Abstract

The increasing demand for organ donors to supply the increasing number of patients on kidney waiting lists has led to most transplant centers developing protocols that allow safe utilization from donors with special clinical situations which previously were regarded as contraindications. Deceased donors with previous hepatitis C infection may represent a safe resource to expand the donor pool. When allocated to serology-matched recipients, kidney transplantation from donors with hepatitis C may result in an excellent short-term outcome and a significant reduction of time on the waiting list. Special care must be dedicated to the pre-transplant evaluation of potential candidates, particularly with regard to liver functionality and evidence of liver histological damage, such as cirrhosis, that could be a contraindication to transplantation. Pre-transplant antiviral therapy could be useful to reduce the viral load and to improve the long-term results, which may be affected by the progression of liver disease in the recipients. An accurate selection of both donor and recipient is mandatory to achieve a satisfactory long-term outcome.

Keywords: Kidney transplantation, Deceased donor, Hepatitis C virus, De novo glomerulonephritis, Liver failure, Graft survival, End-stage renal disease, Hemodialysis

INTRODUCTION

The increasing demand for available organ donors for kidney transplantation has led many transplant centers to expand their acceptance criteria by including deceased donors with special clinical situations, such as potentially transmittable infections.

Kidney transplantation is nowadays considered the best replacement therapy for patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD); therefore, there is a clear need to expand the current donor pool. One strategy focuses on the use of donor kidneys with viral hepatitis, and several organ procurement associations have adopted the policy of accepting kidneys from deceased donors with hepatitis C infection.

Defining the natural history of hepatitis C infection in ESRD patients remains difficult for several reasons: the disease extends for many years, and the onset of the disease is frequently unknown[1]. Moreover, the infection is likely to be asymptomatic with an apparently indolent course. HCV infection has been estimated to occur in 7.8%-9.2% of the ESRD population, and fortunately its incidence is slowly declining all over the world[2-5]. ESRD patients have a relative risk of death between 1.41 and 1.78[5-8], and a recent meta-analysis quantified the relative risk of death in ESRD patients with HCV infection as 1.57[9]. The natural history of HCV infection in renal transplant recipients is not well known[10]: most transplant centers do not perform a liver biopsy before transplant and in addition, compared to those with normal renal function, ESRD patients with HCV have lower serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and albumin levels, lower viral loads (usually < 1 million copies/mL), and less hepatic steatosis[11-26]. Moreover, HCV-positive renal transplant recipients may have higher morbidity and mortality, making long-term consequences difficult to assess[1,26].

The presence of anti-HCV antibodies is an independent and significant risk factor for death and graft failure in renal transplant recipients[11], and many transplant centers have recently reported a lower graft and patient survival in HCV-positive recipients[2-5,8,12-25]. Multicenter surveys[17-19] have confirmed that HCV-seropositivity confers an additional risk for death in renal transplant recipients.

There are several factors that may influence patient survival in HCV-seropositive patients: the progression of liver disease[25-27] (although all studies have not incorporated a liver biopsy in the pre-transplant work-up), the immunosuppressive therapy, the development of new-onset diabetes mellitus after transplantation, and the higher risk of cardiovascular disease[1].

However, the benefit in terms of survival advantage of renal transplantation in patients with HCV infection vs long-term dialysis has been demonstrated in many retrospective studies[23-25,28], and no studies have demonstrated a diminished survival after kidney transplantation, so that kidney transplantation should now be considered the treatment of choice for ESRD patients with HCV infection. HCV infection has a negative impact on the survival of ESRD patients due to the increased risk of cardiovascular events[8,9]. Although some studies have reported a high relative risk of death from liver disease of up to 5.79[8], only a small proportion of deaths were attributable to liver disease (2%-14%)[8,9], probably because most patients die of other clinical conditions before the liver disease can progress to a clinically relevant disease.

While survival is improved in this group of patients compared to HCV-infected patients with ESRD who do not undergo renal transplantation, debate in the literature continues as to the short- and long-term outcomes of patients with chronic HCV infection undergoing renal transplantation compared with ESRD patients without HCV infection who are transplanted. It is known that viral loads increase following renal transplantation (1.8- to 30.3-fold): in a recent retrospective study, Gentil Govantes et al[29] found that patients with active viral replication at the time of kidney transplantation had a significantly increased incidence of liver disease and reduced renal function. Moreover, active viral replication was an independent risk factor for post-transplant mortality and graft failure among HCV-positive recipients.

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus is higher in HCV-infected patients post-transplant, and chronic HCV infection is associated with decreased patient and graft survival when compared with patients who are not infected with HCV[26,27]. Additionally, liver failure has been implicated as the cause of death in 8%-28% of renal transplant recipients in the long term[30], and death from hepatocellular carcinoma and cirrhosis was notably higher among hemodialysed patients who were HCV antibody-positive[9].

While short-term results are similar to those of patients who are not infected with HCV, data about the long-term outcome of HCV-infected kidney transplants showed a lower graft and patient survival among HCV recipients, with liver failure being the primary cause of death in these patients (10%-22%)[31,32].

KIDNEY TRANSPLANTATION FROM DECEASED HCV-POSITIVE DONORS

The widely accepted opinion that HCV infection may be transmitted from donors with HCV infection with a frequency of 100%[33] has yielded the opinion that HCV-positive kidneys should not be transplanted. However, this policy could determine a discard of about 5% of organ donors, aggravating the organ shortage. A recent survey[7] demonstrated that in 93825 deceased donors in the United States between 1995 and 2009, HCV-positive kidneys were 2.60-times more likely to be discarded. Interestingly, only 29% of HCV-positive recipients received HCV-positive kidneys, and more than 50% of HCV-positive kidneys were discarded.

