Abstract

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), the chronic lung disease of prematurity, is a significant contributor to perinatal morbidity and mortality. Premature birth disrupts pulmonary vascular growth and initiates a cascade of events that result in impaired gas exchange, abnormal vasoreactivity, and pulmonary vascular remodeling that may ultimately lead to pulmonary hypertension (PH). Even infants who appear to have mild BPD suffer from varying degrees of pulmonary vascular disease (PVD). Although recent studies have enhanced our understanding of the pathobiology of PVD and PH in BPD, much remains unknown with respect to how PH should be properly defined, as well as the most accurate methods for the diagnosis and treatment of PH in infants with BPD. This article will provide neonatologists and primary care providers, as well as pediatric cardiologists and pulmonologists, with a review of the pathophysiology of PH in preterm infants with BPD and a summary of current clinical recommendations for managing PH in this population.

Introduction

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), the chronic lung disease associated with premature birth, was first described in infants who required mechanical ventilation and oxygen therapy for postnatal respiratory distress.1 However, advances such as antenatal steroids, artificial surfactant, and improved ventilator strategies have resulted in the increased survival of infants born at extremely low gestational ages.2–4 Thus, although the incidence of BPD has remained relatively stable, both its pathophysiology and its clinical manifestations have changed dramatically over the past 45 years.3,5–7 Whereas classically BPD was characterized by diffuse fibroproliferative lung disease and postnatal lung injury, the “new BPD” consists more prominently of an arrest of pulmonary vascular and alveolar growth.1,8,9 BPD now occurs most commonly in infants born before 28 weeks gestation who typically weigh less than 1000 g at birth.10,11 Birth at these gestational ages results in a disruption in lung development with persistent hypoplasia of the pulmonary microvasculature and alveolar simplification.9,12 Dysmorphic growth and impaired function of the pulmonary vasculature can result in pulmonary hypertension (PH) in infants with BPD.13,14 However, even in infants without clinically apparent PH, signs of pulmonary vascular disease (PVD) such as impaired gas exchange, prolonged hypoxemia, exercise intolerance, and altered distribution of pulmonary blood flow during acute respiratory infections are commonly seen,15 suggesting that PVD may go unrecognized in many infants with BPD.

PH is associated with significant morbidity and mortality in infants with BPD.16–18 Two recent retrospective studies reported a 2 year mortality rate of 33–48% after PH diagnosis.19,20 Yet further studies are needed to understand the pathophysiology of PH in BPD better. Furthermore, standardized criteria are lacking for determining which preterm infants are at greatest risk for developing PH. Although current approaches to the treatment of PH will be reviewed here, significant gaps in our knowledge persist pertaining to the prevention and treatment of PH in this population.

Pathophysiology of PH in BPD

The factors that contribute to the development of PH in infants with BPD are numerous (Fig. 1). Disruption in vascular growth results in decreased vessel density throughout the pulmonary microcapillary network,21,22 which results in decreased cross-sectional area for blood flow and increased pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR). Increased PVR alters vasoreactivity and causes structural remodeling, which contribute to PVD in BPD. The pulmonary vascular bed consists of a smaller overall surface area for gas exchange that, in combination with injury to the airways and lung parenchyma, results in hypoxic vasoconstriction and impaired pulmonary blood flow particularly during exercise or respiratory infections. Chronic hypoxia in the lung tissues also contributes to pulmonary arterial vasoreactivity and ultimately leads to structural remodeling with intimal hyperplasia and increased muscularization of small pulmonary arteries.1,3,9,12,23,24 In its most severe form, the PVD characterized by abnormal vascular growth, vasoreactivity, and structural remodeling can result in PH and its late morbidity and mortality.15

FIG. 1.

Pathophysiology of pulmonary hypertension (PH) in bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD). Prenatal and postnatal factors impair angiogenic signaling, resulting in disrupted vascular growth, abnormal vascular function, and ultimately, PH.

The mechanisms by which PVD occurs after preterm birth remain the subject of ongoing investigation. Vascular growth occurs by two distinct mechanisms: angiogenesis (the direct extension of existing vessels), and vasculogenesis (formation of vessels from primitive hemangioblasts).25 Complex gene–environment interactions, as well as epigenetic influences on gene expression in the setting of prenatal and postnatal factors such as oxidative stress, regional hypoxia, inflammation, and infection, have been shown to impair angiogenesis by disrupting signaling pathways and altering growth factor expression in the developing lung.26–31 For example, expression of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) is epigenetically regulated, increased in the lungs of preterm infants with severe BPD, and is affected by postnatal ventilation strategies that result in histone modification.32–34 In preterm infants, postnatal mechanical ventilation and oxygen therapy result in increased expression of antiangiogenic genes such as thrombospondin-1 and endoglin, as well as decreased expression of proangiogenic genes such as VEGF-B, VEGF receptor-2, and the angiopoietin receptor Tie-2.35,36 Dysregulation of angiogenic signaling leads to impaired growth, structure, and function of the pulmonary vasculature in part through disruption of local and circulating angiogenic progenitor cells.37–41

Perhaps the most studied signaling pathway associated with normal pulmonary vascular development is the vascular endothelial growth factor-nitric oxide (VEGF-NO) pathway.22,42–44 Animal models have shown that disruption of VEGF-NO signaling not only impairs angiogenesis, but also results in alveolar simplification in the distal lung.8,21,22,45 Additionally, the lungs of human infants with fatal BPD have decreased VEGF levels and markedly dysmorphic vasculature.12 Soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1) inhibits this pathway by binding circulating VEGF.46 sFlt-1 is central to the pathogenesis of preeclampsia, a maternal complication of pregnancy and known contributor to BPD risk.47–49 A recent study in neonatal rats showed that antenatal administration of intraamniotic sFlt-1 late in gestation disrupts VEGF-NO signaling in the developing lung, impairs pulmonary vascular and alveolar growth, and leads to postnatal pulmonary hypertension.50 VEGF signaling is also disrupted in animal models of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), another complication of pregnancy that has been associated with an increased risk for PH in infants with BPD.51,52

Through a separate pathway, the vasoconstrictor endothelin-1 (ET-1) activates intracellular Rho-kinase and contributes to impaired pulmonary vascular growth in animal models of PH.53 Many other proangiogenic and antiangiogenic mediators have been described in preclinical models (Table 1). Focused basic research is needed to investigate the complex mechanisms through which these and other growth factor signaling pathways interact to contribute to the pathobiology of PVD in BPD.

