Abstract

Background

Over the last decade, South Africa’s Western Cape has experienced a dramatic increase in methamphetamine (“tik”) use. Our study explored local impressions of the impact of tik use in a peri-urban township community in Cape Town, South Africa.

Methods

We conducted individual in-depth interviews with 55 women and 37 men who were regular attendees of alcohol-serving venues. Interviews were recorded and transcribed. A content analysis approach was used to identify themes related to the impact of tik use based on levels of the socio-ecological framework (individual, inter-personal and community).

Results

Tik use was reported to be a greater issue among Coloureds, compared to Blacks. At an individual level, respondents reported that tik use had adverse effects on mental, physical, and economic well-being, and limited future opportunities through school drop-out and incarceration. At an inter-personal level, respondents reported that tik use contributed to physical and sexual violence as well as increased rates of sexual risk behaviour, particularly through transactional sex relationships. Respondents described how tik use led to household conflict, and had negative impacts on children, including neglect and poor birth outcomes. At a community level, respondents linked tik use to increased rates of crime, violence and corruption, which undercut community cohesion.

Conclusions

Our results highlight the negative impact that tik is having on individuals, households and the overall community in a peri-urban setting in South Africa. There is a clear need for interventions to prevent tik use in South Africa and to mitigate and address the impact of tik on multiple levels.

Keywords: methamphetamine, South Africa, qualitative

BACKGROUND

Methamphetamine is the second most widely abused illicit drug worldwide (UNODC, 2012). It is a highly addictive synthetic psychostimulant that increases energy and feelings of euphoria, among other physiological effects (Panenka et al., 2013). In South Africa, methamphetamine is primarily smoked using improvised glassware, and is known in South Africa as tik due to the “ticking” sound produced when smoked (Peltzer, Ramlagan, Johnson, & Phaswana-Mafuya, 2010). Methamphetamine first emerged in South Africa in the early 2000s, fuelled by economic, social and political changes after the end of apartheid (Peltzer et al., 2010; UNODC, 2012). Its use has increased steadily in the past decade, showing only a slight decline in recent years (Dada et al., 2012; Pluddemann, Dada, et al., 2010). The prevalence of methamphetamine (“tik”) use is highest in the Western Cape province, with its epicentre in the city of Cape Town (Peltzer et al., 2010).

Clinical and epidemiological research in the United States (U.S.) has documented the deleterious physiological impact of methamphetamine use. Acute symptoms of use typically include increased wakefulness and physical activity, decreased appetite, hypervigilance, arousal, restlessness, aggression and violent behaviour, sleeplessness and reduced appetite (Darke, Kaye, McKetin, & Duflou, 2008; Panenka et al., 2013; Romanelli & Smith, 2006). Methamphetamine is highly addictive, and over time many methamphetamine users become dependent (Barr et al., 2006). Chronic methamphetamine use has been associated with physical effects including extreme weight loss, severe decay and loss of teeth (Curtis, 2006; Hamamoto & Rhodus, 2009; Shaner, Kimmes, Saini, & Edwards, 2006), cardiopulmonary complications (Fronczak, Kim, & Barqawi, 2012; Tashkin, 2001; Wijetunga, Bhan, Lindsay, & Karch, 2004; Yeo et al., 2007; Yu, Larson, & Watson, 2003), and complications related to pregnancy and childbirth (Oro & Dixon, 1987; Sithisarn, Granger, & Bada, 2012). Additionally, methamphetamine use has been associated with increased risk of mental health problems, including anxiety, depression, and psychotic symptoms, and global neuropsychological impairment, particularly of memory, attention, and executive functioning (Chen et al., 2003; Cherner et al., 2010; Gonzalez et al., 2004; Marshall & Werb, 2010; Mehrjerdi, 2012; Scott et al., 2007; Ujike, 2002; Woods et al., 2005). Studies have also documented behavioural and affective changes associated with methamphetamine use, including increased libido and impulsivity and reduced inhibition, which may lead to risky sexual behaviour and increase vulnerability to acquisition of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (Carrico et al., 2012; Freeman et al., 2011; Lineberry & Bostwick, 2006; Payer, Lieberman, & London, 2011; Salo et al., 2002; Semple, Zians, Grant, & Patterson, 2005).

Beyond the individual user, methamphetamine use has been associated with problems at the inter-personal and community levels. Given the psychological effects of methamphetamine, combined with the behavioural and lifestyle characteristics of users, methamphetamine use has been associated with violence, including intimate partner or domestic violence (Baskin-Sommers & Sommers, 2006; Boles & Miotto, 2003; Sommers & Baskin, 2006). In addition, methamphetamine use has been associated with social stigma and isolation (Pluddemann, Flisher, McKetin, Parry, & Lombard, 2010a; Semple, Grant, & Patterson, 2005; Sorsdahl, Stein, & Myers, 2012); in one study, half of users reported negative effects of methamphetamine on their inter-personal relationship (Sommers, Baskin, & Baskin-Sommers, 2006). At a larger societal level, the financial burden of methamphetamine use on communities is significant. In the U.S., the average cost of healthcare per methamphetamine user was 9% higher than that for non-users, and methamphetamine users were less likely to be insured compared with non-users (Swanson et al., 2007). Beyond direct health care costs, resources forgone because of reduced productivity among methamphetamine users may pose a bigger economic burden on a community. Other broader effects include the social impact on children and families, including child neglect and injury, and the increased burden on law enforcement and the justice system (Parry, Pluddemann, Louw, & Leggett, 2004; Sommers et al., 2006; Watanabe-Galloway et al., 2009).

