Abstract

Background

Severe obesity has increased yet childhood antecedents of adult severe obesity are not well understood.

Objective

Estimate adult-onset severe obesity risk in individuals with history of childhood physical and/or sexual abuse compared to those who did not report abuse.

Methods

Longitudinal analysis of participants from the U.S. National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (N=10,774) Wave II (1996; aged 12–22 years) followed through Wave IV (2008–09; aged 24–34 years). New cases of adult-onset severe obesity (BMI≥40 kg/m2 using measured height and weight) in individuals followed over 13 years who were not severely obese during adolescence (BMI <120% of 95th percentile CDC/NCHS growth curves).

Results

The combined occurrence of self-reported sexual and physical abuse during childhood was associated with an increased risk of incident severe obesity in adulthood in non-minority females (Hazard Ratio=2.5; 1.3, 4.8) and males (Hazard Ratio=3.6; 1.5, 8.5) compared to individuals with no history of abuse.

Conclusion

In addition to other social and emotional risks, exposure to sexual and physical abuse during childhood may increase risk of severe obesity later in life. Consideration of the confluence of childhood abuse might be considered as part of preventive and therapeutic approaches to address severe obesity.

Keywords: Childhood maltreatment, United States, severe obesity, Young Adult

INTRODUCTION

Severe obesity prevalence is rising faster than moderate obesity[1–6] and is expected to increase 130% by 2030[7]. While clinic and population-based studies have found high rates of adult psychological distress among severely obese individuals[8, 9], few studies have explored psychological distress-related antecedents of severe obesity since it was rare in the past[2]. Given difficulty in treating severe obesity[10, 11], its serious cardiometabolic[12, 13] and psychological co-morbidities[8, 14, 15] it is critical to discover predisposing factors to prevent development of severe obesity.

There is evidence that childhood psychological trauma is associated with obesity[16–23]. Small cross-sectional studies suggest childhood trauma is also associated with severe obesity[9, 24, 25] and weight-related behaviors[26, 27], including less success in weight loss treatment[9, 24, 28], perhaps due to psychobiological consequences such as elevated cortisol[29–31], disordered eating[32, 33], food addiction[34] or maintaining excess weight to ward off romantic interests[9, 32]. Other studies suggest variation by: physical versus sexual abuse[18, 19], females versus males[19, 20, 35], abuse severity[36] and age at time of abuse [37]. Yet these studies are largely based on small samples. The risk associated with childhood sexual and physical abuse and future incidence of severe obesity is unknown, particularly in race/ethnicity minorities[9, 38–42] who are disproportionately affected by child maltreatment[43] and are at high risk for adult severe obesity[1].

We used a large prospective, nationally representative, ethnically diverse cohort to examine risk of incident adult severe obesity over a 13-year period in adolescents followed into adulthood with history of childhood: 1) sexual abuse 2) physical abuse, or 3) combined occurrence of sexual and physical abuse (compared to no history of sexual or physical abuse), controlling for sex, age, race/ethnicity, and parental education. We hypothesized differential associations by sex, race/ethnicity, and abuse type such that the combined occurrence of sexual and physical abuse during childhood would be associated with higher risk of developing severe obesity in adulthood compared to no history of abuse.

METHODS

National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health)

Add Health is a prospective cohort study of 20,745 adolescents, representative of the U.S. school-based population in grades 7 to 12 (mean age 15.4 years in 1994–95) and followed over four examinations into adulthood (24–34 years of age). We used in-home survey data from Wave II (n=14,738; mean age 16.3 years in 1996), Wave III (n=15,197; mean age 21.7 years in 2002), and Wave IV (n = 15,701; mean age 28.3 years in 2009). Data from Wave I (1994–95) were not used because only self-report height and weight were available. The study population was obtained through a systematic random sample of 80 high schools and 52 middle schools in the U.S., stratified to ensure that the schools were representative of schools grades 7 through 12 with respect to region, urbanicity, school type, race composition, and school size[44, 45]. Add Health included a core sample plus subsamples of selected minority and other groupings collected under protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Study variables

Outcome: Severe obesity in adulthood

Heights and weights were measured at Wave II (baseline) through Wave IV (last follow-up) using standardized procedures[44]. In the few cases where a respondent was missing height and weight measurements at wave II, III, or IV (n=173) self-reported height and weight were consistently used as opposed to a mix of self-reported and measured data, to avoid differential misclassification across repeated observations. Sensitivity testing was used to assess the impact of including these 173 individuals in the analyses. Sex- and age-specific BMI (kg/m2) percentiles of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics growth curves[46] were used to classify severe obesity (BMI≥120% of 95th percentile[47]) and obesity (BMI≥95th percentile) in individuals <20 years of age. Sex- and age-specific BMI (kg/m2) percentiles of the IOTF growth curves and corresponding BMI=25 and BMI=30 equivalent cut offs were also used to classify overweight and obesity in individuals <20 years of age[48]. For individuals aged ≥20 years, adult BMI cut-points[49] were used to classify severe obesity (BMI≥40 kg/m2) and obesity (BMI≥30 kg/m2–39.9 kg/m2). Respondents who exceeded scale capacity at Wave III: 149.7 kg [n = 12] or at Wave IV: 199.6 kg [n = 2]) were classified as severely obese at each period.

Individuals were classified with incident severe obesity if they were not severely obese at baseline (Wave II, 1996) but became severely obese by either Wave III or Wave IV. Age at onset of severe obesity was defined as the age of the individual at the wave when he/she was first classified as severely obese. Thus, the first observation of severe obesity in either Wave III or IV designates incident severe obesity. The mean duration of follow-up time was 6 years.

