Background: O-Mannosylation is a conserved, essential protein modification that is initiated in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER).

Results: Protein O-mannosyltransferases act at the translocon complex to modify proteins entering the ER.

Conclusion: Protein translocation into the ER, O-mannosylation, and N-glycosylation are coordinated processes.

Significance: Defining the mechanism of O-mannosylation is crucial to understand its diverse physiological roles for ER homeostasis.

Keywords: Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER), Glycosylation, Glycosyltransferases, Protein Translocation, Yeast, O-Mannosylation, OST, PMT

Abstract

O-Mannosylation and N-glycosylation are essential protein modifications that are initiated in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Protein translocation across the ER membrane and N-glycosylation are highly coordinated processes that take place at the translocon-oligosaccharyltransferase (OST) complex. In analogy, it was assumed that protein O-mannosyltransferases (PMTs) also act at the translocon, however, in recent years it turned out that prolonged ER residence allows O-mannosylation of un-/misfolded proteins or slow folding intermediates by Pmt1-Pmt2 complexes. Here, we reinvestigate protein O-mannosylation in the context of protein translocation. We demonstrate the association of Pmt1-Pmt2 with the OST, the trimeric Sec61, and the tetrameric Sec63 complex in vivo by co-immunoprecipitation. The coordinated interplay between PMTs and OST in vivo is further shown by a comprehensive mass spectrometry-based analysis of N-glycosylation site occupancy in pmtΔ mutants. In addition, we established a microsomal translation/translocation/O-mannosylation system. Using the serine/threonine-rich cell wall protein Ccw5 as a model, we show that PMTs efficiently mannosylate proteins during their translocation into microsomes. This in vitro system will help to unravel mechanistic differences between co- and post-translocational O-mannosylation.

Introduction

In eukaryotes, ∼25–35% of cellular proteins enter the secretory pathway during or after translation by traveling across the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)4 membrane through protein-conducting channels. During co-translational translocation the translating ribosome is targeted to the ER membrane in a signal recognition particle-dependent manner. There it engages with the channel enabling the growing polypeptide chain to be inserted directly into the translocon pore (1). In contrast, fully translated precursors are targeted to the translocon in a post-translational manner that requires chaperones and the membranous receptor Sec62 (1). In yeast, 20% of the secretome is predicted to reach the ER independent of the signal recognition particle (2). The two translocation pathways converge at the trimeric Sec61 complex, which forms an aqueous channel as polypeptides pass through. The yeast Sec61 translocon complex (TC) consists of the pore-forming Sec61 protein, Sbh1 and Sss1, which as such can mediate co-translational translocation. However, post-translational protein import requires a heptameric complex consisting of the trimeric Sec61 complex and the tetrameric Sec63 complex (Sec63, Sec62, Sec71, Sec72) (reviewed in Ref. 1). Nascent polypeptide chains arriving in the ER lumen via the TC are potentially processed by the signal peptidase complex and/or glycosylated, and soon begin to fold with the assistance of molecular chaperones and other folding factors.

N-Glycosylation and O-mannosylation of secretory and membrane proteins are evolutionary conserved, essential protein modifications in fungi and animals, which underlie the pathophysiology of severe congenital disorders with diverse clinical presentations in humans (3). Both, N-glycosylation of Asn residues of the sequon Asn-X-Thr/Ser and O-mannosylation of specific Ser and Thr residues are initiated at the ER where the synthesis of the polypeptide and the dolichol-linked donor saccharide, as well as the covalent coupling of glycan and polypeptide take place (reviewed in Ref. 3). In the absence of these types of glycosylation, ER homeostasis is severely affected (4, 5).

N-Glycosylation is initiated by a multisubunit membrane protein complex called oligosaccharyltransferase (OST). Yeast OST is composed of eight subunits (Ost1, Ost2, Ost3/Ost6, Ost4, Ost5, Stt3, Swp1, and Wbp1), which are assembled in the ER membrane in large heterooligomeric complexes alternatively containing Ost3 or Ost6 (reviewed in Ref. 6). It is well established that N-glycosylation can be temporally coupled to the protein translocation reaction to ensure the accessibility of glycosylation sites before the acceptor protein starts to fold, and direct interactions between OST and the TC have been demonstrated (reviewed in Ref. 7).

O-Mannosylation is initiated by a conserved family of integral ER-membrane proteins, the protein O-mannosyltransferases (PMTs). PMTs catalyze the transfer of a mannose residue from dolicholmonophosphate-activated mannose (Dol-P-Man) to Ser and Thr residues of mainly Ser/Thr-rich proteins (reviewed in Ref. 8). The PMT family is subdivided into the PMT1, PMT2, and PMT4 subfamilies, and complex formation between individual subfamily members is critical for mannosyltransferase activity (9). In baker's yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, O-mannosylation is predominantly catalyzed by heteromeric Pmt1-Pmt2 and homomeric Pmt4-Pmt4 complexes. These complexes mannosylate distinct protein substrates in vivo, even though the molecular basis of that specificity as well as general signature sequences for O-mannosylation are still unknown.

In baker's yeast, ∼250 secretory or membrane proteins contain Ser/Thr-rich clusters that can be substantially O-mannosylated and many of these proteins are modified in addition by N-linked glycans (10). For one of these, the cell wall protein Ccw5, it has even been shown that O-mannosylation precedes N-glycosylation (11), strongly suggesting that PMT complexes can act on protein chains while they enter the ER. These findings are consistent with the general assumption that O-mannosylation takes place on translocating polypeptide chains which, however, is based on a single study from the mid-1970s (12). The authors reported that in the presence of exogenous Dol-P-[14C]Man, regenerating yeast protoplasts incorporate nearly 20% of the radioactivity into polysomes and this material was largely released by β-elimination, a method to set free O-linked carbohydrates. However, in recent years it became clear that prolonged ER residence of fully translocated proteins allows modification of exposed O-mannosyl acceptor sites within un- and misfolded proteins by the Pmt1-Pmt2 complex (13–16), prompting us to revisit the process of protein O-mannosylation.

Here, we demonstrate that yeast PMTs have the capacity to mannosylate translocating nascent chains and associate with the co- and post-translational TC in vitro and in vivo. Our study brings forth an in vitro system that allows the analysis of O-mannosylation in the context of protein translocation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Yeast Strains and Plasmids

S. cerevisiae strains, oligonucleotides, and plasmids used in this study are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Yeast strains were grown and transformed under standard conditions. Temperature-sensitive (ts) mutant strains were grown at 20 °C (permissive temperature). Sequences of oligonucleotides are available on request.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| SEY6210 | MATα, his3-Δ200, leu2-3-112, lys2-801, trp1-Δ901, ura3-52, suc2-Δ9 | 51 |

| JHY1 | SEY6210 except PMT1-3xHA::kanMX6 | This study |

| MLY66 | JHY1 except TPI1p-ALG1-3xmyc::URA3 | This study |

| MLY67 | SEY6210 except pmt1-N390A/N513A/N743A-3xHA::kanMX6 | This study |

| pmt1 | SEY6210 except pmt1::HIS3 | 52 |

| pmt2 | SEY6210 except pmt2::LEU2 | 52 |

| pmt4 | SEY6210 except pmt4::TRP1 | 53 |

| STY100 | SEY6210 except pmt4Δ::kanMX6 | 54 |

| pmt1pmt2 | SEY6210 except pmt1::HIS3, pmt2::LEU2 | 52 |

| pmt1pmt4 | SEY6210 except pmt1::HIS3, pmt4::TRP1 | 55 |

| RSY023 | MATα, his4-593, ura3-52, suc2-432, sec53-6 | 56 |

| sec71Δ | BY4741 except sec71Δ::kanMX4 | EUROSCARF |

| sec72Δ | BY4741 except sec72Δ::kanMX4 | EUROSCARF |

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Description | Reference/Construction |

|---|---|---|

| pDJ100 | MF(ALPHA)1 in pSP65 | 57 |

| pEZ10 | SUC2_SP M21V,N23Q-CCW5-3xFLAG N114Q in pGEM-4Z | Mutation of 2nd initiation site M21V and N-glycosylation site N23Q by overlapping PCR of pML62 using oligos 1688, 1987, 1988, and 1989. |

| pFA6a-GFP-kanMX6 | ori, bla, GFP, kanMX6 | 58 |

| pGEM-4Z | ori, lacZ, bla, PSP6, PT7 | Promega |

| pJH24 | kanMX6 in pRS426-HA | kanMX6 cassette excised from pFA6a-GFP-kanMX6 using EcoRI/BglII, blunted and ligated into SacI linearized and blunted pRS426-HA. |

| pJH33 | YPS1 (-870/+213) in pJH33* | YPS1 (bp −870 to +213) from gDNA using oligos 985 and 986 via XhoI/SpeI in pJH33*. |

| pJH33* | YPS1 (from +214) in pRS426-HA | YPS1 (bp +214 to +1710) from gDNA using oligos 987 and 988 via NotI in pRS426-HA. |

| pJK4-B1 | PMT4-4xFLAG in pRS423 | 9 |

| pLF17 | SUC2_SP-CCW5-3xFLAG-NheI-STOP in pGEM-4Z | Insertion of NheI site between FLAG-tag and STOP codon by PCR of pML69 using oligos 1688 and 1948. PCR fragment cloned into pGEM-4Z. |

| pLF18 | SUC2_SP-CCW5-3xFLAG N114Q-NheI-STOP in pGEM-4Z | Insertion of NheI site between FLAG-tag and STOP codon by PCR of pML62 using oligos 1688 and 1948. PCR fragment cloned into pGEM-4Z. |

| pLF23 | SUC2_SP M21V,N23Q-CCW5-3xFLAG N114Q-NheI-STOP in pGEM-4Z | Replacement of BamHI/BglII fragment of pLF18 by the analog fragment in pEZ10 (M21V, N23Q). |

| pML35 | CCW5 in pGEM-4Z | CCW5 from gDNA using oligos 1529 and 1531 via EcoRI/PstI in pGEM-4Z. |

| pML52 | SUC2_SP-CCW5 in pGEM-4Z | SP_SUC2 from gDNA using oligos 1688 and 1689 and CCW5 w/o SP using oligos 1690 and 1691 from gDNA via BamHI/HindIII in pGEM-4Z. |

| pML60 | GAGA-3xFLAG-STOP in pGEM-4Z | FLAG-oligohybrid using oligos 1852 and 1853 via PstI/HindIII in pGEM-4Z. |

| pML61 | CCW5-3xFLAG N114Q in pGEM-4Z | Mutated CCW5 from pML35 using oligos 1850, 1843, 1842, and 1851 via BamHI/PstI in pML60. |

| pML68 | CCW5-3xFLAG in pGEM-4Z | CCW5 from pML35 using oligos 1850 and 1851 via BamHI/PstI in pML60. |

| pML69 | SUC2_SP-CCW5-3xFLAG in pGEM-4Z | SP_SUC2-CCW5 from pML52 using oligos 1688 and 1851 via BamHI/PstI in pML60. |

| pML70 | CCW5_Promoter (-891/-1) in pRS416 | Prom_CCW5 from gDNA using oligo1862 and 1863 via KpnI/BglII in pRS416 (KpnI/BamHI). |

| pML71 | CCW5_Terminator (+685/+714) in pML70 | Term_CCW5 from gDNA using oligos 1864 and 1865 via SpeI/SacI in pML70. |

| pML78 | CCW5-3xFLAG in pRS416 | CCW5-3xFLAG from pML68 via BamHI/HindIII in pML71. |

| pRS416 | ori, bla, CEN6/ARS4, URA3 | 59 |

| pRS426 | ori, bla, 2μ, URA3 | 60 |

| pRS416-HA | 3xHA-MPK1_Terminator in pRS416 | 3xHA-STOP-Term_MPK1 from pRS416-MID2HA using oligos 796 and 797 via SacI/XbaI in pRS416. |

