Abstract

Oral cancer has a well characterized progression from premalignant oral epithelial changes to invasive cancer, making oral squamous cell carcinoma an optimal disease for chemoprevention interventions prior to malignant transformation. The primary goal of chemoprevention here is to reverse, suppress, or inhibit the progression of premalignant lesions to cancer. Due to the extended duration of oral pathogenesis, its chemoprevention using natural products has been found promising due to their decreased dose and limited toxicity profiles. This review discusses with an emphasis on the clinical trials using green tea extract (GTE) in chemoprevention of oral premalignant lesions along with use of GTE as a chemopreventive agent in various other cancers as well. It is worthwhile to include green tea extract in an oral screening program for evaluating the premalignant lesions comparing the results between the treated and untreated group. Given the wide acceptance of green tea, its benefits may help in effective chemoprevention oral cancer.

Keywords: Chemoprevention, epigallocatechin-3-gallate, green tea extract

INTRODUCTION

Chemoprevention is a novel approach to cancer control using specific natural products or synthetic agents for suppression, reversal, or prevention of premalignant transformation of cells to a malignant form.[1]

An ideal chemopreventive agent must have no toxicity, must have high efficacy in multiple sites, should have a low cost, preferred oral consumption, a known mechanism of action, and most important aspect of human acceptance.[2] Several studies have shown the natural products, especially antioxidants present in food and beverages have various health benefits with no side effects and toxicity compared to the limitations of other chemotherapeutic agents.[3] Natural products are composed of a wide spectrum of biologically active phytochemicals like phenolics, flavonoids, carotenoids, alkaloids, and nitrogen that can suppress the early and late stages of tumorigenesis. The process of carcinogenesis is a multistage process with phases of initiation, promotion, and progression. It is therefore possible to intervene and prevent the process of carcinogenesis during these phases. Since it takes several years to reach the invasive stage of an epithelial carcinogenesis; progression of precancerous lesion can be stabilized, arrested, or reversed by chemoprevention strategies

Both green tea and black tea have been studied for their chemopreventive potential and green tea has shown greater promise and efficacy against multiple cancers. Also, green tea has a ready availability and low toxicity.

Oral cancer is a heterogeneous group of cancers arising from different parts of the oral cavity with different predisposing factors, prevalence, and treatment outcomes. It is the sixth most common cancer reported globally with an annual incidence of over 300,000 cases and an increase of 62% has been reported in the developing countries. Among smokers, the prevalence of oral tumors is 4-7 times higher than nonsmokers and if alcohol or chewing tobacco is added to the cigarette usage, the incidence of oral cancer is increased by 19- and 123-folds, respectively.[4] The tobacco carcinogens affect large fields of upper aerodigestive tract mucosa during decades of their usage, causing accumulations of genetic alterations that are involved in tumorigenesis. High incidence of oral cancer in India is attributed to use of tobacco both smoking and chewing and/or alcohol intake. High statistics of the disease and delayed presentation of patients at the time of primary diagnosis of oral cancers; underscores the need for awareness, early detection, and chemoprevention strategies. In the recent years, infection with human papilloma virus (HPV), particularly HPV 16 has been suggested as an etiologic factor especially among the nonsmokers and nonalcoholics.

Green tea is derived from the plant Camellia sinensis and is mostly consumed next to water. It has shown scientifically proven beneficial health benefits. Green tea comprises of polyphenols constituting 36% of dry tea leaf weight,[5] glycosides, leucoanthocyanins, and phenolic acid. Green tea contains four major polyphenols: Epicatechin (EC), epigallocatechin (EGC), epicatechin-3-gallate (ECG), epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), composing 1-3%, 3-6%, 3-6%, and 3-7%, respectively of the fresh green tea leaf dry weight.[6] The polyphenols found abundantly in green tea have been shown to inhibit a variety of processes associated with cancer cell growth, survival as well as metastasis. Several studies have shown benefits of green tea pertaining to its antiviral, antiinflammatory, and antiallergic effects.[7,8]

MOLECULAR MECHANISMS IN CANCER PREVENTION PROMOTED BY GREEN TEA

Protective effects of green tea intake against cancer incidence have been shown by a large population-based prospective cohort study.[9] This kind of epidemiology study has spurred intense basic science research of green tea and its components. The implications on the anticancer activity are reported to be on important enzymes like urokinase.[10] Ornithine decarboxylase, NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase, protein kinase C, steroid 5-alpha reductase,[11] tumor necrosis factor expression,[12] and nitric oxide synthase.[13] Anticancer effects through pathways of antiangiogenesis[14] and inhibition of telomerase have also been shown previously.