In South Africa, community-based work and substance use treatment data point to the need to understand the impact of a quickly growing epidemic of methamphetamine use, hereafter referred to as tik. In street intercept surveys in one Cape Town township, 18% of men and 12% of women reported ever having used tik (Simbayi et al., 2006), and in a neighbouring township, 58% of out-of-school substance-using adolescents reported tik use (Wechsberg et al., 2010). Admission data from substance abuse treatment centres in Cape Town confirms the burden of tik use. During a four-year period (2002–2006), the proportion of patients reporting tik as their primary substance of abuse increased steadily from 0.3% to 42.3%, representing the fastest increase in admissions for any particular drug ever noted in the country (Pluddemann, Myers, & Parry, 2008). While this proportion has tapered in recent years, to 39% in 2011 (Dada et al., 2012), over half of patients in treatment continue to report tik as either their primary or secondary substance of abuse. Based on data collected in 2010, the mean age of patients in treatment centres for tik abuse in Western Cape was 26 years, and tik was the second most abused drug (after marijuana) among treatment patients younger than 20 years (Pluddemann, Dada, et al., 2010). Overall, tik use is most common among young, male and ‘Coloured’ persons (an ethnic group of historically mixed race people, unique to South Africa) (Dada et al., 2012; Wechsberg et al., 2008).

Despite increasing concern about tik use in South Africa and anecdotal evidence of its impact on society as a whole (Parry, Myers, & Pluddemann, 2004; Sorsdahl et al., 2012), there is a dearth of research on perceptions and experiences related to the impact of tik in South Africa’s most hard-hit communities. Such knowledge is important in order to inform locally appropriate intervention strategies to prevent and treat tik use and mitigate its impact on local health and development goals. The aim of this study therefore was to explore qualitatively local impressions of the impact of tik use at the individual, inter-personal and community levels in a peri-urban township in Cape Town.

METHODS

The qualitative data presented in this paper are part of a larger mixed-methods study that examined substance use and related risk behaviours in the context of alcohol-serving venues in one South African township. For this paper, the data were analysed to examine the perspectives around the impact of tik at multiple levels of influence.

Setting

This study was conducted in Delft, a township located 15 miles from Cape Town’s city centre. The township was established in 1990 and is currently home to over 75,000 residents, including a fairly even mix of both Black African and Coloured persons. The terms Black and Coloured originate from the apartheid era and refer to demographic markers that do not necessarily signify inherent characteristics. The terms refer to people of African and mixed (African, European and/or Asian) ancestry, respectively. Delft has high levels of unemployment, poverty and crime, and there is little commercial infrastructure. According to the 2001 South African census, 45% of residents in the area were unemployed, and the majority of adults who were employed were unskilled and manual labourers (South Africa Census Bureau, 2003).

The study recruited from twelve alcohol-serving venues in Delft. The venues were identified using an adaptation of the PLACE community mapping methodology (Weir, Tate, Zhusupov, & Boerma, 2004). Brief community intercept surveys were conducted with 210 individuals, approached at public places such as bus stands and markets. These surveys identified 88 sites where people go to purchase and drink alcohol. All sites were visited and assessed for study eligibility: reporting over 50 unique patrons per week who drank in the venue, having at least 10% female patronage, and willing to have the study team visit on multiple occasions. A total of 24 eligible venues were identified and twelve were purposively selected to provide representation of culture (predominantly Black or Coloured patronage), size (small and large venues), and geographic location in the community. The precise number of venues in the community is unknown, given that both legal and illegal venues operate in the community and frequently close and reopen. However, neighbouring townships have documented a high density of alcohol serving venues (Weir, Morroni, Coetzee, Spencer, & Boerma, 2002). Alcohol-serving venues are important social spaces in the South African township community (Eaton et al., 2013; Morojele et al., 2006), and therefore are sites where general community norms, perceptions and experiences may be assessed.

Data collection

After a week-long period of observations in the venues, fieldworkers (South Africans matched by language and ethnicity to the selected venues) approached individuals who were identified as regular patrons at the venues to invite them to participate in an in-depth interview. All individuals who were approached agreed to participate, and after written consent, interviews were conducted in a private room in the language of the participant’s choice (Afrikaans, Xhosa or English). Interviews lasted approximately 60 minutes and were audio-recorded with the participant’s permission. A grocery card valued at 100 Rands (approximately 15 USD) was provided as compensation.

Interviewers used a semi-structured guide with open-ended questions and possible probes (Mack, Woodsong, MacQueen, Guest, & Namey, 2005). The guide included questions about both personal experience with tik, as well as impressions of the impact of tik use in the community. In addition, tik use was allowed to emerge in relation to discussions about other issues (e.g., the context of crime and violence in the community and broader problems facing the community).

All study procedures were approved by the ethical review boards of Duke University, University of Connecticut and Stellenbosch University.

Analysis

The interview audio-recordings were simultaneously translated and transcribed in English. Analytic memos were then written for each transcript in order to summarize emerging themes and identify in vivo codes, terms and interpretations in participants’ own words. The memos were entered into Atlas.ti and all text related to tik use was coded. The textual data was analysed using content analysis (Patton, 2002), which involved both inductive and deductive analytic techniques to identify the themes related to the impact of tik at multiple levels of the social-ecological framework (individual, inter-personal and community) (Stokols, 1996). The coded text was reviewed and discussed by the first two authors and axial coding identified subcategories and highlighted representative text for each.

