Abstract

Background

Altered glucose-metabolism is the most common metabolic hallmark of malignancies. We tested the hypothesis that glucose-metabolism gene variations affect clinical outcome in pancreatic cancer.

Methods

We retrospectively genotyped 26 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from 5 glucose-metabolism genes in 154 patients with localized disease and validated the findings in 552 patients with different stages of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Association between genotypes and overall survival (OS) was evaluated using multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression models with adjustment for clinical predictors.

Results

Glucokinase (GCK) IVS1+9652C>T and hexokinase (HK)2 N692N homozygous variants were significantly associated with reduced OS in the training set of 154 patients (P < 0.001). These associations were confirmed in the validation set of 552 patients and in the combined dataset of all 706 patients (P ≤ 0.001). In addition, HK2 R844K variant K allele was associated with a better survival in the validation set and the combined dataset (P ≤ 0.001). When data was further analyzed by disease stage, glutamine-fructose-6-phosphate transaminase (GFPT1) IVS14-3094T>C, HK2 N692N and R844K in patients with localized disease, and GCK IVS1+9652C>T in patients with advanced disease were significant independent predictors for OS (P ≤ 0.001). Haplotype CGG of GPI and GCTATGG of HK2 were associated with better OS, respectively, with a P value of 0.004 and 0.007.

Conclusions

We demonstrated that glucose-metabolism gene polymorphisms affect clinical outcome in pancreatic cancer. These observations support a role of abnormal glucose metabolism in pancreatic carcinogenesis.

Keywords: glucose-metabolism, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, single nucleotide polymorphism, overall survival, haplotype

INTRODUCTION

A common property of malignant tumors is altered glucose metabolism. The ‘Warburg effect’ (aerobic glycolysis, a persistently high rate of glucose conversion into lactate even under normoxic condition), is a distinctive metabolic characteristic of malignancies that distinguishes them from normal cells 1. Possibly this effect is an adaptation to intermittent hypoxia in pre-malignant lesions. Enhanced glycolysis at the expense of mitochondrial energy production causing microenvironment-acidosis triggers evolution to phenotypes resistant to acid toxicity, provide precursors for macromolecule biosynthesis and protect cells from excessive toxic reactive oxygen species 2. Subsequent cell populations with intensified glycolysis and acid-resistance have a strong growth-advantage, which promotes malignant proliferation, unrestrained growth, and invasion 3. On the basis of this prominent phenotype, positron emission tomography (PET) imaging has become a major method for cancer detection and surveillance. The worldwide clinical application of PET has resulted in a resurgence of interest in tumor metabolism 4. PET using the glucose analogue tracer 2-[18F]-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FdG) has shown that most cancers profoundly strengthen glucose-uptake, which is dependent on glycolysis rate. FdG-uptake/trapping results from upregulation of glucose transporters and hexokinases (HK1/2) in pancreatic cancer 5, 6. This is a marker that can be used to monitor cancer progression, the augmented glucose-uptake correlates with enhanced tumor aggression, advanced clinical stage, and poorer prognosis 7, 8.

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer mortality in the United States, with an estimated 42,470 new cases and 35,240 deaths in 20099. Pancreatic cancer is one of the most difficult malignancies to treat, with a 5-year survival rate <5% 9. Glucose intolerance and diabetes are common manifestations of pancreatic cancer. Whether and how genetic variations in glucose metabolism affect the clinical outcome of this disease is unknown.