| pRS426-HA | 3xHA-MPK1_Terminator in pRS426 | SacI/SpeI fragment of pRS416-HA cloned into pRS426. |

| pRS416-MID2HA | MID2-3xHA in pRS416 | 33 |

| pSB53 | PMT1 (from−343) in YEp352 | 31 |

| pSB56 | PMT1-6xHA in YEp352 | 19 |

| pSB63 | PMT1-6xHA Δ732-817 in YEp352 | 19 |

| pSB64 | PMT1-6xHA Δ617-817 in YEp352 | 19 |

| pSB101 | PMT1-6xHA Δ76-124 in YEp352 | 19 |

| pTi-ALGI-myc | ALG1-3xmyc in pTαO | 61 |

| pVG11 | PMT1-6xHA Δ203-259 in YEp352 | 19 |

| pVG13 | PMT1-6xHA Δ304-531 in YEp352 | 19 |

| pVG9 | PMT1-6xHA Δ161-211 in YEp352 | 19 |

| YEpGAP-myc-ALG7 | 3xmyc-ALG7 in YEpGAP | 62 |

To generate the C-terminal triple hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged Pmt1 construct (designated as Pmt1HA) wild-type (WT) yeast was transformed by homologous recombination with a 3xHA-kanMX6 integration cassette amplified by PCR on pJH24 using oligos 802 and 803. The recombination was confirmed by PCR and Western blot analysis using a monoclonal anti-HA antibody (Table 3). The resulting transformant was designated as JHY1. Linearization of the plasmid pTiALG1-myc with XhoI within the URA3 gene targets integration at the ura3-52 locus in JHY1. In the resulting strain MLY66, ALG1-myc3 expression was placed under the constitutive TPI1 promoter. To generate the N-glycosylation mutant of Pmt1HA (designated as Pmt1*HA), the pmt1Δ mutant strain was transformed with a PMT1-N390A/N513A/N743A-3xHA-kanMX6 integration cassette amplified by PCR on gDNA from JHY1 using oligos 1516 and 515. Mutated N-glycosylation sites were attained by site-directed mutagenesis via overlap extension PCR (17) using oligo pairs 122/123 (N390A), 1506/1507 (N513A), and 124/125 (N743A). The resulting transformant was designated as MLY67. Standard procedures were used for all DNA manipulations (18). All plasmids were validated by DNA sequencing.

TABLE 3.

Antibodies used in this study

| Name | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| α-Flag | Mouse, 1:10,000, M2 | Sigma |

| α-HA | Mouse, 1:10,000, 16B12 | Covance |

| α-MouseHRP | Rabbit, 1:5,000, HRP conjugate | Sigma |

| α-myc | Mouse, 1:10,000, 9E10 | Covance |

| α-Ost1 | Rabbit, 1:1,000 | 63 |

| α-Ost3 | Rabbit, 1:1,000 | 64 |

| α-Ost6 | Rabbit, 1:1,000 | 64 |

| α-Pmt1 | Rabbit, 1:2,500 | 65 |

| α-Pmt2 | Rabbit, 1:2,500 | 66 |

| α-Pmt4 | Rabbit, 1:250 | 9 |

| α-RabbitHRP | Goat, 1:5,000, HRP conjugate | Sigma |

| α-Sbh1 | Rabbit, 1:5,000 | 67 |

| α-Sec61 | Rabbit, 1:2,500 | 68 |

| α-Sec62 | Rabbit, 1:2,500 | 69 |

| α-Sec63 | Rabbit, 1:2,500 | 70 |

| α-Sec72 | Rabbit, 1:500 | 71 |

| α-Sss1 | Rabbit, 1:5,000 | 72 |

| α-Stt3 | Rabbit, 1:1,000 | A gift from Satoshi Yoshida |

| α-Wbp1 | Rabbit, 1:1,000 | 73 |

Preparation of Crude Membranes and Immunoprecipitation

Cell extracts were prepared from mid-log phase yeast cultures with glass beads in buffer A (50 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 200 mm NaOAc, 10% (v/v) glycerol) including protease inhibitors (19). Microsomal membranes were collected by differential centrifugation (100,000 × gav for 30 min). Crude membranes were solubilized in buffer A containing protease inhibitors and 0.75% (w/v) digitonin (Sigma) at a final protein concentration of 5 mg/ml. After incubation at 4 °C for 1 h, insoluble material was removed by centrifugation for 1 h at 100,000 × gav. Pmt1HA was immunoprecipitated with anti-HA magnetic beads (Miltenyi, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). After washing the beads extensively with buffer A containing 0.15% (w/v) digitonin, elution was performed with Laemmli sample buffer (20).

Electrophoresis and Western Blot

Samples were incubated at 50 °C for 10 min and resolved by SDS-PAGE using glycine or tricine polyacrylamide gels (20, 21). Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence using the Amersham Biosciences ECL system (GE Healthcare). Antibodies used in this study are listed in Table 3.

Preparation of Cell Lysates from sec Mutants

Following incubation at the non-permissive temperature (37 °C) cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 5% (v/v) glycerol) and broken with glass beads. Total membranes were isolated by differential centrifugation (100,000 × gav for 30 min). Total membranes were solubilized in lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors and 1% (v/v) Triton X-100. After incubation at 4 °C for 1 h insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 100,000 × gav for 1 h. Ccw5FLAG was immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG magnetic beads (Sigma). After washing the beads with lysis buffer containing 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, elution was performed with Laemmli sample buffer.

Preparation of Yeast Microsomes

Yeast microsomal membranes (yM) were isolated as described previously (22). The microsomal pellet was resuspended in buffer B88 to a final protein concentration of 10 mg/ml (=1 eq/μl) and stored in aliquots at −80 °C.

In Vitro Transcription, Translation, and Translocation

Synthesis of capped-mRNA by SP6 RNA polymerase (gift from B. Dobberstein) from linearized template plasmids was performed as described (23). Translation of mRNA (100 ng) was performed in 10-μl reactions containing 7 μl of rabbit reticulocyte lysate (Promega, Madison, WI) supplemented with 0.4 μl of [35S]methionine and cysteine (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). For translocation 1.2 eq of yeast microsomes were used. The reactions were incubated for 1 h at 30 °C. If necessary, translation was terminated using cycloheximide (Sigma) at a final concentration of 100 μm. Translocation was inhibited with 1% (v/v) Triton X-100. Post-translational protease protection assays were conducted as described previously (24). Translocated proteins were enriched using a sucrose cushion (25) or by immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG magnetic beads (Sigma).

Mannosidase and PMT Inhibitor Treatment

De-mannosylation was carried out using α(1-2,3,6)-mannosidase (ProZyme, Hayward, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions with the following modifications. Triton X-100 was added to a final concentration of 1% (v/v). Samples were incubated with 0.45–0.75 units of the enzyme for 2–24 h at 37 °C. PMT inhibitor OGT2468 (4) was added from a 20 mm stock solution prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide.

MS-based Identification of Glycopeptides from Covalently Linked Cell Wall Proteins

Glycopeptide profiling of cell wall glycoproteins of WT strain SEY6210 and isogenic pmt1, pmt2, pmt4, pmt1pmt2, and pmt1pmt4 mutant strains was performed as recently described (26). Uninterpreted MS/MS spectra were searched against the NCBI database (limited to S. cerevisiae with common contaminants) for glycopeptides containing one or more GlcNAc modifications and a corresponding number of N-glycosylation sequons using the Mascot software (Matrix Science). Glycopeptides identified exclusively in pmtΔ mutants were identified by inspection of the raw data using Xcalibur software (Thermo Scientific).

RESULTS

Pmt1-Pmt2 Complexes Are Associated with the Translocon Complex in Vivo

To further investigate whether the O-mannosylation machinery acts on protein chains entering the ER lumen, we first screened for associations between PMTs and the translocon. Here we focused on Pmt1-Pmt2 complexes, which represent the most abundant PMTs in S. cerevisiae (9, 27), and can also mannosylate un-/misfolded proteins (13–16). Suspected complexes were co-immunoprecipitated (co-IPed) under non-denaturating conditions from cell extracts, which is one of the most rigorous methods to demonstrate protein-protein interactions.

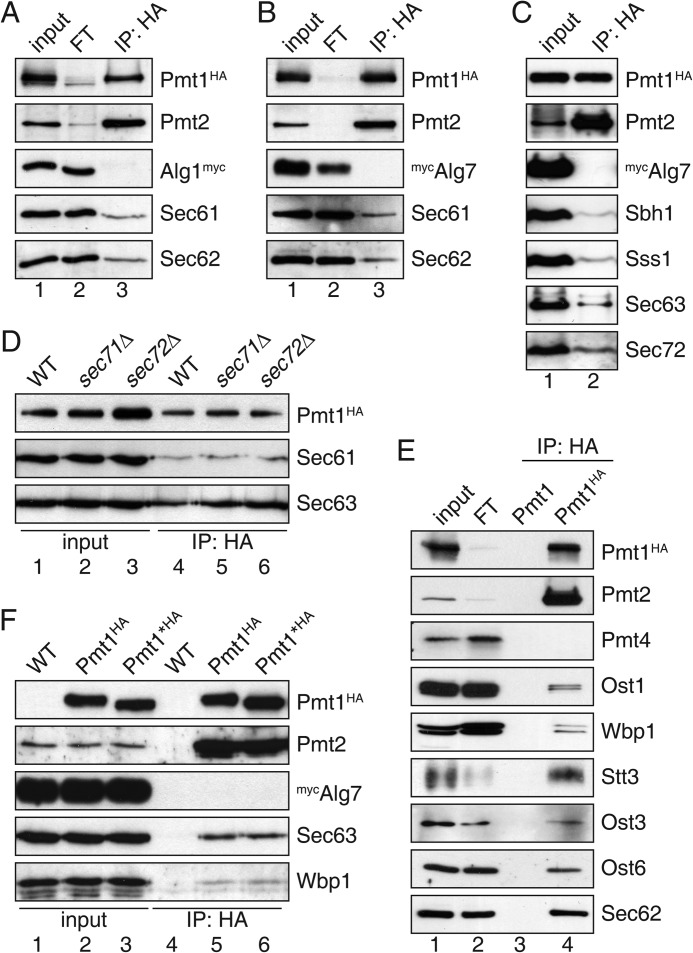

For co-IP experiments, yeast strain JHY1 was generated expressing genomically encoded Pmt1 tagged at its C terminus with the HA epitope. C-terminal HA tagging did not interfere with Pmt1 O-mannosyltransferase activity (19). Membrane proteins were solubilized under conditions (0.75% (w/v) digitonin) that were previously applied to isolate functional translocon and OST complexes (28). Digitonin-solubilized Pmt1HA-Pmt2 complexes were immunoprecipitated using an anti-HA affinity matrix (for details see “Experimental Procedures”) and further analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot. Under the applied conditions, Pmt1HA and its complex partner Pmt2 were quantitatively co-immunoprecipitated (Fig. 1, A, B, and E; compare input and flow-through), whereas Pmt4 was not associated with Pmt1HA (Fig. 1E). Furthermore, significant quantities of Sec61, the pore-forming subunit of the translocon (Figs. 1, A, B, and D, and 2B), and Sec62, an essential component of the tetrameric Sec63 complex (Fig. 1, A, B, and E), were found in the precipitate. Moreover, all further subunits of the Sec61 (Sbh1, Sss1) and Sec63 (Sec63, Sec72) complexes, for which specific antibodies were available, were present (Fig. 1, C, D, and F), demonstrating the association between Pmt1-Pmt2 and the co- and/or post-translational translocon. Deletion of the non-essential components of the Sec63 complex, namely Sec71 and Sec72, did not affect interactions between Pmt1HA and Sec61 or Sec63 (Fig. 1D), suggesting that neither Sec71 nor Sec72 are mediating Pmt1-translocon interactions. Our results were exceedingly reproducible and the detected interactions highly specific (Fig. 1). ER-resident glycosyltransferases such as Alg1 and Alg7 that feature single and multiple transmembrane spanning domains (TMDs), respectively (29, 30), were not detected in Pmt1HA precipitates, not even if overexpressed in strain JHY1 (Fig. 1, A–C and F). In contrast, all OST subunits for which specific antibodies were available (Ost1, Wbp1, Stt3, Ost3, and Ost6), were found in the Pmt1HA precipitate (Fig. 1E). Because Pmt1 itself is N-glycosylated in vivo (31) we wanted to rule out that association of OST with Pmt1HA is due to an enzyme-substrate interaction. Thus, we eliminated all N-glycosylation sites of Pmt1HA by changing asparagine to alanine (Pmt1*HA: N390A, N513A, and N743A). O-Mannosyltransferase activity of non-glycosylated Pmt1*HA was not changed when compared with the N-glycosylated protein (data not shown), revealing that N-glycosylation is not crucial for Pmt1 activity. Pmt1HA and Pmt1*HA equally co-immunoprecipitated with Wbp1 (Fig. 1F) confirming the OST-Pmt1 interaction even when Pmt1 is not an OST substrate. In summary, co-IP experiments strikingly revealed an association of Pmt1-Pmt2 complexes with the co- and/or post-translational translocation machinery as well as OST.

