Abstract

Recently a novel class of chiral stationary phases (CSPs) based on cyclofructan (CF) has been developed. Cyclofructans are cyclic oligosaccharides that possess a crown ether core and pendent fructofuranose moieties. Herein, we evaluate the applicability of these novel CSPs for the enantiomeric separation of chiral illicit drugs and controlled substances directly without any derivatization. A set of 20 racemic compounds were used to evaluate these columns including 8 primary amines, 5 secondary amines, and 7 tertiary amines. Of the new cyclofructan based LARIHC columns, 14 enantiomeric separations were obtained including seven baseline and seven partial separations. The LARIHC CF6-P column proved to be the most useful in separating illicit drugs and controlled substances accounting for 11 of the 14 optimized separations. The polar organic mode containing small amounts of methanol in acetonitrile was the most useful solvent system for the LARIHC CF6-P CSP. Furthermore, the LARIHC CF7-DMP CSP proved to be valuable for the separation of the tested chiral drugs resulting in four of the optimized enantiomeric separations, whereas the CF6-RN did not yield any optimum separations. The broad selectivity of the LARIHC CF7-DMP CSP is evident as it separated primary, secondary and tertiary amine containing chiral drugs. The compounds that were partially or un-separated using the cyclofructan based columns were screened with a Cyclobond I 2000 RSP column. This CSP provided three baseline and six partial separations.

Introduction

Many illicit drugs and controlled substances are chiral and occur as enantiomers. Enantiomers can have different pharmacological and/or psychotropic activities. They can have one or more chiral centers, and one enantiomer of particular drug can be accepted for its medicinal usage while the other enantiomer may be a drug of abuse.[1-4] For example (S)-(+) methamphetamine is a widely abused, DEA schedule II, controlled substance whereas (R)-(−) methamphetamine is used in an over-the-counter nasal decongestant.[1, 5-7] Amphetamine is one of the most frequently abused drugs and its behavioral stimulant effects are mediated primarily through dopamine and depend on the dopamine transporter. At higher doses, (S)-(+)-amphetamine has stimulant properties that are stronger than R-(−)-amphetamine, and increases dopamine activity. Hence, (S)-(+)-amphetamine is several times more potent than the R-(−)-enantiomer in eliciting central nervous system effects.[3, 7-13] Also, the R-(−)-amphetamine produces more cardiovascular and peripheral effects than the (S)-(+)-amphetamine.[4] Both methamphetamine and amphetamine are basic compounds that stimulate the central nervous system and provide increased alertness, diminished fatigue, and cardiovascular activation etc.

In sports, drugs of abuse can provide unfair advantages, thus they are prohibited by the World Anti-Doping Agency.[14] These performance enhancing drugs can be produced as racemates or enantiomerically enriched compounds depending on the method of synthesis and purification. Thus the ability to separate and determine the enantiomeric ratios of drugs provides valuable intelligence for determining drug potency and for tracking its synthetic origin.[15-18] For example, the enantiomeric ratio of methamphetamine is closely related with the optical activity of its precursors (most commonly, ephedrine or pseudoephedrine).[17, 18] This information is important and can be utilized for the investigation of manufacturing sources of methamphetamine starting materials. Lee et al. investigated the enantiomeric ratios of 433 crystalline methamphetamine samples seized in Korea from 1994 to 2005. The methamphetamine samples were derivatized with (S)-(+)-α-methoxy-α-(trifluoromethyl)phenylacetyl chloride and then analyzed by GC-MS in SIM mode. They found that, most of the seizures were the pure S(+) enantiomer, but 21 % contained the R(−) enantiomer above the 1 % level and concluded that alternative precursor sources may have been used in these cases. To obtain this information, rapid and effective analytical techniques are required. In addition, separating enantiomers of these types of drugs is important for pharmacological, toxicological, and forensic studies, as well as production quality control.

There have been reports on a variety of analytical methodologies for separating enantiomers of illicit drugs and controlled substances, including: gas chromatography (GC),[1, 19-21] high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC),[1, 22-28] capillary electrophoresis (CE)[14, 29], GC/MS,[30-32] LC/MS,[33-36] and CE-ESI-MS.[37] One approach may be superior to another depending on the goal of the investigator and the nature of the problems to be solved. Clearly, one method may be useful for biological assays while another approach is better suited for forensic assays or quality control of pharmaceutical products. For example, CE may be the best approach for the rapid analysis of pure compounds; however GC and LC may be more appropriate when analyzing low levels of a compound in physiological samples. Usually, GC using derivatized cyclodextrin chiral stationary phases is a highly effective approach in terms of efficiency, sensitivity and peak capacity for separating these enantiomers.[1, 38] However in the case of physiological and biological studies on extremely small amounts of analyte, sensitivity and isolation from a complex biological matrix is problematic. Often, a prederivatization step is necessary in order to reach sufficiently low limits of detection in both GC and HPLC techniques.[23]

In this work, we report the enantiomeric separation of 20 racemic illicit drugs and controlled substances using new cyclofructan based chiral stationary phases and without the use of derivatizing agents. Cyclofructans are cyclic oligosaccharides that possess a crown ether core and pendent fructofuranose moieties. Aliphatic and aromatic functionalized cyclofructan 6 and 7 have been recently introduced as novel chiral selectors[39-41] while native and sulfonated cyclofructan 6 were introduced as hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatographic stationary phases.[42, 43] The chiral stationary phases based on aliphatic and aromatic functionalized cyclofructan 6 and 7 possess unique enantiomeric selectivities for chiral primary amines (alkyl derivatives of cyclofructan) and broad selectivities (aromatic derivatives of cyclofructan) for a wide variety of all other racemates. Herein, the applicability of these new CSPs for the enantiomeric separation of selected chiral illicit drugs and controlled substances is evaluated. Also, the Cyclobond I 2000 RSP column[44] was evaluated for the compounds that were not adequately separated using the cyclofructan based columns.

