Abstract

About 20% of patients hospitalized for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbations are readmitted within 30 days. High 30-day risk-standardized readmission rates after COPD exacerbations will likely place hospitals at risk for financial penalties from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services starting in fiscal year 2015. Factors contributing to hospital readmissions include healthcare quality, access to care, coordination of care between hospital and ambulatory settings, and factors linked to socioeconomic resources (e.g., social support, stable housing, transportation, and food). These concerns are exacerbated at minority-serving institutions, which provide a disproportionate share of care to patients with low socioeconomic resources. Solutions tailored to the needs of minority-serving institutions are urgently needed. We recommend research that will provide the evidence base for strategies to reduce readmissions at minority-serving institutions. Promising innovative approaches include using a nontraditional healthcare workforce, such as community health workers and peer-coaches, and telemedicine. These strategies have been successfully used in other conditions and need to be studied in patients with COPD.

Keywords: COPD, hospital readmission, minority health

There are over 800,000 hospital discharges for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) each year in the United States, accounting for nearly $50 billion in healthcare expenditure (1, 2). Gaps in the discharge process have attracted substantial scrutiny in recent years because about one in five Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for COPD exacerbations are readmitted within 30 days, making COPD the third most common reason for readmission (3). In October 2012, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) started imposing financial penalties for hospitals with high readmission rates for heart failure, pneumonia, or myocardial infarction (4). The Affordable Care Act includes provisions that allow CMS to expand the list of conditions for which financial penalties apply (5). In May 2013, CMS invited public comments on a proposal to add hospitalizations for COPD exacerbations to its HRRP, which would in effect trigger financial penalties directed at hospitals if admissions for COPD exacerbations resulted in a higher-than-expected all-cause readmission rate (i.e., including readmissions unrelated to COPD) (6). Initially, these penalties can reach up to 1% of all diagnosis-related group payments but may increase to 2% in fiscal year 2014 and 3% in fiscal year 2015 when COPD will be added as one of the penalty-sensitive conditions (4). Some states, including Massachusetts, Texas, New York, and Illinois, are planning or have already initiated programs among Medicaid beneficiaries modeled on the CMS HRRP to reduce readmissions (7). These penalties will have the greatest impact on nonprofit safety-net hospitals, which have, on average, operating margins of approximately 1%, compared with the national average of about 7% (8, 9). These observations indicate the need for hospitals to develop and implement programs to reduce the risk of readmissions for all patients, including those with COPD exacerbations.

The evidence base supporting the use of case management or other care strategies to reduce rehospitalizations in patients hospitalized for COPD exacerbations is inconsistent (10, 11). Furthermore, most of the studies examining these interventions excluded patients with modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors for readmission, such as language spoken at home, cognitive impairments, lack of caregivers, inadequate access to a telephone, or multiple comorbidities (12, 13). Therefore, the applicability of findings to more heterogeneous clinical populations is unclear.

Thirty-day readmission rates after hospitalizations for pneumonia, myocardial infarction, and heart failure are higher in African Americans compared with white patients and in patients with lower income (14, 15). African Americans hospitalized with COPD exacerbations also have a higher 30-day readmission rate compared with white patients (23.1% vs. 20.5%). Income is also associated with 30-day readmission rates after COPD exacerbations; patients living in areas with a median household income in the lowest quartile have a higher readmission rate compared with patients living in areas with the highest quartile of income (21.5% vs. 20.2%) (16). Institutions serving the highest decile of minority patients (so-called “minority-serving institutions”) have especially high hospital readmission rates. Among Medicare beneficiaries, readmission rates are highest for African Americans at minority-serving institutions (26%) and lowest for whites at non–minority-serving institutions (21%), an excess risk of about 5% (15). These findings suggest that financial penalties for excess hospital readmissions are likely to disproportionately affect minority-serving institutions (17).

Minority-serving Institutions in the Era of Penalties to Reduce Hospital Readmissions

Minority-serving institutions provide a disproportionate share of care to patients with low socioeconomic resources. Factors contributing to hospital readmissions include healthcare quality and access to care, coordination of care between hospital and ambulatory settings (18), and factors linked to socioeconomic resources (e.g., social support, stable housing, transportation, and food) (14). The contribution of limited socioeconomic factors to readmissions is likely to vary by institution and by the patient populations they serve. Anecdotal data indicate that limited socioeconomic resources contribute to readmissions in a high proportion of patients at minority-serving institutions. For example, in a focus group we conducted, a patient recently hospitalized at a minority-serving institution with a COPD exacerbation recounted her experience after being discharged: “I was so stressed going from a cocoon in the hospital to home alone. Stress made breathing more difficult. My medications were outdated and getting proper nutrition was a major issue” (19).

