Abstract

Background:

Maxillofacial injuries pose a therapeutic challenge to trauma, maxillofacial and plastic surgeons practicing in developing countries. This was a retrospective study carried out to determine the incidence, etiology, injury characteristics of maxillofacial injuries reported at our centre.

Patients and Methods:

The data for this study were obtained from the medical records of 689 cases reported to our centre during the period from 2006-2009. Records of patients who were either treated in the emergency room as outpatients or the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery as inpatients were analyzed and were subjected to statistical analysis using statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) for Windows version 17.0. Data was summarized in form of proportions and frequency tables for categorical variables and was subjected to Chi-Square test.

Results:

Out of 689 patients, 75.9% were male and 24.1% were female. 42.5% of the patients were in the age group of 21 to 30 years. Road traffic accidents accounted for the majority (74.3%) of cases of maxillofacial trauma. Mandible was seen as the most commonly fractured bone (50.3%) and 53.8% head and neck injuries were most common among the associated injuries.

Conclusion:

Road traffic accidents were clearly the most prevalent etiological factor for maxillofacial trauma. Measures on prevention of road traffic crashes should be strongly emphasized in order to reduce the occurrence of these injuries.

Keywords: Bangalore, injury characteristics, maxillofacial trauma etiology

INTRODUCTION

The maxillofacial region occupies the most prominent position in the human body and rendering it vulnerable to injuries quite commonly.[1] It is estimated that more than 50% of patients with these injuries have multiple trauma requiring coordinated management between emergency physicians and surgical specialists in otolaryngology, trauma surgery, plastic surgery, ophthalmology, and oral and maxillofacial surgery.[2,3] Maxillofacial injuries can occur as an isolated injury or may be associated with multiple injuries to the head, chest, abdominal, spinal and extremities.[4] The causes of maxillofacial trauma vary and include road traffic accidents (RTAs), interpersonal violence, falls, sports and missile injuries.[5] The relative contribution of each cause depends on such factors as geoFigureical location, socio-economic factors and the seasons of the year.[6] With regard to the anatomical sites, mandibular and zygomatic complex fractures account for the majority of all facial fractures and their occurrence varies according to the mechanism of injury and demoFigureic factors, particularly, gender and age.[6] The causes of maxillofacial injuries have changed over the past three to four decades and continue to do so. The main causes worldwide are assaults and traffic accidents, but the most frequent cause varies from one country to another. Some studies have shown that assault is most common in developing countries, whereas, traffic accidents are more common in developed countries. The causes and pattern of maxillofacial injuries reflect trauma patterns within the community and, as such, can provide a guide to the design of programmes geared toward prevention and treatment. The coordinated and sequential collection of information concerning demoFigureic patterns of maxillofacial injuries may assist health care providers to record detailed and regular data of facial trauma. Consequently an understanding of the cause, severity, and chronological distribution of maxillofacial trauma permit clinical and research priorities to be established for effective treatment and prevention of these injuries.[7] This study was developed because there is insufficient literary evidence from our region to accurately illustrate, analyze and document the etiologic factors and frequency responsible for maxillofacial trauma.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The data for this study were obtained from the medical records of 689 cases reported to our centre during the period from 2006-2009. Records of patients who were either treated in the emergency room as outpatients or the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery as inpatients were analyzed retrospectively. Age, gender, cause, site and type of injury and associated injuries were recorded.

Information relevant to the study was obtained from the patient directly; when this was not possible, collateral history was obtained from the relatives attending to the patients. All maxillofacial bony injuries were diagnosed by conventional and panoramic radioFigures. When each patient arrived at hospital for evaluation, a trauma form was filled and depending on the fracture pattern the appropriate treatment was given. Data collected were analyzed using the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) for Windows version 17.0. Data was summarized in form of proportions and frequency tables for categorical variables and was subjected to Chi-Square test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

