Abstract

Study Design

Case report.

Background

Knee pain associated with patella alta (PA) can limit involvement in sport or work activities and prevent an individual from performing basic functional tasks. This case report describes the use of patellar taping to treat an individual with PA.

Case Description

The patient was a 56 year-old female with bilateral knee pain associated with PA. The focus of treatment was to decrease pain during functional activities by using tape to correct patella alignment. The patient was also instructed on specific exercises and mobilizations. The primary outcome measure was the ADL subscale of the Knee Outcome Survey (ADL-KOS).

Outcomes

Initially, the patient scored a 50 on the ADL-KOS and rated her function at 30% of normal. She demonstrated symptom improvement when tape was applied appropriately and was, therefore, instructed in tape application. At discharge, the patient scored a 56 on the ADL-KOS and rated her function at 70% of normal.

Discussion

This case demonstrates the effective use of a taping method for the treatment of pain associated with PA. Taping appears to be a safe, conservative, and cost efficient measure to manage symptoms and to improve activity tolerance in this patient.

Keywords: knee, patellofemoral pain, taping

BACKGROUND

Diffuse anterior knee pain is routinely seen in physical therapy practice, and often characterizes an underlying patellofemoral dysfunction. Research indicates that patellofemoral dysfunction associated with anterior knee pain during functional or recreational activities is one of the most prevalent disorders involving the knee, particularly in individuals who are physically active (Powers, 1998; Fulkerson and Arendt, 2000; Christian et al, 2006, Warden et al, 2008). Ultimately, patellofemoral pain can limit involvement in sport or work activities or, in more debilitating cases, prevent an individual from performing basic functional activities such as rising from a chair and walking.

One proposed contributor to anterior knee pain related to patellofemoral dysfunction is patella alta. Patella alta is a positional fault defined most simply as the superior displacement of the patella within the trochlear groove of the femur (Alemparte, Ekdahl, and Burnier, 2007; Brattstrom, 1970; Escala, et al, 2006; Grelsamer and Meadows, 1992; Jacobsen and Bertheussen, 1974; Neyret, et al, 2002; Seil, et al, 2000; Simmons and Cameron, 1992). Patella alta has been shown to be associated with chondromalacia on the articular surface of the patella and pain (Lancourt and Cristini, 1975; Al-Sayyad and Cameron, 2002). Patella alta has also been implicated in patellar osteoarthritis. The prevalence of patella alta in individuals with patellar osteoarthritis was 6 times that of individuals with normal patellar articular cartilage (Ahlback and Mattsson, 1978). Additionally, both Leung et al (1996) and Kannus (1992) reported that subjects with anterior knee pain demonstrated a significantly more superior patellar position in the affected knee relative to healthy, control knees.

Recent studies provide insight into the mechanism by which patella alta seems to contribute to anterior knee pain. Ward, et al (2005) found that subjects with patella alta had a significantly greater effective moment arm of the quadriceps than subjects with normal patellar alignment (controls). However, for these subjects, the ratio of patellofemoral joint reaction force to quadriceps force was not significantly different, suggesting that the patellofemoral joint reaction force in the patella alta group was less than that of the control group. The authors cautioned, however, that the decrease in joint reaction force in the subjects with patella alta did not necessarily equate to a decrease in patellofemoral contact stress, because a measure of stress must also factor in the size of the area over which the force is applied. The authors speculated, as Kannus (1992) and Lancourt and Cristini (1975) did in earlier studies, that when the patella rests more proximally in the trochlear groove of the femur, as it does with the alignment fault of patella alta, the actual contact area between the patella and the femur may be reduced (Ward, Terk, and Powers, 2005).

As an extension of their previous work, Ward and Powers (2004) conducted a study to assess patellofemoral stress during walking in subjects with and without patella alta. Relative to the controls, subjects with patella alta demonstrated significantly smaller amounts of patellofemoral contact area at the point of maximal stress for both the normal and fast walking conditions. In another study by Ward, et al (2007), patellar height was found to be negatively correlated with the magnitude of the contact area at each knee flexion angle measured, confirming that patellofemoral contact area is reduced in subjects with patella alta. Patellar tilt and lateral glide, however, did not significantly relate to the contact area measured.

Unfortunately, evidence specific to the treatment of pain or instability associated with patella alta is sparse. At the time of this writing, 3 articles were found that specifically addressed the surgical treatment of anterior knee pain and patella alta (Al-Sayyad and Cameron, 2002; Brattstrom 1970; Simmons and Cameron, 1992). No studies were found related specifically to the conservative management of patella alta. Yet, Ward and Powers (2004) have suggested that conservative interventions, such as bracing or taping, directed at increasing patellofemoral contact area might be appropriate for the treatment of patella alta.

Bracing has been found to decrease pain and increase patellofemoral contact area in patients with patellofemoral dysfunction and anterior knee pain (Powers, et al, 2004; Powers, et al, 2004; Powers, et al, 2004). However, in a study to assess the effect of a brace developed to prevent medial and lateral patellar subluxation, Shellock, et al (1994) demonstrated that the brace was ineffective in the presence of patella alta. Of the five knees that did not show improvement in this study, four of them had patella alta. Because the brace used in this study only provided stabilization for medial and lateral patellar glide, it might not have been the most optimal brace design for individuals with patella alta.

The current evidence for the use of taping to treat patellofemoral pain almost exclusively addresses the correction of lateral glide or lateral tilt of the patella. In these studies, tape seems to be effective for reducing patellofemoral pain during functional activities (Bockrath, et al, 1993; Pfeiffer, et al, 2004). Though the mechanisms underlying the positive effects of taping are not understood fully, it is clear that this type of treatment can be beneficial for patients with patellofemoral pain secondary to lateral patellar tilt or glide. Thus, one might speculate that a simple modification of the typical taping procedures used for the patellofemoral joint might also allow for a reduction of the pain associated with a superiorly displaced patella.

Because the evidence reviewed for this paper seems to identify a relationship between anterior knee pain associated with patella alta and decreased patellofemoral contact area, a conservative measure, such as taping, would seem to be a potential treatment option. Unfortunately, as noted previously, the efficacy of such non-surgical treatment alternatives for the management of patella alta is not well documented in the literature. The purpose of this case report, therefore, is to present a case in which a unique method of taping was used, in addition to exercise and education, to decrease bilateral, anterior knee pain secondary to patella alta.