FIGURE 1.

Pmt1-Pmt2 complexes associate with the heptameric translocon and OST. Anti-HA immunoprecipitations were carried out on digitonin-solubilized total membranes. For interacting proteins 100% of the immunoprecipitated material (IP), and 10 (A–C and F), 5 (D), and 1% (E) of the input and flow-through (FT) material were resolved on SDS-polyacrylamide gels and analyzed by Western blotting. Blots were probed with antisera (see Table 3) as indicated. From the input material, ∼95% of Pmt2 and <5% of TC and OST subunits were co-precipitated with Pmt1HA. A–C, Pmt1HA was immunoprecipitated from strain JHY1 expressing fully functional Alg1myc or plasmid-encoded mycAlg7. D, IPs from extracts of the strains BY4741 (WT), sec71Δ, and sec72Δ expressing plasmid-encoded Pmt1HA are shown. E, anti-HA IPs were carried out on extracts of the strains SEY6210 (WT) and JHY1 (Pmt1HA). F, HA-tagged proteins were precipitated from strains SEY6210 (WT), JHY1 (Pmt1HA), and MLY67 (Pmt1*HA) expressing plasmid-encoded mycAlg7.

FIGURE 2.

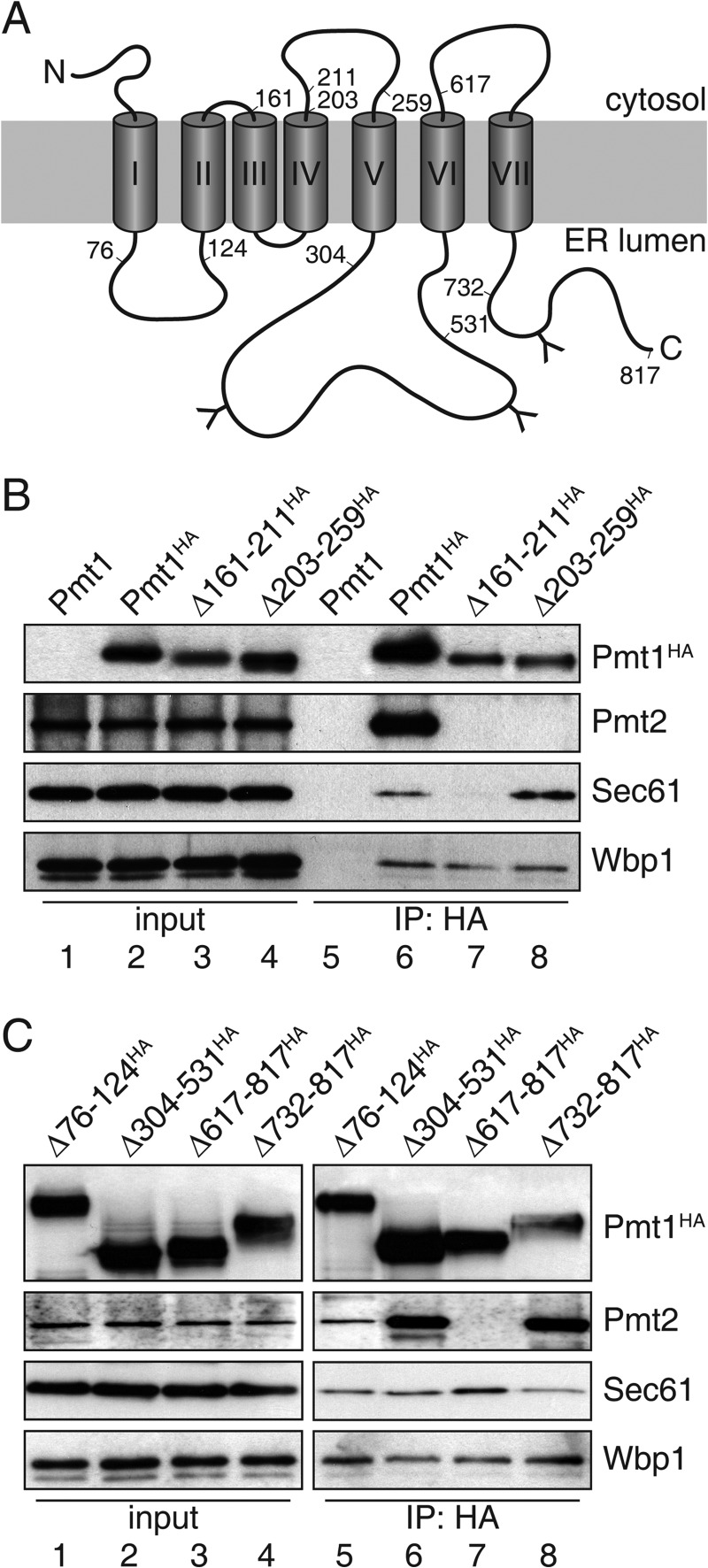

Pmt1 region TMDIII-IV is crucial for association with translocon. A, schematic presentation of Pmt1. Numbers (amino acids positions) indicate deleted regions within Pmt1. Transmembrane spans are depicted as gray cylinders (I–VII) and N-glycosylation sites are indicated by the letter Y. B and C, anti-HA immunoprecipitations were carried out on digitonin-solubilized total membranes from strain pmt1 expressing plasmid-encoded versions of Pmt1 (pSB53, pSB56, pVG9, pVG11, pSB101, pVG13, pSB64, and pSB63; see Table 2). Input lanes of interacting proteins represent 10% of the material used for the IP. Samples were resolved on SDS-polyacrylamide gels and analyzed by Western blotting. Blots were probed with antisera directed against HA-epitope (Pmt1HA), Pmt2, Sec61, or Wbp1 (see Table 3).

Pmt1 Region TMDIII-IV Is Crucial for Interaction with the Translocon

S. cerevisiae Pmt1 is a polytopic ER membrane protein with seven TMDs, a cytoplasmic N terminus, and a C terminus facing the ER lumen (31). To further characterize the interaction between Pmt1-Pmt2 and the TC, we analyzed previously established Pmt1 deletion mutants (19) as shown in Fig. 2A. These proteins are inactive with respect to Pmt1-Pmt2 O-mannosyltransferase activity but, are expressed at similar levels as WT Pmt1, reside within the ER, and show no major changes in overall membrane topology (19). Co-IP experiments showed that neither deletion of the ER-luminal Pmt1 loop5 region (Δ304–531HA) nor the C-terminal region (Δ732–817HA) affected interactions with Pmt2, Sec61, and Sec62 (Fig. 2C and data not shown). On the other hand, deletion of Pmt1 TMDIII and TMDIV (Δ161–211HA), the cytoplasmic loop4 region (Δ203–259HA), as well as TMDVII including the C terminus (Δ617–817HA) eliminated the association with Pmt2. However, only mutation Δ161–211HA prevented interaction with Sec61 and Sec62 (Fig. 2, B and C, and data not shown). In contrast, none of the tested Pmt1 mutants affected association with Wbp1 (Fig. 2, B and C). Therefore we conclude that Pmt1 interacts with the co- and/or post-translational translocon and OST independently from translocon-OST interactions and complex formation with Pmt2.