Experimental

Materials

LARIHC CF6-P, LARIHC CF6-RN and LARIHC CF7-DMP columns (25 cm × 0.46 cm (i.d)) were obtained from AZYP, LLC. (Arlington, TX, USA). The Cyclobond I 2000 RSP column was obtained from Supelco (Bellefonte, PA, USA). All the analytes were purchased as racemates from Cerilliant Corporation (Round Rock, TX, USA) with the exception of cathinone and pseudoephedrine which were obtained as pure enantiomers and mixed together to produce racemates. Acetonitrile (ACN), 2-propanol (IPA), n-heptane, ethanol (EtOH), and methanol (MeOH) of HPLC grade were obtained from EMD (Gibbstown, NJ). Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), acetic acid (AA), triethylamine (TEA), sodium carbonate and dichloromethane were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO,USA). Water was purified by a Milli-Q water purification system (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA).

Chromatographic Conditions

An Agilent 1100 HPLC (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) was used in this study. It consisted of a 1200 diode array detector, autosampler and quaternary pump. All separations were carried out at room temperature (20 °C) unless stated otherwise. For all HPLC experiments, the injection volume was 5 μL and the flow rate was 1.0 mL/min in isocratic mode. The UV wavelengths 195, 210, 254 and 280 nm were employed for detection. All analytes were dissolved in methanol or methanol/water mixtures. The mobile phase was degassed by ultrasonication under vacuum for 5min. Each sample was analyzed in duplicate.

Three operation modes (the normal phase, polar organic mode, and reversed phase) were tested. In the normal phase, heptane with ethanol or isopropanol was used as the mobile phase. In some cases, TFA and TEA were used as additives to optimize/improve separations. The mobile phase for the polar organic mode was composed of acetonitrile/methanol and small amounts of acetic acid and triethylamine. Water/acetonitrile or acetonitrile/triethylammonium acetate buffer (0.5 %, pH 4-5) was used as the mobile phase in the reversed phase. The “dead time” t0 was determined by the peak of the refractive index change due to the unretained sample solvent. Retention factors (k) were calculated using k = (tr-t0)/t0, where tr is the retention time of the first peak and t0 is the dead time of the column. Also, selectivity was calculated using α = k2/k1 where, k2 and k1 are retention factors of the first and second peaks respectively.

Results and Discussion

Enantiomeric separations of illicit drugs and controlled substances on LARIHC chiral stationary phases (CSPs)

Previous studies showed that LARIHC CF6-P (isopropyl-carbamate cyclofructan 6, LARIHC CF6-RN (R-naphthylethyl-carbamate cyclofructan 6) and LARIHC CF7-DMP (dimethylphenyl-carbamate cyclofructan 7) columns provide excellent selectivities for racemic compounds containing different functionalities.[39-41] In general, the LARIHC CF6-P showed unique selectivity and broad applicability for racemates containing primary amines[40] while LARIHC CF6-RN and LARIHC CF7-DMP provided enantioselectivity toward a broad range of compounds, including chiral acids, amines, metal complexes, and neutral compounds. [39,41] Considering the ubiquity of amine groups in drugs of abuse, the current study focuses on a systematic chromatographic evaluation of these chiral stationary phases, mainly for chiral drugs containing amines. A set of 20 racemic compounds were used to evaluate these columns including 8 primary amines, 5 secondary amines, and 7 tertiary amines. (structures shown in Tables 1 and 4)

Table 1.

Chromatographic data of chiral illicit drugs and controlled substances separated on the LARIHC CF6-P and LARIHC CF7-DMP columns in the optimized conditions.

| Drug | Structure | CSP | Mobile Phase | rt1/min | rt2/min | α | Rs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | Lysergic acid diethylamide (6aR,9R/6aS,9S)-9,10-Didehydro-N,N-diethyl-6-methylergoline-8β-carboxamide |

|

LARIHC CF6-P | 90ACN/10MeOH/0.3AA/0.2TEA | 59.1 | 67.5 | 1.15 | 2.5 |

| (2) | Stanozolol (1S,3aS,3bR,5aS,10aS,10bS,12aS/1 R,3aR,3bS,5aR,10aR10bR,12aR)- 5α,17β-17-Methyl-2'H-androst-2-eno[3,2-c]pyrazol- 17-ol |