Primary Exposure: Childhood Abuse

Childhood abuse was recalled during Wave III using a standardized recall set of questions based on the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scale[50] to record experience of childhood sexual and physical abuse by a parental or adult caregiver prior to the 6th grade. The scale has good discriminant validity and predictive efficiency with the elementary age recall time frame[51, 52]. Sexual abuse was queried as “how often had touched you in a sexual way, forced you to touch him or her in a sexual way, or forced you to have sexual relations?” Physical abuse was queried as “how often had one of your parents or other adult caregivers slapped, hit, or kicked you?” A summary variable reflected four discrete categories: 1) only sexual abuse, 2) only physical abuse, 3) combined occurrence of sexual and physical abuse, 4) or no sexual or physical abuse.

Confounders

We used a directed acyclic graph (DAG)[53, 54] to visualize conceptual causal relationships and identify a minimally sufficient adjustment set of literature-based confounders[1, 43]: sex, race/ethnicity [non-Hispanic white (non-minority) and Hispanic, non-Hispanic black, and non-Hispanic Asian (minority)], socioeconomic status (parental education > High School versus <High School), and age (<20 years [reference], 20–24.9 years, 25–29.9 years, and ≥30 years), recorded at each wave. We did not consider BMI during adolescence a confounder because: 1) it predicts risk for severe obesity[55] and 2) high BMI during adolescence might reflect a trajectory of increasing weight gain from childhood that could have resulted from exposure to abuse early in life. In both cases BMI would be a mediator and its inclusion would cause the model to be ‘overadjusted’ and biased towards the null[56–58]. Thus, adjusting for BMI would not be appropriate.

Analytic Sample

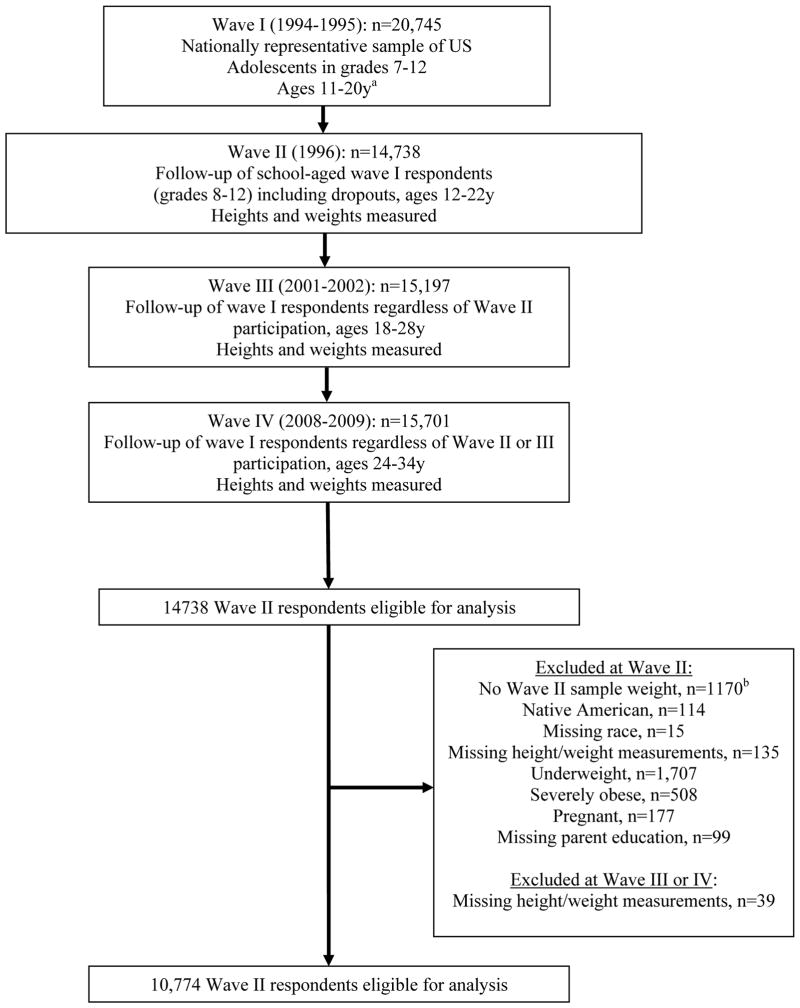

Among the 14,738 eligible respondents at Wave II, we excluded those with missing sample weights (n=1170), Native American (n=114) for inadequate sample size, missing race (n=15), missing baseline height and weight measures (n=135), underweight at baseline [BMI < 5th percentile CDC/NCHS growth curves <20 years[47]; BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 ≥20 years[49]] (n=1,707), baseline severe obesity (n=508) or pregnancy (n=177), missing data for parental education (n=99), and missing height and weights at waves III and IV (n=39), leaving 10,774 (79%) with complete exposure and outcome data from waves II–IV as the analytic sample (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Analysis Sample, derived from The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health.

a Wave I participants not included in the current analysis because it used self-reported height and weight data.

b Cases added in the field, selected as part of a paired subsample, or without a sample flag.

Compared to the respondents included in the analytic sample, those excluded had a statistically significantly (p <0.01) lower proportion of reported baseline sexual or physical abuse, lower mean parental education, and lower mean baseline BMI, and a greater proportion were males.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata software, version 12.1 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas) using survey analysis techniques to account for complex survey design[59, 60].