RESULTS

Description of the sample

The sample included 55 women (29 Black and 26 Coloured) and 37 men (18 Black and 19 Coloured). The ages of respondents were 18 to 59 (mean 35.2, SD 11.5). More than a quarter of Coloured respondents mentioned personal tik use, and almost a half (44%) mentioned tik use by a close friend or relative. On the other hand, among Black respondents, none reported personal use and only four individuals (9%) reported knowing a close friend or relative who used tik.

Description of tik use in the community

Respondents reported that tik is most often used by Coloured youth, both male and female. Tik was described as being ubiquitous (“everybody uses drugs”) throughout the Coloured community in Delft, and as the drug of choice among young people. Tik houses, where tik is both purchased and used, were reportedly “in every area” of the Coloured sections of the township. Respondents said that tik typically costs R20 – R30 ($2.50 – $3.50) per “packet” (enough tik to achieve a single high) and that individuals generally smoked several packets per day.

Respondents most often pointed to peers or older boyfriends (among women), as introducing people to tik. Tik use was described as appealing to youth because it provided a sense of belonging and community, as well as excitement and a relief from boredom in an environment where young people may feel they lack future prospects. At the same time, respondents pointed to tik use as a way to deal with stressors in their lives, including abuse in the home (“it drives them to do drugs”), bad relationships or unemployment. They explained that tik was often used in a succession of substances, following use of marijuana and alcohol, and in two cases proceeded by heroin use, which was rare in this community. For tik users in this sample, alcohol was often used subsequent to tik use as a “downer” that helped to facilitate sleep and to calm the body and mind.

Respondents recounted efforts of tik users to seek drug rehabilitation services, with mixed results. They said that residential substance treatment was available in Cape Town, but that services were private and therefore expensive. Respondents also had the impression that attempts at treatment generally failed, with people continuing to use while in treatment, or reinitiating tik use when they returned to their social environment.

Impact of tik use

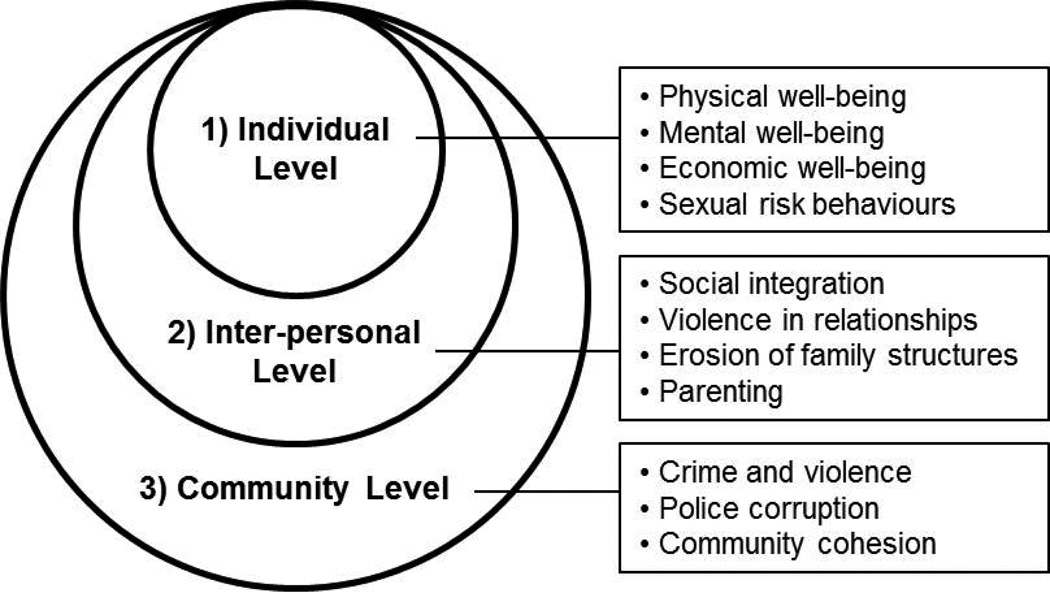

Narratives revealed that tik had a significant impact at three levels: 1) on the individual tik user, 2) on inter-personal relationships and households, and 3) on the community as a whole (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of themes related to impact of tik use

1) Impact of tik at an individual level

Physical well-being

Heightened energy and sleeplessness were the primary physiological characteristics that most respondents associated with tik, and respondents noted these physiological changes as the first clear sign of someone’s tik use. One woman described her teenage son: “That up and down, that busyness. That’s how we found out that he was using tik.” Respondents also talked about tik contributing to malnutrition and weight loss, lack of hygiene, and other physical ailments such as a “hole in the stomach” (i.e., ulcers) and the contraction of HIV and tuberculosis. A few respondents also noted that tik contributed to premature death, as this respondent described: “They found him (a 20 year old) in the toilet with the pipe still in his hand. He just fell over.”

