Abstract

Acute respiratory infections (ARIs) are the leading cause of death among children less than 5 years in India. Emergence of newer pathogenic organisms, reemergence of disease previously controlled, wide spread antibiotic resistance, and suboptimal immunization coverage even after many innovative efforts are major factors responsible for high incidence of ARI. Drastic reduction in the burden of ARI by low-cost interventions such as hand washing, breast feeding, availability of rapid and feasible array of diagnostics, and introduction of pentavalent vaccine under National Immunization Schedule which are ongoing are necessary for reduction of ARI.

Keywords: Acute respiratory infections, control of acute respiratory infection, disease burden, National Immunization Schedule, pneumonia, under-5 children, vaccine status

INTRODUCTION

Acute respiratory infections (ARIs) contribute to major disease associated mortality and morbidity among children under 5 years. The existing evidences on ARI are focused on the burden of illness around urban slums and hence lack representative and reliable data resulting in under estimation of ARI prevalence. Shift in the infectious disease etiology from gram positive to gram negative organisms is not well-recognized by health care providers who often under utilize novel rapid diagnostic methods and/or irrationally use antibiotics leading to increased burden of ARI. Although a few studies have claimed efficacy and impact of vaccines (Hemophilus influenza (Hib), pneumococcal vaccines) in reducing the respiratory infections,[1,2,3,4] ignorance and other competing priorities are major hurdles against implementing the newer vaccines in control of ARI. Within these circumstances, this review is focused toward the sensitization on disease burden, etiology, and state of newer vaccines against ARI in India.

METHODS

We searched PubMed, Google Scholar and official web sites of WHO, UNICEF, and MOHFW between 01/01/2013 and 28/02/2013. Articles were restricted to last 15 years pertaining to Indian context. Key words used for search are acute respiratory tract infections, pneumonia, upper respiratory infections, lower respiratory infections, influenza like illnesses, risk factors, and preventive interventions for respiratory illnesses, vaccine efficacy, and zinc prophylaxis. This review is organized in the sequence of current mortality burden, incidence of disease burden from Indian studies, risk factors, and preventive measures.

Mortality

ARIs are the major cause of mortality among children aged less than 5 years especially in developing countries. Worldwide, 20% mortality among children aged less than 5 years is attributed to respiratory tract infections (predominantly pneumonia associated). If we include the neonatal pneumonia also in the pool, the burden comes around to be 35-40% mortality among children aged less than 5 years accounting for 2.04 million deaths/year. Southeast Asia stands first in number for ARI incidence,[5] accounting for more than 80% of all incidences together with sub-Saharan African countries.[6] In India, more than 4 lakh deaths every year are due to pneumonia accounting for 13%-16% of all deaths in the pediatric hospital admissions.[7,8] Million deaths study based on the register general of India mortality statistics had reported 369,000 deaths due to pneumonia among children 1-59 months at the rate of 13.5/1000 live births. More number of deaths due to pneumonia was reported from central India.[9]