Table 1.

List of Proangiogenic and Antiangiogenic Mediators

| Proangiogenic mediators: |

| • Angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1) |

| • Erythropoietin |

| • Fibroblast Growth Factor-1, -2 (FGF-1,2) |

| • Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF) |

| • Kit ligand (stem cell factor) |

| • Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs) |

| • Nitric Oxide (NO) |

| • Placental Growth Factor (PlGF) |

| • Platelet Derived Growth Factor (PDGF) |

| • Prostacyclin (PGI2) |

| • Soluble endoglin |

| • Soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) |

| • Stromal Derived Factor-1 (SDF-1) |

| • Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) |

| • Transforming Growth Factor-beta (TGF-β) |

| • Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) |

| Antiangiogenic mediators: |

| • Angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2) |

| • Angiostatin |

| • Endostatin |

| • Endothelin-1 |

| • Phosphodiesterase Type 5 |

| • Soluble Flt-1 (sFlt) |

| • Thrombospondin-1, -2 |

| • Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP) |

Previous studies suggest circulating and vessel wall-derived endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) contribute to postnatal vasculogenesis.38,41 Two distinct EPC subsets—late-outgrowth endothelial colony-forming cells (ECFCs) and angiogenic circulating progenitor cells (CPCs)—are decreased in the umbilical cord blood of preterm infants who go on to develop moderate or severe BPD.39,54 Yet, it remains unclear whether cord blood ECFC or CPC levels are biomarkers that can predict BPD severity or PH in the clinical setting. Recent small animal studies have shown that ECFCs as well as mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) mediate a pro-angiogenic effect at least in part through paracrine mechanisms.55–58 However, airway-derived MSCs are increased in BPD, suggesting that the tissue of origin (e.g., blood, vascular endothelial wall, bone marrow, airway epithelium) plays a critical and yet undefined role in the pathogenesis of BPD.59 Further studies are needed to describe more clearly how progenitor cell-mediated vasculogenesis is disrupted to cause PVD in BPD and whether progenitor cell therapy will prevent or treat cardiopulmonary disease in preterm infants. Small clinical trials with the most severely affected neonates are the most likely setting in which such novel therapies will be translated into clinical practice.60

The clinical impact of chorioamnionitis on the risk for postnatal complications of premature birth remains unclear.61,62 However, animal models demonstrate that uterine inflammation modulates angiogenesis in the developing lung.63,64 Disrupted nuclear factor kappa B (NFkB) signaling appears to contribute to this process through both inflammatory and noninflammatory pathways.65–67 Pulmonary dendritic cells are increased in both chorioamnionitis and BPD.68 Although they are pro-angiogenic in nature, dendritic cells appear to promote dysmorphic vascular growth in these patients. These studies suggest that perinatal inflammation and immune modulation significantly impact pulmonary vascular development.

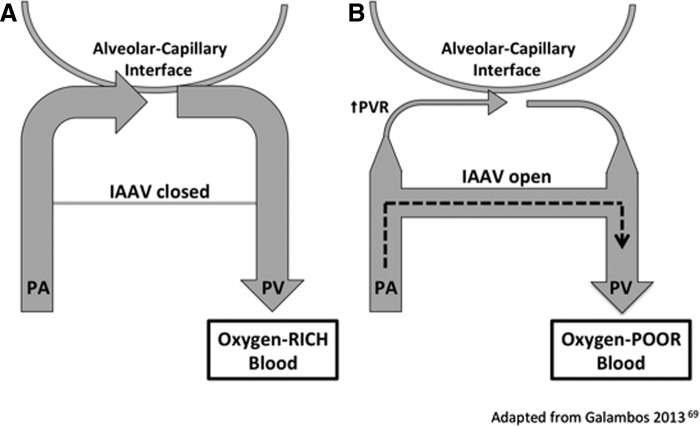

The pulmonary vasculature has recently been shown to contain intrapulmonary arteriovenous anastomotic vessels (IAAV) in preterm infants who died from severe BPD.69 IAAV are small connecting vessels that shunt deoxygenated blood into the pulmonary venous circulation and thus prevent gas exchange at the alveolar–capillary interface (Fig. 2). Such vessels were known to exist during fetal development at late gestation and are similar to those described in alveolar capillary dysplasia, a frequently fatal congenital condition.70,71 However, IAAV are thought to disappear postnatally in healthy newborns.71 IAAV may contribute to severe hypoxemia in infants with severe BPD. It is speculated that these vessels cause regional tissue hypoxia, thus contributing to hypoxic vasoconstriction and structural remodeling in preterm infants who develop PH.

FIG. 2.

(A) In the normal perinatal lung, intrapulmonary arteriovenous anastomotic vessels (IAAV) are closed or nonexistent. Blood from a small pulmonary artery (PA) becomes oxygenated at the alveolar–capillary interface before entering a pulmonary vein (PV). (B) In infants with BPD, deoxygenated blood passes through IAAV before becoming oxygenated in the microcapillary bed causing hypoxemia in these patients.