Monitoring O-Mannosylation in a Microsomal Translation/Translocation System

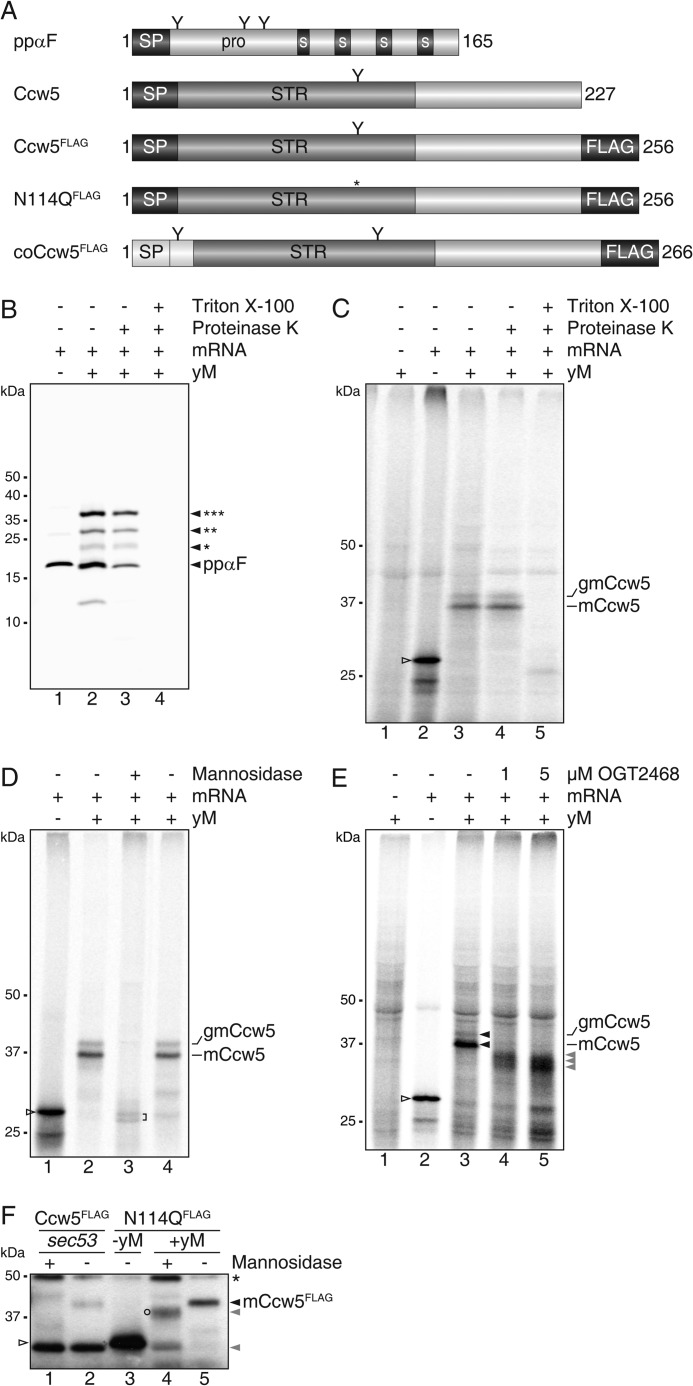

To further examine the association of PMTs with the co- as well as the post-translational translocon, we reconstituted the initial steps of secretory protein ER import, N-glycosylation and O-mannosylation in vitro. We devised a cell-free translation/translocation/glycosylation system in which reactions were started by mixing rabbit reticulocyte lysate, mRNA, [35S]Met/Cys, and yeast microsomes. After incubation for 1 h at 30 °C, non-translocated translation products were removed by proteinase K treatment. Thereafter, radiolabeled translocation products were resolved by SDS-PAGE and detected by autoradiography. In our in vitro system the well studied model protein prepro-α-factor (32) which contains three N-glycosylation sites (Fig. 3A, ppαF), was efficiently translocated and N-glycosylated, verifying the functionality of the yeast microsomes (Fig. 3B). To monitor O-mannosylation, we took advantage of the well characterized mannoprotein Ccw5 (11), which is comprised of a signal peptide (SP; amino acids 1–23), a Ser/Thr-rich region with a single N-glycosylation site embedded (Asn-114), and a C-terminal domain of unknown function (amino acids 132–227) (Fig. 3A, Ccw5). Ccw5 (predicted molecular mass 23.2 kDa) is a PMT substrate and is heavily O-mannosylated in vivo (11). In WT yeast, Asn-114 is only rarely N-glycosylated because it is masked by surrounding O-mannosylation (11). In our in vitro system, Ccw5 including its SP (apparent molecular mass 28 kDa) was the major translation product (Fig. 3C, lane 2). Upon addition of microsomes, two translocated protein variants were identified that showed detergent-dependent resistance to proteinase K (Fig. 3C, lanes 3–5). Treatment with α-mannosidase that trims N-linked glycans and efficiently removes O-linked mannose residues (33) further proved that both, the prominent ∼37 kDa (mannosylated Ccw5: mCcw5) and the less abundant ∼40 kDa (N-glycosylated mCcw5: gmCcw5) form were extensively O-mannosylated (Fig. 3D). In addition to O-mannosyl glycans, gmCcw5 contained an N-linked glycan that could be removed by peptide-N-glycosidase F (data not shown) and was absent in a Ccw5 variant with the single N-glycosylation sequon mutated (N114Q; Figs. 3F and 5C, lane 7). When translocation reactions were performed in the presence of a PMT-specific inhibitor at concentrations that slightly impair O-mannosyltransferase activity (4), translocation products shifted to lower molecular masses (Fig. 3E), further confirming O-mannosylation of Ccw5. Moreover, in the yeast microsomes the SP was cleaved, reflecting the in vivo processing of Ccw5 (Fig. 3F).

FIGURE 3.

Microsomal translation/translocation/mannosylation system. A, schematic presentation of yeast ppαF and Ccw5 constructs with SP depicted in black and the Ser/Thr-rich region (STR) in dark gray. Spacer regions (S) and the triple FLAG epitope are represented by black boxes. Putative N-glycosylation sites are indicated by the letter Y and the respective mutation by an asterisk. The leading 31 amino acids from yeast invertase (Suc2) containing the co-translational SP are depicted in white. coCcw5, Ccw5 containing co-translational SP. B, in vitro translation of mRNA coding for yeast prepro-α-factor (ppαF, lane 1) in the presence of yeast microsomes (yM, lanes 2–4). Microsomes were extracted with 500 mm KOAc and recovered through a sucrose cushion. Asterisks indicate the number of N-glycans added to the protein. C, in vitro translation of mRNA coding for yeast Ccw5 (open triangle, lane 2) in the presence of WT yM (lanes 3–5). Translocation assays (lanes 3–5) are indicated by the presence of Proteinase K and detergent and were subsequently precipitated with TCA. mCcw5, mannosylated Ccw5; gmCcw5, additionally N-glycosylated mCcw5. D, for de-mannosylation with α(1-2,3,6)-mannosidase microsomes were extracted with 500 mm KOAc and recovered through a sucrose cushion. E, in vitro processing of Ccw5 in the presence of increasing amounts of PMT inhibitor OGT2468. Proteins were subsequently precipitated with ammonium sulfate. Hypo-mannosylated forms of Ccw5 are indicated by gray triangles. B-E, proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by autoradiography. F, comparison of in vivo (lanes 1 and 2) and in vitro (lanes 4 and 5) processed Ccw5FLAG and N-glycosylation mutant (N114QFLAG). A non-mannosylated ER form of Ccw5FLAG was isolated from a sec53 mutant. The ts mutant was grown at non-permissive temperature (37 °C) for 1 h. De-mannosylation assays are indicated by the presence of α(1-2,3,6)-mannosidase. After anti-FLAG precipitations, fractions from 1.5 × 106 cells (lanes 1 and 2), and of standard in vitro reactions (lanes 3–5) were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blot. Blots were probed with antiserum directed against the FLAG epitope (Ccw5FLAG/N114QFLAG). Hypo-mannosylated forms of Ccw5 are indicated by gray triangles. A partially de-mannosylated form of Ccw5 (circle) and heavy chain of antibody used for precipitation (asterisk) are indicated.

FIGURE 5.

Protein O-mannosylation at the post-translational translocon. A, signal peptides of prepro-α-factor (ppαF), native Ccw5, and coCcw5. The hydrophobic core sequences are shown in italics and sites of signal peptidase cleavage are indicated by dashes. The Suc2 sequence of the chimeric Ccw5 fusion protein (coCcw5) is underlined. B, analysis of the hydrophobicity of the signal peptides of ppαF, Ccw5, and Suc2. The average hydrophobicity of the hydrophobic core sequences was calculated as described previously (35). The window is defined as the amino acids that follow the last positively charged residue of the n-region that precedes the hydrophobic core. C, left, scheme of experimental workflow. Right, in vitro translation of mRNAs coding for Ccw5FLAG constructs (lanes 1, 3, and 4) in the presence of WT yM (lanes 2 and 5–7). Post-translational translocation is indicated by the presence of CHX. The translation product of ppαF mRNA is indicated. After anti-FLAG precipitation, proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by autoradiography.

To simplify the experimental setup, we analyzed a FLAG-tagged version of the Ccw5 N114Q variant in vitro and compared the Mr of its translation and de-mannosylated translocation product with Ccw5FLAG, which was immunoprecipitated from a temperature-sensitive sec53 mutant where N-glycosylation, O-mannosylation, and ER exit can be blocked (34). SP-cleavage became obvious by a difference of ∼2 kDa in the molecular mass between the in vitro translation product and the non-glycosylated in vivo ER form of Ccw5, which was detected in the sec53 mutant under restrictive conditions (Fig. 3F, compare lane 2 with 3; and data not shown). The same shift in Mr was observed after translocation of Ccw5 into yeast microsomes when O-linked glycans had been removed by the use of α-mannosidase (Fig. 3F, lanes 4 and 5). Together our findings show that in analogy to the in vivo process, in yeast microsomes the Ccw5 SP is removed and the protein efficiently O-mannosylated but rarely N-glycosylated, thereby validating the functionality of the microsomal setup.

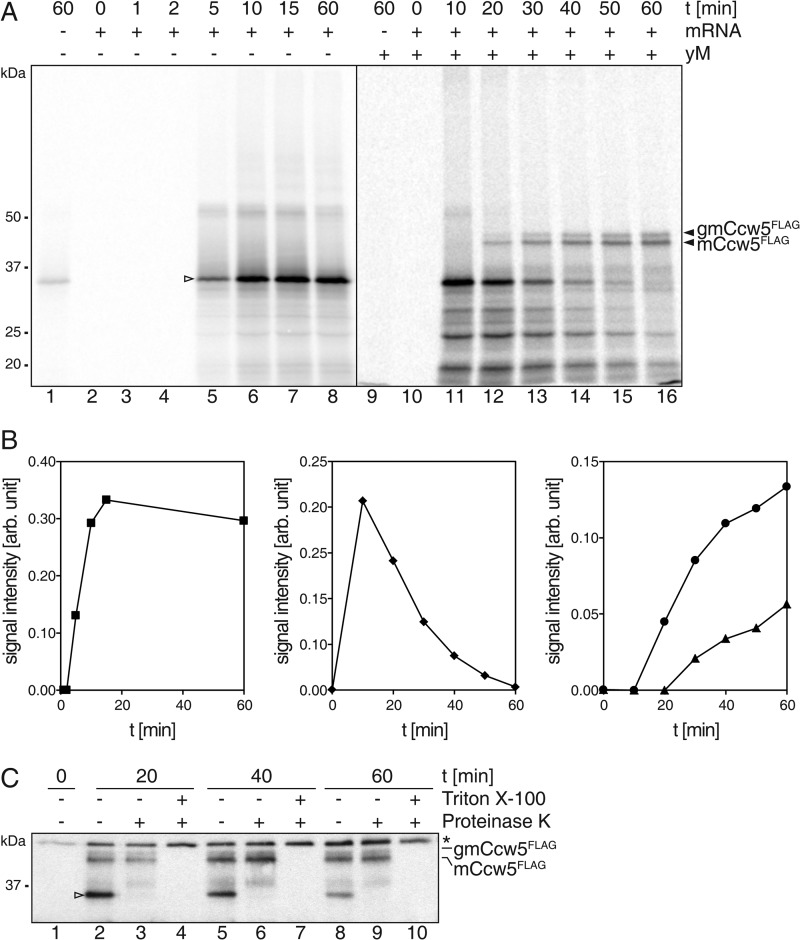

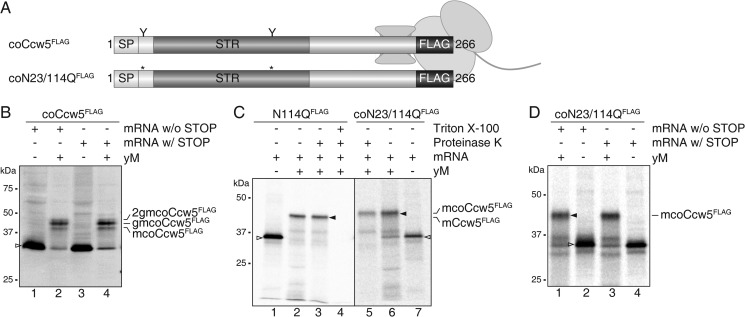

Protein O-Mannosylation at the Post- and Co-translational Translocon

We took advantage of the yeast microsomal system to further follow the question of whether PMTs act at the translocon complex. Time course analyses for translation, translocation, and glycosylation of Ccw5 revealed that translation of the Ccw5 mRNA reached its maximum after 10 min of incubation (Fig. 4, A and B). In the presence of yeast microsomes, the Ccw5 translation product was quantitatively translocated and glycosylated after a period of 60 min. Only the glycosylated forms of Ccw5 were protease protected (Fig. 4C, lanes 3, 6, and 9) demonstrating that the non-glycosylated form was not detectable in the microsomes and excluding the possibility that the translation product was translocated into the microsomes and subsequently O-mannosylated over time as previously reported for un-/misfolded proteins (13, 14). In addition, this experiment strongly suggested that the Ccw5 translation product was entering yeast microsomes via the post-translational translocon.

FIGURE 4.

Characterization of the microsomal O-mannosylation system. A, in vitro translation of mRNA coding for C-terminally FLAG-tagged Ccw5 (open triangle; lanes 2–8) in the presence of WT yM (lanes 10–16). Reactions were stopped at the indicated time points by addition of CHX and Triton X-100. mCcw5, mannosylated Ccw5; gmCcw5, additionally N-glycosylated mCcw5. B, quantification of signals for Ccw5 translation (square), translocation (diamond), and glycosylation (circle, mCcw5; triangle, gmCcw5). C, translocation and concurrent mannosylation was confirmed by Protease K treatment. Asterisk indicates the heavy chain of antibody used for precipitation. After anti-FLAG precipitation, proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by autoradiography (A) or Western blotting (C).