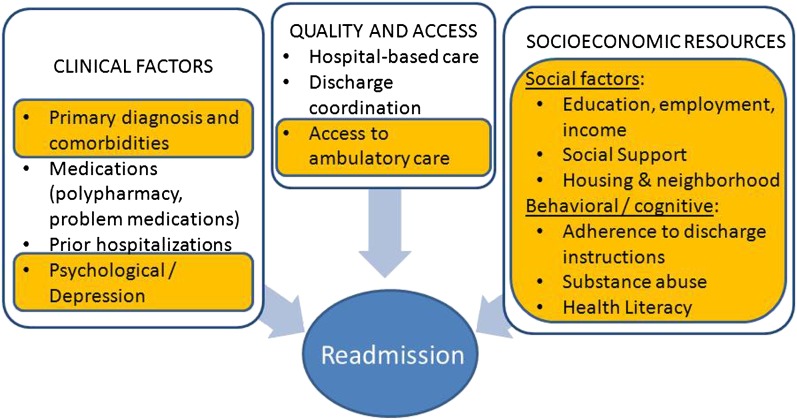

These considerations support an expanded conceptual framework for reducing hospital readmissions that emphasizes the need for interventions directed at improving socioeconomic resources available to patients after discharge (Figure 1) (20). Although hospitals cannot assume responsibility for all patients’ socioeconomic needs, they are well positioned to connect high-risk patients to resources available in the community. These resources, which include prescription medication assistance programs, social services, and help with activities of daily living (e.g., meal preparation), may be offered by state and local governments, nonprofit organizations, or the private sector (21–24). Although such resources may benefit some patients at all hospitals, the need for services is likely to be greater at minority-serving institutions given the populations they serve (25).

Figure 1.

Expanded conceptual framework for factors linked to hospital readmissions emphasizing role of socioeconomic resources. Factors especially challenging to minority-serving institutions are highlighted (20).

Readmission risk prediction models used by CMS to establish benchmarks for comparing hospitals have surprisingly poor performance characteristics (c statistic, 0.60–63) (26). Such models do not adjust for patient-level indicators of SES. This omission is justified by CMS, which state: “Risk-adjusting or stratifying outcomes for patient SES would suggest that hospitals with low SES patients are held to different standards for the risk of readmission than hospitals treating higher SES patient populations. […]CMS does not want to hold hospitals with different SES mixes to different standards” (27).

Thus, the benchmarks used in the CMS HRRP disadvantage institutions serving patients with inadequate socioeconomic resources (17). This concern has been identified as problematic by others who have proposed modifying the methodology used by CMS to calculate risk-standardized readmission rates for hospitals. Inclusion of socioeconomic resource–related factors in developing benchmarks will improve model performance by reducing confounding due to factors unrelated to the quality of hospital-based care (17). The American Hospital Association has recently recommended the inclusion of additional patient characteristics, such as race and limited English proficiency, in the CMS readmission risk-adjustment methodology (28). However, policy changes are difficult to address, and innovative strategies are required to tackle the challenges posed by readmissions at minority-serving institutions.

What Can Be Done to Support Minority-serving Institutions?

One potential approach involves expanding hospital-based care into patient homes and communities using nurses, social workers, physical and respiratory therapists, and other members of the traditional healthcare team. For example, the Care Transitions Intervention and the Transitional Care Model include home visits by advanced practice nurses and postdischarge phone calls (29, 30). The Better Outcomes by Optimizing Safe Transitions (BOOST) and Re-Engineered Discharge (RED) programs include a phone call after discharge to assess adherence and complications (31, 32). However, these practice models do not specify how these interventions address some of the unique needs of patients at minority-serving institutions. For example, BOOST and RED programs tend to have well-developed plans for clinical factors and quality of hospital-based care but are underdeveloped in some of the elements related to socio-economic resources, such as housing, education, and employment.