Morbidity

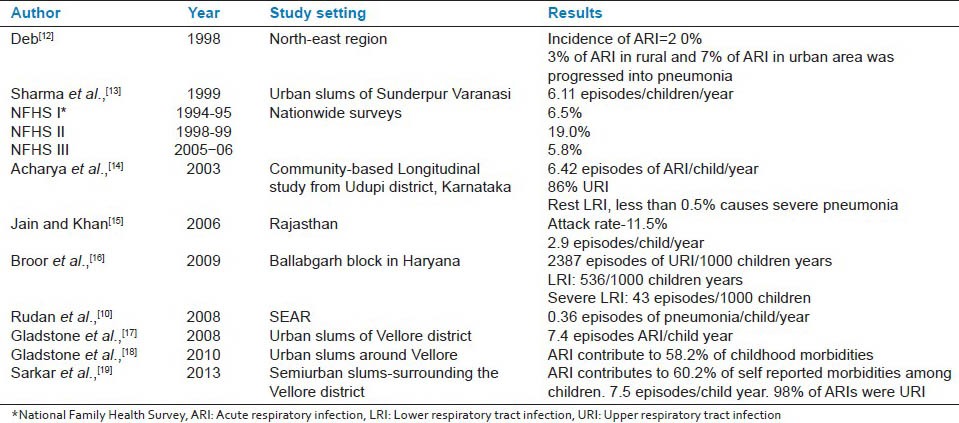

Estimating the morbidity burden has inherent challenges due to lack of uniformity in study definitions, spectral nature of illness and misclassification errors. Recent estimates suggest 3.5% of the global burden of disease is caused by ARI.[10] In developing countries, on an average every child has five episodes of ARI/year accounting for 30%-50% of the total pediatric outpatient visits and 20%-30% of the pediatric admissions.[10] Recent community-based estimates from prospective study report 70% of the childhood morbidities among children aged less than 5 years are due to ARI.[11] While in developing country, a child is likely to have around 0.3 episodes of pneumonia/year, in developed countries it is 0.03 episodes per child/year.[10] On this basis, India is predicted to have over 700 million episodes of ARI and over 52 million episodes of pneumonia every year. A study from Haryana by Broor et al., had reported 2387, 536, and 43 episodes of acute upper respiratory infections, acute lower respiratory infections, and severe acute lower respiratory infections respectively per 1000 child years. Table 1 shows the burden of disease from various parts of India at different periods of time.[10,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]

Table 1.

Incidence of acute respiratory infections in India

It is important to note that ARI include spectrum of severity within it as a result majority of the milder infections may go undetected. Thus incidence of respiratory infections can be relied only from community-based longitudinal cohorts rather than hospital-based studies. Majority of studies regarding etiology of ARI were conducted 2 decades back and studies on etiology at present are lacking. Without representative community-based studies on etiology of ARI, it is difficult to recognize the intensity of this problem. Although some hospital-based studies have shown the emergence of different set of pathogen contributing to significant burden of ARI.[20,21] Also, the reemergence of already controlled diseases such as pertussis has necessitated revision in National Immunization Schedule. Even some of the developed countries have suggest booster dose of acellular pertussis at the age of 10-12 years. Recent evidences from Delhi shows Chlamydia, Escherichia coli, and Mycoplasma cause more than 10% of pneumonia individually, where the past evidences describes them as rare pathogens.[20,21] In clinical practice, this shift in etiology from gram positive to gram negative organisms needs to be considered. Scientific advances in laboratory diagnostic methods like antigen assays, rapid diagnostic kits, and noninvasive procedures like urinary antigen detection test have demonstrated successful identification of respiratory pathogens.[22] In some of the developed countries, the availability of multiplex real time Polymerase chain reaction assays have made diagnosis and etiology identification of ARI efficient. All these advancements are farther from reach of primary health care and even clinical diagnosis of pneumonia and empirical management based on Integrated Management of Neonatal and Childhood Illness (IMNCI) could save more lives.

Risk factors and determinants of ARI

Several small scale community-based studies have reported poor socioeconomic factors; low level of literacy, suboptimal breast feeding, malnutrition, unsatisfactory level of immunization coverage, cooking fuel used other than liquefied petroleum gas as risk factors contributing to increasing burden of ARI among children.[14,23,24]

Prevention and control of respiratory infections

Breast feeding

In developing countries, children who are exclusive breast fed for 6 months had 30%-42% lower incidence of ARI compared to children who did not received for same duration of breast feeding.[25] A recent research report from longitudinal cohort by Mihrshahi et al.,[26] reported the increased risk of ARI (relative risk = 2.3) among children not breast fed adequately. Breast feeding is included under one of the life-saving tool in prevention of various childhood diseases.[27] Hence, breast feeding is among the WHO/UNICEF global action plan to stop pneumonia. In addition, hand washing, improved nutrition, and reduction of indoor air pollution are suggested as primary strategies to protect from pneumonia among children under 5 years age.[5]

Hand washing and respiratory infections

Quantitative systematic review of studies from developed countries estimated hand washing reduces the incidence of respiratory infections by 24% (ranging from 6% to 44%).[28] Evidences from developing countries are lacking on this issue.