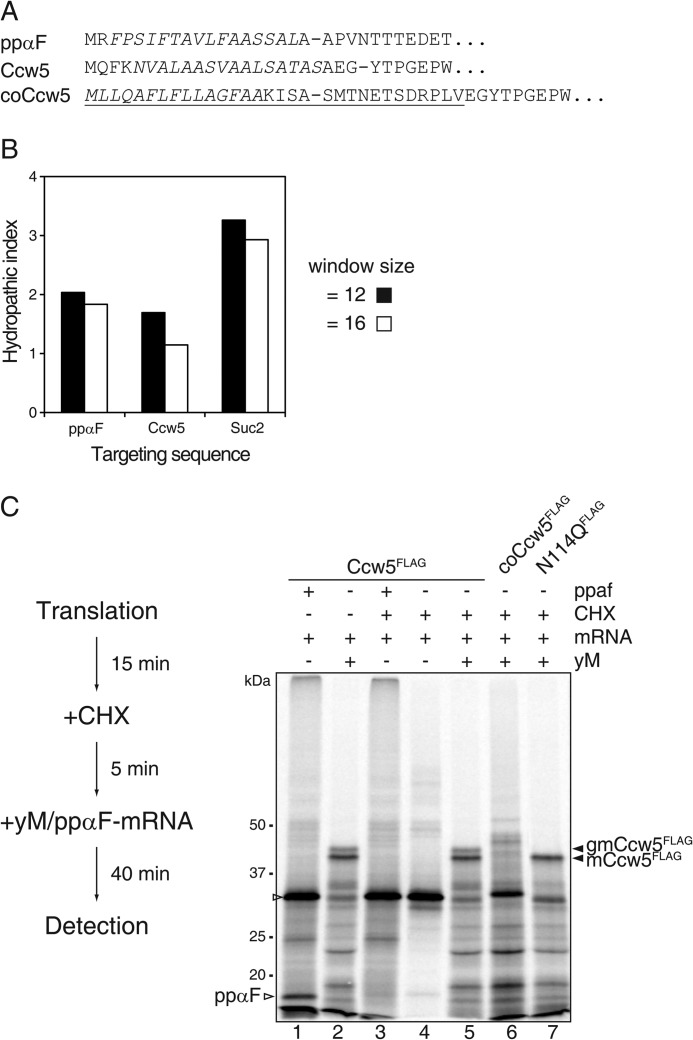

The hydrophobic core of a SP determines whether a protein is translocated across the ER membrane in a Sec63 complex-dependent or -independent manner (35). Analysis of its signal sequence further supported Sec63-dependent ER translocation of Ccw5 (Fig. 5, A and B). To experimentally support this prediction, translation was performed in the absence of microsomes for 15 min. Subsequently, further translation events were impeded by the addition of cycloheximide (CHX). After 5 min of incubation, completeness of the CHX block was verified by addition of mRNA encoding ppαF (Fig. 5C, compare lane 1 with 3). Yeast microsomes were added and translation products were monitored after an incubation period of 40 min. Blocking the translation had no effect on translocation and glycosylation of Ccw5, demonstrating that this protein gets O-mannosylated when entering the ER through the heptameric translocon complex (Fig. 5C, lanes 2 and 5).

To investigate whether O-mannosylation also takes place independently of the tetrameric Sec63 complex, we exchanged the SP of Ccw5 for the well characterized SP of S. cerevisiae invertase (SUC2), which directs proteins in vitro preferentially to the trimeric Sec61 complex of yeast microsomes (36) (coCcw5; Figs. 3A, 5, and 6A). Although Ccw5FLAG was unaffected, CHX treatment largely impeded glycosylation of coCcw5FLAG in the presence of yeast microsomes (Fig. 5C, lane 6), whereas in the absence of CHX the protein was efficiently O-mannosylated as well as N-glycosylated (Fig. 6B, lane 4). These data strongly suggest that in our microsomal system the Suc2-SP redirected Ccw5 from the heptameric to the trimeric Sec61 complex. Because with the Suc2 sequence an additional N-glycosylation site is introduced, three different translocation products were detected: a prominent band with an apparent molecular mass of ∼47 kDa (gmcoCcw5FLAG) and two minor bands of ∼44 (mcoCcw5FLAG) and ∼49 kDa (2gmcoCcw5FLAG) (Fig. 6B, lane 4). For ease of identification of the glycosylated translocation products, we created a coCcw5 mutant protein lacking both N-glycosylation sites (Fig. 6A, coN23/N114QFLAG), which was significantly O-mannosylated (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

Protein O-mannosylation at the co-translational translocon. A, schematic presentation of Ccw5FLAG constructs with the Ser/Thr-rich region (STR) depicted in dark gray. The leading 31 amino acids from yeast invertase (Suc2) containing the co-translational SP are depicted in white. The triple FLAG epitope is represented by black boxes. N-Glycosylation sites are indicated by the letter Y and corresponding mutations by asterisks. coCcw5, Ccw5 containing co-translational SP. Approximate location of the STR of a Ccw5 translocation intermediate associated with the ribosome. B, translocation intermediate of Ccw5FLAG. Constructs were translated in the presence or absence of yM from mRNA harboring or lacking a STOP codon. mcoCcw5, mannosylated coCcw5; gmcoCcw5, single N-glycosylated mcoCcw5; 2gmcoCcw5, mcoCcw5 with two N-glycans attached. C, in vitro translation of mRNAs coding for post- and co-translational translocated Ccw5FLAG constructs (open triangles; lanes 1 and 7) in the presence of WT yM (lanes 2–4 and 5 and 6). Translocation assays are indicated by the presence of Proteinase K and detergent. mCcw5: mannosylated Ccw5. D, translocation intermediate of N-glycosylation mutant of coCcw5. After anti-FLAG precipitation, proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by autoradiography (C and D). Alternatively, samples were analyzed by Western blot after microsomal enrichment (B).

To directly assess O-mannosylation at the trimeric Sec61 translocon, we analyzed translocation intermediates attached to ribosomes. Therefore, the translational stop codon was removed from both coCcw5FLAG variants. As a consequence, during in vitro translation the ribosome does not dissociate from the mRNA and the resulting protein remains bound to the ribosomal P-site at its C-terminal end (37). The arrested Ccw5 nascent chain extends through the ribosome-translocon complex and its entire Ser/Thr-rich region faces the ER lumen (Fig. 6A). Both coCcw5FLAG translocation intermediates were O-mannosylated and N-glycosylated as efficient as their non-arrested counterparts (Fig. 6, B and D), functionally demonstrating the close proximity between PMTs, OST, and the translocon. The processing of coCcw5 translocation intermediates further showed that PMTs and OST could act on the same nascent polypeptide chain at the translocon (Fig. 6, B and D).

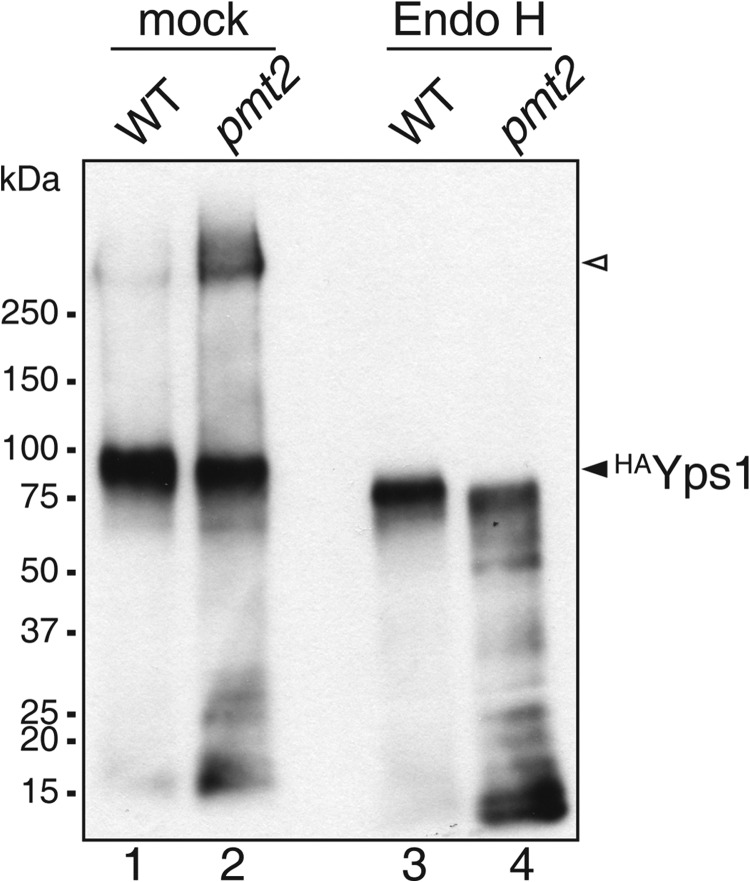

Interplay of Protein O-Mannosylation and N-Glycosylation

To analyze whether competition for protein substrates between both glycosylation machineries is a general concept, we comprehensively studied in vivo N-glycosylation site occupancy in yeast mutants defective in initiating protein O-mannosylation. Taking advantage of the fact that yeast cell walls are rich in glycoproteins that are N-glycosylated, O-mannosylated, or both (8), we analyzed N-glycosylation site occupancy of cell wall proteins isolated from WT and pmtΔ mutant strains following our previously established protocol (26). Briefly, proteins were extracted from isolated cell walls under denaturing conditions, and treated with endoglycosidase H (Endo H) to remove N-linked glycans, still leaving a single GlcNAc residue attached to the Asn of the N-glycosylation sequon. Following protease treatment, glycopeptides were identified by LC-MS/MS. In total, we identified 50 distinct N-glycosylated peptides from 19 different proteins (Table 4), which contained one or more GlcNAc modifications and a corresponding number of N-glycosylation sites. Among those, about one-fourth (12 glycopeptides) were exclusively found in pmtΔ mutants (Table 5), indicating enhanced usage of N-glycosylation sites in O-mannosylation mutants. Resistance of O-mannosylated proteins/peptides toward protease digestion as well as MS analyses, however, could not be completely excluded. Consistent with our in vitro data, a GlcNAc-containing glycopeptide from Ccw5 emerged only in pmtΔ mutant strains (Table 5).

TABLE 4.