In summary, preterm birth interrupts pulmonary vascular and alveolar development resulting in decreased cross-sectional area for blood flow and decreased surface area for gas exchange. Vascular simplification, increased vasoreactivity, and hypoxic vasoconstriction lead to increased pulmonary vascular resistance and result in structural remodeling of the pulmonary arterial circulation. Together, these complications of preterm birth contribute to a varying degree of PVD in preterm infants with BPD. Future studies will more clearly elucidate the basic mechanisms responsible for impairments in pulmonary vascular growth and function and will lead to novel therapies for these infants.

Screening and Diagnosis of PH in BPD

It is well known that pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a severe complication of BPD that is associated with high mortality.16,20,72 Although recent studies, both prospective and retrospective, suggest an overall incidence of PH in BPD of 18–25%, such a determination is clouded by the lack of an agreed-upon definition of PH in this context.15,16,73,74 Neither an absolute pulmonary arterial pressure nor a relative pulmonary arterial pressure (typically expressed as a fraction or percentage of systemic blood pressure) has been shown to result in clearly defined consequences. Such criteria, as well as the timing and methodology for screening, vary significantly between centers, and evidence to support one practice over another is lacking.

Cardiac catheterization, an invasive procedure requiring general anesthesia in young children, permits direct measurement of the pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP) and is thus the gold standard for making the diagnosis. However, noninvasive transthoracic echocardiography is more commonly used in children for its ability to estimate the systolic PAP using the tricuspid regurgitation jet velocity (TRJV) and a modified Bernoulli equation to determine the pressure gradient between the right ventricle (RV) and right atrium.75,76 In the absence of tricuspid stenosis or other structural anomalies, the pressure in the RV and pulmonary artery are equal during systole. Qualitative evidence of PH includes flattening of the interventricular septum and hypertrophy/enlargement of the right heart chambers. However, these are not highly predictive of PAH in the absence of a measurable TRJV and are subject to interobserver variability among echocardiographers.77,78 Estimations of severity have been shown to differ substantially between echocardiography and cardiac catheterization.77 Yet, in some cases, unsedated echocardiography could yield more accurate assessments, since cardiac catheterization requires sedation and ventilatory support.

More recently, novel echocardiographic parameters have been utilized to quantify right ventricular dysfunction such as that seen in preterm infants with BPD. The myocardial performance index (or Tei index), a marker of ventricular dysfunction consisting of the sum of isovolumetric contraction and relaxation times divided by the ejection time, is elevated in primary PH, may be elevated in preterm infants with BPD, and may correlate with BPD severity.79–82 More recently, tissue Doppler measurements have been found to correlate with elevated end diastolic pressure in adults. The ratio of the early Doppler inflow velocity to the early myocardial tissue Doppler velocity (E/E′) has been shown to correlate with the severity of BPD, but requires further study to determine if it will be a useful marker of disease.82 The tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) is a marker of RV systolic function that correlates with gestational age, but has not been studied in relation to BPD severity.83–85 Thus, in spite of its limitations, echocardiography will likely remain a key clinical tool for diagnosing and monitoring PH in these children. Prospective studies with long-term follow-up are required to determine appropriate screening and diagnostic criteria for PH in BPD and to determine more clear prognostic implications of PH diagnosis.

Treatment of PH in BPD

PH therapy in the setting of significant BPD begins with optimizing the treatment of the child's chronic lung disease to improve gas exchange. Impaired gas exchange results in hypoxemic vasoconstriction and eventually structural remodeling of the vasculature. Factors contributing to hypoxemia, including bronchospasm and airway obstruction, should be treated appropriately. Flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy may identify tracheobronchomalacia and other causes of airway obstruction. Each child's nutritional status should be optimized to ensure adequate somatic growth. Gastroesophageal reflux and aspiration may require treatment with the consideration of gastric fundoplication in severe cases. In the setting of chronic respiratory failure or insufficiency, long-term mechanical ventilation via tracheostomy should also be considered with the goal of optimizing gas exchange and the neurodevelopmental potential. Once the respiratory status is optimized, selective pulmonary vasodilator therapy can improve the severity of PH in some patients (Table 2). However, randomized controlled trials for the treatment of PH in BPD are lacking to demonstrate the impact of treatment on outcomes. In cases of pulmonary veno-occlusive disease, left ventricular dysfunction, large intracardiac shunts, or collateral vessels, pulmonary vasodilators may be detrimental.86–88 A recent retrospective chart review of 29 infants with PH and BPD revealed that significant cardiovascular anomalies occurred in 65% of these infants, including large aortopulmonary collaterals (31%), patent ductus arteriosus (31%), pulmonary vein stenosis (24%), and others.19 Therefore, cardiac catheterization should be considered to confirm the presence of PH and exclude these other diagnoses prior to initiation of chronic pulmonary vasodilator therapy.88

Table 2.

List of Medications for the Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension

| Medication | Mechanism of vasodilation | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Inhaled nitric oxide | sGC stimulator; increases cGMP | Clinicala |

| Prostacyclin analogues | Adenylate cyclase stimulator; increases cAMP | Clinical |

| Sildenafil, tadalafil | PDE-5 inhibitor; prevents cGMP breakdown | Clinical |

| Bosentan | Nonselective ET-1 receptor antagonist | Clinical |

| Ambrisentan, sitaxsentan | Selective ETA receptor antagonist | Clinical |

| Riociguatb | sGC stimulator; increases cGMP | Experimental |

| Cinaciguat | sGC activator; increases cGMP | Experimental |

| Rosiglitazone | PPAR-gamma activator | Experimental |

| Experimental fasudil | Rho kinase inhibitor | Experimental |

“Clinical” indicates medication is approved for treatment of adult PH; limited safety/efficacy data exist for children.