Indoor air pollution from solid bio mass fuel

Exposure to indoor air pollution has 2.3 (1.9-2.7) times increased risk of respiratory infections (especially lower respiratory tract infections).[25] Hence, use of cleaner fuels or improvised stoves have proven to be the cost-effective interventions to reduce incidence of indoor air pollution.[29] Million deaths study has also reported increasing prevalence ratio (PR = 1.54 among males, 1.94 among females) of respiratory infections due to use of solid fuel.[30]

Vaccines in preventing respiratory tract infections

Severity and transmissibility of respiratory tract infections by major pathogens, limited availability of laboratory diagnostics, and antibiotic resistance to wide range of drugs makes vaccines as a potential intervention against ARI. While conventional fatality due to pertussis, diphtheria, and measles is reduced by routine immunization, infections due to other bacterial organisms such as H. influenza, Streptococcus pneumonia remains responsible for major burden of the disease. Despite the proven efficacy of vaccines and assistance through Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI), wide scale implementation is lacking due to non availability of community-based studies to establish the evidence of ARI/pneumonia due to above organisms.

Vaccines against pertussis

Reemergence of increasing number of pertussis cases are evident. This has led to the change in National Immunization Schedule to introduce Diphtheria, Pertussiss and Tetanus, (DPT-booster) at 5 years of age instead of Diphtheria and Tetanus DT and raising the upper age limit for DPT vaccine to 7 years of age.[31]

Measles

The recent multiyear strategic plan of India gives an opportunity for Indian children to receive the second dose of measles vaccine. According to this plan, Measles, Mumps and Rubella (MMR) at 15-18 months of age is suggested in states with >80% immunization coverage, while catch up campaigns are suggested in states where less than 80% routine coverage is reported.[31]

Influenza vaccine among children

For children 6-23 months, two doses of trivalent influenza vaccine is recommended if country can afford, make it feasible, and cost-effective analysis is made in favor of vaccination. Children less than 6 months are exempted from vaccination, but protection of mother during pregnancy is recommended as a means to protect these young infants. However, for developing countries appropriate target groups for influenza vaccination is not well-defined.[32]

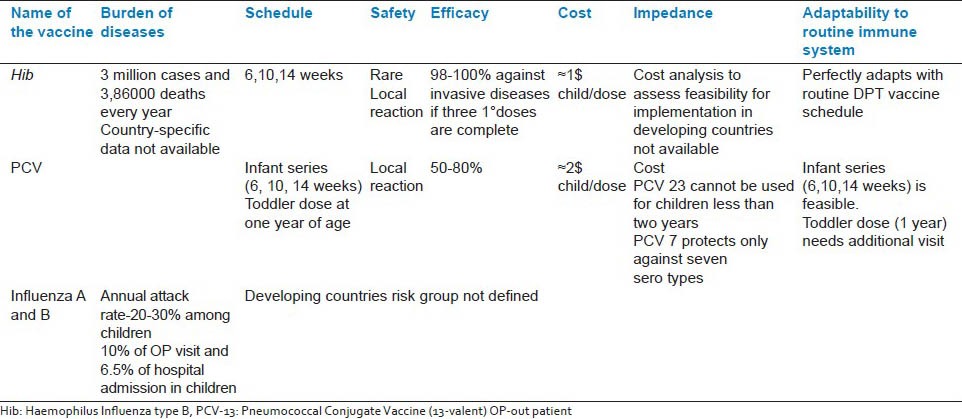

Vaccines against H. influenza-immediate candidate to be included in National Immunization Schedule