CASE DESCRIPTION

History and Screening

The patient for this case report was a 56 year-old Caucasian woman with bilateral knee pain. Informed consent was obtained and the rights of the patient were protected. She reported a height of 166.37 cm and a weight of 106.14 kg. Her medical history was significant for osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, and multiple hernia operations. Medications used by the patient included Advil for pain (800 mg, twice per day), Calcium (1200 mg per day), Aspirin (81 mg per day), Nexium (20 mg per day), and vitamin D. Although she complained of shortness of breath with activity, there were no other signs suggesting that the patient would be inappropriate for physical therapy or would require referral back to her physician.

The physician provided a referral for physical therapy to evaluate and treat the medical diagnosis of bilateral knee pain. Per subjective report, the patient confirmed the presence of bilateral knee pain (left greater than right) with a duration of 5–6 years. The patient noted that the initial onset of her symptoms was insidious and that the pain, described as a diffuse aching pain, was located in the anterior aspect of both knees.

Prior to the most recent visit to her physician, and subsequent follow-up with physical therapy, the patient reported a significant increase in pain that she was trying to manage with over-the-counter pain medication. The patient noted that the pain had increased to a point that she could not stand from a sitting position without assistance and had difficulty walking and climbing stairs. Given the severity of the pain, the physician administered a Cortisone injection into both knees one week prior to beginning physical therapy. No specifics were provided regarding the dosage or the location of the injections. According to the patient, the injections relieved most of her pain and improved her function, but she was still taking multiple doses of Advil per day to manage her symptoms. At the time of the initial physical therapy evaluation, the patient reported 2/10 achy pain in the anterior aspect of both knees that worsened with sit to stand and stair climbing.

Prior to the examination, the patient completed the Activities of Daily Living Scale of the Knee Outcome Survey (KOS), a reliable and valid outcome measure of knee pain and function for a variety of diagnoses, including patellofemoral pain (Irrgang, et al, 1998). Scores on the KOS range from 0–100 (Standard Error of Measurement and Minimum Detectable Change (MDC67), 5.15) with 0 representing a complete loss of function and 100 representing no loss of function with complete absence of symptoms. When the patient initially completed this form, she obtained a score of 50, suggesting a 50% loss of function. On a separate subjective question that has not been fully validated in the literature, the patient rated her current level of function during daily activities as 30 out of 100, with 100 being the level of function prior to pain or injury. Thus, despite the reported success of the injections, the patient was still documenting significant functional limitation as a result of her knee pain.

According to the patient, the anterior knee pain was still limiting her ability to perform work, household, and recreational activities. The patient was a registered nurse who worked in a physician’s clinic. Her job required both desk work and patient care. Therefore, the patient needed to transition from sitting to standing multiple times per day. Additionally, the patient lived in a multi-story home. Thus, the patient had to ascend and descend the stairs several times per day. Both of these activities seemed to contribute to the persistence of her anterior knee pain. Therefore, the patient felt limited in the amount of exercise that she could perform to lose weight and maintain optimal health.

Ultimately, the patient’s goals for physical therapy were to maintain or to improve upon the progress achieved from the injections, to decrease her need for pain relieving medication, to build strength and endurance in her lower extremities, and to improve her tolerance for walking, particularly for fitness. The patient was motivated to participate in physical therapy in order to optimize her tolerance of functional activities and to improve her overall health.

Objective Measures

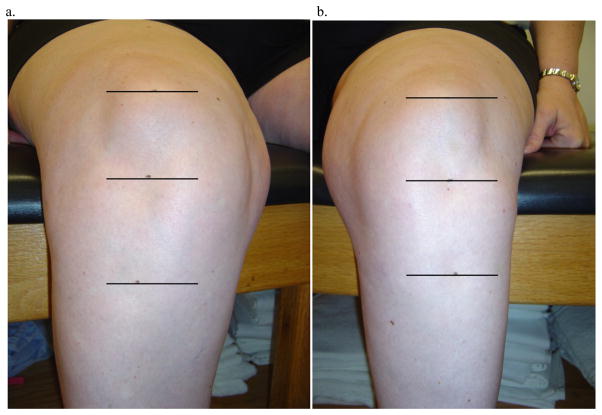

Following the subjective history, an objective examination was performed in order to identify specific movement and postural factors that might be contributing to the patient’s pain and to quantify measures of muscle performance, range of motion, and alignment (table 1). Visual observation was first used to determine postural alignment in standing. The patient was noted to have bilateral hip adduction with medial rotation of the femurs. In addition, the patient stood with her knees slightly flexed. Inspection of her patellar alignment suggested that her patella was superiorly displaced (figure 1).

Table 1.

Summary of the Key Results from the Physical Examination

| Test Item | Subject’s Response | Patient Findings Supporting MSI† Diagnosis of Patellar Tracking Syndrome with Superior Glide: Patella Alta |

|---|---|---|

| Alignment | No pain increase | Superior displacement of patella Adduction and medial rotation of the femur |

| Bilateral hip and knee flexion (partial squat) | Pain increase | Correction of resting alignment of patella decreased pain with movement |

| Active Knee Extension in Sitting | Pain increase; Crepitus | Correction of resting alignment of patella decreased pain with movement |

| Physiological Range of Motion of the Tibiofemoral Joint | Pain increase | Limited range of motion into flexion |

| Accessory Range of Motion Patellofemoral joint | No pain increase | Limited accessory mobility of patellofemoral joint in an inferior direction |

| Modified Ober Test | No pain increase | Shortened length |

| Manual Muscle Testing | Pain increase | Weak posterior gluteus medius bilaterally Quadriceps not tested secondary to pain Gluteus maximus not tested secondary to pain |

Movement System Impairment

FIGURE 1.

Picture illustrating the patellar alignment of the right (a) and left (b) knee of the patient. The three lines indicate the superior margin of the patella, the inferior pole of the patella, and the tibial tubercle.