We used a discrete time hazards (with complementary log-log link) model as the appropriate survival model for the periodically-measured outcome. Risk of severe obesity was assessed at the period level. Model results indicate the probability of incident severe obesity in between waves (hazard ratio dependent on time), in contrast to a cumulative incidence model where risk is assumed to be constant throughout the study period. Models tested for differences in severe obesity incidence by childhood sexual abuse, physical abuse, and the combined occurrence of sexual and physical abuse (versus no abuse). Baseline cases of severe obesity were excluded to examine risk among individuals normal weight, overweight, or obese at baseline from Wave II to Wave IV. Cases were defined as incident severe obesity, with censoring at the end of follow-up for individuals who were not severely obese at baseline and those who did not become severely obese during the follow-up period.

We hypothesized differential associations between child abuse and incident severe obesity by race/ethnicity, given higher rates of obesity[1, 61] and child maltreatment[43] in minority versus non-minority populations, and by sex given differential obesity[1] and abuse[43] rates by sex. We tested interactions between sex and race/ethnicity with abuse type. Statistical significance was set at p<0.1 following standard epidemiological practice[62].

Sensitivity analyses

Three types of sensitivity analyses were conducted and compared to our central analysis models using Hausman tests[63]. First, we compared models including the small number of individuals with self-reported height and weight measures (n=173) to models that excluded these 173 individuals. Second, we excluded individuals with baseline obesity (BMI≥95th percentile) compared to baseline severe obesity (BMI≥120% of 95th percentile) to determine whether removing individuals at a lower baseline weight threshold would result in a different pattern of findings. Third, we addressed potential reporting bias due to retrospective report of childhood abuse by severe obesity[64, 65] by replicating the models excluding individuals severely obese at Wave III.

RESULTS

Approximately a quarter of respondents reported any abuse, with low rates of sexual abuse in the absence of physical abuse. Rates of abuse varied across sex and race/ethnicity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Selected characteristicsa,b of National longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health participants sex and race/ethnicity stratified.c

| Females

|

Males

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-minority n=2,936 | Minority n=2,411 | Non-minority n=2,963 | Minority n=2,464 | |

|

|

|

|||

| Sexual and/or physical abuse by 6th gradea | ||||

| no abuse | 78.5 (76.2,80.6) | 76.1 (72.6,79.2) | 79.2 (77.1,81.0) | 78.0 (75.2,80.6) |

| sexual abuse only | 1.0 (0.6,1.6) | 0.9 (0.6,1.5) | 0.2 (0.1,0.4) | 0.3 (0.1,0.8) |

| physical abuse only | 18.0 (16.1,20.2) | 19.9 (17.0,23.2) | 18.2 (16.2,20.4) | 18.3 (15.8,21.0) |

| both sexual/physical | 2.5 (1.9,3.3) | 3.0 (2.2,4.1) | 2.4 (1.7,3.5) | 3.3 (2.5,4.5) |

| Mean baseline age (y) at Wave II, (SE) | 15.8 (0.1) | 16.0 (0.2) | 16.1 (0.1) | 16.3 (0.2) |

| Mean age at Wave III (y), (SE) | 21.3 (0.1) | 21.5 (0.2) | 21.5 (0.1) | 21.8 (0.2) |

| Mean age at Wave IV (y), (SE) | 27.8 (0.1) | 28.0 (0.2) | 28.0 (0.1) | 28.3 (0.2) |

| Parental education > HSa | 55.6 (52.0,59.2) | 39.8 (34.4,45.6) | 58.2 (53.6,62.7) | 43.4 (38.4,48.7) |

| Baseline weight status (aged 13–21 y) | ||||

| Baseline BMI b | 21.8 (20.1, 24.4) | 23.0 (20.6, 25.9) | 22.3 (20.5, 25.1) | 22.3 (20.5, 24.9) |

| CDC/NCHS Overweighta,d | 16.6 (14.8,18.5) | 22.0 (19.4,24.9) | 18.4 (16.8,20.1) | 18.8 (16.8,21.0) |

| CDC/NCHS Obesea,d | 8.2 (6.9,9.7) | 12.0 (10.1,14.2) | 12.2 (10.7,13.9) | 10.1 (8.6,11.8) |

| IOTF Overweighta,e | 18.1 (16.2, 20.1) | 25.4 (22.5, 28.4) | 22.6 (21.0, 24.4) | 23.3 (20.9, 25.8) |

| IOTF Obesea,e | 7.6 (6.4, 9.0) | 9.9 (8.3, 11.9) | 8.6 (7.2, 10.1) | 7.1 (5.8, 8.7) |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared, CDC/NCHS, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics, IOTF, International Obesity Task Force.

Column percentage (95% CI) presented for categorical variables.

Interquartiles 50% (25%, 75%) presented for continuous variables.

