, 42).

Several groups have suggested that increased peroxidase activity in the SOD1 mutants may be responsible for creating the ALS phenotype (6). As mentioned earlier, mutant forms of SOD1 vary in their relative amounts of SOD activity. Apart from their normal SOD activity, some SOD1 mutant gain-of-function variants have an increased propensity to utilize their peroxidase activity (Fig. 6). Indeed, the aggressive A4V mutant shows the highest affinity for H2O2 and increased ability to produce H2O2. Increased peroxidase activity is observed in mouse models that are synonymous with the human AV4, H48Q, and G93A mutations (34, 49). The outcomes from this activity are manifold. In some cases, peroxidase activity can generate superoxide from H2O2, and a hydroxyl radical that modifies the imidazole ring of histidine, which irreversibly inactivates the enzyme (33, 34). If cellular conditions favor it, H2O2 can react with carbonate to form peroxymonocarbonate, which can also be processed by the enzyme to create the carbonate radical (4, 37, 70).

Another unique mechanism exists by which SOD1 processes ONOO−, leading to the nitration of tyrosine residues in several key cellular proteins (2, 21). In ALS, increased tyrosine nitration has been detected in familial and sporadic cases alike, suggesting that tyrosine nitration might play a role in the etiology of the disease (59). Tyrosine nitration of proteins in motor neurons, such as neurofilament light chain, alters their structure and function, which ultimately leads to death of the motor neuron (15). Wild-type- and ALS-associated mutant forms of SOD1 are capable of nitration activity; however, some evidence suggests that metal chelation mutants lacking zinc create profound increases in tyrosine nitration (14, 18). However, not all ALS-associated mutations exhibit increased levels of the aberrant activities, suggesting that their role may lie beyond the free radicals or ROS they discharge into the cellular milieu.

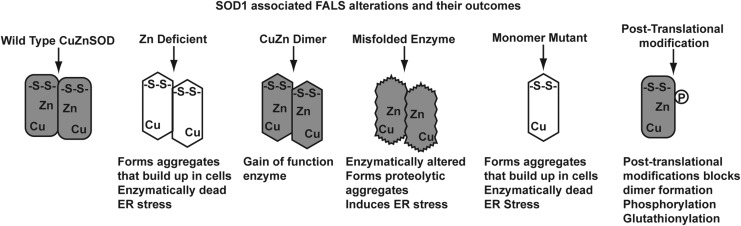

Another clue to the role that mutant SOD1 might play in ALS is exhibited by enzymes that gain functions other than peroxidase activity. Defects in protein folding, processing, and three-dimensional structure may contribute to the ALS phenotype. Displaced or ill-coordinated metal ions within an SOD1 monomer are a common theme in ALS-associated mutations. Disrupting the histidines that coordinate Zn+2 ion can alter enzyme function and its redox state (35). SOD1 mutations can impair the processing of the enzyme, which gives rise to the other possibilities outlined in Figure 7. Enzymes deficient in copper, zinc, or intra-monomer disulfides can lead to protein aggregation and have been associated with ALS. Similarly, defective CCS may create a comparable response. In this scenario, the mis-folded or metal ion-deficient monomers form insoluble protein inclusion bodies. These mis-folded proteins can be created by a plethora of SOD1 mutants. Most notable among these mutants are Cys 57 and 146; however, mutations in surrounding amino acids can have a similar outcome. Recently, whole exome sequencing has identified mutations at these codons (67).

FIG. 7.

Several possible molecular mechanisms mediating mutant CuZnSOD cellular toxicity in familial ALS. There are many different and distinct mutations associated with this disease, which suggests that multiple mechanisms of toxicity are possible.

Mutations that result in altered zinc coordination can also lead to mis-folded proteins and end up creating SOD1 aggregates. Likewise, mis-coordination of Cu+2 can also influence protein-folding activity, and lead to the formation of aggregates (45). In the case of copper, aggregates can be formed by dysfunction with CCS, or by mutating amino acids that are responsible for copper binding in SOD1. These immature forms of SOD1 can have far-reaching effects in cells. If CCS is dysfunctional in the mitochondria, mis-folded proteins can accumulate here, and create mitochondrial stress (13). ALS-associated mutations in SOD1 can alter the interaction between CCS and immature monomer (26, 53).

