Abstract

Gastrointestinal lymphoma is the most common type of extranodal lymphoma, and most commonly affects the stomach. Marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma are the most common histologic types of gastric lymphoma. Despite its increasing incidence, diagnosis of gastric lymphoma is difficult at an earlier stage due to its nonspecific symptoms and endoscopic findings, and, thus, a high index of suspicion, and multiple, deep, repeated biopsies at abnormally and normally appearing sites in the stomach are needed. In addition, testing for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection and endoscopic ultrasonography to determine the depth of tumor invasion and involvement of regional lymph nodes is essential for predicting response to H. pylori eradication and for assessment of disease progression. In addition, H. pylori infection and MALT lymphoma development are associated, and complete regression of low-grade MALT lymphomas after H. pylori eradication has been demonstrated. Radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy can be used in cases that show poor response to H. pylori eradication, negativity for H. pylori infection, or high-grade lymphoma.

Keywords: Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue, Lymphoma, Helicobacter pylori, Eradication, Remission

Core tip: The incidence of gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma is increasing; however, early diagnosis is still difficult. Early detection and accurate stage workup is essential for treatment of MALT lymphoma. If gastric lymphoma is verified, testing for Helicobacter pylori infection, bone marrow biopsy, chest radiographs, endoscopic ultrasonography, and computed tomography scans should be performed for staging. We reviewed the most recent literature and provide a comprehensive summary of the diagnosis, treatment according to each stage, and follow-up on this topic.

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, one of the most common chronic infections, has a worldwide distribution. Infection rates differ by country; however, more than half of the world’s population is infected. In addition, H. pylori infection is the primary pathologic cause of development of low-grade, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma of the stomach. International guidelines strongly recommend bacterial eradication in all gastric MALT lymphoma patients[1-4]. In fact, during the early stages low-grade MALT lymphoma can be cured by H. pylori eradication in 60%-80% of cases[5-7].

Primary gastrointestinal lymphoma accounts for 30%-40% of all extranodal lymphomas. In addition, the incidence of primary gastric lymphoma has increased in recent decades[8], however, it is still a rare disease. Its lack of specific symptoms and various or nonspecific endoscopic findings make early detection and diagnosis difficult. Therefore, sufficient experience and endoscopic skill are needed in order to determine an accurate pathologic diagnosis and macroscopic lesion range. Here, we provide a review of the characteristics, diagnosis and treatment of primary gastric MALT lymphoma.

PATHOLOGIC CHARACTERISTICS OF GASTRIC MALT LYMPHOMA

Based on histologic characteristics, primary gastric lymphomas are classified as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the MALT type (MALT lymphoma), follicular lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, plasmacytoma, Burkitt’s lymphoma, and T-cell lymphoma. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and MALT lymphoma account for approximately 60% and 40% of all gastric lymphomas, respectively[9]. MALT lymphoma is defined as a diffuse proliferation of centrocyte-like cells with lymphoepithelial lesions[10], whereas diffuse large B-cell lymphomas are divided into two entities according to the presence or absence of areas of MALT lymphoma[11].

H. pylori infection plays an important role in development of almost all MALT lymphomas. Gastric tissue normally does not contain MALT, but may acquire it in response to chronic H. pylori infection[12]. Chronic inflammation causes proliferation of T-cells and B-cells due to antigen presentation. Malignant transformation occurs in a small percentage of B-cells and results in lymphoma, and the malignant process appears to be driven to a large degree by chronic H. pylori infection, because H. pylori eradication causes lymphoma regression in most cases[5]. However, four main chromosomal translocations, that is t (11; 18) (q21; q21), t (14; 18) (q32; q21), t (1; 14) (p22; q32), and t (3; 14) (p14.1; q32), reduce the response to H. pylori eradication[13,14] and are found in 30% of cases. The most common translocation type is t (11; 18) (q21; q21). This type is more common in cases involving the lung or stomach, and is significantly associated with infections by CagA-positive strains[14].

DIAGNOSIS OF GASTRIC MALT LYMPHOMA

Median age at diagnosis is approximately 60 years and no gender predominance is shown. The most common presenting symptoms of MALT lymphoma are nonspecific dyspepsia and epigastric pain, whereas constitutional B symptoms and gastric bleeding are rare[15]. Other less common symptoms include nausea, vomiting, anorexia, weight loss, and early satiety[16]. Because these symptoms are nonspecific and are observed in other gastrointestinal diseases, final diagnosis is made by endoscopic biopsy.