|

LARIHC CF6-P | 80HEP/20EtOH/0.1TFA | 24.0 | 34.7 | 1.51 | 2.0 |

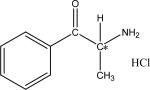

| (3) | Cathinone HCl (R/S)-2-Amino-1 -phenyl-1 -propanone hydrochloride |

|

LARIHC CF6-P | 70HEP/30EtOH/0.1TFA | 50.7 | 55.0 | 1.09 | 1.5 |

| (4) | (R/S)-3,4-Methylenedioxyphenyl-2-butanamine hydrochloride |

|

LARIHC CF6-P | 60ACN/40MeOH/0.3AA/0.2TEA | 9.9 | 10.5 | 1.08 | 1.5 |

| (5) | Phenylpropanolamine (1R,2S/1S,2R)-α-Hydroxy-β- aminopropylbenzene hydrochloride |

|

LARIHC CF6-P | 60ACN/40MeOH/0.3AA/0.2TEA | 13.8 | 15.0 | 1.08 | 1.5 |

| (6) | Methadone (R/S)-6-Dimethylamino-4,4- diphenyl-3 -heptanone |

|

LARIHC CF6-P | 85ACN/15MeOH/0.3AA/0.2TEA | 16.5 | 18.2 | 1.13 | 1.3 |

| (7) | MDA (R/S)-3,4- Methylenedioxyamphetamine |

|

LARIHC CF6-P | 80ACN/20MeOH/0.3AA/0.2TEA | 46.5 | 48.7 | 1.05 | 1.3 |

| (8) | Venlafaxine (R/S)- 1-[2-(dimethylamino)-1 -(4- methoxyphenyl)ethyl]cyclohexanol hydrochloride |

|

LARIHC CF6-P | 80ACN/20MeOH/0.3AA/0.2TEA | 9.6 | 9.9 | 1.05 | 1.0 |

| (9) | (R/S)-p-Methoxyamphetamine hydrochloride |

|

LARIHC CF6-P | 80ACN/20MeOH/0.3AA/0.2TEA | 45.6 | 47.7 | 1.02 | 0.8 |

| (10) | Aminorex (R/S)-4,5-Dihydro-5-phenyl-2- oxazolamine |

|

LARIHC CF6-P | 80ACN/20MeOH/0.3AA/0.2TEA | 13.8 | 14.1 | 1.03 | 0.6 |

| (11) | Amphetamine (R/S)-1-Phenyl-2- aminopropane |

|

LARIHC CF6-P | 80ACN/20MeOH/0.3AA/0.2TEA | 44.1 | 44.5 | 1.01 | 0.4 |

| (12) | Hydrocodone (5R,9R,13S,14R/6R,9S,13R14 S)-4,5-Epoxy-3 -methoxy-17- methylmorphinan-6-one |

|

LARIHC CF6-P | 80ACN/20MeOH/0.3AA/0.2TEA | 11.1 | 11.3 | 1.03 | 0.5 |

| (13) | (R/S)-Clenbuterol |

|

LARIHC CF7- DMP | 80Hep/20EtOH/0.1TFA | 12.9 | 14.8 | 1.19 | 2.0 |

| (14) | Temazepam (R/S)-7-Chloro-1,3-dihydro-3-hyd roxy-1 -methyl-5-phenyl-2H-1,4- benzodiazepine-2-one |

|

LARIHC CF7- DMP | 80Hep/20EtOH/0.1TFA | 13.5 | 14.6 | 1.10 | 1.8 |

*Marks a stereogenic center. For the possible enantiomeric configurations about these centers, refer to the description in the drug name column.

Table 4.

Chromatographic data of chiral illicit drugs and controlled substances separated on the Cyclobond I 2000 RSP column the optimized condition.

| Drug | Structure | Mobile Phase | rt1/min | rt2/min | α | Rs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Pseudoephedrine (1S,2S/1R2R)-1-(methylamino)ethyl- benzenemethanol |

|

95 (0.5 %TEAA, pH=4.2)/2.5 MeOH/2.5 ACN | 7.5 | 8.4 | 1.20 | 2.0 |

| (2) Methadone (R/S)-6-Dimethylamino-4,4-diphenyl-3- heptanone |

|

95 (0.5 %TEAA, pH=4.2)/ 5 % MeOH | 14.8 | 18.1 | 1.28 | 2.0 |

| (3) Methylephedrine (1R,2S/1S,2R)-a-1-(Dimethylamino)ethyl-benzenemethanol |

|

99 (0.5 % TEAA pH=4.2)/ 0.5 MeOH/0.5 ACN | 6.0 | 6.4 | 1.15 | 1.5 |

| (5) 3,4-Methylenedioxyethylamphetamine (R/S)-N-Ethyl-3,4- methylenedioxyamphetamine |

|

98 (0.5 % TEAA pH=4.2)/ 1 MeOH/1ACN | 24.0 | 26.1 | 1.10 | 1.3 |

| (6) 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (R/S)-N-a-Dimethyl-1,3-benzodioxole-5- ethanamine |