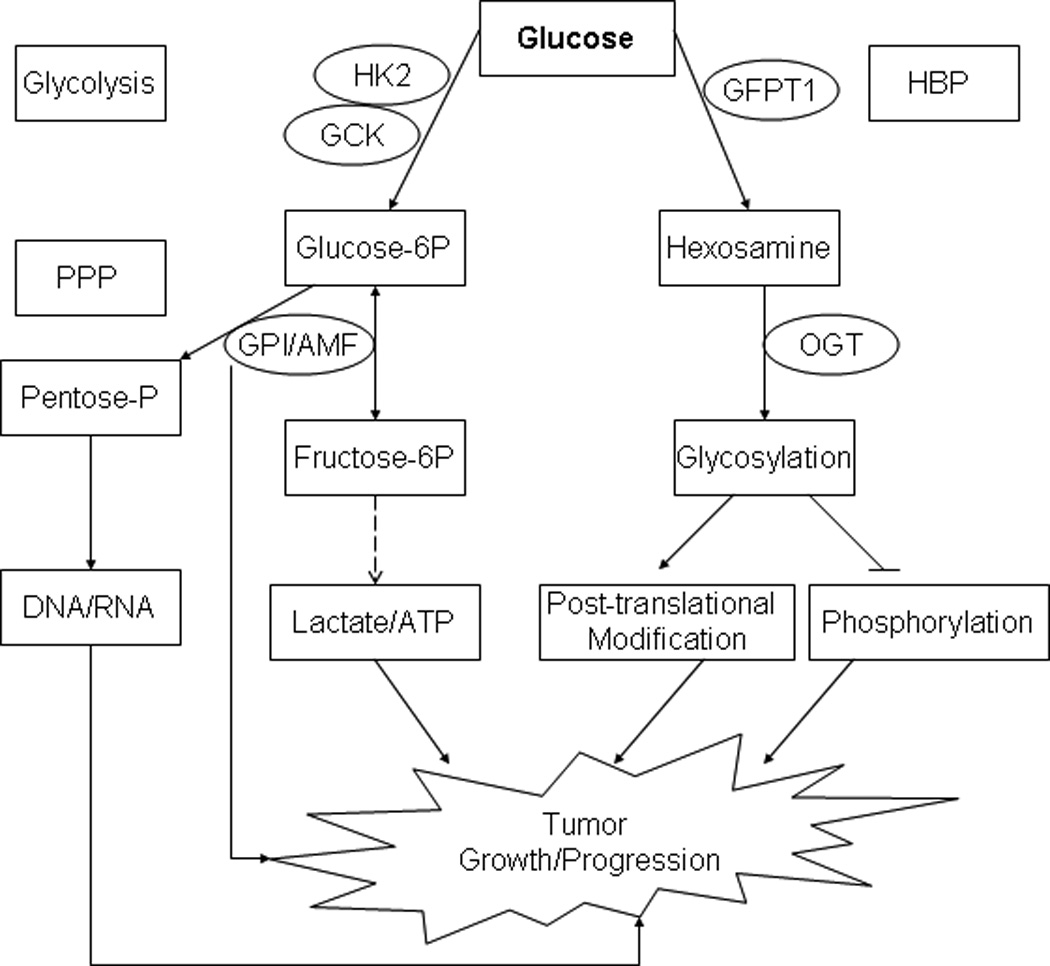

Hexokinase 2 (HK2), glucokinase (GCK), glutamine-fructose-6-phosphate transaminase (GFPT1), glucose phosphate isomerase (GPI), O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) transferase (OGT) are key enzymes involved in glucose metabolism. For its crucial role in determining the cell fate (survival or death) 10 glucose metabolism pathway has become a therapeutic target for cancer treatment 11, with clinical trials on HK2 inhibitors being conducted 12, 13. We have previously shown that obesity and diabetes are associated with reduced overall survival in patients with pancreatic cancer 14, 15. Whether genetic variations in glucose metabolism contribute to the poor clinical outcome of pancreatic cancer has never been explored. To test the hypothesis that genetic variation in glucose-metabolism genes is related to clinical outcome in pancreatic cancer, we evaluated 26 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of GCK, GFPT1, GPI, HK2 and OGT gene (Fig.1.) in reference to the overall survival (OS) and response to chemoradiotherapy in 706 patients with pancreatic cancer.

Fig. 1.

Selected glucose metabolic genes and their potential roles in tumor development. PPP: pentose phosphate pathway. Hexokinases (HK) 2 and GCK/HK4 phosphorylate glucose to produce glucose-6-phosphate (Glucose-6P), the first step in most glucose metabolism pathways including glycolysis 25. GPI (phosphoglucose isomerase) catalyzes the reversible isomerization of Glucose-6P and fructose-6P, and guide the glucose flow to the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) 28. GPI also functions as an autocrine motility factor (AMF), secreted from the tumor cells to promote progression 29. GFPT1 is the first and rate-limiting enzyme of the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway (HBP) and controls the flux of glucose into the hexosamine pathway. OGT is a glycosyltransferase that catalyzes the addition of a single N-acetylglucosamine in O-glycosidic linkage to serine or threonine residues. O-linked glycosylation plays a role in controlling gene expression, fuel metabolism, cell growth, differentiation, and cytoskeleton organization 30.

METHODS

Patient Recruitment and Data Collection

The 706 patients included 154 patients with resectable tumor who were enrolled in clinical trials of preoperative gemcitabine-based chemoradiation 16 and 552 patients who were recruited in a case-control study conducted at The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center from February 1999 to May 2007, with follow-up to August 2009.17 Patients were eligible for the current study if they had a diagnosis of pathologically confirmed pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and had an available DNA sample. All patients signed an informed consent for medical record review and DNA sample collection. The study was approved by the institutional review board of M. D. Anderson Cancer Center and conducted in accordance with all current ethical guidelines.

We reviewed patients’ medical records to collect demographic (age, sex and self-reported race) and clinical information on date of diagnosis, date of death or last follow-up, clinical tumor stage, tumor resection, tumor site, size and differentiation, performance status, serum markers for liver, kidney and pancreas functions, and serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) level at diagnosis. Clinical tumor staging followed the objective computed tomography (CT) criteria: A localized or potentially resectable tumor is defined as a tumor with no evidence of extra-pancreatic disease (extensive peri-pancreatic lymph node involvement), no involvement of the celiac axis and superior mesenteric artery, inferior vena cava, or aorta, or encasement or occlusion of the superior mesenteric vein–portal vein confluence. Tumor abutment and encasement of the SMV, in the absence of vessel occlusion or extension to the SMA was considered resectable. Locally advanced tumors are those unresectable but without distant metastasis. Tumor response to preoperative therapy was evaluated by CT at restaging in patients who had localized tumor and received preoperative chemoradiotherapy. Tumor margin and lymph node status were evaluated in patients with resected tumors only. Dates of death were obtained and cross-checked using the following sources: the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center tumor registry, inpatient medical records, or the United States Social Security Death Index (www.deathindexes.com/ssdi.html). OS time was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of death or last follow-up.

DNA Extraction, SNP Selection and Genotyping

DNA was extracted from peripheral lymphocytes using Qiagen DNA isolation kits (Valencia, CA). Seventeen tagging SNPs were selected using the SNPbrowser software (Applied Biosystems, www.allsnps.com/snpbrowser) with a cutoff of r2=0.8 and a minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥10% in Caucasians from the HapMap Project database (www.hapmap.org). We also included nine coding SNPs (nonsynonymous or synonymous) or untranslated region (UTR) SNPs that have a MAF ≥ 5% in Caucasians. The genes, nucleotide substitutions, function, reference SNP identification numbers, and MAF of the 26 SNPs are described in Table 1. The protein sequences, structures, homology models, mRNA transcripts, and predicted functions for the SNPs were evaluated by F-SNP (Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada) 18. Genotyping used the mass spectroscopy-based MassArray method (Sequenom, Inc, San Diego, CA). We randomly genotyped 20% of total samples in duplicate, showing 99.8% concordance. The inconsistent data were excluded from final analysis.

Table 1.

SNPs Examined and Allele Frequency

| Gene | Chromosome | SNP | Function | RS# | Allele Frequency |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Reported† | |||||