Deployment of a nontraditional healthcare workforce during the hospital-to-home transition period may be another option. Community health workers (CHWs) are community members who serve as connectors between health care consumers and providers to promote health among groups that have traditionally lacked access to adequate health care (33, 34). CHWs have been supplementing medical care in underserved populations, including low-income minority groups. CHWs can serve as a bridge between people and healthcare systems and help to widely disseminate appropriate healthcare practices. CHWs are uniquely qualified as connectors because they live within the community in which they work (35, 36). A recent systematic review conducted by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality highlighted the benefits of CHWs in promoting cervical cancer screening and use of mammography, in asthma management, and in treatment for mental illnesses (37–39). CHWs may also help to improve hospital-to-home transitions at a lower cost than is possible with traditional healthcare staff (40). There are other community-based approaches to improve health care delivery in vulnerable populations, such as adding clinics in retail pharmacies or expanding the number of community health centers in high-risk neighborhoods (41). In addition to providing informal counseling, social support, and culturally appropriate and accessible health education, the CHWs could be trained to advocate for high-risk individuals (33). HRRPs that include postdischarge CHWs serving as “patient navigators” could complement hospital-based care provided by a traditional healthcare team who would retain their responsibility to address the clinical needs of the patients during these transitions. Studies testing the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a CHW-based patient navigator model during the hospital-to-home transition period in minority-serving institutions to reduce readmissions are needed. Readmission reduction programs would need to be tailored to the needs of patients at each institution. Results obtained at one institution are unlikely to be replicated in other minority-serving institutions given the unique needs at each institution.

Peer coaching (i.e., delivery of an intervention through trained lay-individuals who are affected by the same condition as the patients they coach) has recently gained attention as a cost-effective way to disseminate health information. Based on the social cognitive theory, which focuses on providing the knowledge and skills to promote self-efficacy (i.e., the confidence to carry out the recommended behavior) and positive outcome expectancy (i.e., the belief that the benefits outweigh the harms of the recommended behavior), a recently published pilot clinical trial demonstrated that telephone-based coaching can improve adherence to screening mammography in underserved patient populations (31% women; 89% African American; 11% Hispanic) (42). Likewise, telephone-based coaching appears to be effective in promoting adherence to physical activity recommendations in nonadherent patients after cardiac rehabilitation (43) and in improving self-care and quality of life among patients with heart failure (44). Some patient advocacy groups, such as the COPD Foundation, have started implementing peer-coaching programs, such as peer-led information lines specifically designed to provide education to patients with COPD. This effort has been well received by patients and caregivers (19). Another disease management program, delivered telephonically by trained peers to individuals with a rare cause of COPD (α1-antitrypsin deficiency), has led to improvements in multiple outcomes, including improving adherence to O2 therapy (45). The effectiveness of peer-coaching to reduce readmissions needs to be investigated.

Health information technology may also present another option to reduce readmissions. Low-cost options may include mobile health (mHealth) devices such as smartphones, which can be installed with “apps” to help patients connect with their healthcare providers. mHealth technology can also promote patient self-management through enhanced and on-demand access to educational health materials and access to peer support through social media (46, 47). Health information technology offers the opportunity for interventions that reach patients in their homes and potentially foster greater healthcare access for all patients, although the evidence base regarding the utility of such a strategy has been inconsistent (48, 49). The extent to which these technologies can be useful at minority-serving institutions is yet to be determined because of the lower rates of internet access and smart phone availability.

In summary, the proposed CMS HHRP penalties for COPD readmissions are likely to disproportionately affect minority-serving institutions. In a substantial (though undefined proportion) of cases, readmissions at minority-serving institutions are due to factors linked to patients’ low socioeconomic resources. Promising approaches include using community health workers and peer-coaches, telemedicine, and community-based approaches (e.g., clinics in retail pharmacies). These strategies have been successfully used in other conditions and need to be studied regarding their effectiveness and cost-effectiveness in patients with COPD.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant 2T32HL082547 (V.P.-C.) and by Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute contract IH-12–11–4365 (H.A.G., J.A.K.).

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Morbidity & mortality: 2009 chart book on cardiovascular, lung, and blood diseases [Internet]. [2011; accessed 2013 July12]. Available from: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/about/factbook/chapter4.htm

- 2.Stein BD, Charbeneau JT, Lee TA, Schumock GT, Lindenauer PK, Bautista A, Lauderdale DS, Naureckas ET, Krishnan JA. Hospitalizations for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: how you count matters. COPD. 2010;7:164–171. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2010.481696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CMS.govReadmission reduction program [Internet]. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services;[revised 2013 April 13; accessed 2013 July 14]. Available from: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html

- 5.US CongressHouse Committee on Ways and Means, Committee on Energy and Commerce, Committee on Education and Labor. Compilation of patient protection and affordable care act: as amended through 1 November 2010, including patient protection and affordable care act health-related portions of the health care and education reconciliation act of 2010. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2010. xxiii [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Health and Human ServicesCenters for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Program. Hospital inpatient prospective payment systems for acute care hospitals and the long- term care hospital prospective payment system and proposed fiscal year 2014 rates; quality reporting requirements for specific providers; hospital conditions of participation [Internet]. Washington, DC; National Archives and Records Administration. 78 Federal Register 91 [accessed 2013 July 14]. Available from: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2013–05–10/pdf/2013–10234.pdf [PubMed]