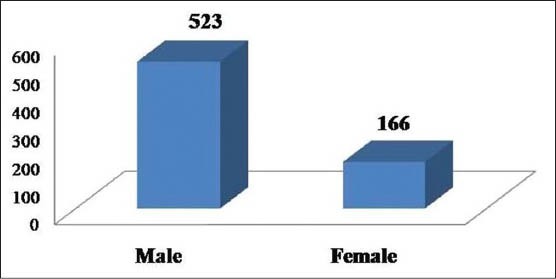

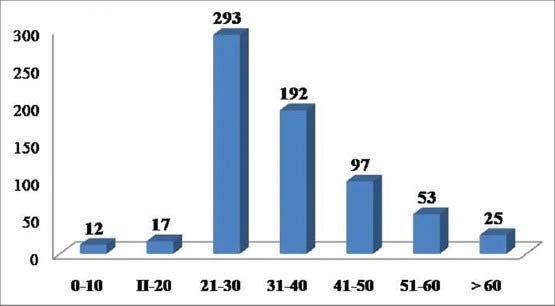

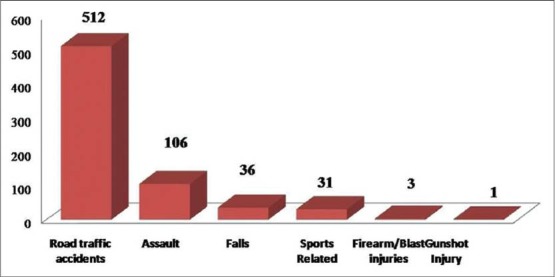

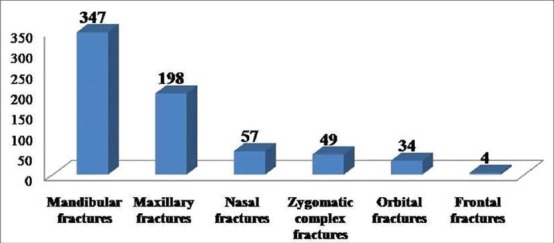

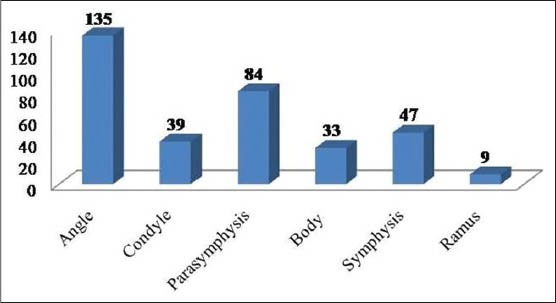

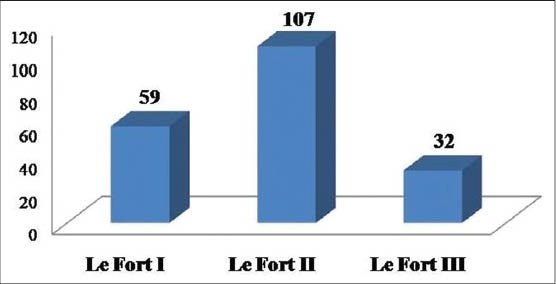

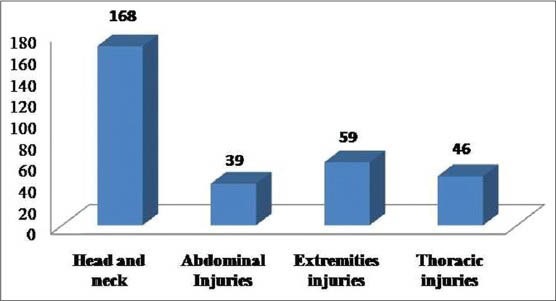

A total of 689 patients were reported at our centre in that 523 (75.9%) were male and 166 (24.1%) were female [Figure 1]. A total of 293 (42.5%) patients in our study fell in to the age group of 21 to 30 years [Figure 2]. Road traffic accidents 512 (74.3%) were seen as the main etiological factor resulting in maxillofacial injuries followed by assaults 106 (15%) and 36 (5.2%) falls [Figure 3]. Among 689 maxillofacial fractures reported mandibular fractures were 347 (50.3%) followed by 198 (28.7%) maxillary, 57 (8.2%) nasal, 49 (7.1%) zygomatic complex, 34 (4.9%) orbital and 4 (0.5%) frontal fractures [Figure 4]. The most common site of fracture in the mandible was angle 135 (38.9%) followed by parasymphysis 84 (24.2%), symphysis 47 (13.5%), condyle 39 (11.2%), body 33 (9.5%) and ramus 9 (2.5%) [Figure 5]. Among the maxillary fractures the most common was Lefort II 107 (54%) followed by Lefort I 59 (29.7%) and Lefort III 32 (16.1%) [Figure 6]. Associated injuries along with maxillofacial fractures were most commonly head and neck injuries 168 (53.8%) followed by extremities 59 (18.9%), thoracic 46 (14.7%) and abdominal 39 (12.5%) [Figure 7].

Figure 1.

Gender wise distribution of maxillofacial injuries. P < 0.001, Statistically Significant, Chi-Square test

Figure 2.

Age wise distribution of maxillofacial injuries. P < 0.001, Statistically Significant, Chi-Square test

Figure 3.