Riociguat is approved for treatment of adult PH; no safety/efficacy data exist for children.

cGMP, cyclic guanosine monophosphate.

In the setting of acute PH, inhaled nitric oxide (NO), a potent vasodilator, remains the first line of therapy and is the pulmonary vasodilator with the most safety data in infants. Inhaled NO is delivered directly to the pulmonary microvasculature and thus has a very rapid onset of action.89 This also enables the vasodilatory effects of inhaled NO to be most pronounced in well-ventilated lung regions, resulting in decreased ventilation–perfusion mismatch. Inhaled NO is typically administered at an initial dose of 20 ppm, as this dose provides optimal reduction of pulmonary arterial pressure with less risk of methemoglobinemia than higher doses.90 Clinical trials of inhaled NO therapy for the prevention of BPD have shown little benefit, and it remains indicated only in the setting of PH.91

Prostacyclin (PGI2) promotes vasodilation by stimulating the cAMP-dependent relaxation of pulmonary smooth muscle cells.89 PGI2 treatment should be initiated with caution, as it may also cause systemic hypotension. Analogues of PGI2 may be aerosolized or given by either intravenous or subcutaneous infusion.92–94 Due to its very short half-life, the medication must be given continuously, and unplanned interruptions in delivery may be dangerous. Furthermore, the evidence for these medications to treat PH in infants with BPD is limited to case studies and small observations.95–97

The off-label use of enteral phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE-5) inhibitors such as sildenafil has been increasingly used for PH pharmacotherapy in BPD. These medications minimize pulmonary arterial vasoreactivity and may prevent structural remodeling in these vessels. However, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has only approved its use in adults. Although some studies have suggested that sildenafil is both safe and potentially efficacious in children, a recent study reported a dose-related increase in mortality with sildenafil in children with PH secondary to idiopathic PH and congenital heart disease.98–100 This led the FDA to issue a warning against the use of sildenafil in children (www.fda.gov/safety/medwatch/safetyinformation/safetyalertsforhumanmedicalproducts/ucm317743.htm). Importantly, the study by Barst et al. did not evaluate sildenafil therapy for secondary PH in the setting of chronic lung disease. The FDA warning applies to ages 1–17 years, but no recommendations are made for infants during the first year of life. In light of this warning, the Pediatric Pulmonary Hypertension Network (PPHNet) issued a statement emphasizing that sildenafil therapy should be initiated with much caution and high doses avoided until further studies shed more light on the subject.101 In Europe, while the controversy is recognized, sildenafil remains the sole oral agent for PH therapy approved by the European Medicines Agency for use in children.102,103 The sildenafil warning has led to increased use of similar agents such as tadalafil (a long-acting PDE-5 inhibitor). We emphasize that caution should be used with these agents as well, given the lack of long-term follow-up data in children with PH. However, the abrupt cessation of sildenafil or other PH therapies may result in clinical deterioration or death.101

Chronic therapy may also include use of endothelin-1 (ET-1) receptor antagonists. ET-1 acts via two G protein-coupled receptors, ETA (promotes smooth muscle cells proliferation and vasoconstriction), and ETB (promotes proliferation and vasoconstriction, but also mediates vasodilation by release of NO and PGI2 from endothelial cells).104–107 The most commonly used agent, bosentan, a nonselective antagonist of both ETA and ETB receptors, has potent vasodilatory effects.108 Bosentan has been shown to improve pulmonary hypertension in adults and newborns with persistent PH.109,110 Selective ETA receptor blockade with agents such as ambrisentan or sitaxsentan also causes vasodilation with similar effect to nonselective ET-1 receptor antagonists.104 Further study is needed to evaluate the benefit of these medications for treating PH in infants with BPD.

The vasodilatory effects of NO are mediated through stimulation of soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) in the smooth muscle.111 Medications such as riociguat and cinaciguat are now being studied that cause vasodilation by direct stimulation or activation of sGC respectively.112 The FDA recently approved riociguat for the treatment of adult pulmonary hypertension.113 However, these agents may cause dangerous systemic hypotension and have not been studied in infants with BPD.114

Activation of PPARγ by agonists such as rosiglitazone has been shown to treat experimental PH effectively in a number of animal models.115–117 Rosiglitazone has also been shown to prevent experimental BPD in rodents.118–120 However, it is an antidiabetic agent and may have off-target effects that have not been studied.121 Rho-kinase inhibitors such as fasudil improve monocrotaline-induced PH in rats and reduce PVR after ductus arteriosus compression in fetal sheep.122,123 Clinically, fasudil is a potent vasodilator and may become a therapeutic option for treating PH in the future.124 These novel experimental agents have not been studied in infants and are not approved for the treatment of PH in preterm infants. An experienced PH team should be consulted in all severe cases.

Conclusion

In an era of increased survival of the most premature infants, impaired development and function of the pulmonary vasculature play central roles in the pathogenesis of BPD. This results in PVD and secondary PH in many cases. Recent studies have identified many of the mechanisms and factors contributing to impaired pulmonary vascular development in BPD. Although much is known, further study is needed to describe better the intracellular mechanisms and pathophysiologic consequences of PVD and PH in BPD. Universally accepted guidelines for PH screening in this population have not been established. Angiogenic and vascular growth factors have potential to serve as useful biomarkers to identify preterm infants at highest risk of severe disease for targeted therapies before clinical deterioration occurs, but require further study to determine their usefulness. Although the severity of BPD and the presence of PH by current standards are associated with worse outcomes, the relationship of specific echocardiographic findings to clinical outcomes is not entirely clear. In PH secondary to BPD, therapy begins by optimizing gas exchange with the avoidance of intermittent hypoxemia. If PH persists, a number of acute and chronic therapies may help to alleviate symptoms. However, further study is needed to determine the long-term safety and efficacy of these therapies in the clinical setting of BPD.