Sample consists of 10,774 individuals with measures in adolescence (Wave II, 1996; aged 12–22 years) and adulthood [(Wave III (2001–2002; aged 18–28 years); Wave IV (2007–2009; aged 24–34 years)]. Results were weighted for national representation and standard errors were corrected for multiple stages of cluster sample design and unequal probability of selection. Race/ethnicity is categorized as: non-minority (non-Hispanic White) and minority (Black, Asian, and Hispanic)

Sex- and age-specific BMI (kg/m2) percentiles of the CDCD/NCHS growth curves were used to classify overweight and obesity in individuals <20 years of age [46]: overweight as BMI≥85th to <95th percentile and obese as ≥95th (excluding those with severe obesity: ≥120% of 95th percentile[47]). For individuals aged ≥20 years of age: overweight was classified as BMI ≥25 to <30 kg/m2 and obese as BMI ≥30 to <40 kg/m.2

Sex- and age-specific BMI (kg/m2) percentiles of the IOTF growth curves and corresponding BMI=25 and BMI=30 equivalent cut offs were used to classify overweight and obesity in individuals <20 years of age[48]: overweight as BMI≥25 to <30 kg/m2 and obese as ≥30 (excluding those with severe obesityd). For individuals aged ≥20 years of age: overweight was classified as BMI ≥25 to <30 kg/m2 and obese as BMI ≥30 to < 40 kg/m.2d

Over 13 years of follow-up there were 722 cases of incident severe obesity, an overall incidence rate of 6.7% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 6.0%, 7.5%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Incidence of severe obesity by self-reported childhood abuse, across sex and race/ethnicity, National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health.a

| Number, Incidence % (95% Confidence Interval)

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Overall | Childhood abuse | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| N | No abuse | N | Sexual abuse only | N | Physical abuse only | N | Both sexual and physical abuse | |||

| Female | ||||||||||

| Non-minority | 2,936 | 8.2 (6.8,9.8) | 2,303 | 6.6 (5.2,8.4) | 26 | 16.4 (5.3,40.7) | 523 | 11.4 (5.3,40.7) | 84 | 19.1 (10.8,31.6) |

| Minority | 2,411 | 11.4 (9.3,14.0) | 1,816 | 10.2 (7.9,13.0) | 31 | 8.2 (1.6,33.1) | 491 | 15.2 (1.6,33.1) | 73 | 8.9 (3.0,23.9) |

| Male | ||||||||||

| Non-minority | 2,963 | 6.3 (5.0,7.9) | 2,307 | 5.7 (4.5,7.3) | 9 | 0.0--b | 587 | 6.1 (2.9,12.3) | 60 | 21.2 (8.9,42.4) |

| Minority | 2,464 | 7.2 (5.4,9.5) | 1,872 | 7.0 (5.2,9.3) | 8 | 0.0--b | 497 | 7.8 (4.5,13.2) | 87 | 7.7 (3.2,17.6) |

| Total | 10,774 | 6.7 (6.0,7.5) | 8,298 | 5.8 (5.2,6.5) | 74 | 10.5 (4.0,24.6) | 2,098 | 9.3 (4.0,24.6) | 304 | 15.5 (9.7,23.7) |

Analytic sample consists of 10,774 individuals measured in adolescence (Wave II, 1996; aged 12–22 years) and adulthood [(Wave III (2001–2002; aged 18–28 years); Wave IV (2008–2009; aged 24–34 years)]. Results were weighted for national representation and standard errors were corrected for multiple stages of cluster sample design and unequal probability of selection. Sex- and age-specific BMI (kg/m2) percentiles of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics growth curves were used to classify severe obesity in individuals <20 years of age[46]: severe obesity was classified as BMI≥120% of 95th percentile[47]. For individuals aged ≥20 years of age: severe obesity was classified as BMI≥40 kg/m2. Respondents who exceeded scale capacity at Wave III: 330 lb [n = 12] or at Wave IV: 440 lb [n = 2]) were classified as severely obese at each period. Respondents who were severely obese at baseline were excluded (n=507). Individuals were classified as having incident severe obesity if they were not severely obese at baseline (Wave II) but became severely obese by one of the two follow up periods (Wave III, 2001 or IV, 2009).

Confidence intervals were not estimated because there were no cases of severe obesity among males reporting sexual abuse only.

Severe obesity incidence was higher in minority (11.4%) than non-minority females (8.2%), with particularly high rates with combined occurrence of childhood sexual and physical abuse (19.1%) than across other abuse types. In contrast, rates were similar for non-minority and minority males, however we were unable to estimate severe obesity incidence in the few males self-reporting only sexual abuse. Severe obesity incidence was high in non-minority males with combined occurrence of sexual and physical abuse (21.2%).

In multivariate discrete time hazard analyses, non-minority males (Hazard Ratio [HR]= 3.6; 1.5, 8.5) and females (HR= 2.5; 1.3, 4.8), with combined occurrence of physical and sexual abuse were at higher risk for developing severe obesity compared to individuals not exposed to abuse (Table 3). There was statistically significant interaction for race/ethnicity and combined occurrence of physical and sexual abuse (p=0.02) and within sex-specific models (males: p=0.07; females: p=0.095). Findings are presented by sex despite lack of statistical interaction for conceptual reasons.

Table 3.

Associations between self-reported childhood abuse and incident adult severe obesity across 13 years in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Healtha, by sex and race/ethnicity.

| Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval)