More than 95% H. influenza infections occur only among children. According to the recent estimates H. influenza contributes to annual burden of 8.13 million serious illnesses and 371,000 deaths worldwide.[33] From the first H. influenza vaccine trial conducted in 1973-74 showed the efficacy of vaccine against all types of invasive pathogens.[2,34] Conjugated vaccines are shown to be more immunogenic and less reactogenic.[35] Various vaccine trials reported efficacy in the range of 98%-100% after three doses of vaccination, in contrast 35%-47% of the children had low level of immunoglobulin G antibodies against this organism when they did not receive any booster dose.[36] The estimated overall efficacy for three doses of Polyribosylribitol Phosphate-Tetanus Conjugate (Hib) Vaccine was 98.1% (95% confidence interval 97.3%-98.7%).[37] Efficacy in infants aged 5-11 months was 99.1%, 12-23 months 97.3%, and 24-35 months 94.7%. This vaccine not only protects against severe pneumonia but also prevents the colonization, thereby helping in prevention of disease transmission.[38] In spite of its safety, efficacy, feasibility to insert in routine immunization schedule and protection against huge number of avertable deaths most of the developing countries are hesitant to adopt this mode of intervention. Only impediment factor is cost and fear of reactions. Despite financial and technical assistance offered by GAVI introduction of this vaccine in National Immunization Schedule is slow due to questionable affordability toward long-term commitment. A recent study has shed some insight into vaccine safety wherein use of 1.25 μg dose of vaccine has given equivalent sero conversion with less reaction compared to conventional 5 μg doses. This dose reduction can further reduce cost of vaccination.[3]

Pneumococcal vaccines

Scope for inclusion under National Immunization Schedule: Pneumococcal infections alone contribute to 11% of all deaths among children under 5 years of age.[39] Randomized trial reports from nationwide Finish group of children had proven 100% efficacy of vaccine against vaccine serotypes when the 3 + 1 schedule (6, 10, 14 weeks infant series and 1 year post toddler) was adopted.[40] Vaccine efficacy against this 2 + 1 schedule was reported to be 92%.[41] Safety profiles were confirmed from many trials including the recent trial reported from 12 sites in India.[41,42,43] Like Hib vaccines, this also prevents colonization thereby facilitates the protection against the disease transmission.[44,45] While the currently available PCV 7 gives protection against only seven serotypes, rest of the serotypes are left out. Unfortunately, vaccine which covers all 23 serotypes cannot be used among children under 2 years which is a most vulnerable period to get this disease. To widen the protection against additional serotypes PCV-13 is suggested. Trial reports from various countries again confirmed the safety profile and added protection by PCV13 compared to PCV 7.[42] However, issues on revaccination of children in 5 years age group remains a challenge. With these scientific evidences, political commitment toward acceptance for inclusion under routine vaccination is yet to be achieved.

MMR and chickenpox vaccine

Secondary pneumonia due to exanthematous illnesses like measles and chicken pox are next common cause for ARI among children. Despite their high incidence, prevention efforts with these vaccines are not under priority since other vaccines like H. influenza, Hep B are yet to be included in nationwide plan. Varicella and MMR can be given in two ways. Giving vaccines to adolescents and adults alone will protect the vulnerable group without changing the epidemiology of disease. Vaccination of children without focusing for high coverage level (coverage < 80%) will result in epidemiological shift leading to onset of cases (rubella and varicella) at adult age group which is more harmful than the existing scenario. For countries like India where second dose of measles is proposed recently (MMR at the age of 15-18 months) is recommended with emphasis on high coverage. Vaccine against varicella is not recommended at present under National Immunization Schedule considering the other priorities. Adults who are at risk of contacting varicella are advised to get vaccinated within 48 hrs of exposure. This prophylactic method has the proven efficacy of 90%.[46,47]

Mile stones in control of ARI in India

On the basis of burden and effectiveness of simple primary health care interventions shown from the field, ARI control program was started in India during 1990. Since then, various community-based interventions are implemented under ARI control program. Identification of severe respiratory infections by health care worker from rural area, wide access to antibiotics, and its administration by health care workers, was seen as a successful model [Gadchiroli project, management of childhood illness by holistic approach of IMNCI]. Increasing coverage of vaccines against major vaccine-preventable diseases through various strategies under National Rural Health Mission, measles second dose implementation and newer introduction of pentavalent vaccines are the major primary health care measures currently implemented in India. Table 2 shows the factors favoring introduction of these newer vaccines under National Immunization Schedule. Algorithm development and respiratory tract infection group education modules are the major steps taken by professional bodies toward management of ARI and irrational use of antibiotics.

Table 2.

