Abstract

Several brain regions are thought to function as important sites of chemoreception including the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), medullary raphe and retrotrapezoid nucleus (RTN). In the RTN, mechanisms of chemoreception involve direct H+-mediated activation of chemosensitive neurons and indirect modulation of chemosensitive neurons by purinergic signalling. Evidence suggests that RTN astrocytes are the source of CO2-evoked ATP release. However, it is not clear whether purinergic signalling also influences CO2/H+ responsiveness of other putative chemoreceptors. The goals of this study are to determine if CO2/H+-sensitive neurons in the NTS and medullary raphe respond to ATP, and whether purinergic signalling in these regions influences CO2 responsiveness in vitro and in vivo. In brain slices, cell-attached recordings of membrane potential show that CO2/H+-sensitive NTS neurons are activated by focal ATP application; however, purinergic P2-receptor blockade did not affect their CO2/H+ responsiveness. CO2/H+-sensitive raphe neurons were unaffected by ATP or P2-receptor blockade. In vivo, ATP injection into the NTS increased cardiorespiratory activity; however, injection of a P2-receptor blocker into this region had no effect on baseline breathing or CO2/H+ responsiveness. Injections of ATP or a P2-receptor blocker into the medullary raphe had no effect on cardiorespiratory activity or the chemoreflex. As a positive control we confirmed that ATP injection into the RTN increased breathing and blood pressure by a P2-receptor-dependent mechanism. These results suggest that purinergic signalling is a unique feature of RTN chemoreception.

Introduction

Hypercapnic acidosis (i.e. high CO2/H+) provides the primary stimulus to breathe. Central respiratory chemoreceptors sense changes in tissue CO2/H+ and send excitatory drive to respiratory centres to directly regulate depth and frequency of breathing (Feldman et al. 2003; Huckstepp & Dale, 2011). The process of chemoreception is especially important during sleep and its disruption has been associated with central sleep apnoea (Dempsey et al. 2010) and hypoventilation syndrome (Guyenet & Mulkey, 2010). Nevertheless, despite the importance of central chemoreceptors the cellular and molecular mechanism(s) underlying this process have yet to be fully elucidated.

Several brain regions are thought to function as important sites of chemoreception including the caudal portion of the nucleus of the solitary tract (cNTS; Dean et al. 1990; Nattie & Li, 2002), medullary raphe (e.g. raphe pallidus, magnus and obscurus; Wang & Richerson, 1999; Nattie & Li, 2001; Hodges et al. 2004; Richerson, 2004) and retrotrapezoid nucleus (RTN; Li et al. 1999; Mulkey et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2013). Of these, the mechanism(s) of chemotransduction are best characterized at the level of the RTN where neurons have been shown to sense changes in CO2/H+ by two independent but coordinated mechanisms: direct H+-mediated activation of pH-sensitive neurons by inhibition of a resting K+ conductance (Mulkey et al. 2004, 2007) and indirect activation by purinergic signalling, most likely from CO2/H+-sensitive astrocytes (Gourine et al. 2010; Huckstepp et al. 2010; Wenker et al. 2010). Evidence also suggests that purinergic signalling is a unique feature of RTN chemotransduction. For example, it was shown in vivo that CO2/H+ facilitates ATP release only at discrete locations near the RTN (Gourine et al. 2005) and that RTN astrocytes, but not cortical astrocytes, respond to H+ with increased Ca2+-dependent exocytosis of ATP-containing vesicles (Kasymov et al. 2013). However, the role of purinergic signalling in putative chemoreceptor regions outside the RTN has not been thoroughly investigated.

Indeed, it remains possible that purinergic signalling also regulates neuronal activity in other putative chemosensitive regions. For example, P2 receptors are widely distributed throughout the central nervous system, including in the NTS and medullary raphe (Yao et al. 2000). In addition, injections of ATP into the cNTS increased breathing (Antunes et al. 2005b), whereas application of a P2-receptor blocker to the NTS blunted peripheral chemoreflex control of cardiorespiratory function (Paton et al. 2002; Braga et al. 2007). Furthermore, injection of ATP into the medullary raphe increased breathing (Cao & Song, 2007), whereas injection of a P2-receptor blocker into the rostral medullary raphe blunted the ventilatory response to CO2 of conscious rats (da Silva et al. 2012). These results suggest that purinergic signalling may contribute to the CO2/H+-dependent drive to breathe at other putative chemoreceptor regions. Therefore, the main goal of this study was to determine at the cellular and system levels whether purinergic signalling contributes to CO2/H+ sensitivity in the cNTS and medullary raphe.

To test this possibility, we recorded the activity of individual CO2/H+-sensitive neurons in putative chemosensitive regions in vitro, and phrenic nerve activity (PNA) in vivo during exposure to hypercapnia alone and in the presence of P2-receptor blockers. To determine if cells in the regions of interest functionally express P2 receptors, we also tested responsiveness to exogenous application of ATP in vivo and in vitro. We found in vitro that CO2/H+-sensitive neurons in the cNTS responded to focal ATP application with a ∼3-fold increase in firing rate, and in vivo unilateral ATP injection into this region elicited an increase in PNA frequency by 100%. Application of ATP into the medullary raphe had no effect on chemoreceptor activity or cardiorespiratory output. In addition, P2-receptor blockade in the cNTS and medullary raphe had no effect on the ventilatory response to CO2 in vivo, or the firing rate response to 15% CO2 in vitro. In conjunction with previous data that purinergic signalling is a critical component of RTN chemoreception, these results suggest that purinergic signalling is a unique feature of RTN chemoreception.

Methods

In vivo preparation

All in vivo experiments conformed to the guidelines approved by the University of São Paulo Animal Care and Use Committee and were performed in male Wistar rats weighing 250–280 g. Surgical procedures and experimental protocols were similar to those previously described (Wenker et al. 2012). Briefly, general anaesthesia was induced with 5% halothane in 100% O2. A tracheostomy was made and the halothane concentration was reduced to 1.4–1.5% until the end of surgery. The femoral artery was cannulated (polyethylene tubing, 0.6 mm o.d., 0.3 mm i.d., Scientific Commodities, Lake Havasu City, AZ, USA) for measurement of arterial pressure (AP). The femoral vein was cannulated for administration of fluids and drugs. The occipital plate was removed, and a micropipette was placed in the medulla oblongata via a dorsal transcerebellar approach for microinjection of drugs. A skin incision was made over the lower jaw for placement of a bipolar stimulating electrode, next to the mandibular branch of the facial nerve, as previously described (Wenker et al. 2012). The phrenic nerve was accessed by a dorsolateral approach after retraction of the right shoulder blade. To prevent any influence of artificial ventilation on phrenic nerve activity (PNA), the vagus nerve was cut bilaterally as previously described (Takakura & Moreira, 2011).

Upon completion of the surgical procedures, halothane was replaced by urethane (1.2 g kg−1) administered slowly i.v. All rats were ventilated with 100% O2 throughout the experiment. Rectal temperature was maintained at 37°C. End-tidal CO2 was monitored throughout each experiment with a capnometer (CWE, Inc., Ardmore, PA, USA) that was calibrated twice per experiment with a calibrated CO2/N2 mix. This instrument provided a reading of <0.1% CO2 during inspiration in animals breathing 100% O2 and provided an asymptotic, nearly horizontal reading during expiration. The adequacy of anaesthesia was monitored during a 20 min stabilization period by testing for the absence of withdrawal responses, pressor responses, and changes in PNA to a firm toe pinch. After these criteria were satisfied, the muscle relaxant pancuronium was administered at an initial dose of 1 mg kg−1 i.v. and the adequacy of the anaesthesia was thereafter gauged solely by the lack of increase in AP and PNA rate or amplitude to a firm toe pinch. Approximately hourly supplements of one-third of the initial dose of urethane were needed to satisfy these criteria throughout the recording period (2–3 h).