Therefore, a more quantitative assessment of her patella alignment was performed based on the Insall-Salvati (IS) ratio,which compares the length of the patellar tendon (TL) to the height of the patella (PL) (Insall and Salvati, 1971).. Insall and Salvati (1971) proposed that the ratio between patellar tendon length and patella height should normally be one and that two standard deviations (SD) above or below the mean should be considered abnormal. Thus, patients that have a TL/PL ratio of 1.2 or greater (1 + 2 SD) are characterized as having PA. To screen the current patient for PA , the length of the patella tendon was measured using the inferior pole of the patella and the tibial tubercle as landmarks. The height of the patella was measured using the superior margin and the inferior pole of the patella as landmarks. The values were then compared to determine the IS ratio (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Lateral radiograph of the subject’s left knee used to examine patella alignment

However, because clinical measures for patella alta have been deemed unreliable (Insall, Flavo, and Wise, 1976), the clinical measurements taken were confirmed with more specific measurements of the lateral radiograph (figure 2) that were provided by the referring physician. To assess for PA on the lateral radiograph provided, the length of the patella tendon was compared to the diagonal height of the patella (Seil, 2000). While the landmarks used to assess patellar tendon length were the same as those that were palpated clinically, the landmarks used to assess patella height were different. Using the radiograph, patella height was measured from the posterior, superior margin of the patella to the anterior, inferior pole of the patella. According to Seil et al (2000), measurement of patella alta using a lateral radiograph and the landmarks described has been shown to be associated with minimal interobserver error (0.044 ± 0.047 with a Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient of 0.86). Based on the calculated ratio values listed in table 2, this patient appeared to demonstrate bilateral patella alta that was worse on the left than on the right.

TABLE 2.

Clinical and radiographic measurements of patellar alignment

| Left | Right | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical | Radiographic | Clinical | Radiographic | |

| Height of the patella | 4.5 cm | 4.94 cm | 4.5 cm | N/A |

| Length of patella tendon | 6.3 cm | 6.95 cm | 5.9 cm | N/A |

| Insall-Salvati ratio | 1.4 | 1.41 | 1.31 | N/A |

While the patient was standing, she was instructed to perform bilateral hip and knee flexion (partial squat). The patient reported pain at end-range with this movement. Passive correction of femoral adduction and rotation did not significantly decrease the symptoms reported. However, with a manual glide of the patella in an inferior direction, the patient did note a reduction of pain. This correction was provided to the patient in an effort to decrease the resting height of the patella in the trochlear groove prior to movement.

In sitting, the patient was first asked to actively extend each knee in order to assess her movement strategy. During these movements, the patient reported increased pain, and significant crepitus was noted. Manual gliding was performed to theoretically modify the resting height of the patella before knee extension was performed, resulting in decreased pain in both knees. The manual glide provided at the patella did not prevent the superior translation of the patella that might normally occur with quadriceps recruitment. Subsequent quadriceps strength testing was not performed because of the potential for pain

Palpation of relevant structures around each of the knees was also performed in sitting. Specifically, the patient reported no change in symptoms in either knee with palpation of the quadriceps and patellar tendons, the medial and lateral joint lines, or the infrapatellar fat pad. Additionally, there was no evidence of localized inflammation of the quadriceps or patellar tendons such as swelling or increased heat.

Active range of motion of the knee was assessed in supine. Knee flexion was 120 degrees bilaterally and knee extension was -5 degrees bilaterally. The patient reported anterior knee pain and stiffness at the end of knee flexion range of motion. Accessory motion of the patellofemoral joint was assessed and found to be limited bilaterally, but pain free. Accessory motion of the tibiofemoral joint was not assessed. Special tests to assess ligamentous and meniscal integrity in supine were not performed because the patient’s history was not suggestive of either impairment.

In left and right side-lying, the patient had slight medial rotation of the top leg on both sides. The length of the TFL-ITB was tested using the modified Ober test, in which the knee was flexed to 90 degrees. The test was positive for impaired length of the TFL-ITB. The strength of the posterior gluteus medius was tested using standard manual muscle testing procedures as described by Kendall, et al (1993); the test results were 3/5 for both the left and the right.

In prone, no specific postural abnormalities were noted. Strength testing of the gluteus maximus was not performed secondary to the concern regarding her multiple hernia operations and the potential risk of injury to her lower back with end range hip extension. Next, functional activities such as sitting to standing, sleeping, gait, and stair climbing were evaluated. Transitioning from sitting to standing, the patient required upper extremity support and noted significant pain in her anterior knee. To modify her symptoms the patient was first cued to transition from sitting to standing at the edge of her chair. With this correction, the patient was able to stand more easily, but the anterior knee pain was unchanged. Therefore, using the same rationale as described previously, a force was applied manually to the patella in an inferior direction during the sit-to-stand motion, which resulted in a significant reduction of pain.

When asked to demonstrate her sleeping position, the patient assumed a side-lying position with her top lower extremity resting in hip flexion and medial rotation. Cues were provided to correct her sleeping position in order to determine whether the patient was more or less comfortable in side-lying in response to changes in alignment. When a pillow was placed between her lower extremities, the patient did, in fact, report increased comfort, but, again, no specific changes in knee pain were noted.

During the examination, the patient did not report pain during walking. However, excessive medial femoral rotation was observed during the stance phase of gait from foot flat to push-off. No corrections were provided at the time of the examination because her gait was not painful. By contrast, ascending and descending the stairs did increase her pain. It was not possible to provide a manual glide to the patella during this task, therefore, no conclusions could be made regarding the possible effects of patellar mal-alignment.

The patient was able to complete the examination described above with only a minimal increase in her symptoms. A diagnosis was determined based on these examination findings, and it was deemed safe to continue the initial visit and to provide appropriate treatment.

Diagnosis

The examination findings were consistent with a diagnosis of Patellar Tracking Syndrome with Superior glide (Harris-Hayes, Sahrmann, Norton, and Salsich, 2008) (APPENDIX A). This diagnosis describes anterior knee pain that is associated with an impaired relationship between the patella and the femur, which, in this case, was patella alta. The key finding supporting this diagnosis was the consistent decrease in pain associated with manual, inferior correction of the patella. In addition, the patient described diffuse anterior knee pain that was not specific to the quadriceps tendon, the patellar tendon, or the tibiofemoral joint. Pain underneath or around the patella is considered indicative of a patellar alignment and tracking problem, particularly when the pain is consistently exacerbated with activities such as, stair climbing, sitting to standing, and partial squat. Finally, open chain activities such as knee extension in sitting were also painful, which supports the diagnosis of Patella Tracking Syndrome with Superior Glide because knee extension from 90 degrees of knee flexion to 25 degrees can increase patellofemoral joint reaction force (Grelsamer and Klein, 1998). Because patella alta seems to be associated with a decrease in the size of the contact area between the patella and the femur (Grelsamer and Meadows, 1992; Ward, Terk, and Powers, 2005; Ward, Terk, and Powers, 2007), any significant increase in the joint reaction force, such as that which occurs with active knee extension, could significantly change the overall contact stress within the patellofemoral joint.