Glycopeptides from covalently linked cell wall proteins identified by LC-MS/MS

50 N-glycosylated peptides from 19 different proteins were identified by LC-MS/MS. GlcNAc modifications on Asn are indicated as “HexNAc (N)”; Cys residues are propionamide modified; N-glycosylation sequons are shown in bold. Ser and Thr residues of Ccw5 shown to be O-mannosylated (11) are highlighted by italics. m/z ratio, charge, MASCOT score and E-value are from representative glycopeptide identifications; asterisks indicate glycopeptides only found in pmtΔ mutants.

| Protein | Glycopeptide | m/zcharge | Score | E-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ccw5 | *K.TSTNATSSSCATPSLK.D + HexNAc (N) | 915.42502+ | 43 | 9.5E-3 |

| Crh1 | T.DKFHNYTL.D + HexNAc (N) | 620.79562+ | 19 | 2.5E0 |

| Ecm33 | R.GGANFDSSSSNFSCNALK.K + HexNAc (N) | 1040.44882+ | 83 | 4.5E-7 |

| K.VQTVGGAIEVTGNFSTLDLSSLK.S + HexNAc (N) | 1270.16072+ | 98 | 4.1E-8 | |

| K.AAFSNLTTVGGGFIIANNTQLK.V + 2 HexNAc (N) | 1322.17792+ | 67 | 5.6E-5 | |

| F.DNLVWANNITLR.D + HexNAc (N) | 816.42652+ | 67 | 4.8E-5 | |

| I.DGSLTIFNSSSLSSFSA.D + HexNAc (N) | 961.94743+ | 61 | 1.5E-4 | |

| L.DKISGCSTIVGNLTITG.D + HexNAc (N) | 976.99423+ | 39 | 3.3E-3 | |

| S.DSLQFSSNGDNTTLAF.D + HexNAc (N) | 960.42873+ | 58 | 1.8E-4 | |

| Egt2 | R.NSTFSMVSSTK.L + oxidation (M); HexNAc (N) | 704.31882+ | 43 | 9.5E-3 |

| Gas1 | K.FFYSNNGSQFYIR.G + HexNAc (N) | 923.42542+ | 56 | 4.7E-4 |

| R.VYAINTTLDHSECMK.A + oxidation (M); HexNAc (N) | 672.30773+ | 52 | 1.1E-3 | |

| K.NLSIPVFFSEYGCNEVTPR.L + HexNAc (N) | 1223.58212+ | 94 | 8.9E-8 | |

| R.GVAYQADTANETSGSTVNDPLANYESCSR.D + HexNAc (N) | 1098.81433+ | 122 | 4.7E-11 | |

| K.TVVDTFANYTNVLGFFAGNEVTNNYTNTDASAFVK.A + 2 HexNAc (N) | 1404.32623+ | 119 | 3.0E-10 | |

| Gas3 | *K.ILTDYAVPTTFNYTIK.N + HexNAc (N) | 1032.03032+ | 70 | 3.0E-5 |

| K.DDFVNLESQLKNVSLPTTKESEISS.D + HexNAc (N) | 995.15943+ | 46 | 7.7E-3 | |

| R.DMKQYISKHANRSIPVGYSAA.D + HexNAc (N) | 847.09043+ | 39 | 3.3E-2 | |

| Y.DKLNSTFE.D + HexNAc (N) | 578.77202+ | 37 | 4.5E-2 | |

| Gas5 | A.ASSSNSSTPSIEIK.G + HexNAc (N) | 805.89072+ | 50 | 2.4E-3 |

| R.GVDYQPGGSSNLTDPLADASVCDRDVPVLK.D + HexNAc (N) | 1121.53793+ | 102 | 1.5E-8 | |

| Mkc7 | *E.DNLTTLTTTKIPVLL.D + HexNAc (N) | 923.52422+ | 41 | 9.4E-3 |

| Pir1 | *G.DGQIQATTNTTVAPVSQIT.D + HexNAc (N) | 1074.53552+ | 40 | 2.5E-2 |

| Plb1 | R.AMLSGAGMLAAMDNR.T + 3 oxidation (M); HexNAc (N) | 880.38722+ | 74 | 4.8E-6 |

| K.DAGFNISLADVWGR.A + HexNAc (N) | 862.41832+ | 69 | 3.1E-5 | |

| R.EASGLSDNETEWLK.K + HexNAc (N) | 891.40692+ | 46 | 4.7E-3 | |

| *R.ATSNFSDTSLLSTLFGSNSSNMPK.I + Oxidation (M); 2 HexNAc (N) | 976.78153+ | 56 | 3.7E-4 | |

| *R.HSFNGNQSTFK.M + HexNAc (N) | 735.33722+ | 47 | 5.1E-3 | |

| *A.DGRYPGTTVINLNATLF.E + HexNAc (N) | 1028.02262+ | 45 | 8.8E-3 | |

| Plb2 | K.MNYNVTER.L + Oxidation (M); HexNAc (N) | 623.27292+ | 23 | 6.4E-1 |

| R.NASGLSTAETDWLK.K + HexNAc (N) | 848.40752+ | 63 | 1.3E-4 | |

| K.SIVNPGGSNLTYTIER.W + HexNAc (N) | 962.48572+ | 74 | 1.1E-5 | |

| Pry3 | *K.STTTLATTANNSTR.A + HexNAc (N) | 821.39912+ | 56 | 6.6E-4 |

| K.YNYSNPGFSESTGHFTQVVWK.S + HexNAc (N) | 884.40693+ | 58 | 2.4E-4 | |

| Sag1 | K.LLNSSQTATISLADGTEAFK.C + HexNAc (N) | 1135.57272+ | 103 | 1.3E-8 |

| N.DWWFPQSYNDTNA.D + HexNAc (N) | 923.88092+ | 76 | 1.2E-6 | |

| Y.ENTTFTCTAQN.D + HexNAc (N) | 752.31682+ | 54 | 3.0E-4 | |

| Sed1 | *A.QFSNSTSASST.D + HexNAc (N) | 660.28262+ | 54 | 3.8E-4 |

| Utr2 | K.NGTSAYVYTSSSEFLAK.D + HexNAc (N) | 1014.47612+ | 80 | 2.2E-6 |

| R.TLYKNETYNATTQK.Y + 2 HexNAc (N) | 694.33393+ | 29 | 3.4E-1 | |

| A.ATFCNATQACPE.D + HexNAc (N) | 800.83482+ | 52 | 4.2E-4 | |

| K.DYSSKLGNANTFLGNVSEA.D + HexNAc (N) | 1095.51402+ | 80 | 1.8E-6 | |

| Ydr524c-b | A.ANVSTNGSNR.T + 2 HexNAc (N) | 713.32552+ | 34 | 9.8E-2 |

| A.ANVSTNGSNR.T + 3 HexNAc (N) | 814.86492+ | 29 | 2.3E-1 | |

| A.ANVSTNGSNRTNGSNTTSTK.I + 4 HexNAc (N) | 941.75803+ | 31 | 1.0E-1 | |

| A.ANVSTNGSNRTNGSNTTSTK.I + 5 HexNAc (N) | 1009.45063+ | 19 | 1.2E0 | |

| Ygp1 | R.VVNETIQDK.S + HexNAc (N) | 624.81982+ | 29 | 3.5E-1 |

| Yjl171 | *S.DATPFNGTVSA.D + HexNAc (N) | 641.79322+ | 26 | 4.8E-1 |

| Yps1 | *F.DVTINGIGISDSGSSNKTLTTTKIPALL.D + HexNAc (N) | 1007.20583+ | 62 | 1.2E-4 |

| *Y.DNFPIVLKNSGAIKSNTYSLYLNDS.D + HexNAc (N) | 992.83293+ | 55 | 1.0E-3 |

TABLE 5.

Glycopeptides of covalently linked cell wall proteins unique to pmtΔ mutants

GlcNAc modifications on Asn are indicated as “HexNAc (N)”; Cys residues are propionamide modified; N-glycosylation sequons are shown in bold. Comparison of data obtained from WT and pmtΔ mutant cells revealed that a considerable number of glycopeptides was exclusively found in pmtΔ mutants. Ser and Thr residues of Ccw5 shown to be O-mannosylated (11) are highlighted by italics. Details about glycopeptide identifications are listed in Table 4.

| Protein | Glycopeptide | Mutant |

|---|---|---|

| Ccw5 | K.TSTNATSSSCATPSLK.D + HexNAc (N) | pmt1pmt2, pmt1pmt4 |

| Gas3 | K.ILTDYAVPTTFNYTIK.N + HexNAc (N) | pmt1, pmt2, pmt4 |

| Mkc7 | E.DNLTTLTTTKIPVLL.D + HexNAc (N) | pmt1, pmt2, pmt4, pmt1pmt2 |

| Pir1 | G.DGQIQATTNTTVAPVSQIT.D + HexNAc (N) | pmt1pmt4 |

| Plb1 | R.ATSNFSDTSLLSTLFGSNSSNMPK.I + Oxidation (M); 2 HexNAc (N) | pmt1, pmt4 |

| R.HSFNGNQSTFK.M + HexNAc (N) | pmt1, pmt4 | |

| A.DGRYPGTTVINLNATLF.E + HexNAc (N) | pmt1, pmt2, pmt4, pmt1pmt2 | |

| Pry3 | K.STTTLATTANNSTR.A + HexNAc (N) | pmt1pmt2, pmt1pmt4 |

| Sed1 | A.QFSNSTSASST.D + HexNAc (N) | pmt1, pmt2, pmt4, pmt1pmt2, pmt1pmt4 |

| Yjl171c | S.DATPFNGTVSA.D + HexNAc (N) | pmt1pmt4 |

| Yps1 | Y.DNFPIVLKNSGAIKSNTYSLYLNDS.D + HexNAc (N) | pmt2, pmt4, pmt1pmt2 |

| F.DVTINGIGISDSGSSNKTLTTTKIPALL.D + HexNAc (N) | pmt4 |

To further verify these results, we analyzed one of the proteins affected in pmtΔ mutants, Yps1, which is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored aspartic protease belonging to a family of fungal yapsins localizing to the plasma membrane (38). We expressed an N-terminal HA-tagged version of Yps1 (HAYps1) in WT and pmt2 mutant strains and analyzed its glycosylation by Western blot before and after deglycosylation using Endo H. In WT, HAYps1 showed an apparent molecular mass of ∼90 kDa that shifted to ∼75 kDa upon Endo H treatment (Fig. 7, lanes 1 and 3), indicating moderate N-glycosylation consistent with previous data (39). In the pmt2 mutant, molecular mass and abundance of the ∼90 kDa form of HAYps1 slightly decreased, and in turn a prominent high molecular mass form (>270 kDa) appeared (Fig. 7, lane 2). Upon Endo H treatment both forms of HAYps1 shifted to ∼72 kDa, demonstrating that (i) HAYps1 is mannosylated by Pmt2 (Fig. 7, lanes 3 and 4) and (ii) the increase in molecular weight in the pmt2 mutant is due to enhanced N-glycosylation (Fig. 7, lanes 2 and 4). Although we cannot exclude that changes in the glycan structure additionally contribute to the observed high molecular weight shift in the pmt2 mutant, these data further support the idea that deficient O-mannosylation of HAYps1 can alter N-glycosylation site usage.

FIGURE 7.

Glycosylation of Yps1 in WT and mutant pmt2. HAYps1 is aberrantly N-glycosylated in pmt2 mutant cells. Cell walls were isolated from WT and pmt2 mutant cells transformed with pJH33 (HAYps1). Proteins were extracted with SDS, treated with Endo H, resolved on SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and analyzed by Western blotting. Extracts from 1.5 × 107 cells were analyzed per lane. A prominent band was detected in the WT sample (∼90 kDa, lane 1), which shifted to lower molecular mass (∼75 kDa, lane 3) upon Endo H treatment indicating moderate N-glycosylation. In the pmt2 sample the ∼90-kDa form was less abundant and a high molecular mass form (∼270–350 kDa, open triangle) was detected (lane 2). Endo H treatment demonstrated that the high molecular weight form of HAYps1 in pmt2 cells was due to increased N-glycosylation (lane 4).

DISCUSSION

In baker's yeast, more than 1,000 different proteins enter the ER through the translocon complex (2). Many of these secretory, plasma membrane and cell wall proteins contain N-linked glycans and/or Ser/Thr-rich regions (at least 20 amino acids with a Ser/Thr content >40%), which are substantially O-mannosylated (8). The attached carbohydrate chains affect folding, localization, stability, and/or function of these proteins, thus both, N-glycosylation as well as O-mannosylation are essential processes (3).