Nowadays, many transplant centers have adopted the policy of accepting kidneys from HCV-positive organ donors for HCV-positive recipients, even if the safety of the use of kidneys from HCV-infected donors has not been fully elucidated[34-36]. Evidence suggests that outcomes of HCV-positive recipients who receive kidneys from HCV-positive donors are slightly worse than outcomes of HCV-positive recipients who receive a kidney from similar HCV-negative donors[7]. However, HCV-positive recipients who received HCV-positive kidneys have a significantly lower waiting time than their HCV-negative counterparts[7], with no adverse effects on short-term patient and graft survival[37-40]. Although some authors have advocated avoiding the use of HCV-positive kidneys in recipients older than 65 years due to the higher risk of infectious complications[3], there is no clear evidence that older age may have an impact on graft survival in patients receiving kidney transplantations from HCV-positive donors[40]. However, up to 20% of patients may have reactivation of the disease after transplantation[40], and the time to reactivation may be shorter in renal transplant recipients of HCV-positive kidneys. The clinical importance of HCV reactivation following kidney transplantation from HCV-positive donors is controversial and, although some studies demonstrated a higher rate of liver disease in recipients of HCV-positive kidneys compared to recipients of HCV-negative recipients, graft survival was not different between the two groups[41-43].

While kidney transplantation confers a significant advantage in terms of patient survival in ESRD patients with HCV infection when compared to maintenance hemodialysis, donor HCV serologic status is independently associated with an increased risk of mortality[44]. Abbott et al[45] evaluated 38270 United States Renal Data System (USRDS) Medicare beneficiaries awaiting kidney transplantation and demonstrated that transplantation from HCV-positive donors is associated with improved survival when compared with patients on the waiting list, although this advantage was not as substantial as transplantation from all deceased donors. However, a recent survey by Kucirka et al[7] showed that kidney transplantation from HCV-positive donors was associated with 1.29-times increase in the risk of death; this was reflected in a difference of only 1% in 1-year survival and 2% in 3-year survival.

In a recent study, Morales et al[43] compared 162 kidney transplant recipients receiving a graft from an HCV-positive donor with 306 receiving a kidney graft from an HCV-negative donor: five- and ten-year patient survival was 84.8% and 72.7%, respectively, in the group of patients receiving a graft from an HCV-positive donor vs 86.6% and 76.5% in recipients of an HCV-negative graft (P = 0.250). Five- and ten-year graft survival was not statistically different between the two groups. Decompensated liver disease rate was also not significantly different between the two groups (10.3% vs 6.2%).

A historical cohort study of 36 956 deceased United States adult donor renal transplant recipients over a 5-year period from 1996 to 2001 demonstrated that receiving an HCV(+) donor kidney was independently associated with increased mortality, primarily as a result of non-HCV infection, presumably due to the theory that acute HCV infection places transplant patients at risk for over-immunosuppression as a direct inhibitory effect of HCV on T-cell function[46].

Recent evidence has suggested that kidney transplantations from HCV-positive donors may have a worse graft outcome when compared with HCV-negative recipients[8,47-49], and eradication of HCV infection before transplantation seems to reduce the risk for HCV-associated renal dysfunction after transplantation and may reduce the risk for HCV disease progression, thereby providing the rationale for treatment of HCV before transplantation.

The issue of transplanting kidneys from HCV-positive organ donors into anti-HCV positive/HCV RNA negative recipients has not been fully addressed: in a retrospective study, Morales et al[50] demonstrated a higher rate of viral reactivation among anti-HCV positive/HCV RNA negative recipients who received a kidney from an anti-HCV positive donor. Based on these findings, many transplant centers adopted the policy of transplanting kidneys from anti-HCV positive donors into HCV RNA positive recipients, restricting the use of HCV-positive donors to recipients with active viremia[1,40]. The use of organs from viremic HCV-positive donors into HCV-RNA negative recipients would have the effect of reintroducing HCV infection, whereas using HCV-positive kidneys in HCV RNA positive recipients can determine a superinfection with a different genotype[1], with many severe clinical consequences.

Ideally, donors and recipients should be matched for HCV genotype to minimize the risk of superinfection, even if this procedure is rarely performed during a deceased donor evaluation.

Organs from HCV-RNA positive donors should be offered only to viremic recipients or even discarded, due to the high rate of viral reactivation after transplantation[40].

However, a large multicenter trial demonstrated that the type of genotype might not have a significant impact on survival among patients with ESRD, since the survival in patients with mixed infection was similar to that of patients with a single HCV infection[51].

PRE-TRANSPLANT EVALUATION AND TREATMENT

All kidney transplant candidates undergo a full evaluation of serologic markers, including anti-HCV serology.