Disrupting the disulfide bridges of SOD1 is the most common mechanism leading to protein aggregation in ALS, and numerous studies have established alterations in disulfide formation as important in the pathology of ALS. Numerous ALS-associated SOD1 mutants exhibit altered biophysical properties that are traceable to disrupted disulfide linkages (25). Disulfides may also be responsible for the formation of SOD1 aggregates. Using cell free assays, Wang and colleagues demonstrated that intermolecular disulfides could form between SOD1 monomers (62). Here again, a role for CCS may exist in the pathology of ALS. CCS interacts with immature SOD1 monomers via disulfide bridges. If these cysteines are reduced, the two proteins cannot interact (8). SOD1 is also a target for post-translational modification by glutathionylation at phosphorylation. The addition of these modifications may disrupt the structure of SOD1, and lead to protein instability (65).

SOD1's Role in ALS Pathology

Elucidating a linkage between SOD1 and ALS has been a relatively straightforward process, while understanding the nature of this relationship has proved more difficult. Alterations of SOD1 may influence the development of ALS in several ways. Mis-folded and incomplete processed CuZnSOD proteins may serve as cellular cues. The accumulation of unfolded proteins in aggregates initializes endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress signaling pathways. Exacerbating the unfolded protein response hastens ALS progression (63). Others have suggested that chronic activation of ER stress by mis-folded SOD1 can possibly lead to cell death in ALS, and cite that mutations in proteins involved in stress signaling can also cause the disease (61).

SOD1 Mutations May Influence Redox Signaling in ALS

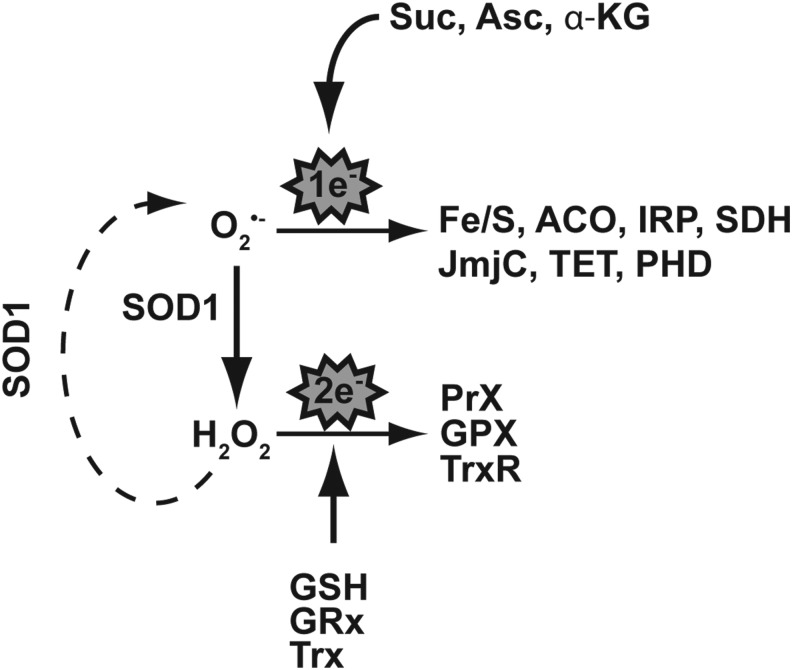

Another way in which altered SOD1 may be causal in the development of ALS is by disrupting redox signaling pathways. If we conceptualize superoxide as a signaling molecule rather than just a reactive species, we can construct a signal transduction pathway in which superoxide influences one electron signaling through compounds such as glutathione (Fig. 8). The conversion of superoxide to H2O2 by SOD1 creates new possibilities for signaling. Here, classic paradigms of cell stress such as peroxiredoxin and thioredoxin can be activated, and influenced, by the steady-state levels of reactive oxygen and exert an influence on a cell's phenotype by altering gene expression (22). How might this influence ALS? Cells harboring a wild-type SOD1 maintain a balance of different reactive oxygen species that is consistent with fully functional signaling pathways. McCord and Fridovich aptly demonstrated that changes in SOD1 alter superoxide levels (36). Likewise, others have described the altered level of superoxide in cells harboring mutated SOD1 (72). We speculate that ALS-associated changes in SOD1 would upset a cell's reactive oxygen species balance by altering the steady-state level of superoxide. In turn, this would alter the aforementioned pathways and serve as one avenue to create the phenotype of ALS. This scenario can be created by alterations in SOD1 expression, or the creation of dysfunctional enzyme complexes with incomplete or unique activities (33, 41). Furthermore, “gain-of-function” SOD1 mutants with identical dismutase activity may harbor altered peroxidase activity compared with wild-type counterparts. This would create another means to modify the redox status of the cellular milieu (68, 69). Both mechanisms would impact cellular function by manipulating cell signaling, and put SOD1 as a central player on a signal transduction stage.