Endoscopic evaluation

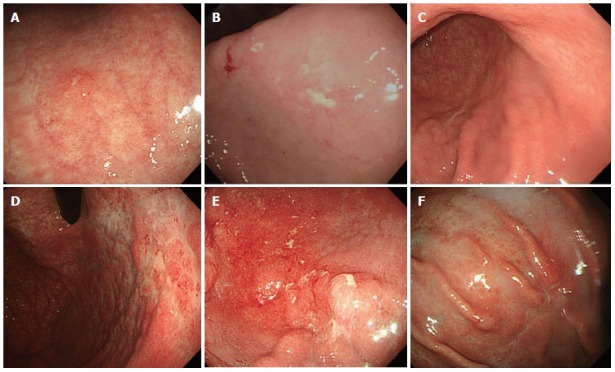

Gastric MALT lymphomas are evaluated by esophagogastroduodenoscopy. The most common sites of involvement in the stomach are the pyloric antrum, corpus, and cardia; however, due to the possibility of multifocal involvement, biopsies should be taken from all abnormal and random sites, including the stomach, gastroesophageal junction, and duodenum[17,18]. Endoscopic appearances of MALT lymphoma varies, including erythema, erosions, and ulcers (Figure 1). Diffuse superficial infiltration is common, whereas masses are more common in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma[19]. Unlike benign ulcers and early gastric cancer, the erosions and ulcers of MALT lymphoma have an irregular or geographic appearance and multifocal characteristics. They may also exhibit irregular mucosal nodularities or only color changes. Thus, if lymphoma is doubted, biopsy is needed. Because some lymphomas infiltrate the submucosal layer without mucosal layer involvement, biopsies should be sufficiently deep and large enough for histopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis. Evaluations of H. pylori infection should include histology, rapid urease testing, urea breath testing, monoclonal stool antigen testing, or serologic studies.

Figure 1.

Variable endoscopic findings of gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. A: Single erosive type; B: Ulcerative type; C: Atrophic type; D: Cobblestone-mucosa type; E: Nodular type; F: IIc-like type.

Pathologic evaluation

Histologic diagnosis of primary gastric lymphoma is somewhat difficult because the endoscopic findings of lymphomas are indistinguishable from those of benign gastritis, and because they can involve the submucosal layer without mucosal involvement[20,21]. A correct histologic diagnosis after first endoscopy is made in 75% of low-grade and 79% of high-grade cases[19]; thus, suspicion is most important during endoscopic examinations, and multiple biopsies, including normal mucosa, are needed due to the possibility of multifocal lesions or combined cases of low and high-grade lymphoma.

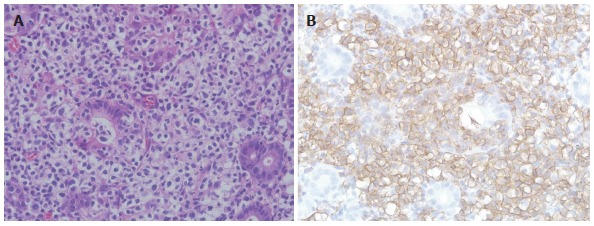

The histologic characteristics of the low-grade MALT lymphoma are: centrocyte-like cell proliferation; plasma cell infiltration; and lymphoepithelial lesions defined as the unequivocal invasion and partial destruction of gastric glands or crypts. The key histologic feature of low-grade MALT lymphoma is the presence of a lymphoepithelial lesion[22,23] (Figure 2). However, lymphoepithelial lesions can sometimes be seen in the context of florid chronic gastritis, and can be present in other sites of both native and acquired MALT[24]. The tumor cells of low-grade MALT lymphoma are usually small- to medium-sized lymphocytes with moderately abundant cytoplasm and irregularly shaped nuclei resembling those of follicular center cells (centrocytes) and have been designated centrocyte-like (CCL) cells[23]. There is a continuous spectrum of lesions during the transition from H. pylori-associated gastritis to low-grade MALT lymphoma. The histologic scoring system of the Wotherspoon criteria is widely used in diagnosis of MALT lymphoma[5] and immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangement analyses by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are also used[25]. Southern blot or PCR for immunoglobulin heavy chain rearrangement can assist in revealing monoclonality and in prediction of later lymphoma development; however the presence of monoclonality alone does not allow for a diagnosis of lymphoma. Accordingly, molecular tests should always be considered in the context of histologic findings[26-31].

Figure 2.

Histopathological and immunohistochemical features of gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. A: Histopathological finding. Gastric MALT lymphoma shows many lymphoepithelial lesions formed by the invasion of glands by centrocyte-like cells [hematoxylin and eosin (HE) stain, × 400]; B: Immunohistochemical finding. Centrocyte-like cells show strong positive signals for CD20 (× 400).

CCL cells of gastric MALT lymphoma and marginal zone B cells in spleen, Peyer’s patches and lymph nodes have almost the same immunophenotype. Both types of cells are positive for surface immunoglobulins and pan-B antigens (CD19, CD20, and CD79a) and lack CD5, CD10, CD23, and cyclin D1 expression[24,32].