|

95 (0.5 % TEAA pH=4.2)/2.5 MeOH/2.5 ACN | 13.5 | 14.3 | 1.08 | 1.3 |

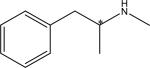

| (7) Methamphetamine (R/S)-1 -Phenyl-2-methylaminopropane |

|

99 (0.5 % TEAA pH=4.4)/0.5 MeOH/0.5 ACN | 10.8 | 11.4 | 1.08 | 1.0 |

| (8) (R/S)-p-Methoxymethamphetamine |

|

99 (0.5 % TEAA pH=4.1)/0.5 MeOH/0.5 ACN | 7.7 | 7.9 | 1.04 | 1.0 |

| (9) Amphetamine (R/S)-1 -Phenyl-2-aminopropane |

|

95 (0.5 % TEAA pH=4.4)/2.5 MeOH/2.5 ACN | 6.0 | 6.1 | 1.03 | 0.8 |

| (10) (R/S)-3,4-Methylenedioxyamphetamine |

|

99 (0.5 % TEAA pH=4.7)/ 1 MeOH | 8.5 | 8.7 | 1.06 | 1.0 |

| (11) Venlafaxine (R/S)-1 -[2-(dimethylamino)-1 -(4- methoxyphenyl)ethyl]cyclohexanol hydrochloride |

|

99 (0.5 % TEAA pH=4.7)/ 1 MeOH | 13.2 | 13.2 | 1.00 | No |

| (12) (R/S)-p-Methoxyamphetamine HCl |

|

99 (0.5 % TEAA pH=4.7)/ 1 MeOH | 6.8 | 7.0 | 1.04 | 0.7 |

| (13) Aminorex (R/S)-4,5-Dihydro-5-phenyl-2-oxazolamine |

|

99 (0.5 % TEAA pH=4.7)/ 1 MeOH | 6.4 | 6.6 | 1.04 | 0.8 |

*Marks a stereogenic center. For the possible enantiomeric configurations about these centers, refer to the description in the drug name column.

Table 1 lists the chromatographic data for all compounds separated by the LARIHC columns. The data in Table 1 indicates the number of successful separations for compounds containing primary amines on LARIHC CF6-P. This stationary phase provided better separations in the polar organic mode compared to the normal phase and reverse phase modes. Seven out of eight primary amine-containing drugs were separated on the LARIHC CF6-P stationary phase. Clearly, this stationary phase provides excellent enantioselectivity toward a variety of primary amines with diverse structures. However, clenbuterol which contains both a primary and a secondary amine was not separated using this stationary phase, while it was separated on the LARIHC CF7-DMP column. In the case of clenbuterol, the three point interaction required to achieve an enantiomeric separation using the LARIHC CF6-P column may be lacking. The primary amine group on clenbuterol is five atoms away from the stereogenic center and it has two neighboring Cl atoms. Hence, the steric hindrance of the Cl atoms may affect the ability for the primary amine to interact with the cyclofructan. Further, it is an aromatic amine, all of which render this particular primary amine containing drug unseparable in the polar organic mode. A thorough review of the literature reports of polar organic enantiomeric separations of primary amines reveals that no aniline type primary amine has ever been separated on LARIHC CF6-P.[40] Apparently, the LARIHC CF6-P column cannot separate primary amines when the amine is directly bonded to an aromatic ring.

Another interesting observation can be made involving the enantiomeric separation mechanism of LARIHC CF6-P CSP by analyzing the separation data (Table 1) for cathinone, phenylpropanolamine and amphetamine. As shown in Figure 1, cathinone contains a ketone group and phenylpropanolamine contains an alcohol group next to the sterogenic center. These additional hydrogen-bonding functional groups (ketone (hydrogen-bond acceptor) and alcohol (hydrogen-bond donor and acceptor)) contributed to the enantiomeric separation of cathinone (Rs = 1.1) and phenylpropanolamine (Rs = 1.5) in the polar organic mode. However, amphetamine does not possess a neighboring hydrogen-bonding group next to the stereogenic center, and it is only partially separated (shoulder (Rs = 0.4)) Thus, it appears that the beneficial hydrogen-bonding accepting contribution of the ketone in cathinone is not as great as the contribution of the hydroxy group (both hydrogen-bond accepter and donor) on phenylpropanolamine. Yet, it should be noted that primary amines without secondary hydrogen-bonding interactions have been separated on the LARIHC CF6-P.[40] Sun et.al reported the separation of α-methylbenzylamine with a Rs of 1.8.[40] Considering α-methylbenzylamine (Rs=1.8) only differs from amphetamine (Rs=0.4) by a single -CH2 group which separates the aromatic ring from the stereogenic center, it can be postulated that when there is no hydrogen-bonding group present in the chiral primary amine drug, a ring structure alpha to the stereogenic center is required for complete enantiomeric separation.

Figure 1.

Enantiomeric separation of (a) phenylpropanolamine, mobile phase: 60ACN/40MeOH/0.3AA/0.2TEA (b) cathinone, mobile phase: 90A/10M/0.3AA/0.2TEA (c) amphetamine, mobile phase: 80A/20M/0.3AA/0.2TEA on the LARIHC CF6-P column. UV detection at 254 nm, flow rate: 1 ml/min.