Mental well-being

Tik users talked about how tik made them feel good (“nice and confident”) when they began using, but then led them to feeling “crazy,” “restless” and like a “zombie.” One woman talked about how her tik use made her feel depressed and suicidal. She recounted: “I just want the light to come on. I am dead inside. I think it is the tik that made me like this.” This woman said that her tik use made her incredibly lonely, because it had isolated her from her family and people close to her. She added that it made her feel that she had lost control over her life. At the same time, a few other tik users talked about how tik actually had the effect of numbing them from the emotional pain in their lives. A woman who was in an abusive relationship said she used tik because it “makes my mind feel at ease.”

Economic well-being

Men in particular talked about the impact of tik use on one’s economic standing, leading to the loss of employment and the erosion of any savings or investments. As one male former tik user said: “Once you have money, you do not spend it on anything positive. It goes straight to the drug dealer.” Others talked about how they sold everything they owned, including their appliances, jewellery, and phones, in order to pay for the drug. Respondents explained that tik use often leaves people with hardly any possessions, with one woman saying: “They (tik users) become so desperate that they even sell their clothes because of their addiction.” Tik use was also described by some as undercutting future opportunities, because tik users often dropped out of school or spent time in jail because of tik-related crime.

Sexual risk behaviours

Many respondents noted that tik use contributed to greater sexual risk behaviours because of both the heightened sexual energy while high, as well as the practice of exchanging sex for the drug. Some respondents described tik as making people “hypersexual;” one woman explained how after her sister started using tik, her “sex life escalated.” Women often spoke about having sex as a primary way to procure tik, as this female tik user described: “You meet a guy and you know what it’s about. It’s what you can get, no love or any other emotion. If he dangles his money and you get your share to feed your habit, you’ll sleep with that person.” The exchange of sex for drugs was also mentioned by many male respondents, who said they could get sex from female tik users. One man explained: “Let’s say I feel like having sex. Now I’ll see a woman who is a drug addict. I will tell her that I’m gonna buy her some tik in exchange for sex, and she’ll agree.”

Tik use seemed to not only increase the number of sexual partners, but also made it less likely that condoms would be used during sexual encounters. A man described how his tik use impacted his risk behaviour to a greater extent than his alcohol use: “With alcohol I can make rational decisions concerning sex. I will remember to use a condom. With drugs it’s a completely different case – I won’t remember to use a condom.” A few female tik users discussed the heightened risk of forced sex under the influence of tik, due to powerlessness to refuse sex from a partner, as this woman explained related to an act of coerced sex: “I was already high from the drugs, and I felt paralyzed and could not get out of the room.”

2) Impact of tik at an inter-personal level

Social integration

Tik users were described by most as exhibiting anti-social behaviours such as unprovoked aggression, and lack of a sense of obligation and connection to others. One female tik user elaborated: “You feel confident, macho. You do what you want and don’t feel anything. You have no remorse.” The narratives revealed a sense that tik users “can’t control themselves” and will “do anything to get drugs.” As a result, tik users seemed to exist on the margins of society and were characterized as lacking meaningful relationships and connections with others.

Violence in relationships

Many women who were in relationships with tik users discussed abuse and controlling behaviours by their partners. A woman described what happened when her boyfriend used tik: “He swears at me. He wants to hit me and threatens that he is going to kill me.” The respondent then explained that when she uses tik, the abuse is often bi-directional, because she feels empowered from tik to fight back. A woman who uses tik with her husband explained how their relationship is marked by physical abuse: “I will always start fighting first when I don’t get my way. He will choke me so that no one will see the marks, but I will take a knife to stab him.”

Erosion of family structures

Many respondents recounted stories of how their families or other families they know have been devastated by tik use. Homes where tik is used were described as sites of “chaos.” A woman said that the drug makes her sister, a tik user, “very aggressive; she doesn’t even have respect for my mother.” Many respondents recounted how tik users steal from their families, including a young man who said that he took his father’s car and sold it in order to pay for his drug use. There were also accounts of tik users physically abusing other members of their household. In one case, a woman reported how her teenage son tried to burn her with a hot iron after she told him he could not sell tik from their home. Through these stories, it is clear that the aggression, lack of respect, and theft of tik users against their families can result in a breakdown of trust and cohesion of the family unit. Parents in particular were torn between their love for their son or daughter who uses tik, and their sense of hurt and anger toward their child. One father explained: “I think of my household things disappearing. If that was a stranger, I would have killed him. In this case it’s my child. I raised him and loved him.”

Narratives highlighted that tik use in the family has an additional effect of reducing the economic and social well-being of households through poverty and unemployment of the family members, and in many cases ostracizing those families from the larger social fabric. The accounts suggested that families from a range of backgrounds in the community are experiencing tik use, and despite the ubiquity of tik, families that are personally impacted by tik use are stigmatized. As a result, families are often reluctant to admit to tik use in their household because, as one participant said, “you don’t want to be put in a bad light.”

Parenting

Several respondents talked about the impact of tik use on young children through poor birth outcomes, neglect, and exposure to drug use and violence that may produce a potential inter-generational cycle of behaviour. In this setting, because tik use is most common among young people and is associated with sexual risk behaviours, accounts of pregnancy among female tik users was not uncommon. One woman talked about how her child was born prematurely due to her tik use, and later died. Respondents explained that children of tik users are often neglected, primarily due to the long cycles of intoxication of the parents. They explained that tik users often spend money on the drug before spending money on food for their children. In many cases, grandparents take up the role of caring for children of tik users. Active tik users in the sample were in many cases acutely aware of the impact of their tik use on their children, saying that they “want the best” for their children and desire to do more to “set good examples” for their children in order to prevent the inter-generational continuation of drug use behaviour.