In vivo recordings of physiological variables

As previously described, mean arterial pressure (MAP), phrenic nerve activity (PNA), and end-expiratory CO2 (etCO2) were digitized with a micro1401 (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK), stored on a computer, and processed off-line with version 6 of Spike 2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design) (Takakura & Moreira, 2011). Integrated phrenic nerve activity (iPNA) was obtained after rectification and smoothing (τ = 0.015 s) of the original signal, which was acquired with a 30–300 Hz bandpass filter. PNA amplitude (PNA ampl) and PNA frequency (PNA freq) were normalized in each experiment by assigning to each of the two variables a value of 100 at saturation of the chemoreflex (high CO2) and a value of 0 to periods of apnoea.

Brain slice preparation

All procedures were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health and University of Connecticut Animal Care and Use Guidelines. Brainstem slices were prepared as previously described (Wenker et al. 2012). Briefly, neonatal rats (7–12 days postnatal) were decapitated under ketamine/xylazine anaesthesia and transverse brainstem slices (300 μm) containing the raphe pallidus (RPa) were cut using a microslicer (DSK 1500E; Dosaka, Kyoto, Japan) in ice-cold substituted Ringer solution containing (in mm): 260 sucrose, 3 KCl, 5 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, and 1 kynurenic acid. Slices were incubated for ∼30 min at 37°C and subsequently at room temperature in normal Ringer solution (in mm): 130 NaCl, 3 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, and 10 glucose. Both substituted and normal Ringer solutions were bubbled with 95% O2–5% CO2, extracellular pH (pHo = 7.35). It should be noted that slices containing the cNTS were prepared as described above but with two exceptions: (1) slices were cut in normal Ringer solution (not substituted Ringer solution); and (2) slices were incubated at room temperature (not 37°C) for 60 min or more. At the end of each in vivo experiment, rats were deeply anesthetized with halothane and perfused through the heart with PBS, pH 7.4, followed by paraformaldehyde (4% in 0.1 m phosphate buffer, pH 7.4). The brain of each animal was isolated and sectioned for later histological analysis of injection sites.

Slice-patch electrophysiology

Individual slices were transferred to a recording chamber mounted on a fixed-stage microscope (Zeiss Axioskop FS, Oberkochen, Germany) and perfused continuously (∼2 ml min−1) with a bath solution of normal Ringer solution (same as incubation Ringer solution above) bubbled with 95% O2–5% CO2 (pHo = 7.35). The pH of the bicarbonate-based bath solution was decreased to 6.90 by bubbling with 15% CO2. All recordings were made with an Axopatch 200B patch-clamp amplifier, digitized with a Digidata 1322A A/D converter, and recorded using pCLAMP 10.0 software (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA). Recordings were obtained at room temperature (∼22°C) with patch electrodes pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) on a two-stage puller (P89; Sutter Instrument Co., Novato, CA) to a DC resistance of 4–6 MΩ when filled with an internal solution containing the following (in mm): 120 KCH3SO3, 4 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.5 CaCl2, 10 Hepes, 10 EGTA, 3 Mg-ATP, 0.2% biocytin, and 0.3 GTP-Tris (pH 7.2); electrode tips were coated with Sylgard 184 (Dow Corning, Midland, MI). All recordings of neuronal firing rate were performed in the cell-attached configuration to ensure minimal alteration of the intracellular milieu. Firing rate histograms were generated by integrating action potential discharge in 10 s bins and plotted using Spike 5.0 software. Whole cell voltage clamp recordings (holding potential Vh = −60 mV, in tetrodotoxin to block action potentials) were made to verify the serotonergic phenotype of RPa neurons, i.e. medullary raphe neurons are known to exhibit a serotonin-activated inward potassium conductance (Bayliss et al. 1997).

Drugs

All drugs were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). For in vivo experiments, the non-specific P2 receptor antagonist pyridoxalphosphate-6-azophenyl-2′,4′-disulfonic acid (PPADS: 100 μm in sterile saline (pH 7.4)) or ATP (10 mm) were injected into the RTN using single-barrel glass pipettes (tip diameter of 25 μm) connected to a pressure injector (Picospritzer III, Parker Hannifin Corp., Cleveland, OH, USA). For each injection we delivered a volume of 50 nl over a period of 5 s. These glass pipettes also allowed recordings of field potential properties that were used to help direct the electrode tip to the desired site. Injections in the RTN region were guided by recordings of the facial field potential (Brown & Guyenet, 1985), and were placed 250 μm below the lower edge of the field, 1.7 mm lateral to the midline, and 200 μm rostral to the caudal end of the field. Recordings were made on one side only; the second injection was made 1–2 min later at the same level on the contralateral side. Injections into the medullary raphe were placed in the raphe pallidus (n = 6) and the parapyramidal region (n = 5) 150–200 μm below the lower edge of the field, 1.0 mm lateral to the midline, and 200 μm rostral to the caudal end of the field. Injections in the cNTS region were centred ∼400 μm caudal to the calamus scriptorius, in the midline and 300–500 μm below the dorsal surface of the brainstem. We included a 5% dilution of fluorescent latex microbeads (Lumafluor, New City, NY, USA) with all drug applications to mark the injection sites and to verify spread of the injections.

For in vitro experiments, we bath applied 100 μm of either suramin or PPADS to block P2 receptors. In addition, ATP (1 mm in Hepes-buffered medium, pH 7.3) was delivered focally using low-resistance pipettes connected to a Picospritzer III (Parker Instrumentation, Cleveland, OH, USA). Application times were 600 ms, and vehicle control experiments were performed to ensure agonist responses were not attributable to pressure artifacts.

Statistics

Data are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical analysis was performed using Sigma Stat version 3.0 software (Jandel Corporation, Point Richmond, CA, USA). A t test, paired t test or one-way ANOVA followed by the Newman–Keuls multiple comparisons test was performed as appropriate (P < 0.05).

Results

This study was composed of both in vitro and in vivo experiments. In the brain slice preparation, we investigated whether purinergic signalling could influence the basal activity or CO2/H+ sensitivity of putative chemoreceptors by testing the effects of focal ATP application on firing rate and bath application of a P2 receptor blocker (suramin or PPADS) on the CO2/H+ responsiveness of neurons in the cNTS and medullary raphe (see Supporting information Fig. S1 for approximate locations of CO2-sensitive neurons in these regions). To provide a functional basis for these results, we tested in vivo the effects of ATP and PPADS on baseline cardiorespiratory activity and CO2 responsiveness. As a positive control for ATP injections in the cNTS and raphe, we also tested the effects of focal ATP application into the RTN on breathing and blood pressure.

Purinergic signalling in the cNTS increases activity of chemosensitive neurons and respiratory activity but does not contribute to CO2/H+ responsiveness