APPENDIX A.

Movement System Impairment (MSI) Syndromes Associated with Knee Pain (Harris-Hayes, Sahrmann, Norton, and Salsich, 2008)

| Movement System Impairment Syndrome | Description of Syndrome | General Location of Symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Tibiofemoral Rotation Syndrome | Impaired rotation of the tibiofemoral joint, including either excessive medial rotation of the femur or lateral rotation of the tibia. Can be associated with either varus or valgus deformity | Pain with located on the joint line of the knee with tibiofemoral rotation in weight-bearing or non weight-bearing. |

| Patellar Tracking Syndrome | Impaired alignment or tracking of the patella within the trochlear groove of the femur | Pain is located in the anterior knee either in a peri-patellar or retro-patellar distribution |

| Tibiofemoral Hypo-mobility | Limitation in the physiological range of motion of tibiofemoral joint. Could either results from degeneration or prolonged immobilization | Deep joint pain that will increase with weight-bearing and decrease with rest. Pain is also associated with stiffness |

| Knee Extension Syndrome | Dominance of the quadriceps muscle produces an excessive pull on the patella, the patellar ligament, and/or the tibial tubercle | Pain is located in either the supra- or infra- patellar tendon, particularly with activities that require knee extension |

| Knee Hyperextension | Impairment of the knee extensor mechanism, including dominance of the hamstrings and/or poor functional performance of the quadriceps. Result in prolonged knee hyperextension. | Pain can be located at the joint line of the tibiofemoral joint (anterior or posterior), the infrapatellar tendon, or anterior around the patella |

| Tibiofemoral Accessory Hyper-mobility | Excessive motion/laxity at the tibiofemoral joint. May have a history of an ACL/PCL injury | May not have pain. Most common complaint is a feeling of instability or “giving way” |

| Tissue Impairment Syndrome | Tissue injury/impairment that can occur in the absence of a movement impairment syndrome or secondary to an acute trauma or surgery | Pain varies in location and is associated with the structures of the knee involved with the trauma/injury or surgery |

INTERVENTION

The patient was seen for 11 visits, including the initial evaluation, over a period of 6 months. The extended duration of physical therapy was necessary to accommodate the patient’s travel schedule, as well as, to provide a mechanism for which to monitor the long-term success of treatment. During this time period, the emphasis of the treatment provided to the patient was on the correction of the positional fault of the patella in both lower extremities using tape. However, to improve the effectiveness of the taping method used to correct patellar alignment, treatment also addressed the correction of the patient’s movement impairments with exercise prescription, as well as, functional training for the management of symptoms throughout the day.

Following the initial evaluation, four exercises were prescribed to address issues with regards to muscle length and motor recruitment (table 3). These exercises were performed by the patient at subsequent visits for review, and corrections were provided to the patient as needed.

TABLE 3.

Exercises and parameters for home exercise program

| Exercise | Purpose | Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Hip and knee flexion in supine | Improve knee flexion and extension ROM† | 10–15 repetitions, 2 times per day |

| Hip flexor stretch in supine | Improve the flexibility of the hip flexors, particularly the TFL-ITB†† | 3–5 repetitions (10–15 second hold), 2–3 times per day |

| Knee flexion in prone | Improve the flexibility of the hip flexors, particularly the Rectus Femoris | 5–10 repetitions, 2 times per day |

| Hip abduction with lateral rotation in side-lying | Strengthen the Posterior Gluteus Medius | Level 1: 5–10 repetitions, 1–2 times per day Level 2: 5–10 repetitions, 1–2 times per day |

Range of motion

Tensor Fasciae Latae – Iliotibial Band

In an attempt to reduce the superior displacement of the patella, the patient was also instructed to perform patellar mobilizations in an inferior direction as illustrated by Kisner and Colby (1996). The patient was instructed to perform three sustained inferior patellar glides on both knees for 30 seconds each. The patient was not educated on specific mobilization grades. Rather, she was instructed to mobilize the patella within a pain free range.

Exercises specific to the impairments found during an examination are certainly an important component of treatment. However, unless the patient modifies his or her performance of daily activities that are contributing to pain, the long-term success of a home exercise program could be limited. In the present case, transitioning from sitting to standing and stair climbing were contributing to the symptoms that she was experiencing. Therefore, the patient was educated on specific compensatory and component strategies of movement to reduce the amount of patellofemoral stress experienced during these daily activities (table 4).

TABLE 4.

Instructions provided for functional activities

| Functional Activity | Instructions Provided |

|---|---|

| Sit to Stand | Sit on the edge of the chair with feet slightly behind the knees. Shift trunk anteriorly to improve the ability to effectively recruit the quadriceps and the hip extensors. Use upper extremity support for assistance and safety |

| Stair Climbing – Ascent | Shift her weight anteriorly and to push up and forward using the gluteals and quadriceps in a more efficient manner. Use the handrail if available |

| Stair Climbing – Descent | Actively plantarflex the foot of the swing limb to contact the step below more quickly. Use compensatory pattern of motion, as needed, by descending one step at a time |

Given the degree of her patella alta, exercises and education were not sufficient in reducing her pain to a tolerable level. According to Mueller and Maluf (2002), some form of external support is often needed to reduce the physical tissue stress at a particular joint and to control symptoms. Taping is one form of support often employed by physical therapists to provide stabilization to a joint or assistance to a particular movement. In this case, Leukotape was used to provide stabilization to the patella in order to reduce the stress associated with the superior displacement noted. Prior to taping, the patient was educated on the purpose of the tape, doffing instructions, and appropriate skin care following removal. Because the patient believed she might be allergic to the tape, she was instructed, after the initial examination, to apply a test strip of tape and to monitor the skin for itching, redness, or rash.