Other evaluations

If gastric MALT lymphoma is verified, other examinations, such as endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), bone marrow biopsy, standard posteroanterior and lateral chest radiographs, upper airway examination, and CT scans of chest, abdomen and pelvis, should be performed for staging. Of these, EUS is recognized as valuable for diagnosis and treatment of gastric MALT lymphoma. The EUS findings of MALT lymphoma are superficially spreading, diffusely infiltrating, mass forming, and mixed types. Superficially spreading and diffusely infiltrative types are unique forms of low-grade MALT lymphoma[33]. In addition, EUS-guided biopsies are helpful for histologic evaluations when endoscopic biopsies are insufficient[34,35] and for supplementation of false negative endoscopic biopsies[36,37]. EUS can determine depth of infiltration and detect the presence of enlarged perigastric lymph nodes[38-42]. In one study, EUS produced a correct diagnosis of lymphoma with a sensitivity of 89%, specificity of 97%, and diagnostic accuracy of 95% and evaluation of lymphoma depth invasion with a sensitivity of 44%, specificity of 100%, and diagnostic accuracy of 77%[43,44]. In addition, EUS can be used for assessment of complete regression of MALT lymphoma after eradication of H. pylori. However, in this context, the effectiveness of EUS is controversial when verification of the presence or absence of a lesion is difficult due to atrophic changes caused by MALT lymphoma after H. pylori eradication[40]. Computed tomography is helpful for evaluation of lymph nodes on both sides of the diaphragm, but shows low sensitivity for detection of perigastric lymph node invasion[45]. Due to low fluorodeoxyglucose uptake, small lesion sizes, and slow progression, PET is not usually helpful[46-48].

TREATMENT OF GASTRIC MALT LYMPHOMA

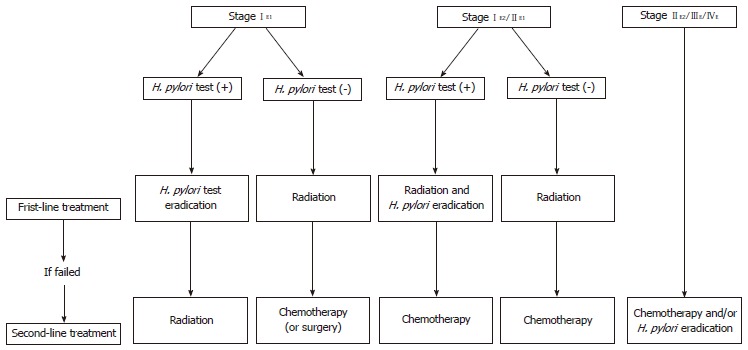

Low-grade MALT lymphoma (stage IE1 by Musshoff’s modification of the Ann Arbor classification[49,50], that is, infiltration limited to mucosa and submucosa) can show complete regression after H. pylori eradication, and thus, surgery and chemotherapy options are held in abeyance until the effects of H. pylori eradication are known (Figure 3)[42,51]. Therefore, accurate diagnosis and staging are essential before initiation of treatment (Table 1). Most low-grade MALT lymphomas are limited to the mucosal or submucosal layers, and response to H. pylori eradication is decreased in cases of deeper involvement. Accordingly, evaluations of gastric wall involvement by EUS are important[42,52,53]. In general, MALT lymphoma shows slow progression and its prognosis is good when the disease is localized, before the terminal stage[54]. However, rate of progression to high-grade lymphoma accelerates with time; thus, early diagnosis and treatment is important.

Figure 3.

Ann Arbor staging system modified by Musshoff and suggested therapeutic algorithm for gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. H.pylori: Helicobacter pylori.

Table 1.

Staging systems of gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma

| Lugano staging system for gastrointestinal lymphoma | TNM staging system modified for gastric lymphoma | Ann Arbor staging system modified by Musshoff | Tumor involvement |

| I = Confined to GI tract (single primary or multiple, noncontiguous) | T1 N0 M0 | IE1 | Mucosa, submucosa |

| T2 N0 M0 | IE2 | Muscularis propria Serosa | |

| T3 N0 M0 | |||

| II = Extending into abdomen | |||

| II1 = Local nodal involvement | T1-3 N1 M0 | IIE1 | Perigastric lymph nodes |

| II2 = Distant nodal involvement | T1-3 N2 M0 | IIE2 | More distant regional lymph nodes |

| IIE = Penetration of serosa to involve adjacent organs or tissues | T4 N0 M0 | IE | Invasion of adjacent structures |

| IV = Disseminated extra-nodal involvement or concomitant supradiaphragmatic nodal involvement | T1-4 N3 M0 | IIIE | Lymph nodes on both sides of the diaphragm |

| T1-4 N0-3 M1 | IVE | Distant metastases (e.g., bone marrow or additional extranodal sites) | |

GI: Gastrointestinal; TNM: Tumor node metastasis.