FIG. 8.

CuZnSOD resides at a critical junction between one-electron and two-electron signaling pathways that elicit different cellular response programs. One-electron-sensitive labile iron pools reside in proteins such as Fe/S cluster proteins, including ACO, “cytosolic aconitase” or IRP, and SDH, and in other non-heme iron-containing enzymes such as those in the JmjC and TET family. Two-electron signaling pathways mediated via SOD1's product H2O2 include thioredoxin, glutaredoxin, and the peroxiredoxins along with their respective cofactors. Fe/S, iron–sulfur; ACO, aconitase; IRP, iron-response protein; SDH, succinate dehydrogenase.

Could perturbations in the flux of superoxide and H2O2 have a role in ALS? To date, the underpinnings of free radical flux on cell signaling are not yet fully defined and may serve as an avenue to pursue the role of SOD1 in the etiology of ALS. Studies related to hypoxia have shown that altering free radical flux influences signal transduction pathways that are reliant on H2O2 in brains of developing animals (3). Likewise, the ER stress mechanism mentioned earlier may influence this signaling in a similar manner, inducing neuronal apoptosis (71). Studies aimed at investigating the effect that altered free radical flux in ALS has on paradigms of signal transduction may further support a linkage between SOD1 and this disease.

Conclusions

CuZnSOD plays a central role not only in detoxifying damaging superoxide in the cytosol and mitochondrial intermembrane space, but also by acting as a transistor to convert one electron signaling to two electron signaling. Too much or too little CuZnSOD activity can lead to aberrant cellular signaling and maintenance of homeostasis around a nonequilibrium steady state. In addition, mutant forms of CuZnSOD with potentially altered signaling properties have emerged as candidate disease genes in humans. This is particularly true in the case of familial ALS, but a deep understanding of the enigmatic connection between SOD1 and ALS remains obscure. The central question is: By what mechanism does SOD1's gain-of-function mutations influence the manifestation of the ALS phenotype? Fundamental discoveries suggest that H2O2, superoxide, protein processing, and aberrant enzyme activities might be strings connecting SOD1 with ALS. Perhaps ALS could be a disease with a free radical pathology that is supported by an undercarriage of aberrant cell signaling.