Vaccines against major respiratory pathogens

Role of zinc in prevention of ARI

Controversial evidences are reported over the effect of zinc in prevention of ARI. While some of the evidences support its impact on reducing acute lower respiratory tract infections[48] other studies contradict this.[49,50] Considering the tolerability and high threshold for toxic effects, the further recommendations on zinc in ARI will be based on the conclusions from ongoing community trials. However, global action plan to prevent pneumonia by WHO/UNICEF insists on routine zinc prophylaxis for children affected by acute diarrheal diseases.

For developing countries to take decision on various modes of interventions against ARI, cost-effective analysis is necessary. The assessment of various interventions against ARI has shown the high impact from interventions like breast feeding, zinc prophylaxis, access to clean fuel for cooking, and community/facility-based case management. These interventions are applicable even in resource poor settings to combat the burden of ARI drastically.[51]

CONCLUSION

Incidence of respiratory infections cannot be reduced without an overall increase in social and economic development. But enormous evidences have shown various measures to reduce this disease mortality. Every reduction in death due to ARI would give an incremental benefit toward achieving the Millennium Development Goal (MDG 4). Final step toward control of ARI would be commitment to implement these proven and evidence-based interventions.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Swingler G, Fransman D, Hussey G. Conjugate vaccines for preventing Haemophilus influenzae type B infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;18:CD001729. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001729.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vadheim CM, Greenberg DP, Partridge S, Jing J, Ward JI. Effectiveness and safety of an Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine (PRP-T) in young infants. Kaiser-UCLA Vaccine Study Group. Pediatrics. 1993;92:272–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Punjabi NH, Richie EL, Simanjuntak CH, Harjanto SJ, Wangsasaputra F, Arjoso S, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of four different doses of Haemophilus influenzae type b-tetanus toxoid conjugated vaccine, combined with diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine (DTP-Hib), in Indonesian infants. Vaccine. 2006;24:1776–85. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amdekar YK, Lalwani SK, Bavdekar A, Balasubramanian S, Chhatwal J, Bhat SR, et al. Immunogenicity and Safety of a 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine in Healthy Infants and Toddlers Given with Routine Vaccines in India. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012 doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31827b478d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wardlaw TM, Johansson EW, Hodge MJ. UNICEF; 2006. [Last accessed on 2013 Mar 13]. World Health Organization. Pneumonia: The Forgott en Killer of Children. Available from: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/9280640489/en . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Unicef; 2008. [Last accessed on 2013 Mar 13]. The State of Asia-Pacific's Children 2008: Child Survival. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/sapc08/report/report.php . [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain N, Lodha R, Kabra SK. Upper respiratory tract infections. Indian J Pediatr. 2001;68:1135–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02722930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vashishtha VM. Current status of tuberculosis and acute respiratory infections in India: Much more needs to be done! Indian Pediatr. 2010;47:88–9. doi: 10.1007/s13312-010-0005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Causes of neonatal and child mortality in India: A nationally representative mortality survey-Causes-of-neonatal-and-childmortality-in-India-2010.pdf. [Last accessed on 2013 Mar 11]. Available from: http://cghr.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/Causes-of-neonatal-andchild-mortality-in-India-2010.pdf .