Acknowledgments

This article was prepared with the support of grant funding from the National Institutes of Health: K12-HL090147-01 (C.D.B.), R01-HL085703 (P.M.M., S.H.A.), R01-HL068702 (S.H.A.), and U01-HL102235 (S.H.A.).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Northway WH, Rosan RC, Porter DY. Pulmonary disease following respirator therapy of hyaline-membrane disease. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. N Engl J Med 1967; 276:357–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baraldi E, Filippone M. Chronic lung disease after premature birth. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:1946–1955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jobe AH. The new BPD: an arrest of lung development. Pediatr Res 1999; 46:641–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kinsella JP, Greenough A, Abman SH. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Lancet 2006; 367:1421–1431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coalson JJ. Pathology of chronic lung disease of early infancy. In: Bland RD, Coalson JJ. (eds). Chronic Lung Disease in Early Infancy. Vol. 137 New York: Marcel Dekker, 1999:85–124 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith VC, Zupancic JA, McCormick MC, et al. Trends in severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia rates between 1994 and 2002. J Pediatr 2005; 146:469–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, et al. Neonatal outcomes of extremely preterm infants from the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics 2010; 126:443–456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abman SH. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia: “a vascular hypothesis.” Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 164:1755–1756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coalson JJ. Pathology of new bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Semin Neonatol 2003; 8:73–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bancalari EH, Jobe AH. The respiratory course of extremely preterm infants: a dilemma for diagnosis and terminology. J Pediatr 2012; 161:585–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charafeddine L, D'Angio CT, Phelps DL. Atypical chronic lung disease patterns in neonates. Pediatrics 1999; 103:759–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhatt AJ, Pryhuber GS, Huyck H, Watkins RH, Metlay LA, Maniscalco WM. Disrupted pulmonary vasculature and decreased vascular endothelial growth factor, Flt-1, and TIE-2 in human infants dying with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 164:1971–1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans NJ, Archer LN. Doppler assessment of pulmonary artery pressure during recovery from hyaline membrane disease. Arch Dis Child 1991; 66:802–804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Subhedar NV, Shaw NJ. Changes in pulmonary arterial pressure in preterm infants with chronic lung disease. Arch Dis Child 2000; 82:F243–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mourani PM, Abman SH. Pulmonary vascular disease in bronchopulmonary dysplasia: pulmonary hypertension and beyond. Curr Opin Pediatr 2013; 25:329–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhat R, Salas AA, Foster C, Carlo WA, Ambalavanan N. Prospective analysis of pulmonary hypertension in extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 2012; 129:e682–689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fouron JC, Le Guennec JC, Villemant D, Perreault G, Davignon A. Value of echocardiography in assessing the outcome of bronchopulmonary dysplasia of the newborn. Pediatrics 1980; 65:529–535 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hislop AA, Haworth SG. Pulmonary vascular damage and the development of cor pulmonale following hyaline membrane disease. Pediatr Pulmonol 1990; 9:152–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Del Cerro MJ, Sabaté Rotés A, Cartón A, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in bronchopulmonary dysplasia: clinical findings, cardiovascular anomalies and outcomes. Pediatr Pulmonol 2014; 49:49–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khemani E, Mcelhinney DB, Rhein L, et al. Pulmonary artery hypertension in formerly premature infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia: clinical features and outcomes in the surfactant era. Pediatrics 2007; 120:1260–1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhatt AJ, Amin SB, Chess PR, Watkins RH, Maniscalco WM. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and Flk-1 in developing and glucocorticoid-treated mouse lung. Pediatr Res 2000; 47:606–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jakkula M, Le Cras TD, Gebb S, et al. Inhibition of angiogenesis decreases alveolarization in the developing rat lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2000; 279:L600–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gorenflo M, Vogel M, Obladen M. Pulmonary vascular changes in bronchopulmonary dysplasia: a clinicopathologic correlation in short- and long-term survivors. Pediatr Pathol 1991; 11:851–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bush A, Busst CM, Knight WB, Hislop AA, Haworth SG, Shinebourne EA. Changes in pulmonary circulation in severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Arch Dis Child 1990; 65:739–745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flamme I, Frölich T, Risau W. Molecular mechanisms of vasculogenesis and embryonic angiogenesis. J Cell Physiol 1997; 173:206–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhandari V, Bizzarro MJ, Shetty A, et al. Familial and genetic susceptibility to major neonatal morbidities in preterm twins. Pediatrics 2006; 117:1901–1906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.D'Angio CT, Maniscalco WM. The role of vascular growth factors in hyperoxia-induced injury to the developing lung. Front Biosci 2002; 7:d1609–1623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar VH, Ryan RM. Growth factors in the fetal and neonatal lung. Front Biosci 2004; 9:464–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thébaud B, Abman SH. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia: where have all the vessels gone? Roles of angiogenic growth factors in chronic lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007; 175:978–985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maniscalco WM, Watkins RH, Pryhuber GS, Bhatt A, Shea C, Huyck H. Angiogenic factors and alveolar vasculature: development and alterations by injury in very premature baboons. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2002; 282:L811–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhandari V, Gruen JR. The genetics of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Semin Perinatol 2006; 30:185–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Albertine KH. Progress in understanding the pathogenesis of BPD using the baboon and sheep models. Semin Perinatol 2013; 37:60–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chetty A, Andersson S, Lassus P, Nielsen HC. Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and IGF-1 receptor (IGF-1R) expression in human lung in RDS and BPD. Pediatr Pulmonol 2004; 37:128–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joss-Moore LA, Metcalfe DB, Albertine KH, McKnight RA, Lane RH. Epigenetics and fetal adaptation to perinatal events: diversity through fidelity. J Anim Sci 2010; 88:E216–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Paepe ME, Greco D, Mao Q. Angiogenesis-related gene expression profiling in ventilated preterm human lungs. Exp Lung Res 2010; 36:399–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Paepe ME, Patel C, Tsai A, Gundavarapu S, Mao Q. Endoglin (CD105) up-regulation in pulmonary microvasculature of ventilated preterm infants. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008; 178:180–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alvarez DF, Huang L, King JA, Elzarrad MK, Yoder MC, Stevens T. Lung microvascular endothelium is enriched with progenitor cells that exhibit vasculogenic capacity. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2007; 294:L419–L430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Asahara T, Murohara T, Sullivan A, et al. Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. Science 1997; 275:964–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baker CD, Balasubramaniam V, Mourani PM, et al. Cord blood angiogenic progenitor cells are decreased in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Eur Respir J 2012; 40:1516–1522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Balasubramaniam V, Mervis CF, Maxey AM, Markham NE, Abman SH. Hyperoxia reduces bone marrow, circulating, and lung endothelial progenitor cells in the developing lung: implications for the pathogenesis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2007; 292:L1073–L1084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ingram DA, Mead LE, Moore DB, Woodard W, Fenoglio A, Yoder MC. Vessel wall-derived endothelial cells rapidly proliferate because they contain a complete hierarchy of endothelial progenitor cells. Blood 2005; 105:2783–2786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bland RD, Albertine KH, Carlton DP, MacRitchie AJ. Inhaled nitric oxide effects on lung structure and function in chronically ventilated preterm lambs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005; 172:899–906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin Y-J, Markham NE, Balasubramaniam V, et al. Inhaled nitric oxide enhances distal lung growth after exposure to hyperoxia in neonatal rats. Pediatr Res 2005; 58:22–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tang J-R, Markham NE, Lin Y-J, et al. Inhaled nitric oxide attenuates pulmonary hypertension and improves lung growth in infant rats after neonatal treatment with a VEGF receptor inhibitor. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2004; 287:L344–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Le Cras TD, Markham NE, Tuder RM, Voelkel NF, Abman SH. Treatment of newborn rats with a VEGF receptor inhibitor causes pulmonary hypertension and abnormal lung structure. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2002; 283:L555–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kendall RL, Thomas KA. Inhibition of vascular endothelial cell growth factor activity by an endogenously encoded soluble receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1993; 90:10705–10709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Foidart JM, Schaaps JP, Chantraine F, Munaut C, Lorquet S. Dysregulation of anti-angiogenic agents (sFlt-1, PLGF, and sEndoglin) in preeclampsia—a step forward but not the definitive answer. J Reprod Immunol 2009; 82:106–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hansen AR, Barnés CM, Folkman J, McElrath TF. Maternal preeclampsia predicts the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Pediatr 2010; 156:532–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Levine RJ, Lam C, Qian C, et al. Soluble endoglin and other circulating antiangiogenic factors in preeclampsia. N Engl J Med 2006; 355:992–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang JR, Karumanchi SA, Seedorf G, Markham N, Abman SH. Excess soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 in amniotic fluid impairs lung growth in rats: linking preeclampsia with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2012; 302:L36–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Check J, Gotteiner N, Liu X, et al. Fetal growth restriction and pulmonary hypertension in premature infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Perinatol 2013; 33:553–557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rozance PJ, Seedorf GJ, Brown A, et al. Intrauterine growth restriction decreases pulmonary alveolar and vessel growth and causes pulmonary artery endothelial cell dysfunction in vitro in fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2011; 301:L860–871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gien J, Tseng N, Seedorf G, Roe G, Abman SH. Endothelin-1 impairs angiogenesis in vitro through Rho-kinase activation after chronic intrauterine pulmonary hypertension in fetal sheep. Pediatr Res 2013; 73:252–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Borghesi A, Massa M, Campanelli R, et al. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells in preterm infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009; 180:540–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aslam M, Baveja R, Liang OD, et al. Bone marrow stromal cells attenuate lung injury in a murine model of neonatal chronic lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009; 180:1122–1130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baker CD, Seedorf GJ, Wisniewski BL, et al. Endothelial colony-forming cell conditioned media promote angiogenesis in vitro and prevent pulmonary hypertension in experimental bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2013; 305:L73–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pierro M, Ionescu L, Montemurro T, et al. Short-term, long-term and paracrine effect of human umbilical cord-derived stem cells in lung injury prevention and repair in experimental bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Thorax 2013; 68:475–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Van Haaften T, Byrne R, Bonnet S, et al. Airway delivery of mesenchymal stem cells prevents arrested alveolar growth in neonatal lung injury in rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009; 1–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Popova AP, Bozyk PD, Bentley JK, et al. Isolation of tracheal aspirate mesenchymal stromal cells predicts bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatrics 2010; 126:e1127–e1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baker CD, Abman SH. Umbilical cord stem cell therapy for bronchopulmonary dysplasia: ready for prime time? Thorax 2013; 68:402–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Been JV, Zimmermann LJ. Exploring the association between chorioamnionitis and respiratory outcome. BJOG 2010; 117:497; author reply 497–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hartling L, Liang Y, Lacaze-Masmonteil T. Chorioamnionitis as a risk factor for bronchopulmonary dysplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child 2012; 97:F8–F17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miller JD, Benjamin JT, Kelly DR, Frank DB, Prince LS. Chorioamnionitis stimulates angiogenesis in saccular stage fetal lungs via CC chemokines. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2010; 298:L637–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tang J-R, Seedorf GJ, Muehlethaler V, et al. Moderate postnatal hyperoxia accelerates lung growth and attenuates pulmonary hypertension in infant rats after exposure to intra-amniotic endotoxin. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2010; 299:L735–748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alvira CM, Abate A, Yang G, Dennery PA, Rabinovitch M. Nuclear factor-kappaB activation in neonatal mouse lung protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007; 175:805–815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Iosef C, Alastalo TP, Hou Y, et al. Inhibiting NF-kappaB in the developing lung disrupts angiogenesis and alveolarization. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2012; 302:L1023–1036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tang JR, Michaelis KA, Nozik-Grayck E, et al. The NF-kappaB inhibitory proteins IkappaBalpha and IkappaBbeta mediate disparate responses to inflammation in fetal pulmonary endothelial cells. J Immunol 2013; 190:2913–2923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.De Paepe ME, Hanley LC, Lacourse Z, Pasquariello T, Mao Q. Pulmonary dendritic cells in lungs of preterm infants: neglected participants in bronchopulmonary dysplasia? Pediatr Devel Pathol 2011; 14:20–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Galambos C, Sims-Lucas S, Abman SH. Histologic evidence of intrapulmonary anastomoses by three-dimensional reconstruction in severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2013; 10:474–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Galambos C, Sims-Lucas S, Abman SH. Three-dimensional reconstruction identifies misaligned pulmonary veins as intrapulmonary shunt vessels in alveolar capillary dysplasia. J Pediatr 2014; 164:192–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McMullan DM, Hanley FL, Cohen GA, Portman MA, Riemer RK. Pulmonary arteriovenous shunting in the normal fetal lung. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004; 44:1497–1500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Walther FJ, Benders MJ, Leighton JO. Persistent pulmonary hypertension in premature neonates with severe respiratory distress syndrome. Pediatrics 1992; 90:899–904 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ali Z, Schmidt P, Dodd J, Jeppesen DL. Predictors of bronchopulmonary dysplasia and pulmonary hypertension in newborn children. Dan Med J 2013; 60:A4688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.An HS, Bae EJ, Kim GB, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in preterm infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Korean Circ J 2010; 40:131–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yock PG, Popp RL. Noninvasive estimation of right ventricular systolic pressure by Doppler ultrasound in patients with tricuspid regurgitation. Circulation 1984; 70:657–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Berger M, Haimowitz A, Van Tosh A, Berdoff RL, Goldberg E. Quantitative assessment of pulmonary hypertension in patients with tricuspid regurgitation using continuous wave Doppler ultrasound. J Am Coll Cardiol 1985; 6:359–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mourani PM, Sontag MK, Younoszai A, Ivy DD, Abman SH. Clinical utility of echocardiography for the diagnosis and management of pulmonary vascular disease in young children with chronic lung disease. Pediatrics 2008; 121:317–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Slaughter JL, Pakrashi T, Jones DE, South AP, Shah TA. Echocardiographic detection of pulmonary hypertension in extremely low birth weight infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia requiring prolonged positive pressure ventilation. J Perinatol 2011; 31:635–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tei C, Dujardin KS, Hodge DO, et al. Doppler echocardiographic index for assessment of global right ventricular function. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 1996; 9:838–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Czernik C, Rhode S, Metze B, Schmalisch G, Buhrer C. Persistently elevated right ventricular index of myocardial performance in preterm infants with incipient bronchopulmonary dysplasia. PloS One 2012; 7:e38352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kazanci E, Karagoz T, Tekinalp G, et al. Myocardial performance index by tissue Doppler in bronchopulmonary dysplasia survivors. Turk J Pediatr 2011; 53:388–396 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yates AR, Welty SE, Gest AL, Cua CL. Myocardial tissue Doppler changes in patients with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Pediatr 2008; 152:766–770, 770 e761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Eriksen BH, Nestaas E, Hole T, Liestol K, Stoylen A, Fugelseth D. Longitudinal assessment of atrioventricular annulus excursion by grey-scale m-mode and colour tissue Doppler imaging in premature infants. Early Hum Dev 2013; 89:977–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kaul S, Tei C, Hopkins JM, Shah PM. Assessment of right ventricular function using two-dimensional echocardiography. Am Heart J 1984; 107:526–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Koestenberger M, Nagel B, Ravekes W, et al. Systolic right ventricular function in preterm and term neonates: reference values of the tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) in 258 patients and calculation of Z-score values. Neonatology 2011; 100:85–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Drossner DM, Kim DW, Maher KO, Mahle WT. Pulmonary vein stenosis: prematurity and associated conditions. Pediatrics 2008; 122:e656–e661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mourani PM, Ivy DD, Rosenberg AA, Fagan TE, Abman SH. Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Pediatr 2008; 152:291–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mourani PM, Mullen M, Abman SH. Pulmonary hypertension in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Prog Pediatr Cardiol 2009; 27:43–48 [Google Scholar]