Abbreviations Used

- ACO

aconitase

- AHR

aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- AP-1

activator protein 1

- ARNT

aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator

- C/EBP

CAATT enhancer binding proteins

- CCS

copper chaperone for SOD1

- CuZnSOD

copper zinc superoxide dismutase

- Cys

cysteine

- ECSOD

extracellular superoxide dismutase

- EGR-1

early growth response 1

- ENCODE

encyclopedia of DNA elements

- Fe/S

iron–sulfur cluster

- H3K36me3

histone H3 Lysine 36 tri-methyl

- H3K4me2

histone H3 Lysine 4 di-methyl

- H3K4me3

histone H3 Lysine 4 tri-methyl

- H3K9ac

histone H3 Lysine 9 acetylated

- His

histidine

- IRP

iron-response protein

- MnSOD

manganese superoxide dismutase

- NFkB

nuclear factor kappa B

- NRF2

nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2

- ONOO

peroxynitrite

- SDH

succinate dehydrogenase

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- SOD1

superoxide dismutase 1

- SP-1

specificity protein 1

References

- 1.Andersen PM. and Al-Chalabi A. Clinical genetics of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: what do we really know? Nat Rev Neurol 7: 603–615, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beckman JS, Ischiropoulos H, Zhu L, van der Woerd M, Smith C, Chen J, Harrison J, Martin JC, and Tsai M. Kinetics of superoxide dismutase- and iron-catalyzed nitration of phenolics by peroxynitrite. Arch Biochem Biophys 298: 438–445, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bendix I, Weichelt U, Strasser K, Serdar M, Endesfelder S, von Haefen C, Heumann R, Ehrkamp A, Felderhoff-Mueser U, and Sifringer M. Hyperoxia changes the balance of the thioredoxin/peroxiredoxin system in the neonatal rat brain. Brain Res 1484: 68–75, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonini MG, Gabel SA, Ranguelova K, Stadler K, Derose EF, London RE, and Mason RP. Direct magnetic resonance evidence for peroxymonocarbonate involvement in the cu,zn-superoxide dismutase peroxidase catalytic cycle. J Biol Chem 284: 14618–14627, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouldin SD, Darch MA, Hart PJ, and Outten CE. Redox properties of the disulfide bond of human Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase and the effects of human glutaredoxin 1. Biochem J 446: 59–67, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bredesen DE, Wiedau-Pazos M, Goto JJ, Rabizadeh S, Roe JA, Gralla EB, Ellerby LM, and Valentine JS. Cell death mechanisms in ALS. Neurology 47: S36-8; discussion S38–S39, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlson GA, Borchelt DR, Dake A, Turner S, Danielson V, Coffin JD, Eckman C, Meiners J, Nilsen SP, Younkin SG, and Hsiao KK. Genetic modification of the phenotypes produced by amyloid precursor protein overexpression in transgenic mice. Hum Mol Genet 6: 1951–1959, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carroll MC, Outten CE, Proescher JB, Rosenfeld L, Watson WH, Whitson LJ, Hart PJ, Jensen LT, and Cizewski Culotta V. The effects of glutaredoxin and copper activation pathways on the disulfide and stability of Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase. J Biol Chem 281: 28648–28656, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen X, Shang H, Qiu X, Fujiwara N, Cui L, Li XM, Gao TM, and Kong J. Oxidative modification of cysteine 111 promotes disulfide bond-independent aggregation of SOD1. Neurochem Res 37: 835–845, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Commoner B, Townsend J, and Pake GE. Free radicals in biological materials. Nature 174: 689–691, 1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conforti FL, Magariello A, Mazzei R, Sprovieri T, Patitucci A, Crescibene L, Bastone L, Gabriele A, Scornaienchi M, Ferraro T, Muglia M, and Quattrone A. Abnormally high levels of SOD1 mRNA in a patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 29: 610–611, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Couillard-Despres S, Zhu Q, Wong PC, Price DL, Cleveland DW, and Julien JP. Protective effect of neurofilament heavy gene overexpression in motor neuron disease induced by mutant superoxide dismutase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95: 9626–9630, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cozzolino M, Pesaresi MG, Amori I, Crosio C, Ferri A, Nencini M, and Carri MT. Oligomerization of mutant SOD1 in mitochondria of motoneuronal cells drives mitochondrial damage and cell toxicity. Antioxid Redox Signal 11: 1547–1558, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crow JP, Sampson JB, Zhuang Y, Thompson JA, and Beckman JS. Decreased zinc affinity of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated superoxide dismutase mutants leads to enhanced catalysis of tyrosine nitration by peroxynitrite. J Neurochem 69: 1936–1944, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crow JP, Ye YZ, Strong M, Kirk M, Barnes S, and Beckman JS. Superoxide dismutase catalyzes nitration of tyrosines by peroxynitrite in the rod and head domains of neurofilament-L. J Neurochem 