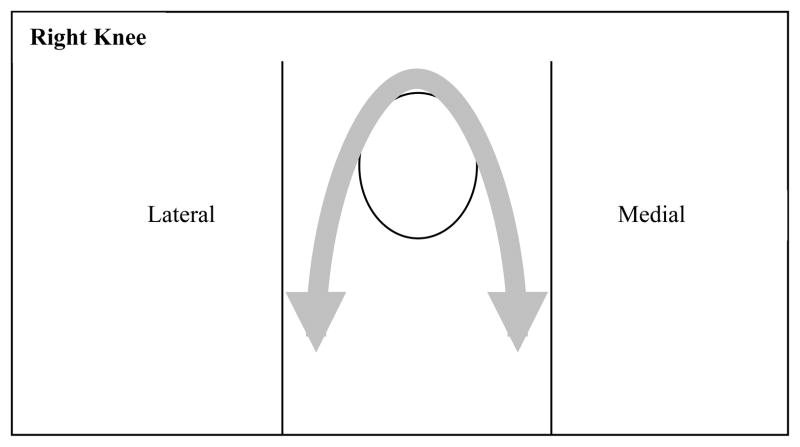

During her first follow-up visit, the patient reported that she did not experience an adverse skin reaction secondary to the test strip of tape. The patient, therefore, consented to the taping intervention and tape was applied to both knees. For this patient, a novel method of taping was employed. Tape was applied in an inverted “U” pattern over the anterior knee to apply an inferiorly directed force at the superior margin of the patella.

The procedures used to apply the tape in this fashion were as follows. The patient was positioned in long-sitting and the knee was supported by a small towel roll. Cover-roll was applied first to protect the skin from the adhesive of the Leukotape. To apply the Leukotape, a strip of tape approximately 12 inches long was positioned at the superior margin and was affixed in such a manner that half of the width of the tape was on the patella while the other half of the tape was over the quadriceps tendon. An inferior force was then applied through the tape to the patella with care taken not to compress the patella within the trochlear groove. As the inferior force was applied, the tape was affixed on either side of the knee forming an inverted “U” shape over the patella (figures 2 and 3). Three to four additional strips of Leukotape were applied in a staggered fashion to increase the stability of the support. Initially, the patient was taped bilaterally.

FIGURE 3.

Diagrammatic representation of the direction of force applied through taping to the patellofemoral joint

As the treatment progressed and the tape was deemed successful at reducing her symptoms, the patient was instructed how to tape her knees independently. The same method of taping described above was used by the patient to self-tape. Self-taping allowed the patient to provide a more consistent, inferior force to the patella to help relieve her symptoms. The patient was instructed to apply the tape unilaterally and to alternate which knee was taped in order to manage her pain bilaterally and to protect her skin. Periodically, the therapist reviewed the tape applied by the patient to ensure that the taping procedure was being performed correctly. The patient continued self-taping for both knees for the duration of therapy, and was instructed to tape herself as needed following discharge.

The final component of the intervention provided to the patient was education regarding the initiation and progression of a conditioning program for general health and fitness. As the patient progressed in therapy, she was instructed on the performance of a walking program to improve her cardiovascular health while minimizing her symptoms. Because the patient had access to a pool, she was advised about the potential benefits of water exercise and cross-training and was instructed to use the pool 1 to 2 times per week. When unable to exercise in pool, the patient was given the alternative of using a stationary bike instead.

During the course of therapy, the patient demonstrated compliance with taping, as well as, the prescribed home exercises and her conditioning program. Ultimately, the patient was motivated to improve and to address her health and weight concerns with appropriate exercise.

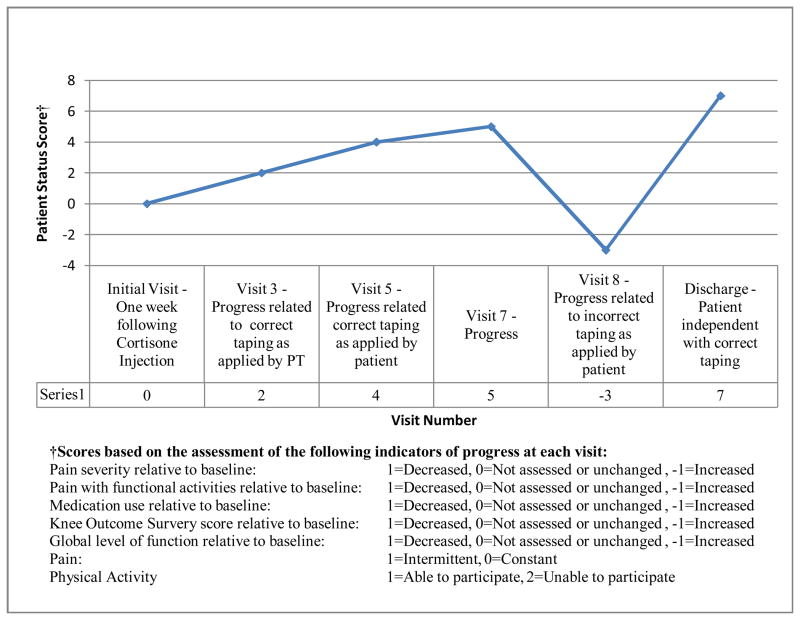

OUTCOMES

To summarize patient improvement over the time period for which she was seen for physical therapy, a novel assessment of patient progress was developed (figure 5). Specifically, seven indicators of patient progress chosen by the authors were obtained from the patient chart. These indicators were assessed at 6 different time points throughout the duration of treatment. All indictors, excluding whether the pain was constant or intermittent and the ability to participate in physical activity such as walking and swimming, were judged relative to baseline measures at the initial evaluation. Other indicators of progress were pain severity, pain with functional activity as reported by the patient, medication use, Knee Outcome Survey score, and global level of function as reported by the patient on the Knee Outcome Survey.

Figure 5.