3) Impact of tik at a community level

Crime and violence

Almost all respondents, both Black and Coloured, attributed rampant crime in the community to tik users. Multiple respondents talked about tik users stealing “everything in sight,” including washing that is hung out to dry or shoes that are left on the front steps. Reports of theft of metal, including metal gates, corrugated metal roofing, pipes and wires, was common; tik users take the metal to scrap yards to get cash to buy drugs. In addition, many respondents talked about the constant fear of being mugged by tik users who steal wallets or cell phones. The narratives indicated that this rampant crime by tik users impacts the community’s economic well-being and the capacity to build wealth. As one man said: “It breaks [us] to see the stuff that [we] worked hard to buy, get stolen and sold for almost nothing.”

In addition, another significant and commonly cited threat to the general safety of the community was gangs who controlled the distribution of tik in the community. Several respondents talked about how “wars” often break out between rival gangs who are fighting for control of territory within the township. A male respondent explained: “The one owner will build up his followers; the other one will build up his followers. That’s how the two gangs are formed, and they end in gang wars. Kids are shooting guns, and that is how many parents lose their kids to drugs.” Stories indicated that young people who use tik often become caught up in the system of distributing tik for a gang leader or a tik dealer. Refusing to be part of this system can result in violent reactions, as this woman explained: “[My friend’s] boyfriend was told to sell tik. When he refused he was killed, shot.”

Police corruption

Many respondents expressed feeling helpless to respond to tik use and its consequences because of a perception of corruption in the police system that protects tik dealers. Respondents talked about how police are “friendly with the drug lords” or “working with the drug dealers,” and a perception that the police alert tik dealers if a raid is coming so that “the real dealer is never caught.” This perception of not only corruption, but also complicity in the drug trade, makes people “scared to go to the police.”

Community cohesion

The feelings of helplessness and hopelessness that participants expressed toward responding to tik use in their community seemed to undermine a sense of community identity and cohesiveness. As one respondent said, the community is “changed totally… [it] was a very quiet place and had respectable people, but since the drugs came in, a lot of people changed a lot.” Respondents described pervasive tik use and its consequences as “a problem no one can solve,” and said they feel “depressed and tired” in dealing with it. Tik also seemed to create and deepen divisions by race and age in the community. In speaking about tik users, respondents often referred more generally to “the Coloureds” or “the children,” as if they were solely and all responsible for tik use.

The lives and identities of young people seem to be most strongly impacted by the presence of tik in the community. In a context of poverty and unemployment, the tik merchants and “gangsters” often rise to the status of role models for young people—a glorified symbol of opportunity and prosperity. One respondent noted that young people look to tik merchants because they are “the ones wearing the Nikes and the different brand names.” At the same time, some former drug users described taking initiatives to help prevent tik use in their community or mitigate the impact of tik use. One former tik user explained how he had taken it upon himself to work with young people to help them to stop using tik: “They stopped [using tik] by themselves because I spoke a lot to them. I told them, just see how I looked when I was using, and see how you guys look now.” These older, former drug users said that their strategy in talking with young tik users is to encourage them to look towards the future and to begin to build a life for themselves that is not mired with drugs. These individuals said they felt motivated to do this because of the personal benefit they experienced rehabilitating from drug use.

DISCUSSION

Our results highlight the impact that the growing tik epidemic has had on a peri-urban township in Cape Town, South Africa. Similar to other small epidemiological studies (Simbayi et al., 2006; Wechsberg et al., 2010), tik use in our sample was most common among Coloured respondents, and tik was seen as having the most negative impact on the Coloured community. However, in a mixed-race township like the one of our study, tik also has a significant impact on the Black community, particularly as it related to crime, violence and community cohesion. The impact of tik was evident at the levels of the individual, inter-personal relationships and community, suggesting that interventions and policy approaches are needed to target multiple levels of the social-ecological framework.

At the individual level, tik use in this community clearly has an impact on the lives of individual users, whose health, well-being, social integration and future prospects are impacted by their substance use. At the same time, the physiological impacts of tik (e.g., mania, hypervigilance, aggression and sleeplessness) contribute to a cascade of consequences beyond the individual user. Our data show that the impacts are perhaps most striking at the household level, where relationships appear to be typified by aggression, including intimate partner violence (in many cases bi-directional), and violence towards other family members. Despite the household impact, perceived and experienced stigma against substance users may prevent families from seeking assistance for themselves or for the family member who is using tik (Sorsdahl et al., 2012). Young children in the household appear to be particularly impacted by the influence of tik use, with our findings suggesting that children of tik users suffer from parental neglect and may be vulnerable to abuse. In U.S. settings, studies have clearly shown that exposure to elicit substance use in the home is associated with worse academic performance, emotional and behavioural problems, and future substance use disorders (Solis, Shadur, Burns, & Hussong, 2012), highlighting the importance of identifying and providing services to children in households where tik is being used. At a larger societal level, participants saw tik as closely linked to crime and violence in the community, and in turn to economic decline and social disintegration in a setting already heavily burdened by poverty and other social problems. The relationship between methamphetamine and property crime has been identified in other settings (Gizzi & Gerkin, 2010), but the descriptions in our study of the ubiquity of opportunistic tik-related crimes in this setting (e.g., multiple respondents talked about their clothes being stolen when they are hung out to dry or metal roofing being stolen from their homes) speaks to the pervasiveness and depth of this impact.