| GCK | 7p15.3-p15.1 | −515G>A | Promoter | rs1799884 | 0.194 | 0.203 |

| IVS1-11823G>A | Intron | rs2908292 | 0.209 | 0.2 | ||

| IVS1+6037T>C | Intron | rs758985 | 0.175 | 0.175 | ||

| IVS1+9652C>T | Intron | rs2300586 | 0.165 | 0.158 | ||

| IVS1+11382G>A | intron | rs2244164 | 0.445 | 0.45 | ||

| IVS3-1489C>T | Intron | rs2268572 | 0.184 | 0.175 | ||

| IVS6+87A>C | intron | rs2268573 | 0.479 | 0.457 | ||

| GFPT1 | 2p13 | IVS12-1764C>T | Intron | rs4625963 | 0.147 | 0.167 |

| IVS14-3094T>C | Intron | rs12466648 | 0.173 | 0.186 | ||

| Ex19-115G>T | 3'UTR | rs2667 | 0.413 | 0.408 | ||

| *4058A>G | 3'Flank | rs13751 | 0.39 | 0.408 | ||

| GPI | 19q13.1 | IVS6-378T>C | Intron | rs8191376 | 0.072 | 0.07 |

| IVS9+2363C>G | Intron | rs7248411 | 0.177 | 0.181 | ||

| Ex6+3A>G | G163G | rs1801015 | 0.07 | 0.103 | ||

| HK2 | 2p13 | IVS1-6165G>A | Intron | rs680545 | 0.446 | 0.45 |

| IVS1+7072C>T | Intron | rs35902493 | 0.352 | 0.38 | ||

| IVS2+3581C>T | Intron | rs3771781 | 0.415 | 0.48 | ||

| Ex1+318A>G | 5'UTR | rs656489 | 0.474 | 0.45 | ||

| Ex4+51A>T | Q142H | rs2229621 | 0.157 | 0.233 | ||

| Ex7+62T>C | D251D | rs2229622 | 0.216 | 0.237 | ||

| Ex15+41C>T | N692N | rs2229626 | 0.398 | 0.408 | ||

| Ex16-78A>G | L766L | rs10194657 | 0.373 | 0.35 | ||

| Ex17-79G>A | R844K | rs2229629 | 0.21 | 0.2 | ||

| Ex18+407T>G | 3'UTR | rs943 | 0.458 | 0.455 | ||

| OGT | Xq13 | IVS8-72G>A | Intron | rs3736670 | 0.151 | 0.142 |

| IVS18-424A>G | Intron | rs6525489 | 0.43 | 0.45 | ||

SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; RS#, reference SNP identification number; UTR, untranslated region.

The reported minor allele frequency was from NCBI dbSNP database.

Statistical Analysis

The distribution of genotypes was tested for Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium with the goodness-of-fit χ2 test. Genotype and allele frequency of the SNP were determined by direct gene counting. Haplotype diversity and linkage disequilibrium index (Lewontin’s D’ and r2) were calculated using SNPAlyze (DYNACOM Co., Ltd. Mobara, Japan). The median follow-up time was computed using censored observations only. The association between genotype/haplotype and OS was evaluated by Cox proportional hazard regression models. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated with adjustment of sex, race and any clinical factors that are significant predictors for OS in multivariate Cox regression models. The association of genotype with categorical variables such as sex, race, and tumor response to therapy was examined using Chi-square test and logistic regression model with adjustment for clinical factors. Statistical analysis used SPSS (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). The false discovery rate (FDR) was calculated using the Beta-Uniform Mixture method 19. For 77 comparisons in a total of 26 SNPs (38 SNPs in dominant and 39 in recessive inheritance modes) for OS in all patients, we found a P value of 0.002 corresponded to an FDR of 5%. Thus, P ≤ 0.002 in the genotype analysis was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patients’ Characteristics

The patients’ demographics and clinical predictors for OS are summarized in Table 2. There were 333 patients with localized disease, 211 with locally advanced disease, and 162 with metastatic disease. Of the 333 patients with localized tumor, 275 (83%) had tumor resection. Of the 706 patients, 138 (19.5%) were alive at the end of the study, with a median follow-up time of 46.0 months. The median survival time (MST) for the entire patient population was 17.2 months (95% CI, 15.8–18.5). Advanced tumor stage, unresected tumor, an elevated CA19-9 serum level or biochemical index, or poor performance status remained as significant predictors for worse OS in multivariate Cox regression models (data not shown).

Table 2.

Linkage Disequilibrium in the 26 SNPs Examined in All Patients

| GCK | −515G>A | IVS1-11823G>A | IVS1+6037T>C | IVS1+9652C>T | IVS1+11382G>A | IVS3-1489C>T | IVS6+87A>C | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −515G>A | |||||||||

| IVS1-11823G>A | 0.4157 | ||||||||

| IVS1+6037T>C | −0.8878 | −0.5018 | |||||||

| IVS1+9652C>T | −0.7179 | −1 | −0.5313 | ||||||

| IVS1+11382G>A | −0.5025 | −0.9529 | 0.6206 | −0.8828 | |||||

| IVS3-1489C>T | −0.4924 | −0.5276 | −0.6385 | 0.8326 | −0.8324 | ||||

| IVS6+87A>C | −0.4134 | −0.6997 | 0.533 | −0.7679 | 0.7684 | −0.8917 | |||

| GFPT1 | IVS12-1764C>T | IVS14-3094T>C | Ex19-115G>T | *4058A>G | |||||

| IVS12-1764C>T | |||||||||

| IVS14-3094T>C | −0.7469 | ||||||||

| Ex19-115G>T | 0.945 | −0.5998 | |||||||

| *4058A>G | 0.91 | −0.7001 | 0.8904 | ||||||

| GPI | IVS6-378T>C | IVS9+2363C>G | G163G | ||||||

| IVS6-378T>C | |||||||||

| IVS9+2363C>G | 0.7961 | ||||||||

| G163G | 0.9285 | 0.775 | |||||||

| HK2 | IVS1-6165G>A | IVS1+7072C>T | IVS2+3581C>T | Ex1+318A>G | Ex4+51A>T | Ex7+62T>C | Ex15+41C>T | Ex16-78A>G | Ex17-79G>A |

| IVS1-6165G>A | |||||||||

| IVS1+7072C>T | −0.4413 | ||||||||

| IVS2+3581C>T | 0.1438 | −0.3931 | |||||||

| Ex1+318A>G | −0.0719 | −4.62E-03 | −0.0611 | ||||||

| Ex4+51A>T | 0.0272 | 0.0772 | 0.0309 | −3.07E-03 | |||||

| Ex7+62T>C | 0.1307 | 4.49E-03 | −0.0983 | 0.0262 | 0.9261 | ||||

| Ex15+41C>T | −2.02E-03 | 0.0337 | −0.0651 | 0.0172 | 0.2625 | 0.1285 | |||

| Ex16-78A>G | −0.1114 | 0.0501 | −0.055 | 0.0334 | −0.5114 | −0.3481 | 0.2414 | ||

| Ex17-79G>A | 0.0564 | 5.33E-03 | −0.2623 | 4.72E-03 | 0.1457 | 0.2392 | −0.5486 | 0.0218 | |

| Ex18+407T>G | −0.0167 | 0.0282 | −0.0639 | 0.0185 | −0.6188 | −0.4502 | 0.3841 | 0.6971 | −0.1156 |

| OGT | IVS8-72G>A | IVS18-424A>G | |||||||

| IVS8-72G>A | |||||||||

| IVS18-424A>G | 0.6425 | ||||||||

Genotype Distribution and Allele Frequencies

The observed allele frequencies in this study population were comparable to the previously reported allele frequencies in the general population (Table 1). The distribution of 26 SNPs followed Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P > 0.05) except for OGT IVS18-424A>G (P = 0.001). Linkage disequilibrium data of the 26 SNPs are described in Table 3. There were significant sex and racial differences in the genotype distributions, e.g. the HK2 N692N CC genotype frequency was 22.4% for men but 10.3% for women (P<0.001), and the HK2 R844K GG genotype frequency was 63.9%, 53.5%, and 25.9% for whites, Hispanics and blacks, respectively (P<0.001) (Data for other SNPs are not shown). Therefore, sex and race were included in all Cox regression models.