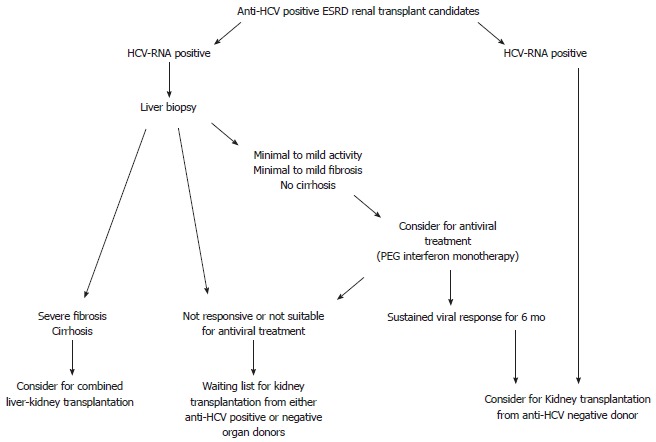

In dialysis patients with chronic HCV infection, serum aminotransferase levels are not reliable in determining disease activity and fibrosis severity, and uremic patients may be more likely than non-uremic patients to have persistently normal serum aminotransferase levels. Therefore, the presence of persistently normal serum aminotransferase levels does not exclude the presence of significant liver disease[52]. While recent observations suggest that liver biopsy is not useful in anti-HCV positive/HCV-RNA negative patients[53], all anti-HCV positive ESRD patients should undergo an HCV-RNA evaluation, and all HCV-RNA positive patients should undergo a liver biopsy (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed algorithm for the evaluation and allocation of renal transplant candidates with hepatitis C virus infection. ESRD: End-stage renal disease; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; PEG: Polyethylene glycol.

The information obtained from liver biopsy is mandatory in the decision making for acceptance of an anti-HCV positive ESRD patient to the waiting list for a kidney transplantation. In fact, biochemical tests are not useful for reflecting the histological severity of liver damage, and liver disease may progress rapidly after transplantation.

Although recent studies suggest that kidney transplantation alone could be feasible even in patients with biopsy-proven cirrhosis with a hepatic portal venous gradient less than 10 mmHg[54], the finding of pre-transplant cirrhosis has been clearly associated with a strong reduction of survival in renal transplant recipients[52,55], and now it is considered a contraindication to kidney transplantation alone. Information about the progression of liver disease after transplantation is lacking: most of the studies have demonstrated the progression of liver disease in kidney transplant recipients, but data on pre-transplant biopsies are not reported.

Cross-sectional studies suggest that about 25% of HCV(+) patients with ESRD have significant fibrosis pre-transplant[1]. Zylberberg et al[56] retrospectively compared the liver histopathology of 28 HCV(+) kidney recipients to that of 28 controls. Over a period of 7 years, hepatic fibrosis worsened in 50% of patients, and 21% developed cirrhosis. In a prospective cohort study by Alric et al[57], serial liver biopsies in 30 renal transplant recipients, performed at 4 and 7 years following renal transplant, demonstrated a progression of liver fibrosis in 30% of the patients. In contrast, Kamar et al[58] demonstrated no progression of liver fibrosis in 50% of patients. The rate of progression among kidney transplant recipients was lower than in HCV-infected patients without ESRD, probably due to immunosuppressant effects that result in less inflammation and subsequent fibrosis in response to HCV infection[56-58]. Recently, in a study evaluating the progression of liver disease in a HCV-positive cohort of kidney transplant recipients, de Oliveira Uehara et al[59] demonstrated a progression of liver fibrosis in 50% of patients and a worsening of necro-inflammatory activity in 32%: progression of liver disease was noted even in patients without significant histological alteration before transplant.

In contrast, Roth et al[60] evaluated the progression of liver disease in 44 HCV-positive kidney transplant recipients, where pre-transplant biopsy was available. Unexpectedly, despite many years of immunosuppression, liver histology remained stable (or even improved) in the majority of re-biopsied kidney transplant recipients: 16% of the liver biopsies obtained after transplant showed histologic improvement when compared with the baseline pre-transplant sample, whereas only 23% showed progression of liver injury.

Kucirka et al[12] analyzed more than 6000 kidney transplantations from the UNOS database and demonstrated that only 29% of HCV-positive deceased donor kidney recipients received a graft from an HCV-positive donor. It was of interest that kidney transplantation from HCV-positive donors could reduce by more than one year the waiting time for HCV patients, but those who received a kidney from an HCV-positive donor had a 2.6-fold higher risk of joining the liver transplantation list.

Since most studies[61-66] demonstrated a rate of 20%-100% of acute rejection in HCV-positive kidney transplant recipients treated with interferon alfa, post-transplant treatment is now contraindicated, and the only therapeutic management of HCV infection in ESRD patients listed for kidney transplantation remains pre-transplant treatment, whenever possible. Optimal management of HCV infection should occur prior to the development of ESRD, when both interferon and ribavirin can be used to maximize viral response. However, for those patients who are not diagnosed until after they have reached ESRD or who contract HCV after ESRD develops, treatment options are more limited given the relative contraindication to ribavirin in the setting of renal failure and the need for close monitoring for hemolysis and anemia in the event of ribavirin use[67]. In addition, ESRD patients have a lower tolerability to interferon, and two meta-analyses showed a 17%-30% dropout rate in this patient population vs a standard non-ESRD dropout rate of about 3%-10%[68].

Many small studies have demonstrated the efficacy of interferon monotherapy in the treatment of HCV infection in ESRD patients. Two recent meta-analyses assessing the efficacy of interferon monotherapy have shown sustained viral response (SVR, defined by an undetectable HCV RNA < 50 IU/mL in serum at least 6 mo after stopping treatment) rates of 33%-37%[68] and this SVR appears to continue post-transplant, minimizing the effect of post-transplant HCV glomerulonephritis.