Line graph demonstrating patient status according to the assigned scores from selected indicators of progress

For each of the five indicators that were assessed relative to baseline measures a score was provided for each patient visit. If the indicator of progress was either not assessed or unchanged relative to baseline, a score of 0 was assigned. If the indicator of progress had improved relative to baseline a score of 1 was assigned. Conversely, if the indicator of progress had worsened, a score of -1 was assigned. For the indicators of progress that were not compared to baseline, a score of 0 or 1 was assigned according to the following method. If the pain was described as constant, a score of 0 was assigned whereas if the pain was described as intermittent, a score of 1 was assigned. Likewise, if the patient was unable to participate in physical exercise such as walking or swimming, a score of 0 was assigned. If the patient reported participation in physical exercise such as walking or swimming, a score of 1 was assigned. Therefore, for each visit assessed, the patient could receive a cumulative score representing patient progress as high as 7 or as low as -5. When applying this novel assessment of patient progress, it is clear that the patient did steadily improve before worsening at visit 8. Assessment of these same indicators of progress at discharge also demonstrated significant progress relative to both visit 8 and baseline measurements. A more detailed description of specific patient progress, including the rationale for the patient’s worsened status at visit 8 follows.

After initiating patella taping, the patient reported feeling “100% better” by the third visit, which was approximately four weeks after the initial evaluation. During the 3rd visit, the patient noted that the transition from sitting to standing was easier and less painful and that the tape specifically improved her ability to ascend the stairs. Therefore, as noted previously, the patient was provided instructions for self-taping. By the 5th visit, the patient reported minimal pain in both knees (1–2/10 pain that was not constant) and improvement in all functional activities. The patient also noted that she had reduced her use of pain medication to 800 mg of Advil as needed. Because of the progress demonstrated to this point, the patient was instructed to begin the conditioning exercises as described previously and the frequency of physical therapy was reduced to one visit every two weeks.

The patient’s symptoms, however, worsened by her 6th visit. She reported a general increase in pain with walking, sitting to standing, and stair climbing. The patient attributed her symptoms to an increase in her activity level. She was walking at the gym more frequently than had been recommended. Therefore, the patient was provided instructions regarding activity moderation and aquatic exercise to limit the cumulative stress on the patellofemoral joint.

By the 7th visit, taping and moderate exercise enabled the patient to manage her symptoms more appropriately. In fact, the patient reported that her pain was only minimal and that the taping was helpful. Thus, the patient was instructed to continue her home program of taping and exercise as prescribed and to return in 2–3 weeks for evaluation and follow-up.

When the patient returned for her 8th visit, she noted that she had progressively worsened. She was now having more pain with the transition from sitting to standing and with walking. Though she was compliant with the home exercise program and her conditioning routine (walking and swimming), the pain was starting to limit more of her functional abilities. At this point, the tape was no longer working to relieve her symptoms. Her regression was confirmed by the change in her KOS score. Upon re-evaluation at her 8th visit, the patient only scored a 38.5 on her Activities of Daily Living Scale and rated her level of function at 20% of normal.

The patient could not attribute her increase in symptoms to any specific activity or event. However, it was observed, that the tape on the patient’s knee had been applied incorrectly. The tape was positioned superior to the margin of the patella around the distal quadriceps muscle and was providing no stabilization force (figure 6). The self-taping being performed by the patient was ineffective. Therefore, the patient was re-instructed on the appropriate taping technique and was asked to follow-up in one week.

FIGURE 6.

Incorrect taping method as performed by the patient. Demonstrated on a model knee.

Upon return to physical therapy after one week, the patient reported a significant improvement in her symptoms with the correction of the taping application. Indeed, the patient reported decreased pain with sit to stand and noted that she was able to walk approximately one mile on the track with minimal difficulty. Visual observation of the tape applied by the patient revealed that she had positioned the tape correctly. The patient was instructed to gradually progress her conditioning program, continue with the taping, and follow-up in one month.

Despite having to cope with an episode of pneumonia, the patient reported at the one-month follow-up (10th visit) that she had been able to manage her pain with the taping and exercise. In fact, the patient noted that she was having minimal difficulty with walking and was able to actively participate in a previously planned tour to Washington D.C. Her average pain was reported to be a 1–2/10 and she noted decreased use of pain medication (actual dosage was not provided). Stair climbing was still challenging, but the patient stated that it was easier relative to her baseline level of function at the initial evaluation. At this time, the patient completed a 3rd KOS. She scored a 56 on the Activities of Daily Living Scale and rated her level of function at 70% of normal (table 5).

TABLE 5.

Summary of KOS† scores

| Visit / Date | Activities of Daily Living Score | Rating of Current Level of Function |

|---|---|---|

| Visit 1 – Initial Evaluation (IE) | 50 | 30% |

| Visit 8 – 99 days post IE | 38.5 | 20% |

| Visit 10 – 168 days post IE | 56 | 70% |

Knee Outcome Survey

In addition to the administration of the KOS, many of the tests assessed during the initial evaluation were re-evaluated at this visit (10th visit). Based on clinical measurements, the alignment of the patella had not changed significantly. The IS ratio calculated for the alignment of her right patella was 1.31 while the IS ratio for her left patella was 1.4. The patient did, however, demonstrate improvement in posterior gluteus medius strength to 3+/5 bilaterally and increased knee flexion range of motion (128 degrees on the right and 125 degrees on the left). Knee extension range of motion was not reassessed. Functionally, the patient reported minimal pain and no obvious movement impairments with sit to stand and gait. Stair climbing was first assessed without tape and was found to be painful. With the application of the tape to provide an inferior force to the patella, the patient reported a significant decrease in symptoms. Based on the results of this re-evaluation, it was clear that the patient had improved relative to her baseline level and that she was able to effectively manage her symptoms with tape and exercise.

The patient returned to therapy for follow-up two weeks later. During this visit, the patient subjectively noted that pain was no longer limiting function. Furthermore, she was walking 3–4 times per week without pain and was exercising in the pool 1–2 times per week. Taping and exercise were reviewed and the patient was discharged with instructions to continue her prescribed therapy.

DISCUSSION

This case illustrates the benefit of conservative management of patella alta through taping, education, and exercise in a 56 year old woman presenting to physical therapy with bilateral, anterior knee pain. This patient is somewhat unique in that her age is outside the typical age range of subjects who are participants in studies regarding patellofemoral pain, specifically pain related to patella alta (Neyret, et al, 2002; Powers, et al 2004; Ward and Powers, 2004; Ward, Terk, and Powers, 2005; Ward, Terk, and Powers, 2007). However, in a recent study, Stefanik et al (2010) demonstrated that in subjects that were 50–79 years old, patella alta was significantly associated with specific characteristics of patellofemoral joint osteoarthritis such as cartilage damage, bone marrow lesions, and sub-chondral bone attrition. These data support a previous study by Ahlback and Mattsson (1978) in which the authors demonstrated that the frequency of patella alta was approximately 6 times higher in knees with patella osteoarthritis than in those with normal articular cartilage. Though the outcomes presented in this case study might not be generalizable to the patient population as whole, particularly young, athletic individuals, it does illustrate a potentially beneficial intervention strategy for a demographic group not well represented in the literature with regards to patellofemoral pain.