Our findings point to the need for a collection of policy and programmatic approaches to prevent tik use and to mitigate its impact on households and community. Youth are the most appropriate target for prevention efforts, given the propensity for tik use to be introduced by peer groups during adolescence (Pluddemann, Flisher, McKetin, Parry, & Lombard, 2010b). Evaluations of drug prevention efforts suggest some effectiveness of school-based, media and family-based interventions, but highlight the need to combine these approaches to have the most impact (Babor, 2010). At the same time, it is clear from our data that public health approaches in this setting must be accompanied by policy approaches that favour structural changes to provide youth with outlets for recreation and job training, where they can develop future prospects and identify alternative role models. Services for chronic tik users must begin with identification of users – done in collaboration with schools, community organizations, clinics and the community justice system – followed by linkage and retention in appropriate treatment programs. Government-funded out-patient treatment centres exist for tik users in the Western Cape, but these centres should be better promoted in the community, with barriers to access assessed and alleviated. In order to mitigate the impact of tik on households, family-level therapy may be particularly beneficial in homes where tik is used, and may support the drug user on a course of recovery (Margolis & Zweben, 2011). At the community level, adequate policing, accompanied by transparency and accountability in the police sector, is sorely needed both to directly address tik-associated crime, as well as to build a sense of community in responding to the problem. At the same time, the police require training to identify tik addiction and implement appropriate referral mechanisms. Policies that favour getting criminal offenders into addiction treatment may ultimately result in better community outcomes than channelling these offenders through the traditional criminal justice system (Gottfredson, Najaka, & Kearley, 2003).

In a setting of high HIV prevalence like South Africa, tik is particularly concerning because it may further exacerbate factors that put one at risk of HIV. As our data suggest, tik use is associated with sex trade, multiple partners and inconsistent use of condoms, relationships that have been demonstrated quantitatively in South Africa (Meade et al., 2012; Pluddemann, Flisher, Mathews, Carney, & Lombard, 2008; Wechsberg et al., 2010). In communities such as this one, HIV intervention efforts should target tik users for HIV prevention, as well as HIV testing and linkage to care. Additional qualitative research with active tik users would help to shed more light on HIV knowledge, attitudes and risk behaviours, in order to better target HIV services to this community.

This study captured narratives of tik use and the impact of tik on a single township community in Cape Town, South Africa. The qualitative data is rich and allows exploration of context, but it is not without limitations. Tik was not the sole focus of the interviews, so it was not discussed with consistency across interviews. Stigma around tik use may have made it difficult for respondents to discuss personal experiences with tik use, therefore under-reporting the individual use and impact of the drug. Respondents were sampled from alcohol-serving venues, so they represent only a subset of the community. Within the venues, respondents were purposively selected due to their frequency of attending the venue, and so may not represent all venue attenders. It is impossible to ascertain whether tik use was over-represented or under-represented in this group. On the one hand, the sample was limited to individuals who were already engaging in substance use (i.e., alcohol), and may therefore be more likely than the general population to engage in drug use. On the other hand, current tik users may be less likely than the general population to attend alcohol-serving venues, given their social marginalization and lack of disposable income. Future studies should explore qualitative narratives among tik users who are recruited at the community level in order to examine these topics among a broader range of users.

Conclusion

The findings from our study highlight the need to focus on tik use in township communities in the Western Cape as an urgent matter of social development, safety and public health. Although our findings are specific to this particular region in South Africa, they offer lessons for other low-resource settings that might experience emerging and concentrated epidemics of methamphetamine. The findings highlight the potential impact of a new methamphetamine epidemic on individuals, households and communities, and the need to harness a comprehensive and multi-sectoral policy response to drug prevention and treatment, which can address the impact of use at the individual, inter-personal, and community levels.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) (R01 AA018074). Production of this manuscript was further supported by a career development grant to Dr. Meade (K23 DA028660), a study of methamphetamine users in South Africa (R03 DA033828), and the Duke Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI064518). We are grateful to all the men and women who participated in this study. We would like to acknowledge the South African research team that collected the data, specifically Simphiwe Dekeda, Albert Africa, Judia Adams, Bulelwa Nyamza and Jabulile Mantantana.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Babor T. Drug policy and the public good. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Barr AM, Panenka WJ, MacEwan GW, Thornton AE, Lang DJ, Honer WG, Lecomte T. The need for speed: an update on methamphetamine addiction. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience. 2006;31(5):301–313. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin-Sommers A, Sommers I. Methamphetamine use and violence among young adults. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2006;34(6):661–674. [Google Scholar]

- Boles SM, Miotto K. Substance abuse and violence: A review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2003;8(2):155–174. [Google Scholar]