The combination of ribavirin and interferon is problematic in ESRD patients, due to the low clearance of ribavirin by dialysis, exacerbating the risk of hemolysis in patients already at higher risk of anemia. Some small studies demonstrated a SVR of 66% in ESRD patients[64], but the risk/benefit ratio related to adding ribavirin was not established. Given the difficulty with hemolysis when using ribavirin in ESRD, extreme caution with close monitoring of ribavirin levels is recommended[3].

At this time, there are data, albeit limited, supporting the safety of pegylated interferon as monotherapy for the treatment of hepatitis C in patients with ESRD. Gupta et al[69] showed that less than 50% of pegylated interferon alfa-2b is renally cleared and that hemodialysis did not appear to affect its clearance. Unfortunately, there are little data on tolerability, with a wide range of withdrawal rates in the three studies performed above: from 0% to 73%[3]. However, Werner et al[70] recently reported a 45% SVR among 22 HCV-positive ESRD patients treated with PEG-IFN monotherapy.

In patients with normal renal function, similar enhancements in SVR rates are seen when pegylated interferon is combined with ribavirin. Based on this finding, the most promising recent development in the treatment of chronic HCV-infected patients with ESRD is the use of pegylated interferon combined with low-dose ribavirin, despite the known risks with ribavirin use in patients with chronic renal failure.

Rendina et al[71] completed a randomized, controlled trial involving 35 patients treated with 135 μg/wk of pegylated interferon alpha-2a and low-dose ribavirin 200 mg daily every other day for 48 wk. The study showed a 97% SVR rate despite an early withdrawal rate of 15%, with only 6% withdrawal due to lack of tolerability and no adverse events reported.

Summarizing, recent evidence suggests that the standard of care for treatment of HCV-positive ESRD patients is interferon monotherapy. Whether pegylated IFN offers advantages over non-pegylated IFN is unknown[71,72]. The treatment duration with IFN monotherapy is typically 48 wk[71,72], but non-responders may be identified even after 3-6 mo of treatment. Genotypes 1, 4, 5 and 6 are more resistant to IFN therapy and need a longer course of treatment[73]. Patients who fail to achieve HCV RNA of < 50 IU/mL after 6 mo of treatment should be considered as non-responsive and generally should have treatment discontinued.

POST-TRANSPLANT TREATMENT AND HCV GLOMERULONEPHRITIS

Treatment of HCV in kidney transplant recipients is not routinely recommended[74,75] because of concerns about IFN precipitating acute rejection. However, there are clinical circumstances in which a risk/benefit assessment may favor treatment.

In the study by Aljumah et al[55], 19 HCV-positive kidney transplant recipients received treatment with a combination of pegylated interferon and ribavirin for 48 wk, with an SVR in 42.1% of patients. Only one patient developed a borderline acute rejection.

HCV-associated glomerulonephritis can recur after kidney transplantation and cause progressive renal dysfunction, and antiviral therapy may be needed to prevent graft loss; moreover, patients with advanced fibrosis or severe cholestatic hepatitis warrant consideration of treatment to prevent death as a result of liver-related complications. Some data suggest that these transplant recipients will benefit from treatment with IFN monotherapy or IFN plus ribavirin combination therapy[73-77].

Kidney injury in HCV-positive patients may be mediated through immunological and non-immunological mechanisms. HCV-RNA and related proteins have been found in mesangial cells, tubular epithelial cells and endothelial cells of glomerular and tubular capillaries, and this has been associated with higher proteinuria, possibly reflecting direct mesangial injury by HCV infection[77,78].

Kidney injury may be mediated by a systemic immune response to HCV infection, which is mediated by cryoglobulins, HCV-antibody immune complexes or amyloid deposition[79]. Persistence of HCV leads to chronic overstimulation of B-lymphocytes and production of mixed cryoglobulins that are deposited in the mesangium and glomerular capillaries[79]. This is usually associated with histologic signs of vasculitis and downstream fibrinoid necrosis of the glomeruli.

Non-immunologically mediated kidney injury may be related to high levels of fasting serum insulin and insulin resistance, which promote proliferation of renal cells[80].

This histological kidney injury represents HCV-related glomerulonephritis, which may develop many years after initial infection with HCV[72]. The most common HCV-related nephropathy is membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN), usually in the context of cryoglobulinemia. Most patients have no clear symptoms, but the triad of purpura, asthenia and arthralgia is evident in 30% of cases[81]. Renal involvement is reported in one third of patients with cryoglobulinemia[82]. Glomerular disease may manifest acutely in 5% of cases and the majority of patients develop hypertension: renal biopsy shows a pattern of MPGN[82], and the diagnosis of HCV-related MPGN is made by a positive test for serum HCV antibodies and HCV RNA.

The long-term outcome of HCV-related nephropathies is still not clearly defined; however, HCV-positive patients were found to have a 40% higher likelihood for developing renal insufficiency compared with seronegative patients[83].

Hypertension, proteinuria and progressive renal failure are the main clinical manifestations of HCV-associated chronic kidney disease. Thus, renoprotection with either angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers must be applied[73]. Antiviral therapy should be attempted in hemodialysed patients[73]. In kidney transplant recipients with de novo glomerulonephritis with low proteinuria and stable renal function, initiation of antiviral therapy should be based on the degree of liver damage. For patients with severe de novo glomerulonephritis and high risk of chronic graft failure, antiviral therapy (IFN alone or in combination with ribavirin) should be initiated as soon as possible[73].

Immunosuppressive treatment should be adapted to prevent rejection while minimizing viral replication. Experimental studies[84] have shown that cyclosporine may inhibit the intracellular replication of HCV, independently of its immunosuppressive activity. However, in the clinical setting this antiviral effect of cyclosporine remains controversial[50,85].