Representative chromatograms of the separation of phenylpropanolamine and 3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl)-2-butanamine hydrochloride and on the LARIHC CF6-P column are shown in Figure 2. Enantiomers of both drugs were separated in the polar organic mode with a resolution of 1.5. The LARIHC CF6-RN and LARIHC CF7-DMP columns were not as effective in separating these drugs. Pihlainen et. al studied the enantiomeric separation of similar controlled substances using vancomycin and native β-cyclodextrin CSPs.[33] They reported that β-cyclodextrin was more suitable than vancomycin for the separation of phenylethylamines yielding partial separations (Rs < 1.5) for amphetamine, methamphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine, p-methoxy-methamphetamine, p-methoxy-amphetamine and baseline separations (Rs ≥ 1.5) of 3,4-methylenedioxyethylamphetamine and 3,4-methylenedioxyethylmethamphetamine).[33] Phenylpropanolamine which could not be separated on the cyclodextrin column was baseline separated (Rs =1.5) on the LARIHC CF6-P column in the polar organic mode (Figure 1).

Figure 2.

Enantiomeric separation of (a) phenylpropanolamine and (b) 3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl-2-butanamine hydrochloride on the LARIHC CF6-P column. Mobile phase: 60ACN/40MeOH/0.3AA/0.2TEA, UV detection at 254 nm, flow rate:1 ml/min.

LARIHC CF6-P was also able to separate lysergic acid diethylamide, stanozolol, cathinone, 3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl-2-butanamine hydrochloride, methadone, phenylpropanolamine, 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine, venlafaxine, methoxyamphetamine, aminorex, amphetamine and hydrocodone, which cannot be effectively separated using the other stationary phases tested. Enantiomers of methadone and hydrocodone which contain tertiary amines were partially separated on LARIHC CF6-P (Table 1). The elution order of cathinone was investigated by injecting single enantiomers. The S(−) enantiomer eluted before the R(+) enantiomer.

Lysergic acid diethylamide, which contains both a tertiary and a secondary amine was baseline separated. Surprisingly, other analytes that contained only secondary amines were not separated on this stationary phase (e.g. 3,4-methylenedioxy methamphetamine and 3,4-methylenedioxyethylamphetamine). Overall, the LARIHC CF6-P exhibited enantioselectivity toward 77% of the chiral drugs evaluated, proving this stationary phase is broadly applicable for these types of compounds.

Among the aromatic derivatized-cyclofructan CSPs (LARIHC CF6-RN and LARIHC CF7-DMP), the LARIHC CF7-DMP CSP produced better separation results. Two of the optimized enantiomeric separations listed in Table 1 were obtained on the CF7-DMP phase, whereas the CF6-RN did not yield any optimum separations. Clenbuterol and temazepam were baseline separated on the LARIHC CF7-DMP phase. The broad selectivity of the LARIHC CF7-DMP CSP is evident as it showed enantioselectivity toward analytes which include secondary and tertiary amines. Compared to LARIHC CF6-P, the LARIHC CF7-DMP column is not as effective in separating the tested enantiomers, however, it demonstrates some complementary enantiomeric selectivities. For example, clenbuterol (CLB) which was well separated (Rs = 2.0) on the LARIHC CF7-DMP column with good selectivity (α = 1.19), was not separated on the LARIHC CF6-P or LARIHC CF6-RN columns.

The LARIHC CSPs showed better selectivity and resolution in the polar organic mode as compared to the reversed phase mode. Water in the reversed phase system may compete too effectively for hydrogen bonding sites on the chiral stationary phase, and thus it has a negative effect on the enantiomeric separation. The LARIHC CF6-P CSP performed best in the polar organic mode, while the LARIHC CF7-DMP CSP excelled under normal phase conditions. It is well-known that certain interactions such as π-π, n-π, dipolar, and hydrogen bonding interactions are enhanced in less polar solvents.[39] Thus, these must be the dominant associative interactions in these enantiomeric separations.

Effect of additives on mobile phase

Enantiomeric separations of amine-containing drugs were observed mainly in the polar organic mode. However, two analytes (stanozolol and cathinone) were separated more effectively on LARIHC CF6-P in the normal phase mode. Yet, higher efficiencies and better resolutions usually were observed in the polar organic mode which also offered short analysis times and better analyte solubility in the mobile phase. It has been shown that the highest enantioselectivity in the polar organic mode was obtained using the combination of triethylamine (TEA) and acetic acid (AA) as additives on CF6 based CSPs.[39-41] In order to evaluate the effects of the ratio of TEA and AA in the polar organic mode, the separation of 3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl-2-butanamine hydrochloride and phenylpropanolamine which are baseline separated in the mobile phase containing 60/40 ACN/MeOH were investigated. Table 2 shows the retention factors, selectivity and resolution with respect to different amounts of TEA and AA in the mobile phase (60/40 ACN/MeOH). These analytes were barely retained when no additives were used. Similar behavior was observed in the presence of 0.1 % (v/v) TEA where the analytes were in their neutral form. Also, more symmetrical peaks were observed when 0.1 % TEA was used, due to the interaction of TEA with free silanol groups. The retention time of these analytes increased dramatically when 0.1 % (v/v) AA was added to the mobile phase and the analytes were in their protonated form. Under these conditions tailing peaks were observed for most of the analytes, and neither resolution nor selectivity improved significantly. Retention times were decreased when equimolar amounts of TEA and AA were used. In this case the resolution improved significantly. When higher molar amounts of TEA were used higher efficiencies were observed. However, resolution and selectivity were maximized when higher amounts of AA were used compared to the TEA amount. Ultimately, the combination of 0.3% AA and 0.2% TEA (by volume) was determined to be the optimal polar organic mobile phase additive ratio.