The covalent linkage of hydrophilic carbohydrates to polypeptide chains alters the biophysical properties of proteins. The most significant effect is on polypeptide folding and it has been proposed that in the course of eukaryotic evolution, this has been the selection mechanism that resulted in the widespread occurrence of post-translational modifications on secretory proteins (6). Several mechanisms can result in a protein biogenesis pathway of secretory proteins where glycosylation occurs before folding, one of which is placing the modification machinery at the translocon. Indeed, conclusive evidence arose over the recent years that protein translocation across the ER membrane and N-glycosylation can be physically and temporally coupled processes, due to a large multisubunit entity, the translocon-OST complex (7). In analogy, it was generally assumed that protein O-mannosylation also takes place at the translocon, although there were virtually no experimental data addressing this issue (12). Consistent with the hypothesis that primarily the folding status of a polypeptide defines its substrate propensity for the glycosylation machinery, prolonged ER residence allows modification of exposed O-mannosyl glycan acceptor sites within un-/misfolded proteins or slow folding intermediates (8, 16) by Pmt1-Pmt2 complexes. However, O-mannosylation of physiological substrates is a very efficient process, exemplified by the cell surface receptor Mid2, which receives up to over 100 O-linked glycans and travels through the secretory pathway in less than 3 min (33). Therefore, we set out to reinvestigate protein O-mannosylation in the context of protein ER-translocation. Here, we demonstrate that PMTs can associate with the TC and quickly and efficiently mannosylate proteins while entering the ER.

In line with our co-IP data, physical and genetic interactions between Pmt1-Pmt2 and Sec61 as well as Sec63 and Sec71 have been identified in global screens for yeast protein complexes (40–43). Furthermore, affinity-capture experiments revealed direct interactions between Pmt1 and Ssh1 (41), the Sec61 homolog of a second TC (Ssh1, Sbh2, and Sss1), which mediates co-translational translocation of a subset of proteins (44). In addition to the translocon, we also detected OST in the Pmt1-Pmt2 immunoprecipitate (Figs. 1 and 2). Moreover, in yeast microsomes Pmt1-Pmt2 complexes could be chemically cross-linked to the α- and β-subunits of OST, Ost1, and Wbp1.5 Again high-throughput data corroborate interactions between Pmt1 and Ost3/Ost6 (42, 43), Wbp1 (41, 42), and Swp1 (40). The associations that we observed were highly reproducible and specific, although co-IP of the translocon and OST subunits with Pmt1 was not quantitative (Figs. 1 and 2). This might be due to the solubilization conditions, which can significantly affect the stability of membrane protein complexes. Alternatively, the relatively low abundance of the TC and OST in the Pmt1-immunoprecipitate might reflect molecular dynamics of potential PMT-OST-TC complexes and/or point toward independent functions of Pmt1-Pmt2 complexes, such as glycosylation of proteins after ER-translocation is completed.

Because our initial co-IP data strongly suggested that PMTs can associate with both, the co- and post-translational translocon, we established a cell-free translation/translocation system to monitor O-mannosylation in yeast microsomes. Similar systems have enabled the characterization of the molecular details of protein translocation (32, 45, 46) and N-glycosylation (47). In the presence of yeast microsomes, our PMT model substrate Ccw5 was translocated and significantly O-mannosylated (Figs. 3–6) but rarely N-glycosylated, which reflects the situation in vivo (11). A shift in the apparent molecular mass by ∼10 kDa indicated that mannose was attached to most of the 50 Ser/Thr residues within the protein although disproportionate effects of O-linked mono-mannosyl residues on the mobility of proteins during SDS-PAGE have been reported (48).

Our in vitro translation/translocation/glycosylation system allowed us to mimic in vivo ER processing of Ccw5 (Fig. 3). Moreover, the translocation pathway of Ccw5 into the ER also mirrored the in vivo situation. It is well established that both the length and hydrophobicity of the core region of a SP determine how a protein is targeted to the ER (2, 35). The less hydrophobic SPs of Ccw5 and ppαF (Fig. 5B) direct these proteins independently of the signal recognition particle to the post-translational translocon in vivo (2). Consistent with this, Ccw5 was targeted to the post-translational translocon in our yeast microsomal system (Fig. 5C). In line with our data, ppαF was previously shown to be also post-translationally translocated into yeast microsomes when synthesized in a yeast cell-free or a rabbit reticulocyte lysate translation system (49).

The time course experiments shown in Fig. 4 clearly demonstrated that in the established in vitro system of O-mannosylation of Ccw5 occurred while the protein post-translationally entered the ER. Although translation was completed after 10 min of incubation, only the glycosylated forms of Ccw5 were found inside the microsomes. The amount of glycosylated Ccw5 increased over time and after 60 min almost all translation products were significantly O-mannosylated. In contrast, previous reports showed that un-/misfolded model proteins were O-mannosylated after they were co- or post-translationally translocated into yeast microsomes, whereas SP cleavage occurred normally (13, 14). Furthermore, O-mannosylation of the translocated proteins required addition of ATP and yeast cytosol (13, 14). In this context it is worth mentioning that extra ATP inhibited O-mannosylation in our microsomal system (data not shown). Furthermore, only very minor amounts of un-/misfolded proteins appeared to receive O-mannosyl glycans (∼5–10%) (13, 14), whereas in our system translocated Ccw5 was quantitatively O-mannosylated (Fig. 3).

To gain even more conclusive evidence that PMTs can associate with the translocon complex, we performed experiments with nascent chains arrested at the translocon-ribosome complex. For this purpose, we targeted Ccw5 to the Sec61 complex by exchanging its SP with the well characterized SP of S. cerevisiae invertase, which directs proteins preferentially to the co-translational translocon in yeast microsomes (36). As in the case of post-translationally translocated Ccw5, O-mannosylation of coCcw5 was efficient and fast (Fig. 6C). In addition, analyses of translocation intermediates showed that PMTs can act on nascent chains entering the ER (Fig. 6, B and D) thereby verifying the close association of PMTs and the TC that we observed in vivo (Fig. 1). Our results further show that a single polypeptide translocating into the ER can be modified by the O- as well as the N-glycosylation machinery and both processes most likely require that the polypeptide domain to be glycosylated is in a flexible state. In addition, the functional involvement of hydroxyamino acid side chains in both processes can result in a direct competition. Indeed, we found that decreased O-mannosylation altered N-glycosylation site occupancy, because in 24% of the identified glycopeptides specific N-glycan acceptor sequons (Asp-X-Ser/Thr) were only used in pmtΔ mutants (Tables 4 and 5). A recent x-ray structure of a bacterial oligosaccharyltransferase revealed that the β-hydroxyl group of Ser/Thr residues at position +2 of the acceptor sequon is crucial for sequon binding and recognition (50), providing a possible molecular explanation for the observed competition. In accordance, we previously showed that O-mannosylation of Ser/Thr-residues in and surrounding the N-glycan acceptor site (TSTNATSSS; Table 5) of the cell wall protein Ccw5 prevented its N-glycosylation (11).

Considering that a whole raft of processes takes place during translocation of nascent chains, it seems plausible that many enzymes including PMTs associate with the translocon, most likely in a highly dynamic manner. The here established in vitro system will help to distinguish between mannosylation processes occurring during or after protein translocation and help to find common as well as distinct features of these two processes.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to K. Römisch (Saarland University, Germany), R. Schekman (University of California, Berkeley, CA), R. Gilmore (University of Massachusetts Medical School, MA), S. Yoshida (Kirin Brewery Co. Ltd., Japan), L. Lehle (University of Regensburg, Germany), M. Makarow (University of Helsinki, Finland), N. Dean (Stony Brook University, New York), B. Dobberstein (Heidelberg University, Germany), and E. Zatorska (Heidelberg University, Germany) for generously providing antibodies, yeast strains, and plasmids. We thank B. Dobberstein, M. Lemberg, K. Meese (Heidelberg University) for valuable help with the in vitro system. We also thank Thomas Ruppert (Heidelberg University) for LC-MS/MS analyses and M. Büttner for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grant SFB638, project A18, and grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation.

J. Hutzler, and S. Strahl, unpublished data.

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- CHX

- cycloheximide

- Dol-P-Man

- dolicholmonophosphate-activated mannose

- Endo H

- endoglycosidase H

- OST

- oligosaccharyltransferase

- PMT

- protein O-mannosyltransferase

- SP

- signal peptide

- TC

- translocon complex

- ts

- temperature-sensitive

- co-IP

- co-immunoprecipitation

- yM

- yeast microsomes

- TMD

- transmembrane domain.