H. pylori eradication

Numerous studies have confirmed that gastric MALT lymphoma can show complete regression according to endoscopic, histologic, and molecular criteria after H. pylori eradication[52,55-58]; since the first such report was issued[5], other studies evaluating the effectiveness of H. pylori eradication in stage IE1 have reported complete remission rates of 60%-92%[5-7,59-64]. In general, patients who are positive for H. pylori are administered triple or quadruple H. pylori therapy for 1-2 wk[52,59,60], and then retested 4-8 wk later. If this first-line therapy fails, bismuth-based quadruple therapy (excluding antibiotics previously taken) is recommended[1,2,65]. Reported prevalence rates of H. pylori negativity in gastric MALT lymphoma range from 0% to 38%[66,67]. However, several factors should be kept in mind, such as after H. pylori eradication, recovery after H. pylori infection, non-H. pylori infection such as Helicobacter heilmannii or Helicobacter felis, or autoimmune effects can cause false negative results for H. pylori in early gastric MALT lymphoma. Thus, overlapping tests for H. pylori infection and detailed history taking are needed. Although five patients showing negative test results for H. pylori who were cured after H. pylori eradication have been reported[68-70], it is controversial. Successfully treated cases after radiotherapy only have been reported[71], however further studies are needed.

Treatment of high-grade MALT lymphoma

Changes to high-grade MALT lymphoma result in proliferation regardless of H. pylori antigen, and correlation between increase of stage or histologic grade and decrease of H. pylori infection rates has been reported[11]. More than 80% of patients with stage IIE disease (lymphoma additionally infiltrating lymph nodes on the same side of the diaphragm) were reported to be cured after total gastrectomy[72]; however, this technique has a marked effect on quality of life[73]. On the other hand, involved field radiotherapy at 30-40 Gy delivered in four weeks to the stomach and perigastric nodes was found to result in a complete remission rate of 90%-100% and a 5-year disease-free survival rate of approximately 80%[74-76]. Radiotherapy is preferred in patients with advanced disease negative for H. pylori and in those with persistent disease after H. pylori eradication[77]. Other treatments include chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or combined chemoimmunotherapy. Immunotherapy with rituximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody directed against B-cell-specific antigen CD20, was first demonstrated in patients with follicular lymphomas[78]. In addition, the therapeutic use of this antibody has been extended over recent years to other types of non-Hodgkin lymphomas, and it has shown good results as a single agent[78-80] or in combination with chemotherapy[81-84]. Rituximab is also effective in gastric MALT lymphoma resistant or refractory to antibiotics and negative for H. pylori infection[85,86]. If high-grade MALT lymphoma is positive for H. pylori infection, H. pylori eradication treatment should be administered because the presence of H. pylori could aid recurrence, although the usefulness of eradication in such cases has been questioned.

Follow-up

Complete remission of low-grade MALT lymphoma after H. pylori eradication takes considerable time; thus, regular endoscopic follow-up is needed. Regression may be indicated by an area of whitish or discolored mucosa with a granular pattern[87,88]. Nevertheless, endoscopic findings can be nonspecific in recurrent cases; thus, endoscopic biopsies of normal and abnormal-looking gastric areas are needed. Median time to remission is 5 mo, and is usually achieved within 12 mo; however, in some cases, time to remission has been reported to be as long as 45 mo[55,61,77]. Endoscopic examination with biopsies, tests for H. pylori infection, and EUS are recommended every 3 mo until remission, and then every 6 mo or annually for two years; however, the length of follow-up needed has not been determined[57,89]. Histologic remission of MALT lymphoma does not mean cure due to the possibility of false-negative results and of the survival of some malignant cells. Unfortunately, there is no unequivocal indicator of cure. A PCR test was recently devised for detection of tumor clones, and 50% of patients in clinical remission were found to have tumor clones by PCR. Furthermore, a decrease in clone counts was observed during continued follow-up[90]. In another study, these remnant malignant clones detected by PCR had disappeared at 12 mo[91]. Accordingly, a positive PCR result after achievement of histologic remission does not predict for subsequent relapse; thus, a long follow-up period is needed[58].