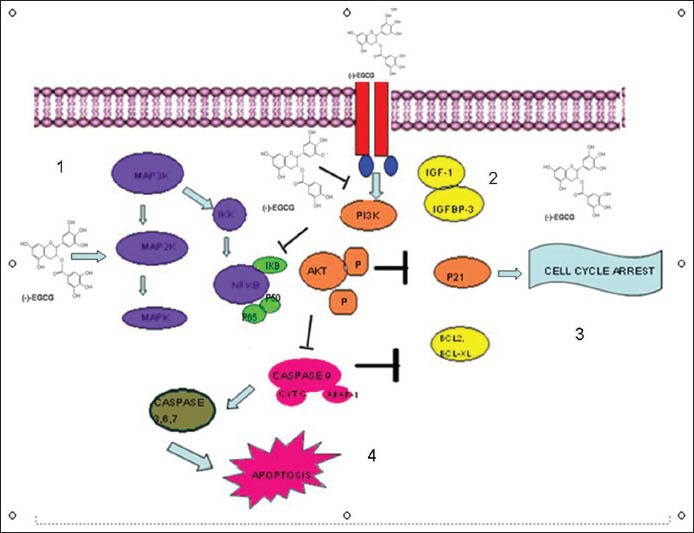

The EGCG and other polyphenols have clearly shown effects on tumor signaling pathways [Figure 1]. Studies have shown EGCG binding to a number of proteins like laminin, vimentin, Fas, and insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor. It also has indirect effects on epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFR), signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs), and activator protein-1 (AP1). EGCG is also a potent inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) pathways.[15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]

Figure 1.

Molecular pathways altered by green tea extract. 1 = Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) modulates the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway bringing about growth inhibition. 2 = EGCG inhibits the insulin growth factor (IGF)-stimulated phosporylation of its receptor. 3 = Cell cycle arrest by EGCG. 4 = Promotion of apoptosis by inhibition of bcl2 and bcl-xl

Green tea polyphenols can induce cell cycle arrest or apoptosis by activating p53 and its targets p21 and Bax.[24] Studies show that EGCG induces apoptosis by activating p73 dependent expression of a subset of p53 target genes including p21, cyclin G1, mouse double minute (MDM) 2, WIG1, and PIG1. The target genes that are negatively regulated by EGCG include Bcl2, Bcl-xl, cyclin D1, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). VEGF has been identified as a promising target for chemoprevention. Previous studies show that green tea polyphenols can inhibit the angiogenesis of breast cancer cells by inhibiting the expression of VEGF and MMP9 through STAT3.[25,26]

Evidences show that EGCG treatment inhibits phosphorylation of EGFR tyrosine kinase in head and neck cancer.[27] EGCG induces internalization and ubiquitin mediated degradation of EGFR ultimately undermining EGFR signaling. EGCG has been extensively studied for its chemopreventive and therapeutic potential.[28] Several studies have shown EGCG mediated inhibition of receptor tyrosine kinases such as HER2, HER3, insulin like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R), and VEGFR and their downstream effectors such as pAKT and pERK.[29,30,31,32] Laminin receptor is identified as a potential receptor for EGCG to modulate several important intracellular signaling pathways.[33,34]

CHEMOPREVENTION CLINICAL TRIALS IN ORAL CANCER

Previously oral cancer chemoprevention clinical trials have utilized local delivery strategies with several classes of compounds such as vitamin A derivatives, adenoviruses, cancer chemotherapy agents, cyclooxygenase (COX) 2 inhibitors, and natural products. The pioneering study using retinoids by Sporn et al.[1] showed chemoprevention in the mainstream cancer research. Landmark studies showed that high dose 13-cis-retinoic acid (13cRA) treatment could reduce the size of precancerous lesions in 67% of patients compared to 10% of the placebo group. This vitamin A derivate was shown to reverse dysplasia.[35] Evidences show a follow-up phase III trial of high dose 13cRA induction followed by low dose cRA being superior to β-carotene in maintenance of the premalignant lesions.[36] Another phase III trial using high dose 13cRA showed significant reduction in the incidence of primary tumors after 1-year treatment period and lasting for a total of 3 years.[37] A combination of high dose 13cRA, α-interferon, and vitamin E has been shown to be effective in delaying head and neck associated with second primary tumors and recurrence.[38] High dose 13cRA has been found active against oral premalignant lesions but has been found too toxic for long-term administration. A number of single agent with low 13cRA trials that followed had negative results.[39,40,41] Subsequent efforts to extend early high dose promise and reduce toxicity by lowering the dosage, failed to reduce the incidence of head and neck cancers. Evaluation of the topical fenretinide application in patients with oral leukoplakia/lichen planus (100 mg BID for 2 months) showed regression of premalignant leukoplakia with no adverse side effects and minimal drug levels in the serum.