Table 2.

Chromatographic data of 3,4-Methylenedioxyphenyl-2-butanamine hydrochloride and phenylpropanolamine on the LARIHC CF6-P column with different additive ratios. Mobile phase: 60ACN/40MeOH, UV detection at 254 nm, flow rate:1 ml/min

| Additive percentage (v/v) in the Mobile Phase | 3,4-Methylenedioxyphenyl- 2-butanamine hydrochloride | Phenylpropanolamine | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % TEA | % AA | rt1/min | rt2/min | α | Rs | rt1/min | rt2/min | α | Rs | |

| 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 1.00 | 0.0 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 1.02 | 0.5 |

| 2 | 0.10 | 0.0 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 1.00 | 0.4 | 6.0 | 6.1 | 1.02 | 0.6 |

| 3 | 0.0 | 0.10 | 19.3 | 20.2 | 1.06 | 0.8 | 24.0 | 25.7 | 1.08 | 0.8 |

| 4 | 0.36 | 0.15 | 7.3 | 7.5 | 1.05 | 1.3 | 10.3 | 10.6 | 1.05 | 1.4 |

| 5 | 0.89 | 0.10 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 1.03 | 1.2 | 7.3 | 7.4 | 1.02 | 1.2 |

| 6 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 9.9 | 10.5 | 1.08 | 1.5 | 13.9 | 14.9 | 1.08 | 1.5 |

Effects of mobile phase composition

It has been reported that the use of acetonitrile as a modifier produces the best resolution in the polar organic mode.[40] Therefore, the effect of the percentage of acetonitrile was examined. The percentage of acetonitrile was increased from 0% to 100% when the acid/base additive concentrations were kept constant (0.3% AA and 0.2 % TEA). Table 3 shows the retention factors, selectivity and resolution of two probe compounds (the same compounds used to investigate additive effects) with varying ACN concentration. Increasing the concentration of acetonitrile increases the retention considerably. This is due to the competition of the methanol with the analyte for hydrogen bonding sites on the stationary phase. Also, both selectivity and resolution were increased when increasing the acetonitrile concentration. The concentration of acetonitrile has a significant effect on the enantiomeric separation of the selected drugs. Therefore, optimization can be easily achieved by varying the ACN percentage.

Table 3.

Chromatographic data of 3,4-Methylenedioxyphenyl-2-butanamine hydrochloride and phenylpropanolamine on the LARIHC CF6-P column with different amounts of ACN in the mobile phase (0.3AA/0.2TEA), UV detection at 254 nm, flow rate:1 ml/min

| Mobile Phase (0.3AA/0.2TEA) | 3,4-Methylenedioxyphenyl- 2-butanamine hydrochloride | Phenylpropanolamine | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % ACN | % MeOH | rt1/min | rt2/min | α | Rs | rt1/min | rt2/min | α | Rs | |

| 1 | 10 | 90 | 4.5 | 4.6 | 1.04 | 1.2 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 1.04 | 1.2 |

| 2 | 20 | 80 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 1.04 | 1.3 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 1.04 | 1.3 |

| 3 | 40 | 60 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 1.05 | 1.4 | 7.2 | 7.4 | 1.06 | 1.4 |

| 4 | 60 | 40 | 9.9 | 10.5 | 1.08 | 1.5 | 13.9 | 14.9 | 1.08 | 1.5 |

| 5 | 85 | 15 | 13.6 | 14.6 | 1.09 | 2.0 | 21.2 | 23.0 | 1.10 | 2.0 |

Separations on Cyclobond I 2000 RSP column

The compounds that were partially or not separated using the cyclofructan based columns were screened with a Cyclobond I 2000 RSP column. Table 4 summarizes the optimized separations of the drugs on the Cyclobond column. Pseudoephedrine, methylephedrine, and methadone were baseline separated on this stationary phase (Rs ≥ 1.5). Also, the elution order of (±) pseudoephedrine was investigated by injecting single enantiomers. R,R(−)-pseudoephedrine eluted before the S,S(+)-pseudoephedrine. 3,4-methylenedioxyethylamphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxy methamphetamine, methamphetamine and methoxymethamphetamine were partially separated on this column whereas they were not separated on the LARIHC columns. However, 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine, venlafaxine andp-methoxyamphetamine HCl were partially separated on the both LARIHC CF6-P and Cyclobond I 2000 RSP columns and the LARIHC CF6-P column and provided better resolutions compared to the Cyclobond I 2000 RSP column.

Conclusion

In this study, three new cyclofructan based chiral selectors were evaluated for their ability to separate enantiomers of 22 chiral illicit drugs and controlled substances. Seven baseline separations and eight partial separations were obtained. The LARIHC CF6-P CSP resulted in the greatest number of enantiomeric separations and yielded resolution values as high as 2.5. In general, the polar organic mode was the most useful solvent system, were small amounts of methanol in acetonitrile was employed. It should be noted that this mobile phase composition is mass spectrometry compatible, thus these methods could be directly applied to LC-MS techniques which could be useful for sensitive drug detection in biological matrices.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the National Institute of Health SBIR program (GM-103359-02) for support of this work.