Distribution of patients according to cause of injury. P < 0.001, Statistically Significant, Chi-Square test

Figure 4.

Distribution of maxillofacial fractures. P < 0.001, Statistically Significant, Chi-Square test

Figure 5.

Distribution of mandibular fractures. P < 0.001, Statistically Significant, Chi-Square test

Figure 6.

Distribution of maxillary fractures. P < 0.001, Statistically Significant, Chi-Square test

Figure 7.

Distribution of associated injuries. P < 0.001, Statistically Significant, Chi-Square test

DISCUSSION

The etiological factors and pattern of maxillofacial injuries have been reported to vary from one geoFigureical area to another depending upon the socioeconomic status, geoFigureic condition and cultural characteristics.[6,7] The male predominance in our study agrees with what is reported in literature.[7,8] Males are at greater risk due to their greater participation in high risk activities which increases their exposure to risk factors such as driving vehicles, sports that involve physical contact, an active social life and drug use, including alcohol.

In agreement with other studies,[2,7,8,9] the majorities of patients in the present study were young adult in their third decade (21-30 years). However, this observation in contrast to some studies, where the dominant age groups having a high incidence were 0-10 years and 11-20 years respectively.[10,11,12] The possible reasons for the higher frequency of maxillofacial injuries in third decade may be attributed to the fact that people in this period of life are more active regarding sports, fights, violent activities, industry and high speed transportation. The low frequencies in the very young and old age groups are due to the low activities of these age groups.[13,14,15]

Maxillofacial injuries are commonly caused by road traffic accidents, assaults, sports, fire arm/blast injuries and gunshot injuries. In this study road traffic accidents were the most common cause of trauma, comprising 74.3% of the etiology of injuries and also considering the fact that Bangalore is the third most populated city in India. This figure was 40% in one study from the United States, 24.7% from England, 48% in a study from France, 55.2% in a study from Jordan12 and 44% in a study from Pakistan.[16,17] The high number of maxillofacial injuries attributed to RTA in our study is attributed to recklessness and negligence of the driver, often driving under the influence of alcohol or drugs and complete disregard of traffic laws, over speeding, overloading, underage driving and poor conditions of roads and vehicles. Excessive consumption of alcohol is strongly associated with facial injuries.[10,16] Alcohol impairs judgment, brings out aggression, often leads to interpersonal violence, and is also a major factor in motor vehicle accident. In the present study, alcohol consumption prior to the injury was recorded in 41.6% of cases which is comparable to other studies.[16] Al Ahmed et al.,[17] in a review of 230 cases of maxillofacial injuries in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates reported no cases were associated with alcohol abuse. This discrepancy may be explained by differences between one country and another, in the strictness of laws governing the sale and consumption of alcohol which may be effective in preventing alcohol-related injuries.

Head injury (53.8%) accounted for the greater majority of associated injuries and contributed significantly to missed maxillofacial injuries, similar to findings from other studies.[18,19] The incidence of missed injuries has been reported to be higher in patients with associated severe head injuries. This is reflected in the high rate of missed maxillofacial injuries in our patients, the majority of them had associated severe head injuries. This finding calls for high index of suspicious when dealing with these patients.

Mandible was seen as the most commonly fractured bone in our study accounting for 50.3% of the fractures and the most common site was 38.9%. This finding is consistent in a similar study from Bulgaria whereas the percentage of mandibular fracture in a study from Pakistan and UAE was 51%. Among the maxillary fractures the most common was Lefort II 54%, similar to findings from other studies.[18,19,20] The studies by Al Khateeb et al. have found zygomatic complex as the most common site of midface injury which is not coinciding with the results of this study.[21] Klenk et al. reported in their study that when considering midface fractures, ZMC fractures predominate followed by Le Fort and dentoalveolar fractures respectively. Fractures such as NOE and isolated blowout fractures only accounted for less than 7% of the fractures. Other authors have also reported that a ZMC fracture has the highest incidence although there is variability in the frequency of the other midfacial bones. One reason for the high rate in the ZMC fractures is that it is instinctive to turn the head when anticipating a blow to the midface in order to protect the globe.[22] The involvement of nasal bone in most of the midface fractures may be attributed to its predominant location on the face and relative structural weakness as was reported in the studies of Le et al.

CONCLUSION

Road traffic accidents (RTA) were the major etiological factor of maxillofacial injuries in our centre and the young adult males were the main victims. Better road safety laws need to be evolved but more importantly enforced. Public should be made aware of road safety legislations and the subsequent repercussions of failure in compliance.