69: 1945–1953, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deng HX, Shi Y, Furukawa Y, Zhai H, Fu R, Liu E, Gorrie GH, Khan MS, Hung WY, Bigio EH, Lukas T, Dal Canto MC, O'Halloran TV, and Siddique T. Conversion to the amyotrophic lateral sclerosis phenotype is associated with intermolecular linked insoluble aggregates of SOD1 in mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 7142–7147, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Falconi M, Iovino M, and Desideri A. A model for the incorporation of metal from the copper chaperone CCS into Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase. Structure 7: 903–908, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrante RJ, Shinobu LA, Schulz JB, Matthews RT, Thomas CE, Kowall NW, Gurney ME, and Beal MF. Increased 3-nitrotyrosine and oxidative damage in mice with a human copper/zinc superoxide dismutase mutation. Ann Neurol 42: 326–334, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gagliardi S, Cova E, Davin A, Guareschi S, Abel K, Alvisi E, Laforenza U, Ghidoni R, Cashman JR, Ceroni M, and Cereda C. SOD1 mRNA expression in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol Dis 39: 198–203, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gross DP, Burgard CA, Reddehase S, Leitch JM, Culotta VC, and Hell K. Mitochondrial Ccs1 contains a structural disulfide bond crucial for the import of this unconventional substrate by the disulfide relay system. Mol Biol Cell 22: 3758–3767, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ischiropoulos H, Zhu L, Chen J, Tsai M, Martin JC, Smith CD, and Beckman JS. Peroxynitrite-mediated tyrosine nitration catalyzed by superoxide dismutase. Arch Biochem Biophys 298: 431–437, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jarvis RM, Hughes SM, and Ledgerwood EC. Peroxiredoxin 1 functions as a signal peroxidase to receive, transduce, and transmit peroxide signals in mammalian cells. Free Radic Biol Med 53: 1522–1530, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Julien JP. and Kriz J. Transgenic mouse models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1762: 1013–1024, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawamata H. and Manfredi G. Import, maturation, and function of SOD1 and its copper chaperone CCS in the mitochondrial intermembrane space. Antioxid Redox Signal 13: 1375–1384, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kayatekin C, Zitzewitz JA, and Matthews CR. Disulfide-reduced ALS variants of Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase exhibit increased populations of unfolded species. J Mol Biol 398: 320–331, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim HK, Chung YW, Chock PB, and Yim MB. Effect of CCS on the accumulation of FALS SOD1 mutant-containing aggregates and on mitochondrial translocation of SOD1 mutants: implication of a free radical hypothesis. Arch Biochem Biophys 509: 177–185, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim HT, Kim YH, Nam JW, Lee HJ, Rho HM, and Jung G. Study of 5'-flanking region of human Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 201: 1526–1533, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lamb AL, Torres AS, O'Halloran TV, and Rosenzweig AC. Heterodimeric structure of superoxide dismutase in complex with its metallochaperone. Nat Struct Biol 8: 751–755, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee J, Ryu H, and Kowall NW. Motor neuronal protection by L-arginine prolongs survival of mutant SOD1 (G93A) ALS mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 384: 524–529, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leitch JM, Yick PJ, and Culotta VC. The right to choose: multiple pathways for activating copper,zinc superoxide dismutase. J Biol Chem 284: 24679–24683, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lerman BJ, Hoffman EP, Sutherland ML, Bouri K, Hsu DK, Liu FT, Rothstein JD, and Knoblach SM. Deletion of galectin-3 exacerbates microglial activation and accelerates disease progression and demise in a SOD1(G93A) mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain Behav 2: 563–575, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Q, Spencer NY, Oakley FD, Buettner GR, and Engelhardt JF. Endosomal Nox2 facilitates redox-dependent induction of NF-kappaB by TNF-alpha. Antioxid Redox Signal 11: 1249–1263, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liochev SI, Chen LL, Hallewell RA, and Fridovich I. Superoxide-dependent peroxidase activity of H48Q: a superoxide dismutase variant associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Biochem Biophys 346: 263–268, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liochev SI, Chen LL, Hallewell RA, and Fridovich I. The familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated amino acid substitutions E100G, G93A, and G93R do not influence the rate of inactivation of copper- and zinc-containing superoxide dismutase by H2O2. Arch Biochem Biophys 352: 237–239, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lyons TJ, Liu H, Goto JJ, Nersissian A, Roe