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | No abuse | N | Sexual abuse only | N | Physical abuse only | N | Both sexual and physical abuse | |

| Female | ||||||||

| Non-minority (n=2,936) | 2,303 | 1.0 | 26 | 2.4 (0.7,7.9) | 523 | 1.6 (1.0,2.5) | 84 | 2.5 (1.3,4.8) |

| Minority (n=2,411) | 1,816 | 1.0 | 31 | 0.6 (0.1,3.6) | 491 | 1.4 (0.9,2.1) | 73 | 0.9 (0.3,2.5) |

| Male | ||||||||

| Non-minority (n=2,963) | 2,307 | 1.0 | 9 | --- | 587 | 1.1 (0.5,2.3) | 60 | 3.6 (1.5,8.5) |

| Minority (n=2,464) | 1,872 | 1.0 | 8 | --- | 497 | 1.1 (0.6,1.9) | 87 | 1.1 (0.5,2.8) |

| Total (n=10,774) | 8,298 | 74 | 2,098 | 304 | ||||

n=43,096 observations across analytic sample of 10,774 individuals in adolescence (Wave II (1996; aged 12–22 years)) and adulthood (Wave III (2001–2002; aged 18–28 years) and Wave IV (2008–2009; aged 24–34 years)). Hazard ratios (incidence rate ratios) and 95% confidence intervals were obtained from sex and race/ethnicity stratified, multivariate discrete time hazard regression models predicting incident severe obesity by childhood abuse (no abuse (reference), adjusted for age, childhood neglect, low-self esteem, parental education. Dashes represent models not estimated because there were no cases of severe obesity among males reporting sexual abuse only. Results were weighted for national representation and standard errors were corrected for multiple stages of cluster sample design and unequal probability of selection. Sex- and age-specific BMI (kg/m2) percentiles of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics growth curves were used to classify severe obesity in individuals <20 years of age[46]: severe obesity was classified as BMI≥120% of 95th percentile[47]. For individuals aged ≥20 years of age: severe obesity BMI≥40 kg/m2. Respondents who exceeded scale capacity at Wave III: 330 lb [n = 12] or at Wave IV: 440 lb [n = 2]) were classified as severely obese at each period. Respondents who were severely obese at baseline were excluded (n=507). Individuals were classified as having incident severe obesity if they were not severely obese at baseline (Wave II) but had become severely obese by one of the two follow up periods (Wave III, 2001 or IV, 2009).

The HRs in minority females suggest a positive association for individuals exposed to physical abuse compared to those reporting no abuse (HR=1.4; 0.9, 2.1), although the estimate overlapped the null. However, HRs for minority females exposed to sexual abuse alone or the combined occurrence of sexual and physical abuse were <1.0 with confidence intervals overlapping null. In non-minority females, estimates suggest increased risk in individuals exposed only to sexual abuse (HR=2.4; 0.7, 7.9) or only physical abuse (HR= 1.6; 0.96, 2.5) versus those reporting no abuse, although the estimates overlapped null.

Sensitivity analyses

First, there were no statistically significant differences between the models with, and without the 173 observations with self-reported heights and weights (Hausman test p=0.2). Second, we found a similar pattern of results using the baseline obesity versus severe obesity weight exclusion with only one difference (Hausman test p=0.01). The HR for physical abuse alone versus no abuse (HR=1.8; 1.0, 3.4) among minority females became almost statistically significant (p=0.05). Third, model estimates for models that excluded individuals who were severely obese at Wave III were very similar in pattern and strength of association compared to those in the central analysis sample, with one exception (Hausman test p<0.0001). The HR for non-minority males with the combined occurrence of sexual and physical abuse increased in magnitude and significance (HR=11.1; 4.2, 28.8) compared to the central analysis (HR=3.6; 1.5, 8.5) suggesting that any potential reporting bias was away from the null.

DISCUSSION

In this national, longitudinal and ethnically diverse study of U.S. adolescents followed 13-years into adulthood, we found greater risk of incident severe obesity in non-minority females and males with combined occurrence of sexual and physical abuse during childhood, relative to individuals with no history of abuse. Associations for physical abuse were similar in direction in non-minority and minority males and females. However, experiencing sexual abuse only or combined occurrence of sexual and physical abuse was not associated with risk of incident severe obesity among minority females. In sum, our findings suggest that in addition to other social and emotional risks, children exposed to combined occurrence of sexual and physical abuse may be at increased risk of developing incident severe obesity later in life with variation across race/ethnicity and sex.

Previous longitudinal studies and meta-analyses have found associations between childhood abuse and adult obesity[16, 18, 21, 23, 40, 42] although findings are inconsistent by race, sex, and abuse type[18–20, 35]. Fewer have examined how childhood abuse relates to severe obesity incidence. In a large study of health maintenance organization adult participants the risk of becoming severely obese in adulthood increased with the number of adverse events in childhood, although risk by abuse type was not assessed[17]. Differences across race/ethnicity, abuse type and sex have been largely overlooked.

Using the large nationally representative Add Health sample, we evaluated the association between childhood abuse (sexual only, physical only, or combined occurrence of sexual and physical abuse) and incident severe obesity, allowing for sex and race/ethnicity variation. We found no association between severe obesity and childhood abuse in minority females or males. While this is consistent with findings for whites but not blacks in a longitudinal study of 713 U.S. children [18], severe physical and sexual abuse in childhood were associated with adult obesity in large cohort of black women[36]. The development of severe obesity may involve different risk factors for minorities than for non-minorities, including socioeconomic disadvantage, social factors, and different body size perception[66–68].

We observed lower prevalence of childhood sexual abuse than others[69] perhaps because respondents reported abuse perpetrated by a caregiver only. Yet obesity rates were similar in our study compared to the above small prospective study where 42% of those with documented sexual abuse became obese in adulthood[23]. Thirty-three percent of our minority and non-minority female participants who reported experiencing sexual abuse only and 42% who reported experiencing both sexual and physical abuse became obese in adulthood.