Table 3.

Patients’ Characteristics and Clinical Predictors for Overall Survival

| Variable | No. of Patients | No. of Deaths | MST (months) | Plog-rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | .48 | |||

| Female | 281 | 235 | 17.5 | |

| Male | 425 | 333 | 16.8 | |

| Age (years) | .22 | |||

| ≤ 50 | 90 | 80 | 16.4 | |

| 51–60 | 181 | 142 | 18.4 | |

| 61–70 | 272 | 213 | 17.2 | |

| > 70 | 163 | 133 | 16.5 | |

| Race | .63 | |||

| White | 624 | 502 | 16.6 | |

| Hispanic | 43 | 35 | 16.8 | |

| Black | 27 | 21 | 20.2 | |

| Other | 12 | 10 | 17.3 | |

| Clinical Stage | <.001 | |||

| Localized | 333 | 237 | 28.5 | |

| Locally Advanced | 211 | 188 | 14.7 | |

| Metastatic | 162 | 143 | 9.2 | |

| Performance Status | <.001 | |||

| 0 | 148 | 106 | 31.0 | |

| 1 | 483 | 394 | 16.0 | |

| 2–3 | 75 | 68 | 9.5 | |

| Tumor Size (cm) | <.001 | |||

| ≤ 2 | 134 | 94 | 27.5 | |

| > 2 | 572 | 474 | 15.3 | |

| Tumor Site | .001 | |||

| Head | 5117 | 411 | 18.2 | |

| Non-head | 195 | 157 | 13.7 | |

| CA19-9 (U/ml) | <.001 | |||

| ≤ 47 | 161 | 107 | 32.1 | |

| 48–500 | 291 | 237 | 18.0 | |

| 500–1000 | 73 | 60 | 14.5 | |

| > 1000 | 181 | 164 | 10.6 | |

| Tumor Differentiation† | <.001 | |||

| Well to Moderate | 355 | 261 | 26.2 | |

| Poorly | 139 | 120 | 12.0 | |

| Tumor Response to Therapy‡ | <.001 | |||

| PR/SD | 225 | 146 | 35.8 | |

| PD | 36 | 35 | 9.3 | |

| Tumor Resection | <.001 | |||

| Yes | 275 | 179 | 35.9 | |

| No | 431 | 389 | 12.0 | |

| Biochemical Index* | .008 | |||

| 0–2 | 303 | 230 | 18.9 | |

| 3–6 | 362 | 302 | 16.0 | |

| 7–9 | 41 | 36 | 12.9 |

MST, median survival time; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; CA 19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease.

This information was unavailable for patients without proper histological samples.

Tumor response to therapy was evaluated in patients who received preoperative chemoradiotherapy only.

Biochemical index represents the number of serum markers with abnormal value. The markers include aspartate aminotransferase, lactic dehydrogenase, alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase, amylase, creatinine, hemoglobin, albumin, bilirubin, and fasting glucose.

Associations of Genotype with Overall Survival

The association of each genotype with OS was first analyzed in a relatively homogenous population of 154 patients who had resectable tumor and were treated on protocol for preoperative chemoradiotherapy. SNPs with a P value < 0.05 in the multivariate Cox regression models are listed in Table 4. Of the 26 SNPs evaluated, GCK IVS1+9652 C>T and HK2 N692N homozygous mutants were significantly associated with OS at the level of 5% FDR (P < 0.002). The significant associations of both SNPs with OS were confirmed in the validation set of 552 patients (Table 4). In addition, the homozygous K variant of the nonsynonymous SNP HK2 R844K was significantly associated with a better OS in the validation set (P = 0.001). When data of the training set and the validation set was pooled to increase power, the significant associations of GCK IVS1+9652C>T, HK2 N662N and R844K genotype with OS all remained highly significant.

Table 4.

Association of Genotype with Overall Survival

| Training Set |

Validation Set |

Combined dataset |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | No. of Patients /No. of Deaths |

MST | HR (95% CI) † | P | No. of Patients /No. of Deaths |

MST | HR (95% CI) † | P | MST | HR (95% CI) † | P |

| GCK IVS1+9652C>T | |||||||||||

| CC | 111/82 | 26.2 | 1.0 | 380/313 | 16.0 | 1.0 | 17.8 | 1.0 | |||

| CT | 39/32 | 19.8 | 1.56 (1.03–2.38) | .03 | 149/117 | 16.0 | 1.08 (0.87–1.34) | .48 | 16.9 | 1.10 (0.90–1.33) | .35 |

| TT | 2/2 | 5.5 | 18.0 (3.63–89.5) | <.001 | 20/19 | 7.1 | 2.61 (1.61–4.21) | <.001 | 7.1 | 2.69 (1.71–4.22) | <.001 |

| CC vs. CT/TT | 1.61 (1.06–2.45) | .026* | |||||||||

| GFPT1 IVS14-3094T>C | |||||||||||

| TT | 113/85 | 23.9 | 1.0 | 367/295 | 16.9 | 1.0 | 18.0 | 1.0 | |||

| TC | 39/31 | 21.5 | 0.84 (0.54–1.32) | .46 | 152/129 | 13.9 | 1.26 (1.02–1.55) | .03 | 16.0 | 1.25 (1.03–1.50) | .022 |

| CC | 2/2 | 4.9 | 7.64 (1.69–34.6) | .008 | 23/20 | 11.9 | 1.46 (0.91–2.33) | .12 | 11.9 | 1.57 (1.01–2.45) | .045 |

| TT vs. TC/CC | 0.96 (0.61–1.49) | .84* | |||||||||

| GPI IVS9+2363C>G | |||||||||||

| CC | 104/86 | 21.2 | 1.0 | 378/309 | 15.1 | 1.0 | 16.5 | 1.0 | |||

| CG | 43/29 | 27.5 | 0.61 (0.39–0.94) | .027 | 147/120 | 16.4 | 0.88 (0.71–1.09) | .25 | 17.8 | 0.85 (0.70–1.03) | .09 |