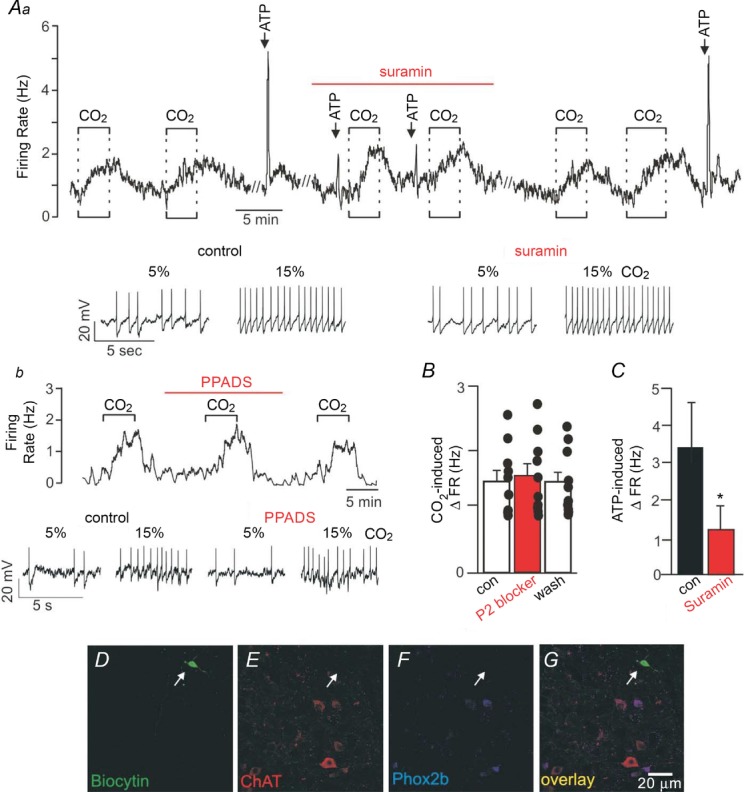

We recorded from CO2/H+-sensitive cNTS neurons in slices to characterize the effects of purinergic signalling on baseline activity and CO2/H+ responsiveness. As previously described (Nichols et al. 2009), a neuron was designated CO2/H+ sensitive if it was spontaneously active under control conditions (5% CO2) and responded to 15% CO2 with a ≥0.5 Hz increase in firing rate (this corresponds with a chemosensitivity index of ∼150%). We did not find any CO2-inhibited cells but this is not surprising considering that only a small minority of cells in this region have been shown to be inhibited by hypercapnia (Dean et al. 1990). The average firing rate of CO2/H+-sensitive cells was 0.50 ± 0.12 Hz (n = 10) under control conditions and 2.00 ± 0.24 Hz in 15% CO2 (i.e. CO2 increased activity by 1.48 ± 0.17 Hz; n = 10 cells from 9 animals; Fig. 1A and B). This level of CO2/H+ sensitivity is nearly identical to what has been described previously for cells in this region (Dean et al. 1990; Nichols et al. 2009) so we are confident that we were recording from the group of cells thought to function as chemoreceptors. To gain some insight into the neurochemical phenotype of CO2-sensitive cNTS neurons, we filled recorded cells with biocytin for subsequent immunohistochemical analysis using antibodies for the transcription factor Phox2b and choline acetyltransferase (ChAT; marker of cholinergic neurons). We found that 6 of 6 CO2-sensitive cNTS neurons were negative for Phox2b and ChAT (Fig. 1D–G).

Figure 1.

Aa, firing rate trace and segments of membrane potential from a cNTS neuron show that under control conditions exposure to 15% CO2 increased neuronal activity by ∼1 Hz in a reversible and repeatable manner. Under control conditions, focal application of ATP (1 mm) evoked a rapid and robust increase in firing rate of ∼4 Hz. Bath application of the P2-receptor blocker suramin (100 μm) had no effect on basal activity but significantly attenuated the firing rate response to ATP. In the continued presence of suramin additional bouts of 15% CO2 increased firing rate by an amount similar to under control conditions in the absence of suramin. Ab, firing rate trace and segments of membrane potential from a cNTS neuron show that the P2-receptor blocker PPADS (100 μm) also had no effect on baseline activity or CO2 responsiveness. B, summary data (n = 10 cells from 9 animals) show that P2-receptor blockers (suramin or PPADS) had no measurable effect on the CO2/H+ sensitivity of cNTS neurons. C, summary data (n = 5) confirm that suramin effectively blunted the ATP responsiveness of these neurons. *indicates different from control (P < 0.05). D–G, biocytin-labelled CO2/H+-sensitive cNTS neuron (D, arrow) is immuno-negative for choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) (E) and Phox2b (F). G shows merged images of the same cell as in D–F. Each image is the average projection of a confocal stack; around 30 images were taken every 0.26 μm in the Z plane. Scale bar is 20 μm.

To determine if purinergic signalling contributes to the activity of cNTS neurons, we first measured the firing rate response of CO2/H+-sensitive neurons in this region to focal application of ATP (1 mm in Hepes-buffered saline, pH 7.3). Under control conditions all cells tested exhibited a large reversible and repeatable increase in activity (increase of 3.39 ± 1.4 Hz; n = 6) in response to ATP (Fig. 1A and C). Bath application of suramin (100 μm) or PPADS (100 μm) had no discernible effect on baseline activity (firing rate under control conditions and during P2-receptor blockade was 0.50 ± 0.12 and 0.58 ± 0.11 Hz, respectively; n = 10 cells from 9 animals), suggesting that these cell do not receive purinergic drive under control conditions. As expected, suramin decreased the firing rate response to ATP by 67.0 ± 7.2%, thus confirming that P2 receptors are effectively blocked under these conditions. However, neither suramin (Fig. 1Aa) nor PPADS (Fig. 1Ab) blunted the firing rate response to CO2 (the CO2-induced change in firing rate under control conditions and during P2-receptor blockade was 1.48 ± 0.17 and 1.57 ± 0.20 Hz, respectively; n = 10 cells from 9 animals; Fig. 1B). These results indicate that CO2-sensitive cNTS neurons are activated directly or indirectly by purinergic signalling; however, this signalling mechanism does not contribute to the CO2 responsiveness of these cells in vitro.