- 7.Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family ServicesPotentially Preventable Readmissions (PPRs) policy and calculations [Internet]. Springfield, IL: Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services [revised 2012 July 31; accessed 2013 July 11]. Available from: http://www2.illinois.gov/hfs/SiteCollectionDocuments/PPRSlides.pdf

- 8.Cunningham PJ, Bazzoli GJ, Katz A. Caught in the competitive crossfire: safety-net providers balance margin and mission in a profit-driven health care market. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:w374–w382. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.w374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Hospital AssociationTrendwatch chartbook 2013. Aggregate total hospital margins, operating margins, and patient margins, 1991–2011 [Internet]. Washington, DC: American Hospital Association [accessed 2013 Aug 15]. Available from: http://www.aha.org/research/reports/tw/chartbook/ch4.shtml

- 10.Prieto-Centurion V, DiDomenico R, Godwin P, Grude-Bracken N, Gussin H, Jaffe HA, Joo MJ, Markos MA, Nyenhuis S, Pickard AS, et al. A systematic review of interventions to reduce readmissions following COPD exacerbations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:A2340. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marchetti N, Criner GJ, Albert RK. Preventing acute exacerbations and hospital admissions in COPD. Chest. 2013;143:1444–1454. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casas A, Troosters T, Garcia-Aymerich J, Roca J, Hernández C, Alonso A, del Pozo F, de Toledo P, Antó JM, Rodríguez-Roisín R, et al. members of the CHRONIC Project. Integrated care prevents hospitalisations for exacerbations in COPD patients. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:123–130. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00063205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwok T, Lum CM, Chan HS, Ma HM, Lee D, Woo J. A randomized, controlled trial of an intensive community nurse-supported discharge program in preventing hospital readmissions of older patients with chronic lung disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1240–1246. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calvillo-King L, Arnold D, Eubank KJ, Lo M, Yunyongying P, Stieglitz H, Halm EA. Impact of social factors on risk of readmission or mortality in pneumonia and heart failure: systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:269–282. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2235-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Thirty-day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. JAMA. 2011;305:675–681. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elixhauser A, Au DH, Podulka J.Readmissions for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 2008 [Internet]. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. HCUP Statistical Brief #121 [accessed 2013 July 12]. Available from: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb121.jsp [PubMed]

- 17.Joynt KE, Jha AK. A path forward on Medicare readmissions. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1175–1177. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1300122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC)Chapter 5: Payment policy for inpatient admission. Report to the Congress: Promoting greater efficiency in Medicare. Washington, DC: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission2007. pp. 103–120. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prieto-Centurion V, Joo M, Gussin H, Sandhaus R, Holm K, Casaburi R, Porszasz J, Sullivan J, Cerreta S, Husbands J, et al. Patient and caregiver experience during hospital-to-home transition following COPD exacerbations: an opportunity for peer coaches. Presented at COPD8USA, June 14–15, 2013

- 20.Kangovi S, Grande D. Hospital readmissions: not just a measure of quality. JAMA. 2011;306:1796–1797. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Illinois Department on Aging [Internet]. Springfield, IL [accessed 2012 Apr 18]. Available from: http://www.state.il.us/aging

- 22.City of Chicago. Department of Family & Support Services [Internet]. Chicago, IL [accessed 2013 Apr 18]. Available from: http://www.cityofchicago.org/city/en/depts/fss.html

- 23.Meals on Wheels Association of America [Internet]. Alexandria, VA [accessed 2013 Apr 18]. Available from: http://www.mowaa.org

- 24.Partnership for Prescription Assistance [Internet] [revised 2013 July 8; accessed 2013 Apr 19]. Available from: http://www.pparx.org

- 25.National Network of Libraries of Medicine: health literacy [Internet]. Bethesda, MD [revised 2013 July 31, accessed 2013 Aug 15]. Available from: http://nnlm.gov/outreach/consumer/hlthlit.html

- 26.Kansagara D, Englander H, Salanitro A, Kagen D, Theobald C, Freeman M, Kripalani S. Risk prediction models for hospital readmission: a systematic review. JAMA. 2011;306:1688–1698. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.QualityNetFrequently asked questions: CMS publicly reported risk-standardized outcome measures [Internet]. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [revised 2013 May 16; accessed 2013 July 12]. Available from: https://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?cid=1219069855841&pagename=QnetPublic%2FPage%2FQnetTier4&c=Page

- 28.American Hospital AssociationDetailed comments on the Inpatient Prospective Payment System Proposed Rule for FY 2013 [Internet]. Washington (DC): American Hospital Association [revised 2012 June 19; accessed 2013 July 12]. Available from: www.aha.org/advocacy-issues/letter/2012/120619-cl-ipps.pdf