- Carrico AW, Pollack LM, Stall RD, Shade SB, Neilands TB, Rice TM, Woods WJ, Moskowitz JT. Psychological processes and stimulant use among men who have sex with men. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;123(1–3):79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CK, Lin SK, Sham PC, Ball D, Loh EW, Hsiao CC, Chiang YL, Ree SC, Lee CH, Murray RM. Pre-morbid characteristics and co-morbidity of methamphetamine users with and without psychosis. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33(8):1407–1414. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherner M, Suarez P, Casey C, Deiss R, Letendre S, Marcotte T, Vaida F, Atkinson JH, Grant I, Heaton RK, Group H. Methamphetamine use parameters do not predict neuropsychological impairment in currently abstinent dependent adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;106(2–3):154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis EK. Meth mouth: a review of methamphetamine abuse and its oral manifestations. General Dentistry. 2006;54(2):125–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dada S, Pluddemann A, Parry C, Bhana A, Vawda M, Perreira T, Nel E, Mncwabe T, Pelser I, Weimann R. Monitoring alcohol and drug abuse trends in South Africa, July 1996 – December 2011. South African Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use (SACENDU) Research Brief. 2012;15(1) [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Kaye S, McKetin R, Duflou J. Major physical and psychological harms of methamphetamine use. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008;27(3):253–262. doi: 10.1080/09595230801923702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton LA, Kalichman SC, Pitpitan EV, Cain DN, Watt MH, Sikkema KJ, Skinner D, Pieterse D. The relationship between attending alcohol serving venues nearby versus distant to one's residence and sexual risk taking in a South African township. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10865-013-9495-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman P, Walker BC, Harris DR, Garofalo R, Willard N, Ellen JM Adolescent Trials Network for, H. I. V. A. I. b. T. Methamphetamine use and risk for HIV among young men who have sex with men in 8 US cities. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2011;165(8):736–740. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fronczak CM, Kim ED, Barqawi AB. The insults of illicit drug use on male fertility. Journal of Andrology. 2012;33(4):515–528. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.110.011874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gizzi MC, Gerkin P. Methamphetamine use and criminal behavior. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2010;54(6):915–936. doi: 10.1177/0306624X09351825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez R, Rippeth JD, Carey CL, Heaton RK, Moore DJ, Schweinsburg BC, Cherner M, Grant I. Neurocognitive performance of methamphetamine users discordant for history of marijuana exposure. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;76(2):181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson DC, Najaka SS, Kearley B. Effectiveness of drug treatment courts: evidence from a randomized trial. Criminology and Public Policy. 2003;2(2):171–196. [Google Scholar]

- Hamamoto DT, Rhodus NL. Methamphetamine abuse and dentistry. Oral Diseases. 2009;15(1):27–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2008.01459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lineberry TW, Bostwick JM. Methamphetamine abuse: a perfect storm of complications. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2006;81(1):77–84. doi: 10.4065/81.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack N, Woodsong C, MacQueen K, Guest G, Namey E. In-depth interviews Qualitative research methods: A data collector's field guide. Research Triangle Park, NC: Family Health International; 2005. pp. 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Margolis RD, Zweben JE. Treating patients with alcohol and other drug problems: an integrated approach. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall BD, Werb D. Health outcomes associated with methamphetamine use among young people: a systematic review. Addiction. 2010;105(6):991–1002. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade CS, Watt MH, Sikkema KJ, Deng LX, Ranby KW, Skinner D, Pieterse D, Kalichmann SC. Methamphetamine use is associated with childhood sexual abuse and HIV sexual risk behaviors among patrons of alcohol-serving venues in Cape Town, South Africa. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;126(1–2):232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrjerdi ZA, Alireza Noroozi Alasdair M, Barr Hamed Ekhtiari. Attention deficits in chronic methamphetamine users as a potential target for enhancing treatment efficacy. Basic and Clinical Neuroscience. 2012;3(4):5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Morojele NK, Kachieng'a MA, Mokoko E, Nkoko MA, Parry CD, Nkowane AM, Moshia KM, Saxena S. Alcohol use and sexual behaviour among risky drinkers and bar and shebeen patrons in Gauteng province, South Africa. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;62(1):217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oro AS, Dixon SD. Perinatal cocaine and methamphetamine exposure: maternal and neonatal correlates. Journal of Pediatrics. 1987;111(4):571–578. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(87)80125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panenka WJ, Procyshyn RM, Lecomte T, MacEwan GW, Flynn SW, Honer WG, Barr AM. Methamphetamine use: a comprehensive review of molecular, preclinical and clinical findings. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;129(3):167–179. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry CD, Myers B, Pluddemann A. Drug policy for methamphetamine use urgently needed. South African Medical Journal. 2004;94(12):964–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry CD, Pluddemann A, Louw A, Leggett T. The 3-metros study of drugs and crime in South Africa: findings and policy implications. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30(1):167–185. doi: 10.1081/ada-120029872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3 ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Payer DE, Lieberman MD, London ED. Neural correlates of affect processing and aggression in methamphetamine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68(3):271–282. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K, Ramlagan S, Johnson BD, Phaswana-Mafuya N. Illicit drug use and treatment in South Africa: a review. Substance Use and Misuse. 2010;45(13):2221–2243. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2010.481594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluddemann A, Dada S, Parry C, Bhana A, Bachoo S, Perreira T, Nel E, Mncwabe T, Gerber W, Freytag K. Monitoring alcohol and drug abuse trends in South Africa, July 1996 – June 2010. South African Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use (SACENDU) Research Brief. 2010;13(2) [Google Scholar]