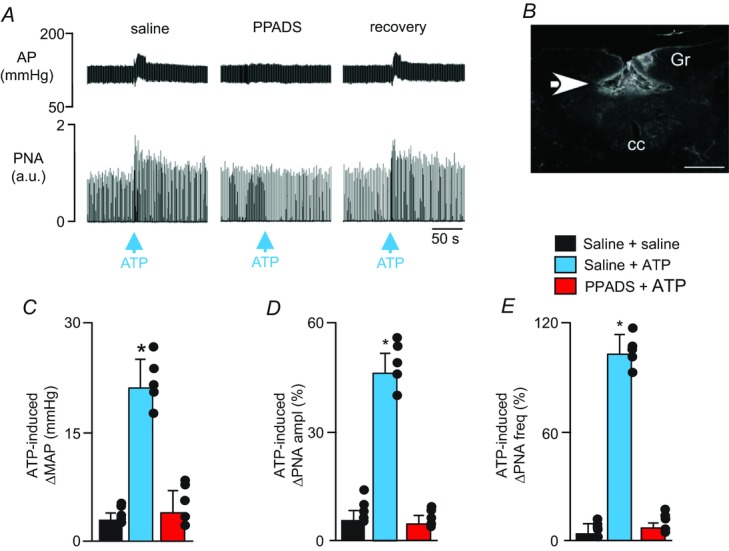

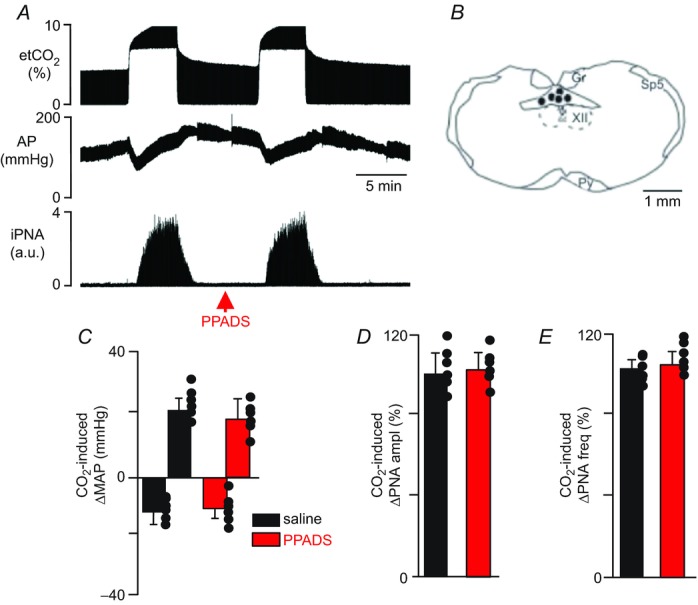

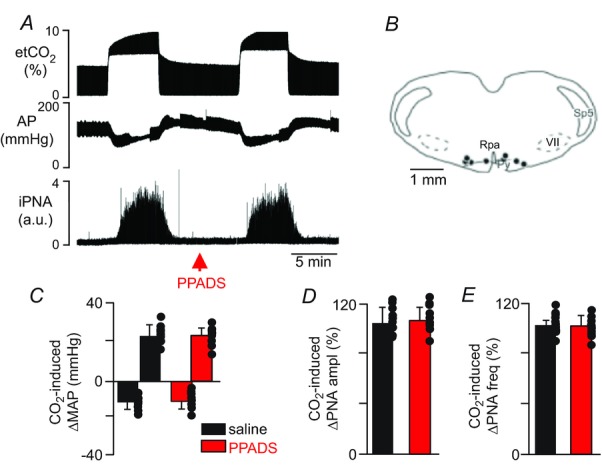

It is possible that endogenous purinergic drive to CO2/H+-sensitive cNTS neurons was disrupted in our in vitro preparation. Therefore, we also tested the effects of cNTS injections of ATP and a P2-receptor blocker (PPADS) on baseline breathing and the ventilatory response to CO2 in anaesthetized rats. Consistent with our slice data, we found that injection of ATP (10 mm, 50 nl) into the cNTS elicited an increase in phrenic nerve amplitude (PNA ampl) (46 ± 6% vs. saline: 6 ± 4%, P < 0.01) and frequency (PNA freq) (103 ± 11% vs. saline: 5 ± 5%, P < 0.0001). ATP injections into this region also increased MAP (21 ± 4 mmHg vs. saline: 3 ± 1 mmHg, P < 0.05; Fig. 2A and C–E). Also consistent with our slice data, bilateral injections of a P2-receptor blocker (PPADS; 3 mm, 50 nl; n = 6 animals per condition (saline or ATP)) into the cNTS did not change resting PNA (99 ± 7% of control, P > 0.05) or MAP (124 ± 5 mmHg vs. saline: 123 ± 7 mmHg, P > 0.05; Figs 2A and 3A). Furthermore, PPADS injections into the cNTS did not affect the cardiorespiratory response to CO2; exposure to 10% CO2 increased PNA amplitude (103 ± 9% vs. saline: 99 ± 13%, P > 0.05), PNA frequency (107 ± 6% vs. saline: 105 ± 4%, P > 0.05) and MAP (18 ± 7 mmHg vs. saline: 21 ± 4 mmHg, P > 0.05) (Fig. 3A–E).

Figure 2.

A, recordings of AP and PNA show that application of ATP (10 mm, 50 nl) into the cNTS increased breathing and blood pressure when preceded by injection of saline into this same region (i.e. control condition) but not after injection of PPADS into this region. Cardiorespiratory responses to ATP partly recovered after washing PPADS for ∼1 h. B, histology section showing the distribution of fluorescent microbeads within the cNTS. C–E, summary data (n = 5) show changes in mean arterial pressure (ΔMAP) (C), PNA amplitude (ΔPNA ampl) (D) and PNA frequency (ΔPNA freq) (E) elicited by injection of saline or PPADS + ATP into the cNTS. *indicates different from control (P < 0.05). Abbreviations: Gr, gracile nucleus; cc, central canal. Scale bar in A is 50 s and in B is 500 μm. a.u., arbitrary units.

Figure 3.

A, recordings of end-expiratory CO2 (etCO2), arterial pressure (AP) and integrated phrenic nerve activity (iPNA) show the pressure and ventilatory responses of a rat to hypercapnia under control conditions (i.e. after saline injection) and 5 min after PPADS (3 mm, 50 nl) was injected into the cNTS. B, computer-assisted plots of the centre of the injection sites revealed by the presence of fluorescent microbeads included in the injectate (coronal projection on plane bregma –14.3 mm; Paxinos & Watson, 1998). C–E, summary data (n = 6) show that cNTS injections of PPADS had no effect on CO2-induced changes in mean arterial pressure (ΔMAP) (C), PNA amplitude (ΔPNA ampl) (D) and PNA frequency (ΔPNA freq) (E). Abbreviations: Gr, gracile nucleus; Py, pyramids; Sp5, spinal trigeminal tract; XII, hypoglossal motor nucleus; cc, central canal. Black dots represent the injections sites in the cNTS. Scale bar in A is 5 min and in B is 1 mm.

For these experiments, injections of ATP or PPADS were centred about 400 μm caudal to the calamus scriptorius (Figs 2B and 3B). A single injection of ATP or PPADS was administered in or near the midline. Based on the distribution of the fluorescent microbeads (Fig. 2B), the injectate spread bilaterally ∼500 μm from the injection centre and ∼300 μm from the injection centre in the rostrocaudal direction.

Purinergic signalling in the medullary raphe does not modulate activity of CO2-sensitive neurons in vitro or contribute to the chemoreflex in vivo

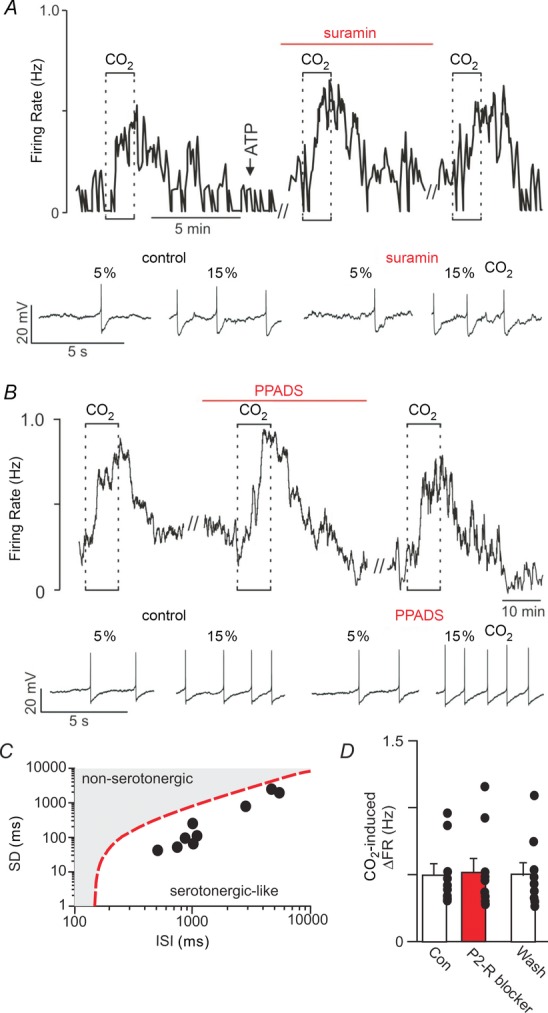

We recorded from CO2/H+-sensitive medullary raphe neurons in slices to characterize the effects of purinergic signalling on baseline activity and CO2 responsiveness. For these experiments we targeted the raphe pallidus at approximately the same rostrocaudal level as the RTN (−11.6 mm from bregma). Cells in this region were considered CO2/H+ sensitive (activated or inhibited) if they responded to 15% CO2 with ≥20% change in firing rate (this corresponds with a chemosensitivity index of ≥120% or ≤80%). This criteria is similar to previous definitions of raphe chemosensitivity (Richerson, 1995; Wang & Richerson, 1999). It should be noted that cells were presumed to be serotonergic based on (i) location, (ii) CO2/H+ sensitivity, (iii) stereotypic firing behaviour as evidenced by a low interspike interval (ISI) coefficient of variation (Mason, 1997), and in several cases (iv) expression of a characteristic serotonin-activated inward potassium conductance (Bayliss et al. 1997) measured in the whole cell voltage clamp configuration (data not shown). The majority of cells in this region did not respond to 15% CO2, as expected for raphe neurons in slices isolated from animals ≤12 days of age (Wang & Richerson, 1999). Raphe neurons that were stimulated by hypercapnia (n = 9 cells from 8 animals) had an average spontaneous discharge rate of 0. 84 ± 0.19 Hz in 5% CO2 that increased to 1.35 ± 0.24 Hz in 15% CO2 (Fig. 4A and B). Raphe neurons that were inhibited by hypercapnia (n = 3) had a spontaneous firing rate of 0.70 ± 0.13 in 5% CO2 that decreased to 0.28 ± 0.06 in 15% CO2 (Supporting information Fig. S2).

Figure 4.