| GG | 6/2 | _‡ | 0.11 (0.03–0.48) | .003 | 23/18 | 22.9 | 0.60 (0.36–0.99) | .049 | 27.8 | 0.51 (0.32–0.83) | .006 |

| CC vs. CG/GG | 0.53 (0.34–0.84) | .007* | |||||||||

| GPI G163G | |||||||||||

| AA | 125/98 | 21.2 | 1.0 | 489/403 | 15.2 | 1.0 | 16.4 | 1.0 | |||

| GA | 26/19 | 28.7 | 0.56 (0.34–0.93) | .02 | 59/45 | 20.5 | 0.80 (0.58–1.09) | .16 | 22.0 | 0.77 (0.59–1.02) | .06 |

| GG | 3/1 | _‡ | 0.21 (0.03–1.61) | .13 | 4/2 | 33.7 | 0.32 (0.08–1.33) | .12 | 33.7 | 0.31 (0.10–0.99) | .048 |

| AA vs. GA/GG | 0.52 (0.31–0.86) | .01* | 0.75 (0.55–1.03) | .07* | 0.73 (0.56–0.96) | .02* | |||||

| HK2 N692N | |||||||||||

| TT | 79/49 | 45.1 | 1.0 | 189/143 | 21.4 | 1.0 | 25.1 | 1.0 | |||

| TC | 59/53 | 17.6 | 1.94 (1.24–3.03) | .004 | 255/218 | 15.1 | 1.26 (1.01–1.57) | .037 | 15.3 | 1.39 (1.15–1.69) | .001 |

| CC | 16/16 | 8.3 | 5.62 (2.67–11.8) | <.001 | 108/89 | 12.0 | 1.80 (1.36–2.38) | <.001 | 11.6 | 2.01 (1.55–2.61) | <.001 |

| HK2 L766L | |||||||||||

| GG | 72/54 | 25.7 | 1.0 | 195/155 | 16.4 | 1.0 | 18.2 | 1.0 | |||

| GA | 60/50 | 16.9 | 1.66 (1.10–2.48) | .01 | 291/242 | 15.0 | 1.29 (1.05–1.58) | .01 | 15.7 | 1.29 (1.08–1.55) | .006 |

| AA | 22/14 | 38.5 | 0.71 (0.38–1.30) | .27 | 66/53 | 16.9 | 1.10 (0.80–1.50) | .57 | 18.7 | 0.97 (0.73–1.29) | .85 |

| HK2 R844K | |||||||||||

| GG | 80/67 | 16.9 | 1.0 | 356/297 | 14.2 | 1.0 | 14.6 | 1.0 | |||

| GA | 61/45 | 27.8 | 0.69 (0.46–1.04) | .07 | 182/144 | 18.9 | 0.77 (0.61–0.96) | .02 | 20.5 | 0.76 (0.62–0.93) | .008 |

| AA | 13/6 | _‡ | 0.38 (0.15–0.93) | .03 | 14/9 | 48.5 | 0.31 (0.16–0.63) | .001 | 84.3 | 0.37 (0.21–0.63) | <.001 |

MST, median survival time (months); HR: hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval

HR values were from multivariable Cox regression models including sex, race, tumor resection, CA19-9, performance status, biochemical index and stage when appropriate.

MST can not be calculated.

When the number of sample is less than 10, homozygous and heterozygous mutants were combined.

Next we analyzed the association of each genotype and OS by disease stage. In a total of 333 patients with localized disease, GFPT1-3094T>C, HK2 N692N and R844K were significantly associations with OS (Table 5). The GCK IVS1+9652C>T and HK2 N692N genotype showed some associations with OS among the 211 patients with locally advanced disease but neither reached the significance level (P = 0.027 and 0.013). Among the 162 metastatic patients, GCK IVS1+9652C>T was the only SNP had significant association with OS (P < 0.001). When data was pooled from patients with locally advanced and metastatic disease, GCK IVS1+9652C>T remained as the sole significant genetic predictor for OS (P ≤ 0.001).

Table 5.

Association of Genotype with Overall Survival by Clinical Stage

| Stage | Genotype | No. of Patients /No. of Deaths |

MST | HR (95% CI)† | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Localized | GFPT1 IVS14-3094T>C | ||||

| TT | 239/169 | 28.7 | 1.0 | ||

| TC | 81/58 | 29.8 | 1.12 (0.82–1.53) | .497 | |

| CC | 9/8 | 14.2 | 3.69 (1.69–8.09) | .001 | |

| HK2 N692N | |||||

| TT | 156/93 | 45.1 | 1.0 | ||

| TC | 135/113 | 20.3 | 2.02 (1.51–2.72) | <.001 | |

| CC | 42/31 | 14.7 | 2.53 (1.61–3.97) | <.001 | |

| HK2 R844K | |||||

| GG | 176/133 | 21.2 | 1.0 | ||

| GA | 137/94 | 31.2 | 0.60 (0.45–0.81) | .001 | |

| AA | 20/10 | 90.5 | 0.32 (0.16–0.64) | .001 | |

| Locally Advanced | GCK IVS1+9652C>T | ||||

| CC | 151/137 | 15.0 | 1.0 | ||

| CT | 55/46 | 16.8 | 0.97 (0.68–1.38) | .89 | |

| TT | 5/5 | 7.1 | 3.40 (1.15–10.0) | .027 | |

| CC/CT vs. TT | 1.01 (0.71–1.43) | .958 | |||

| HK2 N692N | |||||

| TT | 64/56 | 20.3 | 1.0 | ||

| TC | 107/95 | 14.2 | 1.36 (0.96–1.91) | .087 | |

| CC | 40/37 | 11.7 | 1.84 (1.16–2.91) | .013 | |

| Metastatic | GFP1*4058A>G | ||||

| GG | 70/63 | 8.37 | 1.0 | ||

| GA | 62/54 | 9.70 | 0.65 (0.44–0.98) | .038 | |

| AA | 21/18 | 10.3 | 0.52 (0.30–0.92) | .025 | |

| GCK IVS1+9652C>T | |||||

| CC | 104/94 | 9.3 | 1.0 | ||

| CT | 46/38 | 9.4 | 1.19 (0.80–1.77) | .40 | |

| TT | 10/10 | 4.4 | 4.13 (2.00–8.52) | <.001 | |

| HK2 Ex18+407T>G | |||||

| GG | 46/37 | 12.2 | 1.0 | ||

| GT | 84/76 | 9.2 | 1.47 (0.96–2.23) | .075 | |

| TT | 30/28 | 8.5 | 1.89 (1.11–3.22) | .019 | |

| Locally Advanced + Metastatic | GCK IVS1+9652C>T | ||||

| CC | 255/231 | 12.3 | 1.0 | ||

| CT | 101/84 | 12.5 | 1.09 (0.85–1.41) | .499 | |

| TT | 15/15 | 6.1 | 3.89 (2.20–6.89) | <.001 | |

| HK2 N692N | |||||

| TT | 112/99 | 13.2 | 1.0 | ||

| TC | 179/158 | 12.1 | 1.04 (0.80–1.35) | .768 | |

| CC | 82/74 | 10.3 | 1.61 (1.16–2.23) | .004 | |

MST, median survival time (months); HR: hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

HR was from multivariable Cox regression model with adjustment of sex, race, tumor resection, CA19-9, performance status, and biochemical index.