Future studies should seek to understand the epidemiological factors influencing facial trauma in an effort to improve prevention and management of these injuries. In addition it is clear that trends are observed when analysing the data collated, however the limited numbers of patients do not reflect statistical significance. Again, further research is required to encompass a larger sample size with adequate follow-up of clinical outcomes as to obtain more meaningful data with other criteria such as complication rates, sepsis rates and total hospitalization costs being incorporated. This would enhance a better understanding of influencing patterns on facial trauma.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Dr. Mahesh Hiregoudar, Assistant Professor, Department of Community Dentistry, AME's Dental College Hospital and Research Centre, Raichur for his guidance in analysing the statistical data in this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Balakrishnan N, Paul G. Incidence and aetiology of fracture of the faciomaxillary skeleton in Trivanadrum: A retrospective study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;24:40–3. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(86)90038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalya PL, McHembe M, Mabula JB, Kanumba ES, Gilyoma JM. Etiological spectrum, injury characteristics and treatment outcome of maxillofacial injuries in a Tanzanian teaching hospital. J Trauma Manag Outcomes. 2011;5:7. doi: 10.1186/1752-2897-5-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Down KE, Boot DA, Gorman DF. Maxillofacial and associated injuries in severely traumatized patients: Implications of a regional survey. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;24:409–12. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(05)80469-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Motamedi MH. An assessment of maxillofacial fractures: A 5-year study of 237 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:61–4. doi: 10.1053/joms.2003.50049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akama MK, Chindia ML, Macigo FG, Ghuthua SW. Pattern of maxillofacial and associated injuries in Road traffic accidents. East Afr Med J. 2007;84:287–90. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v84i6.9539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah A, Shah AA, Salam A. Maxillofacial fractures: Analysis of demoFigureic distribution in Ugandan tertiary hospital: A six-month prospective study. Clinics. 2009;64:843–8. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322009000900004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandra Shekar BR, Reddy C. A five-year retrospective statistical analysis of maxillofacial injuries in patients admitted and treated at two hospitals of Mysore city. Indian J Dent Res. 2008;19:304–8. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.44532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee KH, Snape L, Steenberg LJ, Worthington J. Comparison between interpersonal violence and motor vehicle accidents in the aetiology of maxillofacial fractures. ANZ J Surg. 2007;77:695–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2007.04189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Telfer MR, Jones GM, Shepherd JP. Trends in the aetiology of maxillofacial fractures in the United Kingdom (1977-1987) Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;29:250–5. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(91)90192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Umar KB, Shuja RA, Ahmad K, Mohammad TK, Abdus S. Occurrence and Characteristics of Maxillofacial Injuries-A Study. Pakistan Oral Dent J. 2010;30:57–61. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qudah MA, Al-Khateeb T, Bataineh AB, Rawashdeh M. Mandibular fractures in Jordanians: A comparative study between young and adult patients. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2005;33:103–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al Ahmed HE, Jaber MA, Abu Fana SH, Karas M. The pattern of maxillofacial fractures in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates: A review of 230 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;98:166–70. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wimon S, Kasemsak P. The Epidemiology of Mandibular Fractures Treated at Chiang Mai University Hospital: A Review of 198 Cases. J Med Assoc Thai. 2008;91:868–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banks P. 4th ed. Bombay: Varghese Publishing House; 1993. Killey's fractures of the mandible; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kontio R, Suuronen R, Ponkkonen H, Lindqvist C, Laine P. Have the causes of maxillofacial fractures changed over the last 16 years in Finland? An epidemiological study of 725 fractures. Dent Traumatol. 2005;21:14–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2004.00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Khateeb T, Abdullah FM. Cranio maxillofacial injuries in the United Arab Emirates: A retrospective study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:1094–101. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Subhashraj K, Nandakumar N, Ravindran C. Review of maxillofacial injuries in Chennai, India: A study of 2748 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;45:637–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wasiu LA, Akinola LL, Mobolanle OO, Olutayo J. Trends and characteristics of oral and maxillofacial injuries in Nigeria: A review of the literature. Head Face Med. 2005;1:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leles JL, Santos ÊJ, Jorge FD, Silva ET, Leles CR. Risk factors for maxillofacial injuries in a Brazilian emergency hospital sample. J Appl Oral Sci. 2010;18:23–9. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572010000100006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al Khateeb T, Abdullah FM. Cranio maxillofacial injuries in the United Arab Emirates: A retrospective study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:1094–101. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klenk G, Kovacs A. Etiology and patterns of facial fractures in the United Arab Emirates. J Craniofac Surg. 2003;14:78–84. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200301000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Le BT, Dierks EJ, Brett A. Maxillofacial injuries associated with domestic violence in Portland. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:1277–83. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.27490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]