CHEMOPREVENTION CLINICAL TRIALS IN ORAL CANCER: GREEN TEA EXPERIENCE

The first clinical trial using green tea for oral premalignant lesions was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial in patients with oral leukoplakia having 760 mg of mixed tea capsules along with mixed tea ointment topically vs placebo with topical glycerin. The treatment groups showed 37.9% response rate after 6 months vs the control arm. These findings correlated with low EGFR positive cells in the treatment group.[42] To evaluate the maximum tolerated dose of green tea, the phase I trial showed dosage of total catechins = 26.9, EGCG = 13.2, EGC = 8.3, ECG = 3.3, EC = 2.2, and caffeine contents = 6.8 with a green tea extract (GTE) dose of either once or thrice for 4 weeks up to a maximum of 6 months being ideal. The dose limiting toxicities reported were tremors, cough, constipation, and headache; attributed to the caffeine components of GTE. Oral GTE dose of 1 gm/m2 thrice daily for at least 6 months was recommended. This study showed that applying tea extracts directly to the lesions may help in improving the local concentrations of the active constituents. The pathological results showed significant decrease in the number and total volume of the silver-stained nucleolar organizer regions and the proliferation cell nuclear antigen in oral mucosa of the treated group compared to the control group.[43]

Another study showed promising results assigning patients with high risk oral premalignant lesions randomly to receive 3 doses of GTE (500, 750, 100 mg/m2) vs placebo thrice a day for 12 weeks and evaluated the biomarkers in the baseline and 12-week biopsied tissues. This study showed a greater clinical response with the 750 and 1000 mg/m2 GTE (58.5%) and 500 mg/m2 (36.4%) vs the placebo arm (18.2%) suggesting a good dose-response effect of GTE in the oral premalignant lesions. An important biomarker inference from this data showed decreasing VEGF expression consistent with previous study.[26,27] This study showed downregulation of stromal VEGF and cyclin D1 in lesions of clinically responsive patients (GTE patients) and upregulated in nonresponsive patients. This study showed GTE suppressing oral premalignant lesions by blocking angiogenesis stimuli. This study not only supported the use of GTE in chemoprevention of oral premalignant lesions but also use of relevant biomarkers in clinical trials to monitor the response.

The only way to ascertain the mechanism of action of the chemopreventive agent at the molecular level towards a response and resistance is by using relevant biomarkers. A natural compound like green tea is well-tolerated and highly consumed and is known to be nontoxic and would not require a Phase I trial that evaluates the dose limiting toxicity and determination of maximum tolerated dose endpoints. Molecular markers can help in determining the biological activity in a chemopreventive setting effectively.

Green tea has also been used along with curcumin, another popular natural compound. Previous studies have shown synergistic growth inhibitory effects with curcumin in head and neck cancer cell lines.[44] Topical curcumin and oral intake of GTE have shown superior antitumor effects in 7,12, dimethylbenzanthracene-induced cancers in vivo.[45] Among the many natural compounds, green tea polyphenols and in particular, EGCG has shown remarkable potential as a chemopreventive agent. The results from the completed studies support a potential role of green tea for oral cancer prevention.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

It is proved by research for more than a decade that green tea polyphenols influences a number of pathways that are relevant to tumor growth proliferation and metastasis. The need of the hour for chemoprevention using green tea is development and validation of biomarkers that can be evaluated by clinical trials in a clinical setting. Moreover, if these biomarkers specifically target different stages of carcinogenesis like initiation, promotion, or metastasized; they will be more useful.