- 89.Porta NF, Steinhorn RH. Pulmonary vasodilator therapy in the NICU: inhaled nitric oxide, sildenafil, and other pulmonary vasodilating agents. Clin Perinatol 2012; 39:149–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Davidson D, Barefield ES, Kattwinkel J, et al. Inhaled nitric oxide for the early treatment of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the term newborn: a randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled, dose-response, multicenter study. The I-NO/PPHN Study Group. Pediatrics 1998; 101:325–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Donohue PK, Gilmore MM, Cristofalo E, et al. Inhaled nitric oxide in preterm infants: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2011; 127:e414–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bindl L, Fahnenstich H, Peukert U. Aerosolised prostacyclin for pulmonary hypertension in neonates. Arch Dis Child 1994; 71:F214–216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brown AT, Gillespie JV, Miquel-Verges F, et al. Inhaled epoprostenol therapy for pulmonary hypertension: improves oxygenation index more consistently in neonates than in older children. Pulm Circ 2012; 2:61–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Santak B, Schreiber M, Kuen P, Lang D, Radermacher P. Prostacyclin aerosol in an infant with pulmonary hypertension. Eur J Pediatr 1995; 154:233–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Eronen M, Pohjavuori M, Andersson S, Pesonen E, Raivio KO. Prostacyclin treatment for persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Pediatr Cardiol 1997; 18:3–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rugolotto S, Errico G, Beghini R, Ilic S, Richelli C, Padovani EM. Weaning of epoprostenol in a small infant receiving concomitant bosentan for severe pulmonary arterial hypertension secondary to bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Minerva Pediatr 2006; 58:491–494 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zaidi AN, Dettorre MD, Ceneviva GD, Thomas NJ. Epoprostenol and home mechanical ventilation for pulmonary hypertension associated with chronic lung disease. Pediatr Pulmonol 2005; 40:265–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Barst RJ, Ivy DD, Gaitan G, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study of oral sildenafil citrate in treatment-naive children with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 2012; 125:324–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mourani PM, Sontag MK, Ivy DD, Abman SH. Effects of long-term sildenafil treatment for pulmonary hypertension in infants with chronic lung disease. J Pediatr 2009; 154:379–384.e372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nyp M, Sandritter T, Poppinga N, Simon C, Truog WE. Sildenafil citrate, bronchopulmonary dysplasia and disordered pulmonary gas exchange: any benefits? J Perinatol 2012; 32:64–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Abman SH, Kinsella JP, Rosenzweig EB, et al. Implications of the U.S. Food and Drug Association warning against the use of sildenafil for the treatment of pediatric pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 187:572–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wardle AJ, Tulloh RM. Paediatric pulmonary hypertension and sildenafil: current practice and controversies. Arch Dis Child 2013; 98:141–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wardle AJ, Wardle R, Luyt K, Tulloh R. The utility of sildenafil in pulmonary hypertension: a focus on bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Arch Dis Child 2013; 98:613–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Abman SH. Role of endothelin receptor antagonists in the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Ann Rev Med 2009; 60:13–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lüscher TF, Wenzel RR. Endothelin and endothelin antagonists: pharmacology and clinical implications. Agents Actions Suppl 1995; 45:237–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Clozel M, Gray GA, Breu V, Loffler BM, Osterwalder R. The endothelin ETB receptor mediates both vasodilation and vasoconstriction in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Comm 1992; 186:867–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Davie N, Haleen SJ, Upton PD, et al. ET(A) and ET(B) receptors modulate the proliferation of human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 165:398–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Williamson DJ, Wallman LL, Jones R, et al. Hemodynamic effects of Bosentan, an endothelin receptor antagonist, in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 2000; 102:411–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Nakwan N, Choksuchat D, Saksawad R, Thammachote P, Nakwan N. Successful treatment of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn with bosentan. Acta Paediatr 2009; 98:1683–1685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Rubin LJ, Badesch DB, Barst RJ, et al. Bosentan therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:896–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ignarro LJ, Lippton H, Edwards JC, et al. Mechanism of vascular smooth muscle relaxation by organic nitrates, nitrites, nitroprusside and nitric oxide: evidence for the involvement of S-nitrosothiols as active intermediates. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1981; 218:739–749 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Evgenov OV, Pacher P, Schmidt PM, Haskó G, Schmidt HH, Stasch JP. NO-independent stimulators and activators of soluble guanylate cyclase: discovery and therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2006; 5:755–768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Traynor K. Riociguat approved for pulmonary hypertension. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2013; 70:1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Erdmann E, Semigran MJ, Nieminen MS, et al. Cinaciguat, a soluble guanylate cyclase activator, unloads the heart but also causes hypotension in acute decompensated heart failure. Eur Heart J 2013; 34:57–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Crossno JT, Jr, Garat CV, Reusch JE, et al. Rosiglitazone attenuates hypoxia-induced pulmonary arterial remodeling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2007; 292:L885–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kim EK, Lee JH, Oh YM, Lee YS, Lee SD. Rosiglitazone attenuates hypoxia-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension in rats. Respirology 2010; 15:659–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Nisbet RE, Bland JM, Kleinhenz DJ, et al. Rosiglitazone attenuates chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension in a mouse model. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2010; 42:482–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Dasgupta C, Sakurai R, Wang Y, et al. Hyperoxia-induced neonatal rat lung injury involves activation of TGF-{beta} and Wnt signaling and is protected by rosiglitazone. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2009; 296:L1031–1041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lee HJ, Lee YJ, Choi CW, et al. Rosiglitazone, a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonist, restores alveolar and pulmonary vascular development in a rat model of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Yonsei Med J 2014; 55:99–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Rehan VK, Wang Y, Patel S, Santos J, Torday JS. Rosiglitazone, a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonist, prevents hyperoxia-induced neonatal rat lung injury in vivo. Pediatr Pulmonol 2006; 41:558–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Oakes ND, Kennedy CJ, Jenkins AB, Laybutt DR, Chisholm DJ, Kraegen EW. A new antidiabetic agent, BRL 49653, reduces lipid availability and improves insulin action and glucoregulation in the rat. Diabetes 1994; 43:1203–1210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Abe K, Shimokawa H, Morikawa K, et al. Long-term treatment with a Rho-kinase inhibitor improves monocrotaline-induced fatal pulmonary hypertension in rats. Circ Res 2004; 94:385–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Tourneux P, Chester M, Grover T, Abman SH. Fasudil inhibits the myogenic response in the fetal pulmonary circulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2008; 295:H1505–1513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Raja SG. Evaluation of clinical efficacy of fasudil for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Rec Pat Cardiovasc Drug Discov 2012; 7:100–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]