A, trace of firing rate and segments of membrane potential from a CO2/H+-activated RPa neuron show that exposure to 15% CO2 increased firing rate ∼0.5 Hz under control conditions and when P2 receptors were blocked with suramin (100 μm). In addition, focal application of ATP (1 mm) had no effect on neuronal activity (arrow). B, firing rate trace and segments of membrane potential show that PPADS (100 μm) also did not affect CO2 responsivness of this CO2/H+-activated RPa neuron. C, to confirm that all CO2/H+-activated raphe neurons were serotonergic-like we analysed the interspike interval (ISI) using a linear discriminant function (y(ISI, standard deviation) = 146 – ISI + 0.98SD) as previously described (Mason, 1997). C shows a log–log plot of the mean interspike interval vs. the SD of the interspike interval for all CO2-activated RPa neurons used in this study. The discriminant line (dotted line) occurs when the equation is set equal to zero and reportedly defines the optimal linear boundary between serotonergic and non-serotonergic cell types (Mason, 1997). All raphe neurons used in this study had negative discriminant scores, thus predicting that they are serotonergic. D, summary data (n = 9) shows that P2-receptor blockade with suramin or PPADS had no effect on the CO2/H+-activated RPa neurons. //designates 10 min time breaks where data is not shown.

To determine if purinergic signalling contributes to the activity of these cells, we next measured the CO2/H+ responsiveness of raphe pallidus neurons when P2 receptors are blocked with suramin or PPADS. Bath application of either suramin (100 μm) or PPADS (100 μm) had no measurable effect on the baseline activity or CO2/H+ sensitivity of these cells. For example, during P2 receptor blockade CO2/H+-activated cells responded to hypercapnia with an increase in firing rate from 0.96 ± 0.25 Hz to 1.49 ± 0.33 Hz (n = 9 cells from 8 animals; Fig. 4A, B and D). This response corresponds to an activity increase of 0.53 ± 0.10 Hz which is not significantly different from the CO2/H+-induced increase under control conditions (0.51 ± 0.08). We were not able to successfully recover recorded cells for immunohistochemical characterization, therefore to identify CO2-activated cells as serotonergic-like we used a linear discriminant function to analyse interspike interval (ISI) as previously described (Mason, 1997); serotonergic cells fire in a highly stereotypic manner and so have a low ISI coefficient of variation (ISICV) and negative discriminant score compared to non-serotonergic cells which have a higher ISICV and positive discriminant score (Mason, 1997). We found that CO2-activated raphe neurons had an average ISICV of 0.22 ± 0.2 and all cells had negative discriminant scores that ranged from −312 to −1817, i.e., these data points appear below the discriminant line shown in Fig. 4C. These results confirm that all nine raphe cells are serotonergic-like. We also found that in the presence of suramin CO2/H+-inhibited raphe neurons respond to 15% CO2 with a decrease in firing rate from 0.76 ± 0.12 Hz to 0.39 ± 0.12 Hz (Supporting information Fig. S2). This corresponds to a 0.39 ± 0.12 Hz decrease in activity which is similar to CO2/H+-mediated inhibition under control conditions (Supporting information Fig. S2). Furthermore, in a separate series of experiments, we found that 11 (7 CO2/H+-activated and 6 CO2/H+-inhibited) of 13 CO2/H+-sensitive raphe pallidus neurons showed no measurable response to focal application of ATP (1 mm in Hepes-buffered saline, pH 7.3; Fig. 4A and C). Two raphe neurons (one CO2-activated and one CO2-inhibited) responded to ATP with an increase in firing rate (data not shown). Together, these results indicate that purinergic signalling does not contribute to CO2/H+ sensing by raphe pallidus neurons in vitro.

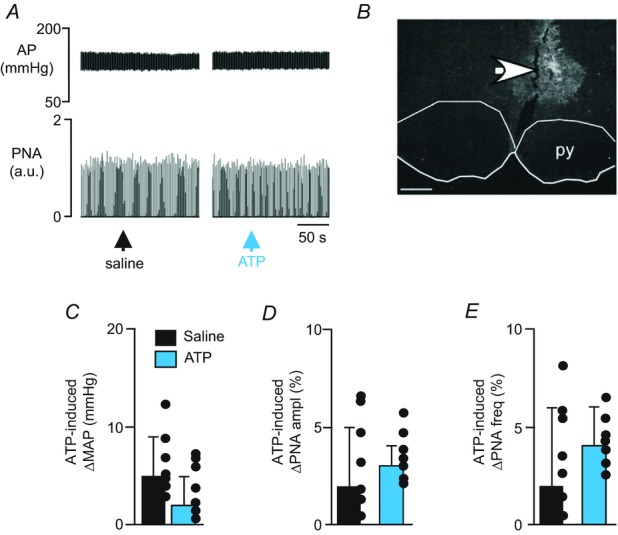

To determine if purinergic signalling in the medullary raphe contributes to the chemoreflex, we tested the effects of medullary raphe injections of ATP and PPADS on baseline breathing and the ventilatory response to CO2 in urethane-anaesthetized rats. For these experiments, we targeted the raphe pallidus (RPa; n = 6) and the parapyramidal region (Ppy) (n = 5) because serotonergic cells in these regions reportedly function as chemoreceptors (Richerson, 2004) and are thought to be located within diffusion distance (estimated to be ∼400 μm from the ventral surface; Spyer & Gourine, 2009) from sites of CO2/H+-evoked ATP release on the ventral surface. Injections of PPADS were placed bilaterally in the medullary raphe in these rats (Fig. 5B). The injection centre was 200–230 μm below the facial motor nucleus, 200 μm rostral to the caudal end of this nucleus and 1 mm lateral to the midline as previously demonstrated (Mulkey et al. 2004; Takakura & Moreira, 2013; Fig. 5B). Consistent with our in vitro data, we found that bilateral injections of PPADS (3 mm, 50 nl) into either the RPa or Ppy had no effect on baseline PNA or the ventilatory response to CO2. For example, bilateral injections of PPADS (3 mm, 50 nl; n = 8 per group) into the medullary raphe did not change resting PNA or resting MAP (Fig. 5A). In addition, bilateral injections of PPADS into the medullary raphe did not affect the hypercapnia-induced increase in PNA amplitude (106 ± 11% vs. saline: 105 ± 14%, P > 0.05), PNA frequency (102 ± 8% vs. saline: 101 ± 5%, P > 0.05) and MAP (22 ± 4 mmHg vs. saline: 22 ± 6 mmHg, P > 0.05; Fig. 5A and C–E). Also consistent with our slice data, we found that injections of ATP (10 mm, 50 nl) into the medullary raphe had no effect on PNA ampl, PNA freq or blood pressure (Fig. 6A–E).

Figure 5.

A, recordings from one rat show effects of injection of PPADS into the RPa/Ppy on changes in phrenic nerve activity (PNA) elicited by an increase of end-expiratory CO2 from 5 to 10%. Responses were recorded 5 min after injection of saline (50 nl) or PPADS (3 mm, 50 nl) into the RPa/Ppy. B, computer-assisted plot shows the centre of the injection sites (coronal projection on plane bregma −11.6 mm; Paxinos & Watson, 1998). C–E, summary data (n = 11) show that PPADS injection into the RPa/Ppy had no effect on CO2-induced changes in mean arterial pressure (ΔMAP) (C), PNA amplitude (ΔPNA ampl) (D) or PNA frequency (ΔPNA freq) (E). Abbreviations: py, pyramid; RPa, raphe pallidus; Sp5, spinal trigeminal tract; VII, facial motor nucleus. Black dots represent the injections sites in the RPa/Ppy. Scale bar in A is 5 min and in B is 1 mm.

Figure 6.

A, recordings of AP and PNA show that application of ATP (10 mm, 50 nl) into the medullary raphe (RPa/Ppy) did not affect blood pressure or respiratory motor output. B, histology section showing the distribution of fluorescent microbeads within the RPa. C–E, summary data (n = 7) show that RPa/Ppy injections of ATP had no effect on mean arterial pressure (ΔMAP) (C), PNA amplitude (ΔPNA ampl) (D) or PNA frequency (ΔPNA freq) (E). Scale bar in A is 50 s and in B is 50 μm.