The patient in this case demonstrated a reduction in pain and a significant improvement in her functional status with such conservative measures. Her overall improvement was reflected by the novel assessment of patient progress developed for this case and by her scores on the KOS ADL subscale. Recall that the patient initially completed the KOS shortly after the cortisone injections were administered by her physician. Initially, the KOS score on the ADL subscale (50/100) suggested moderate debilitation. However, the patient subjectively reported that her knee was functioning at only 30% of normal. The discrepancy in scores seemed to suggest that, although the injections were helpful, the patient perceived that her knees were not functioning normally.

The final time the KOS was completed by the patient, her ADL subscale score had marginally improved to 56/100. Although this score represented an improvement relative to her baseline score, the 6 point change was likely not clinically relevant (Irrgang, et al, 1998). It is, however, interesting to compare her final KOS score at the 10th visit to the score she received after the 8th visit. Approximately 3 months after the cortisone shots administered by the physician, the patient scored a 38.5/100 on the ADL subscale of the KOS, which represents a significant decrease in function relative to her baseline score. Additionally, the patient subjectively rated her global level of function of her knee at 20% of normal. There seemed to be multiple causes for this change in the KOS score, including incorrect taping application and excessive physical activity. Yet, when the patient was re-instructed on the correct procedures for taping and was provided education for activity moderation, she improved quickly. In fact, the score on the KOS ADL subscale improved by 17 points (38.5/100 to 56/100) when assessed at the 10th visit, 2 months later. The amount of change between the 2nd and 3rd administration of the KOS was clinically relevant (Irrgang, et al, 1998). Additionally, by the 10th visit the patient rated the overall function of her knee at 70% of normal, representing a significant improvement in her perception of knee function in response to conservative measures. The significant improvement in the patient’s perceived level of function also seemed to correlate well with the overall progress demonstrated by the novel scoring system developed for this case

Ultimately, the documented improvements made with taping, exercise, and education afforded the patient the opportunity to initiate and progress a conditioning program for general health and fitness that was previously precluded by patellofemoral pain. Though she did not demonstrate complete resolution of her symptoms by discharge, the patient was able to manage her symptoms independently and participate fully in her daily activities. Given her age, the duration of her pain prior to therapy, and the initial severity of her symptoms prior to the injections, it was not surprising that the patient’s symptoms did not completely resolve. However, it seems reasonable to conclude that if she continues to tape on an as needed basis and performs her home exercise and conditioning program, that she should be able to prevent a reoccurrence of the severe symptoms that prompted her to seek medical attention initially.

Unfortunately, the mechanism underlying the potential effectiveness of the taping method used is unclear from this case report. Clinically, the patient demonstrated improvement with regards to symptoms, but additional imaging studies that could have provided information about patella alignment and patellofemoral contact area were not performed. Based on the existing evidence demonstrating a decrease in patellofemoral contact area with patella alta (Ward and Powers, 2004; Ward, Terk, and Powers, 2005), it is possible that the reduction in anterior knee pain demonstrated by the patient in this case in response to conservative measures was related to an increase in the patellofemoral contact area, which could potentially decrease joint stress.

As noted previously, the evidence generally supports the use of taping to treat patellofemoral pain that is associated with lateral patellar glide or tilt (Bockrath, et al, 1993; Pfeiffer, et al, 2004). However, there seems to be no evidence for the use of taping with patients with patella alta. In the present case, rather than applying the tape to provide a medial stabilization force to the patella, the tape was used to provide an inferior force. This method was utilized because passive stabilization of the patella in an inferior direction during the initial examination resulted in decreased pain for several functional activities including the transition from sitting to standing. The result, as with studies examining patellar taping with a medial stabilization force (Bockrath, et al, 1993; Pfeiffer, et al, 2004), was decreased pain and increased function. Future research could better elucidate the underlying mechanisms of the taping method used in this case by describing patellofemoral contact area and patella alignment with and without tape. This could be readily accomplished with imaging techniques that were beyond the scope of this case study, but have been previously described (Ward and Powers, 2004; Ward, Terk, and Powers, 2005).

Imaging studies to determine patellofemoral relationships, including contact area and alignment, would also be important to determine whether tape should be applied in a specific direction, such as it was in this case. The study by Shellock, et al (1994) seems to suggest that the direction of the tape might be important. These authors studied a brace that provided a medial stabilization force to the patella and found positive benefits in all subjects except those presenting with patella alta.

Because a significant reduction in pain was noted in this case, it is possible that taping the superior margin of the patella to provide an inferiorly directed force produced some subtle changes in the resting alignment of the patella (inferior displacement) that contributed to a change in the contact area magnitude of the patellofemoral joint. However, no lasting changes in patellofemoral alignment were noted at discharge.

The taping technique used in the present study, rather than changing resting patellar alignment or patellofemoral contact area, could have also caused a reduction in pain through neurophysiological mechanisms. Specifically, some authors have demonstrated that taping to correct medial or lateral gliding of the patella may alter the activity of the surrounding musculature, including the vastus medialis obliquus and the vastus lateralis (Gilleard, McConnell, and Parsons, 1998). Because the type of changes in muscle activity as a result of patella taping are not always consistent in the literature or specific to the type of taping applied, it has been suggested that taping may contribute to pain reduction through cutaneous stimulation of the sensory fibers of the skin (Christou, 2004 and Herrington and Payton, 1997). It is reasonable to suggest that the pain reduction reported by the patient in the present case was either the direct result of cutaneous stimulation or the indirect result of changes in muscle activity patterns. However, when the tape was applied incorrectly by the subject, her pain significantly worsened despite continued sensory stimulation by the tape, Certainly, given the numerous possible means by which taping, in general, has been deemed to be effective, once the mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of this specific taping method are better understood, the implications for clinical practice would be more significant.