JA, Graden JA, Cafe C, Ellerby LM, Bredesen DE, Gralla EB, and Valentine JS. Mutations in copper-zinc superoxide dismutase that cause amyotrophic lateral sclerosis alter the zinc binding site and the redox behavior of the protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93: 12240–12244, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCord JM. and Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutase. An enzymic function for erythrocuprein (hemocuprein). J Biol Chem 244: 6049–6055, 1969 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Medinas DB, Toledo JC, Jr, Cerchiaro G, do-Amaral AT, de-Rezende L, Malvezzi A, and Augusto O. Peroxymonocarbonate and carbonate radical displace the hydroxyl-like oxidant in the Sod1 peroxidase activity under physiological conditions. Chem Res Toxicol 22: 639–648, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miao L. and St. Clair DK. Regulation of superoxide dismutase genes: implications in disease. Free Radic Biol Med 47: 344–356, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Milani P, Gagliardi S, Bongioanni P, Grieco GS, Dezza M, Bianchi M, Cova E, Ceroni M, and Cereda C. Effect of the 50 bp deletion polymorphism in the SOD1 promoter on SOD1 mRNA levels in Italian ALS patients. J Neurol Sci 313: 75–78, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Milani P, Gagliardi S, Cova E, and Cereda C. SOD1 Transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation and its potential implications in ALS. Neurol Res Int 2011: 458427, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller AF. Superoxide dismutases: active sites that save, but a protein that kills. Curr Opin Chem Biol 8: 162–168, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nagano S, Ogawa Y, Yanagihara T, and Sakoda S. Benefit of a combined treatment with trientine and ascorbate in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis model mice. Neurosci Lett 265: 159–162, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nishiyama K, Murayama S, Kwak S, and Kanazawa I. Expression of the copper-zinc superoxide dismutase gene in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol 41: 551–556, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oates N. and Pamphlett R. An epigenetic analysis of SOD1 and VEGF in ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 8: 83–86, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oztug Durer ZA, Cohlberg JA, Dinh P, Padua S, Ehrenclou K, Downes S, Tan JK, Nakano Y, Bowman CJ, Hoskins JL, Kwon C, Mason AZ, Rodriguez JA, Doucette PA, Shaw BF, and Selverstone Valentine J. Loss of metal ions, disulfide reduction and mutations related to familial ALS promote formation of amyloid-like aggregates from superoxide dismutase. PLoS One 4: e5004, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pan L, Yoshii Y, Otomo A, Ogawa H, Iwasaki Y, Shang HF, and Hadano S. Different human copper-zinc superoxide dismutase mutants, SOD1G93A and SOD1H46R, exert distinct harmful effects on gross phenotype in mice. PLoS One 7: e33409, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park EY. and Rho HM. The transcriptional activation of the human copper/zinc superoxide dismutase gene by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin through two different regulator sites, the antioxidant responsive element and xenobiotic responsive element. Mol Cell Biochem 240: 47–55, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pekowska A, Benoukraf T, Zacarias-Cabeza J, Belhocine M, Koch F, Holota H, Imbert J, Andrau JC, Ferrier P, and Spicuglia S. H3K4 tri-methylation provides an epigenetic signature of active enhancers. EMBO J 30: 4198–4210, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roe JA, Wiedau-Pazos M, Moy VN, Goto JJ, Gralla EB, and Valentine JS. In vivo peroxidative activity of FALS-mutant human CuZnSODs expressed in yeast. Free Radic Biol Med 32: 169–174, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosen DR, Bowling AC, Patterson D, Usdin TB, Sapp P, Mezey E, McKenna-Yasek D, O'Regan J, Rahmani Z, Ferrante RJ, et al. A frequent ala 4 to val superoxide dismutase-1 mutation is associated with a rapidly progressive familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet 3: 981–987, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosen DR, Siddique T, Patterson D, Figlewicz DA, Sapp P, Hentati A, Donaldson D, Goto J, O'Regan JP, Deng HX, et al. Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature 362: 59–62, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saito T, Shinzawa H, Togashi H, Wakabayashi H, Ukai K, Takahashi T, Ishikawa M, Dobashi M, and Imai Y. Ultrastructural localization of Cu, Zn-SOD in hepatocytes of patients with various liver diseases. Histol Histopathol 4: 1–6, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seetharaman SV, Prudencio M, Karch C, Holloway SP, Borchelt DR, and Hart PJ. Immature copper-zinc superoxide dismutase and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 234: 1140–1154, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seila AC, Calabrese JM, Levine SS, Yeo GW, Rahl PB, Flynn RA, Young RA, and Sharp PA. Divergent transcription from active promoters. Science 322: 1849–1851, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shaw BF, Lelie HL, Durazo A, Nersissian AM, Xu G, Chan PK, Gralla EB, Tiwari A, Hayward LJ, Borchelt DR, Valentine JS, and Whitelegge JP. Detergent-insoluble aggregates associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in transgenic mice contain primarily full-length, unmodified superoxide dismutase-1. J Biol Chem 283: 8340–8350, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shefner JM, Reaume AG, Flood DG, Scott RW, Kowall NW, Ferrante RJ, Siwek DF, Upton-Rice M, and Brown RH., Jr.Mice lacking cytosolic copper/zinc superoxide dismutase display a distinctive motor axonopathy. Neurology 53: 1239–1246, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spicuglia S. and Vanhille L. Chromatin signatures of active enhancers. Nucleus 3: 126–131, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ticozzi N, Tiloca C, Morelli C, Colombrita C, Poletti B, Doretti A, Maderna L, Messina S, Ratti A, and Silani V. Genetics of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Ital Biol 149: 65–82, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tohgi H, Abe T, Yamazaki K, Murata T, Ishizaki E, and Isobe C. Remarkable increase in cerebrospinal fluid 3-nitrotyrosine in patients with sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol 46: 129–131, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wagner EJ. and Carpenter PB. Understanding the language of Lys36 methylation at histone H3. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13: 115–126, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Walker AK. and Atkin JD. Stress signaling from the endoplasmic reticulum: a central player in the pathogenesis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. IUBMB Life 63: 754–763, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang J, Xu G, and Borchelt DR. Mapping superoxide dismutase 1 domains of non-native interaction: roles of intra- and intermolecular disulfide bonding in aggregation. J Neurochem 96: 1277–1288, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang L, Popko B, and Roos RP. The unfolded protein response in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet 20: 1008–1015, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang XS, Simmons Z, Liu W, Boyer PJ, and Connor JR. Differential expression of genes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis revealed by profiling the post mortem cortex. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 7: 201–210, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wilcox KC, Zhou L, Jordon JK, Huang Y, Yu Y, Redler RL, Chen X, Caplow M, and Dokholyan NV. Modifications of superoxide dismutase (SOD1) in human erythrocytes: a possible role in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Biol Chem 284: 13940–13947, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wright PD, Wightman N, Huang M, Weiss A, Sapp PC, Cuny GD, Ivinson AJ, Glicksman MA, Ferrante RJ, Matson W, Matson S, and Brown RH., Jr.A high-throughput screen to identify inhibitors of SOD1 transcription. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 4: 2801–2808, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu J, Shen E, Shi D, Sun Z, and Cai T. Identification of a novel Cys146X mutation of SOD1 in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis by whole-exome sequencing. Genet Med 14: 823–826, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yim HS, Kang JH, Chock PB, Stadtman ER, and Yim MB. A familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated A4V Cu, Zn-superoxide dismutase mutant has a lower Km for hydrogen peroxide. Correlation between clinical severity and the Km value. J Biol Chem 272: 8861–8863, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yim MB, Yim HS, Chock PB, and Stadtman ER. Enhanced free radical generation of FALS-associated Cu,Zn-SOD mutants. Neurotox Res 1: 91–97, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang H, Andrekopoulos C, Joseph J, Crow J, and Kalyanaraman B. The carbonate radical anion-induced covalent aggregation of human copper, zinc superoxide dismutase, and alpha-synuclein: intermediacy of tryptophan- and tyrosine-derived oxidation products. Free Radic Biol Med 36: 1355–1365, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang Y, Liu W, Ma C, Geng J, Li Y, Li S, Yu F, Zhang X, and Cong B. Endoplasmic reticulum stress contributes to CRH-induced hippocampal neuron apoptosis. Exp Cell Res 318: 732–740, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zimmerman MC, Oberley LW, and Flanagan SW. Mutant SOD1-induced neuronal toxicity is mediated by increased mitochondrial superoxide levels. J Neurochem 102: 609–618, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zlatkovic J. and Filipovic D. Stress-induced alternations in CuZnSOD and MnSOD activity in cellular compartments of rat liver. Mol Cell Biochem 357: 143–150, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]