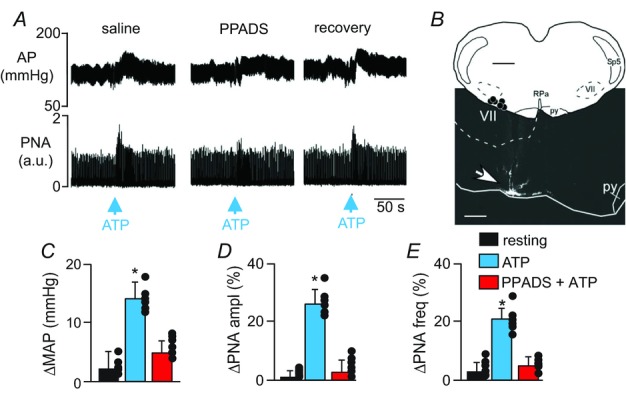

Application of ATP into the RTN increases cardiorespiratory activity

There is strong evidence that purinergic signalling contributes to RTN chemoreception (Gourine et al. 2005, 2010; Mulkey et al. 2006; Huckstepp et al. 2010; Wenker et al. 2010, 2012). We confirm this possibility by testing the effects of unilateral injections of ATP into the RTN on cardiorespiratory activity. These experiments also serve as a positive control for similar experiments in the commissural NTS (cNTS) and medullary raphe (described above). Consistent with previous evidence (Gourine et al. 2005; Mulkey et al. 2006), we found that unilateral injection of ATP into the RTN increased MAP (14 ± 3 mmHg vs. saline: 2 ± 3 mmHg, P < 0.05), PNA amplitude by 26 ± 5% and PNA frequency by 21 ± 4% (Fig. 7A–E). The cardiorespiratory responses elicited by ATP were eliminated by previous injections of PPADS within the RTN (Fig. 7A–E). These results confirm that purinergic signalling at the level of the RTN regulates cardiorespiratory activity.

Figure 7.

A, recordings of arterial pressure (AP) and phrenic nerve activity (PNA) show that under control conditions unilateral injection of ATP (10 mm, 50 nl) into the RTN increased breathing and blood pressure. Injection of PPADS (3 mm, 50 nl) into the RTN blocked cardiorespiratory responses to subsequent applications of ATP. B, computer-assisted plot and representative histological section show centre of injection sites (coronal projection on plane bregma –11.6 mm; Paxinos & Watson, 1998). C–E, summary data (n = 6) show changes in mean arterial pressure (ΔMAP) (C), PNA amplitude (ΔPNA ampl) (D) and PNA frequency (ΔPNA freq) (E) elicited by injection of saline or ATP into the RTN. *indicates different from control (P < 0.05). Abbreviations: py, pyramid; RPa, raphe pallidus; Sp5, spinal trigeminal tract; VII, facial motor nucleus. Black dots represent the injections sites in the RPa/Ppy. Scale bar in A is 50 s and top and bottom scale bars in B are 1 mm and 300 μm, respectively.

Discussion

There is compelling evidence that CO2/H+-evoked ATP release from ventral surface astrocytes contributes to respiratory drive by activating chemosensitive RTN neurons (Gourine et al. 2005; Huckstepp et al. 2010; Wenker et al. 2012). Here, we confirm that activation of P2 receptors in the RTN increases cardiorespiratory activity, and we test at the cellular and systems level whether purinergic signalling also modulates the activity or CO2/H+ sensitivity of neurons in two other brainstem regions thought to contribute to central chemoreception (i.e. the cNTS and medullary raphe). As expected, application of ATP into the RTN elicited a strong increase in breathing and a mild increase in blood pressure by a P2-receptor-dependent mechanism, thus further supporting the possibility that purinergic signalling in the ventrolateral medulla can modulate the activity of respiratory chemoreceptors (Thomas & Spyer, 2000; Gourine et al. 2005; Huckstepp et al. 2010; Wenker et al. 2012) and blood pressure-regulating C1 cells (Wenker et al. 2013). Similar to previous evidence in the RTN, CO2/H+-sensitive cNTS neurons also respond to focal ATP application with a robust increase in firing rate, and in vivo ATP injection into the cNTS increased breathing. Conversely, CO2/H+-sensitive medullary raphe neurons did not respond to ATP nor did injection of ATP into this region elicit a cardiorespiratory response. Contrary to evidence in the RTN, inhibition of P2 receptors in the cNTS and medullary raphe had no effect on basal activity and CO2/H+ sensitivity in vitro, or baseline cardiorespiratory activity and CO2 responsiveness in vivo. Therefore, previous and present results suggest that purinergic signalling is a unique feature of RTN chemoreception.

Experimental limitations

Our in vivo experiments were performed in anaesthetized rats and it is possible that anaesthetics modify centrally mediated cardiorespiratory reflexes. Therefore, it will be important for future studies to confirm the role of purinergic signalling in central chemoreception using conscious animals. In addition, different age ranges were used for in vitro (7-to 12-day-old pups) and in vivo (adult rats) experiments; however, we consider this a minor issue since the extent to which purinergic signalling contributes to chemoreception at the level of the RTN was very similar between preparations (Wenker et al. 2012). Another limitation of this study is that we did not assess astrocyte function directly using Ca2+ imaging so we are unable to provide insight into mechanisms underlying the differential role of purinergic signalling in RTN chemoreception. However, previous studies have shown that RTN astrocytes, but not cortical or NTS astrocytes, respond to H+ with an increase in intracellular Ca2+ (Kasymov et al. 2013), therefore it is possible that RTN astrocytes are functionally specialized to sense and respond to changes in CO2/H+.

The RTN is an important site of chemoreception and intense effort has been made to identify a unique CO2/H+-sensing mechanism in this region. Evidence indicates that chemosensitive RTN neurons sense and respond to changes in tissue CO2/H+ directly (Lazarenko et al. 2009; Onimaru et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2013), in part by H+-mediated inhibition of TASK–2 channels (Wang et al. 2013), and indirectly by CO2/H+-evoked ATP release, most likely from astrocytes (Gourine et al. 2005, 2010; Huckstepp et al. 2010; Wenker et al. 2010, 2012). Evidence also suggests that a subset of RTN astrocytes are uniquely specialized to release ATP in a CO2/H+-dependent manner. For example, CO2/H+-evoked ATP release has been shown to occur at discrete regions on the ventral surface near the RTN but not in deeper brainstem regions or near the dorsal surface (Gourine et al. 2005; Huckstepp et al. 2010). In addition, evidence suggests that a subset of ventral surface astrocytes but not cortical or NTS astrocytes respond to H+ with an increase in intracellular Ca2+ and vesicular release of ATP (Kasymov et al. 2013). The results presented here build on the possibility that purinergic signalling is a unique component of RTN chemoreception by showing that P2-receptor blockade in two putative chemoreceptor regions did not affect CO2 responsiveness in vitro or in vivo.

The caudal portion of the NTS is thought to contribute to central chemoreception because a subset of neurons in this region respond to CO2 with increased firing rate (Dean et al. 1990; Nichols et al. 2009) and focal acidification of this region has been shown to stimulate breathing in anaesthetized (Coates et al. 1993) and unanaesthetized animals (Nattie & Li, 2002). Although the cellular and molecular identity of CO2/H+ sensors in the cNTS are unknown, it is well established that cells in this region, including Phox2b immunoreactive neurons (Stornetta et al. 2006), relay peripheral chemosensory inputs to other components of the respiratory circuit; thus cells in this area are well positioned to regulate cardiorespiratory activity in response to hypercapnia.