Footnotes

P- Reviewers: Peter B, Sakata N S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: O’Neill M E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, Atherton J, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gensini GF, Gisbert JP, Graham DY, Rokkas T, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection--the Maastricht IV/ Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646–664. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chey WD, Wong BC. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1808–1825. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujioka T, Yoshiiwa A, Okimoto T, Kodama M, Murakami K. Guidelines for the management of Helicobacter pylori infection in Japan: current status and future prospects. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42 Suppl 17:3–6. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1938-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caselli M, Zullo A, Maconi G, Parente F, Alvisi V, Casetti T, Sorrentino D, Gasbarrini G. “Cervia II Working Group Report 2006”: guidelines on diagnosis and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in Italy. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:782–789. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wotherspoon AC, Doglioni C, Diss TC, Pan L, Moschini A, de Boni M, Isaacson PG. Regression of primary low-grade B-cell gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet. 1993;342:575–577. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91409-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen LT, Lin JT, Tai JJ, Chen GH, Yeh HZ, Yang SS, Wang HP, Kuo SH, Sheu BS, Jan CM, et al. Long-term results of anti-Helicobacter pylori therapy in early-stage gastric high-grade transformed MALT lymphoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1345–1353. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stathis A, Chini C, Bertoni F, Proserpio I, Capella C, Mazzucchelli L, Pedrinis E, Cavalli F, Pinotti G, Zucca E. Long-term outcome following Helicobacter pylori eradication in a retrospective study of 105 patients with localized gastric marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT type. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1086–1093. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakamura S, Matsumoto T, Iida M, Yao T, Tsuneyoshi M. Primary gastrointestinal lymphoma in Japan: a clinicopathologic analysis of 455 patients with special reference to its time trends. Cancer. 2003;97:2462–2473. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrucci PF, Zucca E. Primary gastric lymphoma pathogenesis and treatment: what has changed over the past 10 years? Br J Haematol. 2007;136:521–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isaacson P, Wright DH. Malignant lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. A distinctive type of B-cell lymphoma. Cancer. 1983;52:1410–1416. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19831015)52:8<1410::aid-cncr2820520813>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakamura S, Matsumoto T, Takeshita M, Kurahara K, Yao T, Tsuneyoshi M, Iida M, Fujishima M. A clinicopathologic study of primary small intestine lymphoma: prognostic significance of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue-derived lymphoma. Cancer. 2000;88:286–294. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000115)88:2<286::aid-cncr7>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagai S, Mimuro H, Yamada T, Baba Y, Moro K, Nochi T, Kiyono H, Suzuki T, Sasakawa C, Koyasu S. Role of Peyer’s patches in the induction of Helicobacter pylori-induced gastritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:8971–8976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609014104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu H, Ye H, Ruskone-Fourmestraux A, De Jong D, Pileri S, Thiede C, Lavergne A, Boot H, Caletti G, Wündisch T, et al. T(11; 18) is a marker for all stage gastric MALT lymphomas that will not respond to H. pylori eradication. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1286–1294. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ye H, Liu H, Attygalle A, Wotherspoon AC, Nicholson AG, Charlotte F, Leblond V, Speight P, Goodlad J, Lavergne-Slove A, et al. Variable frequencies of t(11; 18)(q21; q21) in MALT lymphomas of different sites: significant association with CagA strains of H pylori in gastric MALT lymphoma. Blood. 2003;102:1012–1018. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zucca E, Bertoni F, Roggero E, Cavalli F. The gastric marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT type. Blood. 2000;96:410–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koch P, del Valle F, Berdel WE, Willich NA, Reers B, Hiddemann W, Grothaus-Pinke B, Reinartz G, Brockmann J, Temmesfeld A, et al. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: I. Anatomic and histologic distribution, clinical features, and survival data of 371 patients registered in the German Multicenter Study GIT NHL 01/92. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3861–3873. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.18.3861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahl BS. Update: gastric MALT lymphoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2003;15:347–352. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200309000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wotherspoon AC, Doglioni C, Isaacson PG. Low-grade gastric B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT): a multifocal disease. Histopathology. 1992;20:29–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1992.tb00912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taal BG, Boot H, van Heerde P, de Jong D, Hart AA, Burgers JM. Primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the stomach: endoscopic pattern and prognosis in low versus high grade malignancy in relation to the MALT concept. Gut. 1996;39:556–561. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.4.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seifert E, Schulte F, Weismüller J, de Mas CR, Stolte M. Endoscopic and bioptic diagnosis of malignant non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the stomach. Endoscopy. 1993;25:497–501. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caletti G, Barbara L. Gastric lymphoma: difficult to diagnose, difficult to stage? Endoscopy. 1993;25:528–530. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Stein H, Banks PM, Chan JK, Cleary ML, Delsol G, De Wolf-Peeters C, Falini B, Gatter KC. A revised European-American classification of lymphoid neoplasms: a proposal from the International Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 1994;84:1361–1392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isaacson PG, Spencer J. Malignant lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Histopathology. 1987;11:445–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1987.tb02654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan JK. Gastrointestinal lymphomas: an overview with emphasis on new findings and diagnostic problems. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1996;13:260–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hummel M, Oeschger S, Barth TF, Loddenkemper C, Cogliatti SB, Marx A, Wacker HH, Feller AC, Bernd HW, Hansmann ML, et al. Wotherspoon criteria combined with B cell clonality analysis by advanced polymerase chain reaction technology discriminates covert gastric marginal zone lymphoma from chronic gastritis. Gut. 2006;55:782–787. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.080523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aiello A, Giardini R, Tondini C, Balzarotti M, Diss T, Peng H, Delia D, Pilotti S. PCR-based clonality analysis: a reliable method for the diagnosis and follow-up monitoring of conservatively treated gastric B-cell MALT lymphomas? Histopathology. 1999;34:326–330. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1999.00628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diss TC, Peng H, Wotherspoon AC, Isaacson PG, Pan L. Detection of monoclonality in low-grade B-cell lymphomas using the polymerase chain reaction is dependent on primer selection and lymphoma type. J Pathol. 1993;169:291–295. doi: 10.1002/path.1711690303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan LX, Diss TC, Peng HZ, Isaacson PG. Clonality analysis of defined B-cell populations in archival tissue sections using microdissection and the polymerase chain reaction. Histopathology. 1994;24:323–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1994.tb00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bertoni F, Cotter FE, Zucca E. Molecular genetics of extranodal marginal zone (MALT-type) B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 1999;35:57–68. doi: 10.3109/10428199909145705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Mascarel A, Dubus P, Belleannée G, Megraud F, Merlio JP. Low prevalence of monoclonal B cells in Helicobacter pylori gastritis patients with duodenal ulcer. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:784–790. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90446-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diss TC, Pan L. Polymerase chain reaction in the assessment of lymphomas. Cancer Surv. 1997;30:21–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pileri SA, Sabattini E. A rational approach to immunohistochemical analysis of malignant lymphomas on paraffin wax sections. J Clin Pathol. 1997;50:2–4. doi: 10.1136/jcp.50.1.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mehra M, Agarwal B. Endoscopic diagnosis and staging of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008;24:623–626. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32830bf80f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Toyoda H, Ono T, Kiyose M, Toyoda M, Yamaguchi M, Shiku H, Tonouchi H. Gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma with a focal high-grade component diagnosed by EUS and endoscopic mucosal resection for histologic evaluation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:752–755. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.105732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Queneau PE, Helg C, Brundler MA, Frossard JL, Spahr L, Girardet C, Armenian B, Hadengue A. Diagnosis of a gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma by endoscopic ultrasonography-guided biopsies in a patient with a parotid gland localization. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:493–496. doi: 10.1080/003655202317316150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fujishima H, Misawa T, Maruoka A, Chijiiwa Y, Sakai K, Nawata H. Staging and follow-up of primary gastric lymphoma by endoscopic ultrasonography. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:719–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lévy M, Hammel P, Lamarque D, Marty O, Chaumette MT, Haioun C, Blazquez M, Delchier JC. Endoscopic ultrasonography for the initial staging and follow-up in patients with low-grade gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue treated medically. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46:328–333. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(97)70120-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fischbach W, Goebeler-Kolve ME, Greiner A. Diagnostic accuracy of EUS in the local staging of primary gastric lymphoma: results of a prospective, multicenter study comparing EUS with histopathologic stage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:696–700. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.128915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caletti G, Zinzani PL, Fusaroli P, Buscarini E, Parente F, Federici T, Peyre S, De Angelis C, Bonanno G, Togliani T, et al. The importance of endoscopic ultrasonography in the management of low-grade gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1715–1722. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakamura S, Matsumoto T, Suekane H, Takeshita M, Hizawa K, Kawasaki M, Yao T, Tsuneyoshi M, Iida M, Fujishima M. Predictive value of endoscopic ultrasonography for regression of gastric low grade and high grade MALT lymphomas after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Gut. 2001;48:454–460. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.4.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pavlick AC, Gerdes H, Portlock CS. Endoscopic ultrasound in the evaluation of gastric small lymphocytic mucosa-associated lymphoid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1761–1766. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.5.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sackmann M, Morgner A, Rudolph B, Neubauer A, Thiede C, Schulz H, Kraemer W, Boersch G, Rohde P, Seifert E, et al. Regression of gastric MALT lymphoma after eradication of Helicobacter pylori is predicted by endosonographic staging. MALT Lymphoma Study Group. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1087–1090. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9322502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caletti G, Ferrari A, Brocchi E, Barbara L. Accuracy of endoscopic ultrasonography in the diagnosis and staging of gastric cancer and lymphoma. Surgery. 1993;113:14–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palazzo L, Roseau G, Ruskone-Fourmestraux A, Rougier P, Chaussade S, Rambaud JC, Couturier D, Paolaggi JA. Endoscopic ultrasonography in the local staging of primary gastric lymphoma. Endoscopy. 1993;25:502–508. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grau E, Gomez A, Cuñat A, Oltra C. Computed tomography in staging of primary gastric lymphoma. Lancet. 1996;347:1261. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90776-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elstrom R, Guan L, Baker G, Nakhoda K, Vergilio JA, Zhuang H, Pitsilos S, Bagg A, Downs L, Mehrotra A, et al. Utility of FDG-PET scanning in lymphoma by WHO classification. Blood. 2003;101:3875–3876. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, Gascoyne RD, Specht L, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, Fisher RI, Hagenbeek A, Zucca E, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:579–586. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alinari L, Castellucci P, Elstrom R, Ambrosini V, Stefoni V, Nanni C, Berkowitz A, Tani M, Farsad M, Franchi R, et al. 18F-FDG PET in mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:2096–2101. doi: 10.1080/10428190600733499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Musshoff K. [Clinical staging classification of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (author’s transl)] Strahlentherapie. 1977;153:218–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carbone PP, Kaplan HS, Musshoff K, Smithers DW, Tubiana M. Report of the Committee on Hodgkin’s Disease Staging Classification. Cancer Res. 1971;31:1860–1861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahmad A, Govil Y, Frank BB. Gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:975–986. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Neubauer A, Thiede C, Morgner A, Alpen B, Ritter M, Neubauer B, Wündisch T, Ehninger G, Stolte M, Bayerdörffer E. Cure of Helicobacter pylori infection and duration of remission of low-grade gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1350–1355. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.18.1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nobre-Leitão C, Lage P, Cravo M, Cabeçadas J, Chaves P, Alberto-Santos A, Correia J, Soares J, Costa-Mira F. Treatment of gastric MALT lymphoma by Helicobacter pylori eradication: a study controlled by endoscopic ultrasonography. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:732–736. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.215_a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Radaszkiewicz T, Dragosics B, Bauer P. Gastrointestinal malignant lymphomas of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue: factors relevant to prognosis. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1628–1638. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91723-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Steinbach G, Ford R, Glober G, Sample D, Hagemeister FB, Lynch PM, McLaughlin PW, Rodriguez MA, Romaguera JE, Sarris AH, et al. Antibiotic treatment of gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. An uncontrolled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:88–95. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-2-199907200-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Montalban C, Santon A, Boixeda D, Redondo C, Alvarez I, Calleja JL, de Argila CM, Bellas C. Treatment of low grade gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma in stage I with Helicobacter pylori eradication. Long-term results after sequential histologic and molecular follow-up. Haematologica. 2001;86:609–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fischbach W, Goebeler-Kolve ME, Dragosics B, Greiner A, Stolte M. Long term outcome of patients with gastric marginal zone B cell lymphoma of mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) following exclusive Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy: experience from a large prospective series. Gut. 2004;53:34–37. doi: 10.1136/gut.53.1.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bertoni F, Conconi A, Capella C, Motta T, Giardini R, Ponzoni M, Pedrinis E, Novero D, Rinaldi P, Cazzaniga G, et al. Molecular follow-up in gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas: early analysis of the LY03 cooperative trial. Blood. 2002;99:2541–2544. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.7.2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bayerdörffer E, Neubauer A, Rudolph B, Thiede C, Lehn N, Eidt S, Stolte M. Regression of primary gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type after cure of Helicobacter pylori infection. MALT Lymphoma Study Group. Lancet. 1995;345:1591–1594. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roggero E, Zucca E, Pinotti G, Pascarella A, Capella C, Savio A, Pedrinis E, Paterlini A, Venco A, Cavalli F. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection in primary low-grade gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:767–769. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-10-199505150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pinotti G, Zucca E, Roggero E, Pascarella A, Bertoni F, Savio A, Savio E, Capella C, Pedrinis E, Saletti P, et al. Clinical features, treatment and outcome in a series of 93 patients with low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 1997;26:527–537. doi: 10.3109/10428199709050889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wotherspoon AC. Gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue and Helicobacter pylori. Annu Rev Med. 1998;49:289–299. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Choi YJ, Lee DH, Kim JY, Kwon JE, Kim JY, Jo HJ, Shin CM, Kim HY, Park YS, Kim N, et al. Low Grade Gastric Mucosa-associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma: Clinicopathological Factors Associated with Helicobacter pylori Eradication and Tumor Regression. Clin Endosc. 2011;44:101–108. doi: 10.5946/ce.2011.44.2.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Montalban C, Norman F. Treatment of gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: Helicobacter pylori eradication and beyond. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2006;6:361–371. doi: 10.1586/14737140.6.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fock KM, Katelaris P, Sugano K, Ang TL, Hunt R, Talley NJ, Lam SK, Xiao SD, Tan HJ, Wu CY, et al. Second Asia-Pacific Consensus Guidelines for Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1587–1600. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nakamura S, Yao T, Aoyagi K, Iida M, Fujishima M, Tsuneyoshi M. Helicobacter pylori and primary gastric lymphoma. A histopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 237 patients. Cancer. 1997;79:3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Karat D, O’Hanlon DM, Hayes N, Scott D, Raimes SA, Griffin SM. Prospective study of Helicobacter pylori infection in primary gastric lymphoma. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1369–1370. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800821025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morgner A, Lehn N, Andersen LP, Thiede C, Bennedsen M, Trebesius K, Neubauer B, Neubauer A, Stolte M, Bayerdörffer E. Helicobacter heilmannii-associated primary gastric low-grade MALT lymphoma: complete remission after curing the infection. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:821–828. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen LT, Lin JT, Shyu RY, Jan CM, Chen CL, Chiang IP, Liu SM, Su IJ, Cheng AL. Prospective study of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in stage I(E) high-grade mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the stomach. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:4245–4251. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.22.4245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Raderer M, Streubel B, Wöhrer S, Häfner M, Chott A. Successful antibiotic treatment of Helicobacter pylori negative gastric mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas. Gut. 2006;55:616–618. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.083022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schechter NR, Portlock CS, Yahalom J. Treatment of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the stomach with radiation alone. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1916–1921. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.5.1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kuo SH, Chen LT, Wu MS, Lin CW, Yeh KH, Kuo KT, Yeh PY, Tzeng YS, Wang HP, Hsu PN, et al. Long-term follow-up of gastrectomized patients with mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: need for a revisit of surgical treatment. Ann Surg. 2008;247:265–269. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181582364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yoon SS, Coit DG, Portlock CS, Karpeh MS. The diminishing role of surgery in the treatment of gastric lymphoma. Ann Surg. 2004;240:28–37. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000129356.81281.0c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schechter NR, Yahalom J. Low-grade MALT lymphoma of the stomach: a review of treatment options. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;46:1093–1103. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00522-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tsang RW, Gospodarowicz MK, Pintilie M, Wells W, Hodgson DC, Sun A, Crump M, Patterson BJ. Localized mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma treated with radiation therapy has excellent clinical outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4157–4164. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yahalom J. MALT lymphomas: a radiation oncology viewpoint. Ann Hematol. 2001;80 Suppl 3:B100–B105. doi: 10.1007/pl00022769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Du MQ, Isaccson PG. Gastric MALT lymphoma: from aetiology to treatment. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:97–104. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00651-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McLaughlin P, Grillo-López AJ, Link BK, Levy R, Czuczman MS, Williams ME, Heyman MR, Bence-Bruckler I, White CA, Cabanillas F, et al. Rituximab chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy for relapsed indolent lymphoma: half of patients respond to a four-dose treatment program. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2825–2833. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.8.2825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Foran JM, Rohatiner AZ, Cunningham D, Popescu RA, Solal-Celigny P, Ghielmini M, Coiffier B, Johnson PW, Gisselbrecht C, Reyes F, et al. European phase II study of rituximab (chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) for patients with newly diagnosed mantle-cell lymphoma and previously treated mantle-cell lymphoma, immunocytoma, and small B-cell lymphocytic lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:317–324. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dimopoulos MA, Zervas C, Zomas A, Kiamouris C, Viniou NA, Grigoraki V, Karkantaris C, Mitsouli C, Gika D, Christakis J, et al. Treatment of Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia with rituximab. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2327–2333. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Coiffier B, Haioun C, Ketterer N, Engert A, Tilly H, Ma D, Johnson P, Lister A, Feuring-Buske M, Radford JA, et al. Rituximab (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) for the treatment of patients with relapsing or refractory aggressive lymphoma: a multicenter phase II study. Blood. 1998;92:1927–1932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Czuczman MS, Grillo-López AJ, White CA, Saleh M, Gordon L, LoBuglio AF, Jonas C, Klippenstein D, Dallaire B, Varns C. Treatment of patients with low-grade B-cell lymphoma with the combination of chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and CHOP chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:268–276. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.1.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vose JM, Link BK, Grossbard ML, Czuczman M, Grillo-Lopez A, Gilman P, Lowe A, Kunkel LA, Fisher RI. Phase II study of rituximab in combination with chop chemotherapy in patients with previously untreated, aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:389–397. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, Herbrecht R, Tilly H, Bouabdallah R, Morel P, Van Den Neste E, Salles G, Gaulard P, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:235–242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Conconi A, Martinelli G, Thiéblemont C, Ferreri AJ, Devizzi L, Peccatori F, Ponzoni M, Pedrinis E, Dell’Oro S, Pruneri G, et al. Clinical activity of rituximab in extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT type. Blood. 2003;102:2741–2745. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Martinelli G, Laszlo D, Ferreri AJ, Pruneri G, Ponzoni M, Conconi A, Crosta C, Pedrinis E, Bertoni F, Calabrese L, et al. Clinical activity of rituximab in gastric marginal zone non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma resistant to or not eligible for anti-Helicobacter pylori therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1979–1983. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Urakami Y, Sano T, Begum S, Endo H, Kawamata H, Oki Y. Endoscopic characteristics of low-grade gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:1113–1119. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ishihara R, Tatsuta M, Iishi H, Uedo N, Narahara H, Ishiguro S. Usefulness of endoscopic appearance for choosing a biopsy target site and determining complete remission of primary gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue after eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:772–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wündisch T, Thiede C, Morgner A, Dempfle A, Günther A, Liu H, Ye H, Du MQ, Kim TD, Bayerdörffer E, et al. Long-term follow-up of gastric MALT lymphoma after Helicobacter pylori eradication. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8018–8024. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.3903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Thiede C, Wündisch T, Neubauer B, Alpen B, Morgner A, Ritter M, Ehninger G, Stolte M, Bayerdörffer E, Neubauer A. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori and stability of remissions in low-grade gastric B-cell lymphomas of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue: results of an ongoing multicenter trial. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2000;156:125–133. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-57054-4_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Montalban C, Manzanal A, Boixeda D, Redondo C, Alvarez I, Calleja JL, Bellas C. Helicobacter pylori eradication for the treatment of low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma: follow-up together with sequential molecular studies. Ann Oncol. 1997;8 Suppl 2:37–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]