- 10.Rudan I, Boschi-Pinto C, Biloglav Z, Mulholland K, Campbell H. Epidemiology and etiology of childhood pneumonia. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:408–16. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.048769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dongre AR, Deshmukh PR, Garg BS. Health expenditure and care seeking on acute child morbidities in peri-urban Wardha: A prospective study. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:503–7. doi: 10.1007/s12098-010-0063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deb SK. Acute respiratory disease survey in Tripura in case of children below five years of age. J Indian Med Assoc. 1998;96:111–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma AK, Reddy DC, Dwivedi RR. Descriptive epidemiology of acute respiratory infections among under five children in an urban slum area. Indian J Public Health. 1999;43:156–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Acharya D, Prasanna KS, Nair S, Rao RS. Acute respiratory infections in children: A community based longitudinal study in south India. Indian J Public Health. 2003;47:7–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jain SK, Khan JA. Epidemiological study of acute diarrhoeal disease and acute respiratory infection amongst under-five children in Alwar district (Rajasthan), India. Indian J Practising Doctor. 2006;3(5):11–2. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Broor S, Parveen S, Bharaj P, Prasad VS, Srinivasulu KN, Sumanth KM, et al. A prospective three-year cohort study of the epidemiology and virology of acute respiratory infections of children in rural India. PLoS One. 2007;2:e491. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gladstone BP, Das AR, Rehman AM, Jaffar S, Estes MK, Muliyil J, et al. Burden of illness in the first 3 years of life in an Indian slum. J Trop Pediatr. 2010;56:221–6. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmp116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gladstone BP, Muliyil JP, Jaffar S, Wheeler JG, Le Fevre A, Iturriza-Gomara M, et al. Infant morbidity in an Indian slum birth cohort. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:479–84. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.114546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sarkar R, Sivarathinaswamy P, Thangaraj B, Sindhu KN, Ajjampur SS, Muliyil J, et al. Burden of childhood diseases and malnutrition in a semi-urban slum in southern India. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:87. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taneja J, Malik A, Malik A, Rizvi M, Agarwal M. Acute lower respiratory tract infections in children. Indian Pediatr. 2009;46:509–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kabra SK, Lodha R, Broor S, Chaudhary R, Ghosh M, Maitreyi RS. Etiology of acute lower respiratory tract infection. Indian J Pediatr. 2003;70:33–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02722742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith MD, Derrington P, Evans R, Creek M, Morris R, Dance DA, et al. Rapid diagnosis of bacteremic pneumococcal infections in adults by using the Binax NOW Streptococcus pneumoniae urinary antigen test: A prospective, controlled clinical evaluation. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:2810–3. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.7.2810-2813.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Savitha MR, Nandeeshwara SB, Kumar MJ, ul-Haque F, Raju CK. Modifiable risk factors for acute lower respiratory tract infections. Indian J Pediatr. 2007;74:477–82. doi: 10.1007/s12098-007-0081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Broor S, Pandey RM, Ghosh M, Maitreyi RS, Lodha R, Singhal T, et al. Risk factors for severe acute lower respiratory tract infection under-five children. Indian Pediatr. 2001;38:1361–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ladomenou F, Moschandreas J, Kafatos A, Tselentis Y, Galanakis E. Protective effect of exclusive breastfeeding against infections during infancy: A prospective study. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:1004–8. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.169912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mihrshahi S, Oddy WH, Peat JK, Kabir I. Association between infant feeding patterns and diarrhoeal and respiratory illness: A cohort study in Chittagong, Bangladesh. Int Breastfeed J. 2008;3:28. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-3-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Avery ME, Snyder J. GOBI-FFF: UNICEF-WHO initiatives for child survival. AAP News. 1989;5:5–15. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiley Online Library; [Last accessed on 2013 Mar 11]. Handwashing and risk of respiratory infections: A quantitative systematic review-Rabie-2006-Tropical Medicine and International Health. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j. 1365-3156.2006.01568.x/pdf . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nigel Paper 7 Aug.PDF-OEH02.5.pdf. [Last accessed on 2013 Mar 11]. Available from: http://www.bioenergylists.org/stovesdoc/Environment/WHO/OEH02.5.pdf .

- 30.Child mortality from solid-fuel use in India: A nationally-representative case-control study-Child- mortality-from-solid-fuel-use-in-India-2010.pdf. [Last accessed on 2013 Mar 11]. Available from: http://cghr.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/Child-mortality-from-solid-fuel-use-in-India-2010.pdf . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.National Vaccine Policy Book. Cdr-1084811197national Vaccine Policy Book.pdf. [Last accessed on 2013 Mar 14]. Avaialable from: http://mohfw.nic.in/WriteReadData/l892s/1084811197NATIONAL%20VACCINE%20POLICY%20BOOK.pdf .

- 32.wer8033influenza_August2005_position_paper.pdf. [Last accessed on 2013 Mar 15]. Available from: http://www.who.int/immunization/wer8033influenza_August2005_position_paper.pdf .