- Pluddemann A, Flisher AJ, Mathews C, Carney T, Lombard C. Adolescent methamphetamine use and sexual risk behaviour in secondary school students in Cape Town, South Africa. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008;27(6):687–692. doi: 10.1080/09595230802245253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluddemann A, Flisher AJ, McKetin R, Parry C, Lombard C. Methamphetamine use, aggressive behavior and other mental health issues among high-school students in Cape Town, South Africa. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010a;109(1–3):14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluddemann A, Flisher AJ, McKetin R, Parry C, Lombard C. A prospective study of methamphetamine use as a predictor of high school non-attendance in Cape Town, South Africa. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2010b;5:25. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-5-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluddemann A, Myers BJ, Parry CD. Surge in treatment admissions related to methamphetamine use in Cape Town, South Africa: implications for public health. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2008;27(2):185–189. doi: 10.1080/09595230701829363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanelli F, Smith KM. Clinical effects and management of methamphetamine abuse. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26(8):1148–1156. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.8.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salo R, Nordahl TE, Possin K, Leamon M, Gibson DR, Galloway GP, Flynn NM, Henik A, Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV. Preliminary evidence of reduced cognitive inhibition in methamphetamine-dependent individuals. Psychiatry Research. 2002;111(1):65–74. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JC, Woods SP, Matt GE, Meyer RA, Heaton RK, Atkinson JH, Grant I. Neurocognitive effects of methamphetamine: a critical review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychology Review. 2007;17(3):275–297. doi: 10.1007/s11065-007-9031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple SJ, Grant I, Patterson TL. Utilization of drug treatment programs by methamphetamine users: the role of social stigma. American Journal on Addictions. 2005;14(4):367–380. doi: 10.1080/10550490591006924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple SJ, Zians J, Grant I, Patterson TL. Impulsivity and methamphetamine use. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;29(2):85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner JW, Kimmes N, Saini T, Edwards P. "Meth mouth": rampant caries in methamphetamine abusers. AIDS Patient Care and STDS. 2006;20(3):146–150. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simbayi L, Kalichman S, Cain D, Cherry C, Henda N, Cloete A. Methamphetamine use and sexual risks for HIV infection in Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of Substance Use. 2006;11(4):291–300. [Google Scholar]

- Sithisarn T, Granger DT, Bada HS. Consequences of prenatal substance use. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health. 2012;24(2):105–112. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2012.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solis JM, Shadur JM, Burns AR, Hussong AM. Understanding the diverse needs of children whose parents abuse substances. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2012;5(2):135–147. doi: 10.2174/1874473711205020135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommers I, Baskin D. Methamphetamine use and violence. Journal of Drug Issues. 2006;36(1):77–96. [Google Scholar]

- Sommers I, Baskin D, Baskin-Sommers A. Methamphetamine use among young adults: health and social consequences. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31(8):1469–1476. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorsdahl K, Stein DJ, Myers B. Negative attributions towards people with substance use disorders in South Africa: variation across substances and by gender. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:101. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South Africa Census Bureau. Census 2001 - Delft. City of Cape Town: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stokols D. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1996;10(4):282–298. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-10.4.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson SM, Sise CB, Sise MJ, Sack DI, Holbrook TL, Paci GM. The scourge of methamphetamine: impact on a level I trauma center. Journal of Trauma. 2007;63(3):531–537. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318074d3ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashkin DP. Airway effects of marijuana, cocaine, and other inhaled illicit agents. Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 2001;7(2):43–61. doi: 10.1097/00063198-200103000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ujike H. Stimulant-induced psychosis and schizophrenia: the role of sensitization. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2002;4(3):177–184. doi: 10.1007/s11920-002-0024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNODC. World drug report. New York: United Nations Office on Drug Control (UNODC); 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe-Galloway S, Ryan S, Hansen K, Hullsiek B, Muli V, Malone AC. Effects of methamphetamine abuse beyond individual users. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2009;41(3):241–248. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2009.10400534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, Jones HE, Zule WA, Myers BJ, Browne FA, Kaufman MR, Luseno W, Flisher AJ, Parry CD. Methamphetamine ("tik") use and its association with condom use among out-of-school females in Cape Town, South Africa. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(4):208–213. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2010.493592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, Luseno WK, Karg RS, Young S, Rodman N, Myers B, Parry CD. Alcohol, cannabis, and methamphetamine use and other risk behaviours among Black and Coloured South African women: a small randomized trial in the Western Cape. International Journal on Drug Policy. 2008;19(2):130–139. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir SS, Morroni C, Coetzee N, Spencer J, Boerma JT. A pilot study of a rapid assessment method to identify places for AIDS prevention in Cape Town, South Africa. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2002;78(Suppl 1):i106–i113. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.suppl_1.i106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir SS, Tate JE, Zhusupov B, Boerma JT. Where the action is: monitoring local trends in sexual behaviour. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2004;80(Suppl 2):ii63–ii68. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.012336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijetunga M, Bhan R, Lindsay J, Karch S. Acute coronary syndrome and crystal methamphetamine use: a case series. Hawaii Medical Journal. 2004;63(1):8–13. 25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods SP, Rippeth JD, Conover E, Gongvatana A, Gonzalez R, Carey CL, Cherner M, Heaton RK, Grant I Group, H. I. V. N. R. C. Deficient strategic control of verbal encoding and retrieval in individuals with methamphetamine dependence. Neuropsychology. 2005;19(1):35–43. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.19.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo KK, Wijetunga M, Ito H, Efird JT, Tay K, Seto TB, Alimineti K, Kimata C, Schatz IJ. The association of methamphetamine use and cardiomyopathy in young patients. American Journal of Medicine. 2007;120(2):165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q, Larson DF, Watson RR. Heart disease, methamphetamine and AIDS. Life Sciences. 2003;73(2):129–140. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00260-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]