- 29.Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1822–1828. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naylor M, Brooten D, Jones R, Lavizzo-Mourey R, Mezey M, Pauly M. Comprehensive discharge planning for the hospitalized elderly: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:999–1006. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-12-199406150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, Greenwald JL, Sanchez GM, Johnson AE, Forsythe SR, O’Donnell JK, Paasche-Orlow MK, Manasseh C, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:178–187. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-3-200902030-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Society of Hospital Medicine. BOOSTing care transitions resource room [Internet]. Philadelphia, PA: Society of Hospital Medicine [accessed 2013 July 14]. Available from: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/ResourceRoomRedesign/RR_CareTransitions/CT_Home.cfm

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes Public Health Resource. Community Health Workers/Promotores de Salud: Critical Connections in Communities [Internet]. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [revised 2011May 20; accessed 2013 July 14]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/projects/comm.htm#

- 34.Witmer A, Seifer SD, Finocchio L, Leslie J, O’Neil EH. Community health workers: integral members of the health care work force. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:1055–1058. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.8_pt_1.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kangovi S, Long JA, Emanuel E. Community health workers combat readmission. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1756–1757. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katz MH. The value of community health workers. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1758. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fisher EB, Strunk RC, Highstein GR, Kelley-Sykes R, Tarr KL, Trinkaus K, Musick J. A randomized controlled evaluation of the effect of community health workers on hospitalization for asthma: the asthma coach. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:225–232. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sledge WH, Lawless M, Sells D, Wieland M, O'Connell MJ, Davidson L. Effectiveness of peer support in reducing readmissions of persons with multiple psychiatric hospitalizations. Psychiat Serv (Washington, DC) 2011;62:541–544. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.5.pss6205_0541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Viswanathan M, Kraschnewski J, Nishikawa B, Morgan LC, Thieda P, Honeycutt A, Lohr KN, Jonas D.Outcomes of community health worker interventions Evid Rep Technol Assess 20091–144.A141–A142, B141–B114, passim [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown HS, III, Wilson KJ, Pagán JA, Arcari CM, Martinez M, Smith K, Reininger B. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a community health worker intervention for low-income Hispanic adults with diabetes. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E140. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.120074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Asian Health Services [Internet]. Oakland, CA; [accessed 2013 Aug 16]. Available from: http://www.asianhealthservices.org

- 42.Sheppard VB, Huei-yu Wang J, Eng-Wong J, Martin SH, Hurtado-de-Mendoza A, Luta G. Promoting mammography adherence in underserved women: the telephone coaching adherence study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;35:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guiraud T, Granger R, Gremeaux V, Bousquet M, Richard L, Soukarié L, Babin T, Labrunée M, Sanguignol F, Bosquet L, et al. Telephone support oriented by accelerometric measurements enhances adherence to physical activity recommendations in noncompliant patients after a cardiac rehabilitation program. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93:2141–2147. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baker DW, Dewalt DA, Schillinger D, Hawk V, Ruo B, Bibbins-Domingo K, Weinberger M, Macabasco-O’Connell A, Grady KL, Holmes GM, et al. The effect of progressive, reinforcing telephone education and counseling versus brief educational intervention on knowledge, self-care behaviors and heart failure symptoms. J Card Fail. 2011;17:789–796. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.06.374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Campos MA, Alazemi S, Zhang G, Wanner A, Sandhaus RA. Effects of a disease management program in individuals with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. COPD. 2009;6:31–40. doi: 10.1080/15412550802607410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arora S, Peters AL, Agy C, Menchine M. A mobile health intervention for inner city patients with poorly controlled diabetes: proof-of-concept of the TExT-MED program. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2012;14:492–496. doi: 10.1089/dia.2011.0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Free C, Phillips G, Galli L, Watson L, Felix L, Edwards P, Patel V, Haines A. The effectiveness of mobile-health technology-based health behaviour change or disease management interventions for health care consumers: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giamouzis G, Mastrogiannis D, Koutrakis K, Karayannis G, Parisis C, Rountas C, Adreanides E, Dafoulas GE, Stafylas PC, Skoularigis J, et al. Telemonitoring in chronic heart failure: a systematic review. Cardiol Res Pract. 2012;2012:410820. doi: 10.1155/2012/410820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mattox M.Mobile health roi part 1: readmissions [Internet]. Raleigh, NC: Axial Exchange [revised 2012 December 5; accessed 2013 April 19]. Available from: http://axialexchange.com/blog/article/mobile-health-roi-part-1-readmissions1