- 33.Watt JP, Wolfson LJ, O’Brien KL, Henkle E, Deloria-Knoll M, McCall N, et al. Hib and Pneumococcal Global Burden of Disease Study Team. Burden of disease caused by Haemophilus influenzae type b in children younger than 5 years: Global estimates. Lancet. 2009;374:903–11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eskola J, Peltola H, Takala AK, Käyhty H, Hakulinen M, Karanko V, et al. Efficacy of Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharide-diphtheria toxoid conjugate vaccine in infancy. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:717–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198709173171201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Force RW, Lugo RA, Nahata MC. Haemophilus influenzae type B conjugate vaccines. Ann Pharmacother. 1992;26:1429–40. doi: 10.1177/106002809202601117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scheifele D, Law B, Mitchell L, Ochnio J. Study of booster doses of two Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccines including their interchangeability. Vaccine. 1996;14:1399–406. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fritzell B, Plotkin S. Efficacy and safety of a Haemophilus influenzae type b capsular polysaccharide-tetanus protein conjugate vaccine. J Pediatr. 1992;121:355–62. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81786-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adegbola RA, Mulholland EK, Secka O, Jaffar S, Greenwood BM. Vaccination with a Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine reduces oropharyngeal carriage of H. influenzae type b among Gambian children. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1758–61. doi: 10.1086/517440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Brien KL, Wolfson LJ, Watt JP, Henkle E, Deloria-Knoll M, McCall N, et al. Hib and Pneumococcal Global Burden of Disease Study Team. Burden of disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in children younger than 5 years: Global estimates. Lancet. 2009;374:893–902. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Madhi SA, Cohen C, von Gottberg A. Introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine into the public immunization program in South Africa: Translating research into policy. Vaccine. 2012;30:C21–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palmu AA, Jokinen J, Borys D, Nieminen H, Ruokokoski E, Siira L, et al. Effectiveness of the ten-valent pneumococcal Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine (PHiD-CV10) against invasive pneumococcal disease: A cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;381:214–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61854-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Durando P, Alicino C, De Florentiis D, Martini M, Icardi G. Improving the protection against Streptococcus pneumoniae with the new generation 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. J Prev Med Hyg. 2012;53:68–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.WHO Publication, Pneumococcal vaccines WHO position paper-2012-recommendations. Vaccine. 2012;30:4717–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.04.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ota MO, Roca A, Bottomley C, Hill PC, Egere U, Greenwood B, et al. Pneumococcal antibody concentrations of subjects in communities fully or partially vaccinated with a seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42997. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Egere U, Townend J, Roca A, Akinsanya A, Bojang A, Nsekpong D, et al. Indirect effect of 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on pneumococcal carriage in newborns in rural Gambia: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49143. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.C: AtarpaoREH12 eh32.PDF-wer7332varicella_Aug98_position_paper.pdf. [Last accessed on 2013 Mar 20]. Available from: http://www.who.int/immunization/wer7332varicella_Aug98_position_paper.pdf .

- 47.IndianJPublicHealth564269-858983_235138.pdf. [Last accessed on 2013 Mar 20]. Available from: http://www.ijph.in/temp/IndianJPublicHealth564269-858983_235138.pdf .

- 48.Roth DE, Richard SA, Black RE. Zinc supplementation for the prevention of acute lower respiratory infection in children in developing countries: Meta-analysis and meta-regression of randomized trials. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:795–808. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Srinivasan MG, Ndeezi G, Mboijana CK, Kiguli S, Bimenya GS, Nankabirwa V, et al. Zinc adjunct therapy reduces case fatality in severe childhood pneumonia: A randomized double blind placebo-controlled trial. BMC Med. 2012;10:14. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-10-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haider BA, Lassi ZS, Ahmed A, Bhutta ZA. Zinc supplementation as an adjunct to antibiotics in the treatment of pneumonia in children 2 to 59 months of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;10:CD007368. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007368.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Niessen LW, ten Hove A, Hilderink H, Weber M, Mulholland K, Ezzati M. Comparative impact assessment of child pneumonia interventions. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:472–80. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.050872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]