Oral cancer has been shown to be very suitable for chemoprevention trials because of the precancers being readily accessible for clinical and histopathological examination. Oral tumors, due to the process of field cancerization are more prone to second primary tumors and therefore, have a good endpoint in clinical trials. Polyphenols modulate some critical targets including p53, p21, p27, p16, p18, cyclin D1, and cyclin E along with cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 2, CDK4, CDK6, COX-2, MDM2, IGF-I, IGF binding protein (IGFBP3), and NF-κB. Green tea can therefore be evaluated as a monotherapy given for a longer period of time or in combination with targeted agents. The synergism that has been reported earlier may be helpful in a clinical setting including an oral cancer screening program.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sporn MB, Dunlop NM, Newton DL, Smith JM. Prevention of chemical carcinogenesis by vitamin A and its synthetic analogues (retinoids) Fed Proc. 1976;35:1332–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajamanickam S, Agarwal R. Natural products and colon cancer: Current status and future prospects. Drug Dev Res. 2008;69:460–71. doi: 10.1002/ddr.20276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manson MM, Farmer PB, Gescher A, Steward WP. Innovative agents in cancer prevention. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2005;166:257–75. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26980-0_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ko YC, Huang YL, Lee CH, Chen MJ, Lin LM, Tsai CC. Betel quid chewing, cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption related to oral cancer in Taiwan. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;24:450–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1995.tb01132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graham HN. Green tea composition, consumption and polyphenol chemistry. Prev Med. 1992;21:334–50. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(92)90041-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mukhtar H, Ahmad N. Tea polyphenols: Prevention of cancer and optimizing health. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(6 Suppl):1698–702S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.6.1698S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Middleton E, Jr, Kandaswami C, Theoharides TC. The effects of plant flavonoids on mammalian cells: Implications for inflammation, heart disease, and cancer. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:673–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu BT, Hung PF, Chen HC, Huang RN, Chang HH, Kao YH. The apoptotic effect of green tea (-)-epigallocatechin gallate on 3T3-L1 preadipocytes depends on the Cdk2 pathway. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:5695–701. doi: 10.1021/jf050045p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imai K, Suga K, Nakachi K. Cancer preventive effects of drinking tea among a Japanese population. Prev Med. 1997;26:769–75. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1997.0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jankun J, Selman SH, Swiercz R, Skrzypczak-Jankun E. Why drinking green tea could prevent cancer. Nature. 1997;387:561. doi: 10.1038/42381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liao S, Hiipakka RA. Selective inhibition of steroid 5 alpha-reductase isozymes by tea epicatechin-3-gallate and epigallocatechin-3-gallate. Biochem Biophy Res Commun. 1995;214:833–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suganuma M, Okabe S, Sueoka N, Sueoka E, Matsuyama S, Imai K, et al. Green tea and cancer chemoprevention. Mutat Res. 1999;428:339–44. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(99)00059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin AM, Chyi BY, Wu LY, Hwang LS, Ho LT. The antioxidative property of green tea against iron-induced oxidative stress in rat brain. Chin J Physiol. 1998;41:189–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cao Y, Cao R, Bråkenhielm E. Antiangiogenic mechanisms of diet-derived polyphenols. J Nutr Biochem. 2002;13:380–90. doi: 10.1016/s0955-2863(02)00204-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sazuka M, Isenmura M, Isemura S. Interaction between the carboxyl-terminal heparin-binding domain of fibronectin and (-)-epigallocatechin gallate. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1998;62:1031–2. doi: 10.1271/bbb.62.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayakawa S, Saeki K, Sazuka M, Suzuki Y, Shoji Y, Ohta T, et al. Apoptosis induction by epigallocatechin gallate involves binding to Fas. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;285:1102–6. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki Y, Isemura M. Inhibitory effect of epigallocatechin gallate on adhesion of murine melanoma cells to laminin. Cancer Lett. 2001;173:15–20. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00685-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ermakova S, Chol BY, Chol HS. The intermediate filament protein vimentin is a new target for epigallocatechin gallate. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16882–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414185200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shim JH, Choi HS, Pugliese A, Lee SY, Chae JI, Choi BY, et al. (-)-Epigallocatechin gallate regulates CD3-mediated T cell mediator signaling in leukemia through the inhibition of ZAP 70 kinase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:28370–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802200200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li M, He Z, Ermakova S, Zheng D, Tang F, Cho YY, et al. Direct Inhibition of insulin like growth factor-I receptor kinase activity by (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate regulates cell transformation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:598–605. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ermakova SP, Kang BS, Choi BY, Choi HS, Schuster TF, Ma WY, et al. -(-)-Epigallocatechin gallate overcomes resistance to etoposide- induced cell death by targeting the molecular chaperone glucose regulated protein 78. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9260–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hastak K, Agarwal MK, Mukhtar H, Agarwal ML. Ablation of either p21 or Bax prevents p53-dependent apoptosis induced by green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate. FASEB J. 2005;19:786–91. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2226fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amin AR, Thakur VS, Paul RK, Feng GS, Qu CK, Mukhtar H, et al. SHP-2 tyrosine phosphatase inhibits p73-dependent apoptosis and expression of a subset of p53 target genes induced by EGCG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5419–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700642104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hastak K, Gupta S, Ahmad N, Agarwal MK, Agarwal ML, Mukhtar H. Role of p53 and NF-kappa B in epigallocatechin-3-gallate induced apoptosis of LNCaP cells. Oncogene. 2003;22:4851–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sartippour MR, Heber D, Ma J, Lu Q, Go VL, Nguyen M. Green tea and its catechins inhibit breast cancer xenografts. Nutr Cancer. 2001;40:149–56. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC402_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leong H, Mathur PS, Greene GL. Green tea catechins inhibits angiogenesis through suppression of STAT3 activation. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;117:505–15. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0196-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masuda M, Suzui M, Lim JT, Deguchi A, Soh JW, Weinstein IB. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate decreases VEGF production in head and neck and breast carcinoma cells by inhibiting EGFR-related pathways of signal transduction. J Exp Ther Oncol. 2002;2:350–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1359-4117.2002.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang GY, Liao J, Li C, Chung J, Yurkow EJ, Ho CT, et al. Effect of black and green tea polyphenols on c-jun phosphorylation and H (2) O (2) production in transformed and non transformed human bronchial cell lines: Possible mechanisms of cell growth inhibition and apoptosis induction. Carcinogenesis. 21:2035–9. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.11.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang XD, Zhao XY, Zhang M, Liang Y, Xu XH, D’Arcy C, et al. A case-control study on green tea consumption and risk of adult leukemia. Zhonguhua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2008;29:290–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masuda M, Suzui M, Lim JT, Weinstein IB. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits activation of HER2/neu and downstream signaling pathways in human head and neck and breast carcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:3486–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sah JF, Balasubramanian S, Eckert RL, Rorke EA. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits epidermal gowth factor receptor signaling pathway. Evidence of direct inhibition of ERK1/2 and AKT kinases. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12755–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312333200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Syed DN, Afaq F, Kweon MH, Hadi N, Bhatia N, Spiegelman VS, et al. Green tea polyphenol EGCG suppresses cigarette smoke condensate-induced NF-kappaB activation in normal human bronchial epithelial cells. Oncogene. 2007;26:673–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tachibana H, Koga K, Fujimura Y, Yamada K. A receptor for green tea polyphenol EGCG. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:380–1. doi: 10.1038/nsmb743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Umeda D, Yano S, Yamada K, Tachibana H. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate signalling pathway through 67-kDa laminin receptor. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:3050–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707892200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong WK, Endicott LM, Itri LM, Doos W, Batasakis JG, Bell R, et al. 13-cis-retinoic acid in the treatment of oral leukoplakia. N Eng J Med. 1986;315:1501–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198612113152401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lippman SM, Batsakis JG, Toth BB, Weber RS, Lee JJ, Martin JW, et al. Comparison of low-dose isotretoin with beta carotene to prevent oral carcinogenesis. N Eng J Med. 1993;328:15–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301073280103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hong WK, Lippman LM, Itri LM, Karp DD, Lee JS, Byers RM, et al. Prevention of second and primary tumors with isotretinion in squamous-cell carcinoma of head and neck. N Eng J Med. 1990;323:795–801. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199009203231205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shin DM, Khuri FR, Murphy B, Garden AS, Clayman G, Francisco M, et al. Combined interferon-alfa, 13-cis-retinoic acid, and alpha-tocopherol in locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: Novel bioadjuvant phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3010–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.12.3010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pipadimitrakopoulou VA, Hong WK, Lee JS, Batsaki JG, Lippman SM. Low-dose isotretinion versus beta-carotene to prevent oral carcinogenesis: Long-term follow-up. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:257–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lippman SM, Spitz MR. Lung cancer chemoprevention: An integrated approach. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(18 Suppl):74–82S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khuri FR, Lee JJ, Lippman SM, Kim ES, Cooper JS, Benner SE, et al. Randomised Phase III trial of low-dose isotretinoin for prevention of second primary tumors in stage I and Stage II head and neck cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:441–50. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li N, Han C, Chen J. Tea preparations protect against DMBA-induced oral carcinogenesis in hamsters. Nutr Cancer. 1999;35:73–9. doi: 10.1207/S1532791473-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsao AS, Liu D, Martin J, Tang XM, Lee JJ, El-Naggar AK, et al. Phase II randomized, placebo-controlled trial of green tea extract in patients with high-risk oral premalignant lesions. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2009;2:931–41. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khafif A, Schantz SP, al-Rawi M, Edelstein D, Sacks PG. Green tea regulates cell cycle progression in oral leukoplakia. Head Neck. 1998;20:528–34. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199809)20:6<528::aid-hed7>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li N, Chen X, Han C, Chen J. Chemopreventive effect of tea and curcumin on DMBA-induced oral carcinogenesis in hamsters. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu. 2002;31:354–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]