Previous evidence suggests that purinergic signalling in the cNTS influences cardiorespiratory activity. For example, several types of P2 receptors are expressed in the cNTS (Yao et al. 2000) and injection of ATP or related analogues into the cNTS of awake rats mimicked cardiorespiratory responses (i.e. bradycardia, hypertension and tachypnoea) to peripheral chemoreceptor activation (Paton et al. 2002; de Paula et al. 2004; Antunes et al. 2005a). Purinergic signalling also contributes to pulmonary stretch receptor-mediated activation of second-order relay neurons in the NTS to control inspiration (Gourine et al. 2008). Consistent with the possibility that purinergic signalling in the cNTS contributes to cardiorespiratory control, we show that ATP injections into this region increased cardiorespiratory activity. We also show that CO2/H+-sensitive cNTS neurons are strongly activated by focal ATP application. It should be noted that the neurochemical phenotype of CO2/H+-sensitive cNTS neurons remains unknown, since these cells were immuno-negative for Phox2b and ChAT. Nevertheless, blocking P2 receptors in this region did not affect the firing rate response to CO2/H+ in vitro, or the ventilatory response to CO2 in vivo. These results indicate that purinergic signalling can increase the activity of CO2/H+-sensitive cNTS neurons and stimulate cardiorespiratory activity, but this mechanism does not contribute to CO2 responsiveness. It remains possible that astrocytes in this region contribute to the CO2/H+ responsiveness of cNTS neurons, albeit by an ATP-independent mechanism. For example, recent evidence showed that acidification decreased glutamate uptake by NTS astrocytes and facilitated glutamatergic slow excitatory potentials that could potentially increase integrated output of the NTS to the rest of the respiratory network (Huda et al. 2013).

Serotonergic medullary raphe neurons can strongly influence breathing (Hodges & Richerson, 2010) and are thought to function as respiratory chemoreceptors in part because neurons in this area have been shown to be acid sensitive in vitro (Richerson, 1995, 2004; Wang & Richerson, 1999; Wang et al. 2001), focal acidification of this region increased breathing in unanaesthetized awake (Hodges et al. 2004) or sleeping (Nattie & Li, 2001) animals, and genetic deletion (Hodges et al. 2008) or selective inhibition (Ray et al. 2011) of serotonergic neurons decreased the ventilatory response to CO2. As previously described (Richerson, 1995; Wang & Richerson, 1999), we found a subset of medullary raphe neurons in slices from neonatal rat pups that responded to 15% CO2 with a modest increase or decrease of firing rate.

There is some evidence that CO2/H+ sensitivity of raphe neurons is partially dependent on purinergic signalling. For example, a study in anaesthetized rats showed that microinjection of ATP into the raphe magnus and pallidus decreased or increased respiratory activity, respectively (Cao & Song, 2007). In addition, injection of PPADS into the medullary raphe blunted the ventilatory response to CO2 of conscious rats (da Silva et al. 2012). Considering that P2 receptors are ubiquitously expressed in the central nervous system, including at the level of the medullary raphe (Yao et al. 2000), we were surprised to find that CO2/H+-sensitive neurons (i.e. activated or inhibited) in the raphe pallidus did not respond to focal application of ATP in vitro, and injection of ATP into the raphe pallidus or the parapyramidal region had no effect on baseline breathing in vivo. In addition, blocking P2 receptors in these medullary raphe regions did not perturb CO2 sensitivity in vitro or in vivo. These results suggest that purinergic signalling does not influence activity or CO2 sensitivity at these raphe nuclei under our experimental conditions.

In summary, purinergic signalling contributes to the mechanism by which RTN neurons sense and respond to changes in CO2/H+; however, this signalling mechanism is not essential for CO2/H+ sensing in the cNTS or medullary raphe. These results are the first evidence for a unique CO2/H+-sensing mechanism in the RTN.

Key points

Several brain regions are thought to sense changes in tissue CO2/H+ to regulate breathing (i.e. central chemoreceptors) including the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), medullary raphe and retrotrapezoid nucleus (RTN).

Mechanism(s) underlying RTN chemoreception involve direct activation of RTN neurons by H+-mediated inhibition of a resting K+ conductance and indirect activation of RTN neurons by purinergic signalling, most likely from CO2/H+-sensitive astrocytes.

Here, we confirm that activation of P2 receptors in the RTN stimulates cardiorespiratory activity, and we show at the cellular and systems level that purinergic signalling is not essential for CO2/H+ sensing in the NTS or medullary raphe.

These results support the possibility that purinergic signalling is a unique feature of RTN chemoreception.

Acknowledgments

None Declared.

Glossary

- AP

arterial pressure

- ChAT

choline acetyltransferase

- cNTS

caudal portion of the nucleus of the solitary tract

- cNTS

commissural NTS

- etCO2

end-expiratory CO2

- iPNA

integrated phrenic nerve activity

- ISI

interspike interval

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- NTS

nucleus of the solitary tract

- PNA

phrenic nerve activity

- Ppy

parapyramidal region

- RPa

raphe pallidus

- RTN

retrotrapezoid nucleus.

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Author contributions

All in vitro experiments were performed at the University of Connecticut and all in vivo experiments were perforemd at the University of Sao Paulo C.R.S: collection and analysis of in vivo data; revising the manuscript; final approval of the manuscript. I.C.W.: experimental design; collection and analysis of in vitro data; revising the manuscript; final approval of the manuscript. E.M.P.: collection and analysis of in vitro data; revising the manuscript; final approval of the manuscript. A.C.T.: experimental design; collection and analysis of in vivo data; revising the manuscript; final approval of the manuscript. T.S.M.: experimental design; collection, analysis and interpretation of in vivo data; revising the manuscript; final approval of the manuscript. D.K.M.: experimental design; data analysis; drafting the manuscript; revising the manuscript; final approval of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant HL104101 (D.K.M.), American Heart Association grant 11PRE7580037 (I.C.W.), and the National Science Foundation Grant DBI 1262926 (E.M.P.). This work was also supported by public funding from São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) grants 10/19336-0 (T.S.M.), 10/09776-3 (A.C.T.) and 11/13462-7 (C.R.S.).