MST can not be calculated.

Associations of Haplotype Diversity with OS

Haplotype frequencies and their associations with OS are described in Table 6. The GPI IVS6-378T>C, IVS9+2363C>G and G163G CGG haplotype was associated with a better OS (P = 0.004) and the CCG haplotype with a worse OS (P = 0.01). The different associations with OS of these two haplotypes were obviously determined by the IVS9+2363C>G genotype. Two haplotypes of HK2 gene, i.e. GCTATGG and ATTACAT were associated with a better or worse OS with a P value of 0.007 and 0.03, respectively, in multivariate Cox regression (Table 6). Two other haplotypes, GCCGCAT and ATTGCAT, showed non-significant associations with OS (P = 0.055 and 0.06). Apparently, haplotypes containing CAT of N692N, L766L, and Ex18+407T>G (3’UTR SNP) all conferred a worse OS.

Table 6.

Association of Haplotype Diversity with OS in All Patients

| Haplotype* | Frequency | MST | HR (95% CI)‡ | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GCK | ||||

| GGCCGCA | 0.2337 | 18.4 | 1.0 | |

| GGTCGCA | 0.1248 | 16.5 | 0.96 (0.79–1.18) | .73 |

| GGCTATC | 0.1218 | 16.2 | 1.21 (0.98–1.48) | .078 |

| GGCCACC | 0.098 | 18.7 | 0.93 (0.74–1.17) | .52 |

| AACCACC | 0.0925 | 17.6 | 0.90 (0.72–1.14) | .38 |

| GACCACC | 0.0572 | 17.9 | 1.22 (0.91–1.63) | .18 |

| Others† | 0.272 | 17.3 | 1.05 (0.88–1.25) | .57 |

| GFPT1 | ||||

| TTTG | 0.4165 | 17.6 | 1.0 | |

| TTGA | 0.2162 | 17.6 | 0.97 (0.82–1.13) | .66 |

| TCTG | 0.1468 | 16.0 | 1.16 (0.97–1.38) | .10 |

| CTGA | 0.1288 | 18.1 | 0.93 (0.76–1.13) | .46 |

| TTGG | 0.0358 | 15.3 | 1.20 (0.87–1.66) | .26 |

| Others† | 0.0559 | 18.2 | 0.96 (0.71–1.29) | .77 |

| GPI | ||||

| TCA | 0.808 | 16.6 | 1.0 | |

| TGA | 0.1154 | 16.9 | 0.87 (0.72–1.06) | .17 |

| CGG | 0.0555 | 29.8 | 0.66 (0.49–0.88) | .004 |

| CCG | 0.01 | 13.0 | 2.17 (1.16–4.06) | .01 |

| Others† | 0.0111 | 37.1 | 0.64 (0.33–1.25) | .19 |

| HK2 | ||||

| GCCGTGG | 0.0817 | 16.2 | 1.0 | |

| ATTGTGG | 0.0553 | 16.3 | 1.01 (0.76–1.34) | .93 |

| GCTATGG | 0.0391 | 25.8 | 0.62 (0.44–0.88) | .007 |

| ACCATGG | 0.0353 | 23.9 | 0.85 (0.62–1.17) | .33 |

| ATTACAT | 0.0308 | 13.6 | 1.42 (1.02–1.96) | .03 |

| ACTATGG | 0.0299 | 27.5 | 0.95 (0.62–1.47) | .83 |

| GCCGCAT | 0.028 | 11.7 | 1.46 (0.99–2.14) | .055 |

| ACTGTGG | 0.0247 | 24.6 | 0.92 (0.58–1.44) | .71 |

| GCCATGG | 0.0219 | 21.5 | 1.12 (0.64–1.95) | .70 |

| ATTGCAT | 0.0214 | 14.2 | 1.47 (0.98–2.21) | .06 |

| Others† | 0.6319 | 17.3 | 1.05 (0.87–1.27) | .60 |

| OGT | ||||

| GA | 0.5394 | 17.8 | 1.0 | |

| GG | 0.3098 | 15.4 | 1.09 (0.95–1.24) | .23 |

| AG | 0.1201 | 16.3 | 1.12 (0.92–1.35) | .26 |

| AA | 0.0307 | 18.2 | 0.81 (0.54–1.22) | .31 |

MST, median survival time (months); HR: hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Haplotypes of GCK −515G>A, IVS1-11823G>A, IVS1+6037T>C, IVS1+9652C>T, IVS1+11382G>A, IVS3-1489C>T, IVS6+87A>C; GFPT1 IVS12-1764C>T, IVS14-3094T>C, Ex19-115G>T, 4058A>G; GPI IVS6-378T>C, IVS9+2363C>G, G163G; HK2 IVS1-6165G>A, IVS1+7072C>T, IVS2+3581C>T, Ex1+318A>G, Ex15+41C>T (N692N), Ex16-78A>G (L766L), Ex18+407T>G; and OGT IVS8-72G>A and IVS18-424A>G. Three HK2 genotypes were not included in the haplotype analysis because the major allele was present in each of the haplotype group presented.

HR values were from multivariable Cox regression models including sex, race, clinical stage, tumor resection, CA19-9, performance status and biochemical index.

Others include all the haplotypes with an extremely low frequency.

Associations of Genotype with Other Clinical Parameters

The association between each genotype and tumor response to therapy was evaluated in 261 patients who had resectable tumor and received preoperative chemoradiotherapy. HK2 N692N and R844K genotype showed associations with tumor response (Table 7). Interestingly, the genotype distribution of these two SNPs was significantly different by disease stage and tumor resection status. For example, the HK2 N692N CC genotype was detected in 12.6%, 19.0%, and 25.9% of patients with localized, locally advanced and metastatic disease (P < 0.001, χ2 test). The HK2 R844K GG genotype was present in 52.9% of the patients with localized disease and 69.7% of the patients with advanced disease (P < 0.001, χ2 test).

Table 7.