When considering the reverse direction of influence (i.e., childhood obesity leading to abuse), the literature suggests this not to be the case[23, 70]. We addressed this direction of influence by running our analyses excluding the 1,110 participants classified as obese prior to reporting abuse, finding that the strength and direction of estimated effects were consistent to models including these 1,110 participants. Thus, our findings suggest agreement with the literature: that the association between child abuse and adult severe obesity is independent of adolescent obesity[23]. It is also possible that severely obese individuals might over-report child abuse[65, 69]. However a recent meta-analysis suggests that the associations of maltreatment with obesity are similar regardless of reporting method (court records versus retrospective report)[16]. When we excluded 374 participants who were severely obese at Wave III estimates were similar in strength and direction as in the models including these 374 participants, suggesting that severe obese participants do not over-report abuse.

While the great strength of our longitudinal study is the large sample size, allowing subgroup comparisons, there are some limitations. The participants excluded from our central analysis reported less childhood abuse than those who were included in our analytical sample, which could bias our estimates away from the null if the excluded participants developed severe obesity as much or more than the included participants. However, severe obesity incidence was considerably lower in excluded (2.7%) versus included (6.7%) individuals in our analytic sample. The survey did not include information on timing of abuse, identity of the abuser, duration and severity, or ongoing abuse spanning childhood and into adult years. While we only assessed the first observed severe obesity occurrence, we acknowledge that weight can fluctuate over time. While it would be ideal to control for BMI measured before any occurrence of abuse, this would require long-term prospective data spanning very early childhood to adulthood. There are simply no large-scale, population-based prospective studies that would allow this. Finally, even in our large sample we were unable to examine associations by racial/ethnic subpopulations.

Severe obesity was rare in the past but has increased to 6.3% in 2009–2010[71]. Yet little is known about childhood psychosocial factors that may predispose individuals to develop severe obesity in adulthood. Experimental[72–76] and epidemiological[77–80] evidence suggests that early life stress/maltreatment might have long-lasting adult physical health outcomes. Thus understanding how the confluence of childhood abuse and severe obesity risk can be managed to improve mental and physical health outcomes later in life is needed. Early identification of childhood abuse can prevent further abuse and its compounded harm and consequences. At the same time, individuals respond differently to childhood adversity[33] so understanding the characteristics of children resilient to childhood abuse will inform prevention and treatment efforts.

The mental health of severely obese individuals has mainly been assessed for surgery screening, yet new research suggests that cognitive behavioral therapy combined with behavioral weight management in obesity treatment can significantly improve successful weight loss[14]. Thus childhood abuse may need to be addressed in therapy before sustainable weight loss can proceed.

Our findings suggest a higher incidence of severe obesity among individuals exposed to combined occurrence of childhood sexual and physical abuse, with variation by gender and across non-minority versus minority individuals. Consideration of the confluence of childhood abuse and future severe obesity risk might improve pediatric and adult weight loss treatment and prevention thereby reducing severe obesity risk and associated co-morbidities.

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT?

Severe obesity prevalence in adults has increased close to double from the 1990’s to 2010 and is expected to double again by 2030.

Over 3 million reports of child maltreatment were received by child protective services in 2008.

While clinic and population-based studies have found high rates of adult psychological distress among severely obese individuals, little is known about how the experience of abuse during childhood relates to the risk of severe obesity later in life.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS?

Using data from a nationally representative, longitudinal study, we found that incidence rates and 13 year risk of developing severe obesity in adulthood varied by abuse type.

We found significantly higher risk of incident severe obesity in non-minority females and males who experienced the combined occurrence of sexual and physical abuse during childhood, relative to individuals with no history of abuse.

In addition to other social and emotional risks, exposure to sexual and physical abuse during childhood may increase risk of severe obesity later in life.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health grant R01HD057194. We thank Ms. Frances Dancy, BS, UNC Carolina Population Center for her helpful administrative assistance. P.G.L. and A.S.R. designed the study. P.G.L., A.S.R. and W.H.D. contributed to data analysis, and writing of the manuscript. The authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). We also are grateful to the Carolina Population Center (R24 HD050924) for general support.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- HR