References

- Antunes VR, Bonagamba LG, Machado BH. Hemodynamic and respiratory responses to microinjection of ATP into the intermediate and caudal NTS of awake rats. Brain Res. 2005a;1032:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antunes VR, Braga VA, Machado BH. Autonomic and respiratory responses to microinjection of ATP into the intermediate or caudal nucleus tractus solitarius in the working heart-brainstem preparation of the rat. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2005b;32:467–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2005.04213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss DA, Li YW, Talley EM. Effects of serotonin on caudal raphe neurons: activation of an inwardly rectifying potassium conductance. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:1349–1361. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.3.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braga VA, Soriano RN, Braccialli AL, de Paula PM, Bonagamba LG, Paton JF, Machado BH. Involvement of l–glutamate and ATP in the neurotransmission of the sympathoexcitatory component of the chemoreflex in the commissural nucleus tractus solitarii of awake rats and in the working heart–brainstem preparation. J Physiol. 2007;581:1129–1145. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.129031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DL, Guyenet PG. Electrophysiological study of cardiovascular neurons in the rostral ventrolateral medulla in rats. Circ Res. 1985;56:359–369. doi: 10.1161/01.res.56.3.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Song G. Purinergic modulation of respiration via medullary raphe nuclei in rats. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2007;155:114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates EL, Li A, Nattie EE. Widespread sites of brain stem ventilatory chemoreceptors. J Appl Physiol. 1993;75:5–14. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva GS, Moraes DJ, Giusti H, Dias MB, Glass ML. Purinergic transmission in the rostral but not caudal medullary raphe contributes to the hypercapnia-induced ventilatory response in unanesthetized rats. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2012;184:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2012.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean JB, Bayliss DA, Erickson JT, Lawing WL, Millhorn DE. Depolarization and stimulation of neurons in nucleus tractus solitarii by carbon dioxide does not require chemical synaptic input. Neuroscience. 1990;36:207–216. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90363-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey JA, Veasey SC, Morgan BJ, O'Donnell CP. Pathophysiology of sleep apnea. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:47–112. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Paula PM, Antunes VR, Bonagamba LG, Machado BH. Cardiovascular responses to microinjection of ATP into the nucleus tractus solitarii of awake rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287:R1164–R1171. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00722.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman JL, Mitchell GS, Nattie EE. Breathing: rhythmicity, plasticity, chemosensitivity. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2003;26:239–266. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourine AV, Dale N, Korsak A, Llaudet E, Tian F, Huckstepp R, Spyer KM. Release of ATP and glutamate in the nucleus tractus solitarii mediate pulmonary stretch receptor (Breuer–Hering) reflex pathway. J Physiol. 2008;586:3963–3978. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.154567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourine AV, Kasymov V, Marina N, Tang F, Figueiredo MF, Lane S, Teschemacher AG, Spyer KM, Deisseroth K, Kasparov S. Astrocytes control breathing through pH-dependent release of ATP. Science. 2010;329:571–575. doi: 10.1126/science.1190721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourine AV, Llaudet E, Dale N, Spyer KM. ATP is a mediator of chemosensory transduction in the central nervous system. Nature. 2005;436:108–111. doi: 10.1038/nature03690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyenet PG, Mulkey DK. Retrotrapezoid nucleus and parafacial respiratory group. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2010;173:244–255. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges MR, Klum L, Leekley T, Brozoski DT, Bastasic J, Davis S, Wenninger JM, Feroah TR, Pan LG, Forster HV. Effects on breathing in awake and sleeping goats of focal acidosis in the medullary raphe. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:1815–1824. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00992.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges MR, Richerson GB. The role of medullary serotonin (5–HT) neurons in respiratory control: contributions to eupneic ventilation, CO2 chemoreception, and thermoregulation. J Appl Physiol. 2010;108:1425–1432. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01270.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges MR, Tattersall GJ, Harris MB, McEvoy SD, Richerson DN, Deneris ES, Johnson RL, Chen ZF, Richerson GB. Defects in breathing and thermoregulation in mice with near-complete absence of central serotonin neurons. J Neurosci. 2008;28:2495–2505. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4729-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huckstepp RT, id Bihi R, Eason R, Spyer KM, Dicke N, Willecke K, Marina N, Gourine AV, Dale N. Connexin hemichannel-mediated CO2-dependent release of ATP in the medulla oblongata contributes to central respiratory chemosensitivity. J Physiol. 2010;588:3901–3920. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.192088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huckstepp RT, Dale N. Redefining the components of central CO2 chemosensitivity – towards a better understanding of mechanism. J Physiol. 2011;589:5561–5579. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.214759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huda R, McCrimmon DR, Martina M. pH modulation of glial glutamate transporters regulates synaptic transmission in the nucleus of the solitary tract. J Neurophysiol. 2013;110:368–377. doi: 10.1152/jn.01074.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasymov V, Larina O, Castaldo C, Marina N, Patrushev M, Kasparov S, Gourine AV. Differential sensitivity of brainstem versus cortical astrocytes to changes in pH reveals functional regional specialization of astroglia. J Neurosci. 2013;33:435–441. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2813-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarenko RM, Milner TA, Depuy SD, Stornetta RL, West GH, Kievits JA, Bayliss DA, Guyenet PG. Acid sensitivity and ultrastructure of the retrotrapezoid nucleus in Phox2b-EGFP transgenic mice. J Comp Neurol. 2009;517:69–86. doi: 10.1002/cne.22136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A, Randall M, Nattie EE. CO2 microdialysis in retrotrapezoid nucleus of the rat increases breathing in wakefulness but not in sleep. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:910–919. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.3.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason P. Physiological identification of pontomedullary serotonergic neurons in the rat. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:1087–1098. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.3.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulkey DK, Mistry AM, Guyenet PG, Bayliss DA. Purinergic P2 receptors modulate excitability but do not mediate pH sensitivity of RTN respiratory chemoreceptors. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7230–7233. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1696-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulkey DK, Stornetta RL, Weston MC, Simmons JR, Parker A, Bayliss DA, Guyenet PG. Respiratory control by ventral surface chemoreceptor neurons in rats. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:1360–1369. doi: 10.1038/nn1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulkey DK, Talley EM, Stornetta RL, Siegel AR, West GH, Chen X, Sen N, Mistry AM, Guyenet PG, Bayliss DA. TASK channels determine pH sensitivity in select respiratory neurons but do not contribute to central respiratory chemosensitivity. J Neurosci. 2007;27:14049–14058. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4254-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nattie EE, Li A. CO2 dialysis in the medullary raphe of the rat increases ventilation in sleep. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:1247–1257. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.4.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nattie EE, Li A. CO2 dialysis in nucleus tractus solitarius region of rat increases ventilation in sleep and wakefulness. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:2119–2130. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01128.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols NL, Mulkey DK, Wilkinson KA, Powell FL, Dean JB, Putnam RW. Characterization of the chemosensitive response of individual solitary complex neurons from adult rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R763–R773. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90769.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onimaru H, Ikeda K, Kawakami K. Postsynaptic mechanisms of CO2 responses in parafacial respiratory neurons of newborn rats. J Physiol. 2012;590:1615–1624. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.222687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton JF, de Paula PM, Spyer KM, Machado BH, Boscan P. Sensory afferent selective role of P2 receptors in the nucleus tractus solitarii for mediating the cardiac component of the peripheral chemoreceptor reflex in rats. J Physiol. 2002;543:995–1005. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.021923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. San Diego: Academic Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ray RS, Corcoran AE, Brust RD, Kim JC, Richerson GB, Nattie E, Dymecki SM. Impaired respiratory and body temperature control upon acute serotonergic neuron inhibition. Science. 2011;333:637–642. doi: 10.1126/science.1205295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richerson GB. Response to CO2 of neurons in the rostral ventral medulla in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 1995;73:933–944. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.3.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richerson GB. Serotonergic neurons as carbon dioxide sensors that maintain pH homeostasis. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:449–461. doi: 10.1038/nrn1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spyer KM, Gourine AV. Chemosensory pathways in the brainstem controlling cardiorespiratory activity. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009;364:2603–2610. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stornetta RL, Moreira TS, Takakura AC, Kang BJ, Chang DA, West GH, Brunet JF, Mulkey DK, Bayliss DA, Guyenet PG. Expression of Phox2b by brainstem neurons involved in chemosensory integration in the adult rat. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10305–10314. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2917-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takakura AC, Moreira TS. Contribution of excitatory amino acid receptors of the retrotrapezoid nucleus to the sympathetic chemoreflex in rats. Exp Physiol. 2011;96:989–999. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2011.058842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takakura AC, Moreira TS. Arterial chemoreceptor activation reduces the activity of parapyramidal serotonergic neurons in rats. Neuroscience. 2013;237:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.01.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas T, Spyer KM. ATP as a mediator of mammalian central CO2 chemoreception. J Physiol. 2000;523:441–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Shi Y, Shu S, Guyenet PG, Bayliss DA. Phox2b-expressing retrotrapezoid neurons are intrinsically responsive to H+ and CO2. J Neurosci. 2013;33:7756–7761. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5550-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Richerson GB. Development of chemosensitivity of rat medullary raphe neurons. Neuroscience. 1999;90:1001–1011. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00505-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Tiwari JK, Bradley SR, Zaykin RV, Richerson GB. Acidosis-stimulated neurons of the medullary raphe are serotonergic. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:2224–2235. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.5.2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenker IC, Kreneisz O, Nishiyama A, Mulkey DK. Astrocytes in the retrotrapezoid nucleus sense H+ by inhibition of a Kir4.1-Kir5.1-like current and may contribute to chemoreception by a purinergic mechanism. J Neurophysiol. 2010;104:3042–3052. doi: 10.1152/jn.00544.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenker IC, Sobrinho CR, Takakura AC, Moreira TS, Mulkey DK. Regulation of ventral surface CO2/H+-sensitive neurons by purinergic signalling. J Physiol. 2012;590:2137–2150. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.229666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenker IC, Sobrinho CR, Takakura AC, Mulkey DK, Moreira TS. P2Y1 receptors expressed by C1 neurons determine peripheral chemoreceptor modulation of breathing, sympathetic activity, and blood pressure. Hypertension. 2013;62:263–273. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao ST, Barden JA, Finkelstein DI, Bennett MR, Lawrence AJ. Comparative study on the distribution patterns of P2X1–P2X6 receptor immunoreactivity in the brainstem of the rat and the common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus): Association with catecholamine cell groups. J Comp Neurol. 2000;427:485–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.