Association of Genotypes with Other Clinical Parameters

| Variable | Genotype | No. (%) | No. (%) | P (χ2) | OR† (95%CI) | P† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response to Therapy |

PR/SD |

PD |

||||

| HK2 N692N | <.001 | |||||

| TT | 126 (93.3) | 9 (6.7) | 1.0 | |||

| TC | 90 (77.6) | 26 (22.4) | 4.31 (1.84–10.1) | .001 | ||

| CC | 22 (62.9) | 13 (37.1) | 5.96 (2.09–17.0) | .001 | ||

| HK2 R844K | .003 | |||||

| GG | 114 (47.9) | 35 (72.9) | 1.0 | |||

| GA | 105 (44.1) | 13 (27.1) | 0.36 (0.16–0.82) | .015 | ||

| AA | 19 (8.0) | 0 | - | |||

| Tumor Stage |

Localized |

Advanced |

||||

| HK2 N692N | <.001 | |||||

| TT | 156 (46.8) | 112 (30.0) | 1.0 | |||

| TC | 135 (40.5) | 179 (48.0) | 1.57 (1.10–2.25) | .013 | ||

| CC | 42 (12.6) | 82 (22.0) | 2.38 (1.46–3.86) | <.001 | ||

| HK2 R844K | <.001 | |||||

| GG | 176 (52.9) | 260 (69.7) | 1.0 | |||

| GA | 137 (41.1) | 106 (28.4) | 0.43 (0.30–0.64) | <.001 | ||

| AA | 20 (6.0) | 7 (1.9) | 0.29 (0.11–0.78) | .014 | ||

| Tumor Resection |

Resected |

Not resected |

||||

| HK2 N692N | <.001 | |||||

| TT | 146 (53.1) | 122 (28.3) | 1.0 | |||

| TC | 101 (36.7) | 213 (49.4) | 2.29 (1.58–3.31) | <.001 | ||

| CC | 28 (10.2) | 96 (22.3) | 3.62 (2.14–6.14) | <.001 | ||

| HK2 R844K | <.001 | |||||

| GG | 136 (49.5) | 300 (69.6) | 1.0 | |||

| GA | 118 (42.9) | 125 (29.0) | 0.43 (0.29–0.64) | <.001 | ||

| AA | 21 (7.6) | 6 (1.4) | 0.15 (0.05–0.42) | <.001 | ||

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease.

OR and

P value were calculated from logistic regression adjusted for sex, race, CA19-9, performance status, and biochemical index.

DISCUSSION

We identified glucose-metabolism gene variations associated with clinical outcome in pancreatic cancer. GCK IVS1+9652C>T; HK2 N692N, and R844K in all patients, GFPT1 IVS14-3094T>C, HK2 N692N and R844K in patients with localized tumor, and GCK IVS1+9652C>T in patients with advanced diseases were significant independent predictors for OS. We also found a significant association of HK2 N692N and R844K genotype with disease stage, tumor resection status and response to preoperative chemoradiotherapy. These data support a role of glucose-metabolism gene polymorphisms in modifying the clinical outcome in pancreatic cancer.

Hexokinases catalyze the phosphorylation of glucose to glucose-6-phosphate. This is the first and rate-limiting step in glucose metabolism. HK2 localizes to the outer membrane of the mitochondria and is the major hexokinase isoform expressed in cancer cells.20 HK2 expression is insulin-responsive and responsible for the accelerated glycolysis in cancer cells 21. Overexpression of HK2 in tumor tissues has been correlated to poor prognosis in breast cancer and liver cancer but not in pancreatic cancer 7, 22, 23, although the negative finding in pancreatic cancer could be partially explained by the heterogeneity of the study population 23. We observed two HK2 SNPs R844K and N692N, significantly associated with OS, tumor stage, tumor resection status and tumor response to therapy. HK2 R844K, an evolutionary conservative SNP, K variant, is computationally predicted to deleteriously affect protein coding and RNA splicing which change the solvent accessibility and hydrophobicity of the protein 18. The K variant thus, may confer a dysfunctional low enzymatic activity of HK2, impose restraint on glycolysis rate, dampen tumor progression due to lack of energy supply. Indeed, a better response to therapy, a higher tumor resection rate, and a longer OS was observed among patients carrying the K variant allele (GA/AA genotype). The functional significance of the synonymous SNP HK2 N692N is unknown. By computational prediction, such SNP may result in altered conformation, substrate affinity, and mRNA splicing 18. Whether such changes result in a higher enzyme activity, which may explained the association of the variant allele with reduced OS, needs further investigation. We observed the HK2 N692N CC frequency in men was higher than that in women, we inferred CC represents higher enzyme activity, whether the genotype difference contributes to previous report that men had a higher HK enzyme activity than women needs further investigation 24. We also observed that haplotypes containing variant alleles of HK2 N692N, L766L, and Ex18+407T>G (3’-UTR SNP) were associated with worse OS. It is possible that these genotypes/haplotypes conferred a higher level/activity of HK2 that contribute to a higher rate of glycolysis, accelerated tumor progression, and reduced OS.

We found three intronic SNPs were associated with OS, i.e. GCK IVS1+9652 TT genotype in patients with advanced diseases, GFPT1 IVS14-3094T>C in all patients and in patients with localized tumors, and a GPI haplotype containing the IVS9+2363C>G G allele in all patients. GCK is another member of the hexokinase family, catalyzing the ATP-dependent phosphorylation of glucose. Unlike HK2, GCK activity is not inhibited by its product glucose-6-phosphate but remains active while glucose is abundant. GCK plays a role in maintaining glucose homeostasis as the glucose-sensor and glycolysis pacemaker involved in regulating insulin secretion 25. We speculate that there is an increased demand for glucose phosphorylation in advanced tumors because of the rapid cell growth, so GCK is required to maintain a constantly active glucose metabolism. GFPT1 gene encoding the glutamine-fructose-6-phosphate transaminase, the first and rate-limiting enzyme of hexosamine biosynthesis pathway (HBP) controls the glucose flux into HBP. HBP is responsible for shuttling glucose to cellular glycosylation events, e.g., promoting N-linked glycosylation of Wnt-related proteins 26. Glucose flux into HBP initiating post-translational modifications of cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins that regulate signal transduction, transcription, and protein degradation 27. GPI catalyzes the reversible isomerization of glucose-6-phosphate and fructose-6-phosphate, and plays a central role in glycolysis and gluconeogenesis. GPI can guide the glucose flow to the pentose phosphate pathway to produce NADPH and pentose 28. GPI also functions as an autocrine motility factor, secreted from the tumor cells to promote cell migration, progression and metastasis and to help the cells survive and proliferate under hypoxic and nutrient-deprived conditions 29. Although the functional significance of these intron SNPs is unknown, the variant alleles may affect the binding of transcriptional factors to the gene, thus upregulate the mRNA and protein expression 18. The possibility that these SNPs are in linkage with unidentified functional SNPs could not be excluded.