Hazard Ratio

Footnotes

There were no potential or real conflicts of financial or personal interest with the financial sponsors of the scientific project. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):235–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(14):1723–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freedman DS, Khan LK, Serdula MK, Galuska DA, Dietz WH. Trends and correlates of class 3 obesity in the United States from 1990 through 2000. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(14):1758–61. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skelton JA, Cook SR, Auinger P, Klein JD, Barlow SE. Prevalence and trends of severe obesity among US children and adolescents. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9(5):322–9. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sturm R. Increases in morbid obesity in the USA: 2000–2005. Public Health. 2007;121(7):492–6. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang YC, Gortmaker SL, Taveras EM. Trends and racial/ethnic disparities in severe obesity among US children and adolescents, 1976–2006. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011 doi: 10.3109/17477161003587774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finkelstein EA, Khavjou OA, Thompson H, et al. Obesity and severe obesity forecasts through 2030. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(6):563–70. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petry NM, Barry D, Pietrzak RH, Wagner JA. Overweight and obesity are associated with psychiatric disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychosomatic medicine. 2008;70(3):288–97. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181651651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Felitti VJ. Childhood sexual abuse, depression, and family dysfunction in adult obese patients: a case control study. South Med J. 1993;86(7):732–6. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199307000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bray GA. Drug treatment of obesity. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2001;2(4):403–18. doi: 10.1023/a:1011808701117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanner BD, Allen JW. Complications of bariatric surgery: implications for the covering physician. Am Surg. 2009;75(2):103–12. doi: 10.1177/000313480907500201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fontaine KR, Redden DT, Wang C, Westfall AO, Allison DB. Years of life lost due to obesity. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289(2):187–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, et al. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289(1):76–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faulconbridge LF, Wadden TA, Berkowitz RI, Pulcini ME, Treadwell T. Treatment of Comorbid Obesity and Major Depressive Disorder: A Prospective Pilot Study for their Combined Treatment. Journal of obesity. 2011;2011:870385. doi: 10.1155/2011/870385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pull CB. Current psychological assessment practices in obesity surgery programs: what to assess and why. Current opinion in psychiatry. 2010;23(1):30–6. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328334c817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Danese A, Tan M. Childhood maltreatment and obesity: systematic review and meta-analysis. Molecular psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anda RF, V, Felitti J, Bremner JD, et al. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256(3):174–86. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bentley T, Widom CS. A 30-year follow-up of the effects of child abuse and neglect on obesity in adulthood. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17(10):1900–5. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuemmeler BF, Dedert E, McClernon FJ, Beckham JC. Adverse childhood events are associated with obesity and disordered eating: results from a U.S. population-based survey of young adults. J Trauma Stress. 2009;22(4):329–33. doi: 10.1002/jts.20421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mamun AA, Lawlor DA, O’Callaghan MJ, Bor W, Williams GM, Najman JM. Does childhood sexual abuse predict young adult’s BMI? A birth cohort study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(8):2103–10. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williamson DF, Thompson TJ, Anda RF, Dietz WH, Felitti V. Body weight and obesity in adults and self-reported abuse in childhood. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26(8):1075–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gustafson TB, Sarwer DB. Childhood sexual abuse and obesity. Obes Rev. 2004;5(3):129–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2004.00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noll JG, Zeller MH, Trickett PK, Putnam FW. Obesity risk for female victims of childhood sexual abuse: a prospective study. Pediatrics. 2007;120(1):e61–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Felitti VJ. Long-term medical consequences of incest, rape, and molestation. South Med J. 1991;84(3):328–31. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199103000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Felitti VJ. Adverse childhood experiences and adult health. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9(3):131–2. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.King TK, Clark MM, Pera V. History of sexual abuse and obesity treatment outcome. Addict Behav. 1996;21(3):283–90. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.US Department of Health and Human Services, A.o.C., Youth and Families; G.P. Office, editor. Child Maltreatment 2007. Washington D.C.: US: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dube SR, Cook ML, Edwards VJ. Health-related outcomes of adverse childhood experiences in Texas, 2002. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7(3):A52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gunnar MR, Morison SJ, Chisholm K, Schuder M. Salivary cortisol levels in children adopted from romanian orphanages. Dev Psychopathol. 2001;13(3):611–28. doi: 10.1017/s095457940100311x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hart J, Gunnar MR, Ccchetti D. Altered neuroendocrine activity in maltreated children related to symptoms of depression. Dev Psychopathol. 1996;8:201–214. [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Bellis MD, Lefter L, Trickett PK, Putnam FW., Jr Urinary catecholamine excretion in sexually abused girls. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33(3):320–7. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199403000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grilo CM, Masheb RM. Childhood psychological, physical, and sexual maltreatment in outpatients with binge eating disorder: frequency and associations with gender, obesity, and eating-related psychopathology. Obes Res. 2001;9(5):320–5. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trickett PK, Noll JG, Reiffman A, Putnam FW. Variants of intrafamilial sexual abuse experience: Implications for short- and long-term development. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13(4):1001–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mason SM, Flint AJ, Field AE, Austin SB, Rich-Edwards JW. Abuse victimization in childhood or adolescence and risk of food addiction in adult women. Obesity. 2013 doi: 10.1002/oby.20500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gunstad J, Paul RH, Spitznagel MB, et al. Exposure to early life trauma is associated with adult obesity. Psychiatry research. 2006;142(1):31–7. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boynton-Jarrett R, Rosenberg L, Palmer JR, Boggs DA, Wise LA. Child and adolescent abuse in relation to obesity in adulthood: the Black Women’s Health Study. Pediatrics. 2012;130(2):245–53. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller-Perrin CL, Perrin RD. Child Maltreatment: An Introduction. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chartier MJ, Walker JR, Naimark B. Health risk behaviors and mental health problems as mediators of the relationship between childhood abuse and adult health. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(5):847–54. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.122408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flaherty EG, Thompson R, Litrownik AJ, et al. Adverse childhood exposures and reported child health at age 12. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9(3):150–6. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hahm HC, Lee Y, Ozonoff A, Van Wert MJ. The impact of multiple types of child maltreatment on subsequent risk behaviors among women during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood. J Youth Adolesc. 2010;39(5):528–40. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9490-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hornor G. Child sexual abuse: consequences and implications. J Pediatr Health Care. 2010;24(6):358–64. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson JG, Cohen P, Kasen S, Brook JS. Childhood adversities associated with risk for eating disorders or weight problems during adolescence or early adulthood. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(3):394–400. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.3.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Child Maltreatment. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; Atlanta: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harris K. Design Features of Add Health. 2011 cited 2012 09/07/12 ; Available from: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/data/guides/design%20paper%20WI-IV.pdf.