Findings of the USRDS registry reported a better graft survival in recipients treated with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) than in those on other immunosuppressive therapy[50]. However, a prospective study reported an increase in viral replication in patients on MMF therapy[86], suggesting that the immunosuppressive therapy should be adapted to patients’ clinical conditions.

FUTURE CHALLENGES

Kidney transplantation is the best replacement therapy for HCV-positive ESRD patients, as it confers a survival advantage when compared to dialysis. Kidney transplantation from HCV-positive donors into HCV-positive recipients may be useful to expand the donor pool, by increasing the rate of utilization of these kidneys. While short-term results are conflicting, kidney transplantations from HCV-positive donors permit a reduction in waiting time for kidney transplantation with long-term graft and patient survival similar to HCV-positive recipients receiving a kidney from an HCV-negative donor. However, de novo HCV-related glomerulonephritis and the higher risk of chronic humoral rejection may hamper the graft survival in these patients. Future studies should address the optimal immunosuppressive therapy aiming to reduce the risk of liver disease progression and the risk of cardiovascular complications, such as new-onset diabetes mellitus after transplantation, which may be increased in HCV-positive kidney transplant recipients.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Bahri O S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: Logan S E- Editor: Ma S

References

- 1.Fabrizi F, Messa P, Martin P. Current status of renal transplantation from HCV-positive donors. Int J Artif Organs. 2009;32:251–261. doi: 10.1177/039139880903200502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finelli L, Miller JT, Tokars JI, Alter MJ, Arduino MJ. National surveillance of dialysis-associated diseases in the United States, 2002. Semin Dial. 2005;18:52–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2005.18108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okoh EJ, Bucci JR, Simon JF, Harrison SA. HCV in patients with end-stage renal disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2123–2134. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Domínguez-Gil B, Esforzado N, Andrés A, Campistol JM, Morales JM. Renal transplantation from donors with a positive serology for hepatitis C. Contrib Nephrol. 2012;176:117–129. doi: 10.1159/000332392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kilpatrick RD, McAllister CJ, Miller LG, Daar ES, Gjertson DW, Kopple JD, Greenland S. Hepatitis C virus and death risk in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1584–1593. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006070736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berenguer M. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C in hemodialysis patients. Hepatology. 2008;48:1690–1699. doi: 10.1002/hep.22545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kucirka LM, Singer AL, Ros RL, Montgomery RA, Dagher NN, Segev DL. Underutilization of hepatitis C-positive kidneys for hepatitis C-positive recipients. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:1238–1246. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott DR, Wong JK, Spicer TS, Dent H, Mensah FK, McDonald S, Levy MT. Adverse impact of hepatitis C virus infection on renal replacement therapy and renal transplant patients in Australia and New Zealand. Transplantation. 2010;90:1165–1171. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181f92548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fabrizi F, Takkouche B, Lunghi G, Dixit V, Messa P, Martin P. The impact of hepatitis C virus infection on survival in dialysis patients: meta-analysis of observational studies. J Viral Hepat. 2007;14:697–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of Hepatitis C in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2008;73(Suppl 109):S1–S99. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fabrizi F, Martin P, Dixit V, Bunnapradist S, Dulai G. Hepatitis C virus antibody status and survival after renal transplantation: meta-analysis of observational studies. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:1452–1461. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kucirka LM, Peters TG, Segev DL. Impact of donor hepatitis C virus infection status on death and need for liver transplant in hepatitis C virus-positive kidney transplant recipients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60:112–120. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pedroso S, Martins L, Fonseca I, Dias L, Henriques AC, Sarmento AM, Cabrita A. Impact of hepatitis C virus on renal transplantation: association with poor survival. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:1890–1894. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gheith OA, Saad MA, Hassan AA, A-Eldeeb S, Agroudy AE, Sheashaa H, Ghoneim MA. Hepatic dysfunction in kidney transplant recipients: prevalence and impact on graft and patient survival. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2007;11:309–315. doi: 10.1007/s10157-007-0490-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arango J, Arbelaez M, Henao J, Mejia G, Arroyave I, Carvajal J, Garcia A, Gutierrez J, Velásquez A, Garcia L, et al. Kidney graft survival in patients with hepatitis C: a single center experience. Clin Transplant. 2008;22:16–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2007.00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kliem V, Burg M, Haller H, Suwelack B, Abendroth D, Fritsche L, Fornara P, Pietruck F, Frei U, Donauer J, et al. Relationship of hepatitis B or C virus prevalences, risk factors, and outcomes in renal transplant recipients: analysis of German data. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:909–914. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meier-Kriesche HU, Ojo AO, Hanson JA, Kaplan B. Hepatitis C antibody status and outcomes in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2001;72:241–244. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200107270-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Batty DS, Swanson SJ, Kirk AD, Ko CW, Agodoa LY, Abbott KC. Hepatitis C virus seropositivity at the time of renal transplantation in the United States: associated factors and patient survival. Am J Transplant. 2001;1:179–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luan FL, Schaubel DE, Zhang H, Jia X, Pelletier SJ, Port FK, Magee JC, Sung RS. Impact of immunosuppressive regimen on survival of kidney transplant recipients with hepatitis C. Transplantation. 2008;85:1601–1606. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181722f3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu KQ, Lee SM, Hu SX, Xia VW, Hillebrand DJ, Kyulo NL. Clinical presentation of chronic hepatitis C in patients with end-stage renal disease and on hemodialysis versus those with normal renal function. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2010–2018. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.51938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sterling RK, Sanyal AJ, Luketic VA, Stravitz RT, King AL, Post AB, Mills AS, Contos MJ, Shiffman ML. Chronic hepatitis C infection in patients with end stage renal disease: characterization of liver histology and viral load in patients awaiting renal transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3576–3582. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luzar B, Ferlan-Marolt V, Brinovec V, Lesnicar G, Klopcic U, Poljak M. Does end-stage kidney failure influence hepatitis C progression in hemodialysis patients? Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:157–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maluf DG, Fisher RA, King AL, Gibney EM, Mas VR, Cotterell AH, Shiffman ML, Sterling RK, Behnke M, Posner MP. Hepatitis C virus infection and kidney transplantation: predictors of patient and graft survival. Transplantation. 2007;83:853–857. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000259725.96694.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sezer S, Ozdemir FN, Akcay A, Arat Z, Boyacioglu S, Haberal M. Renal transplantation offers a better survival in HCV-infected ESRD patients. Clin Transplant. 2004;18:619–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2004.00252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bloom RD, Sayer G, Fa K, Constantinescu S, Abt P, Reddy KR. Outcome of hepatitis C virus-infected kidney transplant candidates who remain on the waiting list. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:139–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Veroux M, Corona D, Veroux P. Kidney transplantation from donors with viral Heaptitis. In: Veroux M, Veroux P, editors. Kidney Transplantation: challenging the future. UAE: Bentham Publisher; 2012. pp. 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fabrizi F, Martin P, Dixit V, Bunnapradist S, Kanwal F, Dulai G. Post-transplant diabetes mellitus and HCV seropositive status after renal transplantation: meta-analysis of clinical studies. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:2433–2440. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ingsathit A, Kamanamool N, Thakkinstian A, Sumethkul V. Survival advantage of kidney transplantation over dialysis in patients with hepatitis C: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transplantation. 2013;95:943–948. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182848de2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gentil Govantes MA, Esforzado N, Cruzado JM, González-Roncero FM, Balaña M, Saval N, Morales JM. Harmful effects of viral replication in seropositive hepatitis C virus renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2012;94:1131–1137. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31826fc98f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Einollahi B, Hajarizadeh B, Bakhtiari S, Lesanpezeshki M, Khatami MR, Nourbala MH, Pourfarziani V, Alavian SM. Pretransplant hepatitis C virus infection and its effect on the post-transplant course of living renal allograft recipients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:836–840. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2003.03063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aroldi A, Lampertico P, Montagnino G, Passerini P, Villa M, Campise MR, Lunghi G, Tarantino A, Cesana BM, Messa P, et al. Natural history of hepatitis B and C in renal allograft recipients. Transplantation. 2005;79:1132–1136. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000161250.83392.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rostami Z, Nourbala MH, Alavian SM, Bieraghdar F, Jahani Y, Einollahi B. The impact of Hepatitis C virus infection on kidney transplantation outcomes: A systematic review of 18 observational studies: The impact of HCV on renal transplantation. Hepat Mon. 2011;11:247–254. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pereira BJ, Wright TL, Schmid CH, Bryan CF, Cheung RC, Cooper ES, Hsu H, Heyn-Lamb R, Light JA, Norman DJ. Screening and confirmatory testing of cadaver organ donors for hepatitis C virus infection: a U.S. National Collaborative Study. Kidney Int. 1994;46:886–892. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Botero RC. Should patients with chronic hepatitis C infection be transplanted? Transplant Proc. 2004;36:1449–1454. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Avery R, Preiksaitis J, Green M. Use of anti-HCV-positive donor organs. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Veroux P, Veroux M, Puliatti C, Cappello D, Macarone M, Gagliano M, Fiamingo P, Di Mare M, Spataro M, Ginevra N. Kidney transplantation from hepatitis C virus-positive donors into hepatitis C virus-positive recipients: a safe way to expand the donor pool? Transplant Proc. 2005;37:2571–2573. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.06.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mandal AK, Kraus ES, Samaniego M, Rai R, Humphreys SL, Ratner LE, Maley WR, Burdick JF. Shorter waiting times for hepatitis C virus seropositive recipients of cadaveric renal allografts from hepatitis C virus seropositive donors. Clin Transplant. 2000;14:391–396. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.2000.14040602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morales JM, Aguado JM. Hepatitis C and renal transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2012;17:609–615. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e32835a2bac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woodside KJ, Ishihara K, Theisen JE, Early MG, Covert LG, Hunter GC, Gugliuzza KK, Daller JA. Use of kidneys from hepatitis C seropositive donors shortens waitlist time but does not alter one-yr outcome. Clin Transplant. 2003;17:433–437. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.2003.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Veroux P, Veroux M, Sparacino V, Giuffrida G, Puliatti C, Macarone M, Fiamingo P, Cappello D, Gagliano M, Spataro M, et al. Kidney transplantation from donors with viral B and C hepatitis. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:996–998. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pereira BJ, Wright TL, Schmid CH, Levey AS. A controlled study of hepatitis C transmission by organ transplantation. The New England Organ Bank Hepatitis C Study Group. Lancet. 1995;345:484–487. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90583-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bouthot BA, Murthy BV, Schmid CH, Levey AS, Pereira BJ. Long-term follow-up of hepatitis C virus infection among organ transplant recipients: implications for policies on organ procurement. Transplantation. 1997;63:849–853. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199703270-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morales JM, Campistol JM, Domínguez-Gil B, Andrés A, Esforzado N, Oppenheimer F, Castellano G, Fuertes A, Bruguera M, Praga M. Long-term experience with kidney transplantation from hepatitis C-positive donors into hepatitis C-positive recipients. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:2453–2462. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abbott KC, Bucci JR, Matsumoto CS, Swanson SJ, Agodoa LY, Holtzmuller KC, Cruess DF, Peters TG. Hepatitis C and renal transplantation in the era of modern immunosuppression. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:2908–2918. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000090743.43034.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abbott KC, Lentine KL, Bucci JR, Agodoa LY, Peters TG, Schnitzler MA. The impact of transplantation with deceased donor hepatitis c-positive kidneys on survival in wait-listed long-term dialysis patients. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:2032–2037. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-6143.2004.00606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chan TM, Wu PC, Lok AS, Lai CL, Cheng IK. Clinicopathological features of hepatitis C virus antibody negative fatal chronic hepatitis C after renal transplantation. Nephron. 1995;71:213–217. doi: 10.1159/000188715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ridruejo E, Díaz C, Michel MD, Soler Pujol G, Martínez A, Marciano S, Mandó OG, Vilches A. Short and long term outcome of kidney transplanted patients with chronic viral hepatitis B and C. Ann Hepatol. 2010;9:271–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morales JM, Marcén R, Andres A, Domínguez-Gil B, Campistol JM, Gallego R, Gutierrez A, Gentil MA, Oppenheimer F, Samaniego ML, et al. Renal transplantation in patients with hepatitis C virus antibody. A long national experience. NDT Plus. 2010;3:ii41–ii46. doi: 10.1093/ndtplus/sfq070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh N, Neidlinger N, Djamali A, Leverson G, Voss B, Sollinger HW, Pirsch JD. The impact of hepatitis C virus donor and recipient status on long-term kidney transplant outcomes: University of Wisconsin experience. Clin Transplant. 2012;26:684–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2011.01583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morales JM, Campistol JM, Castellano G, Andres A, Colina F, Fuertes A, Ercilla G, Bruguera M, Andreu J, Carretero P. Transplantation of kidneys from donors with hepatitis C antibody into recipients with pre-transplantation anti-HCV. Kidney Int. 1995;47:236–240. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Natov SN, Lau JY, Ruthazer R, Schmid CH, Levey AS, Pereira BJ. Hepatitis C virus genotype does not affect patient survival among renal transplant candidates. The New England Organ Bank Hepatitis C Study Group. Kidney Int. 1999;56:700–706. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mathurin P, Moussalli J, Cadranel JF, Thibault V, Charlotte F, Dumouchel P, Cazier A, Huraux JM, Devergie B, Vidaud M, et al. Slow progression rate of fibrosis in hepatitis C virus patients with persistently normal alanine transaminase activity. Hepatology. 1998;27:868–872. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim SM, Kim HW, Lee EK, Park SK, Han DJ, Kim SB. Usefulness of liver biopsy in anti-hepatitis C virus antibody-positive and hepatitis C virus RNA-negative kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2013;96:85–90. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318294cad1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paramesh AS, Davis JY, Mallikarjun C, Zhang R, Cannon R, Shores N, Killackey MT, McGee J, Saggi BH, Slakey DP, et al. Kidney transplantation alone in ESRD patients with hepatitis C cirrhosis. Transplantation. 2012;94:250–254. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318255f890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aljumah AA, Saeed MA, Al Flaiw AI, Al Traif IH, Al Alwan AM, Al Qurashi SH, Al Ghamdi GA, Al Hejaili FF, Al Balwi MA, Al Sayyari AA. Efficacy and safety of treatment of hepatitis C virus infection in renal transplant recipients. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:55–63. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zylberberg H, Nalpas B, Carnot F, Skhiri H, Fontaine H, Legendre C, Kreis H, Bréchot C, Pol S. Severe evolution of chronic hepatitis C in renal transplantation: a case control study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:129–133. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alric L, Kamar N, Bonnet D, Danjoux M, Abravanel F, Lauwers-Cances V, Rostaing L. Comparison of liver stiffness, fibrotest and liver biopsy for assessment of liver fibrosis in kidney-transplant patients with chronic viral hepatitis. Transpl Int. 2009;22:568–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2009.00834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kamar N, Rostaing L, Selves J, Sandres-Saune K, Alric L, Durand D, Izopet J. Natural history of hepatitis C virus-related liver fibrosis after renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:1704–1712. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.de Oliveira Uehara SN, Emori CT, da Silva Fucuta Pereira P, Perez RM, Pestana JO, Lanzoni VP, e Silva IS, Silva AE, Ferraz ML. Histological evolution of hepatitis C virus infection after renal transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2012;26:842–848. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2012.01635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roth D, Gaynor JJ, Reddy KR, Ciancio G, Sageshima J, Kupin W, Guerra G, Chen L, Burke GW. Effect of kidney transplantation on outcomes among patients with hepatitis C. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:1152–1160. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010060668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wéclawiack H, Kamar N, Mehrenberger M, Guilbeau-Frugier C, Modesto A, Izopet J, Ribes D, Sallusto F, Rostaing L. Alpha-interferon therapy for chronic hepatitis C may induce acute allograft rejection in kidney transplant patients with failed allografts. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:1043–1047. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roth D, Bloom R. Selection and management of hepatitis C virus-infected patients for the kidney transplant waiting list. Contrib Nephrol. 