References

- 1.Armstrong DW, Rundlett KL, Nair UB, Reid GL. Enantioresolution of amphetamine, methamphetamine, and deprenyl (selegiline) by LC, GC, and CE. Curr. Sep. 1996;15:57. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oberlender R, Nichols DE. (+)-N-methyl-1-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-yl)-2-butanamine as a discriminative stimulus in studies of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-like behavioral activity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1990;255:1098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jenner P, Testa B. The influence of stereochemical factors on drug disposition. Drug Metab. Rev. 1973;2:117. doi: 10.3109/03602537409030008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berman SM, Kuczenski R, McCracken JT, London ED. Potential adverse effects of amphetamine treatment on brain and behavior: a review. Mol. Psychiatry. 2009;14:123. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee ED, Henion JD, Brunner CA, Wainer IW, Doyle TD, Gal J. High-performance liquid chromatographic chiral stationary phase separation with filament-on thermospray mass spectrometric identification of the enantiomer contaminant (S)-(+)-methamphetamine. Anal. Chem. 1986;58:1349. doi: 10.1021/ac00298a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall DA, Stanis JJ, Marquez Hector A, Gulley JM. A comparison of amphetamine- and methamphetamine-induced locomotor activity in rats: evidence for qualitative differences in behavior. Psychopharmacology (Berlin, Ger.) 2008;195:469. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0923-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuczenski R, Segal DS, Cho AK, Melega W. Hippocampus norepinephrine, caudate dopamine and serotonin, and behavioral responses to the stereoisomers of amphetamine and methamphetamine. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:1308. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-02-01308.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.North RB, Harik SI, Snyder SH. Amphetamine isomers: Influences on locomotor and stereotyped behavior of cats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1974;2:115. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(74)90143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sloviter RS, Damiano BP, Connor JD. Relative potency of amphetamine isomers in causing the serotonin behavioral syndrome in rats. Biol. Psychiatry. 1980;15:789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith EO, Byrd LD. d-amphetamine3induced changes in social interaction patterns. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1985;22:135. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(85)90496-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holmes JC, Rutledge CO. Effects of the d- and l-isomers of amphetamine on uptake, release and catabolism of norepinephrine, dopamine and 5-hydroxytryptamine in several regions of rat brain. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1976;25:447. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(76)90348-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gal J. Stereochemistry of metabolism of amphetamines: use of (−)-β±-methoxy-β±-(trifluoromethyl)phenylacetyl chloride for GLC resolution of chiral amines. J. Pharm. Sci. 1977;66:169. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600660209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewin AH, Miller GM, Gilmour B. Trace amine-associated receptor 1 is a stereoselective binding site for compounds in the amphetamine class. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011;19:7044. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mantim T, Nacapricha D, Wilairat P, Hauser PC. Enantiomeric separation of some common controlled stimulants by capillary electrophoresis with contactless conductivity detection. Electrophoresis. 2012;33:388. doi: 10.1002/elps.201100370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skinner HF. Methamphetamine synthesis via hydriodic acid/red phosphorus reduction of ephedrine. Forensic Sci. Int. 1990;48:123. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Woods RM, Breitbach ZS, Armstrong DW. 1,3-Dimethylamylamine (DMAA) in supplements and geranium products: natural or synthetic? Drug Test. Anal. 2012;4:986. doi: 10.1002/dta.1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee JS, Yang WK, Han EY, Lee SY, Park YH, Lim MA, Chung HS, Park JH. Monitoring precursor chemicals of methamphetamine through enantiomer profiling. Forensic Sci. Int. 2007;173:68. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plotka JM, Morrison C, Adam D, Biziuk M. Chiral analysis of chloro intermediates of methylamphetamine by one-dimensional and multidimentional NMR and GC/MS. Anal. Chem. 2012;84:5625. doi: 10.1021/ac300503g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morrison C, Smith FJ, Tomaszewski T, Stawiarska K, Biziuk M. Chiral gas chromatography as a tool for investigations into illicitly manufactured methylamphetamine. Chirality. 2011;23:519. doi: 10.1002/chir.20957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drake SJ, Morrison C, Smith F. Simultaneous chiral separation of methylamphetamine and common precursors using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Chirality. 2011;23:593. doi: 10.1002/chir.20977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin HL, Beesley TE. Enantiomeric separation of amphetamine and methamphetamine by capillary gas chromatography. Chromatographia. 1994;38:595. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohr S, Taschwer M, Schmid MG. Chiral Separation of Cathinone Derivatives Used as Recreational Drugs by HPLC-UV Using a CHIRALPAK AS-H Column as Stationary Phase. Chirality. 2012;24:486. doi: 10.1002/chir.22048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herraez-Hernandez R, Campins-Falco P, Verdu-Andres J. Enantiomeric separation of amphetamine and related compounds by liquid chromatography using precolumn derivatization with o-phthaldialdehyde. Chromatographia. 2002;56:559. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campins-Falco P, Verdu-Andres J, Herraez-Hernandez R. Separation of the enantiomers of primary and secondary amphetamines by liquid chromatography after derivatization with (−)-1-(9-fluorenyl)ethyl chloroformate. Chromatographia. 