REFERENCES

- 1. Park E., Rapoport T. A. (2012) Mechanisms of Sec61/SecY-mediated protein translocation across membranes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 41, 21–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ast T., Cohen G., Schuldiner M. (2013) A network of cytosolic factors targets SRP-independent proteins to the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell 152, 1134–1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lehle L., Strahl S., Tanner W. (2006) Protein glycosylation, conserved from yeast to man: a model organism helps elucidate congenital human diseases. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 45, 6802–6818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arroyo J., Hutzler J., Bermejo C., Ragni E., García-Cantalejo J., Botías P., Piberger H., Schott A., Sanz A. B., Strahl S. (2011) Functional and genomic analyses of blocked protein O-mannosylation in baker's yeast. Mol. Microbiol. 79, 1529–1546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Helenius A., Aebi M. (2004) Roles of N-linked glycans in the endoplasmic reticulum. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73, 1019–1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aebi M. (2013) N-Linked protein glycosylation in the ER. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1833, 2430–2437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chavan M., Lennarz W. (2006) The molecular basis of coupling of translocation and N-glycosylation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 31, 17–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Loibl M., Strahl S. (2013) Protein O-mannosylation: what we have learned from baker's yeast. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1833, 2438–2446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Girrbach V., Strahl S. (2003) Members of the evolutionarily conserved PMT family of protein O-mannosyltransferases form distinct protein complexes among themselves. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 12554–12562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. González M., Brito N., Celedonio G. (2012) High abundance of serine/threonine-rich regions predicted to be hyper-O-glycosylated in the secretory proteins coded by eight fungal genomes. BMC Microbiol. 12, 213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ecker M., Mrsa V., Hagen I., Deutzmann R., Strahl S., Tanner W. (2003) O-Mannosylation precedes and potentially controls the N-glycosylation of a yeast cell wall glycoprotein. EMBO Rep. 4, 628–632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Larriba G., Elorza M. V., Villanueva J. R., Sentandreu R. (1976) Participation of dolichol phosphomannose in the glycosylation of yeast wall mannoproteins at the polysomal level. FEBS Lett. 71, 316–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Harty C., Strahl S., Römisch K. (2001) O-mannosylation protects mutant α-factor precursor from endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 1093–1101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nakatsukasa K., Okada S., Umebayashi K., Fukuda R., Nishikawa S., Endo T. (2004) Roles of O-mannosylation of aberrant proteins in reduction of the load for endoplasmic reticulum chaperones in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 49762–49772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hirayama H., Fujita M., Yoko-o T., Jigami Y. (2008) O-Mannosylation is required for degradation of the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation substrate Gas1*p via the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biochem. 143, 555–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xu C., Wang S., Thibault G., Ng D. T. (2013) Futile protein folding cycles in the ER are terminated by the unfolded protein O-mannosylation pathway. Science 340, 978–981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ho S. N., Hunt H. D., Horton R. M., Pullen J. K., Pease L. R. (1989) Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene 77, 51–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sambrook J., Russel D. W. (2001) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 3rd ed., Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 19. Girrbach V., Zeller T., Priesmeier M., Strahl-Bolsinger S. (2000) Structure-function analysis of the dolichyl phosphate-mannose:protein O-mannosyltransferase ScPmt1p. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 19288–19296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Laemmli U. K. (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227, 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schägger H., von Jagow G. (1987) Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal. Biochem. 166, 368–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lyman S. K., Schekman R. (1995) Interaction between BiP and Sec63p is required for the completion of protein translocation into the ER of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 131, 1163–1171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. High S., Martoglio B., Gorlich D., Andersen S. S., Ashford A. J., Giner A., Hartmann E., Prehn S., Rapoport T. A., Dobberstein B. (1993) Site-specific photocross-linking reveals that Sec61p and TRAM contact different regions of a membrane-inserted signal sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 26745–26751 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Walter P., Blobel G. (1983) Preparation of microsomal membranes for cotranslational protein translocation. Methods Enzymol. 96, 84–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Weihofen A., Lemberg M. K., Ploegh H. L., Bogyo M., Martoglio B. (2000) Release of signal peptide fragments into the cytosol requires cleavage in the transmembrane region by a protease activity that is specifically blocked by a novel cysteine protease inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 30951–30956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schulz B. L., Aebi M. (2009) Analysis of glycosylation site occupancy reveals a role for Ost3p and Ost6p in site-specific N-glycosylation efficiency. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 8, 357–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ghaemmaghami S., Huh W. K., Bower K., Howson R. W., Belle A., Dephoure N., O'Shea E. K., Weissman J. S. (2003) Global analysis of protein expression in yeast. Nature 425, 737–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Harada Y., Li H., Wall J. S., Li H., Lennarz W. J. (2011) Structural studies and the assembly of the heptameric post-translational translocon complex. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 2956–2965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Albright C. F., Robbins R. W. (1990) The sequence and transcript heterogeneity of the yeast gene ALG1, an essential mannosyltransferase involved in N-glycosylation. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 7042–7049 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dan N., Middleton R. B., Lehrman M. A. (1996) Hamster UDP-N-acetylglucosamine:dolichol-P N-acetylglucosamine-1-P transferase has multiple transmembrane spans and a critical cytosolic loop. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 30717–30724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Strahl-Bolsinger S., Scheinost A. (1999) Transmembrane topology of pmt1p, a member of an evolutionarily conserved family of protein O-mannosyltransferases. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 9068–9075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rothblatt J. A., Meyer D. I. (1986) Secretion in yeast: reconstitution of the translocation and glycosylation of α-factor and invertase in a homologous cell-free system. Cell 44, 619–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lommel M., Bagnat M., Strahl S. (2004) Aberrant processing of the WSC family and Mid2p cell surface sensors results in cell death of Saccharomyces cerevisiae O-mannosylation mutants. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 46–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kepes F., Schekman R. (1988) The yeast SEC53 gene encodes phosphomannomutase. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 9155–9161 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ng D. T., Brown J. D., Walter P. (1996) Signal sequences specify the targeting route to the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. J. Cell Biol. 134, 269–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rothblatt J. A., Webb J. R., Ammerer G., Meyer D. I. (1987) Secretion in yeast: structural features influencing the post-translational translocation of prepro-α-factor in vitro. EMBO J. 6, 3455–3463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Whitley P., Nilsson I. M., von Heijne G. (1996) A nascent secretory protein may traverse the ribosome/endoplasmic reticulum translocase complex as an extended chain. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 6241–6244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ash J., Dominguez M., Bergeron J. J., Thomas D. Y., Bourbonnais Y. (1995) The yeast proprotein convertase encoded by YAP3 is a glycophosphatidylinositol-anchored protein that localizes to the plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 20847–20854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cawley N. X., Olsen V., Zhang C. F., Chen H. C., Tan M., Loh Y. P. (1998) Activation and processing of non-anchored yapsin 1 (Yap3p). J. Biol. Chem. 273, 584–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Costanzo M., Baryshnikova A., Bellay J., Kim Y., Spear E. D., Sevier C. S., Ding H., Koh J. L., Toufighi K., Mostafavi S., Prinz J., St Onge R. P., VanderSluis B., Makhnevych T., Vizeacoumar F. J., Alizadeh S., Bahr S., Brost R. L., Chen Y., Cokol M., Deshpande R., Li Z., Lin Z. Y., Liang W., Marback M., Paw J., San Luis B. J., Shuteriqi E., Tong A. H., van Dyk N., Wallace I. M., Whitney J. A., Weirauch M. T., Zhong G., Zhu H., Houry W. A., Brudno M., Ragibizadeh S., Papp B., Pál C., Roth F. P., Giaever G., Nislow C., Troyanskaya O. G., Bussey H., Bader G. D., Gingras A. C., Morris Q. D., Kim P. M., Kaiser C. A., Myers C. L., Andrews B. J., Boone C. (2010) The genetic landscape of a cell. Science 327, 425–431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Krogan N. J., Cagney G., Yu H., Zhong G., Guo X., Ignatchenko A., Li J., Pu S., Datta N., Tikuisis A. P., Punna T., Peregrín-Alvarez J. M., Shales M., Zhang X., Davey M., Robinson M. D., Paccanaro A., Bray J. E., Sheung A., Beattie B., Richards D. P., Canadien V., Lalev A., Mena F., Wong P., Starostine A., Canete M. M., Vlasblom J., Wu S., Orsi C., Collins S. R., Chandran S., Haw R., Rilstone J. J., Gandi K., Thompson N. J., Musso G., St Onge P., Ghanny S., Lam M. H., Butland G., Altaf-Ul A. M., Kanaya S., Shilatifard A., O'Shea E., Weissman J. S., Ingles C. J., Hughes T. R., Parkinson J., Gerstein M., Wodak S. J., Emili A., Greenblatt J. F. (2006) Global landscape of protein complexes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 440, 637–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schuldiner M., Collins S. R., Thompson N. J., Denic V., Bhamidipati A., Punna T., Ihmels J., Andrews B., Boone C., Greenblatt J. F., Weissman J. S., Krogan N. J. (2005) Exploration of the function and organization of the yeast early secretory pathway through an epistatic miniarray profile. Cell 123, 507–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Surma M. A., Klose C., Peng D., Shales M., Mrejen C., Stefanko A., Braberg H., Gordon D. E., Vorkel D., Ejsing C. S., Farese R., Jr., Simons K., Krogan N. J., Ernst R. (2013) A lipid E-MAP identifies Ubx2 as a critical regulator of lipid saturation and lipid bilayer stress. Mol. Cell 51, 519–530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wittke S., Dünnwald M., Albertsen M., Johnsson N. (2002) Recognition of a subset of signal sequences by Ssh1p, a Sec61p-related protein in the membrane of endoplasmic reticulum of yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 2223–2232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gilmore R., Walter P., Blobel G. (1982) Protein translocation across the endoplasmic reticulum. II. Isolation and characterization of the signal recognition particle receptor. J. Cell Biol. 95, 470–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Meyer D. I., Krause E., Dobberstein B. (1982) Secretory protein translocation across membranes: the role of the ”docking protein.“ Nature 297, 647–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nilsson I. M., von Heijne G. (1993) Determination of the distance between the oligosaccharyltransferase active site and the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 5798–5801 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Watzele M., Klis F., Tanner W. (1988) Purification and characterization of the inducible a agglutinin of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 7, 1483–1488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rothblatt J. A., Meyer D. I. (1986) Secretion in yeast: translocation and glycosylation of prepro-α-factor in vitro can occur via an ATP-dependent post-translational mechanism. EMBO J. 5, 1031–1036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lizak C., Gerber S., Numao S., Aebi M., Locher K. P. (2011) X-ray structure of a bacterial oligosaccharyltransferase. Nature 474, 350–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Robinson J. S., Klionsky D. J., Banta L. M., Emr S. D. (1988) Protein sorting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: isolation of mutants defective in the delivery and processing of multiple vacuolar hydrolases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8, 4936–4948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lussier M., Gentzsch M., Sdicu A. M., Bussey H., Tanner W. (1995) Protein O-glycosylation in yeast. The PMT2 gene specifies a second protein O-mannosyltransferase that functions in addition to the PMT1-encoded activity. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 2770–2775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Immervoll T., Gentzsch M., Tanner W. (1995) PMT3 and PMT4, two new members of the protein-O-mannosyltransferase gene family of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 11, 1345–1351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hutzler J., Schmid M., Bernard T., Henrissat B., Strahl S. (2007) Membrane association is a determinant for substrate recognition by PMT4 protein O-mannosyltransferases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 7827–7832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gentzsch M., Tanner W. (1996) The PMT gene family: protein O-glycosylation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is vital. EMBO J. 15, 5752–5759 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ferro-Novick S., Novick P., Field C., Schekman R. (1984) Yeast secretory mutants that block the formation of active cell surface enzymes. J. Cell Biol. 98, 35–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hansen W., Garcia P. D., Walter P. (1986) In vitro protein translocation across the yeast endoplasmic reticulum: ATP-dependent posttranslational translocation of the prepro-α-factor. Cell 45, 397–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wach A., Brachat A., Alberti-Segui C., Rebischung C., Philippsen P. (1997) Heterologous HIS3 marker and GFP reporter modules for PCR-targeting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 13, 1065–1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sikorski R. S., Hieter P. (1989) A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122, 19–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Christianson T. W., Sikorski R. S., Dante M., Shero J. H., Hieter P. (1992) Multifunctional yeast high-copy-number shuttle vectors. Gene 110, 119–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gao X. D., Nishikawa A., Dean N. (2004) Physical interactions between the Alg1, Alg2, and Alg11 mannosyltransferases of the endoplasmic reticulum. Glycobiology 14, 559–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Noffz C., Keppler-Ross S., Dean N. (2009) Hetero-oligomeric interactions between early glycosyltransferases of the dolichol cycle. Glycobiology 19, 472–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Silberstein S., Collins P. G., Kelleher D. J., Rapiejko P. J., Gilmore R. (1995) The α subunit of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae oligosaccharyltransferase complex is essential for vegetative growth of yeast and is homologous to mammalian ribophorin I. J. Cell Biol. 128, 525–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Knauer R., Lehle L. (1999) The oligosaccharyltransferase complex from Saccharomyces cerevisiae: isolation of the OST6 gene, its synthetic interaction with OST3, and analysis of the native complex. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 17249–17256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Strahl-Bolsinger S., Tanner W. (1991) Protein O-glycosylation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: purification and characterization of the dolichyl-phosphate-d-mannose-protein O-d-mannosyltransferase. Eur. J. Biochem. 196, 185–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Gentzsch M., Immervoll T., Tanner W. (1995) Protein O-glycosylation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: the protein O-mannosyltransferases Pmt1p and Pmt2p function as heterodimer. FEBS Lett. 377, 128–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Toikkanen J., Gatti E., Takei K., Saloheimo M., Olkkonen V. M., Söderlund H., De Camilli P., Keränen S. (1996) Yeast protein translocation complex: isolation of two genes SEB1 and SEB2 encoding proteins homologous to the Sec61 β subunit. Yeast 12, 425–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Stirling C. J., Rothblatt J., Hosobuchi M., Deshaies R., Schekman R. (1992) Protein translocation mutants defective in the insertion of integral membrane proteins into the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol. Biol. Cell 3, 129–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Deshaies R. J., Schekman R. (1990) Structural and functional dissection of Sec62p, a membrane-bound component of the yeast endoplasmic reticulum protein import machinery. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10, 6024–6035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Feldheim D., Rothblatt J., Schekman R. (1992) Topology and functional domains of Sec63p, an endoplasmic reticulum membrane protein required for secretory protein translocation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12, 3288–3296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Feldheim D., Schekman R. (1994) Sec72p contributes to the selective recognition of signal peptides by the secretory polypeptide translocation complex. J. Cell Biol. 126, 935–943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Esnault Y., Blondel M. O., Deshaies R. J., Scheckman R., Képès F. (1993) The yeast SSS1 gene is essential for secretory protein translocation and encodes a conserved protein of the endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J. 12, 4083–4093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. te Heesen S., Knauer R., Lehle L., Aebi M. (1993) Yeast Wbp1p and Swp1p form a protein complex essential for oligosaccharyl transferase activity. EMBO J. 12, 279–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]