OGT catalyzes the addition of a single N-acetylglucosamine in O-glycosidic linkage to serine or threonine residues. O-linked glycosylation plays a role in controlling gene expression, fuel metabolism, cell growth, differentiation, and cytoskeleton organization 30. We did not observe any significant association of the OGT genotype/haplotype with OS, partly because only 2 SNPs were examined in this study. Further study of this gene is warranted when additional SNPs are revealed by DNA sequencing.

The strength of our study includes detailed clinical information, a large sample size, a two-step design and a hypothesis-driven gene-selection. The limitations of the study include the limited number of genes and SNPs evaluated and the potentially false-positive findings owing to multiple comparisons. To keep the FDR < 5%, we applied a P value of 0.002 as the significance level in the genotype analysis. However, the frequencies of most homozygotes with major effects on clinical outcome are relatively low, so the possibility that these observations are by chance alone cannot be excluded. Additional studies with larger samples in different patient populations are required to confirm these findings. Furthermore, demonstrating the functional significances of these gene traits is pivotal in understanding their role in pancreatic cancer. Nevertheless, our findings provided supporting evidence for the importance of glucose-metabolism pathway in pancreatic cancer. Whether these genetic markers have a potential value in predicting response to glucose-metabolism-targeted therapy in pancreatic cancer is under current investigation.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: National Institutes of Health (NIH) RO1 grant CA098380 (to D.L.), SPORE P20 grant CA101936 (to J.L.A.), NIH Cancer Center Core grant CA16672, Lockton Research Funds (to D.L.).

Footnotes

Financial disclosures: None of the authors have financial disclosures.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors made no disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123:309–314. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vousden KH, Ryan KM. p53 and metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:691–700. doi: 10.1038/nrc2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gatenby RA, Gillies RJ. Why do cancers have high aerobic glycolysis? Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:891–899. doi: 10.1038/nrc1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gambhir SS. Molecular imaging of cancer with positron emission tomography. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:683–693. doi: 10.1038/nrc882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higashi T, Saga T, Nakamoto Y, et al. Relationship between retention index in dual-phase (18)F-FDG PET, and hexokinase-II and glucose transporter-1 expression in pancreatic cancer. J Nucl Med. 2002;43:173–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Natsuizaka M, Ozasa M, Darmanin S, et al. Synergistic up-regulation of Hexokinase-2, glucose transporters and angiogenic factors in pancreatic cancer cells by glucose deprivation and hypoxia. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:3337–3348. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peng SY, Lai PL, Pan HW, et al. Aberrant expression of the glycolytic enzymes aldolase B and type II hexokinase in hepatocellular carcinoma are predictive markers for advanced stage, early recurrence and poor prognosis. Oncol Rep. 2008;19:1045–1053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sperti C, Pasquali C, Chierichetti F, et al. 18-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in predicting survival of patients with pancreatic carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:953–959. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2003.09.002. discussion 959-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hammerman PS, Fox CJ, Thompson CB. Beginnings of a signal-transduction pathway for bioenergetic control of cell survival. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:586–592. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao X, Bloomston M, Zhang T, et al. Synergistic antipancreatic tumor effect by simultaneously targeting hypoxic cancer cells with HSP90 inhibitor and glycolysis inhibitor. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1831–1839. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurtoglu M, Maher JC, Lampidis TJ. Differential toxic mechanisms of 2-deoxy-D-glucose versus 2-fluorodeoxy-D-glucose in hypoxic and normoxic tumor cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:1383–1390. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hulleman E, Kazemier KM, Holleman A, et al. Inhibition of glycolysis modulates prednisolone resistance in acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Blood. 2009;113:2014–2021. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-157842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li D, Morris JS, Liu J, et al. Body mass index and risk, age of onset, and survival in patients with pancreatic cancer. JAMA. 2009;301:2553–2562. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li D, Hassan MM, Abbruzzese JL. Obesity and Survival Among Patients With Pancreatic Cancer--Reply. JAMA. 2009;302:1752-a53. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong X, Jiao L, Li Y, et al. Significant associations of mismatch repair gene polymorphisms with clinical outcome of pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1592–1599. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong X, Javle M, Hess KR, et al. Insulin-like Growth Factor Axis Gene Polymorphisms and Clinical Outcome in Pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterology. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee PH, Shatkay H. F-SNP: computationally predicted functional SNPs for disease association studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D820–D824. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pounds S, Cheng C. Improving false discovery rate estimation. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1737–1745. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathupala SP, Ko YH, Pedersen PL. Hexokinase-2 bound to mitochondria: cancer's stygian link to the "Warburg Effect" and a pivotal target for effective therapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 2009;19:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathupala SP, Rempel A, Pedersen PL. Glucose catabolism in cancer cells: identification and characterization of a marked activation response of the type II hexokinase gene to hypoxic conditions. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43407–43412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108181200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palmieri D, Fitzgerald D, Shreeve SM, et al. Analyses of resected human brain metastases of breast cancer reveal the association between up-regulation of hexokinase 2 and poor prognosis. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:1438–1445. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lyshchik A, Higashi T, Hara T, et al. Expression of glucose transporter-1, hexokinase-II, proliferating cell nuclear antigen and survival of patients with pancreatic cancer. Cancer Invest. 2007;25:154–162. doi: 10.1080/07357900701208931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green HJ, Fraser IG, Ranney DA. Male and female differences in enzyme activities of energy metabolism in vastus lateralis muscle. J Neurol Sci. 1984;65:323–331. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(84)90095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matschinsky FM. Glucokinase as glucose sensor and metabolic signal generator in pancreatic beta-cells and hepatocytes. Diabetes. 1990;39:647–652. doi: 10.2337/diab.39.6.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sethi JK, Vidal-Puig AJ. Wnt signalling at the crossroads of nutritional regulation. Biochem J. 2008;416:e11–e13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20082074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marshall S. Role of insulin, adipocyte hormones, and nutrient-sensing pathways in regulating fuel metabolism and energy homeostasis: a nutritional perspective of diabetes, obesity, and cancer. Sci STKE. 2006;2006:re7. doi: 10.1126/stke.3462006re7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tong X, Zhao F, Thompson CB. The molecular determinants of de novo nucleotide biosynthesis in cancer cells. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niizeki H, Kobayashi M, Horiuchi I, et al. Hypoxia enhances the expression of autocrine motility factor and the motility of human pancreatic cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:1914–1919. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Butkinaree C, Park K, Hart GW. O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc): Extensive crosstalk with phosphorylation to regulate signaling and transcription in response to nutrients and stress. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]