2012;176:66–76. doi: 10.1159/000333774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Magnone M, Holley JL, Shapiro R, Scantlebury V, McCauley J, Jordan M, Vivas C, Starzl T, Johnson JP. Interferon-alpha-induced acute renal allograft rejection. Transplantation. 1995;59:1068–1070. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199504150-00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ozgür O, Boyacioğlu S, Telatar H, Haberal M. Recombinant alpha-interferon in renal allograft recipients with chronic hepatitis C. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1995;10:2104–2106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rostaing L, Modesto A, Baron E, Cisterne JM, Chabannier MH, Durand D. Acute renal failure in kidney transplant patients treated with interferon alpha 2b for chronic hepatitis C. Nephron. 1996;74:512–516. doi: 10.1159/000189444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Morales JM, Bloom R, Roth D. Kidney transplantation in the patient with hepatitis C virus infection. Contrib Nephrol. 2012;176:77–86. doi: 10.1159/000332385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bruchfeld A, Lindahl K, Ståhle L, Söderberg M, Schvarcz R. Interferon and ribavirin treatment in patients with hepatitis C-associated renal disease and renal insufficiency. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:1573–1580. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Russo MW, Goldsweig CD, Jacobson IM, Brown RS. Interferon monotherapy for dialysis patients with chronic hepatitis C: an analysis of the literature on efficacy and safety. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1610–1615. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gupta SK, Glue P, Jacobs S, Belle D, Affrime M. Single-dose pharmacokinetics and tolerability of pegylated interferon-alpha2b in young and elderly healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;56:131–134. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01836.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Werner T, Aqel B, Balan V, Byrne T, Carey E, Douglas D, Heilman RL, Rakela J, Mekeel K, Reddy K, et al. Treatment of hepatitis C in renal transplantation candidates: a single-center experience. Transplantation. 2010;90:407–411. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181e72837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rendina M, Schena A, Castellaneta NM, Losito F, Amoruso AC, Stallone G, Schena FP, Di Leo A, Francavilla A. The treatment of chronic hepatitis C with peginterferon alfa-2a (40 kDa) plus ribavirin in haemodialysed patients awaiting renal transplant. J Hepatol. 2007;46:768–774. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Terrault NA, Adey DB. The kidney transplant recipient with hepatitis C infection: pre- and posttransplantation treatment. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:563–575. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02930806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rostaing L, Weclawiak H, Izopet J, Kamar N. Treatment of hepatitis C virus infection after kidney transplantation. Contrib Nephrol. 2012;176:87–96. doi: 10.1159/000333775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Perico N, Cattaneo D, Bikbov B, Remuzzi G. Hepatitis C infection and chronic renal diseases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:207–220. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03710708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shu KH, Lan JL, Wu MJ, Cheng CH, Chen CH, Lee WC, Chang HR, Lian JD. Ultralow-dose alpha-interferon plus ribavirin for the treatment of active hepatitis C in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2004;77:1894–1896. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000131151.07818.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tang S, Cheng IK, Leung VK, Kuok UI, Tang AW, Wing Ho Y, Neng Lai K, Mao Chan T. Successful treatment of hepatitis C after kidney transplantation with combined interferon alpha-2b and ribavirin. J Hepatol. 2003;39:875–878. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Poynard T, Yuen MF, Ratziu V, Lai CL. Viral hepatitis C. Lancet. 2003;362:2095–2100. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)15109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sansonno D, Gesualdo L, Manno C, Schena FP, Dammacco F. Hepatitis C virus-related proteins in kidney tissue from hepatitis C virus-infected patients with cryoglobulinemic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. Hepatology. 1997;25:1237–1244. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Barsoum RS. Hepatitis C virus: from entry to renal injury--facts and potentials. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:1840–1848. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sarafidis PA, Ruilope LM. Insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, and renal injury: mechanisms and implications. Am J Nephrol. 2006;26:232–244. doi: 10.1159/000093632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Monti G, Galli M, Invernizzi F, Pioltelli P, Saccardo F, Monteverde A, Pietrogrande M, Renoldi P, Bombardieri S, Bordin G. Cryoglobulinaemias: a multi-centre study of the early clinical and laboratory manifestations of primary and secondary disease. GISC. Italian Group for the Study of Cryoglobulinaemias. QJM. 1995;88:115–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Meyers CM, Seeff LB, Stehman-Breen CO, Hoofnagle JH. Hepatitis C and renal disease: an update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42:631–657. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00828-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dalrymple LS, Koepsell T, Sampson J, Louie T, Dominitz JA, Young B, Kestenbaum B. Hepatitis C virus infection and the prevalence of renal insufficiency. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:715–721. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00470107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fabrizi F, Bromberg J, Elli A, Dixit V, Martin P. Review article: hepatitis C virus and calcineurin inhibition after renal transplantation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:657–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fagiuoli S, Bruni F, Bravi M, Candusso M, Gaffuri G, Colledan M, Torre G. Cyclosporin in steroid-resistant autoimmune hepatitis and HCV-related liver diseases. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39 Suppl 3:S379–S385. doi: 10.1016/S1590-8658(07)60018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rostaing L, Izopet J, Sandres K, Cisterne JM, Puel J, Durand D. Changes in hepatitis C virus RNA viremia concentrations in long-term renal transplant patients after introduction of mycophenolate mofetil. Transplantation. 2000;69:991–994. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200003150-00055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]