CONCLUSIONS

This case study demonstrates the successful implementation of a conservative treatment plan to manage anterior knee pain associated with patella alta. Exercises were prescribed to address specific musculoskeletal impairments identified during the examination, education was provided to improve functional activity performance, and tape was applied to decreased pain. Of these three conservative interventions, taping the patella with an inferiorly directed force seemed to most significantly benefit the patient. Future research could certainly help to explain the biomechanical mechanisms underlying the taping method used, but the current case study provides some preliminary evidence for taping that can be practically applied in a clinical setting, in addition to the correction of the underlying movement impairments, to control pain and to improve function in patients with patella alta.

FIGURE 4.

Picture illustrating the application of tape for the treatment of patella alta on a model knee

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Shirley Sarhmann, PT, PhD, FAPTA for her ideas and feedback related to this manuscript, Barbara Norton, PT, Phd, FAPTA and Linda Van Dillen, PT, PhD for their assistance with editing and Erin Stanley, SPT, Sara Culley, SPT, and Christine Koh for their assistance in manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

IRB Approval: The Human Research Protection Office does not require IRB approval for a Case Report. Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no declarations of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- 1.Ahlback S, Mattsson S. Patella alta and gonarthrosis. Acta Radiologica: Diagnosis. 1978;19:578–584. doi: 10.1177/028418517801900404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Sayyad MJ, Cameron JC. Functional outcome after tibial tubercle transfer for the painful patella alta. Clinical Orthopaedics. 2002;396:152–162. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200203000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alemparte J, Ekdahl M, Burnier L, Hernandez R, Cardemil A, Cielo R, Danilla S. Patellofemoral evaluation with radiographs and computed tomography scans in 60 knees of asymptomatic subjects. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 2007;23:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bockrath K, Wooden C, Worrell T, Ingersoll CD, Farr J. Effects of patella taping on patella position and perceived pain. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1993;25:989–992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brattstrom H. Patella alta in non-dislocating knee joints. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica. 1970;41:578–588. doi: 10.3109/17453677008991549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Escala JS, Mellado JM, Olona M, Gine J, Sauri A, Neyret P. Objective patellar instability: MR-based quantitative assessment of potentially associated anatomical features. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2006;14:264–272. doi: 10.1007/s00167-005-0668-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grelsamer RP, Klein JR. The biomechanics of the patellofemoral joint. The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 1998;28:286–298. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1998.28.5.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grelsamer RP, Meadows S. The modified Insall-Salvati ratio for assessment of patella height. Clinical Orthopaedics. 1992;282:170–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris-Hayes M, Sahrmann SA, Norton BJ, Salsich GB. Diagnosis and management of a patient with knee pain using the Movement System Impairment Classification System. The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 2008;38:203–213. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2008.2584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Insall J, Flavo KA, Wise DW. Chondromalacia patellae. A prospective study. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1976;58:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Insall J, Salvati E. Patella position in the normal knee joint. Radiology. 1971;101:101–104. doi: 10.1148/101.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Irrgang JJ, Snyder-Mackler L, Wainner RS, Fu FH, Harner CD. Development of a patient reported measure of function of the knee. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1998;80-A:1132–1145. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199808000-00006. American Volume. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobsen K, Bertheussen K. The vertical location of the patella. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica. 1974;45:436–445. doi: 10.3109/17453677408989166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kannus PA. Long patellar tendon: Radiographic sign of patellofemoral pain syndrome – A prospective study. Radiology. 1992;185:859–863. doi: 10.1148/radiology.185.3.1438776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kendall FP, McCreary EK, Provance PG. Muscles: testing and function. 4. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kisner C, Colby LA. Therapeutic exercise: foundations and techniques. 3. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lancourt JE, Cristini JA. Patella alta and patella inferea. Their etiological role in patellar dislocation, chondromalacia, and apophysitis of the tibial tubercle. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1975;57:1112–1115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leung YF, Wai YL, Leung YC. Patella alta in southern China. International Orthopaedics. 1996;20:305–310. doi: 10.1007/s002640050083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mueller MJ, Maluf KS. Tissue adaptation to physical stress: A proposed “Physical Stress Theory” to guide physical therapist practice, education, and research. Physical Therapy. 2002;82:383–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neyret P, Robinson AHN, Le Coultre B, Lapra C, Chambat Patellar tendon length-The factor in patellar instability? The Knee. 2002;9:3–6. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0160(01)00136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfeiffer RP, DeBeliso M, Shea KG, Kelley L, Irmischer B, Harris C. Kinematic MRI assessment of McConnell taping before and after exercise. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2004;32:621–628. doi: 10.1177/0363546503261693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Powers CM. Rehabilitation of patellofemoral joint disorders: A critical review. The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 1998;28:345–354. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1998.28.5.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Powers CM, Ward SR, Chan L, Chen Y, Terk MR. The effect of bracing on patella alignment and patellofemoral joint contact area. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2004;36:1226–1232. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000132376.50984.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Powers CM, Ward SR, Chen Y, Chan L, Terk MR. The effect of bracing on patellofemoral joint stress during free and fast walking. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2004;32:224–231. doi: 10.1177/0363546503258908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Powers CM, Ward SR, Chen Y, Chan L, Terk MR. Effect of bracing on patellofemoral joint stress while ascending and descending stairs. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 2004;14:206–214. doi: 10.1097/00042752-200407000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seil R, Muller B, Georg T, Kohn D, Rupp S. Reliability and interobserver variability in radiological patellar height ratios. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2000;8:231–236. doi: 10.1007/s001670000121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shellock FG, Mink JH, Deutsch AL, Fox J, Molnar T, Kvitne R, Ferkel R. Effect of patellar realignment brace on patellofemoral relationships: Evaluation with kinematic MR imaging. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging. 1994;4:590–594. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880040413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simmons E, Cameron JC. Patella alta and recurrent dislocation of the patella. Clinical Orthopaedics. 1992;274:265–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ward SR, Powers CM. The influence of patella alta on patellofemoral joint stress during normal and fast walking. Clinical Biomechanics. 2004;19:1040–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ward SR, Terk MR, Powers CM. Influence of patella alta on knee extensor mechanics. Journal of Biomechanics. 2005;38:2415–2422. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ward SR, Terk MR, Powers CM. Patella alta: Association with patellofemoral alignment and changes in contact area during weightbearing. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2007;89:1749–1755. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]