- 45.Miller WC, Ford CA, Morris M, et al. Prevalence of chlamydial and gonococcal infections among young adults in the United States. JAMA. 2004;291(18):2229–36. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.18.2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ogden CL, Kuczmarski RJ, Flegal KM, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts for the United States: improvements to the 1977 National Center for Health Statistics version. Pediatrics. 2002;109(1):45–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Flegal KM, Wei R, Ogden CL, Freedman DS, Johnson CL, Curtin LR. Characterizing extreme values of body mass index-for-age by using the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(5):1314–20. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cole TJ, Lobstein T. Extended international (IOTF) body mass index cutoffs for thinness, overweight and obesity. Pediatr Obes. 2012;7(4):284–94. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.WHO; W.H. Organization, editor. Expert Committee on Physical Status. Geneva, Switzerland: 1995. Physical Status: The Use and Interpretation of Anthropometry. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Straus MA, Hamby SL, Finkelhor D, Moore DW, Runyan D. Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales: development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child abuse & neglect. 1998;22(4):249–70. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Widom CS, Morris S. Accuracy of adult recollections of childhood victimization, Part 2: Childhood sexual abuseP. sychological. Assessment. 1997;9(1):34–46. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Widom CS, Sheppard RL. Accuracy of adult recollections of childhood victimization: Part 1. Childhood physical abuse. Psychological Assessment. 1996;8(4):412–421. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Knüppel S, Stang A. DAG program: identifying minimal sufficient adjustment sets. Epidemiology. 2010;21(1):159. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c307ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Greenland S, Pearl J, Robins JM. Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology. 1999;10(1):37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.The NS, Suchindran C, North KE, Popkin BM, Gordon-Larsen P. Association of adolescent obesity with risk of severe obesity in adulthood. JAMA. 2010;304(18):2042–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.KJRGS, LTL . Modern Epidemiology. 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Breslow N. Design and analysis of case-control studies. Annu Rev Public Health. 1982;3:29–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.03.050182.000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kleinbaum DG, Azhar N, Kupper LL, Muller KE. Applied regression analysis and other multivariable methods. 3. Pacific Grove, CA: Duxbury Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tourangeau R, Shin HC. National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Grand Sample Weight. 1999 cited 2011 8/16/11; Available from: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/data/guides/weights.pdf/view.

- 60.Chantala K, Kalsbeek D, Andrace E. Non-response in Wave III of the Add Health Study. 2011 cited 2011 8/16/11; Available from: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/data/guides/W3nonres.pdf/

- 61.Gordon-Larsen P, Adair LS, Nelson MC, Popkin BM. Five-year obesity incidence in the transition period between adolescence and adulthood: the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(3):569–75. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.3.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Greenland S. Tests for interaction in epidemiologic studies: a review and a study of power. Stat Med. 1983;2(2):243–51. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780020219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hausman J, Taylor W. A generalized specification test. Economics Letters. 1981;8:239–245. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pope HG, Jr, Hudson JI. Can memories of childhood sexual abuse be repressed? Psychol Med. 1995;25(1):121–6. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700028142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.VJE, Anda RF, Nordenberg DF, Felittie VJ, Williamson DF, Wright JA. Bias assessment for child abuse survey: factors affecting probability of response to a survey about childhood abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2001;25(2):307–312. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van den Berg PA, Mond J, Eisenberg M, Ackard D, Neumark-Sztainer D. The link between body dissatisfaction and self-esteem in adolescents: similarities across gender, age, weight status, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. The Journal of adolescent health: official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2010;47(3):290–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lynch E, Liu K, Spring B, Hankinson A, Wei GS, Greenland P. Association of ethnicity and socioeconomic status with judgments of body size: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(9):1055–62. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Snooks MK, Hall SK. Relationship of body size, body image, and self-esteem in African American, European American, and Mexican American middle-class women. Health Care Women Int. 2002;23(5):460–6. doi: 10.1080/073993302760190065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gorey KM, Leslie DR. The prevalence of child sexual abuse: integrative review adjustment for potential response and measurement biases. Child abuse & neglect. 1997;21(4):391–8. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(96)00180-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Goldman J, Salus MK, Wolcott D, Kennedy KY. C.s.B. Office on Child Abuse and Neglect, editor. A Coordinated Response to Child Abuse and Neglect: The Foundation for Practice. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;307(5):491–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bouret SG, Draper SJ, Simerly RB. Trophic action of leptin on hypothalamic neurons that regulate feeding. Science. 2004;304(5667):108–10. doi: 10.1126/science.1095004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mainardi M, Scabia G, Vottari T, et al. A sensitive period for environmental regulation of eating behavior and leptin sensitivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(38):16673–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911832107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Remmers F, Delemarre-van de Waal HA. Developmental programming of energy balance and its hypothalamic regulation. Endocrine reviews. 2011;32(2):272–311. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kaufman D, Banerji MA, Shorman I, et al. Early-life stress and the development of obesity and insulin resistance in juvenile bonnet macaques. Diabetes. 2007;56(5):1382–6. doi: 10.2337/db06-1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Conti G, Hansman C, Heckman JJ, Novak MF, Ruggiero A, Suomi SJ. Primate evidence on the late health effects of early-life adversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(23):8866–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205340109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chapman DP, Liu Y, Presley-Cantrell LR, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and frequent insufficient sleep in 5 U.S. States, 2009: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Min MO, Minnes S, Kim H, Singer LT. Pathways linking childhood maltreatment and adult physical health. Child abuse & neglect. 2013;37(6):361–73. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Widom CS, Czaja SJ, Bentley T, Johnson MS. A prospective investigation of physical health outcomes in abused and neglected children: new findings from a 30-year follow-up. American journal of public health. 2012;102(6):1135–44. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Christian CW, Schwarz DF. Child maltreatment and the transition to adult-based medical and mental health care. Pediatrics. 2011;127(1):139–45. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]