2003;57:309. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Makino Y, Ohta S, Hirobe M. Enantiomeric separation of amphetamine by high-performance liquid chromatography using chiral crown ether-coated reversed-phase packing: application to forensic analysis. Forensic Sci. Int. 1996;78:65. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lourenco TC, Bosio GC, Cassiano NM, Cass QB, Moreau RLM. Chiral separation of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) enantiomers using batch chromatography with peak shaving recycling and its effects on oxidative stress status in rat liver. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2013;73:13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2012.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guillarme D, Bonvin G, Badoud F, Schappler J, Rudaz S, Veuthey J. Fast chiral separation of drugs using columns packed with sub-2 μm particles and ultra-high pressure. Chirality. 2010;22:320. doi: 10.1002/chir.20745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rizzi AM, Hirz R, Cladrowa-Runge S, Jonsson H. Enantiomeric separation of amphetamine, methamphetamine and ring substituted amphetamines by means of a β2-cyclodextrin-chiral stationary phase. Chromatographia. 1994;39:131. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plotka JM, Biziuk M, Morrison C. Common methods for the chiral determination of amphetamine and related compounds II. Capillary electrophoresis and nuclear magnetic resonance. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 2012;31:23. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strano-Rossi S, Botre F, Bermejo AM, Tabernero MJ. A rapid method for the extraction, enantiomeric separation and quantification of amphetamines in hair. Forensic Sci. Int. 2009;193:95. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paul BD, Jemionek J, Lesser D, Jacobs A, Searles DA. Enantiomeric separation and quantitation of (±)-amphetamine, (±)-methamphetamine, (±)-MDA, (±)-MDMA, and (±)-MDEA in urine specimens by GC-EI-MS after derivatization with (R)-(−)- or (S)-(+)-methoxy-(trifluoromethy)phenylacetyl chloride (MTPA) J. Anal. Toxicol. 2004;28:449. doi: 10.1093/jat/28.6.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shin H, Donike M. Stereospecific Derivatization of Amphetamines, Phenol Alkylamines, and Hydroxyamines and Quantification of the Enantiomers by Capillary GLC/MS. Anal. Chem. 1996;68:3015. doi: 10.1021/ac960365v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pihlainen K, Kostiainen R. Effect of the eluent on enantiomer separation of controlled drugs by liquid chromatography-ultraviolet absorbance detection-electrospray ionisation tandem mass spectrometry using vancomycin and native β2-cyclodextrin chiral stationary phases. J. Chromatogr., A. 2004;1033:91. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2003.12.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pizzolato TM, Lopez Maria Jose d. A., Barcelo D. LC-based analysis of drugs of abuse and their metabolites in urine. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 2007;26:609. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nishida K, Itoh S, Inoue N, Kudo K, Ikeda N. High-Performance Liquid Chromatographic-Mass Spectrometric Determination of Methamphetamine and Amphetamine Enantiomers, Desmethylselegiline and Selegiline, in Hair Samples of Long-Term Methamphetamine Abusers or Selegiline Users. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2006;30:232. doi: 10.1093/jat/30.4.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thevis M, Thomas A, Beuck S, Butch A, Dvorak J, Schaenzer W. Does the analysis of the enantiomeric composition of clenbuterol in human urine enable the differentiation of illicit clenbuterol administration from food contamination in sports drug testing? Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2013;27:507. doi: 10.1002/rcm.6485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iwata YT, Kanamori T, Ohmae Y, Tsujikawa K, Inoue H, Kishi T. Chiral analysis of amphetamine-type stimulants using reversed-polarity capillary electrophoresis/positive ion electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Electrophoresis. 2003;24:1770. doi: 10.1002/elps.200305431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Armstrong DW, Li W, Pitha J. Reversing enantioselectivity in capillary gas chromatography with polar and nonpolar cyclodextrin derivative phases. Anal. Chem. 1990;62:214. doi: 10.1021/ac00201a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun P, Wang C, Breitbach ZS, Zhang Y, Armstrong DW. Development of new HPLC chiral stationary phases based on native and derivatized cyclofructans. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:10215. doi: 10.1021/ac902257a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun P, Armstrong DW. Effective enantiomeric separations of racemic primary amines by the isopropyl carbamate-cyclofructan6 chiral stationary phase. J. Chromatogr., A. 2010;1217:4904. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2010.04.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun P, Wang C, Padivitage N, Thilakarathna Lasanthi, Nanayakkara YS, Perera S, Qiu H, Zhang Y, Armstrong DW. Evaluation of aromatic-derivatized cyclofructans 6 and 7 as HPLC chiral selectors. Analyst. 2011;136:787. doi: 10.1039/c0an00653j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Padivitage NLT, Armstrong DW. Sulfonated cyclofructan 6 based stationary phase for hydrophilic interaction chromatography. J. Sep. Sci. 2011;34:1636. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201100121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qiu H, Loukotkova L, Sun P, Tesarova E, Bosakova Z, Armstrong DW. Cyclofructan 6 based stationary phases for hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr., A. 2011;1218:270. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2010.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stalcup AM, Chang SC, Armstrong DW, Pitha J. (S)-2-Hydroxypropyl-β2-cyclodextrin, a new chiral stationary phase for reversed-phase liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. 1990;513:181. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)89435-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]